Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

VTAN: A Novel Video Transformer Attention-Based Network for Dynamic Sign Language Recognition

1 School of Mathematics and Computer Science, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330031, China

2 Institute of Metaverse, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330031, China

3 Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Virtual Reality, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330031, China

* Corresponding Author: Weidong Min. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 2793-2812. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.057456

Received 18 August 2024; Accepted 22 November 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

Dynamic sign language recognition holds significant importance, particularly with the application of deep learning to address its complexity. However, existing methods face several challenges. Firstly, recognizing dynamic sign language requires identifying keyframes that best represent the signs, and missing these keyframes reduces accuracy. Secondly, some methods do not focus enough on hand regions, which are small within the overall frame, leading to information loss. To address these challenges, we propose a novel Video Transformer Attention-based Network (VTAN) for dynamic sign language recognition. Our approach prioritizes informative frames and hand regions effectively. To tackle the first issue, we designed a keyframe extraction module enhanced by a convolutional autoencoder, which focuses on selecting information-rich frames and eliminating redundant ones from the video sequences. For the second issue, we developed a soft attention-based transformer module that emphasizes extracting features from hand regions, ensuring that the network pays more attention to hand information within sequences. This dual-focus approach improves effective dynamic sign language recognition by addressing the key challenges of identifying critical frames and emphasizing hand regions. Experimental results on two public benchmark datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of our network, outperforming most of the typical methods in sign language recognition tasks.Keywords

Sign language recognition technology bridges the communication gap between deaf and mute individuals and the general population [1]. This technology converts sign language into text or speech [2], enabling novel human-computer interactions [3]. This technology has made significant progress in areas such as sign language translation [4], sign language tutoring [5], and special education [6], facilitating smoother communication between deaf individuals and others.

Initial sign language recognition algorithms focused on hand shapes and limb trajectories using sensor-based motion capture and traditional analytical methods [7,8]. The advent of deep learning [9–11] has popularized computer vision-based approaches [12,13], which better address the complexities of dynamic sign recognition. Despite these advancements, current methods still face challenges in achieving both high accuracy and fast computation, especially when dealing with the intricate nature of dynamic sign language.

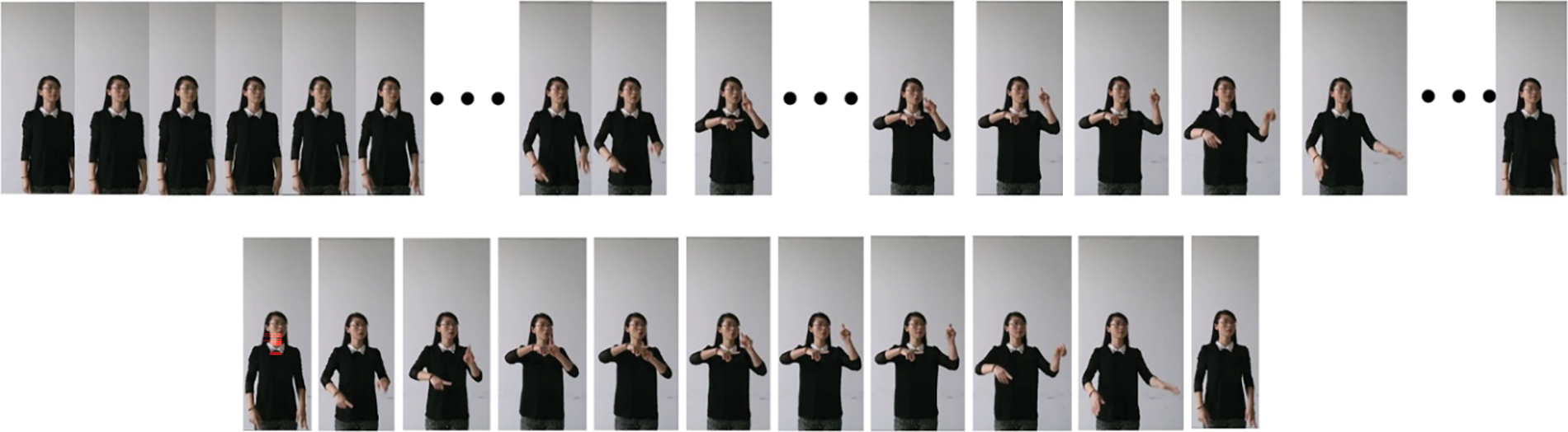

One primary issue with existing approaches is that they often fail to highlight the critical features needed for accurate sign language recognition when directly processing entire video frames. Fig. 1 demonstrates the presence of redundant frames prior to effective sign language recognition. Directly inputting the entire video sequence into the network results in unnecessary interference and redundancy. In sign language, the hand is the most critical element for conveying information. However, within the overall frame, the hand often occupies a small part of the frame, leading to insufficient attention from the network and resulting in recognition errors. Extraneous frame information impedes inference speed and computational efficiency.

Figure 1: An example of the redundant frames in the video on the SLR500 dataset

To address these limitations, we propose a Video Transformer Attention-based Network (VTAN): A Novel Video Transformer Attention-based Network for Dynamic Sign Language Recognition. Our network optimizes feature extraction by prioritizing informative frames and hand regions, ensuring efficient capture of critical features. This is accomplished through two key modules: the visual feature aggregation for the keyframe extraction module and the spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement module based on the transformer. The keyframe extraction module aggregates visual features by selecting information-rich frames while filtering redundant video content. This process not only enhances the relevance of the input data but also significantly improves computational efficiency. The spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement module, on the other hand, is designed to emphasize the extraction of features from the hand regions, ensuring that the network allocates sufficient attention to these areas, which are essential for accurate sign language recognition.

Our approach is validated through experiments on two benchmark datasets: one for Turkish Sign Language and one for Chinese Sign Language. VTAN demonstrates improved performance compared to existing methods, highlighting its effectiveness in recognizing dynamic sign language. Although the improvement in accuracy is modest, the results underscore the potential of our network as a robust solution for this challenging task.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) We propose VTAN, a novel Video Transformer Attention-based Network for dynamic sign language recognition. VTAN effectively addresses key challenges by enhancing focus on informative frames and hand regions, generating more accurate recognition results.

(2) The Visual Feature Aggregation Module is introduced to tackle the issue of redundant frames by selecting only the most informative frames, thereby improving data relevance and computational efficiency for dynamic sign language videos.

(3) The Spatio-temporal Hand Feature Enhancement Module is designed to focus specifically on hand regions, which are crucial for sign language. This module ensures that the network extracts meaningful features from these regions, improving recognition accuracy by emphasizing the most critical elements of sign language.

The importance of dynamic sign language recognition has been widely recognized. Most of the early work on isolated word recognition in sign language relied on traditional model methods. Classic methodologies often revolved around handcrafted features and conventional machine learning algorithms such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) [14–16] and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [17,18]. However, these approaches, while effective to a certain extent, struggled to capture the intricate nuances and dynamic variations inherent in sign language gestures, and were limited in scalability and adaptability to different sign languages and signer variations. With advancements in deep learning, traditional models gradually gave way to more sophisticated, data-driven approaches.

Building upon the principles of traditional methods, Neural network architectures, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [19] and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [20], demonstrated remarkable success in extracting spatial and temporal patterns from sign language videos and sequences. CNNs have demonstrated remarkable success in extracting spatial patterns from sign language images, facilitating tasks such as hand shape and motion recognition. For instance, Wadhawan et al. [21] proposed a robust modeling approach for Indian Sign Language (ISL) recognition using deep learning-based CNNs, achieving high training accuracy on colored and grayscale images and surpassing previous methodologies by encompassing a broader spectrum of hand signs. Similarly, Han et al. [22] utilized an R(2+1)D model with spatial-temporal-channel attention, while Sharma et al. [23] proposed a 3D Convolutional Neural Network (ASL-3DCNN), both aiming to effectively model spatio-temporal dependencies in sign language sequences. Additionally, Liu et al. [24] introduce a novel wearable sign language recognition system, integrating a CNN with stretchable strain sensors and inertial measurement units to capture hand postures and movement trajectories. RNNs and variants like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have played a crucial role in modeling temporal dependencies in sign language sequences, enhancing understanding of sequential gestures over time. For instance, Zuo et al. [25] proposed auxiliary tasks to enhance continuous sign language recognition (CSLR) models by improving spatial attention consistency and feature representation. Moreover, recent studies [26] have leveraged Bidirectional LSTMs (Bi-LSTMs) for temporal and sequential feature extraction, further advancing the capabilities of sign language recognition systems. In line with this innovation, researchers have explored methods to enhance sign language recognition systems through model fusion. For instance, some studies have investigated novel approaches to weakly supervised learning in the video domain, leveraging sequence constraints within each independent stream and combining them with multi-stream Hidden Markov Models (HMM). By embedding powerful CNN-LSTM models in each HMM stream, researchers aim to exploit sequential parallelism for learning sign language, mouth shape, and hand shape classifiers [27]. Abdullahi et al. [28] highlighted the importance of optimizing spatio-temporal feature selection to improve model performance in dynamic sign language recognition, furthering the exploration of feature-based methods. Additionally, recent advances in sign language recognition have introduced hybrid deep learning models, such as the CNNSa-LSTM, which combines CNNs, self-attention mechanisms, and LSTMs to better model the spatial, temporal, and sequential complexities of sign language data [29]. These neural network architectures, with their ability to learn complex patterns and relationships, have significantly advanced the state-of-the-art in sign language recognition.

As sign language recognition has evolved, attention mechanisms have emerged as pivotal for enhancing the interpretability and performance of neural network models. By dynamically weighting the importance of different parts of the input sequence, attention mechanisms enable models to focus on relevant information while filtering out noise and irrelevant details. Transformer-based architectures, equipped with self-attention mechanisms, have become powerful for sign language recognition tasks. Kothadiya et al. [30] introduced a vision transformer approach for recognizing static Indian sign language, utilizing positional embedding patches and a transformer block with self-attention layers and a multilayer perceptron network. Alnabih et al. [31] pioneered the use of Vision Transformers in identifying Arabic sign language letters, surpassing previous CNN-based models with remarkable accuracy, and showcasing its real-world potential. These models excel in capturing long-range dependencies and contextual information, thereby enhancing recognition system accuracy and robustness.

While these mentioned models have made significant strides in sign language recognition, they still face challenges related to redundant frames and insufficient focus on hand regions, leading to information loss and low accuracy. To address these limitations, our proposed Video Transformer Attention-based Network aims to prioritize informative frames and hand regions using a novel approach. By integrating visual feature aggregation for keyframe extraction and spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement modules, VTAN aims to optimize the accuracy of sign language gesture recognition.

3.1 Overview of the Proposed Method

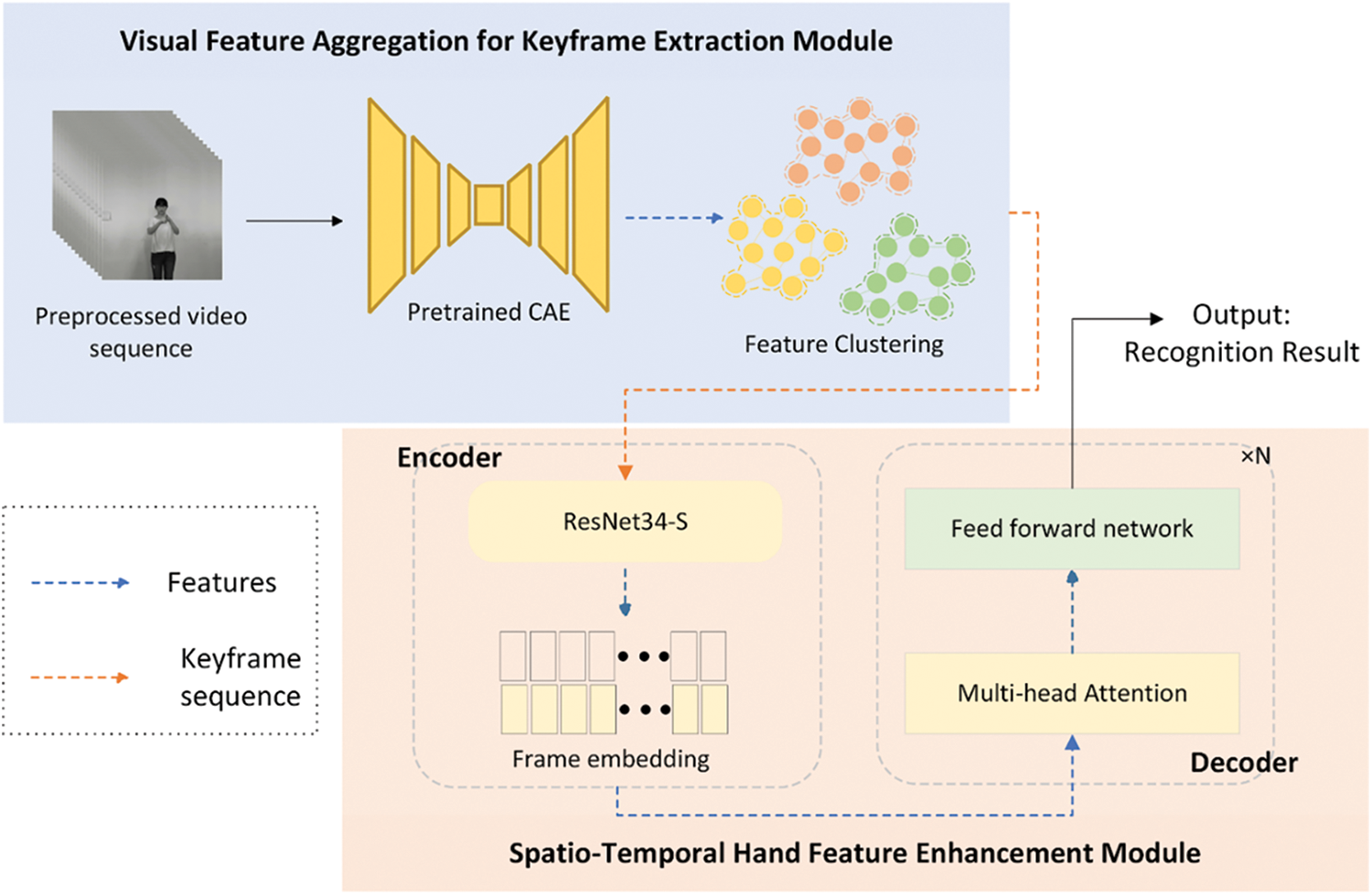

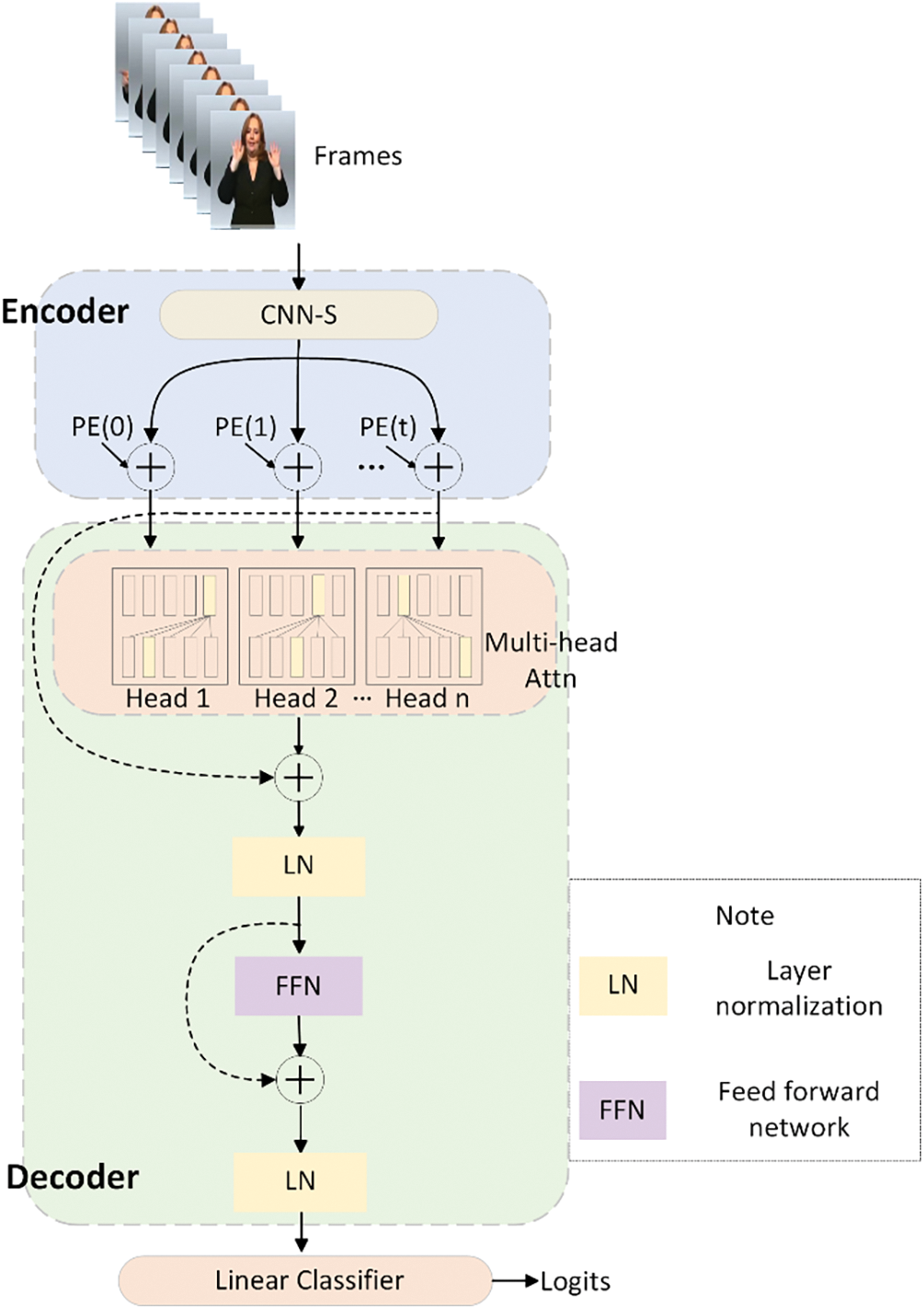

Fig. 2 illustrates the proposed framework’s two main components. Our framework comprises two modules: (1) a visual feature aggregation module for keyframe extraction and (2) a spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement module utilizing soft attention.

Figure 2: Overview of the method

The first component, the visual feature aggregation for keyframe extraction module, is designed to select frames rich in information and eliminate redundant frames from video sequences. The process begins with converting color videos to grayscale, followed by applying convolutional and pooling operations through a pre-trained convolutional autoencoder. A K-means clustering algorithm processes the subsampled two-dimensional feature vectors to generate keyframe sequences.

The transformer-based spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement module optimizes hand region feature extraction. This module processes keyframe sequences from the previous component, performing spatio-temporal feature extraction and classification while prioritizing hand-related information. The process involves passing the keyframe image sequence through an encoder based on a convolutional neural network to obtain frame embeddings via global merging. A decoder with multi-head residual attention blocks analyzes features for dynamic sign language gesture classification.

3.2 Visual Feature Aggregation for Keyframe Extraction

Sign language datasets frequently contain redundant frames with minimal gesture variations. Including these redundant frames in network computations leads to inefficiencies and can reduce recognition accuracy. Keyframe extraction optimizes video analysis by preserving only essential gesture-defining frames. This optimization reduces computational overhead while enhancing system performance through concentrated video representation. Without keyframe extraction, redundant frames can dilute the effectiveness of gesture classification, negatively impacting the accuracy of the system.

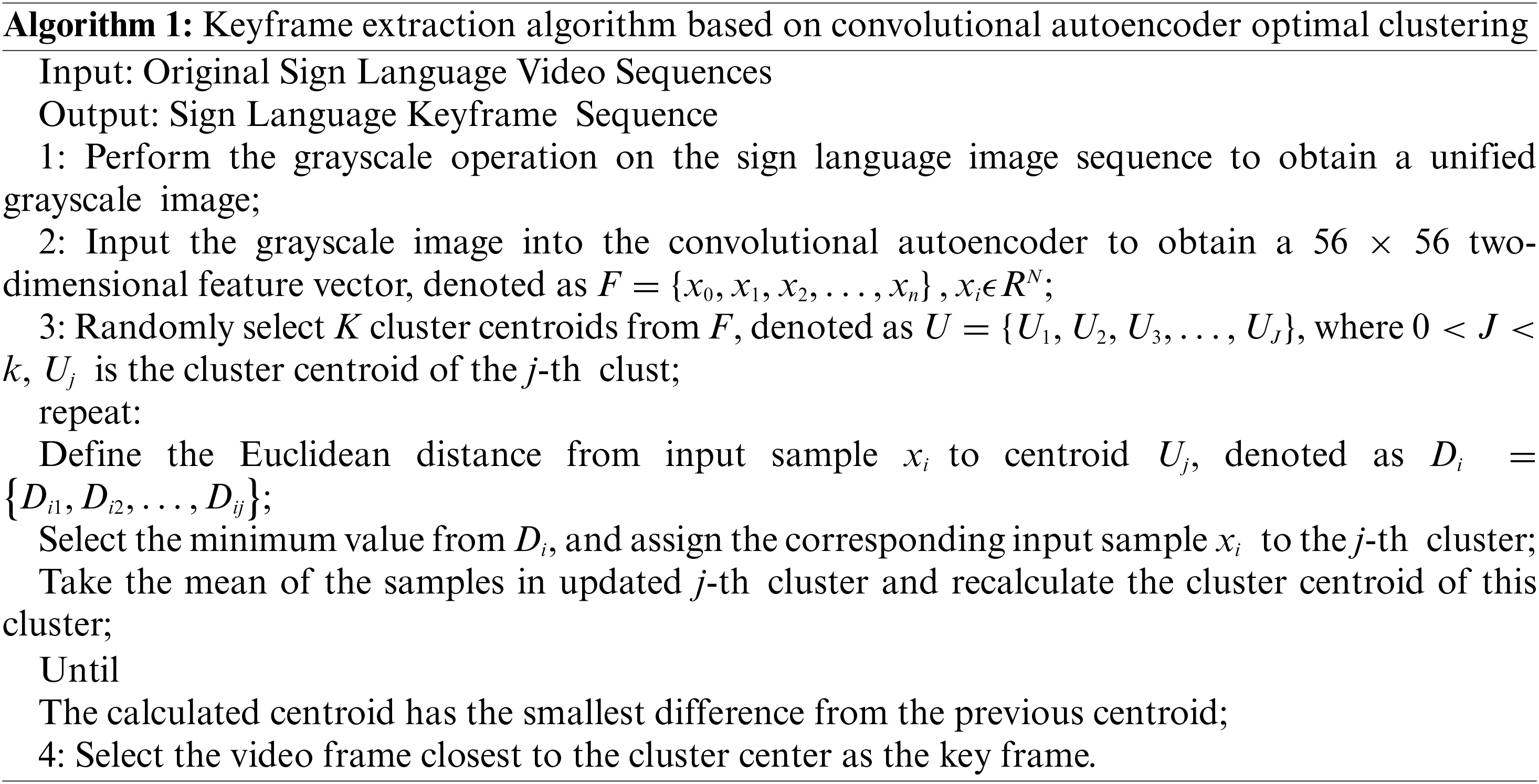

To address this challenge, we propose a novel keyframe extraction algorithm predicated on convolutional autoencoder optimized clustering. Our convolutional autoencoder approach surpasses traditional pixel-level methods by efficiently extracting deep features while minimizing computational overhead and noise. Our method presents distinct advantages over conventional deep learning approaches (CNNs, RNNs) for keyframe extraction. CNN-based approaches often require large amounts of labeled data for effective training, and RNNs can be computationally expensive due to their sequential nature. In contrast, our method utilizes unsupervised learning through convolutional autoencoders and K-means clustering, eliminating the need for labeled datasets and reducing computational complexity. This combination allows for the efficient extraction of representative frames, improving the balance between accuracy and computational cost without overfitting to specific patterns or requiring extensive training resources.

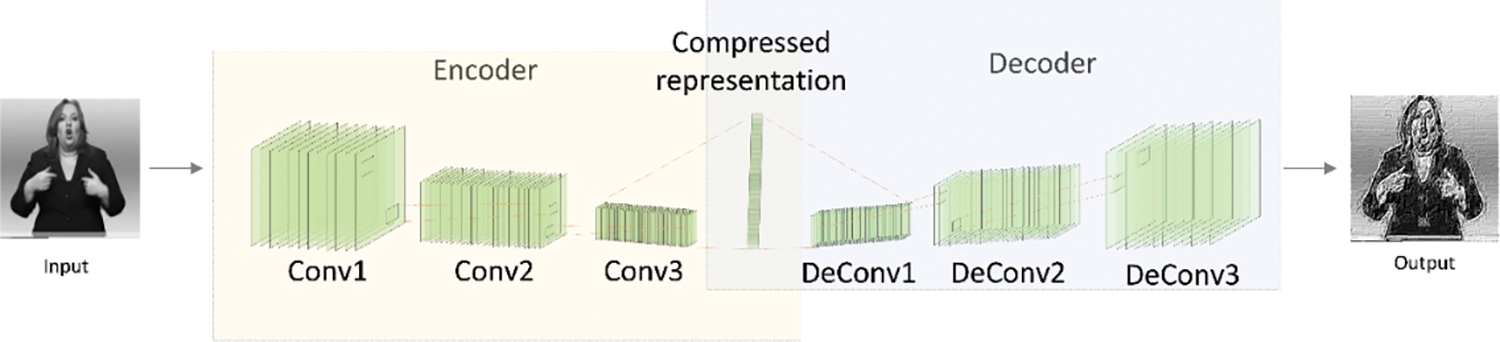

Fig. 3 illustrates the convolutional autoencoder architecture, consisting of encoder and decoder components. The encoder compresses input image sequences into lower-dimensional latent feature representations, while the decoder reconstructs the compressed features, ensuring fidelity to the original input.

Figure 3: The convolutional autoencoder network structure

In our experiments, color images from both the AUTSL_Dataset and SLR500 are resized to

K-means clustering groups similar samples based on distance metrics for efficient keyframe extraction. In our study, the K-means clustering algorithm operates on the

3.3 Spatio-Temporal Hand Feature Enhancement Module

The spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement module (STHE) enhances dynamic sign language gesture recognition accuracy. STHE differs from conventional methods by prioritizing hand-centric feature extraction from preprocessed keyframes, improving isolated sign word recognition. STHE’s attention mechanism dynamically weights hand regions across sequential frames. This selective attention mechanism assigns higher weights to the hand regions, ensuring that the most relevant parts of the gestures are prioritized. As a result, the model can effectively capture subtle hand movements and spatial positions while filtering out less relevant information, such as background noise or non-hand body movements. By concentrating on these hand-centric features, the STHE significantly improves the model’s ability to accurately recognize dynamic sign language gestures.

Fig. 4 shows STHE’s dual-component architecture: a CNN-based encoder for spatial feature extraction and frame embedding, and a multi-block decoder. Each block in the decoder includes a multi-head attention layer and a feed-forward network, with normalization conducted midway and at the end of the decoder. The STHE encoder processes preprocessed keyframes to extract and encode spatial features. Subsequent decoding and analysis employing self-attention facilitate the recognition and classification of sign language gestures.

Figure 4: The spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement module

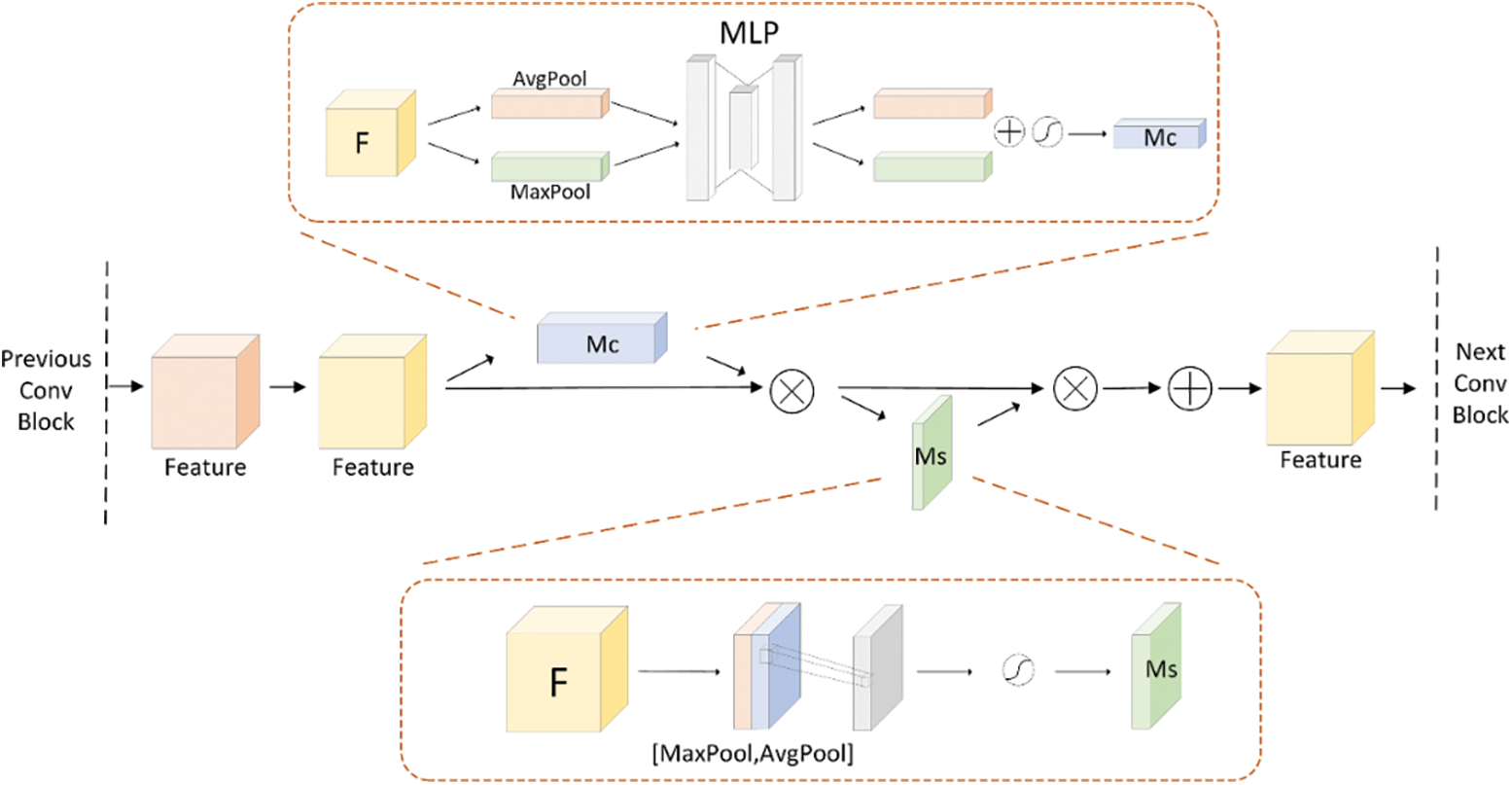

STHE integrates a modified ResNet-34 CNN encoder with soft attention in its ResiBlock structure to enhance channel and spatial feature sensitivity. This enhancement intensifies the model’s focus on hand features while maintaining computational efficiency. The encoder configuration incorporates weighted channel and spatial attention, denoted as Mc and Ms in Fig. 5, respectively.

Figure 5: The improvements of the ResiBlock structure

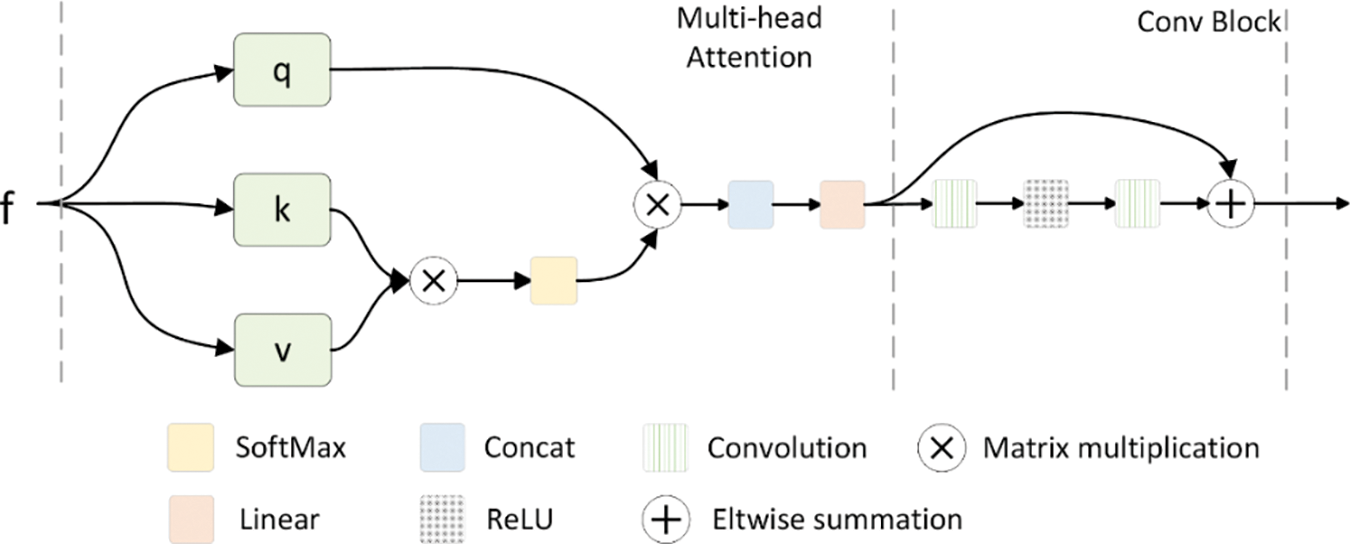

Fig. 6 illustrates the decoder architecture, featuring four multi-head self-attention blocks with residual connections and feedforward networks. Layer normalization is applied mid-process and at the conclusion of the decoder. STHE incorporates sequence ordering through position encoding of feature vectors prior to the decoder’s initial residual multi-head attention layer.

Figure 6: The decoder structure

The multi-head self-attention block adeptly models temporal relationships between video frames through a series of sequential operations. Input feature vectors extracted by the encoder, denoted as X, undergo transformation into queries Q, keys K, and values V through trainable linear transformations

3.4 Interaction between Keyframe Extraction and Spatio-Temporal Feature Enhancement

In the proposed method, the interaction between the keyframe extraction module and the spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement module plays a crucial role in improving model performance. The keyframe extraction module selects representative frames capturing essential hand movements while eliminating redundant data. This frame selection reduces input complexity, providing the enhancement module with concentrated, informative data.

Keyframes are sequentially processed by the enhancement module for detailed spatio-temporal feature extraction. The enhancement module extracts precise temporal dynamics and spatial structures from the selected keyframes. This focused approach enables robust feature learning, enhancing complex gesture recognition performance. Furthermore, keyframe extraction optimizes computational efficiency while maintaining recognition accuracy through reduced data redundancy. The modular interaction achieves dual benefits: improved computational efficiency and enhanced gesture recognition accuracy.

4.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

We conducted experiments using two prominent datasets, the AUTSL dataset [32] and the SLR500 dataset [33], to evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed method. The AUTSL dataset, a publicly available repository, contains a diverse collection of isolated sign language words performed by 43 signers, comprising a total of 38,336 video samples recorded in RGB, depth, and skeleton formats using Microsoft Kinect v2. The RGB and depth data are preprocessed to a resolution of 512 × 512, while the skeleton data provides spatial coordinates of 25 connection points on the signer’s body, aligned with the RGB and depth data. Fig. 7 shows some examples of AUTSL dataset. On the other hand, the SLR500 dataset, established by Huang et al. [33], consists of 25,000 videos of Chinese isolated sign language words recorded in multiple formats, including RGB, depth, and skeleton.

Figure 7: An example of AUTSL dataset

To evaluate the performance of our proposed method, we adopted the accuracy metric, which is widely used in the assessment of dynamic isolated sign language word recognition systems. The accuracy metric, calculated using the formula:

where

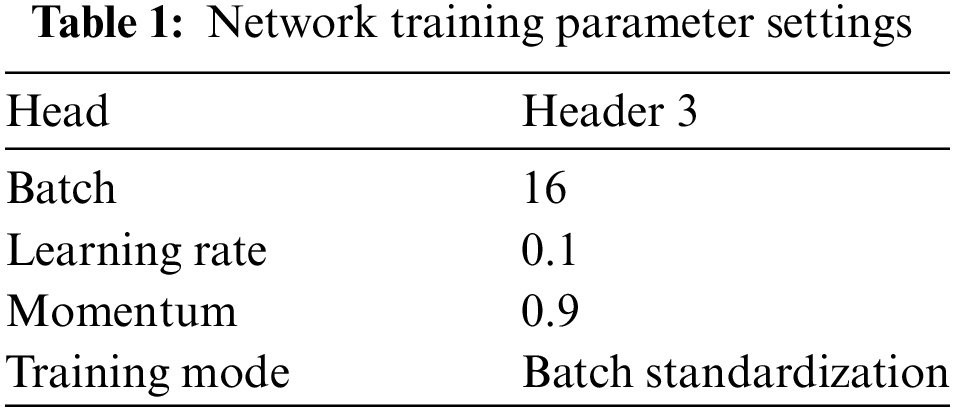

The experiment was carried out on a Linux operating system Ubuntu utilizing the Pytorch framework. The computer system employed in the experiment had an Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-8700CPU @ 3.20 GHz 3.19 GHz processor, 16 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA Quadro P4000 graphics card. The model was trained with a batch size of 16, and the learning rate was initially set to 0.1, with a decay factor of 10 applied every 5 epochs. The Adam optimizer was used to minimize the loss function. We used a 7:3 split of training and validation sets for model evaluation. Early stopping was applied based on the validation loss to avoid overfitting. The network model’s parameter settings used during the training process are presented in Table 1. To further enhance the model’s performance and robustness, we applied several data augmentation techniques during the preprocessing stage. Specifically, all color images from the AUTSL_Dataset and SLR_Dataset were resized to 252 × 252 pixels and converted to grayscale. This transformation not only standardizes the input data but also acts as an augmentation technique by focusing on spatial gesture features and minimizing variations caused by color. Furthermore, additional augmentations such as random cropping, flipping, and rotation were performed on randomly selected images from the SLR_Dataset, increasing the diversity of the training data and improving the model’s generalization ability on unseen data.

4.3 Visual Feature Aggregation for Keyframe Extraction Results and Analysis

This experiment evaluates the visual feature aggregation module’s keyframe extraction effectiveness. The convolutional autoencoder extracts video sequence features for subsequent clustering-based keyframe identification. This method reduces background interference while accelerating algorithm convergence. Fig. 8 compares the original video sequence (top row) with extracted keyframes (bottom row).

Figure 8: Effect of keyframe extraction algorithm on SLR500 dataset

VTAN achieves computational efficiency through its visual feature aggregation module for keyframe extraction. This module carefully selects only the most informative frames from the video sequence, effectively reducing the number of frames processed by the Transformer module. VTAN minimizes computational overhead by reducing input data redundancy. Unlike full-sequence processing models, VTAN’s selective frame analysis improves processing efficiency and resource utilization. As shown in Fig. 8, a video sequence with numerous frames is reduced to 11 keyframes, significantly lowering the amount of data that needs to be processed, while maintaining essential gesture information.

While transformers typically involve significant computational overhead, especially when applied to video data, VTAN addresses this challenge by leveraging keyframe extraction to reduce the number of frames processed. This method ensures that the model focuses on the most critical parts of the video, thereby optimizing computational efficiency. Although there may be trade-offs in processing fewer frames, VTAN is designed to balance accuracy and computational complexity, making it a practical solution for real-world applications where resource constraints are a concern.

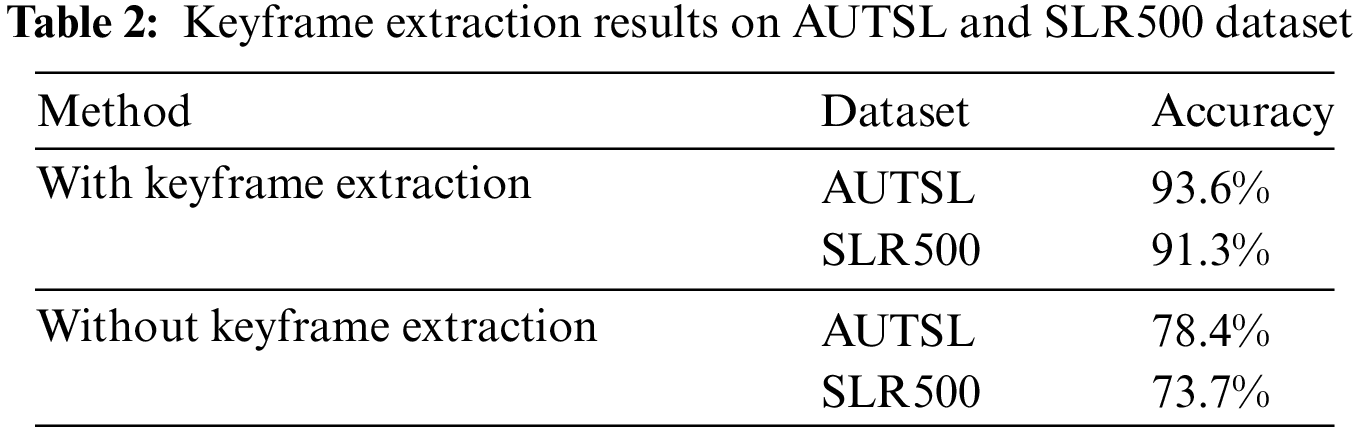

To investigate whether keyframe extraction can enhance the recognition accuracy of the experiment, this study conducted experiments both with and without keyframe extraction module on different datasets. The specific results are presented in Table 2. By integrating the visual feature aggregation for keyframe extraction module, our method increased the recognition accuracy from 78.4% to 93.6% on the AUTSL dataset, representing a substantial improvement of 15.2%. Similarly, on the SLR500 dataset, the accuracy increased from 73.7% to 91.3%, an improvement of 17.6%. These results demonstrate that the keyframe extraction module effectively improves the recognition accuracy of dynamic sign language gestures across diverse datasets. The significant improvement of 15.2% on the AUTSL Dataset and 17.6% on the SLR500 dataset highlights the crucial role of the keyframe extraction module in enhancing the performance of the recognition system. This result underscores the importance of selecting informative frames and eliminating redundant frames in improving the efficiency and accuracy of dynamic sign language recognition.

4.4 Comparison with State-of-the-Arts

We evaluated VTAN against standard methods in dynamic sign language recognition using consistent datasets and metrics. Uniform implementation and evaluation protocols ensured objective comparison across all methods.

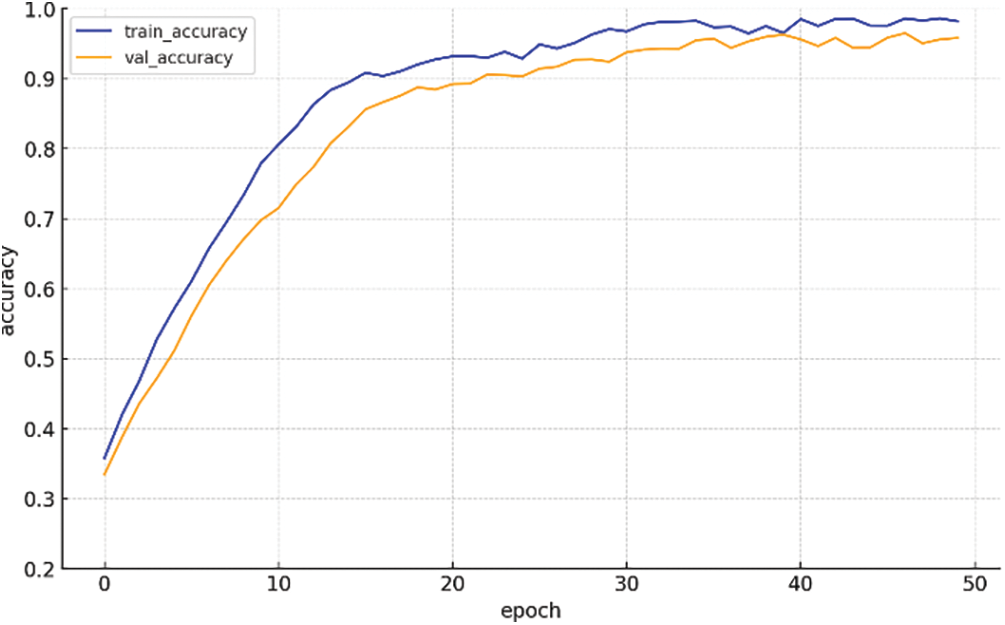

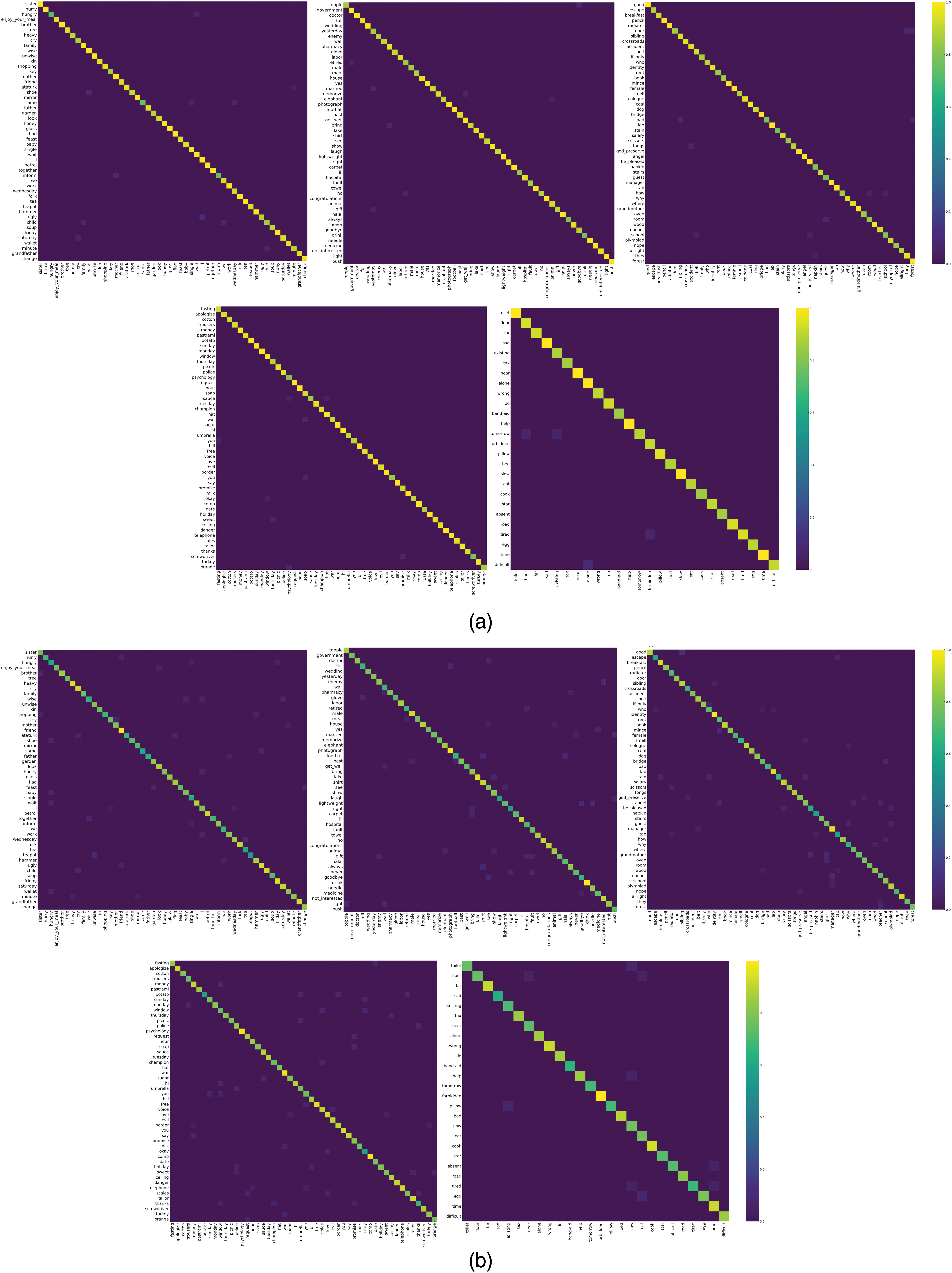

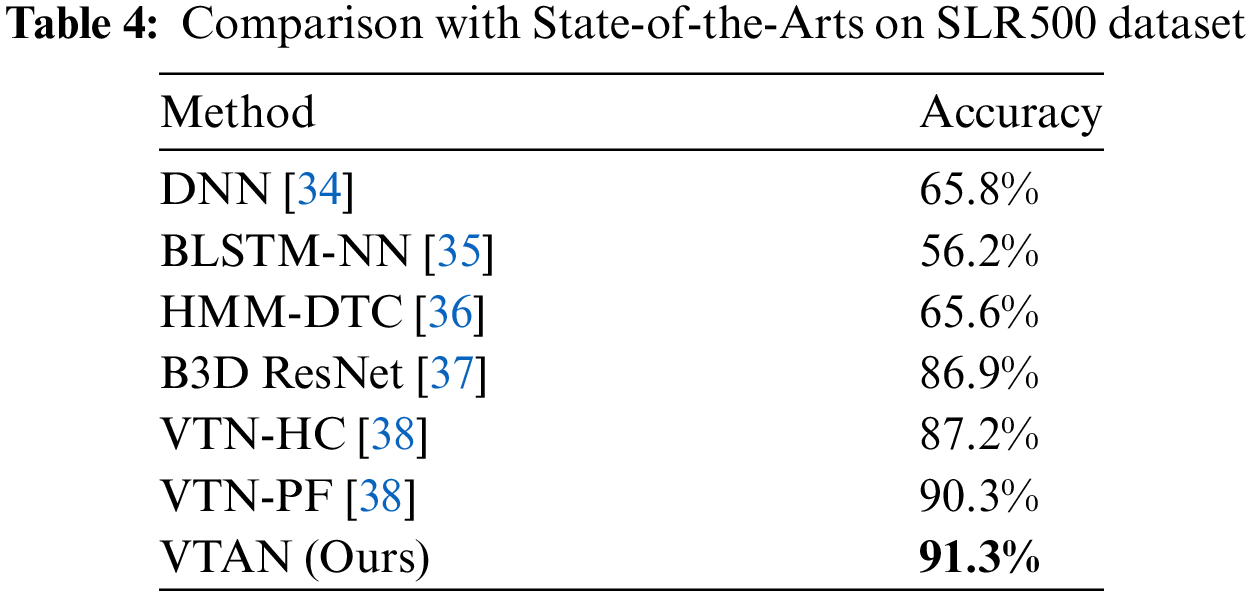

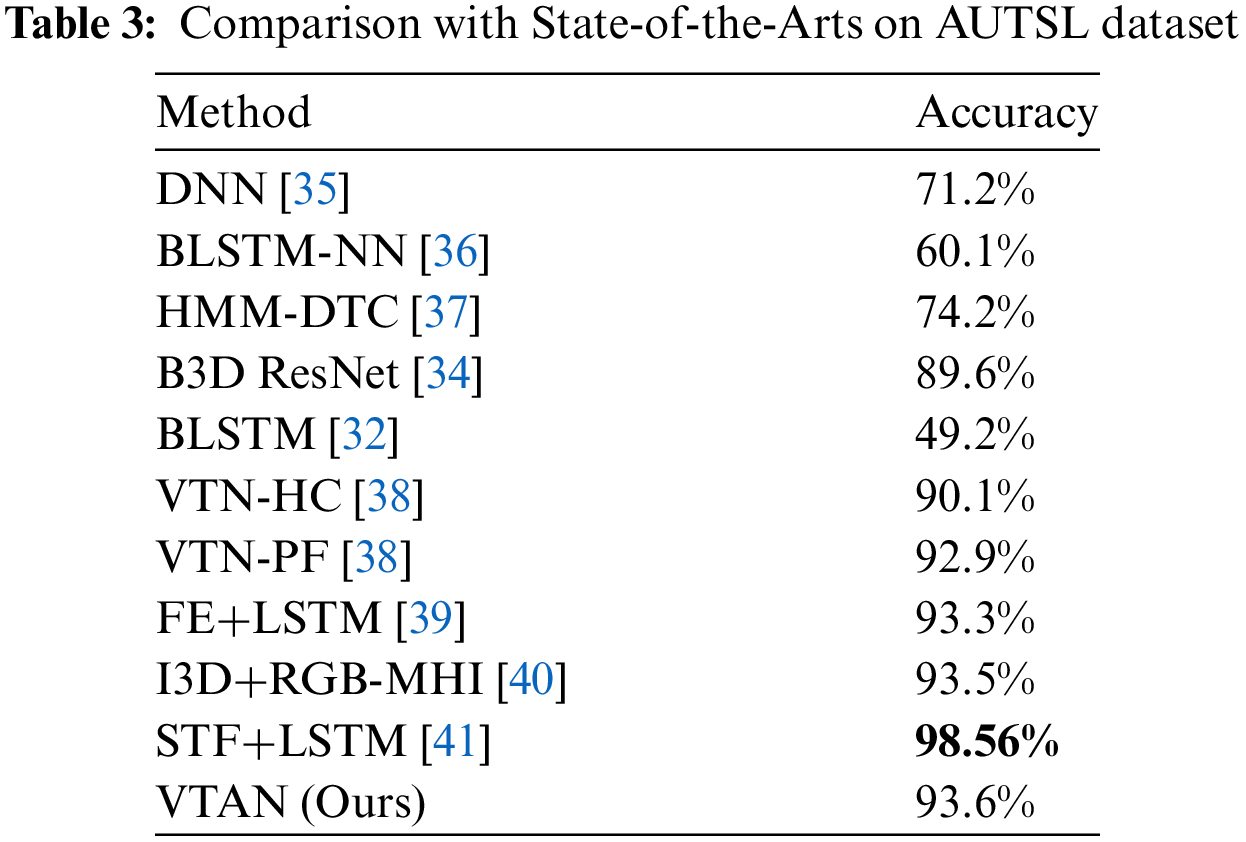

Table 3 summarizes the performance comparison on the AUTSL dataset. Our proposed method achieved an accuracy of 93.6%. While this result is strong and competitive, it is important to acknowledge that our method is not the best-performing approach. In addition, the accuracy curve in Fig. 9 illustrates the training and validation accuracy progression for VTAN, showing a steady improvement and eventual convergence for both metrics. This demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize well across the training and validation datasets. Furthermore, VTAN offers a significant advantage in terms of computational efficiency, largely due to the Visual Feature Aggregation for Keyframe Extraction module, which is specifically designed to select frames rich in information while eliminating redundant frames. This approach enhances the relevance of the input data and significantly reduces the computational load, making VTAN more efficient without sacrificing performance. We also show the confusion matrix of the VTAN model and [34] on the AUTSL dataset (Fig. 10). It can be observed that VTAN (a) demonstrates a strong diagonal pattern and few misclassifications. In contrast, the model (b) shows more scattered values off the diagonal, highlighting a greater number of misclassifications across various classes. This comparison underscores the effectiveness of VTAN on the AUTSL dataset. On the CSL500 dataset (Table 4), VTAN achieved 91.3% accuracy, exceeding previous methods by 1%. Beyond its accuracy, VTAN’s strength lies in its Transformer module, which emphasizes the extraction of features from hand regions, ensuring that the network allocates sufficient attention to these critical areas for sign language recognition. This focus on hand movement enables VTAN to capture fine-grained spatio-temporal features, contributing to its robust recognition performance.

Figure 9: Train vs. validation graph for VTAN on AUTSL dataset

Figure 10: Confusion matrix showing performance of models on AUTSL dataset. Please see Appendix A for category details

Overall, while VTAN may not achieve the highest accuracy in all scenarios, it consistently delivers competitive results and offers key advantages in terms of computational efficiency and targeted feature extraction. The combination of the Visual Feature Aggregation for Keyframe Extraction module and the Transformer module ensures that VTAN strikes a balance between accuracy and efficiency, making it a viable option for real-world dynamic sign language recognition tasks where computational resources may be limited. Future work may explore additional visualizations to further analyze misclassification patterns and provide more detailed insights into the model’s behavior.

VTAN’s superior performance stems from its efficient keyframe selection mechanism, which minimizes redundant data processing. The visual feature aggregation module optimizes computational efficiency while prioritizing crucial gesture moments. VTAN’s selective frame extraction enhances recognition accuracy by focusing on high-quality, informative data. VTAN’s Transformer-based spatio-temporal module significantly enhances feature extraction capabilities. The dynamic attention mechanism prioritizes hand regions, capturing subtle movements and spatial features, which are essential for recognizing complex sign language gestures. This ability to focus on the most critical parts of the input sequence, particularly the hands, allows VTAN to outperform other methods that may not employ such targeted attention mechanisms. VTAN preserves and efficiently utilizes temporal context in hand movement sequences. The Transformer module effectively models long-term dependencies, accommodating variations in gesture speed and transitions. This capability particularly benefits dynamic sign language recognition with varying gesture patterns. VTAN’s comprehensive spatial-temporal modeling outperforms traditional approaches in handling gesture complexities.

In conclusion, our study introduces a novel approach to dynamic sign language recognition, VTAN, leveraging two pivotal modules: visual feature aggregation for keyframe extraction and spatio-temporal hand feature enhancement module. Through experimentation on the AUTSL and SLR500 datasets, we have demonstrated VTAN’s significant performance advantages in recognizing dynamic sign language gestures. Compared to typical methods, our approach, facilitated by keyframe extraction and hand feature enhancement, yields superior recognition results, underscoring the importance and efficacy of these modules in dynamic sign language recognition tasks. Overall, our work offers novel insights and methods for advancing the field of dynamic sign language recognition and provides valuable implications for the improvement and development of sign language communication systems in practical applications. In future work, we plan to explore computational costs, such as inference time and resource consumption, to optimize VTAN’s efficiency. We will also investigate handling occlusion to improve robustness, and conduct further research on attention map visualizations and additional evaluation metrics to provide a deeper understanding of model performance.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 62076117 and 62166026, the Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Virtual Reality under Grant No. 2024SSY03151.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ziyang Deng, Weidong Min, Qing Han; data collection: Qing Han, Longfei Li, Mengxue Liu; analysis and interpretation of results: Ziyang Deng, Longfei Li, Mengxue Liu; draft manuscript preparation: Ziyang Deng, Weidong Min. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://cvml.ankara.edu.tr/datasets/ and http://home.ustc.edu.cn/~hagjie/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. H. Hu, W. Zhou, J. Pu, and H. Li, “Global-local enhancement network for NMF-aware sign language recognition,” ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 1–19, Jun. 2021. doi: 10.1145/3436754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. M. J. Cheok, Z. Omar, and M. H. Jaward, “A review of hand gesture and sign language recognition techniques,” Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern., vol. 10, pp. 131–153, Jan. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s13042-017-0705-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. R. Sreemathy, M. Turuk, I. Kulkarni, and S. Khurana, “Sign language recognition using artificial intelligence,” Educ. Inf. Technol., vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 5259–5278, May 2023. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11391-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. J. Zhao, W. Qi, W. Zhou, N. Duan, M. Zhou and H. Li, “Conditional sentence generation and cross-modal reranking for sign language translation,” IEEE Trans. Multimedia., vol. 24, pp. 2662–2672, Sep. 2021. doi: 10.1109/TMM.2021.3087006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. I. Rodríguez-Moreno, J. M. Martínez-Otzeta, and B. Sierra, “HAKA: HierArchical Knowledge Acquisition in a sign language tutor,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 215, Dec. 2023, Art. no. 119365. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Z. Liu, L. Pang, and X. Qi, “MEN: Mutual enhancement networks for sign language recognition and education,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst., vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 2802–2813, Jul. 2022. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3174031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. W. -G. Liou, C. -Y. Hsieh, and W. -Y. Lin, “Trajectory-based sign language recognition using discriminant analysis in higher-dimensional feature space,” presented at the 2011 IEEE Int. Conf. Multimedia Expo, Barcelona, Spain, Jul. 11–15, 2011, pp. 1–4. doi: 10.1109/ICME.2011.6012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. X. Xiong, W. Min, Q. Wang, and C. Zha, “Human skeleton feature optimizer and adaptive structure enhancement graph convolution network for action recognition,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 342–353, Jan. 2023. doi: 10.1109/TCSVT.2022.3201186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. H. Xiang, W. Min, Q. Han, C. Zha, Q. Liu and M. Zhu, “Structure-aware multi-view image inpainting using dual consistency attention,” Inf. Fusion, vol. 104, Jan. 2024, Art. no. 102174. doi: 10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. J. Schmidhuber, “Deep learning in neural networks: An overview,” Neural Netw., vol. 61, pp. 85–117, Jan. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Y. Xu et al., “Transformers in computational visual media: A survey,” Comput. Vis. Media., vol. 8, pp. 33–62, Jan. 2022. doi: 10.1007/s41095-021-0247-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. C. K. M. Lee, K. K. H. Ng, C. H. Chen, H. C. W. Lau, S. Y. Chung and T. Tsoi, “American sign language recognition and training method with recurrent neural network,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 167, Mar. 2021, Art. no. 114403. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. A. Kozlov, V. Andronov, and Y. Gritsenko, “Lightweight network architecture for real-time action recognition,” presented at the 35th Annu. ACM Symp. Appl. Comput., Brno, Czech Republic, Mar. 30–Apr. 3, 2020, pp. 2074–2080. doi: 10.1145/3341105.3373906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. K. Y. Lynn and F. Wong, “Recognition of dynamic hand gesture using hidden markov model,” presented at the 2022 Int. Conf. Green Energy, Comput. Sustain. Technol. (GECOSTJakarta, Indonesia, Jul. 28–30, 2022, pp. 28–30. doi: 10.1109/GECOST55694.2022.10010517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. S. G. Azar and H. Seyedarabi, “Trajectory-based recognition of dynamic Persian sign language using hidden Markov model,” Comput. Speech Lang., vol. 61, May 2020, Art. no. 101053. doi: 10.1016/j.csl.2019.101053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. W. Yang, J. Tao, and Z. Ye, “Continuous sign language recognition using level building based on fast hidden Markov model,” Pattern Recognit. Lett., vol. 78, no. 2, pp. 28–35, Apr. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2016.03.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. A. Hamed, N. A. Belal, and K. M. Mahar, “Arabic sign language alphabet recognition based on HOG-PCA using microsoft kinect in complex backgrounds,” presented at the 2016 IEEE 6th Int. Conf. Adv. Comput. (IACCBhimtal, India, Feb. 27–28, 2016, pp. 27–28. doi: 10.1109/IACC.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. C. Sun, T. Zhang, and C. Xu, “Latent support vector machine modeling for sign language recognition with Kinect,” ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1–20, May 2015. doi: 10.1145/2629481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. K. O’shea and R. Nash, “An introduction to convolutional neural networks,” Nov. 2015, arXiv:1511.08458. [Google Scholar]

20. R. M. Schmidt, “Recurrent neural networks (RNNsA gentle introduction and overview,” Dec. 2019, arXiv:1912.05911. [Google Scholar]

21. A. Wadhawan and P. Kumar, “Deep learning-based sign language recognition system for static signs,” Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 32, no. 12, pp. 7957–7968, Jun. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00521-019-04691-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. X. Han, F. Lu, J. Yin, G. Tian, and J. Liu, “Sign language recognition based on R(2+1)D with spatial-temporal-channel attention,” IEEE Trans. Human-Mach. Syst., vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 687–698, Aug. 2022. doi: 10.1109/THMS.2022.3144000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. S. Sharma and K. Kumar, “ASL-3DCNN: American sign language recognition technique using 3-D convolutional neural networks,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 80, no. 17, pp. 26319–26331, Jun. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11042-021-10768-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Y. Liu et al., “A wearable system for sign language recognition enabled by a convolutional neural network,” Nano Energy, vol. 116, Jul. 2023, Art. no. 108767. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2023.108767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. R. Zuo and B. Mak, “Improving continuous sign language recognition with consistency constraints and signer removal,” ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl., vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 1–25, 2024. doi: 10.1145/3640815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. W. Abdul et al., “Intelligent real-time Arabic sign language classification using attention-based inception and BiLSTM,” Comput. Electr. Eng., vol. 95, Oct. 2021, Art. no. 107395. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. O. Koller, N. C. Camgoz, H. Ney, and R. Bowden, “Weakly supervised learning with multi-stream CNN-LSTM-HMMs to discover sequential parallelism in sign language videos,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., vol. 42, no. 9, pp. 2306–2320, Sep. 2019. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2911077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. S. B. Abdullahi, K. Chamnongthai, V. Bolon-Canedo, and B. Cancela, “Spatial-temporal feature-based end-to-end Fourier network for 3D sign language recognition,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 248, 2024, Art. no. 123258. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. A. Baihan, A. I. Alutaibi, M. Alshehri, and S. K. Sharma, “Sign language recognition using modified deep learning network and hybrid optimization: A hybrid optimizer (HO) based optimized CNNSa-LSTM approach,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, 2024, Art. no. 26111. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-76174-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. D. R. Kothadiya, C. M. Bhatt, T. Saba, A. Rehman, and S. A. Bahaj, “SIGNFORMER: Deepvision transformer for sign language recognition,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 4730–4739, Jan. 2023. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3231130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. A. F. Alnabih and A. Y. Maghari, “Arabic sign language letters recognition using Vision Transformer,” Multimed. Tools Appl., pp. 1–15, Jan. 2024. doi: 10.1007/s11042-024-18681-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. O. M. Sincan and H. Y. Keles, “AUTSL: A large scale multi-modal turkish sign language dataset and baseline methods,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 181340–181355, Sep. 2020. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3028072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. J. Huang, W. Zhou, H. Li, and W. Li, “Attention-based 3D-CNNs for large-vocabulary sign language recognition,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol., vol. 29, no. 9, pp. 2822–2832, Sep. 2018. doi: 10.1109/TCSVT.2018.2870740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Y. Liao, P. Xiong, W. Min, W. Min, and J. Lu, “Dynamic sign language recognition based on video sequence with BLSTM-3D residual networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 38044–38054, Mar. 2019. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2904749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. T. Kim et al., “Lexicon-free fingerspelling recognition from video: Data, models, and signer adaptation,” presented at the Int. Conf. Comput. Speech Lang., Stockholm, Sweden, Aug. 21–25, 2017, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 209–232. doi: 10.1016/j.csl.2017.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. P. Kumar, H. Gauba, P. P. Roy, and D. P. Dogra, “A multimodal framework for sensor-based sign language recognition,” presented at the Neurocomput. Conf., Boston, MA, USA, Jun. 7–10, 2017, vol. 259, no. 11, pp. 7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2016.08.132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. H. Wang, X. Chai, and X. Chen, “Sparse observation (SO) alignment for sign language recognition,” presented at the Neurocomput. Conf., New York, NY, USA, Jan. 15–18, 2016, vol. 175, no. 1, pp. 674–685. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2015.10.112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. M. De Coster, M. Van Herreweghe, and J. Dambre, “Isolated sign recognition from rgb video using pose flow and self-attention,” presented at the IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., Nashville, TN, USA, Jun. 19–25, 2021, pp. 3441–3450. doi: 10.1109/CVPRW53098.2021.00383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. D. Ryumin, D. Ivanko, and A. Axyonov, “Cross-language transfer learning using visual information for automatic sign gesture recognition,” presented at the Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci., Nice, France, May 22–28, 2023, vol. 48, pp. 209–216. doi: 10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-1-2023-209-2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. O. M. Sincan and H. Y. Keles, “Using motion history images with 3D convolutional networks in isolated sign language recognition,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 18608–18618, Feb. 2022. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3151362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. D. Ryumin, D. Ivanko, and E. Ryumina, “Audio-visual speech and gesture recognition by sensors of mobile devices,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 4, 2023, Art. no. 2284. doi: 10.3390/s23042284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

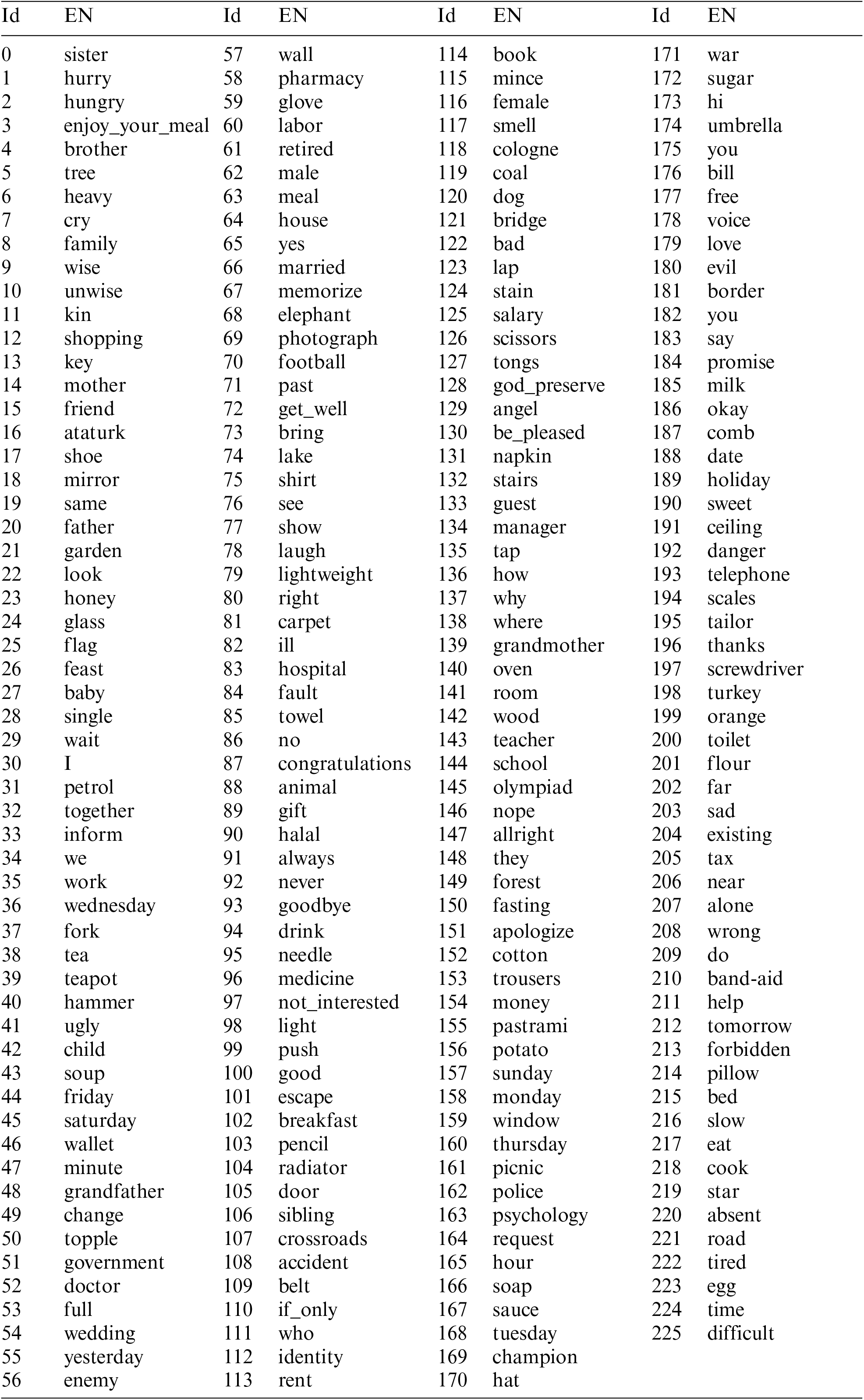

The following table enumerates all 226 categories of sign language gestures used in the confusion matrix analysis (Fig. 10). Each number corresponds to its respective position in the confusion matrix axes.

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools