Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Scalable and Generalized Deep Ensemble Model for Road Anomaly Detection in Surveillance Videos

1 Department of Information Technology, Quaid-e-Awam University of Engineering, Science & Technology, Nawabshah, 67480, Pakistan

2 Department of Software Engineering, Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology, Karachi, 75000, Pakistan

3 Electrical Engineering Department, College of Engineering, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11421, Saudi Arabia

4 School of Business, Torrens University, Sydney, NSW 2007, Australia

5 School of Engineering and Information Technology, The University of New South Wales (UNSD), Canberra, ACT 2604, Australia

* Corresponding Authors: Sarfaraz Natha. Email: ; Mohammad Siraj. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 3707-3729. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.057684

Received 25 August 2024; Accepted 29 November 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

Surveillance cameras have been widely used for monitoring in both private and public sectors as a security measure. Close Circuits Television (CCTV) Cameras are used to surveillance and monitor the normal and anomalous incidents. Real-world anomaly detection is a significant challenge due to its complex and diverse nature. It is difficult to manually analyze because vast amounts of video data have been generated through surveillance systems, and the need for automated techniques has been raised to enhance detection accuracy. This paper proposes a novel deep-stacked ensemble model integrated with a data augmentation approach called Stack Ensemble Road Anomaly Detection (SERAD). SERAD is used to detect and classify the four most happening road anomalies, such as accidents, car fires, fighting, and snatching, through road surveillance videos with high accuracy. The SERAD adapted three pre-trained Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) models, namely VGG19, ResNet50 and InceptionV3. The stacking technique is employed to incorporate these three models, resulting in much-improved accuracy for classifying road abnormalities compared to individual models. Additionally, it presented a custom real-world Road Anomaly Dataset (RAD) comprising a comprehensive collection of road images and videos. The experimental results demonstrate the strength and reliability of the proposed SERAD model, achieving an impressive classification accuracy of 98.7%. The results indicate that the proposed SERAD model outperforms than the individual CNN base models.Keywords

Nomenclature

| CCTV | Closed Circuit Camera |

| CNN | Convolution Neural Network |

| SERAD | Stack Ensemble Road Anomaly Detection |

| RAD | Road Anomaly Dataset |

| VTSS | Video Traffic Surveillance System |

| DCNN | Deep Convolution Neural Network |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| CVIS | Cooperative Vehicle Infrastructure |

| MSFF | Multi-Scale Feature Fusion |

| VD | Violence Detection |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| RPN | Region Proposal Network |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| EL | Ensemble Learning |

| ReLU | Rectifier Linear Unit |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| Grad-CAM | Gradient-Weighted Class Activation Mapping |

Road anomaly detection is suggested to recognize events that significantly differ from the usual instances seen on roads in real-world situations [1]. In the last decade, Internet of Things (IoT) based devices such as CCTV cameras have been placed in different municipal and personal sector locations for surveillance and security purposes. The surveillance system recognizes normal and abnormal events to ensure safety and security. CCTV cameras are designed to identify anomalies or unusual activities, triggering alerts to the appropriate departments [2]. Surveillance systems are necessary for monitoring people and places for public safety. These systems have been producing large data. However, the large volume of data, and the irregularity of incidents like theft, violence, abnormal behavior, or other crimes make it difficult to identify. Manually monitoring large amounts of video data is labor-intensive and prone to mistakes due to human fatigue. Furthermore, abnormal events are much less common than normal behavior. The job becomes repetitive to increase the chances of human blunder. A key challenge in road anomaly detection is managing imbalanced datasets, where normal road images vastly outnumber those depicting anomalies like accidents or unusual incidents [3]. Models are frequently biased towards frequent occurrences because of this imbalance, which impairs their capacity to precisely identify uncommon but significant abnormalities. Since it has a direct impact on the model’s ability to recognize significant, sporadic events, resolving this issue is more complicated than determining how long data collecting takes. A further layer of difficulty arises from the subjective nature of recognizing and labeling images of road anomaly, necessitating costly manual labeling or domain adaptation procedures to close the gap between simulated and real-world data. These challenges must be addressed through various approaches: cost-effective labeling, imbalance dataset and domain adaptation [4], improving the accuracy and dependability of automatic road anomaly recognition systems that eventually provide safer and more effective road transportation systems. Anomaly detection is often treated as an unsupervised learning problem [5] in which the data is unlabeled. This technique is based on the concept that typical patterns occur frequently, and abnormal events are uncommon. One of the disadvantages of this technique is that it may classify all strange events as abnormal. Some clustering methods in unsupervised learning seek to discriminate between normal and abnormal events in the feature space [6]. In addition, the semi-supervised anomaly detection method is neither as accurate as unsupervised models nor as dependable on labeled data as the supervised approach [7]. The goal of this approach is to minimize the differences between supervised and unsupervised methods while acknowledging that certain studies embody characteristics of semi-supervised learning [8]. A video traffic surveillance system (VTSS) is a method that uses video cameras to identify road anomalies automatically through road videos. The VTSS recognizes the “accident” and “no accident” categories while reducing human involvement in traffic data collection and monitoring [9]. However, human overseeing is still needed for issues like car fires or suspicious activities. Researchers are improving road anomaly detection by using advanced deep-learning algorithms for video analysis. Deep learning, especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [10] has become a powerful tool in computer vision, excelling in object recognition and outperforming methods for detection. Yang et al. [11] made a Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) to determine traffic events using vehicle movement data. However, this DCNN doesn’t look at how things change over time in video frames. Instead, it focuses only on what is happening in each frame separately. On the other hand, Bortnikov et al. [12] created a Three-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (3DCNN) to detect traffic accidents. The 3DCNN way of understanding movement in space and time gave clear results but didn’t connect different features well. However, it struggles to accurately spot traffic incidents and indifferent illumination situations. By independently extracting relevant features, the DCNN dramatically enhances image classification skills, leading to improvements in accuracy and performance in image categorization tasks [13]. Large data sets are required to construct Deep Learning (DL) models, increasing training time. On the other hand, obtaining a considerable volume of data is a significant problem for researchers [14]. However, transfer learning (TL) [15] has been presented as a highly advantageous and popular model using pre-trained weights on the Image Net dataset. Different deep learning models, most notably the transfer learning model, have been used to detect anomalies in the road network. The CNN model is important for testing transfer learning as it is often used to process raw images and enhance classification performance [16]. In addition, the ability of CNN models to extract the best features from the images [17]. This study uses deep learning algorithms to provide a robust, scene-invariant, and real-time road anomaly-detecting framework. Initially, a new dataset named Road Anomaly Dataset (RAD) included four significant road anomaly categories: accidents, vehicle fires, fighting, and snatching (gunpoint). The RAD dataset carefully collected videos from Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) cameras under various lighting conditions, and positions of cameras, including different camera distances which may affect video quality. This dataset provides a strong base for training and testing the road anomaly detection system. The main contributions of this study are:

• The proposed SERAD model is based on the deep stack ensemble of various CNN models used to recognize road anomalies such as accidents, car fires, fighting, and snatching (gunpoint) from road surveillance videos. This model achieves exceptionally high recall and accuracy by utilizing a stacking ensemble technique that associates several base-level classifiers of CNN models such as VGG19, InceptionV3, and ResNet50 with a meta-learner classifier and overcomes misclassification using a data augmentation technique.

• The benchmark of this research is to create a new Road Anomaly Dataset (RAD) consisting of images and videos captured by surveillance cameras and other internet resources (YouTube, Netflix).

• We evaluated the performance of the SERAD model using the RAD dataset based on precision, recall, accuracy, F1-score, and ROC.

• The SERAD model achieved 98.7% accuracy which is remarkable as compared with prior studies. Additionally, classifying the anomaly images to improve detection dependability along with interpretability through the Grad Camp technique.

We organize the rest of the paper as follows: Related work is given in Section 2 and the architecture of the proposed methodology is in Section 3. Section 4 illustrates the road anomaly detection and classification results. Section 5 describes the conclusion, limitations, and future work.

In recent decades, extensive research has been directed toward intelligent transportation systems, with a primary focus on creating automated incident detection systems designed to efficiently address everyday occurrences. Smart city development has been greatly accelerated by innovations, but preserving situational awareness in real-time is essential to guarantee their security. Furthermore, the subjective nature of recognizing and classifying road abnormalities presents an additional difficulty, sometimes necessitating costly manual labeling or domain adaption strategies to balance the disparities between simulated and actual situations. We investigated and determined which deep learning algorithms are most suited for road anomaly recognition through road surveillance videos.

Surveillance is the practice of keeping an eye on people’s actions and behavior to control and safeguard them. Most surveillance systems have been adopted for security. The most efficient way of surveillance is to use CCTV cameras to observe people and objects from a distance. Video cameras sometimes referred to as closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras, are used in security systems and have become increasingly common in recent years. The inexpensive cost of the technology and growing security concerns are the reasons for this growth in popularity. By spotting unusual patterns and irregular actions in video data, these technologies are used to identify anomalous behavior [18]. Surveillance systems used in the modern world produce large volumes of video data to monitor streets, roads, and highways [19]. The data patterns that deviate from expected behavior are called anomalies [20].

2.1 Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) Approach

Many researchers have studied anomaly detection using image and video classification using a CNN-based approach. For instance, Zhou et al. [21] proposed a spatial-temporal based on the CNN model for anomaly detection, which presented some success. The advent of deep learning brought significant advancements in road anomaly recognition, leading to a predominant use of deep neural networks in recent studies. Kim et al. [22] proposed an exclusive approach to traffic accident identification using a pre-trained ResNet and extracted the spatiotemporal used 3D-CNN with a feature pyramid network architecture. This suggested method retains good detection accuracy. In terms of accuracy and recall metrics, the experimental findings show that the proposed model outperformed the results. However, its recognition of the dataset’s quality might lead to a reduction in efficiency in inclement weather or low light. Similarly, an enhanced convolutional neural network (ECNN)-based model for the Suspicious Activity Detection System (SAD) was presented by Selvi et al. [23]. Using security camera footage that might be used to recognize odd behaviors like fights, this proposed model aims to successfully detect strange activity identification. This model achieved 97.05% precision and 96.74% accuracy for recognizing suspicious activities. However, this proposed model is not suitable under low illumination and long-distance captured videos.

2.2 Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) Approaches

Some research adopted the hybrid and multi-model approach to abnormal events and behavior detection and classification. There have been quite a few contributions made by researchers using the real-time activity recognition deep learning model RNN. This study [24] constructed a unique image dataset called CAD-CVIS and proposed an autonomous automobile accident detection system utilizing the Cooperative Vehicle Infrastructure System (CVIS) to improve the detection efficiency of tiny objects, they integrated a loss function with dynamic weights and Multi-Scale Feature Fusion (MSFF). However, the primary drawback of this study is the communication overhead brought on by the real-time scene being captured by roadside cameras and sent to distant computers. In this study proposed by Phyo et al. [25] used two human activity datasets to examine human action recognition (HAR) using deep learning techniques and picture pre-processing, they developed human action recognition as a skeletal-joint motion to monitor the elderly, suspicious people, and potentially dangerous objects in public areas. However, it is less effective due to the restricted motion sets. A computationally intelligent Violence Detection (VD) technique has been presented by Ullah et al. [26]. Initially, a lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is used to analyze the video stream that was taken by a visual sensor. As a result, from the informative images, temporal optical flow characteristics are retrieved. Ultimately, a multi-layer long and short-term memory (LSTM) network is integrated to yield a final feature map that identifies patterns of violence within the shot sequences. Even if the technique accuracy appears to have improved somewhat, it is notable that the accuracy obtained in outside monitoring stays at 49%.

2.3 One-Stage and Two-Stage Deep Learning Model

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) is a one-stage deep learning model, YOLO takes input images and distributes them into

2.4 Hybrid Deep Learning Approach

The hybrid deep learning model for road anomaly detection by videos proposed by Tutar et al. [28] studied joining multiple machine learning algorithms with both pixel-based (PBVAD) and frame-based (FBVAD) methods. This model has proven high-performance anomaly detection on the publicly available UCF-Crime dataset, which consists of 128 h of real-world video footage. Utilizing the FBVAD-kNN algorithm, the model yielded an average AUC performance measure of 98.0%, while the PBVAD-MIM method produced an average of 80.7%. One of the model’s shortcomings is the absence of temporal information integration, which might enhance performance by accounting for earlier frames for anomaly identification. An FRCNN model for automatically identifying knives and pistols in surveillance footage was proposed by Berardini et al. [29]. The weapon images in the group were taken from the Weapon detection dataset, which is accessible to the public and contains important information about criminal activity on the road. Similarly, Hnoohom et al. [30] proposed a study that is based on the FRCNN-based method for automatically identifying abnormalities like firearms. However, a notable flaw in the model is the limited dataset for knife and pistol weapon images, which were collected exclusively during daytime and under bright illumination conditions. Therefore, the detection of weapon images may yield inaccurate results in low illumination conditions. The scarcity of relevant datasets is a serious hurdle to deep learning-based autonomous road anomaly identification. As a useful fine-tuning strategy, data augmentation must be used to expand datasets and apply changes that might improve model performance.

2.5 Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) Approach

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) are an admired approach in anomaly detection due to their ability to generate realistic data by learning the underlying data division [31]. GANs consist of a generator and a discriminator. These models engage in a competitive process, where the generator learns to produce increasingly realistic data, and the discriminator improves its ability to distinguish between real and generated data. GANs are valuable for anomaly detection in two ways. Firstly, they can create rare or hard-to-obtain anomalous examples. Secondly, they can model the normal data distribution, enabling them to detect anomalies or outliers effectively. For instance, in this study, Vu et al. [32] presented a flexible multi-channel generative model to detect anomalies for a supervised approach in surveillance video streams. CGAN stream predicted the future information and applied PSNR technique to encode prediction error into features vector. This study surpasses state-of-the-art performance on 4 different datasets. However, this study has some limitations for online detection to get trouble when brand new abnormal actions suddenly occur without existing in the previously learned database.

Similarly, in this study, Singh et al. [33] proposed an unsupervised anomaly detection approach based spatiotemporal generative Adversarial Network (STemGAN). This approach consists of a generator and discriminator. The generator learns key features of spatial and temporal information from the video context, and the discriminator improves the model’s ability to distinguish between real and generated data. The proposed model achieved an AUC score of 97.5% on UCSDPed2, 86.1% on CUHK Avenue, 90.5% on the Subway entrance, and 95.3% on the Subway exit. However, this model lacks the ability to generalize across different types of road anomalies, especially those that occur under low illumination. GAN utilized high-quality image reconstruction and data augmentation [34] approach. GAN used a convolutional generator to learn the distribution of key features and a discriminator to analyze the generated output. These models are trained competitively using an adversarial discriminator loss [35] instead of rebuilding. Thereby overwhelming the limitation of DCNN-based models. This technique was used by Yu et al. [36] for reconstruction-based anomaly detection (AD), improving on current Autoencoder (AE) models to get beyond the challenges with reconstruction loss and presenting a new approach to AD. Similarly, a prediction-based approach was presented by Liu et al. [37] to identify occurrences that deviate from expected patterns by projecting future frames. They put into practice a modified AE-based GAN architecture, extracting motion characteristics from the anticipated pictures by applying optical flow restrictions and utilizing stacked convolutional layers to collect spatial information.

Based on our extensive literature review, existing methodologies in previous research need to be more advanced to address several limitations. These include not enough data frames in video clips, challenges with increasing false alarm rates, and a decline in generalization capacity, which hinders real-time detection and classification of anomalies. Previous studies have examined specific road anomalies such as accidents, suspicious activities, vehicle fires, and violence. This study tackles the issue of insufficient data frames in video clips by proposing a unified framework based on deep-stack ensemble learning [38].

There is a scarcity of studies focusing on applying ensemble methods to road anomaly classification. Our framework aims to automate the classification of different types of road anomalies. This section explicates the methodology of the SERAD model, the first stacked ensemble design utilizing VGG19, InceptionV3, and ResNet50 tailored for road anomaly recognition. The objective is to reduce detection errors and surpass the performance of various existing models. These models were chosen for their outstanding image processing performance and recognized success in real-time detection applications. The proposed SERAD model automatically classifies four kinds of road anomalies: road accidents, car fires, fighting, and snatching (gunpoint). The SERAD is the first deep-stacked ensemble architecture using data augmentation for road anomaly detection and classification. To further improve the classification accuracy a transfer learning approach has been employed. Transfer learning (TL) is essential and beneficial when training data is limited, and computational power is constrained. The core idea of TL is to use pre-trained models on large datasets to improve classification performance. The transfer learning approach is inspired by how people use past knowledge to solve new problems efficiently. Traditional machine learning works best when the training and testing data are small. However, in real-world situations, it can be hard and expensive to get new data that fits this condition. TL helps by knowledge from a linked domain, cutting down the need and cost of collecting entirely new data [39]. The study employed several transfer learning network classifiers namely VGG19, ResNet50, and InceptionV3.

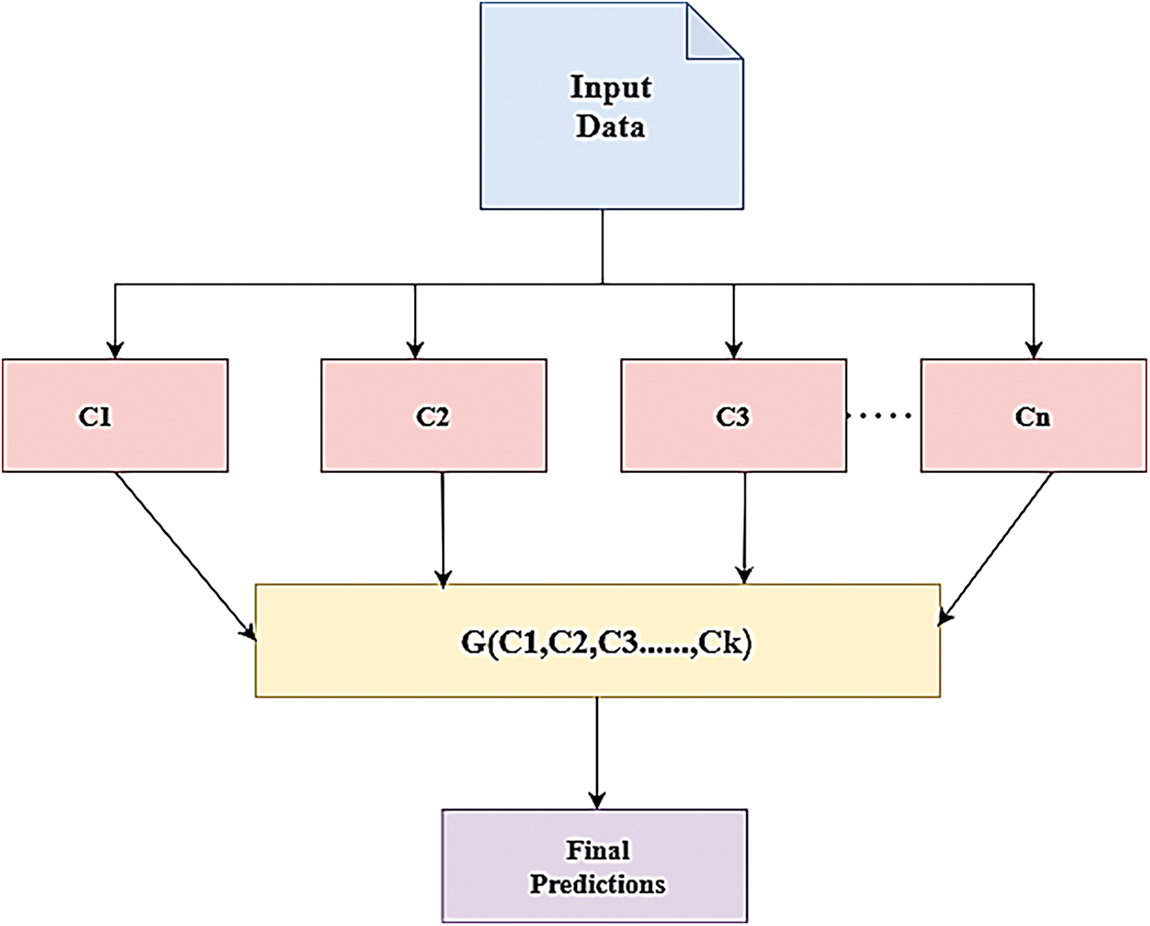

The EL is another popular machine learning approach that is especially useful in supervised learning, to increase the capacity of models to generalize [40]. It may have sophisticated methods such as averaging, and weighted averages, and straightforward methods like boosting, stacking, and bagging [41]. These methods give several ways to access the underlying restrictions in a single model and greatly increase prediction accuracy. Ensemble learning increases detection accuracy by combining varied learning strategies to mitigate issues such as variation, bias, and overfitting, which significantly affect model performance. This approach leverages the strengths of multiple models to effectively address these challenges [42]. To enhance classification performance, a technique known as stacking combines many models in an ensemble manner. Typically, a meta-learner uses the predictions made by the base classifier to classify the dataset, and the meta-classifier uses these predictions as features. Fig. 1 demonstrates the general architecture of ensemble learning. Each ensemble contains a group of baseline classifiers trained on input data. These classifiers generate predictions that are combined or aggregated to produce a final prediction [43]. In ensemble learning, the basic framework implies using an aggregation function G to combine a group of baseline classifiers C1, C2, …, Ck, towards predicting a single output. The features of dimension m, and n is a size of the dataset, where D = {(xi, yi)}, 1 ≤ i ≤ n, xi ∈ Rm, the prediction of the output based on this ensemble method is given Eq. (1).

Figure 1: The building of the Ensemble learning approach

The feature selection process varies for the same training set of data in heterogeneous classifiers. Researchers generally find homogeneous ensemble approaches simpler to understand and implement, which makes them more appealing. Additionally, homogeneous ensembles are less expensive to construct than heterogeneous ones.

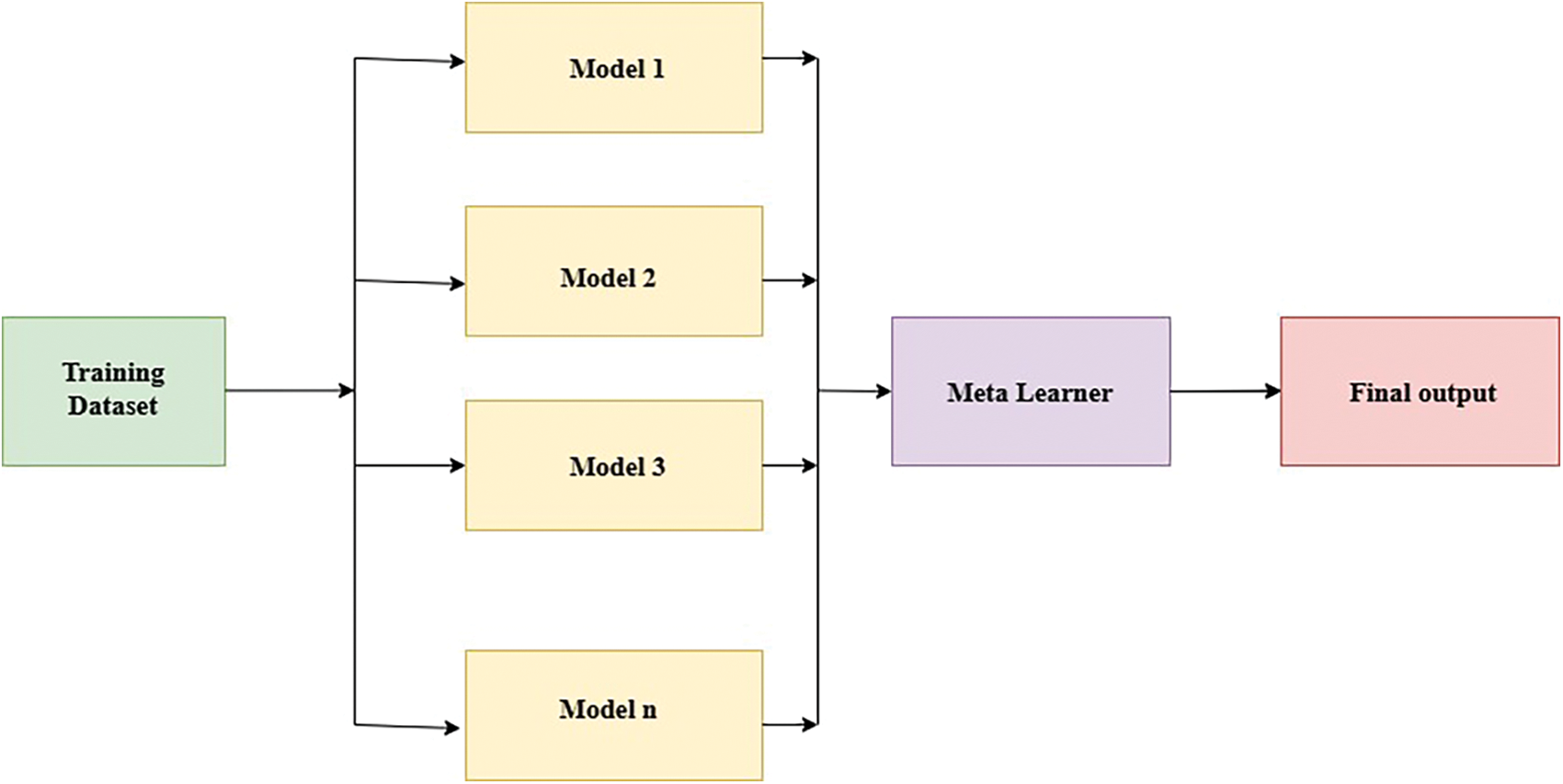

3.2 Stacking Ensemble Learning Approach

The stacking Ensemble learning approach combines information from multiple predictive models to generate a new model known as a meta-learning model [44]. Stacking involves using a meta-classifier to evaluate inputs and outputs from multiple models, assigning weights to determine the best-performing models while discarding fewer efficient ones. This method integrates predictions from diverse base classifiers, each trained with different learning methods on the same dataset [45]. In stacking, different models are joined for prediction with inputs from each subsequent layer to generate a new set of predictions. Ensemble stacking, also known as mixing, consolidates all the information to make predictions or classifications. Fig. 2 depicts the structure of the stacking framework.

Figure 2: The stacking framework uses different models on the input dataset, with a meta-learner combining their outputs to make the final predictions

3.3 Road Anomaly Dataset (RAD)

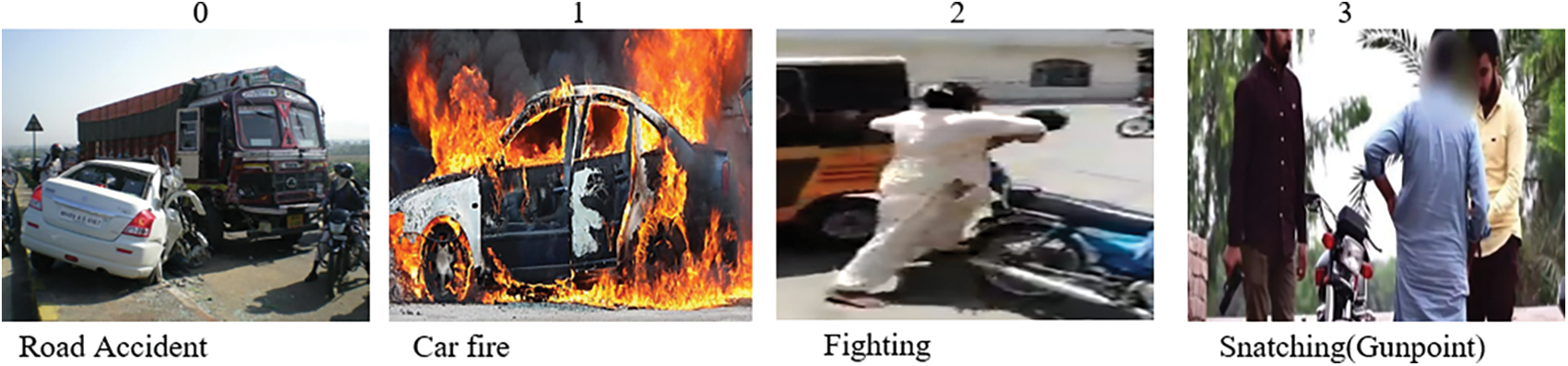

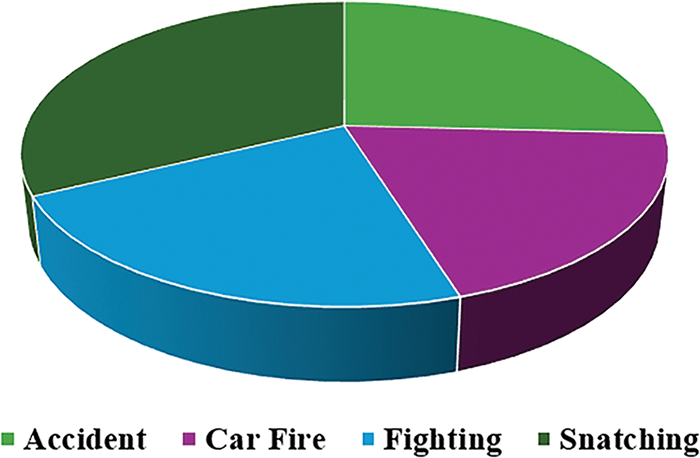

The absence of standard datasets impedes research progress in this sector, underlining the need for comprehensive and diverse datasets to assist the training and testing of strong road anomaly recognition models. Therefore, a custom dataset was developed by collecting information from diverse city locations using CCTV cameras and social media sources, focusing on four different types of road abnormalities such as road accidents, fighting, car fires, and snatching. The RAD dataset [46] comprises numerous frames extracted from videos captured by surveillance cameras under varying lighting conditions and camera angles. The dataset consists of 120-s recorded road surveillance videos. Road anomaly images are extracted from the road videos using the OpenCV library and stored in training, testing, and validation folders. Each folder contains four subfolders, with each subfolder consisting of images of accidents, car fires, fighting, and snatching. The train folder is 70%, the test folder 20%, and the valid folder 10% of images. The RAD dataset has four distinct categories. Each category is assigned a label from 0 to 3: 0 represents accidents, 1 represents car fire, 2 represents fighting, and 3 represents snatching (gunpoint), as shown in Fig. 3. Table 1 shows the overall statistics of the RAD dataset and Fig. 4 represents the division of the RAD dataset.

Figure 3: The RAD dataset consists of numerous road anomalies

Figure 4: Distribution of road anomaly dataset

3.4 SERAD: Stacked Ensemble Road Anomaly Detection Model

SERAD architecture designed for road anomaly recognition is illustrated in Fig. 5. The CNN models VGG19, InceptionV3, and ResNet50 were selected for their strong performance in our deep-stacked ensemble model. The SERAD model is a two-level stacked ensemble that merges multiple classification algorithms to enhance overall performance. Ensemble learning proves advantageous over single deep models by reducing detection errors, improving accuracy, and enhancing robustness. We integrated three CNN models using a stacked ensemble approach to maximize effectiveness.

Figure 5: The SERAD model is proposed for road anomaly detection

The prediction vectors from these base models merged and utilized as features in the meta-learner, which is a fully connected neural network architecture for multi-class classification. The meta-learner undergoes training on the training set, featuring a batch normalization layer following a dense layer with 128 neurons and a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function. Additionally, it includes a dropout layer and an additional dense layer with 64 neurons.

The final dense layer employs a dropout rate of 0.2 and a Softmax activation function to classify images into their respective categories. Customized classification layers are essential for the reliable identification of road anomalies in various models. The preprocessed training dataset has been used to train these models. The performance of the trained models has been appropriately evaluated using the validation set. The model performance has been assessed, providing valuable insights into the models’ capabilities, through the creation and analysis of predictions for the validation data set. The feature matrix from which the input features for the meta-classifier model are obtained is constructed using the matching class labels and stacking predictions. Since road anomaly photos are mostly visual, it’s imperative to effectively extract characteristics. An optimizer function is used to modify the weights and learning rate of the model.

3.5 Tuning Hyper-Parameter and Model Optimization

In deep learning, hyperparameters are crucial for managing the learning process of the model and need to be carefully adjusted. The model performance is greatly impacted by these factors, which also affect the network design and training. Deep learning model development requires parameter optimization since optimized hyperparameters improve performance. Models with fewer weights and parameters are frequently designed to get the highest accuracy. It might be difficult to choose the ideal hyperparameters and calls for adjustment to experimental values. To train deep neural networks, momentum, stochastic gradient descent, RMSprop, and Adam are popular optimization methods. For the investigation, four pre-trained models were trained across 50 epochs with a fixed batch size. We applied the Adam optimizer with fine-tuning parameters of learning rate, epochs, and batch size. The actual loss function in all models used was categorical cross-entropy, with an additional 0.2 dropout rate to overcome the overfitting issue. The meta-learner conceived fully connected neural architecture and was trained with feature vectors from the foundational models across 50 epochs with a batch size of 64. The features from RMSProp and SGD were incorporated by the meta-learner using the Adam optimizer along with a learning rate of 1r-3. L2 regularization was used during training to further address overfitting, with a coefficient of 1r-4.

We evaluated the proposed approach on the benchmark datasets that are commonly used for classifying different types of road anomalies.

Hardware architectures are crucial for efficient model training, particularly in deep learning, where high-level libraries like TensorFlow handle computationally intensive tasks. NVIDIA was chosen for its superior support for deep learning computations, with all evaluations performed using an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 GPU.

The neural network architecture was implemented in Python, using Keras and TensorFlow frameworks. The approach was evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, confusion matrix, and ROC curve, with results compared against state-of-the-art methods for each dataset.

To measure the efficiency of the SERAD model, we adopted some key performances such as ROC curve, confusion matrix, F1-score, accuracy, precision, and recall. We measured the model performance by examining the true positives (positives that are correctly recognized), false positives (positives that are wrongly identified), true negatives (negatives that are correctly identified), and false negatives (negatives that are incorrectly identified). The results show that the SERAD model is more effective in detecting road anomalies.

4.3 Result Analysis of SERAD Ensemble Model

This section presented the CNN base models and SERAD model efficiency comparison to identify different types of road anomalies. The accuracy learning curve produced by each base model is displayed in Fig. 6. The suggested model training accuracy has been increasing quickly with every epoch. The proposed model’s loss values do not change considerably as shown in Fig. 7, indicating the model converges effectively and does not show signs of under-fitting. A comparison study between the proposed model and the base models was done to confirm the efficiency of the suggested model. The findings are displayed in Table 2, along with the proposed SERAD model’s quantitative outcomes and the performance of each model in terms of F1-score, accuracy, recall, and precision.

Figure 6: Training and validation accuracy of the SERAD model

Figure 7: Training and validation loss of the SERAD model

The VGG19 base model presented the declined performance on the RAD dataset, reaching an average of precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy are 88.5%, 89.1%, 88.6%, and 89.9%, respectively. The InceptionV3 base model achieved an average precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy are 92.2%, 93.7%, 92.5%, and 93.8%, respectively. The ResNet50 has a remarkable average of precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy at 96.5%, 96.8%, 96.2%, and 96.9%, respectively. Each model we utilized in the study performed efficiently on its own. To capitalize on each model’s advantages, therefore we chose to integrate them using the stack ensemble learning approach. The suggested model had the best performance with an average of precision 98.3%, recall of 98.5%, F1-score 98.3%, and accuracy of 98.7%, respectively.

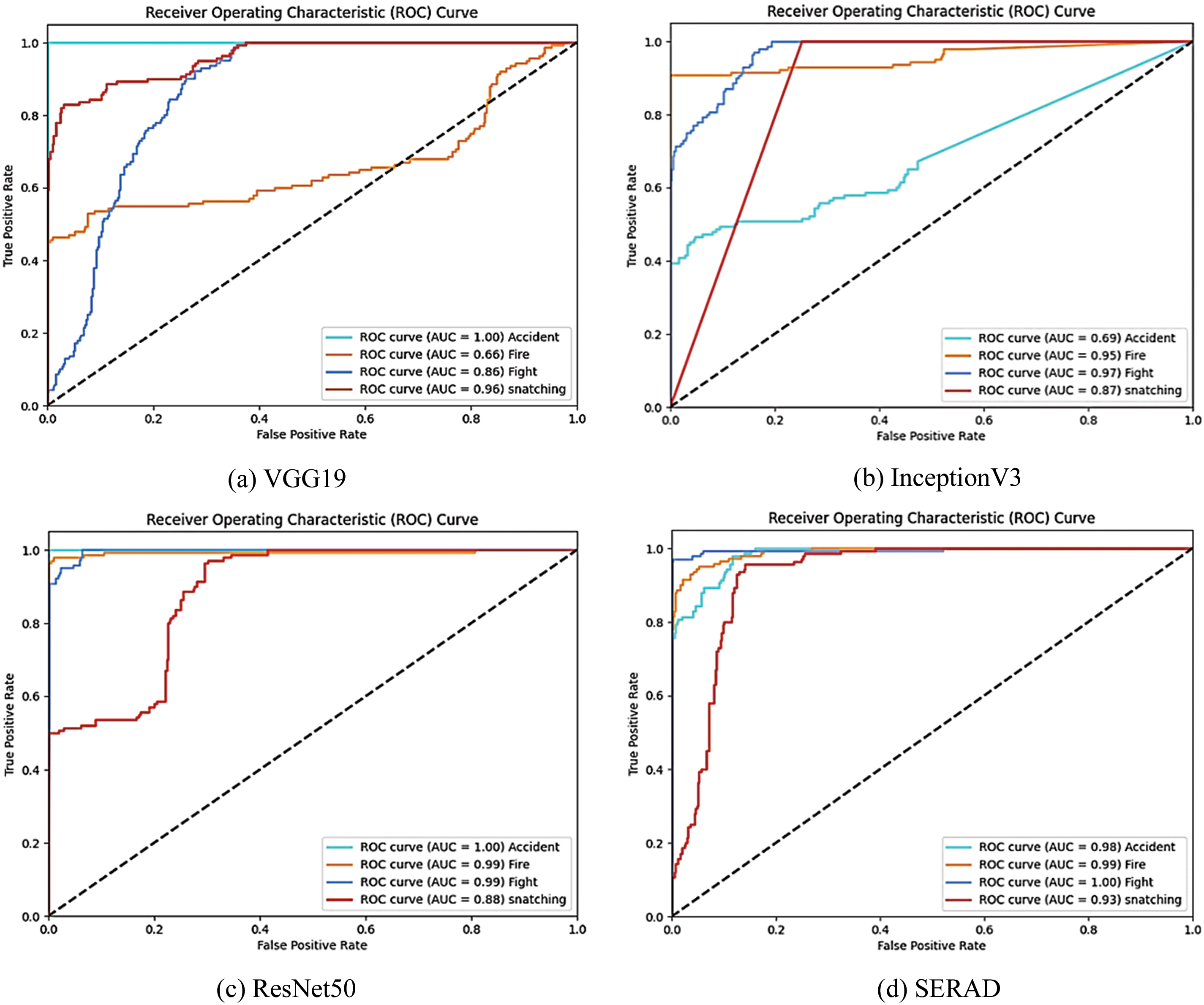

The proposed model surpasses in generalization compared to other models. Analysis of the SERAD confusion matrix vs. individual pre-trained models shows correct execution and reduced misclassification presented in Fig. 8. The framework of SERAD seems to be great for classifying road anomaly images from video into many classes. Stability is efficiently evaluated using the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve presented to measure model performance.

Figure 8: Confusion matrix of the individual model and the proposed SERAD model

The true-positive and false-positive rates in a model are balanced by the ROC curve as seen in Fig. 9. The ROC curves and AUC scores for each class of the base models (VGG19, InceptionV3, and ResNet50) were utilized in the deep stack ensemble as well as the proposed SERAD model. The SERAD model demonstrated stability in categorizing road anomaly images, as seen by its perfect AUC of 1 for fighting, 0.98 for accidents, 0.99 for car fires, and 0.93 for snatching.

Figure 9: ROC Curve of the individual model and the proposed SERAD model

To evaluate the trained model, we tested the model on the unseen dataset of different videos. We tested a video into the model individually and evaluated the results. The implementation repeated the input videos on a screen, labeling each frame with the detected label as illustrated in Fig. 10. In the first scene, we tested a video of a car accident where the video resolution was low but the model correctly recognized accident activity with class label 0. In the second situation, we tested a video of a car fire on the road in daylight. The model correctly identified the car fire with a class label. In the third scenario, we tested a video demonstrating fighting on the road in the crowd. The model correctly recognized the fight scene with class label 2. In the fourth situation, we tested a video of a suspicious action where a person was holding a small gun to perform a suspicious act. The model correctly identified the action as snatching, assigning it a class label of 3.

Figure 10: The test results of the proposed SERAD model

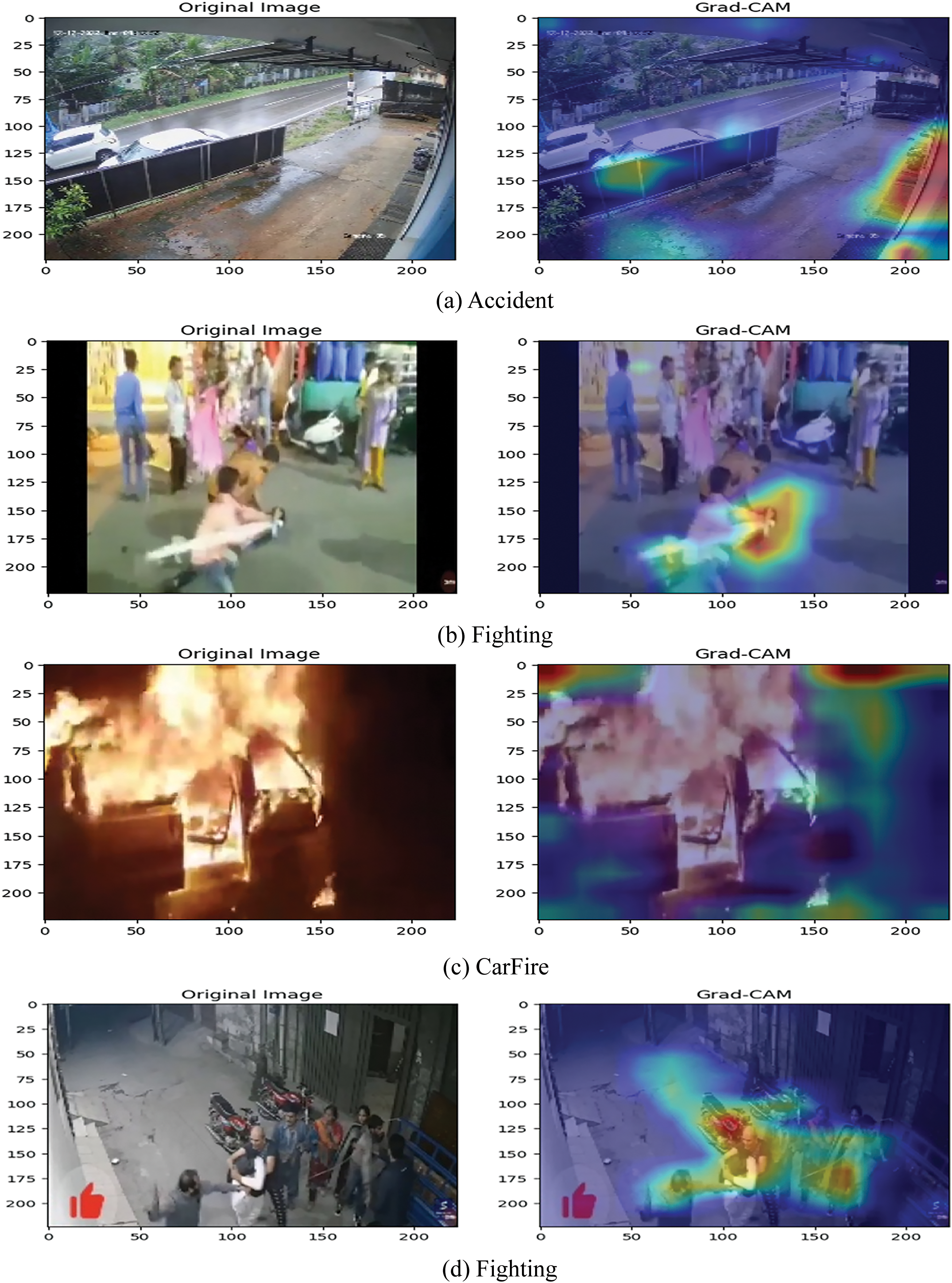

The deep learning models enhanced the interpretability for the classification of road anomalies. We used enhanced visualization techniques named Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM). Grad-CAM uses the gradients of the output of the model for a target class and flows into the final convolutional layer to generate a coarse localization map emphasizing the important areas in the image for forecasting. Finally, the convolutional layer captures high-level features in the image that are crucial for making predictions. Grad-CAM can enhance trust in automated systems. The Grad-CAM visualization of the suggested model is shown in Fig. 11. Grad-CAM is utilized in this model to generate heatmaps that highlight the important areas influencing classification choices. It focuses on gradients that go through the last convolutional layers and represent certain classes like collisions, vehicle fires, combat, and grabbing at gunpoint.

Figure 11: Grad-Cam results of the proposed SERAD model

This section compares SERAD with other deep learning methods, demonstrating its superior performance in recognizing road anomalies. A performance comparison of SERAD and individual CNN base models for road anomaly detection and classification is shown in Table 3. The SERAD model has better accuracy compared to earlier studies. The combination of three different deep convolutional neural networks increased the accuracy and reduced the classification errors. This deep layer of the meta-learner enhanced the ability of the model to learn unique aspects of road anomalies. Its classification performance is further improved by batch normalization and dropout, which expedites training and lessens overfitting issues. These additional layers, which also yield notable performance benefits, set the SERAD model apart from conventional ensemble networks.

5 Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Work

The main objective of this study is to develop an artificial intelligence (AI) system that can automatically detect various types of road anomalies without misclassification. There are three pre-trained CNN models VGG19, InceptionV3, and ResNet50 that make up the deep stack ensemble learning model named SERAD to identify the four types of road anomalies. Therefore, a custom dataset was developed by collecting information from diverse city locations using CCTV cameras and social media sources, focusing on four different types of road abnormalities such as road accidents, fighting, car fires, and snatching. We used data augmentation techniques including rotation, shear, zoom, and flipping throughout the training phase since we saw there was a need for extra data. Experimental results exhibit that the proposed SERAD model achieved a remarkable classification accuracy of 98.7%. This indicates that SERAD significantly enhances the performance of the individual CNN models. The model has some limitations to accurately detect and classify road anomalies in adverse weather situations, such as snow, rain, and fog. These factors can reduce the visibility of image quality which could lead to a decrease in the model efficiency.

The future work will focus on refining the road incident detection systems. This includes implementing advanced algorithms, such as Vision Transformer (ViT) techniques [52] that can better recognize moving obstacles and genuine road incidents, as well as traffic patterns. Additionally, creating algorithms sensitive to environmental disturbance can assist in guaranteeing that scenes are still comprehensible even when the outside world changes. In a variety of real-world scenarios, these developments are intended to increase the accuracy and dependability of road anomaly detection systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through Researchers Supporting Number-RSPD2024R893.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through Researchers Supporting Project Number-RSPD2024R893.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Fareed A. Jokhio, and Sarfaraz Natha; methodology, Sarfaraz Natha, and Mehwish Laghari; software, Mohammad Siraj, and Sarfaraz Natha; validation, Mehwish Laghari, and Saif A. Alsaif; formal analysis, Saif A. Alsaif, and Mehwish Laghari; investigation, Saif A. Alsaif, and Usman Ashraf; resources, Saif A. Alsaif, and Mohammad Siraj; data curation, Saif A. Alsaif; writing original draft preparation, Sarfaraz Natha, and Mohammad Siraj; writing review and editing, Sarfaraz Natha, Fareed A. Jokhio, Mehwish Laghari, and Asghar Ali; visualization, Usman Ashraf, and Sarfaraz Natha; supervision, Fareed A. Jokhio, Mehwish Laghari, and Sarfaraz Natha; project administration, Mohammad Siraj, Saif A. Alsaif, and Sarfaraz Natha; funding acquisition, Mohammad Siraj, Saif A. Alsaif, and Usman Ashraf. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sarfaraznatha/road-anomaly-dataset (accessed on 02 June 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. G. Pang, C. Shen, L. Cao, and A. V. D. Hengel, “Deep learning for anomaly detection: A review,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 1–38, 2022. doi: 10.1145/3439950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. T. N. Nguyen and J. Meunier, “Anomaly detection in video sequence with appearance-motion correspondence,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Comput. Vis., Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019, pp. 1273–1283. [Google Scholar]

3. F. A. Memon, U. A. Khan, A. Shaikh, A. Alghamdi, P. Kumar and M. Alrizq, “Predicting actions in videos and action-based segmentation using deep learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 106918–106932, 2021. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. S. Natha, “A systematic review of anomaly detection using machine and deep learning techniques,” Quaid-e-Awam Univ. Res. J. Eng. Sci. Technol, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 83–94, 2022. doi: 10.52584/QRJ.2001.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. L. Ruff et al., “Deep semi-supervised anomaly detection,” 2019. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.1906.02694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Y. Tang, X. Wang, and H. Lu, “Intelligent video analysis technology for elevator cage abnormality detection in computer vision,” in 2009 Fourth Int. Conf. Comput. Sci. Converg. Inform. Technol., Seoul, Republic of Korea, IEEE, 2009, pp. 1252–1258. doi: 10.1109/ICCIT.2009.206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. J. Feng, C. Zhang, and P. Hao, “Online learning with self-organizing maps for anomaly detection in crowd scenes,” in 2010 20th Int. Conf. Pattern Recognit., Istanbul, Turkey, IEEE, 2010, pp. 3599–3602. doi: 10.1109/ICPR.2010.878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. L. M. Wastupranata, S. G. Kong, and L. Wang, “Deep learning for abnormal human behavior detection in surveillance videos—A survey,” Electronics, vol. 13, no. 13, 2024, Art. no. 2579. doi: 10.3390/electronics13132579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. S. W. Khan et al., “Anomaly detection in traffic surveillance videos using deep learning,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 17, 2022, Art. no. 6563. doi: 10.3390/s22176563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. J. Gu et al., “Recent advances in convolutional neural networks,” Pattern Recognit., vol. 77, no. 11, pp. 354–377, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2017.10.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. D. Yang, Y. Wu, F. Sun, J. Chen, D. Zhai and C. Fu, “Freeway accident detection and classification based on the multi-vehicle trajectory data and deep learning model,” Transport. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol., vol. 130, 2021, Art. no. 103303. doi: 10.1016/j.trc.2021.103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. M. Bortnikov, A. Khan, A. M. Khattak, and M. Ahmad, “Accident recognition via 3D CNNs for automated traffic monitoring in smart cities,” in Advances in Computer Vision, K. Arai and S. Kapoor, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, vol. 944, pp. 256–264. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-17798-0_22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Y. Wang, X. Wei, H. Shen, L. Ding, and J. Wan, “Robust fusion for RGB-D tracking using CNN features,” Appl. Soft Comput., vol. 92, Jul. 2020, Art. no. 106302. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. T. Tamagusko, M. G. Correia, M. A. Huynh, and A. Ferreira, “Deep learning applied to road accident detection with transfer learning and synthetic images,” Transp. Res. Procedia, vol. 64, pp. 90–97, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.trpro.2022.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. M. Iman, H. R. Arabnia, and K. Rasheed, “A review of deep transfer learning and recent advancements,” Technologies, vol. 11, no. 2, 2023, Art. no. 40. doi: 10.3390/technologies11020040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. S. R. Waheed, N. M. Suaib, M. S. M. Rahim, A. R. Khan, S. A. Bahaj and T. Saba, “Synergistic integration of transfer learning and deep learning for enhanced object detection in digital images,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 13525–13536, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3354706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. D. Zhang, X. Yu, L. Yang, D. Quan, H. Mi and K. Yan, “Data-augmented deep learning models for abnormal road manhole cover detection,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 5, 2023, Art. no. 2676. doi: 10.3390/s23052676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. B. Kiran, D. Thomas, and R. Parakkal, “An overview of deep learning based methods for unsupervised and semi-supervised anomaly detection in videos,” J. Imaging., vol. 4, no. 2, 2018, Art. no. 36. doi: 10.3390/jimaging4020036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chughtai, B. Riaz, and A. Jalal, “Traffic surveillance system: Robust multiclass vehicle detection and classification,” in 2024 5th Int. Conf. Adv. Computat. Sci. (ICACS), IEEE, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ICACS60934.2024.10473304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. V. Chandola, A. Banerjee, and V. Kumar, “Anomaly detection: A survey,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 1–58, 2009. doi: 10.1145/1541880.1541882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. S. Zhou, W. Shen, D. Zeng, M. Fang, Y. Wei and Z. Zhang, “Spatial-temporal convolutional neural networks for anomaly detection and localization in crowded scenes,” Signal Process.: Image Commun., vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 358–368, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.image.2016.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. H. Kim, S. Park, and J. Paik, “Pre-activated 3D CNN and feature pyramid network for traffic accident detection,” in 2020 IEEE Int. Conf. Consum. Electr. (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–3. doi: 10.1109/ICCE46568.2020.9043125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. E. Selvi et al., “Suspicious actions detection system using enhanced CNN and surveillance video,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 24, 2022, Art. no. 4210. doi: 10.3390/electronics11244210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. D. Tian, C. Zhang, X. Duan, and X. Wang, “An automatic car accident detection method based on cooperative vehicle infrastructure systems,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 127453–127463, 2019. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2939532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. C. N. Phyo, T. T. Zin, and P. Tin, “Deep learning for recognizing human activities using motions of skeletal joints,” IEEE Trans. Consumer Electron., vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 243–252, 2019. doi: 10.1109/TCE.2019.2908986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. F. U. M. Ullah et al., “An intelligent system for complex violence pattern analysis and detection,” Int. J. Intelligent Sys., vol. 37, no. 12, pp. 10400–10422, 2022. doi: 10.1002/int.22537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. M. S. Pillai, G. Chaudhary, M. Khari, and R. G. Crespo, “Real-time image enhancement for an automatic automobile accident detection through CCTV using deep learning,” Soft Comput., vol. 25, no. 18, pp. 11929–11940, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00500-021-05576-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. H. Tutar, A. Güneş, M. Zontul, and Z. Aslan, “A hybrid approach to improve the video anomaly detection performance of pixel- and frame-based techniques using machine learning algorithms,” Computation, vol. 12, no. 2, 2024, Art. no. 19. doi: 10.3390/computation12020019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. D. Berardini, L. Migliorelli, A. Galdelli, E. Frontoni, A. Mancini and S. Moccia, “A deep-learning framework running on edge devices for handgun and knife detection from indoor video-surveillance cameras,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 83, no. 7, pp. 19109–19127, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s11042-023-16231-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. N. Hnoohom, P. Chotivatunyu, and A. Jitpattanakul, “ACF: An armed CCTV footage dataset for enhancing weapon detection,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 19, 2022, Art. no. 7158. doi: 10.3390/s22197158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. M. Sabuhi, M. Zhou, C. -P. Bezemer, and P. Musilek, “Applications of generative adversarial networks in anomaly detection: A systematic literature review,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 161003–161029, 2021. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3131949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. T. H. Vu, J. Boonaert, S. Ambellouis, and A. Taleb-Ahmed, “Multi-channel generative framework and supervised learning for anomaly detection in surveillance videos,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 9, 2021, Art. no. 3179. doi: 10.3390/s21093179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. R. Singh, K. Saini, A. Sethi, A. Tiwari, S. Saurav and S. Singh, “STemGAN: Spatio-temporal generative adversarial network for video anomaly detection,” Appl. Intell., vol. 53, no. 23, pp. 28133–28152, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s10489-023-04940-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. N. -T. Tran, V. -H. Tran, N. -B. Nguyen, T. -K. Nguyen, and N. -M. Cheung, “On data augmentation for gan training,” IEEE Trans. Image Process., vol. 30, pp. 1882–1897, 2021. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2021.3049346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. P. Isola, J. -Y. Zhu, T. Zhou, and A. A. Efros, “Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., 2017, pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

36. J. Yu, Y. Lee, K. C. Yow, M. Jeon, and W. Pedrycz, “Abnormal event detection and localization via adversarial event prediction,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 3572–3586, 2022. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3053563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. W. Liu, W. Luo, D. Lian, and S. Gao, “Future frame prediction for anomaly detection-a new baseline,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., 2018, pp. 6536–6545. [Google Scholar]

38. N. Gandhi, “Stacked ensemble learning based approach for anomaly detection in IoT environment,” in 2021 2nd Int. Conf. Range Technol. (ICORT), IEEE, 2021. doi: 10.1109/ICORT52730.2021.9581549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. M. Bansal, M. Kumar, M. Sachdeva, and A. Mittal, “Transfer learning for image classification using VGG19: Caltech-101 image data set,” J. Ambient Intell. Human Comput., vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 3609–3620, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s12652-021-03488-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. G. Haralabopoulos, I. Anagnostopoulos, and D. McAuley, “Ensemble deep learning for multilabel binary classification of user-generated content,” Algorithms, vol. 13, no. 4, 2020, Art. no. 83. doi: 10.3390/a13040083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. J. Zhou, F. Chen, A. Khattak, and S. Dong, “Interpretable ensemble-imbalance learning strategy on dealing with imbalanced vehicle-bicycle crash data: A case study of Ningbo, China,” Int. J. Crashworthiness, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 1–14, 2024. doi: 10.1080/13588265.2024.2316924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. E. Tasci, C. Uluturk, and A. Ugur, “A voting-based ensemble deep learning method focusing on image augmentation and preprocessing variations for tuberculosis detection,” Neural Comput. Applic., vol. 33, no. 22, pp. 15541–15555, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00521-021-06177-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. A. Mohammed and R. Kora, “A comprehensive review on ensemble deep learning: Opportunities and challenges,” J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci., vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 757–774, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. P. Smyth and D. Wolpert, “Stacked density estimation,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, M. Jordan, M. Kearns, and S. Solla, Eds. USA: MIT Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

45. T. M. Hospedales, A. Antoniou, P. Micaelli, and A. J. Storkey, “Meta-learning in neural networks: A survey,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., vol. 44, no. 9, pp. 5149–5169, 2022. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3079209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. S. Natha, “Road anomaly dataset,” 2024. doi: 10.34740/kaggle/dsv/9204726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. M. Ramzan, A. Abid, M. Bilal, K. M. Aamir, S. A. Memon and T. -S. Chung, “Effectiveness of pre-trained CNN networks for detecting abnormal activities in online exams,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 21503–21519, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3359689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. M. Mukto et al., “Design of a real-time crime monitoring system using deep learning techniques,” Intell. Syst. Appl., vol. 21, 2024, Art. no. 200311. doi: 10.1016/j.iswa.2023.200311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. K. Avazov, M. K. Jamil, B. Muminov, A. B. Abdusalomov, and Y. -I. Cho, “Fire detection and notification method in ship areas using deep learning and computer vision approaches,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 16, 2023, Art. no. 7078. doi: 10.3390/s23167078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. M. Megnidio-Tchoukouegno and J. A. Adedeji, “Machine learning for road traffic accident improvement and environmental resource management in the transportation sector,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 3, 2023, Art. no. 2014. doi: 10.3390/su15032014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. R. Vijeikis, V. Raudonis, and G. Dervinis, “Efficient violence detection in surveillance,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 6, 2022, Art. no. 2216. doi: 10.3390/s22062216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Y. Li, N. Miao, L. Ma, F. Shuang, and X. Huang, “Transformer for object detection: Review and benchmark,” Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell., vol. 126, 2023, Art. no. 107021. doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools