Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Blockchain-Enabled Mitigation Strategies for Distributed Denial of Service Attacks in IoT Sensor Networks: An Experimental Approach

1 Department of Engineering Technologies, School of Science, Computing and Engineering Technologies, Swinburne University, Melbourne, 3122, Australia

2 School of Engineering, Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics College, RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC 3001, Australia

3 Department of Information Technology, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, 11432, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Library and Information Science, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, 24205, Taiwan

5 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, Asia University, Taichung City, 41354, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Bader M. Albahlal. Email: ; Cheng-Chi Lee. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Security and Privacy in IoT and Smart City: Current Challenges and Future Directions)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 3679-3705. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.059378

Received 06 October 2024; Accepted 20 November 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

Information security has emerged as a crucial consideration over the past decade due to escalating cyber security threats, with Internet of Things (IoT) security gaining particular attention due to its role in data communication across various industries. However, IoT devices, typically low-powered, are susceptible to cyber threats. Conversely, blockchain has emerged as a robust solution to secure these devices due to its decentralised nature. Nevertheless, the fusion of blockchain and IoT technologies is challenging due to performance bottlenecks, network scalability limitations, and blockchain-specific security vulnerabilities. Blockchain, on the other hand, is a recently emerged information security solution that has great potential to secure low-powered IoT devices. This study aims to identify blockchain-specific vulnerabilities through changes in network behaviour, addressing a significant research gap and aiming to mitigate future cybersecurity threats. Integrating blockchain and IoT technologies presents challenges, including performance bottlenecks, network scalability issues, and unique security vulnerabilities. This paper analyses potential security weaknesses in blockchain and their impact on network operations. We developed a real IoT test system utilising three prevalent blockchain applications to conduct experiments. The results indicate that Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks on low-powered, blockchain-enabled IoT sensor networks cause measurable anomalies in network and device performance, specifically: (1) an average increase in CPU core usage to 34.32%, (2) a reduction in hash rates by up to 66%, (3) an increase in batch timeout by up to 14.28%, and (4) an increase in block latency by up to 11.1%. These findings suggest potential strategies to counter future DDoS attacks on IoT networks.Keywords

The IoT is an emerging technology that has the capacity to transform the way locations, products and individuals are interconnected, allowing industries to leverage low-powered sensors along with embedded devices like low-powered single-board computers [1,2]. At the same time, blockchain technology has advanced significantly over the past decade, offering robust security solutions for various applications. Recent developments in IoT and blockchain show that blockchain can enhance the security of IoT end devices [1]. The integration of these technologies, termed the Blockchain of Things (BCoT), opens up new possibilities for secure IoT applications. However, it also brings several challenges, such as the need for efficient mechanisms to detect security vulnerabilities, monitor network performance, and identify network behaviour changes in real-time. Scalability issues, resource constraints of IoT devices, and ensuring data integrity across decentralised networks further complicate the seamless consolidation of blockchain with IoT systems [1,2]. Innovative approaches leveraging advanced technologies, such as machine learning algorithms and blockchain applications, have gained significant attention in addressing these challenges [2,3].

Concerns over the quality of care, safety, and privacy in aged care have led the Australian Government to establish a Royal Commission in aged care. With the increasing use of digital health records and IoT-based monitoring systems in aged care, the protection of information integrity and privacy has become a significant focus of the inquiry [3]. The commission’s findings have exposed significant issues of neglect and abuse within aged care facilities, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive reforms [3]. Integrating IoT technologies into aged care could address some of these issues by enabling real-time monitoring, enhancing care quality, and ensuring greater transparency [3]. IoT devices can provide critical data on environmental conditions, health metrics, and caregiver interactions, thereby improving safety and responsiveness [3,4].

One of the important recommendations is to deepen the understanding of blockchain technology’s user benefits and security challenges in the context of wider technology stacks, including AI and IoT [5]. After exploring blockchain’s integration, it is important to consider the innovative applications of Large Language Model (LLM)-based tools, such as ChatGPT, which potentially can enhance training and educational outcomes in these domains [6]. Blockchain technology can serve as a foundation for these advanced technologies and address their regulatory and security challenges to enhance their robustness [7]. By leveraging blockchain’s capabilities alongside IoT, it is possible to develop more secure and efficient systems for aged care, thus contributing to Australia’s technological advancement and improving care standards [7]. The government prioritises integrating these technologies with robust regulatory frameworks and invests in both IoT and blockchain advancements to create a safer, more transparent aged care environment [8].

In this research, a test network is used to evaluate the vulnerabilities of blockchain networks and evaluate the behavioural changes of various IoT blockchain sensor networks under DDoS attacks. These findings demonstrate that blockchain networks are susceptible to DDoS attacks, resulting in exceptionally high CPU core utilisation and decreased hash rates. Additionally, the experiments show that DDoS attacks can lead to an increase in batch timeout, which in turn causes greater block latency [9].

Objective: The primary objective of this research is to critically examine and identify the vulnerabilities of blockchain technologies when integrated with IoT devices, particularly under the stress of DDoS attacks. The goal is to empirically assess how these vulnerabilities affect the behaviour and performance of IoT sensor networks, providing a detailed understanding that could lead to more resilient security solutions.

Contributions: This study makes several significant contributions to the cybersecurity domain. Firstly, it introduces a real-world testbed that combines widely used blockchain platforms with IoT environments, moving beyond the theoretical models typically found in the existing literature. This approach enabled the documentation of specific behavioural changes under DDoS conditions, including variations in CPU core usage, hash rates, batch timeouts, and block latencies. These findings are critical for developing effective defence mechanisms [10]. Additionally, this analysis of blockchain-specific vulnerabilities in low-powered IoT devices underlines the urgent need for tailored cybersecurity measures that can withstand advanced DDoS attacks. Together, these contributions offer a foundation for future innovations in securing IoT and blockchain technologies against increasingly sophisticated cyber threats [10].

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review, covering key concepts of blockchain technology, IoT vulnerabilities, and the integration of both in enhancing security. Section 3 outlines the research methodology and details the experimental setup employed in testing the blockchain vulnerabilities under DDoS attack scenarios. Section 4 presents a detailed analysis of the experimental results, highlighting the impact of DDoS attacks on IoT sensor networks through metrics such as CPU core usage, hash rate, batch timeout, and block latency. Section 5 discusses the implications of these findings and suggests approaches for improving security measures in blockchain-based IoT systems. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by summarising the research contributions and suggesting avenues for future research.

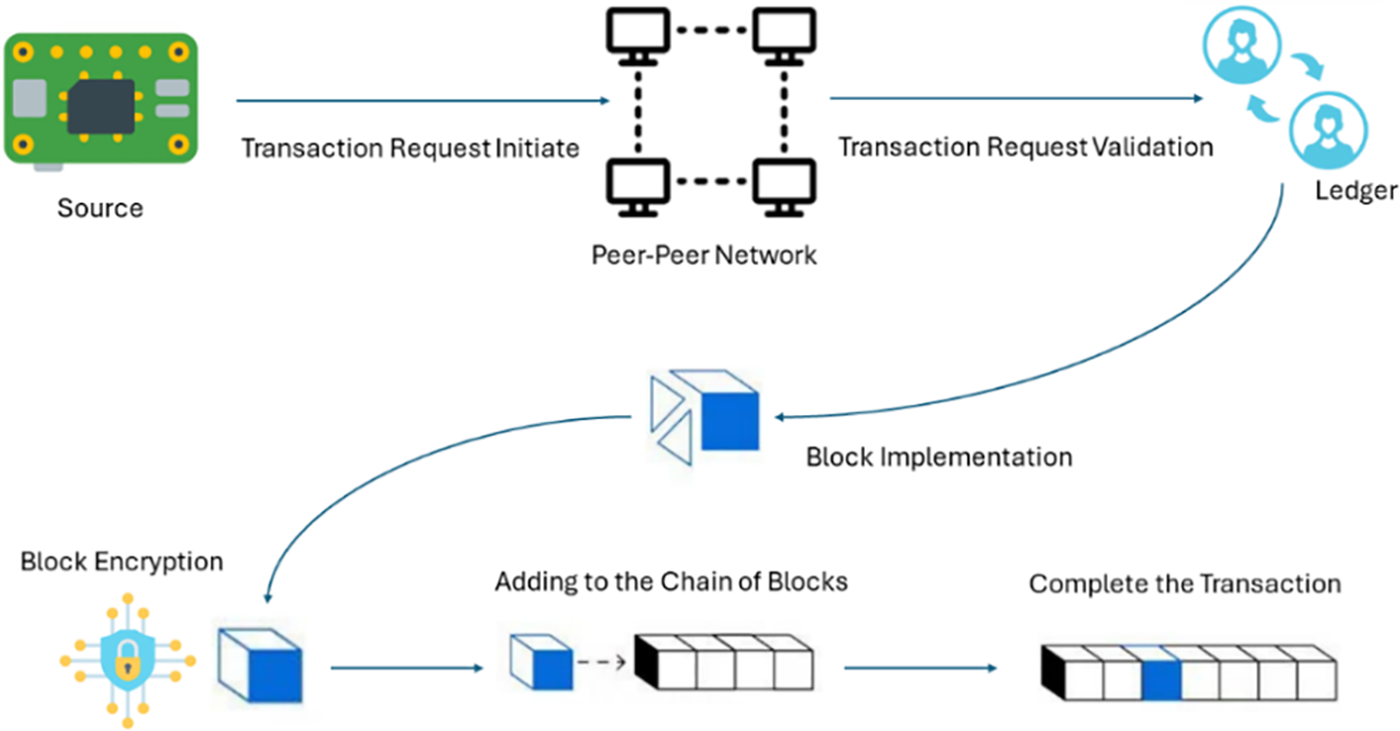

Blockchains operate using Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) to maintain records of transactions over a decentralised system. Blockchains are widely recognised for their transparency, immutability, and security. They create a chain of blocks using the DLT, and each block contains a group of transactions. Once a block is appended to the chain, it is permanently secured and cannot be altered [11]. Fig. 1 illustrates the basic structure of a blockchain, showing how each new block of data is hashed and subsequently added to the end of the chain.

Figure 1: Blockchain transaction process flow

All blockchain transactions will be verified in a blockchain network when data blocks are created and digitally signed [11]. Users should not be allowed to use the same blockchain account without legal authorisation. Also, all stored information should be encrypted, and the ledger system cannot be altered without legal permission. Modern blockchain applications contain information and user validation processes to protect integrity [12]. Also, these blockchain applications are automated using consensus decision-making algorithms. Verified blocks cannot be replicated, and data block conflicts need to be resolved immediately [12].

Different types of blockchain networks provide various services, allowing for a wide range of applications. Public blockchains allow unlimited read and write access on a permissionless basis, enabling anyone with an internet connection to join the network, validate transactions, and contribute to the consensus process [12]. These networks are noted for their transparency and security, ensured through cryptographic algorithms, making transactions visible to all users [9]. Conversely, private blockchains restrict network access, which is controlled by a central authority or consortium that determines participation and transaction validation. This structure enhances privacy since only authorised participants can view or interact with the data [9].

Hybrid blockchains combine features from both public and private blockchains. They offer controlled access to specific services within the network while maintaining some level of public access, allowing organisations to protect sensitive information while benefiting from the transparency and security of public blockchains [12,13]. Consortium blockchains, managed by multiple organisations, share similarities with hybrid blockchains. However, they limit the creation of blocks and validation of transactions to a select group of nodes, which combines transparency with the control and efficiency needed in business operations. These networks are typically fine-tuned for performance, involving fewer trusted participants, resulting in quicker transaction processing and reduced energy consumption [8].

Sidechain networks operate parallel to the main blockchain, enhancing its functionality and scalability. These are independent blockchains connected to the main chain but function under different rules and consensus mechanisms to address issues like scalability and interoperability without overloading the main chain [14]. They are particularly useful for testing updates or new features in a controlled environment and enabling data transmission between different systems [1].

Furthermore, integrating permissioned and permission-less blockchain architectures can lead to enhanced performance and security, offering tailored solutions for varying organisational needs [13]. This segmentation highlights the adaptability of blockchain technology, underscoring its potential to revolutionise digital transactions and record-keeping across various sectors.

Connecting sensors and actuators through networks allows for the collection and processing of data, which in turn helps communities improve their living and working environments [1]. IoT applications span numerous sectors, including smart homes, where devices like lights, security cameras, and appliances can be controlled remotely for increased convenience and energy efficiency; smart cities, where IoT systems manage traffic, waste, and utilities to improve urban living; and industrial IoT, where sensors and automation enhance operational efficiency, and predictive maintenance [14]. Integrating IoT technology into daily operations enables more informed decision-making and enhances operational efficiencies [15]. Ultimately, the adoption of IoT results in process automation, cost reductions, and improved service quality.

Despite the advantages of IoT, IoT devices with limited resources and capabilities can be vulnerable to cyber threats. To address these security concerns, researchers have turned to blockchain technology as a promising solution for safeguarding IoT devices and networks [15,16]. This synergy has given rise to BCoT, which integrates blockchain with IoT technologies. By combining the decentralised and secure nature of blockchain with the connectivity of IoT, this approach not only enhances the security of IoT ecosystems but also enables more robust data integrity and user privacy [17,18].

The primary goal of BCoT is to harden the security and efficiency of IoT. To achieve this, BCoT has identified four crucial metrics that serve as the foundation for its framework [19]. These parameters are designed to strengthen the overall integrity of IoT systems, enhance data protection, and improve operational performance, ultimately leading to a more resilient and trustworthy IoT ecosystem [1]. The parameters can be stated as follows.

Ensuring that devices can operate together seamlessly, despite differences in manufacturers or protocols, is important for the effective functioning of cyber-physical systems. Standardised blockchain interfaces play a key role in this, particularly in facilitating the efficient transmission of data across blockchain-based IoT networks [1]. A blockchain-based compound layer is often implemented among the devices utilising blockchain technology to facilitate interoperability. Also, the BCoT supports reliable access to peer-to-peer IoT sensor networks by improving network interoperability [1].

2.2.2 Information Traceability

The capability to trace and validate data within an IoT blockchain is essential for enhancing the performance of blockchain networks. Implementing a robust system that facilitates tracing and validating blockchain data is paramount in a network that integrates blockchain and IoT technologies. Moreover, blockchain technology offers timestamps for every IoT node, guaranteeing that all data points are accurately tracked and authenticated. This ensures a higher level of data integrity, accountability, and reliability across the network [1].

The reliability of information encompasses the quality and credibility of the information being transmitted [1]. Blockchain technology employs encryption algorithms, digital signatures, and timestamps to safeguard the data, enhancing its security and integrity [1]. The overall performance of data transmission across blockchain networks can be improved by bolstering the trustworthiness of data within the blockchain through a decentralised infrastructure with redundant nodes that handle failures and disruptions [1].

Autonomic interactions in the IoT refer to the capability of IoT devices to independently manage, coordinate, and optimise their operations and interactions with minimal human intervention [1]. The implementation of autonomic interactions significantly enhances the capacity of IoT networks and systems by linking them to trustworthy blockchain networks, thereby circumventing the reliance on unverified third-party networks [1]. Smart contracts are typically used to enable autonomic interactions. The interactions occur between sensor nodes within the blockchain, leading to more efficient and reliable data exchange and processing [1].

DDoS attacks have become a common threat to IoT devices and networks due to their limited processing power, security features, and constant internet connectivity, which are further compounded by various security and privacy challenges, as detailed in [20]. DDoS attacks exploit bottlenecks in any system by sending more network traffic than the network can handle [20]. DDoS attacks target the availability of a particular network, and failure to handle the network traffic causes service outages and service downtime [21]. A DDoS attack is the most common type of blockchain network attack. Although blockchains use a decentralised network architecture, intruders can still overwhelm it [21].

Many intruders overload the blockchain network by the number of blockchain transactions. The increment of block transactions can cause transaction flooding. DDoS attacks are more frequent on public blockchain networks, increasing the blockchain network’s block transaction rate (BTR) [22]. Intruders use spam block transactions as a common DDoS attack method. Blockchain ledger systems can be corrupted as spam blocks are added to the ledger system. DDoS attacks may highly impact blockchain networks via the following approaches.

Blockchain applications function on interconnected blockchain nodes, all linked within the same network. In the event of a DDoS attack that inundates the network with a high volume of spam blocks, the performance of node hardware can suffer significantly [22]. This is particularly critical for low-powered nodes, as those with limited CPU capacity and memory are susceptible to crashing under such conditions [22].

2.3.2 Blockchain Software Failure

Blockchain applications serve as the main platform operating on blockchain nodes. These applications facilitate the implementation of the blockchain network, process data blocks, and conduct transactions [21]. Each blockchain software program has a predefined limit on data transactions, and exceeding this limit can lead to crashes of the blockchain platform. Software malfunctions may arise when the transaction thresholds are surpassed [21].

2.3.3 Network Traffic Congestion

Blockchain operates as a network utilising Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) protocols for connectivity. Each blockchain node sends and receives data blocks [22]. During a DDoS attack, the network can become completely overwhelmed by the influx of spam blocks, reducing network bandwidth, which can adversely affect blockchain services [22].

The blockchain ledger is essential to any blockchain network, serving as the repository for all data transactions [21]. The data blocks must first undergo a verification process to incorporate block transactions into the ledger. Nevertheless, an influx of spam data blocks can overload the blockchain ledger systems. Blockchain ledger can be potentially corrupted by block flooding [21].

Adequate hardware processing power, memory and network bandwidth may reduce the impact of DDoS attacks. Also, software hardening and prior identification of potential network vulnerabilities can be used to mitigate the effects.

According to [23], IoT is an emerging technology with promising growth. As the authors have emphasised, IoT is involved in developing from smart devices to smart cities [23]. However, most IoT devices are easy to penetrate and hack. The authors present and survey security risks and concerns that IoT faces. The paper highlights that IoT devices can be controlled remotely and provide necessary tech support from anywhere in the world [23]. Apart from commercial and personal use, IoT can also be used to serve the community, such as aged care and hospitals. The authors have categorised security risks into three main categories: networking, communication and management. According to [23], this paper emphasises prevalent attacks and assesses current security solutions.

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN), Machine to Machine (M2M), and Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) have evolved as integral components of IoT technology. The security concerns of CPS, WSN and M2M also now arise in the context of IoT [23]. As the authors highlighted, IoT is typically vulnerable to concerns about privacy, integrity, and data confidentiality. The authors have emphasised possible security solutions, including blockchains, and the effectiveness of blockchain technology. The authors also focused on user authentication, authorisation, availability and energy efficiency of IoT and blockchains [23].

IoT has emerged as a revolutionary paradigm for interconnection, communication and resource-constrained smart devices [24]. Additionally, these devices are capable of communication and are connected to the Internet through various underlying technologies and protocols, including Zigbee, RFID, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), LoRa, Wi-Fi, and Sigfox [24]. The IoT enables access to various domains, including agriculture, healthcare, automotive and energy. However, sensitive data can also be vulnerable to security threats due to intensive data exchange, centralised processing and interoperability [24]. The authors highlighted that blockchain is a potential solution for securing IoT networks. However, the consolidation of blockchain and IoT technologies can also be challenged by scalability, data privacy, performance, and governance [24]. Also, the authors have emphasised that data storage, processing power, and consensus algorithms are possible technical challenges for the fusion of blockchain and IoT technologies [24].

Blockchain technology is known for its benefits, such as reduced cost, transparency, privacy and security [24]. The authors have conducted a bibliometric analysis to identify the application and technical aspects of blockchain-IoT in various domains such as autonomous vehicles, smart grids, UAVs and supply chains. The authors noted that Ethereum was the first blockchain platform that supported blockchain smart contracts, and it runs on an Ethereum blockchain runtime engine [24].

IoT and Software Defined Networks (SDNs) are susceptible to DDoS attacks, and addressing these attacks promptly is crucial [25]. According to the authors, DDoS attacks have become more sophisticated over the years, and the authors have proposed DDoS attack mitigation techniques and solutions [25]. The solutions are based on network type, attacker location, victim location and severity of the attack. As per the authors, UDP-based DDoS attacks have significantly increased compared to TCP attacks [25]. According to Chaganti et al., UDP is more vulnerable to UDP Mem-cached vulnerability, which can be due to the security loopholes of internet service providers and cloud service providers such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Platform (GCP) [25].

Chaganti et al. emphasised that IoT security gateways and strong secured IoT network protocols such as Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), Asynchronous Messaging Protocol (AMP), Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) help to mitigate potential DDoS attacks [25]. Also, as the authors have noted, using blockchains, sufficient processing power, and multivendor IoT platforms are other potential solutions to reduce the risk of DDoS attacks [25]. Furthermore, cloud orchestration and dedicated SDN controllers are also other possible DDoS mitigation techniques. According to [25], detecting and compromising DDoS botnets is an effective way of mitigating DDoS threats. Blockchains can be used to identify active DDoS botnets and raise DDoS attack alerts.

According to [26], the blockchain ecosystem, including mining pools, IoT networks, Bitcoin nodes, and pool protocols, has developed significant resistance to DDoS attacks, enhancing its security resilience. Despite that, the current advancements in blockchain technology also have weaknesses, such as transaction delays, high processing power requirements, node coordination concerns, and network bandwidth [26]. However, as the authors highlighted, the blockchain ecosystem detects DDoS attacks by using deep learning techniques. Chaganti et al. proposed a blockchain ecosystem architecture for P2P networks that can be used to mitigate DDoS attacks. The authors proposed delegated proof of stake (DPoS) and Byzantine fault tolerance (PBFT) consensus algorithms to minimise the severity of DDoS attacks [26].

Blockchain technology has considerable potential to secure IoT networks and devices [27]. Hackers use DDOS attacks to hijack IoT networks, and IoT networks can be secured using blockchain public keys. As the authors have highlighted, blockchain smart contracts can improve the security and integrity of unsecured IoT networks [27]. The paper discusses effective techniques to detect DDoS attacks. The paper’s novelty is that it is based on blockchains and DDoS threat detection. As the authors noted, IoT subsystems are more vulnerable to DDoS attacks than core networks, including power grids [27]. The authors proposed machine learning algorithms and performance metrics to detect DDoS attacks. Software Define Networks (SDN) and Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA) are also potential security features that can used to identify DDoS threats [27].

Khan et al. [27] proposed a secure blockchain model for blockchain botnet detection. They also discussed IoT data streaming using IPFS blockchain, DDoS attack prediction metrics, and modelling the impact of such threats [27]. Furthermore, the authors discussed non-blockchain-based DDoS techniques such as random forest and mutual information-based DDoS detection techniques. The blockchain prevents unauthorised data access and provides data processing with no additional cost [27]. Mirai DDoS attack is an IoT hazardous malware that can cause severe consequences such as device firmware damage using Mirai botnets. The authors suggest blockchain as a potential solution to prevent Mirai DDoS attacks [27].

DDoS attack prevention method using Nu-Cypher Re-Encryption infrastructure and hashing was proposed by [28]. Authors have highlighted, DLT are potential security solutions for industrial IoT networks [28]. Industrial IoT (IIoT) networks face critical cyber challenges, including data transmission, trust, user privacy, and information preservation [28]. In addition, industrial IoT networks have inadequate computational power, which makes them more vulnerable to DDoS attacks. The authors discuss blockchain-enabled IoT networks and their implementation challenges, a Hyperledger Sawtooth blockchain-enabled framework and trusted execution networks to deliver sensitive information [28]. As the authors have emphasised, IIoT networks typically exchange information through Distributed Application (DAPP), which raises concerns about transparency, data privacy, traceability, and provenance [28].

Also, DAPP requires permission for blockchain modular infrastructure to handle transactions and data executions [28]. The paper emphasised the importance of industrial data management, DLT communication protocols, decentralised network connectivity and DDoS threat mitigation. The Hyperledger blockchain leads to the building of intelligent, smart, and secure IIoT networks with robust security features [28]. Hyperledger technology provides an efficient, reliable and sustainable blockchain platform that manages network availability against DDoS threats. Also, the Hyperledger platform consumes considerably low computational power compared to other blockchain networks [28]. Four key layers were proposed for implementation in blockchain-based IIoT networks: the application layer, support layer, perception layer, and secure business layer. The application layer handles the blockchain applications that run on IoT devices, while the support layer controls the network architecture and data transmission [28]. The perception layer is integrated with the IoT sensor devices, while the secure business layer is used to manage secure industrial transactions [28].

Blockchains are recognised for enabling groundbreaking innovations in business domains [29]. The authors describe blockchain-specific risks under four domains. They are blockchain structure vulnerabilities, attacks on consensus mechanisms, blockchain application-oriented attacks and peer-to-peer network attacks [29]. As the authors have emphasised, blockchain structure vulnerabilities are typically based on network implementation and operating principles [29]. Blockchains can have orphaned blocks that are not validated by the ledger system, which may cause architecture conflicts and routing malfunctions. Consensus mechanisms are identified as a core component of a blockchain network, responsible for decision-making and chain management [29]. Attacks on consensus mechanisms are a typical threat to which systems can be vulnerable. Attacks on consensus mechanisms are a common threat, with 51% of blockchain attacks targeting this area due to the considerable computational power required [29]. Also, application-oriented attacks have three major concerns: time-jacking, cryptojacking, and replay attacks. These attacks typically target blockchain applications and their services. Peer-to-peer network attacks are also another classical blockchain attack type that targets the functionality of the network. These peer-to-peer network attacks can be categorised as Eclipse attacks, Selfish mining attacks, Classical block with-holding attacks, and Sybil attacks [29].

Kevin Jonathan et al. emphasised that virtual reality, AI, and IoT are being adopted for daily community use [30]. As an emerging technology, blockchain provides convenient and reliable network services in a secure manner. Although blockchains are typically developed as a cryptocurrency and financial service, modern blockchains are also being used in many sectors, including IoT [30]. Blockchains provide decentralised, open-source, transparent, autonomous, immutable, and anonymous services and features to secure IoT networks. DAPP testing using Ethereum, Bitcoin, and Solidity blockchain platforms was proposed to understand common blockchain security threats [30]. Common vulnerabilities such as Bitcoin partitioning, solidity compiler bugs, chain synchronisation, and Ethereum Geth vulnerabilities are prevalent in blockchain architecture. Additionally, weak smart contract security design is identified as a key vulnerability that can lead to blockchain security threats [30]. Identity management of blockchain nodes, energy consumption, adversary tolerance, block creation speed, and scalability are recognised as factors that security threats, including DDoS, majority attacks, and re-entrancy attacks, can impact [30].

DDoS attacks exploiting IoT networks through limited computer resources such as memory and CPU are highlighted [31]. Because IoT devices are typically resource-constrained, blockchain can be a potential solution to prevent DDoS threats. The authors discussed how IoT networks are vulnerable to DDoS attacks and the use of blockchain technology to mitigate such attacks [31]. Also, the authors categorise the existing blockchain-based solutions into four categories. They are distributed architecture-based solutions, traffic control-based solutions, access management-based solutions and Ethereum-based solutions [31]. According to the authors, DDoS attacks on domain name systems (DNS), constrained application protocols (CoAP), and software-defined networks (SDN) commonly happen worldwide, targeting wide area networks [31]. The authors conducted an extensive survey on DDoS mitigation through blockchain and proposed a distributed network structure as a potential solution.

According to Shah et al., the sequence of blocks, data block structure, and smart contracts are key features of the distributed architecture. The authors conducted a survey on RFID networks, Voice over IP (VoIP) and DNS to identify potential DDOS vulnerabilities [31]. As the authors have emphasised, the signing and verification process of the blockchain transactions is an important feature that is carried out using a digital signature. A digital signature is used to identify legitimate users with a pair of Public and Private encryption keys [31]. When a certain user wants to sign a transaction, the user first generates a Hash value, signs the Hash value using the user’s Private Key, and sends it to the other user along with transaction data. The destination user verifies the transaction by comparing the decrypted Hash [31].

Although blockchain is identified as a potential solution, it also faces highly sophisticated DDoS attack threats [32]. The authors provided a comprehensive review of the challenges of using blockchains to secure traditional server-based networks. As the paper emphasised, cloud ecosystems are also currently facing DDoS disruptions and service degradation [32]. The primary target of the DDoS attack is network availability. DDoS malicious flooding can cause severe consequences by exceeding bandwidth. Similarly, DDoS attacks generate higher quantities of packets and concentration toward the victim node [32]. The authors suggest a Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) to track malicious network traffic. Also, as the authors have highlighted, DDoS attacks can also be visualised as brute force attacks and spoofing attacks by blocking all legitimate network users. Also, DDoS attacks can either target a single user or multiple users [32]. Moreover, they can be performed at the MAC or IP layers and geographically distributed. The authors have categorised DDoS attacks into three categories: application layer attacks, resource exhaustion attacks, and volumetric attacks [32].

Selvarajan et al. proposed a Smart Decentralised Identifiable Distributed Ledger Technology-based Blockchain (DIDLT-BC) model aimed at enhancing security in Cloud-IoT environments. As IoT devices are increasingly integrated with cloud infrastructure, ensuring secure communication and data management becomes critical [33]. The proposed model leverages blockchain technology to provide decentralised and tamper-resistant security solutions while also incorporating identifiable mechanisms to trace and verify the identities of devices within the network [33].

The DIDLT-BC model ensures data integrity, confidentiality, and authentication by using a combination of blockchain’s distributed ledger, cryptographic protocols, and identity management techniques. It enables secure data transactions between IoT devices and cloud systems, preventing common attacks such as data tampering, unauthorised access, and identity spoofing [33]. The decentralised nature of blockchain eliminates single points of failure, enhancing resilience and reliability. Furthermore, the model is scalable and efficient, designed to handle the large and dynamic nature of IoT ecosystems, making it a robust solution for securing Cloud-IoT systems [33].

Manoharan et al. emphasised that implementing IoT with blockchain networks, combined with machine learning algorithms, enhances security. As IoT networks grow, they become more vulnerable to cyber threats due to the vast number of interconnected devices [34]. The paper proposes a solution by integrating blockchain technology, which offers a decentralised and immutable ledger, to improve the security of IoT ecosystems. Blockchain is employed to ensure data integrity, secure communication, and decentralised control across IoT devices, mitigating risks like data tampering, unauthorised access, and identity spoofing [34].

To further enhance security, the paper incorporates machine learning algorithms into the framework. These algorithms enable anomaly detection and predictive analytics, identifying potential security threats and abnormal behaviours in real-time [34]. The synergy between IoT, blockchain, and machine learning strengthens the overall system by providing robust defences against cyberattacks, ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data. The proposed model not only addresses current security challenges but also scales effectively with the increasing complexity of IoT networks, making it a comprehensive approach to IoT security enhancement [34].

At present, only a limited number of papers have addressed potential security vulnerabilities and anomalous behaviour within blockchain technology. Additionally, there has been limited research evaluating these blockchain security issues through testing on actual systems. Most of the existing literature has not adequately acknowledged the significance of blockchain security vulnerabilities in real-world blockchain implementations. This paper aims to address this gap. Table 1 provides a summary of the existing research work and its limitations.

The approach of this research is conducting experiments with real systems to provide a reference for improving the security of blockchain-based IoT sensor networks. Despite the recognised potential of blockchain as a security solution for IoT sensor networks, many current commercial blockchain applications continue to be vulnerable to various security threats, including DDoS attacks. This is a significant concern, as this study demonstrates that blockchain applications are still at risk of cybersecurity issues, particularly since IoT low-powered devices. Therefore, it is important to understand the security vulnerabilities associated with blockchain and related anomalous behaviours that can help us detect such threats. The research methodology and experimental setup are outlined in the following section.

3 Research Methodology and Experimentation Setup

This paper outlines the approach that integrates practical experimentation with quantitative data analysis, using a controlled lab setting and a real prototype for all tests. This section details the research methodology and the development of the test bed.

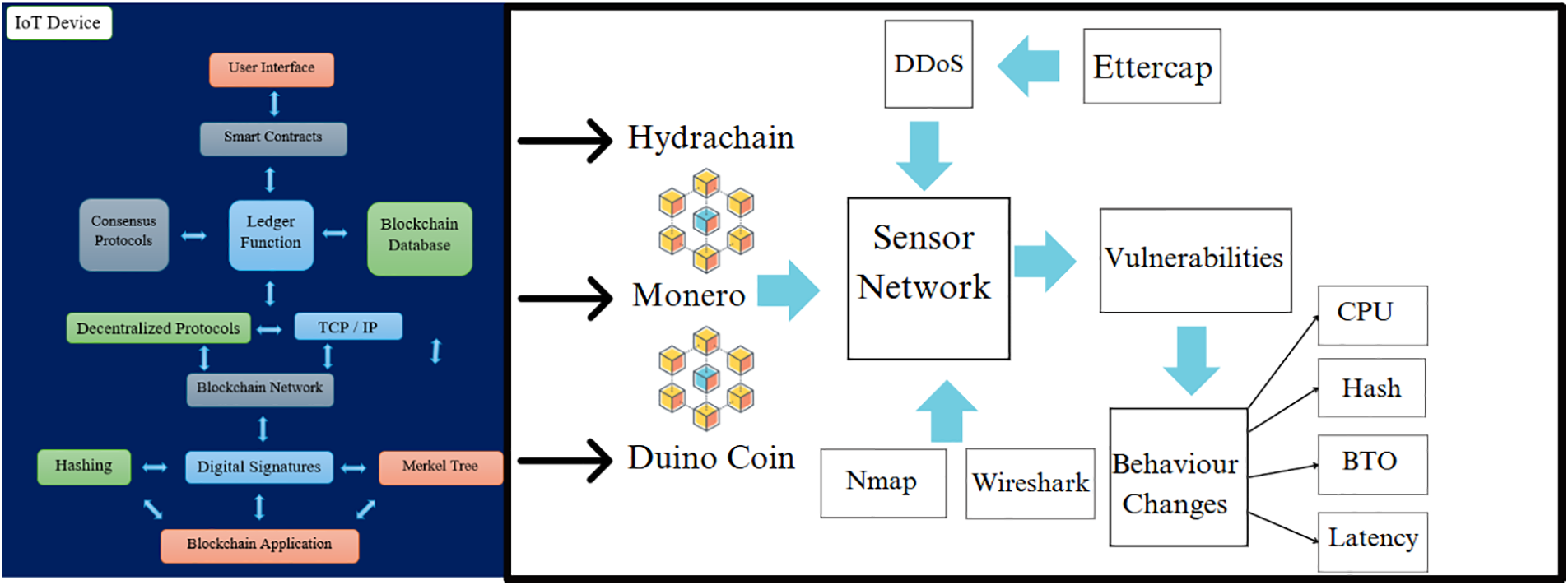

Experimental data collection and experimental setup: Experimental data was gathered during the processing of blockchain applications to assess the impact of DDoS attacks on network behaviour. This study utilised a blockchain-based testbed where a series of 100 DDoS attacks were conducted to highlight potential security vulnerabilities. These attacks were instrumental in understanding the changes in network behaviour, and the data collected helped evaluate the resilience of the blockchain system under stress conditions. Fig. 2 shows the research methodology and configuration process.

Figure 2: Research methodology and configuration process

Tools and techniques for data analysis: The quantitative analysis of the collected data was conducted using MATLAB and Microsoft Excel. These tools were chosen for their robust data handling and analytical capabilities, suitable for processing and analysing large datasets typical in blockchain applications [35]. MATLAB was primarily used for more complex statistical analysis and modelling, while Excel facilitated preliminary data sorting and quick visual data inspections.

Data metrics and visualisation: This research focuses on several key performance metrics affected by DDoS attacks: CPU usage, hash rate, batch timeout, and block latency. High CPU usage often indicates system inefficiencies and data processing bottlenecks, crucial for devices with limited computational resources like IoT sensors. The hash rate measures the system’s capability to validate transactions, reflecting on the security and performance of blockchain cryptographic tasks [9]. Batch timeout and block latency metrics help in understanding the network’s efficiency and response time, respectively.

Visualisations such as box plots were used to illustrate the distribution of these metrics under normal and attack conditions. The box plots provided a clear, visual representation of the central tendencies and variability of each metric, aiding in a comparative analysis between the normal operation and under the stress of DDoS attacks. Percentage changes were also calculated to quantify the impact of the attacks on the system performance compared to normal operations.

Security tools and vulnerability assessment: Nmap was employed to perform a vulnerability assessment by scanning open network ports targeted at blockchain-specific TCP ports such as 9333, 8333, 9999, 30,303, and 22,556. The assessment provided detailed reports of open ports and identified the IP and MAC addresses of vulnerable nodes. This assessment was critical in understanding the network’s susceptibility to DDoS attacks [1,36].

The use of Wireshark for analysing blockchain transaction logs and Linux system tools like MPSTAT and DSTAT for monitoring CPU core utilisation further supported the detailed investigation of network behaviour under attack conditions [1].

3.2 Hardware Test Bed Development and Resources

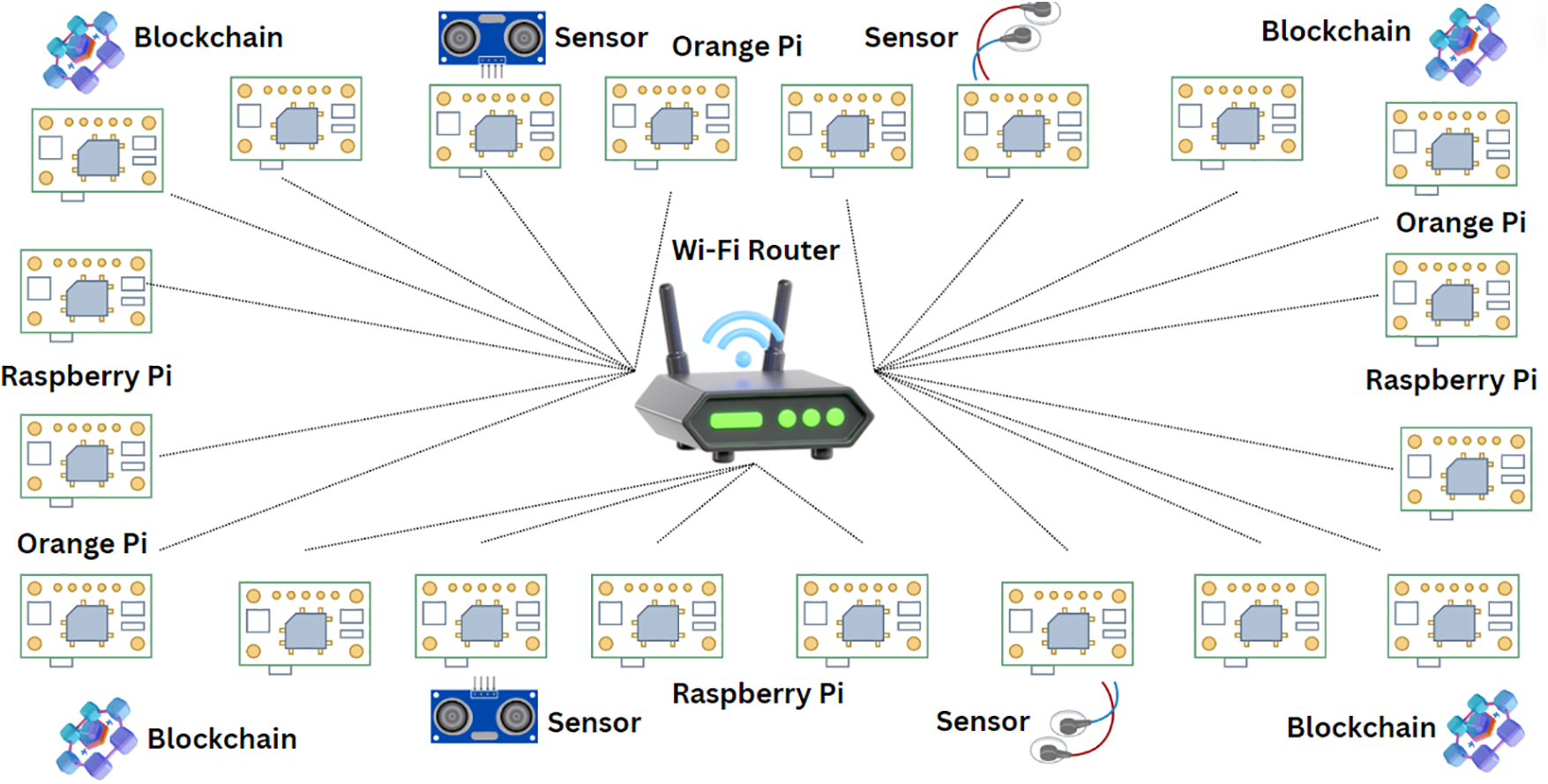

The test setup was developed using a combination of twenty single-board computers. Raspberry Pi and Orange Pi devices were used to develop the prototype network. Notably, the Orange Pi Zero devices provide specifications that are comparable to those of the Raspberry Pi 3B models [37]. Orange Pi was chosen due to a shortage of Raspberry Pi supplies. A prerequisite for deploying blockchain applications is the installation of an operating system, which necessitates certain minimum hardware capabilities. Many blockchain applications are developed for 64-bit architectures, leading to a limited availability of 32-bit commercial options [37]. Furthermore, the most prevalent ARM-Linux distributions are 32-bit systems, with many 32-bit blockchain applications requiring at least 4 GB of storage and 512 MB of RAM for installation [37]. It is essential to note that not all IoT devices have the required minimum hardware specifications to support an operating system and effectively run blockchains. Hence, selecting devices capable of handling the demands of blockchain technology is crucial for successful implementation in resource-constrained environments. Fig. 3 illustrates a map of the IoT sensor network.

Figure 3: Network map

To measure the performance of this test bed, low-energy sensors were integrated to efficiently collect and transmit data across the blockchain network, using a wireless router for connectivity [37]. The data collection framework includes a range of primary sensors: the LM-35 temperature sensor, HC-SR04 distance sensor, a water sensor, a pressure sensor, and a tilt sensor. These sensors are fully compatible with most single-board computers, which serve as a backbone of all blockchain nodes [37]. The sensors are connected using jumper wires through the General-Purpose Input Output (GPIO) pins, enabling seamless data acquisition and transmission. This setup not only ensures real-time data monitoring but also leverages the decentralised nature of blockchain technology for security and reliability in data handling [37].

The Raspberry Pi devices are versatile single-board computers that have significantly impacted the tech community since their release. Raspberry Pi Model 3B specifically features an ARM Cortex-A53 processor with 1 GB of RAM. Also, Raspberry Pi 3B consists of 802.11n wireless LAN. The device also includes four USB 2.0 ports, Bluetooth 4.1, a 40-pin GPIO header, HDMI output, and a display interface (DSI) [38]. Additionally, it has a microSD slot for storage. With its combination of processing power and connectivity options, the Raspberry Pi 3B is well-suited for a variety of computing tasks, from basic desktop use to embedded systems and IoT applications [38].

One of the key advantages of the Raspberry Pi 3B in the context of IoT is its affordability, which allows for the cost-effective deployment of multiple devices in large-scale IoT networks. Its compact size is another advantage, enabling it to be embedded in various environments [39]. The extensive GPIO pin header is particularly valuable for IoT, as it allows easy interfacing with a wide range of sensors, actuators, and other peripherals, facilitating the development of custom IoT solutions [39]. Additionally, the built-in wireless LAN and Bluetooth provide seamless connectivity to other devices and networks, which is crucial for IoT applications that require constant communication and data exchange [39].

The Orange Pi Zero 2 is also a versatile and compact single-board computer, and it is powered by the Allwinner H616 quad-core ARM Cortex-A53 processor with 1.5 GHz [40]. The board comes in two memory configurations: 512 MB and 1 GB of DDR3 RAM, allowing users to choose based on their performance needs. It features a microSD card slot for expandable storage, and it supports multiple operating systems, including various Linux distributions and Android [40].

In terms of connectivity, the Orange Pi Zero 2 includes Wi-Fi (802.11 b/g/n) and Bluetooth 5.0, offering wireless communication options for IoT and other networked applications [40]. It also has a 100 Mbps Ethernet port for wired network connections. The board’s I/O options include a 26-pin GPIO header, which provides access to various interfaces such as I2C, SPI, and UART, making it suitable for connecting a wide range of sensors and peripherals. The device also includes a USB 2.0 port and an IR receiver [40].

3.3 Software Use and Resources

For this blockchain network, experiments were conducted with the Ethereum, Monero, Hydrachain, Duino Coin, Bitcoin, IPFS, and Multichain applications. Consequently, the decision was made to use the Duino Coin, Monero, and Hydrachain platforms [1]. These blockchains were chosen due to their compatibility with most IoT hardware, widespread use, programmability, power consumption efficiency, and open-source platforms. To carry out the necessary configurations, SSH Putty software was used to access each node. All blockchain platforms were installed on the ARM Linux [17].

It was discovered that the Multichain Command Line Interface (CLI) version was not compatible with the operating Linux version, and its Graphical User Interface (GUI) version was limited to 64-bit architecture, resulting in higher power consumption [1]. Additionally, both Bitcoin and Ethereum platforms exhibited higher energy consumption than Hydrachain, Monero, and Duino coins. Bitcoin also failed to provide the private blockchain capabilities needed for this IoT sensor network data transmission, as its features are primarily geared towards financial use. Furthermore, IPFS was deemed unsuitable for Local Area networks because it is better suited for cloud data storage and transactions [17].

Hydrachain is an extension of the Ethereum blockchain designed to facilitate the creation of permissioned and private blockchain networks [41]. It is specifically tailored for enterprises that require a secure and customisable blockchain environment. Hydrachain is compatible with the low powered devices, allowing it to support smart contracts written in Solidity [38]. This compatibility ensures seamless integration with existing Ethereum tools and libraries. Hydrachain offers features such as customisable consensus algorithms, which enable the deployment of various consensus models depending on the use case. It supports Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) protocols, enhancing security and resilience against malicious activities. Additionally, Hydrachain provides access control, ensuring that only authorised participants can join the network or interact with specific contracts and transactions [38,41].

Monero is a privacy-focused blockchain that operates on its own blockchain network, designed to provide secure, private, and untraceable transactions [38]. Unlike many other blockchains, Monero uses a unique combination of privacy-enhancing technologies, such as Ring Signature Confidential Transactions (RingCT) and Stealth Addresses, to ensure that the details of transactions, including the sender, recipient, and amount, are obfuscated. Monero’s blockchain is built on the CryptoNote protocol and utilises a Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus mechanism [38]. It employs the RandomX algorithm, which is optimised for general-purpose CPUs to ensure that transactions remain decentralised. Monero also features dynamic block sizes, allowing the network to adjust the block size limit according to the volume of transactions, promoting scalability [38].

The Duino Coin blockchain is an innovative platform designed to increase the use of a wide range of devices, including microcontroller devices, single-board computers like Arduino microcontrollers, Raspberry Pi boards, and even old computers [38,41]. This blockchain is open-source, cost-effective, and highly energy-efficient. Duino Coin employs the Duino Coin Unique Consensus Operation-S1 (DUCO-S1) consensus mechanism, which dynamically changes performance based on the computational capabilities of each participating device, using the XXHASH algorithm to run efficiently on IoT devices [38,41]. The platform also uses the “Kolka System” to facilitate low-powered transactions, ensuring smooth operation without unnecessary complications. While Duino Coin operates as a centralised blockchain, it also offers decentralised options for blockchain users. Additionally, data transactions on the Duino Coin network are secured with SHA1 encryption, providing a layer of security within this energy-efficient ecosystem [38,41].

This section assesses the anomalous behaviours of the Duino Coin, Hydrachain, and Monero networks in the event of a DDoS attack.

The CPU is the primary hardware component that blockchains use to process data blocks and related services. IoT devices typically consist of low-power ARM-based CPUs designed for a minimal workload [1]. An increase in CPU core usage of IoT low-powered hardware devices due to DDoS attacks can cause severe consequences, including hardware failure and data corruption. CPU cores are a single-board computer’s primary data processing units that can be easily overloaded [16].

Fig. 4 shows the CPU core utilisation of Hydrachain under DDoS and typical circumstances; (a) shows the CPU core utilisation of Hydrachain under a DDoS attack; (b) shows the CPU core usage of Hydrachain under typical circumstances. As shown in Fig. 4, the CPU core usage of the Hydrachain blockchain network’s victim node has increased compared to the CPU core usage under ordinary operation. On average, Hydrachain blockchain only uses two CPU cores to process block data. However, with a DDoS attack, the CPU core usage of the victim node has also increased. As per the results, during a DDoS attack, all four cores have been used to process blockchain data. Also, the CPU core use of the victim node ranges from 99% to 100%, while the CPU core use of the non-victim node ranges from 0% to 100% .

Figure 4: CPU core usage of hydrachain. (a) Under DDoS. (b) Typical circumstances

Fig. 5 shows the CPU core utilisation of the Monero blockchain node under a DDoS attack and typical circumstances; (a) shows the CPU core use of Monero under a DDoS attack; (b) shows the CPU core use of Monero under typical circumstances. As the results indicate, the CPU core utilisation of the victim node has increased compared to the CPU core utilisation of a non-victim Monero blockchain node. The CPU core use of a Monero blockchain node under typical circumstances ranges from 95% to 100%. However, the CPU core utilisation of the victim node ranges from 98% to 100%. This is a 3% increment. This shows us that Denial-of-Service attacks can increase the CPU core utilisation.

Figure 5: CPU core usage of Monero. (a) Under DDoS. (b) Typical circumstances

Fig. 6 indicates the CPU core utilisation of the Duino Coin blockchain node under a DDoS attack and typical circumstances; (a) shows the CPU core use of Duino Coin under a DDoS attack; (b) shows the CPU core use of Duino Coin under typical circumstances. Fig. 6 illustrates the CPU core utilisation of a Duino Coin node under a DDoS attack and typical circumstances. The results show that the CPU core utilisation of the victim node that processes the Duino Coin blockchain application varies from 99%–100%. However, the CPU core usage of a Duino Coin node under typical circumstances ranges from 20% to 100%. This indicates the CPU core usage of a Duino Coin node can be impacted significantly by DDoS attacks [42].

Figure 6: CPU core usage of Duino coin. (a) Under DDoS (b) Typical circumstances

The experimental results indicate that DDoS attacks can increase the CPU core usage of victim blockchain nodes, as these nodes have very limited processing power. One possible reason for increasing the CPU core usage is the requirement of the hash function to secure the blocks and blockchain network. Another possible cause is the longer batch time out to fill the “blockchain” [42]. Also, blockchains typically consume high processing power to process blocks and blockchain services, including encryption. IoT devices and networks run 24/7, and the excessive use of CPU cores may potentially cause the hardware devices to fail, which can potentially cause network hash rate changes [43].

This section analyses the blockchain network hash rate changes in a DDoS attack. The hash rate is the measure of the computational power used in a blockchain network. The hash rate is used to determine how many hashes can be generated from the blockchain network per second [44]. The hash rate can vary based on the CPU processing power, and overloading the CPU can decrease the typical hash rate, which is used to encrypt data blocks. Fig. 7 displays the hash rate variability of each node in the Hydrachain blockchain network nodes, which also include a victim blockchain node, node 10.

Figure 7: Node hash rates for Hydrachain

Under normal circumstances, the hash rate of the Hydrachain network ranges between 300 and 350 hashes per second. However, the hash rate of the victim node is significantly lower, with the hashes ranging between 30 and 50 hashes per second. Also, the mean hash rate of the non-victim blockchain nodes ranges from 322.9 hashes per second to 326.75 hashes per second, while the victim node has a mean hash rate of 32.2 hashes per second. This shows a significant difference in hash rate between the non-victim nodes and the victim node.

Fig. 8 shows the hash rate variability of each blockchain node in the Monero network nodes that also include a victim node, which is node 10. As Fig. 8 indicates, the hash rate of the victim node ranges between 60 and 80 hashes per second, while the non-victim nodes have a hash rate between 350 and 500 hashes per second. Meanwhile, the victim node has a mean hash rate of 70.5 hashes per second, while other nodes have a mean hash rate of 419.1 to 443.45 hashes per second. Fig. 9 displays the hash rate variability of each blockchain node in the Duino Coin blockchain network nodes that also include a victim node, which is node 10.

Figure 8: Node hash rates for Monero

Figure 9: Node hash rates for Duino Coin

Fig. 9 indicates the hash rate of the victim node has a hash rate ranges between 30 and 50 hashes per second, while the other nodes have a variability between 400 and 600 hashes per second. The mean hash rate of the victim node is 26.4 hashes per second, while the non-victim nodes have a mean hash rate of 476.25 to 504.95 hashes per second.

Considering the overall results, it is evident that the hash rate can be impacted by DDoS attacks, potentially compromising the encryption of block nodes. The CPU overloading can also be a prime factor that indicates a significant variability of the hash rate regardless of the blockchain network [45]. While normal nodes processed a hash rate over 300, all the victim nodes recorded under 90 hashes per second, which is a significant anomalous behaviour in an instance of DDoS. A low hash rate can result in insufficient encryption of data blocks, which may compromise the security of the blockchain network. Additionally, it can increase the network’s batch timeout, leading to delays in processing transactions [45].

This section analyses the blockchain network batch time out by using the same blockchain IoT network prototype under a DDoS attack. Batch time out is a fallback mechanism if the blockchain is not filled with blocks in a specific time duration [46]. This value represents the upper bounds for how long it takes to fill the blockchain with blocks to be cut out. Batch time-out can be changed due to the batch size of the blockchain network. The increment of batch time out may cause unnecessary network latency, which can cause severe consequences, including data block loss [46].

In an IoT network, data needs to be transmitted without unnecessary delay and any bottlenecks. Batch time-out determines the timestamp value, and if the blockchain network uses a higher batch time-out value, security can be compromised [47]. As blockchain applications typically require higher processing power, it is critical to use batch time out. However, these experiments show that DDoS can impact batch time-out. Fig. 10 shows the batch time out of each blockchain network.

Figure 10: Batch time out of blockchain networks

The experimental results of Fig. 10 indicate that the batch time out of all blockchain networks is significantly increased during DDoS attacks. The BTO of the Hydrachain blockchain network increased from 6 to 32 ms, and the BTO of the Monero network went from 6 to 37 ms. Also, Fig. 10 indicates that the BTO of the Duino Coin blockchain network increased from 4 to 35 ms.

Table 2 shows the batch time-out data sample of each blockchain network under typical circumstances and DDoS attacks. As Table 2 indicates, the batch time out of the Hydrachain blockchain network has increased by 17.8%, while the batch time out of the Monero network has increased by 14%. Also, the batch time out of the Duino Coin network increased by 13.2% during the DDoS attack. This shows that blockchain networks can be flooded by DDoS attacks, creating high BTO and block latency [1]. Blockchain networks typically require sufficient processing power to process data blocks, whereas IoT devices are generally limited [9]. DDoS attacks can lead to resource exhaustion, causing them to extend the BTO before releasing the next set of blocks [1]. This, in turn, can result in an increased block latency.

The block latency variability of each blockchain network is analysed in the context of a DDoS attack, where block delivery can be significantly increased. Blockchain networks have a time frame to deliver blocks from the source to the destination [48]. If the processing power requirement and BTO of blockchain nodes are high, the block latency can be increased, which can cause a block loss [48]. The increment of block latency can potentially lead to a reduction in the quality of service (QoS), which can critically impact businesses [48]. Fig. 11 shows the block latency of each blockchain network under normal instances and DDoS attacks.

Figure 11: Block latency of each blockchain network

As Fig. 11 indicates, the block latency of Duino Coin, Monero and Hydrachain networks ranges between 200 and 400 ms under typical circumstances. However, the results show that the block latency of the Hydrachain network ranges between 2000 and 4000 ms, which is significantly increased. Also, the block latency of the Monero network ranges between 2500 and 4000 ms, while the block latency of the Duino Coin network ranges between 3000 and 4500 ms. As per the results, it can be emphasised that block latency can be influenced by DDoS attacks, causing unnecessary delay and potentially leading to a loss of sensitive information [49]. The results demonstrate that blockchain networks can be compromised by DDoS attacks, resulting in high latency of block transmission, which is a significant contribution of this paper. IoT networks typically use wireless mediums for data communication, and block latency is a prime factor that can significantly reduce the QoS of the IoT network, causing business critical damages [49].

This study demonstrates that blockchains are vulnerable to DDoS attacks, and several anomalous behaviours can be observed in the event of a DDoS threat. Although blockchain technology is identified as a robust security solution for protecting IoT devices and networks, it can be impacted by DDoS [1,16]. Most existing research is conceptual and tested only in simulation environments, not real test systems [49]. Additionally, current commercially available blockchains are designed for devices with greater processing power and are typically not compatible with low-powered IoT devices. Given the complexity of modern DDoS attacks, threat mitigation presents a significant challenge [50]. DDoS attack mitigation is an active research area, and many solutions exist. However, due to recent DDoS attacks on Australian critical businesses and financial sector institutions, the Australian government recognised blockchain as a suitable research area to mitigate future cyber-attacks [51].

In recent years, attackers have frequently targeted blockchain networks using DDoS attacks, necessitating a deeper understanding of blockchain-specific behaviours during a DDoS attack [1]. These include unusual rises in hardware CPU usage, anomalous hash rates, batch timeouts, and unusual block latencies, which can inform strategies to mitigate future DDoS threats. Blockchains typically require significant computational overhead, and DDoS attacks increase the complexity, affecting the performance of IoT networks [52]. To address these challenges, strategies like data aggregation, lightweight blockchain solutions, and model optimisation can enhance efficiency and responsiveness in IoT systems leveraging blockchain technology. The integration of blockchain technology in IoT sensor networks also presents unique challenges regarding the interpretability of recommendations derived from IoT network systems.

Data acquisition and preprocessing of IoT sensors continuously collect data and transmit data in different domains that may critically impact low-powered IoT networks under DDoS threats [16]. Although the decentralised and immutable nature of blockchain provides a transparent audit trail for data used in decision-making, this work provides real test results that blockchains require DDoS mitigation techniques by examining commercially available blockchains [51]. However, by incorporating interpretability strategies, this research aims to strengthen the security of low-powered IoT sensor networks, ultimately fostering trust in the recommendations made. This enhances user engagement and maximises the utility of the IoT infrastructure and the blockchain’s integrity.

6 Conclusion and Future Research

DDoS attacks have led to considerable losses, computationally, financially, and reputationally, for businesses worldwide due to the denial of services [52]. As DDoS attack threat mitigation and prevention is an active research area, businesses are investing significant resources to protect their cyber-physical systems, including IoT networks [16]. The fusion of IoT and blockchain technologies can address many of the security concerns inherent to IoT networks [52]. However, as IoT and blockchain technologies are emerging, they require substantial research attention. Despite blockchain’s promising features, such as cryptography, digital signatures, hash functions, and decentralisation, blockchain-based IoT networks remain vulnerable to DDoS attacks. Potential anomalous behaviours that manifest as a consequence of a DDoS attack have been evaluated, which can inform strategies to identify and counteract future blockchain attacks [53].

A test network was developed using three blockchain applications and low-powered IoT devices to collect data on CPU core usage, hash rate, batch timeout, and block latency. Significant variations in these metrics were observed, indicating the profound impact DDoS attacks can have on blockchain networks. The experiments demonstrated that CPU core usage could spike to 100% on all cores during a DDoS attack, potentially causing hardware failure and decreasing the hash rate to as low as 30 hashes per second, compared to normal rates of 300–500 hashes per second. Additionally, batch timeouts of victim networks could reach as high as 37 ms, compared to a typical timeout of 4 ms. Block latency could also increase to 4.5 ms under a DDoS attack, whereas it typically ranges between 200–400 ms under normal conditions.

Cross-validation techniques were implemented to ensure the robustness of these findings. Data was split into subsets to test the model’s performance across different conditions, thus ensuring the reliability and stability of the model across varied environmental variables such as temperature fluctuations, energy consumption, bandwidth, and transaction rates [1]. Future research will aim to extend the model’s applicability by incorporating independent external IoT sensor datasets. This approach will validate the model’s efficacy in a broader range of real-world conditions and network configurations, enhancing its practical utility in diverse IoT environments [54].

Building on these findings, future research should also explore the integration of other low-powered IoT hardware devices such as ESP32, STM32, Raspberry Pi Zero, Mango Pi Zero, and Arduino Yun to evaluate processing capabilities and identify challenges [36]. Furthermore, the adoption of various wireless technologies, including Bluetooth, LoRa, cellular networks, and ZigBee, represents another vital research avenue. Additionally, emerging fields such as cloud computing and quantum computing hold promise as potential solutions to mitigate DDoS attacks on blockchain networks [1].

In conclusion, continuously evaluating security vulnerabilities in blockchain-based IoT networks is crucial. This study provides a foundational analysis that contributes valuable insights to the field and sets the stage for further investigations to enhance the robustness and efficacy of blockchain technologies in combatting cybersecurity threats.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the support by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (Grant number IMSIU-RP23017).

Funding Statement: This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (Grant number IMSIU-RP23017).

Author Contributions: Conceptualisation, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, Mohsin Murtaza, Chi-Tsun Cheng, and Bader M. Albahlal; methodology, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, Mohsin Murtaza, and Chi-Tsun Cheng; software, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige; validation, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, Mohsin Murtaza, Chi-Tsun Cheng, and Bader M. Albahlal; formal analysis, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, and Mohsin Murtaza; resources, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, and Bader M. Albahlal; writing original draft preparation, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, and Mohsin Murtaza; writing review and editing, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, Mohsin Murtaza, Chi-Tsun Cheng, Cheng-Chi Lee, and Bader M. Albahlal; visualisation, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, and Mohsin Murtaza; project administration, Kithmini Godewatte Arachchige, Mohsin Murtaza, Chi-Tsun Cheng, Cheng-Chi Lee, and Bader M. Albahlal. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All datasets generated during the study are available upon request from the primary author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. K. G. Arachchige, P. Branch, and J. But, “An analysis of blockchain-based IoT sensor network distributed denial of service attacks,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 10, 2024, Art. no. 3083. doi: 10.3390/s24103083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. N. T. Y. Huan and Z. A. Zukarnain, “A survey on addressing IoT security issues by embedding blockchain technology solutions: Review, attacks, current trends, and applications,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 69765–69782, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3378592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. A. Nazir et al., “Collaborative threat intelligence: Enhancing IoT security through blockchain and machine learning integration,” J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci., vol. 36, no. 2, 2024, Art. no. 101903. doi: 10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.101939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. W. Villegas-Ch, J. García-Ortiz, and S. Sánchez-Viteri, “Toward intelligent monitoring in IoT: AI applications for real-time analysis and prediction,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 40368–40386, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3376707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. D. Commey, B. Mai, S. G. Hounsinou, and G. V. Crosby, “Securing blockchain-based IoT systems: A review,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 98856–98881, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3428490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. M. Murtaza, C. -T. Cheng, M. Fard, and J. zaleznikow, “Transforming driver education: A comparative analysis of LLM-augmented training and conventional instruction for autonomous security technologies,” Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ., vol. 18, no. 3, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s40593-024-00407-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. The Department of Industry, Energy and Resources (DISER“The national blockchain roadmap,” 2020. Accessed: Jul. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/trade-and-investment/business-envoy-april-2021-digital-trade-edition/australias-blockchain-roadmap [Google Scholar]

8. A. Rejeb et al., “Unleashing the power of internet of things and blockchain: A comprehensive analysis and future directions,” Intern. Thin. Cyber-Phys. Syst., vol. 4, pp. 1–18, 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. T. Zia and A. Zomaya, “Security issues in wireless sensor networks,” in 2006 Int. Conf. Syst. Netw. Commun. (ICSNC’06), Tahiti, French Polynesia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

10. E. Androulaki et al., “Hyperledger fabric,” in presented at the Proc. Thirteenth EuroSys Conf., 2018. [Google Scholar]

11. A. Harshavardhan, T. Vijayakumar, and S. Mugunthan, “Blockchain technology in cloud computing to overcome security vulnerabilities,” in 2018 2nd Int. Conf. I-SMAC (IoT in Soc., Mob., Analyt. Cloud)(I-SMAC) I-SMAC (IoT in Soc., Mob., Analyt. Cloud)(I-SMACPalladam, India, IEEE, 2018, pp. 408–414. [Google Scholar]

12. S. Mori, “Secure caching scheme by using blockchain for information-centric network-based wireless sensor networks,” J. Signal Process., vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 97–108, 2018. doi: 10.2299/jsp.22.97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. M. H. Khalid, M. Murtaza, A. Saeed, and M. Raza, “Proposing 2-tier architecture for permission-ed and permission-less blockchain consensus algorithms based on voting system,” in 2020 5th Int. Conf. Innov. Technol. Intell. Syst. Indust. Appl. (CITISIA), Sydney, Australia, 2020, pp. 1–6. doi: 10.1109/CITISIA50690.2020.9371832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. A. Panarello, N. Tapas, G. Merlino, F. Longo, and A. Puliafito, “Blockchain and IoT integration: A systematic survey,” Sensors, vol. 18, no. 8, Aug. 6, 2018, Art. no. 2575. doi: 10.3390/s18082575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. A. Reyna, C. Martín, J. Chen, E. Soler, and M. Díaz, “On blockchain and its integration with IoT. Challenges and opportunities,” Future Gen. Comput. Syst., vol. 88, no. 3, pp. 173–190, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2018.05.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. P. B. K. Godawatte and J. But, “Use of blockchain in health sensor networks to secure information integrity and accountability,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 210, no. 2, pp. 124–132, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2022.10.128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. M. Belotti, N. Bozic, G. Pujolle, and S. Secci, “A vademecum on blockchain technologies: When, which, and how,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 3796–3838, 2019. doi: 10.1109/COMST.2019.2928178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. M. A. Ferrag et al., “Revolutionizing cyber threat detection with large language models: A privacy-preserving BERT-based lightweight model for IoT/IIoT devices,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 23733–23750, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3363469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. D. Dasgupta, J. M. Shrein, and K. D. Gupta, “A survey of blockchain from security perspective,” J. Bank. Financ. Technol., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s42786-018-00002-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. M. H. Khalid, M. Murtaza, and M. Habbal, “Study of security and privacy issues in internet of things,” in 2020 5th Int. Conf. Innov. Technol. Intell. Syst. Indus. Appl. (CITISIA), Sydney, Australia, 2020, pp. 1–5. doi: 10.1109/CITISIA50690.2020.9371828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. P. W. Eklund and R. Beck, “Factors that impact blockchain scalability,” presented at the Proc. 11th Int. Conf. Manag. Digital EcoSystems, 2019. [Google Scholar]

22. A. Aguru and S. Erukala, “OTI-IoT: A blockchain-based operational threat intelligence framework for multi-vector DDoS attacks,” ACM Trans. Internet Technol., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 1–31, 2024. doi: 10.1145/3664287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. M. A. Khan and K. Salah, “IoT security: Review, blockchain solutions, and open challenges,” Future Gener. Comput. Syst., vol. 82, no. 15, pp. 395–411, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2017.11.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. S. Mathur, A. Kalla, G. Gür, M. K. Bohra, and M. Liyanage, “A survey on role of blockchain for IoT: Applications and technical aspects,” Comput. Netw., vol. 227, 2023, Art. no.109726. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2023.109726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. R. Chaganti, B. Bhushan, and V. Ravi, “The role of blockchain in DDoS attacks mitigation: Techniques, open challenges and future directions,” 2022. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2202.03617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. R. Chaganti et al., “A comprehensive review of denial of service attacks in blockchain ecosystem and open challenges,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 96538–96555, 2022. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3205019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Z. A. Khan and A. S. Namin, “A survey of DDoS attack detection techniques for IoT systems using blockchain technology,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 23, 2022, Art. no. 3892. doi: 10.3390/electronics11233892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. A. Ayub Khan, A. A. Laghari, Z. A. Shaikh, Z. Dacko-Pikiewicz, and S. Kot, “Internet of things (IoT) security with blockchain technology: A state-of-the-art review,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 122679–122695, 2022. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3223370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. S. T. Stefan Unger and P. Kieseberg, “The risks of the blockchain a review on current vulnerabilities and attacks,” J. Intern. Serv. Inform. Secur., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 110–127, 2020. doi: 10.22667/JISIS.2020.08.31.110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. A. K. S. Kevin Jonathan, “Security issues and vulnerabilities on a blockchainsystem: A review,” in 2019 Int. Sem. Res. Inform. Technol. Intell. Syst. (ISRITI), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2019, pp. 228–232. doi: 10.1109/ISRITI48646.2019.9034659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Z. Shah, I. Ullah, H. Li, A. Levula, and K. Khurshid, “Blockchain based solutions to mitigate distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks in the internet of things (IoTA survey,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 3, Jan. 31, 2022, Art. no. 1094. doi: 10.3390/s22031094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. S. Wani, M. Imthiyas, H. Almohamedh, K. M. Alhamed, S. Almotairi and Y. Gulzar, “Distributed denial of service (DDoS) mitigation using blockchain—A comprehensive insight,” Symmetry, vol. 13, no. 2, 2021, Art. no. 227. doi: 10.3390/sym13020227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. S. Selvarajan, A. Shankar, M. Uddin, A. S. Alqahtani, T. Al-Shehari and W. Viriyasitavat, “A smart decentralized identifiable distributed ledger technology-based blockchain (DIDLT-BC) model for cloud-IoT security,” Expert. Syst., vol. 127, 2024, Art. no. e13544. doi: 10.1111/exsy.13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. H. Manoharan, A. Manoharan, S. Selvarajan, and K. Venkatachalam, “Implementation of internet of things with blockchain using machine learning algorithm,” in Handbook of Research on Blockchain Technology and the Digitalization of the Supply Chain, Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2023, pp. 399–430. doi: 10.4018/978-1-6684-7455-6.ch019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. S. S. Kushwaha, S. Joshi, D. Singh, M. Kaur, and H. -N. Lee, “Systematic review of security vulnerabilities in ethereum blockchain smart contract,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 6605–6621, 2022. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3140091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. B. Alhijawi, S. Almajali, H. Elgala, H. Bany Salameh, and M. Ayyash, “A survey on DoS/DDoS mitigation techniques in SDNs: Classification, comparison, solutions, testing tools and datasets,” Comput. Electr. Eng., vol. 99, 2022, Art. no. 107706. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. K. Godawatte, P. Branch, and J. But, “Blockchain health sensor network performance analysis on low powered microcontroller devices,” in 2023 IEEE Int. Syst. Conf. (SysCon), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023, pp. 1–8. doi: 10.1109/SysCon53073.2023.10131087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Raspberry Pi Ltd., “Raspberry Pi hardware,” 2016. Accessed: Aug. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.raspberrypi.com/documentation/computers/raspberry-pi.html [Google Scholar]

39. K. G. Arachchige, P. Branch, and J. But, “Evaluation of blockchain networks’ scalability limitations in low-powered internet of things (IoT) sensor networks,” Fut. Intern., vol. 15, no. 9, 2023, Art. no. 317. doi: 10.3390/fi15090317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Orange pi-orangepi, “Orange pi zero 2W–Small, practical, powerful,” 2014. Accessed: Aug. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.orangepi.org/html/hardWare/computer-and-Microcontrollers/details/Orange-Pi-Zero-2W.html [Google Scholar]