Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Leveraging Unlabeled Corpus for Arabic Dialect Identification

1 School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072, China

2 Department of Computer Science, Applied College, King Khalid University, Muhayil, 63311, Saudi Arabia

3 Computer Science Department, National University of Modern Languages, Faisalabad, 38000, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Mohammed Abdelmajeed. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(2), 3471-3491. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.059870

Received 18 October 2024; Accepted 21 January 2025; Issue published 16 April 2025

Abstract

Arabic Dialect Identification (DID) is a task in Natural Language Processing (NLP) that involves determining the dialect of a given piece of text in Arabic. The state-of-the-art solutions for DID are built on various deep neural networks that commonly learn the representation of sentences in response to a given dialect. Despite the effectiveness of these solutions, the performance heavily relies on the amount of labeled examples, which is labor-intensive to attain and may not be readily available in real-world scenarios. To alleviate the burden of labeling data, this paper introduces a novel solution that leverages unlabeled corpora to boost performance on the DID task. Specifically, we design an architecture that enables learning the shared information between labeled and unlabeled texts through a gradient reversal layer. The key idea is to penalize the model for learning source dataset-specific features and thus enable it to capture common knowledge regardless of the label. Finally, we evaluate the proposed solution on benchmark datasets for DID. Our extensive experiments show that it performs significantly better, especially, with sparse labeled data. By comparing our approach with existing Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs), we achieve a new state-of-the-art performance in the DID field. The code will be available on GitHub upon the paper’s acceptance.Keywords

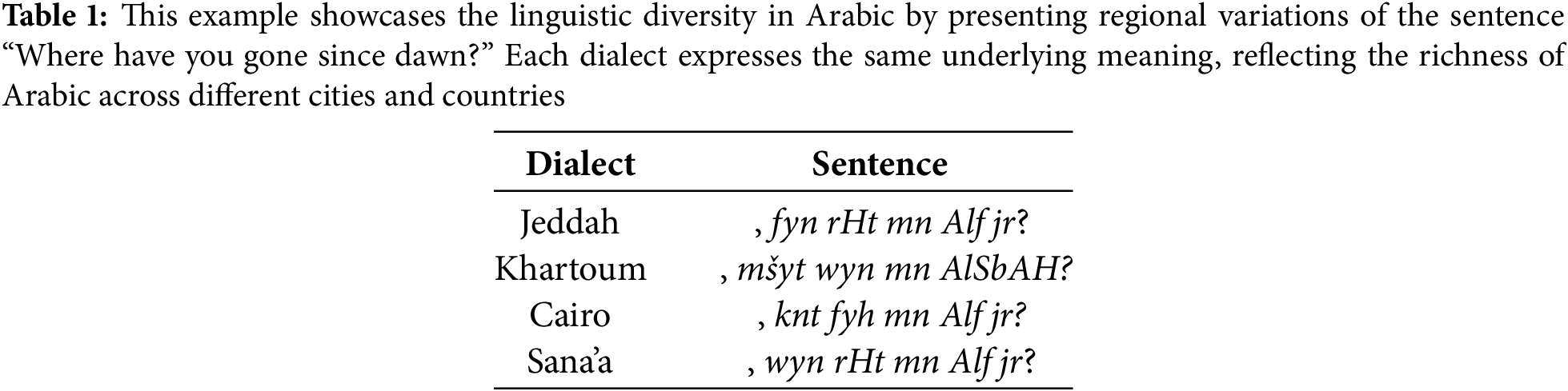

Dialect Identification (DID) constitutes a crucial task in natural language processing (NLP), focusing on discerning the dialectal origin of Arabic texts or speech [1]. For instance, consider the running example shown in Table 1, the phrase (الفجر؟ منذ ذهبت اين, Ayn ðhbt mnð Alfjr?) in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) translates to “Where have you gone since dawn?” in English. This expression exhibits nuanced variations across various Arabic dialects found in cities like Baghdad, Beirut, Jeddah, Khartoum, and Sana’a. The primary objective of DID is to accurately identify these regional dialectal nuances in texts [2]. DID holds significant importance in understanding Arabic as it allows for the nuanced interpretation of texts and speech across diverse regional variations. By distinguishing between dialectal forms, DID enables deeper insights into cultural contexts, social dynamics, and linguistic diversity within Arabic speaking communities [1]. This capability is crucial for applications ranging from language education and communication tools to cultural preservation and media localization, thereby enhancing our understanding and engagement with Arabic language and culture on a global scale [3]. Traditional machine learning techniques for DID, such as Naive Bayes and Support Vector Machines (SVM), aim to extract character and sentence-level features like n-grams and word n-grams as dialectal indicators [4–6]. However, these approaches heavily rely on the quality of the extracted features, and the similarity between dialects often makes dialect-specific features elusive and difficult to obtain. With the rapid development of deep neural networks, DID has witnessed a shift toward using models such as LSTM and CNN [7], based on a pre-trained embedding space, e.g., AraVec [8]. This line of research represents a significant advancement in learning dialect-specific representations. While these approaches are effective in capturing sequential dependencies, they often struggle with long-range dependencies and capturing complex linguistic patterns. Recently, various approaches treat DID as a downstream for fine-tuning pre-trained language models (PLMs) [9–11]. Specifically, the Arabic PLM is initially trained on a large corpus of unlabeled Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) data to learn semantic representations in a self-training setting. Subsequently, it is fine-tuned on labeled Arabic texts, adjusting its weights to enhance performance in DID. Earlier approaches attempted to utilize multilingual PLMs such as mBERT [12], XLM-RoBERTa [13], and LaBSE [14], to represent Arabic dialects. However, despite these efforts, the performance of these multilingual models typically lags behind their monolingual counterparts. This discrepancy primarily arises from smaller, language-specific vocabularies and less comprehensive language-specific datasets [15–18]. While languages with similar structures and vocabularies may benefit from shared representations, this advantage does not extend to Arabic. The unique morphological and syntactic structures of Arabic differ significantly from the frameworks of more widely represented Latin-based languages. To address this challenge, various approaches employ finetuning Arabic-specific PLMs, such as AraBERT [15], ArBERT [19], and CAMeL [20]. These models significantly improve performance on Arabic NLP tasks compared to multilingual models. However, since they are predominantly trained on MSA datasets, their effectiveness on dialectal texts is limited. Additionally, as previously mentioned, the similarities between Arabic dialects make it challenging to learn accurate dialect-specific representations without a substantial amount of labeled data, which is both costly and labor-intensive. A straightforward approach to addressing the aforementioned. Despite the promising results of this approach, it still suffers from two main challenges: (1) continuing training is computationally expensive; (2) the complexity of Arabic makes it challenging to extend the vocabulary of existing PLMs to include more dialectal tokens. For example, in Chinese, new tokens can be initialized by averaging the weights of partially existing characters In Arabic, however, new tokens may never have been seen by the PLM, necessitating the learning of their weights from scratch. To address these limitations, we introduce an adversarial approach to learning robust dialectal-specific representations regardless of the architecture of PLMs. We leverage unlabeled data, which is easy to obtain, to model dialectal patterns by capturing the shared information between labeled and unlabeled data. Specifically, we jointly employ two loss functions. The first function minimizes the likelihood between instances and their ground truth labels, effectively learning to map Arabic texts to their dialects. The second function is a binary classification loss that maximizes the likelihood of identifying the source of an instance, i.e., whether it is labeled or unlabeled. To achieve this, we utilize a gradient reversal layer [21], at the top of the model prediction to deceive the model from recognizing the source of the instance. By penalizing the model for recognizing the source, we prohibit it from relying on source-specific knowledge and instead focus on extracting shared information. Our approach distinguishes itself by effectively differentiating between Arabic dialects and MSA. This capability significantly mitigates the confusion commonly encountered in previous models. Furthermore, our methodology leverages a combination of unlabeled and labeled data, thereby reducing the reliance on large volumes of labeled datasets. This not only lowers the time and cost associated with dataset preparation but also enhances overall model performance. This framework presents a more efficient solution for the research community working on NLP tasks involving Arabic dialects. Accurate identification of dialects is critical for various Arabic language processing applications, such as machine translation (MT), sentiment analysis (SA), and named entity recognition (NER), where accurate classification of the dialect is fundamental to understanding these tasks, ultimately leading to more precise and reliable outcomes. Our approach addresses key challenges such as data scarcity; consequently, it contributes to the development of more robust and reliable NLP systems tailored to the complexities of the Arabic dialect. In brief, the contributions can be summarized as follows:

• We introduce an adversarial learning framework to learn robust dialectal-specific representations applicable across different PLM architectures.

• We jointly employ two loss functions: one maximizes likelihood between instances and their ground truth labels to map Arabic texts to their dialects; the other minimizes the likelihood of the model recognizing instance labeling using a gradient reversal layer to focus on shared information.

• Our empirical evaluation demonstrated a state-of-the-art performance on benchmark datasets for DID, enhancing PLMs trained on large dialectal corpora.

The remainder of the paper is divided into the following sections. The related work is reviewed in Section 2. In Section 3, we describe the proposed solution. Section 4 presents the experimental setup and provides an empirical assessment of the performance of the proposed solution. Finally, we conclude this paper with Section 5.

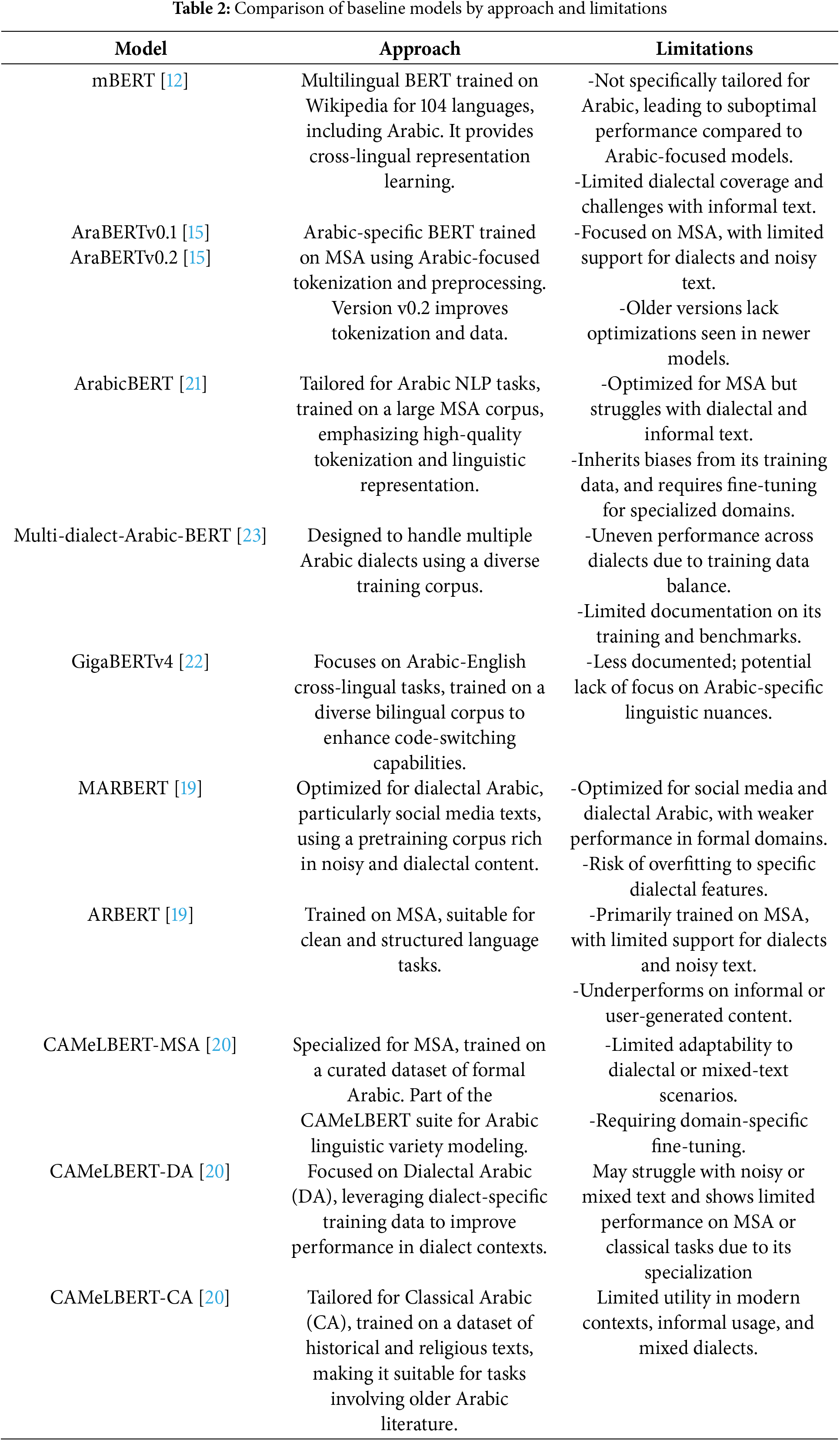

Arabic Dialect Identification (DID) is a crucial task in Arabic Natural Language Processing (NLP). The advent of Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) has facilitated significant advancements in addressing DID. Some of the earliest and most influential efforts in this area include AraBERT [15], ArabicBERT [21], GigaBERT [22], and MDABERT [23], these models, particularly ArabicBERT and its variant MDABERT, have laid the groundwork for Arabic PLMs. Their development has provided a solid foundation that has been beneficial for many subsequent Arabic NLP tasks, including DID. The continued enhancement and adaptation of these models underscore their importance and impact on the field of Arabic NLP. Following these initial efforts, ARBERT and MARBERT [19], reported new state-of-the-art results on the majority of the datasets in their fine-tuning benchmarks, further advancing the capabilities of PLMs in Arabic NLP. Also, reference [20] conducted a series of carefully controlled experiments on a variety of Arabic NLP tasks in order to determine how the size, variation of the language, and type of fine-tuning task affected Arabic language models that had already been trained. They pre-trained these models on a large collection of MSA and DID datasets, as shown in Table 2. In addition to many studies than fine-tuned Arabic PLMs in DID task [9,11,24,25]. Nevertheless, the main challenge with Arabic dialect using PLMs is obtaining sufficient training data, which remains a significant hurdle. Thus, Arabic-specific (PLMs) are primarily trained on MSA, which compromises their performance on Arabic dialects. This limitation motivated us to develop a technique to bridge the gap between MSA, the language of the pre-trained model, and the Arabic dialects used in task-specific datasets. Our proposed method aims to leverage unlabeled dialect corpora to enhance the representation of Arabic dialects. Reflecting on previous studies, adversarial settings have been integrated with BERT-based models to generate diverse examples, aiding various text classification tasks. For instance, reference [26] introduced a model for adversarial generating examples by applying perturbations based on the BERT Masked Language Model. Additionally, reference [27] extended the fine-tuning of BERT-based models by incorporating unlabeled examples through a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [28]. This approach proved beneficial in training models with limited labeled examples and significantly enhanced the classification capabilities of BERT-based models. Therefore, PLMs have been shown to be effective for cross-domain and cross-lingual NLP tasks [29–31]. Consequently, domain-adaptive fine-tuning of PLMs, a prevalent Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (UDA) method for NLP tasks, has proven to be more effective. This approach involves fine-tuning a pre-trained PLM on a substantial amount of unlabeled text data from the target domain using the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) objective. The MLM objective is a pre-training task where the model learns to predict masked tokens in a sentence [23,24]. Self-training has emerged as a popular approach for UDA with PLMs. The core concept involves leveraging a PLMs to generate predictions on the unlabeled data within the target domain. These predictions, referred to as “pseudo-labels,” are subsequently used to augment the labeled data from the source domain. By incorporating pseudo-labeled data, the model’s performance on the target domain can be significantly improved, as demonstrated in studies by [32] and [33]. In the same context, reference [34] extended BERT based models, ARBERT and MARBERT [19], with a generative adversarial setting. Additionally, reference [35] proposed an unsupervised domain adaptation approach for Arabic cross-domain and cross-dialect sentiment analysis using contextualized word embeddings. Reference [36] introduced an unsupervised domain adaptation framework for Arabic multi-dialectal sequence labeling that leverages unlabeled dialectal Arabic data and labeled MSA data. More recently, Arabic dialect identification has garnered significant attention in the field of natural language processing (NLP), with various approaches emerging to address this challenge. These include shared task initiatives [37,38] pre-trained models based on Arabic dialect [39], and efforts focusing on specific regional dialects [40], or across broader Arabic-speaking areas [41]. This growing focus highlights the importance of accurately identifying dialect variations in Arabic, recognizing it as a crucial step towards enhancing NLP applications in Arabic-speaking regions. In this paper, we investigate the potential advantages of utilizing unlabeled data to enhance the performance of Arabic PLMs. By harnessing this unlabeled data, we posit that it can streamline data processing efforts and effectively improve the overall model performance, thereby optimizing resource allocation. Through extensive experimentation, we demonstrate the promising outcomes of our approach on 12 diverse pre-trained models. These findings underscore the viability of our method as a compelling option to enhance DID performance by leveraging unlabeled data, with potentially far-reaching implications across various applications.

Arabic dialects are widely spoken in informal daily communication among Arabic speakers, and are true native languages. They vary widely across different regions and countries [1]. However, it is important to note that while MSA is the formal language used in education, politics, media, and other formal contexts, Arabic dialects are not typically taught or standardized in the same way [42]. In addition to being used in informal conversations, Arabic dialects are also often used in various forms of media, including drama, movies, and theater [43]. This is because these dialects can add authenticity and depth to portrayals of Arabic speaking cultures and communities. However, it is important to note that the use of dialects in media can sometimes lead to misunderstandings or misrepresentations of the language and culture, especially when it comes to non-native speakers or those unfamiliar with the nuances of the dialects. While Arabic dialects may not have a standardized grammar in the same way Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) does, Arabic dialects lack official orthographies, making it challenging to establish definitive spellings for dialectal words. Unlike standardized languages, there are no “incorrect” spellings for dialectal words, and multiple written forms of the same word can exist [44]. For example, the word أين, Âyn which means “where” in English can be written as وين, wyn, and فين, fyn, in certain Arabic dialects. This variation poses a significant challenge, particularly when dealing with text. MSA is still the established standardized form of Arabic that is used in education, media, art, literature, formal speeches, business, and legal writing. MSA is founded on a collection of scientific principles that have been put into practice for a significant amount of time, and it possesses a well-established grammar and orthography [43]. The standardized orthography of MSA has been employed in the writing of all Islamic texts and the earliest literature originating from the Arabian Peninsula. This means that MSA has a rich literary history and is still widely used in Arabic literature and poetry today. In addition, MSA is the language of instruction in many schools and universities throughout the Arabic speaking world. Arabic dialects are often categorized based on their geographical location and regional variations. As mentioned earlier, some of the major categories include: Nile Valley Arabic dialects, includes, Egypt and Sudan. Maghrebi Arabic dialects, contains, Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania, Libya, and Tunisia. Gulf Arabic dialects, consist of, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain, and other parts of the Persian Gulf region. Levantine Arabic dialects, involves, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria (and sometimes also including Iraq). Yemeni Arabic dialects, covers, Yemen and sometimes referred to as Gulf of Aden Arabic. Each of these categories includes multiple dialects with their own unique characteristics and variations.

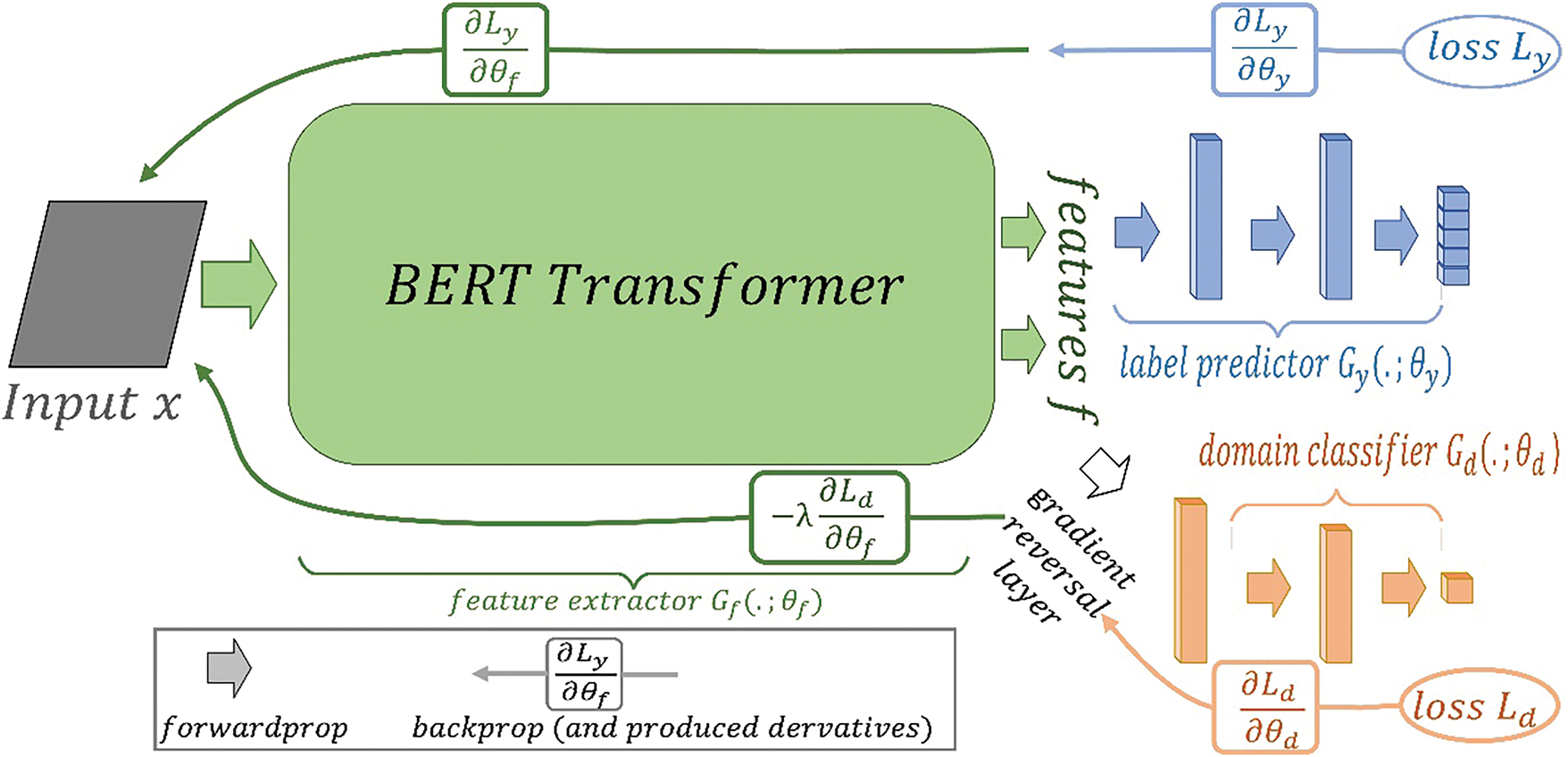

Initially, we provide the technical specifics of the proposed approach in Fig. 1. Then describe the Arabic Dialect Identification task. Followed by fine-tuning BERT to learn the Arabic dialect representation sentence. Finally, we describe the unsupervised domain adaptation technique in detail.

Figure 1: An example of presented solution, which includes a feature extractor (green) that is a pre-trained BERT encoder, a deep label predictor (blue), and a domain classifier (orange) connected to the feature extractor by a gradient reversal layer that doubles the gradient by a negative constant. On the other hand, training reduces label prediction loss and domain classification loss (for all samples). Gradient reversal compares the distributions of features across domains, (making them indistinguishable to the domain classifier). This makes domain-invariant features

Consider a dataset denoted as

Recently, BERT [12] was used extensively in numerous NLP tasks [45,46]. BERT is a pre-trained model that has learned to understand semantic context from a large corpus of text. However, in order to apply it to specific tasks or domains, it needs to be fine-tuned by training it on a smaller labeled dataset that is specific to the task or domain. This fine-tuning phase allows the model to adjust its parameters to better understand and classify the input data [47]. In BERT notation, the input is typically referred to as the input sequence. However, our objective is to learn the BERT representation of a given Arabic dialect. Let

where

4.3 Unsupervised Domain Adaptation

Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (UDA) is principally concerned with the transference of knowledge from a resource-rich domain to a domain with limited resources [48]. The fundamental strategy involves prompting the model to assimilate and integrate shared information across both domains [49]. In our work, we have harnessed the UDA framework to effectively utilize the abundance of unlabeled corpora (target domain). This approach is pivotal in enabling the model to learn dialect representations accurately, even in the context of a paucity of labeled data (source domain). Our methodology is underpinned by two distinct but complementary objectives: the dialect classifier and the dataset classifier. The former is tasked with delineating a mapping function that correlates dialect features with their corresponding latent space representations. The latter, conversely, is engineered to integrate features from the unlabeled corpus, whilst concurrently conditioning the model to remain indifferent to the provenance of the instances, whether labeled or unlabeled. This dual-objective strategy serves as a sophisticated ’fooling mechanism’. It penalizes the model for any tendency to overfit to the characteristics of the unlabeled instances, thereby redirecting its focus towards the extraction and application of universal features prevalent across both labeled and unlabeled datasets. The following is the training scenario:

We assume that we have a dataset

Here,

The saddle point plays a vital role in achieving equilibrium between the dataset classifier (for both labeled and unlabeled instances) and the label classifier. This balance is essential for the model to effectively capture the shared characteristics between labeled and unlabeled instances. Such an ability significantly enhances the learning of dialect representations, leading to more accurate predictions. At the saddle point, the parameters of the domain classifiers (denoted as

where

where Ӏ is a matrix of identities. Then, we can define the “pseudo-function” of

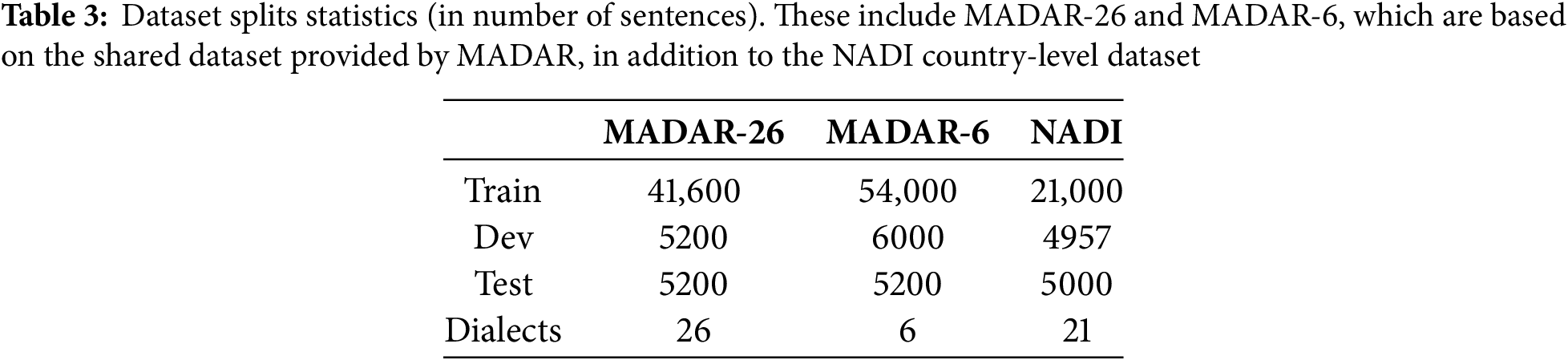

In order to demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed method, we conducted experiments on benchmark datasets that are commonly used in the DID task as follows:

MADAR dataset [50]. The MADAR (Multi-Arabic Dialect Applications and Resources) dataset is designed to capture a broad spectrum of linguistic variations across Arabic dialects and MSA. The dataset provides parallel sentence collections, with MADAR-26 covering MSA and 25 Arabic dialects, enabling model training on a diverse set of dialectal nuances. Additionally, MADAR-6 focuses on five specific dialects and MSA, allowing for in-depth testing on a targeted subset.

NADI dataset [51]. Nuanced Arabic Dialect Identification (NADI) dataset addresses dialectal identification at both country and province levels. It includes tweets from 21 Arabic-speaking countries for the country-level.

Unlabeled data1. We collected a large corpus of unlabeled Arabic dialect data from diverse sources, focusing primarily on social media platforms. We manually extracted MSA sentences from this corpus to maintain data quality, resulting in a varied and extensive unlabeled dataset for further enhancing model performance through unsupervised learning techniques. The detailed statistics of the datasets are summarized in Table 3.

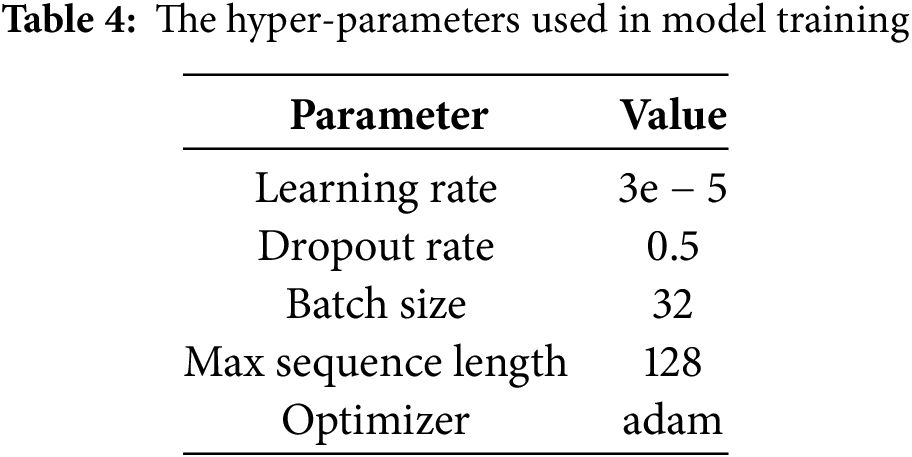

Our models are built with hugging face’s open-source transformers library. They were trained following the experimental Setup of CAMeLBERT [20], which is characterized by 10 training epochs, a batch size of 32 sentences, a learning rate of 3e − 5, and a max sequence length of 128. We used the optimal checkpoints based on the validation sets to provide results on the test sets that use the macro F1 score after fine-tuning. Furthermore, our model advocates for the addition of one more hyper-parameter

We find out that the value of 1e − 2 for

Adaptive Lambda Schedule. To effectively suppress the noisy signal from the domain classifier during the initial stages of the training process, rather than keeping the adaptation factor

Model Initialization. Domain Classifier: Configured with binary cross-entropy loss to distinguish between source and target domains, with a learning rate of 0.0001 and early stopping to reduce overfitting. Label Predictor: Trained on source data to map features to dialect labels, using cross-entropy loss, with a learning rate of 0.0005 and a batch size of 32.

Preprocessing and Feature Extraction. Both source and target data undergo NLP preprocessing (e.g., stop-word removal). The BERT-based feature extractor generates an

Domain-Adversarial Training. Goal: Learn domain-invariant features by training the feature extractor to maximize the domain classifier’s error using a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL). The GRL reverses gradients by multiplying them by −λ, discouraging domain-specific biases. Optimization: Parameters

Saddle Point Optimization. This balance between label prediction and domain classification objectives enhances domain invariance while retaining dialect accuracy.

Gradual Domain Adaptation. Fine-Tuning: Uses a progressively reduced learning rate (0.00001) to limit overfitting on source data-specific features. Loss Function: The total loss combines cross-entropy (label predictor) and domain classification loss, weighted by λ.

Gradient Update Steps. The GRL modifies gradient flow, ensuring domain-invariant features by reversing gradients from the domain classifier.

When evaluating our model, we compared it to a number of different baselines, including the following:

CAMeLBERT [20]. CAMeLBERT examined Arabic PLM effects. It examined how model size, language variation, and fine-tuning task type affected pre-trained models on Arabic-language datasets.

AraBERT [15]. AraBERT is a state-of-the-art PLM that has been specifically designed for the Arabic language. It has been trained on a large corpus of Arabic text, including news articles, web pages, and other online sources, using the Transformer architecture.

MDABERT [23]. MDABERT is a Multi-dialect Arabic model that was further pre-trained from ArabicBERT [21] on the ten million tweets that the NADI competition organizers made available to the public.

mBERT [12]. Multilingual BERT is a PLM that was developed by Google to support multiple languages. The mBERT model is trained using a two-step process that involves pre-training on large quantities of unlabeled data, followed by fine-tuning on smaller labeled datasets for specific downstream NLP tasks.

ArabicBERT [21]. ArabicBERT is a PLM for Arabic text data that is based on the BERT architecture. In the context of identifying offensive speech text in social media, ArabicBERT has been found to be particularly effective when combined with a CNN.

GigaBERTv4 [22]. Five pre-trained versions of GigaBERT were introduced, which were trained using the Transformer encoder [52], and BERT-base configurations. Each of the 12 attention layers in GigaBERT has 12 attention heads and 768 hidden dimensions, which results in a total of 110 million parameters.

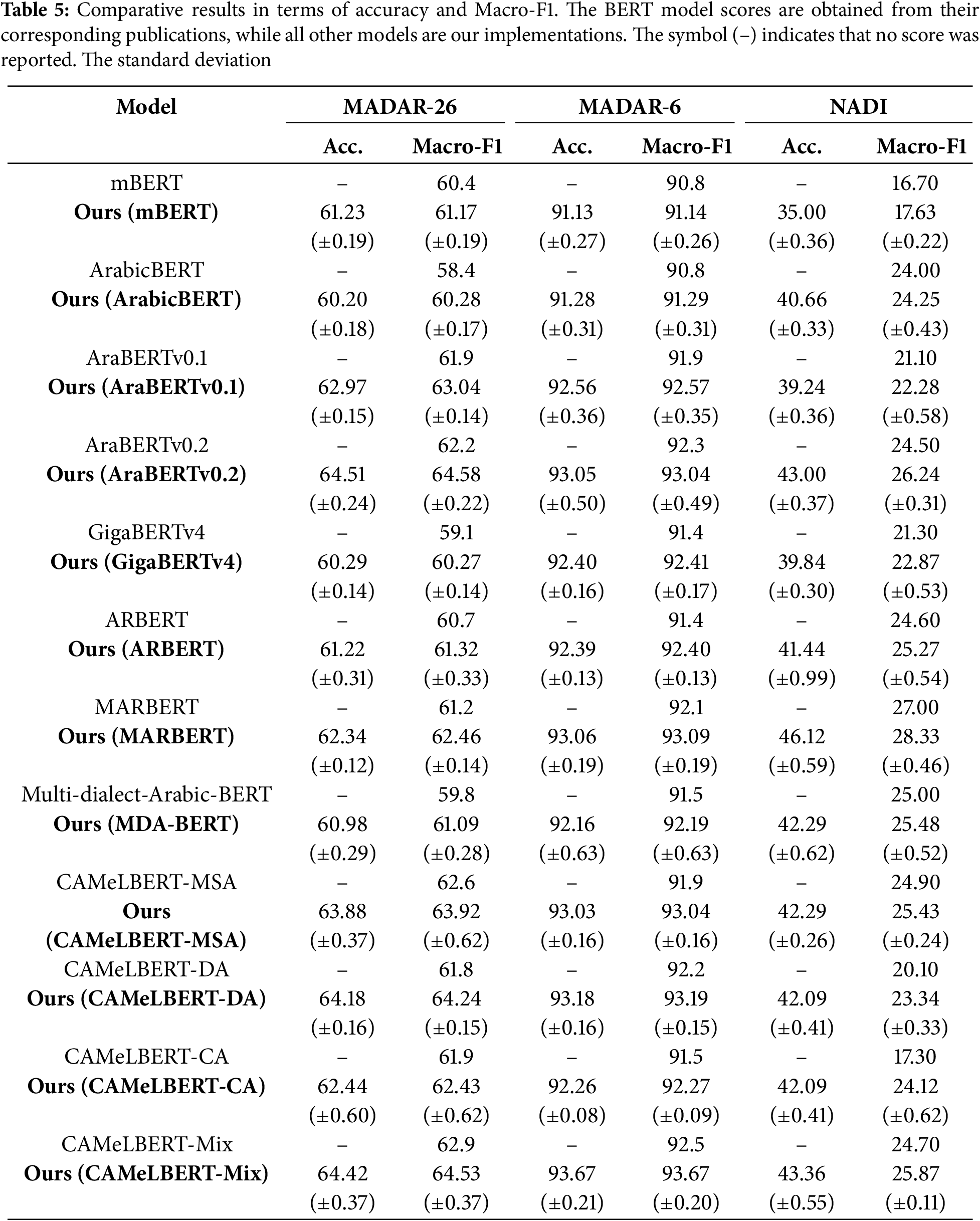

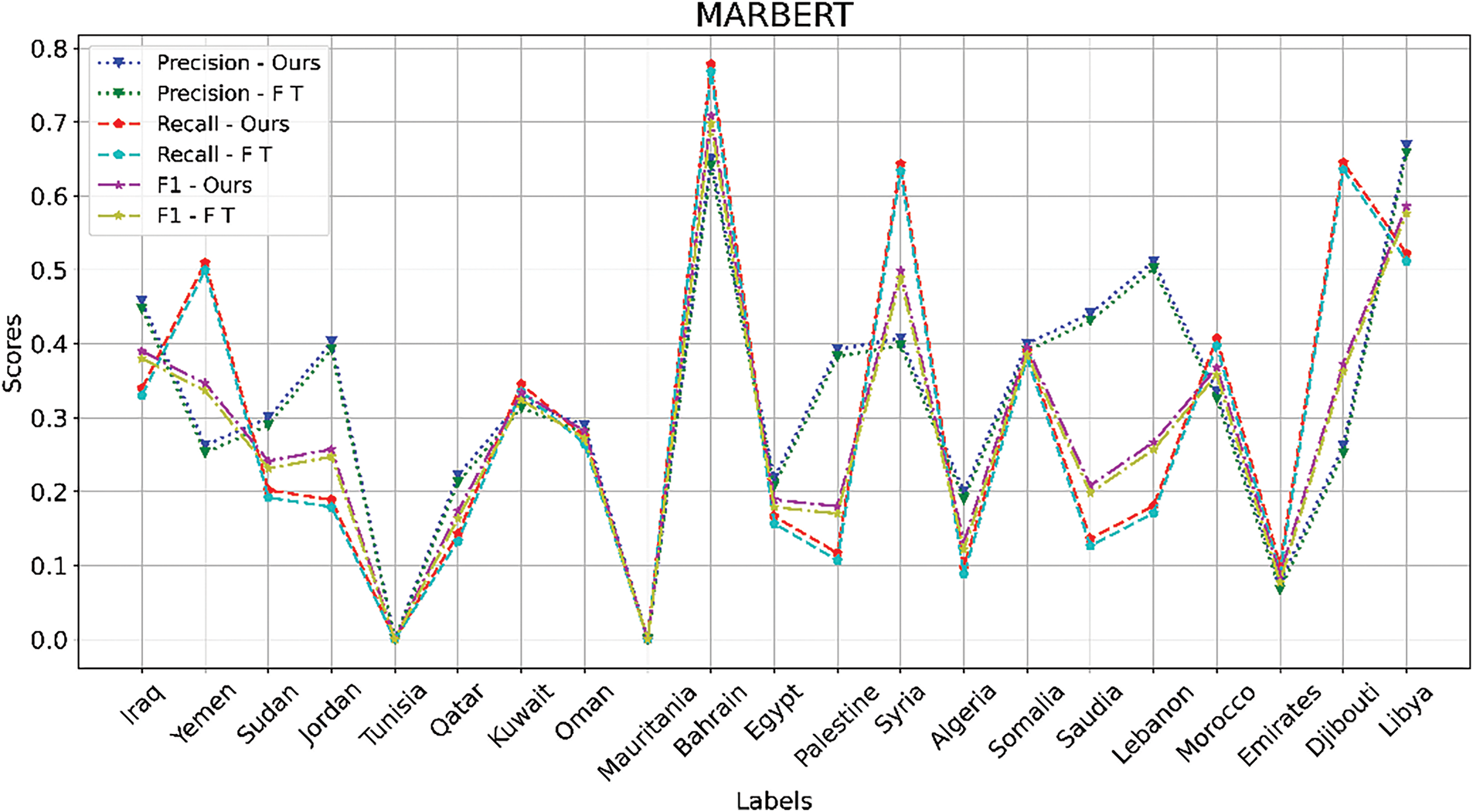

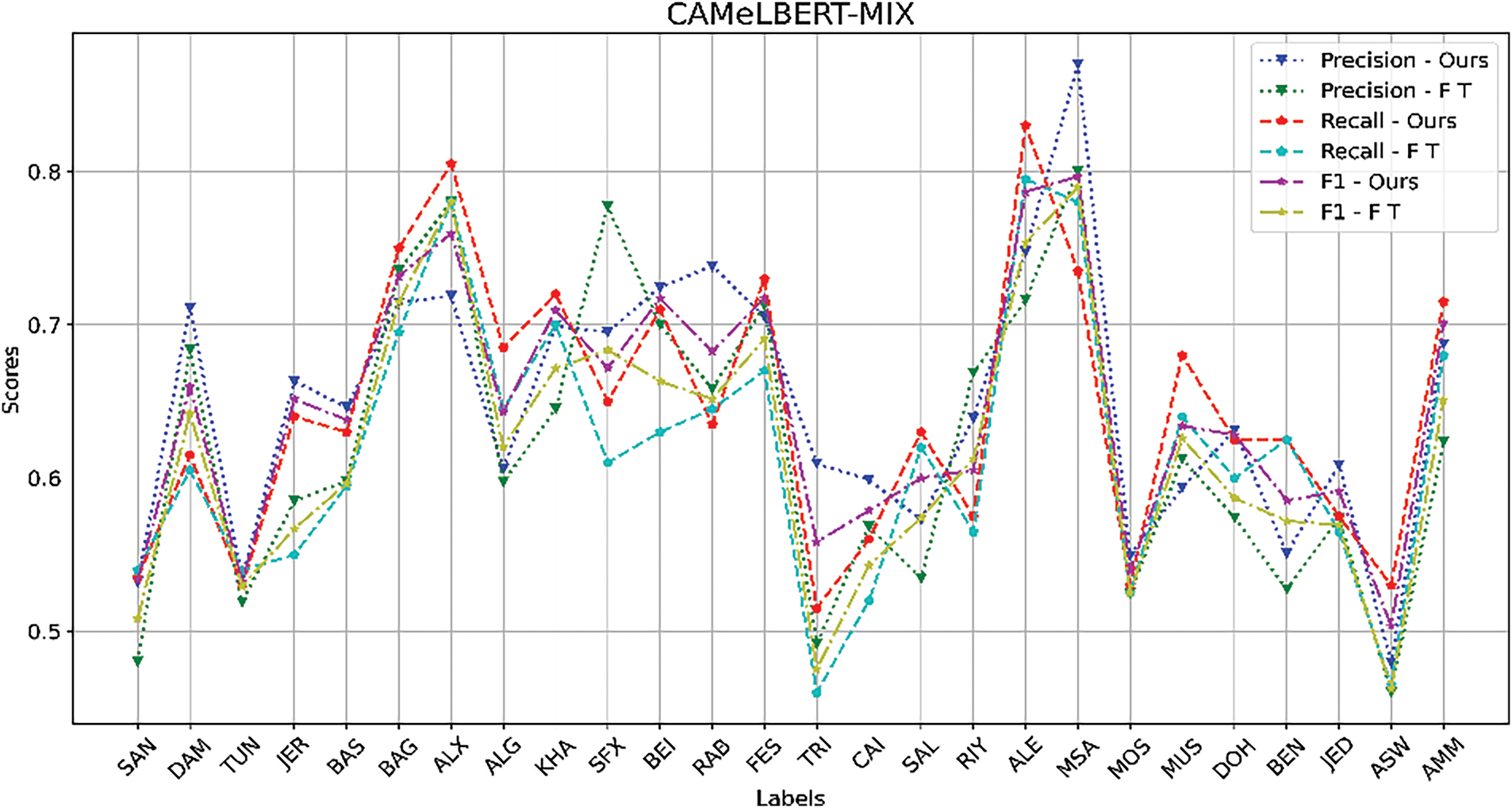

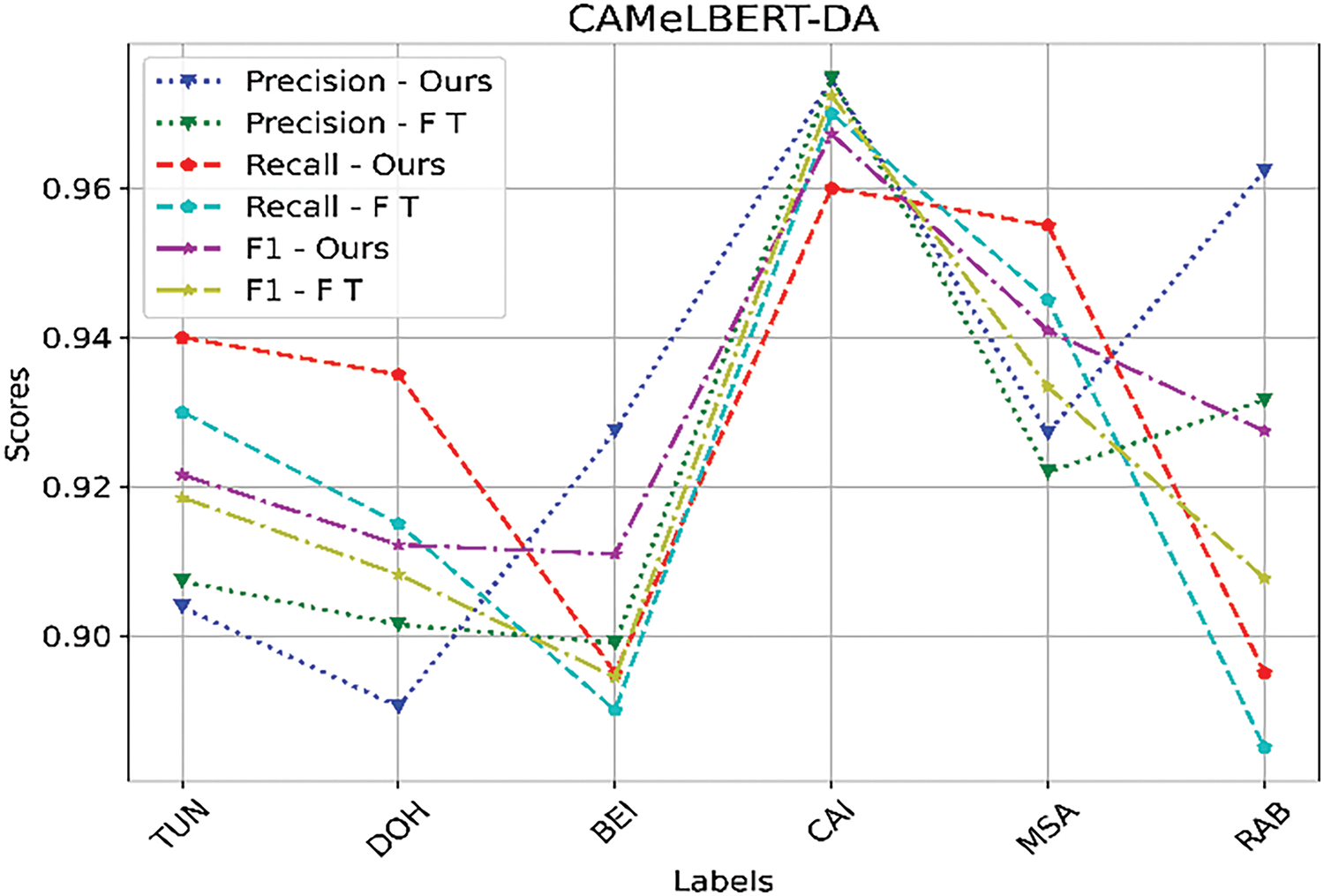

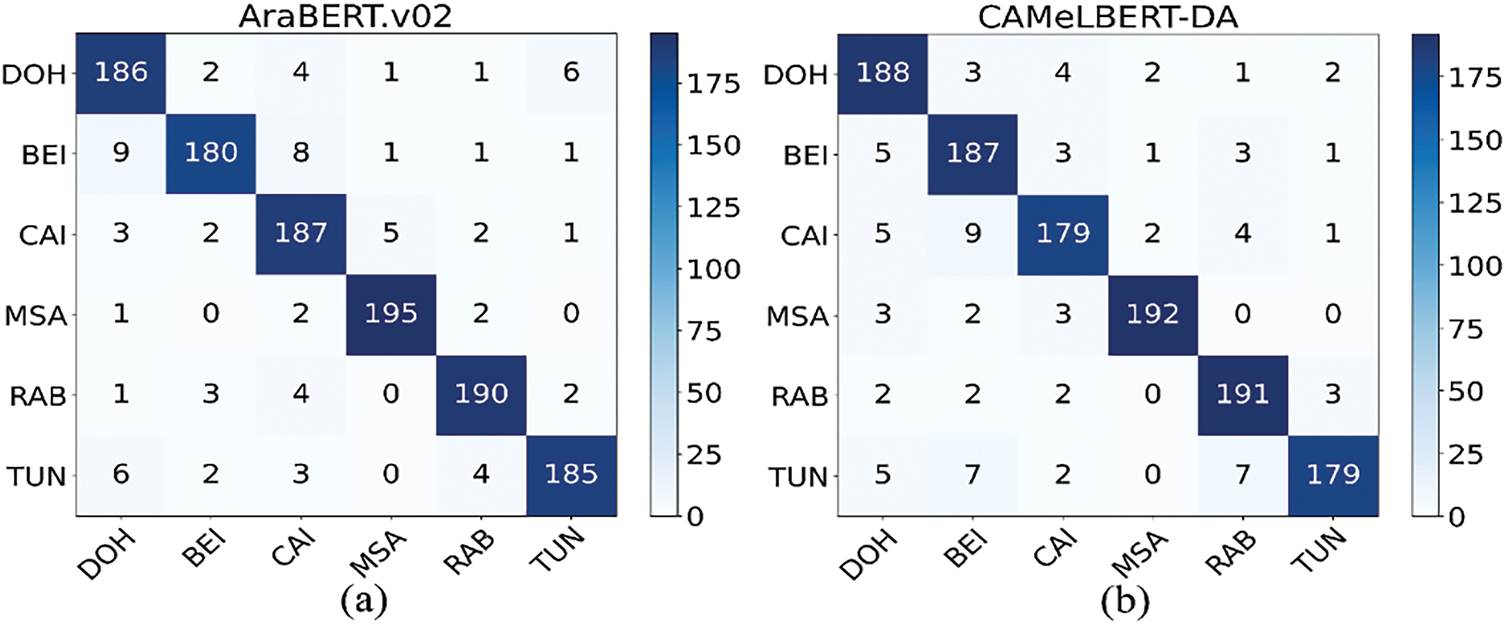

We employ the validation set to choose the best model, and then we average the performances of five different runs using a variety of random seeds. We give the comprehensive evaluation results in Table 5. From the results we arrive to the following observations: (1) Since our proposed solution relies on pre-trained models to improve accuracy, the first observation is that these models behave differently depending on the pre-training setting, task, and data used in pre-training, as well as downstream task datasets. (2) In contrast to MADAR-6 and MADAR-26, the reason for NADI’s country-level poor performance is that some classes scored zero in Precision, Recall, and F1 scores, as illustrated in Fig. 2. (3) Our proposed solution outperforms the state-of-the-art models regardless of the amount of the dataset and the abundance or lack of class labels. As can be seen, compared to the previous state-of-the-art models based on Bert, our proposed method performs significantly better, as shown below. We ran our comparative experiments using Bert-based state-of-the-art models, which include: mBERT, ArabicBERT, AraBERTv0.1, AraBERTv0.2, GigaBERTv4, ARBERT, MARBERT, Multi-dialect-Arabic-BERT, CAMeLBERT-MSA, CAMeLBERT-DA, CAMeL-BERT-CA, and CAMeLBERT-MIX. Each experiment is performed twice for each model, once without our proposed solution and once including it, and then, we compare the results. Using the MADAR-26 dataset, in terms of accuracy and macro-F1 scores, our solution consistently outperforms the state-of-the-art, by the following margins: 0.77%, 1.88%, 1.14%, 2.38%, 1.17%, 0.62%, 1.26%, 1.29%, 1.32%, 2.44%, 0.53%, and 1.63%. Conducting the experiments on the MADAR-6 dataset using the aforementioned models, on the same principle, showed the following boost in performance: 0.34%, 0.49%, 0.67%, 0.74%, 1.01%, 1.00%, 0.99%, 0.69%, 1.14%, 0.99%, 0.77%, and 1.17%. In addition to MADAR-26 and MADAR-6, we also used the NADI county-level dataset, on which we noted the following improvements: 0.93%, 0.25%, 1.18%, 1.74%, 1.57%, 0.67%, 1.33%, 0.48%, 0.53%, 3.24%, 6.82%, and 1.17%, for the aforementioned models. When looking at the results of the MADAR-26 and MADAR-6 datasets, we find that the difference is large in the overall results for the same data, and this is attributed to the increase in classes in the case of MADAR-26 compared to MADAR-6. This claim is backed up by the detailed results in Figs. 2–4 which include precision, recall, and F1 scores. The difference between MADAR-6, MADAR-26, and NADI is clear in the results of the same class labels for both datasets. As for the NADI country-level dataset, it suffers from a lack of training data, which merely covers the available class-labels. This causes the classifier to be more confused given the great similarity in the Arabic dialects between neighboring Arab countries.

Figure 2: Comparison of Precision, Recall, and F1 metrics between the MARBERT fine-tuned model and our model based on MARBERT using the NADI Country-level dataset

Figure 3: Comparison of Precision, Recall, and F1 metrics between the CAMeLBERT-Mix fine-tuned model and our model based on CAMeLBERT-Mix, using MADAR-26

Figure 4: Precision, Recall, and F1 metrics compared between CAMeLBERT-DA fine-tuned model and our model based on CAMeLBERT-DA using MADAR-6

Consequently, the results appear significantly lower than on other datasets. We generated confusion matrices in Fig. 5 to verify the reliability of our results, the viability of our proposed model, and to illustrate the complexity of the DID task. The findings further indicate that adversarial learning with BERT transformers leads to significantly improved performance compared to fine-tuning PLMs. In conclusion, overall results show that the unsupervised domain adaptation framework we have proposed for identifying Arabic dialects performs better than the state-of-the-art baselines in all experiments utilizing different PLMs.

Figure 5: The confusion matrix of our model based on (a) AraBERTv0.2 and (b) CAMeLBERT-DA models for the MADAR-6 dataset

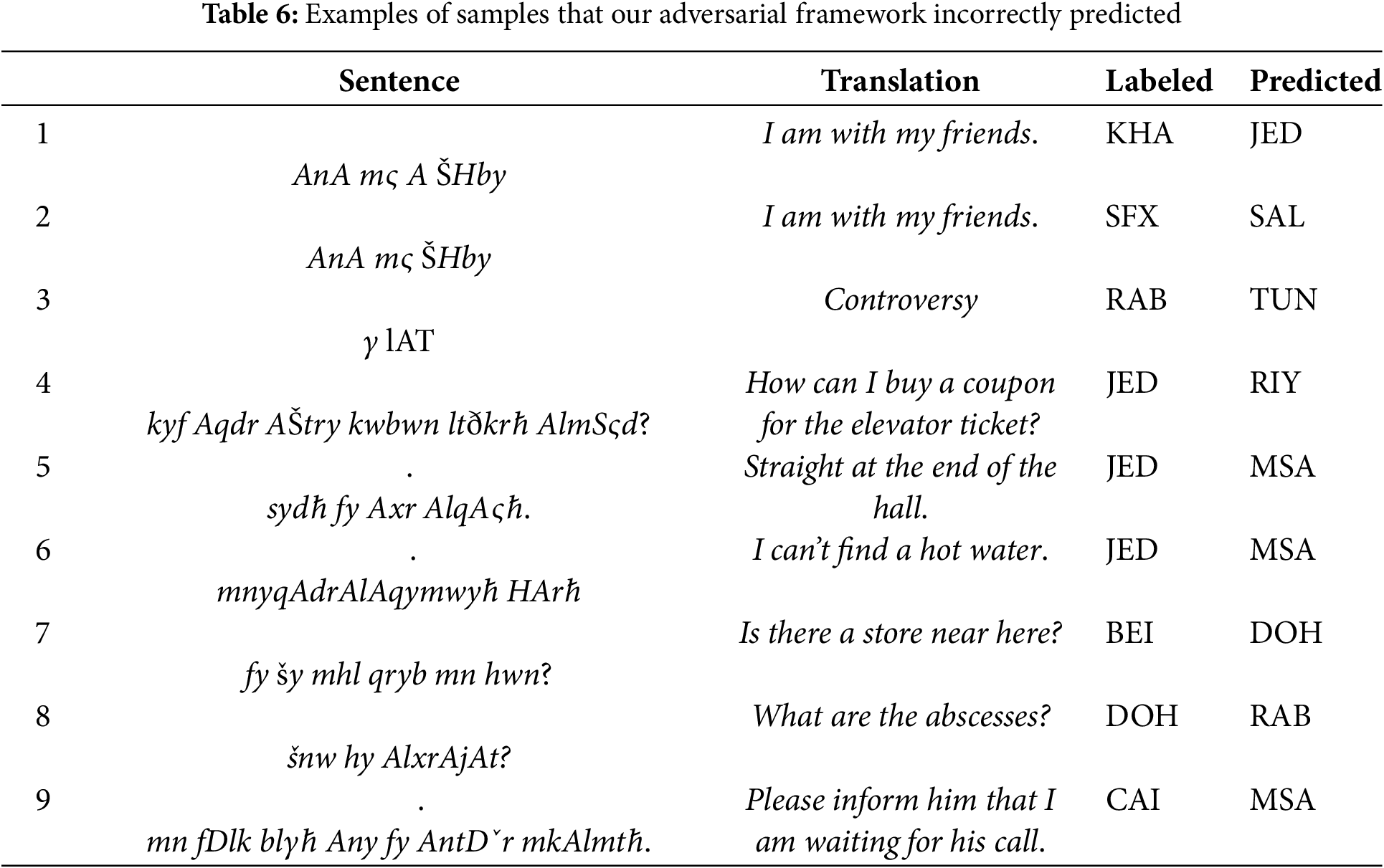

Despite the improvements made with the proposed solution, conducting a thorough performance analysis is crucial to uncovering its limitations. To achieve this, we performed an in-depth evaluation of the MADAR-26 and MADAR-6 datasets, using our model with weights from CAMeLBERT-MIX and CAMeLBERT-DA, respectively. The task is complex due to the considerable similarity between Arabic dialects, which challenges the model’s ability to distinguish effectively as shown in the Table 6. We categorize the errors into two distinct types:

• The shared Arabic dialects: Sentences 1. اصحابي مع انا and 2 صحابي مع انا appear similar, differing by only a single letter; however, they are labeled differently. Sentence [1] labeled as KHA, but the KHA classifier fails to accurately identify it due to the prevalent use of the term “اصحابي” across both KHA and JED dialects. Consequently, this results in a misclassification of the sentence as belonging to the JED dialect. Sentence 2 labeled as SFX, but the SFX classifier fails to accurately identify it due to the prevalent use of the term “صحابي” across both SFX and SAL dialects. The matter becomes challenging as the number of words in a sentence decreases. This overlap often confuses the classifier, leading to incorrect classifications. For instance, sentence 3 غلاط, which contains only one word, is shared between the RAB and TUN dialects. Although it is labeled as RAB, the classifier predicts it as belonging to the TUN dialect.

However, when the labels represent cities within the same country, the situation becomes even more complex. This is illustrated by sentence 4 المصعد؟ لتذكرة كوبون اشتري اقدر كيف, which was labeled as JED but predicted as RIY. Jeddah and Riyadh are cities in Saudi Arabia. The sentences 7 هون؟ من قريب محل شي في, and الخراجات؟ هي شنو, were labeled as BEI and DOH, respectively. Despite their rich dialectal content, the shared expressions among similar dialects led to their misclassification as DOH and RAB, respectively.

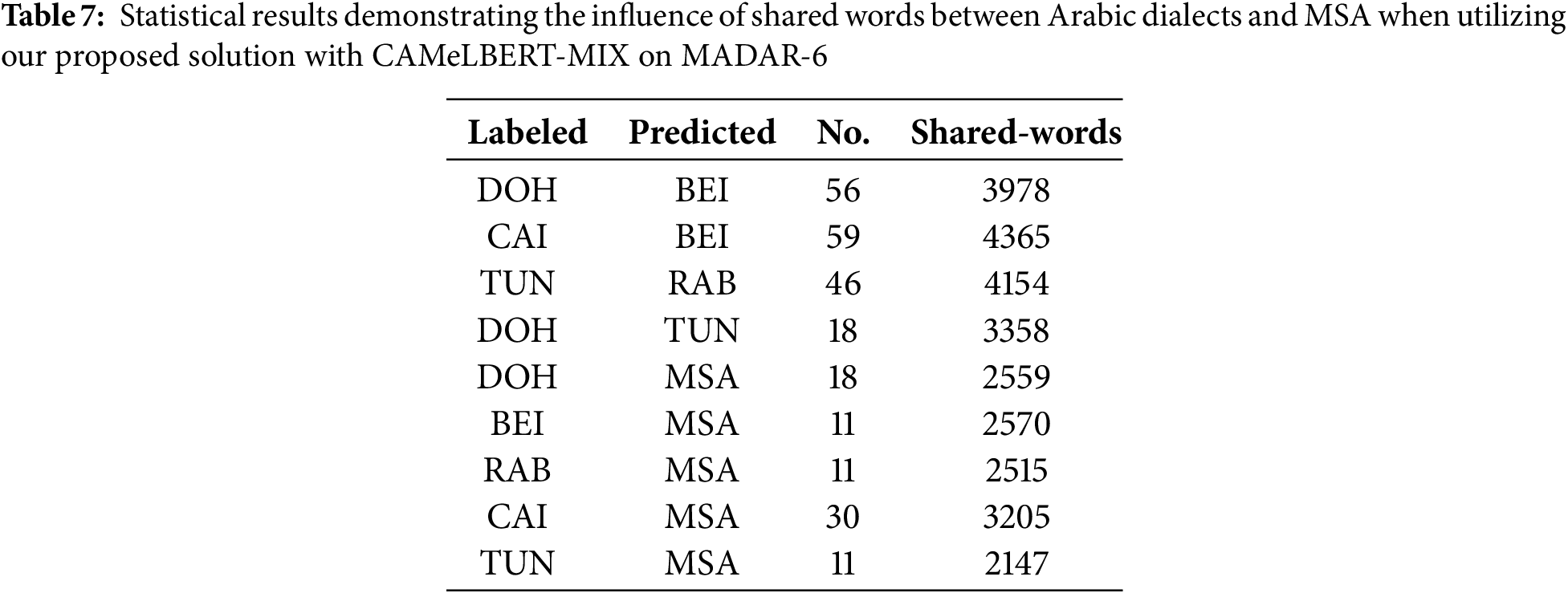

• Influence of MSA on dialects: Sentence 5 القاعة اخر في سيدة. demonstrates the influence of MSA on dialects that are closely related to it. Although the context of sentence 5 contradicts its classification as MSA, the word “سيدة”, is spelled similarly in both the JED dialect, where it means “straight,” and in MSA, where it means “lady”. Due to the absence of distinct dialectal words in the sentence, it was classified as MSA. Sentence 6 حارة. مويه الاقي قادر مني, appears to be closer to a dialectal form rather than MSA. Despite this, it was labeled as the JED dialect but was incorrectly predicted as MSA. Conversely, sentence 9 مكالمتة انتظار في اني بلغة فضلك من, is closer to MSA than to dialectical Arabic. However, the use of the word “من فضلك,” which is frequently found in some dialectical Arabic, was labeled as the CAI dialect; despite this, it was predicted as MSA. The analysis of Table 7 reveals a direct correlation between MSA and Arabic dialects, determined by the shared word count. The statistical results demonstrate a clear and consistent influence of MSA on the Arabic dialects. Investigating the intricate relationship between Arabic dialects and MSA provides valuable insights into the linguistic dynamics influencing dialectal variations. This understanding empowers us to address the complexities arising from shared vocabulary and enhance the classifier’s accuracy in identifying the originating dialects. Note that the abbreviations DAM, ASW, RIY, BAG, TRI, AMM, MUS, ALE, JER, BAS, SFX, DOH, CAI, TUN, RAB, BEI, KHA, JED, and SAL, refer to Arabic cities Damascus, Aswan, Riyadh, Baghdad, Tripoli, Amman, Muscat, Aleppo, Jerusalem, Basra, Sfax, Doha, Cairo, Tunis, Rabat, Beirut, Khartoum, Jeddah, and Salt respectively. We attribute the errors in our proposed model to several key factors, analyzed through selected examples of misclassified sentences in Table 5 and supported by statistical data in Table 6. These causes are summarized as follows:

• Structural similarity across dialects: Some sentences share high structural resemblance across dialects, as observed in sentences 1, 2, 4, 7, 8 in Table 6.

• Resemblance to modern standard Arabic: Certain dialectal expressions closely mirror MSA structure, as noted in sentences (5, 6, 9) in Table 6.

• Sentence brevity: Shorter sentences (e.g., sentence 3 in Table 5) may contribute to classification challenges.

• These points are further reinforced by the statistical data in Table 6, showing:

• Vocabulary overlaps between close dialects: Certain words are shared across similar dialects.

• Vocabulary overlaps with MSA: Lexical similarities between dialects and MSA also complicate model accuracy.

In this paper, we proposed a general adversarial training method. We made use of the CAMeLBERT models in addition to other eight Transformer-based models on a particular NLP task on MADAR-26, MADAR-6, and NADI datasets. We demonstrated that adversarial training prior to generalization can significantly improve robustness and generalization ability, which presents a potential avenue for reconciling the conflicts that have been seen between the two in previous research. Our model achieved a significant improvement in accuracy for BERT in DID, and it showed potential for maximizing the benefits of the unlabeled corpus to increase performance on the DID task. Therefore, this method made it possible to make efficient use of unlabeled data, which will save both the time and effort that would have been spent on data labeling. In future work, to address the challenge of common dialects causing confusion in classification, it is important to ensure that the training data includes a representative sample of these dialects. This can help the model learn the nuances of these dialects and improve its accuracy in classifying them. Additionally, it may be beneficial to use techniques such as phonetic encoding to represent the input data in a way that is more robust to dialectal variation.

Acknowledgement: We gratefully acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for their support through the Small Groups funding initiative. We also extend our appreciation to the Natural Science Foundation of China for their generous funding.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University through Small Groups funding (Project Grant No. RGP.1/243/45). The funding was awarded to Dr. Mohammed Abker. And Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 61901388.

Author Contributions: Mohammed Abdelmajeed led the conceptualization, methodology, experiments, software development, validation, and original draft preparation, and also participated in review, editing, and data collection. Jiangbin Zheng provided supervision and review. Ahmed Murtadha contributed to supervision, result analysis, original draft preparation, editing, and data collection. Youcef Nafa was responsible for methodology and participated in review and editing. Mohammed Abaker handled original draft preparation, editing, and funding acquisition. Muhammad Pervez Akhter contributed to review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The labeled data utilized in this study is globally accessible. The unlabeled data can be accessed via the following link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1qJImRVG-q8hjrSIk7VkcOIv-83Yhm3_v/view?usp=drive_link (accessed on 20 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve human participants, animals, or any sensitive data necessitating formal ethical approval.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://drive.google.com/file/d/1qJImRVG-q8hjrSIk7VkcOIv-83Yhm3_v/view?usp=drive_link (accessed on 20 January 2025).

References

1. Salameh M, Bouamor H, Habash N, editors. Fine-grained arabic dialect identification. Santa Fe, NM, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018 Aug. [Google Scholar]

2. Bouamor H, Hassan S, Habash N. The MADAR shared task on arabic fine-grained dialect identification. Florence, Italy: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Aug. [Google Scholar]

3. Abdul-Mageed M, Alhuzali H, Elaraby M, editors. You tweet what you speak: a city-level dataset of arabic dialects. Miyazaki, Japan: European Language Resources Association (ELRA); 2018 May. [Google Scholar]

4. Elfardy H, Diab M, editors. Sentence level dialect identification in Arabic. Sofia, Bulgaria: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2013 Aug. [Google Scholar]

5. Ionescu RT, Popescu M, editors. UnibucKernel: an approach for Arabic dialect identification based on multiple string kernels. Osaka, Japan: The COLING, Organizing Committee; 2016 Dec. [Google Scholar]

6. Malmasi S, Refaee E, Dras M, editors. Arabic dialect identification using a parallel multidialectal corpus. In: Computational linguistics. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2016. [Google Scholar]

7. Elaraby M, Zahran A, editors. A character level convolutional BiLSTM for Arabic dialect identification. Florence, Italy: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Aug. [Google Scholar]

8. Soliman AB, Eissa K, El-Beltagy SR. AraVec: a set of Arabic word embedding models for use in Arabic NLP. Procedia Comput Sci. 2017;117:256–65. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2017.10.117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Humayun MA, Yassin H, Shuja J, Alourani A, Abas PE. A transformer fine-tuning strategy for text dialect identification. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(8):6115–24. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07944-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mansour M, Tohamy M, Ezzat Z, Torki M, editors. Arabic dialect identification using BERT fine-tuning. Barcelona, Spain: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Dec. [Google Scholar]

11. Attieh J, Hassan F, editors. Arabic dialect identification and sentiment classification using transformer-based models. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022 Dec. [Google Scholar]

12. Devlin J, Chang M-W, Lee K, Toutanova K editors. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Minneapolis, MN, USA: North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

13. Conneau A, Khandelwal K, Goyal N, Chaudhary V, Wenzek G, Guzmán F, et al, editors. Unsupervised cross-lingual representation learning at scale. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul. [Google Scholar]

14. Feng F, Yang Y, Cer D, Arivazhagan N, Wang W, editors. Language-agnostic BERT sentence embedding. Dublin, Ireland: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022 May. [Google Scholar]

15. Antoun W, Baly F, Hajj H.AraBERT: transformer-based model for Arabic language understanding. Marseille, France: European Language Resource Association; 2020 May. p. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

16. Dadas S, Perełkiewicz M, Poświata R, editors. Pre-training polish transformer-based language models at scale. In: Artificial intelligence and soft computing. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

17. Vries WD, Van Cranenburgh A, Bisazza A, Caselli T, Noord GV, Nissim MJA. BERTje: a dutch BERT Model. arXiv:1912.09582. 2019. [Google Scholar]

18. Virtanen A, Kanerva J, Ilo R, Luoma J, Luotolahti J, Salakoski T, et al. Multilingual is not enough: BERT for finnish. arXiv:1912.07076. 2019. [Google Scholar]

19. Abdul-Mageed M, Elmadany A, Nagoudi EMB. ARBERT & MARBERT: deep bidirectional transformers for Arabic. In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 7088–105. [Google Scholar]

20. Inoue G, Alhafni B, Baimukan N, Bouamor H, Habash N, editors. The interplay of variant, size, and task type in Arabic pre-trained language models. Kyiv, Ukraine: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021 Apr. [Google Scholar]

21. Safaya A, Abdullatif M, Yuret D. KUISAIL at SemEval-2020 Task 12: BERT-CNN for offensive speech identification in social media. In: International Committee for Computational Linguistics. 2020. p. 2054–9. [Google Scholar]

22. Lan W, Chen Y, Xu W, Ritter A. An empirical study of pre-trained transformers for Arabic information extraction. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 4727–34. [Google Scholar]

23. Talafha B, Ali M, Za’ter ME, Seelawi H, Tuffaha I, Samir M, et al. Multi-dialect Arabic BERT for country-level dialect identification arXiv:2007.05612. 2020. [Google Scholar]

24. Abdel-Salam R. Dialect & sentiment identification in nuanced Arabic tweets using an ensemble of prompt-based, fine-tuned, and multitask BERT-based models. In: Proceedings of the Seventh Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop (WANLP); 2022; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 452–7. [Google Scholar]

25. Mohammed A, Jiangbin Z, Murtadha A. A three-stage neural model for Arabic dialect identification. Comput Speech Lang. 2023;80:101488. doi:10.1016/j.csl.2023.101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Garg S, Ramakrishnan G. BAE: BERT-based adversarial examples for text classification. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 6174–81. [Google Scholar]

27. Croce D, Castellucci G, Basili R. GAN-BERT: generative adversarial learning for robust text classification with a bunch of labeled examples. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 2114–9. [Google Scholar]

28. Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial nets. NIPS’14: Proc 28th Int Conf Neural Inform Process Syst. 2014;2:2672–80. [Google Scholar]

29. Hendrycks D, Liu X, Wallace E, Dziedzic A, Krishnan R, Song D. Pretrained transformers improve out-of-distribution robustness. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 2744–51. [Google Scholar]

30. Ramponi A, Plank B. Neural unsupervised domain adaptation in NLP—a survey. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2020; Barcelona, Spain. p. 6838–55. [Google Scholar]

31. Vu T-T, Phung D, Haffari G. Effective unsupervised domain adaptation with adversarially trained language models. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 6163–73. [Google Scholar]

32. Ye H, Tan Q, He R, Li J, Ng HT, Bing LJA. Feature adaptation of pre-trained language models across languages and domains for text classification. arXiv:2009.11538. 2020. [Google Scholar]

33. Chen T, Huang S, Wei F, Li J. Pseudo-label guided unsupervised domain adaptation of contextual embeddings. In: Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Domain Adaptation for NLP; 2021; Kyiv, Ukraine. p. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

34. Yusuf M, Torki M, El-Makky N. Arabic dialect identification with a few labeled examples using generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 12th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing; 2020. p. 196–204. doi:10.18653/v1/2022.aacl-main. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. El Mekki A, El Mahdaouy A, Berrada I, Khoumsi A. Domain adaptation for arabic cross-domain and cross-dialect sentiment analysis from contextualized word embedding. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2021. p. 2824–37. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.naacl-main. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. El Mekki A, El Mahdaouy A, Berrada I, Khoumsi A. AdaSL: an unsupervised domain adaptation framework for Arabic multi-dialectal sequence labeling. Inform Process Manage. 2022;59(4):102964. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2022.102964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Abdul-Mageed M, Keleg A, Elmadany A, Zhang C, Hamed I, Magdy W, et al. NADI 2024: the fifth nuanced arabic dialect identification shared task. In: Proceedings of the Second Arabic Natural Language Processing Conference; 2024 Aug; Bangkok, Thailand: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 709–28. [Google Scholar]

38. Karoui A, Gharbi F, Kammoun R, Laouirine I, Bougares F. ELYADATA at NADI, 2024 shared task: Arabic dialect identification with similarity-induced mono-to-multi label transformation. In: Proceedings of the Second Arabic Natural Language Processing Conference; 2024 Aug; Bangkok, Thailand, Bangkok, Thailand: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 758–63. [Google Scholar]

39. Ahmed M, Alfasly S, Wen B, Addeen J, Ahmed M, Liu Y. AlclaM: arabic dialect language model. In: Proceedings of the Second Arabic Natural Language Processing Conference; 2024 Aug; Bangkok, Thailand. p. 153–59. [Google Scholar]

40. Alahmari S, Atwell E, Alsalka MA. Saudi Arabic multi-dialects identification in social media texts. In: Intelligent computing. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024. [Google Scholar]

41. Alqulaity EY, Yafooz WMS, Alourani A, Jaradat A. Arabic dialect identification in social media: a comparative study of deep learning and transformer approaches. Intell Autom Soft Comput. 2024;39(5):907–28. doi:10.32604/iasc.2024.055470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Biadsy F, Hirschberg J, Habash N. Spoken Arabic dialect identification using phonotactic modeling. In: Proceedings of the EACL 2009 Workshop on Computational Approaches to Semitic Languages; 2009 Mar; Athens, Greece. p. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

43. Harrat S, Meftouh K, Smaïli K. Creating parallel Arabic dialect corpus: pitfalls to avoid. In: 18th International Conference on Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing (CICLING); 2017; Budapest, Hungary. [Google Scholar]

44. Habash N, Eryani F, Khalifa S, Rambow O, Abdulrahim D, Erdmann A, et al. Unified guidelines and resources for Arabic dialect orthography. Miyazaki, Japan: European Language Resources Association (ELRA); 2018. [Google Scholar]

45. Davison J, Feldman J, Rush A. Commonsense knowledge mining from pretrained models. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); 2019 Nov; Hong Kong, China: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 1173–8. [Google Scholar]

46. Peters ME, Ruder S, Smith NA. To tune or not to tune? Adapting pretrained representations to diverse tasks. In: Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Representation Learning for NLP (RepL4NLP-2019); 2019; Florence, Italy. p. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

47. Du C, Sun H, Wang J, Qi Q, Liao J. Adversarial and domain-aware BERT for cross-domain sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul; Online: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 4019–28. [Google Scholar]

48. Ben-David S, Blitzer J, Crammer K, Kulesza A, Pereira F, Vaughan JW. A theory of learning from different domains. Mach Learn. 2010;79(1):151–75. doi:10.1007/s10994-009-5152-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ganin Y, Lempitsky V.Unsupervised domain adaptation by backpropagation. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning. 2015. Vol. 37. p. 1180–9. [Google Scholar]

50. Bouamor H, Habash N, Salameh M, Zaghouani W, Rambow O, Abdulrahim D, et al. The MADAR Arabic dialect corpus and lexicon. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018); 2018 May; Miyazaki, Japan: European Language Resources Association (ELRA). [Google Scholar]

51. Abdul-Mageed M, Zhang C, Bouamor H, Habash N. NADI 2020: the first nuanced arabic dialect identification shared task. In: Proceedings of the Fifth Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop; 2020 Dec; Barcelona, Spain: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

52. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017; Long Beach, CA, USA: Curran Associates Inc. p. 6000–10. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools