Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Applications of Artificial Intelligence on Fetal Echocardiography

1 Department of Obstetrics, Paulista School of Medicine, Federal University of São Paulo (EPM-UNIFESP), São Paulo, 04021-001, SP, Brazil

2 Discipline of Woman Health, Municipal University of São Caetano do Sul (USCS), São Caetano do Sul, 09521-160, SP, Brazil

3 Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Cardiology, School of Medicine, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, 21941-901, RJ, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: Edward Araujo Júnior. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(3), 369-381. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.066358

Received 06 April 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 11 July 2025

Abstract

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital anomaly and a major cause of death among fetal malformations, but prenatal diagnosis is considered to be low. The development of artificial intelligence (AI) in fetal echocardiography has made it possible to automate and standardise the examination, improving the variation in CHD detection rates between different regions and reducing the reliance on operator experience. AI includes any computer program (algorithms and models) that mimics human logic and intelligence, and its use in fetal echocardiography is mainly to acquire and optimise images, perform automatic measurements, identify discrepant values, and diagnose and classify pathologies. In this review, we will look at the different practical applications of AI in fetal echocardiography.Keywords

Congenital heart diseases (CHD) are defined as any abnormality in the structure of the heart that occurs during embryonic development, generally within the first eight weeks of gestation. CHD are the most prevalent congenital defects and constitute a significant proportion of mortality rates due to congenital malformations. It is estimated that up to 20–30% of patients with CHD who do not receive adequate treatment die within the first month of life due to heart failure or hypoxemic crises, and approximately 50% die by the end of the first year of life [1]. Despite its clinical relevance, prenatal diagnosis of CHD is considered low yield, with 30–40% of cases remaining undetected before birth. Detection rates vary by geographical location, averaging around 50% [2]. The performance of prenatal ultrasound in detecting CHD can be influenced by several factors. These include the maternal body mass index, the presence of previous cesarean scars, and the fetal position [3].

In recent years, the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) in the field of fetal cardiac ultrasound has enabled the automated and standardized display of each diagnostic section of the fetal heart and accurate diagnosis, which should reduce reliance on the operator’s experience. Therefore, this would improve the disparity in CHD detection rates among different regions [4]. In this review, we will address the different applications of AI in fetal echocardiography.

For this narrative review, a search strategy was constructed to identify the studies focusing on the “practical application of artificial intelligence in fetal cardiac ultrasound imaging” published in English at PubMed from 2016 to 2024. One related manuscript was found in other academic site after screening their titles and abstracts. The Medical Subject Headings terms used were as follows: ‘Fetal echocardiography’ and ‘Artificial intelligence’; and ‘Congenital heart disease’. Case reports and duplicate studies those that no aimed the practical applications of AI in fetal echocardiography were excluded.

One of the earliest publications on Machine Learning (ML) dates back to 1959, in the article “Some Studies in Machine Learning Using the Game of Checkers” by Arthur Samuel, who coined the term “artificial intelligence” [5]. Since then, particularly from the 1980s onwards, the evolution of computational technology and the creation of advanced neural networks have led to rapid advancements in AI [6]. AI encompasses any computer program (algorithms and models) that mimics human logic and intelligence [7], primarily including ML, computer vision, and natural language processing [8].

ML is an important subset of AI that can learn from data, identify images, and make decisions. It involves programming a computer to store, learn, and analyze data by using statistical methods, which enables machines to improve with experience [6]. The applicability of the machine in echocardiography is evident in its capacity to accurately identify and classify anatomical structures in imaging modalities. For instance, the apparatus can accurately discern an image as a parasternal long-axis view from an apical long-axis view, thereby demonstrating its ability to discern different perspectives with precision [9]. ML is divided into several subdomains, one of which is deep learning (DL), which uses multilayer neural networks to solve problems [10]. DL is generally used in circumstances where a large amount of information needs to be processed [6]. Regarding its applicability in fetal echocardiography, DL models are trained to learn the key image features of the echocardiogram, to analyze images for measuring biometric parameters, to evaluate fetal growth and development, and to diagnose CHD [9]. We can, for instance, train a DL algorithm on a labeled set of echocardiogram images from patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and use the algorithm to predict this diagnosis in new images [6].

4 Applications of AI in Fetal Echocardiography

4.1 Acquisition, Optimization, and Quality Control of Images

Given the inherent difficulties of fetal echocardiographic examinations, such as complex cardiac anatomy, the small size of the patient, and fetal movement, capturing standardized views can be time-consuming and demanding [11,12]. In an effort to make this assessment increasingly efficient and reproducible, research on the application of AI in fetal echocardiograms has become more extensive, primarily focusing on image acquisition and optimization, automatic measurements, recognition of outlier values, disease diagnosis, and classification [4].

Among the studies on automatic image acquisition using AI, we have Garcia et al. [13], who applied the Spatiotemporal Image Correlation (STIC) technique in 207 normal fetuses, from which 150 volumes were selected for analysis using the Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE) method, and subsequently, visualization rates of fetal echocardiogram images were calculated using diagnostic planes and/or the Virtual Intelligent Sonographer Assistance (VIS-Assistance). The results demonstrated that the FINE method had a diagnostic value in routine fetal echocardiograms of 98 to 100%, suggesting that its use could be implemented in screening programs. This finding aligns with the recommendation proposed by Yeo et al. [14], after conducting a case-control study involving 50 fetuses with a broad spectrum of CHD and 100 normal fetuses, achieving a diagnostic performance with 98% sensitivity and 93% specificity using the FINE method. Their diagnoses were completely compatible with postnatal results in 74% of cases, with minor discrepancies in 12% of cases and greater discrepancies in 14% of cases.

This pattern had already been demonstrated by Yeo et al. [15], when applying the FINE method to 50 STIC volumes of normal fetal hearts and in four known CHD cases (aortic coarctation, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great arteries, and pulmonary atresia with intact interventricular septum), showing that it was possible to generate 9 images of the fetal echocardiogram in 78 to 100% of normal cases and that in all four cases, the method highlighted the presence of pathology. Their findings suggested that FINE could simplify fetal cardiac assessment and reduce the operator-dependent nature of the exam, as its application could increase the suspicion index of CHD and optimize screening. Such a suggestion was also found with the use of other methods, as demonstrated by Baumgartner et al. [16] who proposed a SonoNet and used a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to automatically detect standardized cuts from ultrasound video files of approximately 1000 fetuses. Although more challenging than biometric ultrasound images, the authors achieved an overall accuracy of 82.12% in capturing cardiac images, reaching an accuracy of 95% in the four-chamber view, 81.0% in the three vessels and trachea view, 73.08% in the right ventricular outflow tract view, and 78.50% in the left ventricular outflow tract view.

Focusing on the application of AI for classification, Abdi et al. [17] developed a CNN and trained it to qualitatively classify 6916 apical four-chamber view images, comparing this evaluation with scores given manually by an experienced cardiologist. They found the mean absolute error of the scores between the developed model and the specialist’s scores to be 0.71 ± 0.58, presenting a reported error comparable to intra-rater reliability and demonstrating that, with visually interpretable results and the ability to map anatomy to heart anatomy on the echo, there is reliability in this training model. A similar behavior was observed by Abdi et al. [18], who proposed a DL model based on a regression neural network that automatically distinguished the five standard cuts of fetal echocardiography and correlated them with corresponding quality scores given by cardiologists. A total of 2450 fetal echocardiograms were evaluated, and the proposed model achieved an image quality assessment accuracy of 85% compared to the specialists’ evaluations, with this performance similarly distributed across all views, resulting in an error rate close to zero and evenly distributed.

4.2 Intelligent Automatic Measurement in Fetal Echocardiography, Image Segmentation, and Identification of CHD

AI can also be used to assist in evaluating cardiac function, as exemplified by Yu et al. [19] in their study, where they sought to more accurately and effectively predict left ventricular volume, proposing a low-pressure volume measurement method in a single plane in two-dimensional ultrasound based on a reverse neural network that performed this calculation. Echocardiograms were conducted on 50 pregnant women between 20 and 28 weeks of gestation, where the method proposed by the authors achieved the highest intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC = 0.9691; 95% CI: 0.9663–0.9717) and the highest concordance correlation coefficient (CCC = 0.9401; 95% CI: 0.9348–0.9449). Furthermore, they also demonstrated that the left ventricular function parameters obtained by this model had better consistency compared to data obtained through four-dimensional ultrasound.

Improving AI’s ability to detect CHD during the prenatal period is an ongoing research goal [4]. Komatsu et al. [20] evaluated 363 fetal echocardiograms with a new model of Supervised Object Detection with Normal Data Only (SONO), utilizing a CNN to detect abnormalities in the fetal cardiac structures and substructures present in four-chamber and three vessels’ views in the videos captured during each examination. The areas under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for the heart and blood vessels were 0.787 and 0.891, respectively. Thus, they demonstrated that the automatic detection of key structures in an echocardiogram is feasible and suitable for detecting fetal cardiac structural alterations. Similarly, Xu et al. [21] developed a cascading CNN for their study named DW-Net, proposing to anatomically segment multiple structures of the early fetal echocardiogram’s four-chamber view automatically and with good accuracy. For this, they defined the anatomical structures that contain diagnostic indicators related to CHD, such as the cardiac chambers, the epicardium, the descending aorta, and the thorax; and from this, they evaluated four-chamber view images of 895 fetuses, identifying better performance of the proposed model compared to other conventional image segmentation methods, achieving a Dice coefficient of 0.827, pixel accuracy of 0.933, and area under the ROC curve of 0.990. They thus demonstrated the potential application of this tool for more effective prenatal diagnoses of CHD.

Investigating another method, Arnaout et al. [22] evaluated whether DL could also improve the detection of CHD. To this end, they implemented a CNN to automatically identify five standard views (three vessels and trachea, three vessels, left ventricular outflow tract, four-chamber, and fetal abdomen) and classify them between normal and CHD. In their study, they used 107,823 images from 1326 ultrasound examinations (including both fetal echocardiograms and routine exams), and the DL model used showed 98% sensitivity (95% CI, 47–100%) and 90% specificity (95% CI, 73–98%). Results compared to those achieved manually by doctors (sensitivity 86%, with 95% CI, 82–90%; and specificity 68%, with 95% CI, 64–72%) demonstrated equivalence in sensitivity (p = 0.3) and superiority in specificity (p = 0.04). Complementarily, Truong et al. [23] conducted fetal echocardiograms in a population of 3910 singleton pregnancies at 22 weeks, utilizing ML through a Random Forest (RF) algorithm that provided 85% sensitivity, 88% specificity, 55% positive predictive value, 97% negative predictive value, and an average ROC mean of 0.94. Such findings suggest an increase in sensitivity and a good performance of the ML application in prenatal screening. Table 1 summarizes the studies on the application of AI in Fetal Echocardiography. Table 2 illustrates the statistical methods used by the studies to provide sensitivity, specificity and predictive values.

Table 1: Main reviewed studies on the application of artificial intelligence in fetal echocardiography.

| Study | Objective | Technology | Sample | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garcia et al. [13] | Image acquisition | FINE, VIS-Assistance, 4DUS | 150 volumes | Diagnostic value 98–100% | Not focus on CHD |

| Yeo et al. [14] | Image acquisition and diagnosis | FINE, VIS-Assistance, 4DUS | 50 CHD 100 normal | Sensitivity 98%, Specificity 93% | Only a single STIC volume per fetus with CHD was examined |

| Yeo et al. [15] | Classification | FINE, VIS-Assistance, 4DUS | 50 normal fetuses, 4 CHD | Generates 9 fetal echo images in 78–100% of normal cases and highlights existing pathologies | Small sample size of fetuses with CHD |

| Baumgartner et al. [16] | Image acquisition and detection | CNN | ±1000 fetuses | ±1000 fetuses | CNN: Image detection does not consider pixel intensity |

| Abdi et al. [17] | Classification | CNN | 6916 images | Mean absolute error 0.71 ± 0.58 | Limited to end-systolic frames instead of sequential echo images |

| Abdi et al. [18] | Classification | DL | 2450 fetal echocardiograms | Accuracy of 85% compared to specialists | Non-uniform distribution of samples for each view |

| Yu et al. [19] | Left ventricular volume | Reversed neural network, 2DUS | 50 pregnant women | ICC 0.97, CCC 0.94 | Small number of datasets |

| Komatsu et al. [20] | Image segmentation | CNN | 363 fetal echocardiograms | ROC for the heart 0.787, ROC for blood vessels 0.891 | Small data of CHD, one type of sonography machine, mainly apical view data |

| Xu et al. [21] | Image segmentation | CNN | 895 fetuses | Dice 0.827, Pixel accuracy 0.933, ROC 0.990 | |

| Arnaout et al. [22] | CHD detection | DL | 107,833 images | Sensitivity 98%, Specificity 90% | Small data of some types of CHD |

| Truong et al. [23] | CHD detection | ML | 3910 pregnancies | Sensitivity 85%, Specificity 88% PPV 55%, NPV 97% ROC 0.94 | Sensitivity < Specificity |

Table 2: The statistical metrics used by the main studies for the assessment of their results.

| Study | Objective | Metrics Used on the Evaluation of Sensitivity/Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Yeo et al. [14] | Image acquisition and diagnosis | Randomized study, positive and negative likelihood ratios were determined |

| Yu et al. [19] | Left ventricular volume | Bland-Altman for intraclass correlation and concordance correlation coefficients |

| Komatsu et al. [20] | Image segmentation | Nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney U test), Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, ROC curves |

| Xu et al. [21] | Image segmentation | ROC analysis |

| Arnaout et al. [22] | CHD detection | Area under the curve (AUC), confidence interval |

| Truong et al. [23] | CHD detection | ROC analysis, ROC curves |

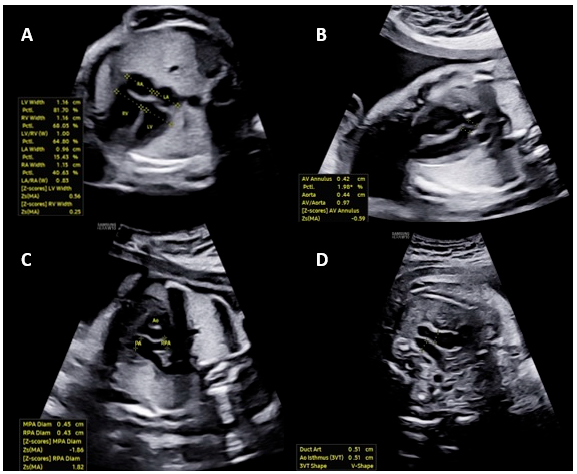

With technological advancements, automatic methods based on AI have been developed to optimize daily practice in Fetal Medicine by improving the accuracy and reproducibility of fetal cardiac measurements. The HeartAssist® technology (Samsung Healthcare, Gangwon-do, South Korea) operates by capturing detailed real-time ultrasound images of the fetal heart. Utilizing advanced algorithms, the system analyzes these images, identifying essential cardiac structures such as the ventricular chambers, interventricular septum, and cardiac valves. Based on these identifications, HeartAssist® automatically calculates crucial biometric measurements, such as the diameter of the aorta, the thickness of the interventricular septum (IVS), and the diameter of the left ventricle [3] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The images illustrate automated measurements of fetal heart parameters by HeartAssist®: (A) Width of the atria and ventricles in the four-chamber view; (B) Ascending aorta diameter in the left ventricular outflow tract view; (C) Diameter of the pulmonary artery in the right ventricular outflow tract view; (D) Diameter of the ductus arteriosus and aortic isthmus in the three vessels and trachea view.

Pietrolucci et al. [3] evaluated the agreement between visual and automatic methods in assessing the adequacy of fetal cardiac images obtained during second-trimester scans. Views of the left and right outflow tracts of the four-chamber, along with three vessels and the trachea view, were obtained from 120 consecutive low-risk singleton pregnancies undergoing second-trimester ultrasound between 19 and 23 weeks. For each view, quality assessment was performed by a specialist sonographer and by an AI software (HeartAssist®). Cohen’s κ coefficient was used to assess the agreement rates between the two techniques. The number and percentage of images deemed visually adequate by the specialist or with HeartAssist® were similar, with a percentage >87% for all considered cardiac views. The Cohen’s κ coefficient values were 0.827 (95% CI, 0.662–0.992) for the four-chamber view, 0.814 (95% CI, 0.638–0.990) for the left ventricle outflow tract, and 0.838 (95% CI, 0.683–0.992) for the three vessels and trachea, indicating good agreement between the two techniques. The authors concluded that HeartAssist® enabled automatic visualization of fetal cardiac structures, achieved the same accuracy as specialized visual assessment, and has the potential to be applied in evaluating the fetal heart during ultrasound screening for CHD in the second trimester of pregnancy.

The FetalHQ® technology (Voluson E10, General Electric Healthcare, Zipf, Austria) allows for a rapid and comprehensive assessment of the fetal heart regarding its size, shape, and contractility. It is a technology based on speckle-tracking, capable of evaluating the Global Sphericity Index (GSI) of the heart, dividing the left and right ventricles into 24 segments, and performing automatic measurements simultaneously. Growing studies have demonstrated the potential of FetalHQ® in assessing fetal cardiac morphology and functional changes in pregnant women with anemia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, and fetal growth restriction [24].

The goal of Scharf’s et al. [25] study was to demonstrate whether less experienced operators could handle an automated tool and whether it would be feasible for them to benefit from it. Thus, the authors conducted a prospective study involving a total of 136 normal fetuses in the second and third trimesters without CHD and with normal heart rates, where all women were routinely investigated by applying FetalHQ®. The cine-loop sequences used were acquired and subsequently analyzed offline by a novice operator and an expert operator. Among both operators, the results demonstrated excellent agreement for cardiac morphometry parameters (ventricular size and shape) and good agreement for cardiac function parameters (EndoGLS and FS—ventricular contractility). Thus, it is suggested that once the inherent obstacles of inexperience are overcome, the analysis method using FetalHQ® can be learned efficiently and executed with a high level of expertise.

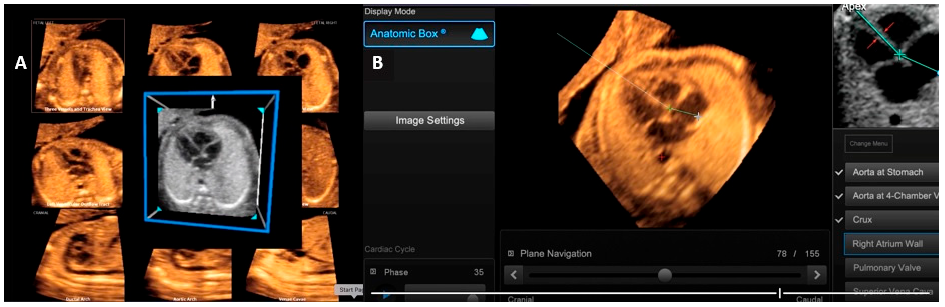

4.5 Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE)

FINE technology performs the automatic reconstruction of all 9 standardized planes during the execution of a fetal echocardiogram. Thus, these 9 planes of fetal heart images are automatically generated from a sequence of images (=cardiac volumes) of the fetal heart acquired in the four-chamber view of the fetal heart [15]. Through intelligent navigation, this software guides the examiner to mark seven points (descending aorta, crux cordis, pulmonary valve, superior vena cava, and transverse aorta). Sequentially, the 9 fetal echocardiographic views are automatically reproduced, and the software itself labels the views. It is possible to zoom in on each view separately and enhance the image using the ‘brightness’ and ‘contrast’ buttons. Thus, by applying the technology of ‘fetal intelligent navigation’ (FINE, known as ‘5D heart’) to sets of cardiac volumes that are a sequence of images obtained by STIC, the examination of the fetal heart can be simplified with less dependence on the operator [24].

Color Doppler can be added to FINE, enabling a better assessment of Doppler flow characteristics in cardiac vessels with greater accuracy in detecting CHD using this technology [25]. Carrilho et al. [26], in a prospective cross-sectional study, concluded that the quality of the echocardiographic views obtained with the FINE technique was superior to other technologies, such as the STAR (simple targeted arterial rendering) technique and the ‘four-chamber view swing’ (FAST) technique.

The advent of AI has led to the integration of this technology into ‘5D-heart’, resulting in the capacity to generate alerts for potential cardiac malformations, in addition to the automated measurement of anatomical structures and cardiac flows employing FINE technology. The integration of artificial intelligence within this tool constitutes a promising technological innovation, with the potential to alert non-specialist professionals to suspected cases of CHD, whilst concurrently reducing inter-operator variations in cardiac structure measurements. In conclusion, the automatic reconstruction of fetal echocardiographic planes by the FINE method reduces exam time, reduces differences between images obtained by different operators, and allows for the transmission of these images online for re-evaluation and detailed analysis by fetal heart specialists [27]. This is an advanced fetal cardiac imaging technology with a positive impact on the prenatal detection of CHD and the proper planning of delivery in services with support from Cardiology and Pediatric Cardiac Surgery for fetuses with critical CHD conditions [11] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Fetal echocardiography imaging using the FINE (Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography) method, also known as ‘5D heart’: this tool automatically reconstructs all 9 planes recommended during a fetal echocardiogram by acquiring a sequence of images (=cardiac volumes) of the fetal heart in the four-chamber view (A). After acquiring the cardiac volume in the four-chamber view, the software asks the operator to mark 7 points (descending aorta, crux cords, pulmonary valve and superior vena cava) to perform this reconstruction (B).

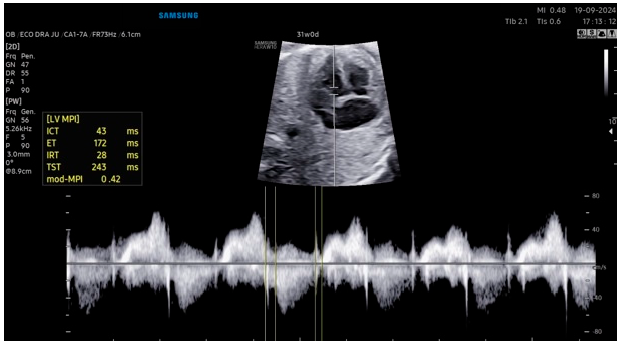

The Myocardial Performance Index (MPI) has been defined as a quantitative tool for the non-invasive assessment of the overall systolic and diastolic performance of the heart in adults and children and in cases of dilated cardiomyopathy [28]. MPI has been widely used in the literature to assess cardiac function in various pregnancy complications, including fetal growth restriction, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), congenital diaphragmatic hernia, fetuses of diabetic pregnant women and fetal inflammatory response syndrome [29]. MPI can be defined as the ratio between the duration of the isovolumetric contraction time (ICT) and isovolumetric relaxation time (IRT) and the duration of the ventricular ejection time (ET), represented by the formula MPI = (ICT + IRT)/ET. Abnormal cardiac function has been demonstrated to be associated with a prolongation of the ICT and a shortening of the ET, resulting in an increase in MPI [30].

Kim et al. [31] conducted a prospective study, including normal singleton pregnancies between 16 and 38 weeks of gestation to establish reference ranges for fetal right ventricular modified MPI using MPI+™. Two experienced operators measured the right ventricle modified MPI using the automated and manual methods. A total of 364 examinations from 272 fetuses were analyzed for developing the references ranges. The modified MPI and IRT time increased throughout the gestational weeks. The ICT increased until 24 weeks of gestation and then slightly decreased afterwards, and the ET also increased until 31 weeks of gestation and then decreased. The automated system demonstrated significantly higher intra- and inter-operator reproducibility of modified MPI in comparison of manual measurements (ICC = 0.962 vs. 0.913 and 0.961 vs. 0.889, respectively).

Scharf et al. [32] performed a prospective study involving 85 normal fetuses between 19 and 36 weeks of gestation and the modified right ventricle MPI was measured, both by a beginner and an expert using the MPI+™. The mean right ventricle modified MPI value of the beginner was 0.513 ± 0.09, and that of the expert was 0.501 ± 0.08. Between the beginner and the expert, the measured right ventricle modified MPI values indicated a similar distribution. The ICC was 0.624 (95% CI, 0.423 to 0.755) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Automated modified myocardial performance index measurement using the MPI+™.

4.7 Clinical Impact of Artificial Intelligence

The utilization of AI in the domain of fetal echocardiography holds considerable potential to enhance clinical practice, with a favorable impact on diagnostic accuracy and the timely implementation of interventions. This technological advancement also facilitates the provision of informed counsel to expectant parents and contributes to the effective planning of childbirth. The incorporation of AI technology has the potential to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of fetal heart ultrasound examinations. Specifically, AI-powered features such as automatic reconstruction of ultrasound planes through intelligent navigation with alerts for potential CHD and automated measurements can contribute to a reduction in examination time, an improvement in the quality of fetal heart ultrasound images acquired during fetal echocardiography or fetal heart ultrasound screening, and a minimization of interobserver measurement discrepancies.

4.8 Artificial Intelligence: Interdisciplinary Applications and Future Trends

AI’s ability to identify echocardiography image planes, recognize anatomical structures, and alert for congenital heart defects represents significant progress. This technology could improve workflows in prenatal diagnosis and cardiac malformation prognosis. In this context, Yeganegi et al. [33] conducted a review that demonstrated the effectiveness of various AI techniques in predicting neural tube defects and classifying associated genetic mutations. This study indicates that AI has the potential to serve as a promising tool for the early diagnosis of these malformations. Recent advancements in ultrasound and artificial intelligence technologies have resulted in the broadening of their applicability to a range of disciplines, encompassing domains such as pulmonary imaging, musculoskeletal imaging, and fetal brain imaging [34]. The potential of AI in the field of fetal genetics merits particular consideration. Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) has also benefited from advances in AI. AI algorithms can analyze cell-free fetal DNA in maternal blood to better detect chromosomal abnormalities [35,36]. The continuous advancement and widespread adoption of AI technology is set to transform medical services in the future. Key trends in this field are expected to include ultrasound, AI-powered teaching platforms, telemedicine, and intelligent health care systems [34,37,38].

Applications of AI to other technologies, including 3D ultrasound, fetal genomics and patient clinical data, has the potential to enhance diagnostic and therapeutic clinical practice. The exploration of future interdisciplinary research directions is a promising endeavor.

4.9 Limitations of Artificial Intelligence

Although AI reduces differences between observers, studies using reference ranges with automatic methods should be required. One example of this is the MPI, which is a widely used parameter for assessing fetal heart function. In addition, the examiner must be aware that AI-based diagnoses of heart defects can lead to false positives and false negatives. These must be confirmed by the examiner or by referral to experts in the field. Other drawbacks of AI in fetal echocardiography include the cost of equipment with these features, the learning curve associated with all advanced technologies, bias in data sets, and the need for continuous retraining as new parameters emerge that become possible to explore.

Research on AI in fetal echocardiography primarily focuses on image acquisition, image optimization, automatic measurement, and recognition of alterations to improve the diagnosis of cardiac diseases. Beyond image acquisition, image quality is critical for the accurate diagnosis of fetal CHD. Improving AI’s capacity to detect prenatal CHD is an ongoing research goal. Studies comparing manual and automatic AI methods have been demonstrating the importance of detecting CHD, as well as the need to continue advancing this technology, due to its potential as a routine diagnostic tool in this field. Prenatal diagnosis is increasingly relying on AI, whose algorithms are transforming how physicians use ultrasound in their daily workflow. Unlocking this potential will require closer collaboration between AI creators and the providers who use it, as the contours of health are complex, dynamic, and highly regulated.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Juliana Assis Alves; methodology, Mayra Martins Melo, Lorenza Machado Teixeira; validation, Juliana Assis Alves, Mayra Martins Melo, Lorenza Machado Teixeira; formal analysis, Juliana Assis Alves, Mayra Martins Melo, Lorenza Machado Teixeira, Nathalie Jeanne Bravo-Valenzuela; resources, Juliana Assis Alves, Mayra Martins Melo, Lorenza Machado Teixeira, Nathalie Jeanne Bravo-Valenzuela, Edward Araujo Júnior; writing—Nathalie Jeanne Bravo-Valenzuela, Edward Araujo Júnior; visualization, Juliana Assis Alves, Mayra Martins Melo, Lorenza Machado Teixeira, Nathalie Jeanne Bravo-Valenzuela, Edward Araujo Júnior; supervision, Edward Araujo Júnior; project administration, Edward Araujo Júnior. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. McCulley DJ, Black BL. Transcription factor pathways and congenital heart disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2012;100:253–77. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-387786-4.00008-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Carvalho JS, Axt-Fliedner R, Chaoui R, Copel JA, Cuneo BF, Goff D, et al. ISUOG practice guidelines (updated): fetal cardiac screening. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023;61(6):788–803. doi:10.1002/uog.26224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Pietrolucci ME, Maqina P, Mappa I, Marra MC, D’Antonio F, Rizzo G. Evaluation of an artificial intelligent algorithm (Heartassist™) to automatically assess the quality of second trimester cardiac views: a prospective study. J Perinat Med. 2023;51(7):920–4. doi:10.1515/jpm-2023-0052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ma M, Sun LH, Chen R, Zhu J, Zhao B. Artificial intelligence in fetal echocardiography: recent advances and future prospects. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2024;53:101380. doi:10.1016/j.ijcha.2024.101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Samuel AL. Some studies in machine learning using the game of checkers. IBM J. 1959;3:535–54. doi:10.1147/rd.33.0210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Davis A, Billick K, Horton K, Jankowski M, Knoll P, Marshall JE, et al. Artificial intelligence and echocardiography: a primer for cardiac sonographers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2020;33(9):1061–6. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2020.04.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. He J, Baxter SL, Xu J, Xu J, Zhou X, Zhang K. The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nat Med. 2019;25:30–6. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0307-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hashimoto DA, Rosman G, Rus D, Meireles OR. Artificial intelligence in surgery: promises and perils. Ann Surg. 2018;268(1):70–6. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Gandhi S, Mosleh W, Shen J, Chow CM. Automation, machine learning, and artificial intelligence in echocardiography: a brave new world. Echocardiography. 2018;35(9):1402–18. doi:10.1111/echo.14086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang J, Xiao S, Zhu Y, Zhang Z, Cao H, Xie M, et al. Advances in the application of artificial intelligence in fetal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024;37(5):550–61. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2023.12.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Magioli Bravo-Valenzuela NJ, Malho AS, Nieblas CO, Castro PT, Werner H, Araujo Júnior E. Evolution of fetal cardiac imaging over the last 20 years. Diagnostics. 2023;13(23):3509. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13233509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang A, Doan TT, Reddy C, Jone PN. Artificial intelligence in fetal and pediatric echocardiography. Children. 2024;12(1):14. doi:10.3390/children12010014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Garcia M, Yeo L, Romero R, Haggerty D, Giardina I, Hassan SS, et al. Prospective evaluation of the fetal heart using fetal intelligent navigation echocardiography (FINE). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(4):450–9. doi:10.1002/uog.15676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yeo L, Luewan S, Romero R. Fetal intelligent navigation echocardiography (FINE) detects 98% of congenital heart disease. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(11):2577–93. doi:10.1002/jum.14616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yeo L, Romero R. Fetal intelligent navigation echocardiography (FINE): a novel method for rapid, simple, and automatic examination of the fetal heart. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(3):268–84. doi:10.1002/uog.12563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Baumgartner CF, Kamnitsas K, Matthew J, Fletcher TP, Smith S, Koch LM, et al. SonoNet: real-time detection and localisation of fetal standard scan planes in freehand ultrasound. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2017;36(11):2204–15. doi:10.1109/TMI.2017.2712367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Abdi AH, Luong C, Tsang T, Allan G, Nouranian S, Jue J, et al. Automatic quality assessment of echocardiograms using convolutional neural networks: feasibility on the apical four-chamber view. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2017;36(6):1221–30. doi:10.1109/TMI.2017.2690836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Abdi AH, Luong C, Tsang T, Jue J, Gin K, Yeung D, et al. Quality assessment of echocardiographic cine using recurrent neural networks: feasibility on five standard view planes. In: Descoteaux M, Maier-Hein L, Franz A, Jannin P, Collins D, Duchesne S, editors. Medical image computing and computer assisted intervention—MICCAI 2017. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 11–3. Section 3, Lecture notes in computer science. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-66179-7_35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yu L, Guo Y, Wang Y, Yu J, Chen P. Determination of fetal left ventricular volume based on two-dimensional echocardiography. J Health Eng. 2017;2017:4797315. doi:10.1155/2017/4797315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Komatsu M, Sakai A, Komatsu R, Matsuoka R, Yasutomi S, Shozu K, et al. Detection of cardiac structural abnormalities in fetal ultrasound videos using deep learning. Appl Sci. 2021;11(1):371. doi:10.3390/app11010371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xu L, Liu M, Shen Z, Wang H, Liu X, Wang X, et al. DW-Net: a cascaded convolutional neural network for apical four-chamber view segmentation in fetal echocardiography. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2020;80:101690. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2019.101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Arnaout R, Curran L, Zhao Y, Levine JC, Chinn E, Moon-Grady AJ. An ensemble of neural networks provides expert-level prenatal detection of complex congenital heart disease. Nat Med. 2021;27(5):882–91. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01342-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Truong VT, Nguyen BP, Nguyen-Vo TH, Mazur W, Chung ES, Palmer C, et al. Application of machine learning in screening for congenital heart diseases using fetal echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;38(5):1007–15. doi:10.1007/s10554-022-02566-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang M, Kong Y, Huang B, Peng Y, Zhou C, Yan J, et al. Evaluation of the changes in cardiac morphology of fetuses with congenital heart disease using fetalHQ. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;36(2):2285239. doi:10.1080/14767058.2023.2285239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Scharf JL, Dracopoulos C, Gembicki M, Rody A, Welp A, Weichert J. How automated techniques ease functional assessment of the fetal heart: applicability of two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography for comprehensive analysis of global and segmental cardiac deformation using fetalHQ®. Echocardiography. 2024;41(6):e15833. doi:10.1111/echo.15833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Carrilho MC, Rolo LC, Tonni G, Araujo Júnior E. Assessment of the quality of fetal heart standard views using the FAST, STAR, and FINE four-dimensional ultrasound techniques in the screening of congenital heart diseases. Echocardiography. 2020;37(1):114–23. doi:10.1111/echo.14574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yeo L, Romero R. Color and power doppler combined with fetal intelligent navigation echocardiography (FINE) to evaluate the fetal heart. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(4):476–91. doi:10.1002/uog.17522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hernandez-Andrade E, López-Tenorio J, Figueroa-Diesel H, Sanin-Blair J, Carreras E, Cabero L, et al. A modified myocardial performance (Tei) index based on the use of valve clicks improves reproducibility of fetal left cardiac function assessment. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26(3):227–32. doi:10.1002/uog.1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lobmaier SM, Cruz-Lemini M, Valenzuela-Alcaraz B, Ortiz JU, Martinez JM, Gratacos E, et al. Influence of equipment and settings on myocardial performance index repeatability and definition of settings to achieve optimal reproducibility. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(6):632–9. doi:10.1002/uog.13365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Figueroa H, Silva MC, Kottmann C, Viguera S, Valenzuela I, Hernandez-Andrade E, et al. Fetal evaluation of the modified-myocardial performance index in pregnancies complicated by diabetes. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(10):943–8. doi:10.1002/pd.3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kim SY, Lee MY, Chung J, Park Y, Chung JH, Won HS, et al. Feasibility of automated measurement of fetal right ventricular modified myocardial performance index with development of reference values and clinical application. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):22433. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-74036-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Scharf JL, Dracopoulos C, Gembicki M, Welp A, Weichert J. How automated techniques ease functional assessment of the fetal heart: applicability of MPI+™ for direct quantification of the modified myocardial performance index. Diagnostics. 2023;13(10):1705. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13101705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Yeganegi M, Danaei M, Azizi S, Jayervand F, Bahrami R, Dastgheib SA, et al. Research advancements in the use of artificial intelligence for prenatal diagnosis of neural tube defects. Front Pediatr. 2025;13:1514447. doi:10.3389/fped.2025.1514447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yan L, Li Q, Fu K, Zhou X, Zhang K. Progress in the application of artificial intelligence in ultrasound-assisted medical diagnosis. Bioengineering. 2025;12(3):288. doi:10.3390/bioengineering12030288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Pierucci UM, Tonni G, Pelizzo G, Paraboschi I, Werner H, Ruano R. Artificial intelligence in fetal growth restriction management: a narrative review. J Clin Ultrasound. 2025;53(4):825–31. doi:10.1002/jcu.23918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Schwammenthal Y, Rabinowitz T, Basel-Salmon L, Tomashov-Matar R, Shomron N. Noninvasive fetal genotyping using deep neural networks. Brief Bioinform. 2024;26(1):bbaf067. doi:10.1093/bib/bbaf067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Patel DJ, Chaudhari K, Acharya N, Shrivastava D, Muneeba S. Artificial intelligence in obstetrics and gynecology: transforming care and outcomes. Cureus. 2024;16(7):e64725. doi:10.7759/cureus.64725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Maleki Varnosfaderani S, Forouzanfar M. The role of AI in hospitals and clinics: transforming healthcare in the 21st century. Bioengineering. 2024;11(4):337. doi:10.3390/bioengineering11040337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools