Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Application of Multi-Criteria Decision and Simulation Approaches to Selection of Additive Manufacturing Technology for Aerospace Application

1 Department of Mechatronics Engineering, Bells University of Technology, Ota, P.M.B. 1015, Nigeria

2 Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, 7535, South Africa

3 Centre for Climate Change, Water Security and Disaster Management, Department of Civil Engineering, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, 0183, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Ilesanmi Afolabi Daniyan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Design, Optimisation and Applications of Additive Manufacturing Technologies)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(2), 1623-1648. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.062092

Received 10 December 2024; Accepted 26 March 2025; Issue published 16 April 2025

Abstract

This study evaluates the Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) as a multi-criteria decision (MCD) support tool for selecting appropriate additive manufacturing (AM) techniques that align with cleaner production and environmental sustainability. The FAHP model was validated using an example of the production of aircraft components (specifically fuselage) employing AM technologies such as Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM), laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF), Binder Jetting (BJ), Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), and Laser Metal Deposition (LMD). The selection criteria prioritized eco-friendly manufacturing considerations, including the quality and properties of the final product (e.g., surface finish, high strength, and corrosion resistance), service and functional requirements, weight reduction for improved energy efficiency (lightweight structures), and environmental responsibility. Sustainability metrics, such as cost-effectiveness, material efficiency, waste minimization, and environmental impact, are central to the evaluation process. A computer-aided modeling approach was also used to simulate the performance of aluminum (AA7075 T6), steel (304), and titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) for fuselage development. The results demonstrate that MCD approaches such as FAHP can effectively guide the selection of AM technologies that meet functional and technical requirements while minimizing environmental degradation footprints. Furthermore, the aluminum alloy outperformed the other materials investigated in the simulation with the lowest stress concentration and least deformation. This study contributes to advancing cleaner production practices by providing a decision-making framework for sustainable and eco-friendly manufacturing, enabling manufacturers to adopt AM technologies that promote environmental responsibility and sustainable development, while maintaining product quality and performance.Keywords

List of Acronyms

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| AHP | Analytical Hierarchy Process |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BJ | Binder Jetting |

| CSAM | Cold Spray Additive Manufacturing |

| CI | Consistency Index |

| CR | Consistency Ratio |

| DFM | Design for Manufacturing |

| EBM | Electron Beam Melting |

| FAHP | Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modelling |

| LMD | Laser Metal Deposition |

| L-PBF | Laser Powder Bed Fusion |

| MCD | Multi-Criteria Decision |

| RI | Random Index |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| SLM | Selective Laser Melting |

| SLS | Selective Laser Sintering |

| TFN | Triangular Fuzzy Numbers |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| WAAM | Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing |

| 3-dimensional | 3-dimensional |

Additive Manufacturing (AM) is an emerging technology that deals with the development of physical objects from three-dimensional digital models by depositing them in layers [1,2]. The concept of AM, commonly known as 3-dimensional (3D) printing technology, first emerged in the 1940s [3] and has continued to gain increasing attention and applications across major industries for rapid prototyping and product development. The use of AM continues to revolutionize manufacturing processes because of its short production cycle time, flexibility of design, just-in-time production, and efficient material and energy use [1,4–7]. Thus, AM has several advantages over conventional manufacturing processes [8–10]. Conversely, the demand for sustainable industrial practices has intensified in recent years, because of the phenomenon of climate change and other environmental concerns. The cleaner production phenomenon emphasizes minimizing the environmental impact, reducing waste, and improving resource efficiency in production processes while maximizing efficiency, resource utilization, and sustainability. Within this context of advancing sustainability, computer simulations have emerged as essential tools that assist manufacturers in the design, testing, and optimization of manufacturing processes and products in computational environments before implementing them in real-world scenarios. The convergence of computer simulation technologies in industrial processes, cleaner production, and AM represents a significant leap in industrial innovation, fostering cleaner manufacturing and eco-friendly production practices. It could also be a pathway to meet the requirements of sustainability, a circular economy, and lean manufacturing.

Manufacturing industries can now strive to achieve excellent product quality that meets customers’ needs, while also achieving savings in resource consumption and environmental responsibility. To promote sustainability, manufacturing industries have adopted techniques to reduce weight and waste. For instance, the use of selective laser melting (SLM) (one of the widely deployed AM technologies) now enables the creation of products with uniform and fine microstructures with improved mechanical properties, such as strength and ductility, while achieving a bulk weight reduction compared to conventional molding processes. This technology can also be used for the production of intricate shapes, such as honeycomb and hollow structures, with improved thermal and acoustic properties, which are difficult to achieve conventionally. Light weight biomedical devices and products can now be manufactured via AM, promoting portability, while in the automobile and aerospace industries, light weight components promote cost savings and energy efficiency with a substantial reduction in emissions. This makes the technology more environmentally friendly.

Another area where AM technology drives sustainable and environmentally friendly manufacturing is rapid prototyping and reduction in manufacturing lead time. With this, manufacturing industries can get their products to the markets in a time- and cost-effective manner, thereby gaining a competitive advantage without sacrificing quality. Unlike conventional manufacturing methods that require specialized jigs, fixtures, and standard molds, AM can be used to develop small batches of customized parts or products tailored towards specific or preferential customer needs. In line with the principles of lean manufacturing, AM contributes to a circular economy through waste reduction. The conventional manufacturing approach is subtractive in nature, involving the machining of excess materials from a solid material block, which may contribute to waste generation. Furthermore, AM promotes just-in-time production, thereby reducing the risk of tying up capital on inventory. This ensures that parts are available for sale or maintenance purposes on demand. This implies that AM technology can enhance the supply value chain from the design phase through the product end-of-life. In addition, AM can promote localization using locally sourced materials. In other words, raw materials for AM are locally available and cost-effective, which promotes indigenous capabilities. It also promotes distributed manufacturing through the manufacturing of products close to the point of need, thus eliminating the need to transport products over long distances. However, with the increasing use of AM, there are still some challenges in mitigating its use in manufacturing. These include the initial cost set up, especially for small-scale businesses, slow speed of production, limited expertise, low awareness, insufficient support infrastructure, and the need for post-processing, which may affect the product quality and functional requirements if it is not precisely and carefully carried out, as well as selection of the appropriate materials and AM process that suit a particular manufacturing need [6,11–13]. A careful examination of the advantages and disadvantages of AM technology shows that its merits outweigh its disadvantages. Thus, technology has the potential to enhance the seamless delivery of products and services through innovation and sustainability. Therefore, to fully harness the benefits of AM technology, including environmentally responsible production, a practical decision support framework must be developed as a guide for AM technology selection [14]. Thus, this study aims to evaluate the Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) as a multi-criteria decision (MCD) tool for ranking suitable AM techniques such as Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM), laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF), Binder Jetting (BJ), Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), and Laser Metal Deposition (LMD) for the production of aircraft components (specifically, fuselage). To fully harness the potential of Additive Manufacturing (AM), a robust decision support system is required to guide the selection of the most appropriate AM technology for specific applications. This study attempts to solve the problem of incorrect selection of AM technology during product development through the development of a decision framework that can assist manufacturers in selecting the right AM technology for specific product development. The novelty of this study lies in the development of a decision framework that can guide manufacturers in the selection of appropriate AM technology and the simulation of different materials such as aluminum, steel alloys, and titanium alloys for aerospace applications. This study contributes empirically, theoretically, and methodologically to knowledge through the development of MCD and selection frameworks that can assist manufacturers in selecting the right AM technology for product development. The structure of this paper is arranged as follows: Section 2 presents a literature review, and Section 3 presents the methodology used in this study. Section 4 details the results and discussion, and Section 5 presents the MCD framework for the selection of the appropriate AM technique. This study ends with conclusions and recommendations, acknowledging the limitations of this study and providing directions for future studies.

2.1 Potentials of AM in the Manufacturing Sector

Additive manufacturing, otherwise referred to as 3D printing technology, is an evolving transformative technology that supports the development of physical objects from digital models by depositing them in layers, offering the potential for cleaner production and eco-friendly manufacturing across multiple sectors and is widely acknowledged as a time- and cost-effective technology for the manufacturing of functional prototypes during product development and testing. Their applications encompass a wide range of spectra for direct and indirect applications. Thus, AM technology addresses the need for effective product design and production efficiency in a dynamic and competitive global economy. AM technology has diverse applications in various sectors. With progressive advancements in computing power and technologies in the last few decades and the evolution of more impressive interactive user interface computer simulations now allow users of AM technologies and product developers to model complex products and systems, predict and optimize their outcomes, and allow the alignment of production processes to standard regulatory guidelines, all without real-world trials [15,16]. The use of finite element analyses to predict and mitigate stress-induced deformations in products; multi-physics simulations that integrate thermal, mechanical, and fluid dynamics to study complex interactions in AM processes; molecular dynamics and discrete event simulations to model workflows and production processes and eliminate bottlenecks and wastes; computational modeling and simulations have contributed to the potential and development of AM, allowing industries to evaluate the sustainability of processes and products without consuming physical resources, while enabling resource use and consumption efficiency as well as predetermining environmental impacts and their effects on the life cycle of specific operations and components. In turn, this has advanced the course of shifting paradigms towards more environmentally responsible production. As demonstrated by Attaran [7], developers can now precisely pre-determine production types, rates, quality, quantity, and amount of resources in terms of energy and cost that will be consumed during production per unit of the expected product. This paves the way for the reduction of scrap, waste in any form, emissions, and structural liabilities, while opening a vista for the integration of closed-loop production systems, recycling, and data-driven decision management for adopting cleaner technologies and renewable energy systems, such as solar-powered production units. Benefits include savings in cost and time; conservation of production inputs; possession of actionable insights to improve processes and align with sustainability goals; reduction in risks associated with changes to established processes; and the acceleration of product, system, and technological development that guarantees sustainability and environmental sustainability. As AM technology continues to advance, integrating simulations with emerging tools, such as digital twins and Artificial Intelligence (AI), will further empower manufacturers to achieve cleaner production goals, advance with the adoption of robotics and automation in manufacturing, and enable smarter, cleaner production systems.

Elhazmiri et al. [13] stated that AM technologies have been deployed in the education sector, as well as for research and development (R&D) purposes, product development, maintenance services such as developing spare parts, and biomedical, automobile, and aerospace components. AM technology is pivotal in helping manufacturing industries achieve their goals of growth, profitability, competitive advantage, and sustainability [9]. The White House report [17] indicated that AM can be used to promote resilience in manufacturing supply chains and to strengthen the manufacturing capability of small and medium-sized firms. In addition, the National Strategy for Advanced Manufacturing [18] states that AM is a form of cutting-edge manufacturing technique that has the potential to stimulate the economy via job creation and promote environmental sustainability by addressing climate change-related issues. It can also strengthen manufacturing supply chains and enhance product development in the health care sector. Supported by this report are the estimates conducted by Research and Markets [19], which projected the global value of the additive manufacturing market to reach $76.16 billion by 2030, since the technology is highly driven by demand and usage from industrial sectors to improve their production efficiency and accelerate the time-to-market of products. For instance, the United States additive manufacturing market size is projected to increase at a compound annual growth rate of 21.3% from 2023 to 2030. This projection is similar to Grand View Research’s estimation which projected that the United States additive manufacturing market will be worth $14.22 billion by 2030.

2.2 Limitations of the AM Technology

Some of the limitations and challenges affecting the use of AM technology for product development and industrial applications include the following: the initial cost is set up, especially for small-scale businesses, slow speed of production, limited expertise and low awareness, insufficient support infrastructure, and the need for post-processing, which may affect the product quality and functional requirements if it is not precisely and carefully carried out, as well as selection of the right materials and AM process that suit a particular manufacturing need [6,9,11–13]. To promote the effective deployment of AM technology, Daniyan et al. [20] proposed an interactive approach that integrates user requirements into a friendly interface. However, because the technology is emerging and disruptive in nature, it will incur some costs to set up initially, and its integration into an existing manufacturing model may require time.

2.3 Industrial Application of AM Technology

AM is a versatile technology that has a broad range of industrial applications. Its flexibility allows seamless integration into an organization’s manufacturing model for improved product quality and production processes. Oyesola et al. [1] stated that AM technology has penetrated three key industries: aerospace, biomedical, and automotive. For instance, the aerospace industry leverages AM to develop lightweight components, including complex geometries and internal structures, such as aircraft rackets, engine and turbine parts, combustion liners, interior fittings, cabin components, fuselage, and cooling channels. This is done to improve the speed, energy efficiency, and environmental sustainability of aircraft. AM technology is also useful in the production of satellite components, such as frames, brackets, and sensor mounts, with significant cost savings and waste reduction via the efficient use of materials. Thus, AM is used for the development of components in military and commercial aircraft, space applications, missile systems, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). A reduction in bulk weight, which is a major consideration in aircraft design, improves aircraft speed, energy efficiency, and environmental sustainability. AM technology can be used to reduce part weights through lattice designs or to achieve part consolidation to reduce the weight of sub-assemblies. In biomedical applications, it is used to manufacture dental models and devices; surgical tools; dentures and dental casting; customized medical insulin for patients with diabetic conditions; lattice cast; customized medical pillows for optimal support of the head, neck, and spine; medical braces to aid the recovery process of people after surgical operations; and scaffolds for bone regeneration [21].

The footwear industry leverages AM technology to improve the flexibility of product design and accelerate product development from prototyping to the production phase. Traditionally, footwear industries rely on injection molding with tooling requirements will significant time and cost implications. The process of product redesign or scaling up or down on the production volume also has time and cost implications in the traditional approach. Conversely, AM technology enables agile manufacturing with modifications in product design and production volume, without the need for tooling. In the automotive industry, the use of AM technology promotes aesthetic and functional prototyping and the acceleration of final product designs. Thus, the automotive industry leverages AM to achieve the just-in-time production of components such as engine manifolds, air conditioning vents, aesthetic bezels, braking components such as brake pads or discs, and gear shift knobs.

Other notable industries, such as the energy industry and consumer goods, also leverage AM technology to rapidly develop products with customized shapes. AM technology is versatile and supports agile manufacturing, freedom of design, time and cost-effectiveness, and customization, amongst other potentials. Thus, the development of an MCD framework will promote its versatility and application in product development.

2.4 Additive Manufacturing Processes

AM process can be classified as shown in Fig. 1 [22].

Figure 1: AM process classification (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [22]. 2021, IOP Publishing)

Fig. 1 shows the classification of AM technologies according to material processing technology, highlighting some of the most commonly used AM technologies.

Generally, these AM technologies offer freedom of design, short production cycle time, just-in-time production, efficient material, and energy use, production of intricate parts, parts customization, rapid prototyping, and consolidation of assemblies into a single part with improved mechanical and microstructural properties and sustainability via cost-effectiveness and production of lightweight parts. Metal-based AM technologies can be classified as shown in Fig. 2 [23].

Figure 2: Metal-based AM technologies (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [23]. 2022, ASME Open Journal of Engineering)

Table 1 highlights the merits and limitations of some common metal-based AM technologies.

2.5 Overview of Decision Framework for AM Technology

Wang et al. [33] proposed a nonsequential decision-making model that allows users to either adapt or produce innovative designs. Li et al. [34] reported a posteriori articulation of preferences similar to that proposed by Wang et al. [33]. This method allows users to select designs from various solutions without clear preferences. In addition, this study proposes an Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)-based decision-making and evaluation framework that can assist in the selection of the right AM candidate based on the user’s design and application needs.

Muvunzi et al. [35] developed an AM evaluation model to select candidate parts in the transport sector. The selection criteria of the evaluation model identified in the model include technical criteria (part complexity, tolerance, finish, etc.), economic criteria (production time and volume, cost of production, etc.), design criteria (weight reduction, part consolidation, etc.), and material criteria (material properties, usage, etc.). Muvunzi et al. [2] also developed a conceptual model for the selection of the appropriate AM manufacturing technology using the rail industry as a case study. The authors identified some important factors, such as industrial needs, part size, materials, shape, and complexity of components, as crucial components of the conceptual model. Some of the criteria identified for the selection of suitable AM techniques include the quality of the final product, service and functional needs, energy consumption, and the cost and time effectiveness of the process [2].

Kumke et al. [36] proposed a novel methodological model that can assist design engineers in product design for AM based on its purpose and application. Liu et al. [37] developed a decision-making model for selecting appropriate AM technology. The model comprises phases such as initial screening, technical evaluation, process selection, re-evaluation, and machine production. Evaluation of the developed model indicates that it can enable design engineers to select the correct AM technology.

Yang et al. [38] proposed a numerical approach for determining the number and exact parts of an assembly that requires a consolidation candidate detection approach. The proposed approach was validated using cases of the throttle pedal and octocopedal considerations. The validation results show that the proposed approach can be used to reduce the number of parts by simplifying the overall product architecture. Daniyan et al. [39] employed computer-aided modeling and a simulation approach to study the behavior of a pump impeller designed as a single solid homogenous part and produced using fused deposition modeling (FDM). The performance evaluation of the impeller model was based on the magnitudes of the stress, strain, and deformation under loading conditions. The findings provide an understanding of the design requirements of the pump impeller using the FDM to improve the design accuracy and reduce the manufacturing cycle time.

From the literature reviewed, it is evident that in recent years, AM technology has gradually progressed beyond mere prototyping towards product development for specific industrial applications. However, the selection of suitable AM technology for use with a decision-support framework is still a missing link [37]. Manufacturing industries that employ AM for product development need the right information that could enhance their knowledge of the strengths and limitations of the various AM processes, as well as a decision support framework as a scientific basis for the selection of AM techniques for product development. Only a few studies have reported the development of a decision support framework that incorporates users’ needs, design, and service requirements, as well as technology capabilities for the selection of AM techniques for aerospace applications. Therefore, this study promotes the scope and application of AM processes for aerospace applications and the development of intricate and durable products while simultaneously streamlining the manufacturing processes. It will also reduce waste and shorten manufacturing cycles, thereby reducing costs and bolstering global business profitability. In essence, this study takes tangible steps toward revolutionizing the landscape of additive manufacturing through the development of an MCD framework for selecting the appropriate AM technique for a specific aerospace application.

This section presents the overall MCD framework for AM technology selection followed by a detailed methodology.

3.1 Development of MCD Framework for Selecting the Right AM Technology for Product Development

The selection process of the appropriate AM technology encompasses the following:

1. Manufacturing goal: The first step in the selection of an appropriate AM technology is to establish a manufacturing goal. The goal is to define the need, resources available, bottom-line objective of profitability, production requirements, customer satisfaction, and manufacturing lead-time, among others.

2. Quality and properties of the final product (such as surface finish, high strength, and excellent corrosion resistance). The selected technology must process a product to its intended quality and properties. To achieve this, process optimization can be carried out to maintain process parameters such as scan speed, printing speed, temperature, and power within the optimum range.

3. Service and functional requirements: Technology must also ensure product integrity. This is the ability of the developed product to perform according to design requirements. Thus, the technology must be able to meet the product’s design requirements. Broad-based experiments, modeling, and simulations (often computer-based) are required to gain insights into the possible technical and functional performance of the product based on the defined design requirements and parameters.

4. Design for manufacturing (DFM): This is an approach to product development that promotes time and cost-effectiveness through design optimization. DFM can assist in the AM process to improve product quality, reduce weight and waste, and minimize part count via part consolidation [40]. It considers some aspects of product development, such as tolerance, standardization, simplicity, process integration, and design optimization.

5. Sustainability: The selected AM technology should also cater to the demand, cost, and effective material usage of the process, and promote environmental friendliness.

6. Availability of experts: Different skills are required for different AM technologies. Thus, the availability of experts with the right technical expertise is necessary when selecting the appropriate AM technology.

7. Materials: Different materials are required for different AM technologies. The cost and availability of materials as well as their compatibility with the selected AM technology are important factors in the selection process.

Fig. 3 presents the framework for the AM technology selection.

Figure 3: Framework for AM technology selection

This study employs a multi-criteria decision (MCD) support approach, specifically the Fuzzy AHP (FAHP), for ranking AM techniques such as the WAAM, L-PBF, BJ, SLS, and LMD, for the production of aircraft components (specifically the fuselage). The selected criteria include the quality and properties of the final product (such as surface finish, high strength, and excellent corrosion resistance), service and functional requirements, weight reduction (lightweight), and sustainability (cost, material usage of the process, environmental friendliness, etc.).

The criteria were selected following a synthesis of the literature, and there exists an interrelationship among them. For instance, the properties and quality of the final product determine whether it meets its service and functional requirements. This also influences the goal of achieving weight reduction. According to Muvunzi et al. [2], the process sustainability of AM technologies, in terms of their cost and time effectiveness, is an important consideration, as this can be affected by the need for post-processing. The need for post-processing is related to the product quality as well as its service and functional requirements because it implies that the product does not meet the intended quality for the initial processing.

This choice of the Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) stems from the fact that it employs the triangular fuzzy elements to represent the pairwise comparison element and also minimize bias and subjectivity compared to the traditional Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) [41]. The FAHP uses fuzzy numbers to minimize uncertainties and subjectivity in the judgment of decision-makers to the allocation of weights. Thus, it is more reliable than the Analytical Hierarchy Process in terms of the reduction in bias and subjectivity [34,42]. The Triangular Fuzzy Numbers (TFN) is a set of three variables, namely l, m, and u, where l represents the lowest possible value, m denotes the most likely value, and u represents the highest possible value.

3.2 The Procedure for the Implementation of FAHP

The TFN has a membership function

STEP 1: Identify the goals and criteria of the FAHP model. The results are shown in Fig. 4. The criteria were formulated based on the literature (Table 1). This study demonstrates the use of MCD support (FAHP) in the selection of a suitable AM technique for the production of aircraft components (e.g., fuselage).

Figure 4: The structure of the FAHP

STEP 2: Use the fuzzy linguistic scale presented in Table 2 to allocate weights and perform pairwise comparisons.

The criteria include the quality and properties of the final product (such as surface finish, high strength, and excellent corrosion resistance), service and functional requirements, weight reduction (lightweight), and sustainability (cost, material usage of the process, environmental friendliness, etc.).

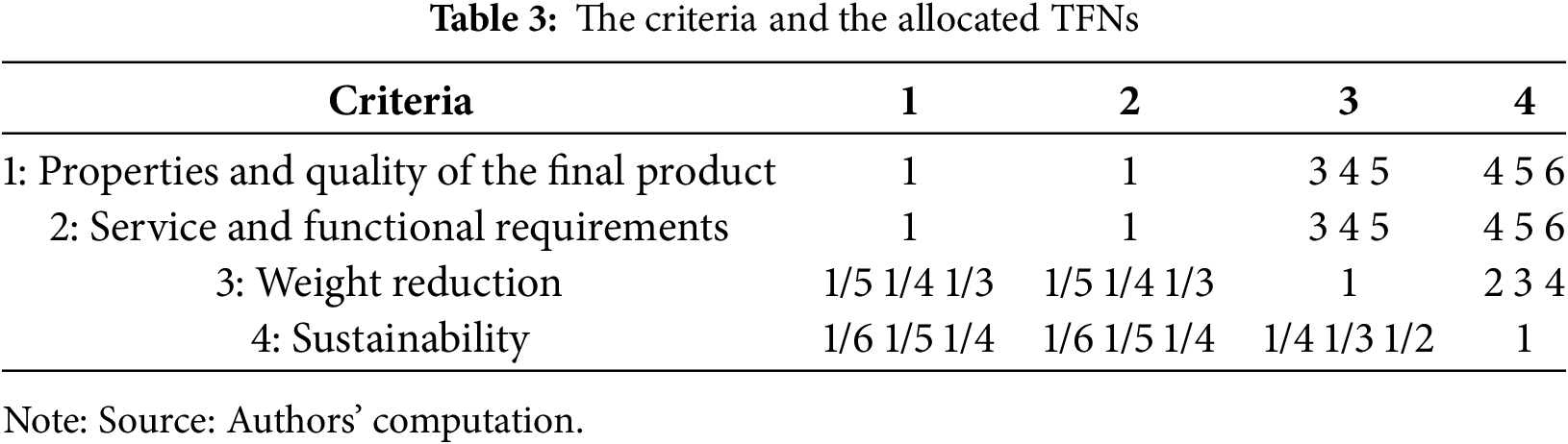

The quality and properties of the final product (criterion 1) are considered to be of equal importance to service and functional requirements (criterion 2), it is allocated a TFN value of (1), and is fairly important to weight reduction (criterion 3), thus allocating a TFN value of (3 4 5), while criterion 3, taken to be marginally less important, takes the reciprocal (1/5 1/4 1/3). Criterion 1 is also considered to be of very strong importance over sustainability (criterion 4); it is allocated a TFN value of (4 5 6), while sustainability considered to be less important takes the reciprocal (1/6 1/5 1/4).

Criterion 2 (service and functional requirements) is also considered to be fairly important for criterion 3 (weight reduction); therefore, it is allocated a TFN value of (3 4 5), while sustainability taken to be marginally less important takes the reciprocal (1/5 1/4 1/3). Criterion 2 is also considered to be of strong importance to criterion 4 (sustainability); it is allocated a TFN value of (4 5 6), while sustainability considered to be less important takes the reciprocal (1/6 1/5 1/4).

Finally, criterion 3 (weight reduction) is considered to be of equal importance to criterion 4 (sustainability); it is allocated a TFN value of (1).

Table 3 presents the criteria and allocated TFNs.

STEP 3: Evaluate the geometric mean (

where

STEP 4: Determine the weight (

STEP 5: Defuzzify the computed weights in Step 2 above according to Eq. (4) [26] to obtain a defuzzified weight (

where

STEP 6: Normalize the defuzzified weights according to Eq. (5) [26] to obtain a normalized weight (

Five alternatives were selected for investigation in this study, representing the various AM technologies by which the fuselage of an aircraft can be developed. These were WAAM, L-PBF, BJ, SLS, and LMD.

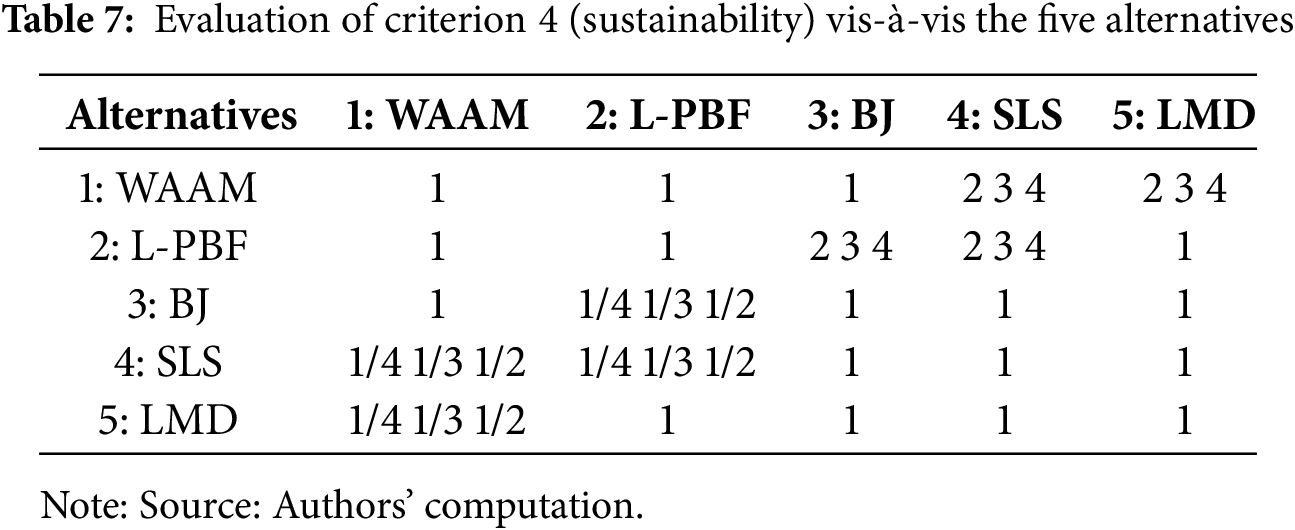

Tables 4–7 present the evaluation of each of the criteria vis-à-vis the alternatives.

Table 4 shows the allocated TFNs for the evaluation of criterion 1 (product properties and quality) concerning the five alternatives.

For criterion 1 (product properties and quality), alternative 1 is considered to be of fair importance to alternatives 2 and 3, equal importance to alternative 4, and of strong importance to alternative 4. On the other hand, alternative 2 is taken to be of equal importance to alternatives 3 and 4 and strong importance to alternative 5 while alternative 3 is taken to be of equal importance to alternative 4 and of a strong importance to alternative 5. Alternative 4 is considered to be of strong importance to alternative 5, as shown in their allocated TFNs and their reciprocals presented in Table 4.

For criterion 2 (service and functional requirements), alternative 1 is considered to be of fair importance to alternatives 2 and 3, equal importance to alternative 4, and of strong importance to alternative 4. Alternative 2 is considered to be of equal importance to alternatives 3 and 4 and fair importance to alternative 5, whereas alternative 3 is considered to be of equal importance to alternative 4 and fair importance to alternative 5. Alternative 4 is considered to be of fair importance to alternative 5, as shown in their allocated TFNs and reciprocals, as presented in Table 5.

For criterion 3 (weight reduction), alternative 1 is considered to be of equal importance to alternatives 2 and 3 and of fair importance to alternatives 4 and 5. On the other hand, alternative 2 is taken to be of equal importance to alternative 3 and a strong importance to alternative 4 and of a fair importance to alternative 5 while alternative 3 is taken to be of fair importance to alternative 4 and of a strong importance to alternative 5. Alternative 4 is considered to be of equal importance to alternative 5, as shown in their allocated TFNs and their reciprocals, as presented in Table 6.

For criterion 3 (weight reduction), alternative 1 is considered to be of equal importance to alternatives 2 and 3 and of fair importance to alternatives 4 and 5. Alternative 2 is considered to be of fair importance to alternatives 3 and 4, whereas alternative 3 is considered to be of equal importance to alternatives 4 and 5. Alternative 4 is considered to be of equal importance to alternative 5, as shown in their allocated TFNs and their reciprocals presented in Table 7.

3.3 Predictive Computational Modelling and Simulations as Precursor to AM Technique Selection

The power of computational modeling and simulations has been explored in this case study to help pre-determine and pre-optimize before manufacturing, the selection, and performance of different materials in their application as structural materials of an aircraft fuselage. This predictive analysis was carried out for the anticipated cascading benefit of reduced fuel consumption and emissions and improved speed and performance of the aircraft based on insights obtained from the analysis and implemented during the additive manufacture of the fuselage. A geometric model of an aircraft fuselage without control (wings and landing gears) and propulsion (turbines) features were produced to scale in the complete Abaqus environment (ABAQUS CAE), as shown in Fig. 5a. The fuselage model assembly was discretized using continuum shell elements into finite linear quadrilateral elements of type S4R and linear hexahedral elements of type SC8R, with a size of 0.02% of the scale obtained from the mesh convergence study (Fig. 5b). Mechanical boundary conditions were imposed on the seams of the fuselage that connect the cockpit at the front to the cabin and the cabin to the bulkhead at the rear. This was performed to constrain the motion of the model to zero translational or rotational motion in all three axes (x, y, z) under consideration in the analysis. A load of magnitude 101.6 KPa corresponding to the pressure to which an aircraft cabin is pressurized at cruising altitude was applied from within the fuselage model to replicate the cabin pressurization in-flight as shown in Fig. 5c. Consequently, a static pressurization analysis was set up to simulate aircraft cabin pressurization at cruising altitude and the structural response of the fuselage to the applied load in terms of the stress and deformation profiles. This was performed for three (3) different types of aircraft fuselage materials, namely aluminum (AA7075 T6), steel (304), and titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V), to arrive at the most suitable material for manufacturing applications and other considerations within the context of additive manufacturing and clean production. These materials are compatible with the five (5) additive manufacturing processes namely WAAM, L-BPF, BJ, SLS, and LMD investigated in this study.

Figure 5: Computational geometric models of an aircraft showing (a) the fuselage (b) the fuselage meshed into finite elements for analysis (c) the internal pressure loading on the aircraft cabin

4.1 Results of the MCD Approach

The results of the eigenvector and geometric mean were similar, as shown in Table 8. This implies a high degree of consistency in the allocation of TFNs and the pairwise comparison process.

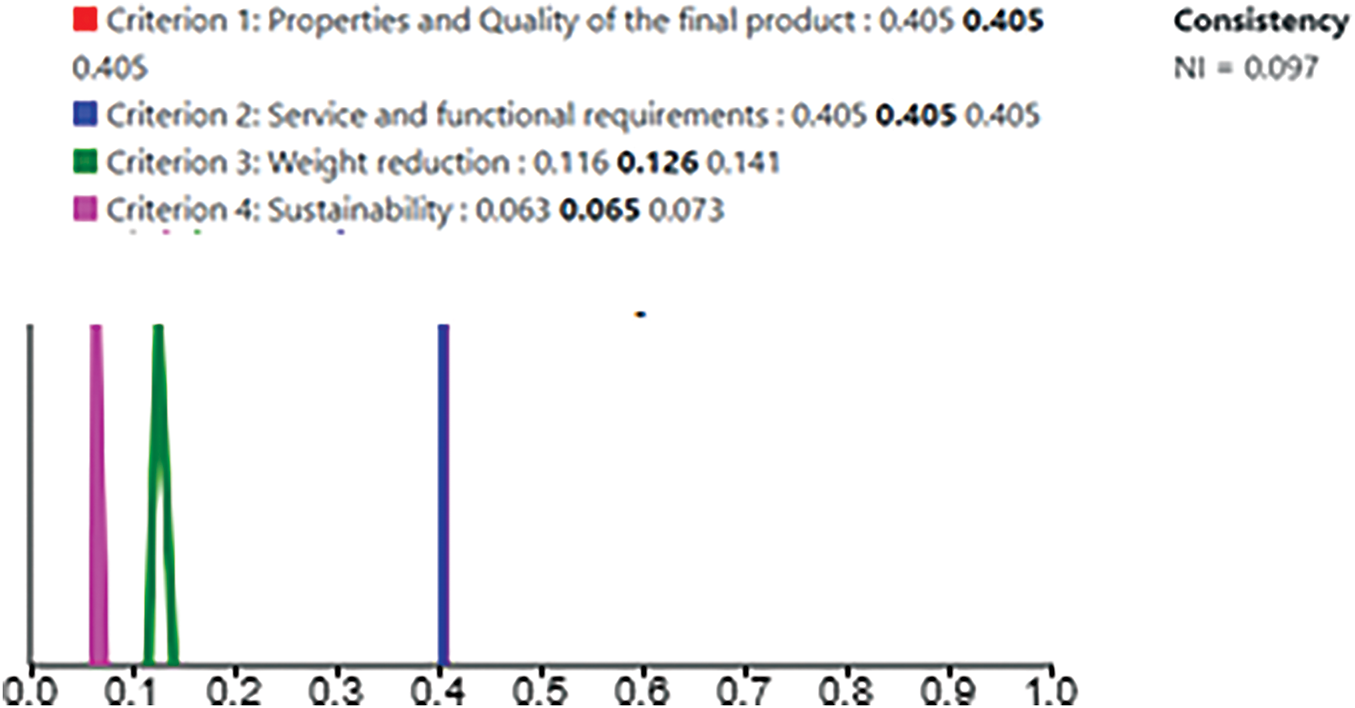

Table 9 displays the maximum eigenvector (

The triangular fuzzy membership of the criteria is illustrated in Fig. 6. The values plotted in Fig. 6 fall within the range of the lowest possible value (l), modal value (m), and highest possible value (u), as there were no outliers. This implies that there is truth and consistency in the fuzzy logic [46]. This further indicates that the proposed method is reliable for multicriteria decision-making.

Figure 6: Triangular fuzzy membership for the criteria. Source: Authors’ computation

Figs. 7–10 present the evaluation of the triangular fuzzy membership for each of the criteria vis-à-vis the alternatives. Similar to the result presented in Fig. 5, there was no outlier as the values in the plot fall within the range of the l, m, and u which indicates a high degree of consistency in the fuzzy logic.

Figure 7: Triangular fuzzy membership of criterion 1 (properties and quality of the final product) vis-à-vis the alternatives. Source: Authors’ computation

Figure 8: Triangular fuzzy membership of criterion 2 (service and functional requirements) vis-à-vis the alternatives. Source: Authors’ computation

Figure 9: Triangular fuzzy membership of criterion 3 (weight reduction) vis-à-vis the alternatives. Source: Authors’ computation

Figure 10: Triangular fuzzy membership of criterion 4 (sustainability) vis-à-vis the alternatives. Source: Authors’ computation

Fig. 11 presents the normalized weights of the criteria vis-à-vis the alternatives. The results show that alternative 1 (WAAM) is the most preferred AM method for the development of fuselages. This is because WAAM as an alternative is favored by the first and second criteria and has the highest normalized weights compared to the other alternatives. This is followed by alternative 2 (L-BPF), which is favored by the third and fourth criteria, whereas alternative 3 (BJ) is favored by the third criterion. Next, in the rank is alternative 4 (SLS), while the least is alternative 5 (LMD) because it has the lowest normalized weights.

Figure 11: Normalised weights of the alternatives vis-à-vis the criteria. Source: Authors’ computation

Table 10 presents the defuzzified and normalized weights of the criteria, while Table 11 presents the defuzzified and normalized weights of the alternatives.

4.2 Results of the Material Simulation Process

The results of the simulation processes provide valuable insights into the magnitude, distribution, stress, and deformations in fuselages using different materials, such as aluminum (AA7075 T6), steel (304), and titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V). It provides indications of regions of possible compromise in its structural integrity with passage of time and multiple cycles of pressurization and depressurization as the aircraft completes each takeoff and landing trip during its lifetime. As shown in Fig. 12, the engineering and environmental advantages of lightweight aluminum (AA7075 T6) fuselage structures produced the least spread in concentration of maximum stresses (300 MPa) experienced by the fuselage, followed by steel alloy (304) with a maximum stress of 400 MPa, whereas titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) has the highest spread of maximum stress concentration of 600 MPa. Studies have indicated that the high strength-to-weight ratio of aluminum makes it suitable for the development of aircraft components such as fuselage [47,48]. Furthermore, from Fig. 13, titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) produced the least deformation due to load with a magnitude of 0.05742 mm, followed by aluminum alloy (AA7075 T6) with a more uniform deformation response profile of 0.07190 mm (maximum) due to applied loading, while steel alloy (304) produced the highest deformation of 0.1078 mm owing to the applied load. Existing studies indicate that titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) has a high strength-to-weight ratio, which makes it resistant to deformation, but its low thermal conductivity may lead to a build of thermal stress, thus contributing to the high stress profile of titanium alloy [49,50].

Figure 12: Variations in stress distribution on the fuselage for same cabin internal pressurization regime but different fuselage structural materials

Figure 13: Variations in deformation profiles of the fuselage in response to the same cabin internal pressurization regime but different fuselage structural materials

These precursory pieces of information, obtained without building real-life replicas and subjecting them to life structural integrity experimentation or testing, accelerate the product development process without incurring high costs associated with physical prototypes, allowing their manufacture and push to market to be fast-tracked. Regions of potential failures have also been predicted before production begins, ensuring higher-quality outputs and reducing rework or scrap rates. This can also guide decisions regarding the additive manufacturing process to be employed during production, thus significantly reducing material waste, development, and production costs.

5 Conclusion and Recommendations

This study evaluates the use of Fuzzy AHP (FAHP) as a multi-criteria decision (MCD) and computer-aided modelling and simulation as decision support tools for selecting appropriate AM techniques. The FAHP model was validated by simulating the fuselage of an aircraft component developed from AM technologies, such as WAAM, L-PBF, BJ, SLS, and LMD. The selection criteria for the FAHP model include the quality and properties of the final product (such as surface finish, high strength, and excellent corrosion resistance ability), service and functional requirements, weight reduction, and sustainability (cost-effectiveness, material conservation, and environmental friendliness). This study highlights the procedural steps of FAHP implementation and presents a framework for AM technology selection. A computer-aided modelling approach was also used to simulate the performance of materials for fuselage development, such as aluminum (AA7075 T6), steel alloy (304), and titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V). The results show that the fuselage structure simulated using lightweight aluminum (AA7075 T6) produced the least spread in maximum stress concentration (300 MPa), followed by steel alloy (304) with a maximum stress of 400 MPa, while titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) had the highest spread of maximum stress concentration of 600 MPa. Furthermore, titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) produced the least deformation due to load with a magnitude of 0.05742 mm, followed by aluminum alloy (AA7075 T6) with a more uniform maximum deformation profile of 0.07190 mm due to the applied load, while steel alloy (304) produced the highest deformation of 0.1078 mm owing to the applied load.

The outcome of the study shows that the FAHP and simulation approach can support the decision-making process related to the selection of the right AM technology for product development and sustainability. Furthermore, the aluminum alloy (AA7075 T6) outperformed the other materials investigated during the simulation with the lowest stress concentration and least deformation. Thus, this study contributes empirically, theoretically, and methodologically to knowledge through the development of MCD and selection frameworks that can assist manufacturers in the selection of the right AM technology for product development. This study explores the FAHP as well as modelling and simulation approaches as decision support tools for AM technology selection. Future studies should consider other MCD approaches and use of artificial intelligence for AM technology selection.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the Bells University of Technology, Ota, Nigeria for creating a conducive and enabling environment that supports this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ilesanmi Afolabi Daniyan, Rumbidzai Muvunzi, Festus Fameso, Julius Ndambuki, Williams Kupolati, Jacques Snyman; analysis and interpretation of results: Ilesanmi Afolabi Daniyan, Rumbidzai Muvunzi, Festus Fameso, Julius Ndambuki, Williams Kupolati, Jacques Snyman; draft manuscript preparation: Ilesanmi Afolabi Daniyan, Rumbidzai Muvunzi, Festus Fameso, Julius Ndambuki, Williams Kupolati, Jacques Snyman. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Ilesanmi Afolabi Daniyan, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Oyesola M, Mathe N, Mpofu K, Fatoba S. Sustainability of additive manufacturing for the South African aerospace industry: a business model for laser technology production, commercialization and market prospects. Procedia CIRP. 2018;72:1530–5. [Google Scholar]

2. Muvunzi R, Khumbulani K, Khodja M, Daniyan IA. A framework for additive manufacturing technology selection: a case for the rail industry. Int J Manuf Mater Mech Eng. 2022;12(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

3. Abdulhameed O, Al-Ahmari A, Ameen W, Mian SH. Additive manufacturing: challenges, trends, and applications. Adv Mech Eng. 2019;11(2):1687814018822880. [Google Scholar]

4. Ford S, Despeisse M. Additive manufacturing and sustainability: an exploratory study of the advantages and challenges. J Clean Prod. 2016;137:1573–87. [Google Scholar]

5. Bogers M, Hadar R, Bilberg A. Additive manufacturing for consumer-centric business models: implications for supply chains in consumer goods manufacturing. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2016;102:225–39. [Google Scholar]

6. Thompson MK, Moroni G, Vaneker T, Fadel G, Campbell RI, Gibson I, et al. Design for additive manufacturing: trends, opportunities, considerations, and constraints. CIRP Annals. 2016;65(2):737–60. doi:10.1016/j.cirp.2016.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Attaran M. Additive manufacturing: the most promising technology to alter the supply chain and logistics. J Serv Sci Manag. 2017;10(3):189–206. doi:10.4236/jssm.2017.103017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Steenhuis HJ, Pretorius L. The additive manufacturing innovation: a range of implications. J Manuf Technol Manag. 2017;28(1):122–43. doi:10.1108/JMTM-06-2016-0081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Javaid M, Haleem A, Singh RP, Suman R, Rab S. Role of additive manufacturing applications towards environmental sustainability. Adv Ind Eng Polym Res. 2021;4(4):312–22. doi:10.1016/j.aiepr.2021.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Karafa M, Schuting M, Kemnitzer J, Westermann HH, Steinhilper R. Comparative lifecycle assessment of conventional and additive manufacturing in mold core making for CFRP production. Procedia Manuf. 2017;8:223–30. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2017.02.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kellens K, Mertens R, Paraskevas D, Dewulf W, Duflou JR. Environmental impact of additive manufacturing processes: does AM contribute to a more sustainable way of part manufacturing? Procedia CIRP. 2017;61:582–7. [Google Scholar]

12. Gao W, Zhang Y, Ramanujan D, Ramani K, Chen Y, Williams CB, et al. The status, challenges, and future of additive manufacturing in engineering. Comput-Aided Des. 2015;69:65–89. [Google Scholar]

13. Elhazmiri B, Naveed N, Anwar MN, Haq MIU. The role of additive manufacturing in Industry 4.0: an exploration of different business models. Sustain Oper Comput. 2022;3:317–29. [Google Scholar]

14. Borille AV, Gomes JDO. Selection of additive manufacturing technologies using decision methods. In: Hoque E, editor. Rapid prototyping tech.–princ. and functional requirements. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2011. p. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

15. Fameso F, Desai D, Kok S, Newby M, Glaser D. Coupled explicit-damping simulation of laser shock peening on x12Cr steam turbine blades. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series; 2021; Bristol, UK:IOP Publishing. Vol. 1780, 012002 p. [Google Scholar]

16. Fameso F, Desai D, Kok S, Armfield D, Newby M. Residual stress enhancement by laser shock treatment in chromium-alloyed steam turbine blades. Materials. 2022;15(16):5682. [Google Scholar]

17. The White House’s “Using additive manufacturing to improve supply chain resilience and bolster small and mid-size firms”[Online]; 2022 [cited 2024 May 23]. Available from: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/cea/written-materials/2022/05/09/using-additive-manufacturing-to-improve-supply-chain-resilience-and-bolster-small-and-mid-size-firms/. [Google Scholar]

18. National strategy for advanced manufacturing. Report by the Subcommittee on Advanced Manufacturing Committee on Technology of the National Science and Technology Council [Online]; 2022 [cited 2024 May 23]. Available from: https://www.manufacturing.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/FINAL%20National%20Strategy%20for%20Advanced%20Manufacturing%2010072022%20Approved%20for%20Release.pdf. [Google Scholar]

19. Research and Markets’s “Additive manufacturing market size, share & trends analysis report by component, by printer type, by technology, by software, by application, by vertical, by material, by region, and segment forecasts, 2022–2030” describing the global additive manufacturing market size [Online]; 2022 [cited 2024 May 23] Available from: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5595864/additive-manufacturing-market-size-share-and. [Google Scholar]

20. Daniyan IA, Balogun V, Mpofu K, Omigbodun FT. An interactive approach towards the development of an additive manufacturing technology for railcar manufacturing. Int J Interact Des Manuf. 2020;14(2):651–66. doi:10.1007/s12008-020-00659-8 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Oladapo BI, Daniyan IA, Ikumapayi OM, Malachi OB, Malachi IO. Microanalysis of hybrid characterization of PLA/cHA polymer scaffolds for bone regeneration. J Polym Testing. 2020;83(13):106341. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Adugna YW, Akessa AD, Lemu HG. Overview study on challenges of additive manufacturing for a healthcare application. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2021; Bristol, UK:IOP Publishing. Vol. 1201, 012041 p. [Google Scholar]

23. Bastin A, Huang X. Progress of additive manufacturing technology and its medical applications. ASME Open J Eng. 2022;1:010802. doi:10.1115/1.4054947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Erazo AL, Apalategi NA, Agote I, Zuza E. Review on recent developments in binder jetting metal additive manufacturing: materials and process characteristics. Powder Metall. 2019;62(5):1–30. [Google Scholar]

25. Paris H, Mokhtarian H, Coatanea E, Museau M, Ituarte IF. Comparative environmental impacts of additive and subtractive manufacturing technologies. CIRP Annals. 2016;65(1):29–32. doi:10.1016/j.cirp.2016.04.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kellens K, Renaldi R, Dewulf W, Kruth JP, Duflou JR. Environmental impact modelling of selective laser sintering processes. Rapid Prototyp J. 2014;20(6):459–70. doi:10.1108/RPJ-02-2013-0018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Luo Y, Ji M, Leu MC, Caudill R. Environmental performance analysis of solid freedom fabrication processes. In: Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment; 1999; New York, NY, USA. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

28. Priarone PC, Lunetto V, Atzeni E, Salmi A. Laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) additive manufacturing: on the correlation between design choices and process sustainability. Procedia CIRP. 2018;78(1–4):85–90. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2018.09.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ghosal P, Majumder MC, Chattopadhyay A. Study on direct laser metal deposition. Mater Today: Proc. 2018;5(5(2)):12509–18. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2018.02.232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Pathak S, Saha GC. Development of sustainable cold spray coatings and 3D additive manufacturing components for repair/manufacturing applications: a critical review. Coatings. 2017;7(8):122. doi:10.3390/coatings7080122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ashokkumar M, Thirumalaikumarasamy D, Sonar T, Deepak S, Vignesh P, Anbarasu M. An overview of cold spray coating in additive manufacturing, component repairing and other engineering applications. J Mech Behav Mater. 2022;31(1):514–34. doi:10.1515/jmbm-2022-0056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Vaz RF, Garfias A, Albaladejo V, Sanchez J, Cano IG. A review of advances in cold spray additive manufacturing. Coatings. 2023;13(2):267. doi:10.3390/coatings13020267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang Y, Blache R, Xu X. Selection of additive manufacturing processes. Rapid Prototyp J. 2017;23(2):434–47. doi:10.1108/RPJ-09-2015-0123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li Y, Shiehand MD, Yang CC. A posterior preference articulation approach to kansei engineering system for product form design. Res Eng Design. 2019;30(1):3–19. doi:10.1007/s00163-018-0297-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Muvunzi R, Mpofu K, Daniyan IA. An evaluation model for selecting part candidates for additive manufacturing in the transport sector. Metals J. 2021;11(765):1–18. doi:10.3390/met11050765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kumke M, Watschke H, Vietor T. A new methodological framework for design for additive manufacturing. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2016;11(1):3–19. doi:10.1080/17452759.2016.1139377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu W, Zhu Z, Ye S. A decision-making methodology integrated in product design for additive manufacturing process selection. Rapid Prototyp J. 2020;26(5):895–909. doi:10.1108/RPJ-06-2019-0174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yang S, Santoro F, Sulthan MA, Zhao YF. A numerical-based part consolidation candidate detection approach with modularization considerations. Res Eng Des. 2019;30(1):63–83. doi:10.1007/s00163-018-0298-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Daniyan IA, Muvunzi R, Fameso F, Ale F. Computer aided modelling and investigation of the performance of a pump impeller produced from fused deposition modelling. In: 2023 IEEE 14th International Conference on Mechanical and Intelligent Manufacturing Technologies, 2023 May 26–28; Cape Town, South Africa. 2023. p. 244–9. [Google Scholar]

40. Ruckstuhl K, Rabello RCC, Davenport S. Design and responsible research innovation in the additive manufacturing industry. Des Stud. 2020;71(3):100966. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2020.100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Akinbowale OE, Mashigo P, Zerihun MF. Evaluating the impact of organisation’s corporate social responsibility from banking industry perspective: a fuzzy analytical hierarchy process approach. Int J Manag Sustain. 2023;12(2):159–76. doi:10.18488/11.v12i2.3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Alyamani R, Long S. The application of fuzzy analytic hierarchy process in sustainable project selection. Sustainability. 2020;12(8314):1–16. doi:10.3390/su12208314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Saaty TL. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int J Serv Sci. 2008;1(1):83–98. doi:10.1504/IJSSCI.2008.017590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Burney SMA, Ali SM. Fuzzy multi-criteria based decision support system for supplier selection in textile industry. Int J Comput Sci Netw Secur. 2019;19(1):239–44. [Google Scholar]

45. Akinbowale OE, Klingelhöfer HE, Zerihun MF. Analytical hierarchy processes and pareto analysis for mitigating cybercrime in the financial sector. J Financ Crime. 2021;28(3):884–1008. [Google Scholar]

46. Hasan MF, Sobhan MA. Describing fuzzy membership function and detecting the outliers by using five number summary of data. Am J Comput Math. 2020;10:410–24. doi:10.4236/ajcm.2020.103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zhu L, Li N, Childs PRN. Light-weighting in aerospace component and system design. Propulsion Power Res. 2018;7(2):103–19. doi:10.1016/j.jppr.2018.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Dursun T, Soutis C. Recent developments in advanced aircraft aluminium alloys. Mater Des. 2014;56:862–71. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2013.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Daniyan IA, Fameso F, Ale F, Bello K, Tlhabadira I. Modelling, simulation and experimental validation of the milling operation of titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V). Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2020;109(7):1853–66. doi:10.1007/s00170-020-05714-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Daniyan IA, Tlhabadira I, Mpofu K, Muvunzi R. Numerical and experimental analysis of surface roughness during the milling operation of titanium alloy Ti6Al4V. Int J Mech Eng Robot Res. 2021;10(12):683–93. doi:10.18178/ijmerr.10.12.683-693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools