Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Collaborative Broadcast Content Recording System Using Distributed Personal Video Recorders

1 Deparment of Computer Engineering, Hongik University, Seoul, 04066, Republic of Korea

2 Deparment of Computer Science, Hanyang University, Seoul, 04763, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Choonhwa Lee. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 2555-2581. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.059682

Received 30 October 2024; Accepted 06 January 2025; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

Personal video recorders (PVRs) have altered the way users consume television (TV) content by allowing users to record programs and watch them at their convenience, overcoming the constraints of live broadcasting. However, standalone PVRs are limited by their individual storage capacities, restricting the number of programs they can store. While online catch-up TV services such as Hulu and Netflix mitigate this limitation by offering on-demand access to broadcast programs shortly after their initial broadcast, they require substantial storage and network resources, leading to significant infrastructural costs for service providers. To address these challenges, we propose a collaborative TV content recording system that leverages distributed PVRs, combining their storage into a virtual shared pool without additional costs. Our system aims to support all concurrent playback requests without service interruption while ensuring program availability comparable to that of local devices. The main contributions of our proposed system are fourfold. First, by sharing storage and upload bandwidth among PVRs, our system significantly expands the overall recording capacity and enables simultaneous recording of multiple programs without the physical constraints of standalone devices. Second, by utilizing erasure coding efficiently, our system reduces the storage space required for each program, allowing more programs to be recorded compared to traditional replication. Third, we propose an adaptive redundancy scheme to control the degree of redundancy of each program based on its evolving playback demand, ensuring high-quality playback by providing sufficient bandwidth for popular programs. Finally, we introduce a contribution-based incentive policy that encourages PVRs to actively participate by contributing resources, while discouraging excessive consumption of the combined storage pool. Through extensive experiments, we demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed collaborative TV program recording system in terms of storage efficiency and performance.Keywords

Recent advances in storage, network, and recording technologies have transformed the way users consume TV content [1–3]. Traditionally, television was a one-directional medium with limited programming choices and rigid schedules. The introduction of personal video recorders (PVRs) dramatically altered this paradigm by enabling viewers to record programs in local storage and watch them whenever they want, thereby overcoming the constraints of live broadcasting [4,5]. This capability is especially beneficial for catching programs that might otherwise be missed due to scheduling conflicts or international events with time zone differences, such as the Olympic Games. Despite these advantages, standalone PVRs have significant limitations. Since each device operates independently with restricted storage capacity for recording programs, it can store only a limited number of programs.

In contrast, cloud-based streaming services like Netflix and Hulu have expanded on-demand viewing options by providing catch-up TV services that make broadcast programs available shortly after their initial broadcast [6–11]. Although these services alleviate the limitations of individual PVRs, they introduce new challenges. Streaming services require massive storage to keep a huge number of programs and substantial network bandwidth to support simultaneous streaming requests across numerous devices. To mitigate these issues, service providers need to deploy large-scale Content Delivery Networks (CDNs). However, it is evident that as the number of users increases, service providers require substantial infrastructural expansions in servers, network bandwidth, and CDN deployment to maintain service quality.

An alternative solution to these challenges can be found in a collaborative peer-to-peer (P2P) system, which can provide high scalability without incurring additional costs [12–16]. By pooling a portion of the storage space of many PVRs into a combined virtual storage, each PVR can access data from this shared storage over the Internet [17–20]. This approach also efficiently reduces storage duplication, unlike standalone PVRs that independently store identical programs. When multiple PVRs record the same program independently, each PVR must allocate storage for the same program. This results in unnecessary data duplication and wasted resources. It is evident that the more popular the program, the greater the amount of storage waste that occurs. However, since a P2P approach allows for shared storage and access, it is not necessary for each device to store an identical program. Thus, if PVRs collaborate to record and play back programs, only a subset of them would need to store the program, significantly increasing storage efficiency.

For this collaborative P2P system to be effective, it must maintain the same level of data availability as standalone PVRs. However, since PVRs often join and leave the system, the high churn rate of PVRs makes it essential to store programs redundantly among multiple PVRs. This ensures that the original program can be obtained even if some PVRs storing the program are not available. Erasure coding [21–23] and replication [24,25] have been commonly used in distributed systems to ensure data availability. In addition to guaranteeing program availability, it is also crucial to ensure that the recording and playback processes remain seamless without quality interruption, even though the number of requests increases. Therefore, the key technical challenge in TV program recording using P2P systems is to support all concurrent playback requests in real time while guaranteeing program availability at a level comparable to that provided by local devices. To address this challenge, we propose a collaborative broadcast program recording system that utilizes distributed PVRs, improving both storage efficiency and performance.

The primary contributions of our proposed system are fourfold: First, by collaborating with other PVRs to share resources, including storage space and upload bandwidth, our system achieves significant advantages over standalone PVRs. Specifically, by using the combined storage pool efficiently, our system significantly expands the overall recording capacity, enabling a substantially larger number of programs to be recorded. Furthermore, this collaborative approach ensures that recording is performed independently, unaffected by the user’s current activity or device status, even when a different channel is being watched or when the devices are turned off. Additionally, since there are no physical constraints, such as the number of tuners, each PVR is capable of recording multiple programs simultaneously.

Second, by efficiently utilizing erasure coding, our system requires less storage space to achieve the same program availability compared to traditional replication, which simply duplicates the original data. As a result, our system can record more programs within the same storage capacity. Additionally, our system further enhances storage utilization by distributing the fragments of recorded programs as evenly as possible across participating PVRs. This is accomplished by prioritizing the PVRs with the most available storage space for storing the encoded fragments. Without this strategy, some PVRs may exhaust storage capacity, while others still have sufficient space available. This imbalance leads to a situation where the system’s overall capacity is exhausted despite resources still being available.

Third, by adapting the degree of redundancy of each recorded program according to its changing playback demands over time, our system accommodates as many playback requests as possible. Our system guarantees the minimum degree of redundancy required to ensure the target availability for each program. However, this degree of redundancy does not necessarily guarantee that all playback requests for popular programs can be supported without quality degradation. To address this, as a program’s popularity increases, we increase the number of fragments encoded through erasure coding based on our established criteria. Conversely, as the popularity of the program decreases, we reduce the number of fragments accordingly. This is feasible because our system stores each fragment on a distinct PVR. As the redundancy degree of a program increases, the number of PVRs storing them also increases, thus increasing the aggregated upload bandwidth available for playback. Therefore, this scheme significantly reduces the chances of having to reject requests for popular programs due to insufficient upload bandwidth.

Fourth, by implementing a contribution-based incentive policy, our system encourages PVRs to actively participate by contributing their resources, while discouraging excessive use of the combined storage pool. The storage space allocated to each PVR for recording programs is determined by not only the amount of storage space it donates but also its overall contribution to the system. This contribution is measured by the amount of upload bandwidth provided for sharing and the efficiency with which the PVR minimizes storage usage for its own recordings. PVRs that donate more storage space and make larger contributions receive higher priority in storage allocation, allowing them to record more programs within the combined storage pool.

Through extensive experiments, we demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed collaborative TV program recording system in terms of storage efficiency and performance. First, we show that our system can significantly reduce the redundancy factor for each program, compared to using replication, by utilizing erasure coding, which requires considerably less storage space to achieve the same level of data availability. Second, we illustrate that our system achieves significant improvement in storage efficiency compared to standalone PVRs, in terms of storage requirement per program and the total number of stored programs in the system, achieved through resource sharing and collaboration among PVRs. Finally, we reveal that our adaptive redundancy scheme outperforms a static redundancy scheme in terms of the ratios of continuous playback sessions relative to all requests by controlling the degree of redundancy of each program according to its current playback demand.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the work related to TV content recording systems. Section 3 details the structure and functionalities of our proposed system, which provides TV recording services through collaboration among PVRs. Section 4 presents the experimental results of our proposed system in comparison to standalone PVRs and a static redundancy scheme. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

In recent years, it is becoming difficult to assume that many people watch TV content at the time that it is broadcast [26,27]. This shift in viewing habits is largely due to the emergence of new distribution channels such as streaming through broadband networks and an increasingly diverse range of devices including TV sets, set-top boxes, PCs, mobile phones, tablets, and game consoles where broadcast programs are being consumed. These evolving consumption trends of broadcast TV content can be summarized as accessing any content anytime, anywhere, and on any device. The rapid evolution of broadcast technologies has transformed content consumption, with advanced systems like ATSC 3.0 that enable hybrid broadcast-broadband delivery [28], innovative caching mechanisms that improve multimedia access [29], and intelligent recommendation systems that personalize viewer experiences [30]. These technological developments have expanded content accessibility across multiple platforms. The advent of PVRs marked the beginning of a significant shift, enabling users to overcome the live broadcasting constraints by allowing them to record and watch TV programs at their convenience [4,5]. However, they operate independently and have restricted storage capacities, which limits the number of programs that can be recorded on a single device. Subsequently, online TV streaming services have gained popularity, providing over-the-top(OTT) services that distribute TV programs via the public Internet without requiring a dedicated network [6–11]. These platforms effectively address the limitations of standalone PVRs by offering catch-up TV services, allowing viewers to access previously broadcast programs on demand. Several studies have focused on developing efficient caching and delivery algorithms for catch-up and time-shifting services, with the aim of optimizing content distribution and user experience [31–39]. However, to support a large number of concurrent playback requests without compromising quality, servers must provide considerable network bandwidth and extensive storage for broadcast programs.

To address the challenges of the growing demands of network traffic and storage demands driven by the increasing popularity of OTT services, Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) have been employed to place proxy servers close to user devices, providing a robust, globally distributed infrastructure essential for reliable video delivery. While recent studies have made progress in improving performance [40,41], they still rely heavily on centralized infrastructures. As the demand for OTT services increases, continuous investment in infrastructure expansion is required. From a cost perspective, it is essential to alleviate the burden caused by these substantial investments in service expansion. Addressing this issue remains crucial for achieving cost-effective, scalable services on a large scale. As a result, several systems based on P2P structures have been proposed as alternatives to centralized infrastructures [17–20]. In these systems, PVRs are equipped with broadband interfaces, enabling them to exchange data directly with each other instead of relying on central servers. This allows users to access desired TV programs from neighboring PVRs. Some studies have designed PVR systems specifically designed for mobile devices [42] or for vehicles [43]. However, these studies have primarily concentrated on developing frameworks appropriate for sharing data among PVRs.

On the other hand, despite the inherent nature of PVRs joining and leaving the network freely, P2P systems must still ensure data availability comparable to that of streaming servers. To address the challenges caused by high device churn rates, it is essential that programs are stored redundantly across multiple PVRs. This redundancy ensures that the original data can be reconstructed from the PVRs currently turned on, even if some storing the data are unavailable at a given time. Given the vast amount of programs to be stored, considering storage efficiency is crucial. Erasure coding [21–23] is preferred over replication [24,25] as it requires significantly less storage space to store the same amount of data. However, previous systems have not adequately addressed the storage efficiency of PVRs when recording broadcast programs.

In erasure coding, a file is divided into multiple blocks, with each block split into

3 Proposed Collaborative TV Program Recording System

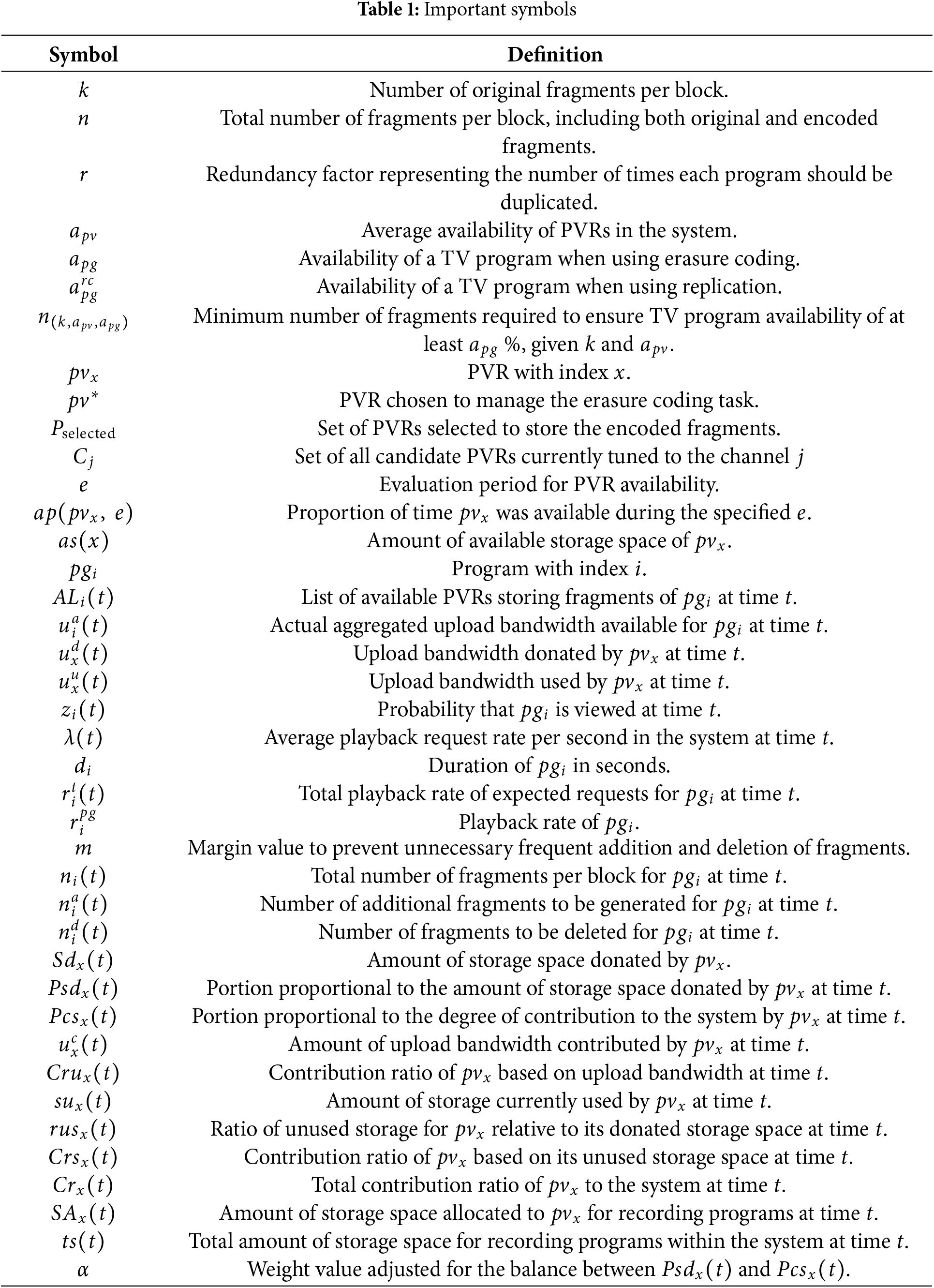

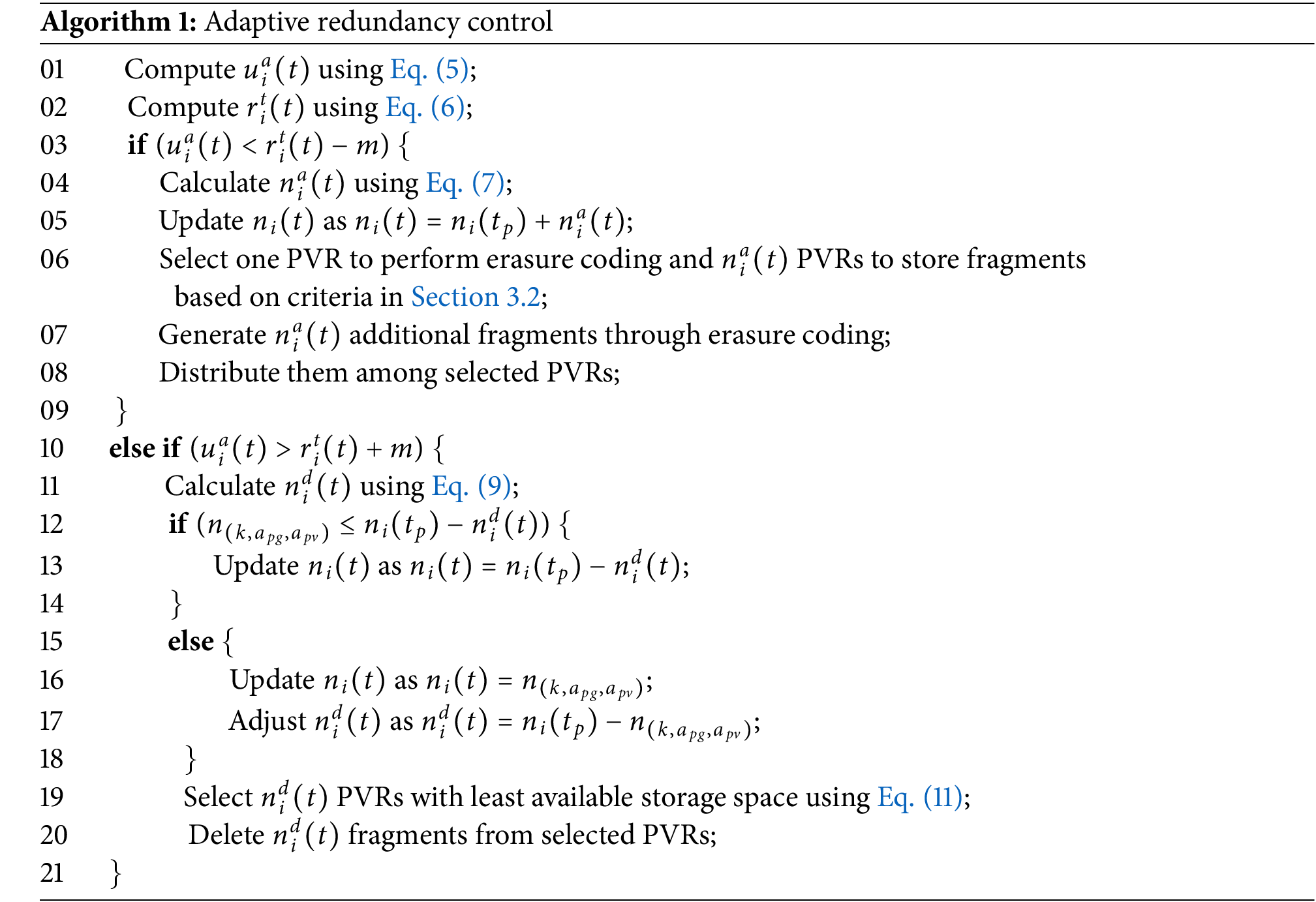

In this section, we introduce a novel TV program recording system that improves storage efficiency and performance through collaborative PVRs. We detail the following: 1) the overall architecture of the proposed system, 2) methods for recording broadcast programs, 3) procedures for playing back recorded programs, 4) strategies for adaptively controlling degree of redundancy to ensure the quality of recorded programs, and 5) a contribution-based incentive policy. Table 1 shows the symbols used in this paper.

Our TV program recording system consists of PVRs, a combined storage pool donated by PVRs for program recording, and a recording manager, as shown in Fig. 1. We assume that PVRs are equipped with tuners, storage devices, and broadband network interfaces. Thus, they can store broadcast TV programs by receiving them directly via tuners and share recorded TV programs with each other over the Internet after donating part of their storage space for recording broadcast programs. When each program to be recorded starts to broadcast, PVRs store fragments assigned by the recording manager in their storage space reserved for program recording. Users can schedule specific programs for recording, play them back, and delete them at any time. When users start to playback a recorded program, the corresponding PVR receives a certain number of fragments for each block from other PVRs redundantly and decodes them. PVRs can join and leave the system at any time.

Figure 1: The overall architecture of our proposed collaborative TV program recording system

The recording manager coordinates the program recording process. It determines which PVR will perform the erasure coding task of each requested program, assigns the encoded fragments of the program among PVRs, and facilitates the sharing of these fragments among PVRs. To do so, it maintains all necessary information for each PVR, such as a list of currently connected PVRs, available storage capacity for program recording, and available upload bandwidth. It also keeps track of the information related to each program, such as the current degree of program redundancy, the program length, the storage locations for each fragment, and the number of playback requests over a specific period. The recording manager periodically collects this information from all PVRs.

The combined storage pool is virtual storage space contributed by all participating PVRs for collaborative recording. To ensure efficient sharing of programs stored in the storage pool, PVRs are interconnected based on mesh-based overlay networks. This network structure allows efficient data transmission and redundancy control by distributing storage and playback loads across multiple PVRs, enhancing performance and scalability. When users request program recording or deletion, the recording manager coordinates the storage of new fragments and the removal of existing ones from the shared storage pool.

It is worth noting that our collaborative system is inherently designed to be resilient to failures and data loss incidents, considering the dynamic nature of distributed PVR participation. Since PVRs can frequently join and leave the system, our system fundamentally assumes and handles partial failures of PVRs storing required data. This resilience is achieved through two primary mechanisms. First, our distributed architecture eliminates single points of failure by storing data across multiple PVRs, ensuring system reliability even when individual PVRs become unavailable. Second, our erasure coding implementation provides built-in data recovery capabilities: when a data block is encoded into

3.2 Recording of Broadcast TV Programs

3.2.1 Utilizing Erasure Coding for Enhanced Storage Efficiency

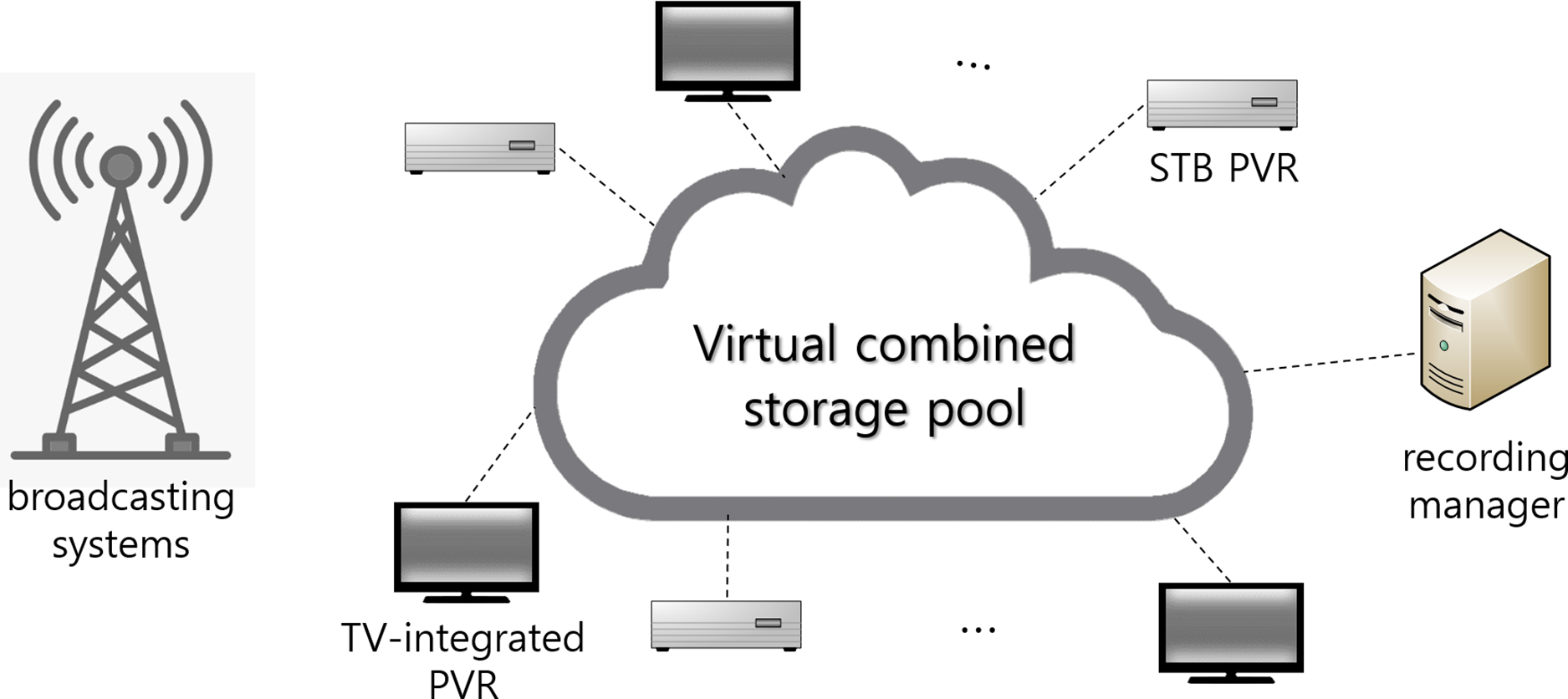

To support all concurrent program playback requests without quality degradation and ensure data availability comparable to that of local storage devices while using less storage space, our system stores all recorded programs by encoding them through erasure coding. As shown in Fig. 2, a recorded program is divided into multiple fixed-length blocks, denoted as

Figure 2: Erasure coding process for storing and distributing a recorded program

Assuming that the redundancy factor,

To further refine our model, we can redefine

In contrast to erasure coding, when replicating the original block, at least one out of the

We will demonstrate through experiments in Section 4.1 that the redundancy degree required for

On the other hand, as the value of

3.2.2 Selecting PVRs for Erasure Coding and Fragment Storage

In our system, users can request to record desired programs. The recording manager evaluates the number of scheduled recording requests for a specific program before the program starts. If the number of those requests is less than the redundancy factor

Once the recording manager decides to use erasure coding to record a program, it must identify a PVR to manage the erasure coding task for the program, and

This expected availability is calculated based on the proportion of time each PVR has been available during a specific preceding period. Assuming that the program to be recorded is scheduled to be broadcast on channel

where

The recording manager also decides which PVRs will store the encoded fragments. Unlike the selection process for the PVR responsible for the erasure coding task, which is based on PVR availability, the recording manager chooses the

where

3.3 Playback of Recorded Programs

To playback a recorded program, a requesting PVR must retrieve the original data by reconstructing each block through erasure coding. This process requires the PVR to receive at least

When a PVR initiates a request to playback a recorded program, the recording manager provides it with a list of source PVRs. The requesting PVR then sends requests to these source PVRs and receives the necessary fragments simultaneously. This concurrent retrieval process significantly reduces the delay in reconstructing the original data. As a result, our system ensures seamless playback of recorded programs in the face of PVR unavailability or network fluctuations.

3.4 Adaptive Redundancy Control to Ensure Playback Quality

There are typically significant differences in the number of playback requests among recorded programs based on their popularity. The playback quality of a popular program may not be guaranteed if the number of PVRs that store its fragments is not sufficient to accommodate all playback requests. While the previously described value of

To maximize the utilization of aggregated upload bandwidth, our system dynamically adapts the degree of redundancy of each program to meet changing playback demands over time. This is achieved by adding new fragments or deleting exsiting fragments for each block as needed. Each fragment is stored on a distinct PVR, ensuring that the number of PVRs used corresponds exactly to the total number of fragments. Consequently, as the redundancy degree of a program increases (i.e., as the number of fragments per block increases), the number of PVRs storing them also increases, thus increasing the aggregated upload bandwidth available for playback. Specifically, if the total playback rate of the expected number of requests for the program during a subsequent period exceeds the aggregated upload bandwidth provided by the currently available PVRs among the

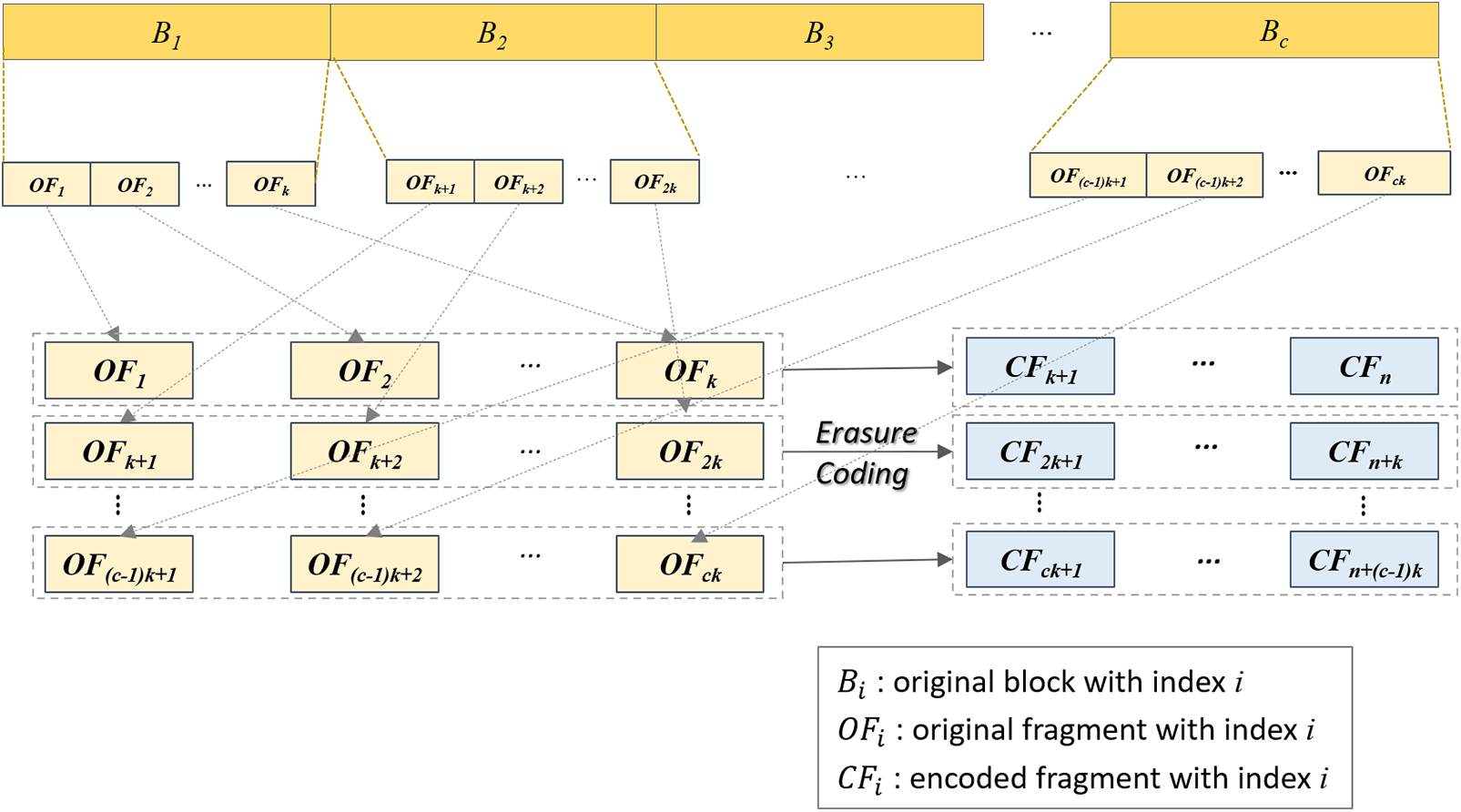

The Algorithm 1 for our adaptive redundancy scheme outlines how our system adjusts the redundancy degree of a program based on changing playback demands, either by adding or deleting fragments as necessary. First, our system measures the actual aggregated upload bandwidth available in the system for each program at time

where

Next, our system calculates the total playback rate of the expected requests for

where

When the number of requests for

Here,

The recording manager is also responsible for selecting the PVR to perform erasure coding to generate these additional fragments for

Conversely, if

It is noted that

In other words, if

The

Our system incorporates a feedback mechanism to dynamically determine the degree of redundancy of each program based on changing playback demands over time. First, the recording manager periodically gathers playback request data at predefined intervals, assessing the popularity of each program. Second, if the playback request rate for a program exceeds predefined thresholds, the system proactively increases its redundancy by generating additional fragments, which are then distributed across more PVRs. Third, as the spike for a program subsides, the system reduces its redundancy degree to reclaim storage space for other programs. While this feedback mechanism effectively addresses most changes in program popularity, rare cases of sudden, significant demand spikes may lead to temporary playback interruptions while the system recalibrates its resources. To address such scenarios, integrating the system with OTT streaming servers could provide additional scalability and reliability.

3.5 Contribution-Based Incentive Policy

To encourage active participation of PVRs in terms of sharing their resources while discouraging excessive storage use that could rapidly deplete the combined storage space, our system employs a contribution-based incentive policy. The amount of storage space allocated to each PVR for recording programs is determined by two factors: one proportional to the amount of storage space it donated and the other proportional to its degree of contribution to the system.

The portion proportional to the amount of storage space donated by

where

In addition, the proportional portion based on the contribution to the system by

To completely remove a specific program from the system, it must be deleted from all PVRs that requested its recording. Thus, the system needs to encourage users to delete the recorded programs immediately after viewing them. Second, to free up storage space for other users by deleting their existing recordings and prevent individual PVRs from holding onto recorded programs for too long, the system also rewards PVRs based on the amount of storage they do not use relative to

Consequently, the total contribution ratio of

Finally, the amount of storage space allocated to each PVR for recording programs at time

where

The incentive policy is implemented through a systematic exchange of information between the recording manager and PVRs. When a PVR joins the system, it registers by sending its donated storage capacity. Subsequently, at predefined intervals, each PVR sends a status message including current upload bandwidth utilization and storage space usage. The recording manager maintains a record of these contributions and calculates storage allocations using Eqs. (12)–(14). When

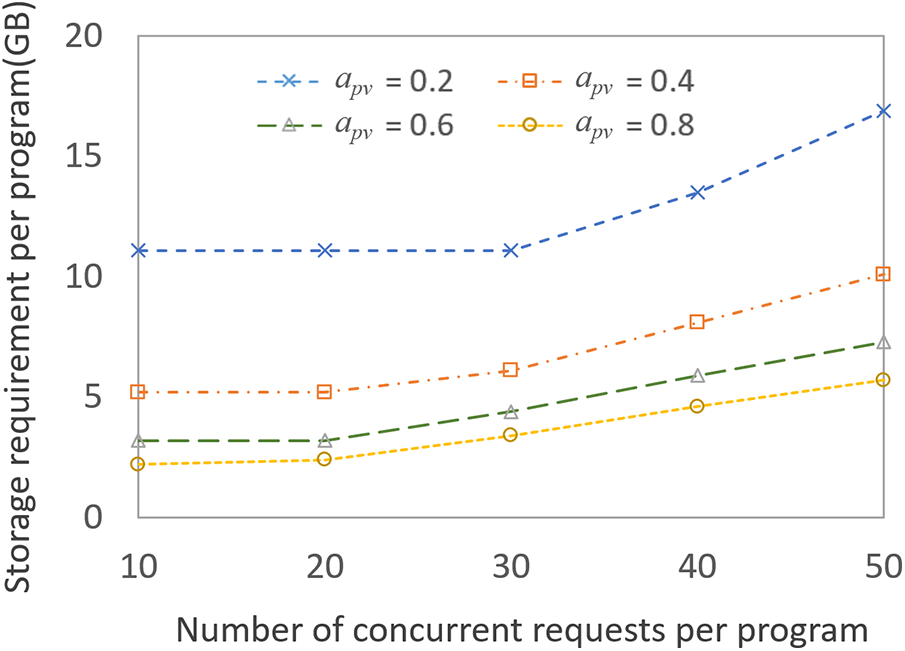

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed collaborative TV content recording system, we conducted extensive simulations with different parameter configurations using the PeerSim P2P simulator. PeerSim is a highly scalable, modular, and event-driven simulation framework specifically designed for peer-to-peer protocols. We utilized the event-based engine of PeerSim to accurately model network dynamics and peer interactions. PeerSim’s modular architecture allows for the implementation of custom protocols and network configurations through its APIs. These features make PeerSim particularly suitable for evaluating large-scale distributed systems like our proposed collaborative TV content recording system. The default simulation parameters used throughout this section are listed in Table 2 unless otherwise indicated.

We performed ten simulation runs, with each simulation lasting 10 h to ensure the consistency and reliability of our results. The number of participating PVRs was set to 3000. Each PVR donated 5 Mbps of upload bandwidth, reflecting typical residential broadband capabilities, and 5 GB of storage space. We simulated 50 channels, with each program lasting 1 h. The playback rate of each program was set at 3 Mbps to match typical HD video streaming requirements, with a block size of 375 KB, corresponding to 1 s of playback. The number of original fragments per block (

Since precise popularity distributions for TV programs are not well established in the literature, we assumed that the popularity of each program follows a Zipf distribution with a parameter of 0.5. We set the average inter-arrival rate for all recording and playback requests at 0.3 requests/s. The request rate for each program at the start of its broadcast was determined by multiplying the average inter-arrival rate of all requests by its proportion among total playback requests, based on the Zipf distribution during each hour. The temporal distribution of users’ playback requests was modeled based on observed TV viewing patterns, notably peaking one hour after broadcast time, accounting for 20% of total requests, followed by a gradual 10% hourly decline. The inter-arrival and inter-departure times for each PVR followed a Poisson distribution with means of 400 and 600 s, respectively, which implies an average PVR availability of 0.4. These parameters were carefully calibrated to represent realistic user session patterns. To incorporate realistic viewing behaviors, we also assumed that users might switch channels randomly after viewing part of a program.

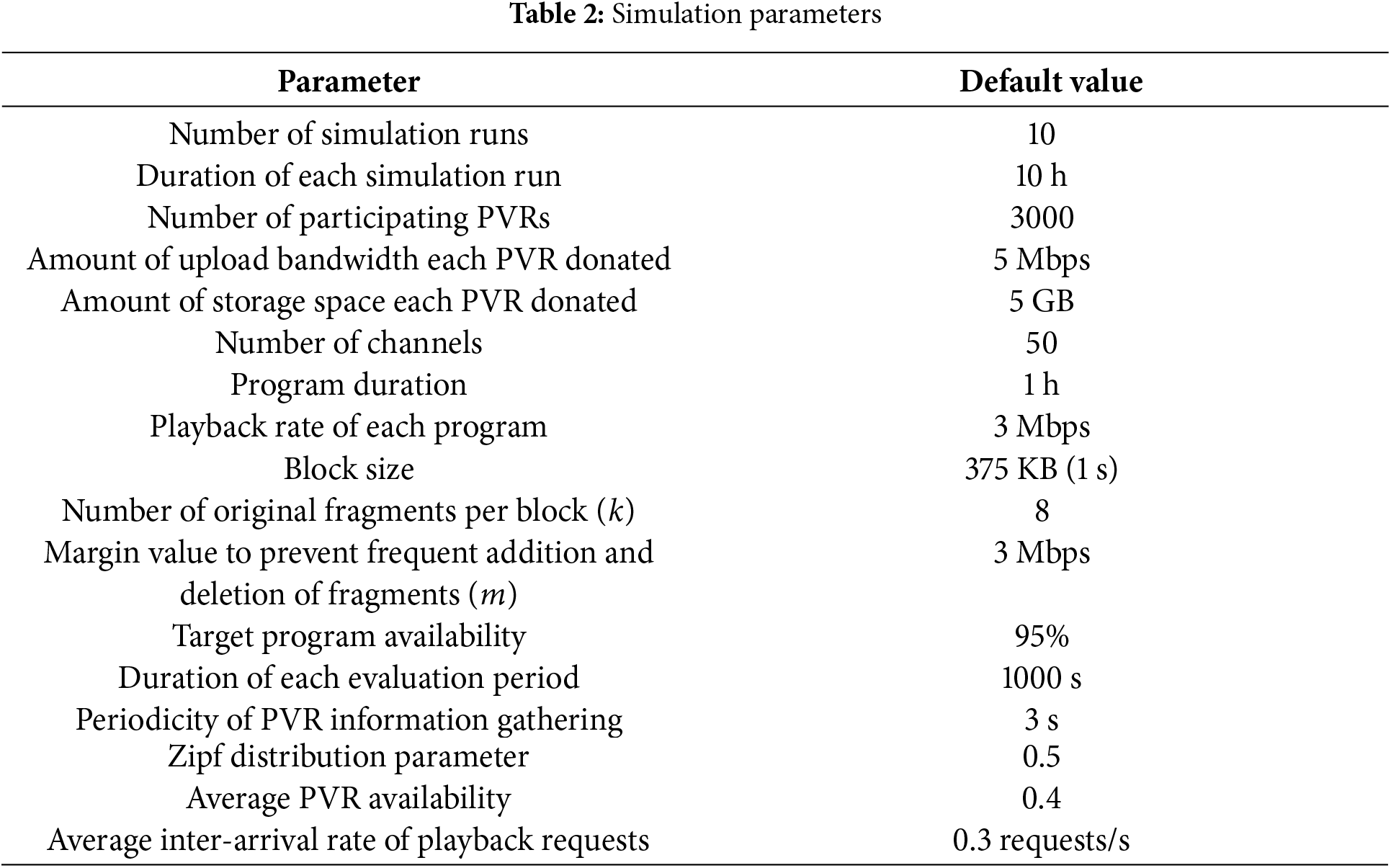

In each simulation, we varied one or two parameters while keeping the others fixed to clearly assess the impact of specific parameters by minimizing interference from other factors during performance evaluation. In the next subsection, to demonstrate the impact of employing erasure coding on the redundancy degree for each program compared to using traditional replication, we analyze the redundancy factors required by both methods to achieve the same target program availabilities. This comparison was conducted while varying PVR availability from 0.2 to 0.8. To illustrate the effectiveness of our proposed collaborative recording system from the perspective of storage efficiency, we also compare our system with standalone PVRs in terms of the amount of storage space required per program. In these experiments, we also varied the number of concurrent playback requests per program during a peak time from 10 to 50. We then examine the impact of our collaborative recording scheme on the total number of stored programs within the system compared to standalone PVRs. To observe the effect of our adaptive redundancy scheme in adapting to the changing playback demand of each program, we also compare it with a static redundancy scheme while varying the Zipf parameter for different

4.1 Impact of Utilizing Erasure Coding on Redundancy Factors

Fig. 3 shows the redundancy factors (

Figure 3: Redundancy factors required by erasure coding (EC) and replication (RC) according to PVR availability (

The results also demonstrate that the superiority of EC over RC becomes increasingly significant as

The results indicate that EC becomes increasingly advantageous as

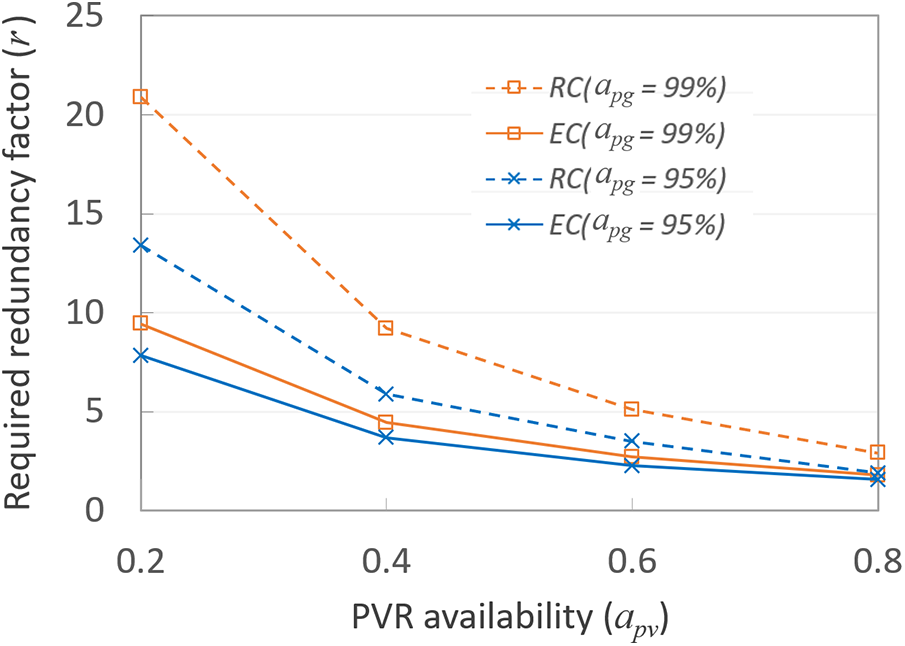

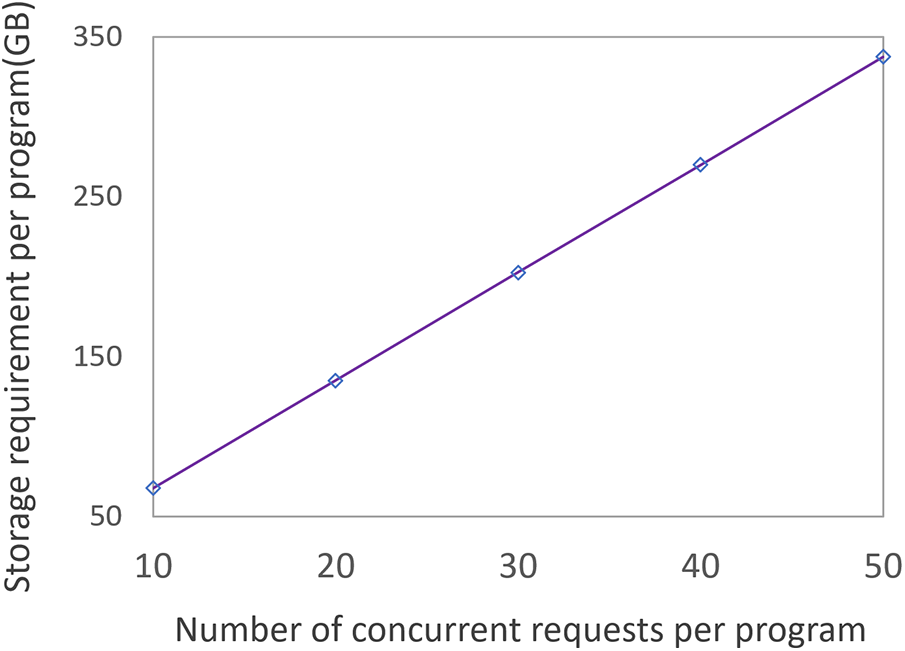

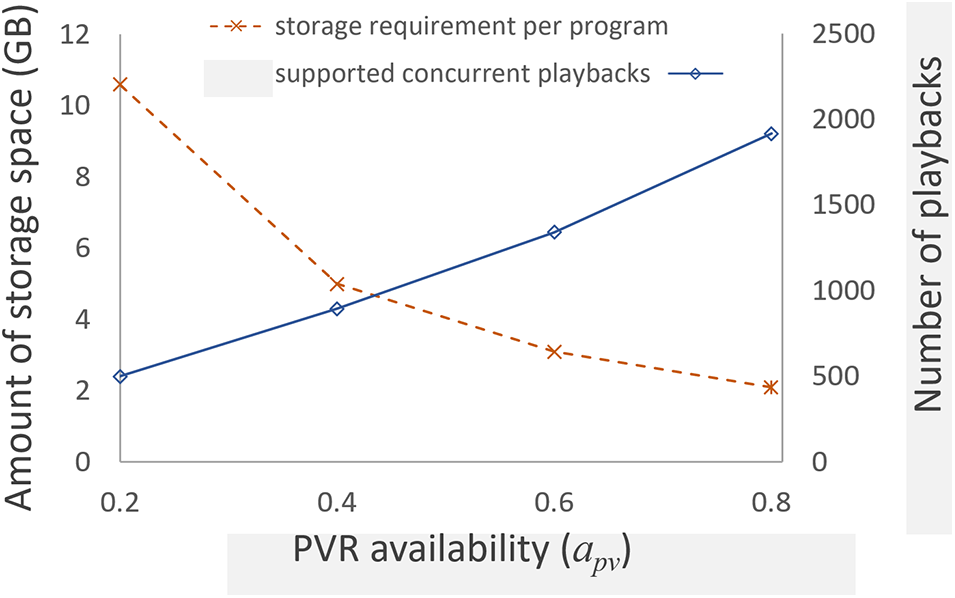

4.2 Impact of Collaborative Recording on Storage Requirements Per Program

Figs. 4 and 5 illustrate the significant improvement in storage efficiency achieved by our collaborative recording system compared to standalone PVRs. The linear increase in storage requirements observed in standalone PVRs, as shown in Fig. 4, highlights a fundamental limitation of independent recording systems. In such systems, each PVR independently stores duplicates of each program, leading to significant storage redundancy across PVRs. In contrast, Fig. 5 demonstrates how our collaborative system efficiently overcomes this limitation by sharing resources and managing them efficiently. Consequently, our system requires significantly less storage space to support all playback requests without quality disruption across all values of PVR availability (

Figure 4: Amount of storage space required per program in standalnoe PVRs

Figure 5: Amount of storage space required per program according to the number of peak-time requests per program for different PVR availabilities (

We can also see from Fig. 5 that in our system, the storage space required per program increases as the number of concurrent playback requests gets larger. The average storage space for all values of

As expected, we have observed that lower PVR availability (

4.3 Effect of Our System on Total Number of Stored Programs

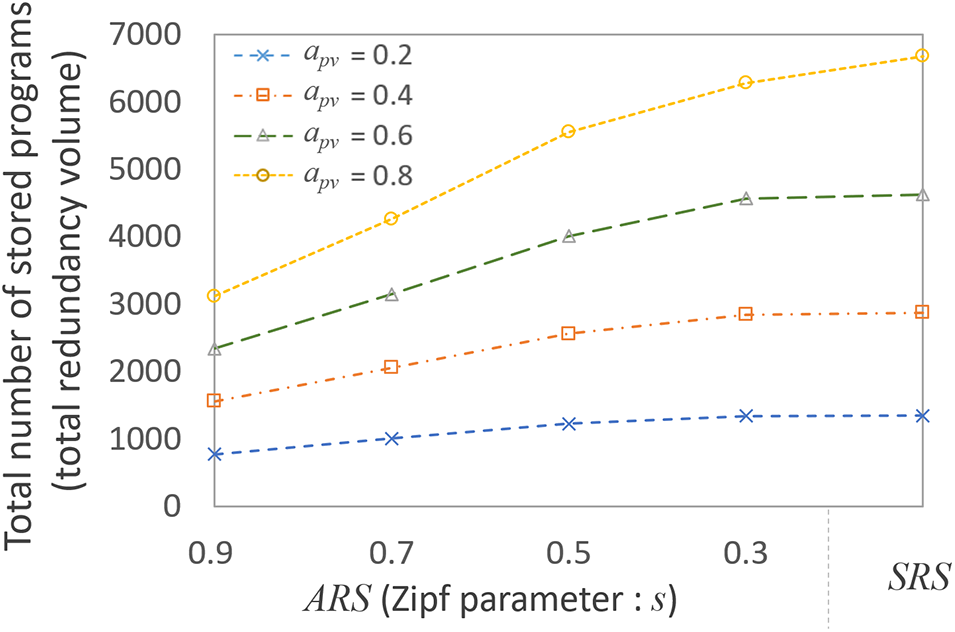

Fig. 6 illustrates the total number of stored programs for different

Figure 6: Total number of stored programs for different

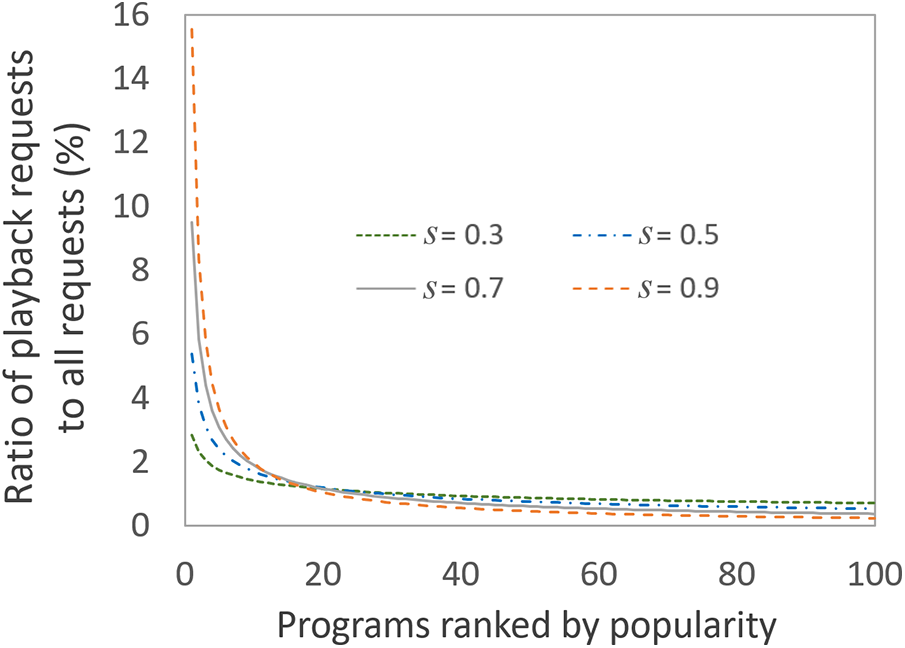

Furthermore, to examine the impact of ARS on the total number of stored programs, we conducted experiments with

Figure 7: Ratio of playback requests to total requests for 100 programs ranked by popularity

We observed that as the

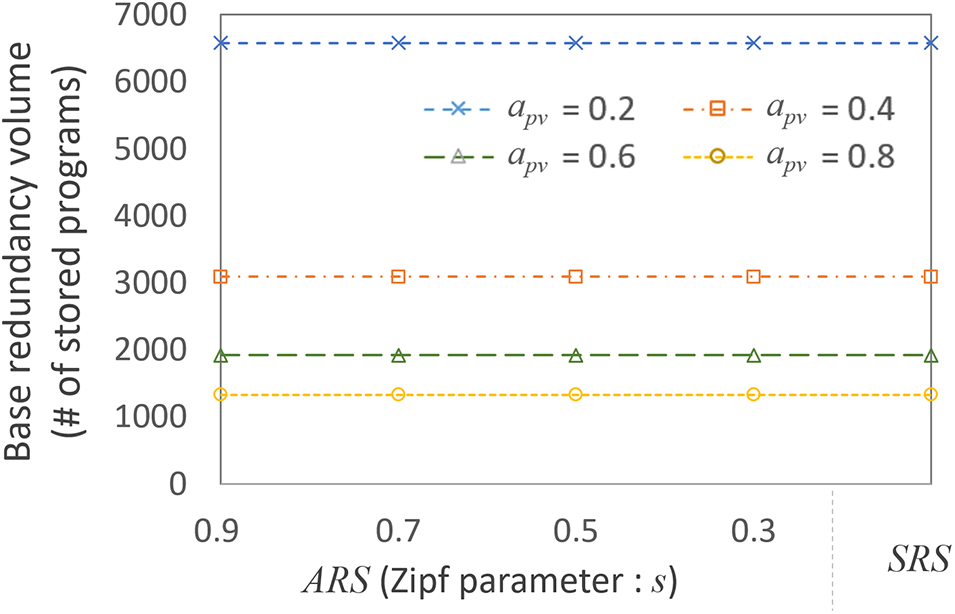

Figure 8: Base redundancy volume for different

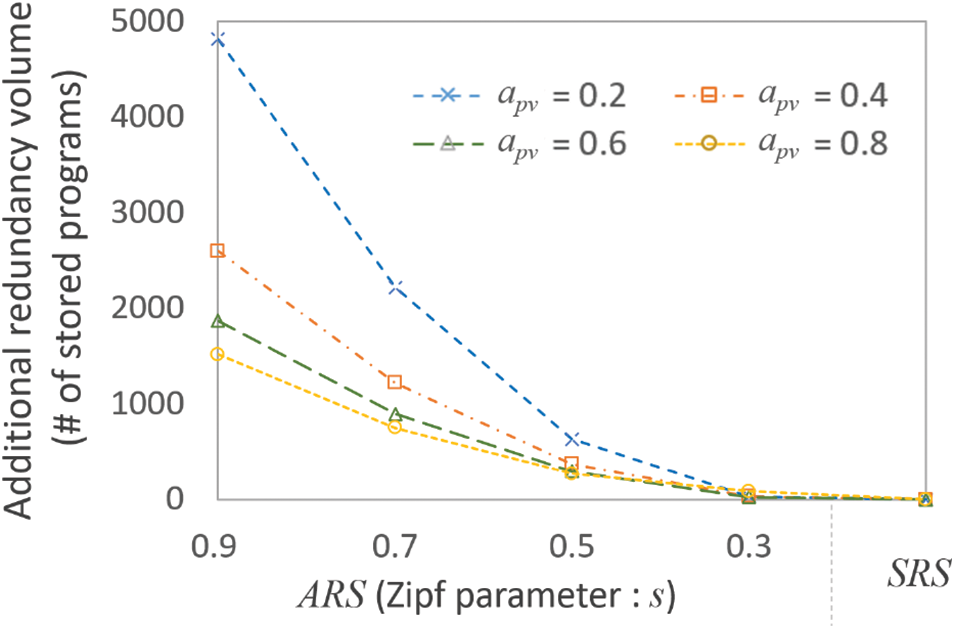

Figure 9: Additional redundancy volume for different

We can also see that when

As expected, when

4.4 Impact of Adaptive Redundancy Control on Playback Continuity

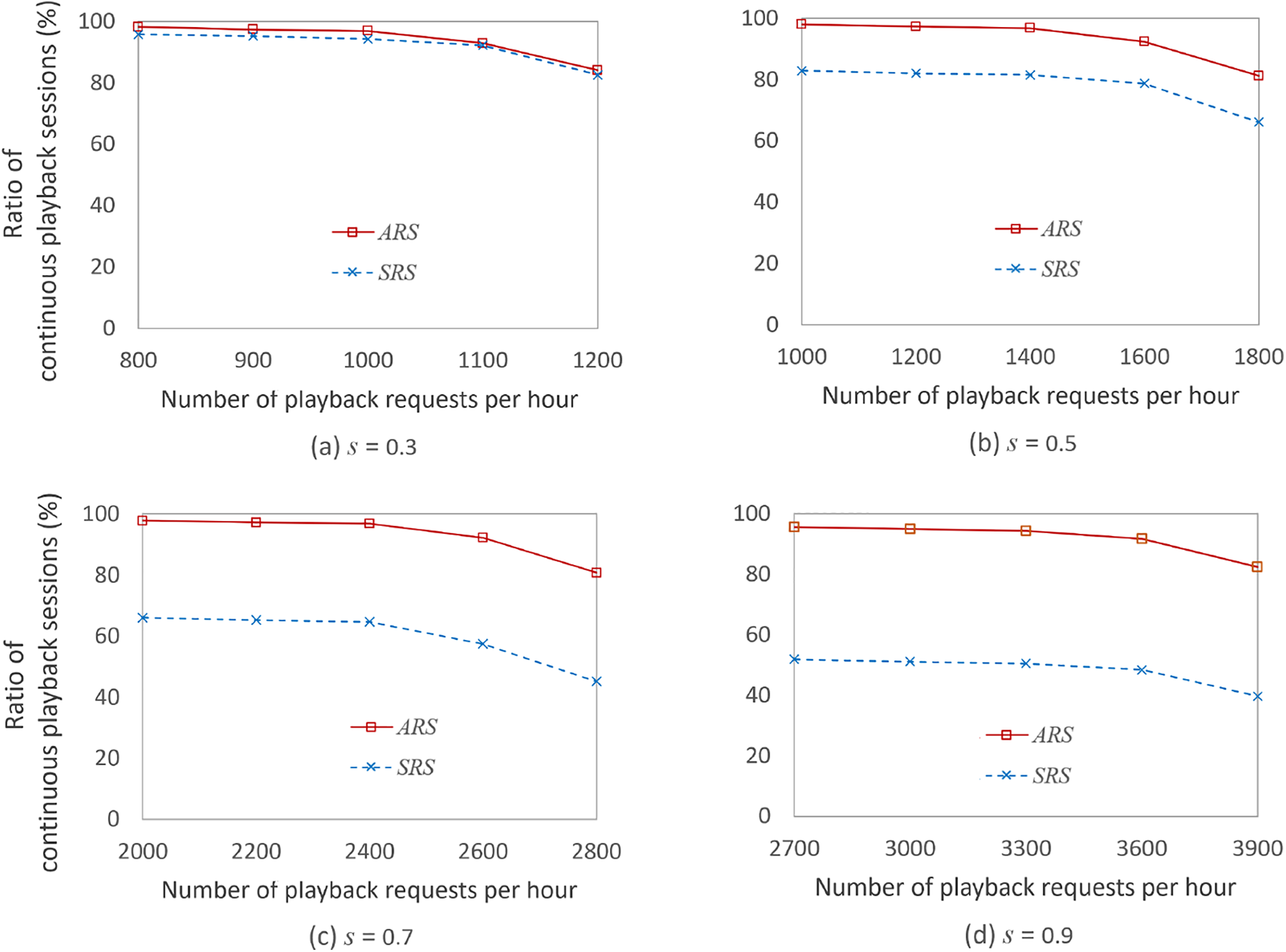

Fig. 10a–d illustrates the ratios of continuous playback sessions–defined as those maintaining over 95% playback continuity–relative to all requests. These figures compare the performance of ARS and SRS across different Zipf distribution parameters

Figure 10: Ratios of continuous playback sessions relative to all requests in ARS and SRS for different Zipf parameters

In Fig. 10a–d, ARS outperformed SRS by an average of 1.8%, 14.9%, 33.3% and 43. 5% in terms of the ratio of continuous playback sessions

4.5 Effect of Varying

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine how variations in

Figure 11: Storage requirement per program and the number of supported concurrent playbacks according to varying

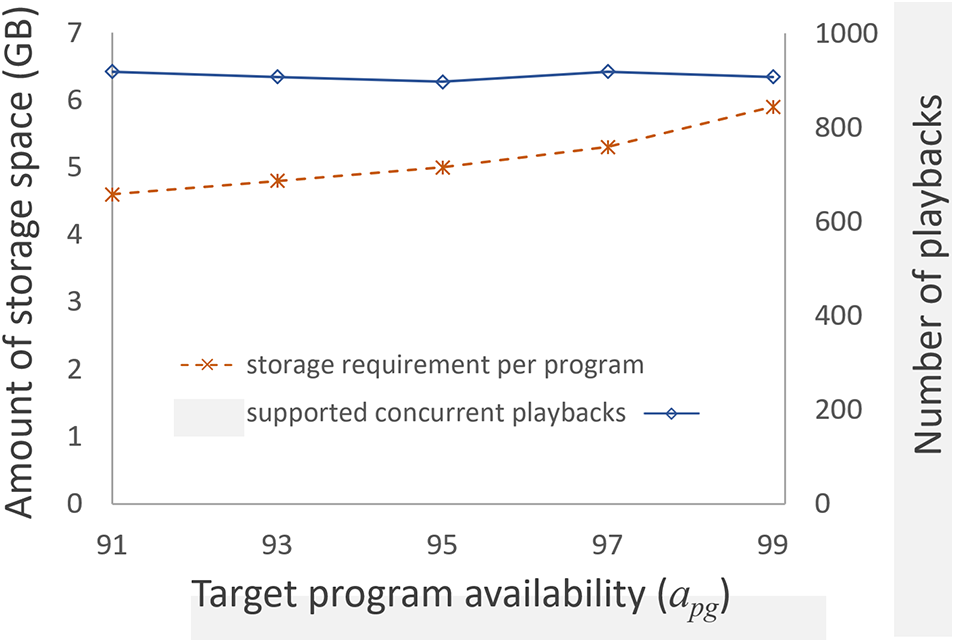

We also examined the impact of varying

Figure 12: Storage requirement per program and the number of supported concurrent playbacks according to varying

In this paper, we proposed a collaborative TV content recording system that addresses the limitations of standalone PVRs and on-line catch-up TV by leveraging the combined resources such as storage and upload bandwidth of distributed PVRs without additional costs. By pooling these resources into a virtual shared storage pool, our system increases storage efficiency for program recording and accommodates as many playback requests as possible while maintaining high-quality streaming performance.

Our system considerably expands recording capacity through efficient resource sharing among PVRs, enabling the recording of a much larger number of programs. This collaboration also allows for simultaneous recording of multiple programs regardless of the user’s current activity or device status. By employing erasure coding, our system minimizes the required storage space per program while maintaining high data availability. Additionally, we introduced an adaptive redundancy scheme that dynamically controls the degree of redundancy based on each program’s playback demand, ensuring high-quality playback for popular programs. We also implemented a contribution-based incentive policy, which rewards PVRs that actively donate resources and promote fair use of the shared storage pool.

Our experiments demonstrated that our system not only surpasses standalone PVRs in terms of storage efficiency and capacity but also outperforms static redundancy schemes in terms of ratios of continuous playback sessions. As online streaming and catch-up TV services continue to increase in popularity, our proposed collaborative recording system has the potential to play an increasingly important role in supporting scalable high-quality TV content recording and playback.

As future work, we plan to improve the selection criteria for PVRs that manage erasure coding by developing a multi-criteria evaluation framework that incorporates additional factors in addition to availability. Additionally, we plan to refine our incentive policy on user behavior by monitoring actual user responses in real-world system deployments.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the editor, reviewers, and all contributors for their valuable suggestions and efforts that improved this paper.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Nos. 2019R1A2C1002221 and RS-2023-00252186) and Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Nos. 2021-0-00590, RS-2021-II210590, Decentralized High Performance Consensus for Large-Scale Blockchains).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Eunsam Kim, Choonhwa Lee; data collection: Eunsam Kim; analysis and interpretation of results: Eunsam Kim, Choonhwa Lee; draft manuscript preparation: Eunsam Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Leiner DJ, Neuendorf NL. Does streaming TV change our concept of television? J Broadcast Electron Med. 2022;66(1):153–75. doi:10.1080/08838151.2021.2013221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Vanattenhoven J, Geerts D. Broadcast, video-on-demand, and other ways to watch television content: a household perspective. In: Proceedings of ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video; 2015; Brussels, Belgium. p. 73–82. [Google Scholar]

3. Stevens T, Appleby S. Video delivery and challenges: TV, broadcast and over the top. MediaSync: Handbook on Multimedia Synchronization: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 547–64. [Google Scholar]

4. Bae J, Kim D, Kang HI. An efficient personal video recorder system. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation; 2010; Changsha, China. p. 501–4. [Google Scholar]

5. Divakaran A, Otsuka I. A video-browsing-enhanced personal video recorder. In: Proceedings of International Conference of Image Analysis and Processing; 2007; Modena, Italy. p. 137–42. [Google Scholar]

6. Khanna P, Sehgal R, Gupta A, Dubey AM, Srivastava R. Over-the-top (OTT) platforms: a review, synthesis and research directions. Mark Intell Plan. 2024. doi:10.1108/MIP-03-2023-0122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Al-Abbasi AO, Aggarwal V, Ra MR. Multi-tier caching analysis in CDN-based over-the-top video streaming systems. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2019;27(2):835–47. doi:10.1109/TNET.2019.2900434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kumar T, Sharma P, Tanwar J, Alsghier H, Bhushan S, Alhumyani H, et al. Cloud-based video streaming services: trends, challenges, and opportunities. CAAI Trans Intell Technol. 2024;9(2):265–85. doi:10.1049/cit2.12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Timmerer C, Begen AC. Over-the-top content delivery: state of the art and challenges ahead. In: Proceedings of ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2014; Orlando, FL, USA. p. 1231–2. [Google Scholar]

10. Nogueira J, Guardalben L, Cardoso B, Sargento S. Catch-up TV forecasting: enabling next-generation over-the-top multimedia TV services. Multimed Tools Appl. 2018;77:14527–55. doi:10.1007/s11042-017-5043-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Abreu J, Nogueira J, Becker V, Cardoso B. Survey of catch-up TV and other time-shift services: a comprehensive analysis and taxonomy of linear and nonlinear television. Telecommun Syst. 2017;64:57–74. doi:10.1007/s11235-016-0157-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yang H, Liu M, Li B, Dong Z. A P2P network framework for interactive streaming media. Proc Int Conf Intell Human-Mach Syst Cybern. 2019;2:288–92. [Google Scholar]

13. Miguel EC, Silva CM, Coelho FC, Cunha IFS, Campos SVA. Construction and maintenance of P2P overlays for live streaming. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(13):20255–82. doi:10.1007/s11042-021-10604-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ali M, Asghar R, Ullah I, Ahmed A, Noor W, Baber J. Towards intelligent P2P IPTV overlay management through classification of peers. Peer Peer Netw Appl. 2022;15:827–38. [Google Scholar]

15. Iqbal MJ, Ullah I, Ali M, Ahmed A, Noor W, Basit A. Machine learning-based stable P2P IPTV overlay. Comput, Mater Contin. 2022;71(3):5381–97. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.024116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zare S. A program-driven approach joint with pre-buffering and popularity to reduce latency during channel surfing periods in IPTV networks. Multimed Tools Appl. 2018;77:32093–105. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6235-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kim E, Lee C. An on-demand TV service architecture for networked home appliances. IEEE Commun Mag. 2008;46:56–63. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2008.4689208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hecht F, Bocek T, Clegg R, Landa R, Hausheer D, Stiller B. Liveshift: mesh-pull live and time-shifted P2P video streaming. In: Proceedings of IEEE Conference on Local Computer Networks; 2011; Bonn, Germany. p. 315–23. [Google Scholar]

19. Gallo D, Miers C, Coroama V, Carvalho T, Souza V, Karlsson P. A multimedia delivery architecture for IPTV with P2P-based time-shift support. In: Proceedings of IEEE Consumer Communications and Networking Conference; 2009; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

20. Kim E, Kim J, Shin H. Cooperative recording to increase storage efficiency in networked home appliances. IEICE Trans Inf Syst. 2022;105(3):727–31. doi:10.1587/transinf.2021EDL8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li JY, Li B. Demand-aware erasure coding for distributed storage systems. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2018;9(2):532–45. doi:10.1109/TCC.2018.2885306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Qiao Y, Zhang M, Zhou Y, Kong X, Zhang H, Xu M, et al. NetEC: accelerating erasure coding reconstruction with in-network aggregation. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2022;33(10):2571–83. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2022.3145836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhou T, Tian C. Fast erasure coding for data storage: a comprehensive study of the acceleration techniques. ACM Trans Storage. 2020;16(1):1–24. doi:10.1145/337555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Panda S, Naik S. An efficient data replication algorithm for distributed systems. Int J Cloud Appl Comput. 2018;8(3):60–77. doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-5339-8.ch065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Huang Z, Yuan Y, Peng Y. Storage allocation for redundancy scheme in reliability-aware cloud systems. In: Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Communication Software and Networks; 2011; Xi’an, China. p. 275–9. [Google Scholar]

26. Westerlund O. A Concept on the Internet-based Television [M.S. thesis]. KTH Royal Institute of Technology; 2014 [cited 2024 Dec 25]. Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:839253/FULLTEXT01.pdf. [Google Scholar]

27. Qi J, Neumann P, Reimers U. Dynamic broadcast. In: Proceedings of ITG Conference on Electronic Media Technology; 2011; Dortmund, Germany. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

28. Melzer J, Melzer N. Standardizing web TV: adapting ATSC 3.0 for use on any IP network. In: IEEE International Symposium on Broadband Multimedia Systems and Broadcasting; 2024; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

29. Petkovic P, Valeev T, Basicevic I. Enhancing caching efficiency of DSM-CC data carousel BIOP messages for android TV broadcast stack virtual file system. In: Zooming Innovation in Consumer Technologies Conference; 2024. Novi Sad, Serbia. p. 209–12. [Google Scholar]

30. Zhu Y, Li Z, Sun L, Gao L. Lightweight multi-role recommendation system in TV live-streaming. In: IEEE International Symposium on Broadband Multimedia Systems and Broadcasting; 2023; Beijing, China. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

31. Konwar KM, Prakash N, Lynch N, Medard M. A layered architecture for erasure-coded consistent distributed storage. In: Proceedings of ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing; 2017; Washington, DC, USA. p. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

32. Okada H, Shiroma T, Wu C, Yoshinaga T. A color-based cooperative caching strategy for time-shifted live video streaming. In: Proceedings of International Symposium on Computing and Networking Workshops; 2018; Takayama, Japan. p. 119–24. [Google Scholar]

33. Nogueira J, Gonzalez D, Guardalben L, Sargento S. Over-the-top catch-up TV content-aware caching. In: Proceedings of IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communication; 2016; Messina, Italy. p. 1012–7. [Google Scholar]

34. Neumann P, Reimers U. Live and time-shifted content delivery for dynamic broadcast: terminal aspects. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2012;58(1):53–9. doi:10.1109/TCE.2012.6170055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Avramova Z, Vleeschauwer D, Wittevrongel S, Bruneel H. Performance analysis of a caching algorithm for a catch-up television service. Multimed Syst. 2011;17:5–18. doi:10.1007/s00530-010-0201-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hwang IS, Tesi C, Pakpahan AF, Ab-Rahman MS, Liem AT, Rianto A. Software-defined time-shifted IPTV architecture for locality-awareness TWDM-PON. Optik. 2020;207:164179. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.164179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lall S, Sivakumar R. Will they or won’t they?: toward effective prediction of watch behavior for time-shifted edge-caching of netflix series videos. In: Proceedings of ACM/IEEE Symposium on Egde Computing; 2021; San Jose, CA, USA. p. 257–70. [Google Scholar]

38. Li Z, Simon G. Time-shifted TV in content centric networks: the case for cooperative in-network caching. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Communications; 2011; Kyoto, Japan. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

39. Lall S. Time-shifted prefetching and edge-caching of video content: insights, algorithms, and solutions [PhD dissertation]. Georgia Institute of Technology; 2022 [cited 2024 Dec 25]. Available from: https://repository.gatech.edu/entities/publication/d045fae8-1cfb-4e1c-adae-04cf6904f399. [Google Scholar]

40. Al-Abbasi AO, Aggarwal V, Lan T, Xiang Y, Ra MR, Chen YF. FastTrack: minimizing stalls for CDN-based over-the-top video streaming systems. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2021;9(4):1453–66. doi:10.1109/TCC.2019.2920979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Pal R, Sastry N, Obiodu E, Prabhu S, Psounis K. EdgeMart: a sustainable networked OTT economy on the wireless edge for saving multimedia IP bandwidth. ACM Trans Auton Adapt Syst. 2023;18(4). doi:10.1145/3605552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dai J, Xia K, Hua Z, Kou Z. Personal video recorder function based on android platform set-top box. Telkomnika Indonesian J Electr Eng. 2014;12(1):550–57. doi:10.11591/telkomnika.v12i1.3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kim Y, Shin D. Improving file system performance and reliability of car digital video recorders. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2015;61(2):222–9. doi:10.1109/TCE.2015.7150597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li X, Li R, Lee PPC, Hu Y. OpenEC: toward unified and configurable erasure coding management in distributed storage systems. In: Proceedings of USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies; 2019; Boston, MA, USA. p. 331–44. [Google Scholar]

45. Liu C, Wang Q, Chu X, Leung YW, Liu H. ESetStore: an erasure-coded storage system with fast data recovery. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2020;31(9):2001–16. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2020.2983411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Xu L, Lv M, Li Z, Li C, Xu Y. PDL: a data layout towards fast failure recovery for erasure-coded distributed storage systems. In: Proceedings of IEEE INFOCOM-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2020; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 736–45. [Google Scholar]

47. Deng M, Liu F, Zhao M, Chen Z, Xiao N. GFCache: a greedy failure cache considering failure recency and failure frequency for an erasure-coded storage system. Comput Mater Contin. 2019;58(1):153–67. doi:10.32604/cmc.2019.03585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Abebe M, Daudjee K, Glasbergen B, Tian Y. EC-store: bridging the gap between storage and latency in distributed erasure coded systems. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems; 2018. Vienna, Austria. p. 255–66. [Google Scholar]

49. Xu L, Lyu M, Li Z, Li Y, Xu Y. Deterministic data distribution for efficient recovery in erasure-coded storage systems. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2020;31(10):2248–62. [Google Scholar]

50. Mammeri A, Boukerche A, Fang Z. Video streaming over vehicular ad hoc networks using erasure coding. IEEE Syst J. 2016;10(2):785–96. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2015.2455813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang XJ, Peng XH. A testbed of erasure coding on video streaming system over lossy networks. In: International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies; 2007; Sydney, Australia. p. 535–40. [Google Scholar]

52. Toporkov V, Yemelyanov D. Availability-based resources allocation algorithms in distributed computing. In: Supercomputing. Moscow, Russia: Springer; 2020. p. 551–62. [Google Scholar]

53. Leontiadis I, Marzolla M, Datta A, Rieche S, Cilia M. Choosing partners based on availability in P2P networks. In: Proceedings of ACM Conference on Distributed Computing and Networking; 2012; Hong Kong, China. p. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools