Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Efficient Parameterization for Knowledge Graph Embedding Using Hierarchical Attention Network

1 Master Program of Digital Innovation, Tunghai University, Taichung, 40704, Taiwan

2 Department of Statistics, Feng Chia University, Taichung, 40724, Taiwan

3 College of Integrated Health Sciences and the AI Plus Institute, The University at Albany, State University of New York (SUNY), Albany, NY 12222, USA

* Corresponding Author: Ching-Sheng Lin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(3), 4287-4300. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.061661

Received 29 November 2024; Accepted 01 February 2025; Issue published 06 March 2025

Abstract

In the domain of knowledge graph embedding, conventional approaches typically transform entities and relations into continuous vector spaces. However, parameter efficiency becomes increasingly crucial when dealing with large-scale knowledge graphs that contain vast numbers of entities and relations. In particular, resource-intensive embeddings often lead to increased computational costs, and may limit scalability and adaptability in practical environments, such as in low-resource settings or real-world applications. This paper explores an approach to knowledge graph representation learning that leverages small, reserved entities and relation sets for parameter-efficient embedding. We introduce a hierarchical attention network designed to refine and maximize the representational quality of embeddings by selectively focusing on these reserved sets, thereby reducing model complexity. Empirical assessments validate that our model achieves high performance on the benchmark dataset with fewer parameters and smaller embedding dimensions. The ablation studies further highlight the impact and contribution of each component in the proposed hierarchical attention structure.Keywords

Knowledge graphs (KGs) store human knowledge by encoding millions of relational facts as triples, represented as (head entity, relation, tail entity) [1]. Numerous real-world KGs, such as Freebase [2], YAGO [3] and DBpedia [4], have been developed and widely utilized as foundational knowledge resources not only in natural language processing tasks [5,6] but also in computer vision studies [7,8]. In addition to the aforementioned general-purpose KGs, domain-specific KGs in fields like agricultural KGs [9] and Social-Impact Funding KGs [10] are increasingly explored to provide support in various areas.

Although KGs typically contain vast amounts of entities, they are often built from limited data sources and rely on automated extraction techniques, leading to the potential omission of certain real-world relationships. This challenge becomes particularly evident as the scale of the KG expands, where missing relationships may become even more pronounced. For example, DBpedia is constructed based on Wikipedia that transforms information from Wikipedia into RDF format, featuring approximately 5 million entities, 700 different types of relationships, and over 500 million triples. It is reported that over 65% of entities categorized as “person” in DBpedia lack the relationship attribute of “birthplaces” [11]. Since the incompleteness significantly impacts the quality of downstream applications, it is essential to implement strategies that can enhance the comprehensiveness of knowledge bases. Knowledge graph embedding (KGE) has been proposed as a robust solution, which utilizes low-dimensional representations of entities and relations to transform complex knowledge into more manageable forms [12].

Among leading KGE approaches, entities and relations are often embedded in the dimensional spaces ranging from 200 to 500 dimensions to enhance prediction accuracy for knowledge graph inference tasks [13]. This requirement to assign a unique vector for each element causes a linear increase in parameters and poses significant scalability challenges as the number of elements grows.

Recent parameter-efficient approaches in KGs representation have introduced methods for reducing model complexity and embedding dimensions by utilizing only a small subset of entities [14,15]. In these methods, entities for embedding are chosen randomly beforehand, and rather than independently embedding each entity, the model leverages specific types of distinguishing information to encode all entities. In light of this, we introduce a hierarchical attention mechanism to optimize the embedding process. This mechanism integrates attention within each distinct information module, enabling the model to dynamically prioritize the most critical aspects of diverse information types. Moreover, a final attention strategy seamlessly combines outputs across modules within the GNN framework, resulting in a hierarchically enriched embedding that elevates the effectiveness of KGE. This multi-layered attention framework not only mitigates parameter dependence on the total number of entities but also significantly enhances the model’s adaptability and interpretability, delivering a more parameter-efficient and expressive representation of KGs.

We organize the paper as follows. Section 2 provides various research fields and papers related to our work. Section 3 provides a detailed discussion of the proposed network and algorithm. In Section 4, experimental assessments are conducted on the public dataset to measure the effectiveness of our model and discuss the results further. Finally, we make some conclusions and outline potential directions for future research.

In this section, we review several research fields relevant to our work, including the knowledge graph embedding, knowledge distillation and parameter-efficient knowledge graph embedding.

Knowledge graphs organize information and knowledge into entities, attributes, and relationships to facilitate effective knowledge management and semantic understanding in various domains. It is commonly expressed as a triplet (h, r, t), where h denotes the head entity, t represents the tail entity, and r indicates the relationship connecting the two entities. For applying knowledge graphs to downstream tasks including question answering [16] and recommendation systems [17], knowledge graph embedding techniques are focused on developing approaches to encode entities and relations from a knowledge graph into continuous vector spaces, enabling efficient knowledge inference, reasoning, and predictive analytics in knowledge-driven applications. Various knowledge graph embedding methods have been proposed to improve the generalizability and transferability [18].

The distance-based methods encode the triple (h, r, t) into embedding spaces and access the distance between h and t as a measure of relational similarity. TransE [19] is a classic distance-based model designed to learn entity representations by modelling relations as translations between r and t. The RotatE [20] technique represents relations as rotations in the complex vector space, enabling the capture of both the directional and symmetric patterns. HAKE [21] takes into account the hierarchical nature of elements within the knowledge graph by leveraging polar coordinates to effectively disseminate hierarchical knowledge within the embeddings.

The semantic matching-based methods evaluate the likelihood of a triple by aligning latent semantics within the embedding space [22]. ComplEx [23] enhances the bilinear product score by extending it to the complex vector space, providing more effective modeling of antisymmetric relations. TuckER [24] extends the semantic matching model by employing Tucker decomposition, which factorizes entity and relation embeddings into multiple components. It encodes symbolic triples through tensor products of these factors, enabling efficient relational reasoning.

DynaSemble leverages textual models that utilize descriptions of textual entities, alongside structure-based models that capitalize on the connectivity framework of the Knowledge Graph [25]. TCompoundE employs composite geometric operations, including scaling and translation, to efficiently handle both temporal and relational information within temporal knowledge graphs [26]. GradPath utilizes Gradient Rollback during training to generate faithful explanation paths, which enhance the probability of the triple prediction by mimicking human-like reasoning processes [27].

In recent years, knowledge distillation has been extensively studied and the research directions can be categorized into three groups: response-based, feature-based and relation-based, depending on the knowledge being distilled [28–30].

Response-based distillation refers to a technique aimed at distilling the output value of the teacher model to guide and instruct the output of the student model. A neural network-based framework is proposed to transfer knowledge from a complex teacher neural network to a simpler student network by mimicking the final soft target distributions of the teacher model [31]. WSLD goes one step further to propose weighted soft labels for the purpose of handling the bias-variance tradeoff [32]. Feature-based distillation enables the student model to acquire richer semantic information across intermediate hidden layers of the teacher model, addressing the issue of response-based distillation’s focus solely on learning the final layer’s output. NST proposes a technique for learning similar neuron activations by minimizing the Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) metric between the teacher and student distributions [33]. SemCKD utilizes an attention mechanism to automatically allocate appropriate target layers of the teacher model to each student layer, thereby enabling more effective cross-layer supervision over the training process [34]. Unlike response-based and feature-based methods which explore the specific layer outputs between the teacher and student model from an individual data instance, relation-based methods investigate correlations or dependencies between various layers or distinct data samples. A novel perspective, review mechanism, employs multiple layers in the teacher model to supervise a single layer in the student model [35]. CIRKD integrates structured pixel-to-pixel and pixel-to-region relationships across entire images into distillation losses. It enhances the student network’s capacity to reproduce the structured semantic relationships exhibited by the teacher network [36].

2.3 Parameter-Efficient Knowledge Graph Embedding

Knowledge graph embedding methods encounter scalability challenges because the number of parameters increases linearly with the entity count [14]. This will cause difficulties in its applications, such as deploying it on edge devices. Several studies concentrate on utilizing various methods to reduce parameters of entity representations including knowledge graph distillation, quantization and compositional methods.

Knowledge graph distillation-based methods transfer expertise from complex, high-dimensional embeddings into simplified, low-dimensional entity representations. Mulde is a novel iterative knowledge distillation framework with multiple low-dimensional teacher hyperbolic KGE models and two student networks, Junior and Senior, where the Junior actively queries teachers based on preliminary predictions and the Senior distills teachers’ knowledge adaptively to train the Junior [1]. Dualde uses an adaptive soft label evaluation method that assigns each triple with different soft and hard label weights [37]. It is then trained by a two-stage distillation approach where the first stage learns from the static teacher model and the second stage makes the teacher fit a soft label produced by the student to improve the distillation effect. Quantization-based approaches compress the continuous embedding vectors into a discrete codebook of vectors that can be efficiently stored while preserving prediction accuracy. TS-CL is a pioneer work in this field by learning an autoencoder-like network where a discretization function is utilized to convert continuous entity embeddings into discrete codes and a reverse discretization function is employed to revert the process [38]. LightKG represents entity embeddings by combing codewords from various codebooks [39]. Furthermore, a novel dynamic negative sampling method is proposed to improve LightKG’s effective training. NodePiece [40] and EARL [15] are two well-known compositional methods. NodePiece is an approach to tokenize nodes in a knowledge graph into combinations of a small set of anchor nodes and relations, where the anchor vocabulary is much smaller than the total number of nodes. EARL employs an encoding process that is agnostic to entities, capturing their distinguishable information within the embeddings.

A knowledge graph is represented by G = (E, R, T) where E is the entity set, R is the relation set and T = {(h, r, t) | h, t

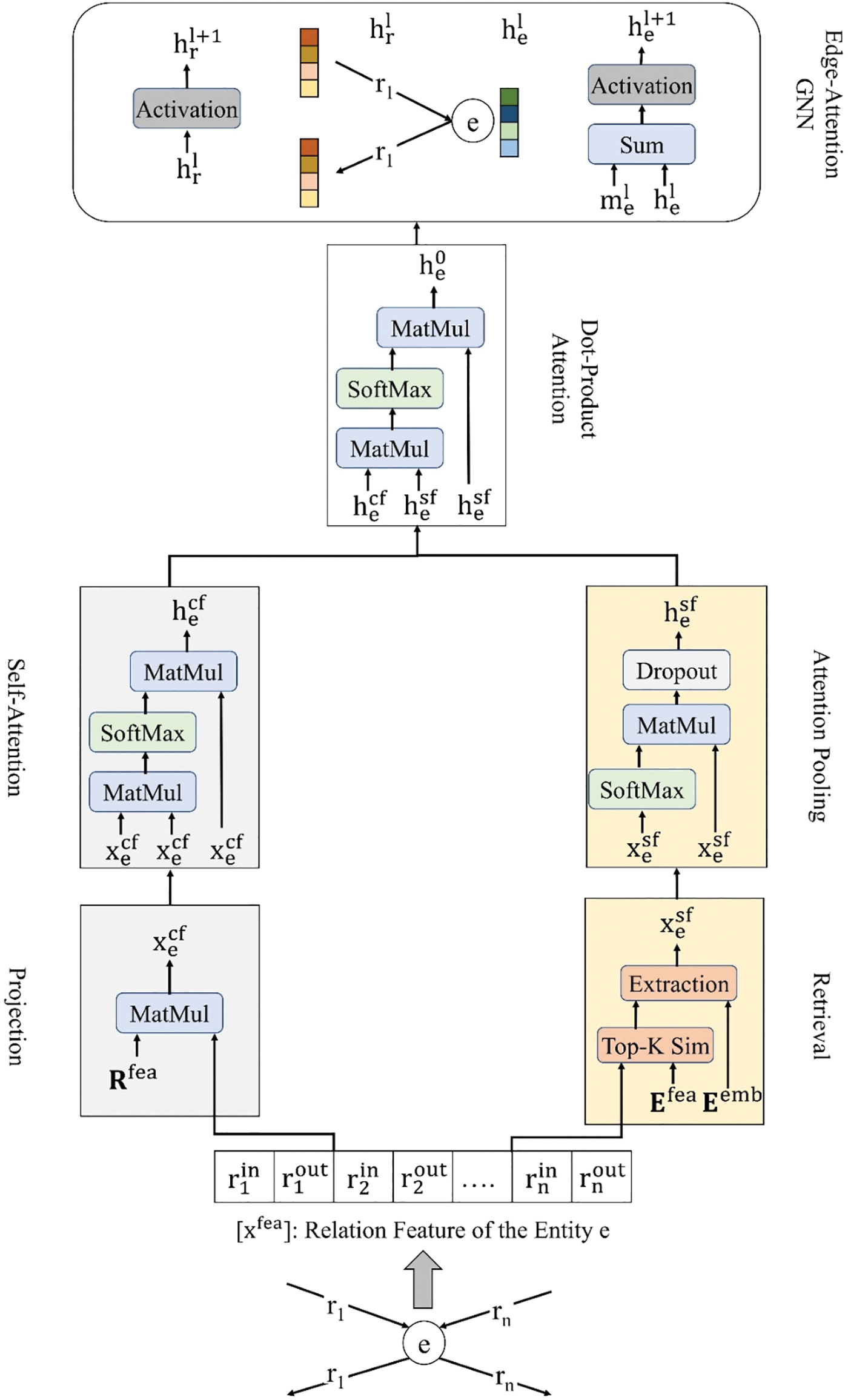

In the proposed model as shown in Fig. 1, we aim to learn embeddings exclusively for a randomly reserved subset of entities with the corresponding embeddings

Figure 1: The structure of the proposed model

3.2 Proposed Network Architecture

For each input entity

where

The next part of the network involves finding similar entities for

where

The final part, similar to previous research [15,42], employs a GNN to embed the KG in order to capture multi-hop dependencies within the graph. Before starting the GNN process, the dot-product attention is applied to

where

where

The entity representation of e and the relation representation of r in the GNN are then updated as follows, respectively.

where

The concept of the KGE is to optimize the embeddings of entities and relations by leveraging a scoring function and a loss technique. For each fact triple

Negative sampling has been shown to be highly effective for learning word embeddings [43]. The self-adversarial negative sampling technique in RotatE extends negative sampling approach to KGE tasks by dynamically generating negative samples based on the current entity and relation embeddings. The loss function is defined as follows:

where

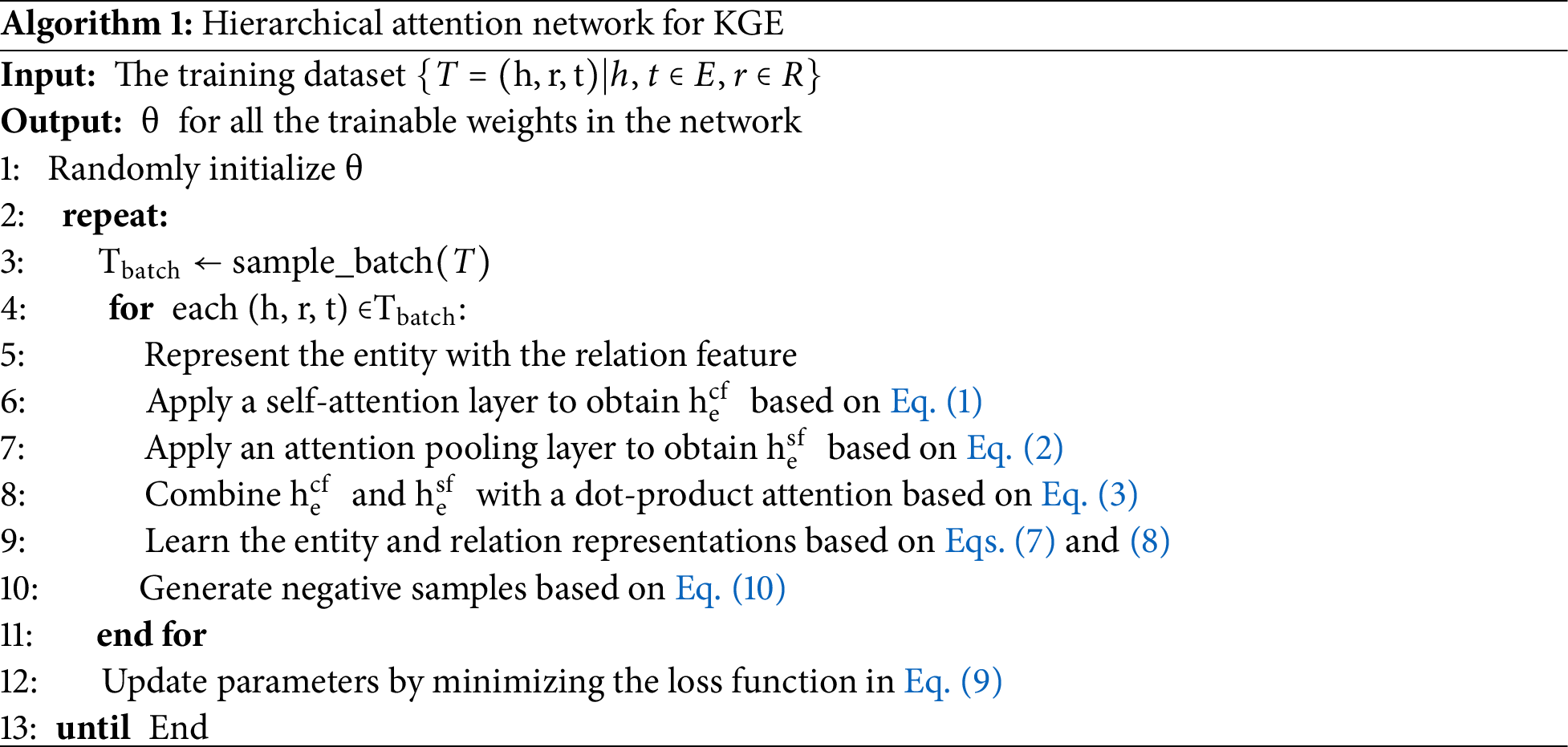

The training procedure for our proposed model is outlined in Algorithm 1. We first initialize the model parameters randomly in line 1. At each iteration, a batch of triples is sampled from the training set in line 3. For each triple in the batch, the relation feature,

In this section, we conduct empirical studies to evaluate the proposed method on the link prediction task. We present the experimental results and analysis to address the following research questions:

RQ1: Is our model parameter-efficient while achieving competitive performance?

RQ2: How do different settings affect the performance of our model?

The following discussion covers these aspects: datasets used in the experiments, evaluation metrics, performance comparison with other methods, and ablation studies to assess the contribution of key components.

The evaluation is performed using the WN18RR dataset which is a knowledge graph benchmark derived from WordNet that is commonly used to evaluate link prediction models [44]. It contains 40,559 entities and 11 relations. In this experiment, the data is split into 86,835 training samples, 2824 validation samples, and 2924 test samples.

The link prediction in KGs focuses on identifying missing relationships by generating and scoring potential triples. For each test triple (h, r, t), we replace either the head or tail entity with candidates from the entity set and rank these new combinations based on their predicted scores. To evaluate model performance, we use three metrics:

Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR): This metric measures the average rank of the true triples among the candidate triples and rewards higher-ranked correct predictions.

Hits@10: This metric calculates the proportion of true triples ranked within the top 10 positions and it reflects the model’s top-10 prediction accuracy.

Efficiency (Effi): To quantify model efficiency, we denote Effi as MRR divided by the number of model parameters (#P), indicating the trade-off between model performance and size.

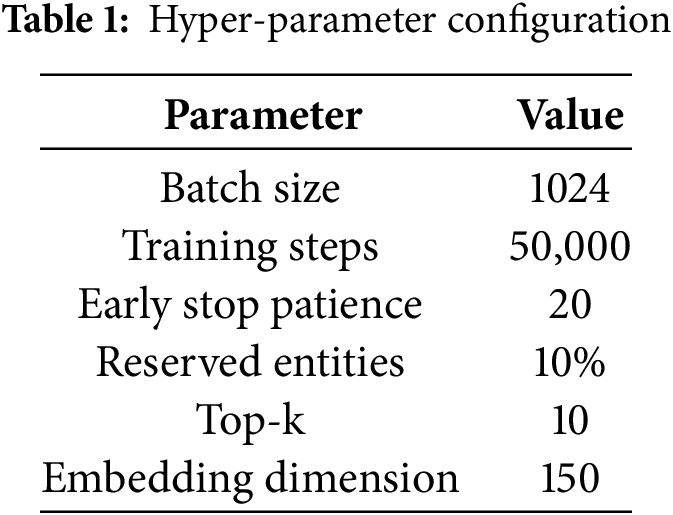

All experiments are conducted on a system with Windows 10, equipped with an Intel Core i9 CPU, 128 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU with 24 GB GDDR6X memory. The hyperparameter configurations are detailed in Table 1. We implement this system primarily using libraries including PyTorch, DGL, and EARL.

To assess the effectiveness of our approach, we conduct a comparison against several leading state-of-the-art models. RotatE, used as a baseline, is a rotation-based KGE method whose parameter count is mainly determined by the embedding dimension [20]. NodePiece+RotatE is the method that combines NodePiece’s efficient node representation learning approach with RotatE’s rotation-based score function to enable more accurate and parameter-efficient representation. EARL+RotatE is the method that uses Entity-Agnostic Representation Learning and RotatE as score function to represent and evaluate entities in KGs [15]. NodePiece+RQ is the method that uses NodePiece tokenization and Random entity Quantization (RQ) to randomly construct a codebook for efficient entity representation in KGs [14].

The experimental results are displayed in Table 2. We present the results of RotatE with larger parameters (40.6 M) and dimensions (500), referred to as RotatE_L, as the upper bound of performance on the WN18RR dataset. In contrast, the results of RotatE with smaller parameters (4.1 M) and dimensions (50), referred to as RotatE_S, serve as the benchmark for comparison using a similar parameter budget. Compared to RotatE_S, EARL+RotateE, NodePiece+RQ and our model all demonstrate better performance in terms of MRR and Hits@10. Among these models, our method achieves the best MRR (0.434) and Hits@10 (0.520) results while utilizing the smallest parameter budget (3.7 M). Specifically, our model utilizes just 90.24% of the parameters while achieving a 5.59% relative improvement in MRR and 21.21% in Hits@10 compared to RotatE. Moreover, our model also obtains the best Effi score shown in the last column of Table 2. The results and analysis presented above address our RQ1.

To evaluate the effectiveness of our attention mechanism, we conduct ablation studies on the WN18RR dataset to examine the benefits of our approach and measure the contribution of each key component. As shown in Table 3, removing any attentional module leads to a drop in performance across all evaluation metrics. These results demonstrate that our approach effectively enhances knowledge graph embedding performance while maintaining efficient parameter storage. Further analysis of the values in the Table 3 reveals that the edge-attention in GNN plays a more crucial role, as its removal results in a more significant performance decrease. In contrast, the dot-product attention has a relatively minor impact on the overall performance.

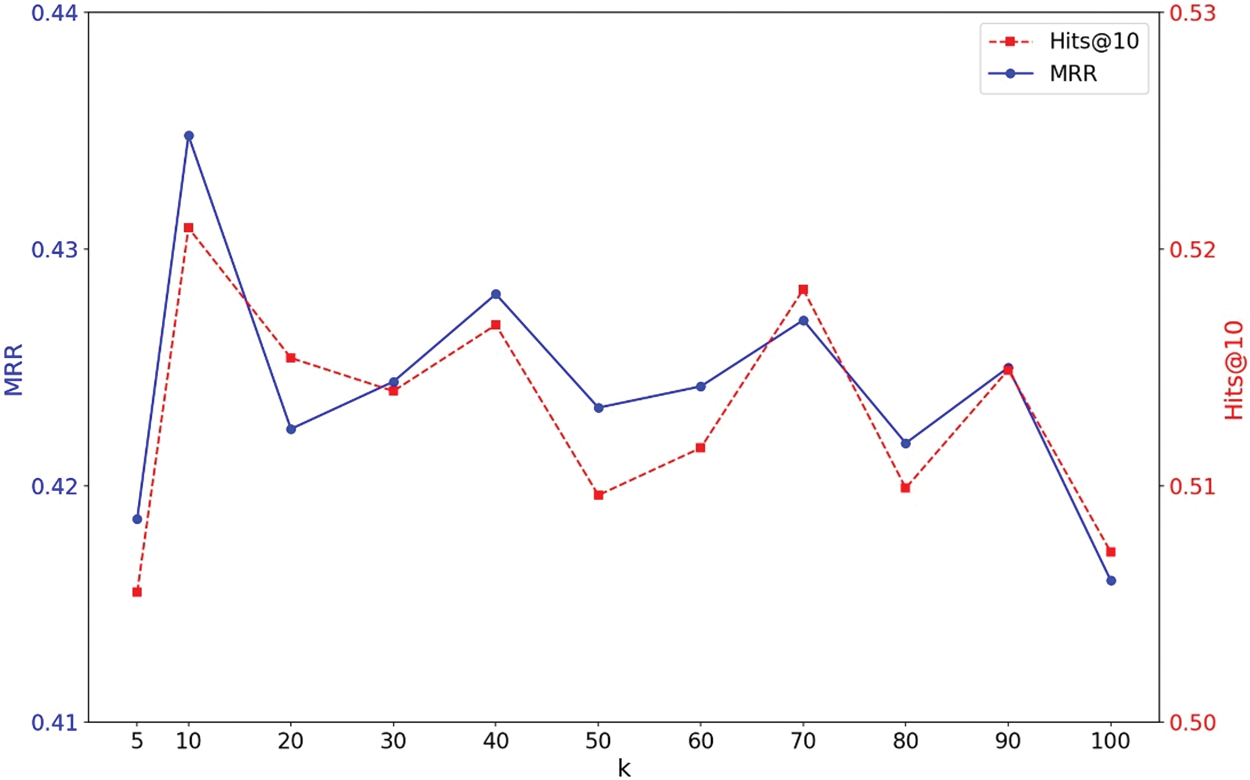

In addition to exploring the impact of different attention modules, we also investigate how varying the k-value in attention pooling module affects model performance. As illustrated in Fig. 2, we plot different k-values against their corresponding MRR and Hits@10 scores. The variance in MRR is approximately 0.0049, while the Hits@10 score variance was around 0.0048. These results indicate that different k-values do not significantly impact model performance. Based on the aforementioned two ablation studies, we can address our RQ2: While different attention modules contribute to model performance, varying k-values does not have a substantial effect.

Figure 2: MRR and Hits@10 performance with different k-values

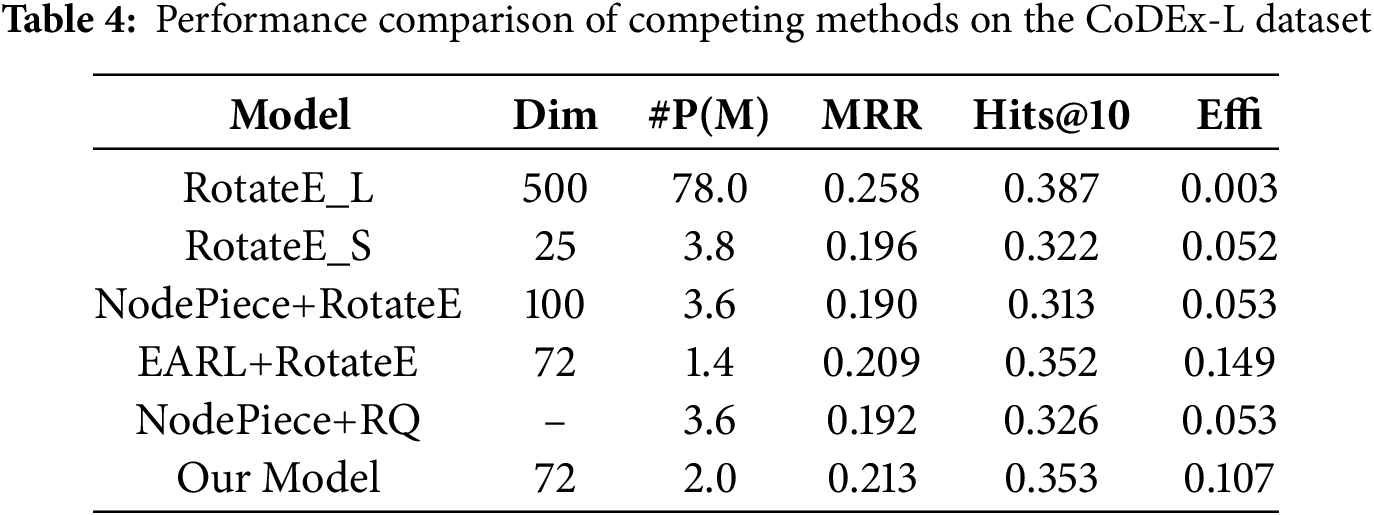

To assess the scalability of our proposed model, we conduct experiments on the CoDEx-L dataset, which contains over 70,000 entities [45]. Following the same experimental settings as previous studies, we utilize a dataset configuration comprising 551,193 training samples, 30,622 validation samples, and 30,622 testing samples. Compared to other models with a similar budget, our model achieves superior performance, as shown in Table 4, with an MRR value of 0.213 and a Hits@10 score of 0.353. These results highlight the robustness and effectiveness of our model in large-scale scenarios. In the comparison with EARL+RotateE, both models use the same dimensionality of 72. However, their model employs slightly fewer parameters, resulting in a better Effi score. Exploring ways to ensure that our model maintains efficient parameter usage on large-scale KGs will be an important direction for future research.

In this paper, we propose a hierarchical attention network architecture to advance parameter-efficient knowledge graph embedding. Our experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach, achieving strong MRR and Hits@10 scores while maintaining parameter efficiency. This balance is particularly crucial as knowledge graphs continue to grow in size and complexity.

Our work opens up several promising research directions. First, future studies could explore the integration of more sophisticated attention mechanisms to further enhance the model’s representational capacity while preserving its efficiency in parameter usage. Second, investigating the model’s scalability to larger knowledge graphs and its potential applications in domain-specific scenarios could provide valuable solutions for real-world implementations and industrial use cases.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank for the financial support from the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan.

Funding Statement: This work was partially supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan, under Grants Numbers 112-2622-E-029-009 and 112-2221-E-029-019.

Author Contributions: Supervision: Xin Wang, Cheng-Hsiung Lee and Ching-Sheng Lin; research design: Zhen-Yu Chen and Ching-Sheng Lin; experiment evaluation: Zhen-Yu Chen; results analysis: Feng-Chi Liu; manuscript preparation: Ching-Sheng Lin; manuscript review: Feng-Chi Liu and Xin Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang K, Liu Y, Ma Q, Sheng QZ. MulDE: multi-teacher knowledge distillation for low-dimensional knowledge graph embeddings. In: Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021; 2021; Ljubljana, Slovenia: ACM. p. 1716–26. doi:10.1145/3442381.3449898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Bollacker K, Evans C, Paritosh P, Sturge T, Taylor J. Freebase: a collaboratively created graph database for structuring human knowledge. In: Proceedings of the 2008 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data; 2008; Vancouver, BC, Canada: ACM. p. 1247–50. doi:10.1145/1376616.1376746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Suchanek FM, Kasneci G, Weikum G. Yago: a core of semantic knowledge. In: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on World Wide Web; 2007; Banff Alberta, AB, Canada: ACM. p. 697–706. doi:10.1145/1242572.1242667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bizer C, Lehmann J, Kobilarov G, Auer S, Becker C, Cyganiak R, et al. DBpedia—a crystallization point for the web of data. J Web Semant. 2009;7(3):154–65. doi:10.1016/j.websem.2009.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hu Z, Xu Y, Yu W, Wang S, Yang Z, Zhu C, et al. Empowering language models with knowledge graph reasoning for question answering. arXiv:2211.08380. 2022. [Google Scholar]

6. Yu D, Zhu C, Yang Y, Zeng M. JAKET: joint pre-training of knowledge graph and language understanding. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2022;36(10):11630–8. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i10.21417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wajid MS, Terashima-Marin H, Najafirad P, Wajid MA. Deep learning and knowledge graph for image/video captioning: a review of datasets, evaluation metrics, and methods. Eng Rep. 2024;6(1):e12785. doi:10.1002/eng2.12785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang X, Meng B, Chen H, Meng Y, Lv K, Zhu W. TIVA-KG: a multimodal knowledge graph with text, image, video and audio. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2023; Ottawa, ON, Canada: ACM; p. 2391–9. doi:10.1145/3581783.3612266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen Y, Kuang J, Cheng D, Zheng J, Gao M, Zhou A. AgriKG: an agricultural knowledge graph and its applications. In: Database Systems for Advanced Applications: DASFAA 2019 International Workshops: BDMS, BDQM, and GDMA; 2019 Apr 22–25; Chiang Mai, Thailand. Vol. 24, p. 533–7. [Google Scholar]

10. Li Y, Zakhozhyi V, Zhu D, Salazar LJ. Domain specific knowledge graphs as a service to the public: powering social-impact funding in the US. In: Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2020; CA, USA: ACM. p. 2793–801. doi:10.1145/3394486.3403330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Tang Z, Pei S, Zhang Z, Zhu Y, Zhuang F, Hoehndorf R, et al. Positive-unlabeled learning with adversarial data augmentation for knowledge graph completion. arXiv:2205.00904. 2022. [Google Scholar]

12. Guo X, Wang P, Gao N, Wang X, Feng W. STDE: a single-senior-teacher knowledge distillation model for high-dimensional knowledge graph embeddings. In: 2022 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Information Communication and Software Engineering (ICICSE); 2022 Mar 18–20; Chongqing, China: IEEE. Vol. 2022, p. 37–45. doi:10.1109/ICICSE55337.2022.9828905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang S, Tay Y, Yao L, Liu Q. Quaternion knowledge graph embeddings. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2019;32. doi:10.5555/3454287.3454533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li J, Wang Q, Liu Y, Zhang L, Mao Z. Random entity quantization for parameter-efficient compositional knowledge graph representation. arXiv:2310.15797. 2023. [Google Scholar]

15. Chen M, Zhang W, Yao Z, Zhu Y, Gao Y, Pan JZ, et al. Entity-agnostic representation learning for parameter-efficient knowledge graph embedding. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(4):4182–90. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i4.25535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hu Z, Gutiérrez-Basulto V, Xiang Z, Li X, Li R, Pan JZ. Type-aware embeddings for multi-hop reasoning over knowledge graphs. arXiv:2205.00782. 2022. [Google Scholar]

17. Wang F, Zheng Z, Zhang Y, Li Y, Yang K, Zhu C. To see further: knowledge graph-aware deep graph convolutional network for recommender systems. Inf Sci. 2023;647:119465. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ji S, Pan S, Cambria E, Marttinen P, Yu PS. A survey on knowledge graphs: representation, acquisition, and applications. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;33(2):494–514. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3070843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Bordes A, Usunier N, Garcia-Duran A, Weston J, Yakhnenko O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 26 (NIPS 2013); 2013. [Google Scholar]

20. Sun Z, Deng ZH, Nie JY, Tang J. RotatE: knowledge graph embedding by relational rotation in complex space. arXiv:1902.10197. 2019. [Google Scholar]

21. Zhang Z, Cai J, Zhang Y, Wang J. Learning hierarchy-aware knowledge graph embeddings for link prediction. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(3):3065–72. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i03.5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li Z, Liu H, Zhang Z, Liu T, Xiong NN. Learning knowledge graph embedding with heterogeneous relation attention networks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;33(8):3961–73. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3055147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Trouillon T, Welbl J, Riedel S, Gaussier É., Bouchard G. Complex embeddings for simple link prediction. In: International Conference on Machine Learning; 2016; PMLR. p. 2071–80. [Google Scholar]

24. Balažević I, Allen C, Hospedales TM. TuckER: tensor factorization for knowledge graph completion. arXiv:1901.09590. 2019. [Google Scholar]

25. Nandi A, Kaur N, Singla P, Mausam. DynaSemble: dynamic ensembling of textual and structure-based models for knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers); 2024; Bangkok, Thailand. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL. p. 205–16. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.acl-short.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ying R, Hu M, Wu J, Xie Y, Liu X, Wang Z, et al. Simple but effective compound geometric operations for temporal knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2024; Bangkok, Thailand. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL. p. 11074–86. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Di Mauro A, Xu Z, Ben Rim W, Sztyler T, Lawrence C. Generating and evaluating plausible explanations for knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2024; Bangkok, Thailand. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL. p. 12106–18. doi:10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Song L, Gong X, Zhou H, Chen J, Zhang Q, Doermann D, et al. Exploring the knowledge transferred by response-based teacher-student distillation. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2023; Ottawa, ON, Canada: ACM. p. 2704–13. doi:10.1145/3581783.3612162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yang C, Yu X, An Z, Xu Y. Categories of response-based, feature-based, and relation-based knowledge distillation. In: Advancements in knowledge distillation: towards new horizons of intelligent systems. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2023. p. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

30. Park SG, Kang DJ. Knowledge distillation with feature self attention. IEEE Access. 2023;11:34554–62. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3265382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Hinton G. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv:1503.02531. 2015. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhou H, Song L, Chen J, Zhou Y, Wang G, Yuan J, et al. Rethinking soft labels for knowledge distillation: a bias-variance tradeoff perspective. arXiv:2102.00650. 2021. [Google Scholar]

33. Huang Z, Wang N. Like what you like: knowledge distill via neuron selectivity transfer. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1707.01219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chen D, Mei JP, Zhang Y, Wang C, Wang Z, Feng Y, et al. Cross-layer distillation with semantic calibration. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(8):7028–36. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i8.16865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chen P, Liu S, Zhao H, Jia J. Distilling knowledge via knowledge review. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA: IEEE. Vol. 2021, p. 5006–15. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.00497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yang C, Zhou H, An Z, Jiang X, Xu Y, Zhang Q. Cross-image relational knowledge distillation for semantic segmentation. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA: IEEE. Vol. 2022, p. 12309–18. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhu Y, Zhang W, Chen M, Chen H, Cheng X, Zhang W, et al. DualDE: dually distilling knowledge graph embedding for faster and cheaper reasoning. In: Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2022; AZ, USA: ACM. p. 1516–24. doi:10.1145/3488560.3498437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sachan M. Knowledge graph embedding compression. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020; Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL. p. 2681–91. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang H, Wang Y, Lian D, Gao J. A lightweight knowledge graph embedding framework for efficient inference and storage. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2021; Queensland, Australia: ACM. p. 1909–18. doi:10.1145/3459637.3482224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Galkin M, Denis E, Wu J, Hamilton WL. NodePiece: compositional and parameter-efficient representations of large knowledge graphs. arXiv:2106.12144. 2021. [Google Scholar]

41. Vaswani A. Attention is all you need. In: 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017); 2017; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

42. Vashishth S, Sanyal S, Nitin V, Talukdar P. Composition-based multi-relational graph convolutional networks. arXiv:1911.03082. 2019. [Google Scholar]

43. Mikolov T, Sutskever I, Chen K, Corrado GS, Dean J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 26 (NIPS 2013); 2013. [Google Scholar]

44. Dettmers T, Minervini P, Stenetorp P, Riedel S. Convolutional 2D knowledge graph embeddings. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2018;32(1). doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Safavi T, Koutra D. CoDEx: a comprehensive knowledge graph completion benchmark. arXiv:2009.07810. 2020. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools