Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Design and Develop Function for Research Based Application of Intelligent Internet-of-Vehicles Model Based on Fog Computing

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Altinbaş University, Istanbul, 34000, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Abduladheem Fadhil Khudhur. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Communication and Networking Technologies for Internet of Things and Internet of Vehicles)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 3805-3824. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.056941

Received 03 August 2024; Accepted 08 October 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

The fast growth in Internet-of-Vehicles (IoV) applications is rendering energy efficiency management of vehicular networks a highly important challenge. Most of the existing models are failing to handle the demand for energy conservation in large-scale heterogeneous environments. Based on Large Energy-Aware Fog (LEAF) computing, this paper proposes a new model to overcome energy-inefficient vehicular networks by simulating large-scale network scenarios. The main inspiration for this work is the ever-growing demand for energy efficiency in IoV-most particularly with the volume of generated data and connected devices. The proposed LEAF model enables researchers to perform simulations of thousands of streaming applications over distributed and heterogeneous infrastructures. Among the possible reasons is that it provides a realistic simulation environment in which compute nodes can dynamically join and leave, while different kinds of networking protocols-wired and wireless-can also be employed. The novelty of this work is threefold: for the first time, the LEAF model integrates online decision-making algorithms for energy-aware task placement and routing strategies that leverage power usage traces with efficiency optimization in mind. Unlike existing fog computing simulators, data flows and power consumption are modeled as parameterizable mathematical equations in LEAF to ensure scalability and ease of analysis across a wide range of devices and applications. The results of evaluation show that LEAF can cover up to 98.75% of the distance, with devices ranging between 1 and 1000, showing significant energy-saving potential through A wide-area network (WAN) usage reduction. These findings indicate great promise for fog computing in the future-in particular, models like LEAF for planning energy-efficient IoV infrastructures.Keywords

Fog computing has become evident that the performance per watt drops dramatically when the target is under low load for vehicular networks. This inefficiency is a huge problem: idle servers can require up to 60% of their peak power draw as mentioned in [1], on average, cloud data centers are only utilized at 20% to 30% of their full capacity. Energy-proportional data centers and networks are popular because they can operate efficiently in underutilized situations. In practice, there are various open technical challenges in reducing the static energy consumption of hardware as mentioned in [2]. While Central Processing Units (CPUs) became more and more energy-proportional over the years thanks to energy-saving mechanisms like dynamic voltage and frequency scaling (DVFS), other components like memory, network, and networks are traditionally energy disproportional for vehicular networks as mentioned in [3]. Static energy consumption of resources like network adapters or routers can make up to more than 90% of their maximum energy consumption as mentioned in [4]. Nevertheless, due to many technological advances over the last decade, modern hyperscale data centers can operate in extremely energy efficient manners for vehicular networks as mentioned in [5]. This means a huge potential for energy savings lies in the reduction of static energy consumption. Less attention has been devoted to the question of what extent fog computing may affect the overall power usage of network infrastructure. On the one hand, it has been shown that fog computing can highly reduce network traffic due to its geo-proximity to data producers, which, as a consequence, also lowers the network’s power usage. Furthermore, Nano data centers usually require less cooling than bigger data centers as mentioned in [6]. On the other hand, hyperscale data centers are highly optimized for energy-efficiency and power proportionality, and some recent studies suggest that their overall consumption may be significantly lower than previously assumed for vehicular networks as mentioned in [7]. Large-scale deployments of distributed fog infrastructure will inevitably impose additional power requirements and it is questionable whether a performance per watt comparable to that of centralized data centers can be achieved. Since large-scale, real-life deployments of fog computing infrastructure are still to come, research on new communication protocols and scheduling algorithms is mostly limited to theoretical models and emulation tools. Over the last four years, numerous emulators, simulators, and analytical models for vehicular networks as mentioned in [8] have been proposed. Since version 2.0, fog computing features an energy model proposed by [9] that allows modeling the power usage of CPUs. Apart from being relatively simplistic, its main limitation is that it cannot be used in conjunction with the vehicular networks model. The fog computing extension addresses this by introducing energy-aware network components that even allow modeling the energy consumed by VM (Virtual Machine) migrations. However, it introduces a lot of conceptual and computational complexity, is coupled towards modeling inter-data center traffic, and does not support different link types like wireless connections. Because of that, this energy model is not appropriate for modeling energy consumption in fog computing environments. Recently, IoV has also become a hot topic with the increasing number of connected vehicles. In general, how to handle the increasing demand for computing resources and power efficiency are considered the most important factors. IoV networks contain millions of interacted devices that produce, process, and disseminate data at real-time speed. Large-scale networks are prone to many problems, and their huge power consumption and performance optimization will be a great challenge. Furthermore, traditional cloud-based solutions will fall short in addressing latency-sensitive and energy-intensive IoV demands; this compels the need to investigate other approaches, such as fog computing.

It further elaborates that with the scaling of computing on the need for efficiency, together with the unique demands imposed by IoV networks, this research is warranted. This is because the still-increasing size and complexity of vehicular networks continuously dramatize cloud computing deficiencies related to latency and energy efficiency. Fog computing might be one of the possible avenues; however, existing simulators and frameworks do not consider large-scale scenario simulations or have their focus on energy consumption at a fine-grained level. The big challenge is to design a fog computing model that can support large-scale vehicular networks with energy-aware mechanisms for task placement and routing strategy optimizations. Besides this, it should consider the dynamic scenario of devices joining and leaving the network, a common reality for vehicle mobility. Basically, addressing these challenges provides a clear insight into IoV research and future infrastructure planning.

Existing simulators cannot sufficiently model energy consumption of fog computing environments in large-scale experiments. There is a need for a simulator that allows identifying the causes of power usage and enables research on energy-efficient architectures and algorithms to fully exploit the fog’s potential for conserving energy. Even with research into fog and cloud computing, the gap still remains in managing large-scale dynamic vehicular networks with considerations for energy conservation. No existing model and simulator are capable of real-time simulation of large-scale IoV environments where frequent joinings and leavings occur, nor do they optimize energy consumption across heterogeneous infrastructures. Conclusively, this leads to increased energy consumption by Wide-Area Networks (WANs) in such systems; thus, current solutions are not adequate for any sustainable future deployment. In this respect, there is a pressing need for a scalable and energy-aware fog computing model that could address these deficiencies while maintaining the high performance demanded by IoV applications. Derived from these use cases and considering the numerous challenges in modeling fog computing environments, the following requirements are placed on the proposed model:

(1) Internet-of-Vehicles Based Realistic Fog Computing Environment: The model enables the simulation of distributed, heterogeneous, and resource-constrained fog computing environments, where compute nodes are linked with different types of network connections. The model ensures location-awareness of nodes, for example, to calculate close by mobile access points. Nodes can be mobile; namely, their location can change according to predetermined or randomized patterns, and they can join or leave the topology at any time. The model enables the simulation of different streaming applications, from linear data pipelines to applications with complex topologies, including a multitude of data sources, processing steps, and data sinks.

(2) Internet-of-Vehicles Based Holistic Energy Consumption Model: The model is able to assess the power usage of all data centers, edge devices, and network links in the fog computing environment at any point in time during the simulation. Hence, it allows for the creation of detailed power usage profiles for individual parts of the infrastructure. Additionally, the model makes the energy consumption of infrastructure traceable to the responsible applications to let researchers identify inefficiencies and opportunities to improve in the network’s architecture.

(3) Internet-of-Vehicles Based Energy-Aware Online Decision Making: The model enables simulated schedulers, resource management algorithms, or routing policies to assess the power usage of individual compute nodes, network links, and applications during the run time of the simulation and, hence, allows for energy-aware decisions. This enables research on algorithms such as energy-efficient task placement strategies or routing policies. Furthermore, the model enables said algorithms to dynamically apply energy-saving mechanisms such as powering off idle fog nodes.

(4) Fog Computing Performance and Scalability: The model allows the simulation of complex scenarios with hundreds of parallel existing devices that execute thousands of tasks. The runtime of simulations of such scale is at least two orders of magnitude faster than real-time.

The contribution to be made by this research work is called the LEAF computing model, a new framework developed for the simulation of a large-scale vehicular network with prime consideration of energy efficiency. The main contribution of this paper focuses on the following principal aspects:

• Development of the LEAF Model: A scalable and energy-aware fog computing model that will be able to support thousands of streaming applications and dynamically changing vehicular networks.

• Energy-Aware Algorithms: The energy-aware task placement and routing algorithms will be integrated together using real-time power usage data for performance optimization.

• Hybrid Empirical Results: Model the data flows and power consumptions with a hybrid approach by combining analytical and numerical methods, hence enabling scalability while reducing computational overhead.

• Evaluation and Results: Extensive simulations show that LEAF can save up to 98.75% of the distance for devices between 1 and 1000, reducing WAN usage significantly and allowing promising energy savings.

As more and more devices become connected to the internet, the amount of produced data is soon expected to overwhelm today’s network and compute infrastructure in terms of capacity as mentioned in [10]. In their latest annual internet report, Cisco states that there are already 8.9 billion machine-to-machine connections in 2025, and they expect this number to grow to 14.7 billion by 2023 as mentioned in [11]. Furthermore, there are serious privacy and security concerns associated with overcentralizing the processing and storage of IoT (Internet of Things) data as mentioned in [12]. Energy management in vehicular networks has been studied in several works. The author in [13] proposed a cloud-based energy-efficient framework for IoT (Internet of Things), with one of the key concepts being the offloading of tasks from end devices to cloud servers. Along this line, Reference [14] proposed a hybrid cloud-fog architecture aiming to minimize latency in IoT environments. However, all these solutions rely on WANs, whose inefficiencies can arise in the form of higher energy consumption and slower response times when the number of deployments increases.

Recent advances in fog computing, extending cloud computing capabilities to the edge of the network, provide a promising alternative. Due to the proximity to the end devices in IoV networks, fog computing can typically attain lower latency and power consumption. However, none of the existing fog-based models is sufficiently capable of simulating the dynamic, large-scale, and heterogeneous nature of vehicular networks. Various limitations must be overcome by developing innovative solutions that include energy-aware algorithms and scalability for thousands of devices.

Fog and edge computing describe computing paradigms targeted at solving the problems posed by the rise of IoT. A distributed layer of smaller data centers, termed Nano data centers, cloudlets, or fog nodes, is supposed to process data close to its producers-the so-called edge of the network as mentioned in [11]. Edge devices can be anything from mobile phones or air quality sensors to connected cars and traffic lights. The geo-proximity to end-users can lead to highly reduced latencies for real-time applications, as well as less overall network traffic. Fog nodes can either directly respond to actuators or at least preprocess, filter, and aggregate data to reduce the volume sent over the WAN as mentioned in [15]. Moreover, many applications do not require centralized control and could instead operate-and therefore, scale in a fully distributed manner. An example is smart traffic management, where connected cars and traffic lights can act by communicating purely among themselves as mentioned in [16]. Nevertheless, fog computing is mostly meant to complement cloud computing, not replace it.

From a privacy point of view, fog nodes can anonymize data before forwarding it to prevent misuse by the cloud provider or another third party. For example, more and more smart meters, namely electricity meters with internet access, are being deployed. They regularly report the current power consumption to network operators to enable more efficient control of the electricity network. However, the raw sensor data might contain confidential information, such as when users switch the television on or off. Fog nodes could, for instance, aggregate and anonymize the measured data from different households to ensure privacy as mentioned in [16].

Besides fog computing, there exist numerous related computing paradigms: Edge computing, mist computing, mobile cloud computing, and cloudlet computing, to name a few. Despite attempts to highlight differences in these approaches, like the proximity of computation to the edge of the network, or the adoption of pure peer-to-peer concepts, they mostly describe similar ideas. Further, the terminology is sometimes used inconsistently across research papers, which can be attributed to the fact that the research field is still very young as mentioned in [17]. In recent years, a consensus has emerged that edge computing refers to computing on-or extremely close to-the end devices, while the fog is located between edge and cloud. For the course of this thesis, fog computing refers to all fog and edge-related computing paradigms. LEAF is flexible enough to model all kinds of distributed topologies, including pure peer-to-peer architectures. Although fog computing is a rapidly growing field, as of today, there exist almost no commercial deployments on which researchers can conduct experiments. Moreover, setting up, managing, and maintaining a large number of heterogeneous devices incurs high operational costs. To facilitate research on fog computing, a variety of emulators and models have been presented in recent years. This section aims to provide some background on simulation and modeling as mentioned in [18].

Emulators enable the execution of real applications in virtual fog computing environments. By introducing latencies or failure rates among virtualized compute nodes, the emulator mimics specific characteristics of the fog environment during execution. This approach approximates reality closely and allows for empirical results but has one major drawback: The execution of applications in emulated environments is computationally even more expensive than running them natively as mentioned in [19]. This constraint can be mitigated up to a certain point by the scalability of cloud computing. Nevertheless, large-scale experiments with thousands of devices and applications soon become very costly.

A different approach towards research on fog computing environments is the development and usage of models. A model abstracts some of the fog environment’s underlying details and thus can make experiments more efficient, scalable, and most importantly-easier to analyze. Creating and applying models can result in a more comprehensive understanding of the problem space by identifying “driving” variables as mentioned in [20]. Yet, modeling is in-variably a trade-off between realism and simplicity, and what makes a good model always depends on the use case.

The execution of models is called simulation. A considerable advantage of simulation to other approaches is that its runtime is not necessarily bound to real-time. A sufficiently abstract simulation could, for instance, reproduce several hours of a fog computing environment’s behavior in a few minutes. However, modeling also has its pitfalls: Wrong or biased assumptions can lead to invalid simulation results. This is especially relevant in fog computing environments where almost no real-life deployments of infrastructure could be used for validation by comparison. Numerical network models are almost invariably so-called Discrete-Event Simulations (DES) in fact all simulators. A DES is constituted of a queue of events that each take place at a certain time. Events get processed in chronological order, and each processing step may result in new events that are placed in the queue as mentioned in [21]. It is assumed that the system state between consecutive events does not change; consequently, the simulator can jump directly from event to event. This allows simulations faster than in real-time. The simulation is over if there are no more events in the queue, or a predefined time limit has been reached. A DES scales roughly linearly with the number of events, but due to its sequential nature, it is particularly hard to parallelize as mentioned in [22]. A general measure for describing the energy effectiveness of hardware is performance per watt, namely the rate of computation that a piece of hardware can provide for every watt of consumed power. Depending on the field of application, the metric used to specify performance varies: Scientific computing and computer graphics require large amounts of floating-point calculations, which is why the performance of supercomputers and GPUs (Graphic Processing Unit) is described in FLOPS (Floating-Point Operations Per Second). The performance of non-scientific and general-purpose computing units is mostly expressed in MIPS (Millions of instructions per second) or other comparable benchmarks. As IoT applications are very diverse, in the following MIPS are used to determine a compute node’s performance as mentioned in [23]. When designing detailed models of computing infrastructure, it is possible to determine performance per watt metrics for additional components like memory, hard discs, mainboards, fans, or the power supply itself. Nevertheless, there is usually a clear correlation between MIPS and memory and storage access. Thus, in higher-level models, it is reasonable to describe a compute node’s performance per watt based only on its computational load.

In [24], it came up with a hybrid cloud-fog computing framework for IoV networks and presented a task offloading model to achieve optimality with minimum latency. Therefore, their model offers better response times compared to the cloud-only model. Although this approach resulted in significant reductions in the delays of executing the tasks, it did not concentrate on how energy consumption could be optimized-a major concern in large-scale IoV deployment where the number of devices is continuously increasing.

In [25], it proposed an architecture for vehicular networks based on edge computing. They underlined how there is a real need for the computation to be fully localized since complete reliance on cloud servers hosted at a centralized location can result in much overhead. Although their work demonstrated how edge computing can reduce latency, their focus remained on task offloading and did not adequately explore energy-saving mechanisms. This calls for more energy-aware solutions, especially when scaling up to thousands of devices.

In [26], it proposed an energy-aware fog computing model exclusively for IoT applications. Energy-efficient task scheduling and resource management algorithms were introduced in their model that reduced the overall power consumption by 15%; however, their system was limited to small and medium-sized IoT deployment and hence could not be extended to large-scale scenarios characterizing IoV environments.

In [27], it presented a novel fog computing architecture for VANET (Vehicular ad-hoc network). In this architecture, the hierarchical structure was utilized by the authors to handle the fog nodes over a wide area and investigate the potential for latency reduction with a great magnitude. However, improving the efficiency in communication was the focus of that work, and energy-aware mechanisms were not considered. This scalable framework, while addressing one major issue, left the energy optimization problem nearly unaddressed.

In [28], it proposed an efficient fog computing model in large-scale IoV networks. In the year 2024, energy efficiency was attained through the implementation of optimized scheduling of tasks. Energy consumption was predicted by machine learning algorithms and allocated resources dynamically to those fog nodes which consumed the least power. Though this method showed a reduction of energy consumption by about 20%, this system relied on WAN connections. Besides, this is less energy-efficient when the usage rate of WAN is high as shown in Table 1.

In [29], it presented an energy-efficient fog computing model for vehicular networks. The proposed model was based on the fact that a proper power usage analysis was considered in detail. It permitted dynamic vehicular mobility, emulating practical conditions in which the join and leave of vehicles within a network happened quite frequently. The derived solution was computationally expensive and thus not scalable for bigger networks. This deploys the challenge of scalability, energy efficiency, and real-time performance, which is still key in IoV systems.

This research introduces the Large Energy-Aware Fog (LEAF), a simulator that aims to eliminate the short-comings of existing models, thus enabling comprehensive modeling of Large Energy-Aware Fog computing environments. The most evident deficiency of existing fog computing simulators is that, if at all, only the energy consumption of data centers and end devices is simulated. However, for obtaining a holistic energy consumption model, the network must be considered too. The simulators presented feature network modeling, and did this very thoroughly. They model every single network package individually, sometimes even implementing entire communication protocols like TCP (Transmission Control Protocol). The Vehicular OBU Capability (VOCC) dataset was used in this research using the LEAF technique for evaluation. This degree of detail negatively impacts performance. Demands scalability, LEAF takes a different approach: Network links are considered resources, similar to compute nodes, that have certain properties and constraints and a particular performance per watt. Data flows between tasks and allocates bandwidth on these links. The dataset was acquired from KAGGLE which is https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/haris584/vehicular-obu-capability-dataset, accessed on 20 January 2023. Modeling networks in this more abstract fashion is inspired by analytical approaches. It enhances the performance of the DES because fewer events are created. Furthermore, the analysis of a model’s state at a particular time step becomes very easy: The user can comprehend the current network topology, all data flows, and allocated resources of running applications solely by observing the simulation state at any point in time. A disadvantage of this kind of modeling is the higher level of abstraction, and therefore, possibly less accurate results.

Fig. 1 depicts an exemplary infrastructure graph with a multitude of different compute nodes and network links. In the bottom left, several sensors form a Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) mesh network, which connects to a fog computing layer. The fog nodes in this layer are interconnected via the passive optical network (PON) and can communicate with cloud nodes via WAN. The bottom right shows several smart meters that connect to public fog infrastructure via Ethernet. Furthermore, connected cars are linked to these fog nodes, as well as to each other for Vehicle-To-Vehicle (V2V) communication via Wi-Fi. The public fog nodes connect the cloud via WAN with a 4G LTE (Long term Evolution) access network as shown in Table 2.

Figure 1: Complex infrastructure graph and flows with various compute nodes and network links

In the proposed model, the simulation environment was configured in such a way that the realistic conditions of vehicular networks were replicated properly. The details of the simulation parameters that have been used to evaluate the LEAF model are furnished in Table 2. Here, the authors preferred to use the IEEE 802.11p MAC (Multiple Access Control) protocol since it has already become quite effective and reliable in many VANET communications where vehicles are moving at high speeds. The Two-Ray Ground model was selected to simulate the propagation of data, which gives a good model for signal transmission in open areas, a frequent case in vehicular environments.

This was simulated for 1000 s to give ample time to observe performance metrics under variable conditions. The vehicle density ranges from 50 to 200 vehicles per square kilometer, while the number of simulated vehicles is 500. The radio communication range was set to 300 m in order to ensure realistic communications between the vehicles. By leveraging the principles of fog computing, the performance analysis of energy consumption and efficiency of task placement has been carried out using a customized LEAF simulator. Meanwhile, the SUMO (Simulation of Urban Mobility) traffic simulator was integrated, enabling realistic vehicle movements and traffic conditions to be simulated-thus, providing a complete extensible evaluation framework for the proposed model.

Lastly, in the top right, two devices are directly connected to the cloud via WAN using a Wi-Fi and 5G access network. Note that the access network, for example, wireless routers or mobile base stations, is usually not explicitly modeled in LEAF. Instead, the user should determine the overall bandwidth and power usage of the entire WAN link. Two vehicles are on the map, connected to nearby traffic lights, and two traffic lights have fog nodes attached. Note that this is just an example; the number of vehicles and fog nodes varies in the experiments as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Map of the simulated city center with two vehicles and two fog nodes

Although some components of LEAF are based on analytical approaches, at its core it remains a numerical model to be exact a DES (Data Encryption Standard). The user can adjust the infrastructure’s topology, the placement of applications, and the parameterization of resources over time. This flexibility has two decisive advantages over purely analytical models: First of all, fog computing environments can be represented in a much more realistic way. LEAF allows for dynamically changing network topologies, mobility of end devices, and varying workloads. Secondly, LEAF enables online decision making during the simulation, enabling research on energy-aware task placement strategies, scheduling algorithms, or traffic routing policies.

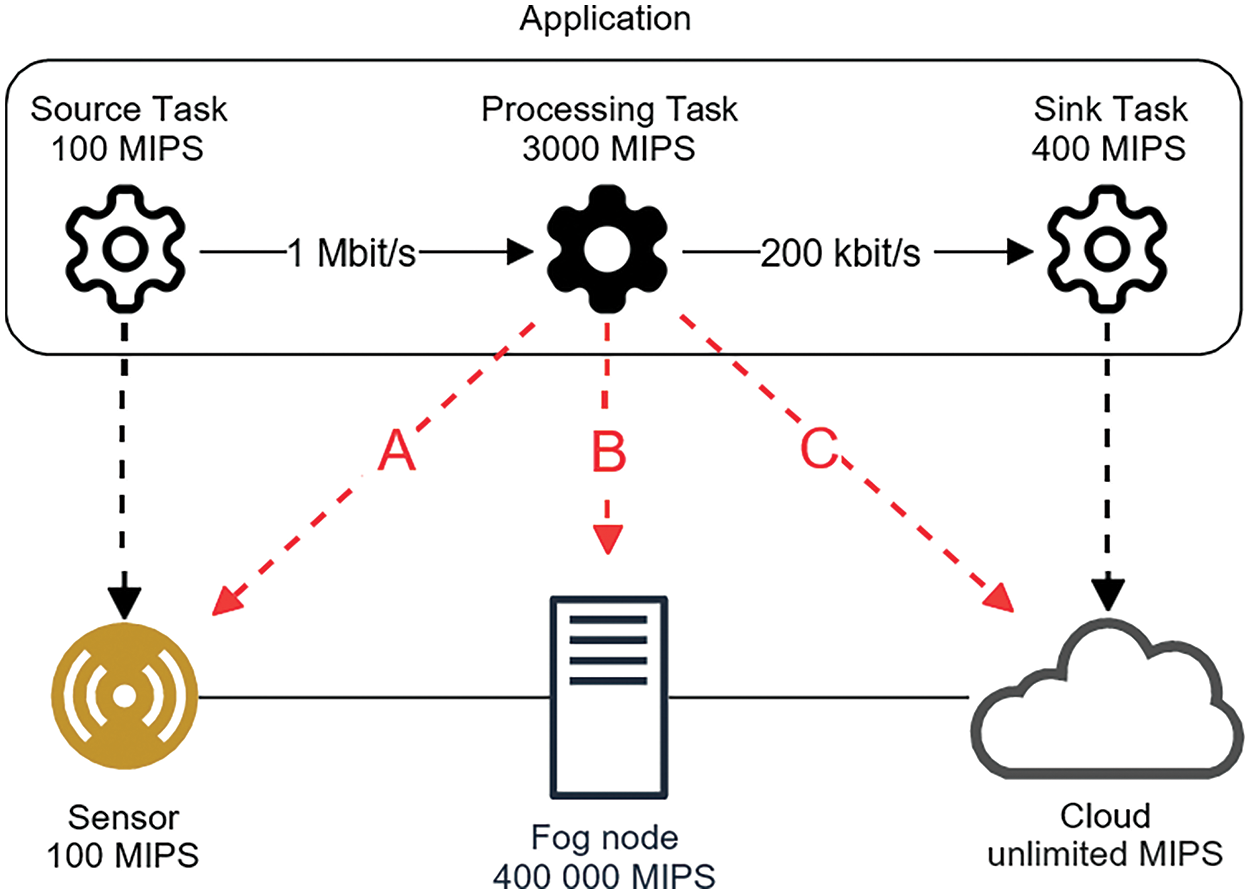

The source task is running on a sensor and sends 1 Mbit/s to the processing task. The processing task requires 3000 MIPS and emits 200 kbit/s to the sink task, which, for example, stores the results in cloud storage as given in Fig. 3. A task placement strategy can now decide on a placement of the processing task, having three options:

Figure 3: Different possibilities for placing a processing task

They are not only suitable for periodic measurements for subsequent analysis of power usage profiles, but can also be called at runtime by other simulated hardware or software components as shown in Fig. 4. Examples of such simulated entities are batteries that update their state of charge or energy-aware task placement strategies.

Figure 4: Complex application placement

• Placing the task on the sensor: Since the sensor does not have the computational capacities to host a task that requires 3000 MIPS, this placement is not possible.

• Placing the task on the fog node: If the fog node still has enough remaining capacity, it can host the task. This placement effectively reduces the amount of data sent via WAN.

• Placing the task in the cloud: The cloud has unlimited processing capabilities in this example. Consequently, a placement is always possible.

LEAF supports online decision making based on power usage and complies with requirements as shown in Fig. 5.

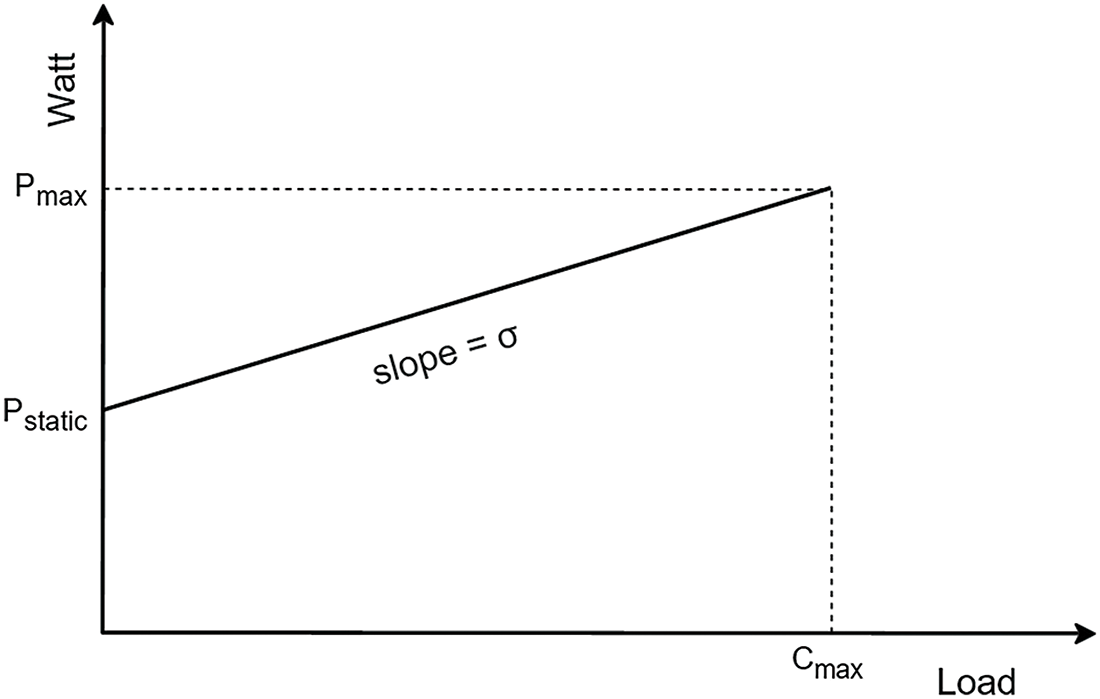

Figure 5: A linear power model is being followed in this research work

In theory, a power model can be any mathematical function and may depend on multiple input parameters besides the load. This linear power model can be defined as:

Evidently, this model improves the accuracy of the simulation. Nonetheless, when simulating hundreds or thousands of nodes, more complex power models come at a cost. Calculating the distance between that many interconnected devices at each time step of the simulation can become computationally expensive. If the performance gets affected too much, an alternative approach, in this case, could be to estimate an average distance and incorporate the energy dissipation directly into the slope σ of the linear model.

However, LEAF does currently not allow the modeling of asymmetrical bandwidth and power consumption characteristics. Since edges in the infrastructure graph are undirected, network connections are expected to provide the same bandwidth and consume the same power for uplink and downlink-although, in reality, this is rarely the case. To obtain valid results, the user must determine how the network is mostly used in the simulated scenario and choose an adequate parameter. For example, if the mobile base stations in a simulation solely upload data to the cloud, the user should pick a σ, which represents a realistic uplink consumption. A future version of LEAF can remedy this deficiency by not utilizing an undirected graph as the basis for the infrastructure model but a directed multigraph. This way, uplink and downlink can be modeled separately. Moreover, it would become possible to have multiple different connections between two compute nodes. This would additionally enable energy-aware routing algorithms that, for example, could decide whether it is better to send data via Wi-Fi or Bluetooth.

Furthermore, for precise results, one would not only need to model the transmit power of base stations but also how it degrades over the distance since mobile devices usually connect to the base station with the strongest signal as given in Fig. 6. To summarize, if no further information is available on the type and location of base stations or if different kinds of base stations are deployed, it is tough to provide reasonable estimates on their consumption.

Figure 6: Topology of WAN between mobile device and cloud data center

If possible, the parameterization should be based on measurement data collected in the real existing environment as given in Table 3. In fully conceived scenarios, the consumption of base stations remains a significant factor of uncertainty.

Incorporating these techniques into the fog environment simulation is of varying difficulty. Shutting down hosts within compute nodes can be modeled by tracking how long they are idle and marking them as powered-off after some time. For powered-off hosts, power models return P(t) = 0. It is significantly more complicated to switch off entire compute nodes or network links in the simulation because this changes the network’s topology. Since the proposed model is relatively abstract and does not model individual switches or routers, it is not suitable for modeling the dynamic shutdown of single network devices.

To evaluate LEAF and present its capabilities, different architectures, and task placement strategies were simulated in a smart city scenario. The results of these experiments are analyzed and discussed in this chapter. Note that, the evaluation is not based on real measurement data-the simulated scenarios are designed to be realistic but simple. Thus, the objective of this evaluation is not to provide exact results on how to design future fog environments. It rather aims to demonstrate how researchers can use LEAF to effectively analyze and improve the overall energy consumption of fog computing environments. Furthermore, it will be shown that the model fulfils the requirements. The prototypical implementation of LEAF is given in Fig. 7. The experimental setup of the evaluated scenarios explains, analyzes, and discusses the results of the conducted experiments.

Figure 7: Live visualization of the prototype: (a) A map of the city, (b) the number of vehicles on the map

Multiple modules were added or replaced in MATLAB (Matrix Laboratory). These changes are not directly related to simulating fog environments but are general improvements to the library. In particular, the MATLAB core implementation was improved in the following ways:

The existing network topology was highly coupled to BRITE topology files, and had an unintuitive interface and a worst-case complexity for finding shortest paths, implementing only the Floyd–Warshall algorithm. It was replaced with a more flexible interface which can be implemented by users using libraries such as graphs to make use of the many features and algorithms implemented in this library. The existing power models were only suitable for use with data center hosts. They were replaced with a general power model that can be used for hosts and network links but is entirely decoupled from their implementation.

The LEAF project itself depends on this patched MATLAB implementation core and contains two packages: First, the package contains the proposed infrastructure and application model as well as the related power models. The infrastructure and application graphs were implemented on top of the graph with percentage of the distance between 1 to 1000 covered up to 98.75% using the LEAF technique. Second, the package implements all functionality required in the evaluation. It contains the city scenario, mobility model, compute nodes, network link types, and applications. Additionally, a live visualization has been implemented with charts in order to provide insights into running experiments. The visualization updates itself according to a user-defined frequency and contains four charts. 1. A map of the city and the moving vehicles, 2. the number of vehicles that were present on the map at a given time, 3. the infrastructure power usage over time and 4. the application power usage over time. An example screenshot can be seen in the figure above. Each experiment run outputs two CSV (Comma Separated Values) files containing the measurements. The analysis of the results was performed in MATLAB.

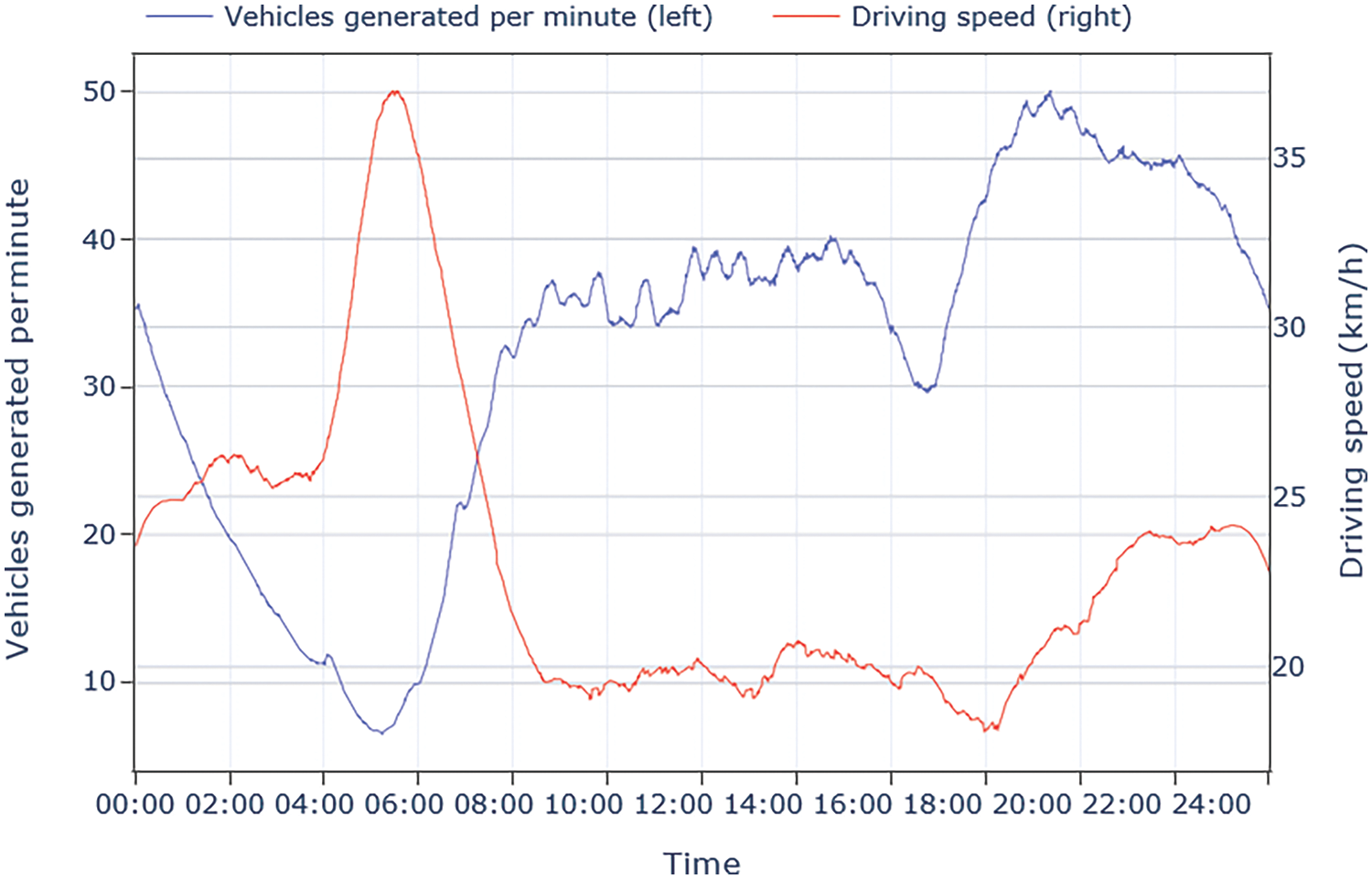

First, all samples were grouped, based on the time of the day the passengers were picked up. The time window is one minute; hence, there are 60.24 = 1440 groups. Based on the frequency distribution, the simulator generates new vehicles by periodically calculating the current probability of arriving cars following a Poisson distribution. Fig. 8 shows the average number of vehicles generated per minute.

Figure 8: Number of vehicles generated per minute vs. average driving speed

We can observe that during early morning hours, only around five vehicles enter the map every minute, while at the evening rush hour, it is up to 50. The vehicles arrive on one of the edges of the map and follow a random path to another edge where they leave. The speed of the vehicles is determined via the dataset. The median distance and duration of every group were used to calculate the average speed at a given daytime. At night, vehicles can drive at more than 30 km/h; during the daytime, they do not even reach 15 km/h.

A series of eight different experiments were conducted in the described smart city environment. Table 4 below and Fig. 9 provide an overview of the results. The following sections explain all experiments and analyze and discuss their outcome in detail.

Figure 9: The above table is visualized as a stacked bar plot

To understand and improve on these results, we take a look at the causes of power usage. As depicted in Fig. 10, all vehicular based applications together require a constant 1416.2 W of power, totaling 56.5% of the overall energy consumption. Since LEAF uses an analytical approach for modeling, it is straightforward to calculate where this power usage originates from 16 traffic light systems constantly streaming 10 Mbit/s to the cloud over WAN, resulting in power usage of

Figure 10: (a) Power usage of infrastructure in experiment Cloud, WAN and Wi-Fi, (b) Power usage of applications in experiment Fog and Wi-Fi

Additionally, the processing tasks of these applications consume

The analysis of infrastructure and application power usage in experiment yielded that the many deployed fog nodes impose a high static power usage on the system. Moreover, the fact that these fog nodes are not always fully utilized is an evident inefficiency as given in Fig. 11. This inevitably raises the question if fewer fog nodes that offload tasks to the cloud at peak times could lower overall energy consumption. Further experiments were therefore conducted to demonstrate how LEAF can help to plan more energy-efficient infrastructures.

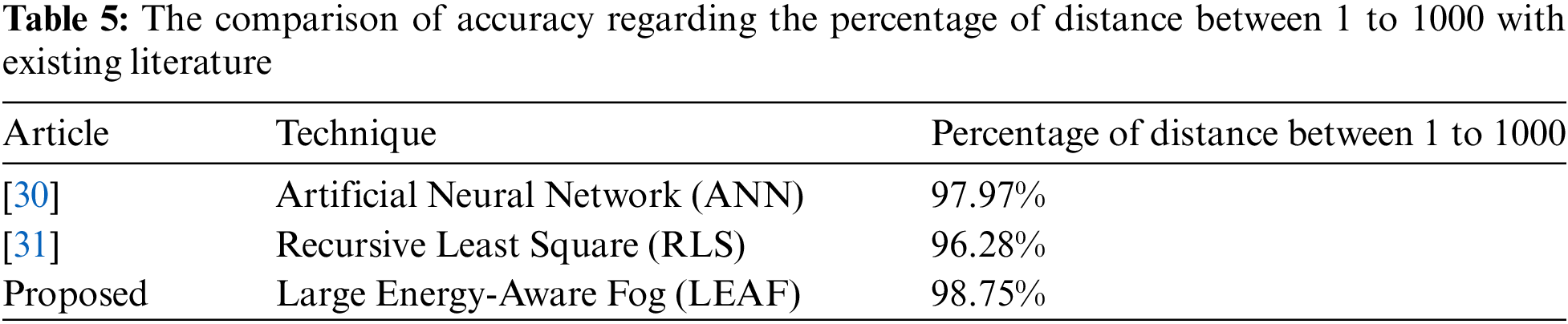

Figure 11: Power usage of infrastructure in the experiment

The second difficulty is that the infrastructure topology is dynamic, and nodes are mobile. Wireless connections have to be re-evaluated periodically to see what nodes are in range of each other. These calculations can have a severe performance impact once there are many possible network connections, for example, when vehicles are able to communicate with each other too. In this case, the number of comparisons would raise with the number of vehicles on the map. One way to deal with this limitation is by applying more advanced methods than linear search such as fixed-radius near neighbor algorithms. Furthermore, domain knowledge can be applied to reduce the number of comparisons. For instance, in the provided example, if a vehicle is very far away from another vehicle at a specific time step, there is minimal time until these two vehicles may get in range of each other. No further comparisons need to be made during this period as given in Table 5.

In this research, an advanced LEAF based technique was introduced that allows for the modeling of large-scale fog computing scenarios for the vehicular based network for executing thousands of streaming applications on a distributed, heterogeneous infrastructure. LEAF features a holistic but detailed energy consumption model that covers the individual infrastructure components and the applications running on it. Unlike most existing simulators, which focus exclusively on energy consumption of data centers or battery-constrained end devices, LEAF additionally takes the power requirements of network connections into account. This is particularly relevant in the context of IoT since mobile communication technologies such as 4G LTE or 5G are comparatively power-hungry. From an environmental point of view, a general issue with mere technological efficiency gains is that they are often canceled out by so-called rebound effects. The LEAF technique describes that improved efficiency sometimes results in increased demand up to the point where the overall effect can be detrimental. Cloud computing is a notable example of this, where energy efficiency is improving at fast rates; nevertheless, the overall power required by cloud computing is rising every year. Admittedly, improved energy efficiency is not the only reason for the increased demand for cloud computing. A series of experiments were carried out on a prototypical implementation to show that the model is useful and meets its stated requirements. The evaluation demonstrated that LEAF enables the comprehensive analysis of the infrastructure’s power usage and can reveal the cause-effect relationship between task placement and energy consumption. The integration of an adaptive energy-saving mechanism illustrated how the energy consumption of fog computing environments can be further reduced by consolidating workloads and switching off unused computing capacity and the percentage of distance between 1 to 1000 was covered up to 98.75% using the LEAF technique. However, some of the business models existing today, such as offering high-quality video streaming, would certainly not be economical with less efficient hardware from 20 years ago. Instead of aiming solely at further improvements in energy efficiency, an exciting direction for future research could be focusing on the carbon emissions caused by fog computing infrastructures directly. Existing models and simulators do not take into account the fact that the amount of green energy in the grid fluctuates throughout the day. Google recently published an article on how they are planning to shift non-urgent tasks, like processing YouTube videos, to times when renewable power sources provide most of their energy. Similarly, a local lack or surplus of low-carbon energy could influence task placement and workload scheduling in fog computing environments. Extending LEAF with additional data sources like weather data, energy prices, and data on the carbon intensity of the current energy mix will enable research on architectures and algorithms that save money and tones of CO2, rather than kilowatt-hours.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Altinbas University, Istanbul, Turkey for valuable support.

Funding Statement: The research received no funding grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Sefer Kurnaz; methodology, Abduladheem Fadhil Khudhur; software, Ayça Kurnaz Türkben; validation, Abduladheem Fadhil Khudhur; formal analysis, Abduladheem Fadhil Khudhur; writing—original draft preparation, Abduladheem Fadhil Khudhur. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset was being acquired from KAGGLE which is open-source https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/haris584/vehicular-obu-capability-dataset (accessed on 20 January 2023).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. V. Paidi, H. Fleyeh, J. Håkansson, and R. G. Nyberg, “Smart parking sensors, technologies and applications for open parking lots: A review,” IET Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 735–741, May 2018. doi: 10.1049/iet-its.2017.0406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. N. Alsbou, M. Afify, and I. Ali, “Cloud-based IoT smart parking system for minimum parking delays on campus,” in Internet of Things–ICIOT 2019, 2019, pp. 131–139. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-23357-0_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. T. N. Pham, M. -F. Tsai, D. B. Nguyen, C. -R. Dow, and D. -J. Deng, “A cloud-based smart-parking system based on Internet-of-Things technologies,” IEEE Access, vol. 3, pp. 1581–1591, 2015. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2015.2477299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. X. Wang and S. Cai, “An efficient named-data-networking-based IoT cloud framework,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 3453–3461, Apr. 2020. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.2971009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. M. Khalid, K. Wang, N. Aslam, Y. Cao, N. Ahmad and M. K. Khan, “From smart parking towards autonomous valet parking: A survey, challenges and future works,” J. Netw. Comput. Appl., vol. 175, Feb. 2021, Art. no. 102935. doi: 10.1016/j.jnca.2020.102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. H. El-Sayed et al., “Edge of things: The big picture on the integration of edge, IoT and the cloud in a distributed computing environment,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 1706–1717, 2018. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2780087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. A. Pozzebon, “Edge and fog computing for the Internet of Things,” Future Internet, vol. 16, no. 3, Mar. 2024, Art. no. 101. doi: 10.3390/fi16030101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. A. Damianou, C. M. Angelopoulos, and V. Katos, “An architecture for blockchain over edge-enabled IoT for smart circular cities,” in 2019 15th Int. Conf. Distrib. Comput. Sens. Syst. (DCOSS), Santorini Island, Greece, May 2019. doi: 10.1109/dcoss.2019.00092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. M. A. A. Ghamdi, “An optimized and secure energy-efficient blockchain-based framework in IoT,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 133682–133697, 2022. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3230985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. V. K. Kukkala, J. Tunnell, S. Pasricha, and T. Bradley, “Advanced driver-assistance systems: A path toward autonomous vehicles,” IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 18–25, Sep. 2018. doi: 10.1109/MCE.2018.2828440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. W. A. A. Praditasari and I. Kholis, “Model of smart parking system based on Internet of Things,” Spektral, vol. 2, no. 1, May 2021. doi: 10.32722/spektral.v2i1.3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. K. S. Awaisi et al., “Towards a fog enabled efficient car parking architecture,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 159100–159111, 2019. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2950950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. C. Lee, Y. Han, S. Jeon, D. Seo, and I. Jung, “Smart parking system using ultrasonic sensor and Bluetooth communication in Internet of Things,” KIISE Trans. Comput. Pract., vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 268–277, Jun. 2016. doi: 10.5626/ktcp.2016.22.6.268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. A. Shahzad, J. Choi, N. Xiong, Y. -G. Kim, and M. Lee, “Centralized connectivity for multiwireless edge computing and cellular platform: A smart vehicle parking system,” Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput., vol. 2018, pp. 1–23, 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/7243875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. A. Shahzad, A. Gherbi, and K. Zhang, “Enabling fog-blockchain computing for autonomous-vehicle-parking system: A solution to reinforce IoT-cloud platform for future smart parking,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 13, Jun. 2022, Art. no. 4849. doi: 10.3390/s22134849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. W. Shao, F. D. Salim, T. Gu, N. -T. Dinh, and J. Chan, “Traveling officer problem: Managing car parking violations efficiently using sensor data,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 802–810, Apr. 2018. doi: 10.1109/jiot.2017.2759218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. M. Y. Pandith, “Data security and privacy concerns in cloud computing,” Internet of Things Cloud Comput., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 6–11, 2014. doi: 10.11648/j.iotcc.20140202.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. B. H. Krishna, S. Kiran, G. Murali, and R. P. K. Reddy, “Security issues in service model of cloud computing environment,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 87, pp. 246–251, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2016.05.156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. C. Stergiou, K. E. Psannis, B. B. Gupta, and Y. Ishibashi, “Security, privacy & efficiency of sustainable cloud computing for big data & IoT,” Sustainable Comput.: Inform. Syst., vol. 19, pp. 174–184, Sep. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.suscom.2018.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. R. A. Memon, J. P. Li, M. I. Nazeer, A. N. Khan, and J. Ahmed, “DualFog-IoT: Additional fog layer for solving blockchain integration problem in Internet of Things,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 169073–169093, 2019. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2952472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. M. Ma, G. Shi, and F. Li, “Privacy-oriented blockchain-based distributed key management architecture for hierarchical access control in the IoT scenario,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 34045–34059, 2019. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2904042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. P. K. Sharma, N. Kumar, and J. H. Park, “Blockchain-based distributed framework for automotive industry in a smart city,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform., vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 4197–4205, Jul. 2019. doi: 10.1109/TII.2018.2887101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. V. K. Sarker, T. N. Gia, I. Ben Dhaou, and T. Westerlund, “Smart parking system with dynamic pricing, edge-cloud computing and LoRa,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 17, Aug. 2020, Art. no. 4669. doi: 10.3390/s20174669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Z. Liu, P. Dai, H. Xing, Z. Yu, and W. Zhang, “A distributed algorithm for task offloading in vehicular networks with hybrid fog/cloud computing,” IEEE Trans. Syst., Man, Cybern.: Syst., vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 4388–4401, Jul. 2022. doi: 10.1109/TSMC.2021.3097005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. H. Cho, Y. Cui, and J. Lee, “Energy-efficient cooperative offloading for edge computing-enabled vehicular networks,” IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun., vol. 21, no. 12, pp. 10709–10723, Dec. 2022. doi: 10.1109/TWC.2022.3186590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. S. Ghanavati, J. Abawajy, and D. Izadi, “An energy aware task scheduling model using ant-mating optimization in fog computing environment,” IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 2007–2017, Jul. 2022. doi: 10.1109/TSC.2020.3028575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. M. Chaqfeh and A. Lakas, “A novel approach for scalable multi-hop data dissemination in vehicular ad hoc networks,” Ad Hoc Netw., vol. 37, pp. 228–239, Feb. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.adhoc.2015.08.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. U. M. Malik, M. A. Javed, S. Zeadally, and S. Ul Islam, “Energy-efficient fog computing for 6G-enabled massive IoT: Recent trends and future opportunities,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 9, no. 16, pp. 14572–14594, Aug. 2022. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2021.3068056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. L. Lu, T. Wang, W. Ni, K. Li, and B. Gao, “Fog computing-assisted energy-efficient resource allocation for high-mobility MIMO-OFDMA networks,” Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput., vol. 2018, no. 1, Jan. 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/5296406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. M. Sookhak et al., “Fog vehicular computing: Augmentation of fog computing using vehicular cloud computing,” IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 55–64, Sep. 2017. doi: 10.1109/MVT.2017.2667499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. U. Farooq, M. W. Shabir, M. A. Javed, and M. Imran, “Intelligent energy prediction techniques for fog computing networks,” Appl. Soft Comput., vol. 111, Nov. 2021, Art. no. 107682. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools