Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

APWF: A Parallel Website Fingerprinting Attack with Attention Mechanism

1 College of Computer Science and Technology, Changchun University, Changchun, 130022, China

2 School of Cyberspace Science and Technology, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, 100081, China

3 Key Laboratory of Intelligent Rehabilitation and Barrier-Free for the Disabled, Changchun University, Changchun, 130022, China

4 China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, Beijing, 100083, China

5 Key Laboratory of Mobile Application Innovation and Governance Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Beijing, 100846, China

* Corresponding Author: Yi Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 2027-2041. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.058178

Received 06 September 2024; Accepted 07 November 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

Website fingerprinting (WF) attacks can reveal information about the websites users browse by de-anonymizing encrypted traffic. Traditional website fingerprinting attack models, focusing solely on a single spatial feature, are inefficient regarding training time. When confronted with the concept drift problem, they suffer from a sharp drop in attack accuracy within a short period due to their reliance on extensive, outdated training data. To address the above problems, this paper proposes a parallel website fingerprinting attack (APWF) that incorporates an attention mechanism, which consists of an attack model and a fine-tuning method. Among them, the APWF model innovatively adopts a parallel structure, fusing temporal features related to both the front and back of the fingerprint sequence, along with spatial features captured through channel attention enhancement, to enhance the accuracy of the attack. Meanwhile, the APWF method introduces isomorphic migration learning and adjusts the model by freezing the optimal model weights and fine-tuning the parameters so that only a small number of the target, samples are needed to adapt to web page changes. A series of experiments show that the attack model can achieve 83% accuracy with the help of only 10 samples per category, which is a 30% improvement over the traditional attack model. Compared to comparative modeling, APWF improves accuracy while reducing time costs. After further fine-tuning the freezing model, the method in this paper can maintain the accuracy at 92.4% in the scenario of 56 days between the training data and the target data, which is only 4% less loss compared to the instant attack, significantly improving the robustness and accuracy of the model in coping with conceptual drift.Keywords

With the gradual development of Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETS), more and more research is being done to provide privacy protection schemes [1,2] with strong anonymity to avoid eavesdropping or censorship. Among the existing tools and schemes, the Tor network (The onion router), which has millions of active users, provides privacy protection for users and has become a well-known representative of low-latency anonymous communication systems. The forwarding strategy of Tor network’s multihop links can effectively hide the specific traffic content. Still, it has limitations in hiding the direction of data flow, timestamps, and other key features, which are insufficient to defend against traffic analysis attacks. This weakness is based on the successful implementation of WF attack [3,4]. The study of WF attacks can be used as a means to monitor anonymous communication networks to avoid the malicious influence caused by criminals using the Tor network. This will help ensure network security and improve the effectiveness of network supervision and governance.

In recent years, the classical WF attack model has encountered the following challenges: i) Inadequate adaptability to small samples: Traditional deep models need to collect hundreds of training samples for each monitored website to achieve high-quality classification. However, when training samples are scarce, neural networks face the problem of overfitting. ii) Concept drift: The unpredictability of website content causes traffic patterns to change over time. Juarez et al. [5] noted that most websites are updated regularly, leading to a significant decline in the accuracy of the trained model when applied to varying traffic. This phenomenon is termed concept drift [6], suggesting that existing models struggle to address the influence of time on accuracy. Hence, the crucial technical challenge lies in how to effectively use a small number of samples to alleviate the impact of concept drift on model accuracy. The main contributions of the study can be summarized as follows:

• First, we propose an APWF model, which combines convolutional neural network (CNN) and bidirectional gated cyclic unit (BiGRU) to construct a parallel network architecture for attack. By integrating packet timing and spatial features, website fingerprint is customized, and channel attention mechanism (CBAM) is introduced to enhance the feature learning ability, which effectively reduces the training data demand and optimizes the time efficiency of model training.

• Then, to deal with concept drift, we design APWF fine-tuning method based on transfer learning. This method uses a small amount of data to train the optimal classification model. When the traffic classification task is updated, the model parameters are fine-tuned by transfer learning to better adapt to the new website content, thus alleviating the concept drift phenomenon.

2.1 Website Fingerprinting Attack

Manual feature design. In the early approaches to Tor anonymity traffic analysis, researchers mainly designed classification tasks on manually extracted traffic features by machine learning models [7–10]. However, manual traffic feature extraction engineering is highly dependent on expert knowledge, time-consuming and laborious to extract, and is bound to be limited. In cases where the traffic features are not obvious, the amount of data is huge, and different protocols change, etc., it is impossible to effectively respond to the defense against specific features.

Automated feature extraction. Deep learning algorithms are suitable for automatically performing feature extraction from raw sequences, can effectively counter existing WF defense methods, and have an explorable potential for application. Sirinam et al. [11] proposed a deep fingerprint (DF) attack model in 2018, which created a deep network by introducing multiple convolutional layers and batch normalization, and achieved 98% accuracy in a closed-world of 95 websites, existing defenses such as WTF-PAD [12] and Walkie-Talkie [13] were overcome. However, this method required a large number of instances and its performance significantly decreased when training samples were reduced. Bhat et al. [14] proposed the Var-CNN model, optimized the deep neural networks (DNN) architecture and integrated direction, timing information and a few manual features. Although it performed well on small datasets, it still had problems such as unstable performance of time features and dependence on manual features. Siriam et al. [15] proposed that Triplet Fingerprinting (TF) solves the problem of data scarcity by extracting features from triplet networks to train k-NN (k-nearest neighbor) classifiers, which is limited by training complexity and task adaptability. The adaptive fingerprint (AF) proposed by Wang et al. [16] adopts an adversarial domain adaptive method. Although the performance exceeds TF and the training time is shorter, the advantages are not obvious when the sample size is limited.

2.2 Website Fingerprint Defense

. In order to counter the performance of WF attacks, many WF defense measures based on filling, imitation and regularization are proposed to obfuscate the traffic and hide the information characteristics in it. This paper uses the most advanced low-latency defense WTF-PAD to protect data privacy and evaluates its impact on WF attack methods. WTF-PAD is a kind of adaptive fill (AP) specifically for Tor proposed by Juarez et al. [12]. It compensates for the AP deficiency of adding virtual packet fill only when channel utilization is low by adding a state machine. When a user makes a request, WTF-PAD calls the defense server to add a fake burst feature between successive large-delay bursts, thus obfuscating the true page size. WTF-PAD can effectively defend against multiple attack modes at a moderate bandwidth overhead (about 50%).

This paper uses the threat model of WF works in earlier literature [11,14]. In Fig. 1, the WF attacker is set up as a local passive eavesdropper. Being a local network layer attacker means that the attacker is limited to collecting encrypted traffic transmitted between the client and the Tor entry node. The technical means available for WF attacks are limited to listening to network packets. You have no permission to inject, modify, delay, or discard traffic. The WF attacker cannot directly read the IP (Internet Protocol) address and plaintext content of the message, and therefore cannot determine the destination website of the client.

Figure 1: The threat model of the website fingerprinting attack

This paper assumes that the attacker can accurately identify and distinguish between the start and end of network traffic and the pure traces produced by the victim. WF attack protection nodes support the distribution of traffic to encrypted connections of different websites, and can distinguish between Tor (The Onion Router) and TLS (Transport Layer Security) traffic, so this paper can analyze traffic based on this assumption. In addition, previous studies have mainly focused on website identification under the single-label assumption, failing to reflect the real behavior of Tor users. In practice, users may be visiting multiple sites at the same time, resulting in overlapping access times. The multi-label scenario has been explored in some studies [17] and will not be discussed in depth.

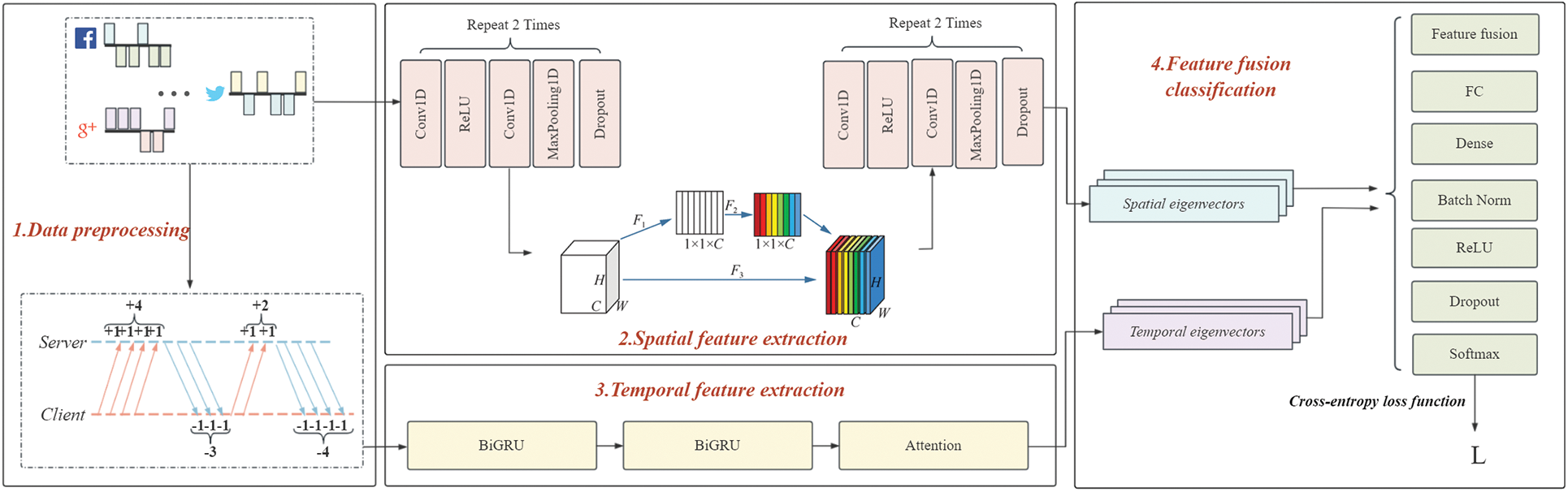

The architecture of WF attack model APWF is shown in Fig. 2. The attack model consists of four steps: data preprocessing, spatial feature extraction, temporal feature extraction and feature fusion classification. In the data preprocessing phase, we extract the accumulated data package sequence from the training dataset as the input data of the time feature network. At the same time, the orientation information of the original training package is used as the input of the spatial feature network. Secondly, we use parallel spatiotemporal feature network architecture to learn and extract spatiotemporal features of traffic data, respectively. In the stage of feature fusion classification, we use parameters to flexibly adjust the weight of spatio-temporal features. Thus, more abundant feature information can be extracted from the limited traffic data, so as to obtain more accurate and reliable recognition results.

Figure 2: Architecture of the APWF attack model

Data preprocessing: A local attacker first accesses a specific collection of websites and collects a sequence of packets. The attacker extracts the packet orientation sequence D = {d1, d2, ..., dn}, di ∈ {−1, +1}. di = −1 indicates the data packets sent from the web server to the user, and di = 1 indicates the data packets sent from the user to the web server. Thus, an attacker can obtain a direction vector x1, i.e., <d1, d2, ..., dn>. The traffic generated by accessing a web page through Tor can be viewed as one-dimensional time series data. In the process of transmission, the media data forms a large packet, while the text data is sparse, indicating that there are contextual features in the packet sequence. One request packet usually corresponds to multiple response packets, and this clear sequential feature is an important part of a website’s fingerprint. In order to extract timing features and control training time, the attacker preserves symbolic representations of continuous messages, using message numbers instead of numerical values. After processing, the sequence length is reduced by more than 60% on average, and a new sequence vector x2 is formed. We extract cumulative direction packets as time series features and combine them with spatial features to effectively reveal data transmission relationships such as web page resource loading.

Spatial feature extraction: In the spatial feature extraction module, we select 8 convolution layers, each of which is followed by an activation layer. In order to avoid the loss of feature information, four composite blocks are used to refine and eliminate the redundancy of features, and the maximum pooling layer and discard layer are added after every two convolution layers in each composite block. At the same time, CBAM attention mechanism [18] is introduced to weight space features of different scales to make the model pay more attention to key features. By explicitly modeling the dependency between feature channels, CBAM automatically identifies and dynamically adjusts the importance of each feature channel, thus emphasizing the features that have a greater impact on classification results. After the input is compressed, excited, and calibrated, it is passed on to the next convolutional layer to help the model learn important spatial features. The channel attention module processes an input of dimension C × H × W (where C is the number of channels) as follows:

Compression process: The module performs global mean pooling for each channel, calculates the average value of each channel, extracts key information, and generates a compressed data z of dimension 1 × 1 × C. The value of the c channel is the mean of all points on the channel.

Excitation process: Firstly, dimension transformation is performed on the compressed data z. Through the fully connected layer and the activation function, z is mapped to the smaller dimension 1 × 1 × (C × r) (where r is the compression ratio). Then, through the full connection layer and activation function, the dimension is restored to 1 × 1 × C, and the calibration vector sc is obtained. The calculation process of the calibration vector sc reflects the correlation between channels and is explicitly modeled.

Calibration process: The calibration vector sc is used to re-calibrate the original feature matrix. Specifically, sc is multiplied with the corresponding channel element by element to achieve the reweighting of the feature matrix and obtain the output feature

In summary, the channel attention module takes U as input and outputs

Temporal feature extraction: In Web data interaction, there is an obvious correspondence between request messages and multiple response messages, so the website fingerprint shows significant time characteristics. We employ BiGRU to capture the time dependence of traffic data and process both forward and backward information of input sequences to enhance the representation of time features. By combining the attention mechanism, the grouping differences are further highlighted. In the BiGRU model, we omit some spatial features, focus on time features, and reduce sample length by cumulative summation to improve training efficiency.

Feature fusion classification: Temporal and spatial features play different roles in recognition. Therefore, in this paper, we carefully design the feature fusion strategy. Specifically, we define a fused feature vector

We input the fused feature vector F into the Softmax classifier and use the Softmax activation function to calculate the probability distribution of each traffic category. The formula is shown as:

where Pi denotes the probability that an input session is recognized as the ith traffic category; xi is the score of the corresponding traffic category. Ultimately, we select the category with the largest probability value as the recognition result of the model.

4.2 A Scheme to Deal with Concept Drift Based on a Fine-Tuning Mechanism

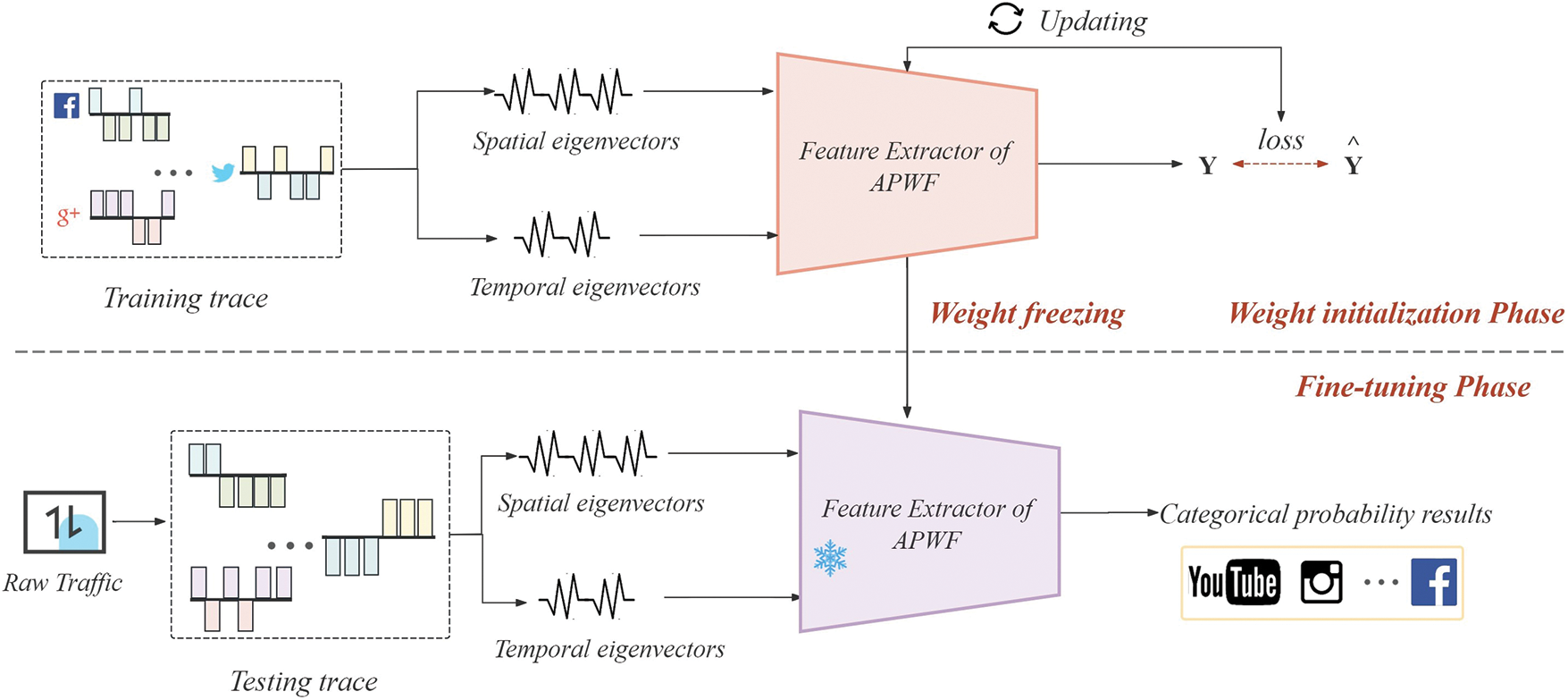

The fine-tuning mechanism of transfer learning is very important to deal with the problem of concept drift. It enables the pre-trained model to be further tuned and optimized on the target dataset to accommodate specific variations and conceptual drifts. Therefore, we design a fine-tuning method based on Transfer learning (APWF) to optimize the performance of deep learning models on new tasks, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: APWF fine-tuning method architecture

In the training phase, we construct a concatenated feature extractor incorporating spatio-temporal features. We pre-train the feature extractor using historical data to ensure that the model can fully learn the intrinsic laws of the data so that the model can classify the traffic.

In the attack phase, the attacker captures the unknown traffic data between the user and the ingress node. These unknown flows are fed into the trained classifier, and the target websites of these flows are inferred through the inference of the trained WF classifier.

During the fine-tuning phase, the attacker freezes the model parameters of the feature extractor. The hyperparameters of the final layers of the model are then adjusted using only a small amount of labeled data for each category of the new task, enabling the feature extraction capabilities of the fine-tuned pre-trained model to extract robust features.

By utilizing the APWF method, we can largely mitigate the negative effects of problems such as insufficient data or category mismatch and improve the model’s performance on the new task.

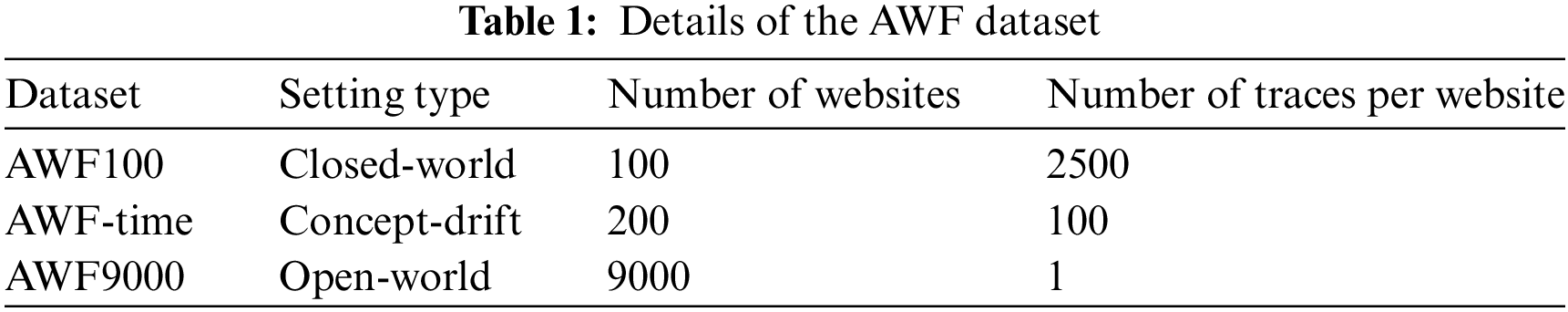

In order to effectively evaluate the performance of the proposed model, three representative and widely used datasets were selected for experimental comparison. The three datasets are AWF dataset [19], DF dataset [11] and Wang dataset [8]. The description of the dataset is shown in Table 1, where AWF-time contains 6 groups of data, which are data packets collected from the same website at different intervals.

To evaluate the performance of our approach in defense scenarios, we employ the undefended DF dataset [11], the undefended Wang dataset [8], and the WTF-PAD dataset [12] in the closed-world only.

According to the previous WF literature [20], using only true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR) to evaluate the model may be misleading due to data imbalance. In this study, the accuracy rate, accuracy rate and recall rate are used to measure the model performance comprehensively, so as to avoid the deviation of the benchmark rate. The three evaluation metrics are defined below:

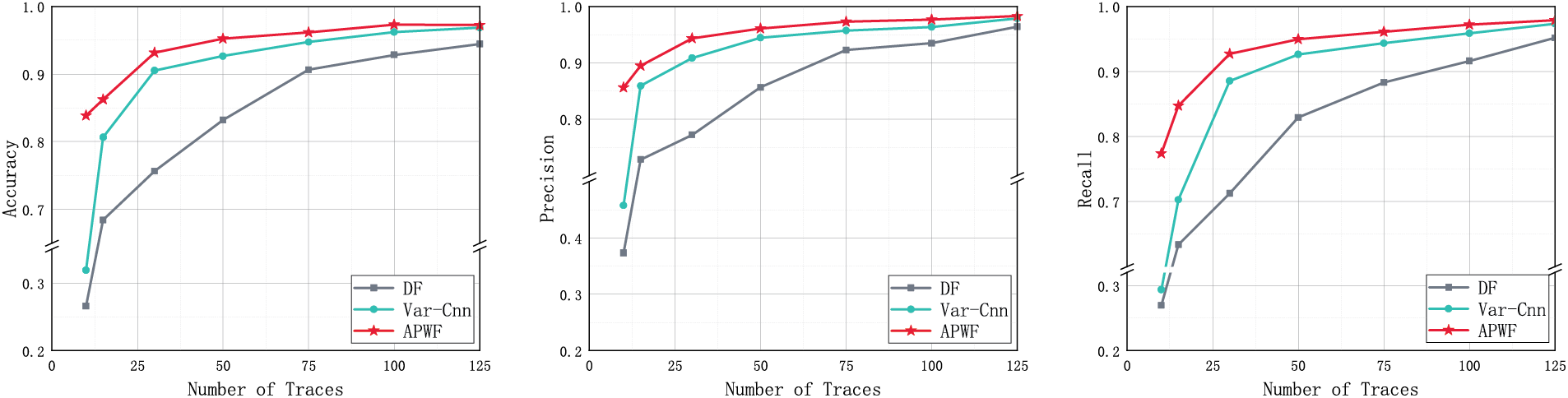

Setting. In order to ensure the effectiveness of the experiment, we extracted the attack stage dataset from the AWF100 dataset, and extracted different numbers of samples for each website on the basis of 100 websites to form a training set. Data that does not overlap with the training sample is selected as the test sample, and 70 data are randomly selected from each website, which is mutually exclusive with the pre-training data. Fig. 4 shows the changes in the three comparison model evaluation metrics on the AWF100 dataset as the monitoring training sample increases.

Figure 4: Closed-world APWF evaluation from left to right: accuracy, precision, recall

Result. Performance test results show that our proposed model is superior to DF and Var-CNN methods in classification performance, and the performance advantage becomes more obvious with the reduction of training data. For the few-shot monitored set test, even if each site contains only 10 traces, the APWF scheme can achieve 85% accuracy, while the DF and Var-CNN scheme evaluation indexes are lower than 50%. When the number of tracks per site increased to 125, the accuracy of the APWF scheme increased to 98%, verifying the robustness and generalization ability of the model. In-depth analysis shows that more abundant traffic information can be learned with mixed features. When the sample size is small, with the increasing sample size, the fault tolerance of the model to trajectory features is improved, and the classification accuracy is further improved.

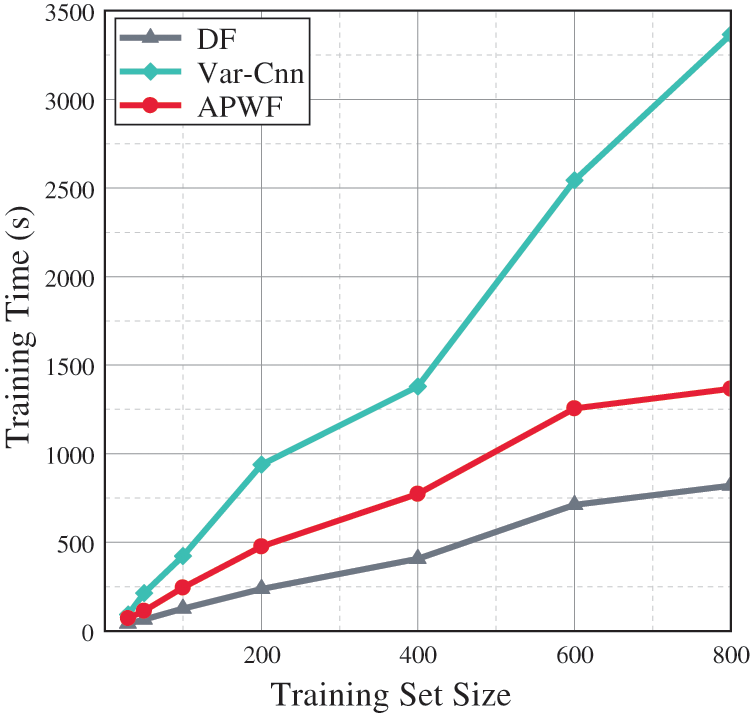

Setting. To evaluate the efficiency of different methods, we compare the pre-training durations of the three methods. The time cost of training the same monitored samples is shown in the Fig. 5.

Figure 5: APWF model training time overhead

Result. As can be seen from Fig. 5, the training time of Var-CNN is much higher than the other two methods, because it needs to train two extended causal Resnets, and the network structure is more complex, resulting in a large time overhead. In contrast, the training time of our proposed model is significantly lower than that of Var-CNN and only slightly higher than DF. This is because the computational resources and synchronization mechanisms required for APWF to process the two paths in parallel increase computational complexity and coordination time, resulting in a longer overall response time. In order to control the time cost, we carried out data processing on the timing features in the follow-up experiment. Considering classification accuracy and training time cost comprehensively, our method has obvious advantages compared with DF and Var-CNN in pursuing efficient and accurate classification tasks, which not only improves classification performance, but also optimizes training time.

Evaluating attack performance in open-world environments is critical because attackers must accurately distinguish whether traffic traces originate from monitored websites. This setting is more challenging than the closed-world environment because the attacker cannot know all possible websites in advance. Therefore, our research focuses on the binary classification problem, i.e., determining whether traffic traces are monitored.

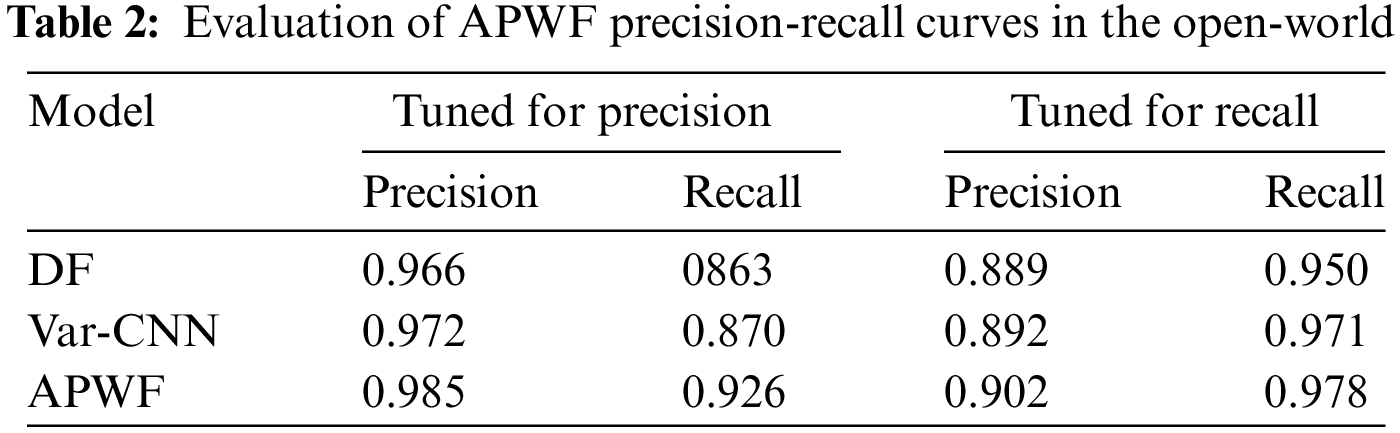

Setting. We use precision-recall curves to simulate more realistic attack scenarios as a key measure of attack performance. Table 2 shows the precision-recall curves for attacks using similar but mutually exclusive datasets in the open-world.

Result. Table 2 shows the highest precision and recall performance of the three WF attack models on the AWF9000 dataset. The results show that the APWF model performs best in accuracy and recall. When pursuing high precision, the APWF scheme demonstrates excellent performance, with precision and recall as high as 0.98 and 0.92, respectively, while when aiming at high recall, APWF also performs well, with accuracy and recall as high as 0.90 and 0.97, respectively. This performance advantage is mainly because APWF can learn the sequential packet dependencies in the traffic traces, thus maintaining feature integrity, which improves the classification performance.

5.6 Website Fingerprint Attack Against Defense

To enhance the robustness and applicability of the model in real scenarios, this study adopts the APWF scheme to compare and analyze the performance of traffic traces under WTF-PAD [12] defense mechanisms.

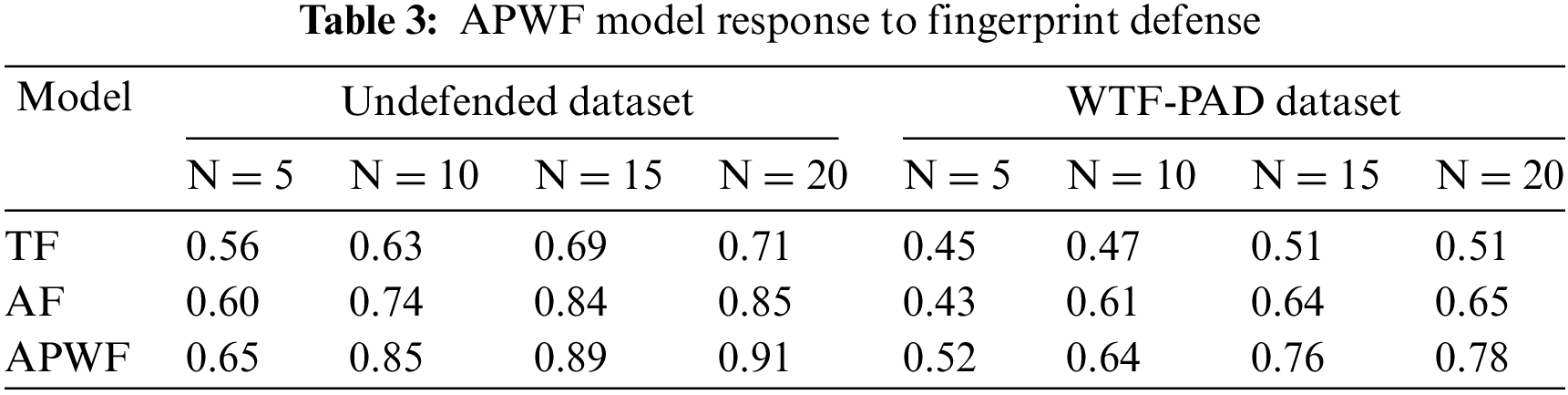

Setting. We selected two datasets, DF and Wang, for our experiments, utilizing the Wang dataset for pre-training, while the DF dataset is used for subsequent model training and testing efforts.

In the pre-training phase, we select 25 samples from each website in the Wang dataset for initial training of the model. After entering the training phase, we selected a different number of samples (N = 1, 5, 10, 15, 20) for each website in the DF dataset to fine-tune the model to explore the effect of different sample sizes on the model performance. In the testing phase, we then thoroughly evaluated the performance of the APWF scheme using 70 samples from each website. The results of the classification accuracy test under the few-shot WF attack setting with defense traces are shown in Table 3.

Result. According to the experimental data in Table 3, the classification accuracy of the dataset defended by WTF-PAD is lower than that of the undefended dataset in a closed-world with few WF attacks. However, with the increase of new collection tracks, the classification accuracy increases regardless of defense. In particular, for new target samples, APWF schemes show higher classification accuracy than TF and AF methods. In the case of N = 1, the training data is too scarce, which makes the training effect of the model almost meaningless. Therefore, this setting was not included in the experimental comparison in this study. While, in the 20-shot scenario, APWF achieved 91% accuracy on undefended datasets, TF and AF were 71% and 85%, respectively. In the face of WTF-PAD defense trajectory dataset, APWF is still 78%, while TF and AF are only 51% and 65%. This fully validates the excellent performance of APWF in defense trajectory classification tasks. TF and AF models do not fully consider the size, sequence and time stamp of packets when analyzing network traffic, so their resistance to defense strategies is less than that of APWF. This shows that by dig-ging deeper into the traffic for more potential information, attackers can effectively identify and exploit these vulnerabilities to break through defense mechanisms.

5.7 Evaluation of Concept Drift

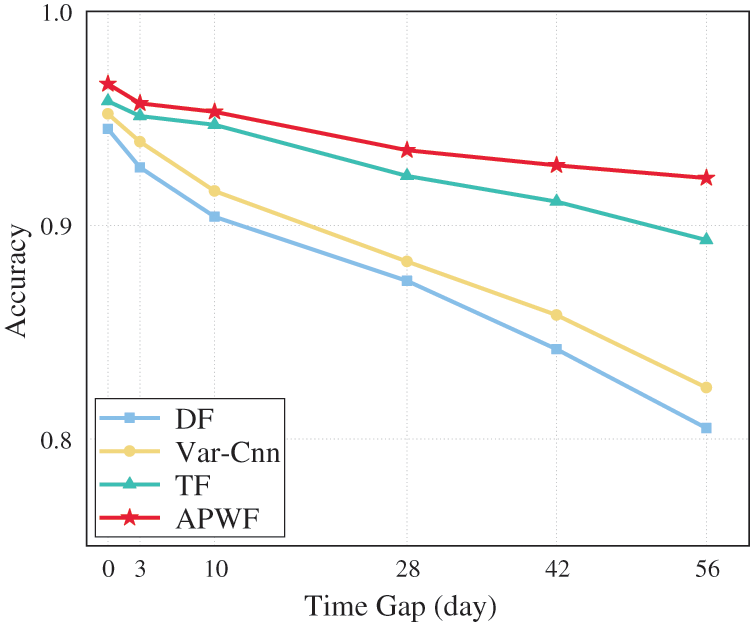

Two independent experiments were conducted to solve the problem that WF attack performance is affected by concept drift in a closed-world environment. The first experiment compares the performance of APWF scheme and classical attack method in coping with concept drift. The second experiment evaluated the effect of different fine-tuning sample sizes on concept drift treated by APWF schemes.

Setting. The closed-world scenario is built on the AWF200 dataset to simulate data constraints. The experiment simulates that an attacker trains the model with only the initial dataset and tests it on a new dataset after an interval of time. The performance changes of each attack model affected by concept drift are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: APWF scheme performance affected by concept drift

Result. The experiment shows that the classification accuracy of anonymous trajectory decreases with the increase of time interval. For example, from 3 to 56 days, the classification accuracy of DF, Var-CNN, and TF generally declined. The APWF method performs better in different time intervals and continuous sampling scenarios, and its classification accuracy is 1.3% and 3% higher than that of optimal TF. APWF improves performance by fine-tuning a pre-trained deep WF model, while TF needs to train a triad network to generate feature embedders. The classical methods DF and Var-CNN showed a sharp decline in performance in time lapse, with DF performing the worst when dealing with concept drift, with a 14% drop in accuracy. In contrast, APWF showed strong generalization ability, and the classification accuracy remained above 92% after 2 months. APWF adjusts the model architecture by updating the trajectory in a small amount to improve the ability of “learning classification”, so that the attacker can maintain a high attack accuracy with only a small number of samples, thus effectively reducing the attack cost.

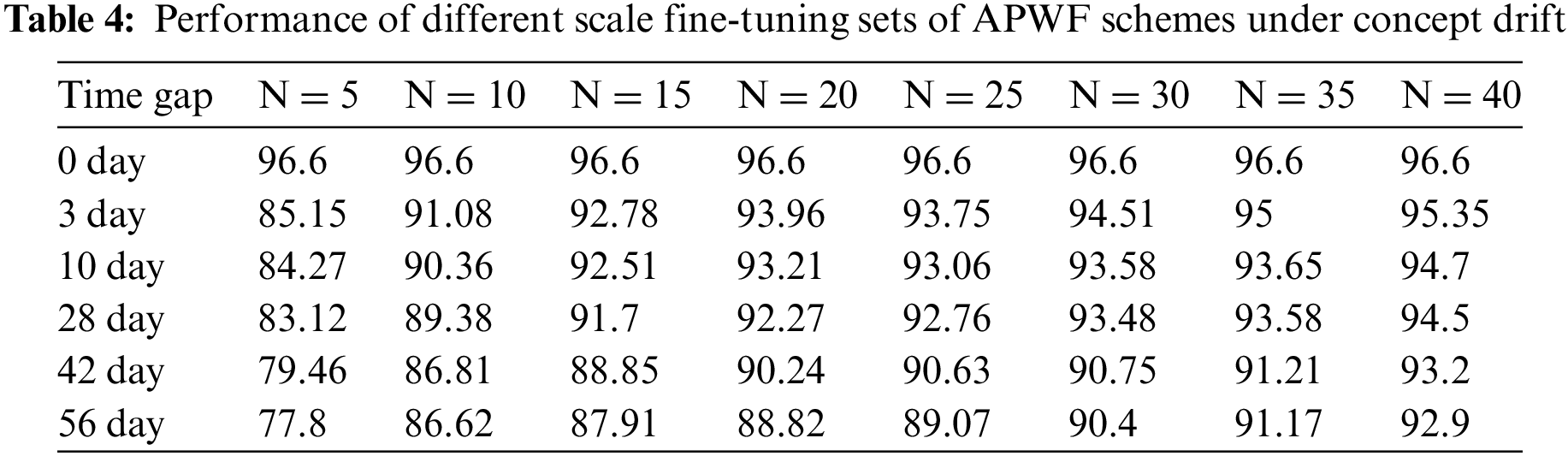

Setting. In this experiment, we select N = 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 examples as fine-tuned datasets for each site from five concept drift datasets respectively, and then design an APWF scheme to conduct experiments on datasets with different time intervals. The results are shown in Table 4.

Result. As shown in Table 4, the overall performance of the APWF scheme, when challenged by concept drift, shows a decreasing trend over time. When N ≥ 15, the classification accuracy of the APWF scheme drops only slightly in the first 28 days and remains almost constant from 10 to 28 days; after 56 days, when N = 5, the accuracy further drops to 77.8%. However, when N = 40, the classification accuracy still reaches more than 92%, which is only a 4% drop compared to 56 days ago. From this, it can be concluded that after an attacker finishes pre-training the model for a specific monitored website, they only need to collect 30 examples for each target website over a long period to ensure that the APWF classification accuracy is above 90%, thus effectively reducing the attack cost of collecting a large amount of data to re-train the model. The experiment shows that transfer learning can effectively reduce the negative impact of concept drift.

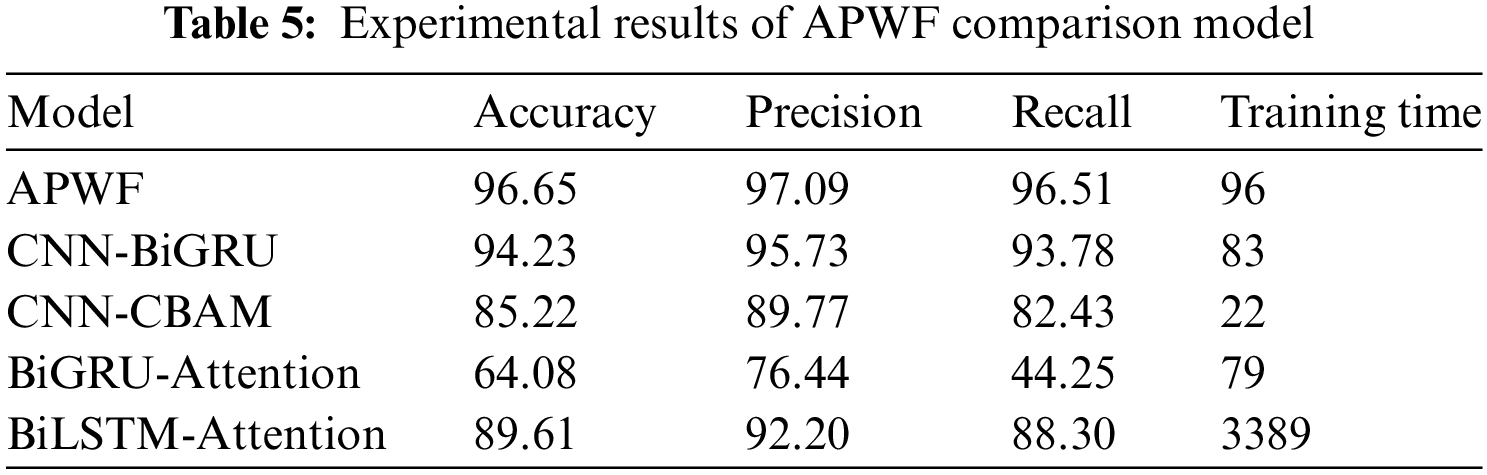

5.8 Model Architecture Ablation Study

Setting. To deeply explore the specific impact of features and APWF model architecture on classification accuracy, we designed four comparison experiments to evaluate different model components, and the results are shown in Table 5.

(1) CNN-BiGRU model. First, we examined the CNN-BiGRU model without using the attention mechanism in the spatial feature extraction branch to observe the effect of the attention mechanism on the model performance.

(2) CNN-CBAM model. Next, we compare the CNN-CBAM model using only the spatial feature extraction branch to compare the contribution of a single feature to model learning.

(3) BiGRU (Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit)-Attention model. Similarly, we constructed the BiGRU-Attention model using only temporal features to extract branches.

(4) BiLSTM (Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory)-Attention model. Finally, to compare the effects of different recursive units, we designed the BiLSTM-Attention model, in which the GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit) at the data flow layer is replaced with an LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory), and the update gates are adjusted to be oblivion gates and exit gates accordingly.

Result. With the experimental results presented in Table 5, we can find the following conclusions:

First, the CNN-BiGRU model without attention is less accurate than the APWF model that uses the channel attention mechanism on the spatial feature branches. This result verifies the effectiveness of the attention mechanism in feature extraction, and by introducing the attention mechanism, the model can capture the key information of the data more accurately.

Second, classification results using only a single feature are significantly lower than those using both direction and time features. Although previous studies have suggested that directional features are more effective, experiments have shown that combining temporal features with spatial features can extract more critical information. Although the BiGRU-Attention model using only time features has slightly lower performance than the CNN-CBAM model using directional features, it still shows strong learning ability and can mine useful information from the sequence of packet relations.

Finally, we compare the performance of APWF and BiLSTM-Attention. The experimental results show that the APWF model performs better and has a significant advantage in time cost. This may be because GRU has a relatively simple structure and faster convergence speed, giving it an advantage in training small-scale datasets.

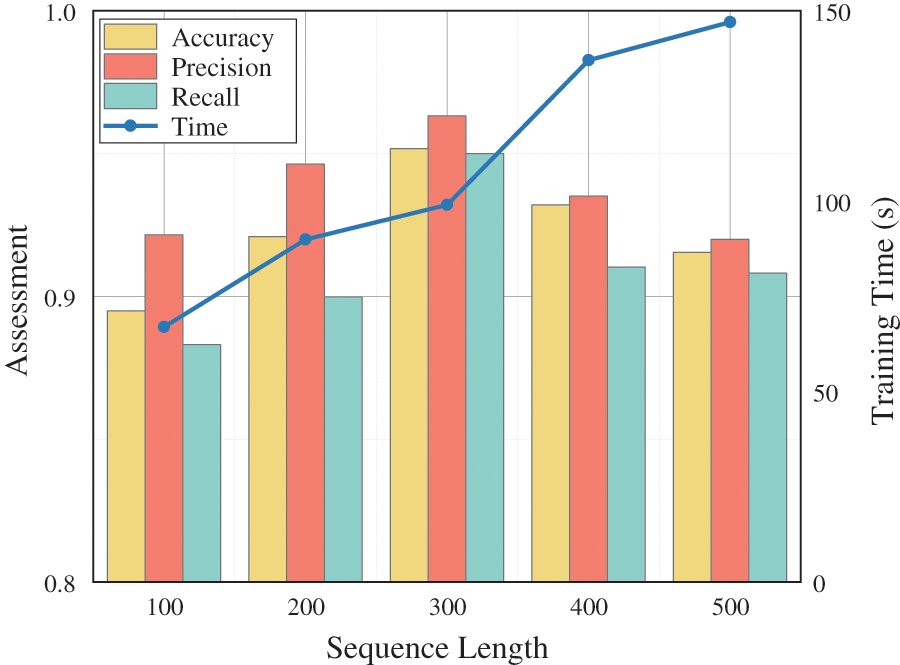

5.9 Temporal Vector Length Ablation Study

Setting. In order to control the reasonable time cost, we evaluate the performance impact of different lengths for APWF attacks for the length L2 taken by the timing vectors. The length range of the timing sequence L2 covers a wide range of lengths from 100 to 500. Fig. 7 shows the accuracy of the modeled attacks with different length settings.

Figure 7: Timing vector length L2 ablation evaluation

Result. Through the attack accuracy results shown in Fig. 7, we observe that the APWF model performs best when the timing length is 300, achieving the optimal attack, taking into account the evaluation index and time cost. When the sequence length is short (100 or 200), the BiGRU model lacks accuracy due to insufficient feature information. When the length is increased to 400 or 500, more information can be captured, but the model is overfitted and the time cost increases dramatically. Therefore, in order to balance the effectiveness of the attack and the computational cost, we set the length of the timing vector L2 to 300 as the key parameter for the input of the BiGRU-Attention branch. It should be mentioned that the difference in packet length between different websites mainly depends on the content type of the website, the number and frequency of requests, the presence of video streams, and caching. The L2 length should be flexibly set according to different application scenarios to adapt to the differences in packet length.

This paper introduces an innovative APWF method, which is applied in the field of website fingerprint attack. APWF model adopts parallel network structure to capture spatial features and time sequence details of data packets efficiently and automatically. The directional features are learned by convolutional neural network and CBAM reinforcement, and the temporal sequences are captured by BiGRU-Attention network structure. To address dynamic changes in statistical patterns, we developed APWF fine-tuning mechanisms that are more realistic and challenging than existing WF attack studies, demonstrate superior performance and stability, and can be effectively processed in both closed-world and open-world where training data is scarce. The results show that when there is a 56-day interval between training and testing data, APWF achieves 92.4% classification accuracy, which is 3% higher than TF method. The research shows that transfer learning can effectively mitigate the impact of concept drift on the accuracy of attack models, and make website fingerprint recognition more practical in the real world. We will delve into the scalability of the technology to address the complex challenges that come with large-scale deployments. At the same time, the successful application of APWF has also prompted the defense side to continuously improve its defense strategy and technology level to cope with the increasingly complex cyber attack means. This may include the introduction of obfuscation techniques and the use of randomised packets to reduce predictability.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the editor-in-chief, editor, and reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Funding Statement: This work has been partially supported by the National Defense Basic Scientific Research Program of China (No. JCKY2023602C026) and the funding of Key Laboratory of Mobile Application Innovation and Governance Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (2023IFS080601-K).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: methodology conception and design: Dawei Xu, Min Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Min Wang, Yue Lv, Moxuan Fu, Yi Wu, Jian Zhao. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data openly available in a public repository. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://tor-wf-dl.distrinet-research.be/files (accessed on 31 October 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. C. Zhang, X. Luo, J. Liang, X. Liu, L. Zhu and S. Guo, “POTA: Privacy-preserving online multi-task assignment with path planning,” IEEE Trans. Mobile Comput., vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 5999–6011, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TMC.2023.3315324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. C. Hu, C. Zhang, D. Lei, T. Wu, X. Liu and L. Zhu, “Achieving privacy-preserving and verifiable support vector machine training in the cloud,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security, vol. 18, pp. 3476–4291, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TIFS.2023.3283104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. B. Gao, W. Liu, G. Liu, and F. Nie, “Resource knowledge-driven heterogeneous graph learning for website fingerprinting,” IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 968–981, 2024. doi: 10.1109/TCCN.2024.3350531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. X. Yuan, T. Li, L. Li, R. Li, Z. Wang and X. Luo, “HSWF: Enhancing website fingerprinting attacks on Tor to address real-world distribution mismatch,” Comput. Netw., vol. 241, no. 4, 2024, Art. no. 110217. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. M. Juarez, S. Afroz, G. Acar, C. Diaz, and R. Greenstadt, “A critical evaluation of website fingerprinting attacks,” in Proc. 2014 ACM SIGSAC Conf. Comput. Commun. Secur., Scottsdale, AZ, USA, Nov. 3–7, 2014, pp. 263–274. [Google Scholar]

6. Y. Wang, H. Xu, Z. Guo, Z. Qin, and K. Ren, “SNWF: Website fingerprinting attack by ensembling the snapshot of deep learning,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1214–1226, 2022. doi: 10.1109/TIFS.2022.3158086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. D. Herrmann, R. Wendolsky, and H. Federrath, “Website fingerprinting: Attacking popular privacy enhancing technologies with the multinomial naïve-bayes classifier,” in Proc. 2009 ACM Worksh. Cloud Comput. Secur., Chicago, IL, USA, Nov. 11–13, 2009, pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

8. A. Panchenko, L. Niessen, A. Zinnen, and T. Engel, “Website fingerprinting in onion routing based anonymization networks,” in Proc. 10th Annu. ACM Workshop Priv. Electron. Soc., Chicago, IL, USA, Oct. 17–21, 2011, pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

9. T. Wang, X. Cai, R. Nithyanand, R. Johnson, and I. Goldberg, “Effective attacks and provable defenses for website fingerprinting,” in Proc. 23rd USENIX Secur. Symp. (USENIX Secur. 14), San Diego, CA, USA, Aug. 20–22, 2014, pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

10. A. Panchenko et al., “Website fingerprinting at internet scale,” in Proc. Netw. Distrib. Syst. Secur. Symp. (NDSS), San Diego, CA, USA, Feb. 21–24, 2016. [Google Scholar]

11. P. Sirinam, M. Imani, M. Juarez, and M. Wright, “Deep fingerprinting: Undermining website fingerprinting defenses with deep learning,” in Proc. 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conf. Comput. Commun. Security (CCS), Toronto, ON, Canada, Oct. 15–19, 2018, pp. 1928–1943. [Google Scholar]

12. M. Juarez, M. Imani, M. Perry, C. Diaz, and M. Wright, “Toward an efficient website fingerprinting defense,” in Comput. Secur.–ESORICS 2016: 21st Eur. Symp. Res. Comput. Secur., Heraklion, Greece, Sep. 26–30, 2016, pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

13. T. Wang and I. Goldberg, “Walkie-Talkie: An efficient defense against passive website fingerprinting attacks,” in Proc. 26th USENIX Secur. Symp. (USENIX Secur. 17), Vancouver, BC, Canada, Aug. 16–18, 2017, pp. 1375–1390. [Google Scholar]

14. S. Bhat, D. Lu, A. Kwon, and S. Devadas, “Var-CNN: A data-efficient website fingerprinting attack based on deep learning,” 2018, arXiv:1802.10215. [Google Scholar]

15. P. Sirinam, N. Mathews, M. S. Rahman, and M. Wright, “Triplet fingerprinting: More practical and portable website fingerprinting with n-shot learning,” in Proc. 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conf. Comput. Commun. Security (CCS), London, UK, Nov. 11–15, 2019, pp. 1131–1148. [Google Scholar]

16. C. Wang, J. Dani, X. Li, X. Jia, and B. Wang, “Adaptive fingerprinting: Website fingerprinting over few encrypted traffic,” in Proc. 11th ACM Conf. Data Appl. Security Privacy (CODASPY), Dallas, TX, USA, Mar. 22–24, 2021, pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

17. Q. Yin et al., “Automated multi-tab website fingerprinting attack,” IEEE Trans. Depend. Secure Comput., vol. 18, no. 8, pp. 3656–3670, 2021. [Google Scholar]

18. Z. Luo, S. Xu, and X. Liu, “Scheme for identifying malware traffic with TLS data based on machine learning,” (in ChineseChin. J. Network Inf. Secur., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 77–83, 2020. [Google Scholar]

19. V. Rimmer, D. Preuveneers, M. Juarez, T. Van Goethem, and W. Joosen, “Automated website fingerprinting through deep learning,” 2017, arXiv:1708.06376. [Google Scholar]

20. T. Wang, “High precision open-world website fingerprinting,” in Proc. 2020 IEEE Symp. Secur. Priv.(SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, May 18–20, 2020, pp. 152–167. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools