Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Arrhythmia Intelligent Recognition Method Based on a Multimodal Information and Spatio-Temporal Hybrid Neural Network Model

1 School of Computer Science, Zhongyuan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, 450007, China

2 International Joint Laboratory for AI Interpretability and Reasoning Applications, Zhengzhou, 450007, China

3 School of Foreign Languages, Zhengzhou University of Economics and Business, Zhengzhou, 450099, China

* Corresponding Author: Runchuan Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Trends and Applications of Deep Learning for Biomedical Signal and Image Processing)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 3443-3465. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.059403

Received 07 October 2024; Accepted 26 November 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

Electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis is critical for detecting arrhythmias, but traditional methods struggle with large-scale Electrocardiogram data and rare arrhythmia events in imbalanced datasets. These methods fail to perform multi-perspective learning of temporal signals and Electrocardiogram images, nor can they fully extract the latent information within the data, falling short of the accuracy required by clinicians. Therefore, this paper proposes an innovative hybrid multimodal spatiotemporal neural network to address these challenges. The model employs a multimodal data augmentation framework integrating visual and signal-based features to enhance the classification performance of rare arrhythmias in imbalanced datasets. Additionally, the spatiotemporal fusion module incorporates a spatiotemporal graph convolutional network to jointly model temporal and spatial features, uncovering complex dependencies within the Electrocardiogram data and improving the model’s ability to represent complex patterns. In experiments conducted on the MIT-BIH arrhythmia dataset, the model achieved 99.95% accuracy, 99.80% recall, and a 99.78% F1 score. The model was further validated for generalization using the clinical INCART arrhythmia dataset, and the results demonstrated its effectiveness in terms of both generalization and robustness.Keywords

Electrocardiogram (ECG) serves as a standard method for recording the electrical activity of the heart and is widely used for detecting and diagnosing cardiac abnormalities [1]. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of death worldwide, with approximately 11.3 million people succumbing to sudden cardiac events annually [2]. Traditional ECG diagnosis relies on medical experts manually interpreting the ECG waveforms, a process that is time-consuming and susceptible to inter-operator variability.

In recent years, with the development of artificial intelligence and machine learning, automated arrhythmia detection has emerged as a viable solution, significantly improving diagnostic efficiency and reducing human errors [3]. Existing machine learning methods, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) [4] and Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP) [5], have been applied to ECG analysis [6]. However, they face limitations in handling time-series data, feature fusion, and class imbalance, particularly in detecting rare arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation and premature beats), posing significant challenges for achieving high accuracy and sensitivity [7].

To address these challenges, recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of neural networks in solving complex nonlinear systems, paralleling the complexity involved in ECG signal analysis. For example, Bhat et al. [8] successfully applied a neural network optimized by Levenberg-Marquardt backpropagation to solve highly nonlinear differential equations, demonstrating its capacity to model complex dynamic relationships. Similarly, Chen et al. [9] proposed a Radial Basis Bayesian Regularized Neural Network (RB-BRNN) to handle nonlinear systems, demonstrating its precision in error reduction and capturing complex data patterns. These studies highlight the potential of neural networks in capturing complex dependencies and reducing error rates, which is crucial when dealing with the inherent randomness and imbalance in ECG datasets.

Building on these findings, this paper proposes an intelligent arrhythmia detection method based on a multimodal spatiotemporal hybrid neural network (MSH-GCN). This method enhances the detection of sparse anomalies through a multimodal feature extraction mechanism, integrating ECG images with raw signals using contrastive learning. By incorporating a Spatiotemporal Graph Convolutional Network (ST-GCN), the model captures dependencies between temporal and image features and enhances robustness through data perturbations and residual connections. The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

(1) Designed a multimodal feature extraction mechanism that combines ECG images and raw signal features, utilizing contrastive learning to enhance the model’s ability to detect sparse anomalies.

(2) Introduced a Spatiotemporal Graph Convolutional Network (ST-GCN) to capture spatiotemporal dependencies of different modalities in ECG signals, enhancing model robustness through data perturbations and residual connections.

(3) Trained the model on the MIT-BIH two-lead dataset and tested it on the INCART twelve-lead dataset, with results showing good generalization under cross-lead conditions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related research on ECG analysis and arrhythmia detection. Section 3 describes the datasets and preprocessing techniques. Section 4 presents the proposed model architecture and methodology. Section 5 outlines the experimental results and evaluates their significance. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and proposes future research directions.

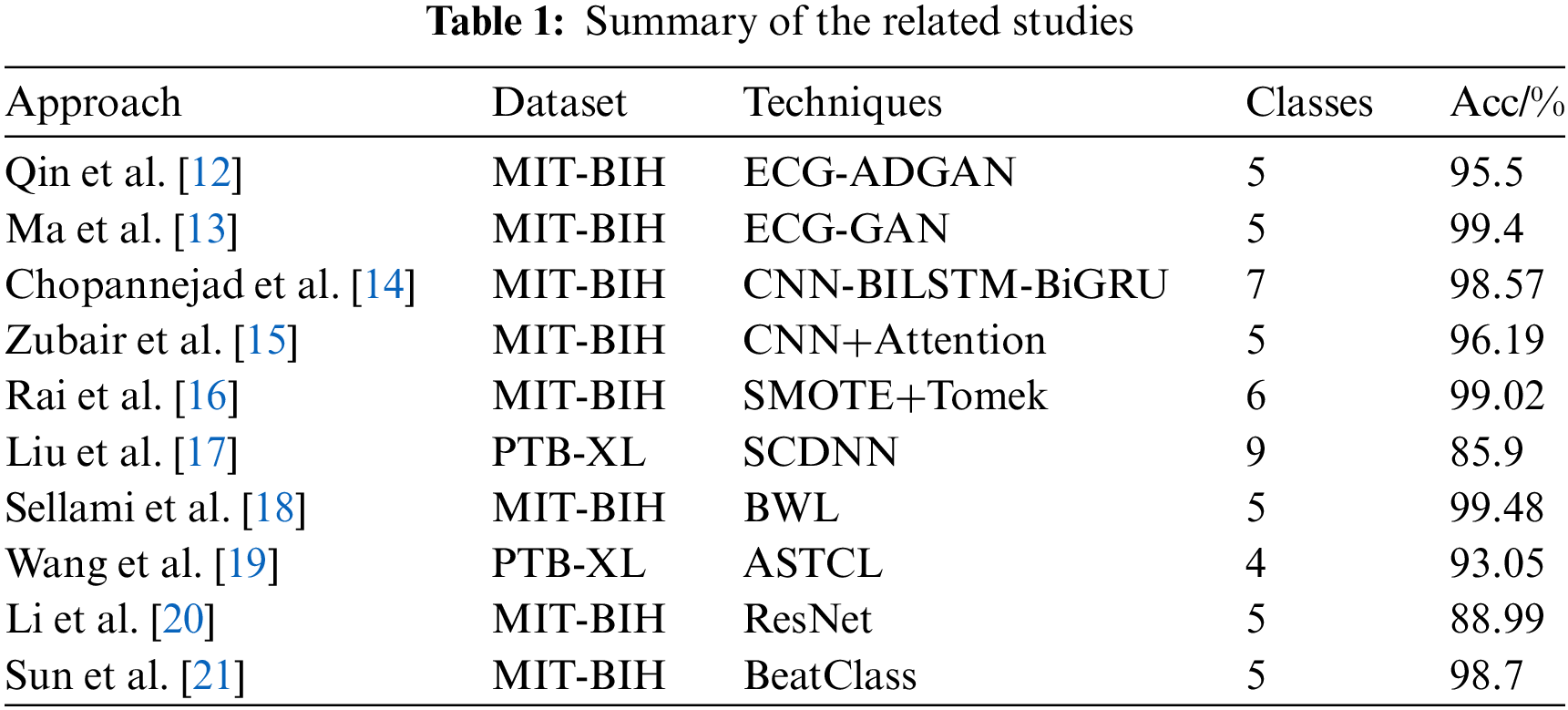

In the study of electrocardiogram (ECG) arrhythmia classification, the issue of data imbalance remains a significant challenge. Data imbalance hampers the model’s capacity to identify minority class arrhythmias, thereby affecting overall diagnostic accuracy [10]. Table 1 provides a summary of the related work reviewed in this section. Current approaches to solving data imbalance can be divided into data-level solutions, feature-level optimization techniques, and model-level improvements.

Data augmentation is commonly used to address data imbalance by increasing the number of minority class samples. Traditional techniques, such as translation and scaling [11], can increase sample size, though they may introduce distortions in key ECG signal characteristics. Qin et al. [12] proposed a Temporal Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) combined with Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM), which improved model stability and accuracy by generating realistic ECG signals, achieving 95.5% accuracy on the MIT-BIH database. Ma et al. [13] used GAN and attention mechanisms to augment scarce data, combined with ResNet and Bi-LSTM models, achieving 99.4% accuracy in a five-class classification task.

Common resampling strategies include oversampling and undersampling methods. Oversampling creates synthetic samples for minority classes to balance the dataset. Chopannejad et al. [14] used Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) combined with multi-head self-attention mechanisms to handle data imbalance, achieving a classification accuracy of 98.57%. However, oversampling may lead to overfitting. Zubair et al. [15] used sample generation and attention modules to convert majority class samples into minority class samples, achieving an accuracy of 96.19% on the MIT-BIH database. Rai et al. [16] proposed a hybrid sampling method combining SMOTE and Tomek Link, improving minority class accuracy by 20%, with a maximum classification accuracy of 99.02%.

2.2 Feature-Level Optimization Techniques

Feature selection and extraction streamline the feature space and improve model performance. Liu et al. [17] proposed the Spectral Cross-Domain Neural Network (SCDNN), combined with soft adaptive threshold spectral enhancement techniques, to capture frequency-domain and time-domain information, mitigating the impact of data imbalance on the model.

Feature balancing techniques address feature imbalance by adjusting the weights of features. Sellami et al. [18] employed a batch-weighted loss function to dynamically adjust the loss weights based on class distribution, improving classification performance and stability.

Deep learning models, including (Domain Neural Network) DNN, (Convolutional Neural Network) CNN, and (Regularized Neural Network) RNN, have demonstrated superiority in handling complex ECG data. By automatically extracting and learning features from the data and combining data augmentation techniques, deep learning models can effectively address the issue of data imbalance.

DNNs, through the connection of multiple layers of neurons, can learn complex features from large amounts of data and perform well in classification tasks. Wang et al. [19] proposed the Adversarial Spatiotemporal Contrastive Learning (ASTCL) framework, which enhances model performance on imbalanced data by constructing patient-level contrastive samples.

CNNs can effectively capture localized patterns in ECG signals. Li et al. [20] proposed an improved ResNet model that combines Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) for denoising and introduces the Focal Loss function to improve classification performance.

RNNs and their variants (such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)) are advantageous in handling time-series data and can capture the temporal dependencies in ECG signals. Sun et al. [21] proposed an ECG classification model combining GAN and RNN, which includes two main modules: the Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) modules Rist and Morst, and the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) module MorphGAN. Rist first classifies heartbeats into five common arrhythmia types, Morst further refines the S and V types, and MorphGAN is used to augment the morphology and contextual knowledge of rare heartbeat categories, improving the data imbalance problem.

Despite the progress made by existing methods in addressing data imbalance, they still face difficulties in managing complex multimodal representations. The MSH-GCN model proposed in this paper addresses the issues of feature monotony and sparse samples through multimodal feature extraction, while the ST-GCN model captures the spatiotemporal dependencies in ECG signals, enhancing the accuracy of multi-class arrhythmia diagnosis.

To ensure accurate import of ECG data and meet model requirements, the databases, including MIT-BIH and European Data Format (EDF) formats, were standardized and uniformly converted into a model-compatible format.

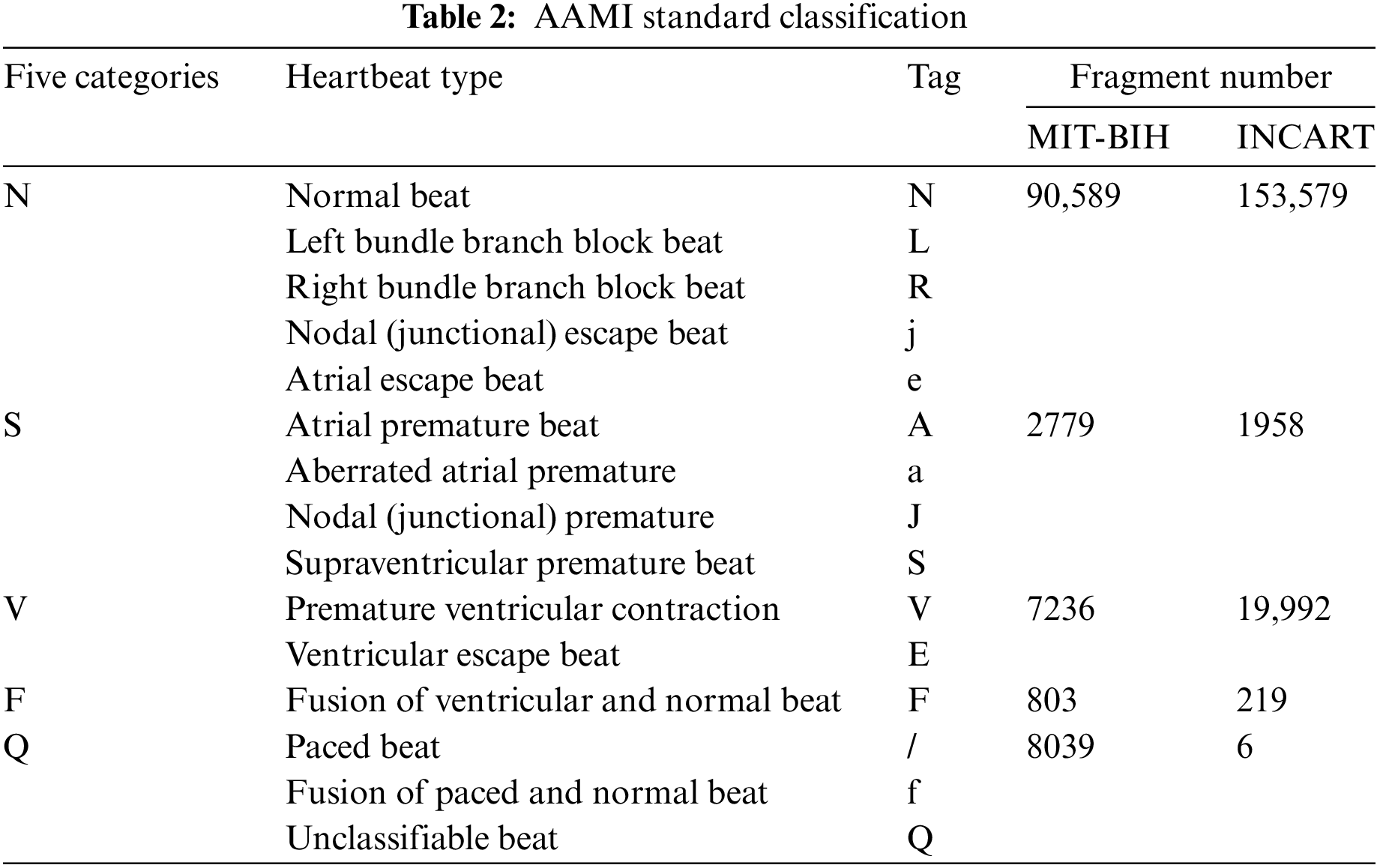

This study utilized the MIT-BIH [22] and INCART arrhythmia databases [23], both available through PhysioNet, which provides open access to extensively validated biomedical data for research. The MIT-BIH database contains 48 two-lead ECG recordings, covering 17 types of arrhythmias from 47 patients, with a total of 100,000 heartbeats. The INCART database includes 12-lead ECG signals from 32 patients, with a sampling frequency of 257 Hz, covering six types of arrhythmias with 170,000 heartbeats. These databases were chosen for their wide application in ECG research and their ability to provide diverse arrhythmia samples, ensuring robust model performance. To standardize the labeling of heartbeats from these databases, this study follows the AAMI EC57:2012 guidelines [24], which are widely adopted in the medical field to ensure consistency in ECG classification. These guidelines categorize heartbeats into five primary classes: normal (N), supraventricular (S), ventricular (V), fusion (F), and unclassified (Q). By adhering to this standard, the results obtained from the proposed model are directly comparable with those from other studies and align with real-world diagnostic practices, enhancing the practical relevance of the research.

Table 2 shows the distribution of heartbeat types in the databases, highlighting significant inter-class imbalance. In the MIT-BIH database, normal beats (N type) far outnumber other arrhythmia types, while in the INCART database, the imbalance is more extreme, with 153,575 N-type samples and only 6 Q-type samples.

Such imbalance can skew the predictions of classification models toward common classes, thereby affecting overall performance [25]. To address this issue, data augmentation strategies are employed to balance the dataset and mitigate the impact of imbalance during training and testing.

To meet the multimodal input requirements of the MSH-GCN model, this study converts raw ECG signals into both image and time-series formats to better capture the complex features inherent in ECG signals.

Specifically, the WFDB tool [26] was employed to extract heartbeat segments and their corresponding rhythm annotations from the databases. For each heartbeat, a segment containing the complete ECG signal was extracted and processed to generate a 64 × 64 pixel image file, with the filename encoding the heartbeat’s class information and corresponding timestamp. At the same time, the original ECG signal data was stored as a separate text file, recording the temporal variations of the ECG signal as one-dimensional time-series data for further analysis.

This dual data storage strategy is designed to integrate one-dimensional time-series information with two-dimensional visual features. The one-dimensional signal data reflects the dynamic changes in the heart’s electrical activity over time, while the transformed two-dimensional images capture morphological features within the time-series data that are challenging to discern directly. By combining these two data formats, the model can analyze ECG features from multiple perspectives, thereby improving the detection accuracy of rare arrhythmia classes.

Table 3 shows the data from the entire MIT-BIH database partitioned into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio [19]. Additionally, all data from the INCART database was utilized for testing to evaluate the model’s generalization ability.

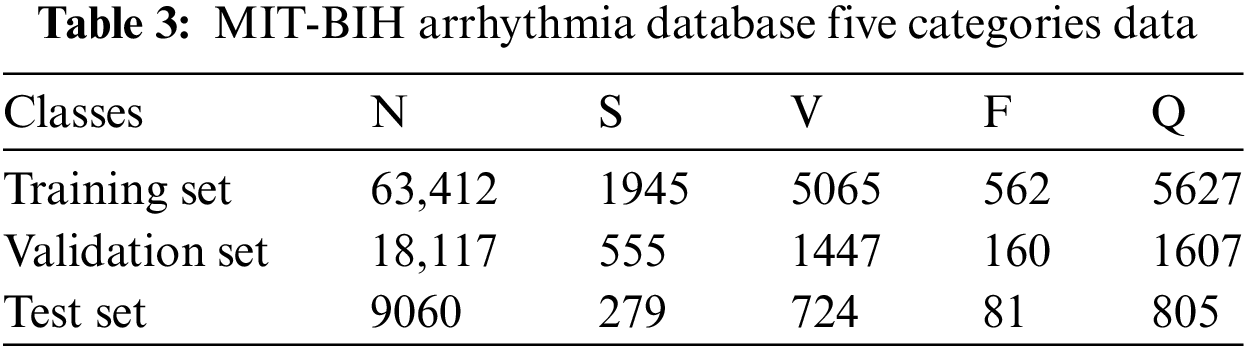

This paper proposes an innovative multimodal data augmentation and spatiotemporal fusion model for optimizing ECG signal processing and analysis. As shown in Fig. 1, the multimodal data augmentation module, first, utilizes improved visual and signal encoders to extract features from ECG images and time-series signals. It then generates enhanced signals through feature projection and fusion, increasing data diversity and improving model generalization. Subsequently, the spatiotemporal fusion module processes time-series data using the Piecewise Aggregate Approximation (PAA) method, extracts edge information from images using multiscale edge detection techniques, constructs spatiotemporal graph-structured data, and optimizes it via a Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (ST-GCN), significantly improving the model’s robustness. Finally, the model employs a weighted cross-entropy loss function and dynamic learning rate scheduling, addressing data imbalance and demonstrating excellent classification performance.

Figure 1: MSH-GCN: Multimodal Infor mation and Spatio-Temporal Hybrid Neural Network

To enhance the processing capability of multimodal ECG data, this study designs a data augmentation module that fuses visual and signal features. By jointly training visual and signal encoders, the complementary nature of both types of data is fully utilized, enhancing the model’s generalization. This module integrates visual feature extraction, signal feature encoding, and feature fusion to improve the capacity to generate enhanced signals.

To effectively extract image features at different scales, this study employed a multi-scale convolutional neural network structure in the visual encoder, introducing adaptive scaling operations to improve feature extraction capability. This design was inspired by prior studies on vision models using self-attention mechanisms, such as Huang et al. [27], which demonstrated improved image feature extraction via multi-head self-attention encoders and residual connections. The feature extraction process is represented by:

where

After feature extraction, multi-head self-attention is applied to the features:

where Q, K, and V represent the query, key, and value matrices, respectively, and A represents the attention weight matrix.

Through the above operations, the visual encoder effectively captures both local and global information from the image and extracts the final feature vector using global average pooling:

where

The signal encoder combines 1D convolutional neural networks (1D-CNN) with Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM) to extract local and global temporal features. First, the 1D-CNN extracts local features:

where

where

where

By introducing adaptive scale variation and the self-attention mechanism, the visual encoder can more accurately capture both local and global information, improving the effectiveness of image feature extraction. Moreover, combining 1D convolution and LSTM in the signal encoder enhances the representation of the time-series.

4.1.3 Feature Projection and Fusion

In the process of multimodal feature fusion, this study draws upon feature enhancement and fusion strategies used in medical image segmentation. Such an approach improves segmentation accuracy through optimized feature extraction and fusion, inspiring the design of visual and signal feature fusion in this study. Two projection layers have been designed: one for visual features and the other for signal features. The mathematical formulation of the projected features is expressed as follows:

where

The final multimodal feature is obtained through feature concatenation:

where

By integrating visual and signal features into a unified feature vector, the model captures complementary information from different modalities, enhancing its performance in detecting rare categories.

This study employs two loss functions:

ISC (Image-Signal Contrastive) loss minimizes differences between visual and signal features to ensure cross-modal consistency:

where

SM (Signal Modeling) loss minimizes the error between the generated and original signals to ensure temporal consistency:

where

The overall loss function is the weighted sum of these two losses:

To further improve generalization, multimodal augmentation generates enhanced signals by projecting visual features and combining them with the original signal via weighted summation:

where

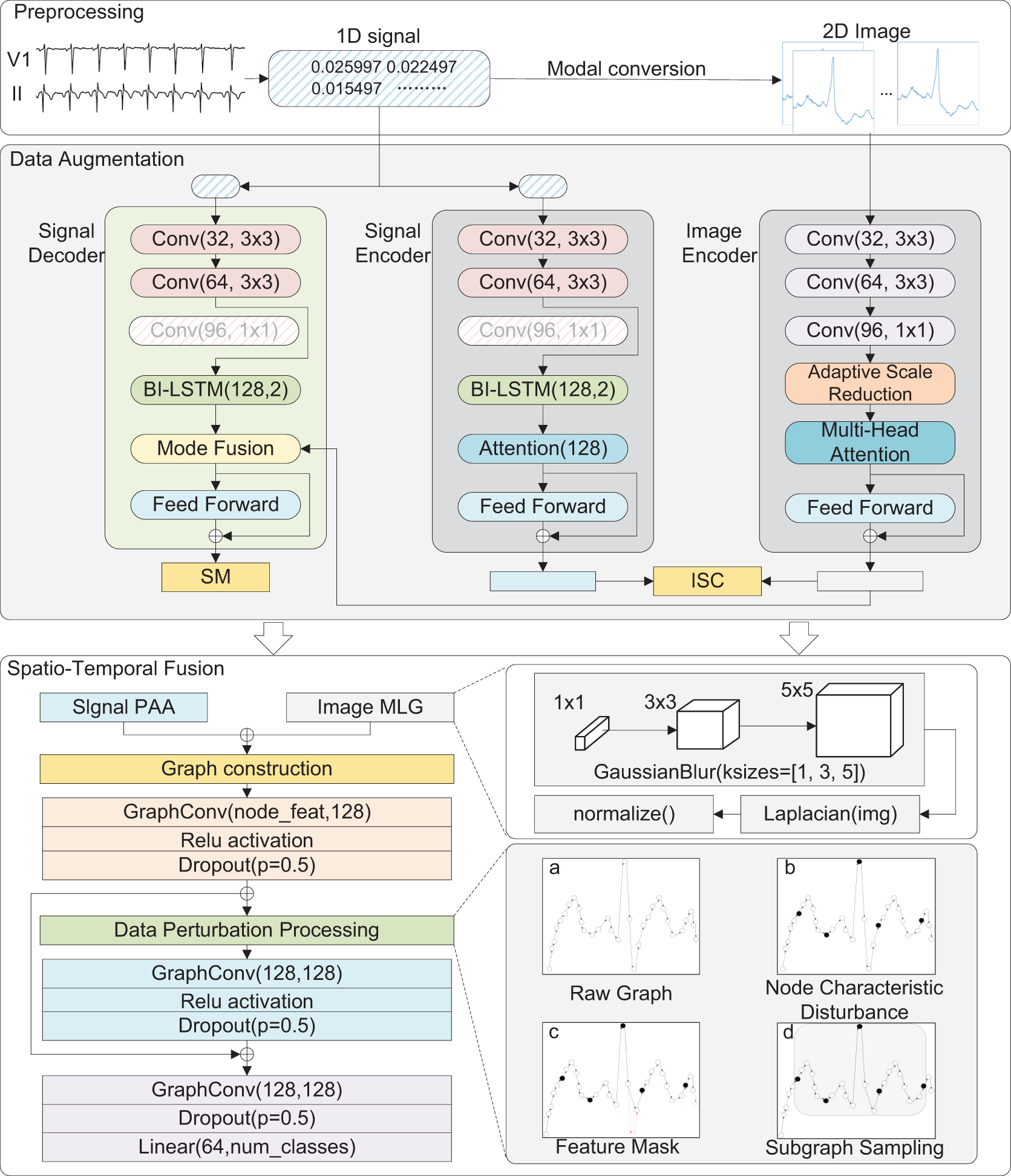

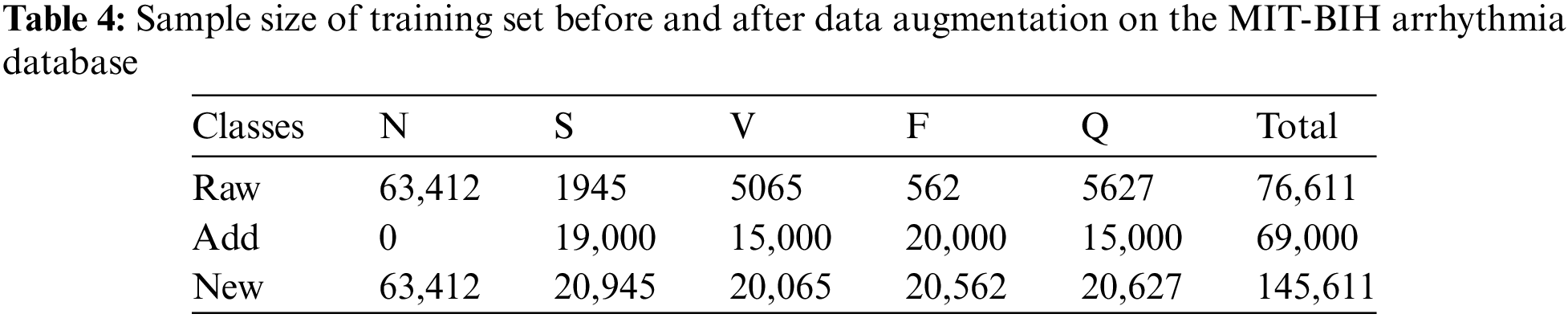

Fig. 2 shows raw electrocardiogram and model generated electrocardiogram. Table 4 shows the sample size of the training set before and after data augmentation. During the data augmentation process, we only balanced the samples in the training set. To ensure data integrity, we retained the original data of the four minority classes (such as S, V, Q, and F) while performing data augmentation on them [28]. This strategy not only increases the number of minority class samples but also avoids interference with the sample distribution in the validation and test sets, ensuring the representativeness and objectivity of the validation and test sets during the evaluation process.

Figure 2: Raw electrocardiogram and model generated electrocardiogram

To handle the fused multimodal data, this study presents an improved Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (ST-GCN). By extending the original ST-GCN model [29], the following optimizations are introduced in spatiotemporal fusion: (1) effective integration of time-series and image features; (2) application of multiple data perturbation strategies to enhance model robustness; and (3) implementation of hierarchical residual connections to ensure seamless fusion and transmission of multi-scale features.

4.2.1 Data Representation and Graph Structure Construction

In constructing the spatiotemporal graph data structure, this study extends and adapts the success of graph-based methods in medical data processing. Such approaches have proven effective in enhancing data analysis accuracy and improving personalized recommendations by integrating diverse medical data (e.g., patient history, medication usage, and health trends) into graph representations. These insights guided the design of the spatiotemporal fusion model in our ECG signal analysis, particularly for integrating and modeling spatiotemporal data. Additionally, this study employs a multi-feature fusion approach to effectively integrate diverse data types. This method has been tailored to optimize the fusion of ECG signal and image features, significantly enhancing the accuracy of spatiotemporal data modeling.

This paper proposes a novel graph representation method that combines time-series signals and image features, suitable for spatiotemporal data processing in Graph Neural Networks (GCNs). First, the Piecewise Aggregate Approximation (PAA) method reduces the dimensionality of time-series data while extracting key features. Then, multi-scale edge detection is applied to extract edge information from images. These two feature types are integrated into the graph structure, where the time-series data serve as the initial node attributes, and the image edge information functions as the connection features between nodes. This process generates graph data suitable for GCN processing.

The PAA method [30] segments the time-series data and averages it to produce reduced-dimensional features:

where

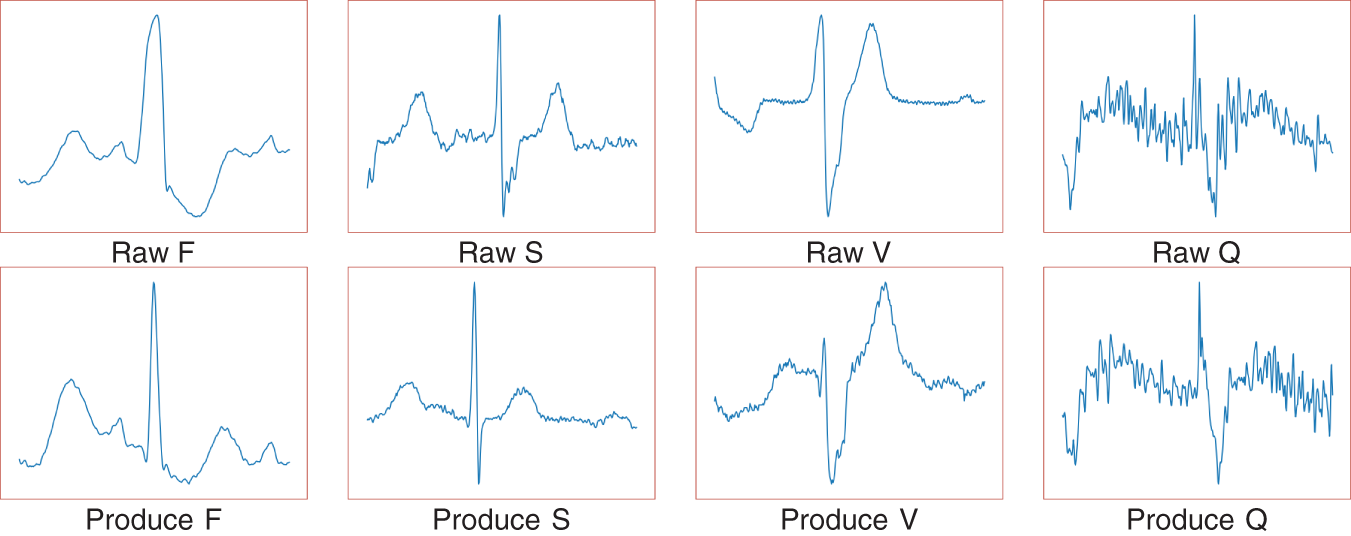

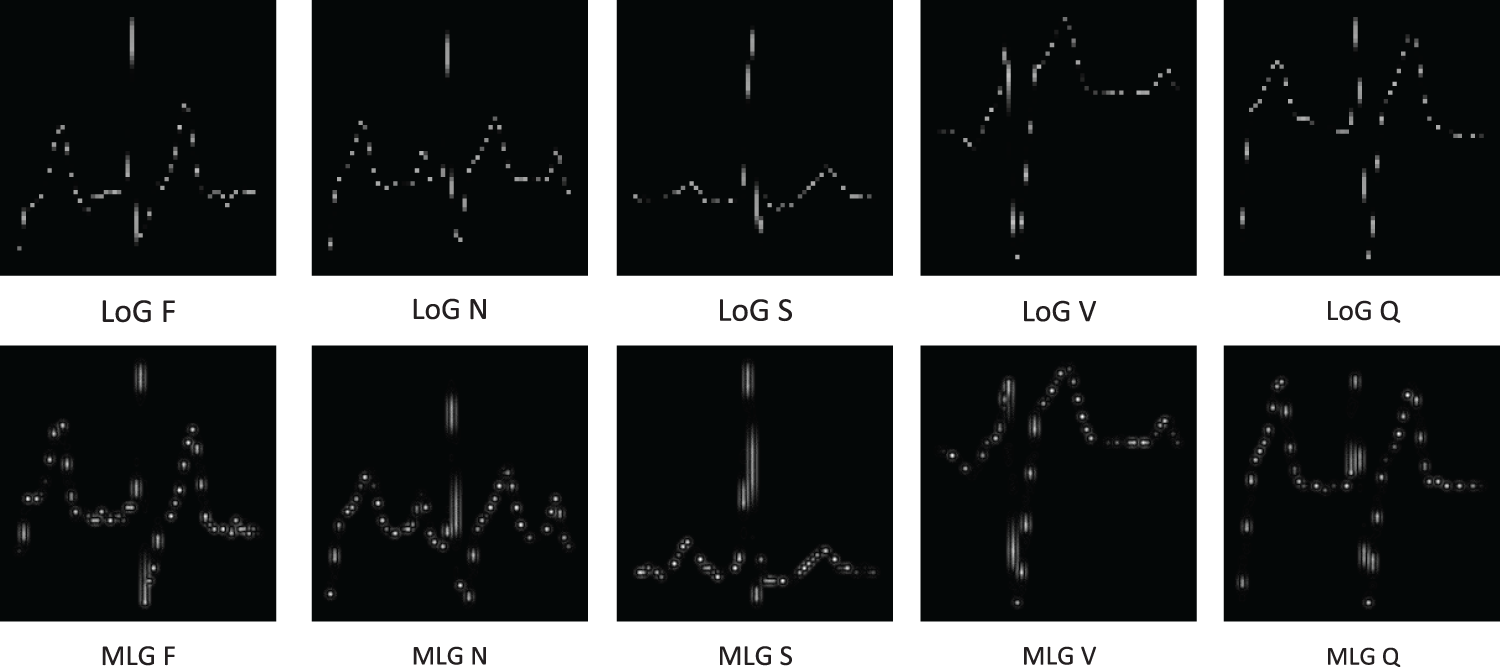

For image data processing, this study adopts the Multi-scale Laplacian-Gaussian (MLG) edge detection method to achieve more precise and multi-level feature extraction. As shown in Fig. 3, compared with the Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) method [31], MLG edge detection captures both fine-grained and coarse-grained edge information, improving overall model performance. Gaussian blurring is applied at different scales to ensure fine edges are preserved at smaller scales while noise is smoothed at larger scales, emphasizing global edge structure. The mathematical expression is:

Figure 3: (Multi-scale Laplacian-Gaussian, MLG) vs. Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) edge detection method comparison chart

where

where

After extracting time-series and image features, the extracted features are integrated into the graph structure. The PAA-generated time-series features serve as node attributes, and the image edge information functions as supplementary connection features. Neighborhood relationships define graph edges, and Z-score normalization is applied to the node feature values:

where

4.2.2 Data Perturbation Processing

To enhance the model’s robustness and generalization, this study introduces several data perturbation strategies, including node feature perturbation, feature masking, and subgraph sampling. These strategies help the model handle noise and missing information, improving performance in complex environments.

Node feature perturbation: Gaussian noise is added to the node features to simulate random variations in real-world data. The formula is as follows:

where

Feature masking: Randomly selects and masks some node features by setting them to zero:

where

Subgraph sampling: randomly selecting a portion of nodes in the graph to form a subgraph for training enhances the structural diversity of the graph, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability.

where V is the original graph’s node set, V′ is the node set of the sampled subgraph,

This paper adopts ST-GCN (spatial-temporal Graph Convolutional Network) as the base model for processing the constructed spatiotemporal graph data structure. ST-GCN can efficiently extract the features of graph nodes through convolutional operations while capturing the complex relationships between nodes, making it an ideal choice for handling non-Euclidean spatial data. Unlike traditional feed-forward neural networks (FNNs), ST-GCN can operate directly on graph data structures and handle the dependencies between nodes and their neighbors through its flexible convolution kernel design. This characteristic provides a solid theoretical foundation for the spatiotemporal feature fusion and graph structure optimization in this study.

Each spatiotemporal convolution layer first processes temporal information with 1D convolution, followed by spatial information using graph convolution:

where

Global pooling and classification layer: at the output of the spatiotemporal convolutional layers, global average pooling is used to aggregate node features into graph-level features, which are finally fed into a fully connected layer for classification. The formula is as follows:

where

4.2.4 Loss Function and Optimization

To address class imbalance in the dataset, this paper employs a weighted cross-entropy loss function to improve the recognition accuracy of minority classes:

where

During optimization, the model uses the Adam [32] optimizer and dynamically adjusts the learning rate with a scheduler to ensure fast convergence and avoid overfitting.

The proposed multimodal data augmentation and spatiotemporal fusion model improves the accuracy and robustness of ECG signal analysis and has significant social benefits. Intelligent ECG monitoring systems can optimize healthcare resources by supporting remote monitoring of heart disease patients. This approach addresses key challenges such as remote information transmission, sharing diagnostic opinions, and timely communication between healthcare providers and patients. Moreover, it provides timely, accurate, and reliable medical data to healthcare administrators, facilitating the development of effective prevention and treatment strategies. By integrating advanced artificial intelligence technologies into healthcare services, this study contributes to improving the quality and accessibility of healthcare at the grassroots level.

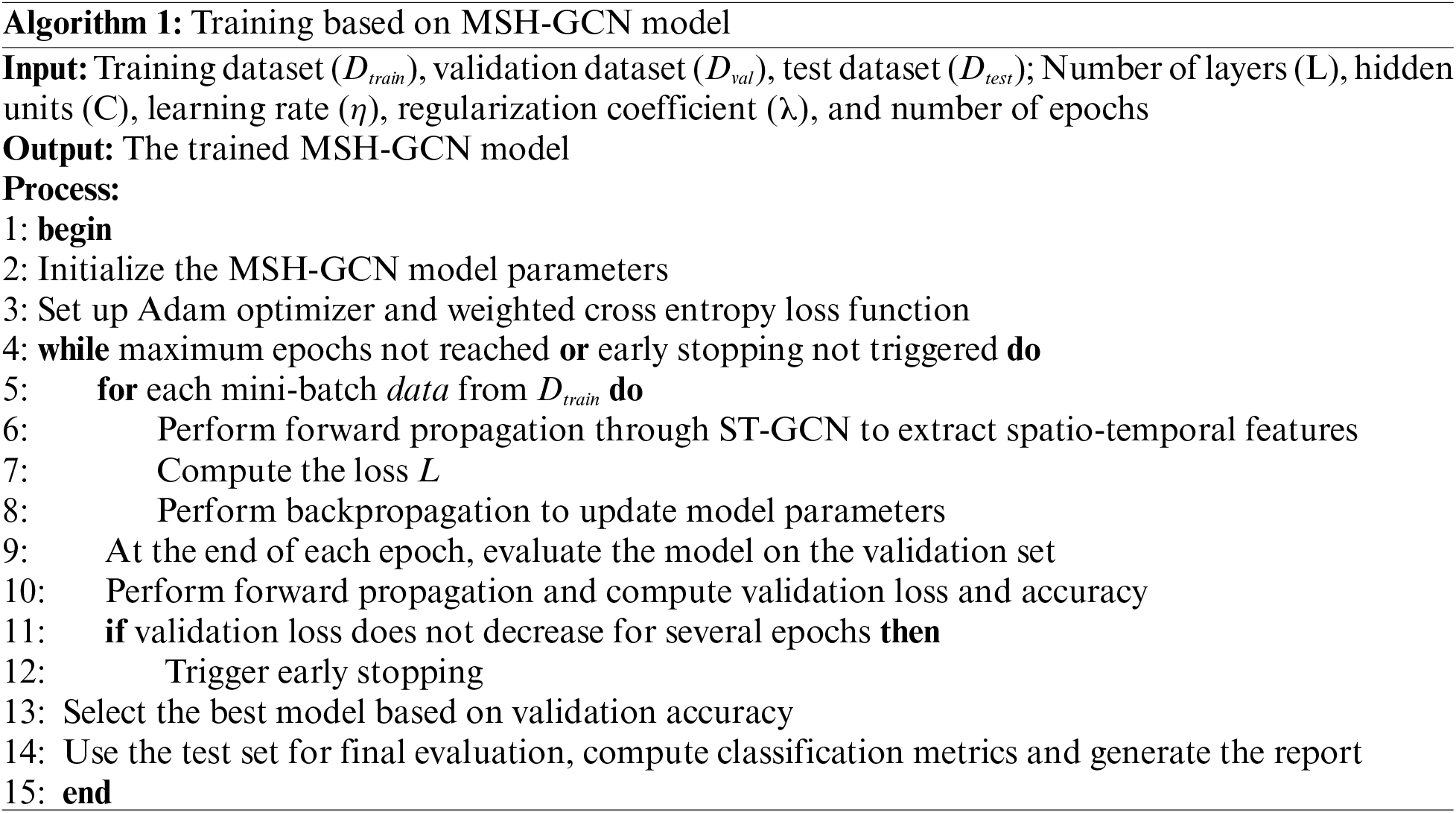

This section presents a detailed performance evaluation of the MSH-GCN model under various experimental conditions. The effectiveness and superiority of the model were validated across multiple experimental setups, including basic model evaluation, parameter optimization, ablation experiments, comparative experiments, and generalization experiments. Through a series of experiments, the processing capability of the MSH-GCN model for time-series and graph-structured data, as well as its application potential in ECG classification tasks, was comprehensively demonstrated.

The experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 workstation equipped with 16 GB of RAM, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 graphics card (4 GB VRAM), and CUDA 11.3 for GPU acceleration. PyTorch 1.10 and the PyG 2.0.4.5 library were used for deep learning and graph neural network operations. The MSH-GCN model was trained for 100 epochs with a batch size of 4048, a learning rate of 0.001, and the Adam optimizer (Algorithm 1).

The classification performance of the MSH-GCN model was evaluated using a confusion matrix, which summarizes the model’s predictions across different categories. True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN) were derived from the confusion matrix [33]. These metrics were used to derive key performance indicators, including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 score:

Accuracy: The proportion of correct predictions.

Precision: The proportion of true positives among predicted positives.

Recall: The proportion of actual positives correctly predicted.

F1 score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall.

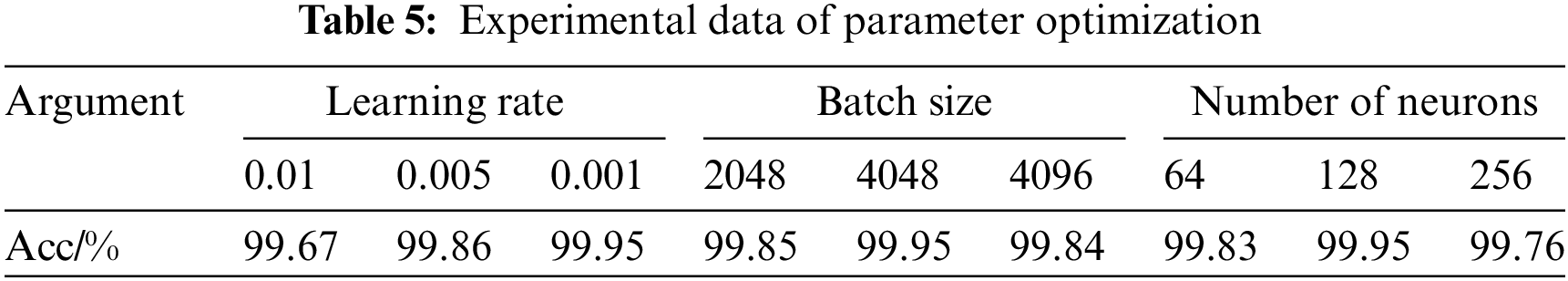

To optimize the performance of the MSH-GCN model, experiments were conducted on three key hyperparameters: learning rate, batch size, and the number of hidden neurons. Table 5 summarizes the experimental results.

The values 0.01, 0.005, and 0.001 were tested. Under the conditions of a batch size of 4048 and 128 hidden neurons, the model achieved the highest accuracy (99.95%) with a learning rate of 0.001. This result suggests that a smaller learning rate facilitates smooth convergence and improves classification performance.

With a learning rate of 0.001 and 128 hidden neurons, the model achieved the best performance (99.95%) at a batch size of 4048. Smaller batch sizes increase the frequency of parameter updates but may disproportionately favor majority classes, while larger batch sizes can reduce the model’s capacity to learn from minority classes.

5.3.3 Number of Hidden Neurons

With a learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 4048, the configuration of 128 neurons yielded the highest accuracy (99.95%). Changes in the number of neurons influence the model’s performance. A configuration with 64 neurons limited the model’s learning capacity, resulting in a slightly lower accuracy of 99.83%. Conversely, using 256 neurons enhanced the representation capacity, but the accuracy dropped to 99.76%, which is likely attributed to reduced generalization caused by overfitting. The 128-neuron configuration provided an optimal balance between performance and complexity, ensuring high accuracy while avoiding overfitting.

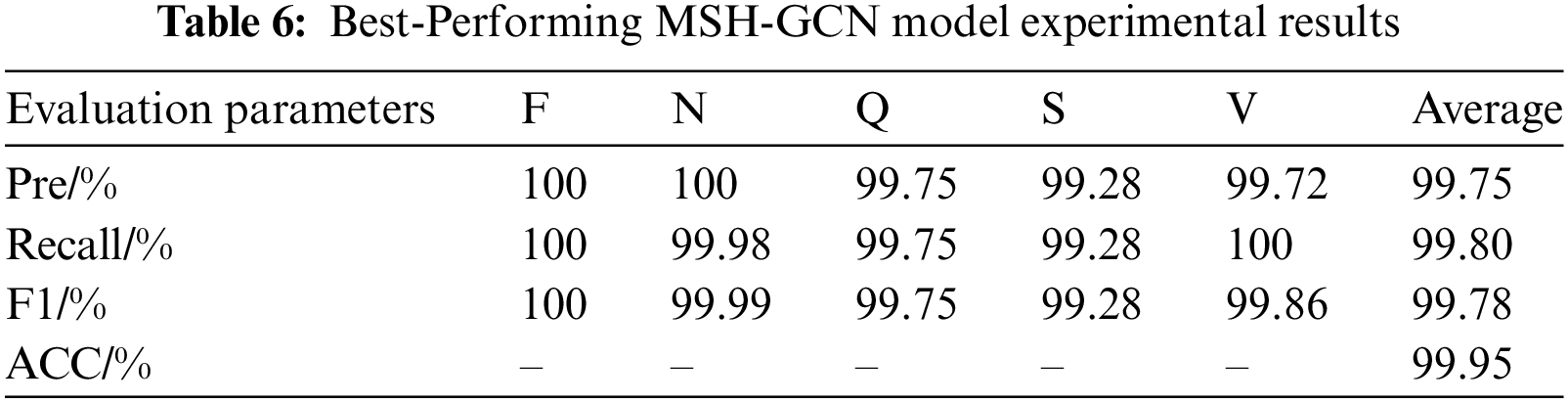

Based on the above optimization experiments, the optimal hyperparameter configuration of the TSF-GCN model was identified: a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 4048, and 128 hidden neurons. The experimental results of the best-performing model are shown in Table 6.

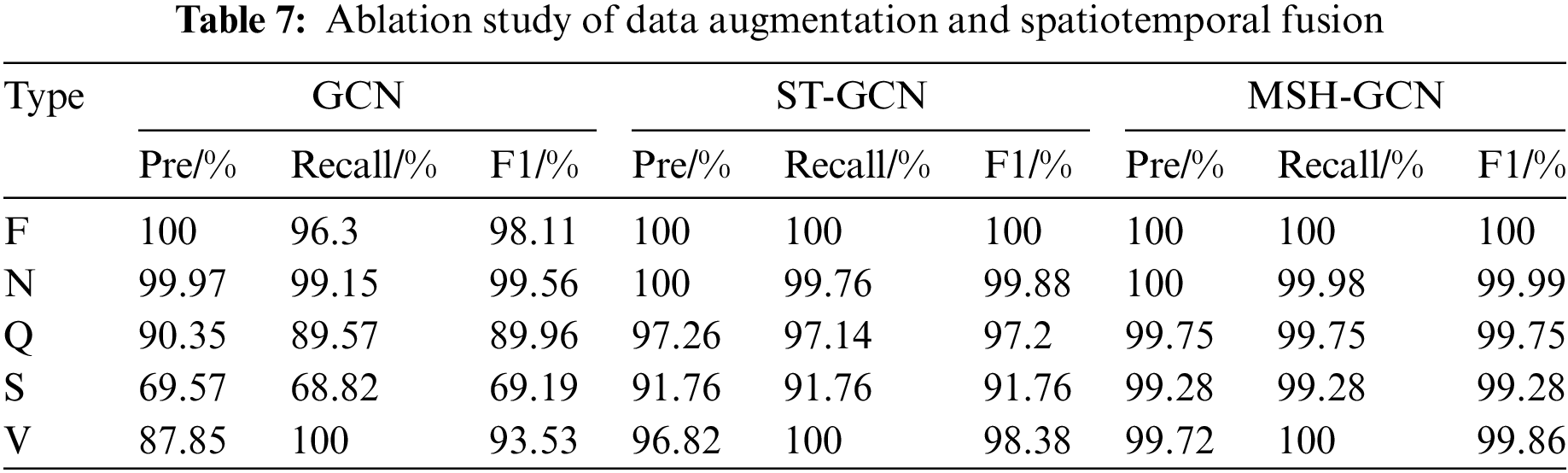

The performance improvement of the data augmentation and spatiotemporal fusion modules was validated through ablation experiments. Three experimental configurations were implemented: (1) a GCN baseline model; (2) a model with the spatiotemporal fusion module; and (3) the complete model, incorporating both data augmentation and spatiotemporal fusion modules. Table 7 summarizes the experimental results.

GCN baseline model: The model exhibited strong performance for simple heartbeat types (e.g., F and N classes), achieving F1 scores of 98.11% for class F and 99.56% for class N. However, its performance declined on more complex heartbeat types (e.g., Q, S, and V classes), with the F1 score for class S reaching only 69.19%.

Adding the spatiotemporal fusion module: Incorporating the spatiotemporal fusion module significantly improved the classification ability for complex heartbeats. The F1 score for class Q increased from 89.96% to 97.20%, for class S from 69.19% to 91.76%, and for class V from 93.53% to 98.38%. These results demonstrate that the spatiotemporal fusion module enhances the model’s ability to capture and leverage complex spatiotemporal features.

Complete model: With both the data augmentation and spatiotemporal fusion modules, the accuracy, recall, and F1 scores for all heartbeat types nearly reached 100%. Notably, the F1 scores for Q, S, and V classes were 99.75%, 99.28%, and 99.86%, respectively. These findings indicate that the data augmentation module effectively mitigates data imbalance, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization ability.

Overall, the results confirm the synergistic effects of the data augmentation and spatiotemporal fusion modules, both of which are essential for improving the classification performance of complex heartbeat signals.

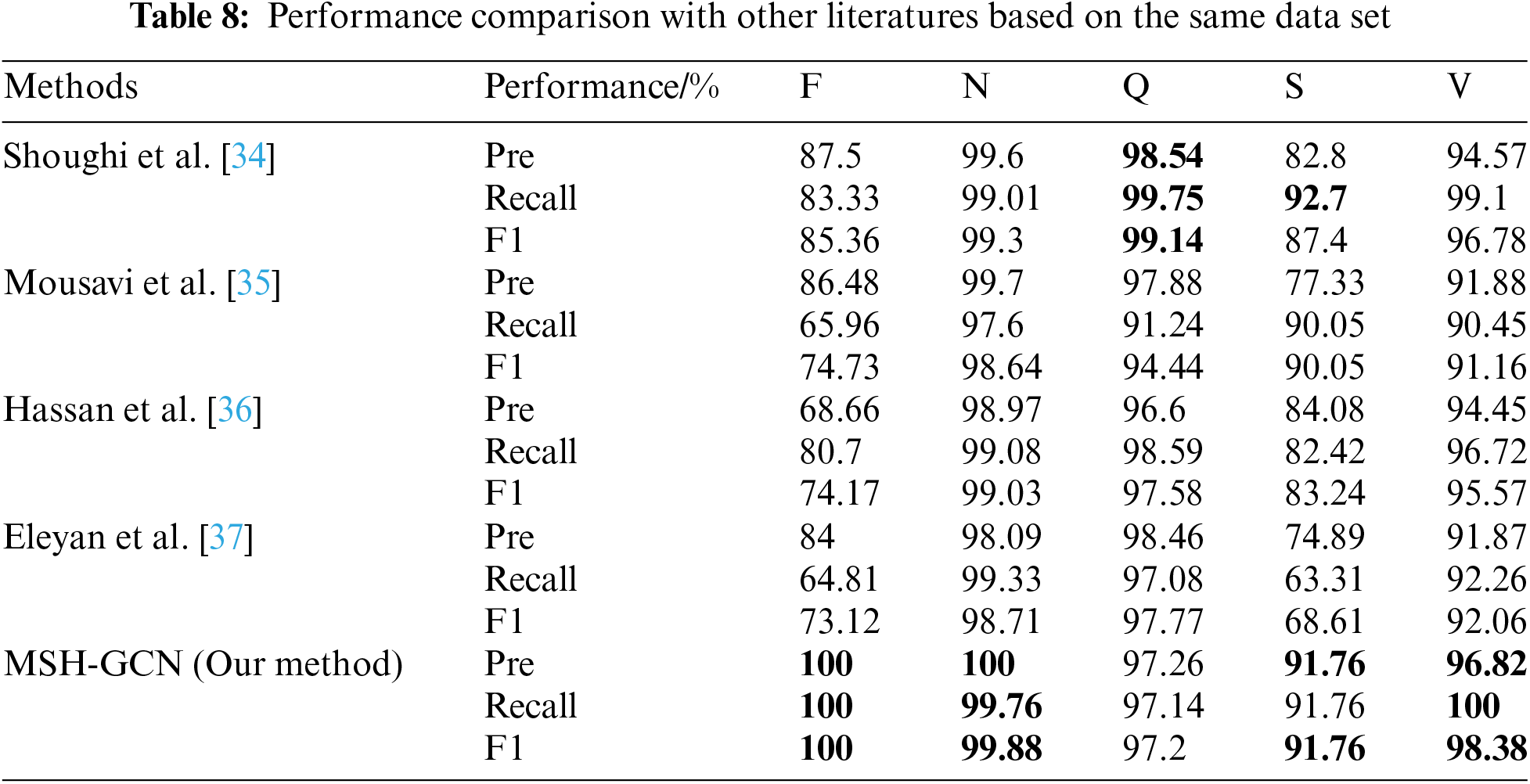

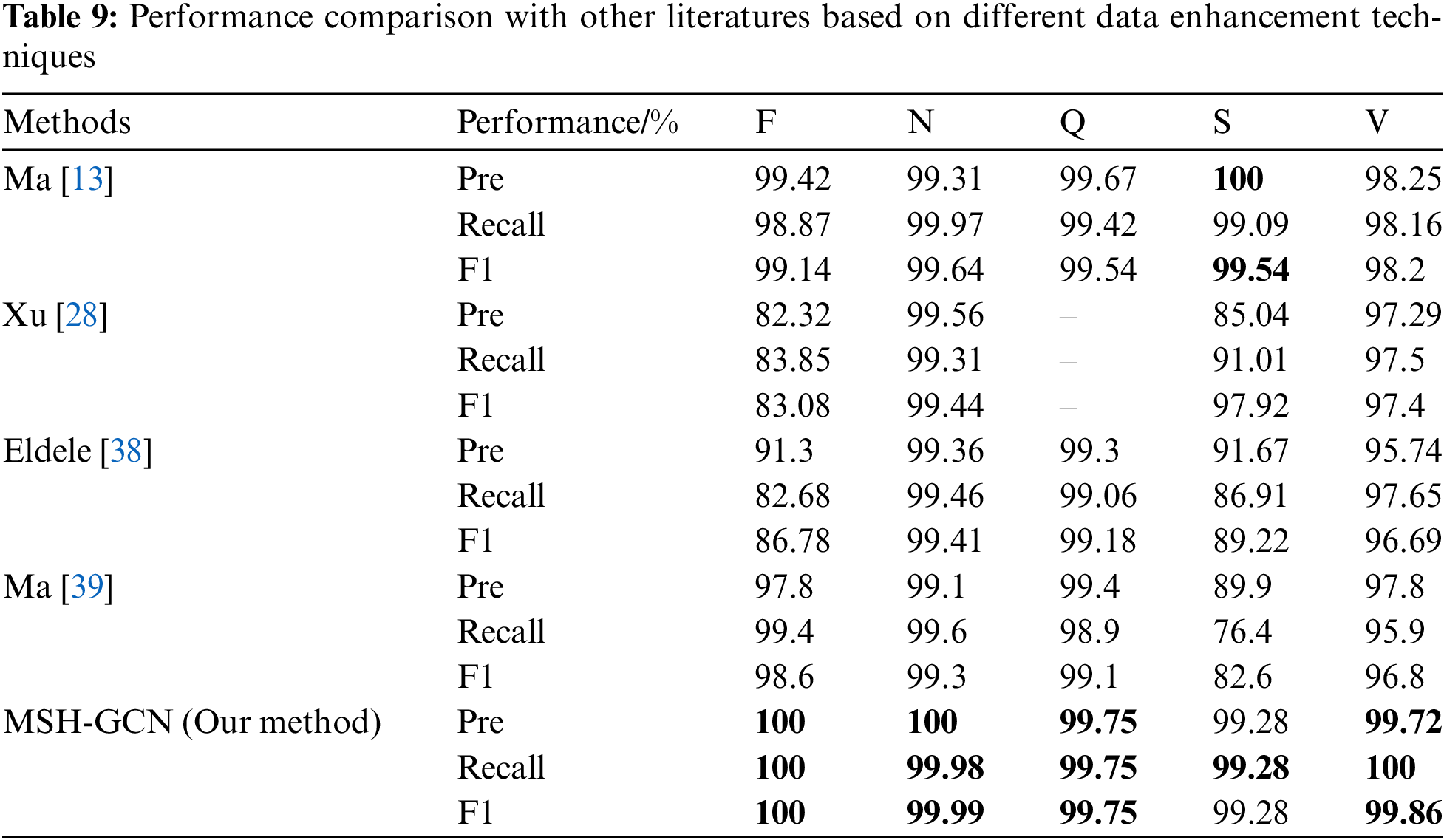

Two sets of comparative experiments were conducted. The first set evaluates the heartbeat classification performance of different deep learning models on the same dataset, while the second set examines the effects of various data augmentation techniques. The results are presented in Tables 8 and 9.

5.5.1 Experiment One: Comparison Based on the Same Dataset

Table 8 provides a performance comparison between the proposed model in this study and other models from the literature on the same dataset. The GCN spatiotemporal fusion model proposed in this study achieved the highest accuracy, recall, and F1 scores across all heartbeat classification tasks, comprehensively outperforming other methods.

Shoughi et al. [34] used CNN and BLSTM combined with DWT and SMOTE for data processing, demonstrating strong performance in detecting complex heartbeats. However, their model achieved an F1 score of only 85.36% for class F heartbeats, compared to the 100% achieved by our model. Similarly, Mousavi et al. [35] employed CNN and RNN for ECG signal classification, delivering outstanding performance on N-class heartbeats (F1 score of 98.64%) but showing poor results for rare types such as class F, with a recall rate of 65.96%. Hassan et al. [36] combined CNN and Bi-LSTM, achieving good results for N and V-class heartbeats. However, their model exhibited a low recall rate for class F (80.70%). Eleyan et al. [37] used FFT and CNN, showing strong performance on N and V-class heartbeats, but with weaker results for class F (F1 score of 73.12%) and class S (F1 score of 68.61%).

The proposed model exhibits substantial advantages in classifying complex signals and rare categories through the spatiotemporal fusion strategy, achieving superior performance compared to existing methods.

5.5.2 Experiment Two: Comparison Based on Different Data Augmentation Techniques

Table 9 presents the impact of various data augmentation techniques on heartbeat classification performance. The multimodal data augmentation method proposed in this study achieved nearly or fully 100% F1 scores across all heartbeat types, surpassing other existing approaches.

Ma et al. [13] combined GAN, ResNet, and BiLSTM, reporting an overall accuracy of 99.4%; however, the F1 score for S-class heartbeats was 90.05%, which is considered suboptimal. Xu et al. [28] proposed the Multi-Modal Data Augmentation Network (MM-DANet) for arrhythmia classification, achieving an F1 score of 98.20% for class V, but its performance for class S (F1 score 89.22%) fell short of the 99.28% achieved by the model in this study. El-Ghaisha et al. [38] introduced ECGTransForm, which utilized multi-scale convolution and a bidirectional Transformer, but the F1 score for class S (89.22%) remained inferior to the results achieved by the current model. Similarly, Ma et al. [39] addressed data imbalance using GAN and CNN, but the F1 score for S-class heartbeats was only 82.6%, demonstrating a significant gap compared to the performance of our model.

The GCN spatiotemporal fusion model and multimodal data augmentation technique proposed in this study exhibited superior performance in handling complex spatiotemporal features and addressing data imbalance issues. The model achieved the highest accuracy and F1 scores across all heartbeat types, validating its robustness and potential for broad application.

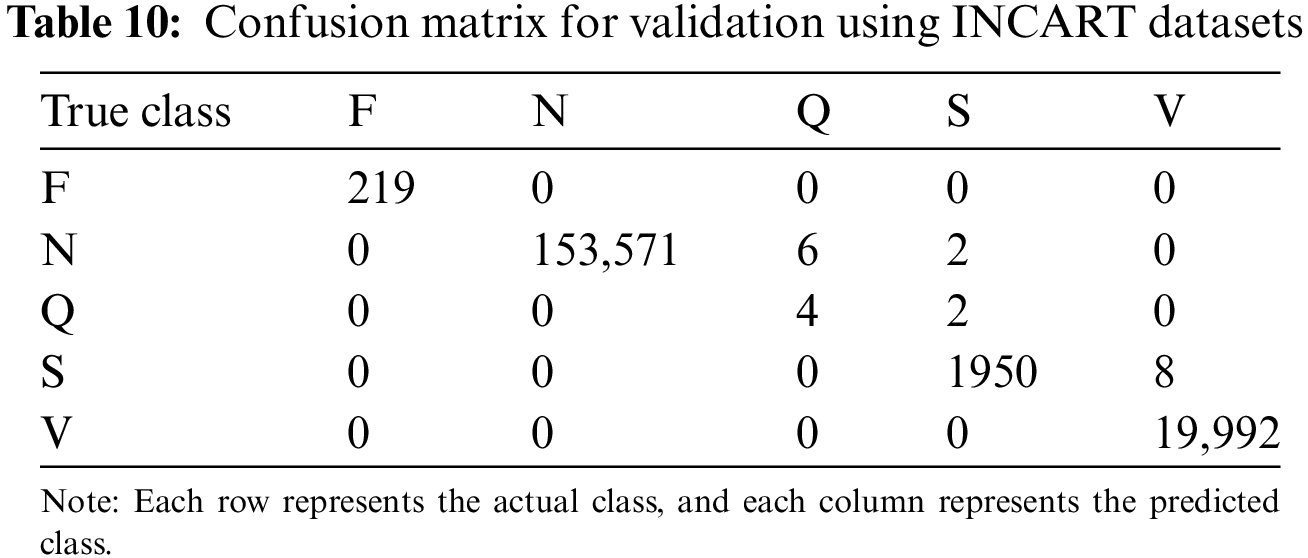

This experiment evaluated the model’s generalization ability across different datasets by training the model on the MIT-BIH dataset and testing it on the INCART dataset to assess its performance under varying data sources and lead counts.

Table 10 provides the confusion matrix of the test results: F-class heartbeats: All 219 samples were correctly classified. N-class heartbeats: Of 153,571 samples, only 8 were misclassified (6 as Q-class and 2 as S-class), indicating the model’s high accuracy in detecting normal heartbeats. Q-class heartbeats: Four samples were correctly classified, with two misclassified as S-class; however, Q-class heartbeats have low clinical significance, with minimal impact on overall performance. S-class heartbeats: Of 1950 samples, only 8 were misclassified as V-class, indicating stable classification performance. V-class heartbeats: All 19,992 samples were correctly classified, demonstrating the model’s strong robustness in detecting abnormal heartbeats.

The model exhibited strong performance across most heartbeat types (F, N, S, V), demonstrating robust cross-dataset generalization. Although minor errors were observed in Q-class heartbeats, their clinical impact is minimal. The data augmentation and spatiotemporal fusion modules substantially enhanced the model’s performance in handling rare heartbeat types and adapting to varying data sources.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) signal classification plays a critical role in medical diagnosis, especially in identifying abnormal heartbeats. However, ECG signals are inherently complex, diverse, and imbalanced, leading to poor performance of existing methods when handling complex signals and minority heartbeat classes. Traditional Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) face limitations in capturing both temporal and spatial features, hindering effective identification of complex heartbeat types.

To address these challenges, this study presents a multimodal data augmentation and spatiotemporal fusion model (MSH-GCN), which consists of two core modules:

(1) A multimodal data augmentation module: This module enhances feature extraction diversity by combining visual and signal encoders and employs feature projection and fusion to generate augmented signals, effectively addressing the data imbalance problem.

(2) A spatiotemporal fusion module: This module incorporates an improved Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (ST-GCN) to process spatiotemporal data, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to recognize complex spatiotemporal features in ECG signals.

5.7.3 Theoretical Contributions

Multimodal fusion enhances feature representation: By projecting visual and signal features into the same space, the model can extract and fuse data from different modalities in a more comprehensive manner, thereby improving classification accuracy. Compared to traditional unimodal approaches, multimodal fusion improves the model’s capacity to analyze complex signals, particularly under imbalanced data conditions.

Optimization of spatiotemporal feature processing: The spatiotemporal fusion module effectively integrates temporal and spatial information through ST-GCN, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize complex heartbeat types. Experimental results demonstrate that MSH-GCN offers substantial advantages over traditional GCN models in capturing intricate spatiotemporal relationships, particularly in detecting abnormal and rare heartbeat signals.

Addressing data imbalance and improving generalization: The data augmentation module generates additional minority class samples and addresses data imbalance through a rich set of augmentation strategies. Generalization experiments demonstrate the model’s robustness across different datasets, especially in cross-dataset classification of minority heartbeat types, validating its strong generalization ability.

Through these innovations, the MSH-GCN model proposed in this study significantly improves the accuracy and robustness of ECG classification tasks, exhibiting strong potential in addressing complex signals and data imbalance issues.

This paper presents a novel multimodal spatiotemporal hybrid neural network (MSH-GCN) for ECG arrhythmia classification, which addresses challenges such as data imbalance and the complexity of multimodal feature extraction. The model effectively combines the data augmentation module with spatiotemporal fusion, substantially enhancing the detection performance of minority class arrhythmias. Experimental results show that MSH-GCN achieves superior performance across various metrics, including accuracy, recall, and F1 score, outperforming existing sparse ECG classification methods.

Like many deep learning models, the functionality of MSH-GCN resembles a ”black box,” where the internal decision-making process is not easily interpretable by human experts. In high-risk fields such as medical diagnostics, this lack of interpretability can limit trust and acceptance. Specifically, the ability to attribute certain features or patterns in ECG signals to the model’s predictions plays a crucial role in its practical application in clinical settings.

To overcome these limitations, future research will focus on enhancing the model’s interpretability through the integration of techniques such as attention mechanisms, saliency maps, or Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP). These methods aim to improve the model’s transparency, enabling clinicians to better understand and trust its predictions.

Future work will also investigate the incorporation of additional physiological parameters, such as blood pressure and blood oxygen levels, into the MSH-GCN model to further enhance its diagnostic accuracy.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to all researchers who have contributed to advancements in the field of ECG signal analysis. Special thanks are extended to the reviewers and editors of this journal for their constructive feedback and insightful suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by The Henan Province Science and Technology Research Project (242102211046), the Key Scientific Research Project of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province (25A520039), the Natural Science Foundation project of Zhongyuan Institute of Technology (K2025YB011), the Zhongyuan University of Technology Graduate Education and Teaching Reform Research Project (JG202424).

Author Contributions: Xinchao Han oversaw the overall progress of the project. Aojun Zhang and Runchuan Li designed the research methodology, developed the model, and analyzed the experimental results. Shengya Shen and Di Zhang conducted literature reviews, explored relevant issues, and refined the language. Bo Jin, Longfei Mao, Linqi Yang and Shuqin Zhang collected and preprocessed the data. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study (MIT-BIH and INCART) are publicly available through PhysioNet, as cited in the manuscript. Researchers can also obtain the data by contacting the corresponding author via email.

Ethics Approval: This study does not involve human participants or animals, as it is based entirely on publicly available datasets. Therefore, no ethical approval was required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Y. -R. Wang et al., “Screening and diagnosis of cardiovascular disease using artificial intelligence-enabled cardiac magnetic resonance imaging,” Nat. Med., vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1–10, 2024. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02971-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. C. W. Tsao et al., “Heart disease and stroke statistics–2023 update: A report from the american heart association,” Circulation, vol. 147, no. 8, pp. e93–e621, 2023. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. A. Y. Hannun et al., “Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network,” Nat. Med., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 65–69, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0268-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. G. G. Geweid and J. D. Chen, “Automatic classification of atrial fibrillation from short single-lead ecg recordings using a hybrid approach of dual support vector machine,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 198, no. 1, 2022, Art. no. 116848. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. C. Chen, B. da Silva, C. Yang, C. Ma, J. Li and C. Liu, “AutoMLP: A framework for the acceleration of multi-layer perceptron models on FPGAs for real-time atrial fibrillation disease detection,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst., vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1371–1386, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TBCAS.2023.3299084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. R. Li et al., “An intelligent heartbeat classification system based on attributable features with AdaBoost + Random Forest algorithm,” J. Healthc. Eng., vol. 2021, no. 1, 2021, Art. no. 9913127. doi: 10.1155/2021/9913127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. J. Lai et al., “Practical intelligent diagnostic algorithm for wearable 12-lead ECG via self-supervised learning on large-scale dataset,” Nat. Commun., vol. 14, no. 1, 2023, Art. no. 3741. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39472-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. S. A. Bhat et al., “A neural network computational procedure for the novel designed singular fifth order nonlinear system of multi-pantograph differential equations,” Knowl.-Based Syst., vol. 301, no. 2, 2024, Art. no. 112314. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Q. Chen, Z. Sabir, M. Umar, and H. Mehmet Baskonus, “A bayesian regularization radial basis neural network novel procedure for the fractional economic and environmental system,” Int. J. Comput. Math., vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 1–12, 2024. doi: 10.1080/00207160.2024.2409794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. H. M. Rai, J. Yoo, and S. Dashkevych, “GAN-SkipNet: A solution for data imbalance in cardiac arrhythmia detection using electrocardiogram signals from a benchmark dataset,” Mathematics, vol. 12, no. 17, 2024, Art. no. 2693. doi: 10.3390/math12172693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. X. Xing et al., “Non-imaging medical data synthesis for trustworthy ai: A comprehensive survey,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 56, no. 7, pp. 1–35, 2024. doi: 10.1145/3614425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. J. Qin et al., “A novel temporal generative adversarial network for electrocardiography anomaly detection,” Artif. Intell. Med., vol. 136, no. 1, 2023, Art. no. 102489. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2023.102489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. S. Ma, J. Cui, W. Xiao, and L. Liu, “Deep learning-based data augmentation and model fusion for automatic arrhythmia identification and classification algorithms,” Comput. Intell. Neurosci., vol. 2022, no. 1, 2022, Art. no. 1577778. doi: 10.1155/2022/1577778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. S. Chopannejad, A. Roshanpoor, and F. Sadoughi, “Attention-assisted hybrid cnn-bilstm-bigru model with smote-tomek method to detect cardiac arrhythmia based on 12-lead electrocardiogram signals,” Digit. Health, vol. 10, 2024, Art. no. 20552076241234624. doi: 10.1177/20552076241234624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. M. Zubair, S. Woo, S. Lim, and D. Kim, “Deep representation learning with sample generation and augmented attention module for imbalanced ECG classification,” IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform., 2023. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2023.3325540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. H. M. Rai, K. Chatterjee, and S. Dashkevych, “The prediction of cardiac abnormality and enhancement in minority class accuracy from imbalanced ecg signals using modified deep neural network models,” Comput. Biol. Med., vol. 150, 2022, Art. no. 106142. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. C. Liu, S. Cheng, W. Ding, and R. Arcucci, “Spectral cross-domain neural network with soft-adaptive threshold spectral enhancement,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., 2023. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3332217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. A. Sellami and H. Hwang, “A robust deep convolutional neural network with batch-weighted loss for heartbeat classification,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 122, no. 1, pp. 75–84, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2018.12.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. N. Wang, P. Feng, Z. Ge, Y. Zhou, B. Zhou and Z. Wang, “Adversarial spatiotemporal contrastive learning for electrocardiogram signals,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., 2023. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3272153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Y. Li, R. Qian, and K. Li, “Inter-patient arrhythmia classification with improved deep residual convolutional neural network,” Comput. Methods Programs Biomed., vol. 214, 2022, Art. no. 106582. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106582. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. L. Sun, Y. Wang, Z. Qu, and N. N. Xiong, “BeatClass: A sustainable ECG classification system in IoT-based eHealth,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 9, no. 10, pp. 7178–7195, 2021. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2021.3108792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. G. B. Moody and R. G. Mark, “The impact of the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database,” IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 45–50, 2001. doi: 10.1109/51.932724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. A. L. Goldberger et al., “PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals,” Circulation, vol. 101, no. 23, pp. e215–e220, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. G. S. Stergiou et al., “A universal standard for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices: Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation/European Society of Hypertension/International Organization for Standardization (AAMI/ESH/ISO) Collaboration Statement,” Hypertension, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 368–374, 2018. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. M. M. Rahman, M. W. Rivolta, F. Badilini, and R. Sassi, “A systematic survey of data augmentation of ECG signals for AI applications,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 11, 2023, Art. no. 5237. doi: 10.3390/s23115237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. I. Silva and G. B. Moody, “An open-source toolbox for analysing and processing physionet databases in MATLAB and Octave,” J. Open Res. Softw., vol. 2, no. 1, 2014, Art. no. e27. doi: 10.5334/jors.bi. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. M. Huang, J. Zou, Y. Zhang, U. A. Bhatti, and J. Chen, “Efficient click-based interactive segmentation for medical image with improved Plain-ViT,” IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform., pp. 1–12, 2024. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2024.3392893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Z. Xu et al., “Multimodality data augmentation network for arrhythmia classification,” Int. J. Intell. Syst., vol. 2024, no. 1, 2024, Art. no. 9954821. doi: 10.1155/2024/9954821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. S. Yan, Y. Xiong, and D. Lin, “Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 32, no. 1, 2018. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v32i1.12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. E. Keogh, K. Chakrabarti, M. Pazzani, and S. Mehrotra, “Dimensionality reduction for fast similarity search in large time series databases,” Knowl. Inf. Syst., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 263–286, 2001. doi: 10.1007/PL00011669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. H. Kong, H. C. Akakin, and S. E. Sarma, “A generalized laplacian of gaussian filter for blob detection and its applications,” IEEE Trans. Cybern., vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1719–1733, 2013. doi: 10.1109/TSMCB.2012.2228639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. D. P. Kingma, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

33. B. W. Salim, B. K. Hussan, Z. S. Ageed, and S. R. Zeebaree, “Improved transient search optimization with machine learning based behavior recognition on body sensor data,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 4593–4609, 2023. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2023.037514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. A. Shoughi and M. B. Dowlatshahi, “A practical system based on CNN-BLSTM network for accurate classification of ECG heartbeats of MIT-BIH imbalanced dataset,” in 2021 26th Int. Comput. Conf. Comput. Soc. Iran (CSICC), IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

35. S. Mousavi, F. Afghah, F. Khadem, and U. R. Acharya, “ECG language processing (ELPA new technique to analyze ECG signals,” Comput. Methods Programs Biomed., vol. 202, no. 1, 2021, Art. no. 105959. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.105959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. S. U. Hassan, M. S. Mohd Zahid, T. A. Abdullah, and K. Husain, “Classification of cardiac arrhythmia using a convolutional neural network and bi-directional long short-term memory,” Digit. Health, vol. 8, 2022, Art. no. 20552076221102766. doi: 10.1177/20552076221102766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. A. Eleyan and E. Alboghbaish, “Electrocardiogram signals classification using deep-learning-based incorporated convolutional neural network and long short-term memory framework,” Computers, vol. 13, no. 2, 2024, Art. no. 55. doi: 10.3390/computers13020055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. H. El-Ghaish and E. Eldele, “ECGTransForm: Empowering adaptive ECG arrhythmia classification framework with bidirectional transformer,” Biomed. Signal Process. Control, vol. 89, no. 1, 2024, Art. no. 105714. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. S. Ma, J. Cui, C. -L. Chen, X. Chen, and Y. Ma, “An effective data enhancement method for classification of ECG arrhythmia,” Measurement, vol. 203, 2022, Art. no. 111978. doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools