Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework in Courts of Law (DELM-C): A Case of Zanzibar High Courts

1 Department of Computer Engineering and Informatics, Busitema University, Tororo, 236, Uganda

2 Department of Marketing and Management, Makerere University Business School, Kampala, 1337, Uganda

* Corresponding Author: Gilbert Gilibrays Ocen. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 359-375. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.066979

Received 22 April 2025; Accepted 27 August 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

The growing reliance on digital evidence in judicial proceedings has heightened the need for structured, secure, and legally sound frameworks for its collection, preservation, storage, and presentation. In Zanzibar, however, the integration of digital evidence into the court system remains hindered by the absence of standardized procedures and digital infrastructure, undermining the integrity and admissibility of such evidence. This study addresses these challenges by developing a comprehensive Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework (DELM-C) tailored to the operational and legal context of the Zanzibar High Court. The proposed framework aims to streamline digital evidence handling, enhance forensic readiness, and ensure compliance with admissibility standards. Using a quantitative research design, the study engaged 50 purposively selected legal and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) professionals, including judges, lawyers, and forensic experts, through structured surveys. Descriptive statistics and inferential analyses, including regression and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), were used to assess the relationships between variables impacting digital evidence management. The findings revealed mixed but insightful outcomes, indicating both significant and insignificant relationships across technical, legal, and infrastructural factors. The results underscore the urgent need for legal reform, capacity building, and technological upgrades to support the reliable use of digital evidence in Zanzibar’s judiciary. The framework not only addresses existing gaps but also lays the groundwork for future improvements. Future research should focus on pilot-testing the proposed framework within the Zanzibar High Court and conducting cross-jurisdictional comparisons to evaluate the adaptability and effectiveness of digital forensic tools in judicial environments.Keywords

Zanzibar has a rich legal history, marked by the evolution of its judicial system, which has undergone significant transformations since the 19th century. The island’s integration into the United Republic of Tanzania in 1964 established a dual court system influenced by both traditional and modern legal practices. Today, the governance of digital evidence in Zanzibar is primarily guided by the Evidence Act of 2016, particularly Sections 72 and 73, which formally recognize the admissibility of electronic evidence. However, these provisions remain narrow in scope, relying on outdated technological references such as facsimile transmissions, and thus do not effectively address the increasing complexity and sophistication of digital evidence in the modern era [1].

As digital transformation accelerates, legal systems worldwide are facing heightened demands to modernize evidence governance. This is especially crucial in contexts like Zanzibar, where judicial infrastructure must reconcile local legal traditions with the evolving requirements of international digital jurisprudence. Courts must not only ensure that digital evidence is obtained through proper legal mechanisms such as judicial warrants but must also uphold high standards of authenticity, integrity, and chain of custody to satisfy procedural fairness and admissibility criteria. The emergence of complex data forms such as encrypted communications, metadata, surveillance logs, and artificial intelligence-generated content further complicates the evidentiary landscape. Against this backdrop, Zanzibar’s existing legal and institutional apparatus lacks the technological readiness and legal specificity required to reliably govern digital evidence in judicial proceedings.

The Information Systems Success Theory (IS Success Model), developed by DeLone and McLean, serves as the theoretical foundation for this research. The model evaluates information systems through a multidimensional lens, focusing on system quality, information quality, service quality, user satisfaction, and the net benefits delivered to individuals and institutions. By applying this model to the design and assessment of a digital evidence management system, the present study aims to ensure that both technical performance and legal efficacy are met within the Zanzibar High Courts.

Despite recent legal reforms, substantial gaps persist in the effective management and admissibility of digital evidence in Zanzibar. As highlighted by [2], the current legal regime lacks comprehensive protocols for data authentication, secure preservation, privacy protection, and forensic soundness. These deficiencies contribute to procedural inconsistencies and undermine the reliability of digital evidence in court. Critically, no integrated digital evidence management infrastructure enforces a clear chain of custody, supports the application of encryption or hashing standards, or offers guidance on emerging threats such as deepfakes, hyper-realistic synthetic media generated through machine learning algorithms.

The rise of deepfake technology has introduced a new layer of complexity into the domain of digital forensics. Deepfakes exploit artificial intelligence to fabricate multimedia content that can deceive legal authorities and erode the integrity of evidentiary procedures [3]. According to a study by the International Cyber Forensics and Digital Investigation unit, more than 15,000 cases of synthetic media manipulation were detected globally between 2019 and 2022, representing only a fraction (1%) of total digital content reviewed [3]. This alarming statistic emphasizes the need for courts to implement standardized, AI-enabled forensic investigation mechanisms capable of detecting and validating manipulated media. Frameworks such as the Digital Forensics for the Socio-Cyber World (DF-SCW) offer novel approaches by integrating forensic analysis with social media platforms to identify and mitigate the effects of synthetic media in real time [3].

The absence of such mechanisms within Zanzibar’s judicial system presents a significant vulnerability. Not only does it affect the credibility and admissibility of digital evidence, but it also challenges the judiciary’s role in upholding justice in the digital age. Moreover, with increasing reliance on digital content in both civil and criminal litigation, the need for lifecycle-based governance of digital evidence is more urgent than ever. This includes structured protocols for data acquisition, preservation, analysis, and presentation, all while adhering to internationally recognized data protection norms such as General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

In response to these challenges, this paper proposes a Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework (DELM-C), designed specifically for the Zanzibar High Court system. The DELM-C framework aims to bridge the technological-legal divide by introducing a structured, legally coherent, and forensically sound approach to digital evidence management. By implementing this framework, Zanzibar’s judiciary will be better equipped to respond to the challenges posed by digital transformation, ultimately improving the integrity, admissibility, and evidentiary value of electronic data in court proceedings.

This paper makes significant contributions to digital evidence management in judicial systems, particularly in the context of Zanzibar’s High Courts, in the following distinctive ways.

• First, it introduces the first lifecycle-based digital evidence management framework specifically designed to address the legal, technological, and institutional realities of Zanzibar. The framework provides a structured approach to handling digital evidence across all phases from acquisition and preservation to analysis and court presentation, ensuring forensic soundness and legal admissibility.

• Second, the study bridges the persistent gap between modern digital forensic technologies and Zanzibar’s outdated evidentiary laws by embedding compliance mechanisms such as chain-of-custody protocols, admissibility safeguards, and procedural controls. This alignment ensures a harmonized and legally coherent process for managing electronic evidence within the judicial system.

• Third, the proposed framework integrates key data protection and privacy principles, akin to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) standards, including data minimization, purpose limitation, accountability, and lawful processing. These principles are operationalized throughout the framework to protect fundamental rights while preserving the prosecutorial value of digital evidence.

• Finally, the paper proposes a stakeholder-informed, theory-driven model grounded in the Information Systems Success Theory, which emphasizes system quality, information quality, and user satisfaction. In doing so, it also introduces a legally aligned evaluation mechanism that enables courts to assess the reliability, integrity, and admissibility of digital evidence. This holistic approach ultimately enhances institutional trust, transparency, and the overall effectiveness of the judiciary in the digital age.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature informing the study. Section 3 describes the methodology employed in the development of the Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework (DELM-C). Section 4 presents and interprets the results from the inferential statistical analysis, with emphasis on regression and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) findings, their implications, and the proposed DELM-C framework tailored for the Zanzibar High Courts. Lastly, Section 5 concludes the study by summarizing the key findings, outlining policy and practical implications, and offering directions for future research.

2.1 Technological Frameworks in Evidence Management

The integration of new technology into legal frameworks for evidence handling has become increasingly significant as courts across the world adapt to the realities of the digital era. In Zanzibar, a historical overview reveals a judicial system that is gradually recognizing the importance of digital evidence, as evidenced by the Evidence Act of 2016. This act outlines essential conditions for the admissibility of electronic evidence, including requirements for authenticity, reliability, and integrity [2]. Despite this progress, Zanzibar’s evolving legal system still reflects a pressing need for a modern, technologically integrated framework that supports the preservation, authentication, and presentation of electronic evidence in judicial proceedings.

Globally, the growth of digital evidence use has spurred legal scholars and practitioners to advocate for robust frameworks capable of managing this new form of evidence. For instance, research by [4] underscores the value of standardized processes to enhance the reliability and consistency of digital evidence in court. It further emphasizes that any technological framework must not only conform to prevailing legal standards but also be adaptable to future technological developments.

In common law jurisdictions such as the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK), various models and practices serve as useful benchmarks. The United States follows the Federal Rules of Evidence (notably Rule 902(14)), which allows for the self-authentication of electronic evidence that is accompanied by a digital certificate verifying integrity. Moreover, courts in the US have operationalized digital chain-of-custody models to ensure tamper-proof documentation from the point of collection to presentation [5]. Similarly, the UK has adopted principles laid out in the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) Good Practice Guide for Digital Evidence, which serves as a guideline for ensuring digital evidence is handled in a manner that upholds evidentiary integrity and legal admissibility [6].

These international benchmarks highlight the importance of adopting procedural and technical standards tailored to digital environments. This flexibility is particularly essential in jurisdictions like Zanzibar, where digital transformation is still in early stages, and legal-technical synergies remain underdeveloped. Research affirms that the quality of digital evidence, its method of acquisition, and storage, can significantly influence judicial outcomes. As [7] notes, the use of outdated technologies in Zanzibar’s judicial system continues to impede the effectiveness of evidence management. Therefore, implementing a contemporary and locally responsive framework is crucial to address key challenges such as data corruption, evidence tampering, and attribution ambiguity.

2.2 Admissibility of Digital Evidence

The admissibility of digital evidence is typically contingent upon its ability to satisfy well-established legal standards related to accuracy, authenticity, reliability, and integrity. Within Tanzania, legal instruments such as the Electronic Transactions Act and the Evidence Act stipulate that digital evidence must be unaltered and traceable to a trustworthy source [8]. These requirements demand the adoption of rigorous digital forensic procedures that preserve the evidentiary chain and ensure conformance with judicial expectations. As [9] observes, admissibility is not solely a function of the technological medium but also hinges on the legal and procedural rigor involved in evidence collection, analysis, and documentation.

Jurisdictional comparisons further illustrate how admissibility protocols are evolving globally. In the UK, courts have increasingly recognized digital evidence, provided it is acquired and handled in compliance with procedural guidelines and forensic standards, such as those laid out in the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act (CPIA). In the United States, the Daubert Standard governs the admissibility of expert evidence, including digital forensics, emphasizing reliability and methodological soundness. These practices provide valuable insights for Zanzibar’s judicial reforms, particularly regarding cross-border evidence and digital forensics infrastructure [10–12].

Cybercrime and digital evidence often transcend national borders, thereby complicating traditional notions of legal jurisdiction. As [7] notes, courts in Zanzibar must modernize to accommodate foreign-origin evidence and ensure compatibility with international legal cooperation standards. This need has been stressed in regional legal reform discussions, which call for the alignment of national laws with global technological shifts to ensure procedural fairness and evidentiary admissibility.

A major challenge in Zanzibar, as documented by [13], is the limited availability of qualified digital forensic experts. This shortage undermines both the technical handling and legal admissibility of digital evidence. In response, scholars advocate for investments in forensic capacity-building, including specialized training programs and partnerships with international institutions. Such strategies not only address the current skills gap but also contribute to the long-term strengthening of digital evidence practices within the judiciary.

The increasing adoption of technology across various sectors has necessitated the application of comprehensive theoretical frameworks to guide the modernization of processes, particularly within legal jurisdictions where the management of digital evidence is becoming increasingly critical. For this study, which seeks to develop a robust digital framework for the admissibility and management of electronic evidence in the high court system, the Information Systems Success Model (ISSM), originally proposed by DeLone and McLean (1992) and later updated in 2003, offers a particularly relevant theoretical foundation. This theory claims that the success of an information system in any sector (including the court system) can be assessed through six interrelated factors, such as system quality, information quality, service quality, use, user gratification, and net benefits [14,15].

While alternative frameworks such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) have been extensively employed to explain user acceptance and behavioral intention toward technology adoption, these models primarily focus on individual perceptions such as perceived usefulness, ease of use, performance expectancy, and effort expectancy [16]. In contrast, the ISSM provides a more holistic and system-oriented evaluation, emphasizing not only system usage but also system quality, information quality, service quality, user satisfaction, and the net benefits derived from system implementation [17,18].

This multi-dimensional focus aligns more directly with the objectives of the current study, which is not limited to user acceptance but also addresses the institutional and operational effectiveness of digital evidence systems within judicial settings. Therefore, the ISSM is particularly suitable for evaluating the overall impact and success of digital systems in the high court context, encompassing both technical performance and organizational outcomes. Its emphasis on system-level metrics makes it a stronger theoretical lens for assessing the effectiveness of digital evidence frameworks in complex institutional environments such as the judiciary.

For this study, a case study design was employed. Case study design is exploratory; it helps the researcher of this study to generate hypotheses and formulate research questions for further investigation. Also, it is used to conduct in-depth analysis of specific cases in matters like identifying patterns, trends, and phenomena that may warrant further study through quantitative research methods. In this study, the populations are the users of the court, including lawyers, court staff, judges, legal practitioners, court administrators, law enforcement agencies, ICT experts, and other stakeholders. The sample size is calculated through the Yamane formula.

n = N/(1 + N (e)2)

whereby:

n = sample size.

N = population under study.

e = margin error of 0.05.

n = N/(1 + N (e)2)

n = 57/(1 + 57 (0.05)2)

n = 57/(1 + 57 × 0.0025)

n = 57/(1 + 1.1425)

n = 57/1.1425

n = 50

The resulting sample size of approximately 50 participants, rounded up from 49.87 using Yamane’s formula, is considered sufficient and methodologically sound for this study. The total population of 57 individuals was small and highly specialized, comprising judges, court clerks, IT officers, and legal practitioners directly involved in digital evidence processes. By sampling nearly 88% of the total population, the study ensured strong representativeness, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the findings. The approach aligns with best practices for studies involving small, defined populations where comprehensive input is both feasible and valuable.

Moreover, the sample was purposively selected to include key stakeholders with firsthand knowledge of the digital evidence lifecycle, thereby increasing the relevance and depth of the data. This is particularly appropriate given the study’s objective to develop a contextualized Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework (DELM-C) for Zanzibar High Courts, where the focus is on rich, focused insights rather than broad generalizations [19]. Logistical practicality also supported the choice, as the relatively small size of the judicial environment allowed for nearly full population coverage without compromising methodological rigor.

The study used primary data through a data collection tool known as a questionnaire. Under this method, the researcher used closed-ended questions that were unambiguous. Closed-ended questions gave respondents room to tick the most appropriate answer for each question. Questionnaires were given to the respondents. The study handed over the questionnaires to select respondents which including court staff and lawyers.

Having collected primary data, this part describes several tools employed to analyze the collected data. The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) was used to analyze the collected primary data. The collected primary data through a questionnaire was analyzed through descriptive statistics and inferential statistics through regression. By descriptive statistics, a measure of central tendency, including frequencies (F), cumulative frequencies, valid percentages, and percentages (%), was used.

4 Results Analysis and Discussion

This section presents and interprets the findings from the inferential analysis, particularly focusing on the regression and ANOVA outcomes, and their implications for the proposed Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework in Courts of Law (DELM-C) for Zanzibar High Courts.

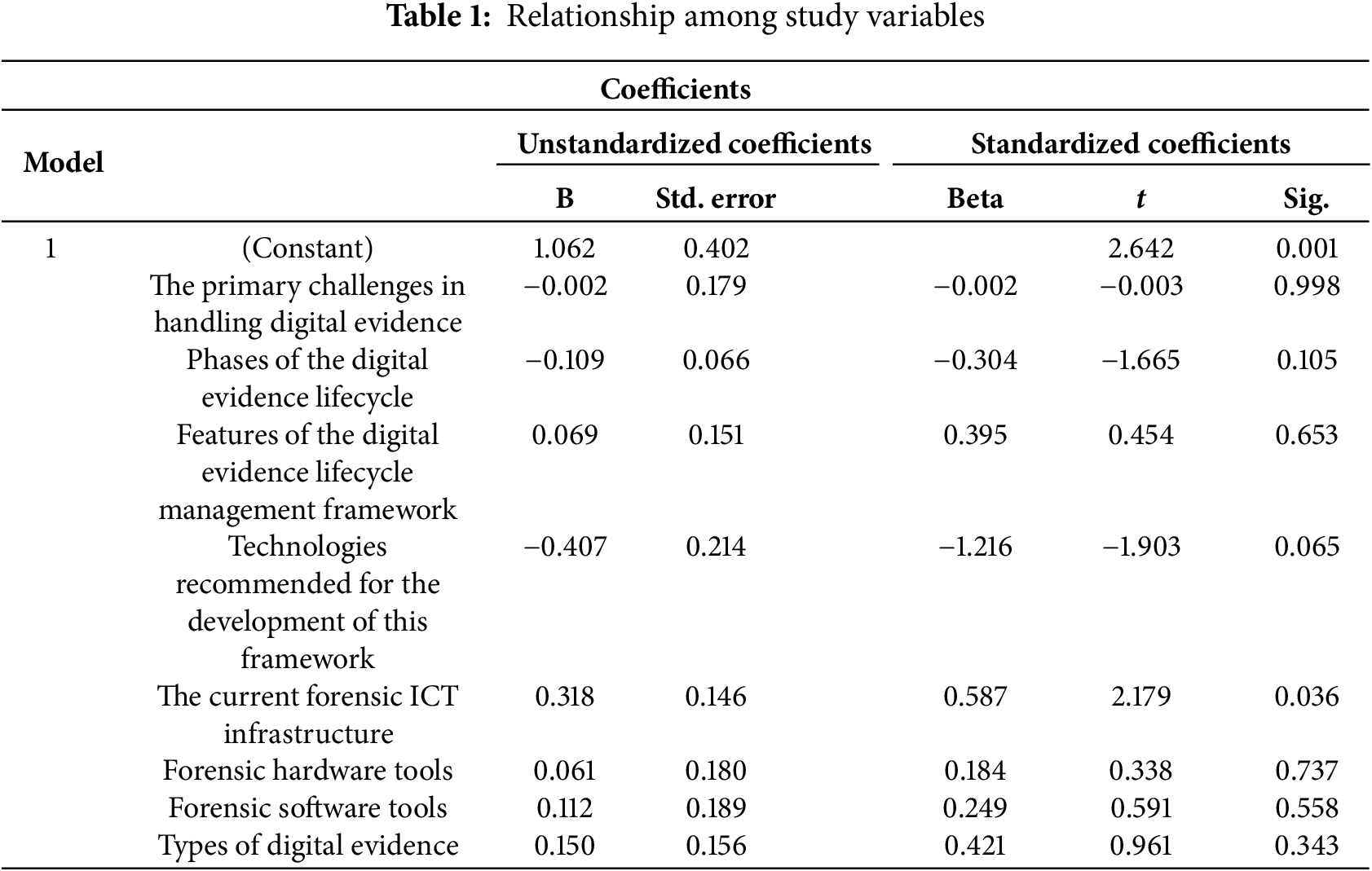

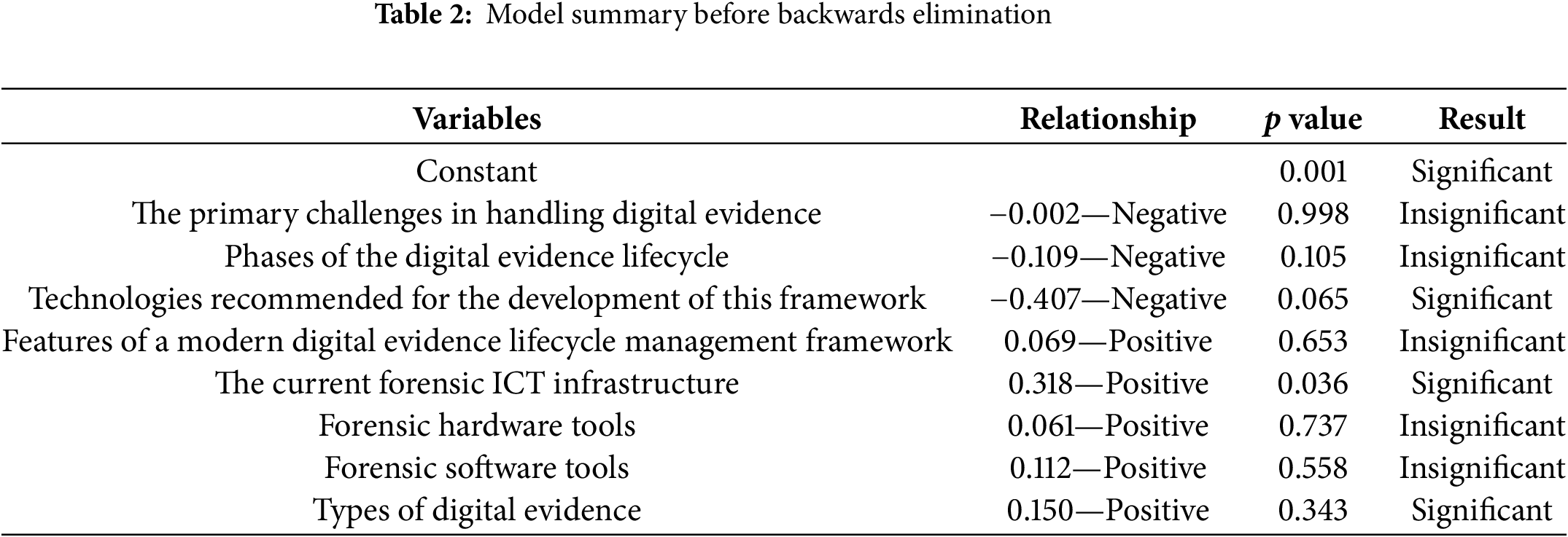

As shown in Table 1, the regression analysis examined the relationships among various independent variables and their influence on the proposed DELM-C framework. The variables that showed a positive and statistically significant relationship included the current forensic Information and Communication Technology (ICT) infrastructure (β = 0.318, p = 0.036), suggesting that the existing technological environment in the courts plays a crucial role in supporting the effective management of digital evidence. This underscores the practical need to strengthen ICT infrastructure in the judiciary to enhance digital forensic capabilities. Conversely, some variables exhibited positive but statistically insignificant associations such as features of the digital evidence lifecycle management framework (β = 0.069, p = 0.653), forensic hardware tools (β = 0.061, p = 0.737), forensic software tools (β = 0.112, p = 0.558), and types of digital evidence (β = 0.150, p = 0.343). While these factors are conceptually relevant, their statistical insignificance suggests a weaker practical influence on DELM-C implementation in the Zanzibar High Court context, possibly due to gaps in deployment, user capacity, or policy enforcement.

On the other hand, Table 2 below reveals that, three variables demonstrated negative relationships: primary challenges in handling digital evidence (β = −0.002, p = 0.998), phases of the digital evidence lifecycle (β = −0.109, p = 0.105), and technologies recommended for the framework (β = −0.407, p = 0.065). Although technologies recommended for the framework approached significance (p = 0.065), the negative relationship might imply implementation challenges such as incompatibility with local court systems, lack of training, or poor integration with existing workflows. The negligible effect of challenges (β = −0.002) and lifecycle phases (β = −0.109) suggests that while these are theoretically critical, their practical influence is likely being undermined by systemic or operational inefficiencies. Overall, these results highlight that, although several variables are considered in the development of the DELM-C framework, only a few exert a measurable impact under current conditions in Zanzibar’s judicial system.

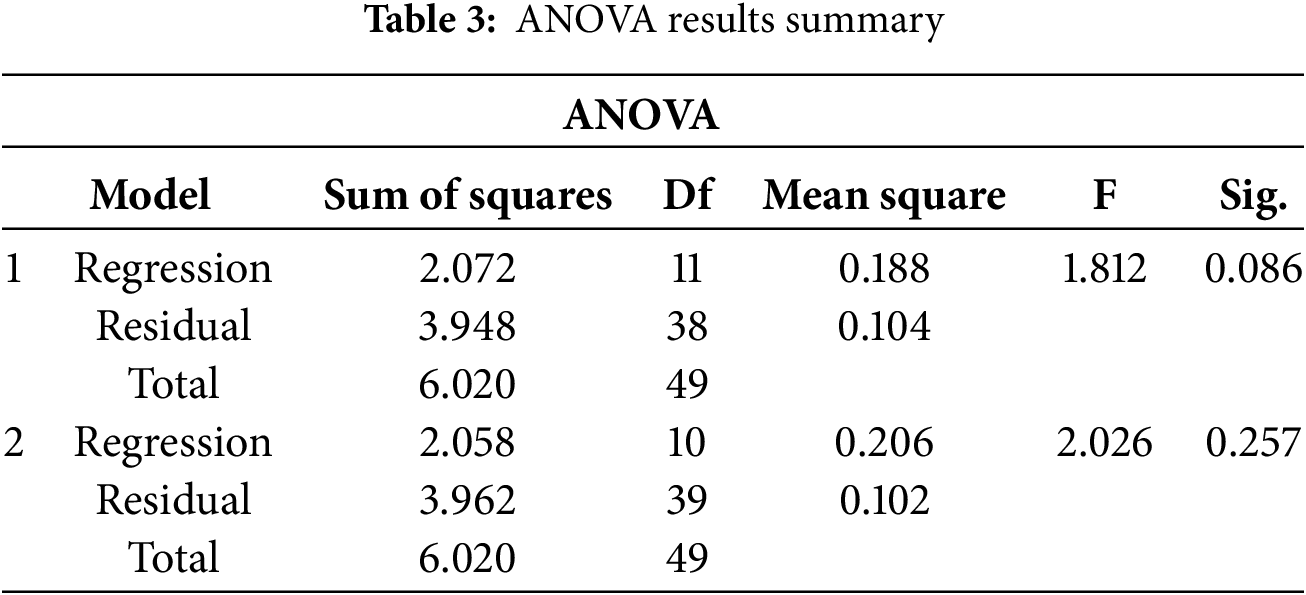

The ANOVA analysis in Table 3 provides additional insights into the model’s explanatory power. The first ANOVA model yielded an F-statistic of 1.812 with a p-value of 0.086, indicating marginal significance. This result suggests that the collective influence of all independent variables in predicting the dependent variable is relatively weak, though not entirely dismissible. The second model, with an F-statistic of 2.026 and a p-value of 0.257, confirms the lack of a statistically significant joint effect among the selected predictors. From a practical standpoint, this reinforces the notion that while certain components, such as ICT infrastructure, show strong individual effects, the framework as currently constructed may not achieve its full potential without deeper integration and alignment among the lifecycle phases, tools, and institutional capacities.

Critically, the presence of mixed significance both statistically and directionally has important practical implications. It implies that while the framework’s conceptual components are valid, their real-world effectiveness depends on contextual readiness, capacity building, and tailored implementation. For example, investing in ICT infrastructure without complementary improvements in forensic tools or training may yield limited impact. Similarly, the negative association with recommended technologies may call for a reassessment of the suitability, localization, or rollout strategy of such tools in Zanzibar’s legal context. Therefore, the DELM-C framework must not only be technically sound but also contextually adaptable, focusing on synergistic integration of the most influential elements while addressing the weaker or negatively contributing factors through targeted policy or procedural interventions.

In conclusion, the inferential results indicate a framework with strong theoretical grounding but partial practical readiness. The Zanzibar High Courts can use these findings to prioritize infrastructure development and evaluate the contextual fit of advanced forensic technologies, while gradually strengthening other components, such as procedural phases and capacity to handle digital evidence effectively.

4.1 Requirements for Developing New Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework

The analysis of findings on the Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework (DELM-C) seeks to determine the requirements for developing a structured framework for the collection, storage, preservation, and presentation of digital evidence in court practices and performance. Understanding the opinions of respondents regarding the necessity of such a framework is crucial in assessing its potential impact on the efficiency of judicial proceedings in the Zanzibar High Courts.

The findings indicate that a significant majority of respondents believe in the necessity of a dedicated digital evidence lifecycle management framework. Specifically, 15 respondents strongly agreed, and 24 agreed that implementing such a system would enhance court proceedings. This combined total of 39 out of 50 respondents, or 78%, demonstrates a substantial level of support for the initiative. Their positive response suggests that a structured approach to managing digital evidence is widely perceived as an essential improvement for the judicial system.

A smaller proportion of the respondents remained neutral on the matter, with three individuals neither supporting nor opposing the framework. This neutrality may suggest a lack of familiarity with the concept or uncertainty about its implementation. It may also indicate a need for further education and awareness campaigns to provide a clearer understanding of how such a system could improve court processes.

On the other hand, some respondents expressed resistance to the framework. Six individuals disagreed, while two strongly disagreed, making up a total of eight respondents or 16% of the surveyed group. Their opposition could stem from concerns regarding the costs, technical challenges, or the practical feasibility of integrating such a system into the current judicial structure. This minority opposition suggests that further investigation is needed to identify and address the specific challenges perceived by these individuals.

The implications of these findings underscore the need to develop and implement a digital evidence lifecycle management framework for the Zanzibar High Courts. The strong agreement among respondents highlights a growing recognition of the importance of structured digital evidence handling in modern judicial processes. However, the presence of neutral and opposing views suggests that efforts must be made to clarify misconceptions, address concerns, and ensure that stakeholders are well-informed about the framework’s benefits.

To facilitate the successful adoption of the framework, further research should be conducted to explore and mitigate the concerns raised by those who are hesitant or opposed to its implementation. Additionally, training and sensitization programs should be introduced to ensure that judicial officers, law enforcement agencies, and other stakeholders fully understand and appreciate the value of an organized digital evidence management system. By addressing these concerns proactively, the Zanzibar High Courts can ensure a smoother transition toward an improved and technologically advanced judicial process that enhances transparency, efficiency, and accuracy in the handling of digital evidence.

4.2 Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework in the Zanzibar High Court

The formulation of a Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework (DELM-C) for the Zanzibar High Court is essential for enhancing judicial efficiency, evidentiary credibility, and legal compliance. As digital technologies increasingly permeate judicial proceedings, courts must adapt by adopting systems that are technologically robust and legally grounded. The proposed framework aligns with both global best practices (such as those guided by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)) and Zanzibar’s domestic legal framework on evidence, privacy, and procedural fairness. Its foundation is informed by the Information System Success Theory, emphasizing system quality, information quality, and user satisfaction as critical success indicators.

The framework is designed to operationalize legal admissibility, protect privacy, and ensure data protection throughout the digital evidence lifecycle. It addresses technical and legal requirements across all stages of collection, preservation, analysis, and presentation through structured, transparent, and auditable processes. These include the use of forensic sound tools, role-based access controls, and chain-of-custody mechanisms. Importantly, the framework embeds GDPR-type principles such as data minimization, purpose limitation, accountability, and data subject rights. All data processing activities are subject to lawful authority (e.g., search warrants or court orders), and safeguards are applied to prevent over-collection or misuse of personal information. Inclusion of legal professionals and judicial stakeholders during the design and implementation phases ensures that the framework remains compliant with evidentiary thresholds and judicial expectations for integrity and fairness.

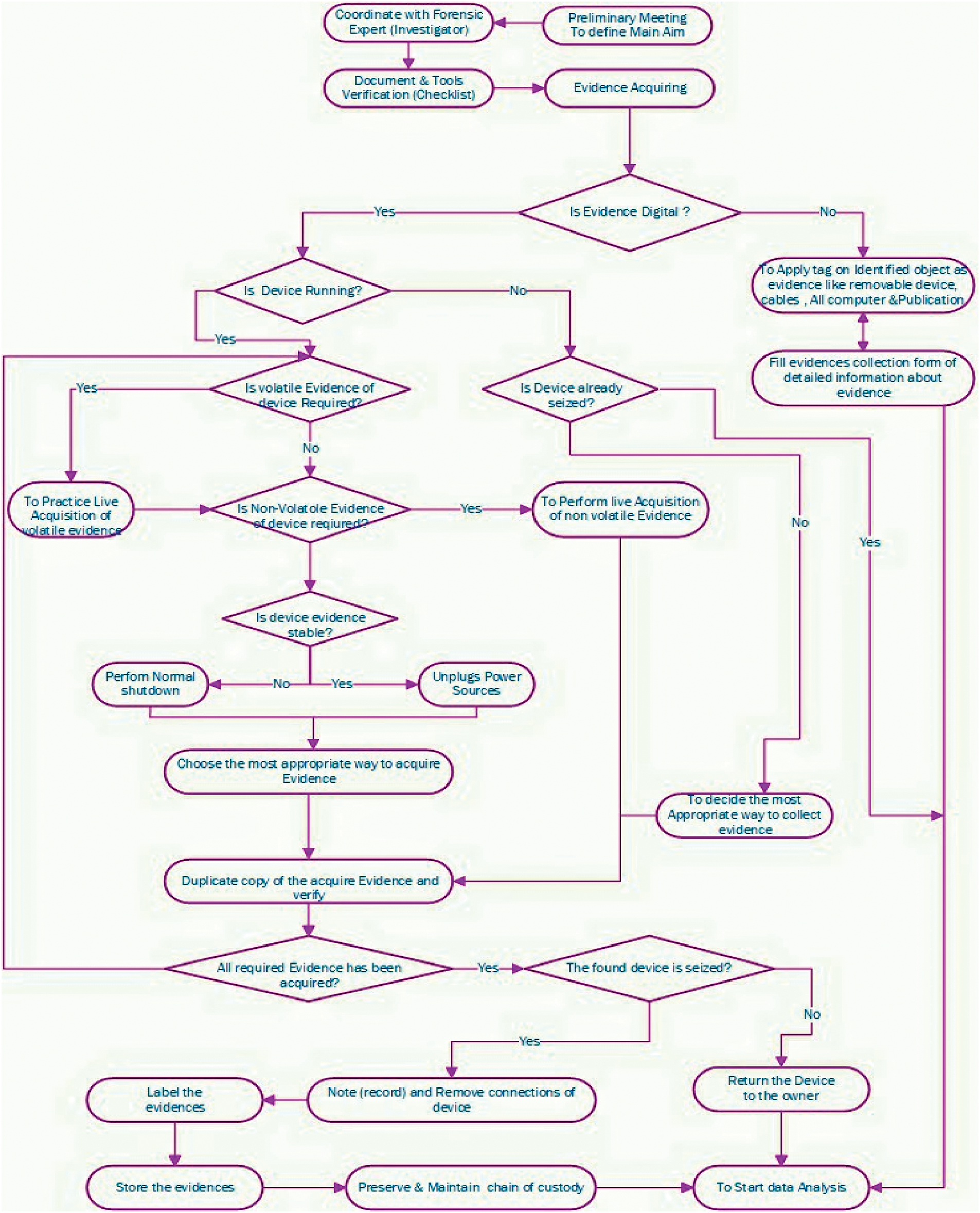

Moreover, a built-in monitoring and evaluation component allows for periodic assessment of the framework’s impact on the accuracy, reliability, and admissibility of digital evidence. By combining empirical evidence, technological innovation, and legal safeguards, the DELM-C aims to transform digital evidence handling in Zanzibar’s judicial system into a secure, trustworthy, and legally coherent process. Fig. 1 below presents the core phases of the Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework applied in the Zanzibar High Court.

Figure 1: The digital evidence lifecycle management framework in the Zanzibar High Court system (DELM-C). Source: constructed by author, (2025)

The subsequent section provides an in-depth exposition of the Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework in the context of its application within the Zanzibar High Court system.

Initial Preparation Phase

This phase begins with planning and legal consultation between forensic experts and investigators to ensure that evidence acquisition aligns with applicable laws. Legal authorization (e.g., search and seizure orders) is verified, and tools are tested to prevent procedural errors. A formal checklist, aligned with evidentiary and privacy standards, ensures readiness while minimizing legal risk and protecting data subjects’ rights.

Evidence-Acquiring Decision Phase

This stage involves classifying evidence as digital or non-digital. Non-digital evidence is physically tagged and documented. For digital evidence, investigators must assess whether legal access is granted and whether data access complies with principles such as necessity, proportionality, and minimal intrusiveness. An evidence collection form records source, type, and scope, promoting transparency and eventual admissibility.

Digital Evidence Collection Phase

For devices already seized, investigators perform live acquisition of volatile or non-volatile data using court-approved tools. If devices are running, volatile memory is collected only if legally justified. Throughout, data minimization principles are upheld, and unnecessary personal information is excluded. Forensic techniques used in this phase are selected based on their ability to preserve data authenticity and legal defensibility.

Handling Non-Volatile Evidence Phase

The stability of devices is assessed to avoid data corruption. Powering down is performed systematically, and acquisition methods are forensically sound. Duplication and hashing of data follow strict protocols to maintain evidentiary integrity. This safeguards the admissibility of digital evidence under evidentiary rules that require reliability, continuity, and lack of alteration.

Evidence Verification and Handling Phase

All collected evidence undergoes verification to ensure completeness. Labeling includes case details, investigator ID, and acquisition time. The chain of custody is documented and maintained in line with legal expectations to prevent evidence tampering or disputes about authenticity. Storage is handled in secure environments where access is strictly regulated and audit trails are maintained.

Final Decision: Device Handling and Analysis Phase

Devices not critical for ongoing investigations are returned to their owners. Seized devices are handled with due legal process. The forensic analysis phase is conducted within secure workspaces by authorized personnel. Privacy-preserving analysis techniques are employed, and results are compiled into tamper-proof reports, maintaining the confidentiality and admissibility of findings.

4.2.1 Legal and Security Safeguards across the Lifecycle

Each phase of the DELM-C is underpinned by clear legal and security safeguards that ensure digital evidence is not only technically valid but also legally defensible. The framework applies the following data protection and evidentiary controls:

Collection Phase: Evidence is collected under lawful authority, with protocols in place to avoid excessive or irrelevant data collection. This aligns with the purpose limitation and necessity principles.

Preservation Phase: Collected data is stored in tamper-proof repositories. Legal and technical controls such as encryption, access controls, and hashing safeguard integrity and support the authenticity requirement in court.

Training and Capacity Building Phase: Personnel involved in evidence management are trained in legal and data protection responsibilities. They are familiar with chain-of-custody protocols, GDPR-type principles, and relevant statutory obligations.

Storage Phase: Evidence is held in secure facilities (digital or physical), with protection against unauthorized access, data breaches, or environmental hazards. Storage systems employ encryption, backup protocols, and disaster recovery plans.

Analysis Phase: Data is processed in controlled environments using approved forensic tools. Access is role-based, and logs are maintained for accountability. Sensitive data is anonymized or redacted where appropriate to uphold privacy.

Presentation Phase: Findings are compiled in structured formats, ensuring accuracy, completeness, and resistance to tampering. Secure transmission and digital signing mechanisms enhance evidentiary credibility during court proceedings.

4.2.2 Technical Specification of the DELM-C Framework for Implementation

To strengthen the practical applicability and implementation credibility of the proposed DELM-C framework, it is essential to move beyond conceptual and graphical representation and technically specify its core components. The following section outlines the key security, integrity, and compliance elements such as data hashing, chain of custody tools, encryption standards, and audit mechanisms that are critical for ensuring the framework’s effectiveness, legal admissibility, and alignment with international best standards such as ISO/IEC 27037 and 27043, making the DELM-C framework technically viable and legally defensible in the Zanzibar High Court system.

Data Hashing and Integrity Verification

Each piece of digital evidence must be subjected to cryptographic hashing algorithms (e.g., SHA-256) at the point of acquisition. Hash values serve as digital fingerprints and are used to verify that the evidence remains unaltered throughout its lifecycle. Upon every access, transfer, or duplication of evidence, the hash value must be recalculated and matched to the original to confirm integrity.

Chain of Custody Management Tools

To maintain admissibility in court, a chain of custody must be preserved. This is facilitated by digital tools that log:

• Date and time stamps of each action

• Identity and role of individuals accessing the evidence

• Purpose of each access or modification

A centralized Chain of Custody Management System (CCMS) should be implemented with tamper-evident logs, audit trails, and blockchain-based record-keeping to prevent any unauthorized modification.

Encryption Standards for Secure Storage and Transfer

All digital evidence must be stored and transmitted using end-to-end encryption based on international standards such as AES-256. Evidence stored in digital repositories should be encrypted at rest, with access only granted via role-based permissions. Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)/Transport Layer Security (TLS) should be used for transmission between forensic labs and courts.

Secure Digital Evidence Repository

A Forensic Evidence Management System (FEMS) should serve as the centralized repository. Features should include:

• Redundant, encrypted cloud and local storage

• Controlled access based on clearance levels

• Immutable logs of evidence movement and access

• Automatic hash verification during upload/download

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) and Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA)

To prevent unauthorized access, the system must implement RBAC by assigning permissions based on user roles (such as judge, forensic expert, prosecutor). Additionally, MFA (e.g., password + biometric verification) should be mandatory for login to the system, particularly for users with administrative rights.

Integrated Audit and Monitoring Mechanisms

A real-time audit dashboard must be incorporated to: Monitor access patterns and generate alerts for anomalies, log all user activities related to evidence handling, and provide compliance reports for judicial and regulatory bodies.

Evidence Presentation and Reporting Tools

For courtroom use, the framework should include evidence presentation modules that allow:

• Visualization of digital evidence while maintaining its original metadata

• Generation of court-admissible reports that include hash values, access history, and handling procedures

• Secure digital signing of final reports using PKI (Public Key Infrastructure)

4.2.3 Framework Design and Evaluation

Framework Design

The development of the Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework (DELM-C) for the Zanzibar High Courts was guided by a structured system design approach. The structured system design approach is a method that combines system engineering, modeling, and analysis to create efficient systems. Key components include modeling techniques like function hierarchy charts and data flow diagrams for better communication, a modular design for easier upgrades, optimization methods to improve performance, and interdisciplinary collaboration to bring in diverse perspectives for better solutions [20]. The structured system design approach was informed by both the empirical gaps identified in existing frameworks and the contextual needs observed through field data collection. The framework was iteratively developed through three improvement cycles, each incorporating feedback from domain experts, specifically, professionals actively engaged in digital evidence investigations within the jurisdiction of Zanzibar.

In addition, the initial design process did not occur in isolation. It was implemented and validated within a testbed environment consisting of specific hardware and software configurations. The test environment included an Intel Core i7 (12th Gen) processor with 16 GB RAM, a 512 GB SSD, and Windows 10 Pro (64-bit) operating system and Microsoft Visio software. This environment supported seamless execution of simulation tasks related to the digital evidence lifecycle.

These expert consultations and experimental configurations were instrumental in ensuring the contextual relevance, technical feasibility, and legal applicability of the framework. Their inputs informed critical structural refinements and supported the alignment of the framework with both legal standards and operational realities specific to the Zanzibar judicial context. The iterative design process ensured that the resulting framework was both comprehensive and adaptable to the specific evidentiary processes followed in the Zanzibar judicial system.

Framework Testing and Evaluation

To assess the practical viability and effectiveness of the proposed DELM-C framework, a simulation-based testing and evaluation process was conducted using two widely accepted digital forensics tools: Autopsy (version 4.21.0) and FTK Imager (version 4.7.1.2). These tools were selected due to their global recognition in forensic investigations, compatibility with legal evidentiary standards, open-source availability, and suitability for academic and operational testing environments [21,22].

The evaluation process focused on simulating key lifecycle activities such as evidence acquisition, preservation, analysis, and presentation within a controlled testing environment. These simulations helped verify whether the framework could effectively support the procedural, legal, and technical requirements expected in real-world court settings.

In addition, a set of standardized evaluation metrics was applied during the testing and simulation processes. These metrics, widely adopted in the domain of digital forensics and information systems evaluation, were selected to reflect key performance aspects such as accuracy, integrity, reliability, and usability of the digital evidence handling process. Each metric provides insight into a specific dimension of framework effectiveness [23–25]. The following formulas were used for metric calculation:

Accuracy (%) = (Number of correctly processed evidence items/Total evidence items) × 100

Integrity (%) = ((Total number of files with unaltered hashes/Total number of files) × 100)

Reliability (%) = (Number of consistent results across tests/Total number of tests) × 100

Usability Score = (Sum of user ratings on usability criteria/Number of criteria) × 5 (scaled to 100%)

These metrics collectively provided a robust, quantifiable foundation for evaluating the efficacy and practical value of the DELM-C framework in supporting secure, admissible, and efficient digital evidence management in judicial settings.

The findings of this study affirm the urgent necessity for a structured, technologically advanced Digital Evidence Lifecycle Management Framework (DELM-C) within the Zanzibar High Court. The court’s continued reliance on manual and paper-based systems is increasingly inadequate in managing the growing complexity, volume, and sensitivity of digital evidence that now plays a critical role in judicial proceedings. The research has revealed notable deficiencies in digital forensic capacity, ranging from legal awareness and technical expertise to institutional infrastructure and procedural standardization. These gaps directly impact the reliability, authenticity, and legal admissibility of digital evidence, ultimately affecting the efficiency, fairness, and integrity of judicial decision-making.

To support the successful adoption of the DELM-C framework, this study recommends a multifaceted strategy. First, there is a pressing need for institutional and legislative reform to update existing legal instruments and align them with contemporary technological realities. This includes enacting or amending laws to incorporate detailed standards on evidence admissibility, chain of custody, forensic soundness, and compliance with international best practices such as ISO/IEC 27037 and ISO/IEC 27043. Such reforms will provide courts and legal practitioners with authoritative guidance on managing digital evidence in a forensically sound and legally defensible manner.

In terms of future research, several promising directions have emerged from this study. One potential avenue involves conducting pilot implementations of the DELM-C framework in selected divisions of the Zanzibar High Court. These pilots would evaluate operational feasibility, end-user adoption, and the framework’s impact on the evidentiary process, ultimately providing practical feedback for refining the system. Additionally, comparative cross-jurisdictional analyses involving regions with mature digital forensic infrastructures could yield valuable insights into scalable best practices and facilitate regional policy harmonization.

Future work should also explore the integration of emerging technologies to further enhance the framework’s analytical and predictive capabilities. Notably, incorporating multimodal learning techniques, Large Language Models (LLMs), and the Internet of Things (IoT) could open new frontiers in proactive digital evidence collection, contextual analysis, and risk detection. For instance, recent advancements in LLM-based architectures, such as LLM-AE-MP, have demonstrated significant promise in detecting sophisticated web attacks and could potentially be adapted for use in judicial digital forensics [26].

In conclusion, the DELM-C framework represents a foundational step toward modernizing the handling of digital evidence in Zanzibar’s judicial system. Through its lifecycle-based approach, grounded in legal, technical, and ethical safeguards, the framework aims to enhance transparency, accountability, and admissibility in court proceedings, thus ensuring justice is both served and seen to be served in an increasingly digital legal landscape.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely appreciate the valuable insights and constructive feedback offered by the colleagues and peers throughout this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Gilbert Gilibrays Ocen; data collection: Idarous Saleh Said; analysis and interpretation of results: Alunyu Andrew Egwar; draft manuscript preparation: Mwase Ali. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Makulilo AB. The admissibility and authentication of digital evidence in Zanzibar under the new Evidence Act. Digit Evid Electron Signature Law Rev. 2018;15:48. doi:10.14296/deeslr.v15i0.4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Abdul-Samad A, Md Siraj M, Hajar Othman S, Hafiz Rahman M, Zaharudin Ahmad Darus M. Comprehensive review on data preservation models and standards in digital forensic. In: 2024 International Conference on Data Science and Its Applications (ICoDSA); 2024 Jul 10–11; Kuta, Indonesia. p. 277–82. doi:10.1109/icodsa62899.2024.10651616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Khan AA, Chen YL, Hajjej F, Ahmed Shaikh A, Yang J, Soon Ku C, et al. Digital forensics for the socio-cyber world (DF-SCWa novel framework for deepfake multimedia investigation on social media platforms. Egypt Inform J. 2024;27:100502. doi:10.1016/j.eij.2024.100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Donoghue J. The rise of digital justice: courtroom technology, public participation and access to justice. Mod Law Rev. 2017;80(6):995–1025. doi:10.1111/1468-2230.12300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Casey E, Brenner SW. Digital evidence and computer crime: forensic science, computers and the Internet. 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

6. ACPO (Association of Chief Police Officers). Good practice guide for digital evidence; 2012 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://athenaforensics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/National-Police-Chiefs-Council-ACPO-Good-Practice-Guide-for-Digital-Evidence-March-2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. Manning C, Kasera S. Guide to Tanzania legal system and legal research; 2020 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.nyulawglobal.org/globalex/tanzania1.html. [Google Scholar]

8. Mwakimako H. The historical development of Muslim courts: the Kadhi, Mudir and Liwali courts and the civil procedure code and criminal procedure ordinance, c. 1963. J East Afr Stud. 2011;5(2):329–43. doi:10.1080/17531055.2011.571392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yeboah-Ofori A, Brown AD. Digital forensics investigation jurisprudence: issues of admissibility of digital evidence. J Forensic Leg Investig Sci. 2020;6(1):1–8. doi:10.24966/flis-733x/100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. United States Courts.Federal rules of evidence 2017. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.uscourts.gov/forms-rules/records-rules-committees/superseded-rules/federal-rules-evidence-2017. [Google Scholar]

11. Criminal procedure and investigations act (1996UK. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1996/25/contents. [Google Scholar]

12. Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993). [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/509/579/. [Google Scholar]

13. Deandra FH, Sherly IM. Advancing digital forensic investigations: addressing challenges and enhancing cybercrime solutions. World J Inf Technol. 2025;3(1):10–5. doi:10.61784/wjit3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. DeLone WH, McLean ER. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update. J Manag Inf Syst. 2003;19(4):9–30. doi:10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. DeLone WH, McLean ER. Information systems success: the quest for the dependent variable. Inf Syst Res. 1992;3(1):60–95. doi:10.1287/isre.3.1.60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rejali S, Aghabayk K, Esmaeli S, Shiwakoti N. Comparison of technology acceptance model, theory of planned behavior, and unified theory of acceptance and use of technology to assess a priori acceptance of fully automated vehicles. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract. 2023;168(2):103565. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2022.103565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hidayat MT, Setiawan A. The influence of system quality, information quality, and service quality on the enterprise resource planning (ERP) system towards user satisfaction at PT. alam bukit tigapuluh. Am J Econ Manag Bus. 2024;3(12):430–5. doi:10.58631/ajemb.v3i12.135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Septianita W, Winarno WA, Arif A. Effect system quality, information quality, service quality of rail ticketing system (RTS) to user satisfaction. E-J Ekon Bisnis Dan Akunt. 2014;1(1):53–6. doi:10.38043/jmb.v19i1.4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Campbell S, Greenwood M, Prior S, Shearer T, Walkem K, Young S, et al. Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(8):652–61. doi:10.1177/1744987120927206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Müller-Merbach H. The structured systems approach for the design of optimisation and simulation models. In: Computer-Based Management of Complex Systems: Proceedings of the 1989 International Conference of the System Dynamics Society; 1989 Jul 10–14; Stuttgart, Germany. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1989. p. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

21. Easttom C, Butler W, Phelan J, Sai Bhagavatula R, Steuber S, Rodriguez K, et al. Creating forensic images using OSForensics, FTK imager, and autopsy. In: Windows forensics. Berkeley, CA, USA: Apress; 2024. p. 65–119. doi:10.1007/979-8-8688-0193-8_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dowling A. Digital forensics: a demonstration of the effectiveness of the sleuth kit and autopsy forensic browser; 2006 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/378. [Google Scholar]

23. Du X, Le-Khac NA, Scanlon M. Evaluation of digital forensic process models with respect to digital forensics as a service. arXiv:1708.01730. 2017. [Google Scholar]

24. Sajidha SA, Kumar R, Puri L, Gaur M, Kumar MS, Tyagi AK, et al. Robust and secure evidence management in digital forensics investigations using blockchain technology. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2023. p. 214–43. doi:10.4018/978-1-6684-8938-3.ch010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Greco C, Ianni M, Seminara G, Guzzo A, Fortino G. A forensic framework for screen capture validation in legal contexts. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR); 2024 Sep 2–4; London, UK. p. 127–32. doi:10.1109/csr61664.2024.10679466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yang J, Wu Y, Yuan Y, Xue H, Bourouis S, Abdel-Salam M, et al. LLM-AE-MP: web attack detection using a large language model with autoencoder and multilayer perceptron. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;274(4):126982. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools