Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Long-Term Outcome of Adult Congenital Heart Disease Patients with Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators

1 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, 6-1 Kishibe-Shimmachi, Suita, 564-8565, Japan

2 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 113-8655, Japan

3 Department of Pediatric Cardiology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, 6-1 Kishibe-Shimmachi, Suita, 564-8565, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Kohei Ishibashi. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(3), 273-286. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.067716

Received 10 May 2025; Accepted 02 July 2025; Issue published 11 July 2025

Abstract

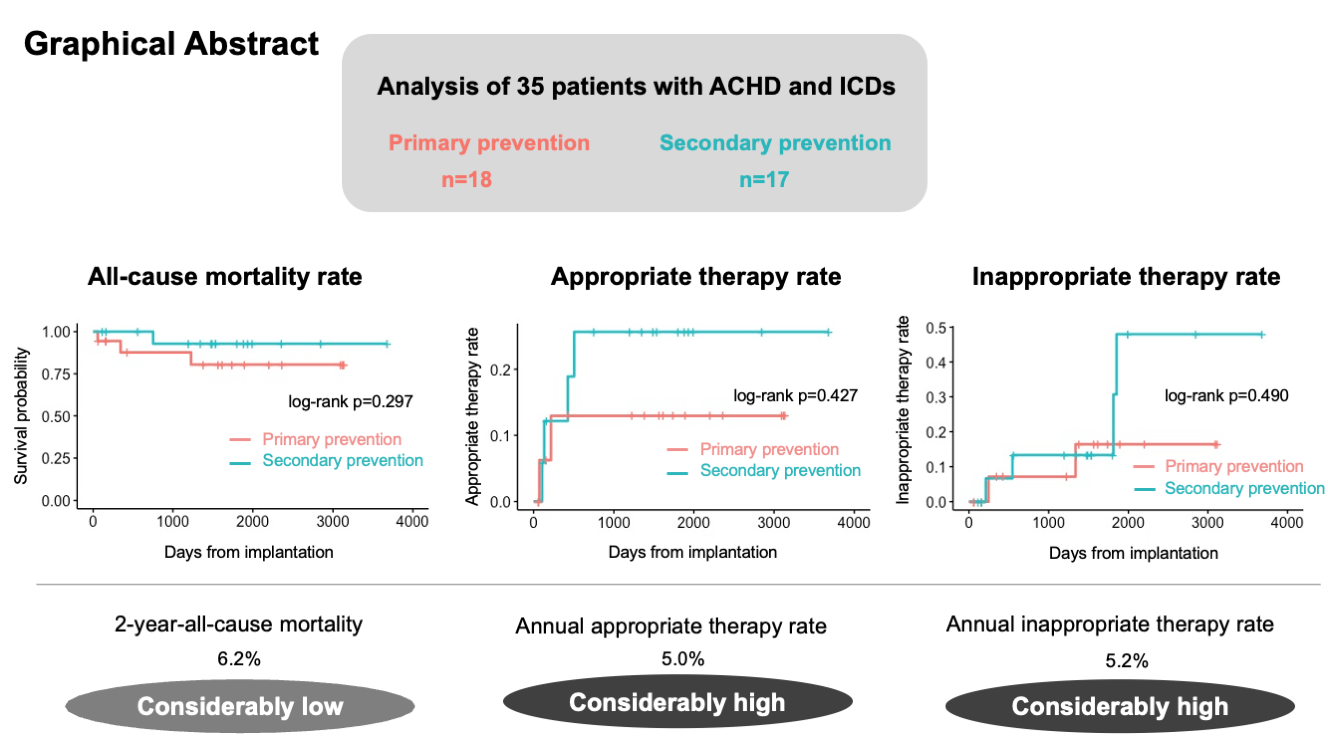

Background: Ventricular arrhythmia is a common cause of mortality in adult congenital heart disease (ACHD). The beneficial effects of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) in patients with ACHD have been demonstrated; however, evidence on this topic remains insufficient. This study aimed to assess the long-term outcomes after ICD implantation in the ACHD population. Methods: We retrospectively reviewed 35 consecutive patients with ACHD who underwent ICD implantation between December 2012 and August 2022. ICD implantation was classified as primary or secondary prevention. The long-term outcomes, including all-cause mortality, appropriate and inappropriate ICD therapy, and complications related to ICD implantation, were evaluated. Results: Among the 35 patients, 18 patients underwent ICD implantation for primary prevention. During a median follow-up period of 1484 days, 3 patients in the primary prevention group and 1 patient in the secondary prevention group died. The 2- and 5-year all-cause mortality rates were 6.2% and 13.6%, respectively. Two (11.1%) and 4 (23.5%) patients in the primary and secondary prevention groups, respectively, received appropriate therapy. Six patients (17%) were administered inappropriate therapy, and 2 patients (5.7%) experienced device-related complications. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed no significant differences in the all-cause mortality or the rates of appropriate and inappropriate therapy between the primary and secondary prevention groups (p = 0.297, p = 0.427, and p = 0.490, respectively). Conclusions: The incidence of appropriate ICD therapy in patients with ACHD was considerably high and comparable to that observed in patients with acquired heart disease, both in primary and secondary prevention. ICD implantation for primary prevention as well as for secondary prevention may be important in patients with ACHD.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileAs a result of medical, surgical, and interventional developments, the prognosis of congenital heart diseases has greatly improved over the past few decades [1]. Because patients with congenital heart diseases have become able to survive into adulthood, research has focused on their long-term mortality. Sudden cardiac death is a major cause of long-term mortality in the adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) population (9%–26%) [2,3,4]. Notably, ventricular arrhythmia is a common cause of sudden cardiac death in ACHD patients. Additionally, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) have been shown to have beneficial effects in ACHD patients as well as in patients with acquired heart disease [5]. Recent guidelines for the management of ventricular arrhythmia and the prevention of sudden cardiac death and for the management of ACHD established the indication for ICD implantation in ACHD patients [6,7]; however, evidence on this topic, especially regarding primary prevention, remains insufficient. This study aimed to assess the long-term outcomes after ICD implantation in the ACHD population, including primary and secondary prevention.

We retrospectively reviewed consecutive patients with ACHD who underwent ICD implantation (including pacemaker upgrade) at the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center (Osaka, Japan) between December 2012 and August 2022. The indications for ICD implantation were based on the 2017 American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/ Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Guidelines for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death and 2020 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines for the Management of Adult Congenital Heart Disease. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center (M26-150-19) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained in the form of opt-out.

Baseline clinical data, including age at implantation, sex, underlying heart disease, New York Heart Association functional classification at implantation, past history of syncope, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF) and atrial fibrillation before implantation, medication history of diuretics, β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin II receptor blocker, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 receptor inhibitors, amiodarone, sotalol, class I antiarrhythmic agents at implantation, history of cardiac operation, and electrocardiographic/echocardiographic data, were collected.

ICD implantation was classified as either primary or secondary prevention. Secondary prevention was defined as ICD implantation prevention in patients who experienced sustained VT or VF. All-cause mortality was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included appropriate ICD therapy, inappropriate ICD therapy, complications related to ICD implantation, and results of catheter ablation after ICD implantation. The appropriate ICD therapy was determined as either anti-tachycardia pacing or shock for VT or VF. The inappropriate ICD therapy was determined as those for any other rhythm except for VT or VF.

Categorical data are presented as counts and percentages. Continuous data are presented as median [IQR]. Categorical data between the primary and secondary prevention groups were evaluated using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data were compared between the two groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test were used to compare the survival curves for all-cause death, appropriate therapy, and inappropriate therapy between the two groups. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the significant variables associated with appropriate therapy. All tests were two-sided, and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

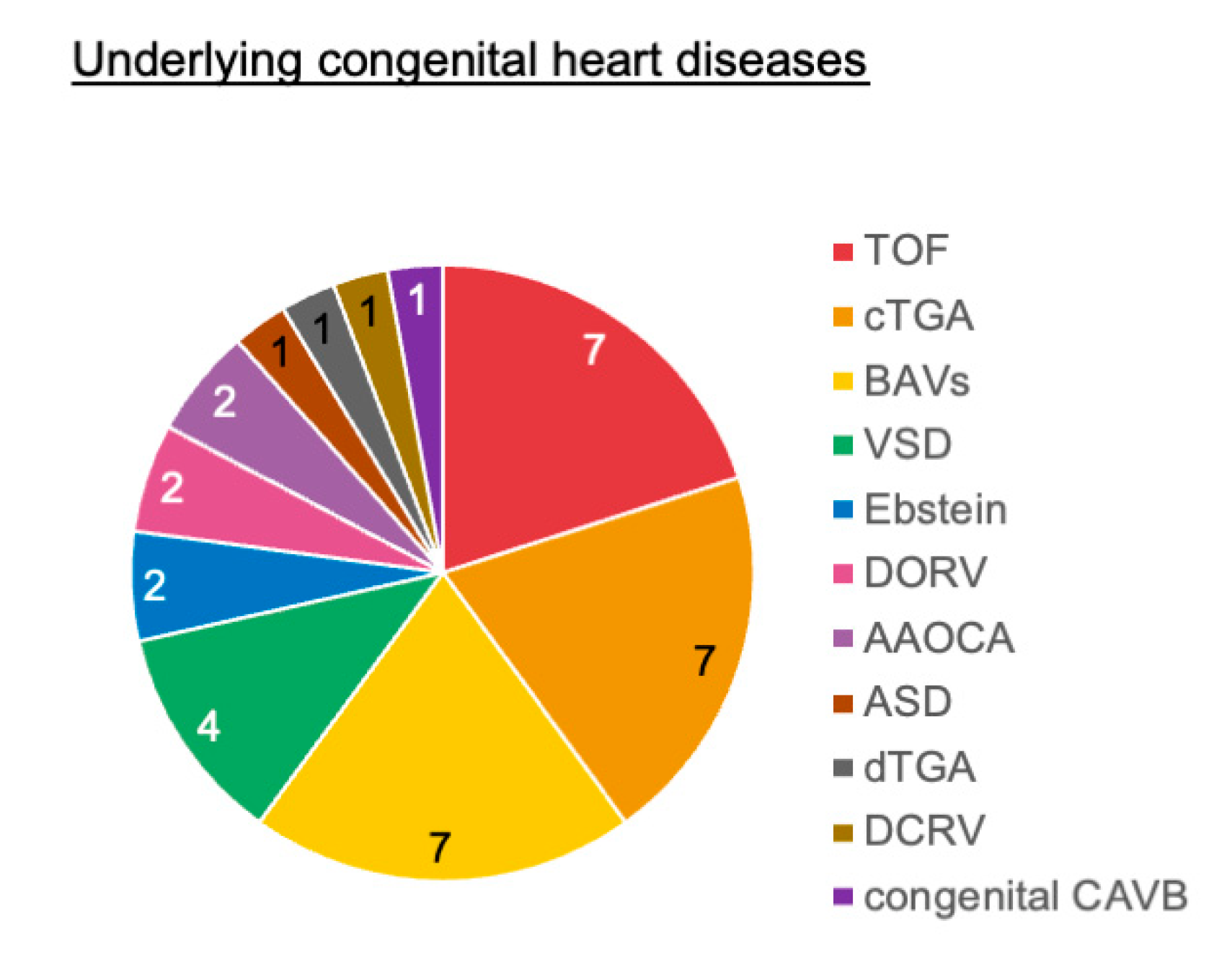

Among the 1047 patients who underwent ICD implantation, 35 patients had ACHD. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the patients. The median age at implantation was 53 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 40–62 years), and 74% of the patients were male. Twelve transvenous ICD, 8 subcutaneous ICD, and 15 cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators (CRT-D) were implanted. The underlying congenital heart diseases are presented in Fig. 1. Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF; n = 7), congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (ccTGA; n = 7), and bicuspid aortic valves (n = 7) were common.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics.

| All (n = 35) | Primary Prevention (n = 18) | Secondary Prevention (n = 17) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53 [40, 62] | 60 [42, 63] | 51 [32, 56] | 0.036 |

| Female | 9 (26) | 5 (28) | 4 (24) | >0.999 |

| Device | <0.001 | |||

| TV-ICD | 12 (34) | 5 (28) | 7 (41) | |

| S-ICD | 8 (23) | 0 (0) | 8 (47) | |

| CRT-D | 15 (43) | 13 (72) | 2 (12) | |

| Secondary prevention | 17 (49) | |||

| NYHA | 0.515 | |||

| I | 17 (49) | 7 (39) | 10 (59) | |

| II | 14 (40) | 8 (44) | 6 (35) | |

| III | 2 (5.7) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| IV | 2 (5.7) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 4 (11) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (18) | 0.338 |

| Syncope | 7 (20) | 4 (22) | 3 (18) | >0.999 |

| NSVT | 19 (54) | 15 (83) | 4 (24) | 0.001 |

| Sustained VT | 6 (17) | 0 (0) | 6 (35) | 0.008 |

| VF | 13 (37) | 0 (0) | 13 (77) | <0.001 |

| AF | 7 (20) | 5 (28) | 2 (12) | 0.402 |

| Medication | ||||

| Diuretic | 21 (60) | 14 (78) | 7 (41) | 0.041 |

| β-Blocker | 21 (60) | 14 (78) | 47 (41) | 0.041 |

| RAAS inhibitor | 17 (49) | 10 (56) | 7 (41) | 0.505 |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | 2 (5.7) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.9) | >0.999 |

| Amiodarone | 9 (26) | 5 (28) | 4 (24) | >0.999 |

| Sotalol | 4 (11) | 3 (17) | 1 (5.9) | 0.603 |

| Class 1 antiarrhythmic agents | 4 (11) | 3 (17) | 1 (5.9) | 0.603 |

| CRBBB | 14 (40) | 9 (50) | 5 (29) | 0.305 |

| CLBBB | 10 (29) | 8 (44) | 2 (11) | 0.060 |

| QRS (ms) | 159 [121, 186] | 179 [158, 192] | 123 [97, 162] | 0.002 |

| Systemic ventricular EF | 46 [31, 55] | 30 [26, 35] | 50 [43, 60] | 0.011 |

| History of cardiac surgery | 23 (66) | 13 (72) | 10 (59) | 0.489 |

| History of VA ablation | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (18) | 0.104 |

| Previous pacemaker implantation | 7 (20) | 7 (39) | 0 (0) | 0.008 |

Figure 1: Underlying congenital heart diseases. AAOCA, anomalous aortic origin of the coronary artery; ASD, atrial septal defect; BAVs, bicuspid aortic valves; CAVB, complete atrioventricular block; ccTGA, congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries; DCRV, double-chambered right ventricle; dTGA, dextrotransposition of the great arteries; DORV, double-outlet right ventricle; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

3.2 Detailed Characteristics between Primary and Secondary Prevention

Eighteen patients (51%) underwent ICD implantation for primary prevention (Table 1). Compared with the secondary prevention group, the primary prevention group was statistically older, received more CRT-D implantation, was prescribed more diuretics and β-blockers before implantation, exhibited wider QRS and lower systemic ventricular ejection fraction (EF), and received more previous pacemaker implantations.

Table 2 shows the detailed backgrounds of the patients implanted with ICD for primary prevention. According to the 2020 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Adult Congenital Heart Disease, all 18 patients had class 2a indications for ICD implantation [7]. Moreover, 5 and 12 patients had class 2a and 2b indications, respectively, for ICD according to the 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death [6]. Four patients experienced syncope with a suspected arrhythmic etiology prior to ICD implantation. Among these 4 patients, 2 had induced VT in the electrophysiology studies and the other 2 patients presented with advanced systemic ventricular dysfunction. Furthermore, 15 of 18 patients had previous evidence of NSVT, and 14 of 18 presented with systemic ventricular EF ≤ 35%. Seven patients had been previously implanted with a pacemaker, and all of whom underwent an upgrade to CRT-D because of heart failure with systemic ventricular dysfunction. Two patients had indications for pacemaker implantation due to atrioventricular block.

Table 2: Background of the patients implanted ICD for primary prevention.

| Age (Years) | Sex | Underlying Congenital Heart Disease | Systemic Ventricular EF (%) | Preexisting Device (Cause of Implantation) | Indication | 2020 ESC Class | 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | M | TOF | 54 | - | Syncope, induced VT/VF, QRS duration of 181 ms | 2a | 2a |

| 40 | F | ccTGA | 26 | - | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 67 | M | BAVs | 12 | - | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 62 | M | ccTGA | 15 | - | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 36 | M | TOF | 59 | - | NSVT, induced VT | 2a | 2a |

| 37 | M | VSD* | 19 | - | Low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 63 | F | TOF | 35 | PM (SSS) | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 66 | F | ASD† | 29 | PM (CAVB) | Syncope, NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 53 | F | dTGA | 20 | PM (SSS) | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 63 | M | ccTGA | 26 | PM (CAVB) | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 40 | M | TOF | 56 | - | NSVT, QRS duration of 181 ms, paroxysmal AVB | 2a | 2a |

| 63 | M | ccTGA | 35 | - | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 59 | M | DCRV | 55 | - | Syncope, NSVT, induced VT/VF | 2a | - |

| 47 | M | ccTGA | 30 | - | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 68 | M | ccTGA | 28 | PM (CAVB) | NSVT, low EF, pacemaker dependency | 2a | 2b |

| 57 | M | BAVs | 34 | PM (CAVB) | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2b |

| 61 | F | TOF | 29 | PM (CAVB) | NSVT, low EF, heart failure | 2a | 2a |

| 61 | M | VSD | 33 | - | Syncope, low EF, heart failure, CAVB | 2a | 2a |

Table S1 presents the backgrounds of the patients implanted with ICD for secondary prevention. Among the 17 patients who received an ICD for secondary prevention, 6 experienced sustained VT, 12 experienced VF, and 1 experienced both before ICD implantation.

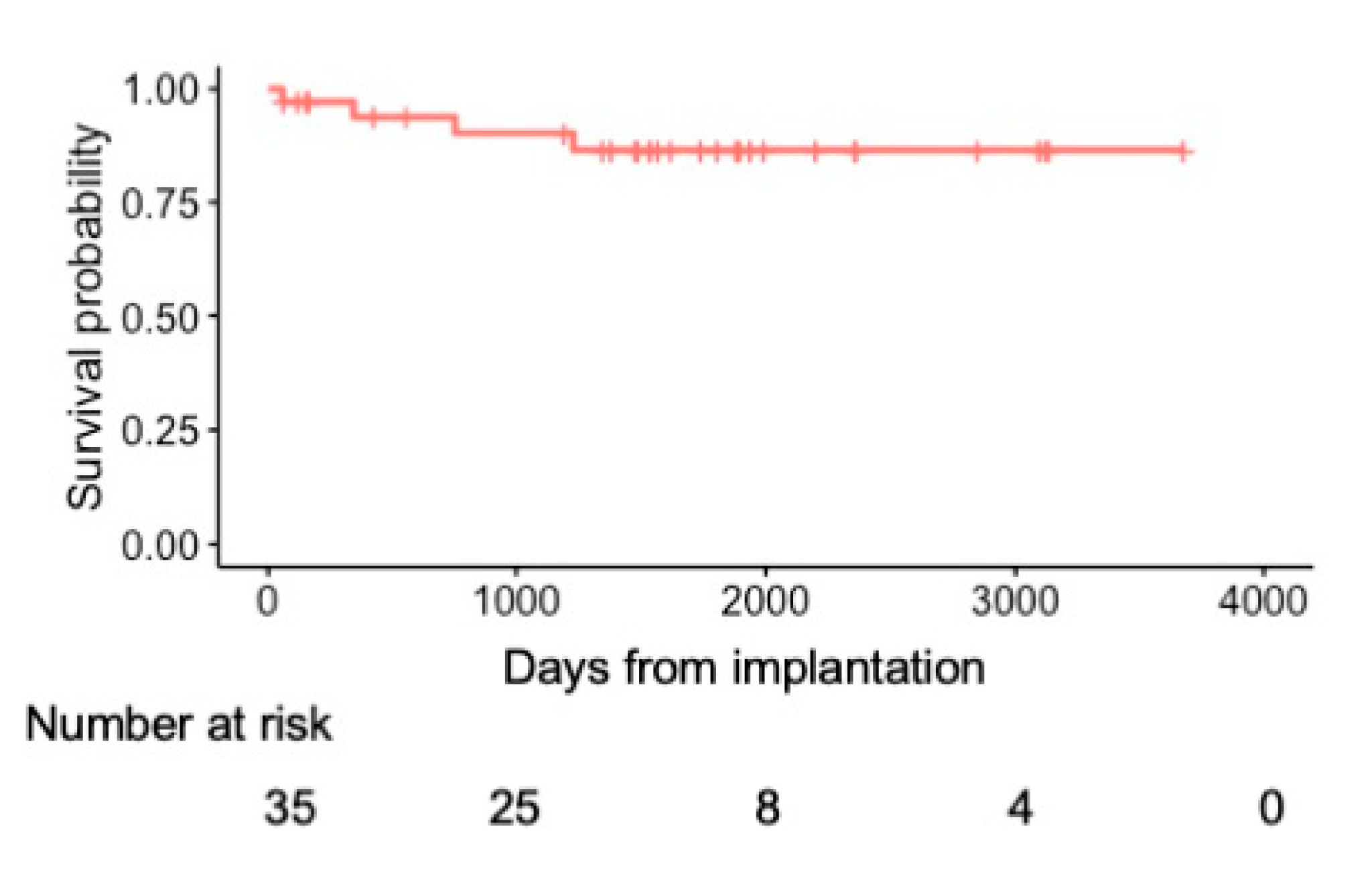

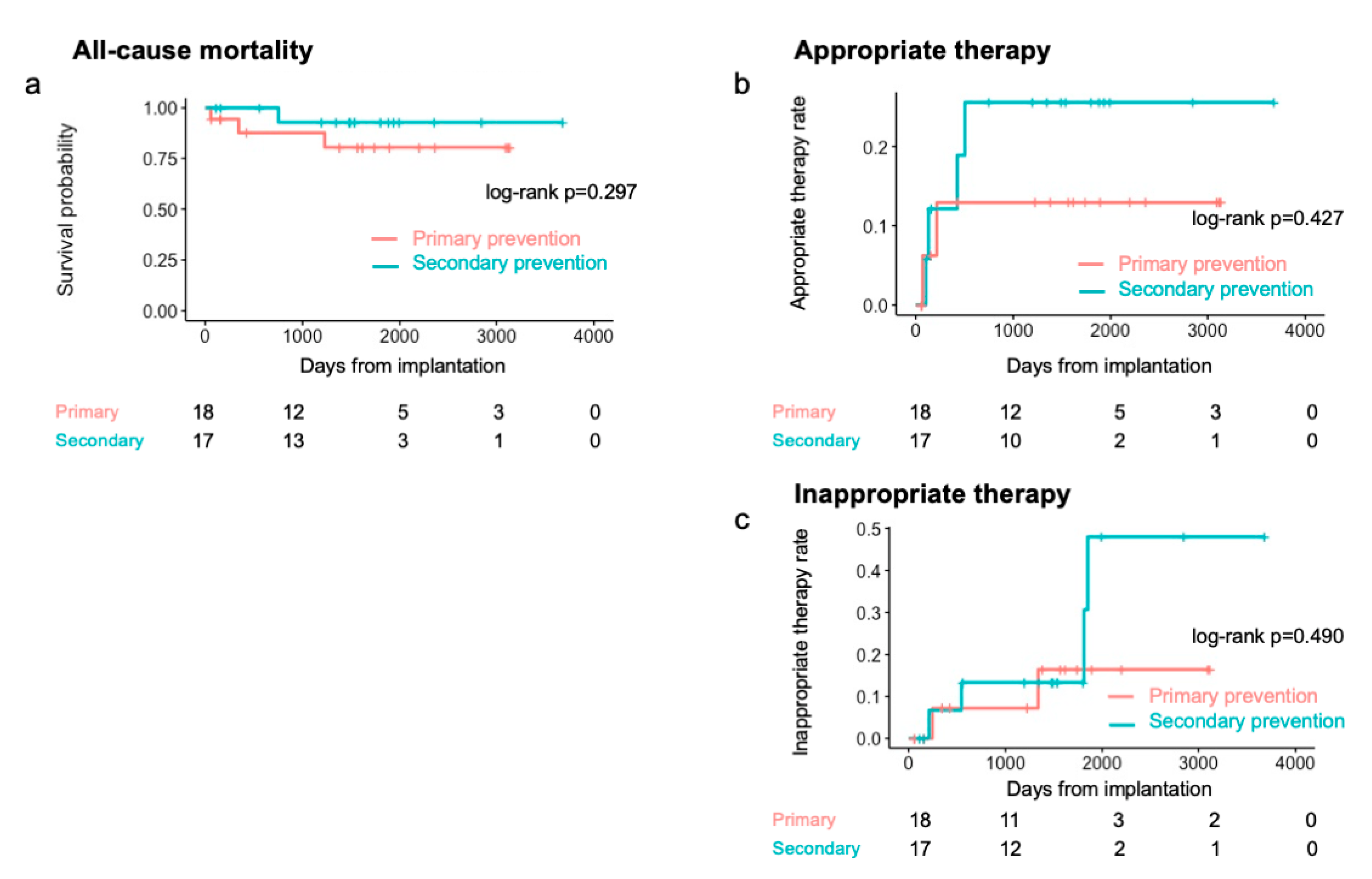

During a median follow-up period of 1484 days (IQR: 608–1863 days), 4 patients died (primary prevention group, n = 3; secondary prevention group, n = 1). Of the 4 patients, 2 died of heart failure, 1 died of bacteremia caused by lead infection, and 1 died of alcoholic hepatitis. The annual mortality rate was 3.0%. The 1-, 2- and 5-year all-cause mortality rates were 6.2%, 6.2%, and 13.6%, respectively (Fig. 2). The Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed no significant difference in all-cause mortality between the primary and secondary prevention groups (log-rank p = 0.297) (Fig. 3a).

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier curve of all-cause mortality in the overall cohort.

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier curves in primary and secondary prevention. (a) All-cause mortality. (b) Appropriate therapy rate. (c) Inappropriate therapy rates. Pink lines, primary prevention group; blue lines, secondary prevention group.

Six patients (17%: TOF, n = 2; BAVs, n = 1; others, n = 3) received appropriate therapy, of whom 2 (11.1%) were in the primary prevention group and 4 (23.5%) were in the secondary prevention group. The annual appropriate therapy rate was 5.0%. The Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed no significant difference in the rate of appropriate therapy between the two groups (log-rank p = 0.427) (Fig. 3b). The 2-year appropriate therapy rates were 13% and 26% in the primary and secondary prevention groups, respectively. In the univariate analysis, only a history of sustained VT was a significant factor affecting appropriate therapy (p = 0.049). Table 3 presents the details of the patients who received appropriate therapy. The median interval from implantation to the first appropriate therapy was 174 days (IQR: 113–374 days; minimum: 71 days; maximum: 505 days). Among the 6 patients, 2 with TOF underwent VT ablation before implantation. Including those 2 patients, 4 underwent VT ablation after ICD implantation; however, 2 patients experienced VT recurrence with appropriate therapy regardless of VT non-inducibility at the end of the ablation procedure.

Table 3: Details of the patients with appropriate ICD therapy.

| Underlying Congenital Heart Disease | Indication | EF (%) | Past Cardiac Surgery | Therapy | Days from Implantation to the First Therapy | VT Ablation before ICD Implantation | VT Ablation after ICD Implantation/VT Recurrence with Appropriate Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOF | Secondary | 34 | 1. ICR | ATP | 132 | + | +/+ |

| 2. VSD closure | |||||||

| 3. PVR | |||||||

| ASD* | Primary | 29 | None | ATP | 216 | − | − |

| DORV | Secondary | 79 | 1. ICR | Shock | 106 | − | +/+ |

| 2. Repeat ICR | |||||||

| TOF | Secondary | 43 | ICR | ATP | 426 | + | +/− |

| BAVs | Secondary | 16 | AVR | ATP/shock | 505 | − | +/− |

| VSD | Primary | 33 | VSD closure | Shock | 71 | − | − |

Six (17%) patients received inappropriate therapy (Table 4), of whom 2 (11.1%) were in the primary prevention group and 4 (23.5%) were in the secondary prevention group. The Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed no significant difference in the rate of inappropriate therapy between the two groups (log-rank p = 0.490) (Fig. 3c). The median interval from implantation to the first inappropriate therapy was 941 days (IQR: 321–1693 days; minimum: 212 days; maximum: 1852 days). The causes of inappropriate therapy were atrial arrhythmias in 4 patients and T-wave oversensing in 2 patients. One patient underwent ablation for atrial arrhythmia, and no inappropriate shock occurred after the ablation blanking period. Among the other 3 patients who received inappropriate therapy due to atrial arrhythmia, the β-blocker dosage was increased in 1 patient. Thereafter, the patient was free from inappropriate therapy due to atrial arrhythmia for over 4 years; however, the patient received inappropriate shock due to noise.

Table 4: Details of the patients with inappropriate ICD therapy.

| Underlying Congenital Heart Disease | Device | Indication | Therapy | Days from Implantation to the First Therapy | Cause of Inappropriate Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAVs | CRT-D | Primary | ATP | 246 | AF |

| TOF | CRT-D | Primary | ATP | 1337 | AT |

| TOF | TV-ICD | Secondary | ATP | 1812 | AT |

| Ebstein disease | S-ICD | Secondary | Shock | 546 | TWOS |

| VSD | S-ICD | Secondary | ATP | 1852 | TWOS |

| BAVs | TV-ICD | Secondary | ATP | 212 | AT |

Device-related complications were observed in 2 patients during follow-up. A patient with an anomalous aortic origin of coronary artery presented with lead failure 7 years after transvenous ICD implantation and required reimplantation. Another patient with ccTGA developed bacteremia caused by lead infection, resulting in death 3 years after CRT-D implantation.

In this study, we investigated the long-term outcomes after ICD implantation in patients with ACHD. The main findings of this study were as follows: (1) All the patients in our study had ICD indications prescribed in the recent guidelines. (2) All-cause mortality and device-related complication rates were relatively low in patients with ACHD despite the considerably high appropriate therapy rate. (3) There was no significant difference in appropriate ICD therapy between the primary and secondary prevention groups.

In the previous studies, 44%–63% of ICD implantations in patients with ACHD were used for primary prevention [5,8,9,10,11]. Our studied population was the same as those of previous reports; however, there were no cases deviating from the indications of the current guidelines, unlike a previous report [9]. Risk stratification for sudden cardiac death in patients with ACHD remains unresolved, and the discriminative ability for sudden cardiac death according to the guidelines is poor [12]. Therefore, deciding whether to implant an ICD for primary prevention in ACHD patients remains challenging. Current guidelines state the following conditions for class 2 ICD recommendation: symptomatic heart failure and EF ≤ 35%, unexplained syncope and either advanced ventricular dysfunction or inducible VT/VF, TOF patients with multiple risk factors for sudden cardiac death, including ventricular dysfunction, NSVT, QRS ≥ 180 ms, extensive right ventricular scarring on magnetic resonance imaging, or inducible VT [6,7]. In our study, the evidence for ICD implantation in patients with primary prevention was extensive. However, many of the patients had NSVT and/or heart failure with systemic ventricular dysfunction. Unexplained syncope with inducible ventricular arrhythmia was not a common reason for implantation. Moreover, several patients required pacemaker upgrade to CRT-D. Indications for implantation may have been influenced not only by the need for sudden cardiac death prevention but also by the necessity for CRT-D.

Considering the outcome in ACHD patients with an ICD, a comparison with other heart diseases would be useful. In patients with coronary artery disease, the 2-year all-cause mortality rate has been reported to be 8.7% for primary prevention and 12.7% for secondary prevention, respectively [13]. Furthermore, the annual mortality rate in the ICD population with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy has been reported to be 5.8% [14]. Meanwhile, previous studies on ACHD patients with ICD have reported an annual mortality rate of approximately 3% [5,9]. In our study, the annual mortality rate in overall ACHD patients with ICD was 3.0%, and the 2-year all-cause mortality rates were 13.3% in primary prevention, 0% in secondary prevention, and 6.2% in the overall studied population. Mortality in ACHD patients with an ICD appears to be lower than that in patients with acquired heart disease, especially for secondary prevention.

Previous studies investigated several risk factors for appropriate ICD therapy in patients with ACHD. Koyak et al. reported that secondary prevention indications, coronary artery disease, and symptomatic NSVT are associated with appropriate shocks [8]. Conversely, our findings demonstrated no significant differences in the appropriate therapy between the primary and secondary prevention groups, even though the univariate analysis showed that a history of sustained VT was significantly more frequent in appropriate therapy. The more recent period of investigation in our study may have influenced these differences, as indications for primary prevention have been reviewed, and the guidelines for ICD indication have been updated in the last decade. In a more recent study, Coutinho Cruz et al. reported no baseline characteristics associated with appropriate therapy in 30 patients with various ACHD until 2016, which is consistent with the findings of our study [9]. Moreover, several previous studies have shown no difference in the rates of appropriate shock between the primary and secondary groups [15,16]. Additionally, a meta-analysis of ICD in patients with ACHD showed a considerably high rate of appropriate therapy, both in primary prevention (22% in 3.3 years) and secondary prevention (35% in 4.3 years) [5]. Similarly, our study found no difference in the rates of appropriate therapy between primary and secondary prevention groups; both rates were >10% at 4 years. A certain number of patients benefited from ICD implantation for primary prevention, but the risk factors associated with ICD therapy could not be identified. However, our small sample size also likely influenced this outcome.

Compared with patients with acquired heart disease, those with ACHD showed a similar incidence of appropriate therapy. The 2-year appropriate therapy rates in patients with coronary artery disease have been reported to be 15.3% and 23.9% for primary and secondary prevention, respectively [13]. In patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 23% received appropriate therapy within 3.1 years [17]. Furthermore, the average annual rate of appropriate ICD shock in populations with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathies has been reported to be 5.1% [14]. An appropriate therapy rate in our study was equivalent to the rates reported in previous studies on patients with ACHD and comparable to those in patients with acquired heart diseases. Considering the relatively low mortality and comparable appropriate therapy rates, guideline-based ICD implantation in selected ACHD populations would be valuable.

Inappropriate therapy is a common problem encountered with ICD. Since patients with ACHD often experience atrial tachyarrhythmias, a high rate of inappropriate therapy has been reported [5,8,9]. In a meta-analysis, the annual rate of inappropriate therapy in ACHD patients was 8.1% [5]. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies. However, anti-tachycardia pacing is commonly used, and inappropriate therapy caused by atrial arrhythmia can be prevented through pharmacological or ablation therapy. Inappropriate shocks can be reduced by reprogramming the device or treating atrial arrhythmia. In our cases, ablation or medication for atrial arrhythmia was beneficial in preventing inappropriate therapy.

4.5 Device-Related Complications

The high incidence of lead- and pocket-related complications has been also a concern. Previous studies reported that the annual rate of complications requiring repeat interventions is approximately 5% [5,8,9]. Difficulty in lead placement due to complex anatomy and the requirement of additional cardiac intervention leading to an unstable lead were considered reasons for the high complication rate [18]. However, only 1 of 35 cases required repeated lead replacement during the observation period in our study. The development of device and lead technology may have influenced the lower incidence of complications than that in previous studies. Notably, the introduction of subcutaneous ICD can reduce these complications. In previous studies, the great majority of implanted devices were transvenous ICD, whereas in our study, more than 20% of the implanted devices were subcutaneous ICD. ICD implantation in patients with ACHD has become a safer strategy over the past decade.

Catheter ablation is currently indicated as an additional therapy in ACHD patients with ICD who present with recurrent VT [19]. Moreover, VT ablation in patients with TOF has been suggested as a reasonable alternative therapy to ICD. However, although acute success rates are high because of well-identified anatomical isthmuses of re-entry VT in repaired congenital heart disease, the recurrence of VT cannot be ignored. Although Kapel et al. reported that repaired congenital heart disease patients with complete procedural success and preserved cardiac function remained free from VT recurrence over a 2-year follow-up [20], several patients in our study required repeated ablation due to VT recurrence, including even those with preserved cardiac function. According to these results, catheter ablation could not be an alternative therapy for ICD in all patients with ACHD. However, due to our limited sample size, further research is warranted to identify specific conditions where ICD implantation might be avoided after VT ablation. Careful consideration is required when selecting the patients who may not require ICD implantation after successful ablation.

This study has some limitations. First, this was a single-center, retrospective study. There was a high risk of selection bias in patient selection, and the number of patients included was too small to evaluate the overall ACHD population. Specifically, the interpretation of the indication for primary prevention and recommendation for patients may differ between institutions. Therefore, further research, such as multi-center study, is warranted. However, the distribution of the diseases was similar to that in previous larger studies and meta-analyses; TOF and ccTGA accounted for the majority of the study population [5,8]. Second, because this cohort was collected over 10 years, the development of the device management in recent years would influence the outcomes. Instead, we evaluated long-term outcomes. Finally, we evaluated various ACHD conditions together. Some patients had other coexisting heart diseases, which may have influenced mortality and arrhythmia. Research with larger and more specific populations is needed.

All-cause mortality in ACHD patients with an ICD was relatively lower than that in patients with acquired heart disease. In contrast, the incidence of appropriate ICD treatment in patients with ACHD was considerably high and comparable to that observed in patients with acquired heart disease, both in primary and secondary prevention. ICD implantation for primary prevention as well as for secondary prevention may be important in patients with ACHD.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design, Mai Ishiwata and Kohei Ishibashi; data collection, Mai Ishiwata, Yoshiaki Kato, Heima Sakaguchi and Toshihiro Nakamura; analysis and interpretation of results, Mai Ishiwata, Kohei Ishibashi, Satoshi Oka, Yuichiro Miyazaki, Akinori Wakamiya, Nobuhiko Ueda, Kenzaburo Nakajima, Tsukasa Kamakura, Mitsuru Wada, Yuko Inoue, Koji Miyamoto and Takeshi Aiba; drafting manuscript preparation, Mai Ishiwata, Kohei Ishibashi, Norihiko Takeda and Kengo Kusano. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, Kohei Ishibashi.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center (M26-150-19) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained in the form of opt-out.

Conflicts of Interest: Kengo Kusano reports funding/grants received from Medtronic Japan Co., Ltd., and speakers’ bureaus from Medtronic Japan Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. Kohei Ishibashi received honoraria for lectures from Medtronic Japan Co., Ltd., Japan Lifeline Co., Ltd., and Biotronik Japan Inc., outside the submitted work. Akinori Wakamiya received honoraria for lectures from Medtronic Japan Co., Ltd., and Biotronik Japan Inc., outside the submitted work. Satoshi Oka and Nobuhiko Ueda received honoraria for lectures from Medtronic Japan Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. Koji Miyamoto received funding/grants received from Medtronic Japan Co., Ltd., Abbott Japan LLC., and Boston Scientific Japan Co., Ltd., and honoraria/speakers’ bureaus from Medtronic Japan Co., Ltd., Abbott Japan LLC., and Boston Scientific Japan Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work, and is affiliated with a department endowed by Medtronic Japan Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/chd.2025.067716/s1.

Abbreviations

| adult congenital heart disease | |

| congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries | |

| cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators | |

| ejection fraction | |

| implantable cardioverter-defibrillators | |

| interquartile range | |

| non-sustained ventricular tachycardia | |

| tetralogy of Fallot | |

| ventricular fibrillation | |

| sustained ventricular tachycardia |

References

1. Koyak Z, de Groot JR, Mulder BJ. Interventional and surgical treatment of cardiac arrhythmias in adults with congenital heart disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;8(12):1753–66. doi:10.1586/erc.10.152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Oechslin EN, Harrison DA, Connelly MS, Webb GD, Siu SC. Mode of death in adults with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86(10):1111–6. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01169-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Koyak Z, Harris L, de Groot JR, Silversides CK, Oechslin EN, Bouma BJ, et al. Sudden cardiac death in adult congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2012;126(16):1944–54. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Diller GP, Kempny A, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Swan L, Uebing A, Li W, et al. Survival prospects and circumstances of death in contemporary adult congenital heart disease patients under follow-up at a large tertiary centre. Circulation. 2015;132(22):2118–25. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Vehmeijer JT, Brouwer TF, Limpens J, Knops RE, Bouma BJ, Mulder BJ, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in adults with congenital heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(18):1439–48. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(14):e91–220. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, Budts W, Chessa M, Diller GP, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(6):563–645. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Koyak Z, de Groot JR, Van Gelder IC, Bouma BJ, van Dessel PF, Budts W, et al. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in adults with congenital heart disease: who is at risk of shocks? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5(1):101–10. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.111.966754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Coutinho Cruz M, Viveiros Monteiro A, Portugal G, Laranjo S, Lousinha A, Valente B, et al. Long-term follow-up of adult patients with congenital heart disease and an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019;14(4):525–33. doi:10.1111/chd.12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Moore BM, Cao J, Cordina RL, McGuire MA, Celermajer DS. Defibrillators in adult congenital heart disease: long-term risk of appropriate shocks, inappropriate shocks, and complications. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;43(7):746–53. doi:10.1111/pace.13974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Slater TA, Cupido B, Parry H, Drozd M, Blackburn ME, Hares D, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy to reduce sudden cardiac death in adults with congenital heart disease: a registry study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31(8):2086–92. doi:10.1111/jce.14633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Vehmeijer JT, Koyak Z, Budts W, Harris L, Silversides CK, Oechslin EN, et al. Prevention of sudden cardiac death in adults with congenital heart disease: do the guidelines fall short? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10(7):e005093. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.116.005093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kondo Y, Noda T, Sato Y, Ueda M, Nitta T, Aizawa Y, et al. Comparison of 2-year outcomes between primary and secondary prophylactic use of defibrillators in patients with coronary artery disease: a prospective propensity score-matched analysis from the Nippon Storm Study. Heart Rhythm O2. 2021;2(1):5–11. doi:10.1016/j.hroo.2020.12.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(3):225–37. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yap SC, Roos-Hesselink JW, Hoendermis ES, Budts W, Vliegen HW, Mulder BJ, et al. Outcome of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in adults with congenital heart disease: a multi-centre study. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(15):1854–61. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Santharam S, Hudsmith L, Thorne S, Clift P, Marshall H, De Bono J. Long-term follow-up of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in adult congenital heart disease patients: indications and outcomes. Europace. 2017;19(3):407–13. doi:10.1093/europace/euw076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Maron BJ, Shen WK, Link MS, Epstein AE, Almquist AK, Daubert JP, et al. Efficacy of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for the prevention of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(6):365–73. doi:10.1056/NEJM200002103420601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Albertini L, Kawada S, Nair K, Harris L. Incidence and clinical predictors of early and late complications of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in adults with congenital heart disease. Can J Cardiol. 2023;39(3):236–45. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2022.12.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hernández-Madrid A, Paul T, Abrams D, Aziz PF, Blom NA, Chen J, et al. Arrhythmias in congenital heart disease: a position paper of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Group on Grown-up Congenital heart disease, endorsed by HRS, PACES, APHRS, and SOLAECE. Europace. 2018;20(11):1719–53. doi:10.1093/europace/eux380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kapel GF, Reichlin T, Wijnmaalen AP, Piers SR, Holman ER, Tedrow UB, et al. Re-entry using anatomically determined isthmuses: a curable ventricular tachycardia in repaired congenital heart disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8(1):102–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools