Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

Persistent Left Superior Vena Cava with Severely Dilated Coronary Sinus: A Rare Case Report of Failed CRT-P and Successful Dual-Chamber Pacemaker Implantation

1 Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Alkharj, 11942, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Cardiology, King Saud Medical City Hospital, Riyadh, 12746, Saudi Arabia

3 College of Medicine, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Alkharj, 11942, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Nasser Alotaibi. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(5), 539-546. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.071226

Received 02 August 2025; Accepted 04 November 2025; Issue published 30 November 2025

Abstract

Persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC) is a rare congenital anomaly that may complicate cardiac procedures when associated with a dilated coronary sinus (CS) and conduction disturbances. We report the case of a 27-year-old male with Wilson’s disease who presented with complete heart block. Echocardiography showed biatrial enlargement and severe CS dilation, while contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) confirmed PLSVC draining into the CS without a bridging vein. Anatomical constraints prevented cardiac resynchronization therapy, and dual-chamber pacemaker implantation proved technically challenging due to lead placement difficulties. This case highlights the importance of thorough preoperative assessment and individualized pacing strategies in patients with PLSVC, in order to anticipate anatomical challenges and optimize outcomes.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FilePersistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC) is a rare but clinically significant anomaly, with a prevalence of approximately 0.3–0.5% in the general population and 4–8% in patients with congenital heart disease [1]. PLSVC is usually asymptomatic, often discovered incidentally, and results from the failure of regression of the left common cardinal vein during embryonic development. It drains blood from the left subclavian and jugular veins into the right atrium via the coronary sinus (CS) [2].

The CS, the most prominent cardiac venous structure, plays a vital role in returning deoxygenated blood from the myocardium to the right atrium [3]. Congenital anomalies of the CS are exceedingly rare and are frequently associated with superior vena cava (SVC) anomalies [4]. The presence of such anomalies can be hazardous, highlighting the need for early identifications to avoid procedural complications [5].

In this report, we present a unique case of a young patient with a known diagnosis of Wilson’s disease, who was found to have PLSVC accompanied by dilated CS and complete heart block (CHB), highlighting its clinical and anatomical significance.

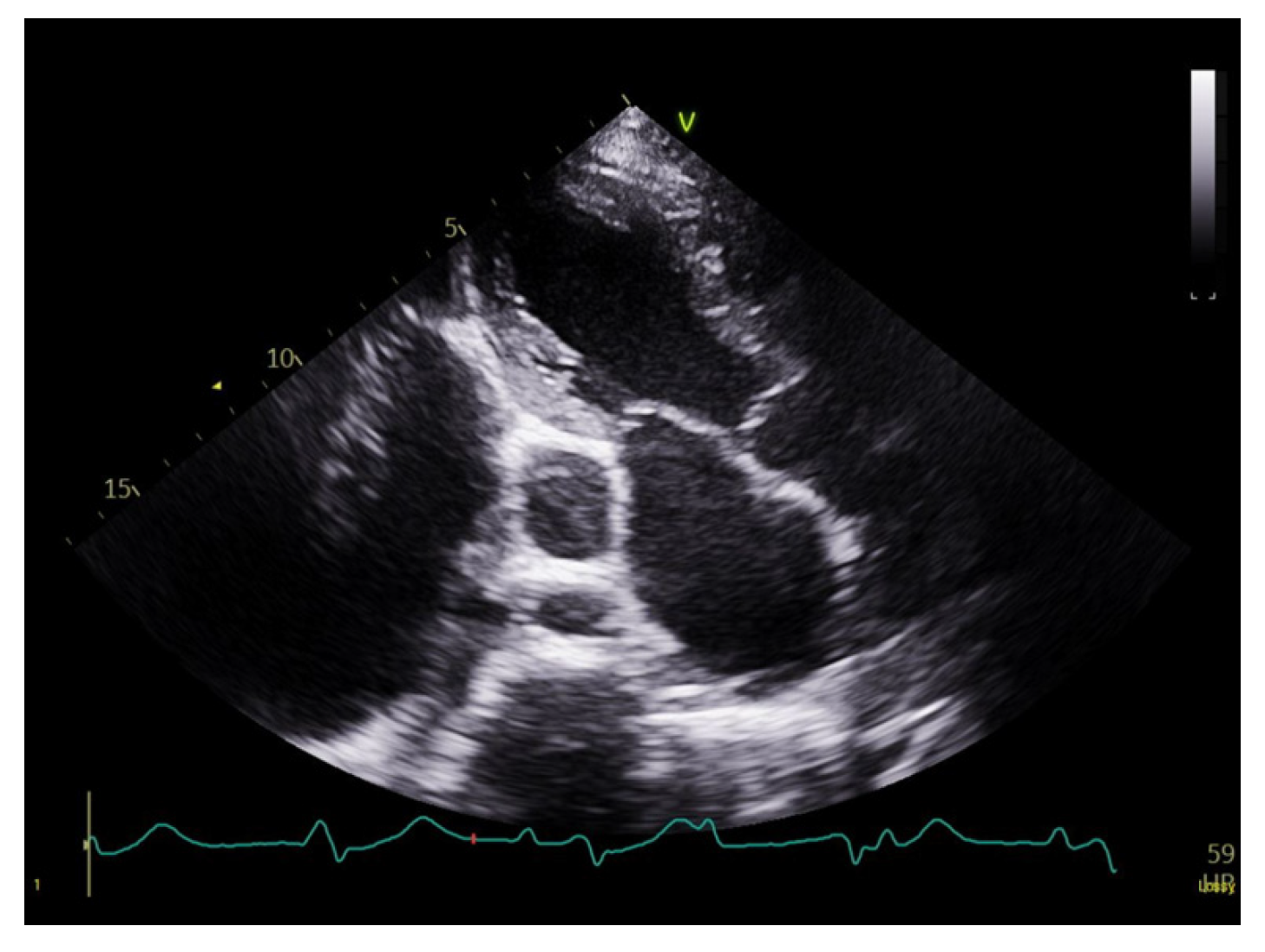

A 27-year-old Bengali male with a known history of Wilson’s disease presented to the emergency department with dyspnea, fatigue, and chest discomfort. Initial diagnostic work-up included an electrocardiogram (ECG), which revealed complete heart block with an escape rhythm at approximately 40 beats per minute. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed biatrial dilation, a severely dilated CS, mild left ventricular (LV) dilation, and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 45% (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Transthoracic echocardiography showing a severely dilated coronary sinus.

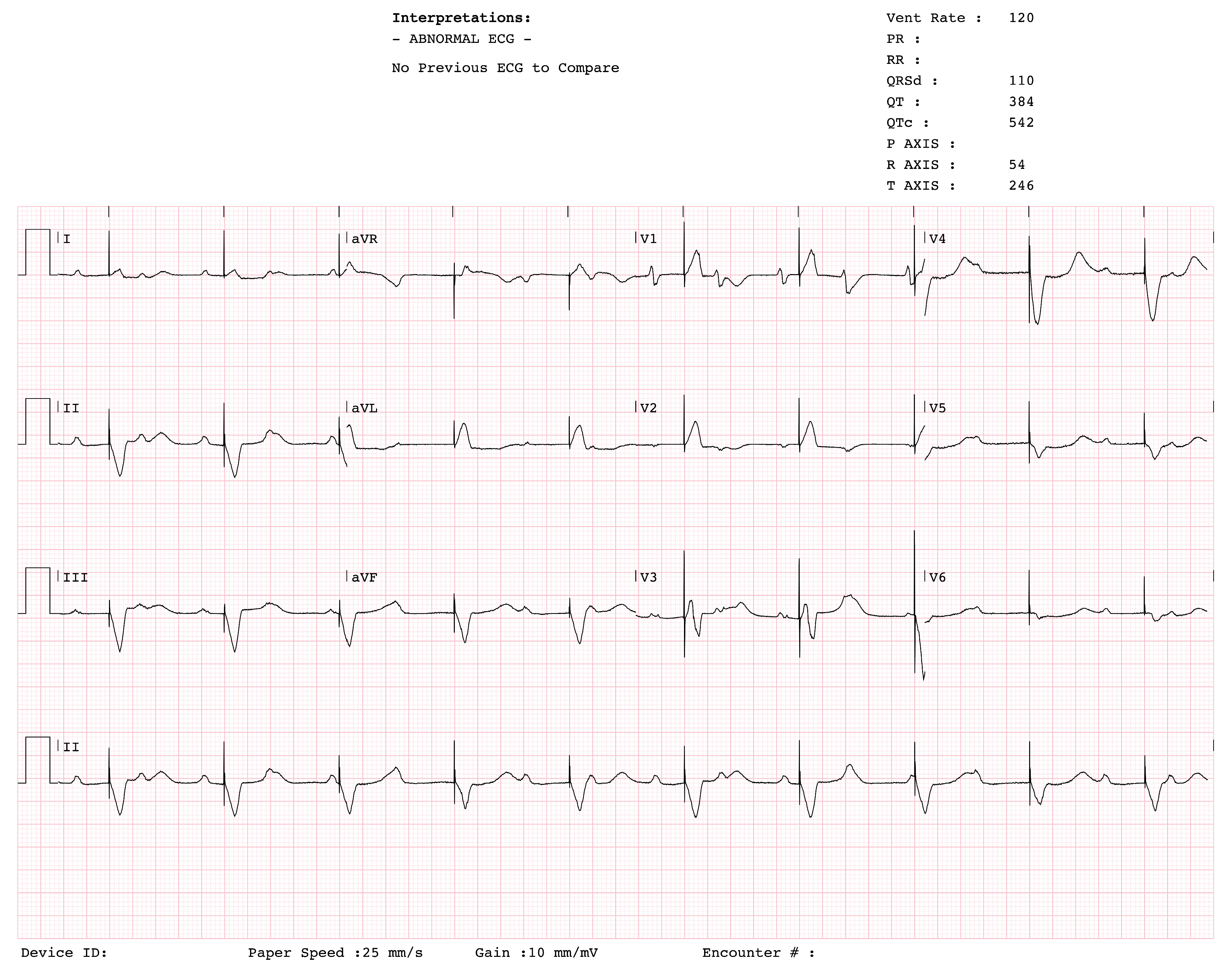

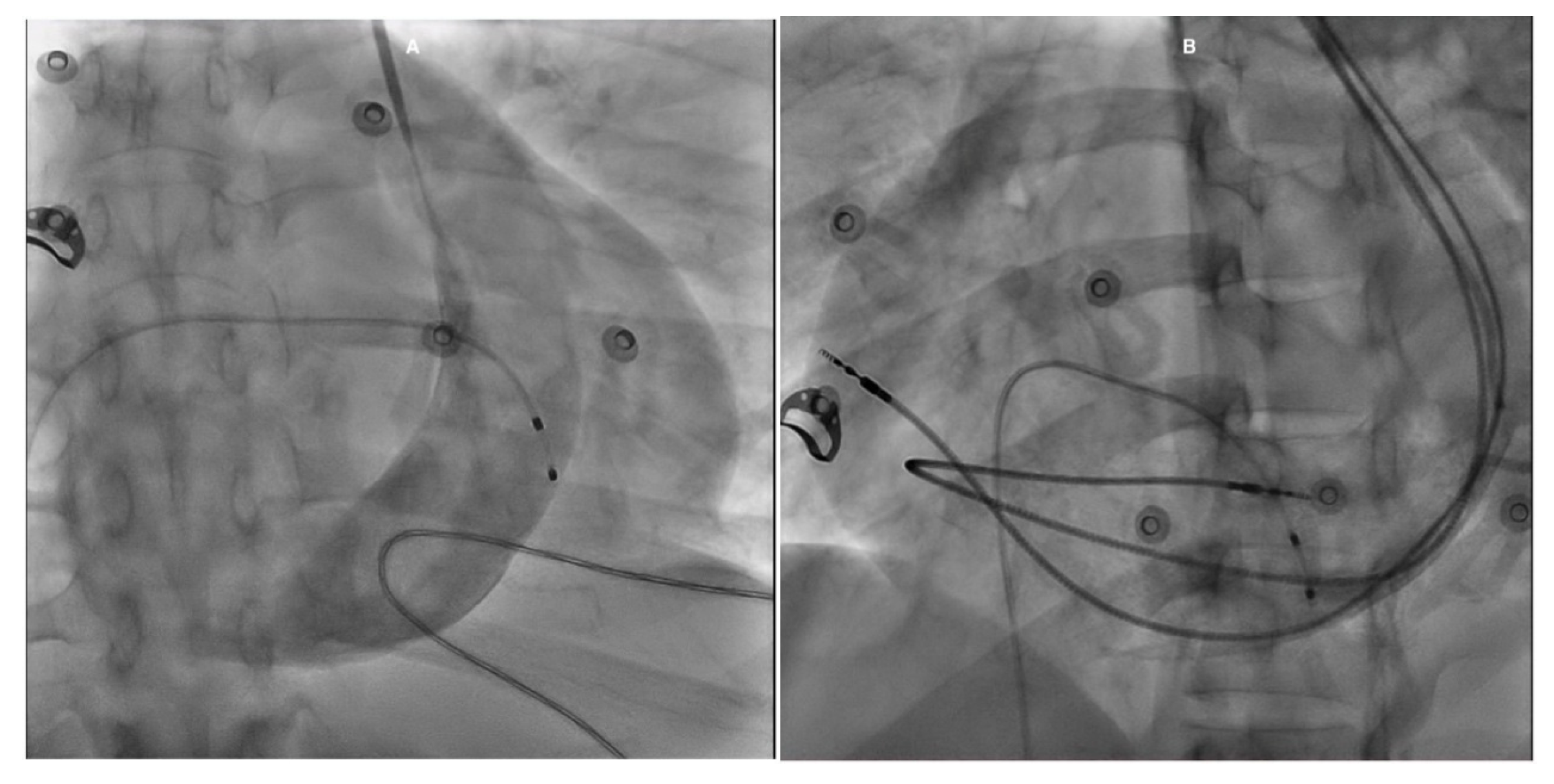

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for CHB and stabilized with a temporary pacemaker (PM). An ECG after temporary PM insertion showed ventricular pacing spikes (Fig. 2). Given the need for continuous stimulation and a mildly reduced LVEF, the patient was subsequently referred for cardiac resynchronization therapy with a pacemaker (CRT-P). In the catheterization laboratory, a left pectoral incision was made; however, the guide wire followed the trajectory of a PLSVC. Contrast injection to assess possible LV lead placement revealed only a single, very small branch of the CS, which was considered insufficient for lead insertion. As a result, the management plan was revised, and CRT-P was deemed unfeasible. Instead, a dual-chamber PM was implanted (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Twelve-lead ECG obtained immediately after temporary pacemaker insertion, showing ventricular pacing spikes preceding QRS complexes.

Figure 3: Fluoroscopy images in the RAO view with contrast show a large CS associated with a PLSVC (A). In the LAO view, the RA lead is positioned in the lateral wall, while the RV lead follows a large curvature due to its course through the RA before turning into the RV (B). RAO: Right anterior oblique; CS: Coronary sinus; PLSVC: Persistent left superior vena cava; LAO: Left anterior oblique; RA: Right atrium; RV: Right ventricle.

The implantation posed multiple challenges due to the altered venous anatomy. The right atrial (RA) lead placement was challenging; initial attempts to secure the lead in the RA appendage were unsuccessful due to repeated dislodgements. The lead was ultimately fixed in the RA lateral wall where trabeculations provided durable stability. Right ventricular (RV) lead placement was also challenging due to repeated dislodgements. The initially used 52 cm lead was too short to accommodate the extended venous course, and its septal positioning made fixation difficult. Replacing it with a longer 60 cm lead resulted in improved stability.

The patient’s thin body habitus increased the risk of pneumothorax, but at our institution, routine pre-procedural venography is not standard practice during device implantation. Accordingly, venography was not performed before pocket incision in this patient, and the PLSVC was only recognized intra-procedurally when the guidewire followed an unexpected course.

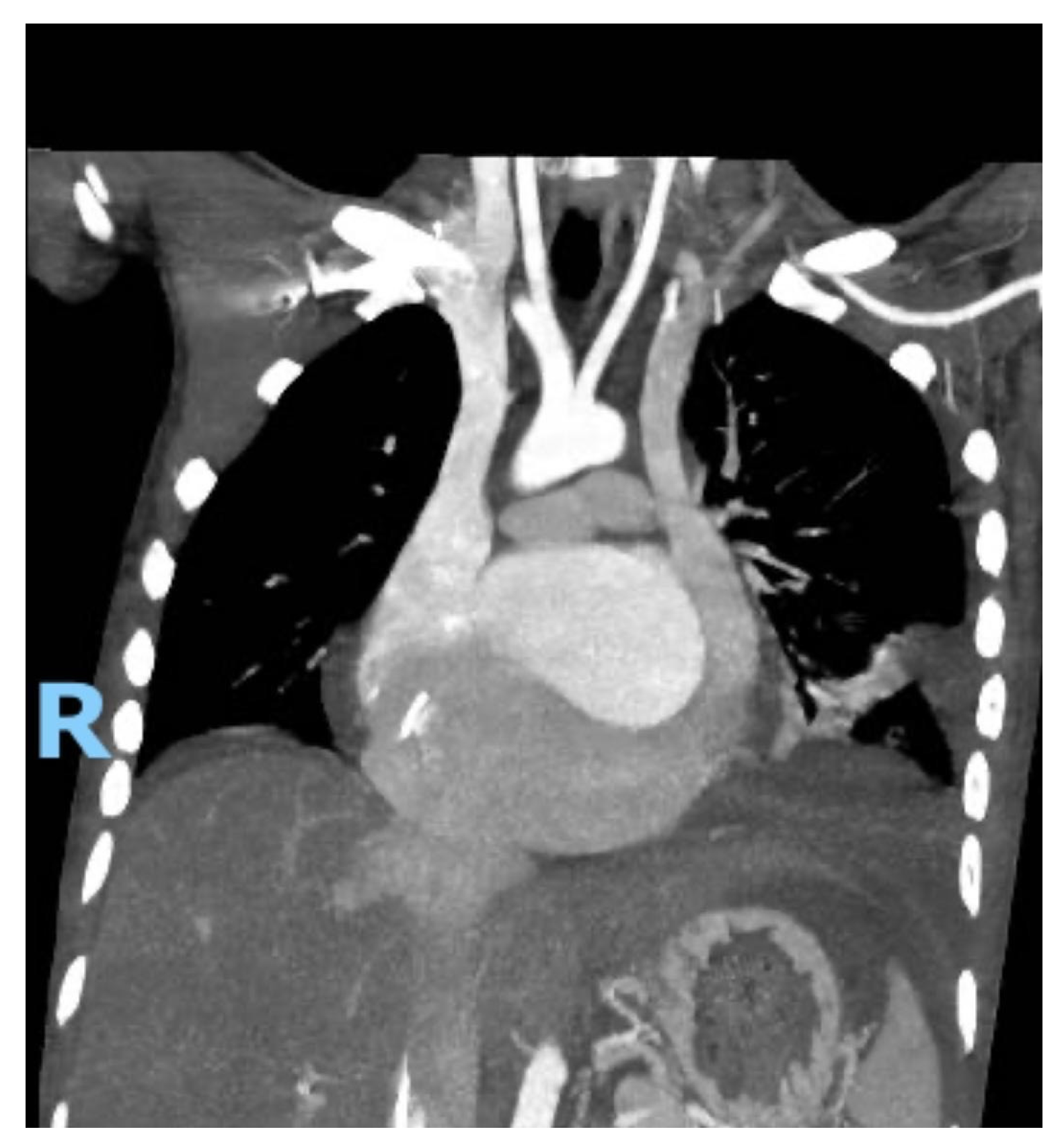

Subsequently, the patient developed oxygen desaturation, prompting a contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) scan. The scan revealed bilateral pleural effusions, significant CS dilation associated with a PLSVC, cardiomegaly, and biatrial enlargement (Fig. 4). The pleural effusion was successfully drained using a pigtail catheter.

Figure 4: Coronal contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography showing severe dilation of the coronary sinus secondary to persistent left superior vena cava, with marked biatrial enlargement, cardiomegaly, and bilateral pleural effusions.

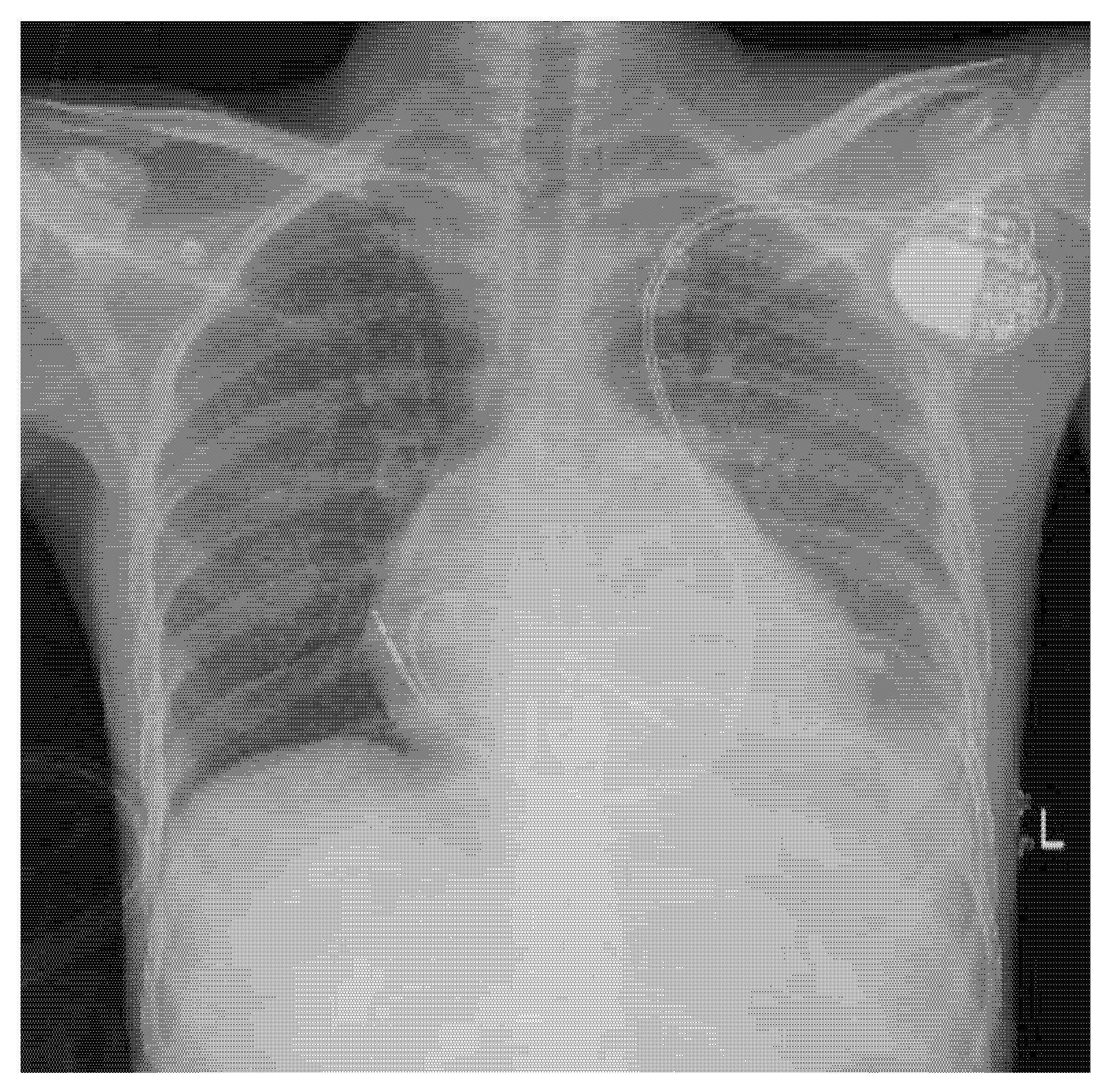

Further work-up was conducted to investigate the cause of CHB at a young age. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) revealed epicardial enhancement affecting the basal and mid-anterior and anterolateral walls, with no late gadolinium enhancement and no regions of dyskinesia. Post-procedural chest X-ray confirmed stable and well-positioned dual-chamber PM leads with no immediate complications (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Chest X-ray (anteroposterior view) depicting a dual-chamber pacemaker positioned in the upper left chest. The right atrial and right ventricular leads follow the trajectory of persistent left superior vena cava.

After a 6-month follow-up visit, the patient was doing well; his initial symptoms had vastly improved. PM interrogation showed good device functioning, with a high ventricular pacing burden (>98%). The patient was managed with bisoprolol, enalapril, and spironolactone, with titration based on tolerance and blood pressure, improving his LVEF to 55%.

The embryological origin of PLSVC can be traced to the primitive venous system, which comprises three paired veins: the vitelline veins, umbilical veins, and cardinal veins. The superior and inferior cardinal veins play a crucial role in returning blood from the cranial and caudal regions of the embryo to the primitive heart. PLSVC arises due to the failure of regression of the left common cardinal vein and the caudal part of the left superior cardinal vein [6].

In addition to its complex embryological anatomy, PLSVC is classified into two primary types based on its drainage pattern. The majority of cases (92%) drain into the right atrium via a dilated CS, which generally has no significant hemodynamic consequences. However, in 8% of cases, PLSVC drains directly or indirectly into the left atrium, leading to a right-to-left shunt and potential cyanosis or paradoxical embolism. Our patient showed significant CS dilation, consistent with an RA drainage pattern [7].

The diagnosis of PLSVC is often incidental and typically discovered during cardiovascular procedures. In our case, it was identified during CRT-P evaluation [8]. CRT-P was initially planned due to anticipated high-pacing dependency, mildly reduced LVEF, and symptomatic presentation which correlates with the 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS updated guidelines [9]. The risks of increased hardware burden in a young patient, including infection, must be weighed against potential benefits. Conduction system pacing, although technically demanding via a PLSVC route, should also be considered as a potential alternative strategy in such anatomies.

Although pre-procedural contrast venography is not routinely performed at our hospital, the difficulties encountered in this case highlight its potential value in patients with suspected venous anomalies. Based on this experience, our team is now considering adopting venography as a standard step prior to device implantation whenever feasible and not contraindicated, such as in patients with advanced renal dysfunction.

Previous reports emphasize that many SVC variants are clinically “silent” until an intervention is attempted and that a dilated CS should prompt evaluation for PLSVC prior to device procedures. Nurgül et al. [10] described incidentally detected “silent” SVC anomalies and highlighted the procedural risk when these variants are not recognized pre-procedurally. Several case series and reports have documented that PLSVC may complicate CRT-P or LV lead placement sometimes making conventional CRT-P implantation technically infeasible and that strategies such as using active-fixation leads, alternative venous routes, or right-sided implantation may be necessary [11,12,13]. Our case differs from previously published PLSVC device reports because it combines a young patient with Wilson’s disease and CHB in the background of a markedly dilated CS, raising the possibility that systemic copper deposition previously linked with conduction disturbances [14,15,16] may have contributed to the conduction disease in this anatomic setting.

Although a patent right SVC was present, a left-sided approach was continued due to intra-procedural identification of PLSVC after incision, with successful lead placement achieved via meticulous manipulation. A right-sided approach may be preferable in PLSVC cases when identified pre-procedurally, as it avoids the complex venous course.

After all the challenges, a dual-chamber PM was placed to restore normal cardiac pacing. However, due to the anatomic variations, multiple challenges were encountered prior to placement; one of the primary challenges was the short length of the original 52 cm RV lead, which led to recurrent micro-dislodgements. In line with recent recommendations [17], a longer 60 cm RV lead was used, and it remained securely positioned in the RV target area. For the atrial lead and despite initial stability in the RA appendage, the lead eventually required repositioning and was successfully secured and stabilized in the RA wall.

Wilson’s disease can affect the heart through myocardial copper accumulation, oxidative injury, fibrosis and conduction system involvement. A recent CMR study documented abnormal tissue characterization (including T1 elevation and extracellular volume [ECV] changes) in some series of Wilson’s disease patients [18]. Advanced CMR techniques (native T1/T2 mapping and ECV) may reveal diffuse myocardial involvement not seen with routine late gadolinium enhancement and might support a systemic mechanism for conduction disease in selected patients. If significant diffuse fibrosis or abnormal mapping had been present, this would have implications for monitoring and possibly device strategy but were not available at our facility. Although Wilson’s disease may contribute to conduction abnormalities, genetic testing for inherited conduction system disease should also be considered in such young patients without structural heart disease. Genetic testing for inherited conduction disease was considered; however, it was not performed during the index admission, and the patient was referred for outpatient genetic counseling and testing.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previously reported cases describing the coexistence of PLSVC, Wilson’s disease, CHB, and a dilated CS. The presence of CHB in a young patient with Wilson’s disease raises intriguing questions about potential mechanisms linking metabolic disorders to conduction system abnormalities. Wilson’s disease is known to cause myocardial fibrosis, arrhythmias, and conduction disturbances, which may have contributed to the patient’s presentation.

This case highlights the importance of pre-procedural imaging to identify venous anomalies such as PLSVC and prevent implantation failure. It also underscores the need for individualized pacing strategies in anatomically complex patients. The coexistence of Wilson’s disease and early heart block further reminds clinicians to consider systemic disorders as potential contributors to conduction disease.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Khaled Elenizi, Abdullah Sharaf Aldeen, Nagy Fagir, Hussien Hado and Mubarak Aldossari identified the worthy of the case and drafted the manuscript. Khaled Elenizi and Abdullah Sharaf Aldeen participated in collecting the patient information and followed-up work. Khaled Elenizi, Abdullah Sharaf Aldeen and Nasser Alotaibi were the major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: The Ethics Committee of King Saud Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, reviewed this case report and confirmed that formal approval was not required as it describes a single anonymized patient (proof of exemption available upon request). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for publication of clinical details and images was obtained from the patient.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/chd.2025.071226/s1.

Abbreviations

| Anteroposterior | |

| Complete heart block | |

| Cardiac magnetic resonance | |

| Coronary sinus | |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy with pacemaker | |

| Computed tomography | |

| Electrocardiogram | |

| Extracellular volume | |

| Left anterior oblique | |

| Left ventricular | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | |

| Persistent left superior vena cava | |

| Pacemaker | |

| Right atrial | |

| Right anterior oblique | |

| Right ventricular | |

| Superior vena cava | |

| Transthoracic echocardiography |

References

1. Gustapane S , Leombroni M , Khalil A , Giacci F , Marrone L , Bascietto F , et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of persistent left superior vena cava on prenatal ultrasound: associated anomalies, diagnostic accuracy and postnatal outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 48( 6): 701– 8. doi:10.1002/uog.15914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Irwin RB , Greaves M , Schmitt M . Left superior vena cava: revisited. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imag. 2012; 13( 4): 284– 91. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jes017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sirajuddin A , Chen MY , White CS , Arai AE . Coronary venous anatomy and anomalies. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020; 14( 1): 80– 6. doi:10.1016/j.jcct.2019.08.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cardi T , Ohana M , Marzak H , Jesel L . An unusual case of dilated coronary sinus: case report and clinical implications. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2021; 5( 10): 1– 5. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytab388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Horvath SA , Suraci N , D’Mello J , Santana O . Persistent left superior vena cava identified by transesophageal echocardiography. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2019; 20( 2): 99– 100. doi:10.31083/j.rcm.2019.02.510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Azizova A , Onder O , Arslan S , Ardali S , Hazirolan T . Persistent left superior vena cava: clinical importance and differential diagnoses. Insights Imaging. 2020; 11( 1): 110. doi:10.1186/s13244-020-00906-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kurtoglu E , Cakin O , Akcay S , Akturk E , Korkmaz H . Persistent left superior vena cava draining into the coronary sinus: a case report. Cardiol Res. 2011; 2( 5): 249– 52. doi:10.4021/cr85w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li T , Xu Q , Liao HT , Asvestas D , Letsas KP , Li Y . Transvenous dual-chamber pacemaker implantation in patients with persistent left superior vena cava. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019; 19( 1): 100. doi:10.1186/s12872-019-1082-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tracy CM , Epstein AE , Darbar D , DiMarco JP , Dunbar SB , Estes NAM , et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update of the 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities. Circulation. 2012; 126( 14): 1784– 800. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182618569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Nurgül K , Serkan D , Zafer I , Mehmet U , Mert İlker H , Ahmet Lütfullah O . Incidentally detected “silent” vena cava superior anomalies. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2021; 37( 3): 309– 11. doi:10.6515/ACS.202105_37(3).20190527A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Akdis D , Vogler J , Sieren MM , Molitor N , Sasse T , Phan HL , et al. Challenges and pitfalls during CRT implantation in patients with persistent left superior vena cava. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2024; 67( 7): 1505– 16. doi:10.1007/s10840-024-01761-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Seow SC , Agbayani MF , Lim TW , Kojodjojo P . Left ventricular pacing in persistent left superior vena cava: a case series and potential application. Europace. 2013; 15( 6): 845– 8. doi:10.1093/europace/eus417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Abdalwahid KF , Chu GS , Nicolson WB . A case report: upgrade to cardiac resynchronization therapy with a blocked persistent left-sided superior vena cava. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2020; 4( 2): 1– 5. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chevalier K , Benyounes N , Obadia MA , Van Der Vynckt C , Morvan E , Tibi T , et al. Cardiac involvement in Wilson disease: review of the literature and description of three cases of sudden death. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021; 44( 5): 1099– 112. doi:10.1002/jimd.12418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bajaj BK , Wadhwa A , Singh R , Gupta S . Cardiac arrhythmia in Wilson’s disease: an oversighted and overlooked entity!. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016; 7( 4): 587– 9. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.186982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Buksińska-Lisik M , Litwin T , Pasierski T , Członkowska A . Cardiac assessment in Wilson’s disease patients based on electrocardiography and echocardiography examination. Arch Med Sci. 2019; 15( 4): 857– 64. doi:10.5114/aoms.2017.69728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Afzal M , Nadkarni A , Bhuta S , Chaugle S , Gul E , Abdelbaki S , et al. Approaches for successful implantation of cardiac implantable devices in patients with persistent left superior vena cava. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2023; 14( 4): 5403– 9. doi:10.19102/icrm.2023.14043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Salatzki J , Mohr I , Heins J , Cerci MH , Ochs A , Paul O , et al. The impact of Wilson disease on myocardial tissue and function: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2021; 23( 1): 84. doi:10.1186/s12968-021-00760-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools