Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MSSTGCN: Multi-Head Self-Attention and Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network for Multi-Scale Traffic Flow Prediction

School of Computer Science, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

* Corresponding Author: Xinlu Zong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Graph Neural Networks: Methods and Applications in Graph-related Problems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 3517-3537. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.057494

Received 19 August 2024; Accepted 07 November 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

Accurate traffic flow prediction has a profound impact on modern traffic management. Traffic flow has complex spatial-temporal correlations and periodicity, which poses difficulties for precise prediction. To address this problem, a Multi-head Self-attention and Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (MSSTGCN) for multiscale traffic flow prediction is proposed. Firstly, to capture the hidden traffic periodicity of traffic flow, traffic flow is divided into three kinds of periods, including hourly, daily, and weekly data. Secondly, a graph attention residual layer is constructed to learn the global spatial features across regions. Local spatial-temporal dependence is captured by using a T-GCN module. Thirdly, a transformer layer is introduced to learn the long-term dependence in time. A position embedding mechanism is introduced to label position information for all traffic sequences. Thus, this multi-head self-attention mechanism can recognize the sequence order and allocate weights for different time nodes. Experimental results on four real-world datasets show that the MSSTGCN performs better than the baseline methods and can be successfully adapted to traffic prediction tasks.Keywords

The development of urbanization has brought increasingly serious traffic congestion [1] while giving people convenience. Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) [2] macroscopically regulates urban traffic through sensing, and control combined with data analysis and other information and communication technologies, which contributes greatly to smart cities. As a significant task of ITS [3], traffic prediction can not only provide a decision basis for traffic managers [4] but also provide advice for people’s travel [5]. The main goal of traffic forecasting is to predict future traffic trends by analyzing historical traffic data. Early methods that have been used for traffic prediction in past research include classical statistical methods [6] and methods based on machine learning [7]. However, traditional methods do not perform well due to the complex nonlinear nature of traffic data. At present, approaches based on deep learning have shown their superiority in traffic prediction [8].

Traffic flow data differs from other simple time series data due to the influence of spatial factors. Deep learning methods can effectively capture high-dimensional features, leading to better prediction results, such as recurrent neural network (RNN) and its variants long short-term memory (LSTM) [9] and gated recurrent unit (GRU) [10] which have demonstrated excellent prediction performance on sequence data. In addition, it has been observed that traffic flow is influenced not only by historical patterns but also by the spatial relative position within the topological road network [11]. Therefore, many studies have used graph neural networks (GNN) combined with RNN for spatial-temporal traffic prediction [12,13]. For example, Zhao et al. [14] proposed a diffusion convolutional recurrent neural network (DCRNN). Li et al. [15] presented a temporal graph convolutional network (T-GCN). The two models use graph convolutional networks (GCN) and RNNs to learn the spatial features of traffic flow.

While most traffic prediction methods prove effective, three crucial issues still require attention:

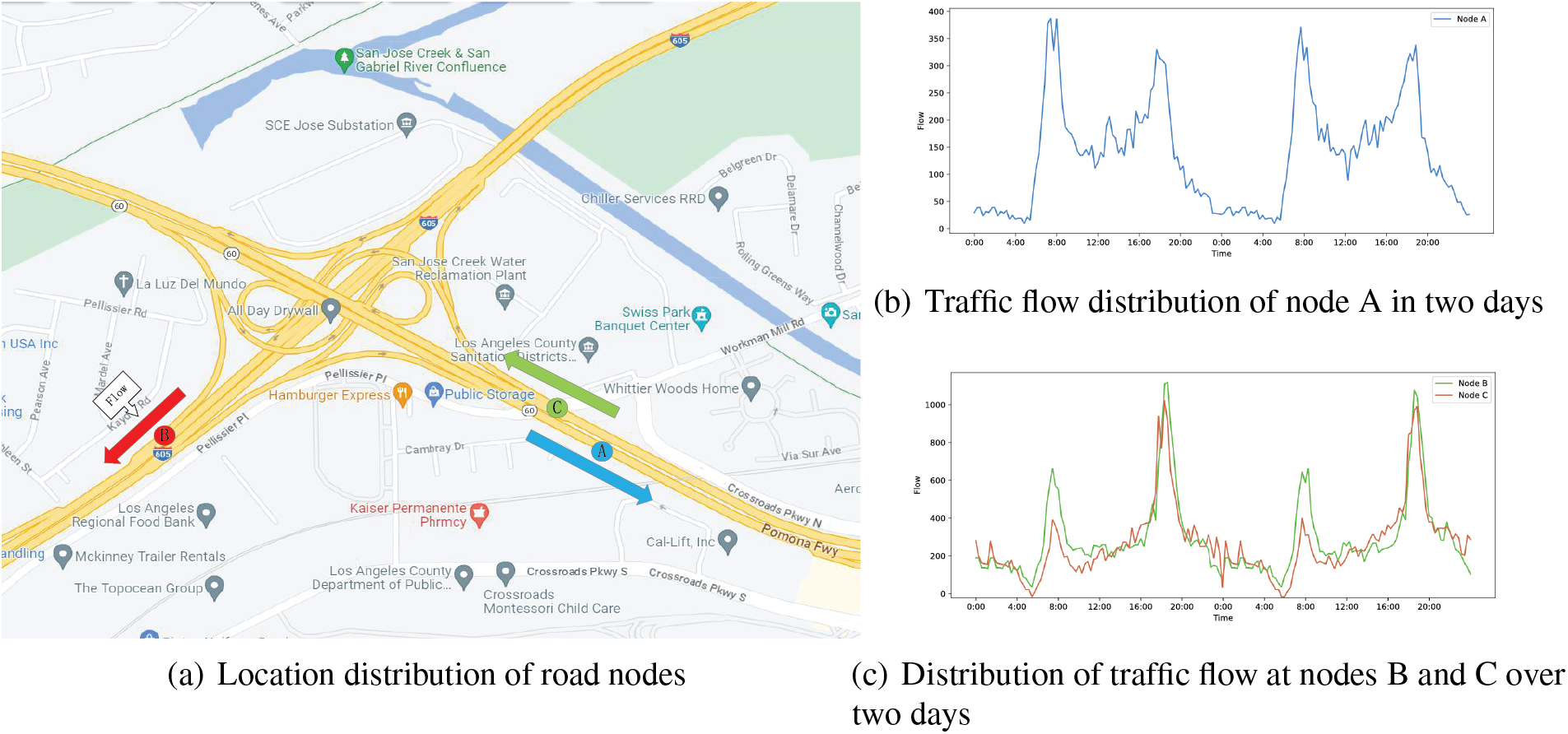

First, traffic flow on the same road, in reality, exhibits periodicity, which correlates with the cyclic nature of people’s activities [16]. Fig. 1a represents the location distribution of different road nodes. As depicted in Fig. 1b, the traffic state of node A shows periodicity after a certain number of cycles. Guo et al. [17] integrated daily and hourly periodic data as part of the input. Although their method performed well in short-term prediction, the weekly periodic impact was not considered, and thereby long-term temporal correlations were ignored. Therefore, it is necessary to extract periodic multi-scale time levels (e.g., hourly, weekly, daily) for traffic flow patterns.

Figure 1: Spatial-temporal correlation of nodes at different geographic locations

Second, most existing traffic prediction methods primarily focus on spatial road information within the vicinity. However, road traffic in cities that are far apart should be correlated [18] and more complex compared to the neighborhood space. For example, nodes B and C in Fig. 1c have similar traffic flows, but the two areas are not adjacent to each other, which implies that there may be hidden traffic pattern associations between them. Therefore, modeling cross-regional traffic dependency patterns in a global context is necessary.

Third, traffic flows are not only sequentially dependent on time, but may also have hidden long-term dependencies [19]. The long loop structure of LSTM and GRU fixation makes each temporal node strongly dependent on the previous temporal node, and long-term dependencies cannot be effectively captured when the temporal spacing between node flows is too long. In addition, although the attention-based methods can capture long-term dependence, they ignore the sequential nature of the traffic sequence.

Aiming at the above problems, we investigate prediction methods for multi-scale periodic traffic flow to fuse the adjacent local spatial and cross-regional global spatial information. Thus, both the short-term and long-term dependencies of traffic data can be captured. This paper introduces a Multi-head Self-attention and Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (MSSTGCN) for multi-scale traffic flow prediction.

The primary contributions of this paper are as follows:

The traffic flow is divided into multi-scale (i.e., hourly, daily, weekly) forms to explore the periodicity from multiple time dimensions, which allows for a comprehensive analysis of traffic patterns that vary over different time scales. Multi-scale modeling can enhance the ability to identify and predict complex traffic patterns within these distinct temporal contexts.

A graph attention residual network (GARN) layer which is capable of fusing spatial information of different dimensions is introduced to learn global spatial dependencies. This layer can not only enhance the model’s ability to capture intricate relationships within the traffic data but also improve the generalization ability across various traffic scenarios.

This hybrid architecture leverages the strengths of GRU in capturing sequential dependencies while benefiting from the transformer attention mechanism. The incorporated positional encoder enables the attention mechanism to recognize the order of sequences. This combination can enhance the model’s capability to capture complex temporal patterns, thereby improving prediction accuracy.

Experiments on real traffic datasets of the MSSTGCN model and other baseline methods are conducted. The experimental results indicate that MSSTGCN outperforms other models.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on traffic prediction. Section 3 defines the traffic prediction problem and outlines the proposed model. Section 4 describes experiments conducted with real traffic datasets and includes a comparative analysis with baseline approaches. Finally, Section 5 offers a summary and outlook for the paper.

In the early stages, traffic forecasting is often considered a type of time series forecasting. Early classical traffic forecasting approaches include Historical Average (HA) [20] and Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) [21]. However, simple regression statistics do not model the nonlinearity and complexity of traffic data, making traditional methods limited. To tackle this issue, various machine learning algorithms have been introduced to handle complex traffic data. For instance, Wang et al. [22] introduced a two-pattern recognition K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) model for traffic prediction, while Luo et al. combined discrete Fourier transform with Support Vector Regression (SVR) [23] to predict residual sequences. However, these machine learning algorithms require manual design of artificial features and cannot effectively model dynamic and complex traffic data.

In recent years, deep learning has increasingly become a dominant approach in traffic prediction. Deep learning [24], as a branch of machine learning, utilizes multi-layer neural networks for feature learning and pattern recognition. It is characterized by its powerful ability to automatically extract complex feature representations from raw data. Fu et al. [9] utilized LSTM and GRU and achieved better results than the traditional methods. Xu et al. [25] constructed an LSTM-based sequential network model for predicting the demand of urban taxis. A standalone RNN model does not incorporate the spatial information of traffic data. Therefore, studies [26] have employed Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to capture the spatial dependencies among roads. Zhang et al. [27] embedded CNN and LSTM into a Generative Adversarial Nets (GAN) framework to capture spatial-temporal dependencies. However, CNNs can only handle 2D grid images, and real traffic topology roads are intricate and complex, making the spatial fitting ability of CNNs limited. GNNs are widely employed for traffic prediction because they can model the complex relationships and dependencies inherent in traffic data. Given the temporal nature of traffic data, GNNs are often combined with temporal modeling techniques such as RNNs for learning the spatial-temporal dependencies. Chen et al. [28] combined GCN with LSTM to predict traffic flow. Su et al. [29] combined spatial gated linear unit block, GCN, and LSTM to explore the interaction between multiple traffic parameters. Wang et al. [30] integrated GAN and GCN to automatically model dynamic spatial-temporal states. In addition, considering that GCN only aggregates spatial information for local neighborhood nodes and ignores the global spatial relationships between regional nodes. Zhao et al. [31] devised a spatial attention mechanism by evaluating relationships between nodes. Zhang et al. [32] designed a graph-neural hierarchical structure to maintain spatial dependencies at both local and global scales, integrating the Graph Attention Network (GAT) and graph diffusion mechanism. GAT and graph diffusion mechanisms can focus on more spatial dependencies. But vanishing gradient may occur in deep network learning, leading to weaker learning of spatial dependencies.

In particular, RNN maintains the temporal relationships of traffic flow data through a gating mechanism. However, its long cyclic structure makes it challenging to extract links between time nodes that are far apart [33]. Bai et al. [34] proposed the Attention Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (A3T-GCN) model, which introduced the attention mechanism by adjusting weights between different time nodes. However, a single attention mechanism tends to give equal importance to each time node and fails to recognize the sequential nature of traffic sequences. The Multi-Head SpatioTemporal Attention Graph Convolutional Network (MHSTA-GCN) [35] combines GCN, GRU, and multi-head attention modules. In the model, GCN is used to learn the basic features of nodes by capturing the complex spatial topology of the graph, and GRU is introduced to capture the dynamic time dependence through multi-head attention mechanism. The integration of GRU and attention mechanism takes into account both the global and temporal sequential nature of traffic flow. Dong et al. [36] proposed a Multi-scale Temporal and Enhance Spatial transformer (MTESformer) model, which combined multi-head self-attention mechanism with a multi-scale convolutional unit to learn traffic flow patterns at different scales and capture long-term dependencies. However, the model ignored short-term temporal correlation and spatial correlation. Chai et al. [37] presented a Spatio-Temporal Dynamic Multi-hop Network (ST-DMN) to update the iterative traffic network graph by combining multi-hop operation with diffusion convolution technique. The novel graph generation technique and diffusion graph convolution can effectively capture the global dynamic spatial dependencies, but they lead to excessive parameters and increased training time. In addition, all these methods ignore the periodicity of traffic flow, which is a hidden temporal dependency determined by people’s living habits.

Based on the above problems, we propose a new deep learning model MSSTGCN, which utilizes multi-head attention and spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for multi-scale traffic flow prediction. By dividing traffic flow data into hourly, daily, and weekly scales, the periodic features in multiple time dimensions can be learned. A graph attention residual neural network layer is designed to capture global spatial dependencies and identify hidden traffic patterns in different regions. A layer based on graph attention residual network and a T-GCN module is designed to extract the global spatial dependencies across regions and local spatial-temporal dependencies, respectively. A transformer layer that contains self-attention mechanism, positional encoder, layer normalization, and a fully connected output layer is proposed.

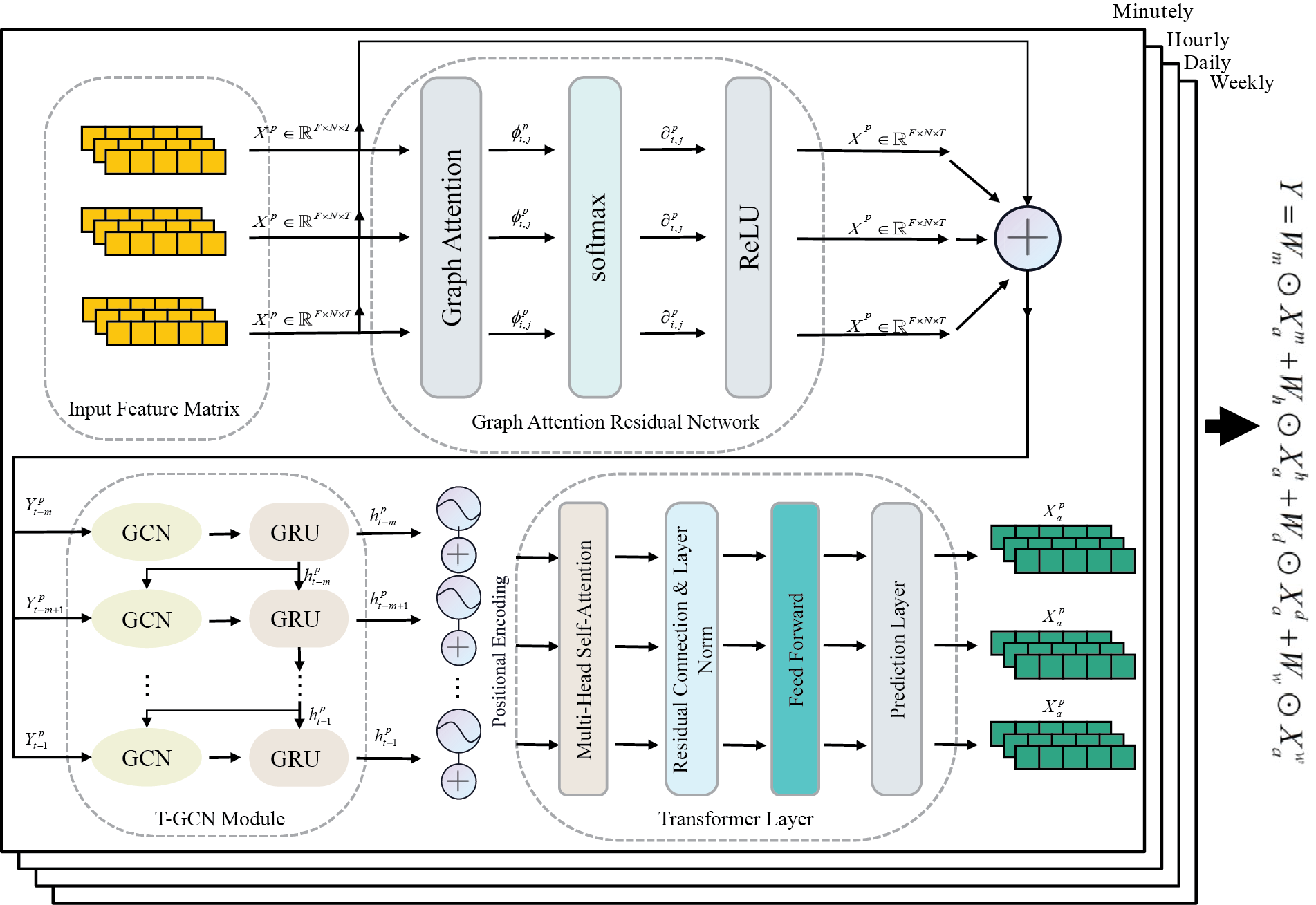

The structure of the MSSTGCN model is shown in Fig. 2. It integrates the GARN, GCN, GRU, and multi-head self-attention mechanisms, each designed to extract global spatial characteristics, local spatial-temporal characteristics, and comprehensive temporal features, respectively.

Figure 2: Overall structure of the MSSTGCN model

Definition 1: Spatial graph structure: the topology of a transportation network is represented as an unweighted graph

Definition 2: Node attributes: the attribute features of a sensor node at moment t are represented as vector

Traffic prediction task [38] refers to predicting future traffic flow

To investigate the underlying cyclical patterns in traffic flow, a multilevel temporal structure is proposed, where the time-difference period of the road nodes is set to hourly, daily, and weekly, i.e.,

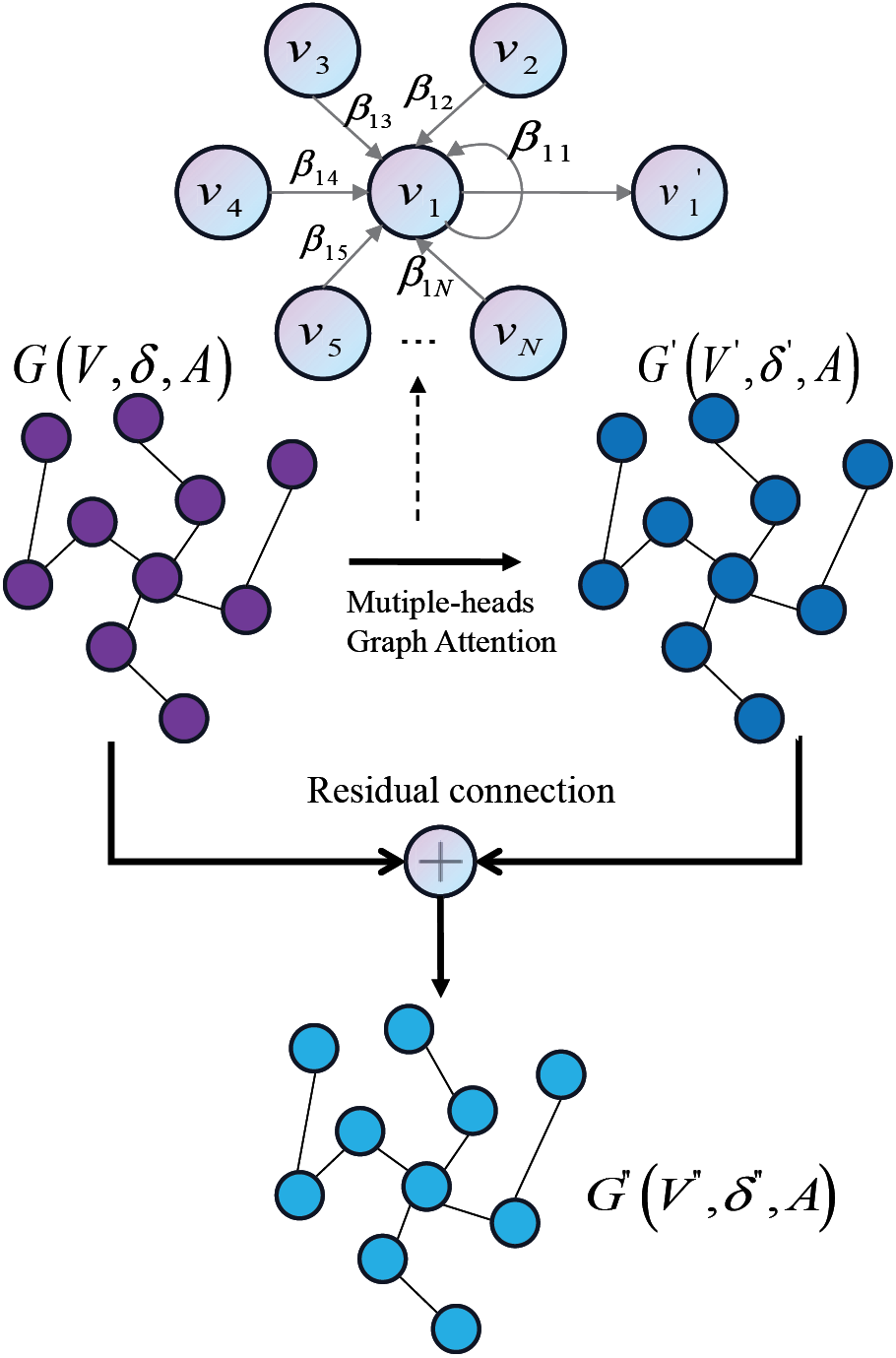

The structure of the graph attention residual network layer is illustrated in Fig. 3. Initially, the historical feature vector

Figure 3: Graphical attention residual network layer structure

where

The current node gets updated by evaluating its relationship with all other nodes through the relevance weights

where

3.3 Local Spatial-Temporal Module

Local spatio-temporal dependencies are real-time and impactful because any unexpected traffic condition (e.g., car accident, etc.) can affect the traffic flow in a short period. We use T-GCN [14] as a module to capture local spatio-temporal dependencies.

The feature normalized laplace matrix can be expressed as

where

GRU, as a commonly used time series data prediction model, solves the gradient vanishing and gradient explosion problems of RNN to a certain extent. GRU controls the amount of information to be retained from the historical information of the previous hidden state and the current state through the reset gate

where

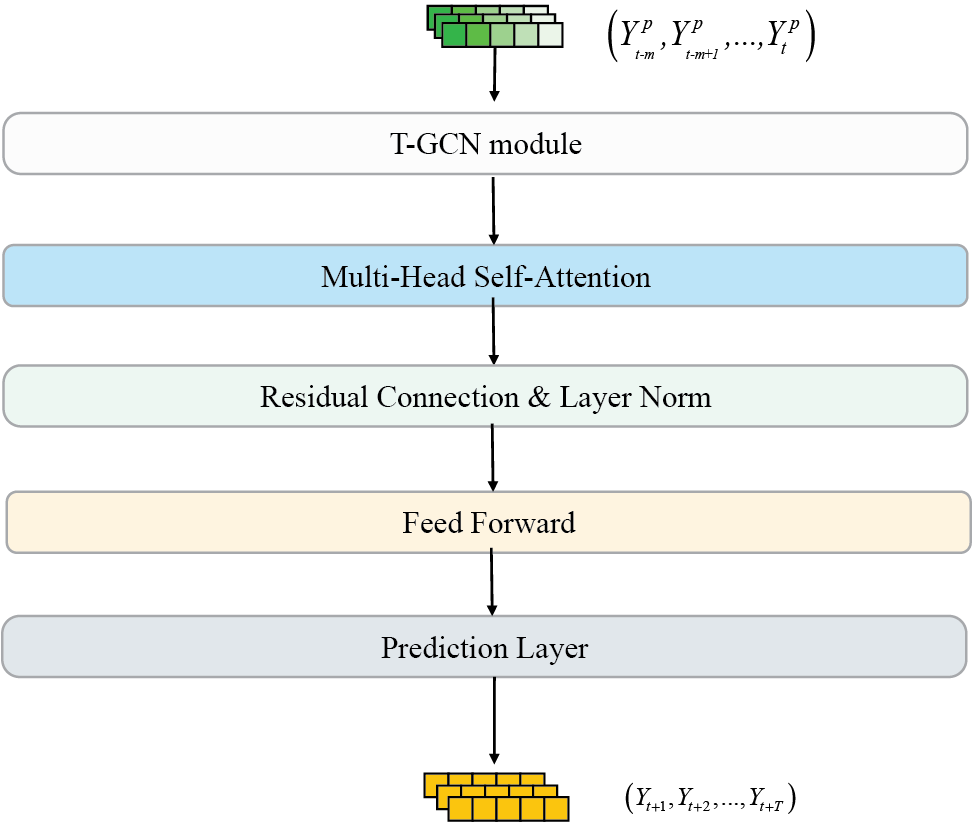

The final output

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of transformer layer structure

In this paper,

To better capture the long-term time dependence of traffic data, a multi-head self-attention mechanism is used to adaptively assign weights to the historical time steps of the feature matrix. Specifically, the spatio-temporal feature matrix

where

The layer normalization is further used to stabilize the training of the neural network and interact with the feature information of different dimensions through residual connection. Similarly, the feed-forward layer is used to enhance the nonlinear fitting ability of the model to the traffic data as shown in Eqs. (17)–(18):

where

Ultimately, the output of the proposed model is a linear aggregation containing four structurally identical multiscale components, i.e., original (

where

Self-attention in the Transformer layer attends to all-time nodes in a parallelized manner to capture long-term temporal dependencies. The training objective of the model is to minimize the difference between the real traffic data x and the predicted data y. The loss function is shown in Eq. (20), where

Experiments are carried out on four real-world traffic datasets, including Los-loop, SZ-taxi, METR-LA, and PEMS-BAY, to evaluate the prediction performance of the MSSTGCN model. The Los-loop dataset contains the data from 207 freeway sensors in Los Angeles County for the period of 01 March to 07 March 2012. The SZ-taxi dataset was derived from taxi data in Shenzhen City from 01 January to 31 January 2015. The METR-LA dataset is the traffic data of Los Angeles freeways from 01 March to 30 June 2012. The PEMS-BAY dataset developed by the California Transportation Agencies Performance Measurement System includes the data of 325 sensors in total from 01 January 2017, to 31 May 2017.

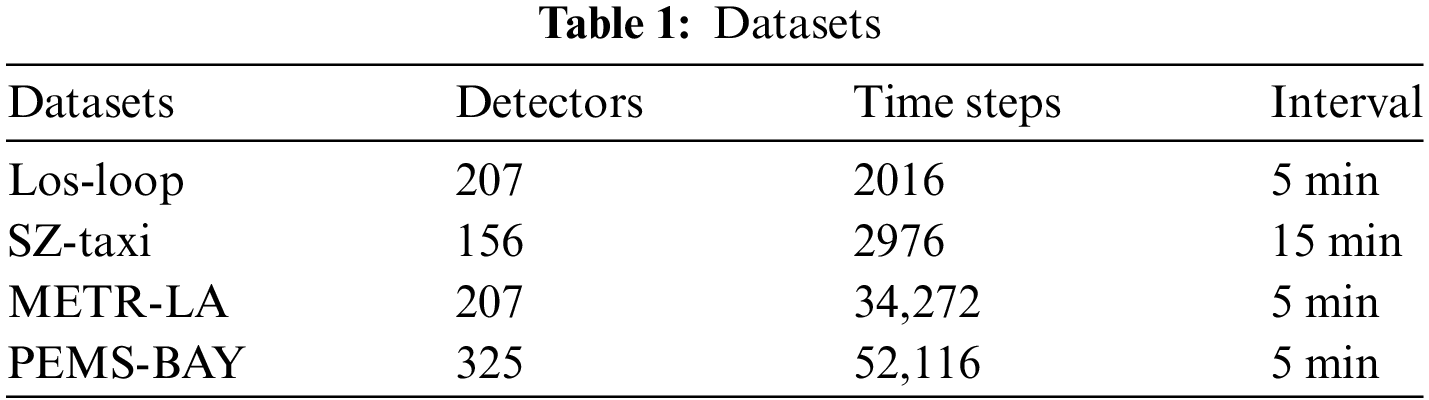

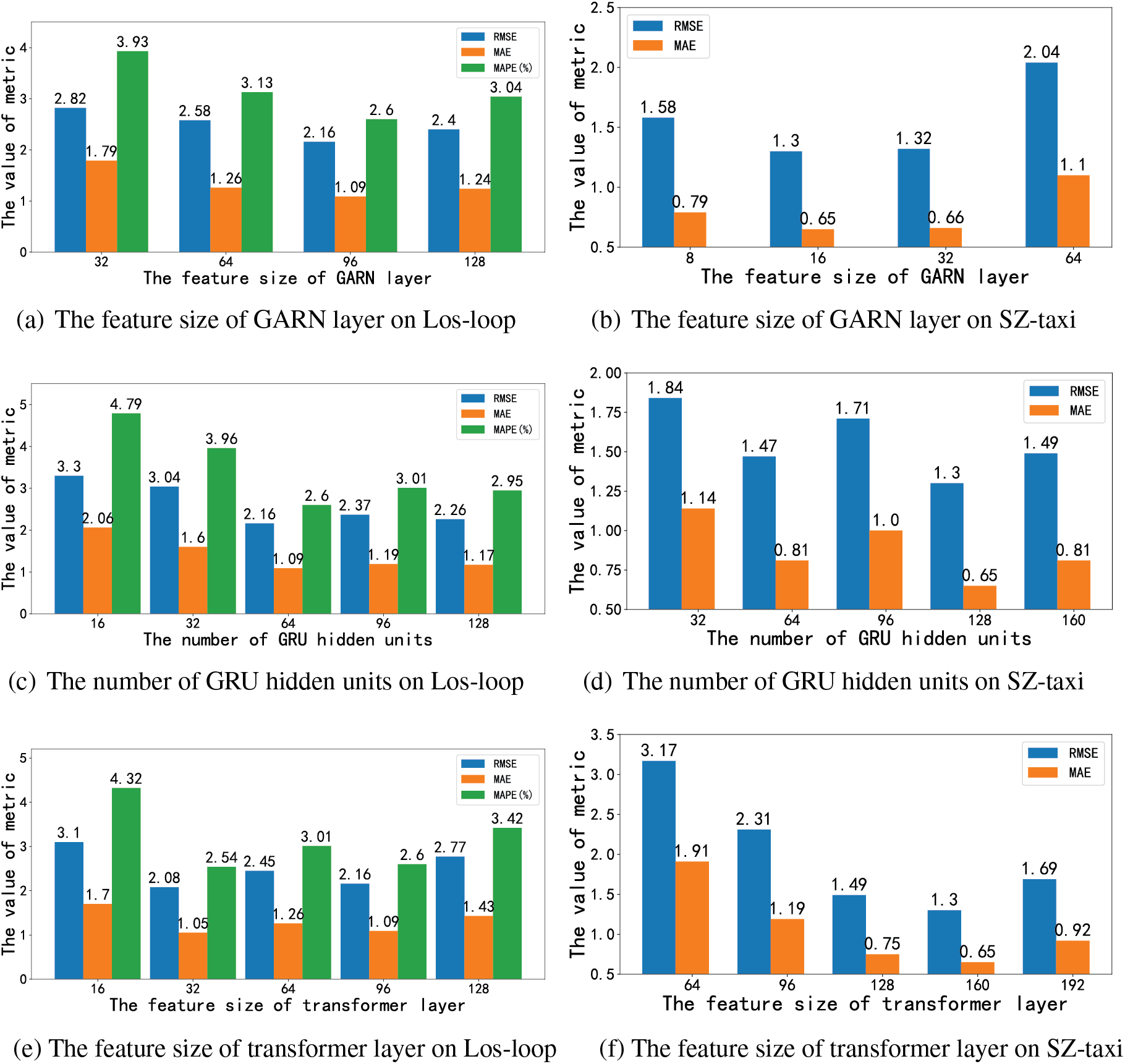

All of the data feature vehicle speeds on the road, and all contain a matrix of collected traffic flow features as well as a road network adjacency matrix. It is worth noting that all the datasets collect traffic flow data every five minutes, except for the SZ-taxi dataset, which collects traffic flow data every fifteen minutes. The details of the four datasets are shown in Table 1.

We use six metrics to test the difference between model predictions and real data to evaluate model prediction performance. RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), MAE (Mean Absolute Error), and MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error) are employed to quantify the prediction error magnitude, where smaller values indicate lower prediction errors in the model. Accuracy measures the precision of model predictions. Additionally,

where

4.2 Experimental Settings and Baseline Methods

For deep learning models, different hyperparameters will affect the prediction results. In this paper, the hyperparameter settings are as follows. The learning rate is 0.001, and the number of training epochs is 3000. The batch size values for the SZ-taxi dataset and other datasets are 64 and 16, respectively. For the METR-LA and PEMS-BAY datasets, the feature size of the transformer layer, the number of hidden units, and the feature size of GRU are set to 64.

80% of all datasets are used for training, while the remaining 20% are reserved as test data. To expedite model convergence during training, we employ the maximum normalization method to scale the data within the range [0, 1], expressed as. All models were trained on a computer with an NVIDIA 3060 GPU using the Pytorch framework.

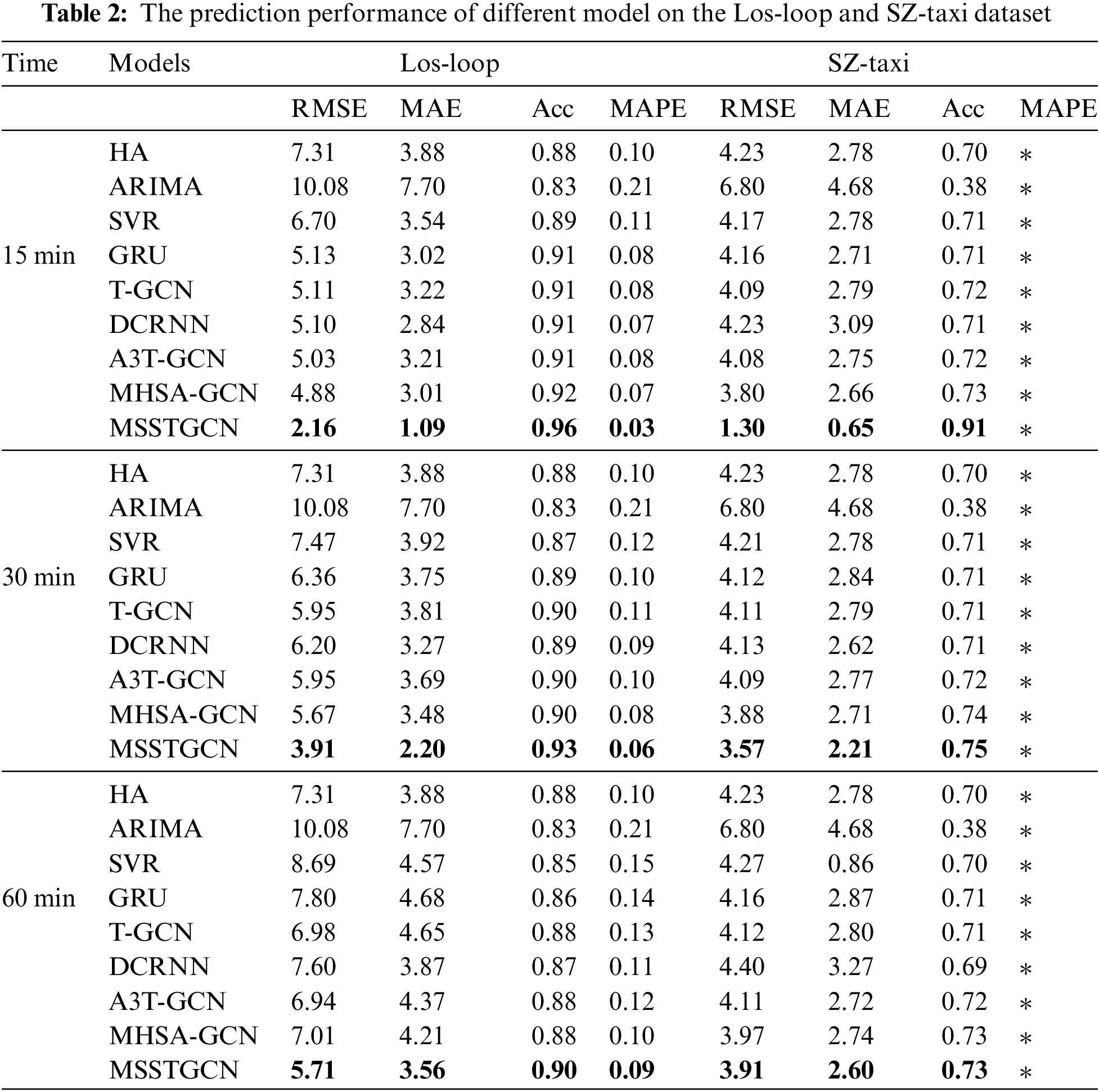

For the Los-loop and SZ-taxi datasets, methods including Historical Average (HA) [20], AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) [21], Support Vector Regression (SVR) [23], Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) [10], Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (T-GCN) [14], Attention Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (A3T-GCN) [34], and Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network (DCRNN) [15] are compared. For the METR-LA and PEMS-BAY datasets, Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks (STGCN) [39], DCRNN [15], Graph Multi-Attention Network (GMAN) [40], Fully Connected gated graph architecture (FC-GAGA) [41], Spatio-Temporal data using deep Meta learning Network model (ST-MetaNet) [42], Graph Wavenet [43], Multivariate Time series forecasting with Graph Neural Networks (MTGNN) [44], Mixed Hop diffuse Ordinary Differential Equation (MHODE) [45], Multi-Head SpatioTemporal Attention Graph Convolutional Network (MHSA-GCN) [35], Multi-scale Temporal and Enhance Spatial transformer (MTESformer) [36], and SpatioTemporal Dynamic Multi-Hop network (ST-DMN) [37] are compared.

Table 2 shows the prediction results on the Los-loop and SZ-taxi datasets, with the prediction time steps of 15, 30, and 60 min, respectively. The MAPE cannot be computed in the SZ-taxi dataset because there is a large amount of noisy data with the value close to 0. The other evaluation metrics are adequate to substantiate the predictive capability of the baseline method.

Table 2 illustrates that traditional HA, ARIMA, and SVR methods struggle to accurately model the complex nonlinear traffic data, showing inferior prediction performance compared to deep learning-based methods. In the 15-min prediction of the two datasets, the prediction performance of GRU is better than that of the traditional methods, and the RMSE is reduced by about 23.48% and 0.08%, respectively, compared with SVR. However, GRU solely captures the temporal dependencies in traffic data while overlooking spatial dependencies, thereby limiting its prediction performance. T-GCN and DCRNN integrate GRU with GCN to capture both temporal and spatial dependencies in traffic data. In the 30-min prediction task on the Los-loop dataset, RMSE values have been reduced by about 6.42% and 2.49%, respectively, compared to GRU alone. A3T-GCN utilizes the attention mechanism to capture the long-term temporal dependence and achieves better prediction performance. However, it neglects the fact that spatial dependence should also be global, and the attention mechanism uniformly treats all temporal nodes. The MHSTA-GCN combines graph convolutional network and multi-head attention module, with nodes in the network acting as feature representations of road traffic speeds. GCN is used to capture spatial correlations of the graph, and the multi-head attention models global temporal correlations. However, similar to A3T-GCN, global spatial dependencies are ignored. In the 15-min and 60-min predictions on the two datasets, MSSTGCN reduces the RMSE by about 55.74%, 65.79%, 18.54%, and 1.51%, respectively, and improves the accuracy by about 5.05%, 21.29%, 2.27%, and 0.68%, respectively. MSSTGCN captures the spatial-temporal dependence from the local to the global level and captures the temporal information of the traffic more comprehensively. Furthermore, it considers the implicit traffic periodicity and obtains richer feature information. In both datasets, MSSTGCN exhibits the best prediction performance among all baseline methods.

The prediction results on the METR-LA and PEMS-BAY datasets are shown in Table 3. Combining graph convolution and gated spatial-temporal convolution, STGCN applies multiple spatial-temporal convolutional blocks. However, these convolutional operations are mainly based on the domain information and ignore the global context. GMAN generates future feature representations by adding an attention layer to the encoder and decoder structure, with a multi-headed attention mechanism that captures global spatial-temporal correlations and outputs the representations through a gated fusion mechanism. Compared with the 15-min prediction results of STGCN and GMAN, RMSE values on the two datasets are reduced by about 3.31% and 1.01%, and the MAPEs are reduced by about 2.49% and 0.69%, respectively. MTGNN learns an adaptive adjacency matrix through the traffic sequences, which are coupled with a spatial-temporal convolutional module. Compared with the 30-min prediction of GMAN, the RMSE of MTGNN is reduced by 4.49% and 1.06%, respectively. MHODE utilizes a gated spatial-temporal convolution network and a hybrid jump-diffusion ordinary differential equation to capture long-term temporal dependence. MTESformer develops a multi-scale temporal transformer. It focuses on temporal correlations in time series data and combines the self-attention mechanism with the multi-scale convolutional unit to identify different traffic flow patterns and capture long-term dependencies. However, MTESformer does not perform well in short-term prediction since the short-term temporal correlations are ignored. ST-DMN captures long-range spatial dependencies by combining multi-hop operations with diffusion convolution techniques, but it fails to take into account the periodic changes in traffic flow. Compared with MTGNN, MTESforme reduces the MAE of the 60-min prediction by 3.44% and 3.61%, respectively. MSSTGCN learns the hidden traffic periodicity through a multi-scale form and outperforms the baseline methods in most time steps.

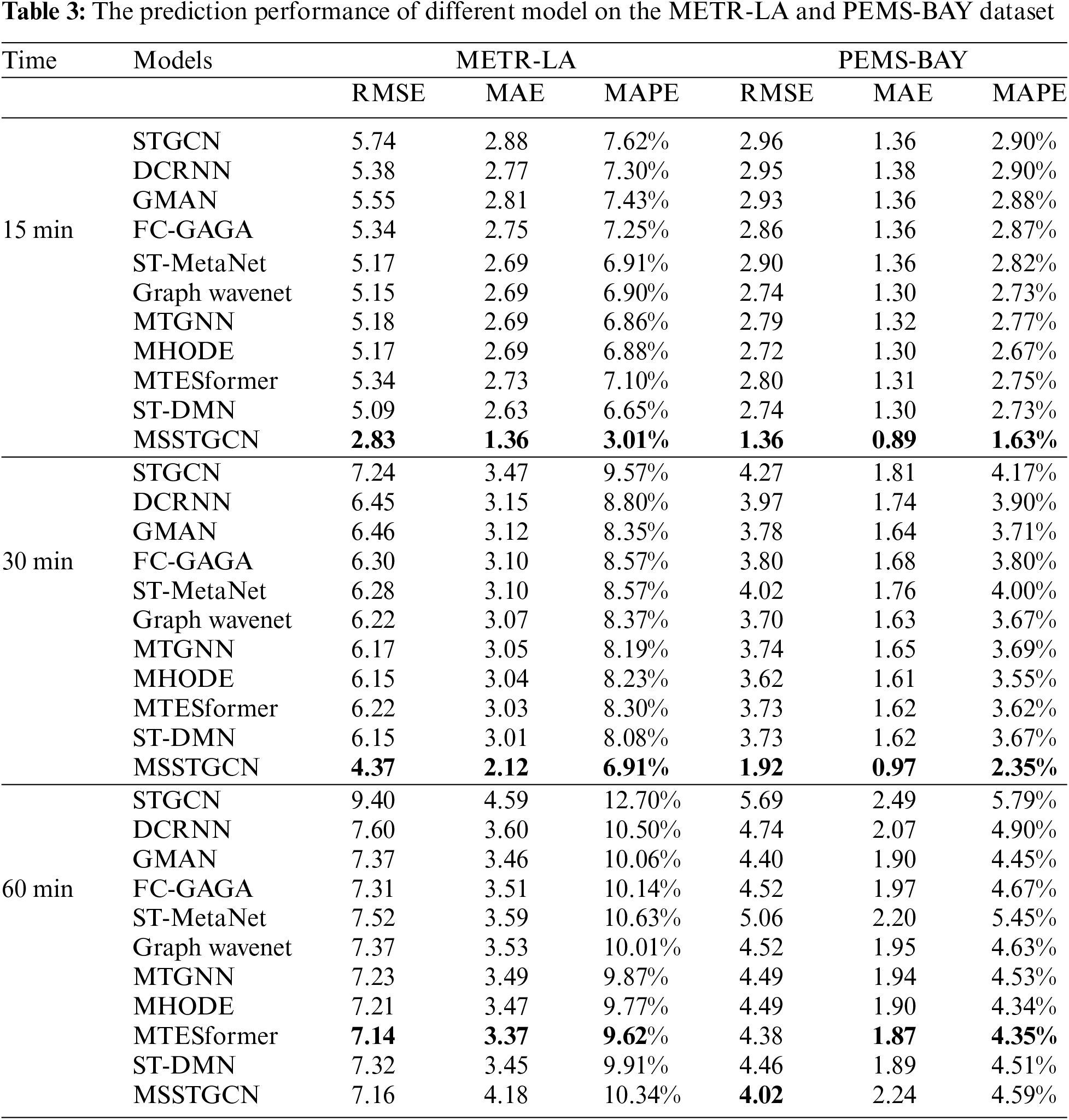

The significance of various hyperparameters on the predictive performance of the model is substantial. Three key hyperparameters affect the learning ability of MSSTGCN to capture spatial-temporal correlations. Fig. 5 depicts how RMSE, MAE, and MAPE vary across Los-loop and SZ-taxi datasets under different hyperparameter configurations. In the Los-loop dataset, the model achieves optimal results with minimal prediction error when setting the feature size of the GARN layer to 96, the number of GRU hidden units to 64, and the feature size of the transformer layer to 32. For the SZ-taxi dataset, the model performance is best when these three values are set to 16, 128, and 160, respectively. Moreover, adjusting hyperparameter values either downward or upward can constrain the model’s performance or heighten its complexity, thereby diminishing predictive accuracy. When the values of these hyperparameters are smaller, the model cannot capture more hidden correlations and cannot achieve the expected effects. However, this does not mean that larger values of these parameters are better, as the hidden correlations between traffic flows are limited. External factors such as weather and holidays that affect traffic flow can be treated as learnable hidden features. However, when the hyperparameters are too large, they may dilute the learning of these correlations, resulting in poor predictive performance.

Figure 5: The impact of different hyperparameters on prediction performance on the Los-loop and SZ-taxi datasets

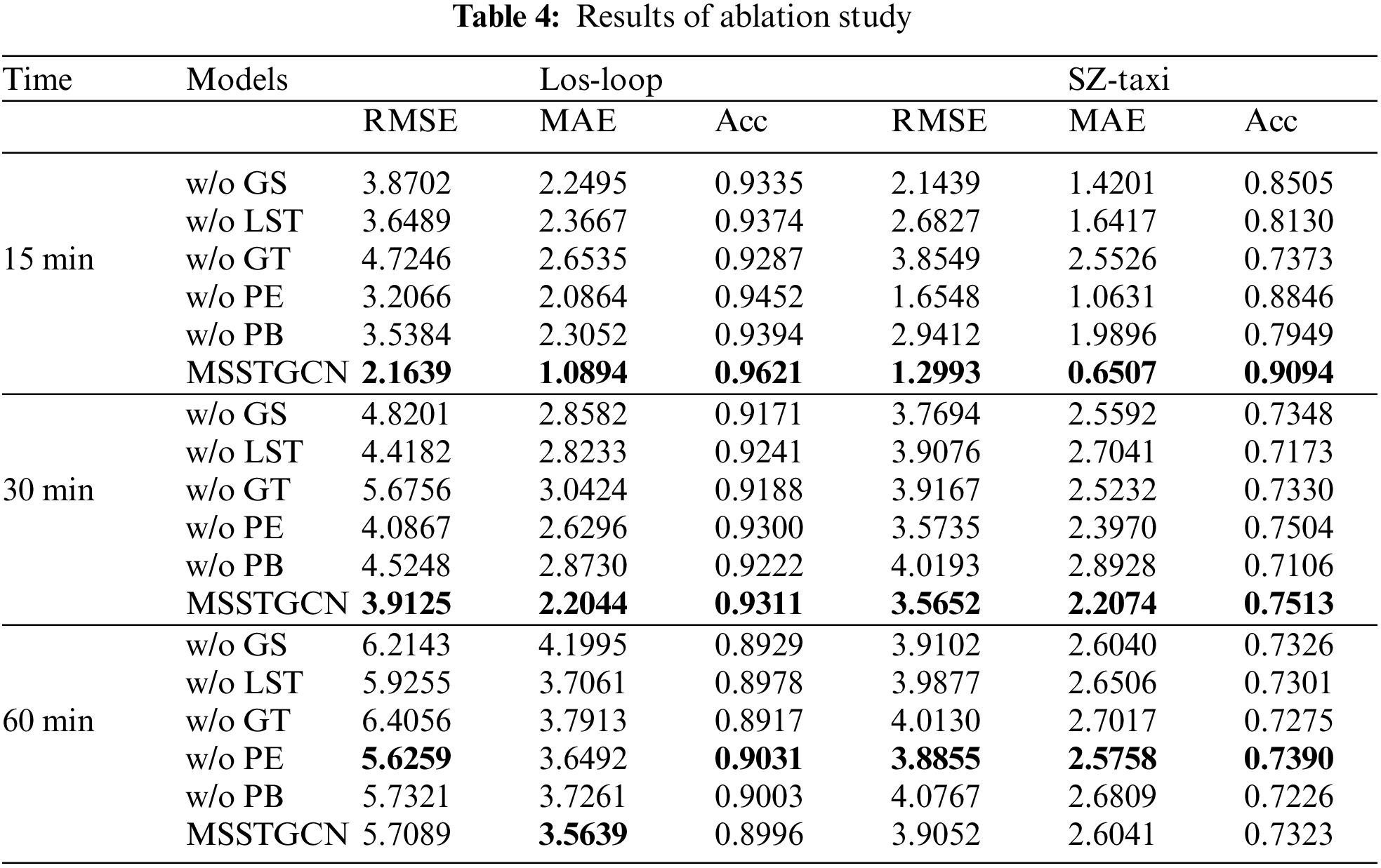

To assess the influence of each component of MSSTGCN on prediction performance, five variants are tested on the Los-loop and SZ-taxi datasets for ablation study. (1) w/o GS: Removes the GARN layer in MSSTGCN and fails to capture the global spatial dependence. (2) w/o LST: Removes the T-GCN module preventing MSSTGCN from capturing local spatial-temporal dependencies. (3) w/o GT: The transformer layer responsible for capturing long-term temporal dependencies is removed. (4) w/o PE: In this variant, the positional encoding in the transformer layer is removed and the self-attention mechanism is unable to recognize sequential features. (5) w/o PB: The multi-scale module in MSSTGCN is removed, and the hidden traffic data periodicity cannot be learned.

The experimental results are shown in Table 4. It indicates that the MSSTGCN model has the best performance. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the local-to-global spatial-temporal dependencies and the hidden periodicity in traffic prediction tasks. The GARN layer of the w/o GS variant is designed to capture global spatial correlation, and the removal of the GARN layer reduces the prediction effect considerably, which suggests that not only local spatial correlation but also global implicit spatial correlation should be taken into account in the traffic flow. The w/o LST module has less impact on the model’s overall performance because it only removes the T-GCN module which is mainly concerned with local temporal correlation. It is shown that compared to the MSSTGCN model, the RMSE and MAE metrics of the w/o LST variant for 30-min and 60-min predictions have increased by 11.4%, 21.9%, 3.7%, and 3.8% on the Los-loop dataset, and 9.6%, 22.5%, 2.1%, and 1.7% on the SZ-taxi dataset. However, the RMSE and MAE metrics for 15-min prediction are quite different from those of MSSTGCN. They have increased by 40.7% and 53.9% on the Los-loop dataset, and 51.6% and 60.4% on the SZ-taxi dataset, which indicates that T-GCN is more effective in modeling local temporal correlations. Among all variants, w/o GT (without transformer layer) has the greatest impact. In the w/o GT variant, the transformer layer is used to focus on global temporal correlations. This indicates that it is necessary to consider the global temporal correlations in traffic flow. The w/o PE variant removes positional embedding. As shown in Table 4, the w/o PE variant has the smallest impact. The results of the w/o PE variant are closer to those of MSSTGCN for 30-min and 60-min prediction because multi-head attention can effectively capture long-term temporal dependency in long-term prediction even without positional encoding. However, in short-term prediction, positional encoding is still necessary while focusing on the temporal correlations. The w/o PB variant (without multi-scale module) is unable to learn the hidden periodicity of traffic data, which leads to a decrease in prediction effects, especially in 30-min and 60-min predictions. It can be seen from Table 4 that w/o GT has the worst RMSE metric for 15-min prediction, but for 30-min and 60-min predictions, the RMSEs of w/o PB are the worst. It indicates that the periodic features in traffic flow can not be neglected.

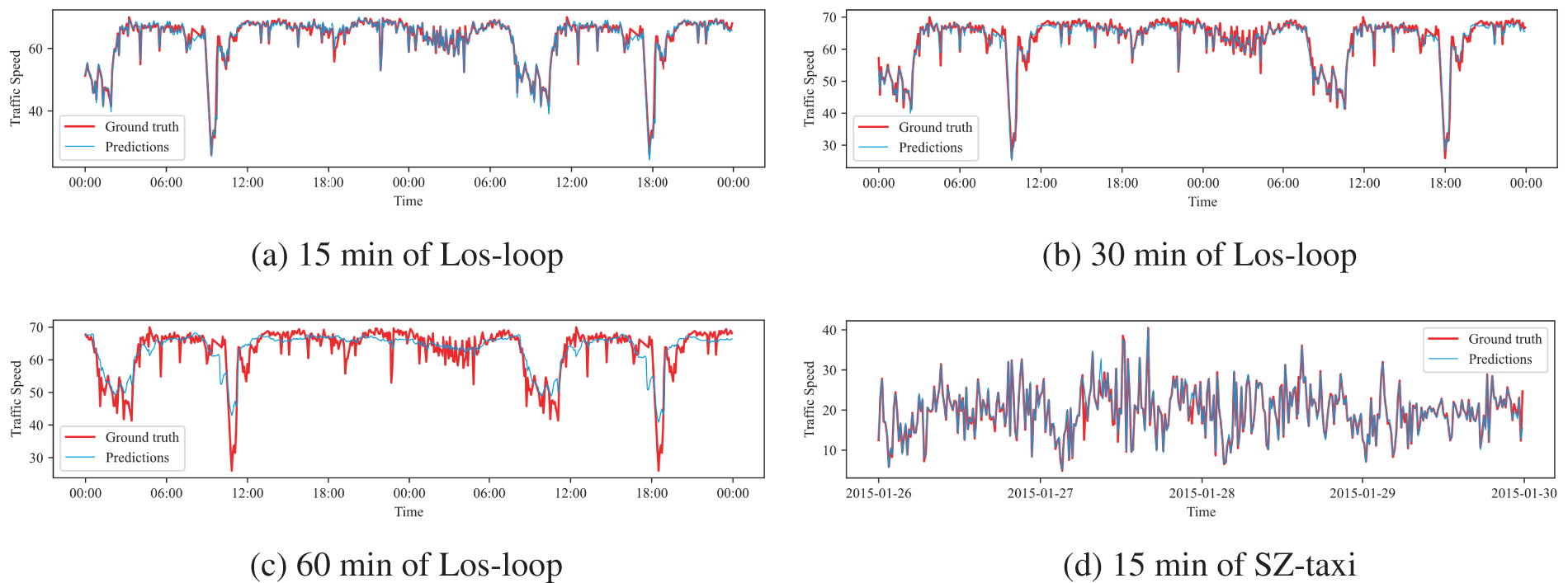

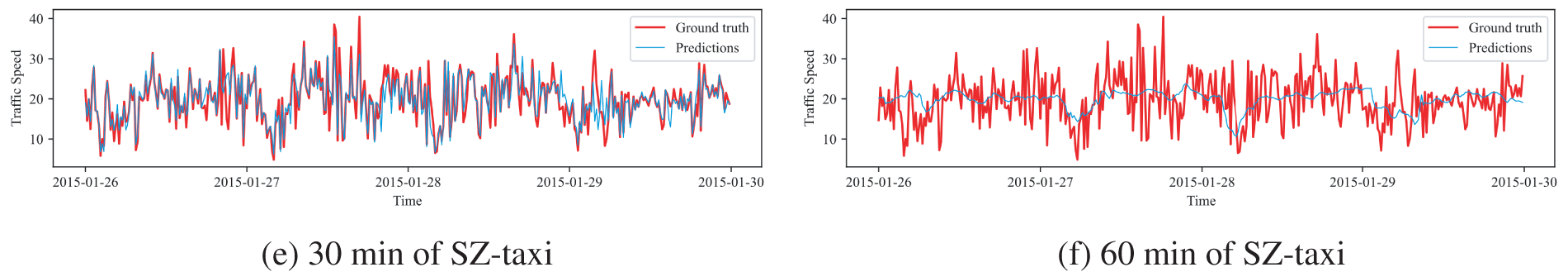

Two roads of the Los-loop and SZ-taxi datasets are selected to visually demonstrate the model’s prediction performance.

We randomly selected two roads from each dataset and visualized the predicted values at various time steps alongside the original values. Fig. 6a–c shows the visualized prediction results on the Los-loop dataset for the whole day from 06 March to 07 March 2012. Fig. 6d–f depicts the visualization of the prediction results on the SZ-taxi dataset from 26 January to 30 January 2015. MSSTGCN demonstrates enhanced accuracy in predicting changes in traffic flow within a short prediction step of 15 min. As the prediction step increases, the results become smoother and smoother. The trends of all prediction curves are consistent with the original curves, which proves the robustness and effectiveness of MSSTGCN performance. In visualizing the 15-min prediction results for the Los-loop dataset, MSSTGCN demonstrates robust adaptation to sudden changes in traffic data and achieves accurate predictions. This shows that MSSTGCN has the potential to predict unexpected situations such as automobile accidents.

Figure 6: Visualization of MSSTGCN results on Los-loop and SZ-taxi datasets with different prediction time steps

In this paper, a spatial-temporal graph convolutional traffic flow prediction model for multi-scale prediction is presented. The traffic data is encoded into a multi-scale form to explore the hidden periodicity. The T-GCN module can capture the local spatial-temporal dependencies. The combination of the graph attention residual network and a transformation layer can capture the global spatial-temporal dependencies. Extensive experiments conducted on four real traffic datasets demonstrate that our model outperforms baseline methods. Ablation experiments further verify the effectiveness of each module. Visualization analysis shows that the model predicts results similar to actual traffic flows and is able to predict roadway emergencies. MSSTGCN performs well in short-term traffic flow prediction and is able to effectively respond to sudden changes in traffic flow, such as accidents, severe weather conditions, and other unforeseen events. This adaptability of MSSTGCN shows a wide range of applications and potential values. In urban traffic management, MSSTGCN can be used to monitor and predict traffic flow in real time, thus helping traffic managers adjust signal timing and traffic flow in time to reduce congestion. In addition, by using the model’s prediction results, reasonable navigation suggestions can be provided to drivers to avoid accident-prone areas and improve driving safety. In Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), MSSTGCN can also be used in conjunction with other sensors and data sources, such as social media data and weather forecasting data, to further enhance the accuracy of prediction. This enables transportation planners to make more scientific decisions when designing infrastructure and optimizing transportation networks. In conclusion, the forecasting capability of MSSTGCN can not only enhance the efficiency of traffic management but also provide important support for the development of smart cities and drive the realization of safer and more efficient transportation systems. In future research, traffic external factors (e.g., weather, number of vehicles, holidays, etc.) that significantly influence the prediction results should be considered and incorporated into the model to better reflect real-world scenarios and achieve more accurate results.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62472149, 62376089, 62202147), Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project (2023BCB04100).

Author Contributions: Xinlu Zong conceptualized the research design, Fan Yu designed the methodology, Zhen Chen took charge of data compilation, Xue Xia verified the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: A publicly available Los-loop, SZ-taxi, METR-LA, and PEMS-BAY datasets were used for analyzing our model. These datasets can be found at https://github.com/lehaifeng/T-GCN and https://github.com/liyaguang/DCRNN (accessed on 06 November 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. W. Zhang, S. Yan, and J. Li, “TCP-BAST: A novel approach to traffic congestion prediction with bilateral alternation on spatiality and temporality,” Inf. Sci., vol. 608, no. C, pp. 718–733, Aug. 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2022.06.080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. H. Li, Y. Chen, K. Li, C. Wang, and B. Chen, “Transportation internet: A sustainable solution for intelligent transportation systems,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 15818–15829, Dec. 2023. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2023.3270749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Z. Li, J. Zhou, Z. Lin, and T. Zhou, “Dynamic spatial aware graph transformer for spatiotemporal traffic flow forecasting,” Knowl. Based Syst., vol. 297, no. 11, May 2024, Art. no. 111946. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. X. Feng, Y. Chen, H. Li, T. Ma, and Y. Ren, “Gated recurrent graph convolutional attention network for traffic flow prediction,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 9, May 2023, Art. no. 7696. doi: 10.3390/su15097696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. X. Qi, G. Mei, J. Tu, N. Xi, and F. Piccialli, “A deep learning approach for long-term traffic flow prediction with multifactor fusion using spatiotemporal graph convolutional network,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 8687–8700, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2022.3201879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. S. V. Kumar and L. Vanajakshi, “Short-term traffic flow prediction using seasonal ARIMA model with limited input data,” Eur. Transp. Res. Rev., vol. 7, no. 3, Jun. 2015, Art. no. 21. doi: 10.1007/s12544-015-0170-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. P. Cai, Y. Wang, G. Lu, P. Chen, C. Ding and J. Sun, “A spatiotemporal correlative k-nearest neighbor model for short-term traffic multistep forecasting,” Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol., vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 21–34, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.trc.2015.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. C. Shuai, W. Wang, G. Xu, M. He, and J. Lee, “Short-term traffic flow prediction of expressway considering spatial influences,” J. Transp. Eng. A-Syst., vol. 148, no. 6, 2022, Art. no. 62. doi: 10.1061/JTEPBS.0000660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. R. Fu, Z. Zhang, and L. Li, “Using LSTM and GRU neural network methods for traffic flow prediction,” in 2016 31st Youth Acad. Annu. Conf. Chinese Assoc. Autom. (YAC), 2016, pp. 324–328. [Google Scholar]

10. K. Cho et al., “Learning phrase representations using RNN rncoder-decoder for statistical machine translation,” in Proc. 2014 Conf. Empir. Methods Natural Lang. Process., 2014, pp. 1724–1734. [Google Scholar]

11. D. Wang, H. Yang, and H. Zhou, “Dynamic spatial-temporal self-attention network for traffic flow prediction,” Future Internet, vol. 16, no. 6, May 2024. doi: 10.3390/fi16060189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. S. He et al., “STGC-GNNs: A GNN-based traffic prediction framework with a spatial-temporal granger causality graph,” Physica A, vol. 623, no. 6, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2023.128913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. B. Cai, Y. Wang, C. Huang, J. Liu, and W. Teng, “GLSNN network: A multi-scale spatiotemporal prediction model for urban traffic flow,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 22, 2022. doi: 10.3390/s22228880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. L. Zhao et al., “T-GCN: A temporal graph convolutional network for traffic prediction,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 21, no. 9, pp. 3848–3858, 2020. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2019.2935152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Y. Li, R. Yu, C. Shahabi, and Y. Liu, “Diffusion convolutional recurrent neural network: Data-driven traffic forecasting,” in 6th Int. Conf. Learn. Rep., ICLR 2018, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

16. S. Guo, Y. Lin, N. Feng, C. Song, and H. Wan, “Attention based spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for traffic flow forecasting,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 922–929, Jul. 2019. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v33i01.3301922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. S. Guo, Y. Lin, H. Wan, X. Li, and G. Cong, “Learning dynamics and heterogeneity of spatial-temporal graph data for traffic forecasting,” IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data. Eng., vol. 34, no. 11, pp. 5415–5428, 2022. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2021.3056502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. X. Zhang, Y. Xu, and Y. Shao, “Forecasting traffic flow with spatial-temporal convolutional graph attention networks,” Neural. Comput. Appl., vol. 34, no. 18, pp. 15457–15479, Sep. 2022. doi: 10.1007/s00521-022-07235-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Y. Yao, B. Gu, Z. Su, and M. Guizani, “MVSTGN: A multi-view spatial-temporal graph network for cellular traffic prediction,” IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput., vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 2837–2849, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TMC.2021.3129796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. G. Wei, “A summary of traffic flow forecasting methods,” J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 82–85, 2004. [Google Scholar]

21. L. Moreira-Matias, J. Gama, M. Ferreira, J. Mendes-Moreira, and L. Damas, “Predicting taxi-passenger demand using streaming data,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 1393–1402, Sep. 2013. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2013.2262376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. J. Wang, P. Shang, and X. Zhao, “A new traffic speed forecasting method based on bi-pattern recognition,” Fluct. Noise. Lett., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 59–75, 2011. doi: 10.1142/S0219477511000405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. X. Luo, D. Li, and S. Zhang, “Traffic flow prediction during the holidays based on DFT and SVR,” J. Sens., vol. 2019, no. 10, pp. 1–10, 2019. doi: 10.1155/2019/6461450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. W. Zhang, G. Yang, Y. Lin, C. Ji, and M. Gupta, “On definition of deep learning,” in 2018 World Autom. Congr. (WAC), 2018, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

25. J. Xu, R. Rahmatizadeh, L. Bölöni, and D. Turgut, “Real-time prediction of taxi demand using recurrent neural networks,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 19, no. 8, pp. 2572–2581, 2018. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2017.2755684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. H. Zhang, G. Yang, H. Yu, and Z. Zheng, “Kalman filter-based CNN-BiLSTM-ATT model for traffic flow prediction,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 1047–1063, 2023. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2023.039274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Y. Zhang, S. Wang, B. Chen, J. Cao, and Z. Huang, “TrafficGAN: Network-scale deep traffic prediction with generative adversarial nets,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 219–230, 2021. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2019.2955794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Z. Chen et al., “Spatial-temporal short-term traffic flow prediction model based on dynamical-learning graph convolution mechanism,” Inf. Sci., vol. 611, pp. 522–539, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2022.08.080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Z. Su, T. Liu, X. Hao, and X. Hu, “Spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for traffic flow prediction considering multiple traffic parameters,” J. Supercomput., vol. 79, no. 16, pp. 18293–18312, Nov. 2023. doi: 10.1007/s11227-023-05383-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. J. Wang, W. Wang, X. Liu, W. Yu, X. Li and P. Sun, “Traffic prediction based on auto spatiotemporal multi-graph adversarial neural network,” Physica A, vol. 590, no. 5, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2021.126736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. J. Zhao et al., “2F-TP: Learning flexible spatiotemporal dependency for flexible traffic prediction,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 15379–15391, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2022.3146899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. X. Zhang et al., “Traffic flow forecasting with spatial-temporal graph diffusion network,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 35, no. 17, pp. 15008–15015, May 2021. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v35i17.17761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. A. Vaswani et al., “Attention is all you need,” in Proc. 31st Int. Conf. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 2017, pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

34. J. Bai et al., “A3T-GCN: Attention temporal graph convolutional network for traffic forecasting,” ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf., vol. 10, no. 7, 2021. doi: 10.3390/ijgi10070485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. A. Oluwasanmi, M. U. Aftab, Z. Qin, M. S. Sarfraz, Y. Yu and H. T. Rauf, “Multi-head spatiotemporal attention graph convolutional network for traffic prediction,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 8, 2023. doi: 10.3390/s23083836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. X. Dong, W. Zhao, H. Han, Z. Zhu, and H. Zhang, “MTESformer: Multi-scale temporal and enhance spatial transformer for traffic flow prediction,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 47231–47245, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3381987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. W. Chai, Q. Luo, Z. Lin, J. Yan, J. Zhou and T. Zhou, “Spatiotemporal dynamic multi-hop network for traffic flow forecasting,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 14, 2024. doi: 10.3390/su16145860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. S. Modi, Y. Lin, L. Cheng, G. Yang, L. Liu and W. Zhang, “A socially inspired framework for human state inference using expert opinion integration,” IEEE-ASME T MECH, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 874–878, 2011. doi: 10.1109/TMECH.2011.2161094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Y. Yu, H. Yin, and Z. Zhu, “Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks: A deep learning framework for traffic forecasting,” in Proc. 27th Int. Joint Conf. Artif. Intell. (IJCAI), 2018, pp. 3634–3640. [Google Scholar]

40. C. Zheng, X. Fan, C. Wang, and J. Qi, “GMAN: A graph multi-attention network for traffic prediction,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 1234–1241, Apr. 2020. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v34i01.5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. B. Oreshkin, A. Amini, L. Coyle, and M. Coates, “FC-GAGA: Fully connected gated graph architecture for spatio-temporal traffic forecasting,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 9233–9241, 2021. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v35i10.17114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Z. Pan, Y. Liang, W. Wang, Y. Yu, Y. Zheng and J. Zhang, “Urban traffic prediction from spatio-temporal data using deep meta learning,” in Proc. 25th ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min. (KDD), 2019, pp. 1720–1730. [Google Scholar]

43. Z. Wu, S. Pan, G. Long, J. Jiang, and C. Zhang, “Graph WaveNet for deep spatial-temporal graph modeling,” in Proc. Twenty-Eighth Int. Joint Conf. Artif. Intell. (IJCAI), 2019, pp. 1907–1913. [Google Scholar]

44. Z. Wu, S. Pan, G. Long, J. Jiang, X. Chang and C. Zhang, “Connecting the dots: Multivariate time series forecasting with graph neural networks,” in Proc. 26th ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min. (KDD), 2020, pp. 753–763. [Google Scholar]

45. X. Huang, Y. Lan, Y. Ye, J. Wang, and Y. Jiang, “Traffic flow prediction based on multi-mode spatial-temporal convolution of mixed hop diffuse ODE,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 19, 2022. doi: 10.3390/electronics11193012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools