Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multi-Order Neighborhood Fusion Based Multi-View Deep Subspace Clustering

1 Department of Automation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China

2 National Center of Technology Innovation for Intelligentization of Politics and Law, Beijing, 100000, China

3 Beijing Key Lab of Intelligent Telecommunication Software and Multimedia, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, 100124, China

* Corresponding Author: Boyue Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(3), 3873-3890. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.060918

Received 12 November 2024; Accepted 26 December 2024; Issue published 06 March 2025

Abstract

Existing multi-view deep subspace clustering methods aim to learn a unified representation from multi-view data, while the learned representation is difficult to maintain the underlying structure hidden in the origin samples, especially the high-order neighbor relationship between samples. To overcome the above challenges, this paper proposes a novel multi-order neighborhood fusion based multi-view deep subspace clustering model. We creatively integrate the multi-order proximity graph structures of different views into the self-expressive layer by a multi-order neighborhood fusion module. By this design, the multi-order Laplacian matrix supervises the learning of the view-consistent self-representation affinity matrix; then, we can obtain an optimal global affinity matrix where each connected node belongs to one cluster. In addition, the discriminative constraint between views is designed to further improve the clustering performance. A range of experiments on six public datasets demonstrates that the method performs better than other advanced multi-view clustering methods. The code is available at (accessed on 25 December 2024).Keywords

Clustering is the cornerstone in the domains of data mining and machine learning, which focuses on unsupervised classifying unlabeled data into the appropriate clusters based on the similarity between samples. Over the years, many advanced clustering methods (e.g., K-means clustering [1], spectral clustering [2], and subspace clustering [3]) have been proposed and widely used in many practical applications.

Nowadays, with the quick development of cameras, digital sensors, and social networks, massive data can be easily obtained from various perspectives and numerous sources, so-called multi-view data. In short, an object can be collected from different views, and each angle is regarded as a specific view that is independently used for analysis. Such as, an image can be described by various features like HOG [4], SIFT [5], and GIST [6]; videos usually contain visual frames, audio signals, and text messages; different languages can report the news; and cameras can capture an object from many angles.

Different from the single-view data, multi-view data exists the consistent redundant and supplementary information between distinct views. Therefore, how to efficiently handle the consistency and the supplementary information of each view to learn a unified expression is a critical problem.

Lately, many multi-view clustering algorithms have been researched intensively, including Multi-view graph clustering [7–10], Multi-kernel learning [11–15], and Multi-view subspace clustering [16–19]. Among them, multi-view graph clustering aims to learn a shared graph structure from different views for clustering, e.g., Wang et al. [20] proposed multi-view and multi-order structured graph learning, which introduced multiple different-order graphs into graph learning. Wang et al. [21] presented a local high-order graph learning for multi-view clustering, which uses the rotation tensor nuclear norm to exploit high-order relationships between views; Multi-kernel learning utilizes different predefined kernels to process the data of each view, then fuses these kernels in a linear or nonlinear way to form a unified kernel for clustering. Multi-view subspace clustering aims to obtain a unified latent representation reflecting the consistency across different views, which has attracted widespread research. Multi-view subspace clustering methods usually presume that a sample can be linearly represented by other samples in the same cluster, while they cannot handle the samples with non-linear structures. So, some researchers introduce kernel methods to map samples into one high-dimensional space to handle the nonlinear structure [19,22,23].

Recently, benefiting from the powerful non-linear representation and data-driven capabilities of neural networks, several multi-view deep subspace clustering algorithms have been explored [23–25] to extract the global proximity structure among latent non-linear features of samples, which receives much success for clustering tasks. Yu et al. [26] introduced contrastive learning and Cauchy-Schwarz (CS) divergence into multi-view subspace clustering. Cui et al. [27] introduced anchor graphs into deep subspace clustering networks. Wang et al. [28] proposed an attributed graph subspace clustering mode. However, there still exist two obvious drawbacks:

• The only feature reconstruction constrain in the multi-view auto-encoder framework is not sufficient to accurately reveal the intrinsic structure hidden in the original multi-view data.

• The above methods mostly exploit the first-order Laplacian matrix to guide the self-representation learning of samples while they ignore the hidden multi-order structural information of samples. High-order structures reflect the long-range neighbor relationship, which is important for mining the potential connected structure between intra-cluster samples.

Therefore, how to use the multi-order structural of the original sample for the multi-view subspace clustering task has important research significance.

In this article, we creatively present a multi-order neighborhood fusion based multi-view deep subspace clustering model to solve the above issues, which integrates the first-order and high-order Laplacian matrix of the original multi-view data into the self-expressive layer between multi-view auto-encoder framework to improve the self-expressive property. By this way, the model introduces the multi-order neighborhood relations of different views into the global consistent affinity structure learning, effectively adding some potential connections between samples in the same cluster and also reducing the connections between samples in the different clusters. Besides, the discriminative constraint is simultaneously imposed to restrict the samples belonging to different clusters.

We summarize the main contributions of this article:

• We creatively propose a multi-view deep subspace clustering network that makes full use of the multi-order proximity structures of different views, which is obviously different from the commonly used first-order Laplacian matrix based multi-view deep clustering methods [29,30];

• We design the multi-order neighborhood fusion module to construct an optimal multi-order Laplacian matrix, which constrains and maintains the inherent structure-property in the learned self-representation matrix;

• We build the discriminative regularization to constrain the samples belonging to different clusters in different views far away from each other;

• We analyze the parameter sensitivity and the convergence of the model through a series of experiments in detail, and conduct extensive experiments on six public datasets to demonstrate the superiority of the model.

The paper mainly consists of the following parts: Section 2 reviews related works. Section 3 constructs the multi-order proximity matrix. Section 4 presents the proposed multi-order neighborhood fusion based multi-view clustering model in detail. Section 5 conducts the experiments and reviews relevant analysis. Section 6 summarizes the work and looks forward to future work.

This section briefly reviews the research related to multi-view subspace clustering.

2.1 Multi-View Subspace Clustering (MVSC)

The MVSC targets to study a self-representation matrix crossing latent spaces of different views, then conduct the clustering algorithm on it. Gao et al. [16] initially extended the single-view subspace clustering to MVSC, which conducts the subspace clustering on each view and unifies them into an indicator matrix. Cao et al. [17] further considered diversity to get the supplementary information of multi-view data, where the Hilbert Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) was used as a diversity term. Zhang et al. [31] considered the latent representation from all views.

To solve the nonlinear features of multi-view data, a few researchers conduct the kernel model to multi-view subspace clustering [19,22,32]. Recently, Zhang et al. [33] designed a one-step clustering model to learn the unified representation. Kang et al. [34] presented the novel multi-view subspace clustering method, which uses the bipartite graph to handle large-scale data.

2.2 Multi-View Deep Subspace Clustering (MVDSC)

The MVDSC targets to study a self-representation matrix of multi-view data through neural networks. Andrew et al. [35] initially presented the deep canonical correlation analysis method (DCCA) that utilizes the neural network to learn the nonlinear mapping between two views. On this basis, Wang et al. [36] introduced the auto-encoder into above DCCA, which jointly optimizes the representation learning and the reconstruction loss.

However, such methods are limited to the two-view case and cannot handle data with three or more views. In response to this, Xu et al. [37] presented the deep multi-view concept learning method, which distinguishes the consistent and supplementary information in the multi-view data by performing the non-negative matrix factorization for each view. Inspired by deep subspace clustering and multi-modal data analysis, Abavisani et al. [38] proposed a deep multi-modal subspace clustering network to investigate various fusion methods and the corresponding network architectures. Zhu et al. [24] integrated the universality and diversity networks into a unified framework that learns the self-representation matrices in an end-to-end manner. Gao et al. [39] proposed a cross-modal subspace network architecture for DCCA, which introduces a self-expression layer in above the DCCA network to make full use of the correlation information between different modalities. Wang et al. [30] combined the global and local structure of all views with the self-representation layers to learn a unified representation matrix. Zheng et al. [40] embedded first-order neighbor matrices of different views into the multi-view representation learning. Guo et al. [41] collected the multi-view images of each action and designed the proper multi-view subspace clustering analysis method.

In the above, existing MVDSC methods seldom consider the structure information of each view or only exploit the first-order neighbor relationship, which results in poor representation capability.

3 Multi-Order Proximity Matrix

The first-order graph structure of origin data reflects the physical connection relationship between samples. As shown in Fig. 1a, sample A has three neighbors B, C, and D. The second-order proximity matrix describes the potential and deeper connection relationship, that is, samples with more shared neighbors are more likely to be the same cluster. Fig. 1b indicates that samples B, C and D have the same neighbor A, so they are more likely to belong to the same cluster. Based on the same assumptions, we explore the high-order proximity matrix to get more comprehensive and potential connection information between samples in complex scenes.

Figure 1: We briefly describe the multi-order structure information. First-order structure reflects the feature similarity between samples, and second-order structure displays the neighbor similarity between samples

Given the multi-view data

where

In general, the first-order proximity matrix reflects the feature similarity between nodes in the graph, while nodes with more shared neighbors should tend to be similar. So, the second-order proximity reflects the neighbor similarity between nodes, which is defined in the following.

Definition 1. [42] The similarity between the neighborhood structures of two vertices (u, v) is defined as their second-order proximity.

Therefore, the second-order proximity matrix

Then, the second-order Laplacian matrix can be easily constructed by,

where the diagonal element

Similarly, we extend the above second-order proximity matrix to the high-order proximity matrix to the high-order proximity matrix

which is exploited in the following.

Our method can be introduced from the following three parts, including multi-view encoder and decoder networks, multi-order neighborhood fusion, and discriminative learning between views. Fig. 2 shows the framework of our model.

Figure 2: A brief illustration of the model. Our model mainly includes three parts: multi-view encoder and decoder module, multi-order neighborhood fusion module, and discriminative learning between each view. Moreover,

Existing multi-view deep subspace clustering methods are sensitive to the quality of the latent space representation learned by the multi-view auto-encoder due to the deficiency of supervised information. To deal with this problem, some researches introduce the Laplacian regularization into the self-representation affinity matrix learning, while the performance may be limited by the predefined first-order Laplacian matrix. We owe to the first-order Laplacian matrix only reflects the local pair-wise relationship between samples, and is easily influenced by noise. To solve such issues, we propose to embed the multi-order Laplacian matrices of different views into the self-expressive layer to supervise the model learning. We briefly introduce its two main motivations:

• We design a multi-order neighborhood fusion module to obtain an ideal multi-order Laplacian matrix that guides the global unified affinity matrix learning, which mines more potential connections between samples and effectively eliminates the negative impacts caused by wrong connections in the first-order Laplacian matrix.

• We additionally introduce the discriminative constraints to capture the supplementary information from multi-view data.

Given the multi-view data of

Each view has its own encoder network. With the v-th view input

4.2.2 Self-Representation Layer

The self-representation layer is shared by all encoder and decoder networks, which learns the unified self-representation matrix

Each view has its decoder network that is the opposite architecture to the previous encoder network. The v-th decoder network can be denoted as

The objective function is shown as follows:

where the reconstruction loss

4.3 Multi-View Encoder and Decoder Networks

For the reconstruction loss

and

Generally speaking,

4.4 Multi-Order Neighborhood Fusion and Decoder Networks

The MVDSC methods rarely learn the latent structure information in the multi-view data, especially the hidden high-order neighbor relationship between samples, which results in poor structure capture capability. We believe the high-order proximity matrices can better mine the deeper connected relationship between samples. Motivated by the multi-order proximity strategy, we design a multi-order neighborhood fusion module as shown in Fig. 3, which fuses the structure of different orders of each view data.

Figure 3: The brief illustration of the multi-order neighborhood fusion. For the multi-view data

For the original multi-view data

where

In cross-view fusion, the strong connections in one graph can be transferred to other corresponding graphs. With the help of complementary information, the similarity between samples in the same cluster should be enhanced, while the wrong connections in one graph may be disconnected or weakened. Besides, the corresponding high-order Laplacian matrix is defined as,

where the diagonal element

To fuse the advantages of different order data structures, we learn an optimal and unified Laplacian matrix from the above first-order to high-order Laplacian matrix, so-called multi-order neighborhood relationship. So, the multi-order fusion loss

where

Through the multi-order neighborhood fusion loss

To obtain an optimal self-representation affinity matrix, we integrate the multi-order graph structure information into the self-expressive layer. The learned optimal multi-order Laplacian matrix guides the learning procedure of the self-representation matrix

where the

4.5 Discriminative Learning between Views

To study the supplementary and discriminative information between different views, the discriminative constraint

Overall, after substituting above losses into Formula (5), it can be defined as follows:

which jointly optimizes the variables,

The training procedure mainly consists of the following two steps.

Pre-training the multi-view auto-encoder network. Given the multi-view data

Updating the whole network parameters using the Formula (13). Specifically, the parameters of encoder and decoder learned in the first step are used to initialize the network. Then, the parameters

Then, we obtain the unified self-representation matrix

Finally, the spectral clustering is performed on the matrix

Before we analyze the network complexity, we first present the necessary symbols below. For the multi-view data

According to Algorithm 1, the computational complexity primarily consists of Steps 1, 3 and 5. In Step 1, the complexity is

We implement a range of experiments to validate the efficiency of our method.

We choose six public and commonly used datasets from various applications, including face recognition, sensor network, gene lineage and natural language processing. The brief statistics information of the six datasets is outlined in Table 1, where

• BUAA dataset [43] is composed of

• MSRCV dataset [44] is composed of

• CMU-PIE dataset [45] has a total of 41,386 facial images of

• Yale Face dataset [46] is composed of

• SensIT Vehicle dataset [47] collects from the Wireless Distributed Sensor Network. It utilizes seismic sensors and acoustic to record different signals, which contains

• Prokaryotic Phyla dataset [48] is from the prokaryotic species, describing by protein composition, textual data, genetic information. It contains

To fairly consider the clustering efficiency of the model, we choose one single-view clustering baseline and nine advanced multi-view clustering baselines as comparison methods.

• K-means [1] is applied to each view of multi-view data separately, and we report the best clustering results here.

• Auto-Weighted Multiple Graph Learning (AMGL) [7] is a multi-graph learning framework with parameter-free, that assigns appropriate weights to each graph during learning.

• Multi-View Learning with Adaptive Neighbors (MLAN) [49] constructs one initial graph for different view, and then fuses it to develop a unified graph for clustering.

• Latent Multi-View Subspace Clustering (LMSC) [50] utilizes the latent representation of each view to cluster data points.

• Deep Multi-Modal Subspace Clustering Networks (DMSCN) [38] contain three parts, i.e., multi-modal encoder, multi-modal decoder and self-expression layer. It is an important baseline.

• Graph-based Multi-View Clustering (GMC) [51] is a multi-view fusion strategy, in which the learned unified graph optimizes the initial graph of each view.

• Large-scale Multi-View Subspace Clustering in Linear Time (LMVSC) [34] aims to obtain a shared binary graph for spectral clustering tasks.

• Deep Multi-View Subspace Clustering with Unified and Discriminative Learning (DMSC-UDL) [30] combines the global structure with the local structure of multi-view data to learn a better-unified connection matrix.

• Multi-View Subspace Clustering Networks with Local and Global Graph Information (MSCNLG) [29] ingrates the local and global graph structure of multi-view data to learn a unified representation. It is an important baseline.

Three common metrics are chosen [52], including NMI, ACC, and ARI, to evaluate the performance of our model. NMI is an information theoretic metric based on ground-truth class labels and cluster labels, and normalizes the entropy of each class. ACC represents the proportion of correctly clustered samples to the total number of samples. ARI reflects the degree of overlap between the cluster labels and the true labels of samples. In all metrics, higher scores represent better performance.

We use the deep learning toolbox Tensorflow 1.15 to implement the model, and conduct all experiments on the Ubuntun 18.04 platform, with NVIDIA RTX 2080s and 128 GB memory size.

The encoder and decoder networks of the model respectively contain 3 layers, and the nonlinear activation function is RELU. The Adam optimizer is selected to train the network, and the learning rate is set to 0.001. Three important parameters, i.e.,

For the BUAA dataset, the dimensions of encoder and decoder networks are set to 100 − 128 − 128 − 128 − 100 and 100−128−128 − 128 − 100, respectively, where

We still adhere to the parameter settings in the original manuscripts for all comparison methods while using the original codes provided on the authors’ homepages. For LMSC, we set the latent representation dimension to 100, and search the optimal λ in the range {0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100}. For DMSCN, we tune the optimal parameters

All experiments are conducted 20 times to confirm the generality and equity, and the average values and square differences are calculated as the final results.

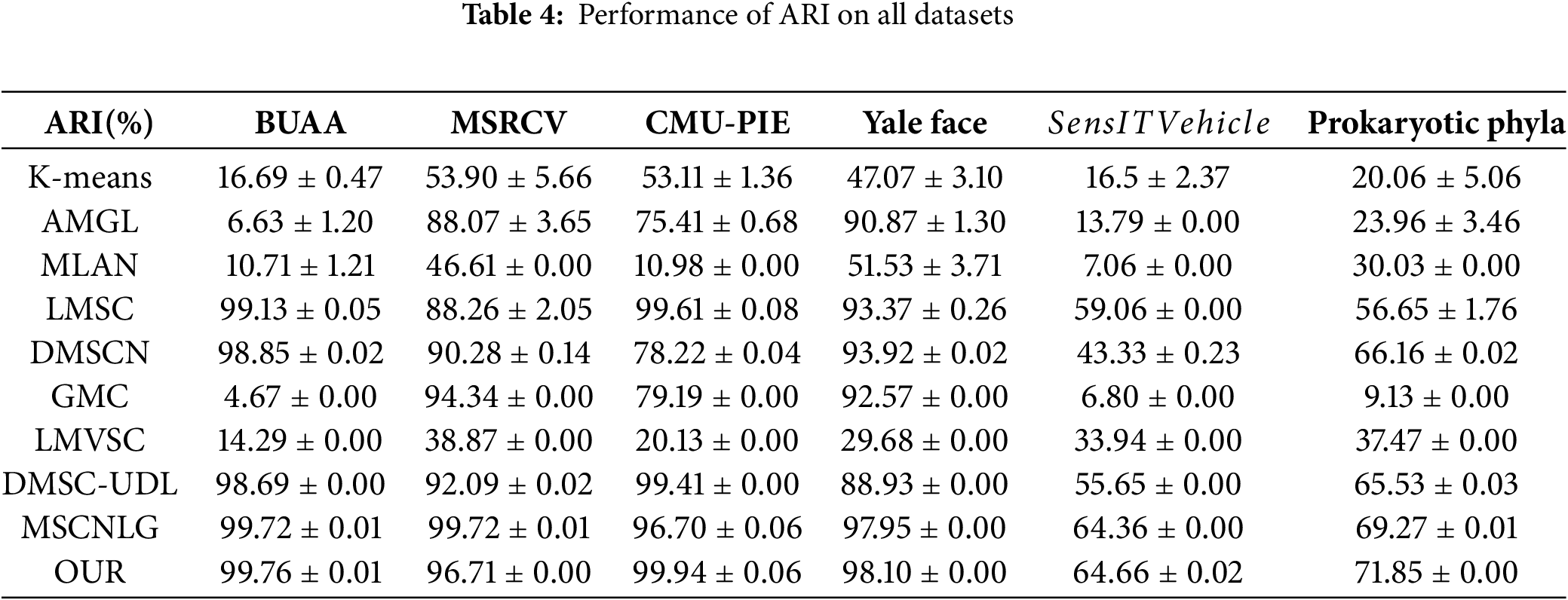

Tables 2–4 summarize the performance of NMI, ACC and ARI on six public datasets, respectively. Besides, we use bold and underline to show the best and second-best results.

Obviously, in most cases, the proposed model provides the best results on all datasets. In particular, the clustering results on CMU-PIE and Yale Face datasets are close to 100%. The following conclusions are drawn from such tables:

1. From a holistic perspective, deep multi-view methods consistently outperform traditional multi-view methods. The neural network adaptively learns the nonlinear and deeper feature information from the original data, so that the neural network improves the clustering results.

2. Our model notably outperforms the K-means clustering results on all datasets, which demonstrates that the model extracts more heterogeneous information from different views and properly fuses it.

3. Compared with several multi-view deep clustering methods learning the unified self-representation matrix from multi-view data, i.e., DMSCN and DMSC-UDL, our proposed model achieves the obvious promotions on BUAA, MSRCV, CMU-PIE and Yale Face datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of the fused multi-order graph structure information.

4. In certain aspects, the K-means clustering is even marginally superior to the multi-view methods, illustrating that several views contain the obvious discrimination information and how to explore the complementary information between views effectively is also a critical problem.

In general, the experiment results provide a complete verification of the excellence of the model. Unlike other multi-view deep subspace clustering methods, our model incorporates both the first-order and the hidden high-order neighborhood connection information in the unified self-representation affinity matrix learning, which notably improves the clustering results.

In this section, we analyze the convergence of the model and visualize the objective function value of each iteration on six public datasets in Fig. 4, where the x-axis represents the amount of iterations and the y-axis represents the objective function value. We can see that for the entire dataset, our model converges quickly in less than 100 epochs.

Figure 4: The convergence curves of the model for all datasets

As we mentioned before, three hyper-parameters, i.e.,

Figure 5: The parameter analysis of the model on Yale Face and MSRCV datasets

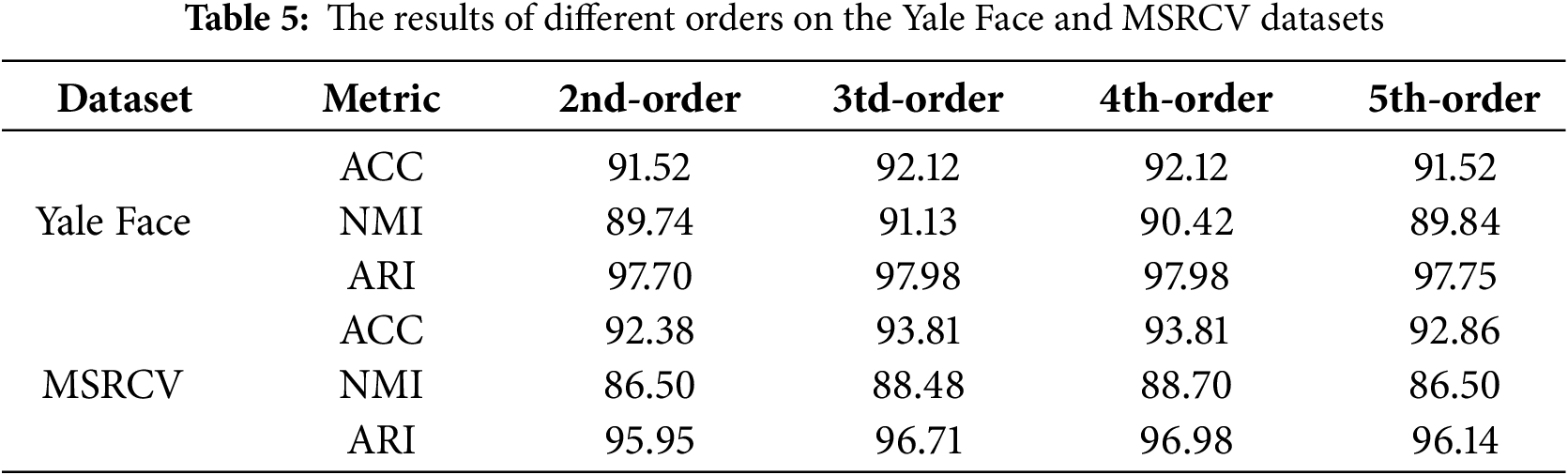

To explore the effects of different-order neighborhood information, we conduct experiments on 2nd-order, 3rd-order, 4th-order and 5th-order proximity matrices on Yale Face and MSRCV datasets, respectively. From Table 5 we can see, when the order of the proximity matrix increases, the range of the neighborhood becomes large and the clustering performance of the corresponding model begins to decline. Finally, we set the order number to 3 in all experiments.

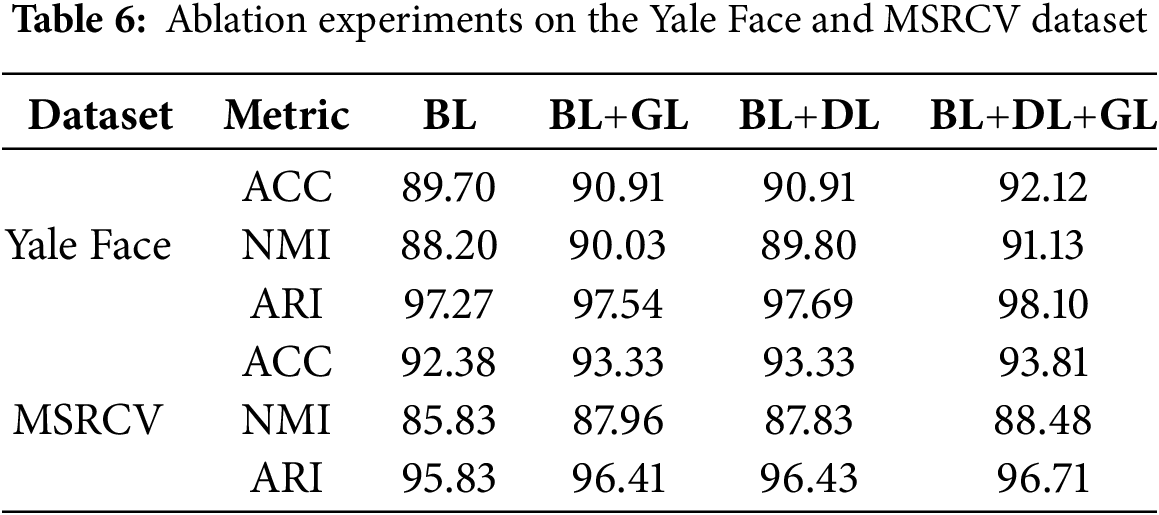

To further test the efficiency of the multi-order neighborhood information and the discriminative constraint, we implement ablation experiments on Yale Face and MSRCV datasets. The ablation experiment results as shown in Table 6.

• BL means the baseline, i.e., the multi-view encoder and decoder networks (

• GL denotes the multi-order neighborhood fusion mechanism (

• DL represents the discriminative constraint (

From Table 6, we can see that both multi-order neighborhood fusion mechanism and discriminative constraint obviously improve the clustering performance of the proposed model. Besides, by combining two designs, the proposed model improves NMI by about 3% compared to the baselines.

In this article, we creatively design a multi-order neighborhoods fusion based multi-view deep subspace clustering model. By integrating the deep connection relationship of different order neighborhoods to guide the learning of one ‘‘good” unified self-representation for clustering tasks. An additional discrimination constraint is introduced to consider the supplementary information between views. It is worth noting that we showed that fusing the multi-order proximity matrix of different views can not only maintain the underlying structure but also improve the clustering performance, and creatively proposed a multi-order neighborhoods fusion method. A set of ablation experiments is designed to demonstrate the stability and efficiency of the model. A range of experiments verify that our method performs better than the advanced multi-view clustering methods. The weakness of our method is that the complexity is still a bit high, and future directions include reducing the computational overhead and adapting to incomplete multi-view clustering.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely appreciate every anonymous reviewer who generously invested their valuable time and energy. Their profound professional insights and constructive suggestions played a vital role in improving the academic level and research quality of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: The research project is partially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3304600).

Author Contributions: The authors affirm their respective contributions to the manuscript as detailed below: study conception and design: Kai Zhou and Boyue Wang; code and experiment: Kai Zhou and Yanan Bai; draft manuscript preparation: Kai Zhou, Yanan Bai, Boyue Wang and Yongli Hu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used within this article are accessible to interested parties by contacting the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Macqueen J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In: Proceedings of 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; 1967; Oakland, CA, USA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

2. A Ng, M Jordan, Y Weiss. On spectral clustering: analysis and an algorithm In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 14; Phoenix, Arizona, USA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

3. Elhamifar E, Vidal R. Sparse subspace clustering: algorithm, theory, and applications. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2013;35(11):2765–81. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2013.57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dalal N, Triggs B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In: 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05); 2005; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 886–93. [Google Scholar]

5. Lowe DG. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int J Comput Vis. 2004;60:91–110. doi:10.1023/B:VISI.0000029664.99615.94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Oliva A, Torralba A. Modeling the shape of the scene: a holistic representation of the spatial envelope. Int J Comput Vis. 2001;42:145–75. doi:10.1023/A:1011139631724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang R, Nie F, Wang Z, Hu H, Li X. Parameter-free weighted multi-view projected clustering with structured graph learning. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2019;32(10):2014–25. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2019.2913377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang S, Xu Z, Tsang IW, Kang Z. Auto-weighted multi-view co-clustering with bipartite graphs. Inf Sci. 2020;512:18–30. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2019.09.079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhan K, Nie F, Wang J, Yang Y. Multiview consensus graph clustering. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2019;28(3):1261–70. doi:10.1109/TIP.2018.2877335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Hu Y, Song Z, Wang B, Gao J, Sun Y, et al. AKM3C: adaptive k-multiple-means for multi-view clustering. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2021;31(11):4214–26. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2020.3049005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lu Y, Wang L, Lu J, Yang J, Shen C. Multiple kernel clustering based on centered kernel alignment. Pattern Recognit. 2014;47(11):3656–64. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2021.3119956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tzortzis G, Likas A. Kernel-based weighted multi-view clustering. In: 2012 IEEE 12th International Conference on Data Mining; 2012; Brussels, Belgium. p. 675–84. [Google Scholar]

13. Liu J, Cao F, Gao X, Yu L, Liang J. A cluster-weighted kernel k-means method for multi-view clustering. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020; New York City, New York, NY, USA. p. 4860–7. [Google Scholar]

14. Zhang P, Yang Y, Peng B, He M. Multi-view clustering algorithm based on variable weight. In: International Joint Conference on Rough Sets; 2017; Springer; Olsztyn, Poland; p. 599–610. [Google Scholar]

15. Lan M, Meng M, Yu J, Wu J. Generalized multi-view collaborative subspace clustering. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2021;32(6):3561–74. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2021.3119956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gao H, Nie F, Li X, Huang H. Multi-view subspace clustering. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2015; Santiago, Chile; p. 4238–46. [Google Scholar]

17. Cao X, Zhang C, Fu H, Liu S, Zhang H. Diversity induced multi-view subspace clustering. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2015; Boston, MA, USA; p. 586–94. [Google Scholar]

18. Luo S, Zhang C, Zhang W, Cao X. Consistent and specific multi-view subspace clustering. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018; New Orleans, LA, USA. Vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

19. Zhang G-Y, Chen X-W, Zhou Y-R, Wang C-D, Huang D, He X-Y. Kernelized multi-view subspace clustering via auto-weighted graph learning. Appl Intell. 2022;52(1):716–31. [Google Scholar]

20. Wang R, Wang P, Wu D, Sun Z, Nie F, Li X. Multi-view and multi-order structured graph learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(10):14437–48. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3279133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wang Z, Lin Q, Ma Y, Ma X. Local high-order graph learning for multi-view clustering. IEEE Trans Big Data. 2024 Jan;PP:1–14. doi:10.1109/TBDATA.2024.3433525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sun M, Wang S, Zhang P, Liu X, Guo X, Zhou S, et al. Projective multiple kernel subspace clustering. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2021;24(4):2567–79. doi:10.1109/TMM.2021.3086727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ji P, Zhang T, Li H, Salzmann M, Reid I. Deep subspace clustering networks. In: 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 20172017; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

24. Zhu P, Yao X, Wang Y, Hui B, Du D, Hu Q. Multi-view deep subspace clustering networks. arXiv:1908.01978. 2019. [Google Scholar]

25. Chen Z, Ding S, Hou H. A novel self-attention deep subspace clustering. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2021;12(8):2377–87. doi:10.1007/s13042-021-01318-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yu X, Yi J, Chao G, Chu D. Deep contrastive multi-view subspace clustering with representation and cluster interactive learning. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;37(1):1–12. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2024.3484161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cui C, Ren Y, Pu J, Pu X, He L. Deep multi-view subspace clustering with anchor graph. arXiv:2305.06939, 2023. [Google Scholar]

28. Wang L, En Z, Wang S, Guo X. Attributed graph subspace clustering with graph-boosting. In: Asian Conference on Machine Learning; 2023; Istanbul, Turkey: PMLR. p. 723–38. [Google Scholar]

29. Zheng Q, Zhu J, Ma Y, Li Z, Tian Z. Multi-view subspace clustering networks with local and global graph information. Neurocomputing. 2021;449(4):15–23. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.03.115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang Q, Cheng J, Gao Q, Zhao G, Jiao L. Deep multi-view subspace clustering with unified and discriminative learning. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2020;23:3483–93. doi:10.1109/TMM.2020.3025666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang C, Fu H, Hu Q, Cao X, Xie Y, Tao D, et al. Generalized latent multi-view subspace clustering. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2018;42(1):86–9. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2877660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang G, Zhou Y, He X, Wang C, Huang D. One-step kernel multi-view subspace clustering. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;189(1):105–26. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang P, Liu X, Xiong J, Zhou S, Zhao W, Zhu E, et al. Consensus one-step multi-view subspace clustering. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2020;34(10):4676–89. [Google Scholar]

34. Kang Z, Zhou W, Zhao Z, Shao J, Han M, Xu Z. Large-scale multi-view subspace clustering in linear time. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020; New York City, New York, NY, USA. p. 4412–9. [Google Scholar]

35. Andrew G, Arora R, Bilmes J, Livescu K. Deep canonical correlation analysis. In: International Conferenceon Machine Learning; 2013; Atlanta, GA, USA: PMLR. p. 1247–55. [Google Scholar]

36. Wang W, Arora R, Livescu K, Bilmes J. On deep multi-view representation learning. In: International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015; Lille, France: PMLR. p. 1083–92. [Google Scholar]

37. Xu C, Guan Z, Zhao W, Niu Y, Wang Q, Wang Z. Deep multi-view concept learning. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-18); 2018; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 2898–904. [Google Scholar]

38. Abavisani M, Patel V. Deep multimodal subspace clustering networks. IEEE J Sel Top Signal Process. 2018;12(6):1601–14. doi:10.1109/JSTSP.2018.2875385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Gao Q, Lian H, Wang Q, Sun G. Cross-modal subspace clustering via deep canonical correlation analysis. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020. p. 3938–45. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i04.5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zheng Q, Zhu J, Li Z, Tang H. Graph-guided unsupervised multiview representation learning. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2022;33(1):146–59. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2022.3200451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Guo D, Li K, Hu B, Zhang Y, Wang M. Benchmarking micro-action recognition: dataset, method, and application. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2024;PP(99):1. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3358415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhou S, Liu X, Liu J, Guo X, Zhao Y, Zhu E, et al. Multi-view spectral clustering with optimal neighborhood laplacian matrix. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020; New York City, New York, NY, USA. p. 6965–72. [Google Scholar]

43. Shao M, Fu Y. Hierarchical hyper lingual-words for multi-modality face classification. In: 2013 10th IEEE International Conference and Workshops on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG); 2013; Shanghai, China. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

44. Xu J, Han J, Nie F. Discriminatively embedded k-means for multi-view clustering. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 5356–64. [Google Scholar]

45. Sim T, Baker S, Bsat M. The CMU pose, illumination and expression database of human faces. Carnegie Mellon University. Technical Report CMU-RI-TR-OI-02, 2001. [Google Scholar]

46. Cai D, He X, Hu Y, Han J, Huang T. Learning a spatially smooth subspace for face recognition. In: 2007 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2007; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

47. Chang C-C. A library for support vector machines. 2001 [cited 2024 Nov 28]. Available from: http://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/. [Google Scholar]

48. Brbi’c M, Piškorec M, Vidulin V, Kriško A, Šmuc T, Supek F. The landscape of microbial phenotypic traits and associated genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(21):gkw964. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Nie F, Cai G, Li X. Multi-view clustering and semi-supervised classification with adaptive neighbours. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017; San Francisco, CA, USA. Vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

50. Zhang C, Hu Q, Fu H, Zhu P, Cao X. Latent multi-view subspace clustering. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 4279–87. [Google Scholar]

51. Wang H, Yang Y, Liu B. GMC: graph-based multi-view clustering. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2019;32(6):1116–29. [Google Scholar]

52. Jia Y, Liu H, Hou J, Kwong S, Zhang Q. Multi-view spectral clustering tailored tensor low-rank representation. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2021;31(12):4784–97. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools