Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deterministic Convergence Analysis for GRU Networks via Smoothing Regularization

1 School of Cybersecurity, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072, China

2 Unmanned System Research Institute, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072, China

3 School of Artificial Intelligence, Optics and Electronics (iOPEN), Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072, China

* Corresponding Author: Dengxiu Yu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(2), 1855-1879. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.061913

Received 06 November 2024; Accepted 11 February 2025; Issue published 16 April 2025

Abstract

In this study, we present a deterministic convergence analysis of Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks enhanced by a smoothing regularization technique. While GRU architectures effectively mitigate gradient vanishing/exploding issues in sequential modeling, they remain prone to overfitting, particularly under noisy or limited training data. Traditional regularization, despite enforcing sparsity and accelerating optimization, introduces non-differentiable points in the error function, leading to oscillations during training. To address this, we propose a novel smoothing regularization framework that replaces the non-differentiable absolute function with a quadratic approximation, ensuring gradient continuity and stabilizing the optimization landscape. Theoretically, we rigorously establish three key properties of the resulting smoothing -regularized GRU (SL1-GRU) model: (1) monotonic decrease of the error function across iterations, (2) weak convergence characterized by vanishing gradients as iterations approach infinity, and (3) strong convergence of network weights to fixed points under finite conditions. Comprehensive experiments on benchmark datasets-spanning function approximation, classification (KDD Cup 1999 Data, MNIST), and regression tasks (Boston Housing, Energy Efficiency)-demonstrate SL1-GRUs superiority over baseline models (RNN, LSTM, GRU, L1-GRU, L2-GRU). Empirical results reveal that SL1-GRU achieves 1.0%–2.4% higher test accuracy in classification, 7.8%–15.4% lower mean squared error in regression compared to unregularized GRU, while reducing training time by 8.7%–20.1%. These outcomes validate the method’s efficacy in balancing computational efficiency and generalization capability, and they strongly corroborate the theoretical calculations. The proposed framework not only resolves the non-differentiability challenge of regularization but also provides a theoretical foundation for convergence guarantees in recurrent neural network training.Keywords

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) have emerged as a powerful class of neural networks, particularly adept at modeling sequential data due to their ability to retain and utilize temporal dependencies [1]. These networks have demonstrated remarkable success across various domains, including natural language processing, speech recognition, and time-series forecasting [2]. However, the application of RNN is not without challenges. One of the primary issues is the vanishing and exploding gradient problem, which can significantly hinder the training of deep RNN [3,4]. To address this, several variants of RNN have been proposed, such as Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) [5,6]. These architectures incorporate gating mechanisms to selectively retain or forget information, effectively mitigating gradient-related issues and improving performance [7]. LSTM, for instance, uses a combination of input, forget, and output gates to control the flow of information, allowing the network to retain relevant information over extended sequences [8]. Similarly, GRU simplifies the gating mechanism while maintaining comparable performance, making them computationally more efficient [9].

Despite the advancements in RNN architectures, the issue of overfitting remains a significant challenge, particularly when dealing with limited or noisy data [10]. Overfitting occurs when a model learns to memorize the training data instead of generalizing to unseen samples, leading to poor performance on test data [11,12]. Regularization techniques have been introduced to address this, aiming to improve the generalization ability of neural networks by controlling their complexity. Common regularization methods, such as

where

In this research, we propose the use of GRU networks with smoothing

This research primarily focuses on analyzing the monotonicity, weak convergence, and strong convergence properties of GRU networks with smoothing

(1) The smoothing

(2) Under given conditions and assumptions, the monotonicity, weak convergence, and strong convergence of SL1-GRU are theoretically demonstrated. The network’s error function decreases monotonically with the increasing number of iterations. As iterations approach infinity, weak convergence is demonstrated by the error function’s gradient approaching zero. Strong convergence means network weights can converge to a fixed point under defined conditions.

(3) The theoretical results are validated through experiments on approximation, classification, and regression tasks. The experimental results show that GRU networks with smoothing

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 explores the GRU network structure and the parameter iteration mechanism after introducing smoothing

2 GRU Based on Regularization Method

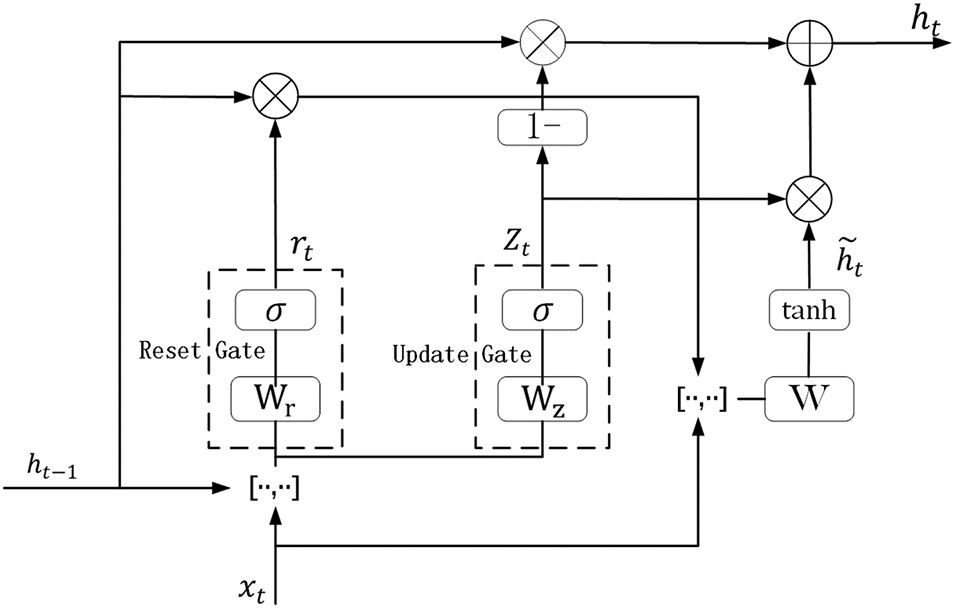

As a streamlined variant of LSTM, GRU features just two gate mechanisms: an update gate and a reset gate [32]. The internal configuration of GRU, shown in Fig. 1, together with the standard forward propagation equations, is detailed below:

Figure 1: Structure of GRU

The following are the explanations for the related symbols:

• The symbol

•

•

•

• At time

• The symbols

•

•

In (2),

Obviously, the weight matrix in other Eqs. (3)–(5) can be also rewritten in the same form as (6). For the convenience of subsequent analysis, we set the biases

If

where

2.2 Gradient Learning Method with Smoothing

The standard approach to achieve

This can be written as:

where

However, there is no derivative of the

The smoothing coefficient

Figure 2: Influence of smoothing coefficient on fitting degree

By incorporating a smooth approximation function into the error propagation mechanism of

The element

here,

The optimization algorithm, Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), is frequently used to train GRU. To achieve the fastest reduction of the error function E, the direction of weight changes should be the same as the negative gradient of E in the weight matrix. The learning rate, symbolized by

This equation indicates that during each iteration, SL1-GRU updates the weights by deducting the result of multiplying the learning rate

Define

Similarly, define:

For each weight matrix, the partial derivatives of E are as follows:

For the output weight matrix

where

According to (17) and (22) to (28), the weights are updated iteratively by:

Based on the above analysis, the SL1GRU algorithm flow is presented in Algorithm 1.

This section presents the theoretical findings of GRU networks with smoothing

(A1) For

(A2)

(A3) There exists a bounded region

(A4) A compact set

Our main results are as follows:

Theorem 1. Monotonicity

Assume the error function

Theorem 2. Weak Convergence

Assuming that conditions (A1)–(A3) hold, then the weight sequence

Theorem 3. Strong Convergence

Furthermore, if assumption (A4) also holds, the subsequent strong convergence outcome can be derived:

where

For clarity and convenience, certain notations will be introduced for future reference.

4 Experimental Results and Analysis

The experiment is divided into three distinct parts. The initial part involves an analysis of theoretical outcomes through the approximation of function. Subsequently, the generalization capability and sparsity of the model are evaluated using regression and classification datasets from the UCI Machine Learning Repository.

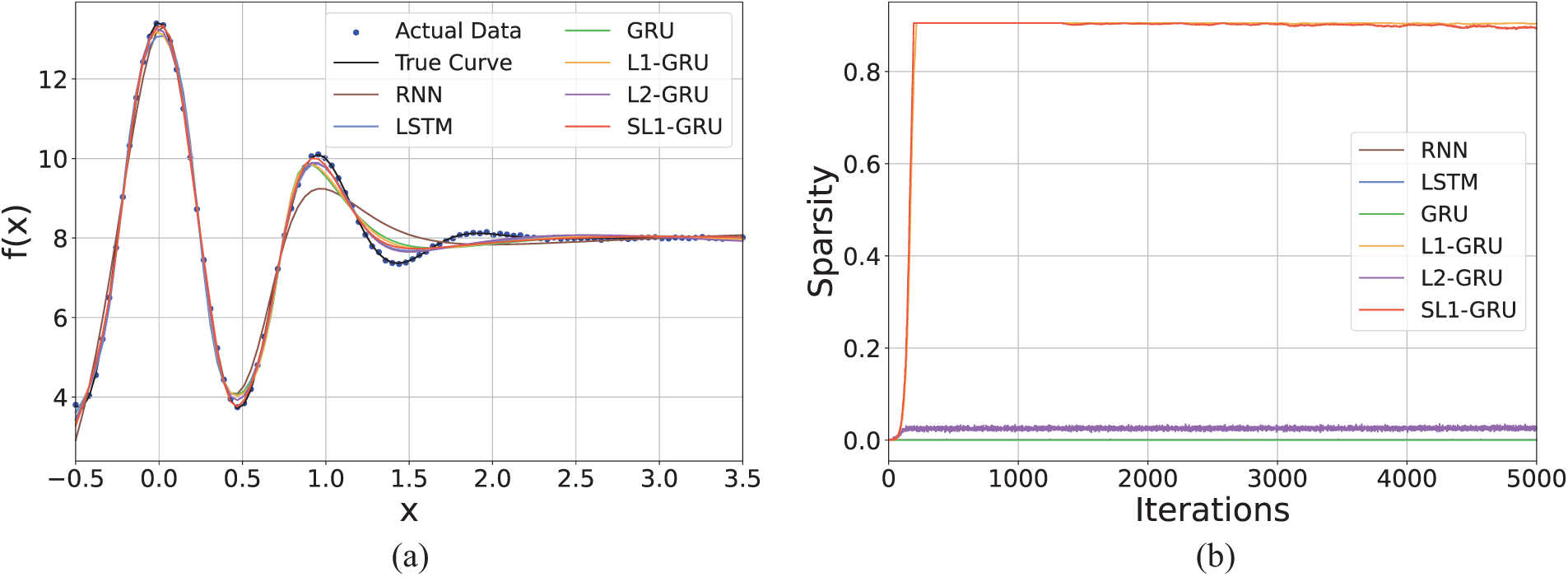

To demonstrate the generalization capabilities of SL1-GRU, we approximate a one-dimensional function

Nonlinear oscillatory function:

The peaks function, commonly used in numerical experiments, defined as:

For the nonlinear oscillatory function (40), 100 points are uniformly distributed in the interval

Fig. 3a shows the approximation performance of RNN, LSTM, GRU, L1-GRU, L2-GRU, and SL1-GRU for the nonlinear target function

Figure 3: Approximation perfomance for one-dimensional function (a) results of approximation (b) sparsity of models

Similarly, we approximate the two-dimensional function using the same approaches, with the approximation results of SL1-GRU presented in Fig. 4. The results highlight SL1-GRU’s ability to effectively capture global trends and local variations.

Figure 4: Approximation result of SL1-GRU for two-dimensional function (a) two-dimensional function (b) approximation function

This part presents an evaluation and comparison of the classification efficacy for RNN, LSTM, GRU, L1-GRU, L2-GRU, and SL1-GRU. Table 1 is a summary of the dataset utilized in the simulation experiment. The network weights are randomly initialized in

As shown in Fig. 5, we use grid search to explore the hyperparameter space by testing combinations of learning rate

Figure 5: Test accuracy of SL1-GRU on the wine dataset under different parameter combinations;

Table 3 compares the training accuracy, test accuracy, sparsity, and training time of different models on the same dataset. These experimental results represent the average values obtained over 10 trials. Sparsity, defined as the ratio of elements in the neural network’s weight matrix that are less than

where the number of elements in the weight matrix that are less than

From Fig. 6, it can be observed that the loss function curve of SL1-GRU monotonically decreases and gradually stabilizes at zero as the number of iterations increases, which verifies Theorem 1. Meanwhile, in Fig. 6b, the gradient curve of SL1-GRU decreases the fastest, and as the number of iterations approaches infinity, its gradient also tends to zero, consistent with Theorem 2. Fig. 6c shows that the weight curves of L1-GRU and SL1-GRU do not grow indefinitely, indicating that both regularization methods effectively suppress weight growth. Among them, SL1-GRU is more effective in constraining network weights, stabilizing them around a constant value of approximately 140, aligning with Theorem 3.

Figure 6: The performance of RNN, LSTM, GRU, L1-GRU, L2-GRU and SL1-GRU on MNIST dataset; the shaded area presents the mean

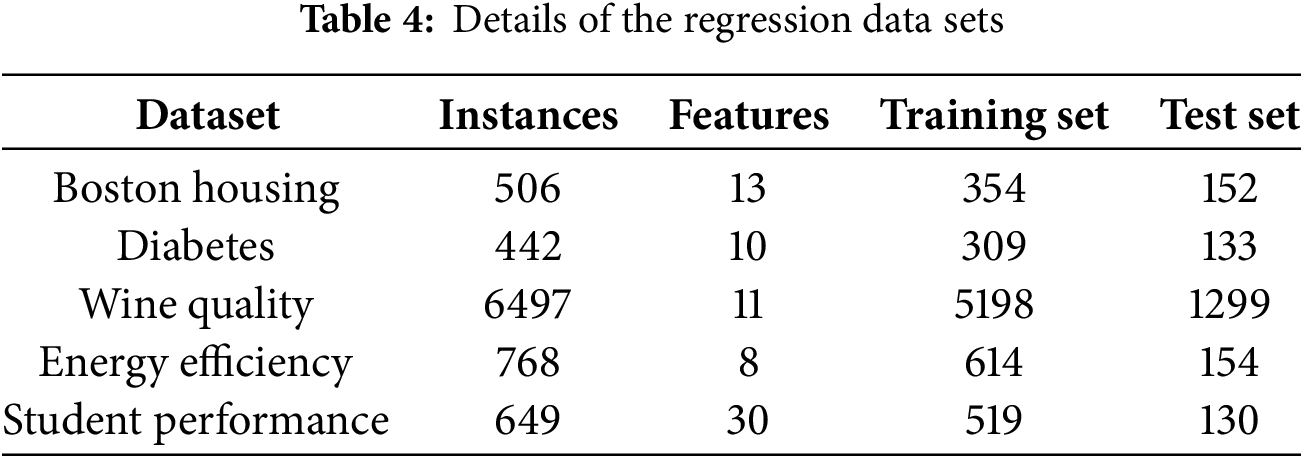

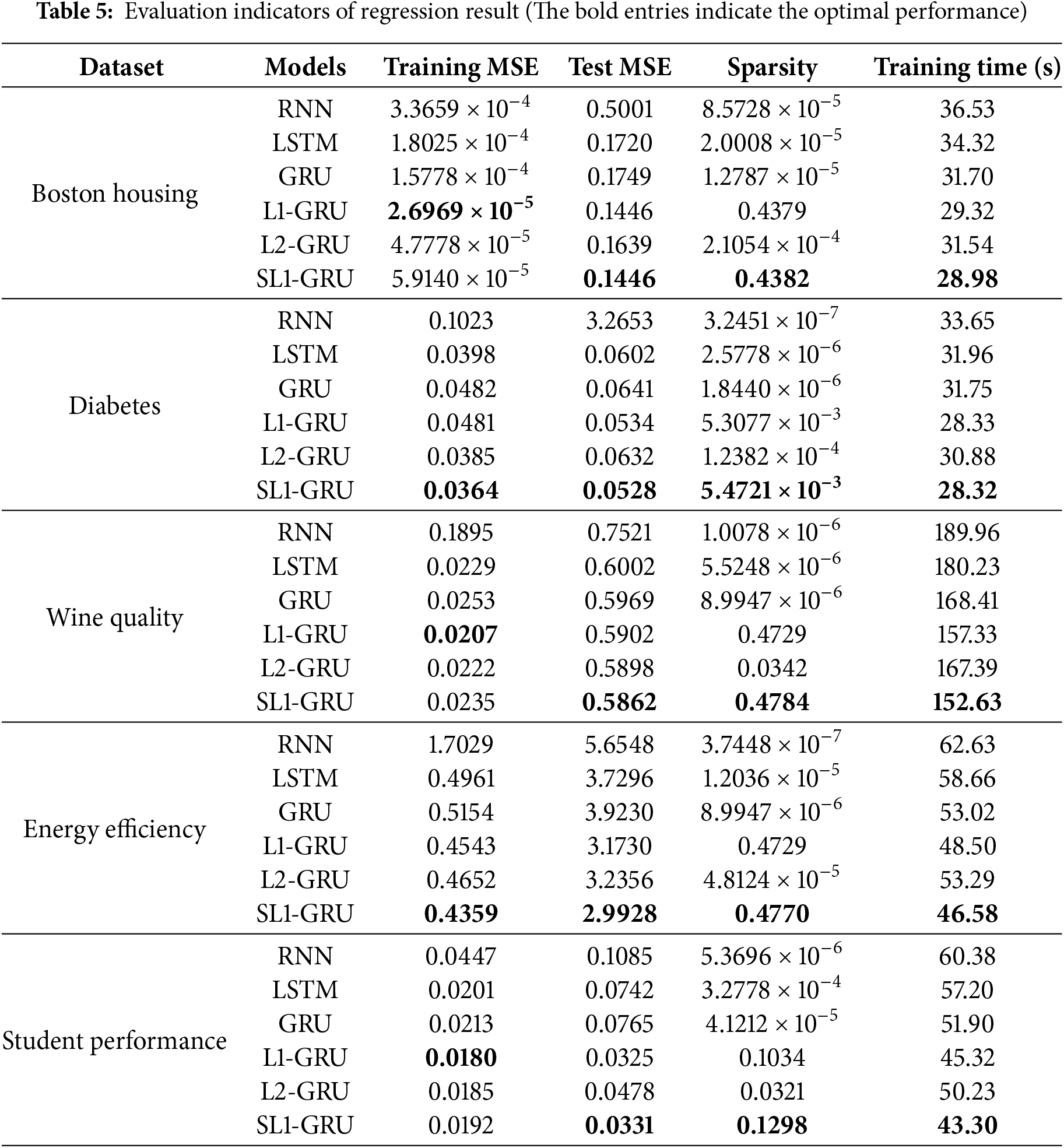

The performance of SL1-GRU in regression tasks is also considered. The dataset utilized in this part is detailed in Table 4. For RNN, LSTM, GRU, L1-GRU, L2-GRU, and SL1-GRU, the hidden layer is designed with 32 nodes. The nodes in both the input and output layers are configured based on the dataset’s features and labels, respectively. The learning rate is established at

In the evaluation of regression models, the standard metric used is Mean Squared Error (MSE), which is calculated using the following formula:

where

Table 5 shows that the Test MSE of SL1-GRU is consistently the smallest, indicating that it performs the best on the test set and has the strongest generalization ability. From the perspective of sparsity, the network weights of SL1-GRU remain the sparsest, which suggests that it eliminates unimportant parameters to enhance the computational efficiency of the model while maintaining its excellent performance.

This article proposes a GRU with smoothing

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their valuable work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholarship (No. 62025602), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U22B2036, 11931015), the Fok Ying-Tong Education Foundation China (No. 171105), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. G2024WD0151) and in part by the Tencent Foundation and XPLORER PRIZE.

Author Contributions: Qian Zhu: Conceptualization, Software, Writing—review & editing. Qian Kang: Data curation, Writing—review. Tao Xu: Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology. Dengxiu Yu: Methodology, Supervision, Validation. Zhen Wang: Supervision, Validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Detailed Proof: Lemma A1. The function

Proof of Lemma A1. □

A new function is constructed as:

where

Taking the derivative of

then,

Proof of Theorem 1. □

By (15), the errors at the k-th and (k+1)-th iterations are given as:

and the difference between them is:

where Lagrange remainder

in the above equation,

To simplify, we use the following notation:

According to Lemma A1,

Using transition variables

where

continuing from the previous step and according to assumption (A1),

and

and

further, we have

From the previous equation (A15) to (A23), it follows that

then

where

The next step is to focus on deriving (A11) to (A13):

and

and

next,

Building on the previous equations and Assumption (A3),

where

This completes the proof of Theorem 1.

Proof of Theorem 2. □

Let

with

when

Consequently

This concludes the proof of Theorem 2.

Proof of Theorem 3. □

Lemma A2. Consider

then, there has

According to assumption (A4), Lemma A2 and (A35), a point

Thus the proof to Theorem 3 is completed.

References

1. Agarap AFM. A neural network architecture combining gated recurrent unit (GRU) and support vector machine (SVM) for intrusion detection in network traffic data. In: Proceedings of the 2018 10th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing; 2018; Macau, China. p. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

2. Liang X, Wang J. A recurrent neural network for nonlinear optimization with a continuously differentiable objective function and bound constraints. IEEE Transact Neural Netw. 2000;11(6):1251–62. doi:10.1109/72.883412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Hochreiter S. Untersuchungen zu dynamischen neuronalen Netzen. Diploma, Technische Universität München. 1991;91(1):31. [Google Scholar]

4. Bengio Y, Simard P, Frasconi P. Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Transact Neural Netw. 1994;5(2):157–66. doi:10.1109/72.279181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–80. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Cho K, Van Merriënboer B, Gulcehre C, Bahdanau D, Bougares F, Schwenk H, et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv:14061078. 2014. [Google Scholar]

7. Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Deep learning. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

8. Shewalkar A, Nyavanandi D, Ludwig SA. Performance evaluation of deep neural networks applied to speech recognition: rNN, LSTM and GRU. J Artif Intell Soft Comput Res. 2019;9(4):235–45. doi:10.2478/jaiscr-2019-0006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zaman U, Khan J, Lee E, Hussain S, Balobaid AS, Aburasain RY, et al. An efficient long short-term memory and gated recurrent unit based smart vessel trajectory prediction using automatic identification system data. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(1):1789–808. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.056222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Alzubaidi L, Zhang J, Humaidi AJ, Al-Dujaili A, Duan Y, Al-Shamma O, et al. Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J Big Data. 2021;8:1–74.doi:10.1186/s40537-021-00444-8. [Google Scholar]

11. Bejani MM, Ghatee M. A systematic review on overfitting control in shallow and deep neural networks. Artif Intel Rev. 2021;54(8):6391–438. doi:10.1007/s10462-021-09975-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Schittenkopf C, Deco G, Brauer W. Two strategies to avoid overfitting in feedforward networks. Neural Netw. 1997;10(3):505–16. doi:10.1016/S0893-6080(96)00086-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li H, Kadav A, Durdanovic I, Samet H, Graf HP. Pruning filters for efficient convnets. arXiv:160808710. 2016. [Google Scholar]

14. Girosi F, Jones M, Poggio T. Regularization theory and neural networks architectures. Neural Comput. 1995;7(2):219–69. doi:10.1162/neco.1995.7.2.219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Quasdane M, Ramchoun H, Masrour T. Sparse smooth group L1°L1/2 regularization method for convolutional neural networks. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;284:111327. [Google Scholar]

16. Van Laarhoven T. L2 regularization versus batch and weight normalization. arXiv:170605350. 2017. [Google Scholar]

17. Santos CFGD, Papa JP. Avoiding overfitting: a survey on regularization methods for convolutional neural networks. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;54(10s):1–25. doi:10.1145/3510413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Srivastava N, Hinton G, Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J Mach Learn Res. 2014;15(1):1929–58. [Google Scholar]

19. Wu L, Li J, Wang Y, Meng Q, Qin T, Chen W, et al. R-drop: regularized dropout for neural networks. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2021;34:10890–905. [Google Scholar]

20. Israr H, Khan SA, Tahir MA, Shahzad MK, Ahmad M, Zain JM. Neural machine translation models with attention-based dropout layer. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;75(2):2981–3009. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.035814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Park MY, Hastie T. L1-regularization path algorithm for generalized linear models. J Royal Statist Soc Ser B: Statist Method. 2007;69(4):659–77. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9868.2007.00607.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Salehi F, Abbasi E, Hassibi B. The impact of regularization on high-dimensional logistic regression. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2019;32:1310–20. [Google Scholar]

23. Shi X, Kang Q, An J, Zhou M. Novel L1 regularized extreme learning machine for soft-sensing of an industrial process. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2021;18(2):1009–17. doi:10.1109/TII.2021.3065377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang H, Wu W, Yao M. Boundedness and convergence of batch back-propagation algorithm with penalty for feedforward neural networks. Neurocomputing. 2012;89(3):141–6. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2012.02.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang J, Wu W, Zurada JM. Computational properties and convergence analysis of BPNN for cyclic and almost cyclic learning with penalty. Neural Netw. 2012;33(4):127–35. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2012.04.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kang Q, Fan Q, Zurada JM. Deterministic convergence analysis via smoothing group Lasso regularization and adaptive momentum for Sigma-Pi-Sigma neural network. Inform Sci. 2021;553(1):66–82. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2020.12.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yu D, Kang Q, Jin J, Wang Z, Li X. Smoothing group L1/2 regularized discriminative broad learning system for classification and regression. Pattern Recognit. 2023;141(10–11):109656. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang J, Wen Y, Ye Z, Jian L, Chen H. Convergence analysis of BP neural networks via sparse response regularization. Appl Soft Comput. 2017;61:354–63. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2017.07.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Fan Q, Kang Q, Zurada JM, Huang T, Xu D. Convergence analysis of online gradient method for high-order neural networks and their sparse optimization. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;35(12):18687–701. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3319989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kang Q, Fan Q, Zurada JM, Huang T. A pruning algorithm with relaxed conditions for high-order neural networks based on smoothing group L1/2 regularization and adaptive momentum. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;257:109858. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Fan Q, Peng J, Li H, Lin S. Convergence of a gradient-based learning algorithm with penalty for ridge polynomial neural networks. IEEE Access. 2021;9:28742–52. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3048235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yang S, Yu X, Zhou Y. LSTM and GRU neural network performance comparison study: taking yelp review dataset as an example. In: 2020 International Workshop on Electronic Communication and Artificial Intelligence (IWECAI); 2020. Shanghai, China: IEEE. p. 98–101. [Google Scholar]

33. Ma R, Miao J, Niu L, Zhang P. Transformed L1 regularization for learning sparse deep neural networks. Neural Netw. 2019;119:286–98. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2019.08.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Campi MC, Caré A. Random convex programs with L1-regularization: sparsity and generalization. SIAM J Cont Optimiza. 2013;51(5):3532–57. doi:10.1137/110856204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools