Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

2025 Chinese Expert Consensus on Clinical Applications of Biodegradable Patent Foramen Ovale Occluders

1 Guangdong Cardiovascular Institute, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences), Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, 510080, China

2 Center of Structural Heart Disease, Chinese Academy of Medical Science, Fuwai Hospital, Peking Union Medical College, National Center of Cardiovascular Disease, Beijing, 100037, China

3 Center of Structural Heart Disease, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430071, China

4 Department of Congenital Heart Disease, General Hospital of the Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, 110840, China

5 Department of Cardiology, Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, 410008, China

6 Department of Cardiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330008, China

7 Cardiac Surgery Department, Wuhan Asia Heart Hospital, Wuhan, 430022, China

8 Department of Cardiology, Shenzhen People’s Hospital (First Affiliated Hospital of Southern University of Science and Technology, Second Clinical Medical College of Jinan University), Guangzhou, 518020, China

9 Department of Cardiology, China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, 130033, China

10 Department of Cardiology, the Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310009, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiangbin Pan. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(4), 403-420. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.071050

Received 30 July 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 18 September 2025

Abstract

Compared with traditional nickel-titanium alloy patent foramen ovale occluders, which are widely used in clinical practice, biodegradable patent foramen ovale occluders have obvious differences in material characteristics, interventional operation mode and postoperative management strategy. This article gives expert consensus on the selection of clinical indications and standardized operating procedures, so as to standardize the clinical application of biodegradable patent foramen ovale occluders.Keywords

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is associated with some of the ischemic strokes, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and migraine with aura. Evidence-based medical evidence suggests that for specific patients, PFO occlusion can reduce the risk of stroke recurrence [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Currently, PFO occluders mainly made of nickel-titanium alloy are widely used in clinical practice and have become the main treatment method for PFO-related diseases. Nickel-titanium alloy occluders are mainly composed of a nickel-titanium alloy framework and a polyester fiber occluding membrane, both of which are non-degradable materials. After implantation, they remain in the body for life and have the following problems [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]: (1) Nickel ion release and metal allergy; (2) Wear of local tissues by metal occluders, resulting in related complications (such as abrasion, perforation, cardiac tamponade); (3) Poor endothelialization and device-related thrombosis events; (4) Metal occluders make subsequent transseptal interventional treatments difficult, such as atrial fibrillation (AF) radiofrequency catheter ablation and transcatheter mitral valve repair. The application of biodegradable occluders offers a viable solution to the aforementioned challenges, thereby fulfilling the objective of “intervention without permanent implantation”. Chinese researchers have made great progress on developing biodegradable PFO occluders and one of them has been approved for clinical application by the National Medical Products Administration. Compared with traditional nickel-titanium alloy occluders, biodegradable PFO occluders exhibit significant differences in material properties, interventional techniques, and postoperative management protocols. To ensure the safe and standardized adoption of biodegradable PFO occluders among clinicians specializing in interventional therapy of structural heart disease, the Professional Committee of the National Quality Management and Control Center for Structural Heart Diseases and the Professional Committee of Structural Heart Diseases of the National Cardiovascular Disease Expert Committee convened a panel of experts to develop this consensus document. These recommendations delineate the indications, procedural guidelines, key considerations, therapeutic objectives, and efficacy assessment criteria for the clinical use of biodegradable PFO occluders, thereby promoting standardized diagnostic and therapeutic practices.

As biodegradable PFO occluders have only recently been introduced into clinical practice, the cumulative number of cases remains limited. Currently, there is a paucity of relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) both domestically and internationally. Available evidence is primarily derived from small-sample clinical studies, pre-market clinical investigations of biodegradable PFO occluders, and extrapolated experience from traditional metal occluder applications. The evidence evaluation and recommendation grading for these guidelines were conducted using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system (Table 1 and Table 2) [14].

Table 1: GRADE Recommendation Strength Grading and Definition.

| Recommendation Strength | Explanation | Expression Method | Recommendation Strength Level |

| Strongly recommended for use | The benefits of the intervention clearly outweigh the harms | Recommend | I |

| Weakly recommended for use | The benefits of the intervention may outweigh the harms | Suggest | II |

| Weakly recommended against use | The harms of the intervention may outweigh the benefits or the balance between benefits and harms is unclear | Do not suggest | II |

| Strongly recommended against use | The harms of the intervention clearly outweigh the benefits | Do not recommend | I |

Table 2: GRADE Evidence Quality Grading and Definition.

| Quality Level | Definition |

| High (A) | There is a high degree of confidence that the true value is close to the observed value |

| Moderate (B) | There is a moderate degree of confidence in the observed value: the true value is likely to be close to the observed value, but there is still a possibility that they are different |

| Low (C) | The degree of confidence in the observed value is limited: the true value may be different from the observed value |

| Very low (D) | There is almost no confidence in the observed value: the true value is likely to be very different from the observed value |

2 Characteristics of Biodegradable PFO Occluders

An ideal biodegradable PFO occluder serves as a transitional scaffold to facilitate autologous tissue repair. Its primary structure gradually degrades and becomes absorbed in synchrony with the endothelialization process, ultimately achieving complete physiological restoration while fulfilling the following criteria [11]: (1) Upon complete absorption of the device, the defect site should demonstrate healthy, functional native tissue regeneration; (2) Following absorption, no residual foreign material remains that could potentially interfere with normal cardiac structure or function. The biodegradable occluders currently under clinical investigation predominantly utilize synthetic polymers including poly(p-dioxanone) (PDO), poly(L-lactic acid) (PLA), and polycaprolactone (PCL). These materials are precisely formulated through compositional adjustments to meet specific clinical requirements, and are strategically incorporated into both the occluder framework and sealing membrane components. This design approach enables effective atrial septal reconstruction while ensuring optimal occlusion performance and controlled degradation kinetics [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

These biocompatible materials undergo metabolic degradation into carbon dioxide and water, which are subsequently eliminated via renal and pulmonary excretion pathways [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Animal studies demonstrate that the majority of these materials achieve complete degradation within 6 months to 3 years post-implantation [22,29,30,31,33,34,35], which realizes the clinical objective of “intervention without permanent implantation”.

Over the past two decades, multiple biodegradable PFO occluder systems have been developed globally and advanced to clinical investigation stages [19,21,36,37,38,39,40]. Chinese researchers have brought innovations on the improvement of the clinical performance of biodegradable PFO occluder: (1) Material Composition: Poly(p-dioxanone) (PDO) for the dual-disk framework, and Poly(L-lactic acid) (PLA) for the occlusive membrane; (2) Structural Innovations: Patented edge-locking mechanism, and forming-wire locking design. These technological breakthroughs provide enhanced mechanical support and disk apposition force while maintaining stability during cardiac motion. The device’s unique architecture demonstrates superior adaptation to complex PFO anatomies, optimizing both immediate closure efficacy and long-term tissue remodeling [26]. Therefore, biodegradable PFO occluders were officially introduced into clinical practice in China in December 2023. These expert consensus recommendations establish standardized protocols for the clinical application of biodegradable PFO occluders, with the currently approved device serving as the representative model.

3 Clinical Indications and Contraindications for Biodegradable PFO Occluder Implantation

Since 2017, emerging evidence from multicenter clinical trials has consistently demonstrated that transcatheter PFO closure provides superior outcomes in reducing stroke recurrence risk compared to medical therapy alone [1,2,3,4]. Subsequently, both domestic and international guidelines on PFO management have been progressively updated [5,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. For patients who meet the following indications after being diagnosed with PFO-related conditions through multidisciplinary team (MDT) evaluation involving neurologists and other specialists, the use of biodegradable PFO occluders for interventional therapy is recommended.

- (1)PFO-related stroke patients aged 18–60 years old (1A).

- (2)PFO-related stroke patients over 60 years old whose benefits of PFO occlusion evaluated before procedure are higher than the risks of interventional related operations (2B).

- (3)For PFO-related stroke patients under 18 years old, there must be clear clinical evidence of PFO-related stroke, and it should be carefully selected after strict MDT consultations (more clinical evidence-based medical evidence needs to be accumulated) (2B).

- (4)PFO-related stroke patients whose benefits of PFO occlusion evaluated before procedure are higher than the risks of interventional related operations and with the following comorbidities:

- ➀PFO-related stroke patients with thrombophilia (2B).

- ➁PFO-related stroke patients with a history of deep vein thrombosis who need lifelong anticoagulant therapy (2B).

- ➂PFO-related stroke patients with a history of pulmonary embolism who need lifelong anticoagulant therapy (2B).

- (5)Migraine patients with severely affected quality of life and poor response to standardized drug treatment, especially migraine with aura, and whose potential benefits of PFO occlusion evaluated before procedure are higher than the potential risks (2B).

- (6)PFO-related platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome (2B).

- (7)PFO-related decompression sickness, and whose potential benefits of PFO occlusion evaluated before procedure are higher than the potential risks (2B).

- (8)PFO patients with combined systemic embolism, and other causes of systemic embolism have been excluded before surgery (2C).

- (9)PFO-related disease patients with metal allergies such as nickel allergy (2C).

- (10)Patients who meet the indications for PFO occlusion but are not suitable for metal occluders due to objective factors (2C).

- (1)Cerebral embolism for which non-PFO-related causes can be clearly identified (1A).

- (2)Contraindications to anti-platelet or anticoagulant therapy, such as severe bleeding within 3 months, obvious retinopathy, a history of other intracranial hemorrhage, and obvious intracranial diseases (1B).

- (3)Complete obstruction of the surgical access, systemic or local infection, sepsis, and thrombus formation in the cardiac cavity (1A).

- (4)Combined with pulmonary hypertension or PFO serving as a special channel to maintain and relieve atrial pressure (1A).

- (5)Large-area cerebral infarction within 4 weeks (2B).

4 Preprocedural Evaluation and Preparation for Biodegradable PFO Occluder Implantation

4.1 Required Equipment and Instrumentation

Echocardiography diagnostic equipment, digital subtraction angiography system (preferred for X-ray-guided procedures), multipurpose angiographic (MPA) catheter, 0.035″ hydrophilic guidewire, 0.035″ extra-stiff exchange guidewire, guidewire specifically designed for echocardiography-guided procedures, biodegradable PFO occluder with its compatible delivery system.

- (1)Routine physical examination: echocardiography, chest X-ray, standard and ambulatory electrocardiography (ECG/Holter monitoring), preoperative laboratory tests (complete blood count, coagulation profile, etc.).

- (2)Imaging examinations for PFO diagnosis: contrast-enhanced transcranial Doppler (cTCD), contrast-enhanced transthoracic echocardiogram (cTTE), contrast-enhanced transesophageal echocardiogram (cTEE), et al.

- (3)Evaluations for PFO-related pathologies: non-contrast brain MRI, non-contrast head CT, carotid duplex ultrasound, lower extremity venous ultrasound, cerebral/carotid CT, angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA), etc.

The patient and legal guardians must sign the interventional procedure consent form.

It is recommended to routinely perform TEE before PFO closure to screen for potential contraindications, such as small atrial septal defects or multifenestrated PFO, which may be undetectable by TTE. TEE would further evaluate the PFO’s anatomical characteristics including morphological structure, defect size, tunnel length, and spatial orientation.

5 Transcatheter Procedure Steps for Biodegradable PFO Occluder Implantation

The transcatheter procedure for biodegradable PFO occluder implantation can be performed either under echocardiography guidance alone or as a combined echocardiography/X-ray-guided approach. The following demonstrates both techniques separately, based on the currently approved biodegradable PFO occluder system.

5.1 Echocardiography-Guided Percutaneous Implantation of Biodegradable PFO Occluders

- (1)Preoperative preparation: For patients with adequate transthoracic acoustic windows, perform TTE-guided percutaneous biodegradable PFO occluder implantation under local anesthesia in the catheterization laboratory or operating room (applicable for most cases).

For patients with poor transthoracic acoustic windows, perform TEE-guided percutaneous biodegradable PFO occluder implantation under general anesthesia.

All patients require preoperative fasting and intravenous access establishment.

- (2)Working distance measurement: Measure the anatomical distance between proximal point, third intercostal space at the right midclavicular line, and distal point, planned femoral venous puncture site. This measured working distance should be clearly marked on both delivery catheter and guidewire.

- (3)Intraoperative bedside TTE reexamination: Baseline assessment includes evaluation of atrial septal morphology and general structure. Select appropriately occluders and delivery sheaths based on preoperative TEE and TTE measurements.

- (4)Occluder model selection principle: The biodegradable PFO occluder system comprises eight distinct models, with four featuring equilateral double disks and four featuring non-equilateral double disks. These models are primarily categorized into four types based on right atrial disk diameter. Occluder selection should be guided by the specific PFO anatomical characteristics: For simple PFO: Either an 18-mm or 24-mm occluder is preferred. For complex PFO or PFO with small aneurysm (basal diameter <8–34 mm): A 28-mm occluder is recommended. For PFO with large aneurysm (basal diameter 28–34 mm): A 34-mm occluder should be considered. The equilateral occluder design is preferentially recommended for most cases.

- (5)Delivery sheath selection and insertion: The appropriate delivery sheath size should be matched to the occluder diameter as follows: 18-mm occluder-a 12F delivery sheath; 24-mm or 28-mm occluder-a 14F delivery sheath (facilitates potential occluder retrieval); 34-mm occluder-a 16F delivery sheath. Advance the delivery sheath into the left atrium or left upper pulmonary vein over the extra-stiff guidewire, while maintaining continuous attention to proper air evacuation during manipulation and maintenance of the sheath tail within the water basin.

- (6)Under local or general anesthesia, perform femoral vein (or jugular vein) puncture and insert a 6F sheath. Administer intravenous heparin (100 U/kg). Following the right heart catheterization to exclude pulmonary hypertension, mark the catheter length. Advance a 6F catheter and guidewire through the puncture sheath into the inferior vena cava. Position the guidewire tip to extend beyond the catheter, exposing its reticular rhomboid tip. Simultaneously advance both catheter and guidewire to the inferior vena cava-right atrial junction.

When echocardiography (subxiphoid bicaval view) confirms the guidewire and catheter at the inferior vena cava orifice, advance both to the atrial septum midpoint. In the apical four-chamber view, position the guidewire’s reticular rhomboid tip against the fossa ovalis. Switch to the aortic short-axis view. Under echocardiographic guidance, fine-tune catheter/guidewire alignment, rotate the catheter clockwise, position it against the aortic-facing fossa ovalis, stabilize the guidewire while gently advancing the catheter, partially retract the guidewire tip while maintaining forward catheter rotation to locate the PFO’s right atrial orifice, and advance the catheter through the PFO into the left atrium. After left atrial access, adjust catheter and guidewire orientation, position the guidewire in the left upper pulmonary vein’s proximal segment (behind the crista terminalis), Remove the 6F MPA catheter and puncture sheath, introduce the pre-marked delivery sheath over the guidewire under aortic short-axis echocardiographic guidance, withdraw both guidewire and sheath dilator, and maintain the sheath tip freely positioned in the mid-left atrium.

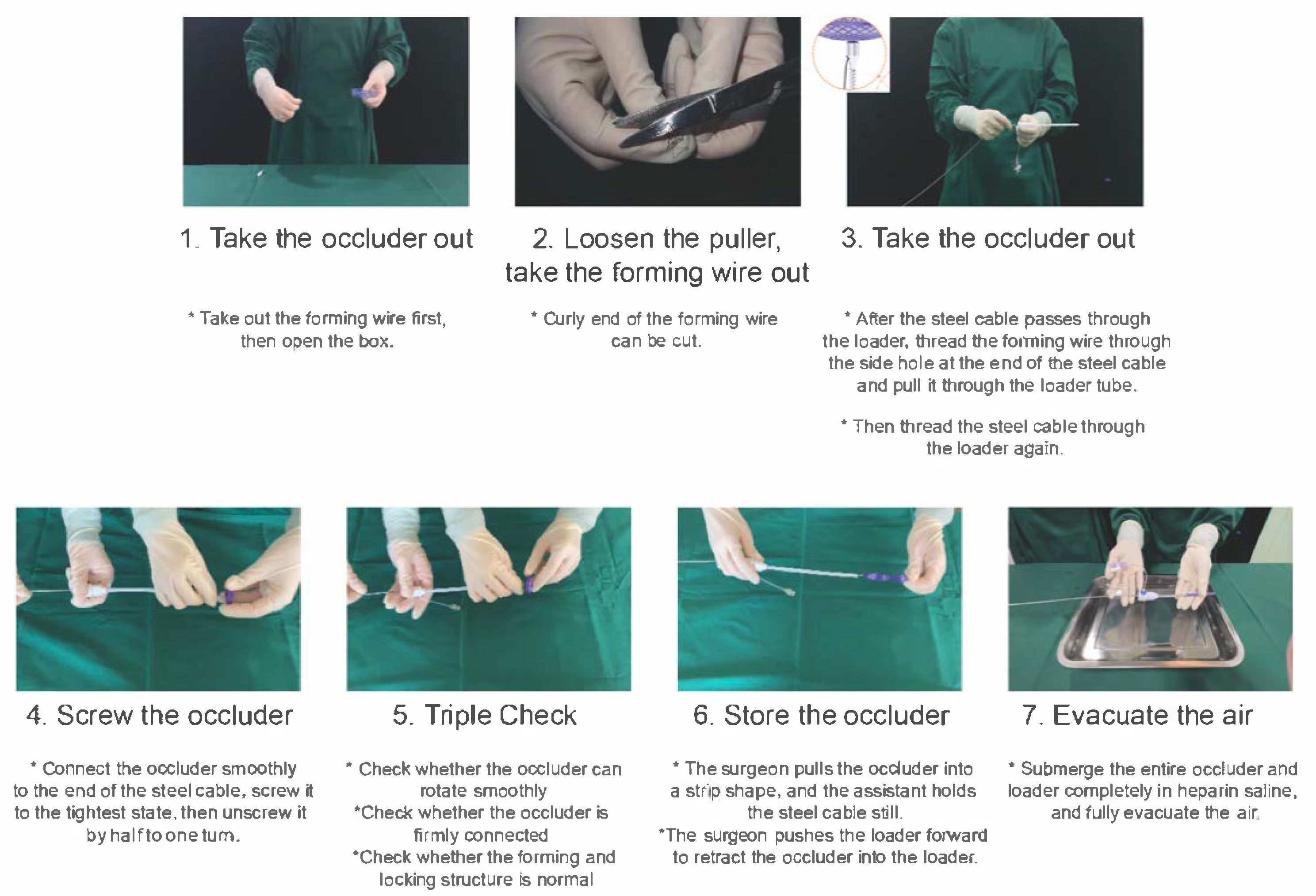

- (7)In-vitro loading and testing of the degradable occluder: Prepare the occluder according to manufactory instructions. Perform heparinized saline flushes 3–5 cycles. Maintain complete immersion until deployment. The delivery cable is inserted from the side of the sealing ring until it reaches the tip of the loader. The sterile package of the occluder is opened, and the two forming wires are cut along the front of the plastic control handle at the tail end. After knotting, the wire ends are threaded through the side hole of the delivery cable. The delivery cable is then retracted beyond the sealing ring to draw out the forming wires, following which it is reinserted from the side of the sealing ring and advanced to the tip of the loader. The screw on the right atrial disc side of the occluder is aligned with the nut at the tip of the delivery cable, and the assembly is rotated to lock until it reaches the root of the occluder’s right disc (note: the screw threads should be neither overly loose nor excessively tight). The loader is retracted along the delivery cable to the middle-posterior segment of the cable. Starting from the threading side hole adjacent to the nut at the cable head, the two forming wires are separated to form parallel strands without crossing or entanglement. With one hand pulling the wires, the other hand advances the loader to the base of the right disc of the occluder at the cable tip. The two forming wires are then re-separated from the side of the loader’s sealing ring, maintaining parallel alignment without crossing or entanglement until reaching the knotted end of the wires, thus completing the wire separation process. After reconfirming that no entanglement exists between the forming wires and the screw, the delivery cable is retracted to allow the tip of the loader catheter to abut the umbrella disc on the right atrial side of the occluder. The delivery cable is gently advanced, the loader is secured with the left hand, and the forming wires are pulled posteriorly parallel to the cable with the right hand to lock the occluder’s dual discs. A distinct “click” sound or a palpable vibration in the right hand during wire pulling indicates that the in vitro locking function of the occluder is intact and suitable for use; otherwise, the occluder should be replaced with a new one. Once the dual discs are locked, the forming wires are pulled separately with the left and right hands to test for smooth sliding. If resistance is encountered during wire pulling, it suggests either entanglement of the forming wires or knot malfunction, necessitating troubleshooting or occluder replacement. Upon completion of in vitro loading and testing, both hands are used to pull the left and right discs, unlocking the fastener into a spindle shape. The assistant then retracts the delivery cable to retract the occluder into the loader. The entire loader is immersed in a heparinized saline basin and rinsed repeatedly 3–5 times using a 50 mL syringe. After thorough deairing, the assembly is kept immersed in heparinized saline for subsequent use. The loading process and precautions for the biodegradable PFO occluder are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Loading Process and Precautions for Biodegradable PFO Occluder. PFO, Patent Foramen Ovale.

- (8)Deploying the occluder: Under continuous echocardiographic guidance (TTE aortic short-axis or apical four-chamber view), advance the pre-loaded biodegradable PFO occluder through the delivery sheath. Gradually push the occluder until the left atrial disk emerges from the sheath. Apply gentle tension on the external forming wires to facilitate proper disk expansion. Simultaneously retract both sheath and cable to seat the left disk against the atrial septum. Stabilize the cable while withdrawing the sheath to deploy the right atrial disk. Gently advance both cable and sheath to optimize right disk-septal contact.

- (9)Determination of the occluder positions and push-pull test: Perform gentle push-pull maneuvers on the cable while monitoring with TTE. Observe disk behavior in multiple views (aortic short-axis, apical four-chamber, and subxiphoid bi-atrial): right-atrial disk should thicken and assume spherical shape. Left-atrial disk position remains stable without deformation. Verify proper positioning as both disks must be secured on opposite sides of the atrial septum. No interference with mitral valve, tricuspid valve, or atrial roof. Proceed to locking only after confirming optimal occluder position.

- (10)Occluder locking procedure: Verify the final position using TTE (aortic short-axis, apical four-chamber, and subxiphoid views). Confirm proper occluder positioning without impingement on mitral valve apparatus, pulmonary vein orifices, coronary sinus. Verify optimal disk morphology and septal alignment. Perform the locking Maneuver following manufactory instructions.

- (11)Pre-release testing after occluder locking: After locking the double disks, perform a final push-pull test under echocardiographic monitoring (apical four-chamber, aortic short-axis, and subxiphoid bi-atrial views). Gently pull the cable to confirm no deformation of the occluder disks, and slight synchronous movement of both disks with the atrial septum. Final echocardiographic assessments include stable occluder shape and position during push-pull testing; no significant atrial septal shunt on Doppler ultrasound contrast study; inject 15–20 mL of agitated saline via the delivery sheath if needed, confirm no significant right-to-left shunt (≤grade I). If shunt > grade I exists, apply stronger traction on the forming wires to improve disk apposition until shunt resolution. Only proceed with wire cutting and occluder release after all criteria are met.

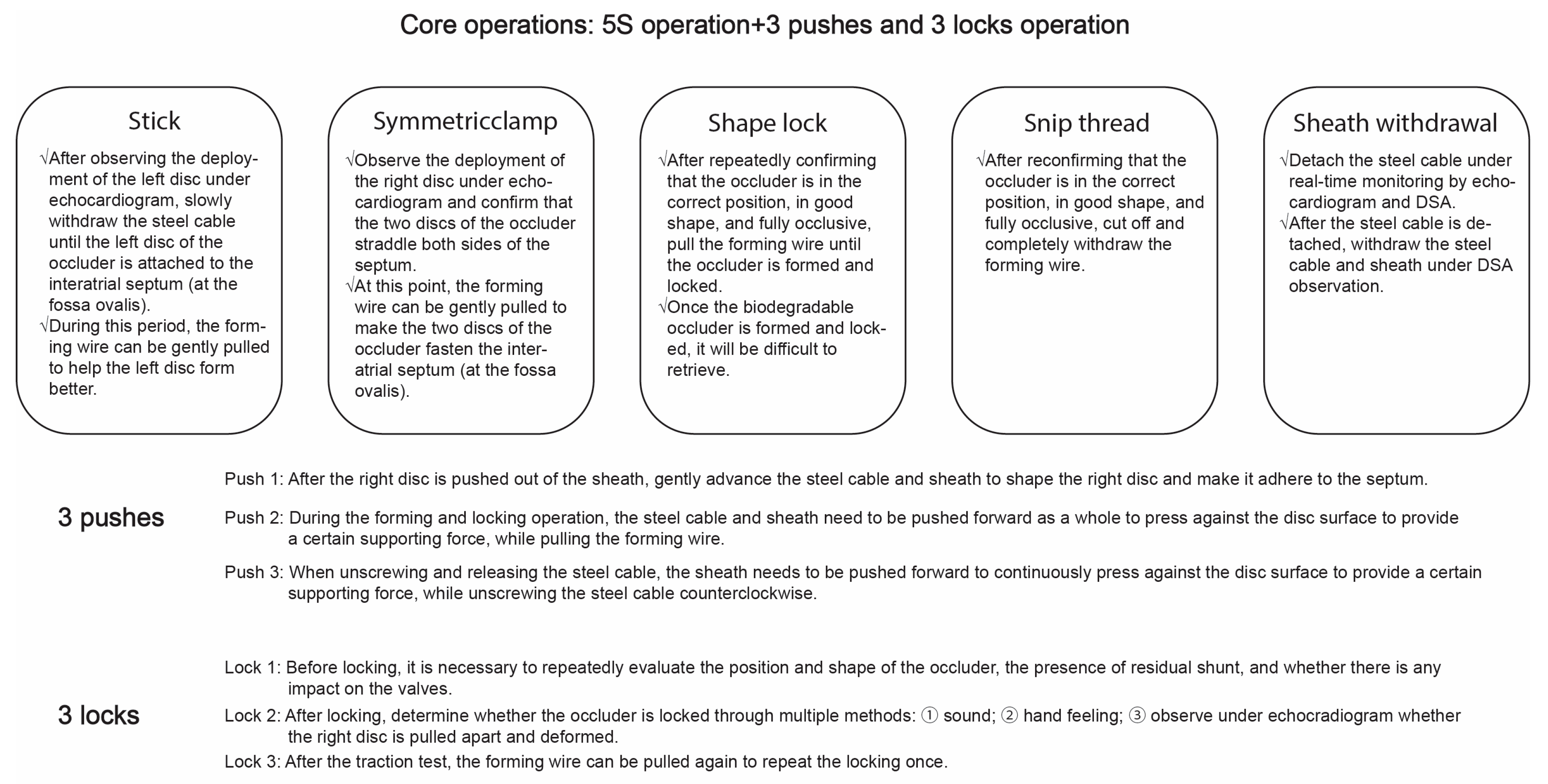

- (12)Releasing the occluder: After confirming that the occluder is locked successfully through the above-mentioned tests, remove the forming wires after transecting. Then, push the sheath forward to press tightly against the disk surface of the occluder, and gently rotate the delivery cable counter-clockwise to release the occluder. The interventional operation specifications and precautions of the biodegradable PFO occluder are shown in Fig. 2.

- (13)Retract the delivery sheath, press the puncture point, and bandage it with pressure.

Figure 2: Operative Specifications and Precautions for Interventional Use of Biodegradable PFO Occluder. PFO, Patent Foramen Ovale.

5.2 Combined X-Ray and Echocardiography-Guided Percutaneous Implantation of Biodegradable PFO Occluders

- (1)Intraoperative echocardiographic monitoring: Use TTE to evaluate the atrial septal morphology and pericardial space as baseline references, and prepare appropriately sized occluders based on preoperative TEE and TTE measurements (occluder selection criteria remain consistent with the previous mentioned principles).

- (2)Approach: Perform femoral vein puncture under standard local anesthesia and conduct right-heart catheterization to exclude pulmonary hypertension.

- (3)Under X-ray fluoroscopy, use a guidewire with MPA catheter to probe and traverse the PFO. Administer intravenous heparin 100 U/kg. Adjust the guidewire and catheter, advance the guidewire into the left upper pulmonary vein. Exchange for a super-stiff guidewire positioned in the left upper pulmonary vein.

- (4)Delivery sheath selection and insertion: The principle is the same as previously described.

- (5)In-vitro loading and testing of the degradable occluder: The steps are the same as previously described.

- (6)Under X-ray fluoroscopy and echocardiographic monitoring, advance the preloaded biodegradable PFO occluder through the delivery sheath. Four platinum markers are visible under fluoroscopy: The first marker on the left-atrial disk. The second and third markers at the occluder waist. The fourth marker on the right-atrial disk. The markers sequentially advance through the sheath. When the first marker exits the sheath tip while the second and third markers align with the sheath edge, this indicates left-atrial disk deployment. Gently tension the external forming wires to approximate the first three markers while monitoring left-disk formation echocardiographically (TTE/TEE). Simultaneously withdraw the sheath and cable while maintaining wire tension to seat the left disk against the septum. Then stabilize the cable and retract the sheath to deploy the right disk, observing the fourth marker’s emergence under fluoroscopy. Finally, gently advance both cable and sheath to converge all four markers.

- (7)Determination of the double disk positions: Gently retract the cable while monitoring with echocardiography. In the aortic short-axis, apical four-chamber, and subxiphoid bi-atrial views, observe the right-atrial disk deforming while the left-atrial disk maintains its position and shape. This confirms proper bilateral septal disk apposition rather than unilateral positioning.

- (8)Occluder locking procedure: Under repeated echocardiographic and fluoroscopic confirmation of proper occluder position, optimal morphology, and absence of atrioventricular valve interference, gently advance both the cable and delivery sheath against the right-atrial disk while maintaining firm coaxial backward traction on the forming wires until complete disk locking is achieved (following manufactory instructions). Following successful locking, fluoroscopic evaluation in the 50–60 degree left anterior oblique projection (septal tangential view) demonstrates convergence of the four imaging markers from initial dispersion into a compact square or parallelogram configuration.

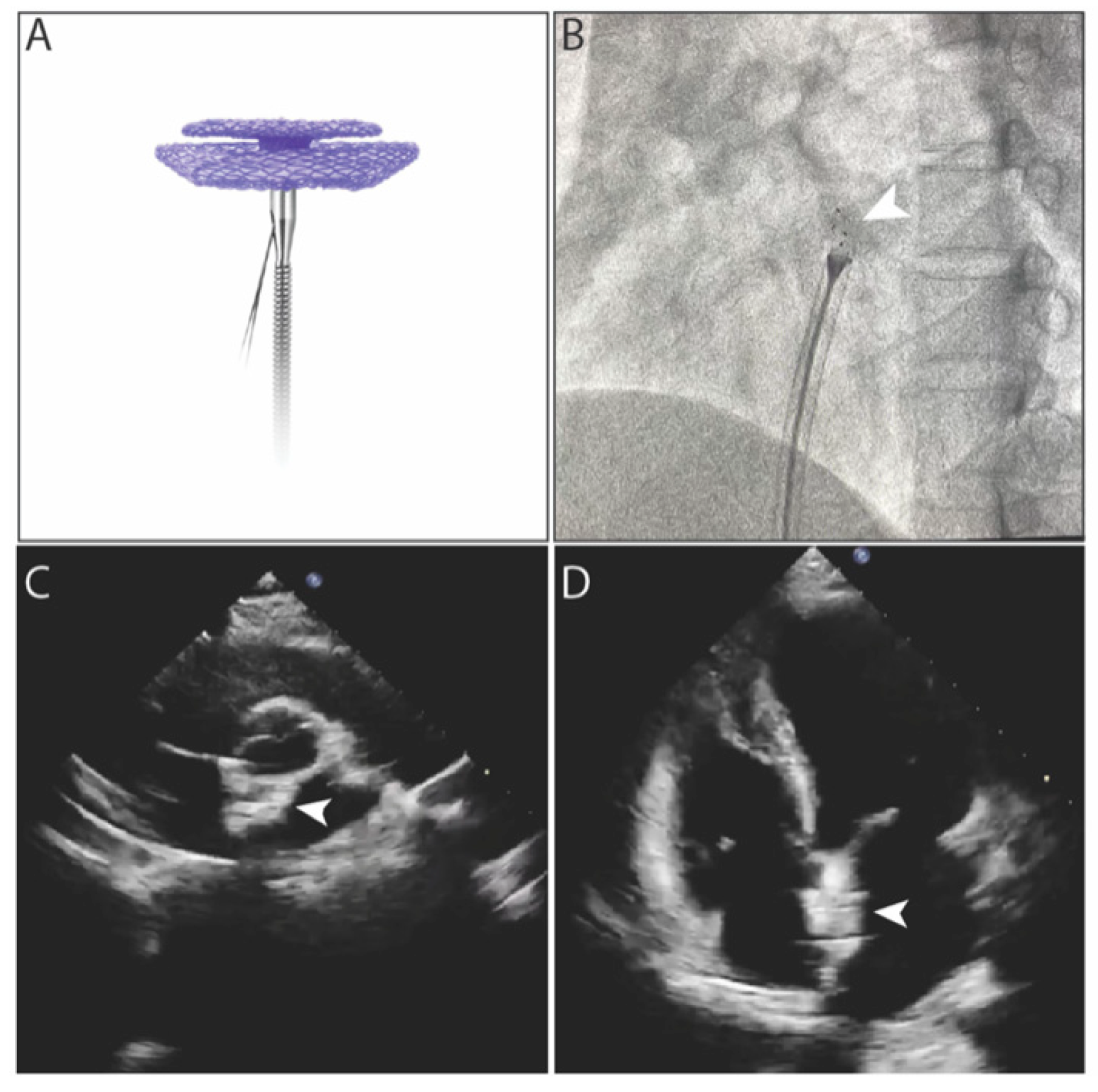

- (9)Pre-release testing after occluder locking: After locking the double disks, perform another push-pull test under X-ray fluoroscopy by gently pulling the cable to confirm the four imaging points move synchronously (asynchronous movement indicates incomplete locking) while maintaining convergence. Simultaneously verify through echocardiography that the occluder maintains proper shape and position during push-pull testing across multiple views, with no significant atrial-septal shunt on Doppler ultrasound, confirming successful locking. Administer 15–20 mL of agitated saline via forceful injection through the delivery sheath for right-heart contrast echocardiography if needed; absence of significant right-to-left shunt (if grade I or greater shunt persists, apply additional tension to the forming wires to enhance disk locking until shunt resolution) further confirms locking success (Fig. A1 presents the images of biodegradable PFO occluder under fluoroscopy and echocardiography separately).

- (10)Releasing the occluder: After confirming successful locking and echocardiographic verification of proper occluder position and morphology, remove the forming wires after transecting. Subsequently, advance the sheath firmly against the occluder disk surface while applying gentle counterclockwise rotation to the delivery cable to achieve final device release.

- (11)Retract the delivery sheath, press the puncture point, and bandage it with pressure.

6 Postoperative Management and Follow–Up

The patient should remain in bed for approximately 12 h postoperatively. Medication regimen: Administer low-molecular-weight heparin as needed within the first 24 h to prevent thrombosis. Implement dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg/d plus clopidogrel 75 mg/d) for 6 months post-procedure, followed by single-agent antiplatelet therapy, either aspirin 100 mg/d or clopidogrel 75 mg/d, for an additional 6 months [4,48,49,50,51,52,53]. For patients with elevated thromboembolic or bleeding risks, individualize treatment duration (either extending or reducing) and adjust medication dosages accordingly. Patients with atrial fibrillation should receive novel oral anticoagulants or warfarin. Those intolerant or unsuitable for antiplatelet therapy require personalized anticoagulation plans [5,54].

Postoperative follow-up: It is recommended to perform echocardiography and electrocardiography at 24 h, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months postoperatively, and annually thereafter. If indicated, conduct cTTE or cTCD to assess for residual right-to-left shunt. For moderate-to-large residual shunts, maintain follow-up surveillance and prioritize TEE evaluation to localize the shunt origin (distinguishing between undetected defects, alternative pathways, or iatrogenic transseptal puncture). During follow-up, systematically evaluate clinical symptom improvement (using migraine assessment scales and cranial MRI findings).

7 Complication Identification and Prevention

7.1 Cardiac Perforation and Tamponade Management

The incidence of cardiac perforation during PFO interventional closure is 0.5–1.0%. The most common perforation site during the procedure is the left atrial appendage. Other locations-including the right ventricle, right atrium, and pulmonary vein-are considerably less common [55]. Atrial septal dissection or entry into the pericardium through the transverse sinus may occur when catheter/wire passage through the PFO proves technically challenging or when operator experience is limited. The risk of cardiac perforation appears reduced following biodegradable occluder implantation, with no reported cases to date. Prophylactic heparin administration after left upper pulmonary vein guidewire placement helps prevent acute pericardial tamponade secondary to cardiac perforation. Critical management priorities include: timely pericardial effusion detection prior to tamponade development; immediate echocardiography for intraoperative chest tightness when effusion is suspected; observation for minor effusions with stable vital signs; emergency pericardiocentesis for moderate-to-large effusions causing tamponade; exploratory thoracotomy if effusion persists despite intervention.

7.2 Device Migration and Embolization

Device embolization is rare. However, when it occurs, patients may experience palpitations, chest tightness, or arrhythmia. Strict procedural precautions are essential to mitigate risks. Intraprocedural echocardiography and pre-release reevaluation are critical. If transthoracic acoustic windows are suboptimal, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) should be utilized to assess septal morphology. The procedure must be performed with standardized and precise techniques, and an appropriately occluder should be selected. If the occluder is pulled into the right atrium during the procedure, retrieval is recommended. In cases of difficult retrieval, gently shaking the cable may help loosen the forming wires and left atrial disk.

If embolization occurs, the occluder’s position should be localized using fluoroscopy, angiography, or ultrasound. If localization remains challenging, aortic CTA or delayed scanning may be performed to determine the exact embolization site. Initial retrieval attempts should employ a snare, followed by extraction through the largest feasible sheath. If interventional retrieval fails or is deemed high-risk, surgical removal of the occluder and PFO repair are recommended.

During right-heart catheterization and occlusion, incomplete air evacuation may allow air to enter the right or left atrium through the catheter or delivery sheath, potentially causing air embolism. Right coronary artery air embolism occurs most frequently, typically manifesting as transient intraprocedural ST-segment elevation, sinus bradycardia, or atrioventricular block. Patients may experience mild symptoms such as chest tightness and bradycardia; those with significant ST-segment elevation may present with chest discomfort, pallor, diaphoresis, nausea, and vomiting, accompanied by sinus bradycardia. The primary preventive method involves thorough air evacuation during the procedure [55], minimizing air entry into the closed delivery system. The occluder should be vigorously flushed in vitro using a 50-mL syringe under high pressure until no bubbles remaining in the loading sheath. Following delivery sheath placement in the left atrium, the inner core should be withdrawn slowly while simultaneously performing gentle aspiration and air evacuation through the sheath’s hemostatic valve. Occluder loading into the delivery sheath should be performed in a water-filled tray with gentle advancement to minimize air entrapment. For suspected air embolism, immediate procedural cessation is mandatory, followed by rapid assessment of airway and respiratory status. Supportive treatments include high-flow oxygen administration, heart rate augmentation, mechanical ventilation, intravenous fluid administration, vasopressor support, and advanced life support when indicated.

7.4 Arrhythmia/Atrial Fibrillation

Transient atrial arrhythmias following PFO occlusion are relatively common, with atrial fibrillation being most prevalent (incidence: 4.6%–6.6%) [2,3,56]. Current research and meta-analyses demonstrate a significantly increased incidence of atrial fibrillation post-PFO closure [56,57,58,59,60]. The mechanism of perioperative atrial fibrillation and flutter remains unclear but may be associated with occluder selection. Biodegradable PFO occluders, composed of softer biopolymer materials with reduced mechanical traction forces, may potentially decrease atrial fibrillation incidence. When atrial fibrillation occurs with metal occluders, the majority of cases are transient or paroxysmal, typically occurring within 45 postoperative days. Most patients maintain sinus rhythm with pharmacological treatment. Consequently, the clinical significance of post-PFO closure atrial fibrillation appears limited, particularly when using biodegradable occluders which demonstrate even lower arrhythmia rates.

Theoretically, atrial-level shunting should cease after PFO occlusion. Potential mechanisms for residual shunt following biodegradable PFO occluder implantation include: (1) incomplete device locking, which may compromise wall apposition and endothelialization, permitting blood flow through occluder interstices; (2) undiagnosed small atrial septal defects or multiple PFOs; (3) presence of small pulmonary-venous fistulae; or (4) procedural creation of iatrogenic atrial communication when guidewires or catheters inadvertently bypass the true PFO tract.

For patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms 6–12 months post-procedure, timely bubble study evaluation is recommended to identify residual shunting, with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) serving as the diagnostic confirmatory test.

This is rare and is caused by insufficient anticoagulation and anti-platelet treatment. If a thrombus forms on the left-atrial side of the occluder, it can cause systemic thromboembolism, including peripheral arterial embolism and retinal arterial embolism. The framework of biodegradable PFO occluders is composed of poly(p-dioxanone) (PDO). Compared with nickel-alloy occluders, biodegradable PFO occluders have better biocompatibility, which can significantly reduce the inflammatory response, relieve fibrosis, and promote endothelialization [56], reducing the occurrence of thromboembolism to a certain extent. Once a thrombus is detected, anticoagulation treatment should be strengthened. If the thrombus has a large mobility and there is a risk of embolization, it is recommended to surgically remove the occluder and repair PFO.

7.7 General Interventional Complications

These include anesthesia accidents, wound infections, femoral arteriovenous fistulas, and femoral artery pseudoaneurysms.

The new PFO occluder in China is currently the world’s first biodegradable PFO occluder launched and officially used in clinical practice. Relevant professional interventional physicians should strictly master the indications for interventional occlusion, conduct comprehensive preoperative examinations, give full play to the role of MDT, perform standardized operations during the operation, and conduct strict follow-up observations after the operation to further improve the success rate of PFO occlusion, reduce the occurrence of serious complications, and benefit more patients suitable for PFO occlusion.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Fuwai Hospital High Level Hospital clinical research fund (2022-GSPGG-18).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Xiangbin Pan; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, Caojin Zhang, Haibo Hu, Gangcheng Zhang; translation, Xuan Zheng; writing—review and editing, Caojin Zhang, Haibo Hu, Gangcheng Zhang, Qiguang Wang, Xiaobin Chen, Yingzhang Cheng, Qunshan Shen, Jie Yuan, Wenqi Zhang, Yuanshi Li, Xuan Zheng, Xiangbin Pan, Professional Committee of National Quality Management and Control Center for Structural Heart Diseases, Professional Committee of Structural Heart Diseases of the National Cardiovascular Disease Expert Committee; funding acquisition, Xiangbin Pan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Figure A1: Images of biodegradable PFO occluder. (A) Biodegradable PFO occulder connected with steel cable; (B) Locking process under fluoroscopy. Arrow indicates the metal markers in occluder. (C,D) Biodegradable PFO occulder under echocardiography after deployment. Arrows indicate the occluder.

References

1. Mas JL, Derumeaux G, Guillon B, Massardier E, Hosseini H, Mechtouff L, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure or anticoagulation vs. antiplatelets after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(11):1011–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1705915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Saver JL, Carroll JD, Thaler DE, Smalling RW, MacDonald LA, Marks DS, et al. Long-term outcomes of patent foramen ovale closure or medical therapy after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(11):1022–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Søndergaard L, Kasner SE, Rhodes JF, Andersen G, Iversen HK, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure or antiplatelet therapy for cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(11):1033–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1707404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lee PH, Song JK, Kim JS, Heo R, Lee S, Kim DH, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and high-risk patent foramen ovale: the DEFENSE-PFO trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(20):2335–42. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology, Chen S, Chen M, Han Y. Chinese expert consensus on the standardized diagnosis and treatment of patent foramen ovale. Chin J Cardiol. 2024;52(4):369–83. (In Chinese). doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20231030-00393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang C, Hu H, Wang Q. Standardized diagnosis and treatment of patent foramen ovale: from guidelines to practice. Beijing, China: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2024. [Google Scholar]

7. Chessa M, Carminati M, Butera G, Bini RM, Drago M, Rosti L, et al. Early and late complications associated with transcatheter occlusion of secundum atrial septal defect. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(6):1061–5. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01711-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Krumsdorf U, Ostermayer S, Billinger K, Trepels T, Zadan E, Horvath K, et al. Incidence and clinical course of thrombus formation on atrial septal defect and patient foramen ovale closure devices in 1000 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(2):302–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Iskander B, Anwer F, Oliveri F, Fotios K, Panday P, Arcia Franchini AP, et al. Amplatzer patent foramen ovale occluder device-related complications. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e23756. doi:10.7759/cureus.23756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kashyap T, Sanusi M, Momin ES, Khan AA, Mannan V, Pervaiz MA, et al. Transcatheter occluder devices for the closure of atrial septal defect in children: how safe and effective are they? A systematic review. Cureus. 2022;14(5):e25402. doi:10.7759/cureus.25402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lin C, Liu L, Liu Y, Leng J. Recent developments in next-generation occlusion devices. Acta Biomater. 2021;128:100–19. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2021.04.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Werner RS, Prêtre R, Maisano F, Wilhelm MJ. Fracture of a transcatheter atrial septal defect occluder device causing mitral valve perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108(1):e29–30. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.11.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shi D, Kang Y, Zhang G, Gao C, Lu W, Zou H, et al. Biodegradable atrial septal defect occluders: a current review. Acta Biomater. 2019;96:68–80. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Uzun N, Martins TD, Teixeira GM, Cunha NL, Oliveira RB, Nassar EJ, et al. Poly(L-lactic acid) membranes: absence of genotoxic hazard and potential for drug delivery. Toxicol Lett. 2015;232(2):513–8. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.11.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Thomas V, Zhang X, Vohra YK. A biomimetic tubular scaffold with spatially designed nanofibers of protein/PDS bio-blends. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;104(5):1025–33. doi:10.1002/bit.22467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Huang XM, Zhu YF, Cao J, Hu JQ, Bai Y, Jiang HB, et al. Development and preclinical evaluation of a biodegradable ventricular septal defect occluder. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81(2):324–30. doi:10.1002/ccd.24580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Duong-Hong D, Tang YD, Wu W, Venkatraman SS, Boey F, Lim J, et al. Fully biodegradable septal defect occluder-a double umbrella design. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76(5):711–8. doi:10.1002/ccd.22735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wu W, Yip J, Tang YD, Khoo V, Kong JF, Duong-Hong D, et al. A novel biodegradable septal defect occluder: the “Chinese Lantern” design, proof of concept. Innovations. 2011;6(4):221–30. doi:10.1097/IMI.0b013e31822a2c42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu SJ, Peng KM, Hsiao CY, Liu KS, Chung HT, Chen JK. Novel biodegradable polycaprolactone occlusion device combining nanofibrous PLGA/collagen membrane for closure of atrial septal defect (ASD). Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39(11):2759–66. doi:10.1007/s10439-011-0368-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Du Y, Xie H, Shao H, Cheng G, Wang X, He X, et al. A prospective, single-center, phase I clinical trial to evaluate the value of transesophageal echocardiography in the closure of patent foramen ovale with a novel biodegradable occluder. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:849459. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.849459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lu W, Ouyang W, Wang S, Liu Y, Zhang F, Wang W, et al. A novel totally biodegradable device for effective atrial septal defect closure: a 2-year study in sheep. J Interv Cardiol. 2018;31(6):841–8. doi:10.1111/joic.12550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xie ZF, Wang SS, Zhang ZW, Zhuang J, Liu XD, Chen XM, et al. A novel-design poly-L-lactic acid biodegradable device for closure of atrial septal defect: long-term results in swine. Cardiology. 2016;135(3):179–87. doi:10.1159/000446313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dürselen L, Dauner M, Hierlemann H, Planck H, Claes LE, Ignatius A. Resorbable polymer fibers for ligament augmentation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;58(6):666–72. doi:10.1002/jbm.1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li Y, Xie Y, Li B, Xie Z, Shen J, Wang S, et al. Initial clinical experience with the biodegradable absnowTM device for percutaneous closure of atrial septal defect: a 3-year follow-up. J Interv Cardiol. 2021;2021:6369493. doi:10.1155/2021/6369493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang Y, Li G, Yang L, Luo R, Guo G. Development of innovative biomaterials and devices for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Adv Mater. 2022;34(46):e2201971. doi:10.1002/adma.202201971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xu Q, Fa H, Yang P, Wang Q, Xing Q. Progress of biodegradable polymer application in cardiac occluders. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2024;112(1):e35351. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.35351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ulery BD, Nair LS, Laurencin CT. Biomedical applications of biodegradable polymers. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys. 2011;49(12):832–64. doi:10.1002/polb.22259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ping Ooi C, Cameron RE. The hydrolytic degradation of polydioxanone (PDSII) sutures. Part I: morphological aspects. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63(3):280–90. doi:10.1002/jbm.10180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cao Y, Yin J, Yan S. Recent research advance in biodegradable poly(lactic acid) (PLA): modification and application. Polym Bull. 2006;84(10):90–7. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-3726.2006.10.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. da Silva D, Kaduri M, Poley M, Adir O, Krinsky N, Shainsky-Roitman J, et al. Biocompatibility, biodegradation and excretion of polylactic acid (PLA) in medical implants and theranostic systems. Chem Eng J. 2018;340:9–14. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2018.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bartnikowski M, Dargaville TR, Ivanovski S, Hutmacher DW. Degradation mechanisms of polycaprolactone in the context of chemistry, geometry and environment. Prog Polym Sci. 2019;96:1–20. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Guo G, Hu J, Wang F, Fu D, Luo R, Zhang F, et al. A fully degradable transcatheter ventricular septal defect occluder: towards rapid occlusion and post-regeneration absorption. Biomaterials. 2022;291:121909. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li BN, Xie YM, Xie ZF, Chen XM, Zhang G, Zhang DY, et al. Study of biodegradable occluder of atrial septal defect in a porcine model. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93(1):E38–45. doi:10.1002/ccd.27852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chen L, Hu S, Luo Z, Butera G, Cao Q, Zhang F, et al. First-in-human experience with a novel fully bioabsorbable occluder for ventricular septal defect. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(9):1139–41. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2019.09.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Rong JJ, Sang HF, Qian AM, Meng QY, Zhao TJ, Li XQ. Biocompatibility of porcine small intestinal submucosa and rat endothelial progenitor cells in vitro. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(2):1282–91. [Google Scholar]

37. Jux C, Bertram H, Wohlsein P, Bruegmann M, Paul T. Interventional atrial septal defect closure using a totally bioresorbable occluder matrix: development and preclinical evaluation of the BioSTAR device. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(1):161–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Pavcnik D, Takulve K, Uchida BT, Pavcnik Arnol M, VanAlstine W, Keller F, et al. Biodisk: a new device for closure of patent foramen ovale: a feasibility study in swine. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75(6):861–7. doi:10.1002/ccd.22429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Huang YY, Wong YS, Chan JN, Venkatraman SS. A fully biodegradable patent ductus arteriosus occlude. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2015;26(2):93. doi:10.1007/s10856-015-5422-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Belgrave K, Cardozo S. Thrombus formation on amplatzer septal occluder device: pinning down the cause. Case Rep Cardiol. 2014;2014:457850. doi:10.1155/2014/457850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wein T, Lindsay MP, Côté R, Foley N, Berlingieri J, Bhogal S, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: secondary prevention of stroke, sixth edition practice guidelines, update 2017. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(4):420–43. doi:10.1177/1747493017743062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kuijpers T, Spencer FA, Siemieniuk RAC, Vandvik PO, Otto CM, Lytvyn L, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure, antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation therapy alone for management of cryptogenic stroke? A clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2018;362:k2515. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Pristipino C, Sievert H, D’Ascenzo F, Louis Mas J, Meier B, Scacciatella P, et al. European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism. EuroIntervention. 2019;14(13):1389–402. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Messé SR, Gronseth GS, Kent DM, Kizer JR, Homma S, Rosterman L, et al. Practice advisory update summary: patent foramen ovale and secondary stroke prevention: report of the guideline subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2020;94(20):876–85. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, Cockroft KM, Gutierrez J, Lombardi-Hill D, et al. 2021 guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52(7):e364–467. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Kavinsky CJ, Szerlip M, Goldsweig AM, Amin Z, Boudoulas KD, Carroll JD, et al. SCAI guidelines for the management of patent foramen ovale. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2022;1(4):100039. doi:10.1016/j.jscai.2022.100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Chinese Society of Neurology, Chinese Stroke Society, Wang Y, Zeng J. Chinese guideline for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack 2022. Chin J Neurol. 2022;55(10):1071–110. (In Chinese). doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn113694-20220714-00548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Caso V, Turc G, Abdul-Rahim AH, Castro P, Hussain S, Lal A, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patent foramen ovale (PFO) after stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2024;9(4):800–34. doi:10.1177/23969873241247978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Song L, Shi P, Zheng X, Li H, Li Z, Lv M, et al. Echocardiographic characteristics of transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale with mallow biodegradable occluder: a single-center, phase III clinical study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:945275. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.945275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Van den Branden BJ, Post MC, Plokker HW, ten Berg JM, Suttorp MJ. Patent foramen ovale closure using a bioabsorbable closure device: safety and efficacy at 6-month follow-up. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3(9):968–73. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2010.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Dowson A, Mullen MJ, Peatfield R, Muir K, Khan AA, Wells C, et al. Migraine Intervention with STARFlex Technology (MIST) trial: a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, sham-controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of patent foramen ovale closure with STARFlex septal repair implant to resolve refractory migraine headache. Circulation. 2008;117(11):1397–404. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Mattle HP, Evers S, Hildick-Smith D, Becker WJ, Baumgartner H, Chataway J, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in migraine with aura, a randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(26):2029–36. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Li B, Xie Z, Wang Q, Chen X, Liu Q, Wang W, et al. Biodegradable polymeric occluder for closure of atrial septal defect with interventional treatment of cardiovascular disease. Biomaterials. 2021;274:120851. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Anticoagulant Pharmacist Specialist Collaboration Group, Cardiovascular Pharmacy Branch of Chinese Society of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. Pharmaceutical recommendation on rational use and the prescription quality evaluation of direct oral anticoagulants. Chin Cir. 2024;39(3):217–27. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2024.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Amin Z, Hijazi ZM, Bass JL, Cheatham JP, Hellenbrand WE, Kleinman CS. Erosion of Amplatzer septal occluder device after closure of secundum atrial septal defects: review of registry of complications and recommendations to minimize future risk. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;63(4):496–502. doi:10.1002/ccd.20211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Chen JZ, Thijs VN. Atrial fibrillation following patent foramen ovale closure: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and clinical trials. Stroke. 2021;52(5):1653–61. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Mullen MJ, Hildick-Smith D, De Giovanni JV, Duke C, Hillis WS, Morrison WL, et al. BioSTAR Evaluation STudy (BEST): a prospective, multicenter, phase I clinical trial to evaluate the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of the BioSTAR bioabsorbable septal repair implant for the closure of atrial-level shunts. Circulation. 2006;114(18):1962–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Shah R, Nayyar M, Jovin IS, Rashid A, Bondy BR, Fan TM, et al. Device closure versus medical therapy alone for patent foramen ovale in patients with cryptogenic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):335–42. doi:10.7326/M17-2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Ahmad Y, Howard JP, Arnold A, Shin MS, Cook C, Petraco R, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure vs. medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(18):1638–49. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Li Z, Kong P, Liu X, Feng S, Ouyang W, Wang S, et al. A fully biodegradable polydioxanone occluder for ventricle septal defect closure. Bioact Mater. 2023;24:252–62. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools