Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LEGF-DST: LLMs-Enhanced Graph-Fusion Dual-Stream Transformer for Fine-Grained Chinese Malicious SMS Detection

1 School of Information and Cybersecurity, People’s Public Security University of China, Beijing, 100038, China

2 Cyber Investigation Technology Research and Development Center, The Third Research Institute of the Ministry of Public Security, Shanghai, 201204, China

3 Department of Cybersecurity Defense, Beijing Police College, Beijing, 102202, China

4 School of Computer Science, Henan Institute of Engineering, Zhengzhou, 451191, China

* Corresponding Author: Jingya Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 1901-1924. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.059018

Received 26 September 2024; Accepted 20 November 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

With the widespread use of SMS (Short Message Service), the proliferation of malicious SMS has emerged as a pressing societal issue. While deep learning-based text classifiers offer promise, they often exhibit suboptimal performance in fine-grained detection tasks, primarily due to imbalanced datasets and insufficient model representation capabilities. To address this challenge, this paper proposes an LLMs-enhanced graph fusion dual-stream Transformer model for fine-grained Chinese malicious SMS detection. During the data processing stage, Large Language Models (LLMs) are employed for data augmentation, mitigating dataset imbalance. In the data input stage, both word-level and character-level features are utilized as model inputs, enhancing the richness of features and preventing information loss. A dual-stream Transformer serves as the backbone network in the learning representation stage, complemented by a graph-based feature fusion mechanism. At the output stage, both supervised classification cross-entropy loss and supervised contrastive learning loss are used as multi-task optimization objectives, further enhancing the model’s feature representation. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms baselines on a publicly available Chinese malicious SMS dataset.Keywords

The proliferation of mobile communication technology has made life more convenient but has also led to a surge in the spread of malicious and harmful content via SMS. In recent years, the rapid development of machine learning, particularly deep learning technologies, has provided effective solutions for text classification tasks and technical support for building intelligent malicious SMS detection systems. However, existing methods face several limitations that hinder their effectiveness. Most methods are limited to binary classification, categorizing SMS as malicious or benign, and lack the capability for fine-grained analysis. Additionally, the small proportion of malicious SMS compared to benign ones limits the model’s ability to generalize to minority classes. Additionally, the representational capacities of existing models are often inadequate, generally failing to capture the intricate nuances and contextual subtleties of SMS, thereby limiting their efficacy in accurately detecting malicious messages.

To address the challenges in detecting malicious SMS in Chinese, we propose an advanced model: the LLMs-enhanced Graph-Fusion Dual-Stream Transformer (LEGF-DST). Fig. 1 outlines our approach to tackling current limitations in this field. The primary contributions of this paper are as follows:

Figure 1: The strategy of the LEGF-DST addressing limitations in malicious SMS detection methods

(1) Utilization of LLMs for Data Augmentation: To mitigate the challenges posed by imbalanced data distribution, we employ various commercial LLMs with billions of parameters for data augmentation. This approach helps alleviate data scarcity and class imbalance issues.

(2) Construction of Multi-view Input Features and Graph-based Feature Fusion: The proposed model processes SMS from both word-level and character-level perspectives, enriching feature representation and capturing different aspects of malicious content. These multi-view features are transformed into dynamic graph data, which are then integrated using a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to effectively fuse features from both perspectives.

(3) Mixed Supervision-based Multi-task Optimization Method: We employ a supervised cross-entropy classification loss and a supervised contrastive learning loss as optimization objectives, which facilitate the model’s comprehensive learning of data features to enhance generalization. Consequently, this model is well-suited for more fine-grained SMS analysis tasks.

Experiments on public malicious SMS datasets demonstrate that LEGF-DST achieves an accuracy of 97.79% in handling fine-grained Chinese malicious SMS with 15 categories, outperforming current mainstream machine learning and deep learning-based malicious SMS detection methods.

2.1 Malicious Content Detection

2.1.1 Machine Learning-Based Methods

Traditional malicious SMS detection primarily relied on rule-based methods using keywords and sender identifiers, which often lack accuracy and flexibility, and are challenging to maintain. To overcome these limitations, researchers have increasingly adopted machine learning (ML) techniques. Taufiq Nuruzzaman et al. [1] and Ho et al. [2] proposed ML models using Naive Bayes and graph-based K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), respectively, to detect SMS threats, showing their viability on mobile platforms. Nagwani et al. [3] combined clustering and classification to build a feature database, enhancing historical matching. Aragao’s Support Vector Machine (SVM)-based approach achieved high accuracy at 98%, outperforming Naive Bayes at 87% [4]. Abid et al. [5] used Random Forest with Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) and bag of words to handle imbalanced data, achieving superior accuracy among various models. Xia et al. [6] applied a Hidden Markov Model for multilingual spam detection, effectively mitigating challenges associated with low-frequency words.

Since SMS data characteristics significantly impact classifier accuracy, recent research emphasizes feature engineering. Kumar et al. [7] introduced an ensemble selection algorithm combining SVM and Random Forest, leveraging cross-validation to efficiently manage high-dimensional data. Ilhan Taskin et al. [8] applied Copula clustering for nonlinear feature selection, yielding better performance than linear methods. Mamdouh Farghaly et al.’s method [9] reduced redundant features using frequency and correlation analysis, achieving 95.155% accuracy with minimal feature retention. Juneja et al. [10] presented a two-stage fuzzy model to refine feature selection, ultimately boosting classifier accuracy through targeted filtering and fuzzy logic-based evaluation.

While statistical machine learning methods show promise in detecting malicious SMS, their limitations are notable. Constraints in semantic understanding hinder these models from capturing complex text patterns, reducing their effectiveness in identifying novel malicious content. Additionally, as the volume of data increases, model performance plateaus, limiting the benefits of additional data and leading to diminishing returns on resource investment. These limitations restrict the scalability and adaptability of statistical machine learning in the dynamic field of malicious message detection.

2.1.2 Deep Learning-Based Methods

Deep learning has outperformed traditional machine learning in handling unstructured data, leading to advances in malicious SMS detection. Abayomi-Alli et al. [11] introduced a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) model that surpassed traditional classifiers on UCI_SMS and ExAIS_SMS datasets, benefiting further from regular expression optimizations. Roy et al. [12] found that the Text Convolutional Neural Network (TextCNN) outperformed BiLSTM on imbalanced data, while Xia et al. [13] incorporated category learning attention into a Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) model, achieving 99.46% accuracy by focusing on densely distributed words in short texts. Yao et al. [14] combined BiGRU and TextCNN with a text-speech embedding to address homophones in spam.

Pre-trained models [15–18] have further enhanced SMS detection by fine-tuning general language features for domain-specific tasks, enabling dynamic embeddings that better address polysemy. Liu et al. [19] demonstrated that Transformer models outperformed BiLSTM on varied datasets. Ghourabi et al. [20] used GPT-3 embeddings with ensemble learning, merging deep and statistical learning methods. Zhang et al. [21] and Gao et al. [22] used BERT and graph neural networks to enhance feature extraction, achieving strong performance in Chinese SMS detection. To overcome static keyword limitations, Oswald et al. [23] developed an intent-based filter that combines 13 predefined intent labels with BERT embeddings, delivering robust performance.

While deep learning methods have improved high-level semantic extraction, notable limitations remain. Current research primarily focuses on network structure optimization within end-to-end frameworks, often overlooking the importance of data and feature diversity, which constrains model generalization in complex or emerging malicious SMS scenarios. Additionally, refining training objectives is necessary to further enhance detection accuracy and robustness.

LLMs, exemplified by ChatGPT [24], have demonstrated remarkable performance across various Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks. Currently, LLMs exhibit significant potential across diverse fields. In the legal domain, ChatLaw [25], a multi-agent system based on LLMs, has shown robust capabilities in providing legal consultations. In finance, BloombergGPT [26], trained on extensive financial data, has achieved high performance on various financial tasks. In the medical domain, models such as BioMedGPT [27] and Huatuo [28] support analysis and research efforts. Additionally, LLMs have proven reliable and useful in fields like psychology [29] and human-computer interaction [30,31].

Beyond addressing specific tasks, LLMs have demonstrated effectiveness in data generation. Sahu et al. [32] evaluated GPT-3 for intent classification in data augmentation, showing that GPT-3-generated data significantly boosts downstream classifier performance, particularly in low-data scenarios. However, the lack of human alignment in GPT-3 presents challenges in enhancing data diversity through prompt engineering, sometimes resulting in lower-quality outputs. Ye et al. [33] proposed the LLM-DA model with 14 rewriting strategies that effectively bolstered Named Entity Recognition performance in resource-limited contexts, highlighting the value of multi-strategy prompting for high-quality data synthesis with LLMs. Similarly, Wu et al. [34] introduced CALLM, capable of generating medical datasets by simulating roles like patients or doctors, thus advancing low- and zero-shot tasks. Lai et al. [35] developed RumorLLM for rumor detection, transforming existing rumors into new variations while preserving style and semantic consistency, achieving data augmentation. However, these studies predominantly concentrate on data processing for English NLP tasks, leaving the enhancement effects of LLMs on Chinese-language tasks largely unverified.

2.3 Graph Techniques in NLP Tasks

Text classification is one of the core challenges in NLP. While many NLP models utilize sequential deep learning techniques, graph-based models can directly handle complex structured text data and leverage global information. The TextGCN [36] model represents text data as a graph structure, where nodes correspond to words and documents, and edges are constructed based on word co-occurrence information and TF-IDF weights. TG-Transformer [37] introduces heterogeneity into this graph structure, assigning different weights to document nodes and word nodes. To manage large-scale corpora, the model employs the PageRank algorithm for subgraph sampling.

To harness the knowledge within pre-trained models, BertGCN [38] initializes document nodes using the Classification Token ([CLS]) from BERT, while assigning zero values to the inputs of word nodes, enhancing TextGCN’s representational capacity. It also combines TextGCN and BERT outputs via interpolation for joint training. To further enhance multi-view information extraction, TensorGCN [39] constructs three independent graphs: a semantic-based, a syntax-based, and a sequence-based, and then integrates them into a tensor, where word-document edges across all graphs share the same TF-IDF values.

While these approaches provide valuable insights into the application of graph techniques within NLP, the majority are deductive models with constrained generalization capabilities. Additionally, the process of transforming text into a graph structure often relies on statistical information such as word frequency. A key challenge in this field remains constructing graph structures that incorporate advanced semantic features.

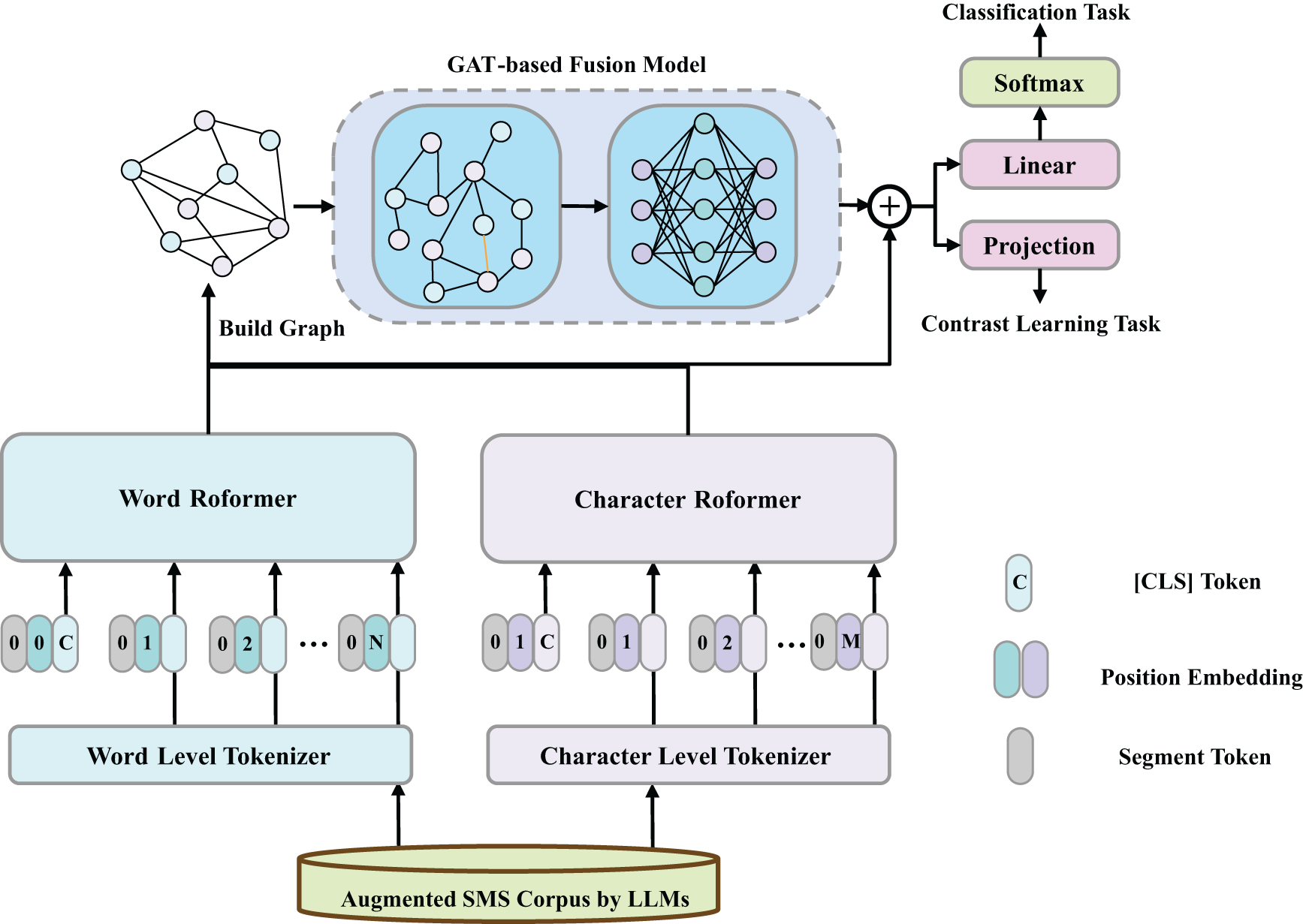

To develop a more accurate detection system for Chinese malicious SMS, this paper proposes a model that integrates LLMs enhancement and multi-view multi-task optimization based on a Chinese pre-trained model. The overall framework structure of the model is illustrated in Fig. 2, and it primarily includes LLMs-based data augmentation, dual-view input, a pre-trained backbone network with graph-based feature fusion, and a multi-task optimization output.

Figure 2: The overall structure of the LEGF-DST model

Specifically, during the data processing stage, LLMs with billions of parameters are used for semantic-level data augmentation. In the input module, both word-level and character-level features of SMS are used as model inputs. In the feature analysis stage, a dual-tower Transformer backbone facilitates robust feature extraction and interaction, while a GAT fuses multi-view features.

In the output stage, both supervised classification cross-entropy loss and supervised category contrastive learning loss are used as optimization objectives. This helps the model further learn intrinsic association features within the text, ultimately achieving effective analysis and detection of malicious SMS.

3.2 LLMs-Based Data Augmentation

LLMs are trained on massive datasets and aligned with human preferences, enabling them to possess extensive world knowledge. Specifically, the training of LLMs involves three main steps:

(1) Unsupervised Pre-training: During the pre-training phase, the model learns rich semantic and syntactic knowledge from large-scale data without relying on manually labeled data. Instead, the model adopts Next Token Prediction (NTP) as its training objective, as shown in Eq. (1). In this equation,

(2) Supervised Fine-tuning: The supervised fine-tuning process leverages high-quality, manually annotated instruction-response datasets to train the model. This approach enhances the model’s ability to understand human instructions and activate stored knowledge, aligning outputs more closely with human needs.

(3) Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) [40]: In this phase, a reward model is introduced to assess the quality of the model’s outputs, enabling performance optimization through interactions with human feedback. This further enhances the accuracy and fluency of the model’s outputs. Typically, the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm is used for the specific training in RLHF. The optimization objective is detailed in Eq. (2), where

LLMs have been proven to possess human-level capabilities in text annotation tasks and can be used for various natural language generation tasks, such as text summarization and question answering. This implies that LLMs can be used for semantic-level data augmentation rather than traditional token-level methods [41].

To efficiently leverage LLMs for high-quality data augmentation while mitigating the risk of overfitting, we have designed a flexible prompt engineering framework aimed at enhancing the diversity of generated data. The detailed workflow is illustrated in Fig. 3. Initially, a persona library was introduced to enhance LLMs with diverse character identities. These personas encompass roles simulating potential adversaries (e.g., social engineering hackers, advertisers, scammers, and phishing attackers) as well as neutral roles (e.g., editors and writers), enabling the generation of data in varied rephrasing styles.

Figure 3: Prompt generation strategy in LEGF-DST for sample augmentation

Next, we constructed a task description library encompassing a range of directives, such as rewriting, expansion, and summarization. By using a variety of prompt templates, we enable flexible prompt generation through random combinations of personas and task descriptions.

For model selection, we employed three representative Chinese LLMs: ChatGLM [42], MiniMax, and Baichuan [43], to enhance the quality of generated samples. Additionally, by adjusting hyperparameters such as the temperature coefficient and Top-K, we further minimized data redundancy in the outputs, ensuring both diversity and novelty in the generated content.

We also accounted for the proportion of original samples during the generation process, producing additional samples for underrepresented categories to ensure a more balanced training dataset. Finally, a comparison of data distribution before and after LLMs enhancement is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: After using LLMs for data augmentation, the distribution of the training set becomes more balanced. Left: original training set. Right: training set augmented with LLMs

3.3 Dual-Stream Transformer with Mutil-View Features

In the multi-view feature input phase, we introduce both word-level and character-level features to enhance the model’s representation capability while minimizing information loss.

For word-level feature extraction, we utilize a word-level tokenizer to process SMS text, mapping each word to its corresponding token. This method captures the overall semantic information of words, particularly preserving the inherent semantic structure and expression of longer words or fixed phrases. For instance, certain compound words or phrases may convey critical category information in SMS classification tasks.

To further capture fine-grained semantic information within SMS text, we process the text at the character level, treating each character as an independent token. Character-level processing enables the model to capture subtle relationships and semantic nuances between characters, especially in languages like Chinese, where individual characters and their order of combination can convey different meanings. For example, malicious SMS may obscure their true intent through subtle character modifications, and character-level processing can effectively detect such changes, ensuring the fidelity of textual information.

Additionally, to improve the model’s ability to recognize specific types of SMS, we expanded the vocabulary of the Transformer. Specifically, we added high-frequency words unique to different SMS categories by statistically analyzing the distinctive high-frequency terms in the training data.

We conducted a systematic investigation of the current mainstream Chinese pre-trained Transformer models, with a particular focus on their tokenization methods and vocabulary size (as detailed in Table 1).

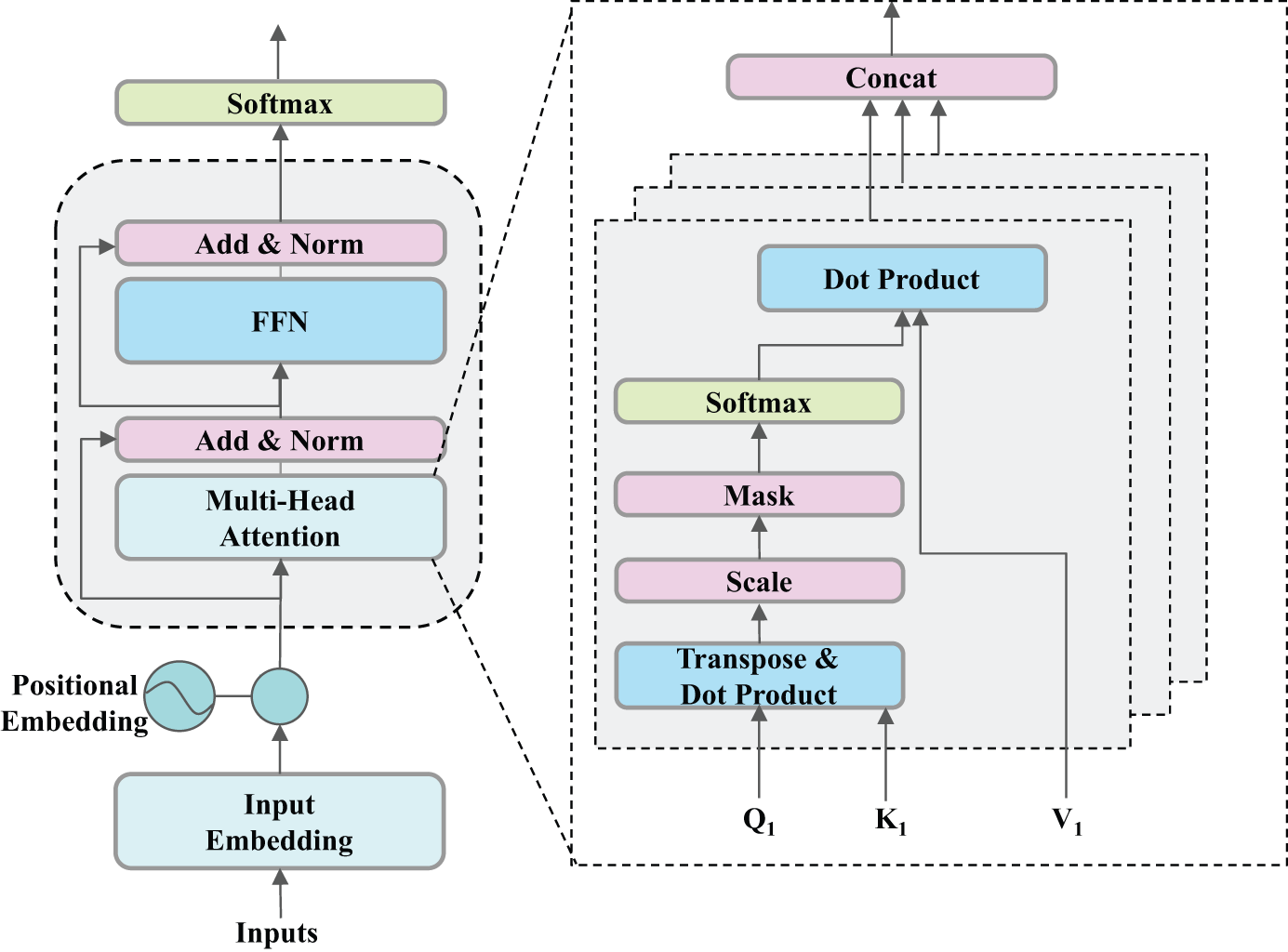

To effectively extract word-level features, we selected Word-Roformer [44] as a component of the backbone network. To maintain structural symmetry and optimize computational efficiency, Char-Roformer was employed for character-level feature analysis. Compared to other models, Char-Roformer enhances operational speed without compromising model performance by removing bias terms and normalization operations. RoFormer is a variant based on the Transformer [45] architecture, with the core module being the Transformer Encoder, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The Transformer encoder block

RoFormer utilizes Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE) during the input processing stage, injecting positional information into the input tokens to preserve sequential relationships when the model processes the sequence. The process is outlined in Eq. (3), where

During feature processing, RoFormer alternates between Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) and Feed-Forward Networks (FFN) to extract deep-level features, as described in Eqs. (4) and (5), where Q, K, and V represent the query, key, and value vectors, respectively, and

3.4 Graph-Based Feature Fusion

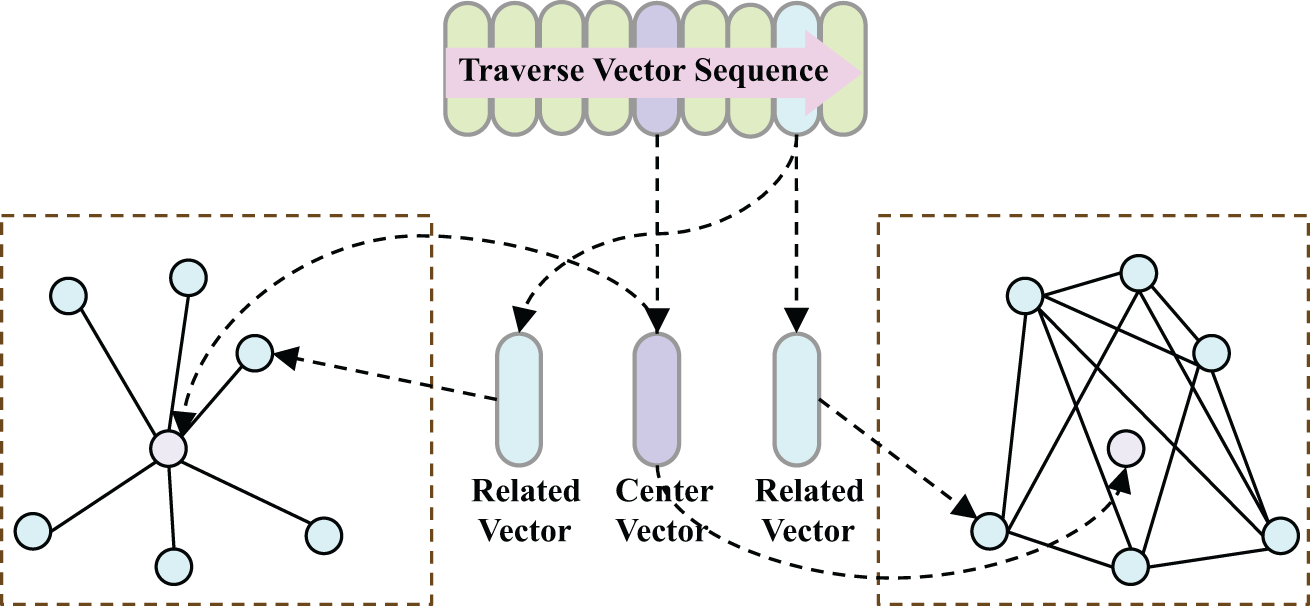

To more effectively fuse dual-view features, we propose a feature fusion method based on graph processing. Since the output vector sequence of the dual-stream Transformer model cannot be directly processed by a GAT [46], it is necessary to transform the vector sequence into a graph structure. The current mainstream approach is to construct a KNN graph. However, this method has some limitations.

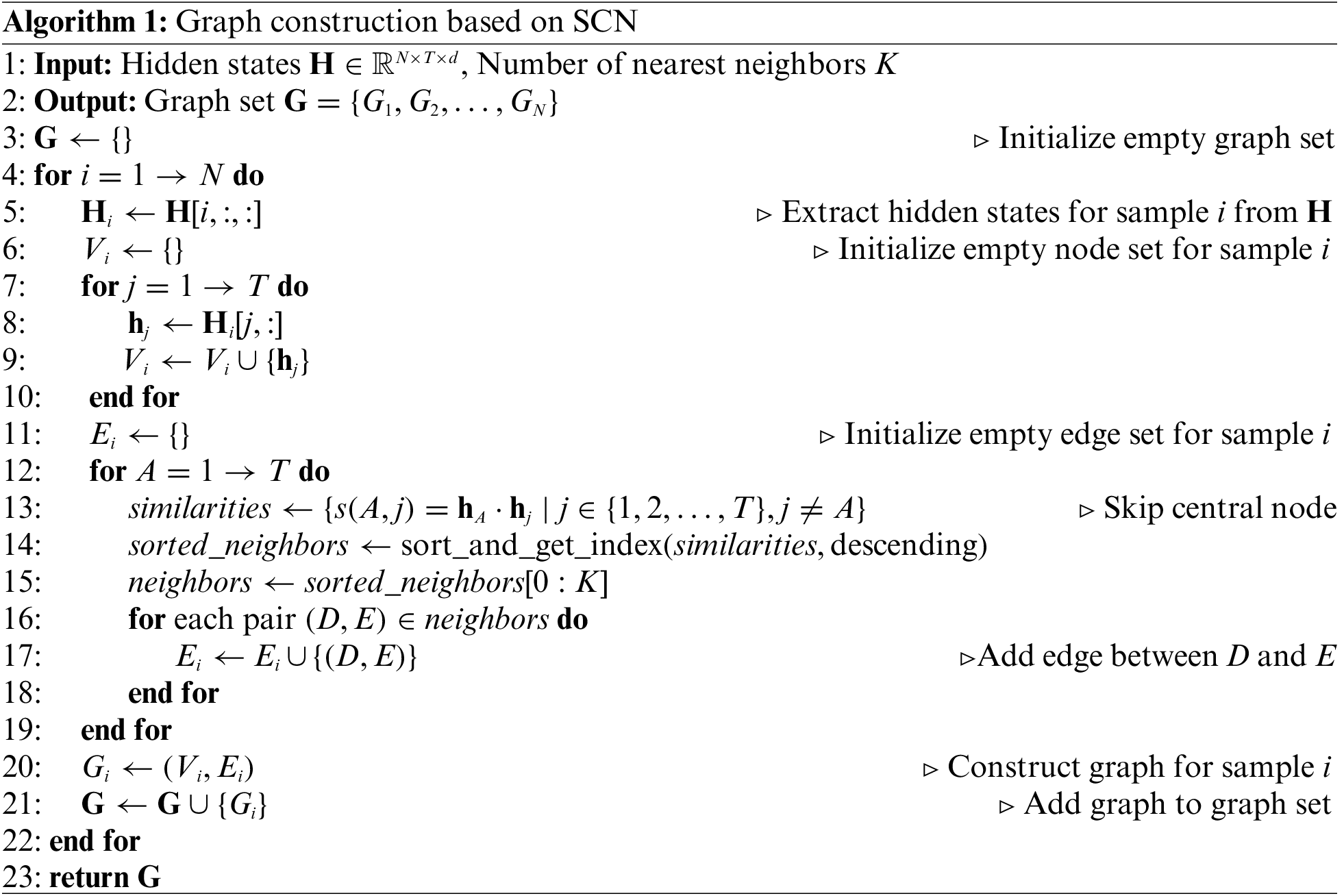

Firstly, the connections between the central node and its neighbors are typically determined solely by similarity metrics, which provide limited information and restrict the expressive capacity of the generated graph structure. Secondly, this approach often causes the central node to dominate the feature fusion process, thereby weakening the contribution of other nodes and resulting in an imbalanced flow of information. To overcome these challenges, we propose a Skip Central Node (SCN) method, as detailed in Algorithm 1.

The core concept of SCN is as follows: first, retrieve the most relevant neighbor vectors based on the central node; then, during graph construction, exclude the central node and only establish edges between these related neighboring nodes. Compared to the traditional star-shaped graph structure (as shown in Fig. 6), this method effectively reduces the direct influence of the central node on the graph structure, transforming the central node into a bridge for relational retrieval, indirectly connecting potentially related neighboring nodes. This strategy not only reduces the interference of redundant features but also enhances the diversity of the graph structure, thereby facilitating better aggregation of deep semantic information.

Figure 6: Comparison of two methods for converting word vector sequences into graphs. Left: KNN-based graph construction. Right: SCN-based graph construction

The SCN method aims to enhance feature fusion by refining the traditional KNN graph construction process. Understanding computational complexity is crucial for assessing the scalability and efficiency of the proposed approach, particularly when handling large datasets or long input sequences. The time complexity of SCN primarily stems from the following steps:

(1) Sample Iteration (Outer Loop): For a batch of samples of size N, the loop executes N times.

(2) Node Set Construction: For each sample, the time complexity to build the node set is

(3) Edge Set Construction: First, for each node A, similarity with the remaining

Consequently, the time complexity of SCN for processing a single sample is

After constructing the SCN graph, the GAT is employed to process the graph structure. In GAT, the feature representation of each node is determined not only by its own attributes but also by the features of its neighboring nodes and the attention weights assigned to these connections. The self-attention mechanism assigns different attention coefficients to the neighboring nodes, highlighting the contributions of important nodes while diminishing the impact of less significant ones. This enables the network to extract more useful information from complex structures, as illustrated in Eqs. (6) and (7). Consequently, after processing by GAT, each node’s features are thoroughly fused and optimized, allowing the model to capture multi-scale contextual information.

Upon completing the GAT processing of the graph structure, we perform global pooling on the generated node features to aggregate the local node information. Additionally, to further enhance the expressive power of the global features, we concatenate the [CLS] vectors generated from the two branches of the dual-stream Transformer with the globally pooled graph node features. This results in a comprehensive sentence representation vector that integrates both local semantic relationships between words in the sentence and global semantic features, thereby offering higher semantic completeness and expressive capability.

To further enhance the model’s representation capability and classification performance, we introduce two optimization objectives to guide the training process:

(1) Categorical Cross-Entropy Loss: Categorical cross-entropy loss is a widely adopted objective function in supervised classification tasks. It measures the divergence between the model’s predicted probability distribution and the ground truth label distribution, directly guiding classification performance. The model’s output represents a probability distribution across classes, and this loss minimizes the negative log-likelihood of the true labels, thereby encouraging the model to maximize the probability assigned to the correct class. This is formally defined in Eq. (8), where

(2) Supervised Contrastive Loss [47]: This loss function enhances the model’s ability to cluster same-class samples and separate different-class samples by bringing feature vectors of the same class closer together and pushing those of different classes further apart. The process is illustrated in Eq. (9), where

The ultimate optimization objective is a weighted average of the two loss functions, as shown in Eq. (10). By combining the categorical cross-entropy loss with the supervised contrastive loss, the model is not only able to directly optimize classification performance but also to enhance inter-class differences and intra-class consistency within the feature space. This dual optimization strategy helps the model better capture the complex features, thereby enhancing its performance in fine-grained analysis tasks.

4.1 Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of the LEGF-DST model in the malicious SMS detection task, we conducted experiments based on the publicly available fine-grained dataset FBS_SMS_Dataset [48], which contains 14 malicious categories, including gambling promotions, fake bank frauds, retail advertisements, and more. Additionally, we added normal SMS samples to the dataset to simulate real-world scenarios where regular and malicious SMS coexist. In the experiments, the training set, augmented training set (used by LEGF-DST), validation set, and test set contained 8000, 27,900, 2000, and 7500 samples, respectively.

The hardware configuration and software environment of the server used in the experiment are shown in Table 2. During the training process, the AdamW optimizer was used, with the batch size and learning rate set to 256 and 5e-5, respectively. In the LEGF-DST model, the K is set to 2 when constructing the SCN graph.

The evaluation of model detection performance in this study is conducted using four key metrics: accuracy, weight-precision, weight-recall, and weight-F1 Score, as defined in Eqs. (11)–(13). TP and TN represent the numbers of true positives and true negatives, while FP and FN represent false positives and false negatives.

In the experiments, we selected methods from both statistical machine learning and deep neural networks as baselines. On one hand, we used Naive Bayes (NB), Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), SVM, KNN, and CatBoost [49] based on TF-IDF features as comparison models. On the other hand, we selected TextCNN [50], DPCNN [51], BiLSTM, and BiGRU [52] for comparison. Additionally, we included various pre-trained models as baselines, including ALBERT [15], TinyBERT [18], RoBERTa [16], ERNIE [17], Char-Roformer, Word-Roformer, and GF-DST (LEGF-DST without LLMs-based enhancement) model. We evaluated the performance of the model by conducting experiments on both a binary classification task for malicious SMS detection and a fine-grained multi-class classification task. The experimental results are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

An analysis of the experimental results indicates that, in the binary classification task, the performance differences among various models are negligible, with all deep learning-based approaches achieving near-perfect accuracy, close to 100%.

However, in the fine-grained classification task, model performance exhibited considerable variation. Overall, deep learning methods outperform traditional statistical machine learning methods overall, exhibiting stronger representational capabilities and higher classification accuracy. Among the statistical machine learning models, SVM and Random Forest performed relatively well, but they still fell short of deep learning models. This indicates that deep neural networks are more effective at handling complex textual features.

Further analysis of the experimental results indicates that pre-trained language models significantly outperform deep learning models trained from scratch in classification tasks. Models such as RoBERTa, Char-RoFormer, and Word-RoFormer all achieved accuracy rates exceeding 96%, demonstrating that the prior knowledge learned from large-scale corpora in pre-trained models can effectively enhance the performance of malicious SMS classification.

The LEGF-DST model proposed in this paper demonstrated superior performance compared to all baseline models, achieving an accuracy of 97.79% and delivering optimal results across all evaluated metrics. This indicates that the data generated by LLMs can significantly improve the robustness and generalization ability of classification models, leading to excellent performance in malicious SMS detection tasks. In comparison, despite not incorporating LLMs-based augmentation, GF-DST achieved an impressive accuracy of 97.29%, underscoring the advantages of our model design in representing malicious SMS features.

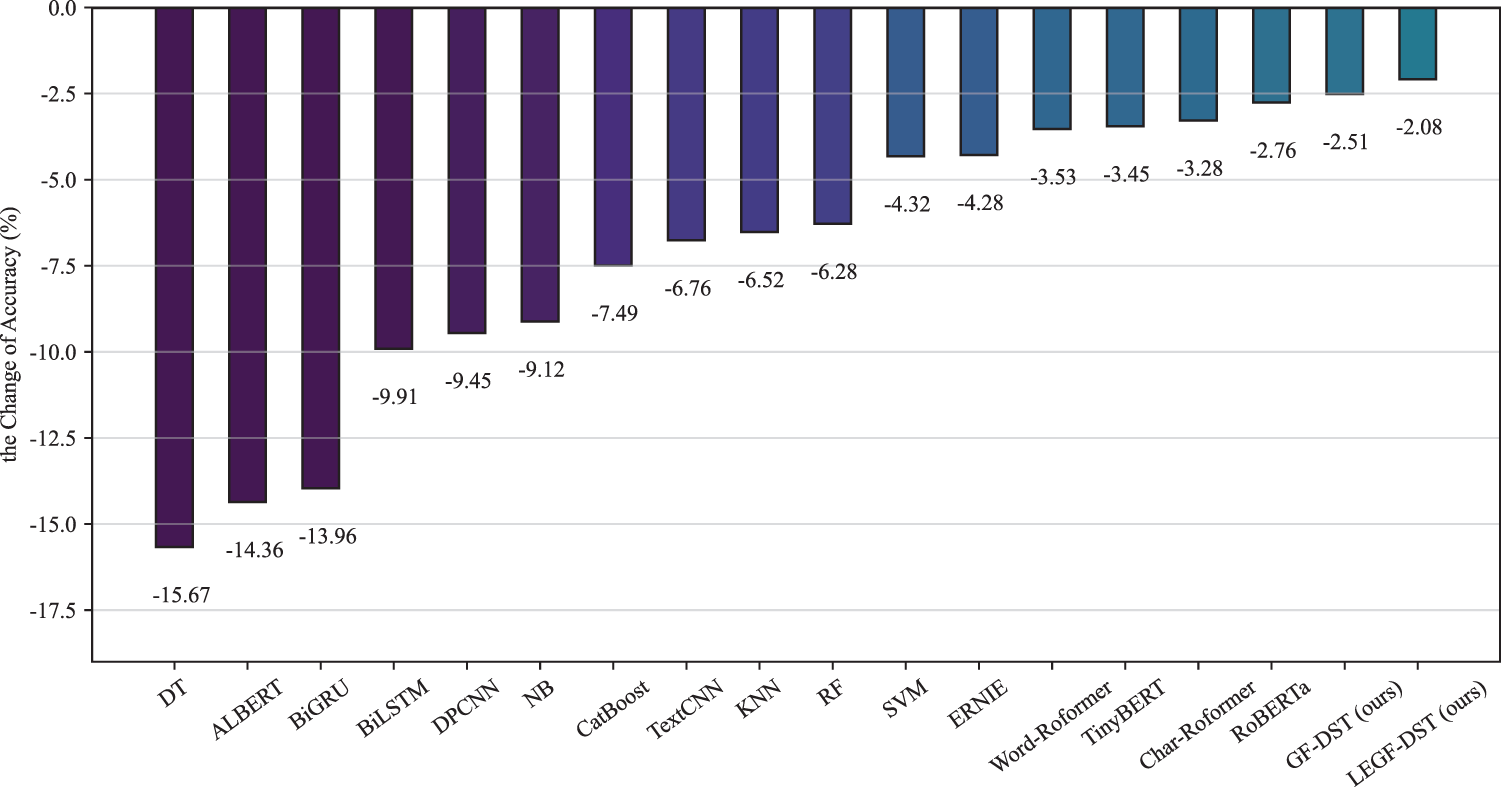

We conducted a comprehensive visual analysis of the accuracy degradation observed as models transitioned from binary classification tasks to multi-class classification tasks, as shown in Fig. 7. Most models exhibited a pronounced decline in accuracy, indicating certain limitations in their ability to capture fine-grained deep features. In contrast, the LEGF-DST model exhibited only a 2.08% decrease in accuracy, demonstrating its strong capability in feature representation.

Figure 7: Accuracy decline observed as models transitioned from the binary classification task to the multi-class classification task

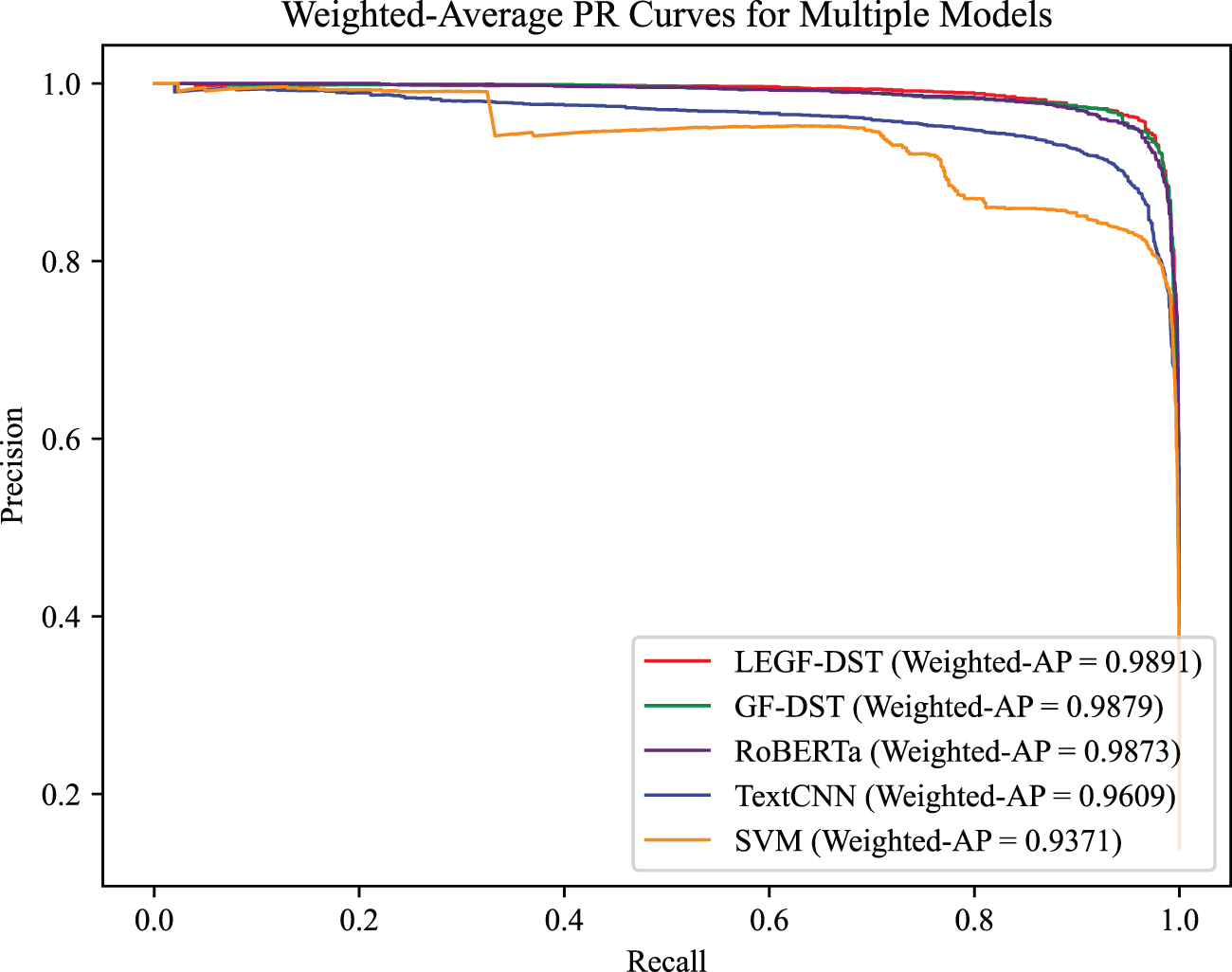

To analyze the classification reliability, we selected LEGF-DST and RoBERTa (the closest performance counterpart to our method), TextCNN, and SVM as representatives of deep learning and machine learning models. We visualized their PR curves on both datasets, as shown in Fig. 8. It can be seen that LEGF-DST has a superior Weighted Average Precision (Weighted-AP). This demonstrates that the proposed method exhibits superior robustness in SMS classification tasks and is better suited for handling complex data in real-world scenarios.

Figure 8: Comparing the PR curves of different models, LEGF-DST has the optimal Weighted-AP

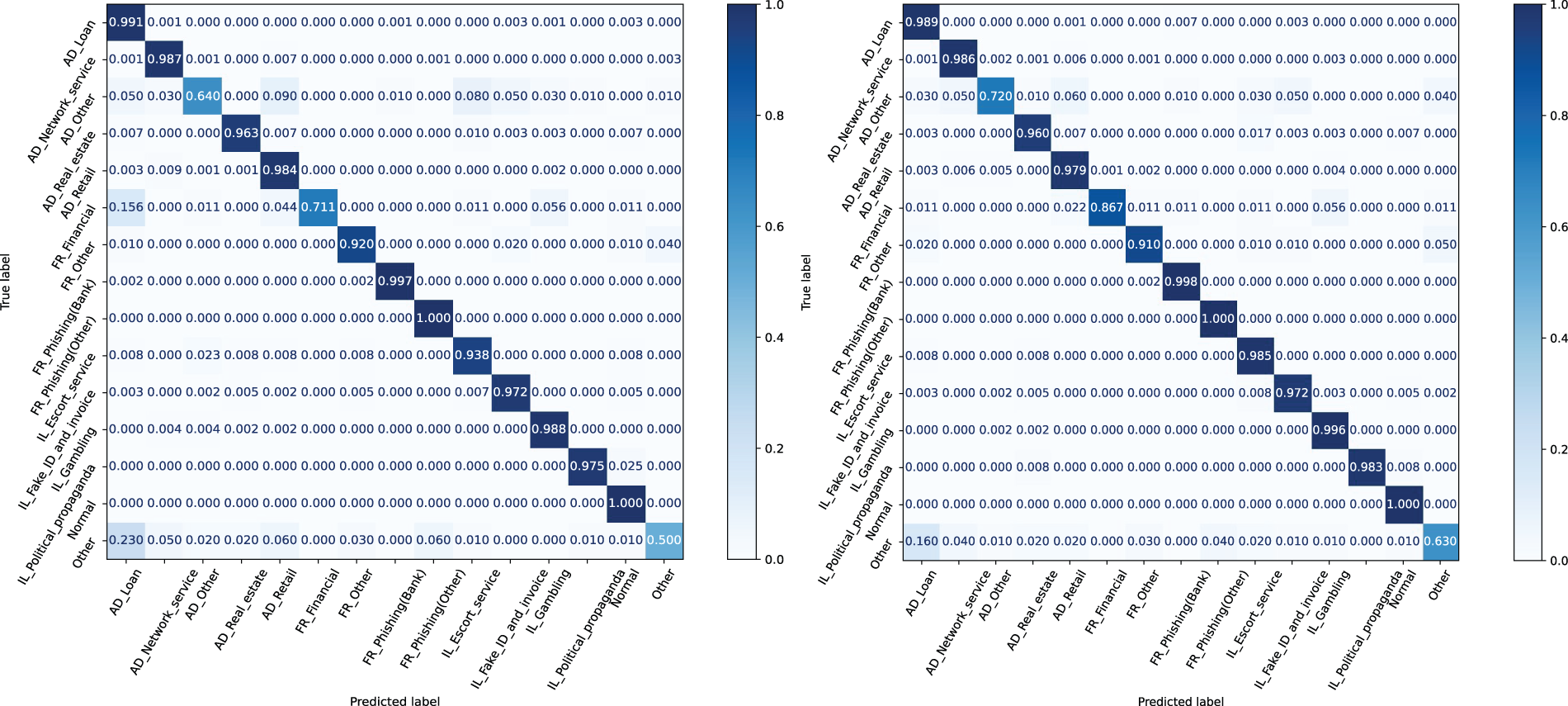

We also plotted the confusion matrices of the LEGF-DST model before and after augmentation, as shown in Fig. 9. It can be seen that the augmented LEGF-DST shows a significant improvement in recognition accuracy for the weaker categories AD_Other, FR_Financial, and Other.

Figure 9: After introducing LLMs-based augmentation, LEGF-DST can better recognize samples from several categories that were difficult to identify before augmentation. Left: GF-DST. Right: LEGF-DST

To conduct a more detailed analysis of the robustness of our models, we manually examined samples predicted by the LEGF-DST and RoBERTa, as illustrated in Table 5. On one hand, RoBERTa struggled with samples containing adversarial noise, such as traditional Chinese or visually similar characters. This limitation likely stems from the model’s reliance on single-perspective features, which results in insufficient redundancy and compensatory capacity when encountering specific types of noise interference. Consequently, RoBERTa is particularly sensitive to minor character-level variations and is prone to misclassification. Furthermore, samples containing deceptive terms such as  (legitimate) or

(legitimate) or  (reasonable) are often misclassified by RoBERTa as benign, underscoring the advantage of the dual-perspective feature analysis employed by the LEGF-DST. By integrating character-level and word-level features, LEGF-DST effectively captures subtle semantic distinctions. Specifically, character-level features are adept at identifying fine-grained variations, while word-level features enhance the understanding of broader semantic context. This synergy enables the LEGF-DST model to exhibit heightened robustness in identifying samples with deceptive terminology. Furthermore, RoBERTa exhibits limited accuracy in identifying high-risk samples, such as cult propaganda, due to limited domain-specific pre-training and insufficient labeled data for fine-tuning. In contrast, LEGF-DST, enhanced by LLMs, addresses this issue more effectively, demonstrating an improved capacity to identify such challenging samples. For ethical reasons, malicious content associated with cult propaganda is not displayed in this paper.

(reasonable) are often misclassified by RoBERTa as benign, underscoring the advantage of the dual-perspective feature analysis employed by the LEGF-DST. By integrating character-level and word-level features, LEGF-DST effectively captures subtle semantic distinctions. Specifically, character-level features are adept at identifying fine-grained variations, while word-level features enhance the understanding of broader semantic context. This synergy enables the LEGF-DST model to exhibit heightened robustness in identifying samples with deceptive terminology. Furthermore, RoBERTa exhibits limited accuracy in identifying high-risk samples, such as cult propaganda, due to limited domain-specific pre-training and insufficient labeled data for fine-tuning. In contrast, LEGF-DST, enhanced by LLMs, addresses this issue more effectively, demonstrating an improved capacity to identify such challenging samples. For ethical reasons, malicious content associated with cult propaganda is not displayed in this paper.

Additionally, we compared the LEGF-DST model with current mainstream methods for Chinese malicious SMS detection, and the results are presented in Table 6. It can be observed that the LEGF-DST model demonstrates distinct advantages in both coarse-grained detection and fine-grained analysis.

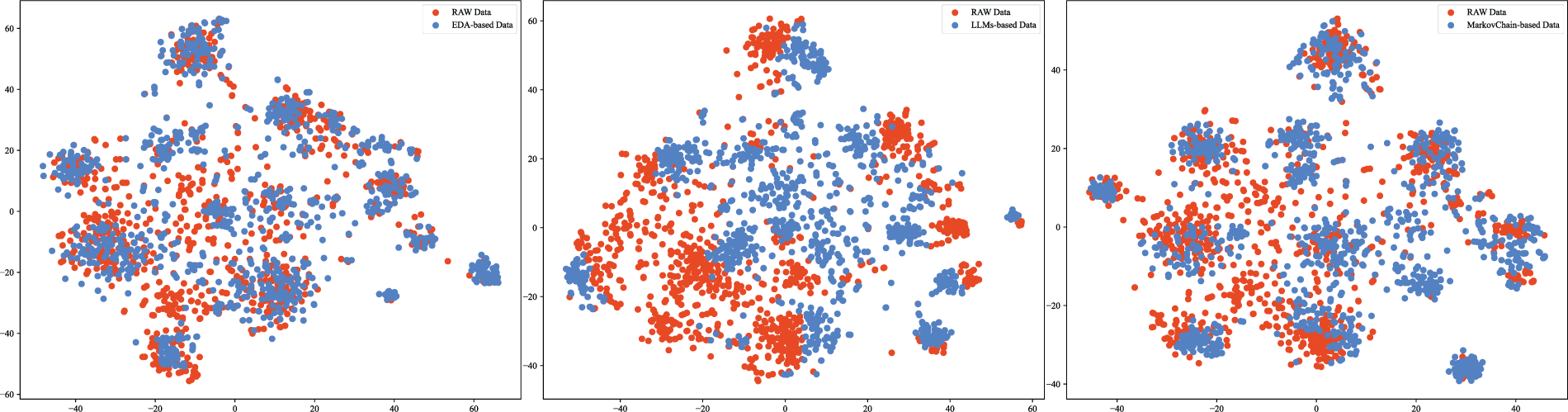

4.3 Analysis of Enhancing Data Validity

We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy of LLM-augmented data for this task, focusing on its diversity and validity. To facilitate a meaningful comparison, we sampled and visualized a subset of the data generated by different methods. Specifically, we compared the distribution of LLM-augmented data with that produced by two established techniques: Easy Data Augmentation (EDA) [41] and a Markov Chain-based method [53], as shown in Fig. 10. Data from EDA and the Markov Chain-based method exhibits overlaps with the original data, indicating limited capacity to introduce new features. This redundancy may not only restrict the model’s generalization ability but also increase the risk of overfitting. In contrast, LLMs-generated data shows a distinctly different distribution while preserving original semantics. This variation suggests that LLMs can create text with greater semantic and structural diversity without altering the SMS category. Such diversified training data enables the model to better capture complex features of malicious SMS, enhancing generalization and reducing overfitting. Consequently, LLMs-augmented data introduces novel feature patterns during training, significantly boosting classification performance.

Figure 10: Visualization of the distribution comparison of three data augmentation methods based on t-SNE. Left: EDA-based method. Center: LLMs-based method. Right: Markov Chain-based method

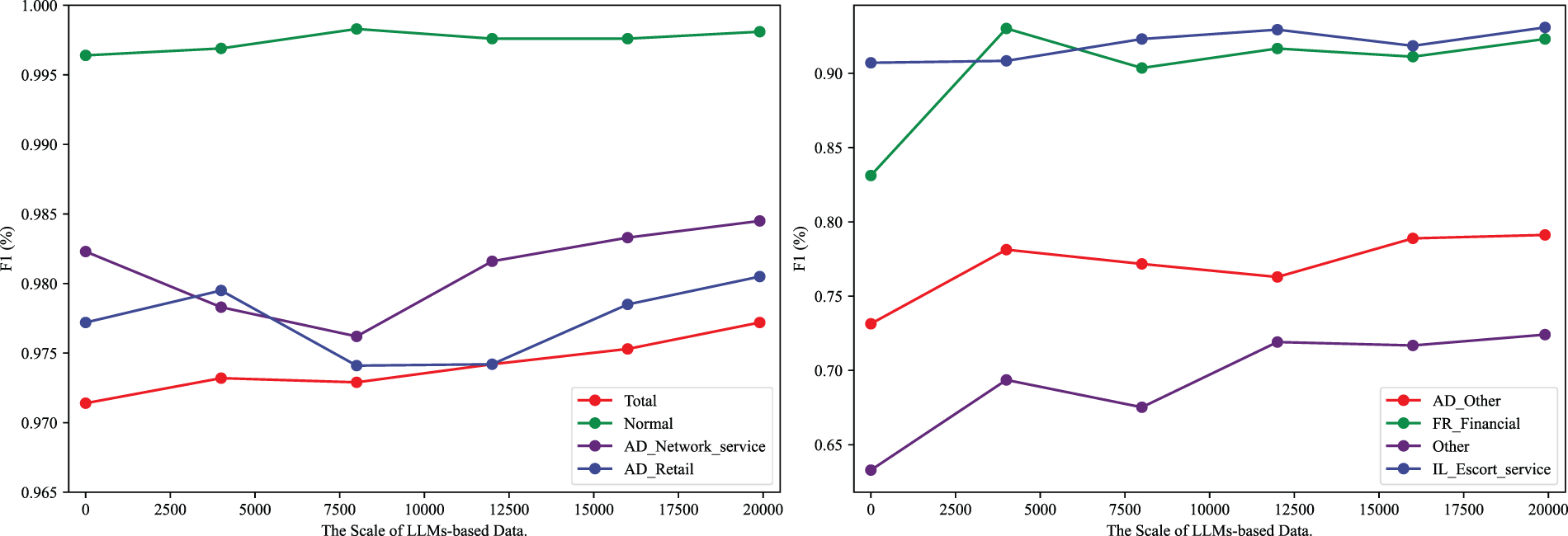

Additionally, we conducted a detailed investigation into the effect of the scale of data generated by LLMs on model performance. Our analysis specifically focused on the model’s overall performance, as well as its performance across high-frequency and low-frequency classes. The results are shown in Fig. 11. Overall, as the amount of generated data increases, the classification model’s performance consistently improves, and this improvement is observed in both high-frequency and low-frequency categories. This finding suggests that LLMs-generated data not only effectively augments the size of the training set but also enhances semantic diversity, reducing data redundancy and minimizing information repetition. Consequently, these factors collectively contribute to the model’s improved performance.

Figure 11: The impact of synthetic data scale on model performance. Left: overall performance and performance on high-frequency classes. Right: performance on low-frequency classes

To validate the contribution of each component within the LEGF-DST model, we conducted ablation experiments. Using the complete LEGF-DST model as the baseline, we attempted to remove different components to observe their impact on detection performance. The specific configurations tested include:

(1) LEGF-DST w EDA: Substituting LLMs-based data augmentation with an EDA method.

(2) LEGF-DST w OS: Substituting LLMs-based data augmentation with an oversampling method.

(3) LEGF-DST w MC: Substituting LLMs-based data augmentation with a Markov Chain-based method.

(4) LEGF-DST w/o character-level features: Substituting the Char-Word multi-view backbone network with a dual-stream Word-Roformer model.

(5) LEGF-DST w/o word-level features: Substituting the Char-Word multi-view backbone network with a dual-stream Char-Roformer model.

(6) LEGF-DST w/o SC loss: Removing the contrastive learning optimization objective.

(7) LEGF-DST w concat fusion: Substituting GAT-based feature fusion with an additive method.

(8) LEGF-DST w add fusion: Substituting GAT-based feature fusion with a concatenation method.

(9) LEGF-DST w attention fusion: Substituting GAT-based feature fusion with an attention-based method.

(10) LEGF-DST w KNN graph: Substituting SCN-based graph with a KNN-based graph.

The experimental results, presented in Table 7, demonstrate that each component contributes positively to the performance of the LEGF-DST. Models trained with LLMs-generated data perform better than traditional methods, such as EDA or oversampling. Simultaneously using character-level and word-level features helps the model extract high-level features of malicious SMS, thereby improving detection performance.

Additionally, the value of K plays a critical role in determining the time complexity of the LEGF-DST. To evaluate whether increasing K improves model performance, we analyzed the variation in Laplacian spectral entropy of the SCN graph for different K values relative to K = 2, as shown in Fig. 12. The results indicate that as K increases, the growth in Laplacian spectral entropy across input texts of varying lengths remains under 10%. This finding suggests that a smaller K value is sufficient to construct graph structures rich in information while significantly reducing computational costs.

Figure 12: Effect of K on the Laplacian spectral entropy of the SCN graph

Despite the LEGF-DST model’s notable performance improvements in fine-grained malicious SMS detection tasks, it is subject to the following limitations:

(1) Constraints on Time Complexity: The LEGF-DST employs a dual-tower structure as its backbone and integrates graph-based feature fusion during feature extraction, significantly increasing overall computational costs. Consequently, the model may struggle to efficiently process large-scale data in resource-limited environments, making it more applicable to scenarios where high detection accuracy is prioritized.

(2) Ethical Risks of LLMs-generated Data: Our research indicates that synthetic data generated by LLMs can effectively balance data distribution and enhance model detection performance. However, malicious actors could exploit LLMs to generate vast quantities of highly deceptive and harmful content at minimal cost. Such misuse has the potential to exacerbate the spread of malicious content, amplifying cybersecurity risks and raising profound ethical challenges.

(3) Limitations in Language Applicability: This study is validated on a Chinese dataset, leveraging the robust support for both word-level and character-level pre-trained models in this language. In contrast, processing other languages like English relies mainly on tokenization methods such as Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) and WordPiece, with limited support for character-level models. This disparity may limit the LEGF-DST model’s access to prior knowledge in non-Chinese languages, potentially impacting its performance.

To address the challenges in fine-grained Chinese malicious SMS detection tasks, this paper proposes an efficient LLMs-enhanced graph fusion dual-stream Transformer model, LEGF-DST. In the input section, word-level and character-level features are used as dual-view inputs. In the backbone, a dual-stream Transformer is used for feature analysis, and a GAT network is employed to fuse the features. In the model output section, a multi-task optimization objective is utilized to enhance detection performance while reducing reliance on extensive training data. Ultimately, this model achieved an accuracy of 97.79. In future research, efforts will be made to further enhance the inference efficiency of the model by employing techniques such as pruning and distillation to accelerate inference speed while minimizing hardware resource consumption. Additionally, LEGF-DST could be integrated with models like RoBERTa to construct a Mixture of Expert (MoE) systems. This framework could leverage lightweight models for initial screening while delegating low-confidence samples to LEGF-DST for secondary evaluation. Such an approach aims to balance inference efficiency and detection accuracy, effectively addressing the real-time requirements of practical applications.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the reviewers for their patient guidance and insightful feedback throughout the review process.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2024JKF13) and the Beijing Municipal Education Commission General Program of Science and Technology (No. KM202414019003).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xin Tong, Jingya Wang; data collection: Ying Yang, Tian Peng; analysis and interpretation of results: Xin Tong, Ying Yang, Hanming Zhai; draft manuscript preparation: Xin Tong, Guangming Ling. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets are available at https://doi.org/10.1145/3372297.3417257(accessed on 20 July 2023).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. M. Taufiq Nuruzzaman, C. Lee, M. F. A. Abdullah, and D. Choi, “Simple SMS spam filtering on independent mobile phone,” Secur. Commun. Netw., vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 1209–1220, 2012. doi: 10.1002/sec.577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. T. P. Ho, H. -S. Kang, and S. -R. Kim, “Graph-based KNN algorithm for spam SMS detection,” J. Univers. Comput. Sci., vol. 19, no. 16, pp. 2404–2419, 2013. [Google Scholar]

3. N. K. Nagwani and A. Sharaff, “SMS spam filtering and thread identification using bi-level text classification and clustering techniques,” J. Inf. Sci., vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 75–87, 2017. doi: 10.1177/0165551515616310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. M. V. Aragao, E. P. Frigieri, C. A. Ynoguti, and A. P. Paiva, “Factorial design analysis applied to the performance of SMS anti-spam filtering systems,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 64, pp. 589–604, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2016.08.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. M. A. Abid, S. Ullah, M. A. Siddique, M. F. Mushtaq, W. Aljedaani and F. Rustam, “Spam SMS filtering based on text features and supervised machine learning techniques,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 81, no. 28, pp. 39853–39871, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s11042-022-12991-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. T. Xia and X. Chen, “A discrete hidden markov model for SMS spam detection,” Appl. Sci., vol. 10, no. 14, 2020, Art. no. 5011. doi: 10.3390/app10145011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. S. Kumar and S. Gupta, “Legitimate and spam sms classification employing novel ensemble feature selection algorithm,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 83, no. 7, pp. 19897–19927, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s11042-023-16327-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Z. Ilhan Taskin, K. Yildirak, and C. H. Aladag, “An enhanced random forest approach using coclust clustering: MIMIC-III and SMS spam collection application,” J. Big Data, vol. 10, no. 1, 2023, Art. no. 38. doi: 10.1186/s40537-023-00720-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. H. Mamdouh Farghaly and T. Abd El-Hafeez, “A high-quality feature selection method based on frequent and correlated items for text classification,” Soft Comput., vol. 27, no. 16, pp. 11259–11274, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s00500-023-08587-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. K. Juneja et al., “Two-phase fuzzy feature-filter based hybrid model for spam classification,” J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci., vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 10339–10355, 2022. [Google Scholar]

11. O. Abayomi-Alli, S. Misra, and A. Abayomi-Alli, “A deep learning method for automatic SMS spam classification: Performance of learning algorithms on indigenous dataset,” Concurr. Comput., vol. 34, no. 17, 2022, Art. no. e6989. doi: 10.1002/cpe.6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. P. K. Roy, J. P. Singh, and S. Banerjee, “Deep learning to filter SMS spam,” Future Gener. Comput. Syst., vol. 102, pp. 524–533, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2019.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. T. Xia and X. Chen, “Category-learning attention mechanism for short text filtering,” Neurocomputing, vol. 510, pp. 15–23, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2022.08.076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. J. Yao, C. Wang, C. Hu, and X. Huang, “Chinese spam detection using a hybrid BiGRU-CNN network with joint textual and phonetic embedding,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 15, 2022, Art. no. 2418. doi: 10.3390/electronics11152418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Z. Lan, “ALBERT: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations,” 2019, arXiv:1909.11942. [Google Scholar]

16. Y. Liu, “RoBERTa: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach,” 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

17. Y. Sun et al., “ERNIE: Enhanced representation through knowledge integration,” 2019, arXiv:1904.09223. [Google Scholar]

18. X. Jiao et al., “TinyBERT: Distilling BERT for natural language understanding,” in Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, pp. 4163–4174. [Google Scholar]

19. X. Liu, H. Lu, and A. Nayak, “A spam transformer model for SMS spam detection,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 80253–80263, 2021. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3081479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. A. Ghourabi and M. Alohaly, “Enhancing spam message classification and detection using transformer-based embedding and ensemble learning,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 8, 2023, Art. no. 3861. doi: 10.3390/s23083861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. X. Zhang, R. Huang, L. Jin, and F. Wan, “A BERT-GCN-based detection method for FBS telecom fraud Chinese SMS texts,” in 2023 4th Int. Conf. Intell. Comput. Human-Comput. Interaction (ICHCI), IEEE, 2023, pp. 448–453. [Google Scholar]

22. P. Gao and L. Zhang, “Chinese fraudulent text message detection based on graph neural networks,” in 2024 6th Int. Conf. Commun., Inform. Syst. Comput. Eng. (CISCE), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1078–1081. [Google Scholar]

23. C. Oswald, S. E. Simon, and A. Bhattacharya, “SpotSpam: Intention analysis-driven SMS spam detection using bert embeddings,” ACM Trans. Web (TWEB), vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 1–27, 2022. doi: 10.1145/3538491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. J. Achiam et al., “GPT-4 technical report,” 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

25. J. Cui, Z. Li, Y. Yan, B. Chen, and L. Yuan, “Chatlaw: Open-source legal large language model with integrated external knowledge bases,” 2023, arXiv:2306.16092. [Google Scholar]

26. S. Wu et al., “BloombergGPT: A large language model for finance,” 2023, arXiv:2303.17564. [Google Scholar]

27. K. Zhang et al., “A generalist vision-language foundation model for diverse biomedical tasks,” Nat. Med., pp. 1–13, 2024. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03185-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. H. Wang et al., “HuaTuo: Tuning llama model with chinese medical knowledge,” 2023, arXiv:2304.06975. [Google Scholar]

29. D. Demszky et al., “Using large language models in psychology,” Nat. Rev. Psychol., vol. 2, no. 11, pp. 688–701, 2023. doi: 10.1038/s44159-023-00241-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. C. Zhang, J. Chen, J. Li, Y. Peng, and Z. Mao, “Large language models for human-robot interaction: A review,” Biomimetic Intell. Robot., 2023, Art. no. 100131. doi: 10.1016/j.birob.2023.100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Z. Mao, R. Kobayashi, H. Nabae, and K. Suzumori, “Large language model-empowered multimodal strain sensory system for shape recognition, monitoring, and human interaction of tensegrity,” 2024, arXiv:2406.10264. [Google Scholar]

32. G. Sahu, P. Rodriguez, I. Laradji, P. Atighehchian, D. Vazquez and D. Bahdanau, “Data augmentation for intent classification with off-the-shelf large language models,” in Proc. 4th Workshop NLP Conversational AI, 2022, pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

33. J. Ye et al., “LLM-DA: Data augmentation via large language models for few-shot named entity recognition,” 2024, arXiv:2402.14568. [Google Scholar]

34. Y. Wu, K. Mao, Y. Zhang, and J. Chen, “CALLM: Enhancing clinical interview analysis through data augmentation with large language models,” IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform., 2024. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2024.3435085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. J. Lai et al., “RumorLLM: A rumor large language model-based fake-news-detection data-augmentation approach,” Appl. Sci., vol. 14, no. 8, 2024, Art. no. 3532. doi: 10.3390/app14083532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. L. Yao, C. Mao, and Y. Luo, “Graph convolutional networks for text classification,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 7370–7377, 2019. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33017370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. H. Zhang and J. Zhang, “Text graph transformer for document classification,” in Conf. Empir. Methods Nat. Lang. Process. (EMNLP), 2020. [Google Scholar]

38. Y. Lin et al., “BERTGCN: Transductive text classification by combining GNN and BERT,” in Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, 2021, pp. 1456–1462. [Google Scholar]

39. X. Liu, X. You, X. Zhang, J. Wu, and P. Lv, “Tensor graph convolutional networks for text classification,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 8409–8416, 2020. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v34i05.6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. L. Ouyang et al., “Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback,” in Proc. 36th Int. Conf. Neural Inform. Process. Syst., 2022, pp. 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

41. J. Wei and K. Zou, “EDA: Easy data augmentation techniques for boosting performance on text classification tasks,” in Proc. 2019 Conf. Empirical Methods Nat. Lang. Process. 9th Int. Joint Conf. Nat. Lang. Proc. (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 2019, pp. 6382–6388. [Google Scholar]

42. T. GLM. et al., “ChatGLM: A family of large language models from GLM-130B to GLM-4 all tools,” 2024, arXiv:2406.12793. [Google Scholar]

43. A. Yang et al., “Baichuan 2: Open large-scale language models,” 2023, arXiv:2309.10305. [Google Scholar]

44. J. Su, M. Ahmed, Y. Lu, S. Pan, W. Bo and Y. Liu, “RoFormer: Enhanced transformer with rotary position embedding,” Neurocomputing, vol. 568, 2024, Art. no. 127063. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2023.127063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. A. Vaswani, “Attention is all you need,” in Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst., 2017. [Google Scholar]

46. P. Veličković, G. Cucurull, A. Casanova, A. Romero, P. Lio and Y. Bengio, “Graph attention networks,” 2017, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

47. P. Khosla et al., “Supervised contrastive learning,” Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst., vol. 33, pp. 18661–18673, 2020. [Google Scholar]

48. Y. Zhang et al., “Lies in the air: Characterizing fake-base-station spam ecosystem in China,” in Proc. 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conf. Comput. Commun. Secur., 2020, pp. 521–534. [Google Scholar]

49. L. Prokhorenkova, G. Gusev, A. Vorobev, A. V. Dorogush, and A. Gulin, “CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features,” in Proc. 32nd Int. Conf. Neural Inform. Process. Syst., 2018, pp. 6639–6649. [Google Scholar]

50. Y. Zhang and B. C. Wallace, “A sensitivity analysis of (and practitioners’ guide to) convolutional neural networks for sentence classification,” in Proc. Eighth Int. Joint Conf. Nat. Lang. Process., 2017, pp. 253–263. [Google Scholar]

51. R. Johnson and T. Zhang, “Deep pyramid convolutional neural networks for text categorization,” in Proc. 55th Annual Meet. Assoc. Comput. Linguist., 2017, pp. 562–570. [Google Scholar]

52. J. Chung, C. Gulcehre, K. Cho, and Y. Bengio, “Empirical evaluation of gated recurrent neural networks on sequence modeling,” in NIPS 2014 Workshop Deep Learn., 2014. [Google Scholar]

53. S. Akkaradamrongrat, P. Kachamas, and S. Sinthupinyo, “Text generation for imbalanced text classification,” in 2019 16th Int. Joint Conf. Comput. Sci. Soft. Eng. (JCSSE), IEEE, 2019, pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools