Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Uncovering Causal Relationships for Debiased Repost Prediction Using Deep Generative Models

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Southeast University, Nanjing, 211189, China

2 Department of Media and Communication, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, 999077, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiao Fan Liu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 4551-4573. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.057714

Received 26 August 2024; Accepted 14 November 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

Microblogging platforms like X (formerly Twitter) and Sina Weibo have become key channels for spreading information online. Accurately predicting information spread, such as users’ reposting activities, is essential for applications including content recommendation and analyzing public sentiment. Current advanced models rely on deep representation learning to extract features from various inputs, such as users’ social connections and repost history, to forecast reposting behavior. Nonetheless, these models frequently ignore intrinsic confounding factors, which may cause the models to capture spurious relationships, ultimately impacting prediction performance. To address this limitation, we propose a novel Debiased Reposting Prediction model (DRP). Our model mitigates the influence of confounding variables by incorporating intervention operations from causal inference, enabling it to learn the causal associations between features and user reposting behavior. Specifically, we introduce a memory network within DRP to enhance the model’s perception of confounder distributions. This network aggregates and learns confounding information dispersed across different training data batches by optimizing the reconstruction loss. Furthermore, recognizing the challenge of acquiring prior knowledge of causal graphs, which is crucial for causal inference, we develop a causal discovery module within DRP (CD-DRP). This module allows the model to autonomously uncover the causal graph of feature variables by analyzing microblogging data. Experimental results on multiple real-world datasets demonstrate that our proposed method effectively uncovers causal relationships between variables, exhibits strong time efficiency, and outperforms state-of-the-art models in prediction performance (improved by 2.54%) and overfitting reduction (by 7.44%).Keywords

Microblogging platforms enable users to post and share content on their timelines, with ‘reposting’ functioning as a core mechanism for spreading information online [1]. Accurately predicting repost behavior is therefore valuable across several applications. For instance, advertising and marketing agencies rely on repost prediction to gauge the potential reach of campaigns among target audiences [2,3]; meanwhile, microblogging services utilize repost likelihood predictions to optimize content recommendations and improve user retention [4]. Recent repost prediction models employ deep learning techniques to extract features from microblogging data, including contents and social relationships, and utilize these features to predict users’ repost behaviors based on their associations [5–7].

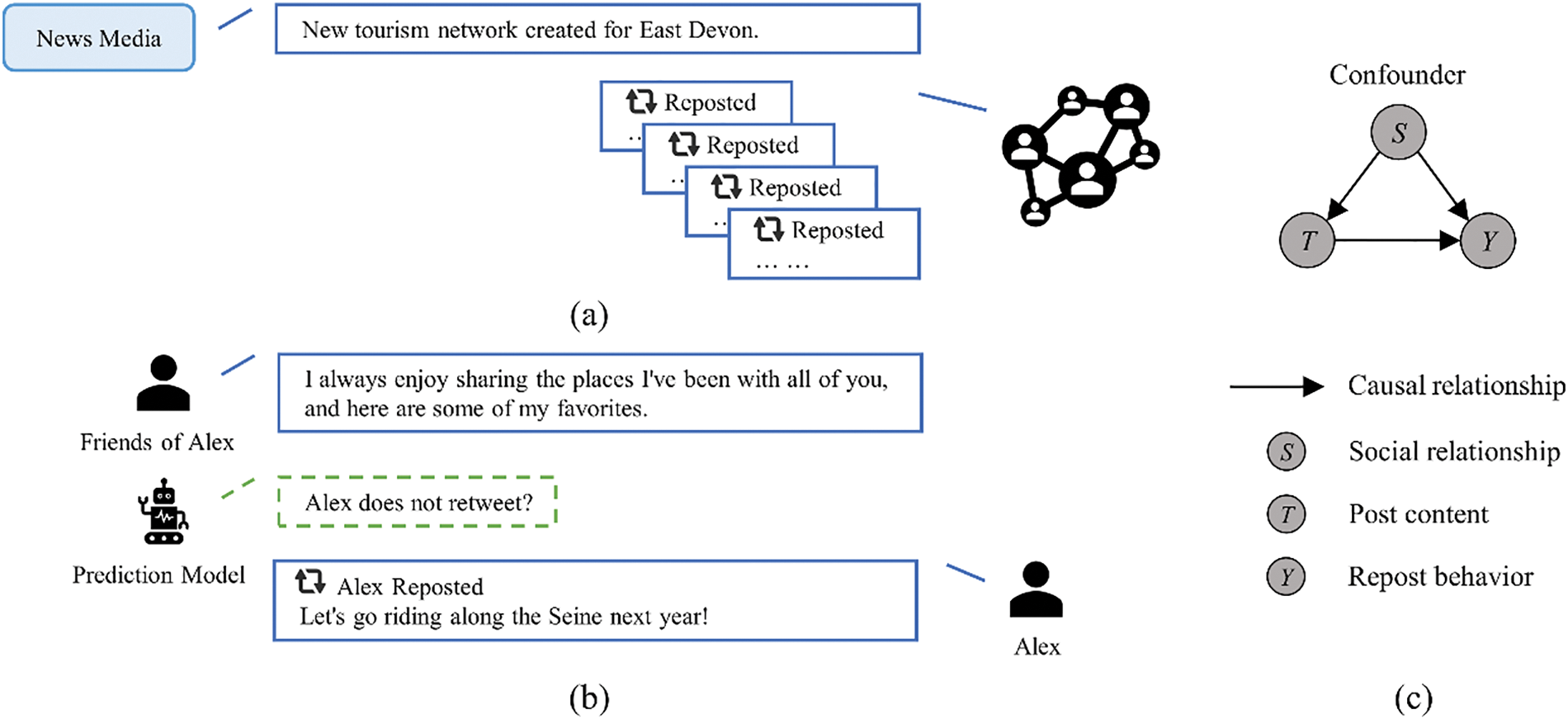

However, these models often fail to account for confounding variables, which may lead to the learning of spurious associations in the training data, ultimately hindering generalization. For example, as shown in Fig. 1a, news media accounts with large follower bases exert significant social influence, making their content more likely to be reposted by users (social relationship → user behavior) [8]. As a result, once trained, a model may erroneously assume that content from these influential users automatically aligns with the interests of other users. This can lead to inaccurate predictions when the model encounters posts from less influential users (see Fig. 1b). This phenomenon is illustrated in Fig. 1c. Assume

Figure 1: An example of the repost scenario

To address the challenge of confounding variables, recent research has combined deep learning models with causal inference methods. For instance, image recognition models [11–13] utilize causal inference techniques to mitigate the effects of confounders like text and image context. Similarly, recommendation algorithms [14–16] use causal inference to mitigate bias resulting from item popularity. In this context, repost prediction models can leverage causal inference to estimate the causal association between features and user behavior, enabling them to better understand the data and achieve Debiased Repost Prediction (DRP). However, this task poses several challenges from different perspectives. Firstly, identifying confounding variables necessitates the model to possess complete prior knowledge of the variable causality, which may be difficult to achieve in real-world scenarios. Secondly, controlling for the influence of confounding variables requires the model to be aware of the distribution of these variables. In the absence of identifying confounding variables, it is difficult to manually define a confounder dictionary to represent their distribution. We will formally formulate these challenges in Section 3.2.

To address the above challenges, this paper proposes a novel debiased repost prediction model, namely, Causal Discovery for Debiased Repost Prediction (CD-DRP). The proposed method enables the DRP model without assuming a causal relationship. Specifically, the CD-DRP model devises a deep generative network that includes a parameter matrix and several parallel multilayer perceptrons (MLPs). The parameter matrix is the adjacency matrix of the causal graph, which reflects the variable dependencies, while the MLPs are responsible for generating conditional probability distributions between variables. This network aims to identify a causal graph that maximizes the likelihood of microblogging data. This generative network ensures that the proposed model can identify the most explanatory causal graph for the microblogging service. Meanwhile, to facilitate learning the distribution of confounding variables, the CD-DRP model designs a confounder memory network to adeptly capture the information pertaining to these variables within individual data batches. This network can retrieve its memory for various data batches efficiently and works towards minimizing the disparity between the stored memory and the observed confounding variables throughout the training process.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• The CD-DRP model is the first DRP model that enables both causal discovery and debiased repost prediction. It can control the impact of confounders and enhance model generalizability without prior knowledge of the causal graph.

• The CD-DRP model proposes a deep generative network for inferring causal relationships. This network can discover the causal graph that reveals the generation mechanism underlying microblogging data.

• To perceive the distribution of confounding variables, the CD-DRP model designs a confounder memory network. This network can gradually absorb the information of confounders scattered in different data batches by optimizing the reconstruction loss.

• Experimental results on real-world datasets demonstrate that the CD-DRP model effectively captures the causal relationships among variables in the reposting prediction scenario and outperforms state-of-the-art models in predictive performance.

The rest of the paper is arranged as below: Section 2 reviews the related research on causal deep learning and repost prediction. Section 3 provides the necessary background information. Section 4 introduces the CD-DRP model. Section 5 outlines the experimental setup and offers a multi-faceted analysis of experiments, including generalizability, causal graph evaluation, ablation studies, hyperparameter sensitivity, and model efficiency. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

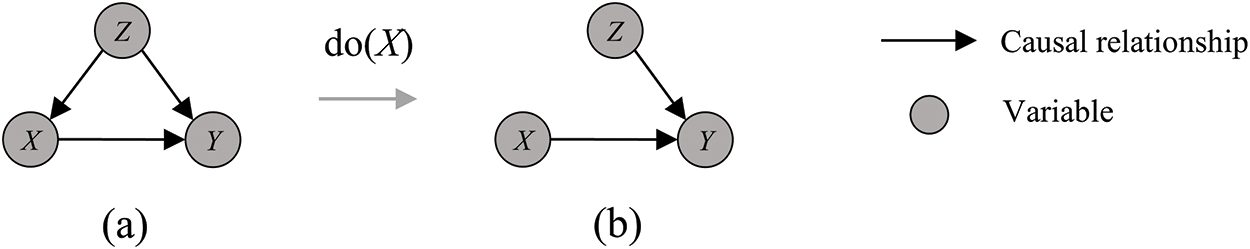

Deep learning is widely used in areas such as image recognition, natural language processing, and recommendation systems with its powerful learning and representation capabilities [17,18]. However, its susceptibility to learn spurious relations affected by confounding variables has been plaguing researchers in the field of deep learning [19]. Since causal inference [20] can control the impact of confounders and evaluate the causal effect of feature variables on predicted targets by do-calculus, i.e.,

Predicting reposts plays a key role in opinion analysis and recommendation systems [4,21]. The majority of repost prediction methods concentrate on using machine learning models to identify and learn relevant features. For instance, Jiang et al. [22] extended the probabilistic matrix factorization method by introducing two additional matrices: a social influence matrix based on social network structure and interaction history, and a message similarity matrix based on document semantics. By optimizing the latent feature space of users and messages, the model separately learns social influence and message semantic features, thereby enhancing its predictive performance on user reposting behavior. Safari et al. [23] designed a V-DBNC model based on a dynamic Bayesian network, which can predict users’ reposting behavior by learning user behavior patterns, reposting path structure, and social influence between users. In recent years, the development of deep learning technology has highlighted the significant advantages of neural networks over traditional machine learning methods in feature representation. Consequently, neural network-based models for predicting user reposting behavior have gained increasing popularity [5,7]. For example, Wang et al. [24] proposed a dual autoencoder model to capture the features of user identity information, social relationships, and group reposting factors. The model also incorporates an attention mechanism to extract topic representations from users’ historical reposting activities, ultimately predicting their behavior by learning these multi-dimensional features. Literature [25] introduced the GODEN model, which combines ordinary differential equations with graph neural networks to capture both dynamic user interactions and static user relationships. The model represents the reposting propagation pattern through user and time context, employing a multi-head attention module to focus on various contextual information and predict the next user likely to forward the content.

Existing repost prediction models often neglect confounding variables, which can result in capturing spurious associations between feature variables and user behavior. This limitation hampers the generalization ability of these models. To address this issue and achieve Debiased Repost Prediction (DRP), it is essential to combine repost prediction models with causal inference techniques. However, causal inference typically relies on prior knowledge of the causal relationships, which is challenging to obtain in the context of real-world applications like repost prediction. Correspondingly, due to the lack of prior knowledge of causality, we cannot predefine a confounding variable dictionary [11,13,26] to help the DRP model learn causal associations. Therefore, in this paper, we aim to empower the DRP model to discover variable causality and to learn causal associations without predefining a confounder dictionary.

Recent causal discovery algorithms [27–29] are capable of identifying the structure of a causal Bayesian network from datasets containing

where the term

Deep learning models typically generate predictions by identifying associations between feature

the confounder

Figure 2: The diagram of do-calculus

Therefore, recent deep learning models [11,19] implement causal learning by leveraging the do-calculus to block the causal relationship between

Compared to Eq. (2),

In the context of the repost prediction, addressing the impact of confounding variables is equally crucial. Employing causal deep learning techniques enables these models to discern causal associations and enhances their generalization capabilities. However, two substantial challenges are encountered:

• To perform causal deep learning (as illustrated in Fig. 2), a model needs to initially identify the confounding variable

• As depicted in Eq. (3), when a model learns causal association, it needs to know the distribution of the confounder

4.1 Problem Formulation and Notations

The repost prediction task can be seen as a classification task [5]. Given a query post

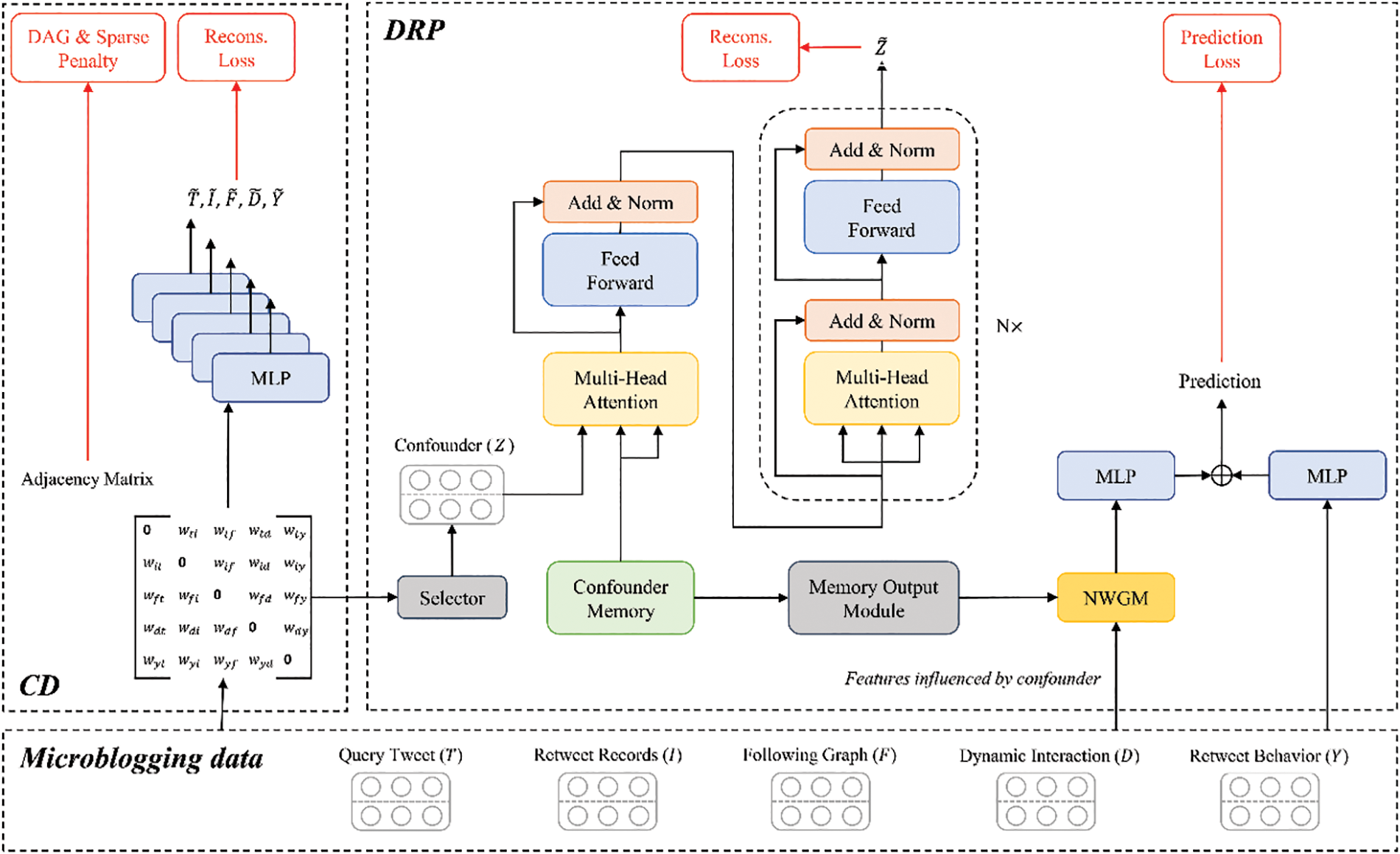

Figure 3: The framework of proposed CD-DRP

The CD-DRP model diverges fundamentally from existing causal deep learning models, such as those presented in [11,19]. Firstly, the CD-DRP model operates independently of expert knowledge on causal relationships, autonomously discovering variable causality through the observation of microblogging data. This autonomy allows the model to adeptly handle repost prediction scenarios involving multiple variables and mitigate bias stemming from expert knowledge. Secondly, in the process of learning causal associations, the CD-DRP model obviates the need for manually constructing confounder dictionaries. This characteristic provides effective support for debiased repost prediction.

To facilitate the proposed CD-DRP model to learn microblogging data, we first map

The aim of the causal discovery (CD) module is to identify the causal graph with the most explanatory power for the microblogging data and assist the debiased repost prediction module in identifying confounding variables. As variables like

the parameters in the columns of matrix

where

During training, the causal discovery module continually optimizes the parameters of both

ultimately achieves the goal of uncovering the causal relationships between variables and understanding the mechanisms that drive the generation of data. Here, RMSE is the root mean square error, which is used to measure the discrepancy between

4.4 Debiased Repost Prediction

Based on the discovered causal graph, we can identify confounders that affect the generalizability of the repost prediction model, i.e., variables that affect both predictor

However,

By setting

where

During training, the DRP module takes the cross entropy

to optimize the parameters and improve its prediction performance.

It should be noted that CD-DRP lacks prior knowledge of the causal relationships and therefore cannot identify

the information about

The reconstruction loss of

After multiple rounds of training,

To summarize, the DRP module is designed to achieve two objectives: to perceive the distribution of confounding variables and to predict user behavior. The objective for the module is denoted as

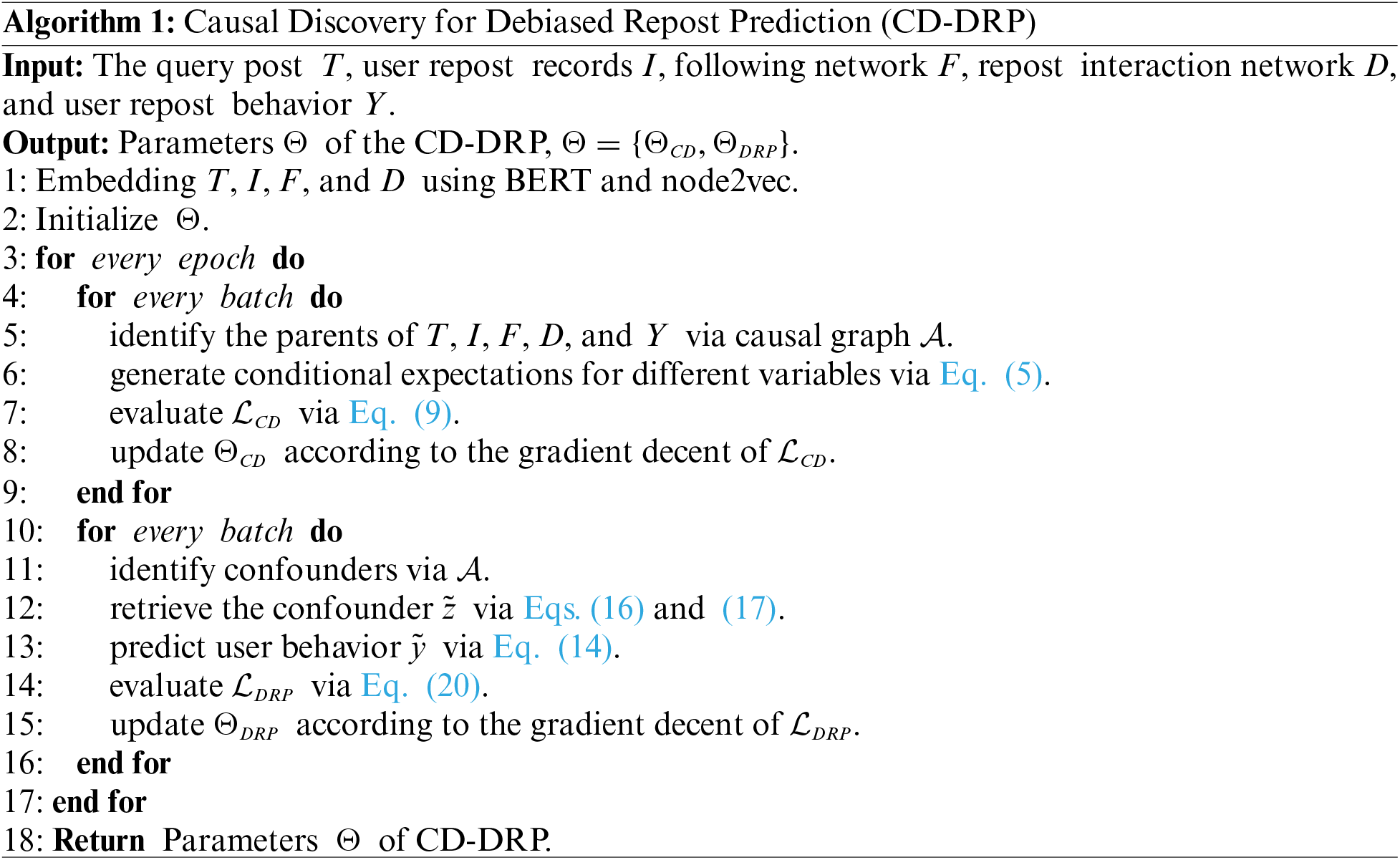

The descriptions of different modules of the proposed CD-DRP model in Sections 4.2–4.4 are summarized here as Algorithm 1. Specifically, the CD-DRP model first uses BERT [30] and node2vec [31] to map query posts

In this section, we conduct experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed model with a comparison to state-of-the-art baselines. Specifically, we aim to answer the following research questions:

• RQ1: How does the generalizability of the proposed CD-DRP model compare to the state-of-the-art baselines?

• RQ2: What causal relationships are identified by the CD-DRP model? Do these relationships align with common perceptions?

• RQ3: If CD-DRP model performs well, what component benefits CD-DRP model in the repost prediction task?

• RQ4: What is the influence of different hyperparameter settings on the performance of CD-DRP model?

• RQ5: Compared to baselines, what is the time efficiency of CD-DRP model?

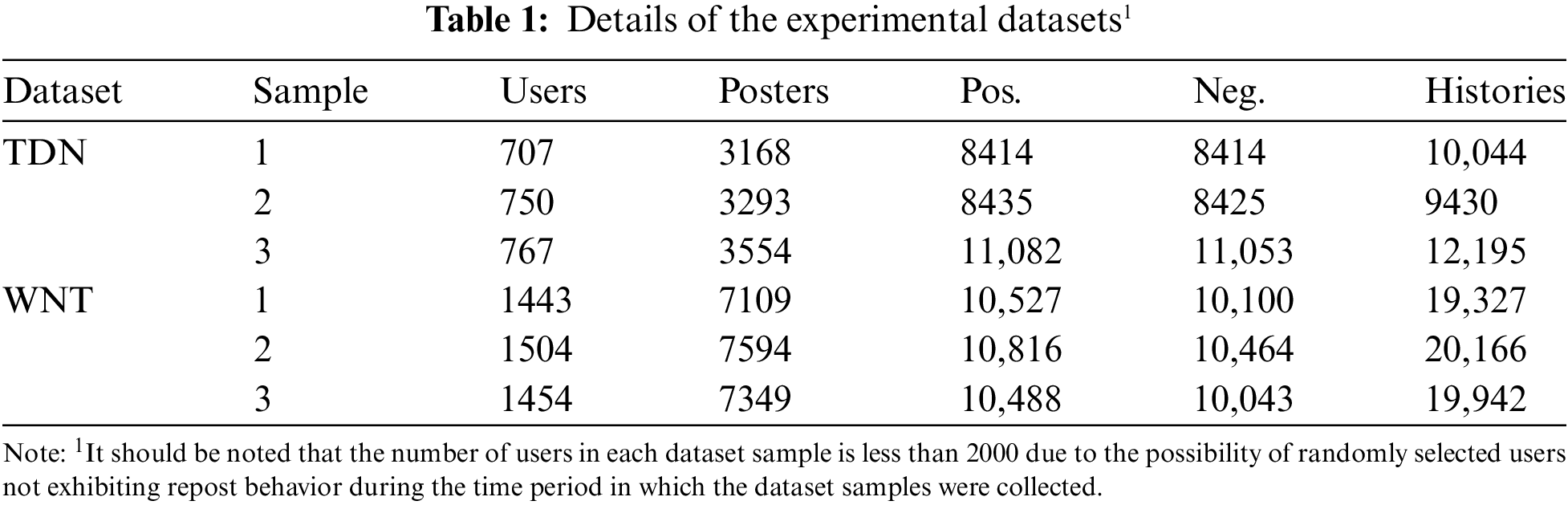

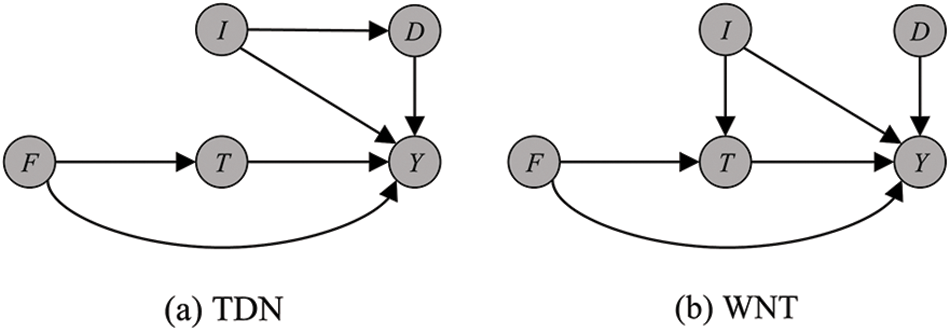

Datasets The proposed CD-DRP model is assessed through experiments using the Twitter-Dynamic-Net (TDN)1 and Weibo-Net-Tweet (WNT)2 datasets. To ensure result reliability, we draw three samples from each dataset for evaluation. The sampling procedure follows these steps: First, for both TDN and WNT, we randomly select 2000 users and gather their follower lists. Next, the repost records

Baselines We conduct a comparative analysis of the proposed method against various baseline models, encompassing random models, those with simple structures (such as LR, SUA-ACNN [34], GraphSAGE [35], and DynamicGCN [36]), and those with complex structures (including AMNL [37], DFMF [38], GFCI [39], and GCRec [15]):

• Random: The prediction of reposting behavior, whether it occurs or not, is randomly determined in this model, which establishes the distribution of positive and negative instances and serves as the baseline. Any model capable of learning from data to predict reposting behavior is expected to outperform this Random model.

• LR: A simple classification model. It predicts user behavior based on BERT features of the query post and repost records.

• SUA-ACNN: An attention-based convolutional neural network. This method uses convolutional neural networks to capture features of posts and learns user interests with attention mechanisms. By evaluating the similarity between query posts and users’ interests, SUA-ACNN makes predictions about users’ behavior.

• GraphSAGE: A graph convolutional network. It learns the topological information of following network with graph convolution and uses it to represent the social relationship features of users. The social relationship features are the basis for prediction.

• DynamicGCN: A dynamic graph neural network, which uses graph convolutional networks and recurrent neural networks to capture the features of temporal repost interactions. DynamicGCN predicts user behavior based on their past repost interactions.

• AMNL: This model constructs a heterogeneous network consisting of following relationships, repost interactions, and posts. It learns the joint post representations and user preference representations from this heterogeneous network for repost prediction.

• DFMF: This model uses deep representation learning methods to capture the following network and post features. Based on these multimodal features, it employs a fully-connected forward neural network to predict user behavior.

• GFCI: This model utilizes the bidirectional attention mechanism to capture user interest from past reposts and learns the features of repost interactions through a dynamic graph convolutional network. It makes the prediction through a multimodal fusion layer.

• GCRec: A causal-based reposting prediction model, which first utilizes graph neural networks to capture the information of the social and reposting interaction networks, representing the features of users and posts. Subsequently, do-calculus (see Section 3.2) is applied to control for the influence of confounding variables, enabling the prediction of reposting behavior based on users’ preferences. The variable causal diagram is identified by our CD-DRP model.

Metrics The experiments use the popular Accuracy (

where

We implement the proposed model and all baseline models (excluding LR) using PyTorch, while LR is implemented with scikit-learn’s built-in function. The pretrained BERT parameters are obtained from the links provided in the footnotes3,4. Both BERT and node2vec use an embedding dimension of 768, and the memory network size for CD-DRP is set to

Generalizability is important for repost prediction models because the goal of these models is to be able to accurately predict users’ repost behavior for new, unseen posts. A model with poor generalizability may suffer from overfitting problems, i.e., it performs well on training data but fails to make accurate predictions on testing data. Therefore, we analyze the generalizability of the proposed CD-DRP model and baselines in terms of both prediction performance and overfitting degree.

Prediction Comparison Table 2 records the prediction performance of the proposed CD-DRP model and baselines on the testing set of six sample datasets. From Table 2, we can find that:

• Each of the simple baseline methods demonstrates superior performance compared to the Random model. This observation indicates that the inclusion of the query post, user repost records, following networks, and repost interactions as features is advantageous for predicting user behavior. Notably, GraphSAGE and DynamicGCN exhibit comparable performance, with a marginal difference in average test Accuracy of less than 0.7%. Moreover, both GraphSAGE and DynamicGCN outperform LR and SUA-ACNN in the majority of cases.

• The complex structural models exhibit a significant improvement over the simple structural models across multiple dataset samples. For instance, DFMF surpasses DynamicGCN in different dataset samples, resulting in an average improvement of 4.07% in test Accuracy and 2.46% in F1-score. Among the complex structural models, the causal-based GCRec model outperforms the others, while the remaining models show comparable performance. Specifically, the GCRec model achieves an average F1-score that is approximately 3.7% higher than that of the GFCI model across all datasets. In contrast, the GFCI model’s performance is close to that of the AMNL and DFMF models, with an average F1-score difference of less than 2%. These results underscore the importance of controlling for confounding variables and predicting user reposting behavior based on causal associations. Since these models learn similar information—such as query posts, user reposting histories, following relationships, and reposting interaction networks—the GCRec model demonstrates superior ability to capture user reposting preferences.

• The prediction performance of the proposed CD-DRP model outperforms all baselines. For the state-of-the-art baseline GCRec, CD-DRP improves both Accuracy and F1-score metrics by about 2.90% and 2.54%. This result confirms the CD-DRP model’s ability to control for confounding variables and enhance reposting prediction performance. Additionally, by discovering causal relationships through the analysis of online social network data, the CD-DRP model demonstrates greater practical value compared to other causal-based reposting prediction models.

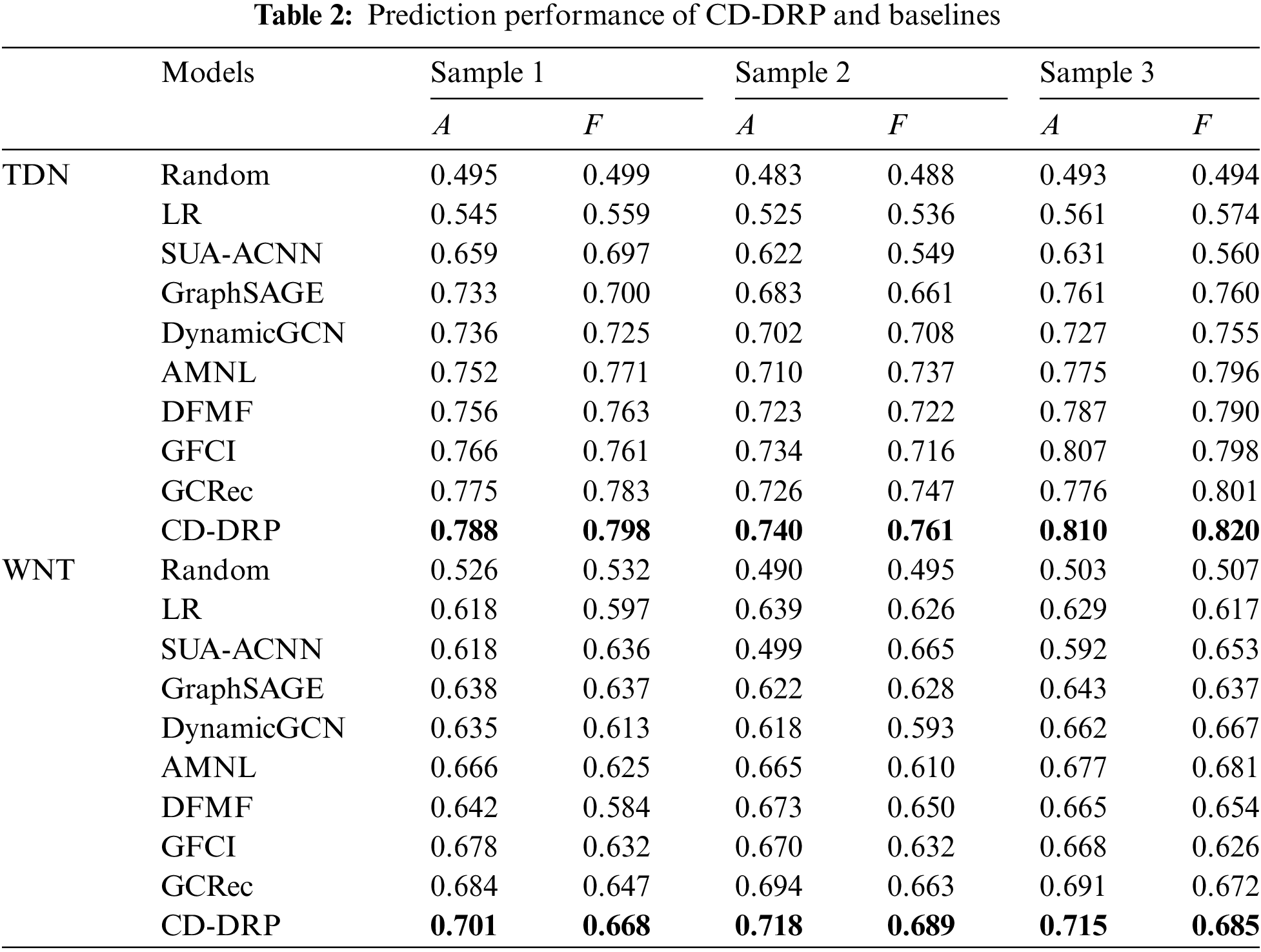

Overfitting Comparison As described in Section 5.2, we utilize the F1-score as an early stopping metric during training and assess the model’s repost prediction ability on the training set. To evaluate the degree of overfitting, we examine the difference, denoted as

In this study, we compare the degree of overfitting of the proposed CD-DRP model and the 4 best baselines in terms of prediction performance (shown in Fig. 4). As can be seen from Fig. 4, these models have an F1-score distributed between 0.96 and 1.00 at the end of the training. They all fit the training data well. When combined with their F1-score on the testing set recorded in Table 2, we can see that CD-DRP model has the smallest

Figure 4: The F1-score of CD-DRP model and comparison models on the training set as the training progresses.

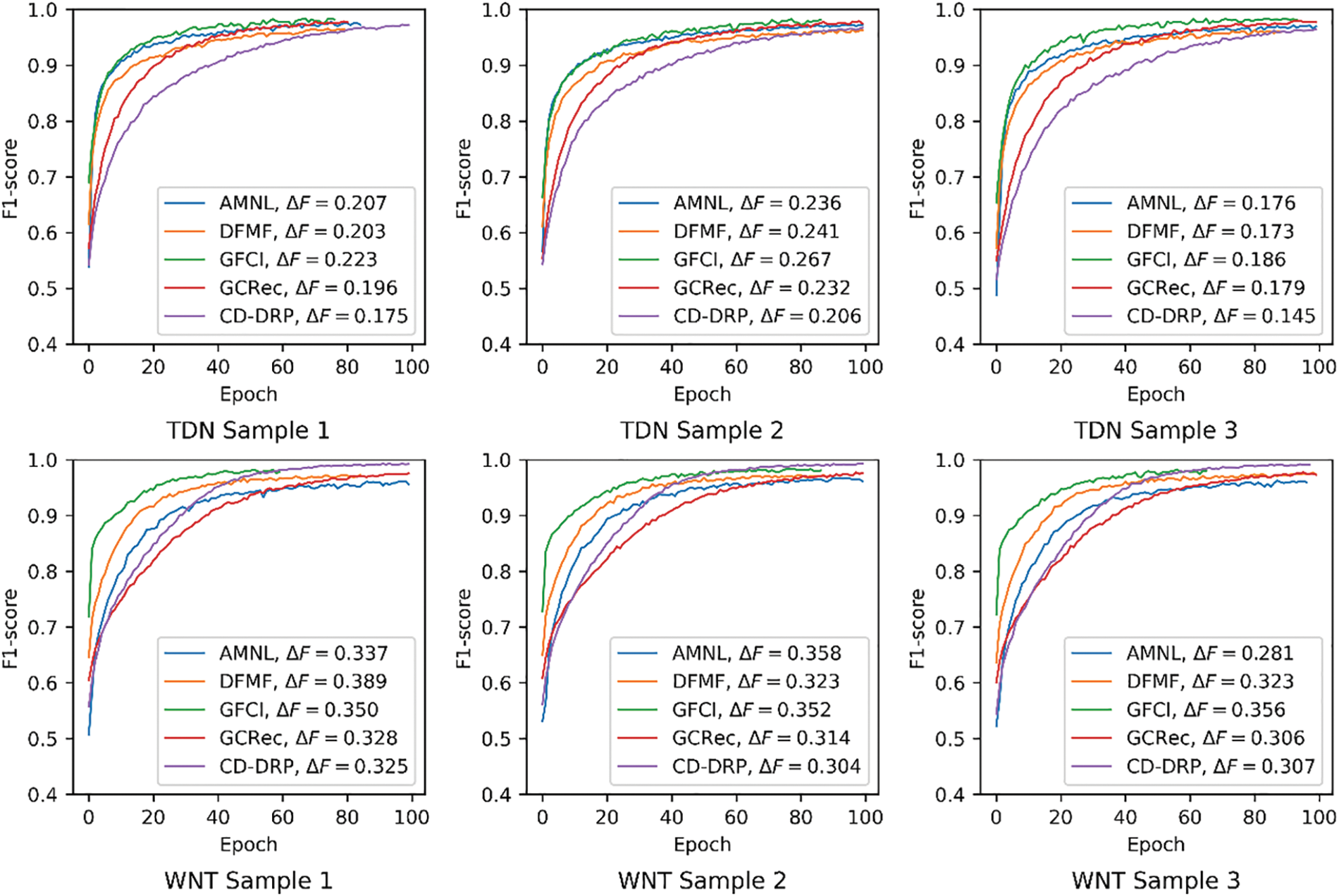

This section presents the causal graphs identified by CD-DRP model in Fig. 5. It can be observed that query posts

Figure 5: The identified causal graphs for repost prediction scenarios

To validate the causal relationships that exhibit differences between the TDN and WNT datasets, this section further conducts a causal analysis of these variations. We employ the method adopted by [43,44] to validate the causal relationships

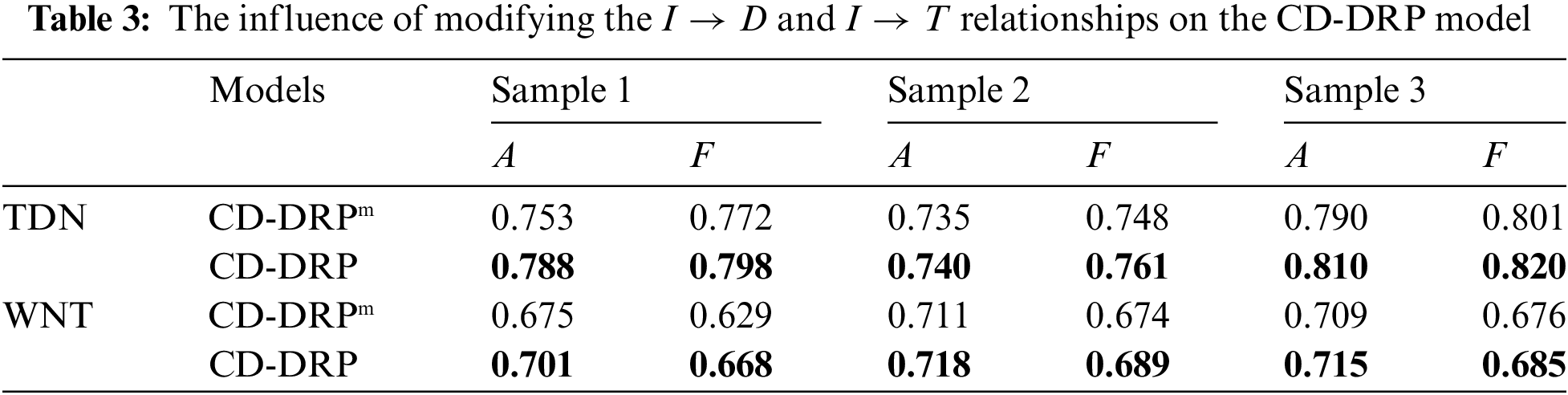

As detailed in Section 1, our primary objective is to safeguard the repost prediction model from being influenced by confounding factors, which could otherwise result in the learning of spurious relationships between features and user repost behaviors. To achieve this, we introduce causal discovery and inference methods into the repost prediction model, referred to as CD-DRP. The CD-DRP model comprises two key modules: a causal discovery module responsible for identifying causal relationships among variables, and a prediction module designed to mitigate the impact of confounding variables. Additionally, we incorporate a confounder memory network to enhance CD-DRP’s ability to perceive the distribution of confounders.

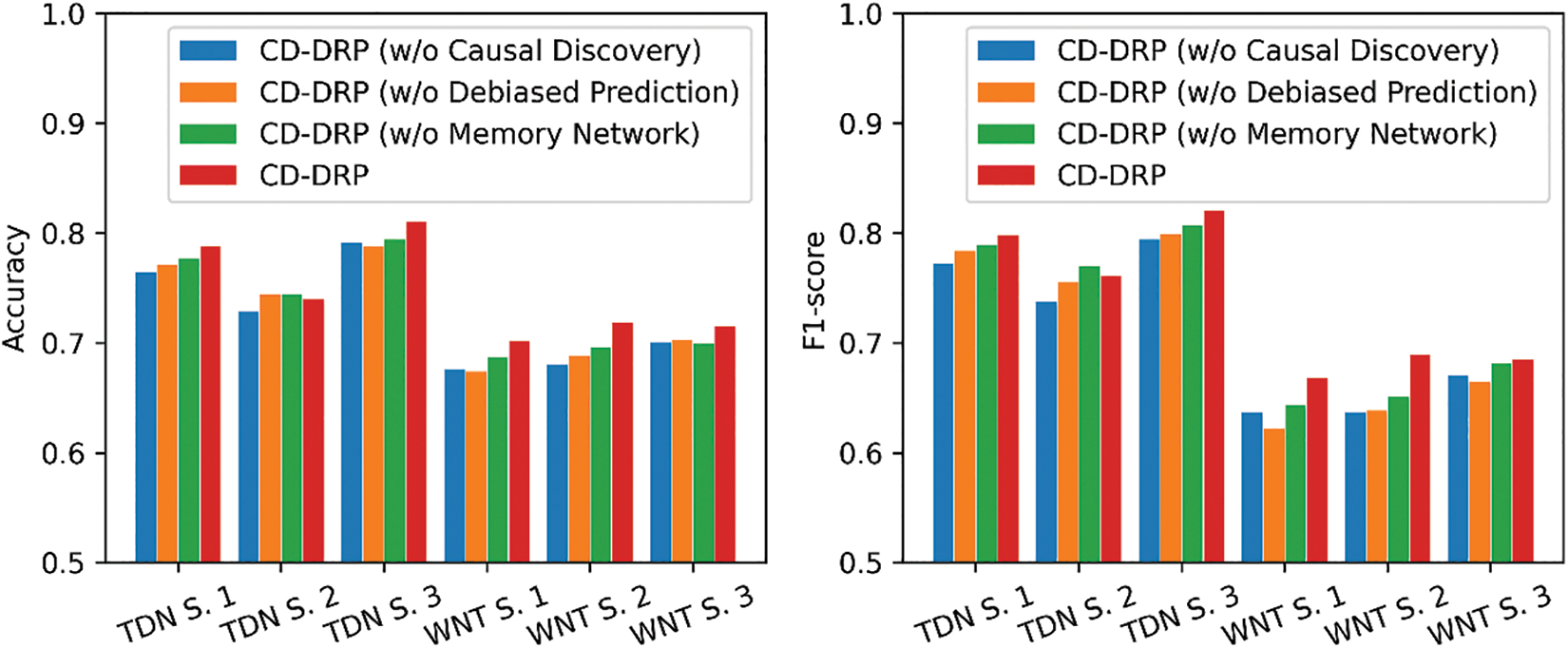

In this study, we investigate the effects of these modules on the performance of CD-DRP model through an ablation study. Firstly, we randomly disrupt the causal relationships identified by the causal discovery module and employ the disrupted relationships to guide the prediction module in generating debiased repost predictions. This variant is denoted as CD-DRP (w/o Causal Discovery). Secondly, we omit the randomization of the causal discovery module’s output, but refrain from making debiased predictions. Instead, we directly input different features into Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) for prediction. This model is labeled as CD-DRP (w/o Debiased Prediction). Lastly, we eliminate the confounder memory network and simply employ the mean of the pretrained features of confounders for debiased repost prediction. This variant is referred to as CD-DRP (w/o Memory Network).

The outcomes of the ablation study are presented in Fig. 6. From the results, it becomes evident that CD-DRP (w/o Causal Discovery) exhibits the poorest prediction performance. In terms of F1-score, it performs 4.04% lower than CD-DRP and even 0.28% lower than CD-DRP (w/o Debiased Prediction), which does not account for the impact of confounding variables. These findings highlight the crucial role of the causal relationships identified by the causal discovery module in guiding the prediction module to identify confounding variables and improve the generalization ability of CD-DRP model. Furthermore, by comparing the performance of CD-DRP (w/o Debiased Prediction) and CD-DRP, it becomes evident that controlling the impact of confounding variables is essential for CD-DRP. Without such control, the F1-score of CD-DRP experiences an average decrease of 3.74% across the six datasets examined. Lastly, upon removing the confounder memory network, the Accuracy and F1-score of CD-DRP demonstrate varying degrees of reduction across different datasets, with the exception of TDN Sample 2. On average, CD-DRP (w/o Memory Network) exhibits 1.69% lower Accuracy and 1.90% lower F1-score compared to CD-DRP model. These findings emphasize the significance of the confounder memory network in assisting CD-DRP model in better perceiving the distribution of confounding variables.

Figure 6: Performance comparison of different variants of the proposed CD-DRP

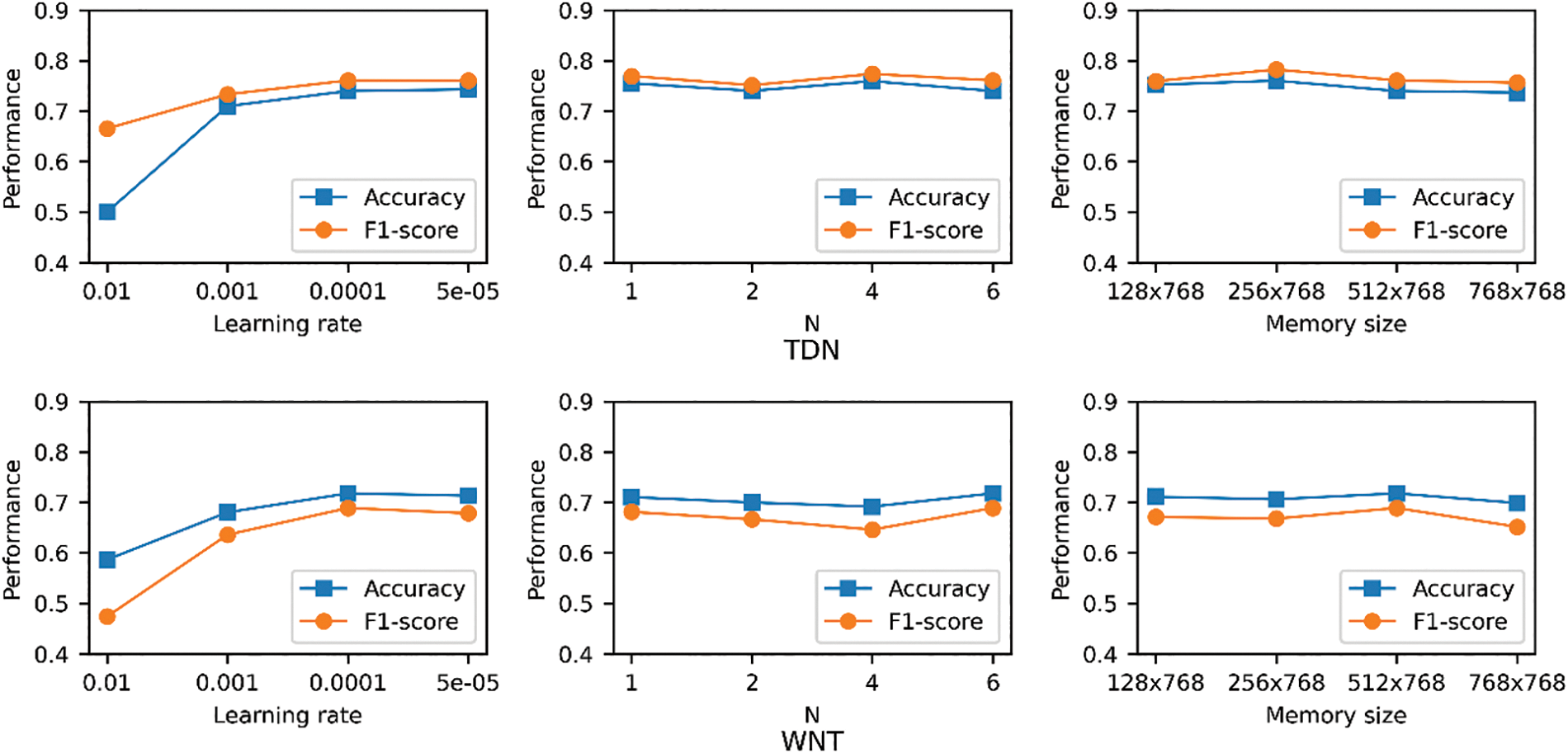

5.6 Hyperparameter Sensitivity (RQ4)

The CD-DRP model contains some unlearnable hyperparameters. We choose the following aspects to analyze the influence of hyperparameter settings on its prediction performance: (1) the learning rate, (2) the number

Figure 7: Prediction performance of CD-DRP under different hyperparameter settings

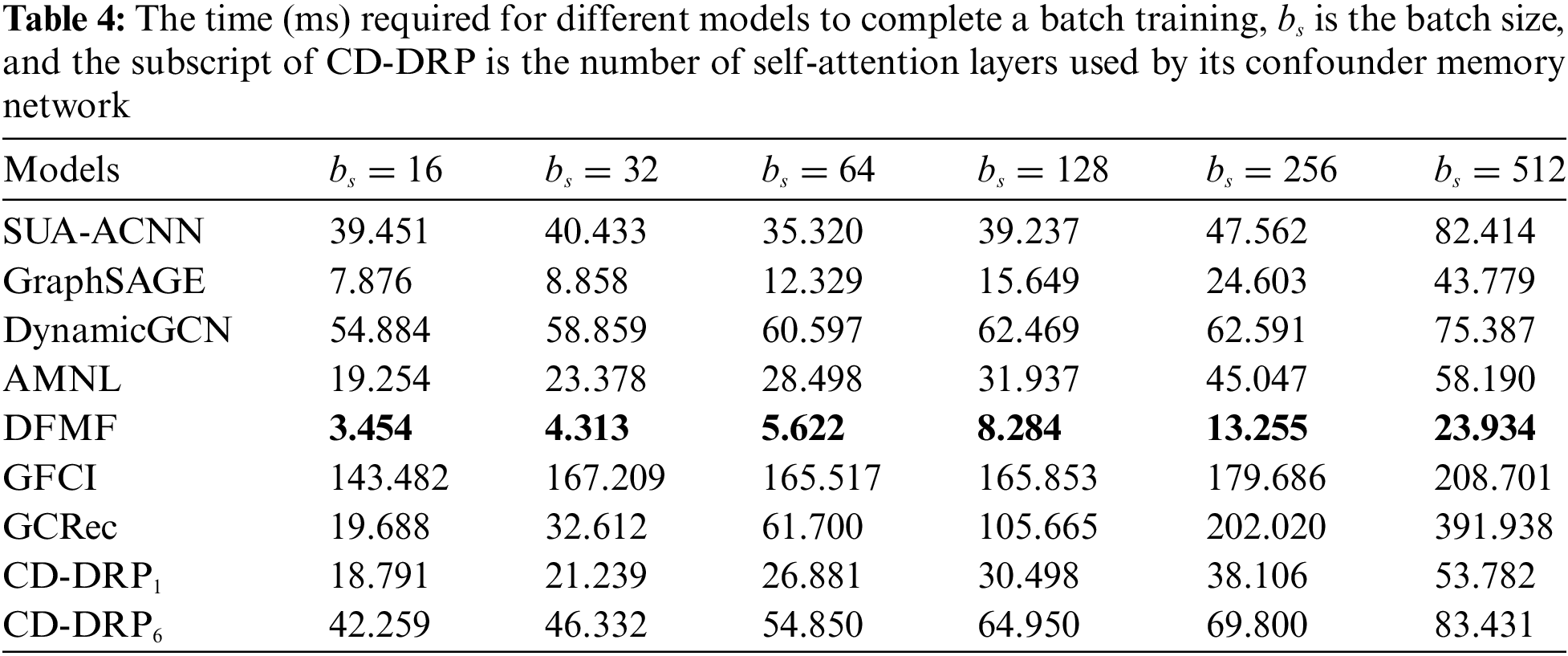

The experiments also analyze the time efficiency of different models to provide a basis for comparison and selection for practical applications. Specifically, we test the time it takes for different models to complete a batch training on TDN Sample 2 (as shown in Table 4). Based on the records in Table 4, it can be seen that DFMF has the best time efficiency, followed by GraphSAGE, and CD-DRP1 and AMNL are close to and at a good level. Therefore, combined with their prediction performance (see Table 2), we can give preference to DFMF in application scenarios that require high time efficiency. In the scenario that needs to balance time efficiency and prediction power, we can choose the CD-DRP with a simplified structure (reduce the number of self-attention layers), such as CD-DRP1.

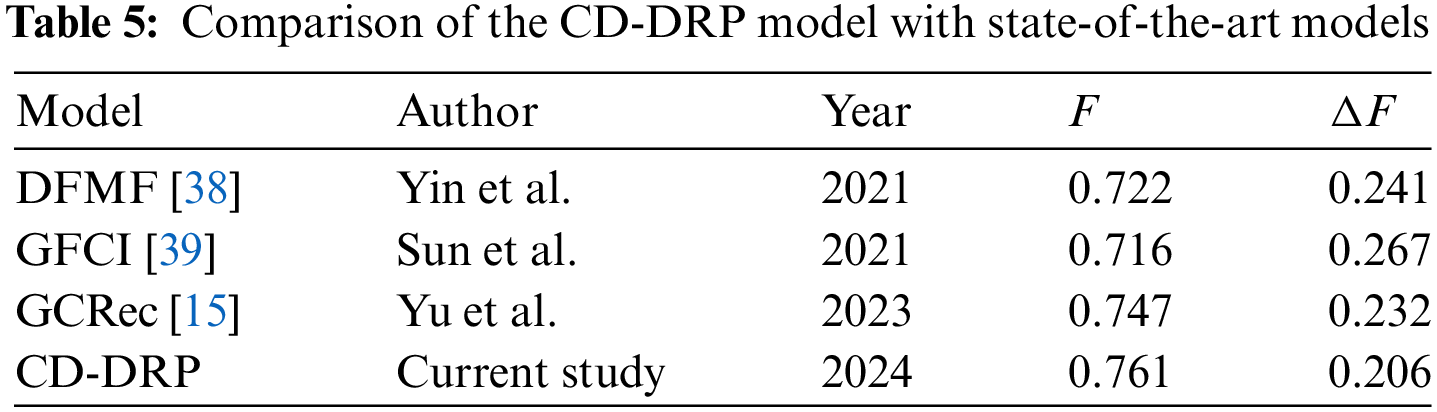

The above multi-dimensional quantitative analysis confirms that the CD-DRP model proposed in this paper demonstrates strong predictive performance and reduced overfitting. For instance, on the TDN sample dataset 2 (see Table 5), the CD-DRP model achieves a 1.87% improvement over the top-performing baseline, GCRec. Additionally, in terms of overfitting (measured by the F1-score difference between the end of training and testing), the CD-DRP model shows an 11.21% lower overfitting rate compared to the GCRec model. However, experimental results also reveal a gap between the CD-DRP model’s testing F1-score and its F1-score at the end of training, indicating some degree of overfitting. Several factors may contribute to this: (1) The CD-DRP model’s causal discovery paradigm (see Section 3.1) is data-driven, aiming to align the variable generation and observational distributions to uncover the causal structure most likely to represent the underlying variable generation mechanism. This may mean that the discovered causal diagram reflects only part of the true causal structure. (2) Test data distribution may differ from that of the training data. Since repost prediction requires a temporal component, training data is based on user activity from the past, while test data is drawn from later periods. Over time, online social network services can undergo changes influenced by various internal and external factors.

In prediction tasks using causal inference methods, confounding variable modeling typically relies on prior expert knowledge, with existing studies [11,15,26] identifying confounding variables by establishing a dictionary of these variables or pre-calculating their distributions before model training. However, in this study’s context, these solutions are challenging to implement due to the limited prior knowledge of relevant causal relationships. To address this, we design a confounder memory network to simulate pre-representation of confounder features. This network identifies confounding variables during causal inference and dynamically updates its memory of these variables across data batches. Given its flexibility, this network is also suitable for other data mining tasks, supporting prediction tasks where causal relationships are not pre-defined.

Accurately predicting users’ repost behavior is essential for opinion analysis and recommendation systems. Most existing models predict repost behavior by identifying associations between features and outcomes. However, these models often overlook confounding variables, which can lead to the learning of spurious relationships between features and user behavior, ultimately hindering their generalization ability. To address this issue, we propose CD-DRP, a model that performs causal discovery and DRP simultaneously. The proposed causal discovery module and confounder memory network enable us to control the influence of confounding variables, even in the absence of complete prior knowledge of variable causality. Experimental results demonstrate that the CD-DRP model surpasses the state-of-the-art model in terms of both prediction performance (with a notable improvement of 2.54%) and mitigating overfitting (with a reduction of 7.44%). In the future, our aim is to give the CD-DRP model the ability to mitigate the influence of hidden confounders, as collecting information on various aspects of microblogging services can be challenging. By doing so, we can further enhance the generalizability of the CD-DRP model and augment its value in real-world settings.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Wu-Jiu Sun authored the main manuscript and conducted the experiments. Xiao Fan Liu contributed the theoretical concepts and made revisions to the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: In this study, we used a public dataset, which can be downloaded from the website if needed (https://www.aminer.cn/data-sna, accessed on 06 November 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://www.aminer.cn/data-sna#Twitter-Dynamic-Net (accessed on 13 November 2024).

2https://www.aminer.cn/data-sna#Weibo-Net-Tweet (accessed on 13 November 2024).

3Parameters from https://huggingface.co/roberta-base for TDN (accessed on 13 November 2024)

4Parameters from https://huggingface.co/bert-base-chinese for WNT (accessed on 13 November 2024)

References

1. H. Luo, X. Meng, Y. Zhao, and M. Cai, “Exploring the impact of sentiment on multi-dimensional information dissemination using COVID-19 data in China,” Comput. Hum. Behav., vol. 144, no. 2, 2023, Art. no. 107733. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2023.107733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. D. MacKenzie, K. Caliskan, and C. Rommerskirchen, “The longest second: Header bidding and the material politics of online advertising,” Econ. Soc., vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 554–578, 2023. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2023.2238463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. M. Ameri, E. Honka, and Y. Xie, “From strangers to friends: Tie formations and online activities in an evolving social network,” J. Mark. Res., vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 329–354, 2023. doi: 10.1177/00222437221107900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. L. Guan, H. Liang, and J. J. H. Zhu, “Predicting reposting latency of news content in social media: A focus on issue attention, temporal usage pattern, and information redundancy,” Comput. Hum. Behav., vol. 127, no. 3, Mar. 2022, Art. no. 107080. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. J. Wang and Y. Yang, “Tweet retweet prediction based on deep multitask learning,” Neural Process Lett., vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s11063-021-10642-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Y. Zhang and T. Hara, “Joint knowledge graph approach for event participant prediction with social media retweeting,” Knowl. Inf. Syst., vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 2115–2133, Sep. 2024. doi: 10.1007/s10115-023-02015-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. T. Zhong, J. Zhang, Z. Cheng, F. Zhou, and X. Chen, “Information diffusion prediction via cascade-retrieved in-context learning,” in Proc. 47th Int. ACM SIGIR Conf. Res. Dev. Inf. Retr., Washington, DC, USA, 2024, pp. 2472–2476. doi: 10.1145/3626772.3657909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. F. F. Leung, F. F. Gu, Y. Li, J. Z. Zhang, and R. W. Palmatier, “Influencer marketing effectiveness,” J. Market., vol. 86, no. 6, pp. 93–115, Jun. 2022. doi: 10.1177/00222429221102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Z. Wang, S. Shen, Z. Wang, B. Chen, X. Chen and J. Wen, “Unbiased sequential recommendation with latent confounders,” in Proc. ACM Web Conf., Lyon, France, 2022, pp. 2195–2204. doi: 10.1145/3485447.3512092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Q. Li, X. Wang, Z. Wang, and G. Xu, “Be causal: De-biasing social network confounding in recommendation,” ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–23, Jan. 2023. doi: 10.1145/3533725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. X. Yang, H. Zhang, G. Qi, and J. Cai, “Causal attention for vision-language tasks,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., Virtual Event, 2021, pp. 9847–9857. doi: 10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. L. Chen, Y. Zheng, Y. Niu, H. Zhang, and J. Xiao, “Counterfactual samples synthesizing and training for robust visual question answering,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., vol. 45, no. 11, pp. 13218–13234, Nov. 2023. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3290012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Y. Liu, G. Li, and L. Lin, “Cross-modal causal relational reasoning for event-level visual question answering,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 11624–11641, Oct. 2023. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3284038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. T. Wei, F. Feng, J. Chen, Z. Wu, J. Yi and X. He, “Model-agnostic counterfactual reasoning for eliminating popularity bias in recommender system,” in Proc. 27th ACM SIGKDD Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min., Singapore, 2021, pp. 1791–1800. doi: 10.1145/3447548.3467289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. D. Yu, Q. Li, X. Wang, and G. Xu, “Deconfounded recommendation via causal intervention,” Neurocomputing, vol. 529, no. 10, pp. 128–139, Jun. 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2023.01.089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Y. Zhu, J. Yi, J. Xie, and Z. Chen, “Deep causal reasoning for recommendations,” ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 1–25, Oct. 2024. doi: 10.1145/3653985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. S. Jamshidi et al., “Effective text classification using BERT, MTM LSTM, and DT,” Data Knowl. Eng., vol. 151, no. 3, 2024, Art. no. 102306. doi: 10.1016/j.datak.2024.102306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. M. Ghaderzadeh, A. Shalchian, G. Irajian, H. Sadeghsalehi, A. Z. Bialvaei and B. Sabet, “Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development against antimicrobial resistance: A narrative review,” Iranian J. Med. Microbiol., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 135–147, 2024. doi: 10.30699/ijmm.18.3.135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. L. Wang, Z. He, R. Dang, M. Shen, C. Liu and Q. Chen, “Vision-and-language navigation via causal learning,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 2024, pp. 13139–13150. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2404.10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. J. Pearl, Causality. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

21. Y. Jiang, R. Liang, J. Zhang, J. Sun, Y. Liu and Y. Qian, “Network public opinion detection during the coronavirus pandemic: A short-text relational topic model,” ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data (TKDD), vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 1–27, May 2021. doi: 10.1145/3480246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. B. Jiang, Z. Lu, N. Li, J. Wu, and Z. Jiang, “Retweet prediction using social-aware probabilistic matrix factorization,” in Proc. Int. Conf. On Comp. Sci., Wuxi, China, 2018, pp. 316–327. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-93698-7_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. R. M. Safari, A. M. Rahmani, and S. H. Alizadeh, “Retweeting behavior prediction based on dynamic bayesian network classifier in microblogging networks,” Appl. Soft Comput., vol. 164, no. 2, 2024, Art. no. 111955. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. L. Wang, Y. Zhang, J. Yuan, K. Hu, and S. Cao, “FEBDNN: Fusion embedding-based deep neural network for user retweeting behavior prediction on social networks,” Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 34, no. 16, pp. 13219–13235, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s00521-022-07174-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. D. Wang, W. Zhou, and S. Hu, “Information diffusion prediction with graph neural ordinary differential equation network,” in ACM Multimedia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia: ACM SIGMM, 2024. doi: 10.1145/3664647.3681363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. T. Wang, J. Huang, H. Zhang, and Q. Sun, “Visual commonsense R-CNN,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR), 2020, pp. 10760–10770. doi: 10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. X. Zheng, B. Aragam, P. K. Ravikumar, and E. P. Xing, “Dags with no tears: Continuous optimization for structure learning,” in Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., Montréal, QC, Canada, 2018, vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

28. Y. He, P. Cui, Z. Shen, R. Xu, F. Liu and Y. Jiang, “DARING: Differentiable causal discovery with residual independence,” in Proc. 27th ACM SIGKDD Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min., Singapore, 2021, pp. 596–605. doi: 10.1145/3447548.3467439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Z. Wang, X. Gao, X. Liu, X. Rui, and Q. Zhang, “Incorporating structural constraints into continuous optimization for causal discovery,” Neurocomputing, vol. 595, no. 3, 2024, Art. no. 127902. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2024.127902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Q. Xie, X. Zhang, Y. Ding, and M. Song, “Monolingual and multilingual topic analysis using LDA and BERT embeddings,” J. Informetr., vol. 14, no. 3, 2020, Art. no. 101055. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2020.101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. A. Grover and J. Leskovec, “node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks,” in Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min., San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016, pp. 855–864. doi: 10.1145/2939672.2939754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. K. Xu et al., “Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention,” in Int. Conf. Mach. Learn., Lille, France, 2015, pp. 2048–2057. [Google Scholar]

33. A. Vaswani, “Attention is all you need,” 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

34. Q. Zhang, Y. Gong, J. Wu, H. Huang, and X. Huang, “Retweet prediction with attention-based deep neural network,” in Proc. 25th ACM Int. Conf. Inf. Knowl. Manage., Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2016, pp. 75–84. doi: 10.1145/2983323.298380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. W. Hamilton, Z. Ying, and J. Leskovec, “Inductive representation learning on large graphs,” in Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., Long Beach, CA, USA, 2017, vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

36. S. Deng, H. Rangwala, and Y. Ning, “Learning dynamic context graphs for predicting social events,” in Proc. 25th ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min., Anchorage, AK, USA, 2019, pp. 1007–1016. doi: 10.1145/3292500.3330919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Z. Zhao et al., “Attentional image retweet modeling via multi-faceted ranking network learning,” in Proc. Twenty-Seventh Int. Joint Conf. Artifici. Intellig., Stockholm, Sweden, 2018, pp. 3184–3190. doi: 10.24963/ijcai.2018/442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. H. Yin, S. Yang, X. Song, W. Liu, and J. Li, “Deep fusion of multimodal features for social media retweet time prediction,” World Wide Web, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 1027–1044, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11280-020-00850-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. W. J. Sun, X. F. Liu, and F. Shen, “Learning dynamic user interactions for online forum commenting prediction,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Data Min., Auckland, New Zealand, 2021, pp. 1342–1347. doi: 10.1109/ICDM51629.2021.00168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. X. Ma and Y. Huo, “Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework,” Technol. Soc., vol. 75, no. 5, 2023, Art. no. 102362. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. S. Bhagat and D. J. Kim, “Examining users’ news sharing behaviour on social media: Role of perception of online civic engagement and dual social influences,” Behav. Inf. Technol., vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 1194–1215, 2023. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2022.2066019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. B. Li, S. W. Dittmore, O. K. M. Scott, W. -J. Lo, and S. Stokowski, “Why we follow: Examining motivational differences in following sport organizations on Twitter and Weibo,” Sport Manag. Rev., vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 335–347, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2018.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. A. Hapfelmeier, R. Hornung, and B. Haller, “Efficient permutation testing of variable importance measures by the example of random forests,” Comput. Stat. Data Anal., vol. 181, 2023, Art. no. 107689. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2022.107689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. I. Khemakhem, R. Monti, R. Leech, and A. Hyvarinen, “Causal autoregressive flows,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Artif. Intell. Stat., vol. 130, pp. 3520–3528, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools