Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Dynamic Social Network Graph Anonymity Scheme with Community Structure Protection

Guangxi Key Laboratory of Trusted Software, Guilin University of Electronic Technology, Guilin, 541004, China

* Corresponding Author: Liang Chang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 3131-3159. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.059201

Received 30 September 2024; Accepted 26 November 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

Dynamic publishing of social network graphs offers insights into user behavior but brings privacy risks, notably re-identification attacks on evolving data snapshots. Existing methods based on -anonymity can mitigate these attacks but are cumbersome, neglect dynamic protection of community structure, and lack precise utility measures. To address these challenges, we present a dynamic social network graph anonymity scheme with community structure protection (DSNGA-CSP), which achieves the dynamic anonymization process by incorporating community detection. First, DSNGA-CSP categorizes communities of the original graph into three types at each timestamp, and only partitions community subgraphs for a specific category at each updated timestamp. Then, DSNGA-CSP achieves intra-community and inter-community anonymization separately to retain more of the community structure of the original graph at each timestamp. It anonymizes community subgraphs by the proposed novel -composition method and anonymizes inter-community edges by edge isomorphism. Finally, a novel information loss metric is introduced in DSNGA-CSP to precisely capture the utility of the anonymized graph through original information preservation and anonymous information changes. Extensive experiments conducted on five real-world datasets demonstrate that DSNGA-CSP consistently outperforms existing methods, providing a more effective balance between privacy and utility. Specifically, DSNGA-CSP shows an average utility improvement of approximately 30% compared to TAKG and CTKGA for three dynamic graph datasets, according to the proposed information loss metric IL.Keywords

With the rise of online social network platforms (e.g., Google, Twitter, and Facebook), people can interact and make friends with other like-minded people. During the interaction, the network-centric graph data is formed. The data mining and data analysis of social networks for third parties can yield rich and accurate information such as users’ interests. However, the original social network graph often contains users’ sensitive information (e.g., hobbies, relationships, and profiles). Directly releasing the real graph data jeopardizes the users’ privacy, as Ferri et al. pointed out in [1], 90% of users are concerned about their sensitive information being leaked. For instance, malicious adversaries can obtain users’ private information by identifying unique identifiers (e.g., names) that represent their identities. Therefore, it is crucial to anonymize users’ identities and their edge relationships before publishing the social network graphs [2].

The common anonymization methods mainly consist of clustering generalization [3], graph editing [4], and differential privacy [5–7]. The clustering generalization divides all nodes in the original graph into multiple groups and anonymizes nodes in each group. The graph editing achieves the anonymization of the original graph by modifying nodes and edges randomly. The differential privacy perturbs the original graph by adding the appropriate noisy nodes/edges. However, these methods primarily concentrate on the anonymization of static graphs. Social network graphs are evolving over time, with new nodes, edges, and changing relationships between users. This evolution introduces a unique challenge, i.e., the original graph at each timestamp is anonymized independently using a static graph anonymization method. Although the nodes and edges in each anonymized graph are protected, adversaries with strong background knowledge can still perform differential analysis on the sequence of published anonymized graphs, allowing them to re-identify nodes or infer sensitive relationships. For instance, if an adversary has access to a sequence of anonymized graphs over a period of time and knows that a specific user was added at a certain timestamp, he/she can compare the anonymized graph at the last timestamp with that at the current timestamp to re-identify the identity of the newly introduced node (see adversary model in Section 3.1 for more details).

Therefore, to achieve effective dynamic anonymization of social network graphs, we need to solve the following challenges:

i) Complicated and cumbersome anonymization process. Existing researches [8,9] mitigate re-identification attacks on evolving graph snapshots using clustering generalization, that is, nodes are grouped at each timestamp and connected within groups to meet

ii) Dynamic protection of community structures. Existing methods neglect the dynamic protection of community structures [10,11], focusing only on nodes and edges, which reduces the utility of anonymized graphs. For instance, people cluster by interests, and these communities change over time with shifting interests [12]. Without dynamic protection of community structures, anonymized graph structures can diverge from the original, leading to low utility.

iii) Precise measure of graph utility. Using a single metric cannot fully represent the utility of an anonymized graph. Most researchers often use multiple metrics to assess how closely the anonymized graph resembles the original, but these metrics only capture differences from a single perspective.

To address the above challenges, we propose DSNGA-CSP, a dynamic social network graph anonymity scheme with community structure protection. At each updated timestamp, DSNGA-CSP categorizes communities based on changes in the original graph and only partitions community subgraphs for a specific category, avoiding redundant operations. Intra-community nodes and edges are anonymized using a novel

The main contributions are as follows:

1) A dynamic graph anonymization scheme (DSNGA-CSP) is proposed, which protects nodes’ identities and edge relationships in the original graph for each timestamp, and it achieves the dynamic protection of original graph structures.

2) A novel

3) A new information loss metric is proposed to measure the utility of anonymized dynamic graphs from two perspectives, and it is more accurate than other similar alternatives.

4) All experiments are completed on multiple real datasets, and the measured results demonstrate the effectiveness of DSNGA-CSP.

The remaining parts of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 presents related work. Section 3 gives preliminaries. Section 4 introduces the proposed DSNGA-CSP scheme in detail. Section 5 presents the experimental comparison and analysis. Section 6 discusses the implications and limitations of our work. Section 7 gives the conclusion and future work.

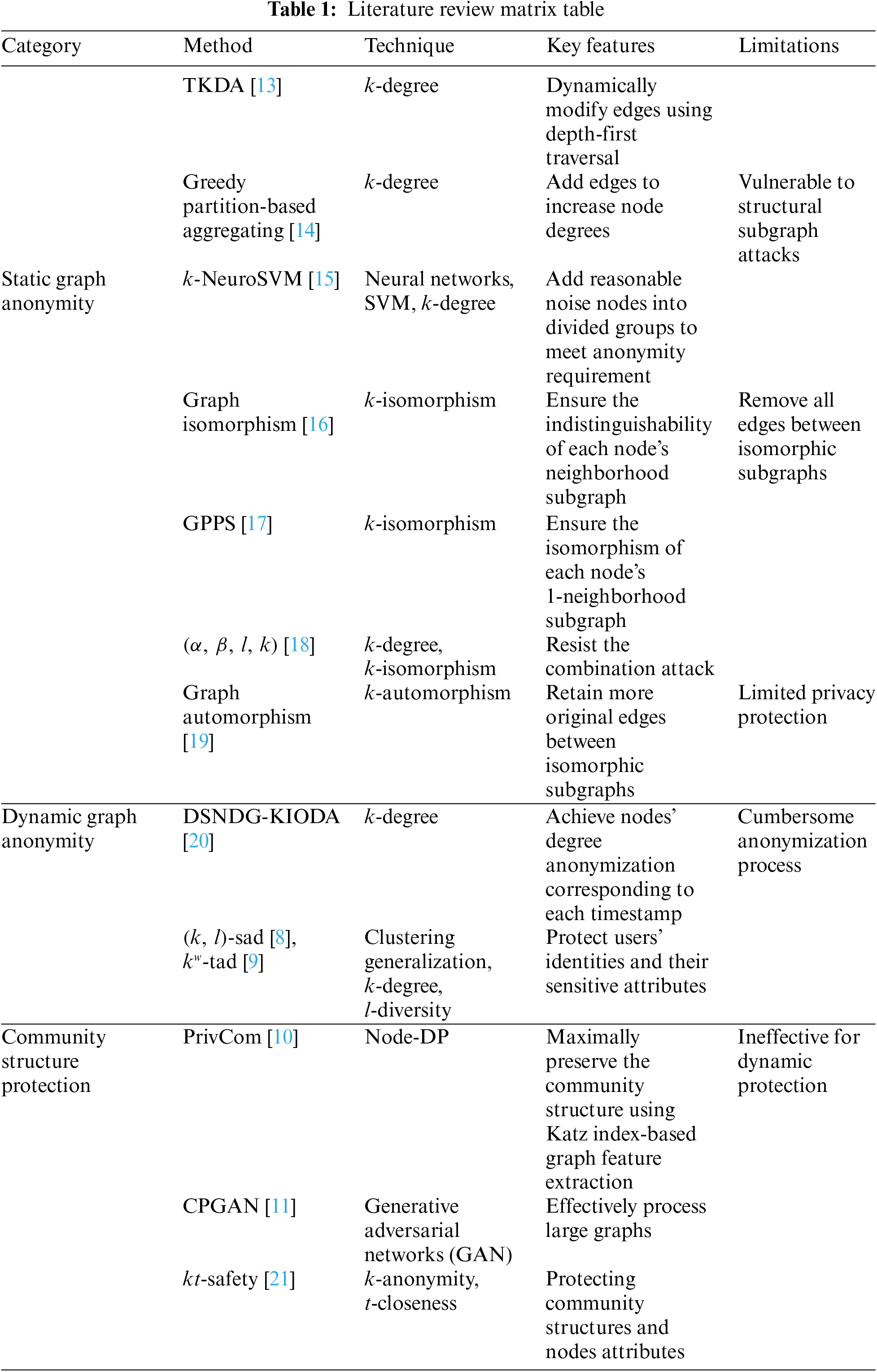

In this section, we review related works on privacy-preserving static graph anonymity, privacy-preserving dynamic graph anonymity, and community structure protection. We summarize these works in a literature review matrix table (Table 1, which provides a comparison of the main techniques, key features, and limitations.

Privacy-preserving data publishing has emerged as a prominent research focus [22]. Currently, the anonymous publishing of social network graphs has received a lot of attention and attracted many researchers to develop advanced methods. k-anonymity [23], as a promising technique, ensures that each node in the anonymized graph is indistinguishable from at least

The above researches indicate that the

In real life, social network graphs are dynamic. The static graph anonymization methods mentioned above cannot be directly applied to dynamic graph anonymization. The main reason is that the adversary can easily re-identify nodes’ identities and edge relationships through differences between anonymized graphs at adjacent timestamps. As the research presented in [20], Zhang et al. proposed DSNDG-KIODA, which only considers nodes’ degree anonymization at the corresponding timestamp. The newly added/removed nodes/edges can be re-identified by differences in node structures between two anonymized graphs at adjacent timestamps. To address this issue, Hoang et al. proposed two time-varying attribute degree anonymity methods (

2.3 Community Structure Protection

The community structure is an important feature of a social network graph, and it is necessary to preserve the structural features of the original graph while achieving the anonymization of nodes’ identities and edge relationships. Zhang et al. [10] proposed a graph perturbation method (PrivCom) based on node-level differential privacy (node-DP), which maximally preserves the community structure of the original graph by a Katz index-based graph feature extraction algorithm. Based on deep learning techniques, Xiang et al. [11] proposed a graph generation model (CPGAN) with community structure protection, and this model presents good scalability on large graphs. With the aim of protecting community structures and node attributes, Ren et al. [21] proposed a

Based on the above issues, this paper proposes a dynamic social network graph anonymity scheme with community structure protection (DSNGA-CSP). DSNGA-CSP achieves anonymization of nodes’ identities and edge relationships. To improve the utility of anonymized dynamic graphs, we preserve more structural information from the original graph at each timestamp. Additionally, a new information loss metric is defined to measure the utility of anonymized dynamic graphs more accurately.

This section introduces the adversary model with a special example and provides the problem definition.

Given an original graph sequence

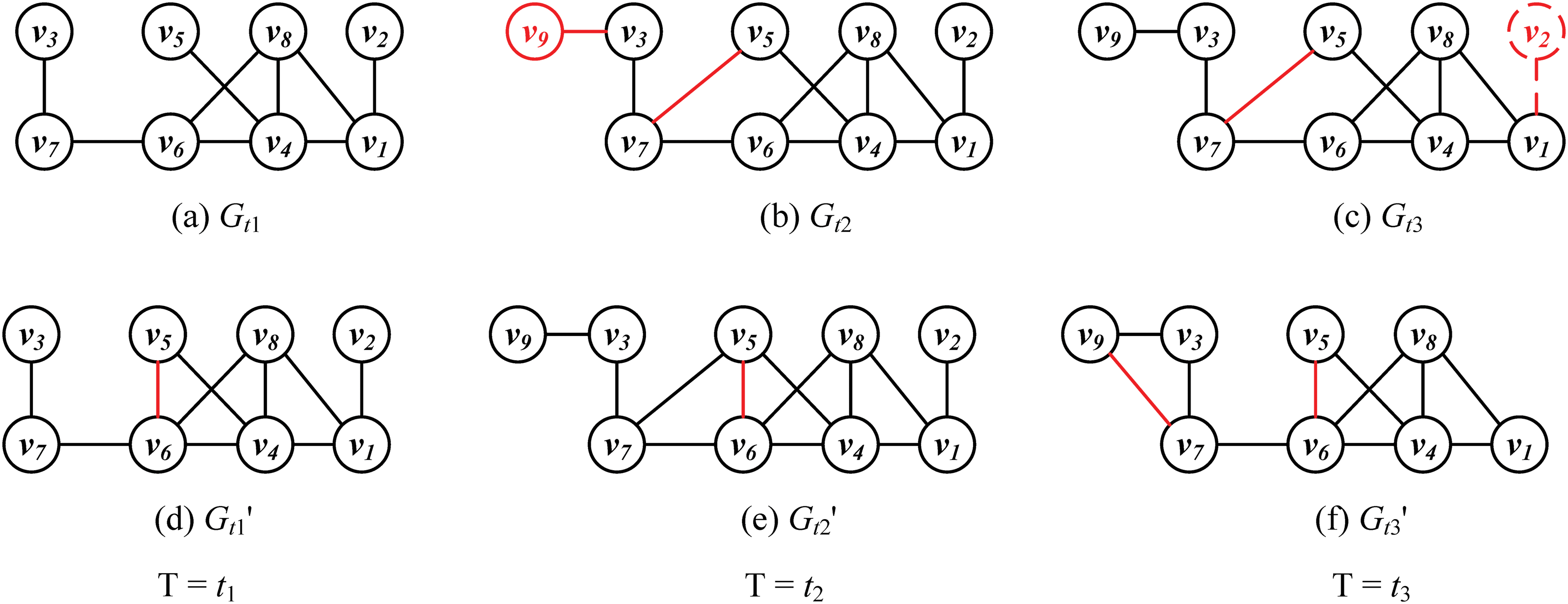

Fig. 1 represents a 2-degree anonymous graph sequence being published during time periods

Figure 1: A 2-degree anonymous graph sequence is published during the time periods

Problem statement. Given

This paper considers the protection of the original graph structure, so we first detect communities of the original graph at each timestamp. Then, based on graph isomorphism and graph automorphism, we obtain

Definition 1 (Graph isomorphism). Let

Definition 2 (Graph automorphism). Given a graph

For an automorphic community subgraph, its anonymity level depends on the number of isomorphic subgraphs (i.e.,

Definition 3 (K-automorphic graph). Given a graph

In this paper, we achieve the anonymous publishing of

Definition 4 (Anonymous publishing of dynamic graphs). Let

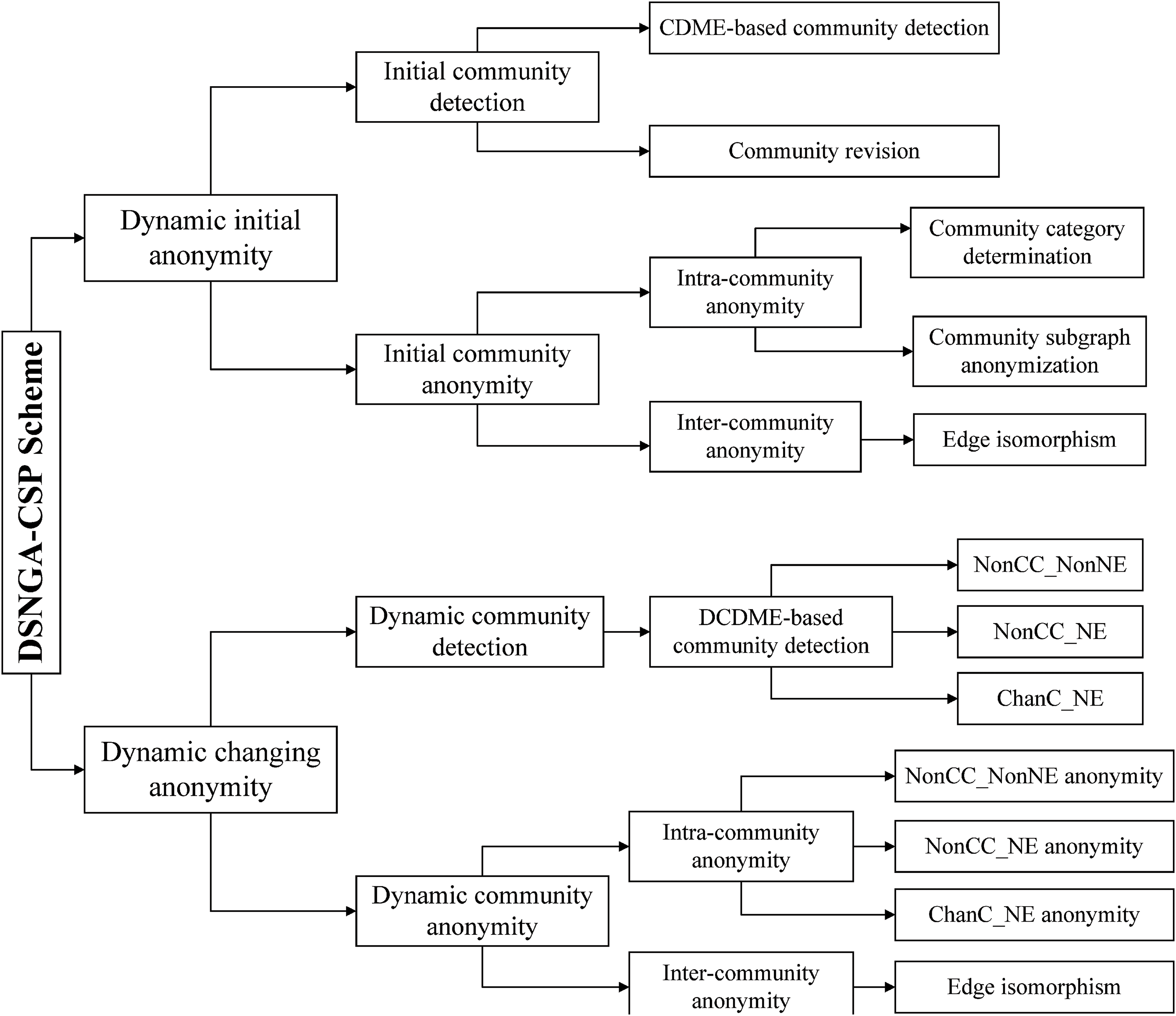

This section introduces the proposed DSNGA-CSP scheme in detail. As shown in Fig. 2, DSNGA-CSP mainly consists of the following two stages:

Phase 1: Dynamic initial anonymity. In this phase, all nodes in

Phase 2: Dynamic changing anonymity. For each updated timestamp, all nodes in the original graph are detected as multiple disjoint communities using the DCDME algorithm [24]. Based on the changes in community structure caused by changed nodes and edges mentioned in [24], we divide the detected communities into three categories: 1) Communities not involving changed nodes and edges (

Figure 2: The flowchart of DSNGA-CSP

In this section, the anonymized graph

4.1.1 Initial Community Detection

The CDME algorithm [24] is used to detect the community structure of

1) For the first method, if the number of nodes in a community

2) For the second method, if the number of nodes in

At the initial timestamp, we assume the ultimately detected communities are represented as

4.1.2 Initial Community Anonymity

This subsection anonymizes all community subgraphs corresponding to

The key steps of Algorithm 1 are: 1) Since the graph partitioning method can affect the utility of the anonymized graph directly, this paper partitions all community subgraphs by two graph partitioning algorithms [25]: METIS_PartGraphKway and METIS_PartGraphRecursive (lines 1–2). 2) We determine the category of the current community based on

Function

Three categories of community subgraphs are anonymized as follows:

a) For each community in

b) For each community in

In the partition phase,

In the isomorphism phase,

Function

Function

In the composition phase, the inter-block crossing edges achieve isomorphism anonymization. Algorithm 3 describes the details, and the key steps involved are: 1) Obtain all inter-block crossing edges (lines 1–5). 2) For each cross edge, find the mapping positions of its two endpoints in the two blocks. Then, connect two nodes with the same mapping positions in the other pairs of blocks with the same block interval (lines 6–18). 3) After anonymizing all crossing edges, the anonymized community subgraph corresponding to

Algorithm 4 describes the process of inter-community anonymity. The edges between non-partitioned communities, as well as those between non-partitioned communities and partitioned communities, achieve the inter-community 2-isomorphism anonymity. The edges between partitioned communities achieve the inter-community

1) Obtain all the edges between communities (lines 1–5). 2) The edges between three categories of communities achieve isomorphism anonymity, respectively (lines 6–25).

i) The edges between non-partitioned communities are anonymized by the function

ii) The edges between non-partitioned and partitioned communities are anonymized by the function

iii) The edges between partitioned communities are anonymized by the function

3) Obtain the anonymized graph

4.2 Dynamic Changing Anonymity

In this section, the anonymized graph

4.2.1 Dynamic Community Detection

This section detects multiple disjoint communities at timestamp

Before detecting communities, the isomorphic nodes and edges related to removed nodes and edges at timestamp

1) The original graph structure may cause changes from these cases: adding nodes between communities, adding edges between communities, deleting nodes in a community, deleting nodes between communities, and deleting edges in a community. Thus, the subgraph formed by these changes at timestamp

2) The original graph structure may not cause changes from these cases: adding edges in a community, adding nodes in a community, and deleting edges between communities. Since some communities involved in the above changes have satisfied the requirement for the number of nodes within the community at the timestamp

3) The remaining communities involved nothing about changed nodes/edges are recorded as

Assume the communities at timestamp

4.2.2 Dynamic Community Anonymity

For the communities in

For intra-community anonymity, the community subgraphs formed by

1) For each community in

2) For each community in

3) For each community in

For inter-community anonymity, the edges between communities in

1) Merge

2) Since the community subgraphs formed by

3) The communities in

This section provides a new information loss metric. The main reason is: 1) the single graph metric cannot fully measure the information loss of an anonymized graph; 2) current research on measuring the utility of anonymized graphs is almost only from a single perspective, which is the difference between the anonymized graph and the original graph. Thus, we define a new metric from two perspectives: original information preservation and anonymous information change. The former measures the retention of original information in the anonymized graph, while the latter measures the information changes required to achieve anonymity. To unify measurement, this paper takes the inverse of anonymous information change and combines it with original information preservation to determine the information loss of an anonymized graph. The higher the defined metric, the smaller the distortion of the anonymized graph.

Definition 5 (Information loss). At timestamp

where

According to Definition 5, the information loss of the anonymized graphs over

For IL, it reflects the average information loss of

This section proves that DSNGA-CSP can achieve the anonymity of dynamic social network graphs. Specifically, we prove that anonymized graphs obtained by DSNGA-CSP over

Theorem 1. Let

Proof of Theorem 1. Taking

According to Theorem 1, this section provides the probability that the anonymized dynamic graphs defend against re-identification attacks, and the lemma is described as follows:

Lemma 1. DSNGA-CSP can resist re-identification attacks from adversaries. If an adversary only has access to a real node and its edge information within the community or real edge information between communities, the probability that he re-identifies the node’s identity and edge relationships does not exceed

Proof of Lemma 1. Given

In this section, the effectiveness of the proposed DSNGA-CSP scheme is evaluated through experimental comparison and analysis. Section 5.1 introduces datasets. Section 5.2 presents metrics. Section 5.3 explores the performance of DSNGA-CSP.

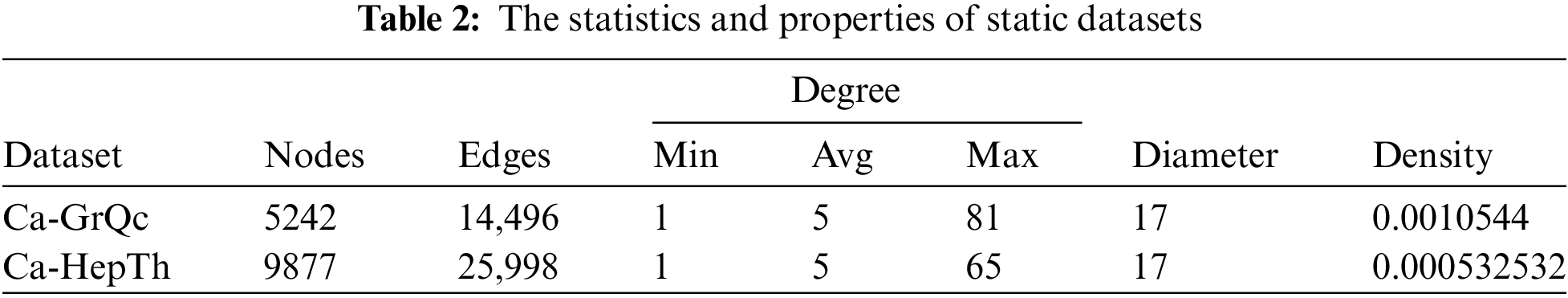

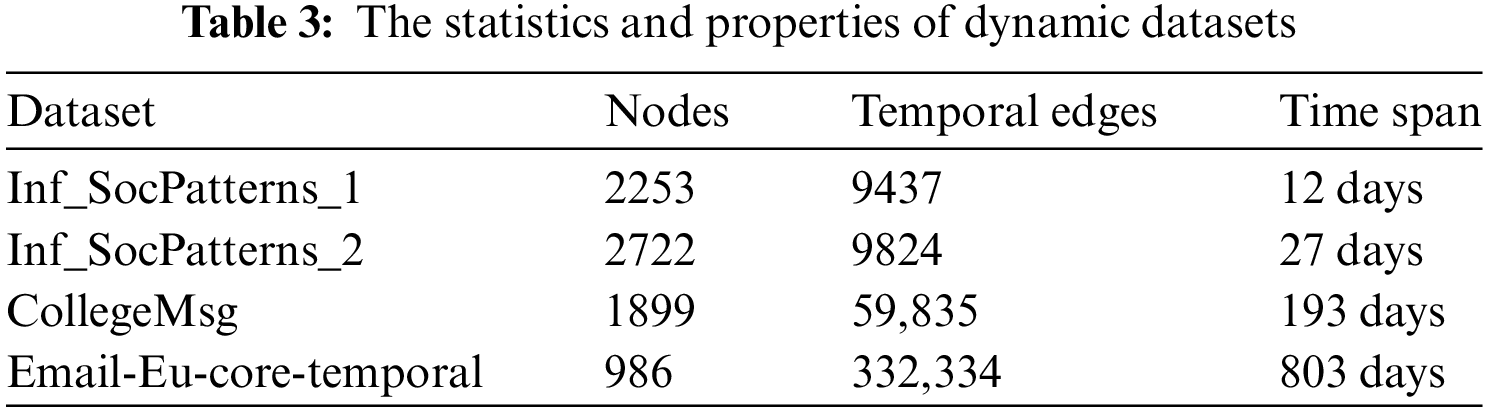

Five real-world datasets are used in this paper, consisting of two static graph datasets and three dynamic graph datasets. The primary reason for choosing these datasets is their extensive use in prior studies, making them suitable benchmarks for comparison. The two static datasets, with well-documented properties and distinct community structures, help evaluate the effectiveness of our anonymization method in protecting community structures. The three dynamic datasets cover diverse social network scenarios, with varying time spans and edge changes. Shorter time span datasets simulate frequent social changes, while longer ones evaluate performance under long-term dynamics. These datasets allow us to test DSNGA-CSP’s effectiveness, particularly in resisting re-identification attacks and ensuring utility across different temporal characteristics. The statistics and properties of these datasets are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Static graph datasets

1) Ca-GrQc [27]: a collaboration network about Arxiv General Relativity. It denotes an author

2) Ca-HepTh [27]: a collaboration network about Arxiv High Energy Physics Theory. An undirected edge

Dynamic graph datasets

1) Infectious SocioPatterns [28]: an infectious socio patterns dynamic contact network. An edge

2) Email-Eu-core-temporal [29]: an email communication network spanning 803 days. An edge

3) CollegeMsg [30]: a college messaging temporal network spanning 193 days. An edge

Data preprocessing. To better evaluate DSNGA-CSP, the aforementioned datasets are preprocessed by the following steps: 1) Converting directed graphs to undirected graphs; 2) Removing duplicate edges and loops; 3) Avoiding publishing impractical graphs with very few edges at certain timestamps, each of three dynamic graphs is split into 20 new graphs by merging continuous raw graphs, and all generated new graphs have a similar number of edges.

This section introduces utility metrics and a privacy metric, which are used to evaluate the performance of anonymized graphs obtained by DSNGA-CSP. The utility metrics include two categories: graph analysis metrics and community structure metrics. The first focuses on general graph characteristics, while the second focuses on graph structural features. The first focuses on general graph characteristics to ensure fundamental structural properties like connectivity and centrality are preserved, which is essential for maintaining graph utility in various network analyses. The second focuses on graph structural features, key features representing clusters of users with similar interests or strong interactions. Preserving these structures ensures the anonymized graph remains useful for community-related studies. The privacy metric measures the uncertainty within the anonymized graph, quantifying the difficulty for adversaries to re-identify nodes or infer relationships. These metrics comprehensively evaluate both utility and privacy, providing a well-rounded understanding of the effectiveness of DSNGA-CSP. The metrics used in this paper are as follows:

Graph analysis metrics

1) Average Path Length (APL): the metric measures the average length of all shortest paths in a graph.

2) Average Clustering Coefficient (ACC): the metric is the average of the local clustering coefficients of nodes in a graph, quantifying how close the neighbors of a node are to being a clique.

3) Eigenvector Centrality (EC): the metric quantifies the importance of a node in a graph, and it depends on the neighbors connected with the node. To avoid the influence of acyclic graphs, a constant is added to the denominator position for subsequent error rate calculation.

4) Transitivity (T): the metric measures the number of triangles in a graph.

5) Average Degree (AVD): the metric measures the average degree of all nodes in a graph.

Community structure metrics

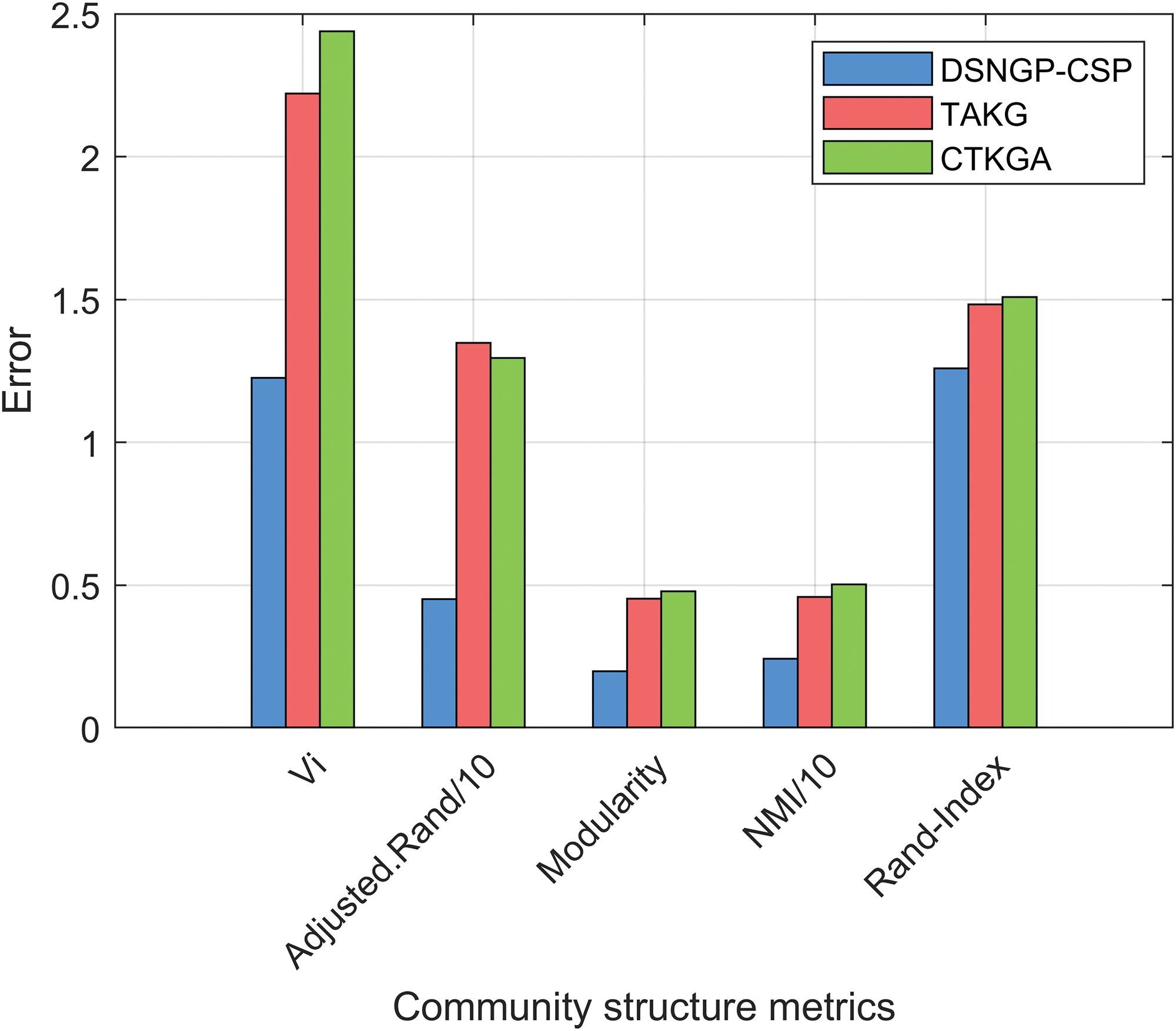

The community structure metrics used include: variation of information (VI) [31], adjusted rand index [32], normalized mutual information (NMI) [31], rand index [33], and modularity (mod) [34]. For VI and mod, the optimal value is 0, while for the rest, 1 is the optimal value. To better understand the results of the evaluation, metrics with an optimal value of 1 are inverted. Therefore, the smaller the measurement of these community structure metrics, the smaller the structural changes in the anonymized graph. Moreover, the first four metrics usually require that the two graphs being measured have the same nodes. Thus, we use the induced subgraph of the original and anonymized graphs with the same nodes to approximately measure these metrics.

Privacy metric

The privacy of the anonymized graph is assessed using a metric (i.e., Shannon entropy [35]) introduced in our previous work [36]. Entropy can be used to measure the uncertainty of the anonymized graph, thereby quantifying the degree to which the original graph is anonymized. If the anonymized graph has high uncertainty, it also has high privacy.

Implementation. To verify whether community structure protection can enhance the utility of anonymized graphs, we first evaluate our anonymization method on two static graph datasets, under scenarios involving community detection and those without. We then evaluate the performance of DSNGA-CSP on two dynamic graph datasets. All experiments are conducted on a PC with an Intel Core i5-10500 CPU, 64 GB RAM, and Windows 10 operating system. All schemes are achieved using the R programming language.

Competitors. We compare two static graph anonymity schemes using the

5.3.1 Experimental Evaluation on Static Graphs

For graph analysis metrics, an error rate between the anonymized graph and the original graph is computed to measure the utility of the anonymized graph. This error rate reflects the degree to which the anonymized graph is close to the original graph based on these metrics. Moreover, the smaller the error rate, the better the utility of the anonymized graph. The average error rate at different anonymity levels is calculated as follows:

where

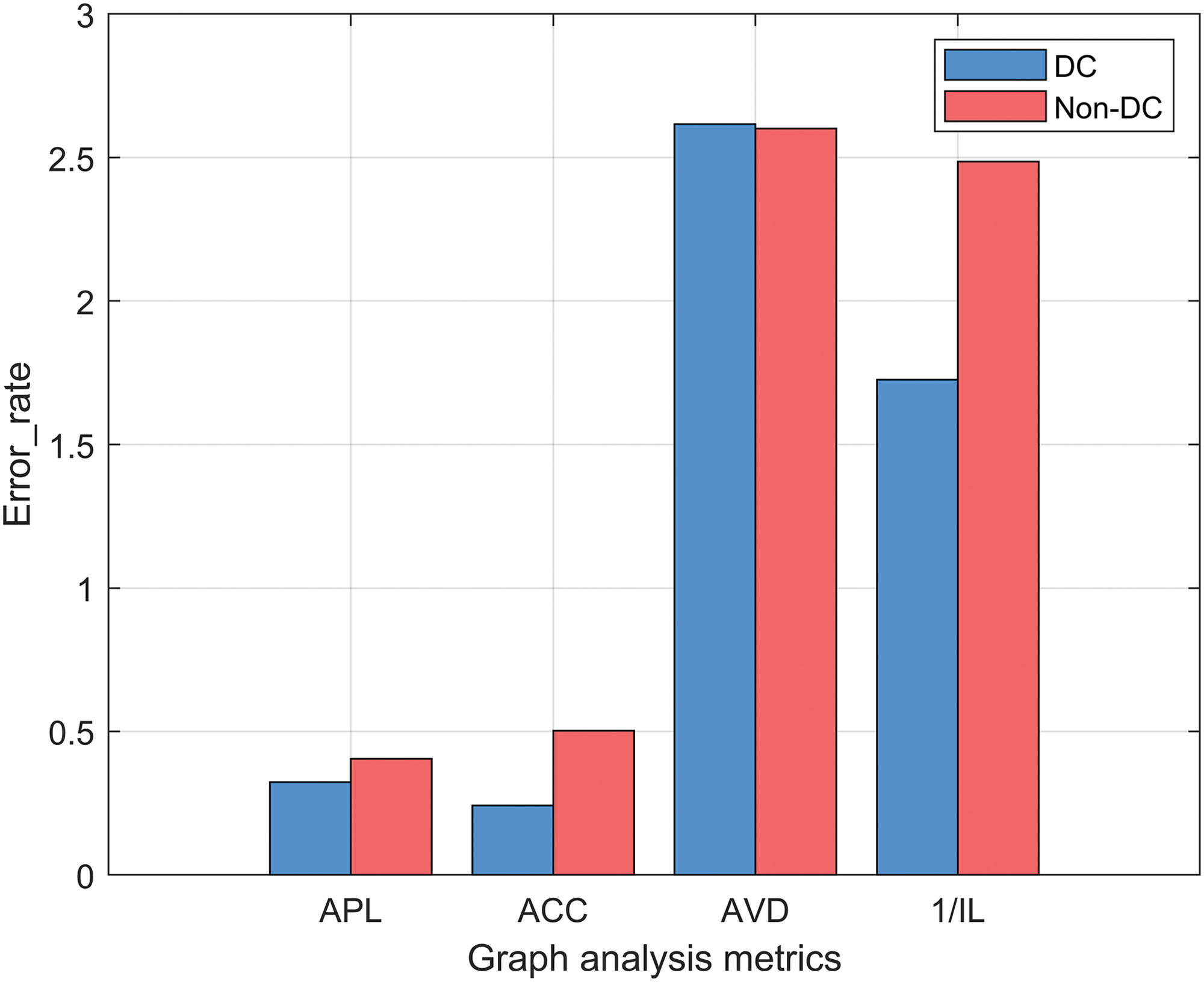

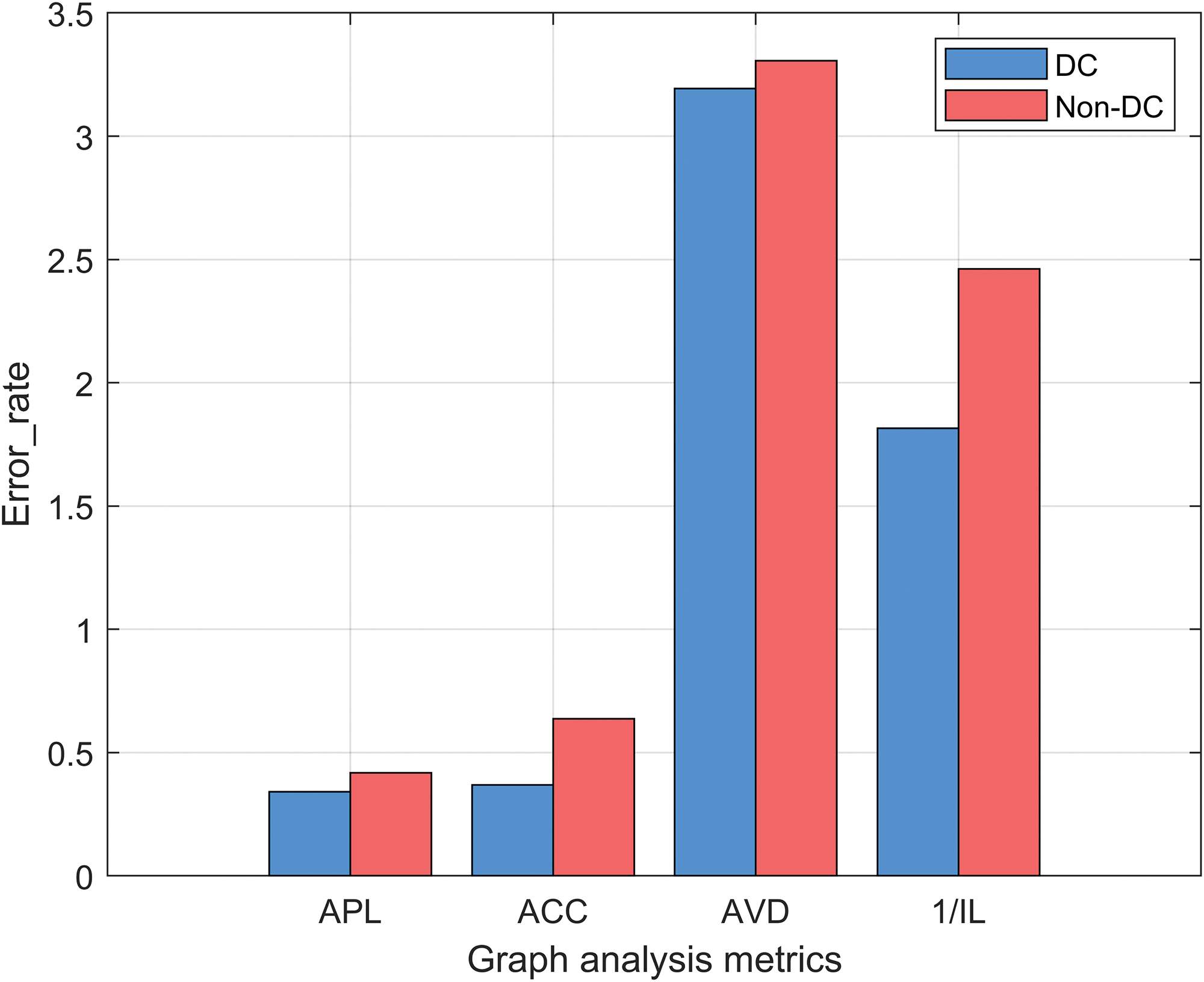

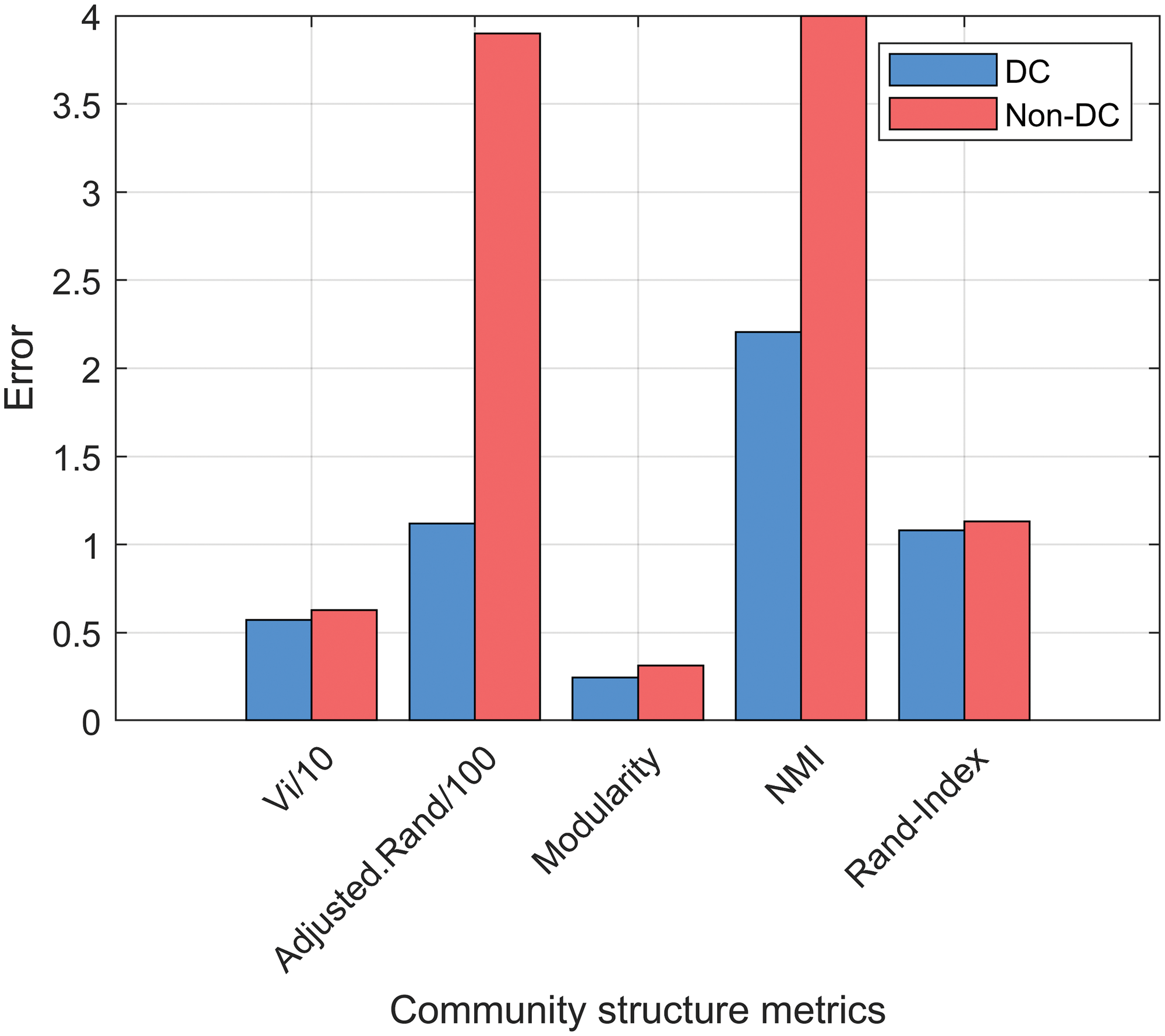

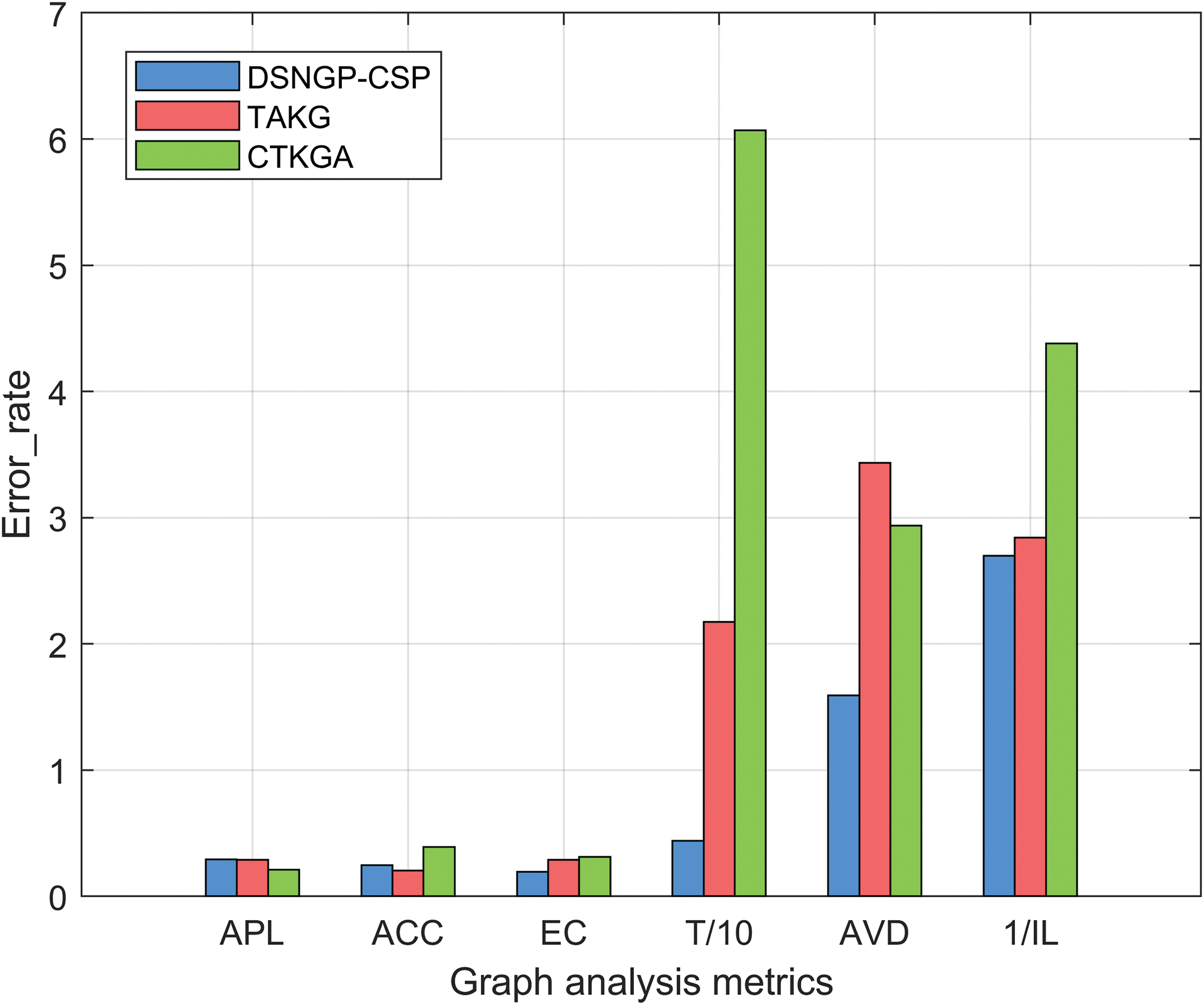

Figs. 3–6 present the experimental results of two categories of graph analysis metrics on two static graph datasets Ca-GrQc and Ca-HepTh. The horizontal axis represents the measured metrics. For graph analysis metrics, the vertical axis represents

Figure 3: Comparison of

Figure 4: Comparison of

Figure 5: Comparison of community structure metrics on Ca-GrQc dataset

Figure 6: Comparison of community structure metrics on Ca-HepTh dataset

Graph analysis metrics results. As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, the results of DC are almost entirely superior to those of Non–DC. In the Ca-GrQc dataset, the result of DC is slightly higher than that of Non–DC in terms of AVD. This is because both intra-community and inter-community edges need to achieve isomorphic anonymization in DC, which may result in more changes in nodes’ degrees. However, due to the fairly close results, the measurement difference between the two schemes can be negligible.

Community structure metrics results. As shown in Figs. 5 and 6, all results of DC are superior to those of Non–DC. It indicates that

5.3.2 Experimental Evaluation on Dynamic Graphs

For graph analysis metrics, refer to the description in Section 5.3.1. In this paper, since the anonymization of dynamic graphs sequentially publishes 20 anonymized graphs for each dataset, the average error rate for each graph analysis metric is calculated as follows:

where

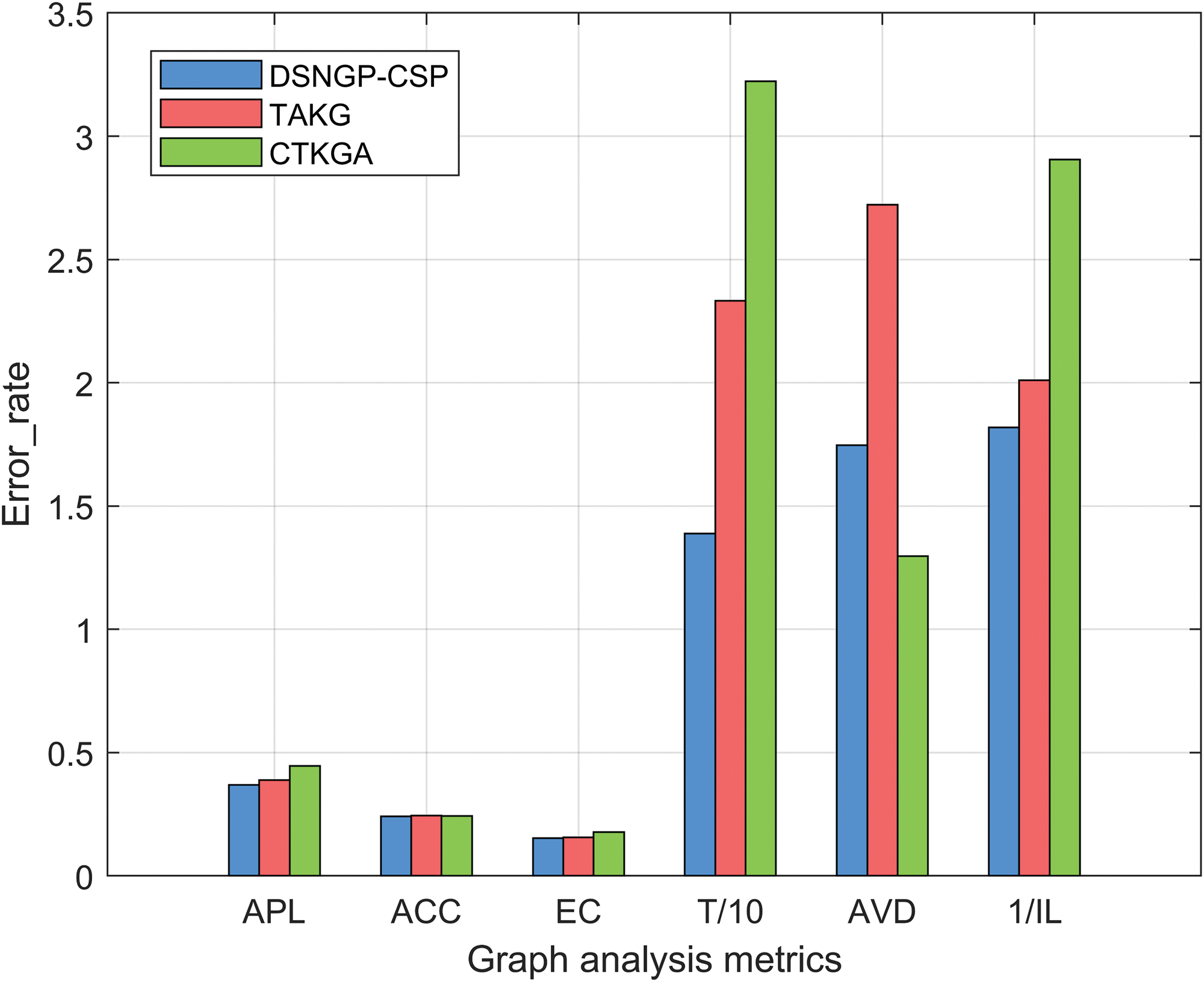

For four dynamic graph datasets, Figs. 7–10 present the experimental results of graph analysis metrics, Figs. 11–14 present the experimental results of community structure metrics, and Fig. 15 presents the experimental results of the privacy metric. For graph analysis metrics and community structure metrics, the presentation of coordinate axes refers to 5.3.1. For privacy metric, the horizontal axis represents datasets, and the vertical axis represents the average entropy at different timestamps and anonymity levels

Figure 7: Comparison of

Figure 8: Comparison of

Figure 9: Comparison of

Figure 10: Comparison of

Figure 11: Comparison of community structure metrics on Inf_SocPatterns_1 dataset

Figure 12: Comparison of community structure metrics on Inf_SocPatterns_2 dataset

Figure 13: Comparison of community structure metrics on CollegeMsg dataset

Figure 14: Comparison of community structure metrics on Email-Eu-core-temporal dataset

Figure 15: Comparison of Shannon entropy metric on four dynamic graph datasets

Graph analysis metrics results. Similar results are presented in Figs. 7 and 8 because the datasets used come from the same dynamic graph dataset. For ACC and EC, the results of DSNGA-CSP are close to those of TAKG and CTKGA. For APL, the result of DSNGA-CSP is better than that of CTKGA but slightly inferior to that of TAKG. The reason is that DSNGA-CSP removes more edges when anonymizing edges between three different categories of communities. For T and IL, DSNGA-CSP shows better results compared to TAKG and CTKGA. Notably, DSNGA-CSP maintains a number of triangles in the anonymized graph closest to the original graph, and the results of IL show that DSNGA-CSP causes fewer changes in nodes and edges compared to TAKG and CTKGA during anonymization. For AVD, the result of DSNGA-CSP is lower than that of TAKG but higher than that of CTKGA. This is because CTKGA clusters nearly all nodes in the original graph into groups with the size of

As shown in Fig. 9, for APL, the result of DSNGA-CSP is lower than that of CTKGA but slightly higher than that of TAKG, with similar analysis to that mentioned above. For the remaining metrics, the results of DSNGA-CSP show significant advantages compared with those of TAKG and CTKGA. In Fig. 10, DSNGA-CSP shows a slight disadvantage for the results of APL, but it does not significantly impact the utility of the anonymized graph. For ACC, the result of DSNGA-CSP is lower than that of CTKGA but slightly higher than that of TAKG. This is because TAKG achieves isomorphism of intra-cluster nodes by connecting all node pairs within each cluster, leading to tighter connections between intra-cluster nodes and their neighbors. However, the excessive addition of fake edges may significantly reduce the utility of the anonymized graph. For other metrics, the results of DSNGA-CSP are superior to those of TAKG and CTKGA.

Community structure metrics results. As shown in Figs. 11–14, nearly all results of DSNGA-CSP are superior to those of TAKG and CTKGA, with only a few results being close. Overall, DSNGA-CSP performs better for all community structure metrics. Additionally, it demonstrates that DSNGA-CSP can preserve more structural features of the original graph when achieving anonymous publishing of dynamic graphs. This also validates that dynamically protecting the community structure can enhance the utility of anonymized dynamic graphs.

Privacy metric results. As shown in Fig. 15, DSNGA-CSP outperforms TAKG and CTKGA on four datasets. This is because TAKG and CTKGA produce anonymized graphs where nodes have similar features, leading to smaller differences in intra-cluster and inter-cluster information. This increases the likelihood that an adversary can identify original information. Moreover, although clustering more groups in TAKG and CTKGA can make re-identification attacks more difficult, the privacy of the anonymized graphs obtained by these two schemes is inferior to that of DSNGA-CSP, due to the homogenized network structure and increased non-significant information in the anonymized graphs.

6 Discussion, Implication and Study Limitation

Summary of DSNGP-CSP. In this study, we propose a novel dynamic social network graph anonymity scheme, DSNGP-CSP, which demonstrates significant improvements in privacy protection and graph utility. Our experiments show that DSNGP-CSP effectively maintains community structures, while reducing the risk of privacy breaches compared to existing methods like TAKG and CTKGA. These findings indicate that incorporating community structure preservation into dynamic graph anonymization can enhance both privacy and graph utility, thereby overcoming a major limitation of traditional static anonymization methods.

Implications. The implications of our research are broad. Our method can be directly applied to social network platforms that need to publish anonymized graph data for research purposes, while still preserving user privacy. Furthermore, by integrating community structure preservation, our approach can also help improve the quality of downstream tasks, such as recommendation systems and social network analysis, which often rely on graph structure quality.

Study Limitations. There are two limitations in our work. Firstly, our approach relies on the pre-defined parameter

This paper proposes DSNGA-CSP, a scheme for publishing dynamic social network graphs while preserving community structure based on

Despite the advantages of

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U22A2099) and the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (YCBZ2023130).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yuanjing Hao; data collection: Mingmeng Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Yuanjing Hao, Xuemin Wang, Long Li; draft manuscript preparation: Yuanjing Hao, Liang Chang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Stanford Large Network Dataset Collection at https://snap.stanford.edu/data/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. F. Ferri, P. Grifoni, and T. Guzzo, “New forms of social and professional digital relationships: The case of Facebook,” Soc. Netw. Anal. Min., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 121–137, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s13278-011-0038-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Y. Li, M. Purcell, T. Rakotoarivelo, D. Smith, T. Ranbaduge and K. S. Ng, “Private graph data release: A survey,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 55, no. 11, pp. 1–39, 2023. doi: 10.1145/3569085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. A. Hoang, B. Carminati, and E. Ferrari, “Cluster-based anonymization of knowledge graphs,” in Applied Cryptography and Network Security, M. Conti, J. Zhou, E. Casalicchio, and A. Spognardi, Eds., Rome, Italy: Springer, 2020, vol. 12147, pp. 104–123. [Google Scholar]

4. R. K. Langari, S. Sardar, S. A. A. Mousavi, and R. Radfar, “Combined fuzzy clustering and firefly algorithm for privacy preserving in social networks,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 141, 2020, Art. no. 112968. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. H. Huang, D. Zhang, F. Xiao, K. Wang, J. Gu and R. Wang, “Privacy-preserving approach PBCN in social network with differential privacy,” IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag., vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 931–945, 2020. doi: 10.1109/TNSM.2020.2982555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. X. Jian, Y. Wang, and L. Chen, “Publishing graphs under node differential privacy,” IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 4164–4177, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2021.3128946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. N. Fu, W. Ni, S. Zhang, L. Hou, and D. Zhang, “GC-NLDP: A graph clustering algorithm with local differential privacy,” Comput. Secur., vol. 124, 2023, Art. no. 102967. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2022.102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. A. Hoang, B. Carminati, and E. Ferrari, “Time-aware anonymization of knowledge graphs,” ACM Trans. Priv. Secur., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 1–36, 2022. doi: 10.1145/3563694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. A. T. Hoang, B. Carminati, and E. Ferrari, “Privacy-preserving sequential publishing of knowledge graphs,” in 37th IEEE Int. Conf. Data Eng. (ICDE), Chania, Greece, IEEE, 2021, pp. 2021–2026. [Google Scholar]

10. S. Zhang, W. Ni, and N. Fu, “Community preserved social graph publishing with node differential privacy,” 20th IEEE Int. Conf. Data Min. (ICDM), Sorrento, Italy: IEEE, 2020, pp. 1400–1405. [Google Scholar]

11. S. Xiang, D. Cheng, J. Zhang, Z. Ma, X. Wang and Y. Zhang, “Efficient learning-based community-preserving graph generation,” in 38th IEEE Int. Conf. Data Eng. (ICDE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, IEEE, 2022, pp. 1982–1994. [Google Scholar]

12. S. Ranjkesh, B. Masoumi, and S. M. Hashemi, “A novel robust memetic algorithm for dynamic community structures detection in complex networks,” World Wide Web (WWW), vol. 27, no. 1, 2024, Art. no. 3. doi: 10.1007/s11280-024-01238-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. N. Xiang and X. Ma, “TKDA: An improved method for k-degree anonymity in social graphs,” in IEEE Symp. Comput.Commun. (ISCC), Rhodes, Greece, IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

14. S. H. Lin and R. Xiao, “Towards publishing directed social network data with k-degree anonymization,” Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp., vol. 34, no. 24, 2022, Art. no. e7226. doi: 10.1002/cpe.7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. H. Kaur, N. Hooda, and H. Singh, “k-anonymization of social network data using neural network and SVM: K-neurosvm,” J. Inf. Secur. Appl., vol. 72, 2023, Art. no. 103382. doi: 10.1016/j.jisa.2022.103382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. J. Cheng, A. W. Fu, and J. Liu, “K-isomorphism: Privacy preserving network publication against structural attacks,” in Proc. ACM SIGMOD Int. Conf. Manage. Data (SIGMOD), Indianapolis, IN, USA: ACM, 2010, pp. 459–470. [Google Scholar]

17. H. Zhang, L. Lin, L. Xu, and X. Wang, “Graph partition based privacy-preserving scheme in social networks,” J. Netw. Comput. Appl., vol. 195, 2021, Art. no. 103214. doi: 10.1016/J.JNCA.2021.103214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. X. Ren and D. Jiang, “A personalized

19. L. Zou, L. Chen, and M. T. Özsu, “K-automorphism: A general framework for privacy preserving network publication,” Proc. VLDB Endow., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 946–957, 2009. doi: 10.14778/1687627.168773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. X. Zhang, J. Liu, J. Li, and L. Liu, “Large-scale dynamic social network directed graph K-in&out-degree anonymity algorithm for protecting community structure,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 108371–108383, 2019. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2933151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. W. Ren, K. Ghazinour, and X. Lian, “kt-safety: Graph release via k-anonymity and t-closeness,” IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng., vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 9102–9113, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2022.3221333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. G. S. Kumar, K. Premalatha, G. U. Maheshwari, and P. R. Kanna, “No more privacy concern: A privacy-chain based holomorphic encryption scheme and statistical method for privacy preservation of user’s private and sensitive data,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 234, 2023, Art. no. 121071. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. L. Sweeney, “k-anonymity: A model for protecting privacy,” Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl. Based Syst., vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 557–570, 2002. doi: 10.1142/S0218488502001648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Z. Sun et al., “Dynamic community detection based on the matthew effect,” Physica A, vol. 597, 2022, Art. no. 127315. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2022.127315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. G. Karypis and V. Kumar, “A fast and high quality multilevel scheme for partitioning irregular graphs,” SIAM J. Sci. Comput., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 359–392, 1998. doi: 10.1137/S1064827595287997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. M. Kiabod, M. N. Dehkordi, and B. Barekatain, “TSRAM: A time-saving k-degree anonymization method in social network,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 125, pp. 378–396, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2019.01.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. J. Leskovec, J. M. Kleinberg, and C. Faloutsos, “Graph evolution: Densification and shrinking diameters,” ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data., vol. 1, no. 1, 2007. doi: 10.1145/1217299.1217301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. L. Isella, J. Stehlé, A. Barrat, C. Cattuto, J. Pinton and W. V. Den Broeck, “What’s in a crowd? analysis of face-to-face behavioral networks,” J. Theor. Biol., vol. 271, no. 1, pp. 166–180, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.11.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. A. Paranjape, A. R. Benson, and J. Leskovec, “Motifs in temporal networks,” in Proc. Tenth ACM Int. Conf. Web Search Data Min. (WSDM), Cambridge, UK: ACM, 2017, pp. 601–610. [Google Scholar]

30. P. Panzarasa, T. Opsahl, and K. M. Carley, “Patterns and dynamics of users’ behavior and interaction: Network analysis of an online community,” J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol., vol. 60, no. 5, pp. 911–932, 2009. doi: 10.1002/asi.21015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. L. Danon, A. Díaz-Guilera, J. Duch, and A. Arenas, “Comparing community structure identification,” J. Stat. Mech., vol. 2005, no. 9, 2005, Art. no. P09008. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2005/09/P09008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. L. Hubert and P. Arabie, “Comparing partitions,” J. Classif., vol. 2, pp. 193–218, 1985. doi: 10.1007/BF01908075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. W. M. Rand, “Objective criteria for the evaluation of clustering methods,” J. Am. Stat. Assoc., vol. 66, no. 336, pp. 846–850, 1971. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1971.10482356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. M. Kiabod, M. N. Dehkordi, and B. Barekatain, “A fast graph modification method for social network anonymization,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 180, 2021, Art. no. 115148. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. I. Wagner and D. Eckhoff, “Technical privacy metrics: A systematic survey,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 1–38, 2018. [Google Scholar]

36. Y. Hao, L. Li, L. Chang, and T. Gu, “MLDA: A multi-level k-degree anonymity scheme on directed social network graphs,” Front. Comput. Sci., vol. 18, no. 2, 2024, Art. no. 182814. doi: 10.1007/s11704-023-2759-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools