Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Resilient Security Framework for Lottery and Betting Kiosks under Ransomware Attacks

Independent Researcher, Mount Holly, NJ 08060, USA

* Corresponding Author: Sapan Pandya. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 637-651. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.073670

Received 23 September 2025; Accepted 26 November 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Ransomware has evolved from opportunistic malware into a global economic weapon, crippling critical services and extracting billions in illicit revenue. While most research has centered on enterprise networks and healthcare systems, an equally vulnerable frontier is emerging in lottery and betting kiosks—self-service financial Internet of Things (IoT) devices that handle billions of dollars annually. These terminals operate unattended, rely on legacy operating systems, and interact with sensitive transactional data, making them prime ransomware targets. This paper introduces a Resilient Security Framework (RSF) for kiosks under ransomware threat conditions. RSF integrates three defensive layers: (1) prevention through application allow-listing, secure boot, and Zero Trust (ZT) segmentation, (2) detection via artificial intelligence (AI) driven anomaly monitoring of system and transaction telemetry, and (3) response employing secure rollback, blockchain-backed forensic logging, and remote wipe capabilities. A synthetic testbed emulating 500 kiosks over a 72-h continuous simulation under ransomware campaigns representing WannaCry, Ryuk, and Conti variants demonstrates the RSF’s effectiveness. Compared with a baseline antivirus-only configuration, the RSF reduced mean time to detection (MTTD) by 41% (from 52 to 31 min), mean time to recovery (MTTR) by 53% (from 120 to 56 min), and downtime-related operational losses by 37% over the three-day experiment window. These findings validate the RSF’s ability to enhance resilience and recovery speed in large kiosk deployments while maintaining compliance with regulatory uptime requirements.Keywords

The twenty-first century has seen ransomware emerge as the leading cybersecurity threat, which affects organizations worldwide. During the early 2010s, CryptoLocker and other basic variants of ransomware demanded small payments from users to obtain their decryption keys. Ransomware evolved into a sophisticated professional network during the following decade because affiliates joined forces with ransomware as a service (RaaS) operators to create attacks that disabled hospitals and municipalities and entire business sectors [1]. The attacks on Colonial Pipeline, José Batista Sobrinho (JBS) Foods, and the Irish Health Service revealed how vulnerable essential infrastructure is and proved that ransomware has evolved into a threat that requires national security attention [2].

The list of targets includes lottery and betting kiosks, which serve as self-service devices found in retail stores, convenience shops, and casinos. The kiosks function as financial IoT devices because they perform user authentication and execute critical financial operations while handling large cash amounts and producing regulated output products, which include lottery and betting tickets. The annual revenue from national and state lotteries exceeds $100 billion, which passes through kiosk networks. The modern business world depends on kiosk systems for operations, yet these systems remain vulnerable to insufficient cybersecurity measures.

The majority of kiosks run outdated operating systems, which include Windows 7 and embedded Linux distributions that only get occasional software updates. The system fails to provide adequate physical access protection, which allows unauthorized personnel, including both internal staff members and harmful technical personnel, to connect external devices. The current network security measures consist of basic protection systems that use perimeter firewalls together with basic virtual private network (VPN) connections. The protection offered by traditional endpoint antivirus solutions against modern ransomware attacks has become insufficient because these threats use fileless execution and lateral movement and double extortion methods [3]. While ransomware defenses are well-studied for enterprise IT and healthcare, lottery/betting kiosks combine (i) unattended operation and physical exposure, (ii) legacy OS images and restricted maintenance windows, and (iii) financial/regulated workflows (ticketing, payments, printing). This combination changes attacker leverage (USB-borne local compromise; store-LAN worming) and alters design constraints for Zero Trust, anomaly detection, and recovery. Few works provide a kiosk-specific threat model, architecture, and end-to-end evaluation under realistic ransomware tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). This paper addresses that gap.

The research investigates the fundamental requirement for ransomware protection systems that operate on kiosk platforms. The proposed Resilient Security Framework (RSF) functions as a detection system that detects security threats in advance and enables instant system recovery. RSF operates differently from conventional approaches because it focuses on resilience instead of resistance by accepting kiosk ransomware attacks will happen, but kiosks should stay operational through containment measures and quick recovery procedures.

The contributions of this paper are threefold. The document provides a complete ransomware threat model that focuses on lottery and betting kiosks. The system uses a multi-layer RSF structure, which combines prevention, detection, and response capabilities for unattended retail devices. The third part of the study validates RSF through a big synthetic testbed, which shows that RSF outperforms baseline defenses by achieving better detection speed and recovery time and operational continuity.

RO1: Specify a kiosk-specific ransomware threat model using the MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK) framework and the Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of service, and Elevation of privilege (STRIDE) threat categories.

RO2: Design a Zero Trust-aligned Resilient Security Framework (RSF) tailored to unattended, regulated kiosk fleets.

RO3: Evaluate RSF in a 500-kiosk synthetic testbed with worm-style, human-operated, and double-extortion TTPs; quantify detection, recovery, and cost impact.

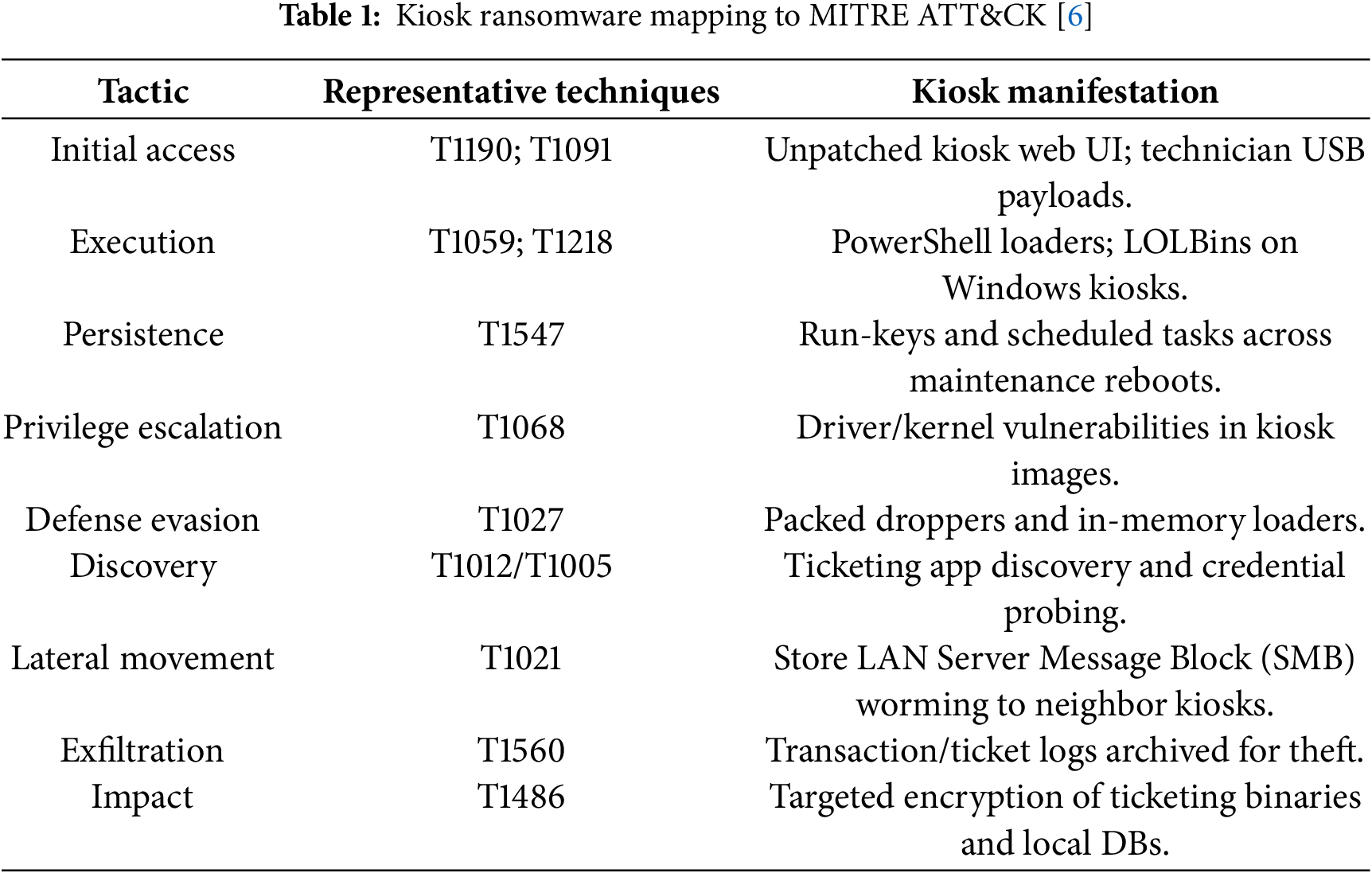

C1: Threat model for lottery/betting kiosks, mapping tactics → techniques → kiosk manifestations (Table 1).

C2: A three-layer RSF (prevention, detection, response) with a Policy Decision Point (PDP) and Policy Enforcement Point (PEP) policy plane and offline behaviors (Section 4).

C3: Implementation and evaluation on a 500-kiosk range with ATT&CK-mapped TTP scripts; improved MTTD/MTTR/downtime and regulator-facing explainability (Sections 5–7).

Section 2 reviews related work. Section 3 presents the threat model. Section 4 describes the RSF design. Section 5 details the implementation and dataset. Section 6 reports detection results; Section 7 presents ablations/overheads. Section 8 discusses implications; Section 9 adds extended related work. Section 10 covers limitations/future work, and Section 11 concludes.

2 Background and Related Work (Kiosks, Zero Trust, Ransomware)

Ransomware has developed from simple automated lockers into human-controlled multi-stage attacks that use data encryption to steal information while implementing tailored negotiation methods. The combination of large-scale dynamic analysis with behavior-driven systems enables researchers to detect tampering and destructive activities at a large scale [4], and file system self-healing mechanisms together with rollback functions minimize the resulting damage [5]. For unattended devices, the MITRE ATT&CK knowledge base offers a shared taxonomy for tactics and techniques across the intrusion lifecycle [6].

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-207 document establishes Zero Trust architecture through identity-based access control with ongoing evaluation and small network segmentation. The NIST SP 800 207A document, together with the NIST National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence (NCCoE) SP 1800-35 practice guide, provides distributed system organizations with suitable policy decisions and enforcement patterns [7–9]. The modern supply chain framework defined in the Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF) SP 800 218 and the Supply chain Levels for Software Artifacts (SLSA) requires provenance data and attestations and software bills of materials (SBOMs) to limit update path threats [10,11].

New delivery planes have emerged: browser-resident encryptors leveraging WebAssembly and the File System Access API have been demonstrated, which is relevant for kiosks embedding browsers for UX [12]. The economics of ransomware operate through professionalized markets that use affiliate models, which force defenders to reduce attacker leverage time and minimize blast radius for maximum protection [13]. The historical analysis of automated teller machine (ATM) and point of sale (POS) malware indicates that infections from removable media, driver level persistence, and the presence of outdated operating system images in unattended financial devices are possible [14].

3 Methods: Threat Model (ATT&CK and STRIDE)

The system consists of multiple kiosks with standard Windows 10/11 LTSC or embedded Linux operating systems, which operate on retailer local area networks (LANs) with network address translation (NAT) protection and scheduled VPN access to operator backend systems. Each device processes payments, prints tickets, stores transient logs, and supports remote management. The system faces restrictions because of its limited CPU and RAM resources, restricted maintenance access, and exposure to personnel and technicians, as well as varied Internet Service Provider (ISP) network conditions. With RaaS characteristics and financial motivation, the adversary adapts to defensive disclosures [13].

Table 1 aligns kiosk ransomware phases with MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques [6]. The first step of an attack usually happens through the exploitation of publicly accessible applications (T1190) or by using removable media for replication (T1091). Execution uses Command/Scripting Interpreter (T1059) or Signed Binary Proxy Execution (T1218). Persistence leverages Boot/Logon Autostart Execution (T1547). Discovery, lateral movement, exfiltration, and impact follow the enterprise matrix.

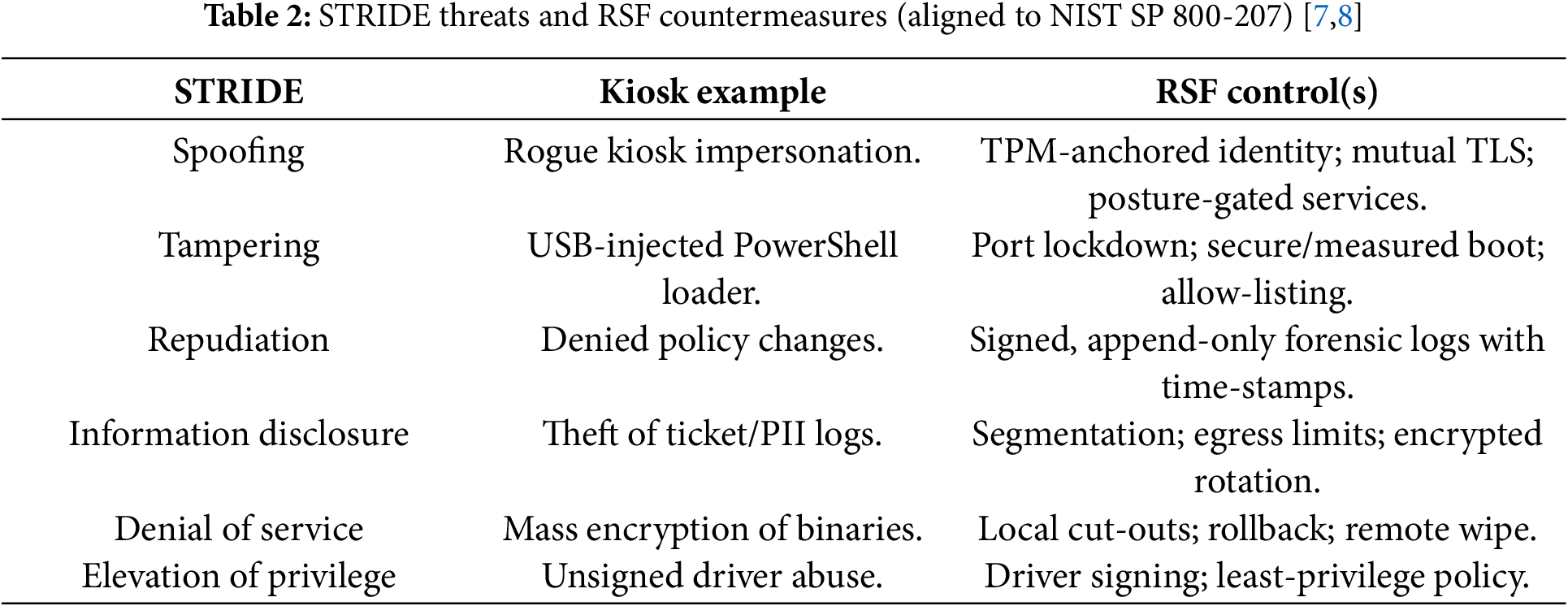

The following table presents STRIDE threats together with RSF controls, which correspond to NIST SP 800 207 [7,8] standards. The combination of TPM-anchored identity with mutual TLS protects against spoofing attacks. The system protects against tampering through Secure/Measured Boot and allows listing functionality. The system uses signed append-only logs for repudiation protection. The system protects against information disclosure through micro-segmentation and egress controls. The system defends against denial-of-service attacks through anomaly cutouts and snapshot rollback functionality. The system protects against elevation of privilege attacks through driver signing and least privilege access controls. This analysis uses Table 2 to map STRIDE threats to the RSF controls.

3.4 KillChain Overlay and Historical Analogs

The two primary attack methods consist of USB-assisted local compromise and stored LAN worming, yet RSF protects itself through identity/posture gates and micro-segmentation boundaries and anomaly cutouts and snapshot-based rollback and tamper-evident logging, which follows behavioral detection and recovery research [4,5]. The evaluation of ATM/POS systems through case studies shows that security needs both physical and logical defense systems [14].

Attacker goals & capabilities: Financially motivated RaaS affiliates seeking ransom and/or ticket/PII theft; access to commodity worm modules, LOLBins, and common privilege-escalation exploits.

Access levels: (i) Local USB access by a malicious/compromised technician; (ii) Store-LAN adjacency via SMB worming from an infected peer; (iii) Limited WAN presence to C2 via allowed egress.

Assumed baseline defenses: Perimeter firewalls/VPN; stock Defender with Controlled Folder Access OFF; no EDR on Linux; periodic image refresh.

Constraints: Unattended terminals, physical port exposure, intermittent WAN, strict uptime/UX requirements.

Success conditions: Encrypt ticketing binaries/local DBs; exfil transaction logs; lateral movement across store-LAN.

Defender success: Contain early, block east-west, roll back to immutable snapshots, and preserve tamper-evident logs.

4 Methods: Zero Trust RSF (Design)

4.1 Architecture and Policy Plane

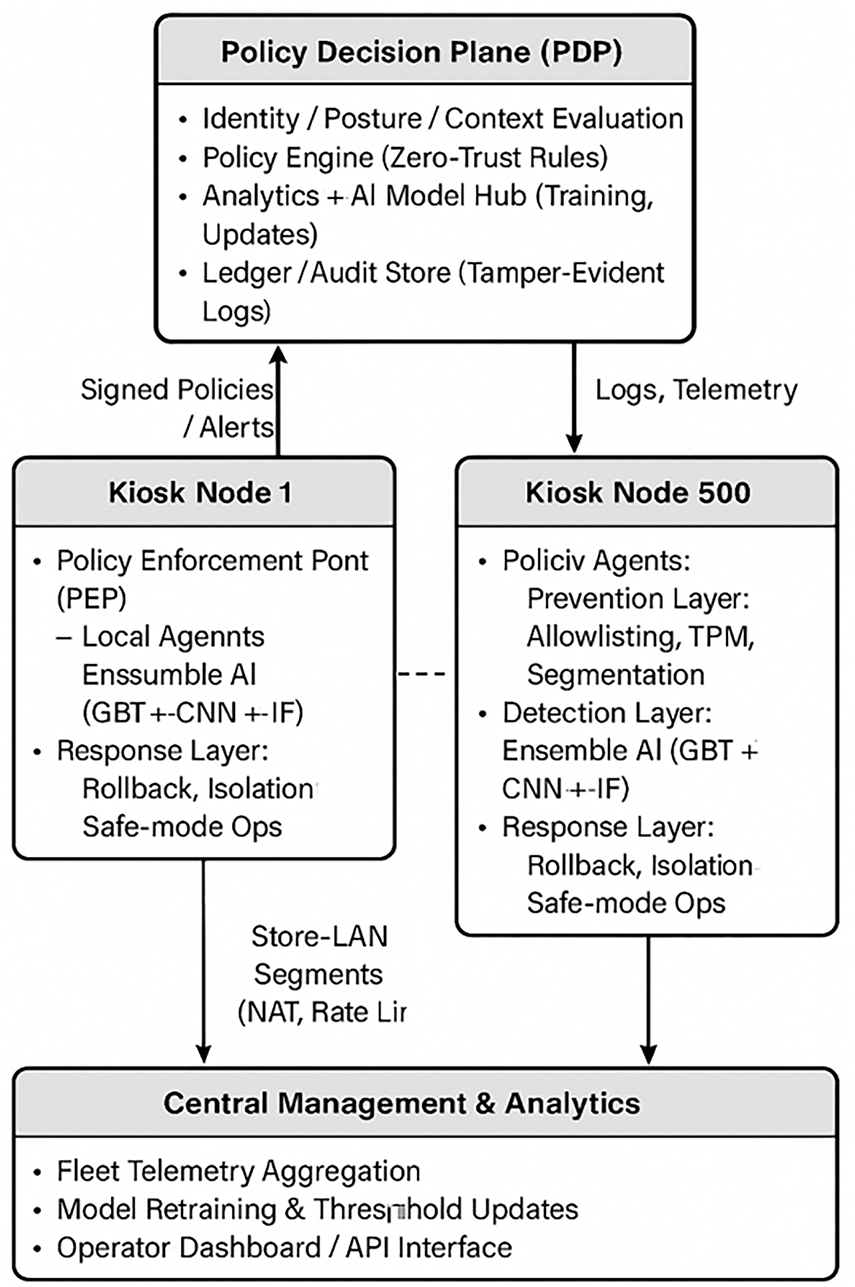

RSF implements Zero Trust according to SP 800 207 and the NCCoE SP 1800 35 practice guides, which uses a central Policy Decision Point (PDP) to assess identity, posture, behavior, and device Policy Enforcement Points (PEPs) to execute signed intents at the local level [7–9]. A VPN or physical location does not provide any assurance of trust. Fig. 1 shows the high-level architecture that supports this model.

Figure 1: RSF high-level architecture for kiosk ecosystem

RSF protects kiosks through a combination of Trusted Platform Module (TPM) based Measured Boot and device certificates and strict package signing and kernel driver verification and micro-segmentation that separates UI/payment/ticketing into named authenticated APIs and provenance-verified updates through SSDF SP 800 218 and SLSA attestations and SBOMs and roll safe bundles [10,11].

A small collection of low overhead features (rolling CPU variance, bounded file entropy deltas, syscall mix drift, small block write bursts, rename then write patterns, transaction latency dispersion, and printer back pressure) are used to train a compact ensemble (isolation forest + gradient boosted trees + 1D CNN). The ensemble system provides local containment features that enable feature streaming to support fleet-wide correlation operations. The research indicates that destructive behavior detection and quick recovery processes have been demonstrated in previous studies [3–5].

The autonomous containment system will freeze all nonessential services and block east-west trust when particular thresholds are reached. Organizations use the rollback/re-provision process to restore their environment to previous immutable snapshots while they work to rebuild their security defenses. Auditors gain full forensic capabilities through the combination of signed append-only logs with private ledger anchoring. Remote wipe functions as a solution to handle situations where an attacker achieves high-confidence compromise [7–9].

4.5 Concrete ZT Policies and PDP/PEP Offline Behavior

The PDP operates as a centralized system that maintains regional duplicate databases. PEPs operate as part of the device platform infrastructure. Sensitive API tokens have 30-min lifetimes. When the wide area network (WAN) connection fails, PEPs will apply the last known safe policy snapshot, but sensitive actions that need fresh authorization will fail closed, and kiosk functions that are essential will fail open with throttling and full logging. Certificate revocation information is cached with short time to live (TTL) values (≤24 h).

4.6 Exfiltration Controls and DLP for Double Extortion

RSF uses Domain Name System (DNS) and Server Name Indication (SNI) based IP egress allow lists as part of its security measures, which include lightweight archive heuristics (MIME and filename/size patterns) and token-bound cloud APIs and anomaly-triggered rate limiting for exfiltration phases. The privacy-preserving capabilities of data loss prevention (DLP) function through sampling-based checks, which examine restricted data portions before deleting them on the device [15,16]. RSF prepares for post quantum cryptography (PQC) requirements by aligning firmware signing and key management processes with NIST FIPS 203, FIPS 204, and FIPS 205 [17–19].

5 Methods: Implementation (Dataset, TTPs, Training, Baselines, Logging)

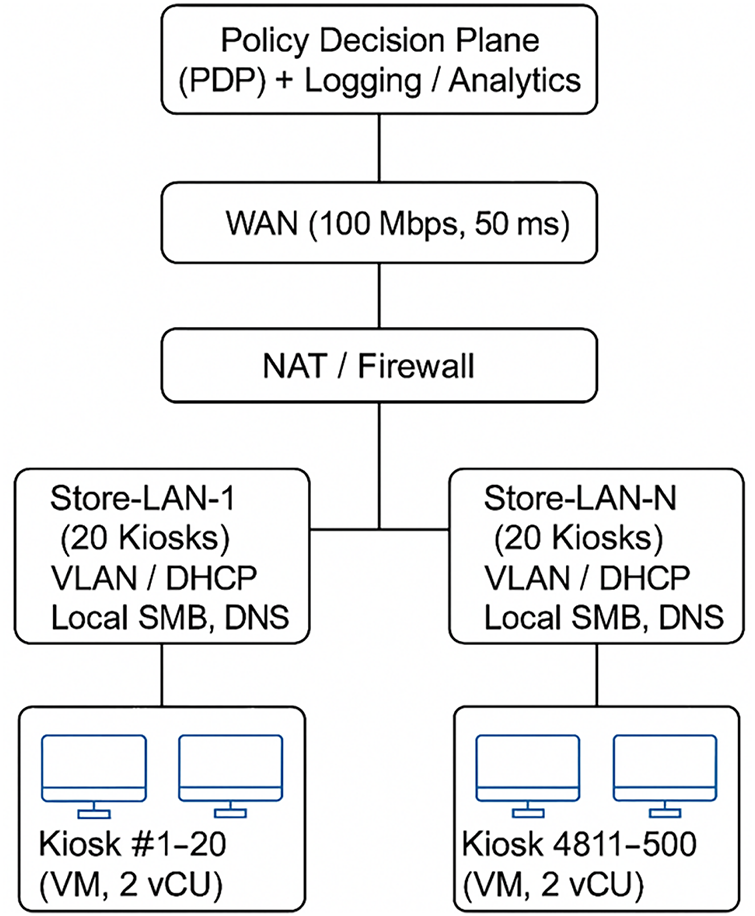

All experiments were conducted on a Dell PowerEdge R740 host equipped with dual Intel Xeon Silver 4314 central processing units (CPUs) (2.4 GHz, 32 cores), 256 gigabytes (GB) of random access memory (RAM), and 12 TB NVMe SSD storage, running VMware ESXi 8.0 as the hypervisor. Each kiosk virtual machine (VM) was provisioned with 2 vCPUs, 4 GB RAM, and 40 GB disk space. Windows kiosks ran Windows 10 LTSC 2021 (build 19044), while Linux kiosks used Ubuntu 22.04 LTS (kernel 5.15). A total of 500 VMs (60 percent Windows, 40 percent Linux) were cloned from two gold images that included the ticketing and payment software, printer drivers, and remote management agents.

The VMs were grouped into 25 store-LAN segments (20 kiosks each) behind simulated NAT gateways, all connected through a WAN to a central Policy Decision Plane (PDP) and logging backend (Fig. 2). Network parameters emulated retailer conditions with bandwidth between 50 and 100 Mbps, latency between 40 and 80 ms, and 1–2 percent random packet loss to evaluate RSF’s offline resilience (Section 4.5). Windows Defender was enabled with Cloud Protection ON and Controlled Folder Access OFF to mirror standard kiosk configurations.

Figure 2: Synthetic testbed network topology

Three ATT&CK-mapped ransomware profiles were implemented as behavioral emulations rather than live malware. The first, a worm-style SMB propagation profile (WannaCry-like), scanned 200 hosts per minute with a 0.7 success rate, targeted .exe, .db, and .csv files, and maintained an average dwell time of 10 min. The second, a human-operated profile (Ryuk-like), executed discovery commands at one per minute, performed privilege escalation through PowerShell and WMIC, and triggered staged encryption after 25 min. The third, a double-extortion profile (Conti-like), performed data exfiltration at 25 megabytes per minute via Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) and began encryption 40 min after exfiltration started with a compression ratio of 0.3.

These configurations provide a reproducible synthetic range for evaluating the RSF framework under realistic kiosk-scale ransomware conditions.

5.2 Cyber Range and TTP Scripting

We simulated 500 kiosks (60% Windows LTSC and 40% embedded Linux) with simulated retailer-like network conditions. The system operated authentication services and processed payments and printed tickets and managed periods of inactivity that followed regular daily routines. We implemented three attack profiles: Worm-style (WannaCry-like) SMB replication; human-operated (Ryuk-like) discovery, privilege escalation, and staged encryption; double extortion (Conti-like) staged exfiltration and then encryption. Scripts are mapped to ATT&CK tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and released as sanitized artifacts [3,4,6,12].

5.3 Dataset Generation, Seeds, and SafeLab Practices

Workloads used fixed seeds (seed_master = 2025; per device, seeds = seed_master + device_id). The transaction interarrival times followed a mixed Poisson process with peak times, while payment failures occurred at rates between 0.6% and 1.2%. All experiments were performed in air-gapped virtual networks without external connectivity or live credentials; no harmful binaries were released (only behavioral emulations and configs).

5.4 Model Training, Validation, and Thresholding (with Hyperparameters)

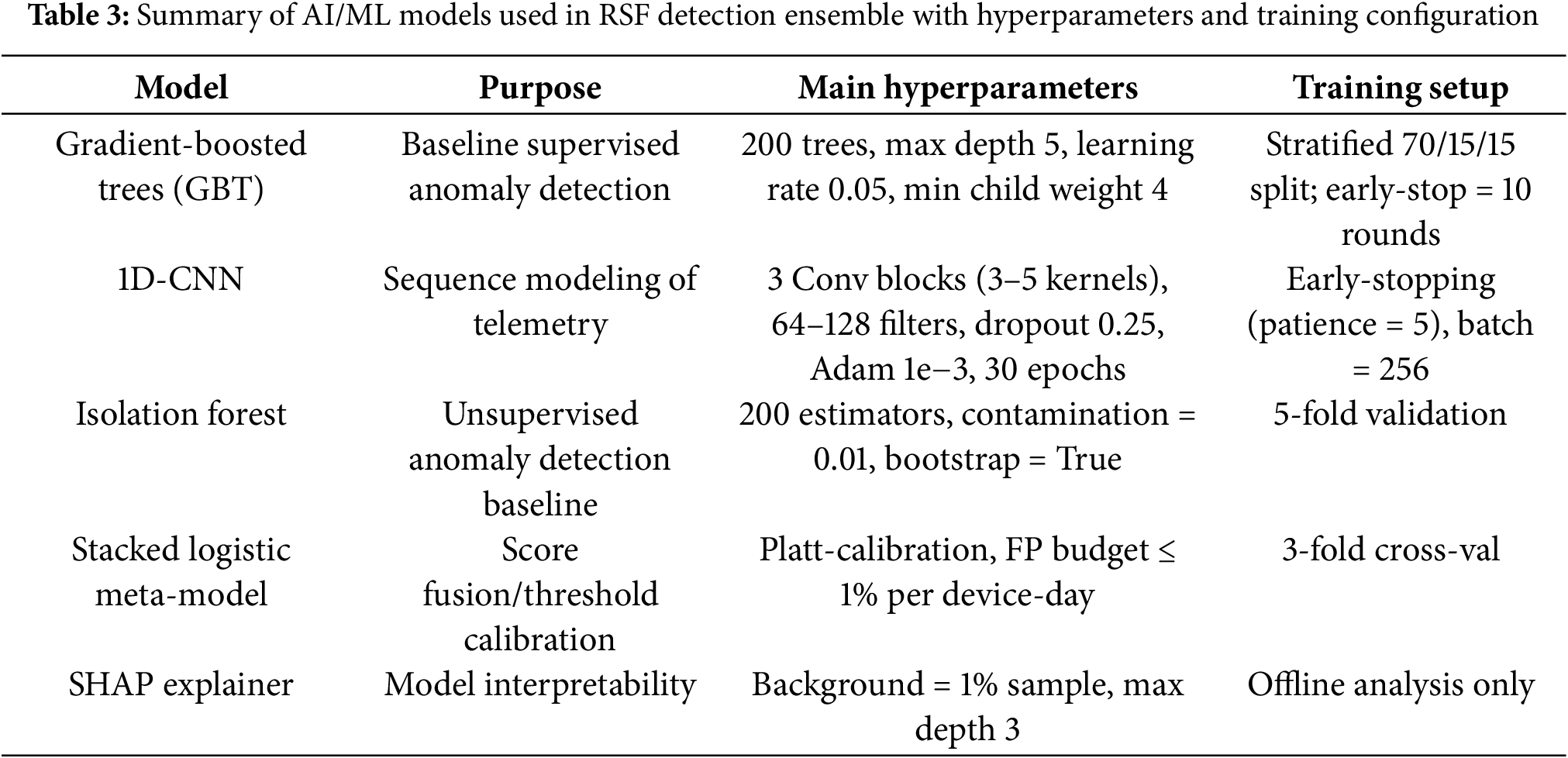

We used 60/20/20 device-level train/validation/test splits. The researchers achieved class balance through two methods: they reduced the number of benign windows in the dataset, and they used focal loss for CNNs. The model training, validation & thresholding process uses the configuration shown in Table 3. We used gradient boosted trees (GBT) and a one dimensional convolutional neural network (1D CNN) in the ensemble.

GBT: 200 trees, depth 5, learning rate 0.05, min child weight 4.

1D CNN: three conv blocks (kernels 3–5), 64–128 filters, dropout 0.25, Adam 1 × 10−3, 30 epochs with early stopping (patience 5).

The isolation forest model uses 200 estimators with 0.01 contamination and warm start windows for its operation.

The system used calibrated logistic stacking on validation scores to determine thresholds, which produced ≤1% false positive rates for each device day. SHAP analyses produced regulator-facing explanations mapping alerts to ATT&CK tactics.

The evaluation compared RSF to antivirus software and stock Windows Defender with cloud-based protection when Controlled Folder Access was disabled for standard kiosk environments. The artifact package contains Defender and endpoint detection and response (EDR) logs. Windows Defender engine version recorded in artifacts; OS build 22H2 KB50xxx; Cloud-delivered protection = ON; Controlled Folder Access = OFF; all other settings = defaults.

5.6 Logging Architecture: Signed Logs vs. Ledger Anchoring

We implemented Ed25519 signed append-only logs and optional private ledger anchoring (periodic hash commitments). The system stores event digests and metadata in logs while keeping PII information out of storage and implements dual control access for roles and minimizes data retention. Section 7 contains a micro benchmark that shows storage overhead and latency results.

6 Results: Detection Performance

6.1 Metrics and Statistical Validation

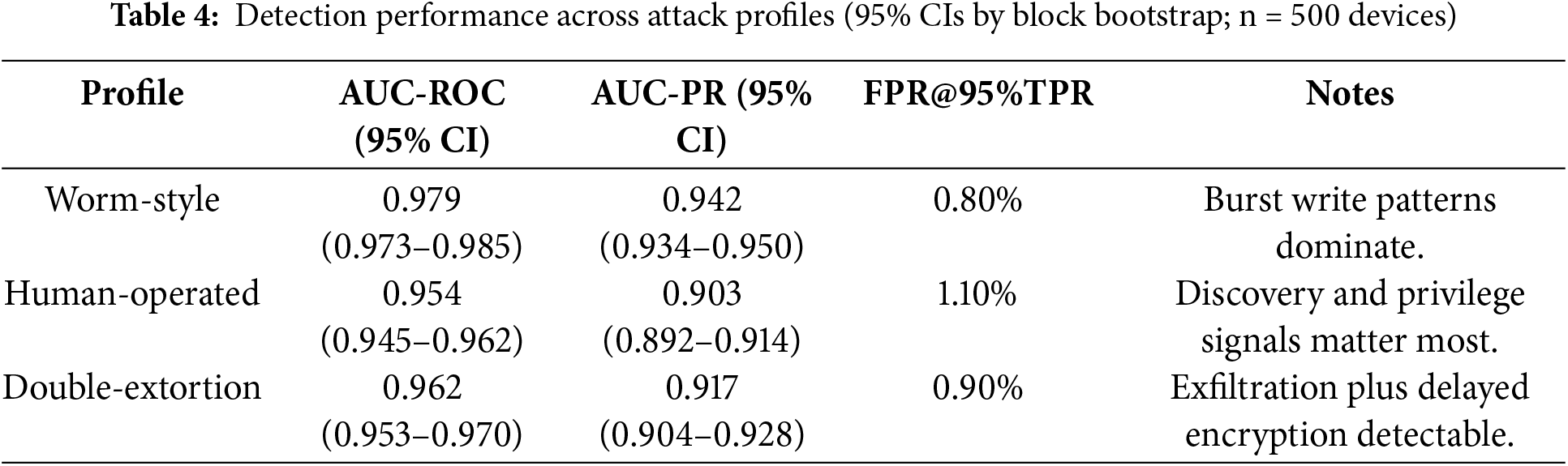

Primary metrics include MTTD, MTTR, per-kiosk downtime, data recovery rate, and AUC receiver operating characteristic and precision recall (AUC ROC and AUC PR) for detection. Confidence intervals were computed via a block bootstrap with block = device-day and B = 2000 resamples, as shown in Table 4.

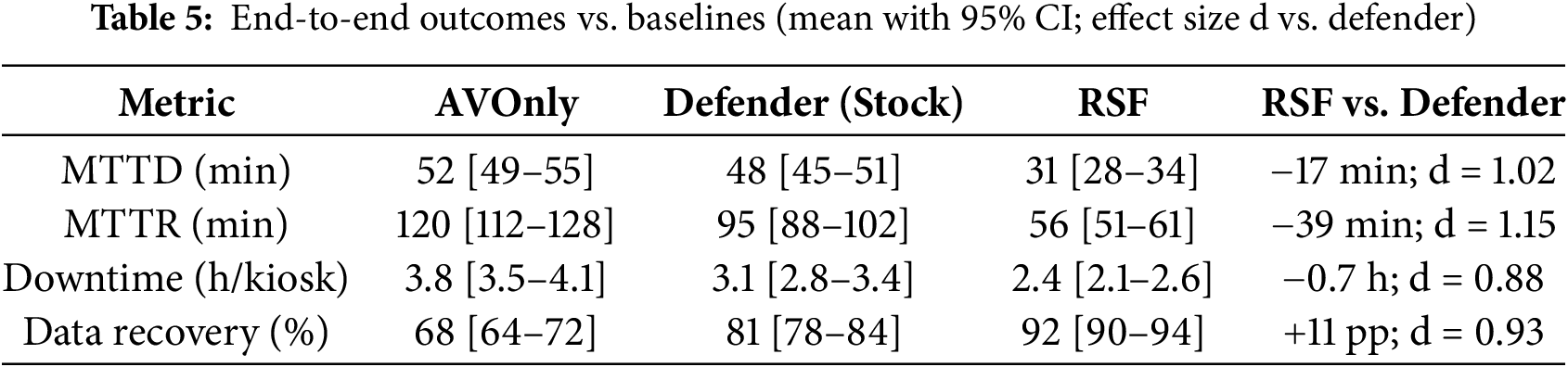

Compared to antivirus-only baselines, RSF achieved MTTD 31 vs. 52 min, MTTR 56 vs. 120 min, downtime 2.4 vs. 3.8 h, and data recovery 92% vs. 68% (See Table 5). These gains align with the resilience hypothesis: detection alone is insufficient without automated rollback and forensic closure to blunt extortion leverage.

6.3 Cost Sensitivity for National Operators

The cost of kiosk downtime reaches $500 for each operating hour when using high-traffic areas as the base. A 5000-kiosk fleet would experience $7.5M in lost revenue when an incident lasts three hours without RSF, but RSF enables the kiosks to operate for 1.9 h, which results in $4.7M in lost revenue and a total savings of $2.8M per incident. The total savings from expanding to 10,000 devices will grow at a rate of 1:1 because all devices have identical characteristics and equivalent risk elements.

7 Results: Ablations, Overheads, Alerts, and Logging Comparison

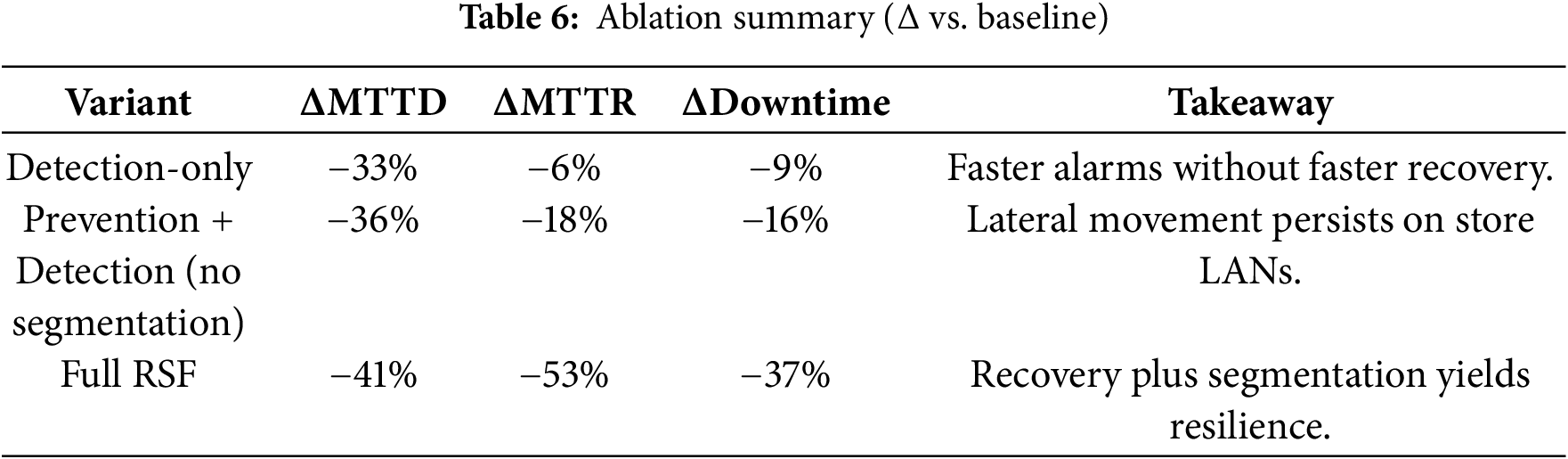

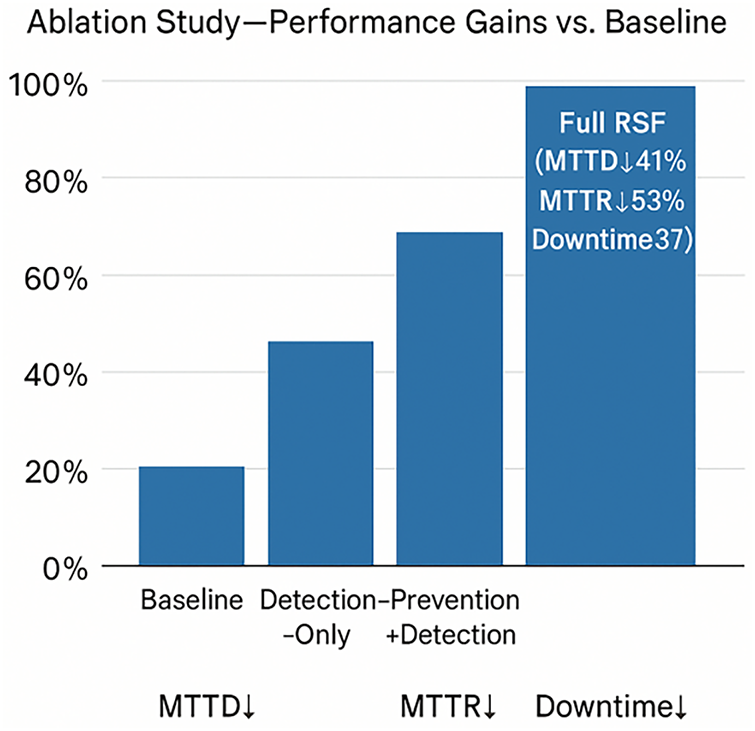

Ablation findings. The detection-only variant decreased MTTD by 33%, yet it maintained the same level of MTTR. The system achieved slightly improved results through Prevention + Detection, but it still allowed worm-style attacks to spread between store LANs. The full RSF produced the results presented in Table 6, which validated that automated recovery and east-west segmentation enhance resilience [3–5]. Fig. 3 shows the performance gains for each variant.

Figure 3: Ablation study-performance gains vs. baseline

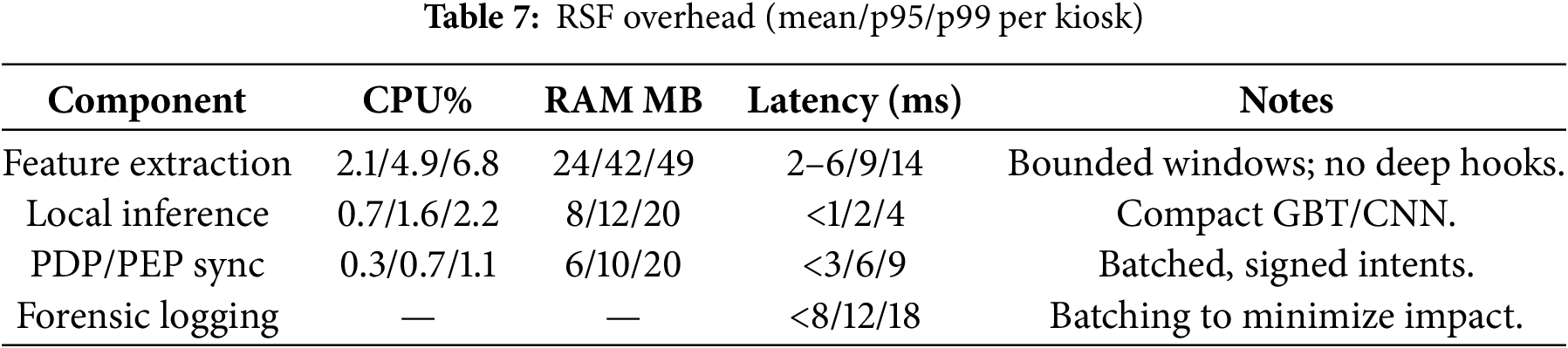

Overheads and latency distributions. Table 7 shows the mean, p95, and p99 overheads per kiosk. Bounded entropy windows together with deep hook avoidance mechanisms enable user-visible latency to stay within acceptable ranges [5]. Table 7 reports the overhead values for each component.

Alerts at fleet scale. With the ≤1% FP/device day target and confidence gating, the median alert rate was 0.8 per device day (p95 = 1.4). The system would generate approximately 4000 alarms per day for a 5000-kiosk fleet, but the implementation of correlation and suppression would lower this number to 900 alarms per day, which is a manageable workload for the security operations center (SOC).

Signed logs vs. ledger anchoring. The micro benchmark executed 1000 events during 10 runs, while signed append-only logs finished in 2.8 ± 0.6 ms and private ledger anchoring required 6.7 ± 1.1 ms to complete with equivalent storage growth. The use of Ledger anchoring provides third-party verification capabilities, which makes it suitable for cross-jurisdiction audits, but signed logs work for other cases. The two methods protect PII information and fulfill General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) Article 32 requirements and Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) v4.0 expectations [15,16].

Cost sensitivity. The loss of $500 per kiosk operating hour results in $7.5 million in revenue loss for a 5000-kiosk fleet during a three-hour event without RSF. The implementation of RSF reduces downtime to 1.9 h, which results in $4.7 million in lost revenue instead of $7.5 million and saves $2.8 million per incident. These dynamics align with observed ransomware market incentives [13].

8.1 Why Zero Trust for Kiosks?

RSF follows the SP 800-207 guidelines through its micro-segmentation strategy and continuous evaluation system, which works well for kiosk environments. The kiosk system performs authentication for all sensitive requests, and its blast radius remains limited because of its design structure. The 2023 modeling supplement presents kiosk subsystem archetypes (UI, payment, and ticketing) as independent protection zones that use centrally located policy decision points [8,9].

8.2 Operational Trade-Offs and Mitigation

The implementation of micro-segmentation technology generates fresh policy management obstacles that result in minimal system operational performance slowdowns. We mitigate with coarse-to-fine policies and telemetry-driven tuning. The implementation of blockchain logging requires payment because we perform batched write operations and payload compression and checkpointing to achieve end-to-end latency that remains under user-perceptible limits. Detection drift is addressed with periodic retraining and confidence-based gatekeeping to avoid alert storms.

8.3 Regulatory Alignment and Auditability

The three entities that require integrity and least privilege and evidence trails are gaming commissions, PCI-DSS assessors, and data protection authorities. The identity controls of RSF, along with segmentation and tamper-evident logs, provide auditors with ready-to-use artifacts. Organizations can achieve improved threat intelligence sharing between operators through standardized after-action reviews, which become possible by connecting incidents to ATT&CK pathways.

8.4 Limits and External Validity

Our cyber range duplicates retailer network structures but lacks full representation of all network configurations. Attack emulations implement behaviors based on literature, but they do not use proprietary TTPs that active crews employ. The detection/response improvements show strong consistency between worm- and human-operated and double-extortion attack profiles and follow the recommendations of I/O-aware detection guidance.

USENIX and NDSS have studied dynamic analysis methods as well as sandboxing at scale and evasion-resistant heuristic detection techniques. The UNVEIL [4] system revealed its ability to automatically detect harmful system activities, and researchers have since identified new attack methods, including browser-resident encryptors (RøB) [12], which require advanced monitoring techniques to detect.

9.2 Adversary Innovation and AI

Academic research shows that large language models (LLMs) enable offensive actions that simplify attacks and reduce the duration of attacker presence. The academic proof of concept “Ransomware 3.0” demonstrates autonomous ransomware operations that perform reconnaissance, payload generation, exfiltration, encryption, and ransom messaging [20]. A USENIX Security study shows LLM assisted backdoor attacks on code completion pipelines that evade strong detection [21]. Research also shows that LLM technology influences cybersecurity operations for detection, analysis, and offensive capabilities [22].

The research by Europol and Trend Micro demonstrates that Automated teller machines (ATMs) and point of sale (POS) terminals face similar security risks to kiosks because they experience long-term removable media infections and driver-level persistence and outdated operating system vulnerabilities [14]. The U.S. Secret Service has released public warnings about ATM jackpotting attacks, which demonstrate that attackers must physically access ATMs and extract removable hardware to perform malware deployment and steal cash [23]. The European Payments Council, through sector analyses, shows POS/ATM malware exists in payment threat trends, which requires kiosk environments to implement physical and logical controls (measured boot, driver signing, port lockdown, and segmentation) [24].

9.4 IoMT-Inspired Layered Security & IDS

Recent research in the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) domain offers transferable ideas for protecting safety-critical, resource-constrained devices through multi-layered security and intelligent intrusion detection. IoMT studies integrate deep-learning-based anomaly detection, dynamic key management, and blockchain-backed decentralized storage to enhance trust and tamper resistance. Representative frameworks such as the SA GBO ODBN blockchain and deep learning model for secure medical data handling and diagnosis [25], ensemble and meta learning based intrusion detection systems for IoMT environments [26], multi layered security assessments in mHealth platforms that span wearable, mobile, and backend components [27], and the Multi attention DeepCRNN explainable intrusion detection model for IoMT [28] demonstrate the benefits of deep ensembles, explainability, and layered protection.

The proposed RSF draws inspiration from these works by employing ensemble detection models for behavioral telemetry and ledger-anchored forensic logging to ensure auditability. Unlike medical devices, kiosks face strict user-experience latency and offline operation constraints; therefore, RSF adapts IoMT principles by decoupling model inference from policy enforcement and by compressing signed logs before periodic anchoring to the central ledger.

10 Limitations and Future Research

The cyber range duplicates retailer network structures, but it lacks the ability to replicate all network configurations and vendor systems. The TTPs reveal public actor activities, but they could be different from proprietary crew operations. The future work will focus on operator-based federated learning for secure model updates and explainable IDS artifacts to meet regulatory requirements and enhance kiosk/ATM/POS domain security and browser surface protection and PQC-ready code signing for firmware and update channels [7,12,15]. The organization will enhance external validity and PCI DSS and GDPR audit outcome measurement through field pilots, which will be conducted with national operators.

Our detection features and thresholds were tuned on a ticketing/payment workload and may not transfer unchanged to kiosks with different software stacks (e.g., media or wayfinding kiosks and airline common use self-service (CUSS) kiosks). Porting requires re-profiling benign telemetry, re-calibrating thresholds for ≤1% FP/device-day, and validating recovery semantics for application-specific data stores.

Kiosks operate outside the category of standard PCs and industrial controllers because they function as financial IoT endpoints that require both high public visibility and absolute operational reliability. The literature shows that adversaries continue to develop new methods while economic systems focus on fast operations, yet detection methods fall short of providing complete security. RSF implements Zero Trust for kiosks while maintaining detection systems that are both lightweight and effective and transforming response operations into a systematic and auditable process. The evaluation shows significant and statistically valid improvements in detection speed, recovery time, and data reliability, which result in multi-million-dollar savings from incidents at the national level. The outcome includes reduced infections together with diminished opportunities for extortion and shorter periods of disruption and enhanced trust in gaming systems that follow regulations.

Acknowledgement: We thank practitioners in the lottery and retail systems community for feedback on operational constraints and deployment realities.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article. The synthetic workload design, kiosk policy templates, ATT&CK-mapped TTP descriptions, model configurations, and evaluation results are fully presented in the Methods and Results sections. These materials can be reused for academic purposes with appropriate citation of this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Coveware. Quarterly ransomware report [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.coveware.com/. [Google Scholar]

2. Europol. Internet organised crime threat assessment (IOCTA) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.europol.europa.eu/. [Google Scholar]

3. Scaife N, Carter H, Traynor P, Butler KRB. CryptoLock (and drop itstopping ransomware attacks on user data. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 36th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS); 2016 Jun 27–30; Nara, Japan. p. 303–12. doi:10.1109/icdcs.2016.46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kharraz A, Arshad S, Mulliner C, Robertson W, Kirda E. UNVEIL: a large-scale, automated approach to detecting ransomware. In: Proceedings of the 25th USENIX Security Symposium; 2016 Aug 10–12; Austin, TX, USA. p. 757–72. [Google Scholar]

5. Continella A, Guagnelli A, Zingaro G, De Pasquale G, Barenghi A, Zanero S, et al. ShieldFS: a self-healing, ransomware-aware filesystem. In: Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Conference on Computer Security Applications; 2016 Dec 5–9; Los Angeles, CA, USA. p. 336–47. doi:10.1145/2991079.2991110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. MITRE ATT&CK. Enterprise tactics and techniques matrix [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://attack.mitre.org/. [Google Scholar]

7. Rose S, Borchert O, Mitchell S, Connelly S. Zero trust architecture (SP 800 207). Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); 2020. [Google Scholar]

8. Chandramouli R, Butcher Z. A zero trust architecture model for access control in cloud-native applications in multi-location environments (SP 800-207A). Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); 2023. [Google Scholar]

9. NIST NCCoE. Implementing a zero trust architecture (SP 1800 35). Gaithersburg, MD, USA: NIST NCCoE; 2025. [Google Scholar]

10. Souppaya M, Scarfone K, Dodson D. Secure software development framework (SSDF) version 1.1: recommendations for mitigating the risk of software vulnerabilities (SP 800 218). Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); 2022. [Google Scholar]

11. SLSA Project. Specification v1.0/1.2 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://slsa.dev/. [Google Scholar]

12. Öz H, Nikiforakis N, Invernizzi L, Vigna G, Kruegel C. RØB: ransomware over modern web browsers. In: Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium; 2023 Aug 9–11; Anaheim, CA, USA. p. 7073–90. [Google Scholar]

13. Oosthoek K, Cable J, Smaragdakis G. A tale of two markets: investigating the ransomware payments economy. Commun ACM. 2023;66(8):74–83. doi:10.1145/3582489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Europol and Trend Micro. Cashing in on ATM malware [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.europol.europa.eu/. [Google Scholar]

15. European Union. GDPR article 32 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/. [Google Scholar]

16. PCI Security Standards Council. PCI DSS v4.0 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/. [Google Scholar]

17. FIPS 203. Module-lattice-based key-encapsulation mechanism standard. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); 2024. [Google Scholar]

18. FIPS 204. Module-lattice-based digital signature standard. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); 2024. [Google Scholar]

19. FIPS 205. Stateless hash-based digital signature standard. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); 2024. [Google Scholar]

20. Raz M, Udeshi M, Charan PV, Krishnamurthy P, Khorrami F, Karri R. Ransomware 3.0: self-composing and LLM-orchestrated. arXiv:2508.20444. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2508.20444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yan S, Wang S, Duan Y, Hong H, Lee K, Kim D, et al. An LLM-assisted easy-to-trigger backdoor attack on code completion models: injecting disguised vulnerabilities against strong detection. In: Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Security Symposium; 2024 Aug 14–16; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 1795–812. [Google Scholar]

22. Xu H, Wang S, Li N, Wang K, Zhao Y, Chen K, et al. Large language models for cyber security: a systematic literature review. arXiv:2405.04760. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2405.04760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. United States Secret Service. ATM jackpotting advisory [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.secretservice.gov/. [Google Scholar]

24. European Payments Council. Payments threats and fraud trends report [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.europeanpaymentscouncil.eu/. [Google Scholar]

25. Sharma N, Shambharkar PG. Towards secure healthcare: SA-GBO-ODBN model utilizing Blockchain and deep learning for data handling and diagnosis. Comput J. 2025;68(10):1386–423. doi:10.1093/comjnl/bxaf045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alalhareth M, Hong SC. Enhancing the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) security with meta learning: a per-formance-driven approach for ensemble intrusion detection systems. Sensors. 2024;24(11):3519. doi:10.3390/s24113519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Timofte EM, Dimian M, Mangul S, Potorac AD, Gherman O, Balan D, et al. Multi layered security assess-ment in mHealth environments: case study on server, mobile and wearable components in the PHGL COVID platform. Appl Sci. 2025;15(15):8721. doi:10.3390/app15158721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sharma N, Shambharkar PG. Multi attention DeepCRNN: an efficient and explainable intrusion detection framework for Internet of Medical Things environments. Knowl Inf Syst. 2025;67(7):5783–849. doi:10.1007/s10115-025-02402-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools