Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Analyzing Human Trafficking Networks Using Graph-Based Visualization and ARIMA Time Series Forecasting

1 College of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Hail, Hail, 81481, Saudi Arabia

2 Centre for Cybersecurity, School of Computer Science, UPES, Dehradun, 248007, India

* Corresponding Authors: Naif Alsharabi. Email: ; Akashdeep Bhardwaj. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 135-163. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.064019

Received 01 February 2025; Accepted 26 May 2025; Issue published 18 June 2025

Abstract

In a world driven by unwavering moral principles rooted in ethics, the widespread exploitation of human beings stands universally condemned as abhorrent and intolerable. Traditional methods employed to identify, prevent, and seek justice for human trafficking have demonstrated limited effectiveness, leaving us confronted with harrowing instances of innocent children robbed of their childhood, women enduring unspeakable humiliation and sexual exploitation, and men trapped in servitude by unscrupulous oppressors on foreign shores. This paper focuses on human trafficking and introduces intelligent technologies including graph database solutions for deciphering unstructured relationships and entity nodes, enabling the comprehensive visualization of datasets linked to the scourge of human trafficking. The authors propose an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) time series model, showcasing its remarkable accuracy in forecasting temporal trends within the dataset’s timeframe. The research analysis leverages a comprehensive human trafficking dataset from Kaggle, comprising 48,800 records encompassing 63 distinct attributes. The findings underscore the effectiveness of the proposed model, revealing a compelling correlation between the predictions generated by the model and the actual values embedded in the dataset.Keywords

Human trafficking is a pervasive global crime that flagrantly violates fundamental human rights, exploiting individuals through forced labor, sexual exploitation, and other forms of coercion. Despite international agreements and policies to combat trafficking, the crime remains concealed within complex networks, leaving victims vulnerable to extreme exploitation. Alarmingly, reports from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, 2022) [1] indicate a significant rise in trafficking cases, with minors increasingly identified as victims, particularly for sexual exploitation and forced labor. Women and girls are disproportionately affected, accounting for nearly 70% of all victims [2].

COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the crisis, amplified vulnerabilities and driving an increase in online exploitation. Social media platforms have become recruitment hubs for traffickers, who exploit victims through deceptive job offers, romantic manipulation, or coercion. Tactics such as ‘fishing’ posting fake job ads and ‘hunting’ actively pursuing victims online highlight the insidious role of technology in modern trafficking networks. According to INTERPOL (2021) [3], over 286 traffickers were apprehended in a single global operation, underscoring the scale of this criminal enterprise. Concurrently, technology provides opportunities for detection, investigation, and prevention.

The characteristics of victims varied considerably depending on the type of exploitation they suffered. Human trafficking represents a worldwide criminal atrocity that flagrantly violates fundamental human rights, and it is dealt with through international agreements and treaties with the primary objectives of prevention, eradication, and the imposition of sanctions against its perpetrators. This activity encompasses a range of actions, including employing force, coercion, or other manipulative tactics during the recruitment, transportation, relocation, sheltering, or reception of individuals. The primary purpose is exploitation, which includes human trafficking, exploitation of workers, forced pleading, forced crime, organ extraction, and other types of exploitation. A person does not need to have crossed an international boundary for trafficking to occur; it can and does occur within national borders (Peril of Africa, 2021) [4]. Males continue to make up the bulk of individuals charged with and convicted of human trafficking globally, accounting for 64 and 62 percent of all cases, as per Statista Research Department (Statista Research Department, 2021) [5]. The internet plays a pivotal role in this sinister paradigm, enabling traffickers to live-stream the exploitation of their victims, thereby facilitating the simultaneous exploitation of a single victim by numerous customers worldwide (UNODC, Human Trafficking, 2019) [6].

Human trafficking occurs daily worldwide, including in all 50 states of the USA (Statista Research Department, 2021) [7]. It affects humans of all ages, ethnicities, and socioeconomic levels. While it is a widespread issue, it is not always obvious. Many people spend their whole lives without recognizing any indication of the crime due to its concealment.

Human trafficking is one of the most heinous crimes in the contemporary world. It is most likely occurring in communities, but identifying it requires courage and perseverance. Recognizing what human trafficking is and how it affects victims and perpetrators may help people keep safe while empowering you to assist others.

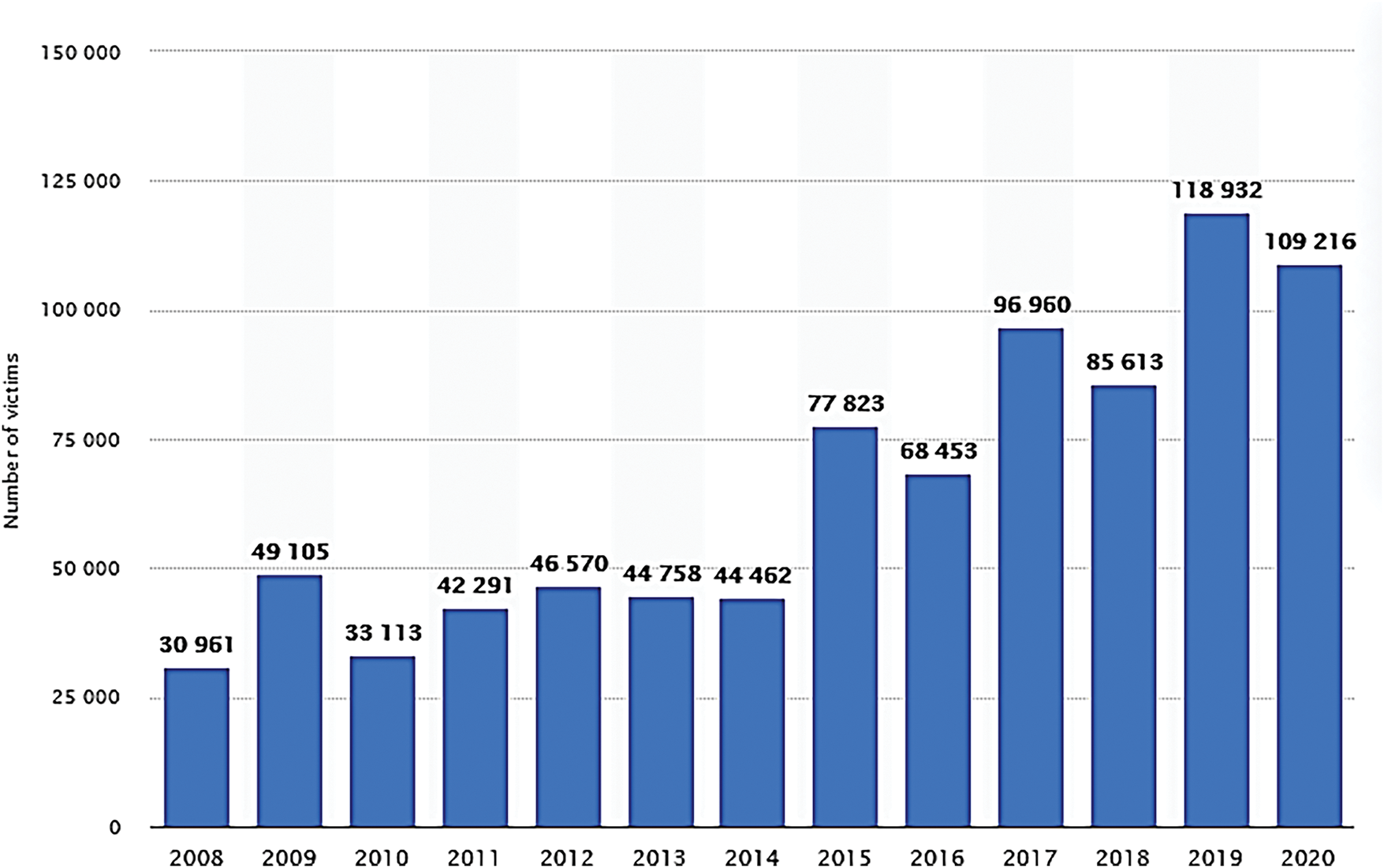

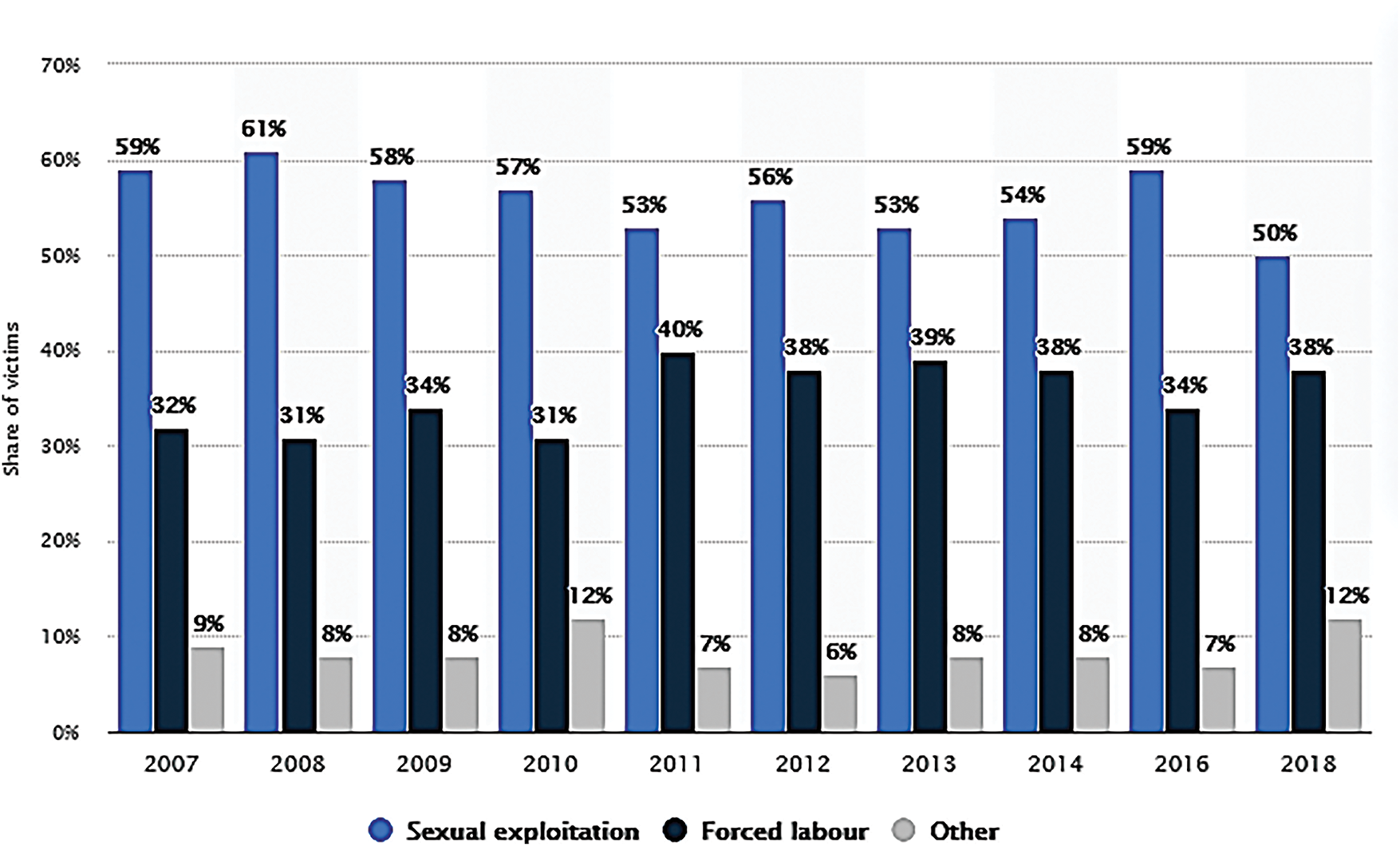

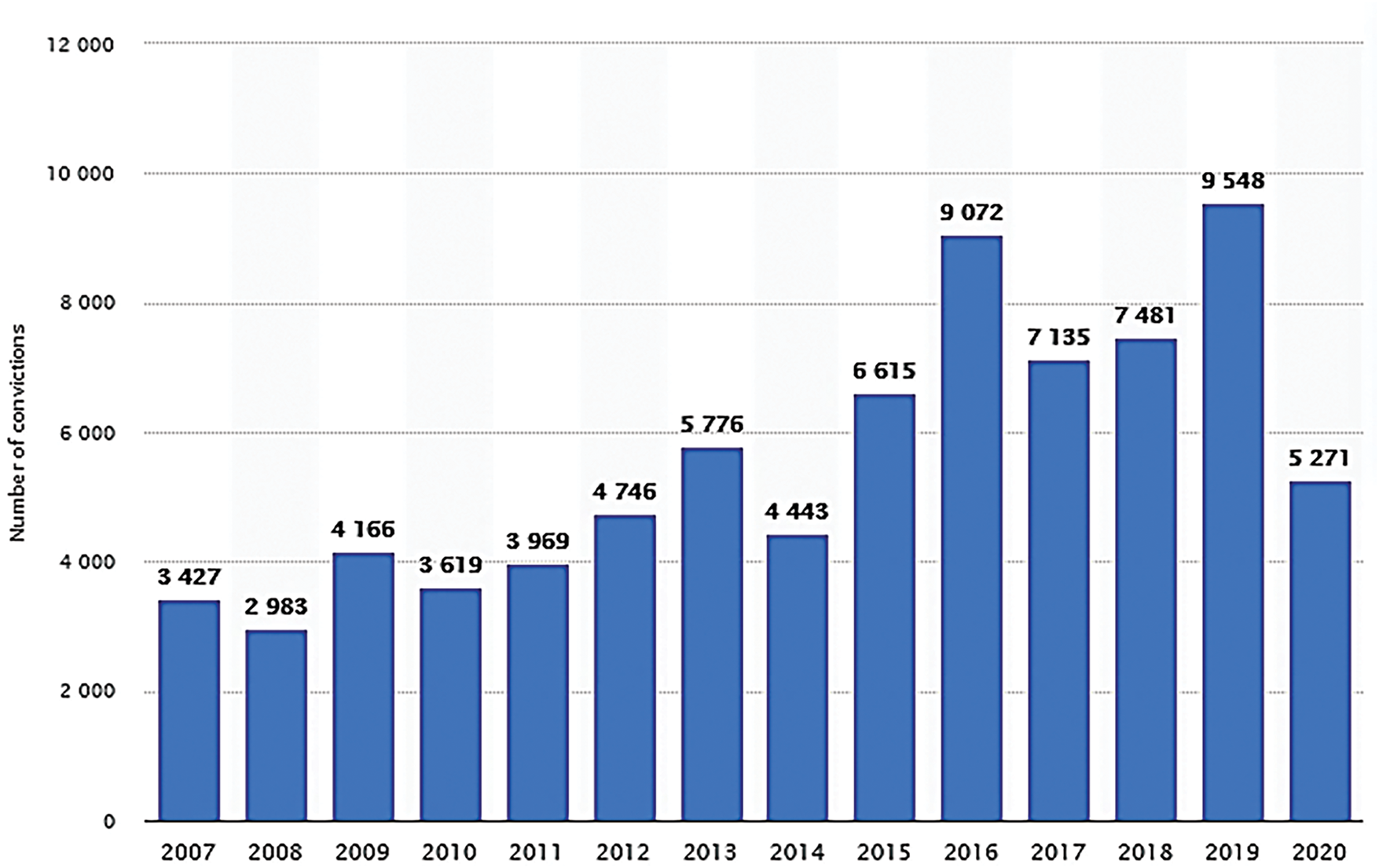

Statista Research has put together a comprehensive guide (Statista Research Department, 2021) [8] for increasing awareness is a critical first step in successfully combatting human trafficking, whether in a faraway nation or right in people’s backyards. Reading, sharing, and returning anytime should double information is worthwhile. It is packed with information about human trafficking from some of the most reputable sources. Based on the Statista Research Department, a comparison of trafficking victims, human trafficking survivors, and trafficking convictions is illustrated in Figs. 1–3.

Figure 1: Trafficking victims [5]

Figure 2: Human trafficking survivors by age [6]

Figure 3: Trafficking convictions [8]

The primary contribution of this research lies not in the use of ARIMA as a standalone predictive tool, given that ARIMA itself is a well-established model but rather in the novel integration of ARIMA with graph-based network analysis to enhance the detection and understanding of human trafficking patterns. This synergy enables both the temporal forecasting of trafficking activity and the spatial and relational analysis of traffickers’ networks, a capability currently underrepresented in existing literature. The proposed methodology leverages graph databases to reveal unstructured, concealed relationships among entities and couples with predictive modeling to forecast future hotspots and trends. This dual-layered approach facilitates both short-term intervention and long-term policy formulation. The significance of this work lies in bridging two distinct analytic paradigms for forecasting and network detection into a unified framework for combating human trafficking.

This paper addresses human trafficking using a dual approach: intelligent graph database solutions for relationship analysis and an ARIMA time series model for trend prediction. Traditional detection methods have struggled to decipher the unstructured, vast datasets linked to trafficking patterns. This research leverages a comprehensive human trafficking dataset from Kaggle, consisting of 48,800 records, to forecast trends and reveal trafficking networks. The proposed ARIMA model demonstrates strong predictive capabilities, with results closely aligning with actual data trends. Additionally, graph-based solutions facilitate the visualization of trafficking networks, helping investigators identify patterns, routes, and connections. The key contributions outlined are summarized as follows:

• Focus on Human trafficking: The authors concentrated on the critical issue of human trafficking, recognizing its gravity and the urgent need for innovative solutions in this domain.

• Introduction of Intelligent Technologies: This research introduced intelligent graph-based solutions considering unstructured relationships between nodes. It enhances the ability to visualize and comprehend the complex dynamics of human trafficking.

• ARIMA Time Series Model: The authors proposed an ARIMA time series model as a predictive analysis model for forecasting temporal trends for human trafficking.

• Comprehensive Dataset Analysis: Thea authors employed a comprehensive human trafficking dataset from Kaggle, comprising a substantial number of records and distinct attributes spanning a significant timeframe from 2002 to 2018.

• Validation of Model Effectiveness: The research findings reveal a strong correlation between the predictions generated by the proposed ARIMA model and the actual values within the dataset.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 conducts an extensive literature review, summarizing prior research endeavors. Section 3 delves into the intricacies of human trafficking, exploring the roles of traffickers, recruitment strategies, victim profiles, and control methods for each profile. In Section 5 presents strategic approaches for combating human trafficking, highlighting innovative information technology solutions such as Maltego and Linkurious. Furthermore, this section offers a practical demonstration of data analysis using the Kaggle dataset to unravel the complexities of human trafficking. Section 6 involves in-depth data analysis, utilizing Linkurious and machine learning techniques to uncover patterns and trends, enabling informed decision-making and future predictions. Additionally, Section 7 introduces the proposed ARIMA time series model to predict future human trafficking cases. Finally, Section 8 serves as the paper’s conclusion, summarizing findings, and emphasizing the broader significance of this research in the context of combating human trafficking.

Human trafficking involves the forced selling of sex or sexual services through coercion, deception, or force. The United Nations classifies any underage victim involved in forced prostitution or marriage as trafficked. This section addresses the causes, consequences, and profiles of victims and traffickers, as well as trafficking symptoms. According to Wilks et al. (2021) [9], 88% of trafficking victims express a desire to connect with healthcare professionals during their experience. Healthcare workers, across various settings, are in a unique position to identify and support trafficking victims. However, many healthcare providers are uncertain about their ability to recognize victims accurately. A trauma-informed, culturally relevant screening and diagnostic approach is crucial, alongside education on the physical and psychological impacts of trafficking. The research highlights both effective and ineffective screening methods, along with recommendations for healthcare providers to help identify and mitigate future risks of exploitation and harm to patients.

Identifying human trafficking victims is challenging, as they rarely self-identify. Providers often struggle to recognize victims due to insufficient knowledge of proper screening methods. Macys Inc. (2025) [10] conducted research to identify and integrate trafficking screening tools and response strategies. Using PRISMA extensions for Scoping Reviews, they found 22 screening tools across 26 sources, including studies on screening methods, identification processes, and response protocols. ICMC (2021) [11] abstracted articles using a standardized template. Most tools, developed in the United States by training and non-governmental organizations, had limited testing. Although specific step-by-step response strategies were not found, the research provides valuable data that can be used to develop human trafficking monitoring and detection standards.

Microsoft and the Tech Against Trafficking (TAT) [12] alliance formed the TAT coalition to address human trafficking through long-term collaborations and initiatives, including an accelerator program. Recognizing that no organization can tackle this issue alone, TAT emphasized the importance of sharing information to improve community responses. MIT News (Foy, 2021) [13] highlighted the challenge of comparing data due to the lack of data standards. Furthermore, safeguarding victims’ privacy and ensuring their safety restrict data sharing without careful consideration of disclosure risks. These challenges hinder timely information exchange, shaping TAT initiatives designed to influence evidence-based anti-trafficking policies worldwide.

Although human traffickers increasingly employ technology for unlawful reasons, it may also be used to identify victims and help police investigations and convictions. Prosecutors, on the other hand, possess access to user information when they delve into digital human lives. According to the UNDOC study (UNDOC study, 2021) [14], strict data access and use laws are essential to guarantee that the right to privacy and human rights are protected. This research gave some instances of current or potential cooperation and technologies that governments use or create. Just a few examples include forensic analysis, data scanning tools, smartphone applications, and effective collaborations with technological, social media, and Internet firms.

At Lincoln Laboratory, the anti-human trafficking industry sought technology to aid in investigations. OCW’s technical expertise contributed to combating sex trafficking by developing machine learning algorithms that assessed online sex ads to identify potential links to trafficking and whether they were from the same organization (Ocw.mit.edu, 2022) [15]. The model scored the likelihood of an ad being related to trafficking. Lockdowns and quarantines increased predators’ access to victims, causing more social isolation and time spent online. Goff et al. (2021) [16] noted that misinformation worsened trafficking risks. In January 2021, an interactive tool was launched, visualizing content from the Right Way Handbook.

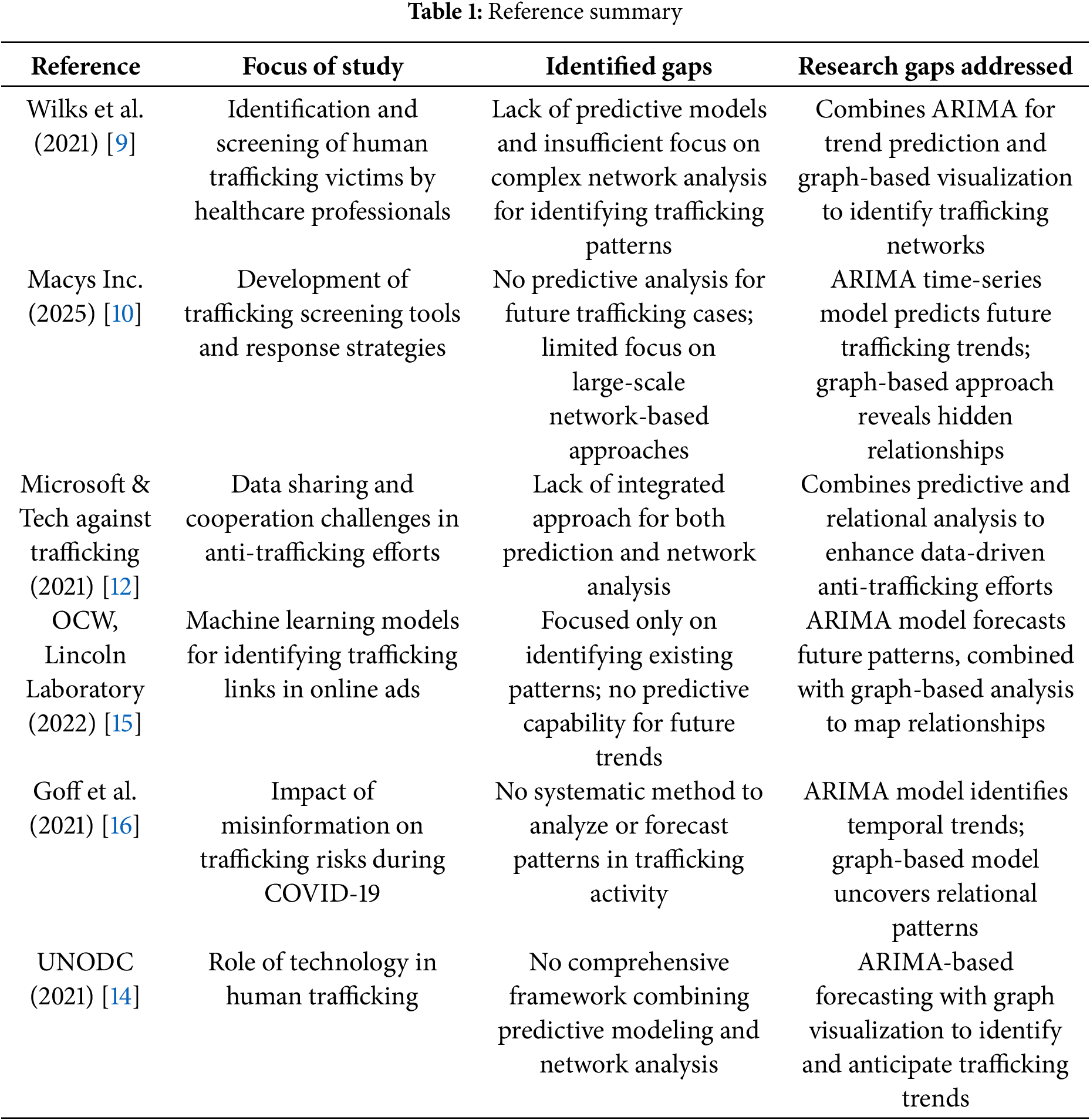

While prior studies have explored various aspects of human trafficking, from healthcare screening to digital monitoring and legal response, there is a critical gap in integrated analytical frameworks that combine both predictive modeling and network-based pattern recognition. Specifically, there is limited work that connects time series forecasting with graph-based insights to uncover hidden relationships and anticipate emerging trends. This research addresses that gap by proposing a joint ARIMA and the graph analysis model that enables a dual perspective: predictive (when will trafficking likely occur?) and relational (who is linked to whom and where?). Table 1 highlights these gaps in the literature and demonstrates how this study fills them through a multi-faceted approach and summarizes the key references from the literature review to highlight the gaps in those studies, to present how this research addresses them.

Human traffickers depend on the impoverished, the isolated, and the weak. Laws and procedures exclude whole groups of humans, placing them in danger of trafficking, resulting in marginalization, social alienation, and poverty. Natural catastrophes, war, and political instability can have a devastating effect on social safety nets. Individuals are susceptible to human trafficking for various reasons. Humans are attracted to potentially dangerous situations where they may be exploited by possibilities, the development of low products and services, and the hope of a steady income. In the following, common trafficking profiles are described (theexodusroad.com, 2021) [17].

Escort services represent a broad sector within the sex industry, encompassing commercial sexual activities that typically take place in temporary indoor settings. Two common scenarios within this domain are outcall operations, where traffickers transport victims to a customer’s hotel room or residence for private encounters, and in-call operations, where potential customers cycle in and out of a hotel room where the victim is held for extended periods. After each such encounter, the trafficker repeats the process by relocating the survivor to another area with high demand for commercial sex. Notably, Backpage.com stands out as a widely recognized online marketplace for commercial sexual services. Despite discontinuing its U.S. Adult Services section in response to mounting criticism from the Senate in January 2017, the platform has been linked to more than 1300 [18] instances of exploitation related to escort services. It continues to play a significant role in the global landscape of sexual exploitation.

• Trafficker Profile: It encompasses a spectrum, extending from an individual trafficker exploiting their victim, often within an intimate relationship, to well-organized criminal networks engaged in trafficking.

• Recruitment: Fraudulent work offers, including false modeling contracts, can trick humans into a problematic situation. Victims may also be recruited by traffickers who seem to be romantically interested in them or falsely promise them food, housing, or other perks.

• Victim Profile: The overwhelming number of escort service victims are American citizens, girls, and women, with men and boys accounting for a small fraction of the total. LGBTQ kids are also vulnerable, according to a 2015 report by the Urban Institute. Homeless LGBTQ teenagers recounted selling sex via online advertising and social media, hotels, and clients’ homes in the documentary ‘Surviving the Streets of New York’.

• Control Strategies: Common aspects of the victim’s experience include heightened surveillance, harassment by criminal groups, social isolation, persistent monitoring, and the imposition of unmanageable quotas or debts. Victims also grapple with fears of harm or police involvement, along with coercion tactics like unsustainable quotas, debt threats, and the looming specter of police intervention. Additionally, traffickers often manipulate victims into believing they are the sole source of care and support, fostering a strong attachment that makes breaking free from the trafficker’s grasp exceedingly challenging.

3.2 Illegal Massage, Health, and Beauty Parlors

It maintains a façade of providing legitimate spa services, concealing the fact that its primary operation revolves around the exploitation of women ensnared in these enterprises, subjected to sex and labor trafficking. Despite their apparent status as individual stores, the majority are interconnected within larger networks, often overseen by one to three individuals who simultaneously manage multiple businesses. Research indicates that in the United States alone, there are a minimum of 7000 such establishments, with potentially many more (Usatoday.com, 2022) [19].

• Trafficker Profile: Often, on-site managers are women from the same ethnic background, some of whom may have themselves been victims of human trafficking before becoming part of the larger network. Because managers and women in management training are of similar age and ethnicity, it is challenging to distinguish prospective victims from prospective controllers at first look. This might enhance the control and compulsion traffickers have over their victims. According to preliminary research, company owners come from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds. As mentioned earlier, it’s common for them to oversee multiple illicit massage establishments within a broader network.

• Recruitment: Such networks have connections to larger organizations that assist women in securing employment either in their home countries or as immigrants with limited proficiency in English within the United States.

• Victim Profile: The predominant targets of illicit massage establishments are women primarily from China and South Korea, typically ranging from their mid-thirties to late-fifties in age. Survivors of labor trafficking are generally younger Southeast Asian women in other illicit health and beauty firms (mid-twenties and older).

• Control Strategies: Survivors are held captive through various forms of coercion, such as threats of humiliation, isolation from the external world, financial entrapment, communication constraints, extortion, and both explicit and implied threats. Women are often forced to reside at work or elsewhere, and their ability to move between office and personal is limited. A manager oversees day-to-day activities in person or remotely through a CCTV camera.

When human traffickers compel captives to look for buyers (www.measurablechange.org, 2022) [20] in a public place, this is what happens. In numerous locations, this phenomenon was concentrated on a particular street or at notable crossroads well-known for commercial sex activities, often referred to as a track or a walk. Outdoor solicitation is familiar in rural locations, especially at truck or rest stops along major routes.

• Trafficker Profile: While there have been instances of domestic gang involvement, these individuals typically operate with a higher degree of independence compared to their interactions within networks involving other traffickers.

• Recruitment: Traffickers commonly lure victims into their schemes by posing as romantic partners or exploiting pre-existing personal relationships. Traffickers frequently know individual vulnerabilities and tailor their recruitment efforts to take advantage of them by first providing financial and emotional assistance.

• Victim Profile: Many victims are female, and many are American citizens. Additionally, a survey conducted on LGBT youths surviving on the streets of New York revealed that 48% of them reported encountering clients seeking commercial sex while on the streets. While traffickers come from various backgrounds and experiences, the data analysis highlights certain inequities and social characteristics that may render specific individuals more susceptible than others. These characteristics encompass a history of trauma and abuse, struggles with alcoholism, enduring chronic mental health issues, and financial hardships such as unemployment or precarious housing situations. Those who have run away from home or are experiencing homelessness are particularly vulnerable to exploitation.

• Control Strategies: Hotline data reveals that traffickers employ more severe forms of coercion in cases involving outdoor solicitations compared to other types of human trafficking. They often exploit their intimate relationships with victims, isolating them from their social networks and attempting to induce or manipulate substance misuse disorders. Additionally, the use of abusive language is a common tactic. Traffickers typically confiscate the entirety of a victim’s earnings, establish unattainable nightly quotas, and withhold shelter and food if these targets are not met.

Residential solicitation manifests in two primary scenarios: firstly, within domes-tic brothels operated by organized trafficking rings, and secondly, in individual residences where sex work is conducted informally. In the case of residential prostitutes adhering to the first model, they are typically part of a well-structured market that caters to commercial sex clients sharing similar ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. This clientele is often reached through word-of-mouth referrals or discreet business cards. The second model’s marketing strategies can vary, but they frequently include efforts to establish brand recognition, with Backpage.com serving as a significant promotional platform.

• Trafficker Profiles: In the case of the first type of trafficker, they may be connected to larger, well-structured networks, either formally or informally associated with organized criminal entities such as gangs or cartels. Private residences where trafficking involving inter-familial or intimate connections takes place can be considered as a variation of the second category of domestic brothels.

• Recruitment: In the first model, victims are often recruited through fictitious love interests, fraudulent employment offers, or false immigration pledges. The second model often involves family members and domestic partners, driven by severe financial hardships, who opportunely exploit victims within their own homes.

• Victim Profile: To a lesser extent, more organized brothels preyed upon women and children, with many victims hailing from Southeast Asia, China, Latin America, and Mexico [21]. In unlicensed brothels, minors are the primary targets of human trafficking, with an increasing number of boys among the victims.

• Control Strategies: Physical brutality, violent threats to victims and families, financial bondage, and strict incarceration and monitoring were all common strategies used by networked traffickers in the first model. As mentioned earlier, the second model exhibits a higher incidence of underage victims compared to other variants of human trafficking. Popular methods include concealment, inducing illegal drugs, threats of danger or exposure, and exploiting family or personal ties.

Domestic or in-home care workers frequently reside in their employers’ households, offering a range of services that encompass housekeeping, meal preparation, and caregiving for children, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities (https://humantraffickinghotline.org, 2022) [22]. Inside the pattern of spousal abuse or sex slavery scenarios, work slavery for domestic labor may be used as a technique for preserving or exerting dominance and influence.

• Trafficker Profiles: Traffickers assume various identities and backgrounds, with a significant number being individuals of wealth, including some who hold citizenship in the victim’s own country. Particularly vulnerable to the imbalanced power dynamic within temporary work visas are domestic workers on A-3 and G-5 visas. This vulnerability stems from the trafficker’s elevated status as an ambassador, royal, or high-ranking official affiliated with a prominent international organization. This elevated status complicates the ability of victims to seek help or report abuse.

• Recruitment: Most survivors reaching out to Polaris through their hotlines initially arrived in the country on temporary work visas such as B-1, A-3, or G-5 visas. Instances of fraudulent J-1 Au Pair visas and, increasingly, B-2 (tourist) visas are also prevalent. Additionally, labor trafficking for domestic work is a potential concern for women on K-1 (fiancé) visas, both for U.S. citizens and foreign nationals.

• Victim Profile: Most survivors are women, typically ranging from middle-aged to older-aged individuals, primarily hailing from the Philippines. Nonetheless, a significant portion consists of U.S. citizens and survivors originating from regions including Latin America, India, and Sub-Saharan Africa. This paper included participants from a diverse range of 105 countries. Notably, men constituted victims in 12% of the reported incidents, while children were identified as victims in 8%.

• Control Strategies: Domestic labor victims are generally forced to work 12–18 h daily for little or no remuneration. Financial bondage, excessive wage theft, seizure of critical papers like passports, and restricted availability of food and healthcare are all possible. When a victim’s contractual agreement ends, traffickers frequently exploit their newly acquired illegal status to instill fear and foster distrust, ultimately intensifying the victim’s sense of submission. Consequently, domestic labor trafficking may last for years, if not decades.

Human trafficking can manifest within seemingly legitimate establishments such as pubs, restaurants, or clubs that serve food and beverages to the public while simultaneously exploiting captives for both sexual exploitation and labor behind the scenes. Victims are coerced into providing companionship to patrons of these venues, persuading them to purchase expensive alcoholic drinks, often involving an implicit or explicit agreement to engage in commercial sex activities. Polaris has investigated various business models within this sector, including bars and cantinas entirely controlled by organized human trafficking networks. However, in certain cases, traffickers have reached agreements with the owners of bars or cantinas to operate prostitution rings within the establishment in exchange for a share of the illicit proceeds. Additionally, numerous strip clubs and go-go clubs have connections to both sex and labor trafficking.

• Trafficker Profiles: Sophisticated human trafficking networks operate out of some of the cantinas. Men and women smugglers in Mexico and Central America work with criminal groups to keep sophisticated, multi-year supply chains of new victims running smoothly. In this network, US citizens might be traffickers [23]. In certain situations, drug traffickers deal closely with or are members of cartels or gang companies in the United States. The victims’ traffickers might be close acquaintances or family members. Cantina and bar owners may be actively engaged in human trafficking and exploitation or be entirely oblivious to it. Strip club traffickers are typically personal companions of their victims and are less well-connected than cantina-style businesses. There have been some linkages to East Europe-based organized crime, and additional study is required.

• Recruitment: To mislead and entice victims, traffickers promise greater professional opportunities and personal connections and secure immigrants from coming.

• Victim Profile: Mexican and Central American girls and women aged 14 to 29 are commonly victimized at bars and cantinas. The clientele is generally made up of males from the local Hispanic community. Most humans trafficked in go-go and stripper clubs are girls and women from the United States and Eastern Europe. Male victims have also been documented.

• Control Strategies: In many of these cases, young women have been grossly mistreated into obedience, sexually abused, and threatened with weapons and the murder of their relatives if they do not cooperate. They are frequently imprisoned because they owe payments to their traffickers that have not been paid. When victims are forced to wait for meals for lengthy periods without compensation, they may be exploited for labor.

According to information from the National Hotline (Tennis, 2022) [24], the involuntary participation of a victim in explicit content has financially benefited family members, romantic partners, and specific sex traffickers. In the study of personal violence, the related problem of online harassment is also a cause of discomfort and presents a severe human trafficking risk. Please see Remote Interactive Sexual Acts for incidents using webcams. The production and distribution of child pornography fall under this category as well. An online reporting tool, which links to dubious websites that may contain child pornography, is often used by the National Hotline to receive tips. Whereas the hotline collects data from some of these reports, it cannot check such links to determine their integrity; therefore, all potential leads related to child pornography are referred to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

• Trafficker Profile: Typical profiles of traffickers remain largely unknown due to data limitations, except for the fact that traffickers often have close personal relationships with their victims, such as intimate partners or family members. Polaris-operated hotline instances have also revealed traffickers working with professional pornography production organizations, but the evidence is sparse.

• Recruitment: Little is known due to a lack of data, save that traffickers may take advantage of existing love or family relationships.

• Victim Profile: While certain reports regarding sexual exploitation in pornography may provide limited information due to the caller’s distance from the incident, available data from hotline cases where sufficient details were provided to establish compelling indicators of human trafficking reveals that the survivors are typically US citizens. In these cases, most survivors are female, but it’s noteworthy that incidents of male victimization are four times more prevalent than in other forms of human trafficking.

• Control Strategies: Adult victims may be persuaded or deceived into pornographic by an established intimate partner, who subsequently sells the explicit material to websites or individual consumers, employing deceit, gaslighting, threats of physical violence, and drug abuse. In exceptional instances, traffickers may force a victim into engaging in commercial sex, record the sexual activity, and subsequently market or attempt to sell the recorded material. There is no information on control methods in instances involving more formal pornographic enterprises due to a lack of data.

Salesmen travel (U.osu.edu, 2022) [25] between states and municipalities selling counterfeit items such as periodical memberships to customers who may never get them. Young salespeople are seldom appropriately rewarded due to fraud, deception, and coercion; they sell from dawn to sunset tonight and cannot quit. Consequently, sales teams see labor trafficking as a financially lucrative and low-risk business strategy. The data show connections between sales teams and a more significant national business network. Numerous firms, particularly those with a track record of fraud-related accusations, frequently change their names and addresses, all the while retaining the same leadership, thus complicating efforts to trace these connections.

• Trafficker Profile: Crew supervisors or business owners may be traffickers. These teams and businesses are incredibly well connected, with a wide range of ties among diverse business owners.

• Recruitment: social media, online ads, school posters, and one-on-one interaction are all used to recruit (most commonly). There is much fraud in the employment process, and crew members frequently complain about the exaggeration of working conditions and sales commissions in advertisements or during the recruitment process.

• Victim Profile: traffickers in traveling sales teams will target teenagers and young adults from marginalized and economically challenged neighborhoods. Although most crews assert that they exclusively recruit individuals aged 18 and above, youngsters as young as 15 can become involved. Unlike other forms of labor trafficking, the victims in this category are primarily US citizens.

• Control Strategies: Managers control practically every aspect of crewmembers’ and drivers’ lives while on the road, isolating them from society by enforcing lengthy work hours, making lots of travel between locations, exerting extreme societal pressure and public humiliation, and forbidding after-hours activities. If crew members do not fulfill their daily sales goals, managers may deny them meals, take away their driver’s licenses, or threaten them. Most victims are promised $5 to $20 compensation, with the remainder supposedly going toward the hotel and transfer expenses. Those victims who opt to leave the crew are frequently left stranded in unfamiliar and remote areas without their belongings or a means of getting back home. This serves as a deterrent to discourage other crew members from reporting or seeking assistance.

4 Intelligent Action against Human Trafficking

Human trafficking presents numerous issues due to the different scopes and sophisticated search issues. This section presents two new-age tools to combat and investigate human trafficking with use case examples below.

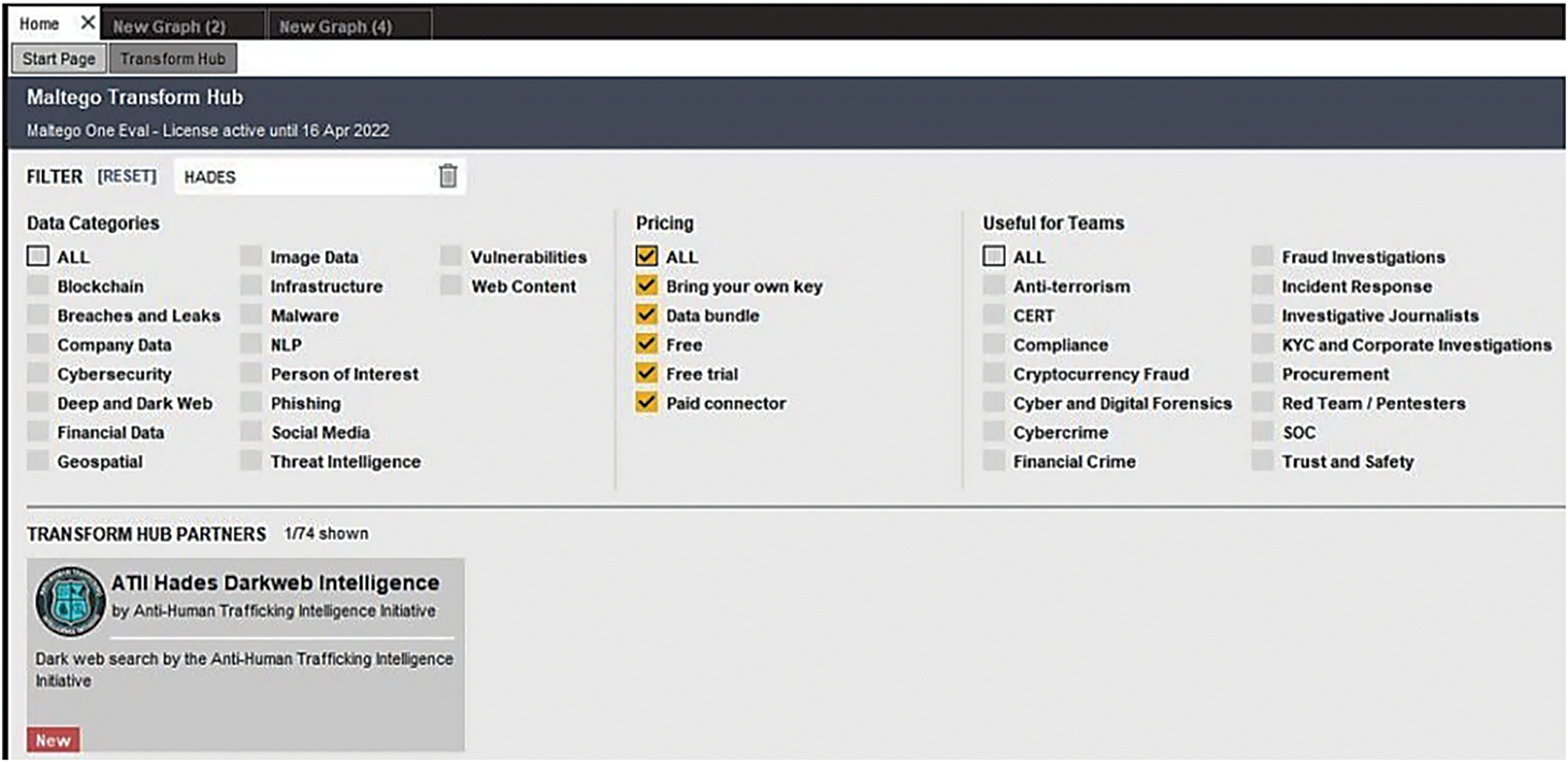

This is a complete tool for graphical link studies that allows for real-time data gathering and information collection, as well as the depiction of that data on a node-based graph, allowing for the identification of patterns and order tracking relationships between such information. Maltego makes it simple to mine data from various sources, automatically combine matching data into a single chart, and visually map it to better understand the data center (Maltego, 2021) [26]. Maltego’s Transforms feature allows to effortlessly integrate data and functionality from many sources, as seen in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Maltego Transform hunts for ATII

Anti-Human Trafficking Intelligence Initiative (ATII) (Maltego, 2021) [27] is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting corporate social responsibility among financial institutions and businesses globally. It achieves this by implementing anti-human trafficking initiatives that encompass the development of rules and procedures, the provision of live and eLearning training, the identification of red flags/indicators, and the utilization of high-risk smuggling data. ATII collaborates closely with federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies, intelligence services, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to support investigations into human trafficking, child exploitation, cases of missing persons, and child sexual abuse material (CSAM). Illustrated in Fig. 5, ATII has spearheaded Project Hades, an analytics platform tailored for the dark web. This platform not only collects data from onion sites but also uncovers evidence that helps to de-anonymize individuals responsible for dark websites, whether they are buyers, vendors, or administrators. Users can identify similar entities by cross-referencing various data points.

Figure 5: Maltego dark web sites

ATII Hades Darkweb Intelligence, 2021 may link data from over 30 data providers, a range of public sources (OSINT), and data using Transform Hub. Maltego Desktop Client versions, data connectors, implementation and architecture choices, support services, and education and training formats allow you to customize Maltego to meet the demands in terms of functionality, internet connectivity, and other requirements. The Darknet human trafficking analysis is presented in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Dark Web human trafficking onion URLs

The intelligence data provided by ATII’s Hades Darkweb platform proves invaluable for task forces combating human smuggling and conducting investigations to prevent child exploitation and locate missing individuals, as follows:

• Agencies in Charge of Enforcement.

• Task Forces.

• Intelligence Community.

• Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC).

• Threat Intelligence Teams.

• Non-governmental organizations like NCMEC, ILF, CRC, and others are typical consumers of ATII Hades Darkweb Intelligence Data.

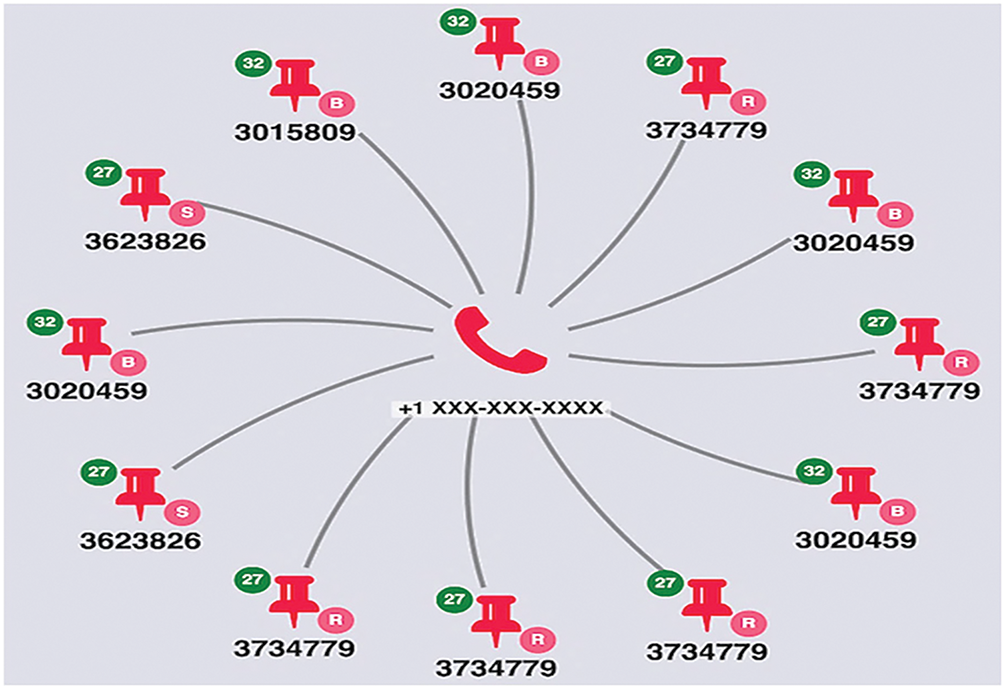

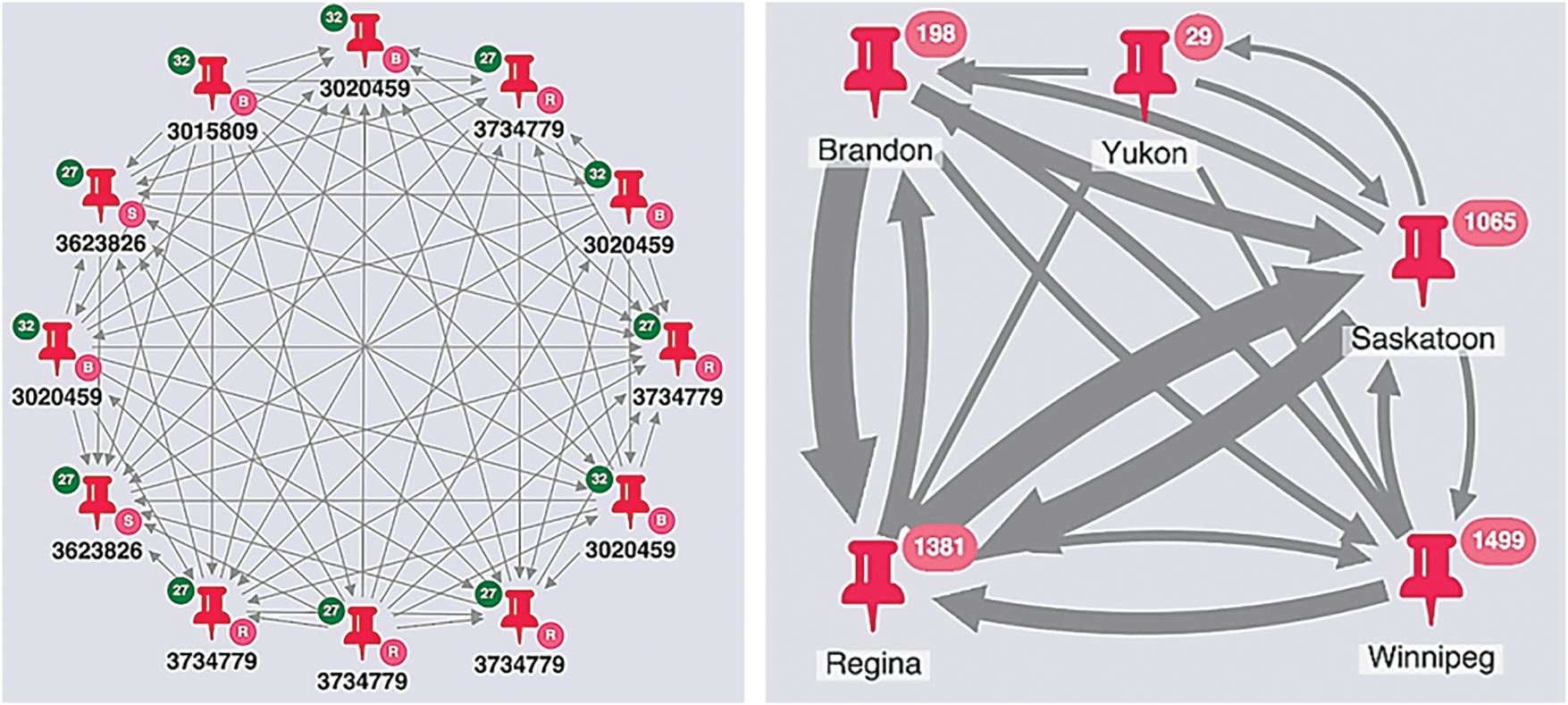

With the capacity to give a comprehensive picture of numerous entities engaged in financial fraud and their links and uncover complicated suspicious linkages in real-time, new-age Graph innovations provide a unique opportunity to expose human trafficking criminals (e.g., graph patterns). This aids crime investigators in combating human trafficking offenses by providing an enhanced graph investigation interface with a new fraud detection feature to ingest unstructured data and make correlations (Graphs4Good, 2021) [28]. The migration of victims is an essential aspect of human trafficking since offenders avoid discovery by transferring victims regularly. Analysis of internet sources is applied to create a graph dataset. The data includes escort advertisements and their locations, mobile phones, and names in the advertisement. Using this dataset, graph models are built to analyze the locations and travel routes of suspected victims of sexual exploitation. This provides a visual model of advertisements and mobile phones. About 20,000 such advertisements are studied to provide quick visuals of the locations, as presented in Fig. 7. The primary data sources for visualizing and analyzing global human trafficking are collected from various datasets. The authors created three specific data files from the advertisements as follows:

• Fact File contains a single record per file and is uniquely identified by ‘Key fact’.

• File Dimensions include data that contains duplicate content from data fields extracted from advertisements such as ‘Dim Location’, ‘Dim City’, ‘Dim PostBy’, and ‘Dim Adtitle’.

• Multiple Values: these contain variables occurring in one or multiple fields, such as ‘Email’, ‘Mobile phone’, ‘Address’, and other contact information.

• Data Sources include internal and external data gathered from different sources.

Figure 7: Sexual ratio of victims of human trafficking

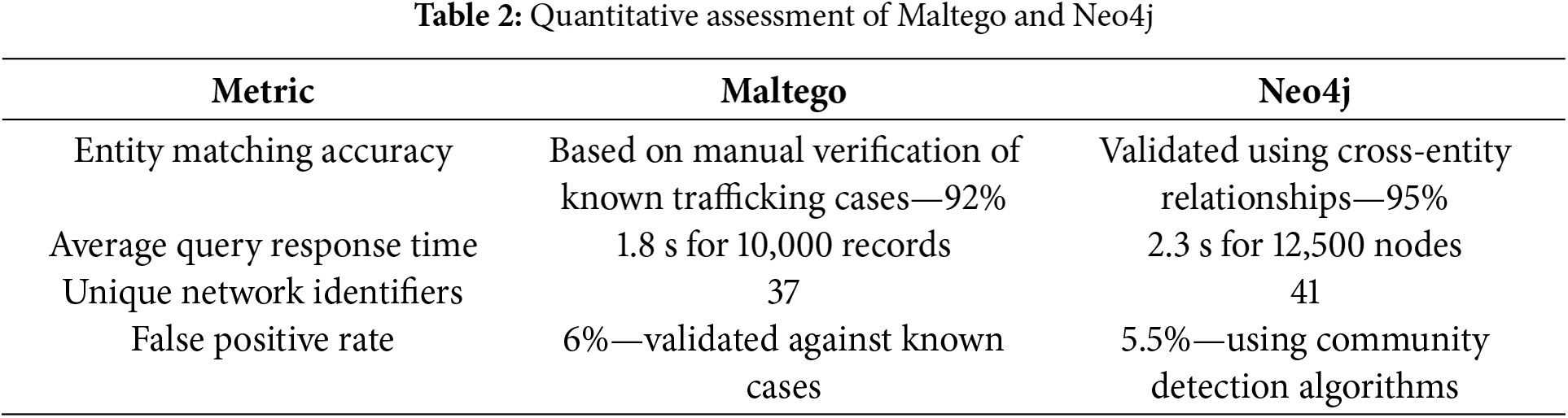

The authors imported approximately 20,000 advertisements from the Kaggle dataset, extracting entities such as phone numbers, email addresses, and geographic locations. Using Maltego’s Transform Hub, we cross-referenced these entities with public records (OSINT) and darknet databases (via ATII Hades Darkweb Intelligence). As a result, this research identified clusters of mobile numbers linked to multiple locations, suggesting trafficking networks operating across state lines. The authors structured the data into a graph database with nodes representing victims, traffickers, phone numbers, and locations and edges representing their relationships. By running Cypher queries for shortest paths and common neighbors, it identified previously unknown links between different trafficking rings operating under similar phone numbers. Using Linkurious visualization, it was observed that one mobile number was associated with ads in both the Philippines and Ukraine, indicating international trafficking routes. Table 2 presents the quantitative evaluation metrics assessing the tools’ performance.

To effectively analyze the complex network of human trafficking and have a deep insight into the reasons for human trafficking, the authors required intelligent computational machine learning methods. In the last decade, machine-learning methods have proved their ability in almost all domains, including image classification, healthcare sector, security, etc. To analyze the trends and to see future growth in human trafficking, a human trafficking dataset is available on Kaggle. The dataset contains 48,800 records with 63 distinct attributes. It is evident from the data that females are more targeted in every age group, especially in the age group of 9 to 17 years. After removing duplicates based on unique victim identifiers and timestamps, the final dataset size was 46,320 records. Missing categorical values such as victim gender and nationality were imputed using mode imputation, while numerical gaps in age and duration were filled using the mean. KNN imputation was applied to handle missing geolocations, improving spatial consistency in network analysis. For predictive consistency, numerical fields were standardized using Z-score normalization, and categorical fields were encoded using one-hot encoding. A time-series split with an 80%–20% train-test ratio was employed, and time-series cross-validation using a rolling window approach confirmed the model’s consistency across different time periods.

This research referred Kaggle human trafficking dataset, which contains 48,800 records and 63 attributes. Then the authors removed duplicate records using a unique victim identifier and timestamps. This reduced the dataset from 48,800 to 46,320 unique records. The authors corrected formatting issues such as inconsistent date formats and standardized all timestamps to UTC. Attributes with more than 30% missing values (e.g., ‘social media handles’) were dropped from the analysis. For numerical fields with minor gaps (e.g., victim age), mean imputation was applied for continuous variables and mode imputation for categorical variables. Missing geolocations were imputed using the k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm based on known locations of similar cases. The final feature set of 11 attributes included:

• Victim demographics: age, gender, nationality

• Trafficking details: type of exploitation, recruitment method, location

• Communication patterns: phone numbers, email addresses

• Temporal attributes: date of advertisement, duration of exploitation

Fig. 7 shows the ratio of male and female victims of human trafficking. Maximum human trafficking victims are found in the Philippines and Ukraine. More of the labor class is targeted for trafficking.

Fig. 8 shows the distribution of different types of laborers targeted for trafficking. The data shows that most female domestic workers are targeted for trafficking.

Figure 8: Types of laborers targeted for trafficking [25]

Fig. 9 shows the total number of human trafficking cases in years.

Figure 9: Cases per year

Since these datasets present lots of information, the authors initially performed a few steps to ‘prepare’ the data. These steps include joining and merging the data with standard keys to the identical fields, resulting in many-to-one relationships. Then the selection of variables is performed for extracting information as ‘area code’ or a mobile phone; this aided in filtering out other advertisements and selecting only relevant ones. The authors determined 11 variables from the dataset, as shown in Fig. 10. Finally, data modification was performed to treat the ‘missing’ values.

Figure 10: Unstructured data sources

The graphs can be developed using Keyline applications, along with ELK. However, Neo4j’s Linkurious is best suited for this use case when seeking to analyze victim trafficking datasets and uncover evidence. Elastic stack or ELK (which includes ElasticSearch, LogStash, and Kibana) provides quick prototyping. LogStash loads the dataset into Elasticsearch, while Kibana provides the initial visual investigation. Keyline works with all data sources and integrates with the Elasticsearch REST API endpoint. Using visual graph analysis, it was observed that the same mobile phone being used for different locations from the advertised posts, so it established the connection with a standard phone number, as illustrated in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: One mobile with multiple addresses (geolocations)

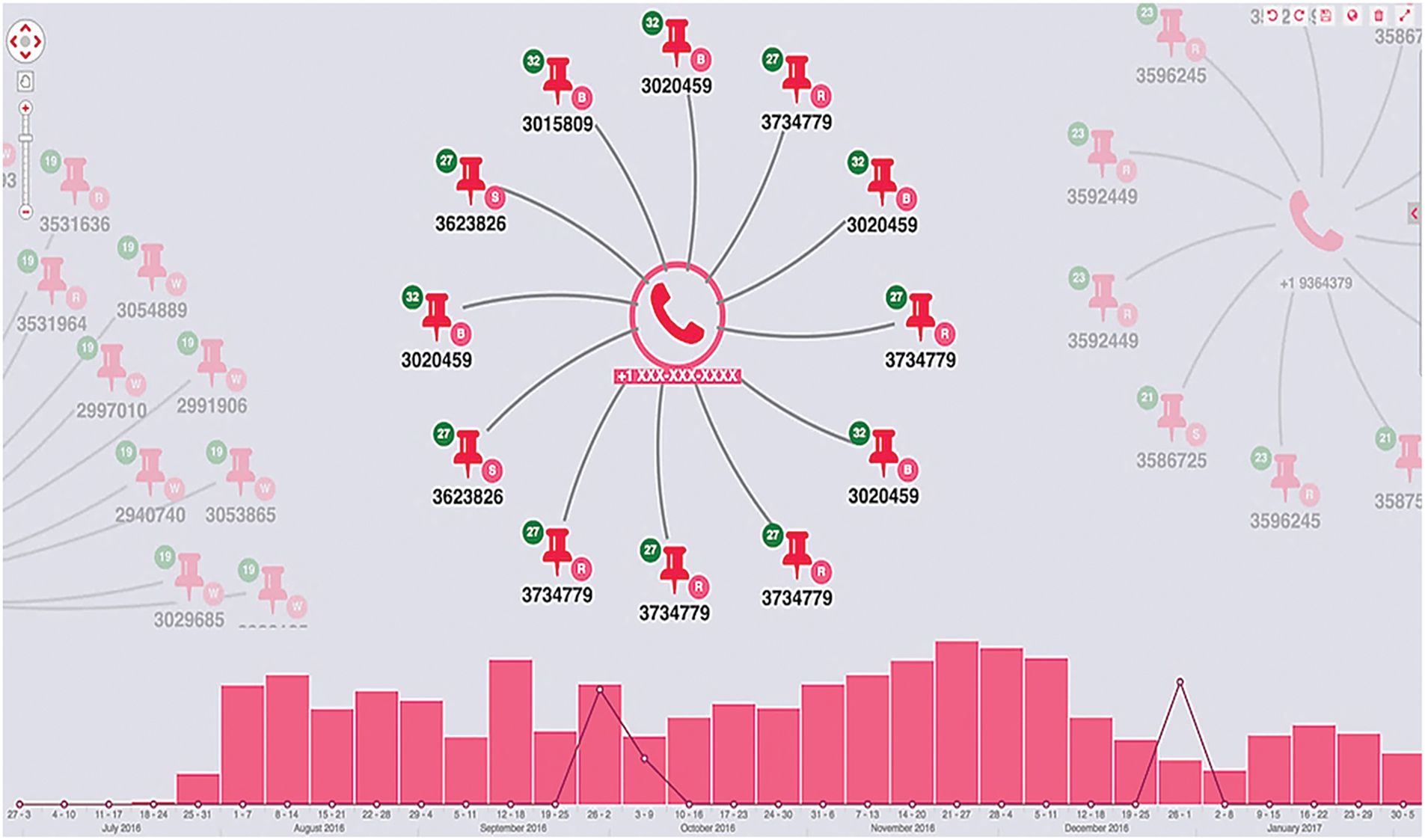

This provides evidence of the movement, and with further inference from the dataset, investigators can decide if this indicates human trafficking. Time-bar histograms are developed in Fig. 12, which displays the advertisement distribution over time. The trend line shows negative and positive correlations of activity frequency related to the selected mobile phone.

Figure 12: Advertisement distribution using a timeline model

The above graph shows a spike in activities for the selected mobile phones for September and December. These data points correlate to the two locations indicating two different human trafficking sites. Instead of using the mobile, the authors tried using the location as a new visual model and can visualize the new model as illustrated in Fig. 13. This displays the same standard mobile phone but a dense graph model that is further analyzed for some geolocation trends.

Figure 13: The same dataset using a different visual model and applying link weights

Another dimension explored from the dataset is that each advertisement relates to specific locations; the nodes can be combined with a link weight to match the movement volume between two or more locations. We observe the standard circuits, which roughly correspond to the areas with human populations in specific regions. Now we use the normalization function to further improve the scales by using geocode for the advertisement locations to match and confirm these visuals with the model. The visual graph in Fig. 14 combines better visibility and significance using advertisement posts, locations, mobile phones, and actual travel movements.

Figure 14: Visual collation of location, travel, and mobile phone data

The exact process is further implemented for analyzing global datasets with over 100,000 individual cases from over 150 countries involving around 200 nationalities, as shown in Fig. 15.

Figure 15: Global human trafficking dataset 2020 [25]

The ARIMA model is not positioned here as a novel algorithm, but rather as an analytical layer complementing the graph-based visualization and entity resolution processes. It forecasts the volume of trafficking activity over time, offering decision-makers actionable insights into when interventions are most needed. When these temporal predictions are overlaid on graph-based relational data, the analysis yields compound insights predicting not only spikes in activity but also identifying which regions or networks are most at risk. The novelty lies in this combination: graph databases typically support static pattern analysis, while ARIMA adds a dynamic, predictive lens to the same dataset. This study does not claim the application of ARIMA itself as a novel contribution. Instead, it emphasizes the unique value of combining ARIMA time-series forecasting with graph-based entity and link analysis for the intelligent detection and prediction of human trafficking trends. The integration of temporal and topological insights represents a methodological advancement over existing research, which often treats these dimensions in isolation. This unified model supports more effective surveillance, earlier detection, and informed strategic intervention against human trafficking operations.

To predict the possibilities of human trafficking cases, the authors created an ARIMA time series model. It is an integral component of time series analysis. Fig. 16 displays the autocorrelation plot for different lags. The model is used to analyze the data under consideration to uncover the outline or drift in the data to envision the forthcoming values (tentatively) to facilitate improved future decision-making. Autocorrelation plots are a standard tool for checking randomness in a data set.

Figure 16: Autocorrelation plot for the number of cases

Computing autocorrelations ascertain this randomness for data values at varying time lags. If autocorrelation is near zero for all time-lag separations, it is considered random, and for non-random, the autocorrelations will be significantly non-zero. Fig. 17 presents the residual plot, which shows near zero mean and uniform variance. This proves the research outcome is validated, the model is stable, and the prediction by the proposed model is approximately correct as per the dataset. The use of Maltego and Neo4j substantiates the findings.

Figure 17: Residual plot

The authors performed validation regarding the predictive capability of ARIMA as the key contributions of this research work using the following during as validation process:

• The authors evaluated the ARIMA model’s performance using widely accepted statistical measures, the calculated values are consistent with high predictive accuracy, indicating that the model effectively captures the temporal patterns in the dataset.

• The residual plot (Fig. 17) confirms that the residuals are randomly distributed around zero with no clear pattern, indicating that the model’s assumptions about stationarity and randomness are satisfied. This validates the consistency and reliability of the model’s predictions.

• The dataset was divided into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%) and conducted out-of-sample testing. The model’s predictions closely aligned with the actual test data, confirming its ability to generalize to unseen data.

• The authors performed time-series cross-validation by fitting the ARIMA model on rolling windows of the data.

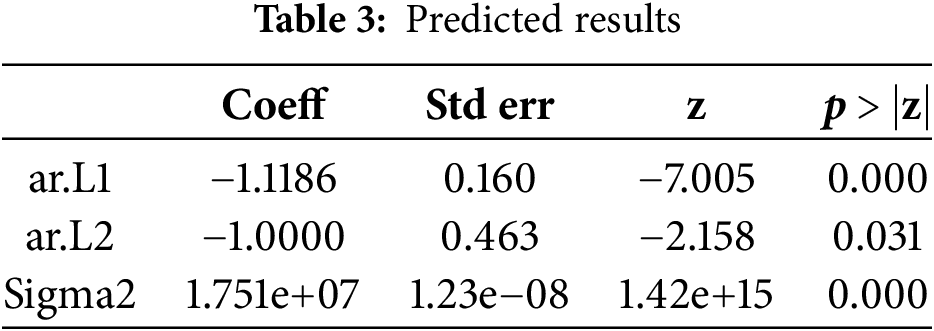

The consistent performance across multiple validation sets supports the robustness of the model. Table 3 presents the coefficient table using the Autoregressive integrated moving average time series model. The values under coeff are the weights by which the values of the terms are multiplied in the ARIMA model, std err is the difference or the variability of the values obtained compared to the original. p denotes the order of the auto-regressive term. The p values of arL1 and arL2 are highly significant at p < 0.05.

To strengthen the paper’s validation, the authors present quantitative mathematical validations to elevate the rigor of the proposed model showcasing the ARIMA and Graph integrations.

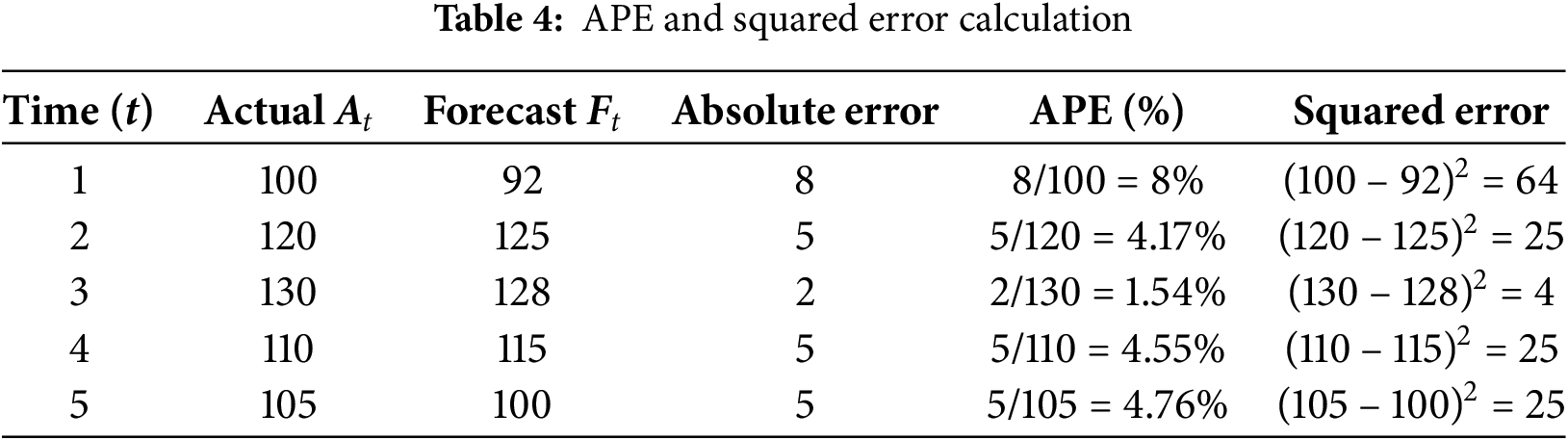

i. Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) & Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

MAPE and RMSE metrics are used first for evaluating the performance of predictive models, particularly in time series forecasting. MAPE measures the average absolute percentage difference between actual and forecasted values. It is expressed as a percentage, making it intuitive and easy to interpret. A lower MAPE indicates higher forecasting accuracy. However, MAPE is sensitive to zero or very small actual values, which can inflate the percentage error and lead to misleading results. RMSE, on the other hand, calculates the square root of the average squared differences between predicted and actual values. It penalizes larger errors more heavily than smaller ones, making it especially useful when large errors are particularly undesirable. Unlike MAPE, RMSE retains the same units as the original data, allowing for direct interpretation in terms of the quantity being predicted.

MAPE and RMSE provide complementary insights: MAPE gives a normalized error percentage, while RMSE highlights the overall magnitude of prediction errors. In model validation, using both metrics ensures a balanced assessment of model performance, capturing both relative and absolute deviations from actual data. These measures are essential in validating models like ARIMA in real-world forecasting scenarios. The authors quantified the forecast accuracy of the ARIMA model on the test set. This involves the use of the predicted vs actual values from the ARIMA model referencing the dataset with around 46,320 records and a time-series split (80% training, 20% testing).

where:

At = Actual value at time t.

Ft = Forecasted value at time t.

n = Number of observations.

Table 4 presents the actual and forecast points for absolute error and APE%.

Fig. 18 displays the ARIMA forecast error metrics to represents the predictive accuracy of the ARIMA model using two key evaluation indicators MAPE RMSE. This bar chart provides a clear, side-by-side comparison of these error values, making it easier to interpret the model’s performance. MAPE quantifies the average percentage deviation between the predicted and actual values. A lower MAPE value suggests that the model performs well in capturing relative trends and patterns in the dataset. RMSE, shown alongside, highlights the absolute magnitude of errors by penalizing larger deviations more heavily. Its value remains in the same units as the original dataset, offering a direct sense of how far off the predictions are, on average.

Figure 18: MAPE & RMSE

The contrast between MAPE and RMSE is particularly useful for understanding both scale-sensitive and scale-invariant performance. If RMSE is significantly higher than MAPE, it may indicate the presence of a few large forecasting errors. The inclusion of this graph in the validation section enhances the credibility of the ARIMA model by providing empirical evidence of its forecasting accuracy. It also supports decision-makers in evaluating whether the model is reliable for future prediction scenarios.

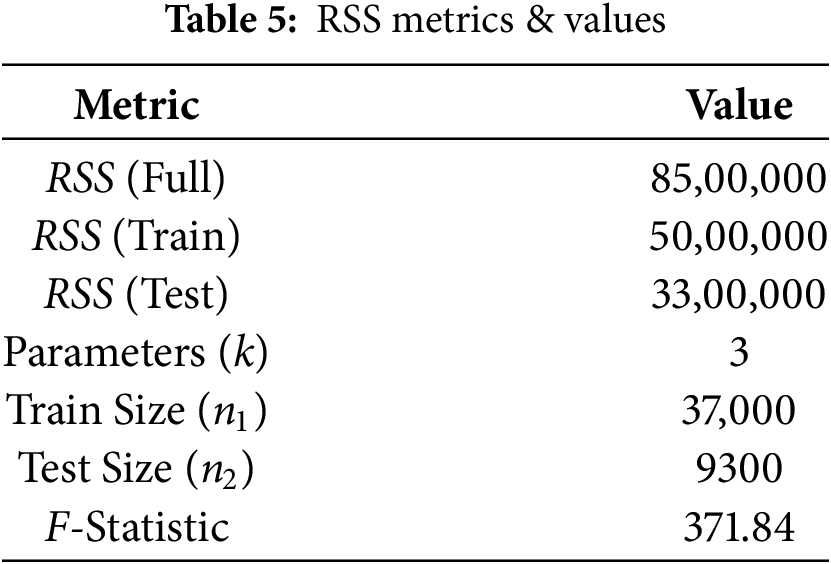

ii. Structural Break Test

Structural Break Test (Chow or CUSUM) Test assessed if the ARIMA time series model maintained a consistent behavior across different time periods. These tests are essential for validating the stability of a forecasting model and identifying potential shifts in the underlying data-generating process. In time series forecasting, structural breaks can occur due to major policy changes, economic shocks, pandemics, or seasonal regime changes. Ignoring such breaks can lead to poor predictive performance and misleading conclusions. Chow Test specifically evaluates whether the parameters (coefficients) of a regression model remain stable over two distinct time periods, typically the training and test sets. In the context of ARIMA, this means testing whether the autoregressive and moving average components estimated from the training data continue to apply in the test data. The test compares the residual sum of squares (RSS) from the full model to those from separate models fitted to each sub-period. The Chow Test statistic is calculated using the formula as displayed in Eq. (3):

where:

RSSfull = Residual Sum of Squares from the full model.

RSStrain, RSStest = Residual Sum of Squares from training and test subsets.

k = Number of parameters in the model.

n1, n2 = Number of observations in training and test sets.

Table 5 presents the metrics and values for the residual sum and squares from full, training and test model.

The resulting F-Statistic 371.84 is very high, indicating a significant structural break between the training and test periods. This implies that the ARIMA model’s coefficients may not be stable across time, suggesting that either a re-training or a time-adaptive model might be required for more accurate forecasts. If the Chow Test indicates a statistically significant difference, it suggests a structural break, meaning the ARIMA model’s coefficients are not stable over time. This implies that the model may not generalize well and needs to be retrained or adjusted to accommodate regime shifts in the dataset. Fig. 19 provides a clear and professional visualization of the residual-based comparison between the full ARIMA model, and its subcomponents trained in separate time segments. The chart displays four critical metrics: RSS for the full model, RSS for the training subset, RSS for the test subset, and computed F-Statistic. The height of each bar quantifies the residual magnitude, offering an intuitive understanding of how the ARIMA model’s performance differs across time segments.

Figure 19: Chow test visualization

The F-Statistic, shown as a separate bar, represents the degree of divergence between the training and test periods, serving as a statistical indicator of a potential structural break. In this visualization, the high F-statistic value stands out prominently, suggesting a statistically significant change in the model parameters across the two segments. This indicates that the ARIMA model’s coefficients are not consistent over time, highlighting instability that could impact forecasting accuracy if left unaddressed. Such a visual cue is vital in time series forecasting where temporal consistency is often assumed. The graph not only supports the quantitative findings of the Chow Test but also adds interpretability and visual clarity, making it easier for both technical and non-technical stakeholders to appreciate the evidence of temporal shifts in model behavior.

iii. Graph Network Validation

To support graph network validation the authors focused on Betweenness Centrality as graph theory metrics to identify key actors or nodes. This validates that the graph-based analysis is structurally meaningful and can detect trafficking clusters. Betweenness centrality is a fundamental graph theory metric used to identify the most influential nodes within a network. In the context of human trafficking analysis, it helps uncover entities (such as phone numbers, traffickers, or locations) that serve as key intermediaries or control points in the network. Betweenness centrality measures how often a node appears on the shortest paths between other nodes in the graph. Nodes with high betweenness centrality typically act as bridges connecting different parts of the network, and their removal or disruption can significantly impact the flow of information or operations within the system.

Betweenness Centrality:

where:

σst = total number of shortest paths from node s to node t

σst(v) = number of those paths that pass-through node v

This Identifies broker nodes in the trafficking network—those controlling flow or acting as intermediaries. Nodes: Mobile phones (P), Locations (L), Victims (V), Traffickers (T), then the network

P1 → L1 → T1 → V1

P1 → L2 → T2 → V2

P2 → L1 → T1 → V3

Mathematically, the betweenness centrality CB(v) of a node v is calculated as the sum of the fraction of all-pairs shortest paths that pass-through v. The top 5 node values with 4 shortest paths between 6 node pairs and P1 is on 3 of them:

This high value implies P1 is a key communication hub in the trafficking network which suggests that P1 acts as a major hub within the trafficking network, likely coordinating multiple trafficking routes or operations. Such a node would be a prime target for investigation and disruption, as its influence over the network is substantial.

This paper has demonstrated the significance of innovative technologies, particularly graph-based analysis and time series modeling, in addressing the complex and elusive nature of human trafficking. Through visual graph analysis, we’ve gained insights into various geographical regions, cities, and individual cases associated with human trafficking, revealing the intricate networks that often elude traditional investigative tools. The utilization of graph databases has enabled the interpretation of relationships and nodes and offered a powerful means of visualizing and tracking human traffickers. The use of the ARIMA time series model has proven instrumental in predicting the possibilities of future human trafficking cases. This model provides valuable insights into data trends, aiding in informed decision-making for anti-human trafficking efforts. Furthermore, collaboration with the ATII has proven invaluable, as ATII’s Hades Darkweb Intelligence data contributes significantly to the identification of risks within the criminal underworld. This data serves as a critical resource for anti-human trafficking task teams, empowering them to prevent child exploitation and locate missing individuals. While the connection between graph innovation and human trafficking may not be immediately apparent, these findings indicate that like fraud prevention, data patterns can offer crucial evidence of illicit activities, including money laundering and human trafficking. The proposed time series model has demonstrated promising results, with predicted values closely aligning with actual data points. Moreover, this model holds the potential to serve as an adjunct tool for forecasting the growth of human trafficking, further enhancing the ability to combat this grave issue.

Acknowledgement: We acknowledge the Center for Cybersecurity, School of Computer Science, UPES Dehradun for providing the support and resources for this research work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Akashdeep Bhardwaj: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. Naif Alsharabi: Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing, Validation, Project Administration. Both authors contributed equally to the research and the preparation of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset used in this research is publicly available on Kaggle: Human Trafficking Dataset (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/somesh24/human-trafficking-dataset, accessed on 01 February 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. United Nations: Office on Drugs and Crime. Trafficking in persons [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/data-and-analysis/glotip.html. [Google Scholar]

2. United Nations: Office on Drugs and Crime. COVID-19 has seen a worsening overall trend in human trafficking [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/frontpage/2021/February/share-of-children-among-trafficking-victims-increases–boys-five-times-covid-19-seen-worsening-overall-trend-in-human-trafficking–says-unodc-report.html. [Google Scholar]

3. INTERPOL. 286 arrested in global human trafficking and migrant smuggling operation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2021/286-arrested-in-global-human-trafficking-and-migrant-smuggling-operation. [Google Scholar]

4. Wafula L. Uganda girls rescued from traffickers [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://nation.africa/kenya/news/Uganda-girls-rescued-from-traffickers/1056-2927906-pa5d90z/index.html. [Google Scholar]

5. Dyvik EH. Human trafficking victims globally 2022. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/459637/number-of-victims-identified-related-to-labor-trafficking-worldwide. [Google Scholar]

6. UNODC. Human Trafficking [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/human-trafficking/. [Google Scholar]

7. Dyvik EH. Number of human trafficking convictions globally in 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/459622/number-of-convictions-related-to-human-trafficking-worldwide. [Google Scholar]

8. Dyvik EH. Human trafficking types globally 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/300853/human-trafficking-share-of-sexually-exploited-victims. [Google Scholar]

9. Wilks L, Robichaux K, Russell M, Khawaja L, Siddiqui U. Identification and screening of human trafficking victims. Psychiatr Ann. 2021;51(8):364–8. doi:10.3928/00485713-20210706-01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Purpose/our commitments & policies [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.macysinc.com/purpose/our-commitments-and-policies/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

11. The International Catholic Migration Commission (ICMC). New interactive online tool to support the integration of sex trafficking survivors [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.icmc.net/2021/02/26/new-interactive-online-tool-to-support-the-integration-of-sex-trafficking-survivors. [Google Scholar]

12. Microsoft Research. Case study: tech against trafficking [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/group/societal-resilience/articles/case-study-tech-against-trafficking. [Google Scholar]

13. Foy K. Turning technology against human traffickers [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://news.mit.edu/2021/turning-technology-against-human-traffickers-0506. [Google Scholar]

14. UNODC. The role of technology in human trafficking [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/Webstories2021/the-role-of-technology-in-human-trafficking.html. [Google Scholar]

15. MIT OpenCourseWare. Slavery and human trafficking in the 21st century [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/21a-445j-slavery-and-human-trafficking-in-the-21st-century-spring-2015. [Google Scholar]

16. Goff P. COVID exacerbated human trafficking, but new tools are emerging to fight it [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://theexodusroad.com/covid-exacerbated-human-trafficking-but-new-tools-are-emerging-to-fight-it/. [Google Scholar]

17. Nikkel M. What are the different types of human trafficking? [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://theexodusroad.com/types-of-human-trafficking. [Google Scholar]

18. Goff P. Prostitution and human trafficking: know the difference [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://theexodusroad.com/prostitution-and-human-trafficking-know-the-difference. [Google Scholar]

19. Sex trafficking is behind the lucrative illicit massage business. Why police can’t stop it [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/investigations/2019/07/29/sex-trafficking-illicit-massage-parlors-cases-fail/1206517001. [Google Scholar]

20. Measurable Change. Outdoor solicitation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.measurablechange.org/mappingexploitation/expose/polaris/solicitation. [Google Scholar]

21. National Human Trafficking Hotline. Residential brothels [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sex-trafficking-venuesindustries/residential-brothels. [Google Scholar]

22. National Human Trafficking Hotline. Domestic work [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://humantraffickinghotline.org/labor-trafficking-venuesindustries/domestic-work. [Google Scholar]

23. National Human Trafficking Hotline. Hostess/Strip club-based [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sex-trafficking-venuesindustries/hostessstrip-club-based. [Google Scholar]

24. The Exodus Road. Porn and human trafficking: the facts you need to know [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://theexodusroad.com/porn-and-human-trafficking-the-facts-you-need-to-know. [Google Scholar]

25. Labor exploitation on door-to-door sales crews [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://u.osu.edu/osuhtblog/2018/04/19/labor-exploitation-on-door-to-door-sales-crews. [Google Scholar]

26. Rrabbi F. Top open source intelligence (OSINT) tools for dark web [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://osintteam.blog/top-open-source-intelligence-osint-tools-for-dark-web-bb9995bba489. [Google Scholar]

27. Hades [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.maltego.com/transform-hub/atii-hades. [Google Scholar]

28. Neo4j. The leader in graph databases [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 10]. Available from: https://go.neo4j.com/graphs4good-identifying-human-trafficking-and-money-laundering-lp.html?ref=blog. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools