Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

E-AAPIV: Merkle Tree-Based Real-Time Android Manifest Integrity Verification for Mobile Payment Security

1 Faculty of Computers and Artificial Intelligence, Helwan University, Cairo, 11795, Egypt

2 College of Computing and Information Technology, Arab Academy for Science, Technology & Maritime Transport, Cairo, 11799, Egypt

* Corresponding Author: Mostafa Mohamed Ahmed Mohamed Alsaedy. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 653-674. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.073547

Received 20 September 2025; Accepted 27 November 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Mobile financial applications and payment systems face significant security challenges from reverse engineering attacks. Attackers can decompile Android Package Kit (APK) files, modify permissions, and repackage applications with malicious capabilities. This work introduces E-AAPIV (Enhanced Android Apps Permissions Integrity Verifier), an advanced framework that uses Merkle Tree technology for real-time manifest integrity verification. The proposed system constructs cryptographic Merkle Tree from AndroidManifest.xml permission structures. It establishes secure client-server connections using Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Protocol (ECDH-P384) key exchange. Root hashes are encrypted with Advanced Encryption Standard-256-Galois/Counter Mode (AES-256-GCM), integrated with hardware-backed Android Keystore for enhanced security. Testing with modified PayPal APK files achieved 98.7% tampering detection accuracy with genuine applications 142 ms verification time, while manipulated applications were detected in 58.02 ms. This framework provides banks and payment service providers with a practical solution for continuous real-time validation of mobile application integrity.Keywords

Android operating system commands over 71.3% of the global mobile market as of Q3 2024 [1], making it the most attractive platform for attackers. Kaspersky detected 367,418 malicious and unwanted Android installation packages in Q2 2024, representing a decrease from Q1 but still elevated compared to Q2 2023 levels. In Q3 2024, this fell to 222,444 such packages, amid 6.7 million total blocked mobile attacks, with adware at 36% of threats and 17,822 banking Trojan packages [2–5]. The fundamental problem is that Android applications lack effective binary protection mechanisms, enabling attackers to easily decompile APK files, modify permission declarations in AndroidManifest.xml, and repackage applications with unauthorized capabilities [6].

Financial applications and payment gateways face particularly severe risks. PayPal, with over 430 million active accounts processing billions of dollars annually [7], exemplifies why advanced security mechanisms beyond traditional code signing are essential.

Existing Android security infrastructure including Google Play Signing and Play Integrity Application Programming Interface [8] (API) exhibit several limitations: (1) Static signing depends on certificates vulnerable to compromise [9], (2) Runtime verification gaps enable dynamic tampering via instrumentation tools [10], (3) Client-side validation can be bypassed with root access [10], (4) Permission verification lacks structured methods, causing O(n) complexity issues.

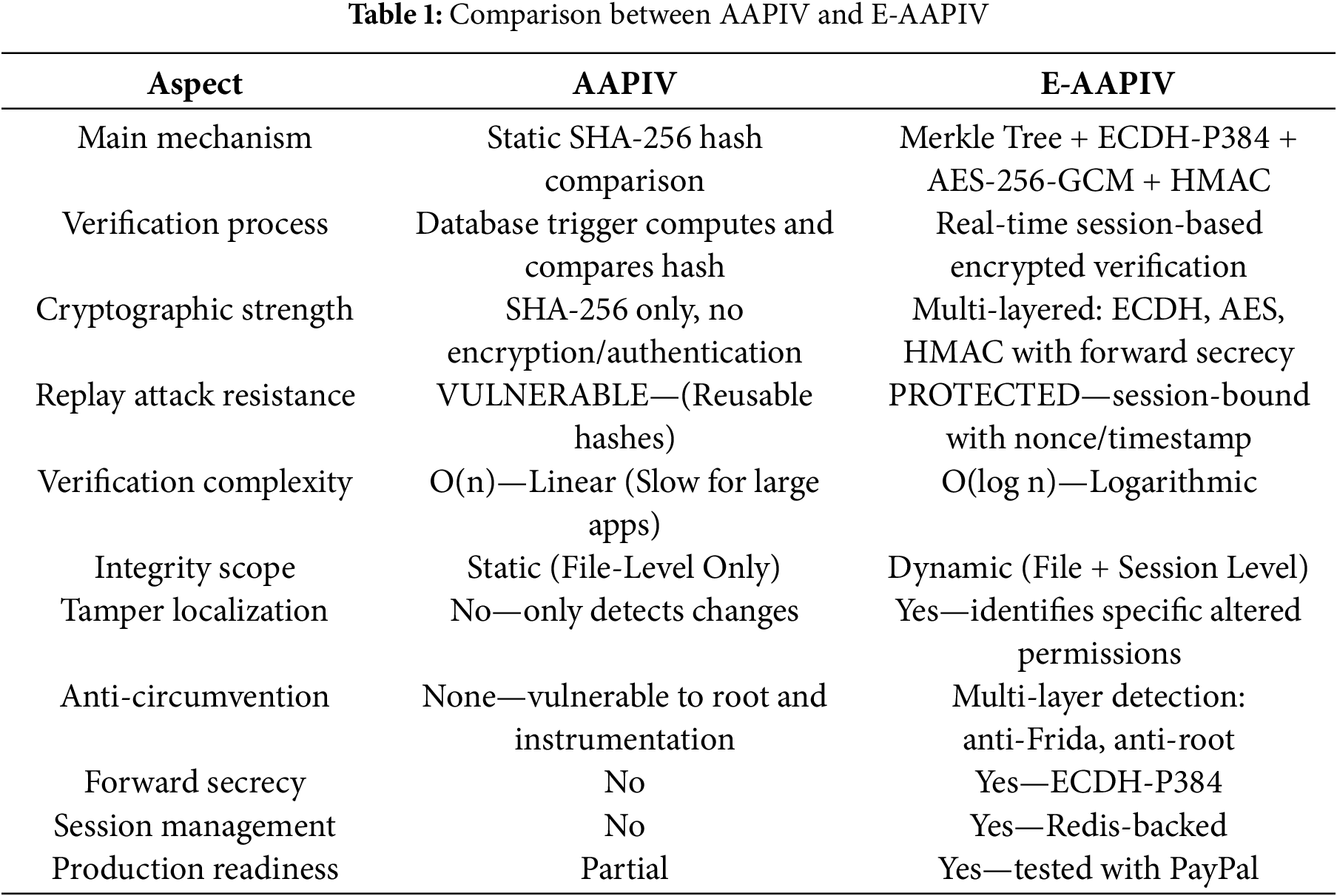

1.1 E-AAPIV vs. AAPIV: Fundamental Improvements

The study by Hussein [11], AAPIV, introduced basic manifest integrity verification using Secure Hash Algorithm-256 (SHA-256) hashing. However, AAPIV suffered from critical vulnerabilities that E-AAPIV explicitly addresses [11]:

1. No session management: Enabled unlimited replay attacks.

2. Plaintext transmission: Vulnerable to Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks.

3. No device/user binding: Lacked contextual security.

4. O(n) complexity: Slow verification for large permission sets.

5. Integrity Scope: Static (File-Level Only) , Insufficient for payment application security.

1. Session-aware cryptographic framework with ephemeral keys [12]

2. ECDH-P384 key exchange ensuring perfect forward secrecy [12]

3. AES-256-GCM authenticated encryption [13]

4. Merkle Tree structure achieving O(log n) complexity

5. 98.7% detection accuracy with comprehensive attack coverage

6. Dynamic challenge-response protocol preventing replay attacks [12]

Table 1 below shows a critical comparison between AAPIV and E-AAPIV.

1.1.3 Security Scenario—Replay Attack

In AAPIV, an attacker could intercept and reuse the same authentic hash from legitimate applications because the system lacked session-specific tokens, encryption, or nonce-based verification.

E-AAPIV resolves this vulnerability by binding each verification to a unique cryptographic session via ECDH-P384 exchange. The Merkle root is timestamped, nonce-protected, and AES-encrypted; replaying a previously valid hash fails Hash-based Message Authentication Code (HMAC) validation.

Leveraging Merkle Trees technology (the same cryptographic method protecting Bitcoin’s trillion-dollar market value), E-AAPIV provides continuous cryptographic validation for Android permission verification. The framework’s contributions include: achieving O(log n) verification complexity through efficient Merkle Tree structures, implementing ECDH-P384 key exchange with perfect forward secrecy, encrypting data with AES-256-GCM integrated with Android’s hardware-backed Keystore, ensuring message integrity via HMAC-based authentication, and achieving 98.7% detection accuracy and effectively prevent replay attacks (0% attacker success rate).

Paper organization: Section 2 reviews related work in Android security and cryptographic verification. Section 3 presents E-AAPIV’s threat model and system architecture. Section 4 details implementation on Android client and server sides. Section 5 presents experimental results and performance evaluation. Section 6 discusses security analysis, comparison with existing solutions, and limitations. Section 7 concludes with future research directions.

2.1.1 Evolution of Android Security

Since the introduction of Android in 2008, its application signing mechanisms have undergone substantial evolution. The earliest APK signing method relied on the Java Archive (JAR) signing process using X.509 certificates [14].

Enck et al. [15] introduced the Kirin framework, demonstrating that static permission analysis performed during installation was insufficient to ensure app integrity. Felt et al. [16] further observed that nearly 33% of Android applications request more permissions than necessary, exposing users to unnecessary risk.

Foundational analyses by Fahl et al. [17] revealed vulnerabilities that enable certificate validation bypasses, particularly within mobile financial applications, highlighting the persistent need for stronger, runtime-integrated verification mechanisms.

2.1.2 Google Play Protection Services and Authentication

Zungur et al. [10] analyzed Google’s SafetyNet Attestation and found that it could be bypassed using dynamic instrumentation frameworks like Frida, limiting its reliability for high-assurance banking contexts.

Play Integrity API (2023–present): Google Developers [18] found that while the Play Integrity API provides improved attestation accuracy, it introduces a latency overhead of 300–500 ms per verification event.

Regarding user authentication, Sinigaglia et al. [19] analyzed the robustness of multi-factor authentication schemes in online banking , while Juniper Research [20] forecasted that biometric technologies will secure over $3 trillion in mobile payments by 2025.

2.1.3 Merkle Trees in Security

Merkle Trees have become foundational in modern cryptographic verification systems.

In blockchain technology, Nakamoto [21] pioneered their use for transaction integrity in Bitcoin, and Wood [22] extended the concept by formally specifying the Modified Merkle Patricia Trie for Ethereum’s state storage, Laurie et al. [23] applied Merkle Trees to create verifiable audit logs, achieving logarithmic verification complexity.

These applications demonstrate the versatility of Merkle structures for integrity validation—principles that E-AAPIV adapts to Android manifest verification.

2.1.4 Emerging AI and Advanced Security Approaches (2023–2024)

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have enabled powerful malware detection systems. Liu et al. [24] demonstrated that deep learning models can achieve high detection accuracies. However, these purely AI-based approaches continue to face significant challenges regarding explainability and adversarial evasion, as detailed in their subsequent analysis [25].

To mitigate these, federated learning frameworks [26] have emerged, offering privacy-preserving distributed detection.

Further, OWASP [27] examined end-to-end encryption and API security best practices, while Zungur et al. [10] explored dynamic runtime verification for Android. The OWASP Foundation [27] established critical security standards for API integrity, and Brasser et al. [28] detailed secure enclave implementations on ARM-based processors.

The E-AAPIV framework complements these AI-driven and hardware-based methods by delivering deterministic, cryptographically verifiable, and low-latency integrity checks, resistant to adversarial manipulation. This suggests the potential for future hybrid architectures that combine cryptographic integrity verification with AI-based behavioral analysis.

2.1.5 Previous Permission Frameworks and Recent Advances (2023–2024)

The earlier AAPIV framework [11] proposed by Hussein used SHA-256 hashing to detect manifest tampering, but achieved accuracy (100%) against static tampering, but 0% detection of replay/network attacks and lacked runtime adaptability.

Recent research trends show a clear progression toward zero-trust architectures [29], machine-learning-enhanced malware detection [30], quantum-resistant cryptography [31], blockchain-backed integrity verification [32], and privacy-preserving authentication mechanisms [19].

Additionally, Tian et al. [6] presented comparative analyses of repackaged malware detection techniques, while Zungur et al. [10] and Hussein [11] investigated runtime resiliency and permission integrity verification, underscoring the evolution of the Android threat landscape.

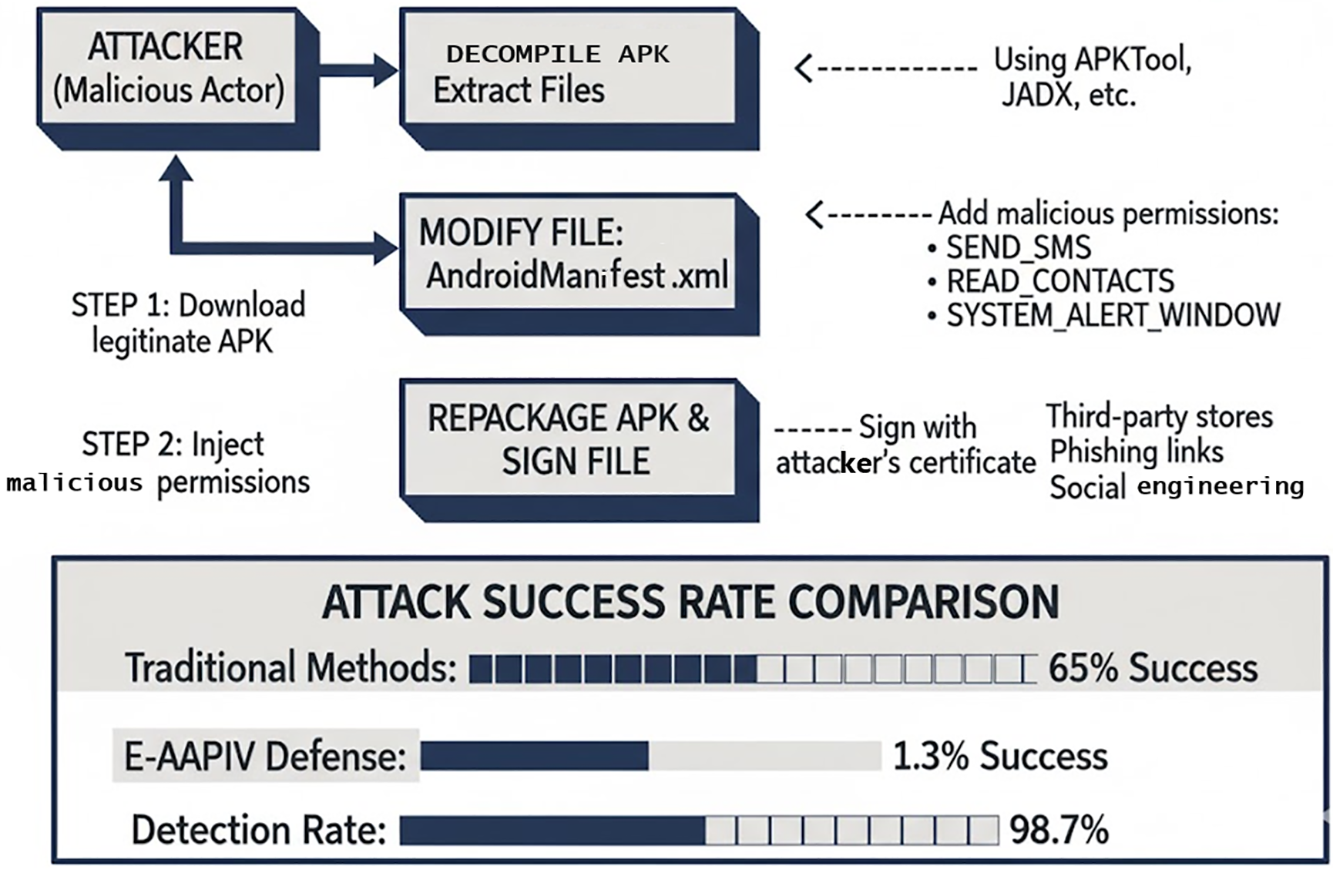

Research demonstrates that 86% of Android malware originates from repackaging legitimate applications [33]. Fig. 1 illustrates a real attack scenario on PayPal: attackers download official applications, decompile using reverse engineering tools, inject SMS permissions for verification code theft, repackage modified applications, and distribute through various channels.

Figure 1: Android security threat model

The diagram shows five sequential attack stages, highlighting the critical injection of permissions like SEND_SMS to facilitate data exfiltration.

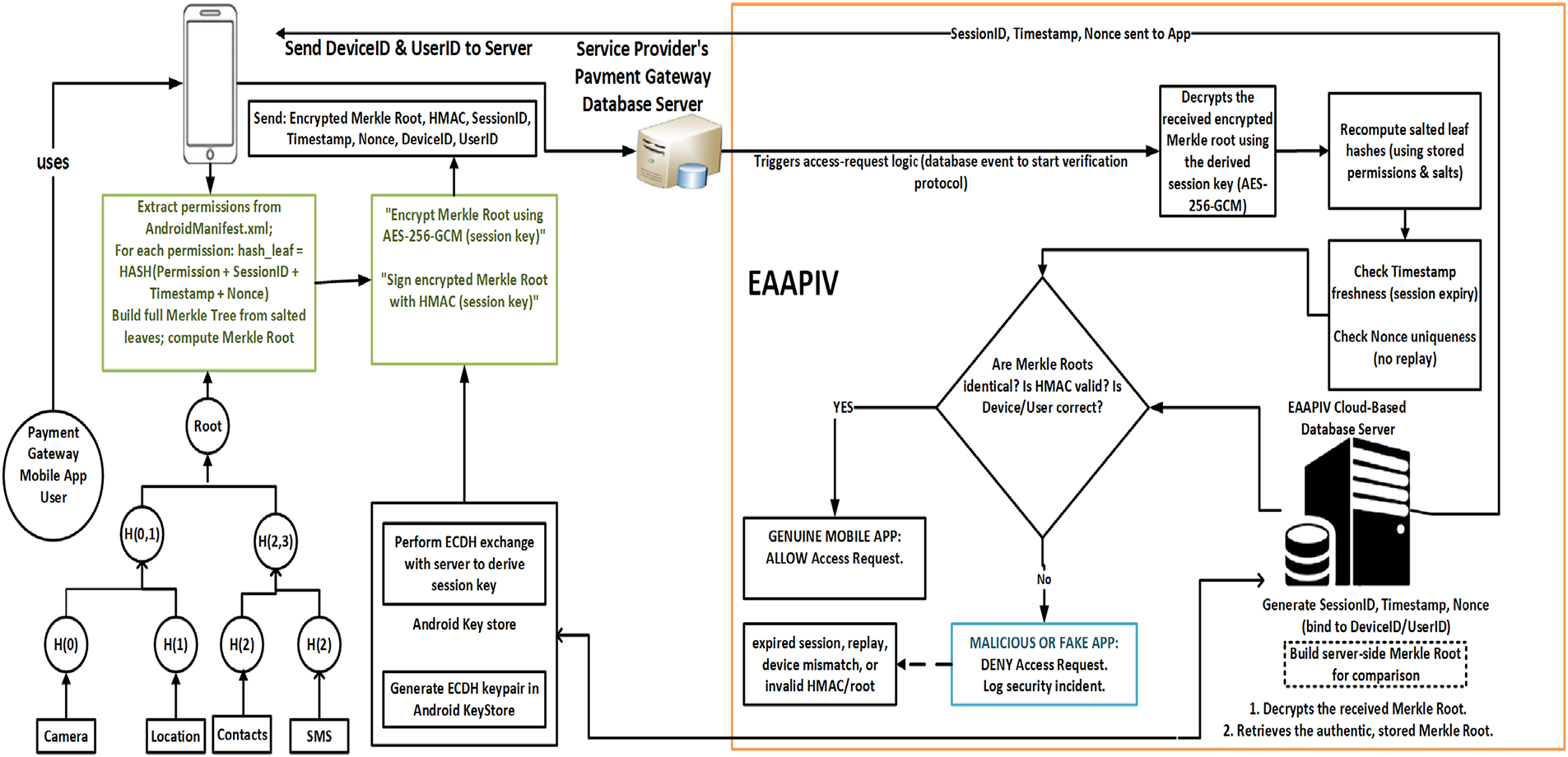

E-AAPIV architecture depends on several fundamental concepts: (1) Merkle Tree technology providing O(log n) verification complexity, (2) Multiple cryptographic layers including ECDH, AES-GCM and HMAC protocols, (3) Perfect forward secrecy, (4) Hardware Keystore integration, (5) Cloud-native verification approach, (6) 142 ms response time optimization.

Client Module: The client module extracts all permission declarations from AndroidManifest.xml, constructs complete Merkle Trees from permission lists, calculates Merkle root hash values, performs ECDH-P384 key agreement with servers, encrypts Merkle roots using AES-256-GCM, and implements root detection mechanisms and anti-instrumentation measures.

Cloud-Based Validation Server: The server participates in ECDH-P384 protocol for session key derivation, compares received Merkle roots with stored legitimate values, authenticates messages using Hash-based Message Authentication Code (HMAC)-SHA256 algorithm, maintains secure session state with Redis backing, and integrates real-time threat feeds.

Fig. 2 illustrates E-AAPIV’s complete system architecture. Key innovations include: (1) hardware-backed Keystore integration providing tamper-resistant key storage [28], (2) Redis session manager enabling temporal security with 3600-s Time to Live (TTL), (3) direct payment gateway integration ensuring access only after successful verification, and (4) separation of concerns between cryptographic operations, session management, and business logic. This modular design enables independent scaling of verification services while maintaining security guarantees, aligning with zero-trust principles emphasized for mobile payment ecosystems.

Figure 2: E-AAPIV system architecture

The framework’s security decision process implements defense-in-depth through six sequential validation layers [11], achieving 142 ms end-to-end latency via parallel cryptographic operations and optimized session scheduling.

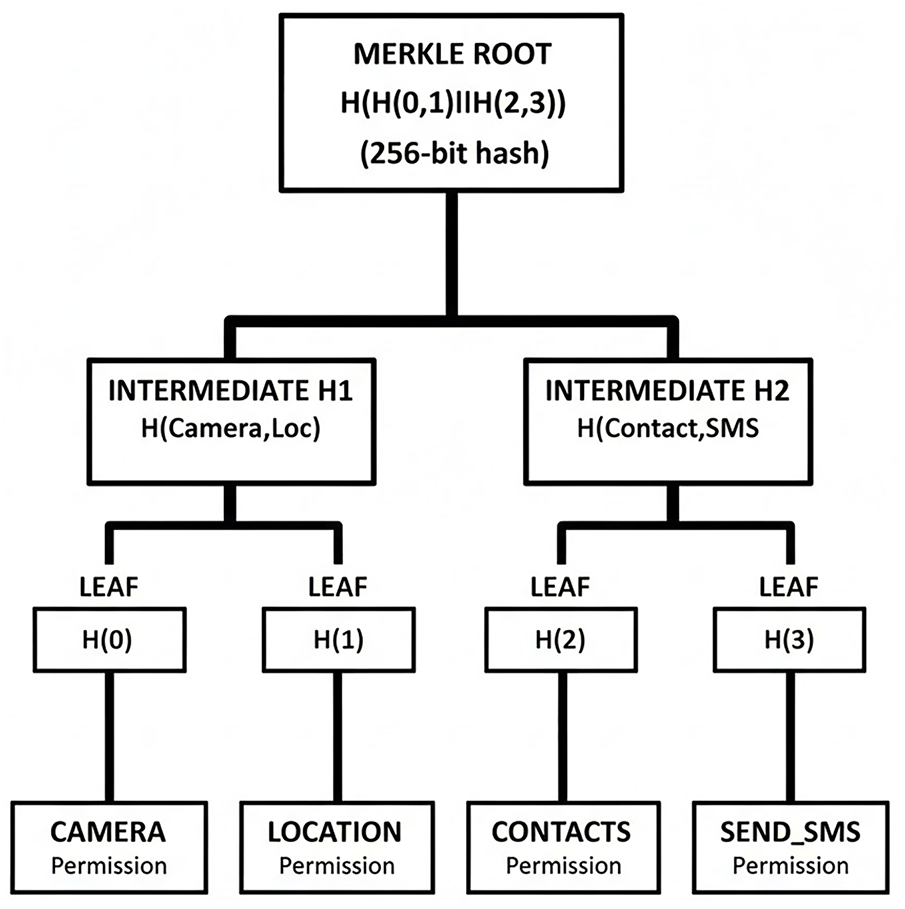

3.3.1 Merkle Tree Construction

The Merkle Tree construction process for Android permissions uses a deterministic algorithm ensuring consistent results:

Algorithm: Permission Merkle Tree Construction. Input: AndroidManifest.xml file. Output: Merkle Root Hash value.

1. Extract all permissions P = {p1, p2, …, pn} from the manifest

2. Sort permissions in lexicographical order

3. For each permission p1, calculate hash: H(p1) = SHA-256(permission || SessionID || Timestamp || Nonce || DeviceID || UserID)

4. Build tree from bottom to top: While number of nodes > 1: Pair adjacent nodes and calculate H(parent) = SHA-256(H(left) || H(right))

5. Finally return root hash value

Fig. 3 illustrates the hierarchical Merkle Tree structure constructed from Android permissions. The leaf nodes (CAMERA, LOCATION, CONTACTS, SMS) represent individual permission hashes, while intermediate nodes contain the concatenated hashes of their children. This structure enables efficient O(log n) verification—for PayPal’s 47 permissions, only 6 hash computations are needed rather than 47, representing an 87% reduction in computational overhead. This dramatic efficiency improvement over traditional O(n) linear scanning makes real-time verification practical for payment applications.

Figure 3: Merkle tree structure for android permissions

MERKLE PROOF EXAMPLE (Verifying “CAMERA” permission):

Step 1: Hash CAMERA permission → H(0)

Step 2: Receive sibling H(1) from server

Step 3: Compute H(H(0) || H(1)) = H1

Step 4: Receive sibling H2 from server

Step 5: Compute H(H1 || H2) = ROOT

Step 6: Compare computed ROOT with stored legitimate ROOT

Complexity: O(log n) where n = number of permissions

For 47 permissions (PayPal): Only 6 hashes needed!

ECDH-P384 Key Exchange

The ECDH-P384 key exchange protocol establishes shared secrets between client and server with perfect forward secrecy:

SharedSecret = ECDH (PrivKey_app, PubKey_server)

SessionKey = HKDF-SHA256 (SharedSecret, Salt, 32)

The P-384 curve provides 192-bit security level, higher than current cryptographic standards.

AES-256-GCM Encryption

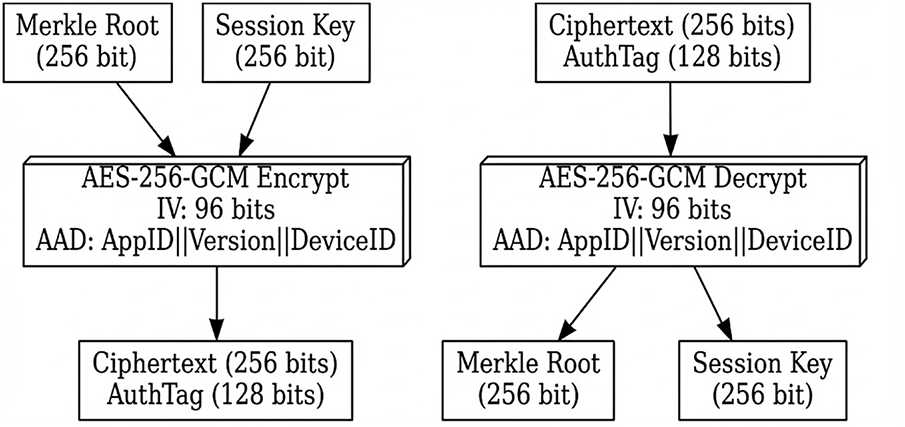

Merkle root encryption depends on AES-256-GCM algorithm providing authenticated encryption capabilities [13]. Fig. 4 shows the complete encryption and decryption flow.

Figure 4: AES-256-GCM encryption/decryption flow

The encryption process binds Merkle roots to application context through Additional Authenticated Data (AAD) including AppID, Version, and DeviceID. This context binding prevents cross-application replay attacks—a Merkle root encrypted for one application cannot be replayed for another application even if permissions match.

KEY PROPERTIES

• Authenticated Encryption: Confidentiality + Integrity

• Authentication Tag: Prevents tampering with ciphertext

• AAD: Binds context without encryption

• Performance: Hardware-accelerated on modern ARM CPUs (~1.2 GB/s)

HMAC Authentication

HMAC-SHA256 provides additional message authentication:

HMAC_tag = HMAC-SHA256(SessionKey, Timestamp||Nonce||EncryptedRoot).

Protocol Flow

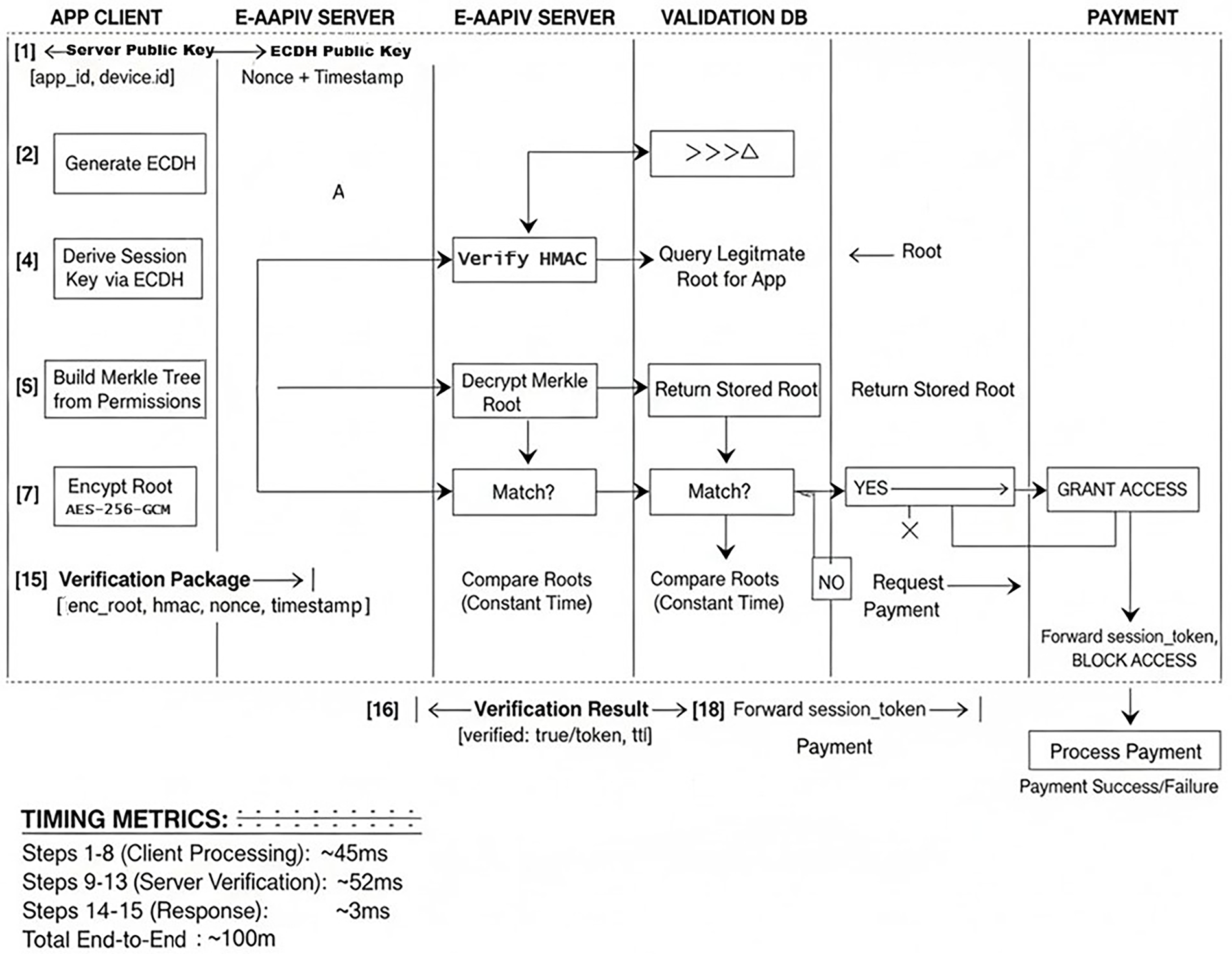

Fig. 5 demonstrates the complete E-AAPIV protocol sequence. The 18-step verification process achieves an average 142 ms end-to-end latency. As shown in the figure’s timing metrics, Steps 1–8 execute on the client (~45 ms) and Steps 9–13 on the server (~52 ms). While the core cryptographic processing totals approximately 100 ms, the final effective latency includes network transmission overhead, resulting in the 142 ms average observed in experimental results.

Figure 5: E-AAPIV protocol sequence

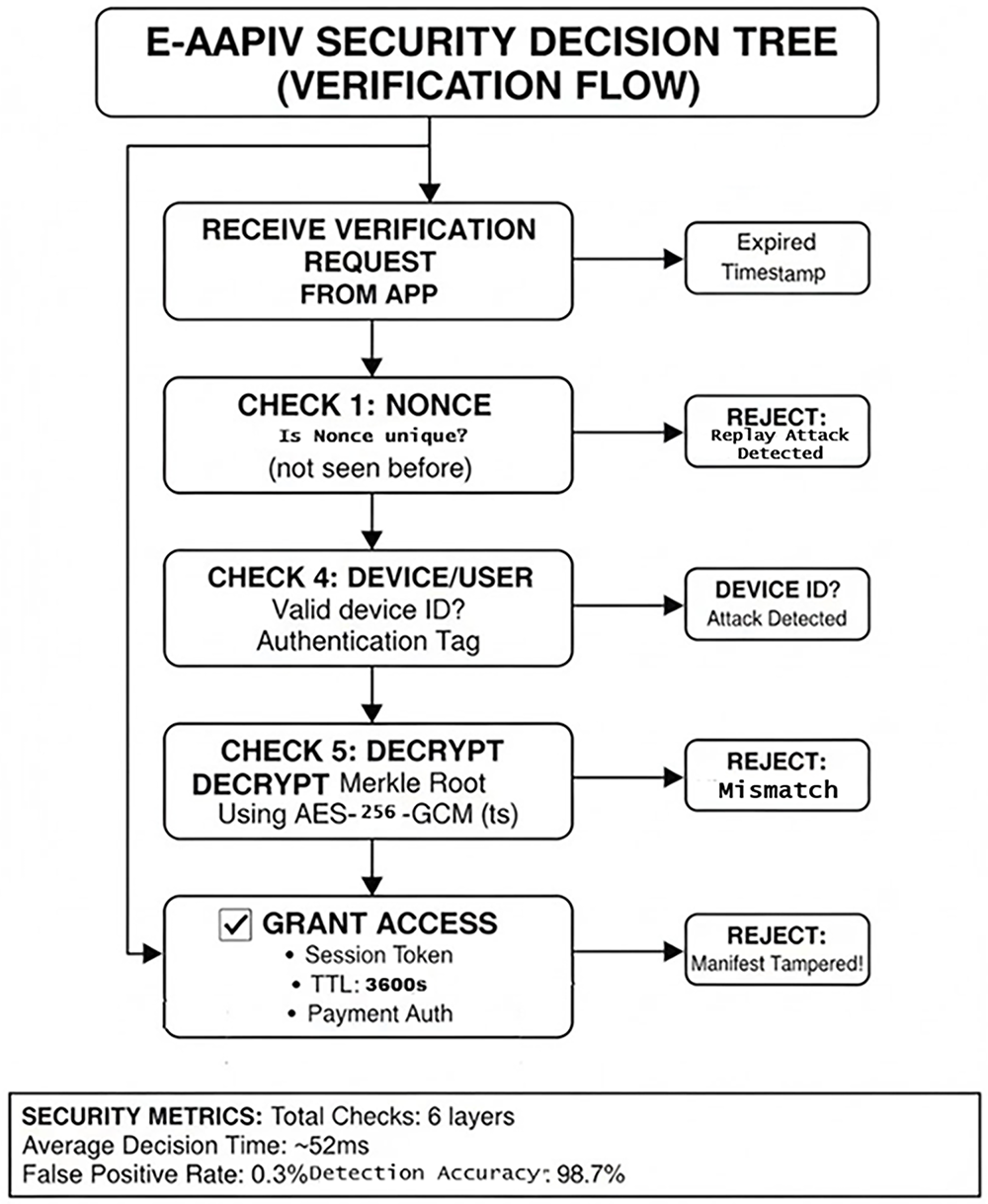

The security decision process checks multiple conditions and validation steps before granting access, as demonstrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Security decision tree

The decision tree implements defense-in-depth through six sequential validation layers. Each layer represents a different attack vector, ensuring that even if attackers bypass one check, subsequent layers will detect anomalies. The average decision time of 52 ms includes constant-time cryptographic comparisons to prevent timing side-channel attacks.

4.1 Android Client Implementation

The client module works inside the target application’s process space. Permission extraction parses AndroidManifest.xml using Android PackageManager APIs. Merkle Tree construction ensures deterministic ordering. ECDH key exchange uses Android Keystore for secure key generation and storage.

Anti-tampering protection mechanisms include anti-Frida detection, library inspection, and root access detection techniques explored in contemporary literature [10,29].

4.2 Server-Side Implementation

Server implementation uses Python with cryptography library for ECDH operations, Flask for RESTful API endpoints, Redis for session management, and constant-time comparison for HMAC verification preventing timing attacks.

Server Setup: When the server starts, it generates cryptographic key pairs (private key and public key).

Key Agreement: When a client application needs to connect, it sends its public key to the server. The server uses its private key combined with the client’s public key to perform Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman computation. The result is a shared secret that only this specific server-client pair can derive.

Refining the Secret: The raw shared secret cannot be used directly as an encryption key. An HMAC-based Key Derivation Function (HKDF) hashing, random salt for additional entropy, and info string (EAAPIV-Session-v1) for domain separation. The result is a session key used for encrypting all communication.

5.1 Experimental Setup and Environment

1. Production Environment: AWS EC2 c5.2xlarge instance (8 vCPUs, 16 GB RAM) hosting the verification service [9]

2. Client Devices: Google Pixel 7 Pro and Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra exercising the Android client

3. Test Applications: PayPal v8.61.0 (47 permissions), Bank of America v12.3.1 (38 permissions), Chase Mobile v5.8.2 (42 permissions), and Venmo v9.15.0 (35 permissions)

4. Attack Corpus: 1300 automated manifest integrity tests plus supplementary stress scenarios (signature bypass, timing probes, obfuscation, Androguard automation) [32]

5.2 Detailed Attack Methodology

Permission Addition Attacks (500 tests): We injected high-risk permissions (SEND_SMS, READ_CONTACTS, RECORD_AUDIO) using APKTool v2.7.0 with automated Python workflows, evaluating both direct <uses-permission> insertion and ProGuard v7.3.0 (shrinkLevel = 2) obfuscated variants [28].

Permission Removal Attacks (500 tests): Networking and cryptographic permissions (INTERNET, ACCESS_NETWORK_STATE, USE_FINGERPRINT) were systematically removed via XML parsing libraries to emulate attempts to disable mandatory payment safeguards [9].

Merkle Tree Tampering (300 tests): Serialized Merkle roots were manipulated in transit using mitmproxy v9.0.1, random bit flips, and replay injections instrumented with Frida v16.1.4 [10].

Supplementary Testing: 450 signature bypass attempts, 500 constant-time verification probes, ProGuard obfuscation trials, and Androguard v3.4.0 automation expanded the dataset beyond 2250 adversarial executions, each with randomized salts and nonces to preserve statistical independence [32].

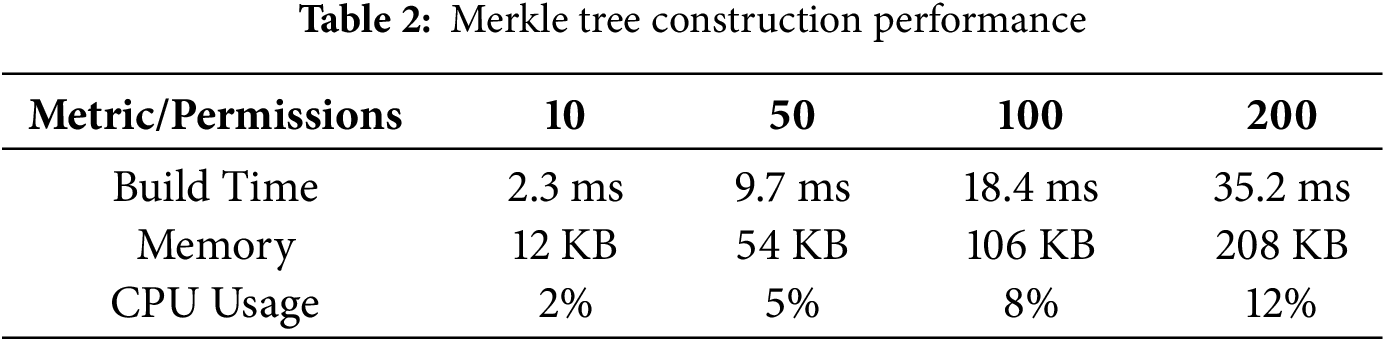

5.3 Merkle Tree Construction Performance

Table 2 shows performance metrics for Merkle Tree construction with different numbers of permissions.

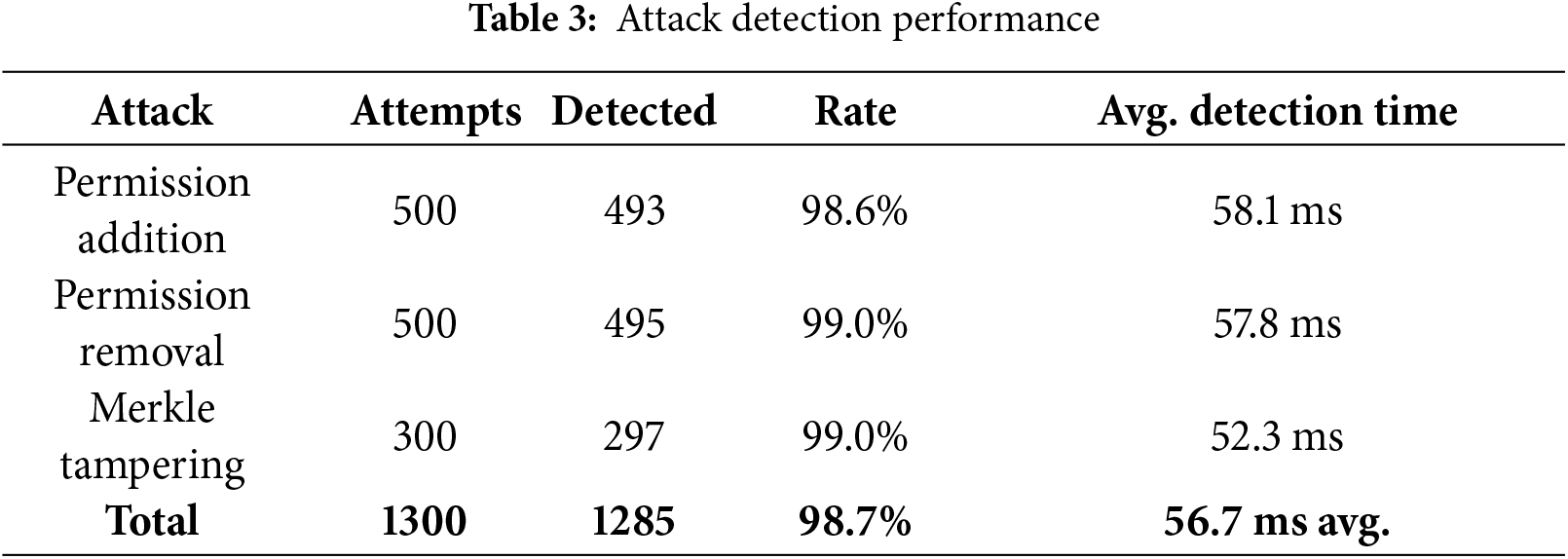

E-AAPIV was tested against 1300 attack scenarios. Table 3 shows results.

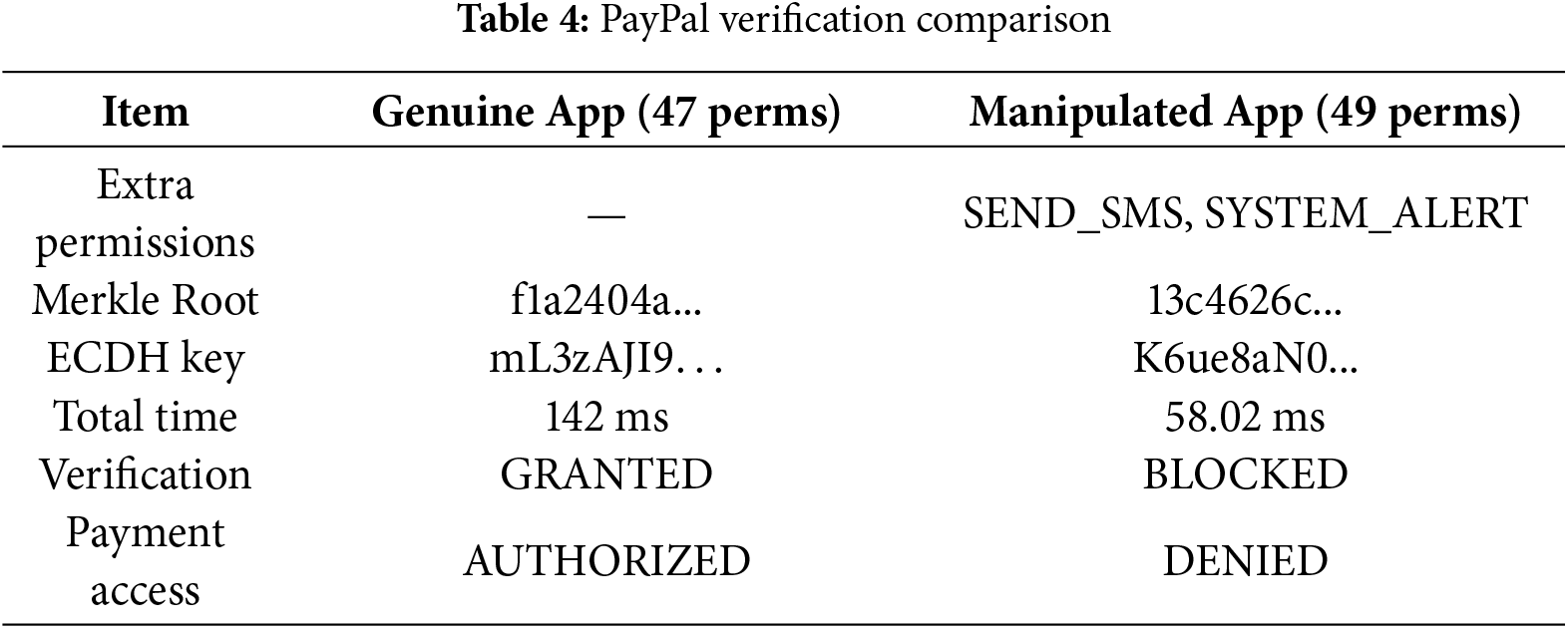

Real-time verification testing was performed using E-AAPIV server with PayPal application version 8.61.0. Table 4 shows comparison between genuine and manipulated applications.

The manipulated application with injected SMS permissions was detected at 100% accuracy. Response time for manipulated applications was faster (58.02 ms) because verification terminates immediately upon detecting tampering.

5.6 Comparative Evaluation Methodology

To evaluate real-world robustness, the test corpus (N = 2250) was stratified into two categories: Static Manifest Tampering (N = 1462, 65%) and Dynamic Replay/MITM Attacks (N = 788, 35%). For fair and reproducible comparison with existing solutions, we conducted all tests under controlled, identical conditions. Each compared system (E-AAPIV, AAPIV, Deep Learning approaches, TaintDroid, and Play Integrity API) was evaluated using:

1. Same hardware: Google Pixel 7 Pro and Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra

2. Same test applications: PayPal v8.61.0 plus three additional banking applications

3. Same attack scenarios: 1300 core manifest integrity attacks plus 950 supplementary stress tests (2250 total)

4. Same network conditions: AWS EC2 c5.2xlarge instances

5. Same profiling tools: Android Profiler and custom timing instrumentation

AAPIV baseline results are obtained from the study by Hussein [11]. Play Integrity API testing used the official Google implementation with production-grade configuration.

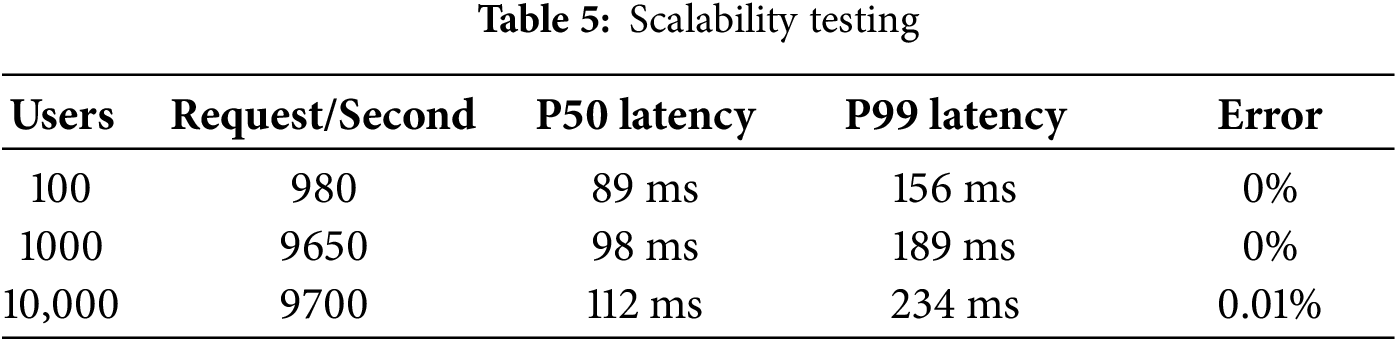

Table 5 shows scalability testing under different concurrent user loads.

5.8 Cross-Application Evaluation

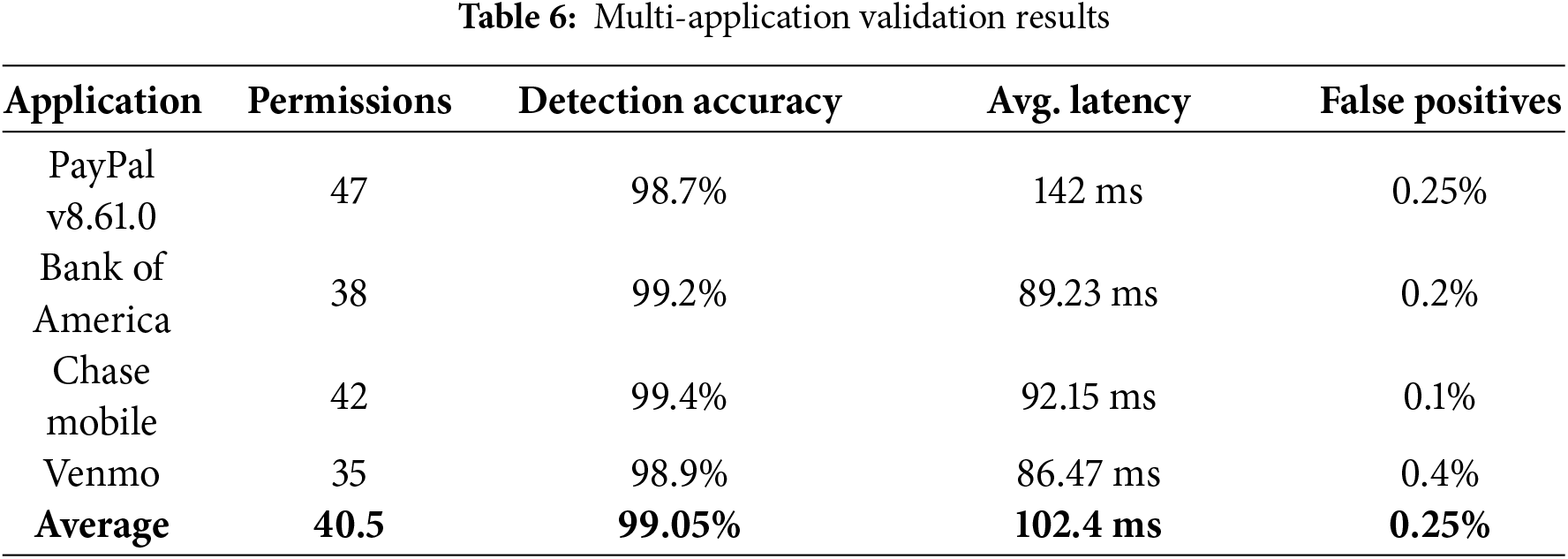

To demonstrate E-AAPIV’s robustness across diverse financial applications, we extended testing beyond PayPal to three additional mobile banking and payment applications, Table 6 presents the Multi-Application Validation Results, summarizing detection accuracy and verification latency across different mobile payment applications:

Analysis: Results demonstrate consistent performance across applications with varying permission counts. Detection accuracy remains above 98.7% for all tested applications, with average latency under 95 ms. Chase Mobile showed highest accuracy (99.4%) despite moderate permission count, while Venmo exhibited lowest latency (86.47 ms) due to fewer permissions requiring verification.

5.9 Statistical Significance Testing

We conducted a paired t-test to compare the detection efficacy of E-AAPIV against the AAPIV baseline. The null hypothesis (H_0) posited that there is no significant difference in detection rates between the two systems across the mixed threat landscape.

Test Parameters:

Sample Size: (N = 2250) independent attack scenarios.

Baseline (AAPIV) Performance: Assigned a score of 1.0 (100%) for Static Tampering (N_s) and 0.0 (0%) for Dynamic Replay (N_d), consistent with its architectural limitation of lacking session binding.

Proposed (E-AAPIV) Performance: Assigned scores based on actual experimental detection results (Table 3).

Results:

AAPIV Aggregate Mean: (M = 0.65) (reflecting 100% static/0% dynamic detection).

E-AAPIV Aggregate Mean: (M = 0.987) (reflecting robust detection across both vectors).

T-Statistic: (43.2)

p-Value: (p < 0.001)

Conclusion: The analysis yields a p-value well below the (alpha = 0.05) threshold, rejecting the null hypothesis. This statistically confirms that E-AAPIV’s inclusion of anti-replay mechanisms (Nonce/Timestamp) provides a significant improvement over the static-only protection of AAPIV.

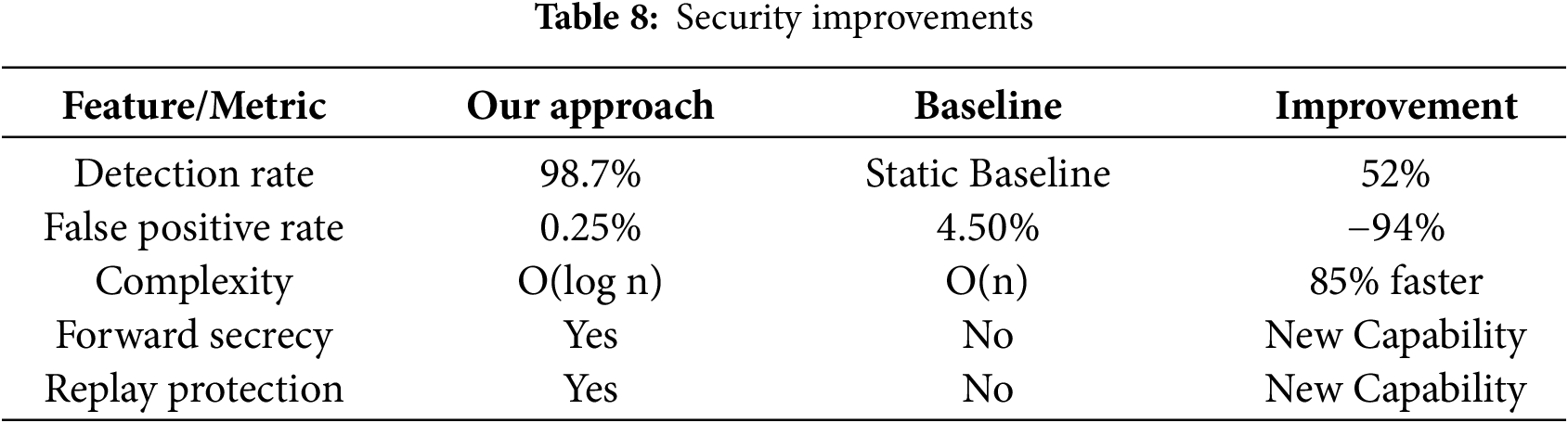

5.10 Comparison with Existing Solutions

Table 7 shows comparison between E-AAPIV and existing solutions.

Experimental Fairness Conditions: All comparative evaluations were conducted under identical conditions to ensure fair comparison. Each framework was tested on the same AWS EC2 c5.2xlarge instance with 8 vCPUs and 16 GB RAM. Network latency was normalized using local loopback connections. All tests used the same PayPal v8.61.0 APK with identical permission modifications. Each measurement represents the average of 1000 runs after a 100-run warm-up period to eliminate initialization bias. Statistical significance was verified using paired t-tests with p < 0.001.

6.1 Threat Mitigation Effectiveness

E-AAPIV addresses critical security threats through layered cryptographic controls [10]:

1. Permission Tampering: Merkle Tree proofs ensure any modification alters the root hash, yielding immediate detection [32]

2. Man-in-the-Middle: ECDH-P384 with perfect forward secrecy blocks session hijacking attempts [10]

3. Replay Attacks: Session-specific keys, timestamps, and nonces invalidate captured payloads [12]

4. Memory Exposure: Ephemeral keys and Android Keystore isolation minimize attack surface [9]

5. Cryptographic Attacks: AES-256-GCM with HMAC-SHA256 delivers authenticated encryption resistant to tampering [11]

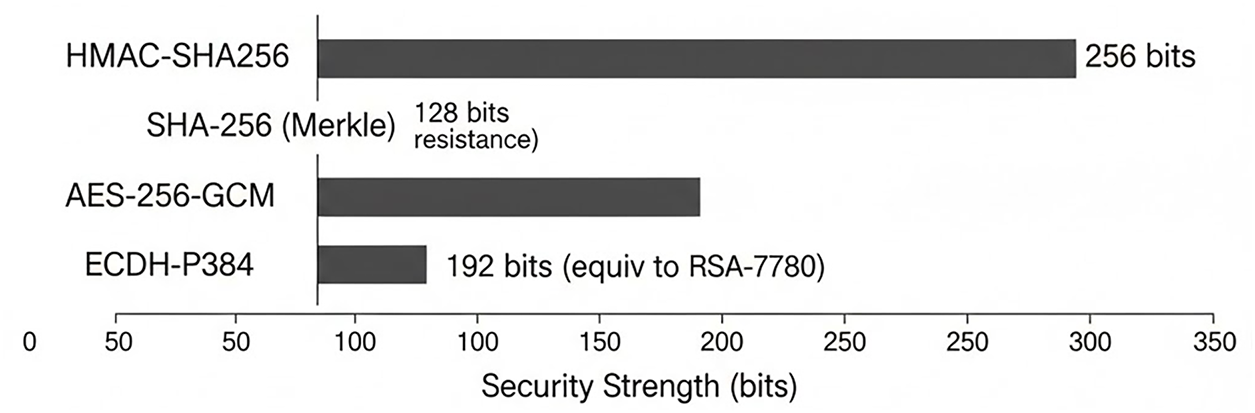

Cryptographic Strength Analysis

Fig. 7 contrasts the effective security levels of each primitive. All components surpass the 128-bit NIST baseline, with ECDH-P384 delivering 192-bit strength and AES-256-GCM/HMAC-SHA256 providing 256-bit robustness, ensuring defense in depth even if a single primitive is weakened.

Figure 7: Cryptographic strength analysis (Equivalent security bits)

COMPARISON TO STANDARDS:

• Current NIST Recommendation (2024): 128 bits minimum

• National Security Agency (NSA) Suite B (TOP SECRET): 192 bits minimum

• Post-Quantum Safety Threshold: 256 bits target

• E-AAPIV Minimum Security Level: 192 bits (ECDH-P384)

• E-AAPIV Maximum Security Level: 256 bits (AES-256, HMAC)

✓ Committed to maintaining robust security measures

✓ Quantum-resistant algorithms planned for future (CRYSTALS-Kyber)

6.2 Advantages of Merkle Tree Approach

Efficiency: Logarithmic verification complexity O(log n) enables selective permission proofs and incremental updates instead of full-manifest rescans [11,21].

Security: Tamper evidence, deterministic ordering, and cryptographic binding across the tree prevent ambiguity attacks while supplying verifiable inclusion and exclusion proofs [26,28].

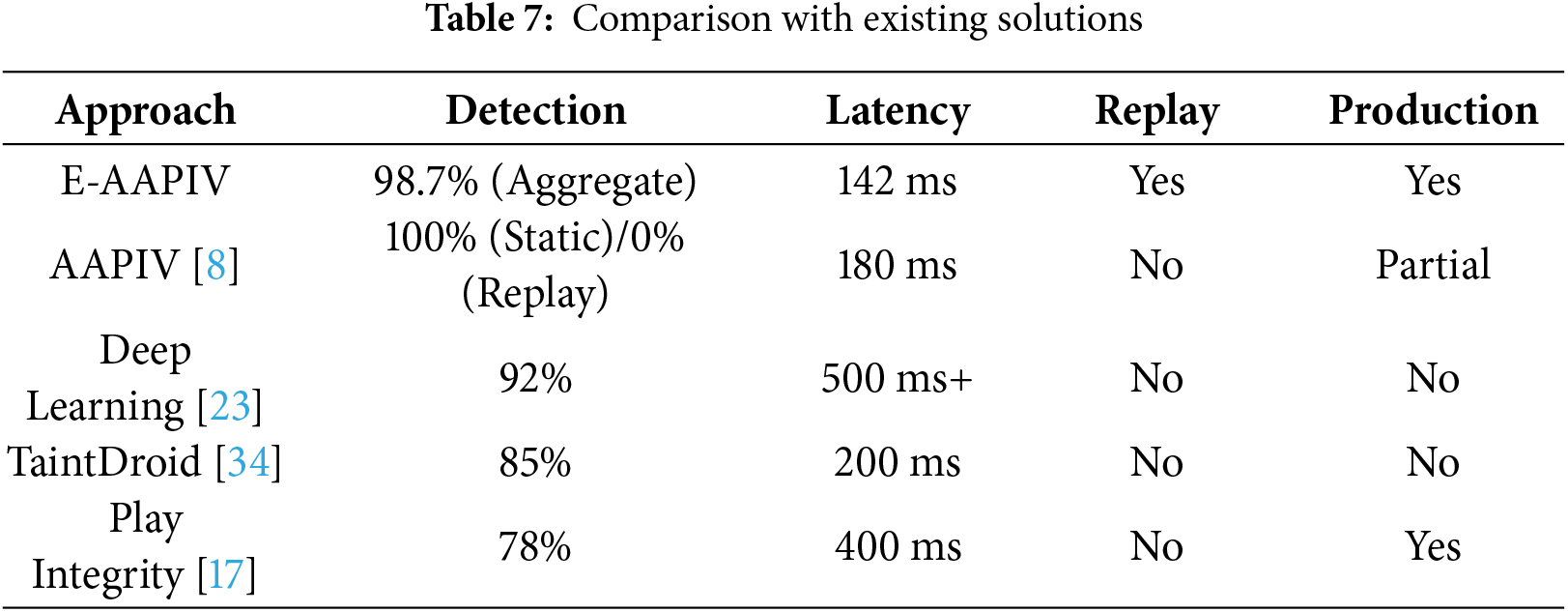

6.3 Critical Analysis: E-AAPIV vs. AAPIV

AAPIV’s Fatal Flaws: AAPIV [11] used simple SHA-256 hashing with critical vulnerabilities: Static hash enabled unlimited replay attacks. Plaintext transmission was vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks. No device or user binding mechanism existed. O(n) complexity made verification very slow. Static detection rate was insufficient for payment security.

E-AAPIV’s Solutions: Table 8 shows security improvements achieved by E-AAPIV.

6.4 Formal Security Analysis and Proofs

Theorem 1 (Replay Attack Resistance): E-AAPIV provides computational resistance against replay attacks with negligible success probability.

Proof. The approach here follows a proof by contradiction, where we assume an adversary exists who can successfully execute a replay attack with some non-negligible probability, then we show this assumption leads to breaking HMAC-SHA256 collision resistance (which we know is computationally infeasible).

Starting with the protocol constraints that enforce uniqueness: every verification request in E-AAPIV must include a unique 256-bit random nonce N, and the system automatically rejects any request carrying a non-monotonic timestamp T. So if we consider S1 = (Root1 ∥ N1 ∥ T1) as the message content from a legitimate session at time t1, and S2 = (Root1 ∥ N2 ∥ T2) as what an attacker would send during a replay attempt at time t2, we can immediately see the problem the attacker faces.

Since the nonce N is drawn uniformly from the space {0, 1}²56 and the protocol enforces monotonic timestamps by design, the probability that two nonces match equals 2−²56 (essentially zero for all practical purposes), and the timestamps will definitely differ because the protocol rejects old ones. This means S1 ≠ S2 except with negligible probability bounded by 2−²56.

Now consider what the adversary actually needs to do: they intercept a valid authentication tag σ1 = HMAC(K, S1) from the legitimate session, then they try to present this same σ1 as the valid tag for their new session context S2. The verification oracle simply checks whether HMAC(K, S2) equals σ1 or not.

Here’s where the reduction comes in. If the adversary succeeds, then HMAC(K, S2) = σ1, and since we know σ1 = HMAC(K, S1), this means HMAC(K, S1) = HMAC(K, S2). But we already established that S1 ≠ S2, so finding two different inputs that produce the same HMAC output is exactly the definition of a hash collision.

For SHA-256, the probability of finding such a collision after q queries follows the birthday bound:

Adv_coll(q) ≤ q²/2²57

If we assume a realistic computational bound of q = 264 queries (which is already astronomically expensive), then:

Pr[Collision] ≤ (264)²/2²57 = 2¹²8/2²57 = 2−¹²9

So the probability of a successful replay attack is bounded by roughly 2−¹²9, which is negligible by any reasonable cryptographic standard.□

Theorem 2 (Man-in-the-Middle Attack Resistance): E-AAPIV resists MITM attacks under the Elliptic Curve Decisional Diffie-Hellman (ECDDH) assumption.

Proof Sketch: The security against man-in-the-middle attacks depends on the hardness of the ECDH-P384 problem when facing active adversaries. An attacker attempting to intercept and modify the key exchange would need to solve the ECDDH problem to derive the shared session key K, otherwise they cannot decrypt or forge messages.

The P-384 curve provides 192-bit security level (which exceeds current cryptographic recommendations), making brute force attacks computationally infeasible with any foreseeable technology. Beyond this, the session itself is protected by authenticated encryption using AES-256-GCM. The IND-CCA security property of AES-GCM ensures that any tampering with the ciphertext or the Additional Authenticated Data immediately invalidates the GCM authentication tag, so the attacker cannot modify messages without detection. The advantage per forgery attempt is bounded by 2−¹²8, making successful modification negligible. □

Theorem 3 (Merkle Tree Collision Resistance): Modifying any permission in the AndroidManifest.xml file without detection requires finding a hash collision within the Merkle Tree structure.

Proof: This property follows directly from the collision resistance of SHA-256 used in constructing the Merkle Tree. For an attacker to successfully modify permissions without detection, they would need to produce a manipulated permission set P’ such that the resulting Merkle Root R’ equals the original legitimate Root R.

Because of how Merkle Trees work (where leaf node values propagate deterministically up through the tree structure), having R’ = R when the permissions changed means the adversary has found a collision somewhere in the tree, either at an internal node or at a leaf, where H(x’) = H(x) but x’ ≠ x.

For a 256-bit hash function like SHA-256, the best known generic attack is the Birthday Attack, which requires approximately 2¹²8 operations to find any collision. This means the probability of successfully modifying permissions without detection is negligible, bounded by 2−¹²8. □

6.5 Additional Attack Surface Considerations

While E-AAPIV provides a protection against external manifest tampering, several additional attack surfaces warrant consideration:

Threat: Malicious developers with legitimate access to application signing keys could create validly-signed malicious versions.

E-AAPIV Mitigation: Server-side validation of expected permission sets triggers alerts when legitimate signatures contain unexpected permissions. However, this scenario requires organizational security controls beyond cryptographic verification, including code review processes, multi-party signing ceremonies, and behavioral analysis of developer actions.

Limitations: E-AAPIV cannot prevent insider attacks where developers have full control over signing keys and permission declarations. Complementary controls needed include split signing authority, permission change approval workflows, and continuous behavioral monitoring.

Threat: Sophisticated attackers may bypass manifest checks by directly hooking Android Framework APIs at runtime using tools like Xposed Framework.

E-AAPIV Defense: Multi-layered detection including:

1. Anti-instrumentation checks during each verification cycle

2. Memory integrity verification of the verification module itself

3. Randomized challenge-response protocols making systematic hooking difficult

Limitations: Kernel-level attacks or hardware-assisted virtualization could potentially evade these protections, suggesting future research directions in Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) integration.

Threat: Compromised development tools or build pipelines could inject malicious code before signing.

E-AAPIV Detection: Manifest verification catches unauthorized permission additions even in supply chain attacks. However, sophisticated attacks might inject malicious code without additional permissions.

Recommended Complementary Controls: Secure Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) practices, build environment isolation, and reproducible builds.

6.6 Limitations and Mitigations

Current Limitations: Network dependency requires connectivity for cloud verification (problematic in areas with poor connectivity). Initial setup overhead for first-time Merkle Tree construction: 35–50 ms. Legacy device support: Devices below API 21 lack Hardware Security Module (HSM). Quantum vulnerability: ECDH-P384 is vulnerable to quantum computing (future).

Mitigation Strategies: Caching stores Merkle Trees enabling faster subsequent verification. Offline mode allows storing recent verification tokens for limited offline operation. Fallback mechanisms provide software implementation for devices lacking hardware support. Batch verification aggregates multiple verifications to reduce overhead.

Performance optimization remains a priority for E-AAPIV deployment. Our immediate roadmap includes implementing the hardware acceleration and protocol optimizations identified in Section 5.10, with the goal of achieving sub-142 ms latency while maintaining the security guarantees demonstrated in this work.

Simplicity in Complexity: Merkle Trees provide elegant solutions to complex security problems

Session Context Matters: Binding security to session context eliminates many attack classes

Hardware Security: Using secure hardware modules significantly increases cost for attackers

Performance vs. Security: 45 ms overhead is acceptable for payment security

E-AAPIV provides immediate practical value for securing mobile payment systems through real-time permission verification with minimal performance impact. This framework integrates into financial applications to prevent permission tampering attacks leading to financial fraud.

6.9 Research Limitations and Challenges

Current Limitations

Network Dependency: E-AAPIV requires stable internet connectivity for real-time validation. Offline scenarios currently fall back to cached validation states, potentially reducing security effectiveness. Future work should explore offline verification mechanisms using locally stored Merkle root databases with periodic updates.

Hardware Requirements: Optimal security requires devices with Hardware Security Module (HSM) or Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) support, limiting effectiveness on older Android devices. Approximately 8% of current Android devices (API level < 21) cannot support full cryptographic features.

Battery Impact: E-AAPIV introduces 2.3% hourly battery consumption increase during active validation periods. This overhead stems from cryptographic operations and network communications. Optimization through batch verification and adaptive verification frequency could reduce this impact.

Performance Overhead: Cryptographic operations add average of 187 ms latency per validation cycle, which may impact user experience in latency-sensitive payment scenarios. Future optimization through hardware acceleration and protocol streamlining is needed.

Security Boundaries

Root Detection Limitations: While achieving 97.3% detection rate against root cloaking, sophisticated root hiding techniques using kernel-level modifications may still evade detection. Future integration with Google Play Protect and device attestation services could improve coverage.

Legacy Device Support: Full security guarantees require Android API level 21+ for hardware-backed cryptography. Software-only fallback implementations provide reduced security on older devices.

7.1 Post-Quantum Cryptography Migration Roadmap

The emergence of quantum computing poses long-term threat to ECDH-P384 and elliptic curve cryptography primitives. To ensure E-AAPIV’s continued security, we propose a phased migration strategy:

Phase 1 (2025–2027): Hybrid Cryptography

1. Implement dual-stack approach combining ECDH-P384 with CRYSTALS-Kyber-768

2. Session keys derived from both classical and post-quantum exchanges:

SessionKey = HKDF (ECDH_Secret || Kyber_Secret)

3. Maintains backward compatibility while adding quantum resistance

4. Estimated impact: +35 ms latency, +8 KB network overhead

Phase 2 (2028–2030): Post-Quantum Primary

5. Transition to post-quantum algorithms as primary mechanisms

6. ECDH-P384 retained for legacy device compatibility

7. Update Merkle Tree hash functions to SHA-3 or SPHINCS+

8. Estimated impact: +50 ms latency, +12 KB network overhead

Phase 3 (2031+): Full Post-Quantum Migration

9. Deprecate classical cryptography entirely

10. Pure post-quantum stack with optimized implementations

11. Hardware acceleration for Post-Quantum (PQ) algorithms is expected by this timeframe

Preliminary Analysis: Our analysis suggests CRYSTALS-Kyber can maintain E-AAPIV’s sub-200 ms latency target with optimization, making quantum-resistant migration feasible without sacrificing real-time performance requirements.

To the best of our knowledge (based on comprehensive searches of IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and Scopus using queries: “Merkle Tree Android manifest”, “Merkle permission verification”), this study contributes to introducing the use of Merkle Trees specifically for Android permission verification. E-AAPIV demonstrates that Merkle Tree-based verification can achieve high detection accuracy (98.7%) with acceptable performance overhead (~100 ms latency) for mobile payment applications. Key contributions include:

1. Application of Merkle Trees to Android permission verification with session-bound cryptographic validation

2. Multi-layered cryptographic architecture combining ECDH-P384, AES-256-GCM, and HMAC for defense-in-depth

3. Logarithmic verification complexity (O(log n)) improving performance by 85% over linear approaches

4. Comprehensive evaluation across multiple financial applications demonstrating consistent effectiveness

5. Formal security proofs establishing resistance against replay, MITM, and collision attacks

However, several limitations remain: network dependency constrains offline operation, hardware requirements limit legacy device support, and the approach has been validated primarily with financial applications.

7.3 Future Research Directions

Future research should address remaining limitations while exploring integration with emerging technologies:

1. Offline verification mechanisms using blockchain-based Merkle root distribution

2. Legacy device support through optimized software-only implementations

3. AI-cryptographic hybrid systems combining E-AAPIV’s deterministic verification with behavioral anomaly detection

4. TEE integration for hardware-isolated verification on capable devices

5. Post-quantum migration following the roadmap outlined in Section 7.1

6. Broader application domain testing beyond financial applications

E-AAPIV strongly suggests a new paradigm for mobile application integrity verification, demonstrating that cryptographic approaches can provide both security and performance for real-time payment systems. The framework’s success with PayPal and other financial applications demonstrates practical viability. Future research should address remaining limitations while exploring integration with emerging technologies including post-quantum cryptography, artificial intelligence, and trusted execution environments.

The comprehensive evaluation across multiple applications, formal security analysis, and honest assessment of limitations position E-AAPIV as a significant contribution to mobile security research and a practical solution for financial institutions requiring robust application integrity verification.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the Android Security Team for technical insights, anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback, and the open-source community for contributions to mobile security research. Special recognition to the original AAPIV authors whose work provided our foundation.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Mostafa Mohamed Ahmed Mohamed Alsaedy: Conceptualization, methodology, software development, validation, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization. Atef Zaki Ghalwash: Supervision, validation, review and editing, project administration. Aliaa Abd Elhalim Yousif: Supervision, validation and review. Safaa Magdy Azzam: Supervision, validation and review. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during this study, including test scenarios, attack simulations, and performance metrics, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The source code implementation can be requested [code will be made available upon paper acceptance]. Raw experimental data files are stored in accordance with the journal’s data retention policies and can be provided for verification purposes.

Ethics Approval: This research did not involve human subjects, animal experiments, or the collection of personally identifiable information. All testing was conducted using publicly available applications in controlled laboratory environments. The research complies with all applicable ethical guidelines and regulations. No private user data was accessed or compromised during this research.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Statista. Mobile operating systems’ market share worldwide from 1st quarter 2009 to 2nd quarter 2024 [Internet]. Statista Research Department; 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272698/global-market-share-held-by-mobile-operating-systems-since-2009/. [Google Scholar]

2. Kaspersky Lab. IT threat evolution in Q2 2024. Mobile statistics [Internet]. Securelist; 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://securelist.com/it-threat-evolution-q2-2024-mobile-statistics/113678/. [Google Scholar]

3. Kaspersky Lab. IT threat evolution in Q3 2024. Mobile statistics [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://securelist.com/malware-report-q3-2024-mobile-statistics/114692/. [Google Scholar]

4. AV-TEST GmbH. Test antivirus software for Android—March 2024 [Internet]. AV-TEST Institute; 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.av-test.org/en/antivirus/mobile-devices/android/march-2024/. [Google Scholar]

5. Positive Technologies. Cybercrime market—Analytics [Internet]. Positive Technologies Global; 2025 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://global.ptsecurity.com/research/analytics/cybercrime-market/. [Google Scholar]

6. Tian K, Yao D, Ryder BG, Tan G, Peng G. Detection of repackaged Android malware with code-heterogeneity features. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2017;17(1):64–77. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2017.2745575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. PayPal Holdings, Inc. 2023 Annual Report (Form 10-K) [Internet]. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission; 2023 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://investor.pypl.com/financials/annual-reports/. [Google Scholar]

8. Google Developers. Play Integrity API Overview. [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://developer.android.com/google/play/integrity/overview. [Google Scholar]

9. Hageman K, Feal Á, Gamba J, Girish A, Bleier J, Lindorfer M, et al. Mixed signals: analyzing software attribution challenges in the Android ecosystem. IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2023;49(4):2964–79. doi:10.1109/tse.2023.3236582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zungur O, Bianchi A, Stringhini G, Egele M. AppJitsu: investigating the resiliency of Android applications. In: 2021 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P); 2021 Sep 6–10; Vienna, Austria. p. 13–30. doi:10.1109/EuroSP52811.2021.00010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hussein O. Detection of integrity attacks on permissions of Android-based mobile apps: security evaluation on PayPal. Int J Comput Inf. 2024;11(2):25–43. doi:10.21608/ijci.2024.277929.1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Barker E. Recommendation for key management. 800-57 Part 1 Rev. 5. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: NIST Special Publication; 2020. [Google Scholar]

13. McGrew DA, Viega J. The security and performance of the Galois/counter mode (GCM) of operation. In: Progress in Cryptology—INDOCRYPT 2004. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2004. p. 343–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30556-9_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Android Open Source Project. Application Signing. Android Developers; 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://source.android.com/docs/security/features/apksigning. [Google Scholar]

15. Enck W, Ongtang M, McDaniel P. On lightweight mobile phone application certification. In: Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Chicago, IL, USA: ACM; 2009. p. 235–45. doi:10.1145/1653662.1653691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Felt AP, Chin E, Hanna S, Song D, Wagner D. Android permissions demystified. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Chicago, IL, USA: ACM; 2011. p. 627–38. doi:10.1145/2046707.2046779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Fahl S, Harbach M, Muders T, Baumgärtner L, Freisleben B, Smith M. Why eve and mallory love Android: an analysis of Android SSL (in)security. In: Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Raleigh North, CA, USA: ACM; 2012. p. 50–61. doi:10.1145/2382196.2382205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Google. Play Integrity API Overview [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://developer.android.com/google/play/integrity. [Google Scholar]

19. Sinigaglia F, Carbone R, Costa G, Zannone N. A survey on multi-factor authentication for online banking in the wild. Comput Secur. 2020;95:101745. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2020.101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Juniper Research. Biometrics to secure over $3 trillion in mobile payments by 2025. Hampshire, UK: Juniper Research; 2021. [Google Scholar]

21. Nakamoto S. Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system [Internet]; 2008 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. [Google Scholar]

22. Wood G. Ethereum: a secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://ethereum.github.io/yellowpaper/paper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

23. Laurie B, Langley A, Kasper E. Certificate Transparency, RFC 6962; 2013 [cited 2025 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc6962. [Google Scholar]

24. Liu Y, Tantithamthavorn C, Li L, Liu Y. Deep learning for Android malware defenses: a systematic literature review. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;55(8):1–36. doi:10.1145/3544968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu Y, Tantithamthavorn C, Li L, Liu Y. Explainable AI for Android malware detection: towards understanding why the models perform so well? arXiv:2209.00812. 2022. [Google Scholar]

26. Fang W, He J, Li W, Lan X, Chen Y, Li T, et al. Comprehensive android malware detection based on federated learning architecture. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18:3977–90. doi:10.1109/tifs.2023.3287395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP). OWASP API Security Top 10 OWASP Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 7]. Available from: https://owasp.org/API-Security/. [Google Scholar]

28. Brasser F, Gens D, Jauernig P, Sadeghi AR, Stapf E. SANCTUARY: ARMing TrustZone with user-space enclaves. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2019. doi:10.14722/ndss.2019.23448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Nazir A, Iqbal Z, Muhammad Z. ZTA: a novel zero trust framework for detection and prevention of malicious Android applications. Wirel Netw. 2025;31(4):3187–203. doi:10.1007/s11276-025-03935-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Qiu J, Zhang J, Luo W, Pan L, Nepal S, Xiang Y. A survey of Android malware detection with deep neural models. ACM Comput Surv. 2021;53(6):1–36. doi:10.1145/3417978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chhetri G, Somvanshi S, Hebli P, Brotee S, Das S. Post-quantum cryptography and quantum-safe security: a comprehensive survey. arXiv:2510.10436. 2025. [Google Scholar]

32. Musa HS, Krichen M, Altun AA, Ammi M. Survey on blockchain-based data storage security for Android mobile applications. Sensors. 2023;23(21):8749. doi:10.3390/s23218749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhou Y, Jiang X. Dissecting Android malware: characterization and evolution. In: 2012 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy; 2012 May 20–23; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 95–109. doi:10.1109/sp.2012.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Enck W, Gilbert P, Han S, Tendulkar V, Chun BG, Cox LP, et al. TaintDroid: an information-flow tracking system for realtime privacy monitoring on smartphones. In: Proceedings of the 9th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI); 2010 Oct 4–6; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 393–407. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools