Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimizing Airline Review Sentiment Analysis: A Comparative Analysis of LLaMA and BERT Models through Fine-Tuning and Few-Shot Learning

1 Department of Digital Systems, University of Peloponnese, Sparta, 23100, Greece

2 Department of Informatics and Telecommunications, University of Peloponnese, Tripoli, 22131, Greece

3 Department of Agribusiness and Supply Chain Management, School of Applied Economics and Social Sciences, Agricultural University of Athens, Athens, 11855, Greece

* Corresponding Author: Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing AI Applications through NLP and LLM Integration)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 2769-2792. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.059567

Received 11 October 2024; Accepted 24 December 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

In the rapidly evolving landscape of natural language processing (NLP) and sentiment analysis, improving the accuracy and efficiency of sentiment classification models is crucial. This paper investigates the performance of two advanced models, the Large Language Model (LLM) LLaMA model and NLP BERT model, in the context of airline review sentiment analysis. Through fine-tuning, domain adaptation, and the application of few-shot learning, the study addresses the subtleties of sentiment expressions in airline-related text data. Employing predictive modeling and comparative analysis, the research evaluates the effectiveness of Large Language Model Meta AI (LLaMA) and Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) in capturing sentiment intricacies. Fine-tuning, including domain adaptation, enhances the models' performance in sentiment classification tasks. Additionally, the study explores the potential of few-shot learning to improve model generalization using minimal annotated data for targeted sentiment analysis. By conducting experiments on a diverse airline review dataset, the research quantifies the impact of fine-tuning, domain adaptation, and few-shot learning on model performance, providing valuable insights for industries aiming to predict recommendations and enhance customer satisfaction through a deeper understanding of sentiment in user-generated content (UGC). This research contributes to refining sentiment analysis models, ultimately fostering improved customer satisfaction in the airline industry.Keywords

In today’s data-centric world, sentiment analysis plays a pivotal role in uncovering valuable insights from the immense volume of unstructured text data, making it an essential tool across various industries. The airline sector, in particular, stands to gain significantly from the sophisticated application of sentiment analysis, thanks to the copious amount of customer feedback accessible via social media, online review platforms, and other digital mediums. Airlines can significantly improve their service quality, customer satisfaction levels, and operational efficiencies by utilizing such insights. Sensing and understanding consumer perceptions is vital for corporations to deal with positive and negative consumer feedback and to engage prospective consumers with their product or service offerings [1]. The present research focuses on enhancing the process of sentiment analysis for airline reviews, offering an in-depth comparative study of two cutting-edge natural language processing (NLP) models: the newly introduced large language model meta AI (LLaMA-2) Large Language Model (LLM) and the highly regarded Bidirectional Encoder Representations (BERT) from Transformers model.

This study aims to bridge the gap in the existing academic literature by comparing the efficiency of LLaMA-2 and BERT in sentiment analysis and investigating how sophisticated fine-tuning and few-shot learning techniques impact their performance. These models are selected based on their structural differences and distinct advantages in sentiment analysis. BERT has been recognized for its profound bidirectional understanding of textual context, establishing a high standard for NLP tasks. On the other hand, LLaMA-2, with its advanced architectural design, offers the promise of heightened efficiency and precision, potentially setting new benchmarks for NLP tasks.

Our research methodology encompasses a rigorous evaluation framework. In this framework, both models undergo a series of experiments designed to assess their sentiment analysis capabilities, specifically in the context of airline reviews. Through this comparative analysis, we aim to identify which model achieves superior performance in standard benchmark tests and how different fine-tuning strategies, dataset sizes, and few-shot learning scenarios affect their overall effectiveness and adaptability in the nuanced domain of airline sentiment analysis.

Our findings are significant in two ways: They provide actionable insights for airline industry professionals who wish to harness the power of NLP to boost customer experiences and for academic researchers striving to expand the horizons of sentiment analysis capabilities. By systematically unraveling the comparative strengths and limitations of LLaMA-2 and BERT within the specific use case of airline review sentiment analysis, this paper contributes to the ongoing discourse on the evolution of NLP technologies and their application in real-world scenarios.

Throughout our research, specific questions that prior studies have not adequately addressed will be explored:

Q1: What is the importance of fine-tuning LLMs and NLP models for domain-specific tasks?

Q2: How do the volume and quality of datasets designated for fine-tuning influence the effectiveness of the fine-tuning process?

Q3: To what extent does fine-tuning enhance the effectiveness of LLaMA-2 and BERT for sentiment analysis of airline reviews, and how does it impact the outputs produced by these models?

Q4: Are LLaMA-2 and BERT capable of accurately assessing sentiment in reviews, and in what ways can LLMs and NLP technologies transform dynamic industries like aviation?

The paper begins with a concise literature review in Section 2 to address the research questions outlined earlier. This review seeks to provide readers with a clear understanding of customer sentiment analysis and satisfaction, while offering an overview of models previously employed for similar tasks. Section 3 outlines the methodology employed in our research, including dataset splitting and preprocessing, prompt formulation, model execution, and fine-tuning. Section 4 presents a comparative analysis and evaluation of the models, while Section 5 addresses the research questions and compares the performance of models before and after fine-tuning. Additionally, this section highlights essential insights gathered from the authors’ observations, extracting valuable research statements.

Sentiment analysis, or opinion mining, is a computational method for dissecting and comprehending sentiments, opinions, and attitudes conveyed in textual data [1]. Its primary function involves extracting subjective information from the text to discern whether the prevailing sentiment is positive, negative, or neutral [2].

In comprehending customer sentiments and attitudes towards products or services, sentiment analysis is pivotal. It gives businesses invaluable insights into customer perceptions, preferences, and satisfaction levels, thereby informing strategic decision-making processes [3]. Through the analysis of extensive volumes of customer feedback, reviews, and social media interactions, sentiment analysis facilitates companies in the following ways:

Understanding Customer Sentiments: By discerning how customers perceive their products or services, businesses can pinpoint aspects that resonate positively and areas necessitating improvement [1].

Monitoring Brand Reputation: Continuous monitoring of online discussions and sentiment trends enables companies to manage their brand image effectively, proactively addressing potential PR crises or negative publicity [4,5].

Enhancing Customer Experience: Insight gained from sentiment analysis informs businesses about factors influencing customer satisfaction, enabling tailored improvements and fostering loyalty [6].

Informing Product Development: By uncovering customer preferences and needs, sentiment analysis guides product development efforts, ensuring alignment with market expectations and enhancing competitiveness [5].

Guiding Marketing Strategies: Understanding customer sentiment aids in crafting targeted marketing campaigns that evoke the desired emotional response, thereby driving engagement and fostering brand loyalty [7].

2.1 Sentiment Analysis in the Airline Industry

Sentiment analysis plays a crucial role in the airline industry, serving as a valuable tool for understanding and improving customer satisfaction [8]. Airlines are constantly seeking ways to enhance service quality, and sentiment analysis provides them with invaluable insights into passengers’ experiences. By analyzing the sentiments expressed in customer feedback, reviews, and social media posts, airlines can gauge the overall satisfaction levels of their passengers [9]. This allows them to identify areas that require attention and prioritize improvements to enhance the overall flying experience.

Moreover, sentiment analysis enables airlines to proactively address customer concerns and issues, thereby mitigating potential negative impacts on their reputation [10]. By promptly identifying and resolving issues highlighted by customers, airlines can demonstrate their commitment to delivering exceptional service. This not only helps in retaining existing customers but also in attracting new ones through positive word-of-mouth and online reviews. Additionally, sentiment analysis allows airlines to stay competitive by keeping abreast of evolving customer preferences and trends in the industry, enabling them to adapt their services accordingly [11].

Furthermore, sentiment analysis serves as a valuable tool for benchmarking and performance evaluation within the airline industry [12]. By comparing sentiment scores over time and against competitors, airlines can track their progress in enhancing customer satisfaction and identify areas where they excel or lag behind. This data-driven approach empowers airlines to make informed decisions regarding resource allocation and strategic initiatives aimed at improving service quality [13]. Ultimately, sentiment analysis enables airlines to foster stronger relationships with their customers, drive loyalty, and maintain a competitive edge in the dynamic aviation market.

2.2 Previous Studies on Sentiment Analysis of Airline Reviews

The literature on sentiment analysis of airline reviews reveals a rich landscape of research endeavors. Hong et al. employ text mining to extract major keywords from airline reviews, identify prominent ones, and assess their differential impacts on corporate performance, finding distinctive features in client language and suggesting tailored service management strategies for airlines [14]. Ban et al. focus on understanding customer experience and satisfaction through semantic network analysis of online reviews, identifying key evaluation factors and their impact on customer satisfaction and recommendation within the airline industry [15]. Lacic et al. delve into the features of airline reviews contributing to traveler satisfaction, utilizing both quantitative and qualitative analyses to reveal correlations between review content and satisfaction levels, providing insights into predictive modeling for traveler satisfaction [8]. Siering et al. investigate consumer recommendations in airline reviews, highlighting core service aspects driving recommendation decisions and proposing predictive models incorporating sentiment analysis, offering practical implications for both organizations and prospective travelers [16]. Lucini et al. introduce a novel framework for measuring customer satisfaction in the airline industry through text mining of online customer reviews, identifying dimensions of satisfaction and predicting airline recommendation by customers, thereby providing actionable guidelines for airlines to enhance competitiveness [9]. Patel et al. explore sentiment analysis techniques on airline reviews, comparing machine learning algorithms and demonstrating the superior performance of Google’s BERT model, thereby offering insights into effective sentiment analysis approaches [1]. Brochado et al. investigate themes shared in online reviews by airline travelers, identifying key themes associated with higher and lower value for money ratings, offering valuable insights into airline travelers’ experiences and facilitating the identification of factors influencing value perceptions in the airline industry [11].

Korfiatis et al. advocate for the integration of unstructured data from online reviews, employing topic modeling techniques to complement traditional numerical scores [17]. Their approach highlights the enhanced predictive power of combining textual and numerical features, offering valuable insights for firms’ strategic decision-making processes.

Jain et al. and Yakut et al. delve into the analysis of customer reviews to identify patterns and preferences, employing feature-based and clustering-based modeling techniques [18,19]. By examining in-flight service experiences, these studies aim to understand customer evaluations and improve service quality accordingly, utilizing multivariate regression analysis to model customer groups and predict satisfaction levels.

Jain et al. further explore the predictive capabilities of online reviews, focusing on sentiment analysis to predict customer recommendations [20]. By extracting textual features and explicit ratings, their methodology provides a comprehensive understanding of customer sentiment, aiding managerial decision-making and enhancing service evaluation processes.

Hasib et al. leverage topic modeling and sentiment analysis to extract valuable insights from online reviews, identifying key issues such as seat comfort, service quality, and delays [21]. By analyzing customer feedback from platforms like Skytrax and Tripadvisor, these studies offer actionable recommendations for airlines to address customer concerns and enhance satisfaction levels.

Ahmed et al. propose a methodology for sentiment analysis based on customer review titles, simplifying the process of identifying significant labels to assess customer sentiments [22]. By validating these labels against extensive online reviews, their approach streamlines sentiment analysis and facilitates communication strategies aimed at improving customer perception and service quality.

Chatterjee et al. investigate the impact of user-generated content on consumer evaluations, integrating qualitative and quantitative data through text mining and natural language processing techniques [23]. Their findings underscore the importance of both core and peripheral attributes in shaping customer satisfaction and recommendation behavior, offering insights for review management and service design strategies.

Heidari et al. introduce a novel approach using Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) for sentiment classification of online reviews, enhancing the accuracy of recommender systems for airline tickets [24]. By comparing sentiment classification models and leveraging transfer learning, their methodology provides personalized recommendations based on various aspects of the travel experience.

Sezgen et al. employ Latent Semantic Analysis to analyze online user-generated reviews and identify key drivers of customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction across different airline classes [25]. Their research highlights the nuanced preferences of passengers, emphasizing factors such as staff friendliness, product value, and seat comfort, and offers valuable insights for airline managers seeking to address customer concerns and enhance service quality.

Collectively, these studies underscore the evolving landscape of sentiment analysis in the airline industry, emphasizing the importance of integrating quantitative and qualitative data to gain deeper insights into customer preferences and enhance overall satisfaction levels.

Transformer-based models, epitomized by BERT, have revolutionized the field of NLP due to their remarkable performance across various tasks. BERT and its advancements have significantly enhanced machines’ capabilities to understand and generate human language [26].

At the heart of transformer-based models lies the transformer architecture, which fundamentally differs from previous recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [27]. The transformer architecture utilizes self-attention mechanisms, allowing it to identify relationships between words in a sentence, irrespective of their positions. This attention mechanism allows the model to attend to all words in the input sequence simultaneously, enabling it to understand context more effectively [28].

BERT, in particular, employs a bidirectional approach during pre-training, where it learns to predict missing words from both directions in a sentence [29]. This bidirectional context modeling significantly enhances its understanding of context and semantics. Additionally, BERT utilizes a large corpus of unlabeled text data for pre-training, enabling it to learn robust representations of language features [30].

During fine-tuning for specific tasks such as sentiment analysis, BERT’s pre-trained weights are fine-tuned on task-specific labeled data [31]. This fine-tuning process enables the model to adapt its learned representations to the nuances of the target task, thereby enhancing its performance.

In sentiment analysis, transformer-based models’ architecture and working principles are crucial in their effectiveness. These models excel in discerning sentiment from text by capturing bidirectional context and understanding semantic relationships between words [32]. For instance, in a given sentence, the model can identify individual words conveying sentiment and the nuanced interactions between them, leading to more accurate sentiment classification.

Furthermore, the transformer architecture’s ability to handle long-range dependencies without suffering from the vanishing gradient problem commonly encountered in RNNs makes it particularly suitable for sentiment analysis tasks involving lengthy text sequences [33]. This capability enables transformer-based models like BERT to capture the sentiment expressed throughout a document or conversation, providing more comprehensive insights.

In summary, transformer-based models like BERT have significantly advanced the field of NLP, offering state-of-the-art performance across various tasks, including sentiment analysis. Their architecture, leveraging self-attention mechanisms and bidirectional context modeling, enables them to effectively capture semantic relationships in text, making them highly effective tools for understanding and analyzing sentiment expressed in natural language.

LLaMA-2, an advanced open-source LLM represents a significant advancement over its predecessor, the LLaMA model [34]. Its natural language understanding and generation progress are attributed to its sophisticated design, expanded training data, and improved training methods. LLaMA-2 is tailored to meet the growing demands of various NLP applications, such as text generation, sentiment analysis, machine translation, and question-answering systems [35]. Built upon the transformer model, known for its effectiveness in NLP tasks [36], LLaMA-2 inherits and enhances the multi-layered transformer architecture with self-attention mechanisms [34]. Notably, it boasts a large parameter count (from 7 to 70B) and increased model depth, enabling it to handle complex linguistic patterns and subtleties [37]. Central to LLaMA-2’s capabilities is its extensive training data sourced from various internet platforms, scholarly texts, and textual domains, providing a comprehensive understanding of language and its contexts [34]. This diverse dataset allows LLaMA-2 to perform exceptionally well across multiple languages and domains [36,38].

This study seeks to explore the complex emotional layers present in airline reviews by employing advanced LLM and NLP models, mainly focusing on the cutting-edge LLaMA-2 and BERT models. We aim to deeply understand the psychological states influencing reviewers as they articulate their experiences, capturing the essence of their satisfaction, dissatisfaction, or nuanced ambivalence following airline travel.

To test LLaMA-2 and BERT on detecting word-level sentiments in airline reviews, we first used these models to predict the star ratings on a dataset of airline feedback. Their predictive success with regard to review ratings leads us to ask whether they are also proficient at deciphering language—its emotions, and its meanings. Both models were used in parallel experiments to extract comparative insights.

The early stages of our investigation were dedicated to examining how well the LLaMA base model could identify the subtle emotional expressions in the reviews. Subsequently, Next, we focused on fine-tuning the LLaMA and BERT models specifically for sentiment analysis within airline reviews. This adjustment was designed to improve their ability to detect the nuanced emotional range present in customer feedback.

We observed that the performance of the fine-tuned LLaMA model was noticeably better than the base LLaMA model. This extends our inquiry to understanding more about data volume and quality during fine-tuning process.

The complete codebase for this work, covering everything from data preprocessing and splitting to model fine-tuning, as well as the datasets, is opened publicly in a GitHub repository under an MIT open-source license [39].

Given this study’s scope and intricate processes, we adopted a meticulously crafted research methodology to meet its ambitious objectives. This approach was specifically designed to support the development of reusable Python classes for LLaMA fine-tuning and deploying the BERT model in a cloud environment, ensuring thorough preprocessing and diligent data analysis. The subsequent sections detail the structured framework adopted for our study, offering a precise and systematic plan for our research endeavors.

3.1 Dataset Splitting and Preprocessing

In choosing a dataset for our airline sentiment analysis, we prioritized a source that would deliver a broad spectrum of review features while ensuring the data was from a reliable and authoritative platform. The Airline Reviews dataset, curated by Juhi Bhojani and sourced from Airlinequality.com (accessed on 10 November 2024) [40], emerged as the ideal choice due to several compelling factors.

• Comprehensive airline focus: Our initial review of Kaggle’s offerings revealed 66 datasets related to airline reviews. Many of these datasets were company-specific, such as those for Singapore Airlines or Qatar Airways, or region-specific, like Indian airline reviews. However, our goal was to obtain a dataset that would allow for a generalized analysis of the airline industry without being restricted to particular companies or regions. This approach was essential for achieving globally relevant insights. Among top-tier platforms for airline reviews—Skytrax, TripAdvisor, Airline Ratings, Google Reviews, and Airlinequality.com—the latter stands out. While platforms like TripAdvisor also host airline reviews, they often include off-topic commentary unrelated to in-flight experiences. In contrast, Airlinequality.com specializes solely in airline services, making it highly relevant for an in-depth analysis of air travel experiences, from seating comfort and in-flight entertainment to customer service and food quality.

• Diverse and extensive coverage: The dataset from Airlinequality.com includes over 23,000 reviews of 369 unique airlines, covering both full-service and low-cost carriers worldwide. This diversity enables us to analyze airline experiences comprehensively and generate insights that are applicable to various types of airlines and geographic regions. Additionally, the inclusion of traveler type and flight route information adds contextual richness to the data, which is valuable for nuanced sentiment analysis. The wide range of airlines and customer profiles represented in this dataset ensures that our models can generalize better across different airline brands and passenger demographics.

• High-quality and verified data: Airlinequality.com is a respected source in the airline industry, known for its credible and authentic customer reviews. The platform verifies many of its reviews to ensure their legitimacy, which enhances the reliability of our sentiment analysis results. Because this site is frequently used by travelers and industry professionals alike to gauge service quality, the dataset provides a well-rounded view of customer sentiment. This credibility supports our goal of building a model that can make trustworthy predictions based on genuine feedback. Furthermore, the site’s specialized focus on air travel allows for a more relevant and refined analysis compared to more generalized review sites.

• Optimized for sentiment analysis: The dataset’s structure is particularly well-suited for sentiment analysis, containing essential columns such as Overall_Rating, Review_Title, and Review text. These elements provide a solid foundation for models to learn and predict customer sentiment effectively. While the dataset includes a variety of additional fields, such as seat comfort and inflight services, our analysis prioritized those most relevant to sentiment prediction. By focusing on core features, we enhanced the efficiency of our data preprocessing and model training processes. This targeted approach minimizes noise in the data and maximizes the model’s ability to capture meaningful sentiment patterns specific to the aviation context.

• Balance between detail and simplicity: While some columns, like Route or Date Flown, have inconsistent data entry and could introduce sparsity issues, we intentionally selected fields with high completion rates to maintain data quality. This decision ensured that our models were trained on a cohesive and reliable dataset, improving the overall consistency and performance of the sentiment analysis. At the same time, the exclusion of less relevant features allowed us to streamline our analysis and focus on our primary research goal: understanding and predicting overall customer sentiment.

• Potential for future research: Finally, the richness of the dataset extends beyond our current analysis, offering opportunities for more granular research in the future. Although we focused on sentiment and satisfaction prediction, the dataset’s additional fields, such as traveler type or specific service ratings, could be explored further to analyze particular aspects of customer experiences. This flexibility makes the dataset a valuable resource for a wide range of future studies in the aviation industry.

In our study, while every column held significance, we focused on the serial number, Overall_Rating, Review_Title, and Review columns, employing them for fine-tuning and sentiment analysis.

Our data preparation process was comprehensive and methodical, aimed at improving the quality of our predictive modeling approach. We began by analyzing the unique airline labels in our dataset, discovering reviews from 369 different airlines.

The data preprocessing stage involved several key transformations. We cleaned the text data by removing special characters and unnecessary white spaces to maintain data integrity. This step was crucial in preventing potential noise that could compromise natural language processing techniques.

Text normalization was another important focus. We converted accented characters to their base forms, which was particularly significant for languages with diacritical marks. We also standardized the text by converting all characters to lowercase, ensuring consistent treatment across the dataset.

We refined the dataset by eliminating rows with empty values and removing columns irrelevant to our sentiment analysis. Our data extraction process involved selecting a subset of 6000 rows from the original 23,171 customer reviews.

The dataset partitioning was a critical component of our methodology. We divided the data into training, validation, and test sets through a two-phase approach. This strategic division is essential for developing robust machine learning models that can effectively generalize across different linguistic contexts.

The training set played a pivotal role in the fine-tuning process, allowing the model to learn complex patterns and relationships. Meanwhile, the validation set was instrumental in optimizing model performance by enabling hyperparameter adjustments and preventing overfitting. This careful approach ensures the model’s ability to make accurate predictions and perform effectively on new, unseen data.

The final stage of our modeling process involves evaluating the fine-tuned models using the test set, which completes our comprehensive model refinement and assessment approach. We implemented the stratify parameter in the train_test_split function to ensure balanced representation of the Overall_Rating column across training, validation, and test sets, preventing any potential bias from unseen data during the training process.

To highlight the dataset’s role in natural language processing model development, we created a smaller subset from our original 6000 customer review dataset. This reduced dataset, containing approximately one-third of the original data (1280 training samples and 320 validation samples), was used to further fine-tune the models. Notably, we applied these refined models to the same test set of 1200 samples, allowing for a consistent and comparative evaluation of model performance.

3.2 Creating a Compelling Prompt for the LLaMA Model

Our objective was to develop a universal prompt that could effectively work across multiple LLMs, enhancing the accessibility of their generated outputs through our code. We carefully considered both the prompt’s substantive content and its output formatting.

The process of creating a versatile prompt began with a comprehensive understanding of different language models like GPT-3, GPT-4, and LLaMA-2, each possessing unique capabilities and limitations. Crafting a prompt that could consistently elicit meaningful responses while maintaining broad accessibility presented significant challenges. To overcome these difficulties, we employed two established prompting strategies, taking into account the distinctive characteristics of each language model.

We developed a model-agnostic approach to content creation, designing a prompt that transcends the specific architectural nuances or knowledge bases of individual LLMs. This strategy ensured maximum flexibility and broad applicability across various models. Our primary focus was on constructing a prompt that articulates the task clearly and provides contextual information that any language model could readily comprehend.

Recognizing the critical importance of output formatting for usability, we prioritized creating a response structure that is both coding-friendly and highly accessible. This involved designing an output format that is logically organized and intuitively structured. Specifically, we determined that JSON format would best serve our requirements for structured and easily interpretable results.

After many iterations and tests with different LLMs, we finalized a prompt that effectively generated responses in the desired output format, making it understandable for both the models, as shown in Eq. (1) (Model-Agnostic prompt).

3.3 Model Deployment, Fine-Tuning LLaMA-2 and BERT Models, and Predictive Modeling

This research utilized two distinct models: the NLP BERT model and the LLM LLaMA-2 model. Each model underwent a tailored approach for fine-tuning and predicting airline review ratings.

We utilized the llama-2-7b-chat base model to generate predictions for review ratings in our test set, following a specific prompt outlined in Eq. (1). Our analysis involved a meticulous comparison between the model-generated ratings and the original ratings provided by reviewers.

Given the substantial computational demands of LLaMA models, we leveraged the Replicate API for both prediction generation and model fine-tuning. Drawing a parallel to Azure’s approach with GPT-3, which employs Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) to reduce GPU resource requirements, Replicate similarly applied LoRA techniques—specifically the Quantized LoRA (QLora) method—to optimize the fine-tuning process for the LLaMA model.

Subsequently, we carried out two fine-tuning sessions, which were labeled with the Job IDs kroumeliotis/airline-reviews-6k:a2c027ef [41] and the reduced dataset kroumeliotis/airline-reviews-2k:72e17ade [42].

In the first session, we used 8x A40 (Large) GPUs, and the process took 28 min. The evaluation showed that the language model achieved a perplexity of about 5.40 and an epoch loss of around 1.69. By the third training epoch, the model had a training perplexity of 5.09 and a training epoch loss of 1.63.

For the second session, we also used 8x A40 (Large) GPUs, but this time the total runtime was just 11 min. The evaluation indicated that the language model reached a perplexity of approximately 5.78 and an epoch loss of about 1.76. By the third training epoch, the model’s training perplexity was 5.33, with a training epoch loss of 1.67.

After fine-tuning, the fine-tuned models were employed to predict star ratings for airline reviews in the test data. Subsequently, these results were integrated into the same CSV file for further comparative analysis.

To fine-tune the LLaMA model, we created two JSONL files—one for training and one for validation—each containing pairs of prompts and completions, as shown in Eq. (2) (JSONL file with prompt-completion pairs for Fine-Tuning).

We employed the BERT-base-uncased model from the transformers library, specifically the BertForSequenceClassification variant, for our natural language processing project. This model includes a classification component that converts outputs into probability distributions for different classes [43].

The BERT-base-uncased model processes text in a case-insensitive manner, converting all input to lowercase during training. Its architecture comprises 12 layers, 768 hidden units, 12 attention heads, and approximately 110 million parameters. The model utilizes self-attention mechanisms to understand contextual relationships within input sequences [44].

Our fine-tuning process for sentiment analysis occurred in Google Colab, utilizing an A100 GPU to maximize computational efficiency. We used a dataset of airline reviews and their corresponding ratings, imported from a CSV file stored in Google Drive. The preprocessing stage involved tokenization using the BERT tokenizer.

We configured several key hyperparameters, including a learning rate of 2e-5 and a batch size of 8. The training employed adaptive moment estimation (Adam) and AdamW optimizers. The model underwent training for three epochs, with progress monitoring facilitated by the tqdm library. The training process incorporated backpropagation, optimization, and validation using a separate dataset, with careful GPU resource management.

Upon completing the training, we preserved the fine-tuned model and tokenizer in a Google Drive directory for future use. This comprehensive approach ensured the model was precisely tailored for sentiment classification and prepared for deployment. After training, the model generated predictions on the test dataset, with all associated code and training metrics documented in a GitHub Jupyter notebook [39].

4 Model Performance Comparison and Assessment

Section 3 explores the methodological approach for evaluating the predictive capabilities of two natural language processing models: the LLaMA-2 Large Language Model and the BERT model. The primary objective is to analyze their proficiency in interpreting the nuanced details within star-rated airline reviews. This section presents the comprehensive results from our comparative analysis of these models across various research stages.

4.1 Evaluation of Fine-Tuned Models

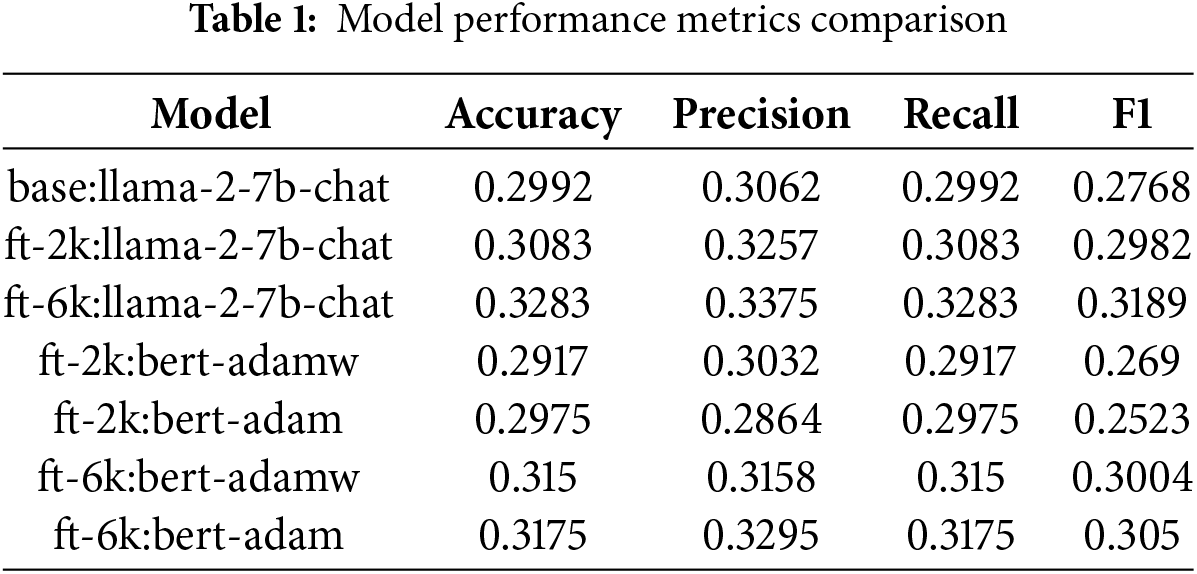

Before delving into our findings, it is essential to underscore the significance of model evaluation. In the domains of machine learning and natural language processing, assessing model performance is critical. This evaluation provides profound insights into the models’ effectiveness following fine-tuning, serving as a strategic tool for making informed decisions about model suitability. Moreover, it facilitates ongoing improvements in model refinement and optimization for specific computational tasks. Table 1 provides an extensive and detailed examination of each model’s performance, encompassing a comprehensive array of pivotal evaluation metrics. This systematic assessment enables a thorough understanding of the models’ strengths, limitations, and potential applications in sentiment analysis of airline reviews.

4.2 LLaMA Base Model Evaluation Phase

In the initial stage of our research, we employed the LLaMA base model (llama-2-7b-chat) to predict star ratings from a test set of 1200 customer reviews. Our primary goal was to assess the large language model’s ability to accurately forecast the star ratings originally assigned by airline customers.

Upon careful comparison of the model’s predictions with actual user-assigned star ratings, we discovered notable insights. The llama-2-7b-chat model, without prior fine-tuning, demonstrated a respectable accuracy of 29.92%, correctly predicting 359 out of 1200 reviews in our test set.

Context is crucial when interpreting these results. In predictive modeling, a 50% accuracy suggests performance no better than random guessing for binary classifications. However, for multi-class scenarios like star ratings ranging from one to ten, the baseline accuracy from random chance is merely 10% (1 out of 10).

Theoretically, an untrained model should achieve around 10% accuracy through random guessing. Any model surpassing this baseline indicates meaningful predictive capabilities. The LLaMA base model’s 29.92% accuracy represents a significant improvement over random chance, highlighting its potential to discern subtle patterns within review data.

These accuracy figures underscore the model’s ability to identify and extract meaningful insights from the dataset, showcasing its capacity to generate predictions that are substantially more reliable than random guessing.

Nevertheless, the model’s performance could be substantially improved through specialized fine-tuning, which would enhance its capability to recognize and interpret complex data patterns and relationships.

4.3 Fine-Tuned Models Evaluation Phase

In the next phase of our research, we fine-tuned both the LLaMA and BERT models using two different optimizers. The fine-tuning process utilized a training dataset of 3840 airline customer reviews, with the primary objective of improving model performance and adapting the models more precisely to our specific task.

After completing the fine-tuning process, we evaluated the models’ predictive capabilities on the same test dataset. The results were notably encouraging. The LLaMA-2 model demonstrated significant improvement, increasing its accuracy to 32.83%, correctly predicting 394 out of 1200 reviews in the test set.

The BERT model showed comparable performance during fine-tuning. When using the ADAMW optimizer, the model achieved an accuracy of 31.5%. Interestingly, switching to the ADAM optimizer yielded a slight performance boost, with the model reaching an accuracy of 31.75% in its predictions.

These results highlight the potential of fine-tuning in enhancing model performance, with both LLaMA-2 and BERT models showing marked improvements in their ability to predict star ratings for airline reviews.

4.4 Evaluation of Fine-Tuned Models on One-Third of the Dataset

We investigated the impact of training dataset size on NLP model fine-tuning by repeating the process with a reduced dataset of approximately one-third of the original, using 1280 samples instead of the initial 3840.

In this experiment, the LLaMA-2 model demonstrated remarkable consistency. Despite the smaller training set, it maintained strong performance, achieving an accuracy of 30.83% and correctly predicting 370 out of 1200 test samples. The BERT model showed similar resilience, reaching an accuracy of 29.17% with the ADAMW optimizer. Switching to the ADAM optimizer marginally improved its performance to 29.75%.

While these accuracy rates are impressive, it’s crucial to recognize that NLP models, especially LLMs, typically generate more precise predictions when trained on larger datasets. The 3840 samples used in this study, while substantial, may not fully represent the potential performance achievable with even more extensive training data.

4.5 Assessing Models’ Performance and Proximity with Original Ratings

To thoroughly evaluate the performance of both base and fine-tuned models and examine how closely their predictions aligned with the original reviewer ratings, we applied the mean_absolute_error metric from the scikit-learn library. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) served as a crucial statistical tool to measure the deviation between model predictions and actual ratings for both the base and fine-tuned models.

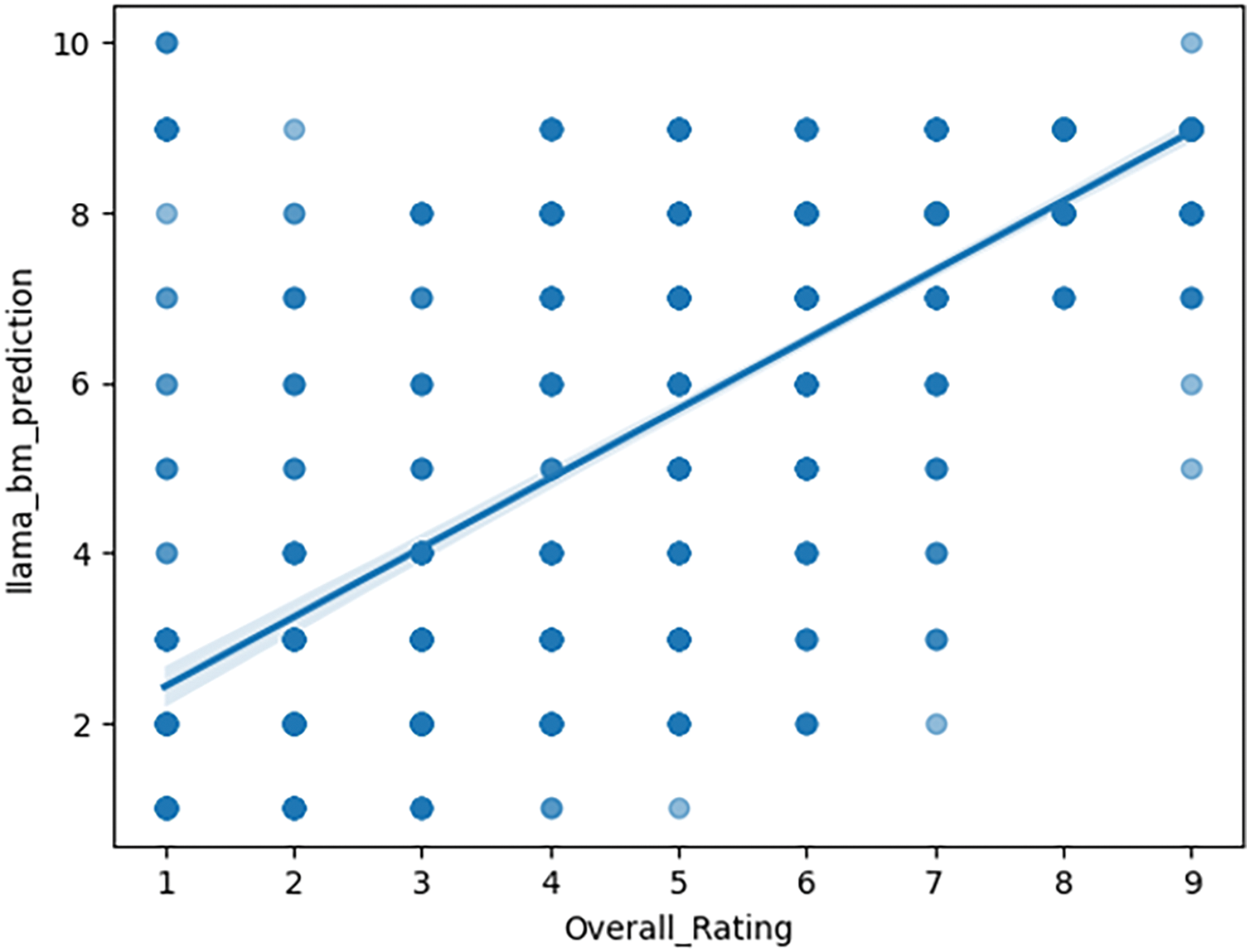

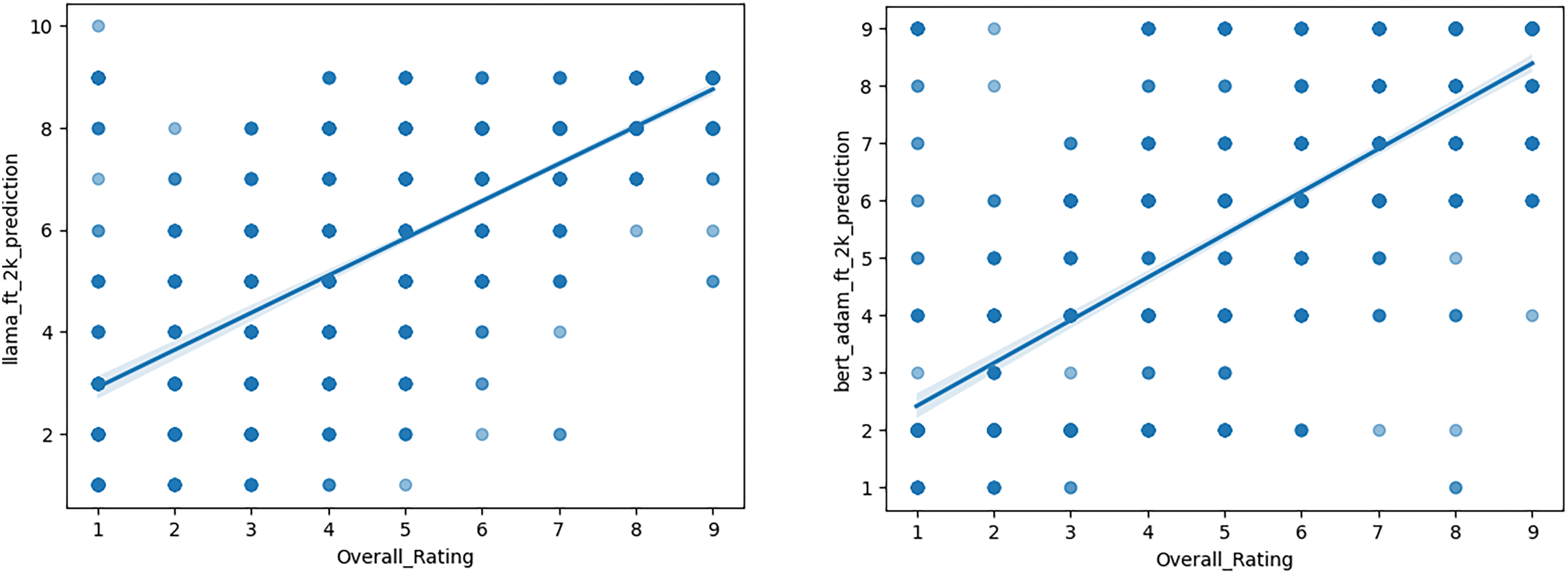

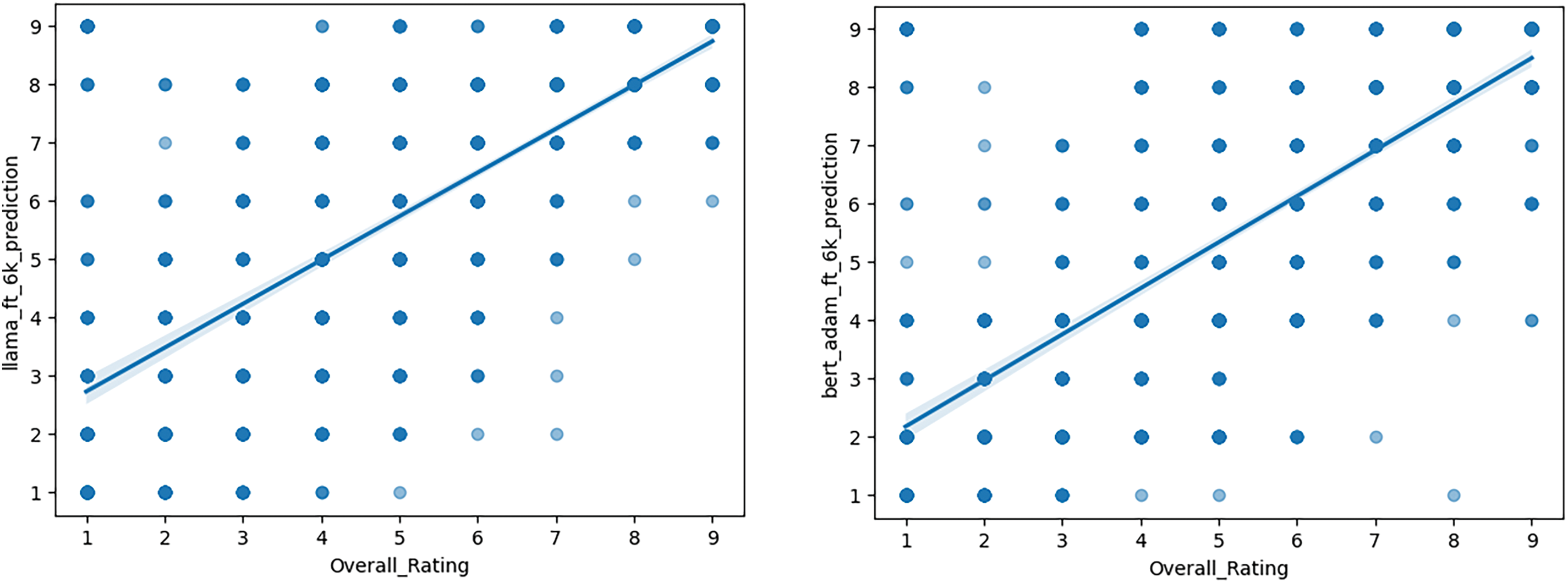

The results of this comparative analysis are visually represented in Figs. 1–3 using scatterplots. These visualizations include an ideal fit line, which represents the points where model predictions exactly match the original ratings. By plotting the predictions against the actual values, we created a clear visual representation of the models’ predictive accuracy and potential systematic biases in their rating forecasts.

Figure 1: MAE for LLaMA base model

Figure 2: MAE for fine-tuned models trained on a 2k dataset

Figure 3: MAE for fine-tuned models trained on a 6k dataset

The Mean Absolute Errors (MAEs) provide important insights into the performance of different NLP models under various fine-tuning settings. A lower MAE indicates that the model’s predictions are, on average, closer to the actual values, reflecting better accuracy and predictive power.

The base llama-2-70b-chat model has an MAE of 1.403, which represents the average absolute difference between its predictions and the true values. After fine-tuning with the complete training set (100%), the LLaMA model shows notable improvement, resulting in a significantly reduced MAE of 1.325. Additionally, when fine-tuned using only one-third of the training data, the MAE was recorded at 1.363.

Similarly, the BERT model, when trained on the entire training dataset, achieved MAEs of 1.255 (ADAMW) and 1.28 (ADAM), while training on the 1/3 training set resulted in MAEs of 1.33 (ADAMW) and 1.319 (ADAM), respectively.

Visualizing these results in scatterplots also aids in better understanding our dataset. Despite our initial assumption of dataset balance, encompassing all labels from 1 to 10, examination of the scatterplots revealed the absence of label 10 in our dataset. This absence does not impact the training of the BERT model. However, during fine-tuning and prediction with the LLaMA model, the prompt explicitly requests predictions from 1 to 10. The LLaMA model strictly adheres to these instructions and includes all ten labels in its predictions, making it vulnerable to such cases.

In the earlier sections, we explored the methods and results related to the predictive performance of the LLaMA-2 LLM and the BERT NLP model in evaluating star ratings for airline customer reviews. This section presents the research outcomes and insights gained about the use of LLMs for sentiment analysis in customer feedback, addressing key research questions.

5.1 The Importance of Domain-Specific Fine-Tuning

• Research Question 1: What is the importance of fine-tuning LLMs and NLP models for domain-specific tasks?

• Research Statement 1: Fine-tuning LLMs and NLP models for domain-specific tasks is essential for enhancing model performance and applicability in real-world scenarios. By adapting them to grasp domain-specific nuances and patterns, we can improve their performance and applicability.

Fine-tuning LLMs and NLP models for specific tasks is essential for maximizing their effectiveness in practical applications. Models like Meta’s LLaMA-2 series and BERT are initially trained on extensive datasets covering a wide range of topics, which equips them to generate and understand human-like text in various contexts. However, adapting these models for particular domains significantly boosts their performance in specialized areas.

For instance, the base llama-2-7b-chat model recorded an accuracy of 29.92% in predicting review ratings. After undergoing fine-tuning with the complete dataset, this accuracy increased to 32.83%. This notable improvement of about 3% underscores the importance of fine-tuning LLMs such as LLaMA-2-7B for specialized tasks. By customizing the model to focus on review ratings, it can more effectively learn the specific patterns and nuances relevant to this field, leading to better predictive outcomes.

Fine-tuning helps the model tailor its existing knowledge to the unique aspects of the target task and dataset. In the context of predicting review ratings, this includes learning to identify sentiment, interpret context, and extract key features from textual data. Through iterative refinement during the fine-tuning process with training and validation datasets, the model enhances its ability to recognize these specific subtleties, resulting in improved performance metrics, including accuracy.

5.2 The Importance of Data Quantity and Quality in Fine-Tuning

• Research Question 2: How do the volume and quality of datasets designated for fine-tuning influence the effectiveness of the fine-tuning process?

• Research Statement 2: The quality and volume of the dataset play a more significant role than fine-tuning parameters in fine-tuning LLMs. Conducting human evaluations of the dataset before fine-tuning and utilizing larger datasets are vital measures to safeguard LLMs against inaccurate predictions and unbalanced datasets.

In Section 4.4, we aimed to explore how the quantity of training data affects the performance of LLM and NLP models. To do this, we randomly selected one-third of the reviews from the original training set to create a new subset. Both models were fine-tuned using this subset and tested on the same set of customer reviews to predict star ratings.

In our analysis of model performance, we observed significant variations in accuracy when contrasting models trained on one-third of the dataset with those utilizing the complete dataset. The fine-tuned LLaMA-2 model experienced a 2% drop in accuracy and a 1.18% reduction in precision compared to the version trained on the full dataset. Likewise, the BERT model displayed a decrease of 2.04% in accuracy and a 4.31% decline in precision. These findings underscore the critical role that the volume of training data plays in determining the effectiveness and reliability of the models.

Additionally, the scatterplots presented in Section 4.5 helped us understand the dataset better. Despite assuming a balanced dataset with labels ranging from 1 to 10, examining the scatterplots revealed the absence of label 10. While this absence doesn’t affect the BERT model, it presents a challenge during fine-tuning and prediction with the LLaMA model, which strictly adheres to the instruction to predict within the 1 to 10 range. Figs. 1 and 2 illustrate this point, showing that the LLaMA models trained on a smaller dataset predict label “10”, while those trained on larger datasets refrain from doing so.

These findings demonstrate that LLMs can be affected by unbalanced data and misleading prompts. To mitigate this, it’s crucial to conduct human evaluations of the data before fine-tuning and consider using larger training sets to allow the LLMs to adapt to dataset nuances and features. In contrast, NLP models rely on statistics and are not dependent on human-crafted prompts, making them more adaptable for tasks involving unbalanced data.

5.3 Fine-Tuned Models Comparison

• Research Question 3: To what extent does fine-tuning enhance the effectiveness of LLaMA-2 and BERT for sentiment analysis of airline reviews, and how does it impact the outputs produced by these models?

• Research Statement 3: The LLaMA-2 fine-tuned model exhibits slightly greater predictive capabilities than the BERT fine-tuned model, and fine-tuning significantly refines output structure and adherence to specified formats, ensuring more accurate and contextually appropriate responses.

Our research in Section 4.2 investigated the comparative effectiveness of fine-tuned LLaMA-2 and BERT models, trained on a dataset of 6000 airline customer reviews and tested on a sample of 1200 reviews for sentiment analysis. Findings indicate that LLaMA-2, after fine-tuning, demonstrated a slight but measurable performance advantage over BERT, achieving a 1.08% higher accuracy in predicting customer review sentiment. This performance edge can be attributed to several architectural and training distinctions between the two models.

LLaMA-2, designed with over 7 billion parameters [34], possesses a significantly larger capacity for learning compared to BERT, which comprises 110 million parameters [44]. The large parameter count in LLaMA-2 allows for a deeper and more nuanced representation of language patterns, particularly beneficial for complex language tasks like sentiment analysis, where subtle variations in phrasing and tone can significantly affect interpretation. Additionally, LLaMA-2’s extensive pre-training phase exposed it to a broader and more diverse range of public datasets, providing it with a more comprehensive foundational understanding of various linguistic nuances.

This robust pre-training process likely enhanced LLaMA-2’s ability to capture domain-specific expressions and subtle sentiment shifts often found in airline reviews, such as context-dependent language related to travel experiences, customer service interactions, and emotional tone. In contrast, BERT, while effective and widely used for many NLP tasks, was pre-trained on a comparatively smaller dataset and was not designed with as high a parameter count, limiting its depth of language comprehension and, consequently, its precision when fine-tuned for specific applications like airline sentiment analysis.

The marginal but consistent performance advantage of LLaMA-2 in this study underscores the role of model architecture and scale in enhancing predictive capabilities, especially when adapted for nuanced, domain-specific tasks. Fine-tuning builds on these inherent strengths by further aligning the model’s understanding with the targeted dataset, allowing models like LLaMA-2 to leverage their comprehensive pre-training to excel in specialized applications.

Furthermore, examining the output structure before and after fine-tuning reveals the substantial impact of fine-tuning on the models’ adherence to specified response formats. In Section 3.3.1, the LLaMA-2 base model’s unstructured outputs deviated from the requested JSON format, producing full-text explanations in 14 out of 1200 cases. This inconsistency suggests that while pre-trained models possess general predictive capabilities, they may lack reliability in generating structured outputs specific to the task requirements.

However, after fine-tuning, the LLaMA-2 model consistently produced accurate and structured responses in JSON format, even when handling varied inputs. This improvement underscores the role of fine-tuning in stabilizing model behavior, adapting prediction structures, and aligning outputs to meet the requirements of domain-specific tasks. In summary, fine-tuning not only enhances prediction accuracy but also ensures that models like LLaMA-2 can reliably generate task-specific, structured outputs, emphasizing the critical importance of fine-tuning for improving model performance and applicability in real-world industry settings.

5.4 Comparing Fine-Tuning and Prediction Performance: LLMs vs. Non-LLM NLP Models

• Research Question 4: Are LLaMA-2 and BERT capable of accurately assessing sentiment in reviews, and in what ways can LLMs and NLP technologies transform dynamic industries like aviation?

• Research Statement 4: Both the LLaMA-2 and BERT models have shown proficiency in accurately predicting sentiment in airline customer reviews. Although LLaMA-2 boasts a slightly higher accuracy rate, balancing this against the economic factors involved in fine-tuning and predictions and aligning with the desired accuracy levels set for the project is crucial.

The research findings reveal that LLaMA-2 and BERT models, following meticulous fine-tuning, exhibit remarkable proficiency in predicting sentiment from airline customer reviews. Their performance surpasses base random chance predictions by a significant margin, underscoring the efficacy of transformer-based models in sentiment analysis and classification endeavors.

To address the resource intensity of fine-tuning LLaMA-2 and provide a comprehensive analysis of the trade-offs between computational expense and performance gains, we compared the fine-tuning costs of the LLaMA-2-7b-chat model with a traditional transformer-based model, BERT, using datasets of different sizes. For a dataset of 6000 samples, fine-tuning LLaMA-2 on 8 A40 GPUs took 28 min and cost $19.41, while fine-tuning on a smaller 2000-sample dataset took 11 min and cost $7.62. In stark contrast, BERT required only a single A100 GPU on Google Colab, with fine-tuning times of 361 s ($1.04) and 121 s ($0.35) for the 6000-sample and 2000-sample datasets, respectively. These findings reveal a fundamental trade-off: while LLMs like LLaMA-2 offer the potential for improved accuracy due to their extensive pretraining and billions of parameters, this comes at a significant cost in computational resources, time, and budget. For instance, the fine-tuning of LLaMA-2 on a 6k dataset was nearly 19 times more expensive than that of BERT, despite both models achieving strong predictive performance in sentiment analysis.

This stark disparity raises critical questions about the cost-effectiveness and practicality of deploying LLMs in real-world applications. While LLaMA-2’s ability to process and learn from large datasets may yield slight improvements in performance metrics such as accuracy or F1 score, the associated costs make its application less feasible for organizations with limited budgets or those operating under resource constraints. Furthermore, the time required for fine-tuning LLaMA-2 can introduce additional delays in workflows where rapid model development and deployment are priorities. These considerations are particularly relevant for small-to-medium enterprises, educational institutions, and researchers in resource-constrained environments, where the marginal performance gains of LLaMA-2 may not justify its disproportionately higher resource demands.

On the other hand, BERT’s lower computational requirements make it a compelling choice for scenarios where computational efficiency and cost-effectiveness are paramount. Its ability to achieve competitive results with significantly less resource investment enables broader accessibility and scalability, particularly in cases where budgetary constraints or environmental sustainability are key concerns. However, it is important to acknowledge that the performance gap, even if small, between BERT and LLaMA-2 could be decisive for high-stakes applications such as medical diagnosis, legal document analysis, or financial forecasting, where the cost of errors outweighs computational expenses.

This analysis highlights the importance of a tailored approach to model selection. Stakeholders must weigh the trade-offs between accuracy and resource expenditure based on their specific goals, available resources, and operational constraints. For instance, while organizations prioritizing cutting-edge performance may favor LLaMA-2 despite its higher cost, others focused on cost minimization and widespread adoption may find BERT more suitable. Additionally, the scale of the dataset plays a pivotal role in determining the practicality of these models. Large datasets tend to amplify the resource demands of LLaMA-2, further widening the cost-performance gap compared to BERT. This suggests that BERT could remain a more economical choice for medium-sized datasets or iterative workflows where rapid experimentation is required.

Moreover, these findings have broader implications for the responsible and sustainable use of AI. The high energy consumption and associated carbon footprint of LLMs like LLaMA-2 necessitate a deeper consideration of their environmental impact, especially as AI adoption continues to scale globally. Organizations should explore hybrid approaches, such as leveraging smaller, domain-specific models where feasible or employing efficient fine-tuning techniques like parameter-efficient transfer learning (e.g., LoRA or adapters) to mitigate the computational costs of LLMs.

In summary, while LLaMA-2 represents a significant advancement in the capabilities of LLMs, its resource intensity underscores the need for careful decision-making in AI deployment. The choice between models like LLaMA-2 and BERT should be guided not only by performance metrics but also by practical considerations such as cost, time, and environmental sustainability. By aligning model selection with specific use cases and operational priorities, stakeholders can harness the power of AI more effectively and responsibly.

5.5 Explainability in Sentiment Analysis Models

To gain deeper insights from our study, we chose to further analyze the predictions made by the trained models using model explainability techniques. There are several established methodologies for explaining model predictions in NLP, including approaches such as Top Influential Words [45], SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [46], and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) [47].

In this study, we opted for the Top Influential Words approach rather than SHAP or LIME for several practical reasons. Both SHAP and LIME are powerful tools for model interpretability, but they typically require direct access to the trained model’s internal architecture and the ability to load the model locally for making perturbations. Given that we fine-tuned the LLaMA model via the Replicate API, which does not provide access to the model’s internal parameters, implementing SHAP or LIME in this context would not have been feasible.

As a result, the Top Influential Words methodology, which involves identifying and analyzing the words that most strongly influence the model’s sentiment predictions, became a more practical and accessible choice for explainability in our case. This approach enabled us to better understand the model’s decision-making process without needing direct access to its internal structure.

• Objective: The primary goal of this methodology is to explore and visualize the most influential words that contribute to sentiment predictions made by the BERT and LLaMA models. By examining these words, we can uncover how each model interprets and processes the sentiment expressed in customer reviews. This step is crucial for understanding model behavior and ensuring that predictions align with human interpretable features of sentiment.

• Dataset: We utilized the test set containing airline reviews, each paired with a sentiment rating predictions for both of our models ranging from 1 to 10. The reviews provide textual feedback from customers, reflecting their experiences with the airline. The sentiment ratings correspond to the level of satisfaction the customers felt, with higher ratings indicating positive sentiment and lower ratings reflecting negative sentiment. This dataset serves as the foundation for analyzing the models’ predictions and their underlying decision-making processes.

• Text preprocessing: Before analyzing the sentiment models, we applied a series of preprocessing steps to ensure that the text was in a suitable format for analysis. These steps included lowercasing, tokenization, stopword removal, punctuation removal, and lemmatization. Lowercasing ensured uniformity by converting all text to lowercase, while tokenization broke the text into individual words or tokens. Stopword removal eliminated common but uninformative words (e.g., “and”, “the”), and punctuation removal helped focus on the core content of the text. Additionally, lemmatization was applied to reduce words to their base form, ensuring that different inflections of the same word were treated as a single entity. These preprocessing steps collectively helped our program capture the words that were more influential in the models’ predictions.

• Creating word occurrence dictionaries for sentiment ratings: To understand the influence of specific words on sentiment classification, we created a dictionary to track word occurrences for each sentiment rating (1 to 10). Each sentiment rating has its own sub-dictionary, and we populate these dictionaries by iterating through the reviews.

• For each review, we extracted the processed words (after preprocessing) and associated them with the rating predicted by either the BERT or LLaMA model. This allows us to track the frequency of each word in reviews that correspond to a specific sentiment rating, enabling us to identify which words are most commonly associated with particular sentiment levels.

• Once the word occurrences were tracked for each rating, we identified the most influential words for each sentiment rating. A function was used to select the most frequent words for each rating, sorting them by their frequency and selecting the top words as depicted on Eq. (3) (Fine-Tuned LLaMA-2 Top Influential Words), and Eq. (4) (Fine-Tuned BERT Top Influential Words). This process enabled us to highlight the key words that each model uses to classify sentiment. For instance, words like “service”, “flight”, “seat”, and “good” might appear frequently for high ratings, while words such as “never”, “luggage”, and “delay” might be common for lower ratings.

5.5.1 Key Observations for the LLaMA Model

Low Ratings (1–4): For ratings 1–4, words like “flight”, “airline”, “hour”, “time”, “service”, “seat”, and “customer” consistently appear. These words suggest that the LLaMA model associates negative sentiments with common pain points such as issues with the flight experience, poor service, uncomfortable seats, or delays.

• Rating 1: The words “never”, “luggage”, and “even” are notable, implying frustration and negative experiences (e.g., “never again”, baggage issues).

• Ratings 2 and 3: Words like “seat” and “service” appear more frequently, indicating dissatisfaction with physical comfort and the quality of service.

Moderate Ratings (5–6): For ratings 5–6, a mix of negative words like “flight”, “seat”, and “time” is observed, along with some positive indicators such as “good” and “would”. This suggests that, while there are issues, there is also some level of neutral or slightly positive sentiment.

• Rating 5: Words like “crew” and “food” are more prominent, pointing to dissatisfaction with service and in-flight amenities, though these are not necessarily the most critical issues.

Higher Ratings (7–9): For higher ratings, words like “good”, “service”, “food”, and “seat” become more prominent, indicating that the LLaMA model associates comfort (e.g., seats, food) and good service with positive sentiment.

• Rating 8: Words such as “good”, “service”, “flight”, and “seat” dominate, suggesting that positive experiences are primarily driven by these factors.

5.5.2 Key Observations for the BERT Model

Low Ratings (1–4): Similar to LLaMA, BERT associates negative sentiment with common pain points such as “flight”, “airline”, “seat”, “time”, “service”, and “hour”.

• Rating 1: Words like “never”, “bag”, and “airport” are notable, indicating a highly negative sentiment towards the flight process, including issues with luggage and airport service.

• Ratings 2 and 3: Similar to LLaMA, “seat” and “service” are strong indicators of dissatisfaction. However, BERT also emphasizes issues related to the plane and staff, suggesting it may place additional importance on these operational aspects.

Moderate Ratings (5–6): For ratings 5–6, the appearance of words like “good”, “food”, and “service” signals a shift toward slightly more positive sentiment, although complaints about comfort and service remain prevalent.

• Rating 5: Similar to LLaMA, words like “food”, “service”, and “cabin” are prominent, indicating dissatisfaction with specific aspects like meals and seating. However, the sentiment is less negative than in the lower ratings.

Higher Ratings (7–9): Higher ratings in BERT are more strongly associated with positive words such as “good”, “food”, “seat”, “service”, and “flight”. There’s also a significant emphasis on “crew” and “cabin”, suggesting that BERT associates satisfaction with the overall service and comfort of the flight.

• Rating 8: Positive terms like “good”, “service”, and “flight” dominate, similar to LLaMA. However, BERT places more emphasis on the word “friendly” (as in “friendly service”), highlighting a more personal experience aspect in its interpretation of positive sentiment.

5.5.3 Key Differences between LLaMA and BERT in Sentiment Analysis

While both models focus on key aspects of the flight experience (such as “flight”, “airline”, “seat”, and “service”), LLaMA appears to place a heavier emphasis on “luggage” and “staff”, which suggests it may be more sensitive to certain operational aspects of the airline experience. BERT, on the other hand, frequently highlights “friendly” and “boarding”, possibly indicating a stronger focus on the personal experience and interpersonal aspects of the flight.

Both models start to associate positive terms like “good”, “food”, and “service” with higher ratings, but BERT is slightly more inclined to emphasize “friendly” interactions and service aspects, which could reflect a more holistic view of customer service in sentiment analysis.

Ultimately, both models identify similar aspects of the airline experience (e.g., flight comfort, service quality, and time issues), but the differences in their focus could suggest nuances in how each model interprets sentiment and customer feedback. This analysis gives us insights into which terms each model considers most representative, influencing their predictions.

This paper investigates the performance of two advanced sentiment analysis models, LLaMA-2 and BERT, in the context of airline review sentiment analysis. The study addresses the nuances of sentiment expression in airline-related text data through meticulous fine-tuning, domain adaptation, and the innovative application of few-shot learning. Both models demonstrate remarkable proficiency in predicting sentiment from airline customer reviews, with LLaMA-2 exhibiting a slight accuracy advantage owing to its pretraining with billions of parameters. However, the resource demands for fine-tuning and prediction with LLaMA-2 pose economic considerations compared to the more resource-efficient NLP models. By providing valuable insights into model effectiveness and resource trade-offs, this research aids industries in predicting recommendations and enhancing customer satisfaction through a deeper understanding of sentiment in user-generated content, ultimately contributing to improved customer experiences in the airline industry.

Acknowledgment: The authors have no external support to acknowledge for this study.

Funding Statement: This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis and Nikolaos D. Tselikas.; methodology, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis, Nikolaos D. Tselikas and Dimitrios K. Nasiopoulos; software, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis; validation, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis and Nikolaos D. Tselikas.; formal analysis, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis, Nikolaos D. Tselikas and Dimitrios K. Nasiopoulos; investigation, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis, Nikolaos D. Tselikas and Dimitrios K. Nasiopoulos; resources, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis; data curation, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis; writing—original draft preparation, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis and Nikolaos D. Tselikas; writing—review and editing, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis, Nikolaos D. Tselikas and Dimitrios K. Nasiopoulos; visualization, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis; supervision, Nikolaos D. Tselikas and Dimitrios K. Nasiopoulos. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data supporting the reported results can be found at reference [39].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Patel A, Oza P, Agrawal S. Sentiment analysis of customer feedback and reviews for airline services using language representation model. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023 Jan;218(1):2459–67. doi:10.1016/J.PROCS.2023.01.221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Villegas-Ch W, Molina S, Janón VDe, Montalvo E, Mera-Navarrete A. Proposal of a method for the analysis of sentiments in social networks with the use of R. Informatics. 2022 Aug;9(3):63. doi:10.3390/INFORMATICS9030063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Villalba G, Plosc˘ T-R, Curiac C-D, Curiac D-I. Investigating semantic differences in user-generated content by cross-domain sentiment analysis means. Appl Sci 2024. 2024 Mar;14(6):2421. doi:10.3390/APP14062421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Becker K, Nobre H, Kanabar V. Monitoring and protecting company and brand reputation on social networks: when sites are not enough. Glob Bus Econ Rev. 2013;15(2–3):293–308. doi:10.1504/GBER.2013.053075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tang CS, Zimmerman JD, Nelson JI. Managing new product development and supply chain risks: the Boeing 787 case. Supply Chain Forum. 2009 Jan;10(2):74–86. doi:10.1080/16258312.2009.11517219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Laming C, Mason K. Customer experience—an analysis of the concept and its performance in airline brands. Res Transport Busin Manag. 2014 Apr;10(1):15–25. doi:10.1016/j.rtbm.2014.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Farzadnia S, Raeesi Vanani I. Identification of opinion trends using sentiment analysis of airlines passengers’ reviews. J Air Transp Manag. 2022 Aug;103(12):102232. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2022.102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lacic E, Kowald D, Lex E. High enough? Explaining and predicting traveler satisfaction using airline reviews. HT’16-Proceedings of the 27th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media; 2016 Jul; Halifax Nova Scotia, Canada. p. 249–54. doi:10.1145/2914586.2914629 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lucini FR, Tonetto LM, Fogliatto FS, Anzanello MJ. Text mining approach to explore dimensions of airline customer satisfaction using online customer reviews. J Air Transp Manag. 2020 Mar;83(4):101760. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2019.101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Rasool G, Pathania A. Reading between the lines: untwining online user-generated content using sentiment analysis. J Res Interact Mark. 2021;15(3):401–18. doi:10.1108/JRIM-03-2020-0045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Brochado A, Rita P, Oliveira C, Oliveira F. Airline passengers’ perceptions of service quality: themes in online reviews. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2019 Feb;31(2):855–73. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-09-2017-0572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Nam S, Lee HC. A text analytics-based importance performance analysis and its application to airline service. Sustainability. 2019;11(21):6153. doi:10.3390/SU11216153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Law CCH, Zhang Y, Gow J. Airline service quality, customer satisfaction, and repurchase intention: Laotian air passengers’ perspective. Case Stud Transp Policy. 2022 Jun;10(2):741–50. doi:10.1016/J.CSTP.2022.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hong JW, Park SB. The identification of marketing performance using text mining of airline review data. Mob Inf Syst. 2019;2019(1):1–8. doi:10.1155/2019/1790429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ban HJ, Kim HS. Understanding customer experience and satisfaction through airline passengers. Online Rev, Sustain. 2019;11(15):4066. doi:10.3390/SU11154066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Siering M, Deokar AV, Janze C. Disentangling consumer recommendations: explaining and predicting airline recommendations based on online reviews. Decis Support Syst. 2018 Mar;107(12):52–63. doi:10.1016/J.DSS.2018.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Korfiatis N, Stamolampros P, Kourouthanassis P, Sagiadinos V. Measuring service quality from unstructured data: a topic modeling application on airline passengers’ online reviews. Expert Syst Appl. 2019 Feb;116(4):472–86. doi:10.1016/J.ESWA.2018.09.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jain PK, Srivastava G, Lin JCW, Pamula R. Unscrambling customer recommendations: a novel LSTM ensemble approach in airline recommendation prediction using online reviews. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2022 Dec;9(6):1777–84. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2022.3200890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yakut I, Turkoglu T, Yakut F. Understanding customers’ evaluations through mining airline reviews. Int J Data Min Knowl Manag Process. 2015 Dec;5(6):1–11. doi:10.5121/ijdkp.2015.5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Jain PK, Patel A, Kumari S, Pamula R. Predicting airline customers’ recommendations using qualitative and quantitative contents of online reviews. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022 Feb;81(5):6979–94. doi:10.1007/S11042-022-11972-7/METRICS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hasib KM, Towhid NA, Alam MGR. Topic modeling and sentiment analysis using online reviews for bangladesh airlines. In: 2021 IEEE 12th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference, IEMCON 2021; 2021; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 428–34. doi:10.1109/IEMCON53756.2021.9623155 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ahmed AZ, Rodríguez-Díaz M. Significant labels in sentiment analysis of online customer reviews of airlines. Sustainability 2020. 2020 Oct;12(20):8683. doi:10.3390/SU12208683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chatterjee S, Mukherjee S, Datta B. Influence of prior reviews about a firm and its alliance partners on reviewers’ feedback: evidence from the airline industry. J Serv Theory Pract. 2021;31(3):423–49. doi:10.1108/JSTP-06-2020-0139/FULL/XML. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Heidari M, Rafatirad S. Using transfer learning approach to implement convolutional neural network model to recommend airline tickets by using online reviews. In: SMAP 2020-15th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation and Personalization; 2020 Oct; Zakynthos, Greece. doi:10.1109/SMAP49528.2020.9248443 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sezgen E, Mason KJ, Mayer R. Voice of airline passenger: a text mining approach to understand customer satisfaction. J Air Transp Manag. 2019 Jun;77:65–74. doi:10.1016/J.JAIRTRAMAN.2019.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alammary AS. BERT models for Arabic text classification: a systematic review. Appl Sci 2022. 2022 Jun;12(11):5720. doi:10.3390/APP12115720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bello A, Ng SC, Leung MF. A BERT framework to sentiment analysis of tweets. Sensors 2023. 2023 Jan;23(1):506. doi:10.3390/S23010506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Shaw P, Uszkoreit J, Vaswani A. Self-attention with relative position representations. In: NAACL HLT 2018-2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2018 Mar; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 464–8. doi:10.18653/v1/n18-2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: NAACL HLT 2019-2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies-Proceedings of the Conference; 2018 Oct; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

30. Shreyashree S, Sunagar P, Rajarajeswari S, Kanavalli A. A literature review on bidirectional encoder representations from transformers. Lect Notes Netw Syst. 2022;336:305–20. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-6723-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Nugroho KS, Sukmadewa AY, Wuswilahaken Dw H, Bachtiar FA, Yudistira N. BERT fine-tuning for sentiment analysis on indonesian mobile apps reviews. In: ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; 2021 Sep; Malang, Indonesia. p. 258–64. doi:10.1145/3479645.3479679 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Prottasha NJ, Sami AA, Kowsher M, Murad SA, Bairagi AK, Met M, et al. Transfer learning for sentiment analysis using BERT based supervised fine-tuning. Sensors. 2022 May;22(11):4157. doi:10.3390/S22114157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Yu S, Su J, Luo D. Improving BERT-based text classification with auxiliary sentence and domain knowledge. IEEE Access. 2019;7:176600–12. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2953990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Touvron H, Martin L, Stone K, Albert P, Almahairi A, Babaei Y, et al. Llama 2: open foundation and fine-tuned chat models; 2023 Jul [cited 2023 Oct 11]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.09288v2. [Google Scholar]

35. Wu C, Lin W, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Xie W. PMC-LLaMA: towards building open-source language models for medicine; 2023 Apr [cited 2023 Oct 13]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.14454v3. [Google Scholar]

36. Roziere B, Gehring J, Gloeckle F, Sootla S, Gat I, Tan XE, et al. Code Llama: open foundation models for code; 2023 Aug [cited 2023 Oct 13]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.12950v2. [Google Scholar]