Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

An Iterative PRISMA Review of GAN Models for Image Processing, Medical Diagnosis, and Network Security

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Prasad V Potluri Siddhartha Institute of Technology, Vijayawada, 520007, India

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Vaddeswaram, 522302, India

3 Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Sreenidhi Institute of Science and Technology, Hyderabad, 501301, India

4 Amrita School of Computing, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Amaravati, 522503, India

5 Department of Teleinformatics Engineering, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, 60455-970, Brazil

6 Inti International University, Nilai, 71800, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Uddagiri Sirisha. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 1757-1810. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.059715

Received 15 October 2024; Accepted 12 December 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

The growing spectrum of Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) applications in medical imaging, cyber security, data augmentation, and the field of remote sensing tasks necessitate a sharp spike in the criticality of review of Generative Adversarial Networks. Earlier reviews that targeted reviewing certain architecture of the GAN or emphasizing a specific application-oriented area have done so in a narrow spirit and lacked the systematic comparative analysis of the models’ performance metrics. Numerous reviews do not apply standardized frameworks, showing gaps in the efficiency evaluation of GANs, training stability, and suitability for specific tasks. In this work, a systemic review of GAN models using the PRISMA framework is developed in detail to fill the gap by structurally evaluating GAN architectures. A wide variety of GAN models have been discussed in this review, starting from the basic Conditional GAN, Wasserstein GAN, and Deep Convolutional GAN, and have gone down to many specialized models, such as EVAGAN, FCGAN, and SIF-GAN, for different applications across various domains like fault diagnosis, network security, medical imaging, and image segmentation. The PRISMA methodology systematically filters relevant studies by inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure transparency and replicability in the review process. Hence, all models are assessed relative to specific performance metrics such as accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency. There are multiple benefits to using the PRISMA approach in this setup. Not only does this help in finding optimal models suitable for various applications, but it also provides an explicit framework for comparing GAN performance. In addition to this, diverse types of GAN are included to ensure a comprehensive view of the state-of-the-art techniques. This work is essential not only in terms of its result but also because it guides the direction of future research by pinpointing which types of applications require some GAN architectures, works to improve specific task model selection, and points out areas for further research on the development and application of GANs.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileGlossary/Nomenclature/Abbreviations

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| DCGAN | Deep Convolutional GAN |

| WGAN | Wasserstein GAN |

| CGAN | Conditional GAN |

| SAGAN | Self-Attention GAN |

Generative adversarial networks, one of the most transformative developments in machine learning and artificial intelligence since the concept of Goodfellow et al. in 2014, GANs constitute two competing neural networks: a generator that will create synthetic data possibly looking similar to actual data and a discriminator that discriminates between actual and generated samples. These adversarial frameworks have shown immense success in various applications ranging from the computer vision application domain to image synthesis and natural language processing to healthcare. However, as GANs evolve further, the sheer number of variants and models becomes prohibitive for researchers and practitioners looking to choose the optimal architecture for specific tasks. Several GAN architectures were implemented, which included the conditional GAN (CGAN), Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN), and the Wasserstein GAN (WGAN) [1,2], to counter some of the weaknesses inherent in the basic GAN architecture, such as instability during training, mode collapse, and failure to generate high-resolution images [3,4]. Each model improves on one of the weaknesses cited but introduces others simultaneously. For example, WGAN uses the Wasserstein distance metric in its architecture to stabilize the training and handle issues concerning gradient vanishing. At the same time, CGAN adds conditional input to produce better-controlled outputs. Despite their broad application, there is a shortage of comprehensive and systematic comparisons of these models in different domains. Most of the reviews in place are either application-specific to the use case, for example, image generation or anomaly detection, or do not have proper evaluation metrics, which makes it cumbersome to state the various models’ adaptability to different applications. This paper tries to do an iterative review of GAN models using PRISMA to fill the gap in the literature.

The PRISMA approach ensures a transparent, replicable process for systematically identifying and evaluating GAN models according to a well-defined set of criteria. This paper gives an overall view of the performance and applicability of such architectures, coupled with some knowledge about comparing models across different domains, such as CGAN, WGAN, and DCGAN. Each model is discussed in detail regarding its advantages and limitations, along with performance metrics such as accuracy, computational efficiency, and stability in training. Such a detailed comparison is bound to guide researchers and practitioners as to which GAN architecture will be the most suitable for their task. With the widespread expansion of GANs to new applications such as medical image analysis, cybersecurity, fault detection, and data augmentation, there is an ever-growing need for a structured evaluation of such models. This paper addresses the shortcomings of the current reviews using the PRISMA methodology and lays the foundation for future research on task-specific GAN optimization [5].

From GANs to one of the most transformative developments that exist today image, to processing natural language, to diagnosing medical issues, and even to autonomous systems, innovation via GANs in artificial intelligence has come out to be quite remarkable since its inception, when was able to generate realistic data learned from existing datasets. From generating realistic images with good quality to improving medical image segmentation, GANs have made tremendous strides in modeling complex data distributions. However, along with the huge leaps GANs have taken in such a short period, it has resulted in various architectures and methods of implementing these models, one after another, each having its strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, it presents an immense growth in diversity and appeals to a systematic analysis of GAN models concerning identifying optimal architectures for applications [6–8].

Most existing reviews of GANs focus on specific application areas or provide a high-level overview without examining the comparative performance of different models. In such research, most studies do not adopt a structured review process, making it rather difficult to synthesize findings across different fields or assess the generalizability of certain GAN models. However, the lack of structured analysis raises several questions: for example, which GAN variants are more effective for some tasks, where potential improvements need to be found, and where gaps in existing research lie? Effectiveness in GANs often depends on the architecture used, the training stability of the model, and its ability to generalize to unseen data. However, efforts have been made to systematically review and quantify the performance of such models across multiple domains using robust frameworks such as PRISMA, which stands for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

There are several gaping research lacunas in the existing literature. First, how do different architectures of GANs perform across domains in a statistically sound manner? While a huge number of models are available, there are very few comparative studies based on robust performance metrics. Second, is it possible to optimize GANs for data-scarce environments, such as medical imaging or rare event detection, where data availability is a severe bottleneck? Third, are there best practices for dealing with mode collapse and instability, two of the leading problems haunting the development of GAN, especially for big and large-size datasets? Fourth, do GANs work well for multi-modal data fusion? Combining different types of data, for example, using text data combined with images or sound, can further enhance performance in applications like autonomous driving or intelligent surveillance. Thirdly, as the high computational costs of GANs often hinder their practical application in real-time scenarios, which model performance, if any, would result from improving their computational efficiency?

A comprehensive review of GAN models on different broad applications will be proposed in this paper to bridge the gaps. From the comparison of performance metrics, a statistical-in-depth comparison of the usage of different architectures of GANs in terms of signal-to-noise ratio, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores will be reported. This aims to develop a structured, transparent, and replicable assessment of GAN models by applying the PRISMA methodology, filling the current gap in this field of systematic reviews. Method summaries range across several domains, including image synthesis, medical diagnosis, and cybersecurity, to offer a holistic view of how different fields apply GANs.

The rapid proliferation of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) across diverse domains, including image processing, medical diagnostics, cybersecurity, and others, creates a pressing need for systematizing the evaluation of these architectures. This gives rise to a challenge in researcher practice. Determining the right architecture for particular applications is a challenge among the ever-growing number of GAN models, from basic GANs to variants such as Conditional GANs (CGANs) and Wasserstein GANs (WGANs). Most of the existing reviews are insightful but narrow in scope, as they try to focus narrowly on a specific domain or a fixed, non-standardized methodology for systematically evaluating GAN models. This approach unaddressed fundamental issues, such as a lack of understanding concerning training stability, performance under sparse data conditions, and associated computational efficiency. For instance, because the review does not present a comprehensive comparative analysis, it leaves questions on which GAN architectures outperform others in tasks such as high-resolution image synthesis, fault detection, or multimodal data fusions.

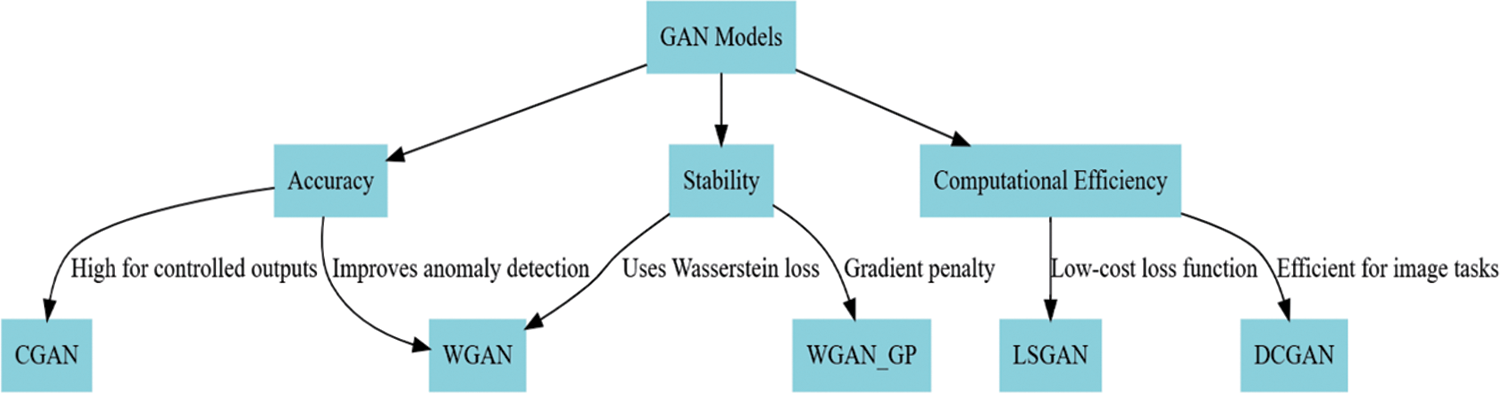

To address these gaps, this review adopts a PRISMA-based framework to systematically evaluate more than 60 GAN architectures in various domains. The study aims to answer critical research questions (Fig. 1): (1) Which GAN architectures perform optimally regarding accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency for specific applications? (2) How can GANs be optimized for data-scarce environments, such as medical imaging and rare event detection? (3) What strategies effectively address persistent issues like mode collapse and training instability in GANs? (4) Can GANs be applied successfully for complex tasks such as data fusion in multiple modes and real-time applications? Addressing these questions systematically allows the review not only to give a comprehensive description of the performance metrics of GANs, but also actionable insights and future research directions that can bridge the gaps in the development and application of GANs.

Figure 1: GAN operations

It synthesizes performance results and identifies the strengths and weaknesses of various GAN models to provide insight into their applicability in different tasks. Systematic comparison of models lets this review provide practical recommendations for researchers and practitioners interested in choosing or designing the most apt GAN architecture. More importantly, it has highlighted areas for future research, such as stabilizing better training of the model, generalization in low-data environments, and incorporation with newly available technologies such as transformers and neural architecture search with GANs.

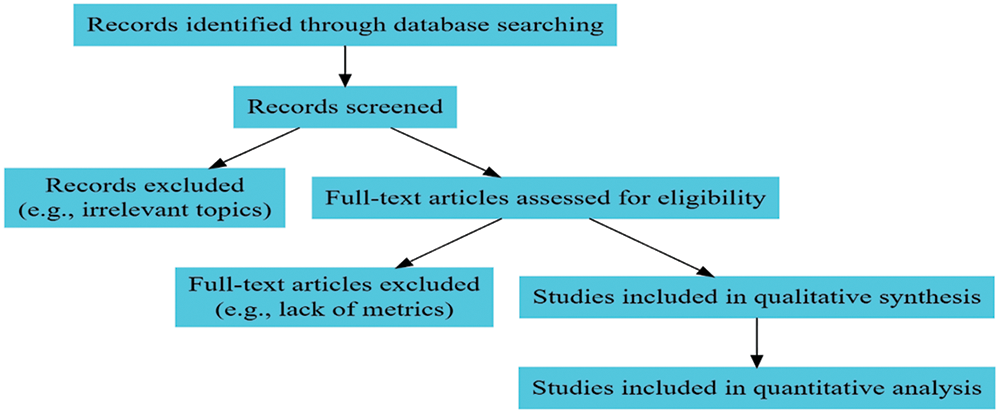

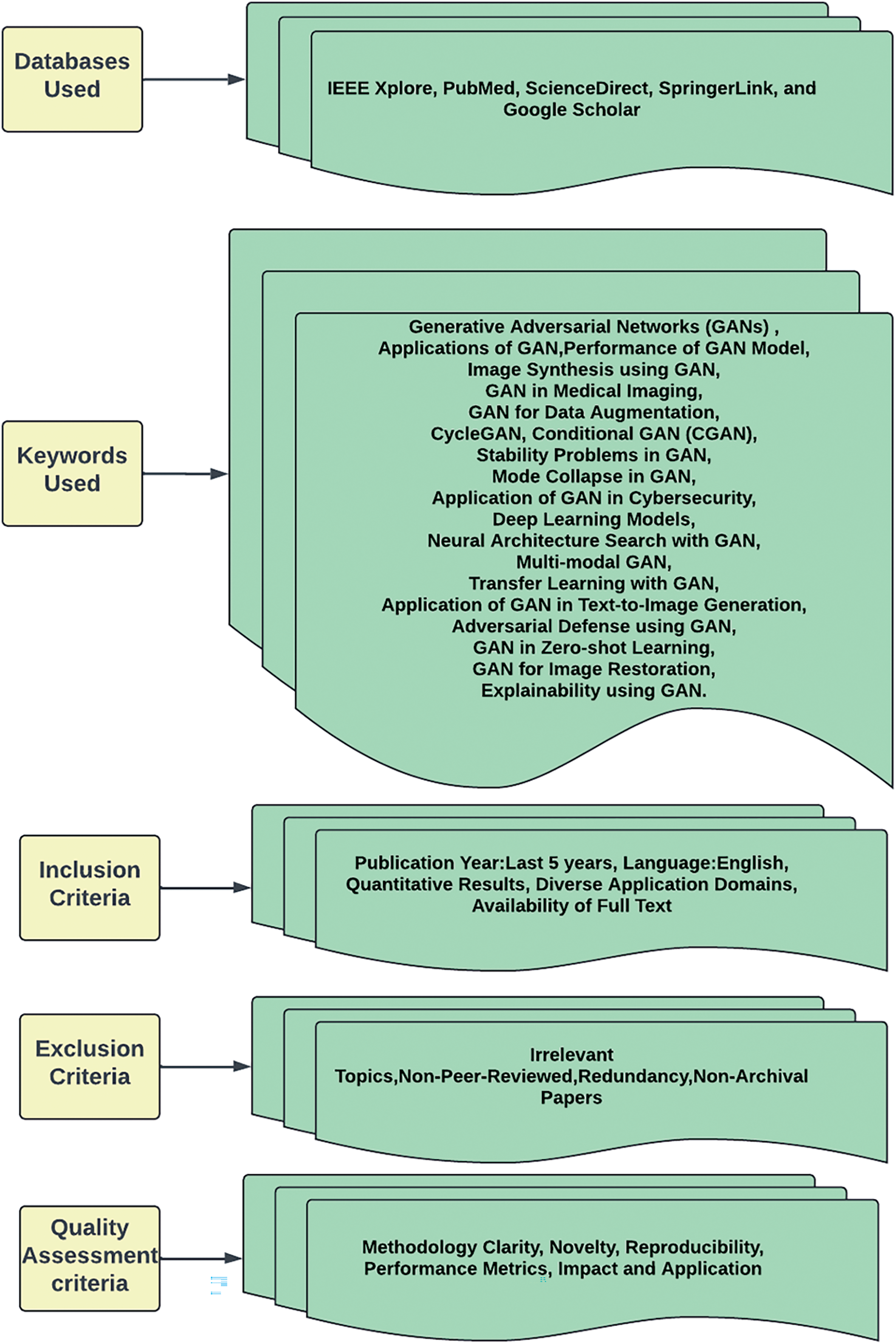

This systematic PRISMA-based review of existing studies was chosen based on a structured selection process to include relevant and highly quality studies. The search process involves several steps, explained below, including defining search keywords, setting inclusion and exclusion criteria, and evaluating the quality of studies based on specific performance metrics. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented below in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Screening process

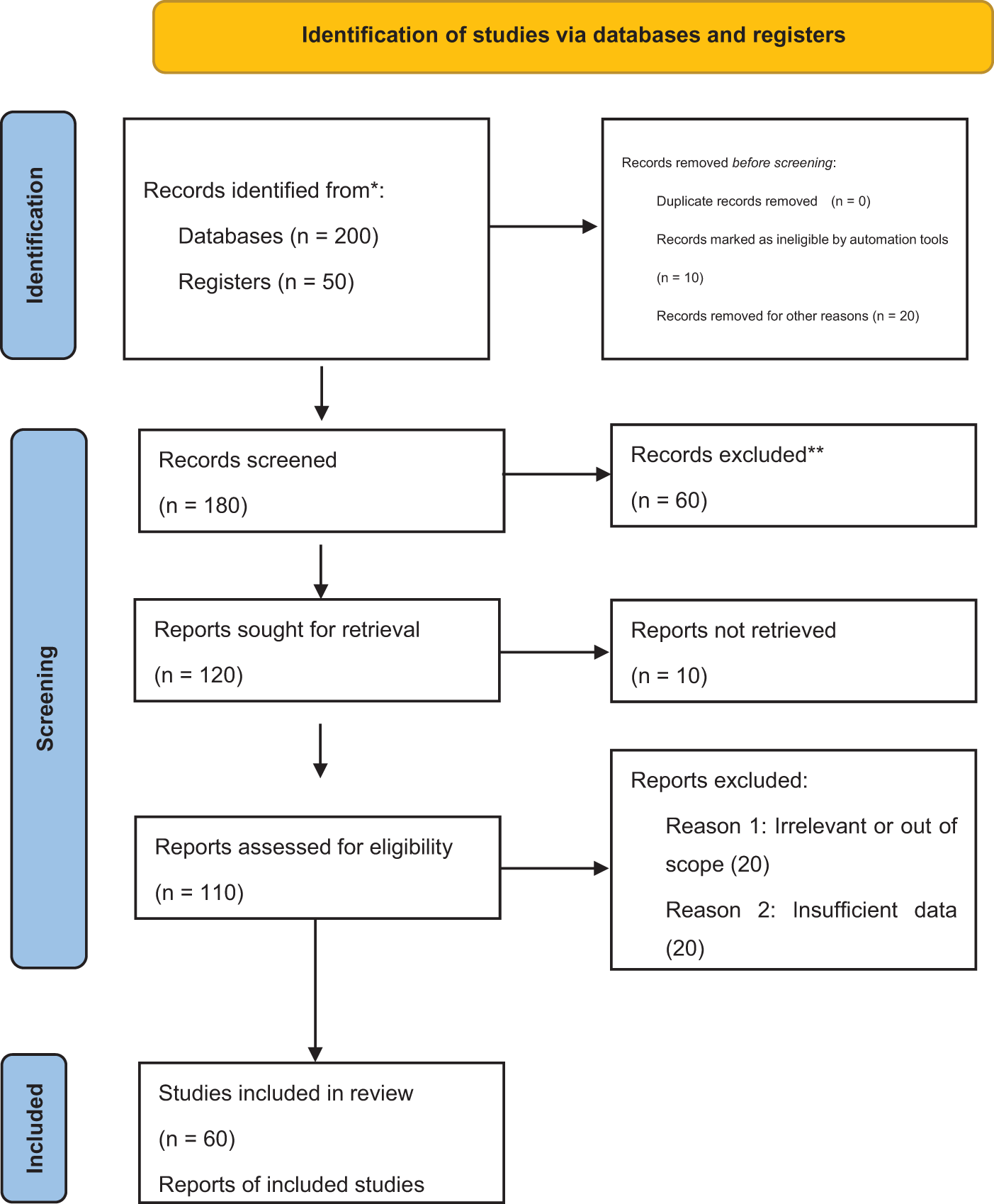

Following the criteria in Figs. 3 and 4, the review focused on selecting only the best quality and relevant studies, which would afford a deep understanding of GAN models’ performance and efficiency in divergent applications.

Figure 3: Overview of studies selection for the survey

Figure 4: Process followed for selection of papers

Medical diagnostics and network security are essential to adopting GANs in critical domains. While medical applications of GANs are vast, including data augmentation, image synthesis, and anomaly detection, the model is only as biased or unbiased as the training data samples. Whenever GANs are trained on datasets biased towards a particular demographic or condition, the synthetic data may unintentionally propagate these biases and even amplify them. For instance, a GAN trained on skin lesion images predominantly by lighter skin tones will fail to generalize well to patients with darker skin tones, potentially resulting in diagnostic or treatment errors. To this end, careful curation of training datasets concerning diversity, fairness, and fairness-aware training methodologies in GAN design is recommended.

In network security applications, GANs will be used for synthetic traffic data generation to build intrusion detection systems or for the construction of adversarial samples for testing system robustness. Such applications have apparent benefits but also some significant ethical concerns. Synthetic data can be used for malicious actions if not utilized rightly, for instance, generating advanced phishing attack patterns or evading security systems. Samples generated with the help of GANs can leak out or misapplied; thus, bad actors can evade detection systems. Strict governance and security practices in developing GAN-based systems in sensitive environments should be emphasized.

Further ethical issues arise at the level of broader implications of GAN technology in use. The public has sensationalized GAN technology regarding its use for deepfakes, synthetic media, etc. Healthcare analogs might be used to fake medical images or records in healthcare systems. Such practices will lead to the untrustworthiness of diagnostic systems. To this end, traceability in GAN workflows and mechanisms for explainability should be stressed for the process. Ethical considerations, such as data privacy, consent, and fairness, should also guide development and deployments. These measures provide a solution for preventing risks concerning proper outcomes and public trust in applications where GANs play a significant role in the process.

This motivation comes from the proliferation of GAN models in many domains and the challenge of selecting the most appropriate architecture for specific applications. The diversity of GAN models varies from basic GAN to advanced variants like CGAN, WGAN, and DCGANs, which present a complex land for researchers and practitioners. Although each of these models offers some new innovative feature to address one limitation, for instance, instability or low-resolution output, comprehensive study and comparison of these models against other performance metrics is conspicuous by its absence. The existing reviews are narrow and focus on specific applications, or they do not have transparent and systematic frameworks to analyze the individual models in detail. This leads to a problem of suboptimal model choice, limiting the adequacy of GANs for real-world applications. To fill this gap, this paper aims to apply the PRISMA review framework for systematically, transparently, and reliably evaluating GAN models across various domains. The contribution of this work is as follows: The first benefit is that it compares the variants of GAN—from CGAN and WGAN to DCGAN—based on the performance metrics of accuracy, stability, computational efficiency, and domain specificity. The second benefit is that it offers action insight into the most suitable models for specific GAN tasks to help further research and application. Taking advantage of this PRISMA framework thus guarantees great rigor and reproducibility so that further research could rely on the critical base presented in this paper. This work discusses the strengths and weaknesses of existing GAN models and informs important areas to be developed, such as achieving stability and scalability for high-resolution data generation.

1.4 Contributions & Structure of Paper

Based on the contributions provided, here are four objectives framed for the paper:

1. To conduct a structured review of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) applicable in various fields such as image processing, medical diagnosis, and network security, using PRISMA-based guidelines for rigorous and comprehensive analysis.

2. To perform a detailed comparative analysis of over 60 GAN models using statistical evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, and SNR, identifying task-dependent performance improvements across diverse application areas.

3. To determine the most efficient and optimal GAN architectures for specific use cases such as medical image classification, fault detection, and image synthesis, focusing on computational efficiency, training stability, and generalization capability.

4. To outline potential research directions for the future, particularly focusing on optimizing GANs for complex tasks like multi-modal data fusion and addressing challenges in data-scarce environments.

The document is organized as follows: The introduction summarizes GANs, discusses the importance of a structured review, and points out shortcomings in previous reviews. This is followed by the motivation and contributions section, which underscores the paper’s main contributions to evaluating GAN models in various fields. The methodology section explains the PRISMA framework, including criteria for inclusion/exclusion and categorization of papers. The statistical review and analysis thoroughly evaluate more than 60 GAN models through statistical measures. Ultimately, the section results and discussion highlight the main discoveries. In contrast, the section conclusion and future scope suggest ways to enhance GAN performance in training stability and handling complex data tasks.

2 Overview of GAN Architectures and Datasets

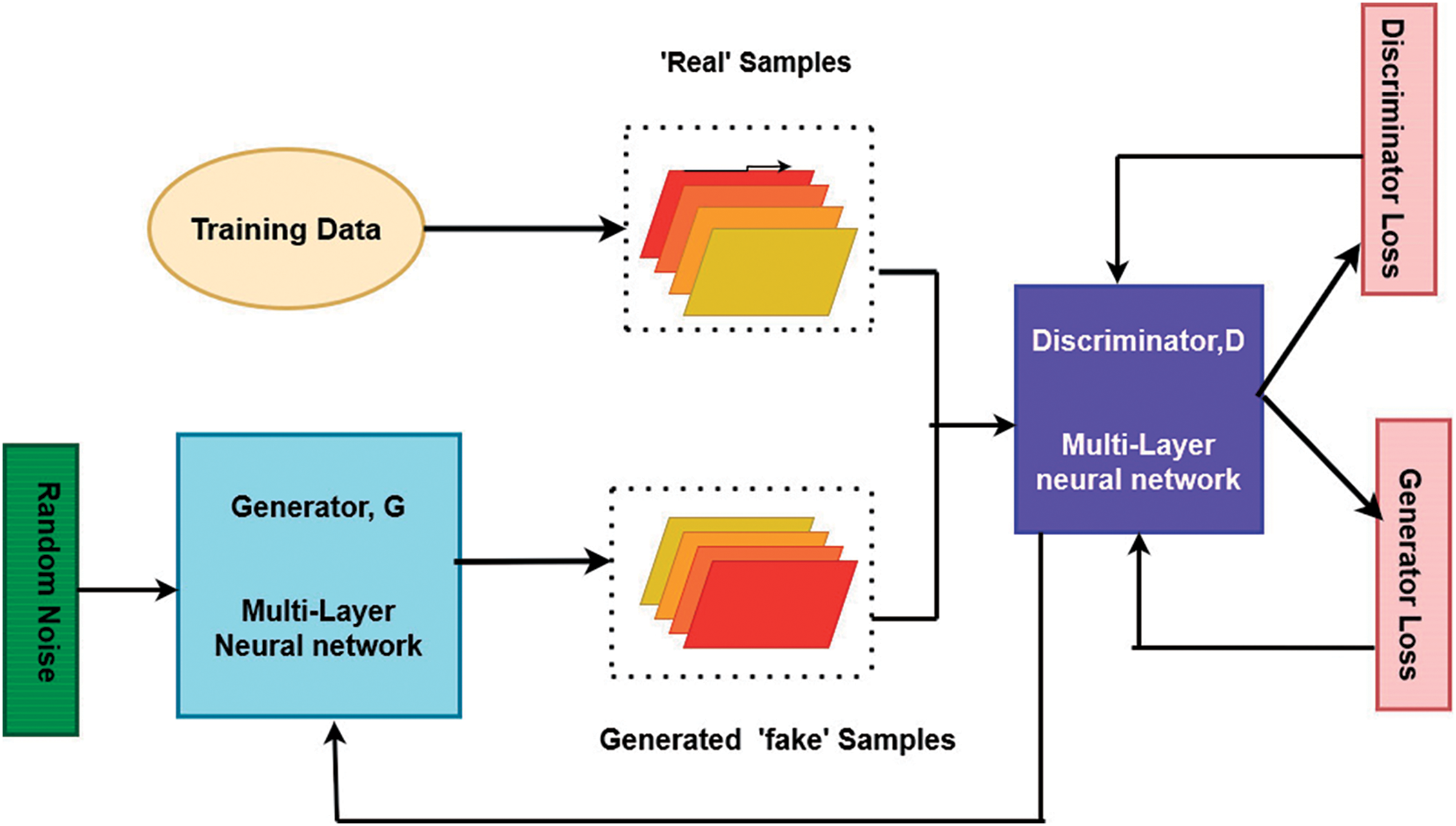

A Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) consists of two main components: the Generator (G) and the Discriminator (D), both of which are neural networks. The Generator creates synthetic data samples (such as images) that mimic real data by transforming random noise input into realistic outputs. On the other hand, the Discriminator distinguishes between real data samples and fake samples by the generator. This setup creates a competitive scenario where the Generator tries to fool the discriminator, and the discriminator works to correctly identify real vs. fake data. Both networks improve their abilities through adversarial training, updated iteratively based on their performance against each other. The basic working principle of GAN is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Working principle of GAN

The training process involves the generator minimizing its loss function by producing more realistic fake samples, while the discriminator maximizes its accuracy to classify real vs. fake. The overall objective of a GAN is to reach a point where the generator’s synthetic outputs are so realistic that the discriminator cannot reliably distinguish them from real data. The combination of these two networks allows GANs to generate high-quality data across various domains, such as image synthesis, data augmentation, and even cross-domain data translation (e.g., converting CT images to MRI). This architecture is at the core of many advancements in deep learning, especially in fields where generating realistic synthetic data is crucial, such as medical imaging, autonomous driving, and creative arts.

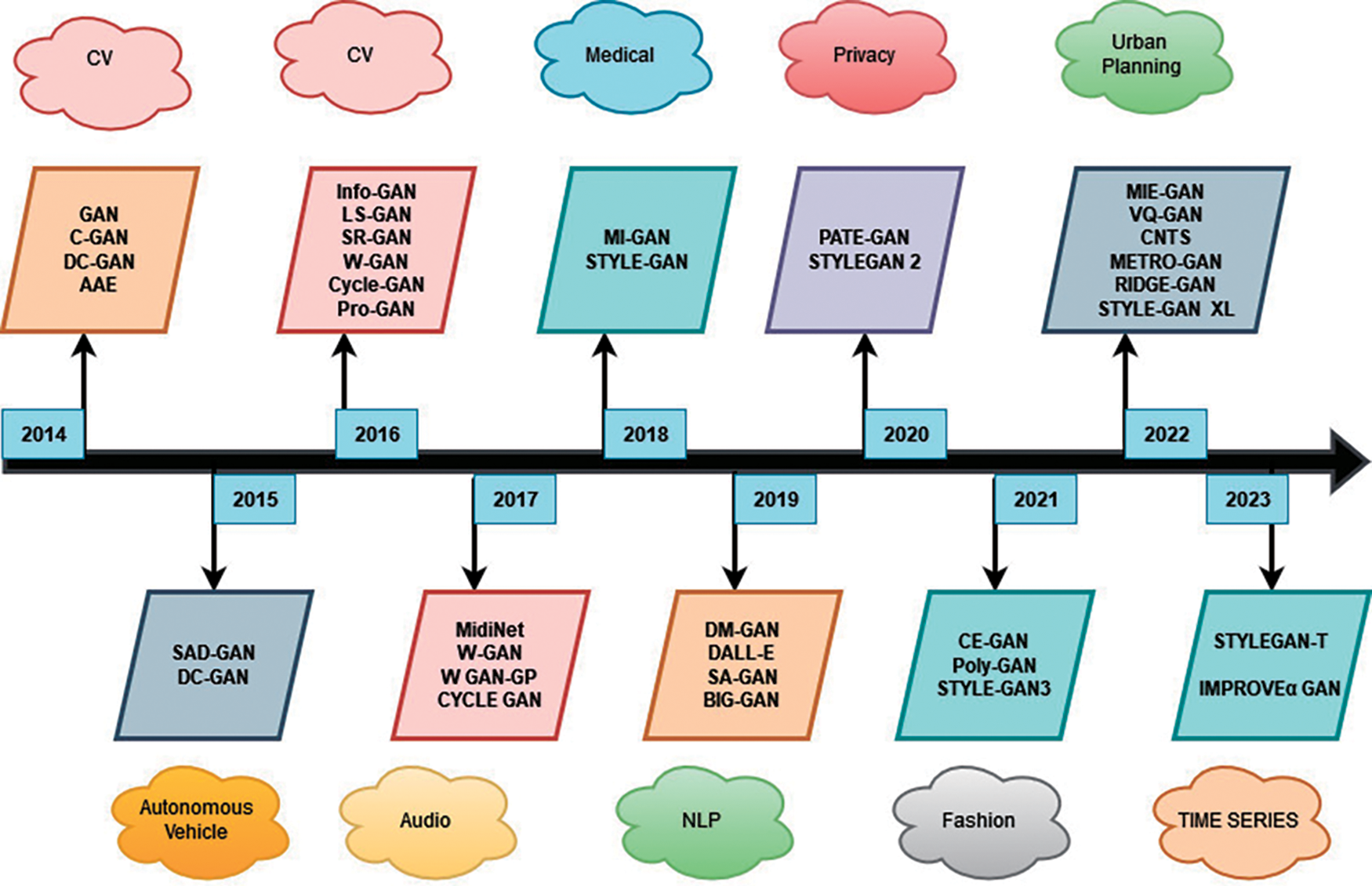

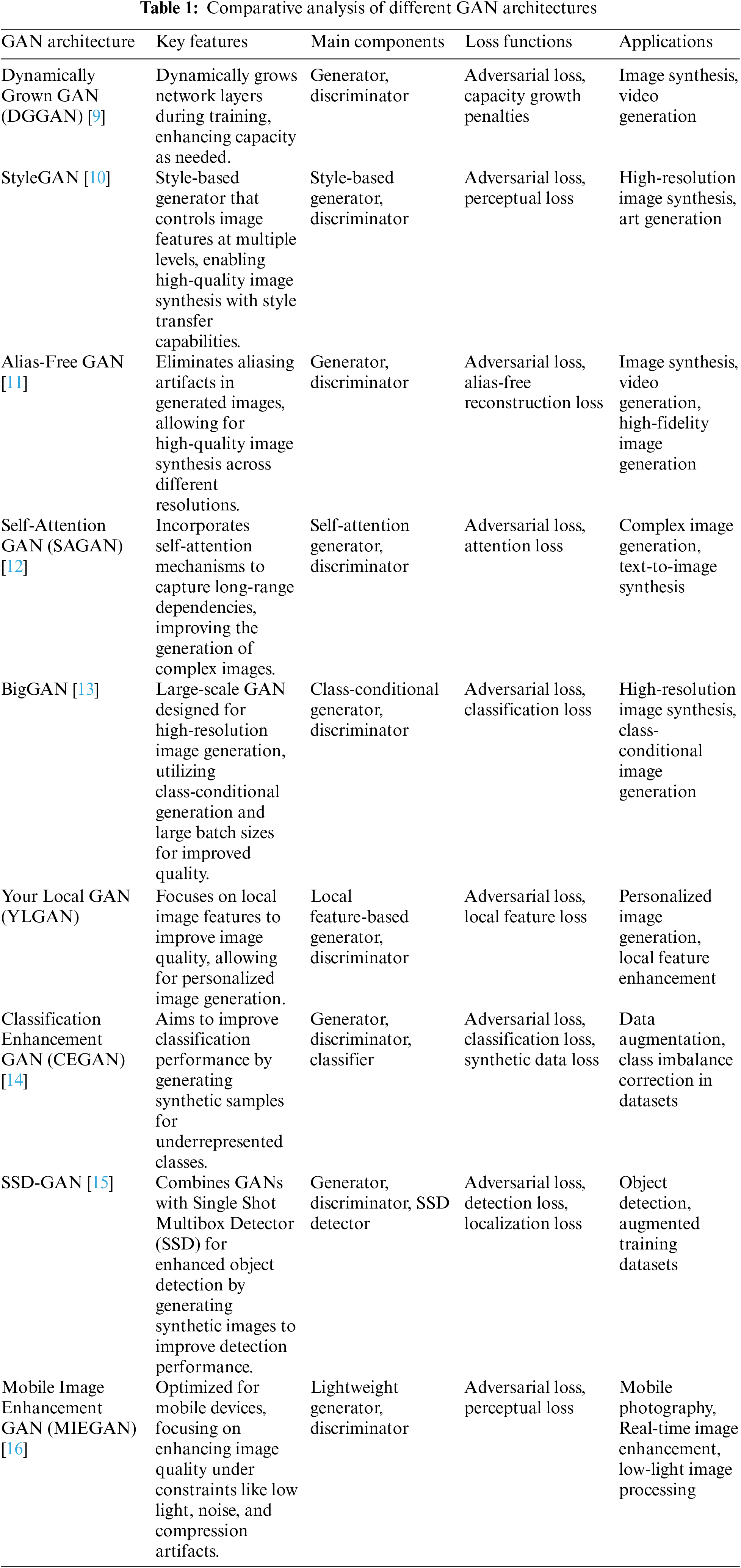

Over the years, different GAN architectures have been introduced, with their release dates visualized in Fig. 6, providing a timeline of their development. Table 1 details these GAN architectures, highlighting key components such as their main building blocks, the loss functions they employ, and their specific applications. Each of these architectures has been designed to address various es in GAN training, ranging from roving the quality of generated outputs to stabilizing the training process. The table offers a comprehensive view of how different types of GANs have evolved and adapted to meet the needs of diverse fields, from image generation and super-resolution to medical applications and beyond.

Figure 6: Timeline of GAN architectures

2.2 Datasets used in GAN Models

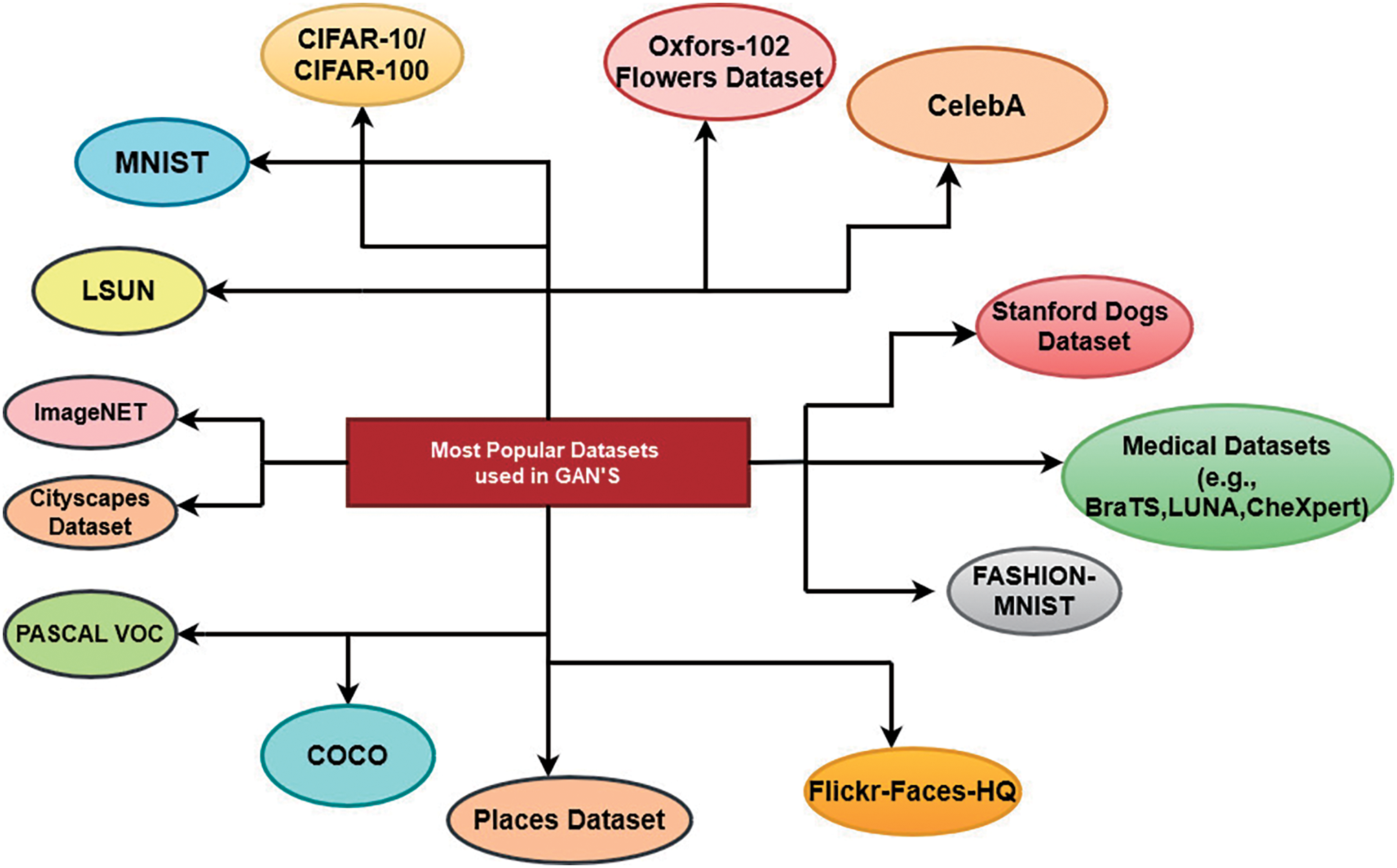

Some popular datasets commonly used for training and evaluating GANs (Fig. 7), particularly in fields such as image generation, medical imaging, text-to-image synthesis, and video generation are:

• MNIST dataset [17]: It contains handwritten digits (grayscale,) and the size of the dataset is 70,000 for each image of size 28 × 28.

• CIFAR10/CIFAR-100 [18]: It contains RGB images of different objects, and the size of the dataset is 60,000.

• CelebA dataset [19]: It contains Celebrity face images (RGB), and the dataset size is 200,000+ images with 40 attribute labels.

• LSUN dataset: Large-scale Scene Understanding Dataset. It contains High-resolution images (e.g., bedrooms, churches, towers) and millions of labeled images across different categories.

• ImageNet dataset: It contains a Large-scale object recognition dataset (RGB), and the dataset size is 14+ million labeled images across 1000 classes.

• Fashion-MNIST [20]: It contains Fashion item images (grayscale), and the size of the dataset is 70,000 28 × 28 images.

• Stanford Dogs Dataset: It contains Dog breed images (RGB), and the dataset size is 20,580 images across 120 classes.

• Cityscapes Dataset: It contains Urban street scenes (RGB), and the dataset size is 25,000 high-resolution images.

• PASCAL VOC: It contains an Object detection dataset (RGB), and the size of the dataset is 20,000 images across 20 object classes.

• LSUN-Bedroom/LSUN-Church: It contains High-resolution indoor scenes (RGB), and the size is over 3 million images of bedrooms and churches.

• Oxford-102 Flowers Dataset: It contains Flower images (RGB), and the dataset size is 8189 images across 102 flower categories.

• COCO (Common Objects in Context): It contains an Image dataset with objects in natural contexts, and the size is 330,000 images across 80 object categories.

• Medical Datasets (e.g., BraTS, LUNA, CheXpert): They contain MRI, CT, and X-ray images for medical applications.

• FFHQ (Flickr-Faces-HQ): It contains High-quality face images (RGB), and the dataset size is 70,000 images at 1024 × 1024 resolution.

• Places Dataset: It contains Scene images, and the size of the dataset size+ a million images across 365 categories.

Figure 7: Overview of datasets used in GAN models

3 Review of Existing Models for Different Applications

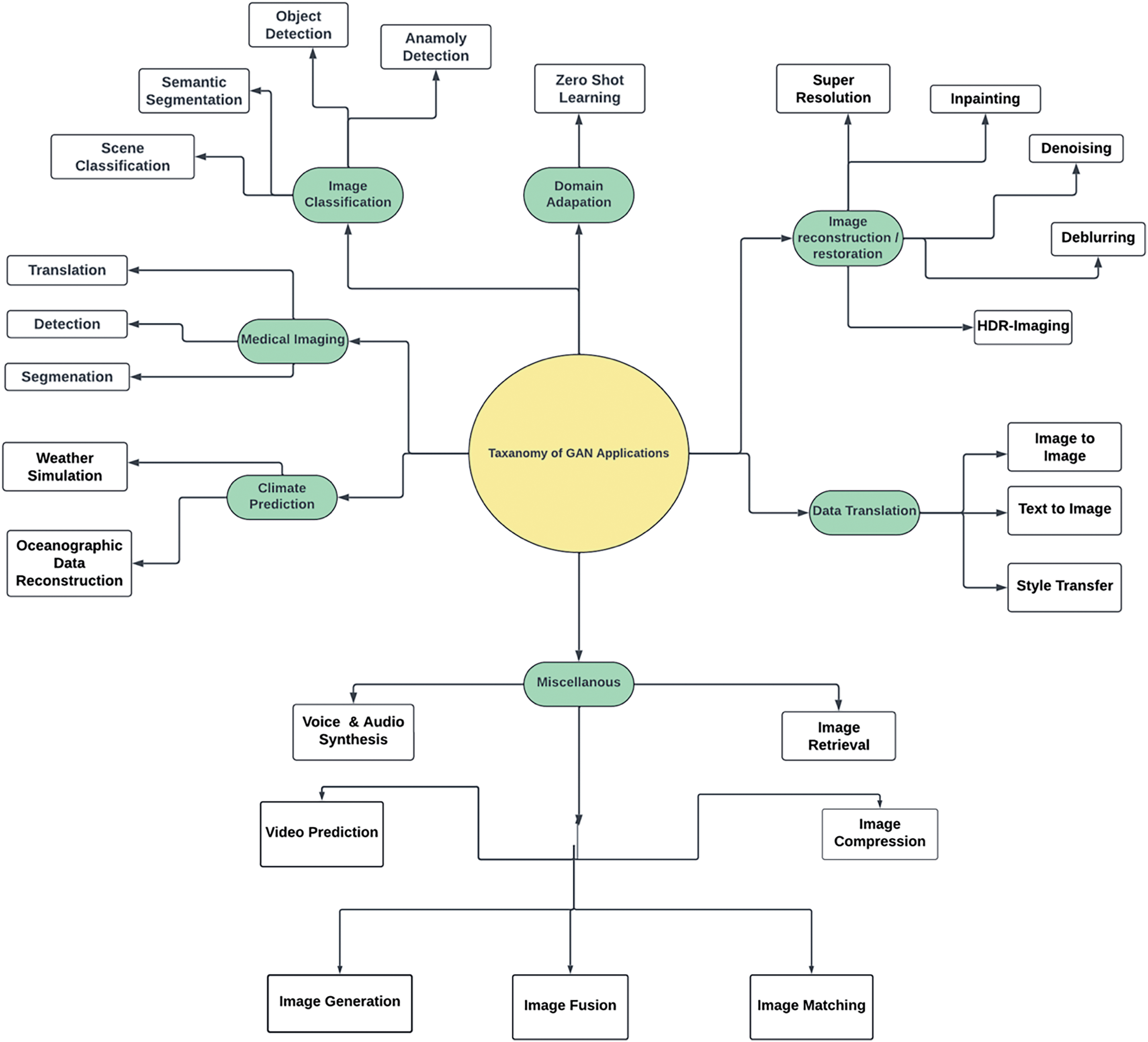

GANs have been considered significant contributions to deep learning, having been utilized to address problems of various complexity in domains such as image generation, medical imaging, fault diagnosis, and augmentation of data samples. It is presented as a review of the key contributions and important advancement of GAN architectures to diverse domains such as image processing, source separation, and generation of synthetic data samples. The PRISMA guidelines guide the systematic review toward a clear, structured analysis literature analysis of GAN applications (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Overview of GAN’s applications

GANs hold very promising applicability in the medical imaging domain, addressing many of the above problems: scarcity of data, high-resolution image reconstruction, and anomaly detection. For example, GANs have been used with good efficacy for breast cancer detection data augmentation. Smart GAN has applied reinforcement learning on the synthetic data generated by GANs to augment the precision of the classifiers for detecting abnormal tissue. Likewise, multi-attention GAN models have been used to segment fundus images to diagnose diabetic retinopathy. The progress in the accuracy due to the focus on lesion-specific features was remarkable. Its applications can also be seen in brain MRI inpainting. Missing regions in scans are reconstructed by architectures GAN such as ER-GAN, which help diagnose when complete data is unavailable. Such demonstrations also show how GANs improve data generation and make diagnostics more workable in live clinical practice, thus promoting better patient outcomes and fewer diagnostic failures.

In the network security domain, GANs have addressed some crucial challenges: intrusion detection, a defense mechanism against adversarial attacks, and detecting anomalies in real-time systems. For example, GAN-based IDS uses the Wasserstein loss functions to generate synthetic traffic data to detect minority class attacks like DDoS. The hybrid architecture of GAN-GRU has proved useful in enhancing detection accuracy while minimizing network vulnerability against distributed denial-of-service attacks by analyzing the temporal features in network traffic. In the cybersecurity world, EVAGAN is a variant of Evasion GAN, which is effective for generating adversarial samples for robust model training in low-data settings. These use cases have explained how GANs can contribute to resilience against evolving cyber threats and thus have hardened up next-generation communication systems by safeguarding data across different industries & deployments.

Apart from these domains, GAN has shown its applicability in complex, multifaceted applications such as environmental monitoring and autonomous systems. Conditional GANs with transfer learning have been well applied in oceanic DEM reconstruction for remote sensing applications from low datasets, which have improved geospatial data interpretation accuracy. The cycle-consistent GAN is further improved for night time autonomous driving to make the images clearer: their object detection and segmentation performance will be enhanced. Applying transformer-augmented GANs to hyperspectral imaging facilitates more effective extraction of spectral and spatial features in the context of land-use classification, mineral detection, among other applications. These practical applications attest to the capability of GANs in resolving complex problems stemming from multiple domains, bridging the gap between the development of theoretical ideas and actual practices.

In medical imaging, metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, and stability need to be optimized since high-risk clinical decision-making processes are at stake. The accuracy of the diagnostic systems significantly influences the reliability because any potential errors associated with them can lead to misdiagnoses or delayed treatments. For instance, in breast cancer detection, high accuracy of outcome classifies malignant cases with minimal false negatives that are crucial for early intervention. Another important measure for identifying subtle anomalies in medical images is sensitivity, such as the microcalcifications that mammograms have to detect or small lesions in brain MRIs. The other important aspect of model training is stability, with guaranteed consistency in the quality of the model’s synthetic images. Unreliable outputs due to GAN instability, which manifest as either mode collapse or divergent training, compromise the quality of synthesized medical datasets. For stable GAN models, ensuring their reliable performance on augmenting datasets for rare conditions or improving the resolution of diagnostic imagery, loss functions are optimized for stable GAN models like Wasserstein GANs (WGANs).

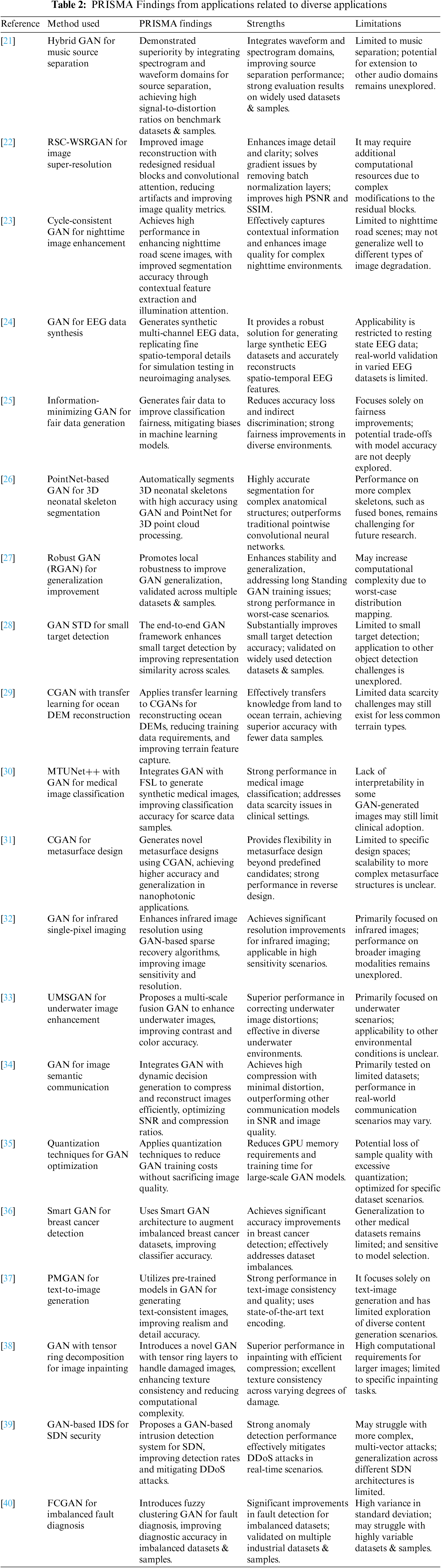

In the dynamic and unforgiving realm, what matters most in network security metrics are accuracy, precision, and robust detection against adversarial attacks. In network intrusion detection, accuracy refers to distinguishing between normal and malicious traffic with minimal errors; this is especially important for identifying stealthy attacks, such as Advanced Persistent Threats. Again, accuracy, but especially for minority classes, is crucial in false positives reduction, as otherwise, administrators can be overwhelmed by noise alerts while missing critical threats. Robustness is another key metric of GAN-based systems, and the ability of adversarial attacks to mislead classifiers describes it. For example, EVAGAN enhances this aspect by producing adversarial samples designed to train models against evasion tactics. While in medical imaging, stability involves confirming the reliability of data for the diagnosis, network security requires flexibility with quickly changing attacking vectors and fast decision-making for a level of integrity preservation in systems. These two requirements indicate the domain-specific importance of performance metrics tailored to specific challenges and goals.The PRISMA Findings from Applications related to diverse applications are illustrated in Table 2.

3.1 GAN Architectures for Image Processing

Improvements to the quality of images through GANs have recorded an important rate. Classic GANs are effective but narrow down in many areas, such as the edges becoming less smooth, loss of detail, and color distortion on the same produced images. A new Residual Super-resolution GAN was proposed in reference [22] using residual block redesign and removing the batch normalization layers to overcome these constraints. Such new techniques aid the model in enhancing the high detail and clearness of the images while bettering its performance compared to conventional models like SRGAN on standard datasets, such as Div2k and Set5. Training the model further using the Wasserstein distance stabilized the model. It showed that the changes in the architecture of GAN significantly affect the quality of image generation.

In the context of nighttime road scenes, a cycle-consistent GAN has been proposed when images are often degraded by noise and contrast distortion [23]. The advancement of this GAN model brought about improvement in segmentation and object detection performance through a multi-scale discriminative network and an illumination attention module. Therefore, the model depicts the improvement of nighttime image naturalness and clarity, and it supported this outstanding performance by designing the receptive field residual module and improved loss function.

Underwater image enhancement has recently been driven by many breakthroughs thanks to GAN-based approaches. Based on residual dense blocks and multiple parallel branches, the Multiscale Fusion Generative Adversarial Network, named UMSGAN, is proposed to correct color distortion and enhance contrast in complex underwater images, effectively capturing deeper image features and restoring details of underwater environments. Notably, compared with the latest state-of-the-art technique, this approach indicates tremendous improvement in the quality, fully demonstrating that GANs are versatile for image restoration.

3.2 GANs for Medical Use Cases

Data generation for medical uses using GANs has been extremely priceless, especially as a method of countering the deficit of labeled data in more sensitive or critical fields like medical imaging. One application in such a field is developing a system using GAN-based few-shot learning, MTUNet++ [30], to boost the accuracy of medical image classifications using synthesized medical images for training. This model incorporates an attention mechanism to focus the models on relevant regions in medical images to enhance the performance of the medical image classifier. The application of GANs in augmenting imbalanced datasets to detect breast cancer has been promising in other areas, and such applications are depicted in Smart GAN architecture that uses reinforcement learning to select the most effective GAN model for image augmentation. These GAN-based approaches exhibit great improvements in classification accuracy while reducing overfitting in imbalanced datasets, which reveals a great potential application area of GANs in healthcare applications.

3.3 GANs in Fault Diagnosis and Data Augmentation

GANs have also been applied to fault diagnosis, where, in many cases, the leading problem arises from unbalanced datasets. Fuzzy Clustering GAN [40] incorporates fuzzy clustering to enhance the discriminative ability of the discriminator and improve the detection accuracy of surface defects in textured materials. Further optimization was brought through FusionNet along with conditional augmentation techniques for generating diagnostic samples, which surpassed traditional techniques in case the concerned dataset was DAGM 2007 or CCSD-NL Magnetic-Tile-Defect. This excellent innovation shows the application of GANs for specific problems in industrial environments. It gives a good solution to faults.

Another important application of GANs has been generating unbiased data for fighting biases in machine learning. The information-minimizing GAN [25] generated unbiased data and reduced adverse influence by sensitive attributes throughout training. This GAN-based approach not only improved the model’s fairness but also enabled the generation of synthetic data for underrepresented groups, thereby underscoring the role of GANs in developing ethical AI.

3.4 GANs for 3D Segmentation and Ocean DEM Reconstruction

GANs have been broadly applied in 3D data processing to automate complex anatomical segmentation. The PointNet-based GAN model [26] is used for neonatal skeleton segmentation from 3D CT images, displaying a higher accuracy rate than traditional methods. This means it is based on a correct anatomical model that enables this new possibility in medical simulations, especially in childbirth predictions.

This, coupled with geospatial applications, has shown promise in the DEM reconstruction using GANs. One example includes adopting a CGAN based on transfer learning for reconstructing ocean DEMs [29], which evolved with knowledge flow from land DEMs towards actualized ocean terrain. Such a model achieved highly enhanced DEM reconstruction accuracy and thus facilitated the generalized use of GANs in environmental science and the analysis of geospatial data samples.

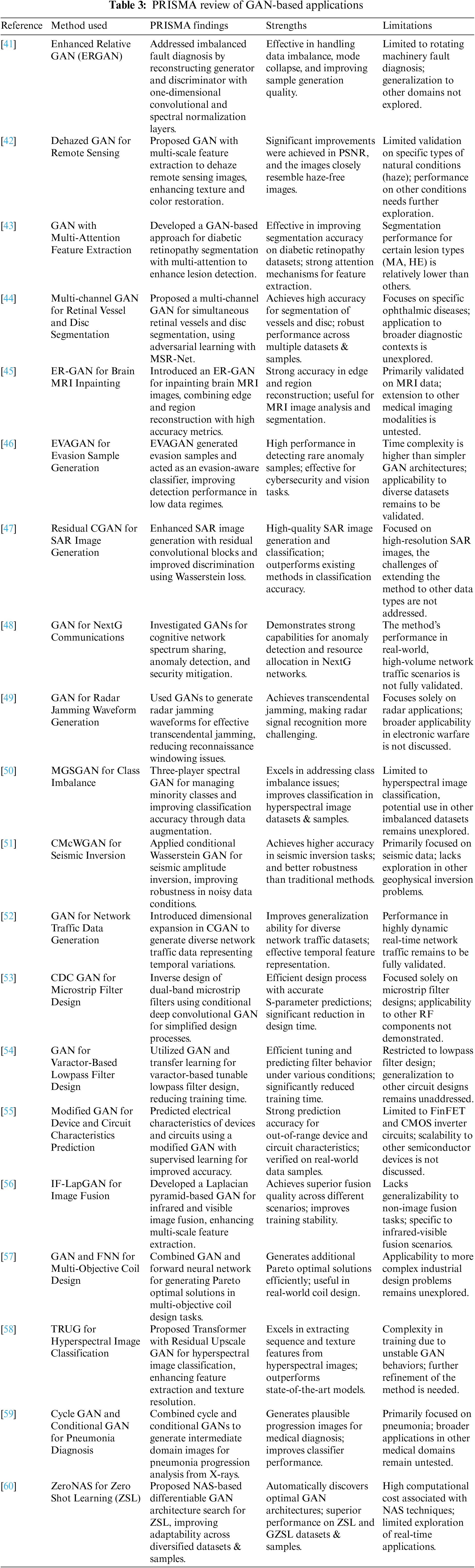

3.5 Towards Mitigating Instability and Enhanced Generalization in GANs

A common issue with GANs is instability during training and poor generalization to unseen data samples. For this purpose, a new Robust GAN (RGAN) model was proposed in [27], promoting local robustness within a small neighborhood of the training samples. This improvement in the generalization of the GAN model is better than the traditional GAN model for CIFAR-10 and CelebA datasets by generating the worst-case input distribution to the generator. This strategy has shown that robustness built in GAN training enhances the stability and generalization of the model, and, therefore, the position of RGAN as an improvement to architecture building sets in GAN is quite exceptional. Table 3 illustrates the PRISMA Review of GAN-based applications.

3.6 GANs in Fault Diagnosis and Data Augmentation

Applying GANs to fault diagnosis, especially in the case of imbalanced datasets, has recently formed a topic of interest. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis is a significant area in industrial maintenance. However, data distribution is mainly imbalanced. To solve that, an Enhanced Relative GAN (ERGAN) was introduced [41], using one-dimensional convolution layers along with spectral normalization to enhance the quality of generated samples. More importantly, using the relative loss function with an incorporated gradient penalty made the training stable, giving far superior fault classification performance beyond the traditional method. This work demonstrates how meaningful synthesized data can be created when utilizing GANs under imbalanced conditions and why their effectiveness in fault detection makes them particularly adept for industrial applications.

Next, MGSGAN [50] introduced a three-player spectral GAN architecture that addressed class imbalances in hyperspectral image data samples. The availability of the mixture generator, along with the sequential discriminator, made it capable of precise generation of the minority class, thereby improving the performance of the classifiers. Such architectures explain how flexible GANs can be for enriching the data to maximize classification accuracy, mainly when working with sparse or underrepresented datasets & samples.

3.7 Remote Sensing and Image Reconstruction

GAN innovations have further helped improve various remote sensing applications. Most traditional CNN-based methods, implemented in image dehazing techniques, do not extract features accurately, thus poorly performing the task. However, the major concern here is the development of a novel GAN for the image dehazing technique, applied with multi-scale feature extraction modules and HSV-based color loss function [42]. Such integration of parallel discriminators has enhanced the recovery of texture and background features and mainly shows superior PSNR and image clarity results. This kind of development demonstrates the capacity of particular GAN architectures to enhance the quality of remotely sensed data, under even adverse conditions such as haze.

Another research also demonstrated an advanced conditional GAN for generating SAR images with high-resolution outputs. The approach integrated residual convolution blocks and gradient penalty-based discriminators to handle the issues concerning unstable gradient updates and the generated image’s quality. Furthermore, training stabilized by using Wasserstein loss-provided high-quality SAR images. This is proof of the greater need for loss function refinement and architecture components fine-tuning in specific imaging applications, remote sensing, where the clarity of the image and, more importantly, the fidelity of the texture is of immense importance.

3.8 GANs in Medical Image Segmentation and Reconstruction

GANs are of excellent promise in the medical domain in dealing with complex tasks such as image segmentation and reconstruction. For instance, a multi-attention GAN was proposed to image regions of diabetic retinopathy in fundus images [43]. An improved residual U-Net using self-attention mechanisms could extract local and global lesion features, while external attention could correlate features from different samples. PatchGAN-based discriminator enhances the segmentation performance with high Dice coefficients for all the various kinds of lesions. This work exhibits how GANs assist enhancestic equipment capabilities for medical imaging by improving attention mechanisms-based segmentation accuracy.

Besides, the ER-GAN model was developed based on brain MRI image inpainting, using GANs to reconstruct missing parts of an image [45]. This would indicate that the dual GAN architecture, which focused on edge reconstruction and region filling independently, utilized pixel intensity information to create the probable edges and textures. This strategy was found to have quite high accuracy by using Jaccard and Dice indices; hence, it may demonstrate the capability of GAN in producing realistic medical images, especially when data is incomplete or missing.

3.9 Improvements in GAN Applications toward Adversarial Training and Cybersecurity

In addition, GANs have also been used intensively for adversarial sample generation to train machine learning models for cybersecurity. In this area, a new method called EVAGAN-for short, Evasion GAN-was recently introduced in [46] for generating evasion samples in low-data regimes such as medical diagnostic imaging and cybersecurity botnet detection. It was demonstrated that EVAGAN is significantly better than the popular ACGAN-Auxiliary Classifier GAN for adversarial sample generation, leading to higher detection performance and improved training stability. This demonstrates GANs’ application to the adversarial training method, a necessity in hardening machine learning classifiers against malicious inputs when applied in cybersecurity.

Similarly, GANs have been applied for spectrum sharing and anomaly detection in next-generation cognitive networks [48]. GANs proved useful in synthesizing field data to foster semi-supervised learning and recover corrupted bits in communication signals. GAN applications in cognitive networks demonstrate how versatile GANs are in extending their utility to resource allocation and security-related tasks in wireless communications.

3.10 GANs for Zero-Shot Learning and Domain Adaptation

The GAN architectures have further supplemented zero-shot learning. While releasing ZeroNAS [60], a NAS model based on GAN for neural architecture search, research has moved ahead to recognize the efficiency of GANs in optimizing architecture for ZSL tasks. The well-tuned search within the generator and discriminator architectures brought ZeroNAS to discover the models performing fairly well over diverse datasets & samples. This would eliminate the need for trial-and-error methods to architecture design, illustrating how GANs can automate optimization for even better performance in ZSL applications.

Combining this with domain conversion by using conditional GANs in the detection of pneumonia [59], it was well established that GANs were quite versatile in the domain adaptation process to generate images that illustrate the progression of diseases. This model was effective enough in converting normal chest X-ray images into those affected with pneumonia so that further analysis could be done on the development of the disease. Domain adaptation by GANs to medical imaging is another proof of its capability to enhance diagnosing and planning treatment for healthcare sectors.

The hyperspectral classification model has utilized a new version of the GAN architecture with Transformer blocks, which were recently introduced. When transformers are used with GANs, better spectral feature extraction and texture resolution are observed compared to common problems in hyperspectral imaging, where the sequence information gets lost. Using Transformer-based residual upscale blocks, even in the proposed TRUG model, would ensure higher performance than CNN-based GANs. The paper extends the trend of GAN-related research into using Transformers so that better models can be used and further applied to feature extraction over sequential data samples.

3.12 GANs in Climate Prediction and Remote Sensing

GANs have recently been adapted to climate prediction to improve the resolution of downscaled climate models. DeepDT, a novel GAN-based framework, appeared in [61] to eliminate artifacts from high-resolution climate prediction. This model employed residual-in-residual dense blocks to extract features entirely, meanwhile, with a special training scheme: independent training of the generator and discriminator. Evaluations on climate datasets demonstrated that DeepDT superiorly outperforms the traditional CNN-based models, which implies that GANs have a bright chance for further improvement in the accuracy and quality of climate predictions with small-scale regional predictions from large-scale outputs.

The applications of remote sensing have also favored the architectures of GANs. Another important application is image mosaicking of geographic data in which reference image mosaicking is introduced by work in [62] using GAN to harmonize color differences in stitched images. Using an integration of graph cut and pyramid gradient methods, this model achieves radiometric and spectral fidelity superior to existing ones in creating seamless mosaics from multitemporal or multi-sensor samples. This would demonstrate the real potential of GANs to improve remote sensing image processing, especially in generating consistent, high-quality outputs in challenging environments. In another endeavor, authors in [71] developed SIF-GAN for cloud removal in multi-temporal remote sensing images. SIF-GAN chose channel attention to select feature fusion from states at other times, and finally, it produced a better result than the conventional methods in cloud removal. This depicts how GAN can be applied to demanding applications like image restoration, where other parts may obscure foundational information. GANs for zero-shot Learning and Object Detection GANs have also shown their enormous potential in zero-shot learning (ZSL).

Conventional ZSL methodologies are based on hand-crafted models that fail to adapt and sustain across multiple datasets and samples. This challenge is, therefore, overcome by proposing the evolution of GAN search, EGA, and NS, which was first introduced in [64]. The said framework used NAS to evolve both the generator and discriminator for an adversarial setting. EGANS would outperform the current state-of-the-art approaches on benchmark databases: CUB, SUN, AWA2, and FLO by auto-designing architectures optimized for stability and adaptation. This work underlines the potentiality of GANs in dynamic adaptation towards various domains, which adds to its adaptability towards Zero-Shot Learning scenarios. Table 4 illustrates PRISMA Analysis of Advanced GAN architectures in diverse applications.

In the object detection field, occlusion remained one of its challenges. In [68], a Ganster R-CNN model was offered by integrating the improved GAN architecture with Faster R-CNN, which enhanced the detection accuracy of occluded objects. This involved combining the feature maps from various layers to extract occluded samples for training in the model. This led to massive improvements in detection accuracy on MS COCO and VOC datasets. The synthesis of occluded features in samples indicates the potential power of GANs in object detection, mainly when complex detectability is involved.

3.13 GANs in Medical Imaging and Explainability

GANs are becoming of great interest in medical imaging, where accurate and explainable models are becoming increasingly necessary. In [66], a state-of-the-art improvement on the figures of merit was presented by FIGAN- introducing Feature Interpretation GAN for improving the explainability of CNNs applied to medical image classification. FIGAN employed conditional GAN to synthesize images that cover the entire spectrum of features used by CNNs. This approach, therefore, provides clearer interpretations of pretty indistinct or vague medical images such as that one showing pulmonary fibrosis. This framework addresses some shortcomings of post hoc explainability methods since it offers visual interpretations that could happen in better ways than CNN’s decision-making process.

Based on the FC data from resting state fMRI, authors in [76] designed a Graph Convolutional Network-based Conditional GAN (GC-GAN) for MDD diagnosis. Incorporating GCN within the generator and the discriminator assisted this model in catching accurate FC patterns between the brain regions, improving the diagnoses of MDD. How GC-GAN contributes to diagnoses utilizing synthetic FC data emphasizes one of the applications of GANs in medical diagnostics, especially in Scarce data scenarios.

3.14 GANs in Defensive Applications of Adversarial Defense and Cybersecurity

GANs have been used in cybersecurity to improve network intrusion detection systems for handling issues related to class imbalance. In this context, the paper published in [65] introduced a Wasserstein distance and reconstruction error-based GAN NIDS intended to generate new samples of the minority class, so that more rare types of attacks can be found. This model performed well compared to traditional AI-based NIDS, focusing on using GANs for security and the specific goal of dealing with new and unknown attacks.

Mitigating adversarial attacks on deep learning algorithms has turned out to be challenging; GAN-based defense schemes, however, have potential that may make this more feasible. Providing a two Step transformation architecture towards enhancing the robustness of deep neural networks against adversarial examples, the adversarially Robust GAN (ARGAN) in [80] optimized the generator to counter vulnerabilities within the target models, thus showing tremendous performance on accuracy for legitimate input as well as providing robust defenses against adversarial perturbations. It also addresses a critical problem regarding AI security, as it poses a strong solution towards ensuring the integrity of machine learning models in adversarial environments.

3.15 GANs in Network Embedding and Knowledge Representation

Another area where GANs have succeeded is network representation learning, or network embedding. The WalkGAN model [79] used GANs to reproduce the random walk on a network with synthetic vertex sequences employed to infer unobserved links between nodes. This improved the network classification and link prediction tasks over the traditional embedding methods. Such an ability to capture the underlying network structure through adversarial training reinforces the idea of the use of GANs in representing complex samples of relational data samples. Reference [77] proposed ANGAN, a hybrid model integrating Skip-gram and generative adversarial networks to get representations that capture structure and attribute information in attribute-augmented networks. This, in turn, upgraded the representation of the heterogeneous networks because, in this method, all the embeddings produced were strong and solved the connectivity issues between nodes and attribute proximities between nodes. Their adoption of GANs for the task proved them applicable in sharpening knowledge representation tasks by underlying complex interactions within network data samples.

This section offers an intensive comparison of different GAN models and architectures across various domains. Table 5 summarizes methods, key performance metrics, the efficiency of GANs, and relevant observations based on the PRISMA framework for systematic review and meta-analysis. The effectiveness of each method’s GAN model is presented in this paper, which is obtained based on performance metrics such as SNR, accuracy, PSNR, SSIM, and many others. Problems in image generation, medical image analysis, network security, and fault diagnosis, among many others, have also been seen as a great presence in solving various challenges due to GAN models. A comparison analysis between these models is done on various fronts: efficiency, as determined by performance metrics, generalization capabilities, and computational stability. Each of the studies undertakes new concepts in GAN architectures, improves the performance of these models, responds to specific challenges in the domains for which they were designed, and enhances the quality of generated data samples.

This PRISMA-based analysis portrays the strengths and novelty of various GAN models across an extensive domain Fig. 8. Some salient observations include that GANs demonstrate exemplary efficiency in managing complex functions such as image creation, medical diagnosis, and network protection, which are superior to other methods based on generalization, accuracy, and computational effectiveness. However, challenges such as extremely high computational costs and instability of the model during training lay opportunities for the future when such optimizations can be applied to even more extensive areas of applications. GANs have been proven on a significant scale by enhancing data generation and the performance of models in an expansive range of domains. This section discussed GAN-based models, including “escape from renormalization”-based variants, such as improved DCGAN and LR-GAN, paired with history’s largest GAN model: 128M-biggan-deep. As seen in Table 6, the models have proven their ability to solve complex tasks while dealing with major obstacles, including data imbalance, generalization, and instability. Although most GAN models, such as improved DCGAN and LR-GAN, proved their supremacy in their applications and delivered better results, the following limitations- computational complexity, mode collapse, and training instability- have all been considered the core challenges. It systematically compares GAN-based methods, where quantitative metrics analyze their efficiency.

The versatility of GAN models is shown by applications of this network ranging from image processing and classification to the diagnosis of faults and network security through PRISMA-based analysis. The results above clearly show the proposed GAN architectures’ efficiency in data augmentation, better generalization behaviour, and, therefore, the potential for improved classification accuracy, especially for imbalanced or low-data regimes. GAN-based applications show great promise in medical diagnostics, remote sensing, and also optimization of complex systems. Training time remains high, though relatively stable training conditions are attained, thus leaving room for further investigation into optimizing these models to expand their reach even further to future applications. Table 7 shows GANs demonstrated their capabilities and huge applications in various domains with significant improvements in image generation, classification, fault diagnosis, and other applications. However, this comes with specific challenges for each application, such as instability during training, mode collapse, and balancing between the generator and discriminator. There is a huge difference in GAN model performance in handling these complexities depending on their design and the specific task. This analysis compares GAN methods in terms of their efficiency by making comparisons based on various performance metrics, such as accuracy, PSNR, and the F1 Score, which offer a detailed overview of their strengths and limitations.

The PRISMA analysis, as per Table 8, sheds light on the many strengths and versatility of the GAN architectures within different application areas. GANs are more efficient in tasks requiring data augmentation, noise reduction, and improving the classification accuracy in imbalanced or complex datasets & samples.

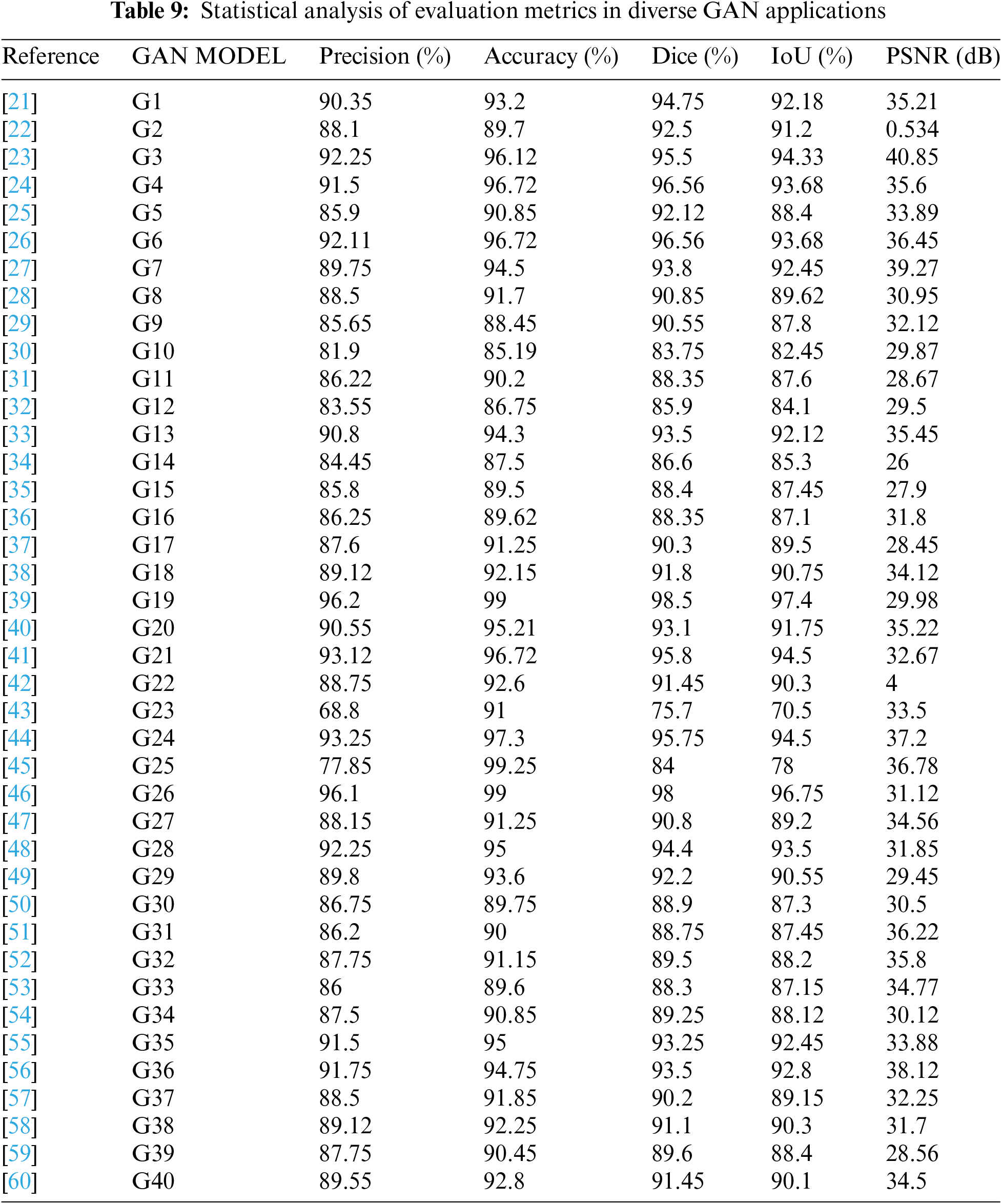

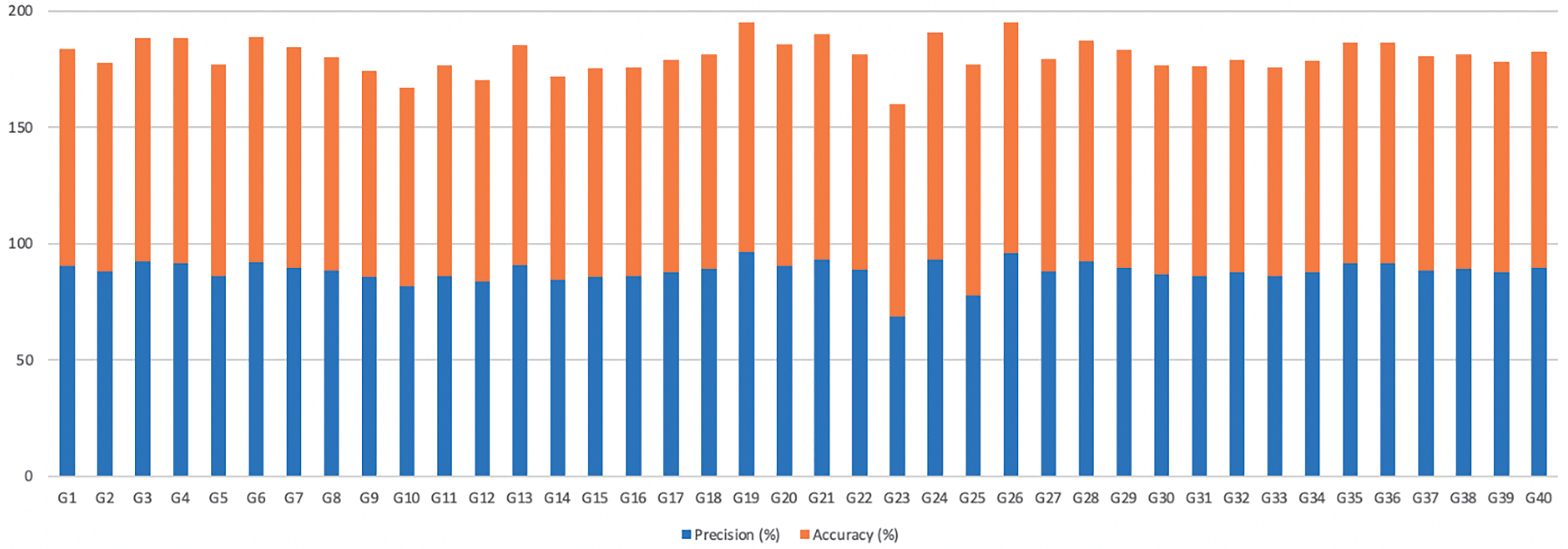

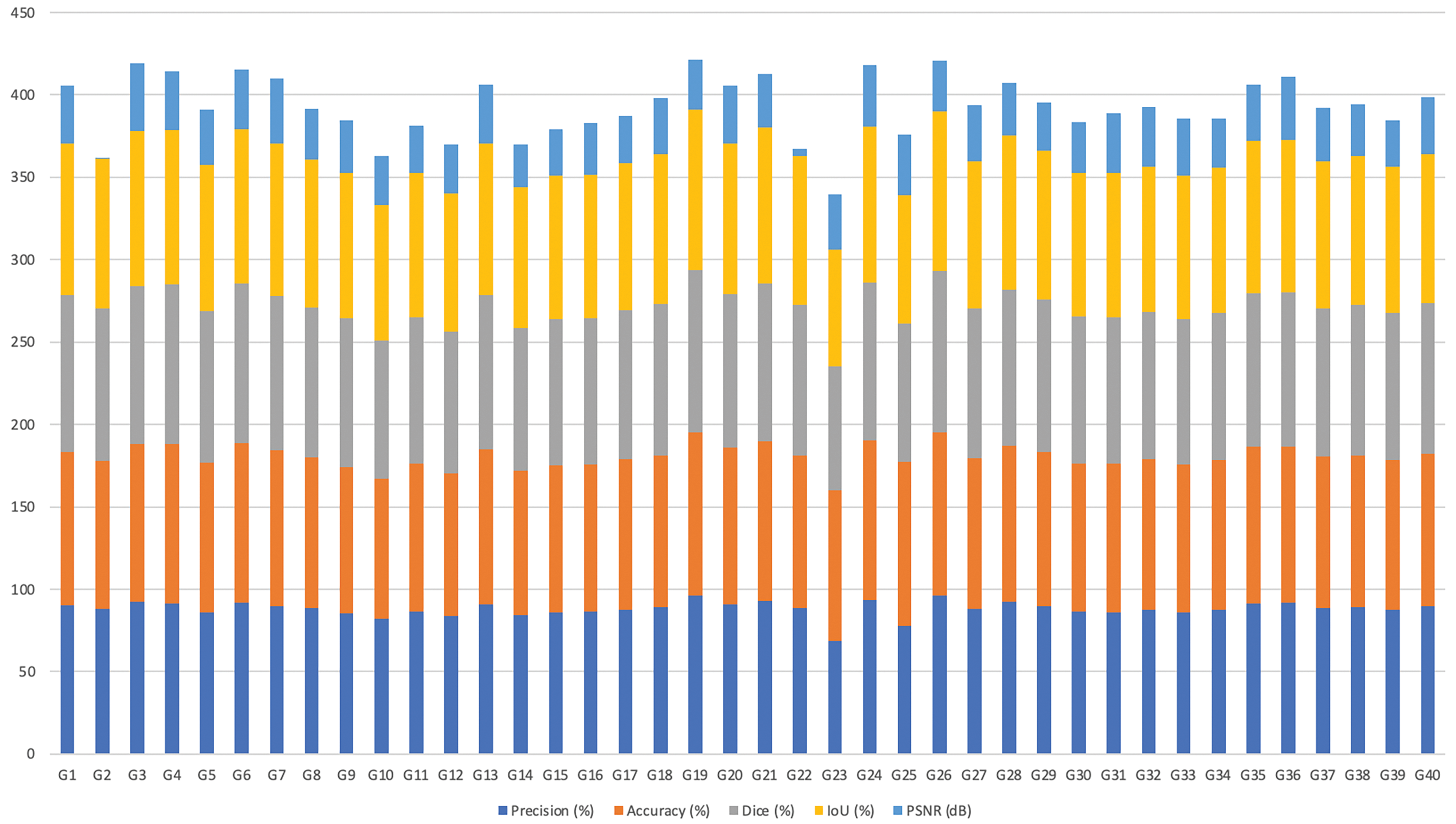

For instance, IGAN enhanced image classification and object detection methods while SIF-GAN enhanced cloud removal for remote sensing data. GAN-based defenses such as ARGAN enhance the robustness of AI systems against adversarial attacks. Also, despite the improvements above, computational complexity and training instability remain prevalent for more large-scale models and real-time operations. At large, the efficiency of GAN is in a continued development path towards opening further possibilities in machine learning and data generation for a wide range of domains. Statistical Analysis of Evaluation Metrics in Diverse GAN Applications is shown in Table 9 and Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Precision & accuracy of different models

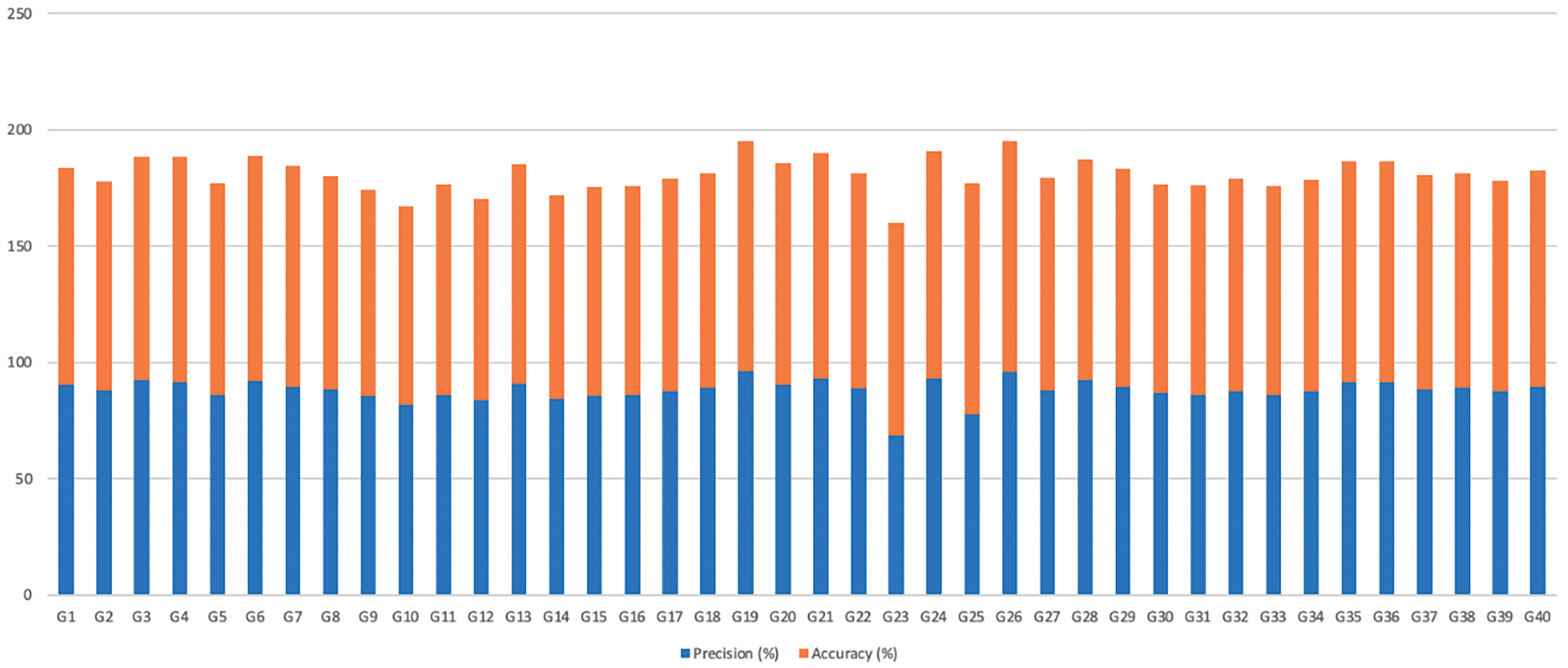

Figs. 10 and 11 illustrate the Dice, IoU & PSNR for Different Methods. Mode collapse and instability are perhaps the two main problems when training GANs. Mode collapse is the failure of the generator to produce more than a few types of outputs, failing to capture data distribution diversity. Instability often occurs due to oscillatory or divergent behavior in adversarial training; the generator fails to converge to its stationary point. It is, therefore, necessary to face these challenges for the applicability of GANs in high-diversity and reliability tasks, such as anomaly detection in cybersecurity or medical imaging. Several research strategies have been proposed over the years for mitigating these issues: loss functions, optimization techniques, and architectural innovations.

Figure 10: Dice, IoU & PSNR for different methods

Figure 11: Statistical analysis of existing GAN applications

Among the popular stability and mode collapse methods are gradient penalty techniques used in Wasserstein GANs, among others. The Wasserstein loss replaces the standard Jensen-Shannon divergence with the Earth Mover’s distance or Wasserstein distance. This provides smoother gradients for optimization, reducing the chance that at some point during training, either vanishing or exploding gradients occur, stabilizing updates to the generator and discriminators. Another approach is architectural modification and the use of alternative loss functions. Techniques such as minibatch discrimination bring diversity to the generated samples by allowing the discriminator to take a batch of generated data rather than individual samples, encouraging variety in the generator’s outputs. Combining these breakthroughs and strong optimization methods can even partially alleviate mode collapse and instability in GANs, making them useful for many applications.

Mode Collapse: This is a common issue when training GANs; in fact, the generator fails to capture the diversity of the real data distribution and produces limited, repetitive outputs. Hence, while synthetic samples are required for tasks where diversified, representative samples are required, GANs may fail in such tasks. Minibatch Discrimination: It is a technique by which the discriminator is allowed to differentiate minibatches of generated data instead of singular samples. Thus, the generator creates diversified outputs. Due to the introduction of variety in the output of generators, it does not suffer from mode collapse.

Adversarial Sample: Artificially generated data meant to fool machine learning models. In network security, primarily, adversarial samples are tested against intrusion detection systems to analyze their resistance to such attack patterns or simulate potential attacks.

Conditional GAN: A variation of the GAN that is conditioned both at the generator and discriminator ends with appropriate additional information, such as class labels or input data samples. Explainability: Mechanisms of providing insight into how a GAN generates data or makes decisions. Explainability becomes extra critical in applications like healthcare, where model behavior could make it easier to support and validate.

Relevance of This Work Study Process

Among the more convincing case studies of medical diagnostics is GAN for breast cancer detection in mammography. Smart GAN integrated reinforcement learning with a GAN-based data augmentation architecture in the experiment. With the smart GAN-based architecture, synthetic mammogram images were generated for underrepresented cases in the datasets. Such an application substantially increased classification accuracy for detecting malignant tumors in imbalanced data samples. GANs have been successfully used in cybersecurity domains to enhance the intrusion detection system. For example, a GAN-based IDS trained on network traffic datasets similar to CICIDS2017 used synthetic minority class samples to overcome the imbalanced datasets. The system has achieved improved detection rates and diminished false positives and only serves to create realistic views of rare attack patterns like DDoS attacks. Besides, EVAGAN (Evasion GAN) has been employed to create adversarial samples that pretend to mimic complex attack behaviors. Therefore, through these case studies, the transformative potential of GANs in delivering stronger infrastructures in cybersecurity against shifting threats can be identified. The other application of GANs concentrates on improving medical image segmentation to diagnosis-attention GAN models have been deployed to segment the fundus images with high accuracy using lesion-specific features. These models use self-attention mechanisms for capturing local and global features, significantly improving the segmentation of microaneurysms and haemorrhages, which is critical for early diagnosis. Combined with PatchGAN-based discriminators, these systems yield high values for Dice coefficients of lesion detection, providing a realistic solution for this challenging diagnostic task. Such case studies emphasize the cross-domain versatility of GANs and highlight their capacity to address challenges within separate domains, such as improving healthcare diagnostics accuracy and building more robust defenses in cybersecurity operations.

A holistic view of several GANs in different applications provides the best impression that significant advancements have been made toward using GANs to solve many problems, including image generation, data augmentation, fault diagnosis, network security, and more. The survey depicts that several models like conditional GANs, Wasserstein GANs, deep convolutional GANs, etc., have come out as the best option for various applications according to their respective merits. Specifically, CGANs, while retaining the general advantages of GANs, possess greater flexibility in the context of classification problems involving imbalanced datasets and even data imbalance levels, especially in network intrusion detection and fault diagnosis applications where balancing data through GAN-generated samples has improved model robustness and accuracy. WGAN-based architectures do, however, stabilize and are very adept at capturing the complexity of data generation tasks within SAR image classification as well as adversarial defense tasks where mode preservation is of major importance. The results also present aspects by which GAN models seem to excel, primarily where scarcity is the main issue with the data. For instance, such models as EVAGAN and FCGAN can achieve great efficiencies in augmenting sparse medical images and fault diagnostics datasets. Such models utilize additional mechanisms, namely attention layers or fuzzy clustering, to boost sample realism and diversity: each tends to improve performance on various downstream tasks. GANs are also superior in the selective information fusion model applied to the SIF-GAN model for removing clouds from remote sensing images, thereby showing that some of the benefits of GANs are improving data quality for reconstruction purposes in images. The biggest strength of GANs in modern applications lies in their potential ability to generate rich, synthetic data in resource-constrained environments. The most frequently used architectures in the analysis include variant versions of CGAN, WGAN, and DCGAN, each standing for different advantages. CGANs have an advantage because the models easily support domain-specific constraints in class conditional output tasks, such as classification and object detection. Although WGAN models have gained widespread popularity in achieving complicated generation tasks such as aerodynamic prediction and seismic data denoising with high precision, DCGANs exhibit some important features for feature extraction and mode preservation regarding image classification of SAR images & samples. The flexibility of such models to operate in different domains proves GANs and their adaptation to the high-fidelity demanding tasks of synthetic data generation sets.

Notwithstanding the gigantic performance boosts, GANs have several areas for further exploration. For example, while generalizing to large-scale or real-time applications, GANs inherently suffer from high computational complexity that calls for significant development work in this area. Among other techniques, model quantization and transfer learning are promising avenues through which training times and resource consumption can be reduced to remain comparable with its accuracy, applied in some of the reviewed papers. Further development of these techniques would allow for deploying GANs more effectively on heavily resource-constrained computing devices or mobile platforms. Also, models that couple GANs with other architectures of deep learning, like the hybrid model of Transformer-CGAN, open up new prospects for improving long-distance extraction of features in problems like network traffic classification. The other possible line is improving the applicability of GAN in unsupervised and semi-supervised learning settings. Some potential has already been realized in GANs, such as network embedding and link prediction when labels are scarce.

Further extension in those domains might be the difference between relatively unstructured Wild West applications and the much-needed maturity for real applications in fields with minimal supervision, including cybersecurity and large-scale network management. Another ongoing challenge is increasing the use of a more resilient defense mechanism against adversarial attacks. This success of ARGAN in defending against adversarial examples underscores why one needs to include GANs in AI safety and how research needs to push forward on optimizing these defense methods as AI systems become increasingly integrated into different critical infrastructures. Conclusion: GANs have firmly established themselves among the most promising machine learning frameworks across various domains. As reviewed in this paper, from CGANs and WGANs to more specialized architectures like SIF-GAN and EVAGAN, aim to be as versatile and capable of addressing the challenges in a wide range of applications from data augmentation to classification tasks and defense against adversarial attacks. Future research directions will probably include improvements in the efficiency and scalability of GANs and the robustness of these models in real-time and low-data scenarios, thereby opening even wider applicability horizons in both old and new fields.

Multiple Modal data fusion represents an emerging field whose possible implications for GANs remain to be explored. Multimodal GANs will, therefore, integrate different data types to increase the richness and applicability of generated outputs. For example, in autonomous systems, GANs could be optimized to fuse visual data with LiDAR readings, enabling a better understanding of the scene under various environmental conditions. Future work should be used to develop architectures that learn efficiently from heterogeneous data sources by preserving cross-modal relationships with different sources. Novel techniques like cross-attention mechanisms or learning in a shared latent space improve the generator’s capacity to synthesize coherent outputs across different modalities. Synchronization over modality and computational overhead will be significant issues to focus on to make multimodal GANs more viable for real-time implementations in the process.

Another frontier to optimize is in Transformer-based GANs, especially for any task that involves sequential processing or data of high dimensions. Transform and their self-attention mechanisms catch long-range dependencies and complex patterns that traditional architectures could otherwise ignore in convolutional setups. When transformer blocks are integrated into GANs, it will be possible to represent sequential data processing while extracting spectral features accurately in hyperspectral imaging. Hybrid architectures could be explored, using transformers for feature extraction and GANs for data generation. Further, there is a need to enhance the stability in training hybrid models since transformer-based GANs suffer from high computational complexity and the sensitivity it poses towards hyperparameter tuning.

GANs in real-time applications and resource-constrained environments: This is another promising direction for applying GANs for real-time applications and resource-constrained environments. Optimizing light GAN architectures can be done through model quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation methods. Such optimizations may lead to deploying GANs on edge devices, such as wearable health devices, which would then be able to generate or analyze data locally with GANs instead of relying on cloud resources. By integrating NAS techniques into designing specific GAN architectures and automating the task, trial and error involving massive decisions regarding architecture selection would also decline considerably in the process. With such a specific focus on these emerging fields and optimizing strategies, future research can extend the applicability of GANs while overcoming current limitations and unlocking their long-debated potential in innovative, real-world scenarios.

In the future of GANs, mode collapse, instability, and computational efficiency should be persistent problems that need to be addressed in further research into Generative Adversarial Networks. The training stability can be improved using adaptive strategies such as dynamic loss balancing and meta-learning frameworks. For instance, setting adaptive learning rates specific to the discriminator and generator could reduce oscillatory behaviors while training. Apart from the use of techniques such as reinforcement learning for the fine-tuning of GAN architectures in classifying diverse datasets, hybrid models combining GANs with other emerging paradigms, like Transformers, may have the potential to achieve better sequence generation performance in applications from time-series forecasting to natural language processing. Availability and diversity of data are also very important factors in research into GANs. The datasets currently available are often limited concerning to demographic or environmental variation, which then limits the generality of learned GAN models in the Future will focus on curating large-scale, balanced datasets for various domains capturing as wide a range of features as possible. For example, the CheXpert and BraTS datasets created in medical imaging could further expand to include diverse populations and rare pathologies. Dynamic datasets with real-world network traffic patterns created in network security can also prepare the training and evaluation of GANs in anomaly detection. NAS would enable the automatic design of optimal GAN architectures, relieving the dependence on manual approaches based on trial and error for a specific task. Explainability mechanisms such as saliency maps or counterfactual analysis must be integrated into GAN workflows to ensure transparency. The sensitive domains include healthcare and finance. Third, research into more resource-efficient GAN variants, such as lightweight or quantized models, can bypass the computation bottlenecks and make GANs more feasible for real-time and edge applications. Combined with all these methodologies and fairness considerations, such as fair training algorithms and robust adversarial defense, this will pave the way for the next generation of GANs that are stronger, fair, and more trustful.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the management of Prasad V Potluri Siddhartha Institute of technology and Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham for providing the necessary support for current study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Uddagiri Sirisha has done the initial drafting and study conceptualization. Chanumolu Kiran Kumar has done the data collection and formal investigation on the studies. Sujatha Canavoy Narahari has performed analysis and interpretation of results. Parvathaneni Naga Srinivasu has supervised the work and done the revision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data corresponding to a study is made available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.59715.

References

1. G. Bouallegue and R. Djemal, “EEG data augmentation using Wasserstein GAN,” in 2020 20th Int. Conf. Sci. Tech. Automat. Control Comput. Eng. (STA), IEEE, 2020, pp. 40–45. doi: 10.1109/STA50679.2020.9329330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. J. Mi, C. Ma, L. Zheng, M. Zhang, M. Li and M. Wang, “WGAN-CL: A Wasserstein GAN with confidence loss for small-sample augmentation,” Expert. Syst. Appl., vol. 233, no. 1, 2023, Art. no. 120943. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Z. Ahmad, Z. U. A. Jaffri, M. Chen, and S. Bao, “Understanding GANs: Fundamentals, variants, training challenges, applications, and open problems,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 1–77, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s11042-024-19361-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. S. Mathew, “An overview of text to visual generation using GAN,” Indian J. Image Process. Recognit., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1–9, 2024. doi: 10.54105/ijipr.A8041.04030424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. M. Megahed and A. Mohammed, “A comprehensive review of generative adversarial networks: Fundamentals, applications, and challenges,” WIREs Comput. Stat., vol. 16, no. 1, 2024, Art. no. 1629. doi: 10.1002/wics.1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. L. Weng, “From GAN to WGAN,” 2019. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1904.08994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. N. K. Manaswi, Generative Adversarial Networks with Industrial Use Cases: Learning How to Build GAN Applications for Retail, Healthcare, Telecom, Media, Education, and HRTech. BPB Publications, 2020. [Google Scholar]

8. J. I. Pankove, “GAN: From fundamentals to applications,” Mater. Sci. Eng.: B, vol. 61, pp. 305–309, 1999. [Google Scholar]

9. L. Liu, Y. Zhang, J. Deng, and S. Soatto, “Dynamically grown generative adversarial networks,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 8680–8687, 2021. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v35i10.17052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. A. H. Bermano et al., “State-of-the-art in the architecture, methods and applications of StyleGAN,” Comput. Graph. Forum, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 591–611, 2022. doi: 10.1111/cgf.14503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. T. Karras et al., “Alias-free generative adversarial networks,” Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., vol. 34, pp. 852–863, 2023. [Google Scholar]

12. H. Zhang, I. Goodfellow, D. Metaxas, and A. Odena, “Self-attention generative adversarial networks,” in Int. Conf. Mach. Learn., PMLR, 2019, pp. 7354–7363. [Google Scholar]

13. T. Y. Chang and C. J. Lu, “TinyGAN: Distilling BigGAN for conditional image generation,” in Proc. Asian Conf. Comput. Vis., 2020. [Google Scholar]

14. S. Suh, H. Lee, P. Lukowicz, and Y. O. Lee, “CEGAN: Classification enhancement generative adversarial networks for unraveling data imbalance problems,” Neural Netw., vol. 133, no. 2, pp. 69–86, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2020.10.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Y. Chen, G. Li, C. Jin, S. Liu, and T. Li, “SSD-GAN: Measuring the realness in the spatial and spectral domains,” Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell., vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 1105–1112, 2021. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v35i2.16196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Z. Pan, F. Yuan, J. Lei, W. Li, N. Ling and S. Kwong, “MIEGAN: Mobile image enhancement via a multi-module cascade neural network,” IEEE Trans. Multimed., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 519–533, 2024. doi: 10.1109/TMM.2021.3054509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Y. LeCun, C. Cortes, and C. J. C. Burges, “Dataset named ‘mnist’ dataset from Kaggle,” Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hojjatk/mnist-dataset [Google Scholar]

18. A. Krizhevsky, V. Nair, and G. Hinton, “Dataset named ‘cifar100’ dataset from Kagglehttps,” 2009. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/fedesoriano/cifar100 [Google Scholar]

19. S. Yang, P. Luo, C. C. Loy, and X. Tang, “Dataset named ‘celeba’ dataset from Kaggle,” 2015. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/jessicali9530/celeba-dataset [Google Scholar]

20. H. Xiao, K. Rasul, and R. Vollgraf, “Dataset named ‘fashion mnist’ dataset from Kaggle,” 2017. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/zalando-research/fashionmnist [Google Scholar]

21. Q. Wu, H. Deng, K. Hu, and Z. Wang, “Music source separation via hybrid waveform and spectrogram based generative adversarial network,” Multimed. Tools Appl., pp. 1–15, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s11042-024-20038-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. P. Tao and D. G. Yang, “RSC-WSRGAN super-resolution reconstruction based on improved generative adversarial network,” Signal, Image Video Process., vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 7833–7845, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s11760-024-03432-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Y. Jia, W. Yu, G. Chen, and L. Zhao, “Nighttime road scene image enhancement based on cycle-consistent generative adversarial network,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, 2024, Art. no. 14375. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-65270-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. P. Mahey, N. Toussi, G. Purnomu, and A. T. Herdman, “Generative adversarial network (GAN) for simulating electroencephalography,” Brain Topogr., vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 661–670, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s10548-023-00986-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Q. Chen, A. Ye, Y. Zhang, J. Chen, and C. Huang, “Information-minimizing generative adversarial network for fair generation and classification,” Neural Process. Lett., vol. 56, no. 1, p. 36, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s11063-024-11457-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. H. D. Nguyen-Le et al., “Generative adversarial network for newborn 3D skeleton part segmentation,” Appl. Intell., vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 4319–4333, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s10489-024-05406-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. S. F. Zhang et al., “Robust generative adversarial network,” Mach. Learn., vol. 112, no. 12, pp. 5135–5161, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s10994-023-06367-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]