Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Barber Optimization Algorithm: A New Human-Based Approach for Solving Optimization Problems

1 Department of Mathematics, Al Zaytoonah University of Jordan, Amman, 11733, Jordan

2 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science and Information Technology, Jadara University, Irbid, 21110, Jordan

3 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, The Hashemite University, P.O. Box 330127, Zarqa, 13133, Jordan

4 Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Vocational Studies, Universitas Negeri Surabaya, Surabaya, 60231, Indonesia

5 Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Shiraz University of Technology, Shiraz, 7155713876, Iran

6 Faculty of Mathematics, Otto-von-Guericke University, P.O. Box 4120, Magdeburg, 39016, Germany

7 Department of Cybersecurity and Cloud computing, Technical Engineering, Uruk University, Baghdad, 10001, Iraq

8 Department of Medical Instrumentations Techniques Engineering, Al-Rasheed University College, Baghdad, 10001, Iraq

9 Department of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, 10001, Iraq

10 Department of Information Electronics, Fukuoka Institute of Technology, Fukuoka, 8110295, Japan

* Corresponding Authors: Mohammad Dehghani. Email: ; Frank Werner. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Bio-Inspired Optimization Algorithms and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(2), 2677-2718. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.064087

Received 04 February 2025; Accepted 17 March 2025; Issue published 16 April 2025

Abstract

In this study, a completely different approach to optimization is introduced through the development of a novel metaheuristic algorithm called the Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA). Inspired by the human interactions between barbers and customers, BaOA captures two key processes: the customer’s selection of a hairstyle and the detailed refinement during the haircut. These processes are translated into a mathematical framework that forms the foundation of BaOA, consisting of two critical phases: exploration, representing the creative selection process, and exploitation, which focuses on refining details for optimization. The performance of BaOA is evaluated using 52 standard benchmark functions, including unimodal, high-dimensional multimodal, fixed-dimensional multimodal, and the Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) 2017 test suite. This comprehensive assessment highlights BaOA’s ability to balance exploration and exploitation effectively, resulting in high-quality solutions. A comparative analysis against twelve widely known metaheuristic algorithms further demonstrates BaOA’s superior performance, as it consistently delivers better results across most benchmark functions. To validate its real-world applicability, BaOA is tested on four engineering design problems, illustrating its capability to address practical challenges with remarkable efficiency. The results confirm BaOA’s versatility and reliability as an optimization tool. This study not only introduces an innovative algorithm but also establishes its effectiveness in solving complex problems, providing a foundation for future research and applications in diverse scientific and engineering domains.Keywords

Optimization is a fundamental concept in mathematics and various applied sciences, representing problems where more than one feasible solution exists. In these cases, the task is to identify the best solution among all available options. An optimization problem is characterized by having at least two feasible solutions, but it may also have an infinite number of feasible solutions. The systematic process of determining an optimal solution is known as optimization [1]. These problems can be formulated mathematically using three critical components: decision variables, constraints, and objective functions. The primary aim of optimization is to find the values of the decision variables that satisfy the constraints while optimizing the objective function [2]. Approaches to solving optimization problems generally fall into two broad categories: deterministic and stochastic methods [3].

Deterministic approaches, further subdivided into gradient-based and non-gradient-based methods, demonstrate efficiency in solving problems that are linear, convex, continuous, and differentiable. However, as optimization problems become increasingly complex, involving nonlinear, nonconvex, discontinuous, and high-dimensional features, deterministic approaches often fail. These methods may become trapped in unsuitable local optima, rendering them ineffective for practical applications [4]. The inherent limitations of deterministic methods, combined with the complexity of many real-world optimization challenges, have necessitated the development of stochastic approaches [5].

Among the stochastic methods, metaheuristic algorithms have gained significant popularity due to their ability to tackle complex optimization problems. These algorithms employ random search techniques within the solution space and utilize random operators to enhance their performance. Metaheuristic algorithms are inspired by various sources, such as nature, physics, human behavior, etc. For example, the Orangutan Optimization Algorithm (OOA) is a nature-inspired metaheuristic that mimics orangutans’ foraging and nesting behaviors, ensuring an efficient exploration and exploitation for engineering optimization problems [6]. The Artificial Satellite Search Algorithm (ASSA) is a physics-based algorithm that mimics satellite motion, utilizing orbit control and quantum computing for an improved exploration and efficiency [7]. Inspired by human behavior, Enterprise Development Optimization (EDO) is a metaheuristic algorithm inspired by enterprise development, integrating tasks, structure, technology, and human interactions with an activity-switching mechanism for solution updates [8]. Other recently published metaheuristic algorithms include Tactical Flight Optimizer (TFO) [9], Paper Publishing Based Optimization (PPBO) [10], and Revolution Optimization Algorithm (ROA) [11].

Metaheuristic algorithms, including improved, hybrid, and integrated variations, have gained significant traction in solving complex real-world problems across a wide range of fields. These algorithms are particularly valuable in optimization tasks, where traditional methods may fail due to the high computational complexity or nonlinearity of the problem [12]. One of the most prominent applications of metaheuristics is in engineering optimization, where they are used to design structures, optimize manufacturing processes, and improve product quality [13]. In the energy sector, metaheuristics have been employed in power generation and distribution systems [14]. Hybrid algorithms that combine features of different metaheuristics, have been used for an optimal placement of distributed generation sources in electrical grids, improving efficiency and reducing operational costs [15]. Transportation and logistics industries also benefit from metaheuristics in vehicle routing, scheduling, and traffic management [16]. Metaheuristic algorithms like ACO, PSO, GA, and SA, when integrated with the adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) in the AnFiS-MoH framework, significantly enhance parameter tuning and improve the accuracy and generalization of models for complex, high-dimensional, nonlinear problems, demonstrating their practical utility [17]. In summary, metaheuristic algorithms, especially their improved and hybrid forms, offer a flexible and powerful approach to solving real-world optimization problems across various industries, demonstrating their practical relevance and adaptability [18].

Metaheuristic algorithms are widely appreciated for their simplicity, ease of implementation, and efficiency in addressing nonlinear, discontinuous, and NP-hard problems. They also perform well in unknown and nonlinear search spaces [19]. The optimization process in metaheuristic algorithms begins by generating a random set of candidate solutions that adhere to the given constraints. Through iterative update mechanisms, these candidate solutions are progressively refined. At the end of the algorithm’s execution, the best candidate is presented as a near-optimal solution to the problem [20]. While metaheuristic algorithms do not guarantee global optima due to their stochastic nature, the solutions they generate are typically close to the global optimal solution, making them suitable for practical applications.

For metaheuristic algorithms to be effective, they must exhibit robust global and local search capabilities. Global search, or exploration, enables the algorithm to identify promising regions within the search space and avoid being trapped in suboptimal solutions. Conversely, local search, or exploitation, allows the algorithm to thoroughly examine promising regions to converge towards the global optimum [21]. The success of metaheuristic algorithms hinges on their ability to balance exploration and exploitation throughout the optimization process [22].

Different metaheuristic algorithms employ varying strategies for exploration and exploitation, leading to diverse performances across the same optimization problem. The quest for more effective solutions has driven researchers to develop numerous metaheuristic algorithms.

A critical research question in the field of metaheuristic algorithms is whether the introduction of new algorithms is still necessary, given the plethora of existing methods. The No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem [23] provides insight into this question by stating that no single algorithm can outperform all others across every optimization problem. Consequently, the effectiveness of a metaheuristic algorithm for one problem does not guarantee its success for another one. This theorem underscores the importance of continued innovation in designing new algorithms to address the unique challenges of diverse optimization problems.

In this context, this paper introduces an innovative metaheuristic algorithm, the Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA), inspired by the dynamic interactions between a barber and their customer. The BaOA draws fundamental inspiration from the processes of selecting and refining a hairstyle during a haircut. This concept is mathematically modeled in two key phases: exploration and exploitation, which simulate the interactions between the barber and the customer.

The BaOA’s effectiveness is evaluated using 52 benchmark functions, including unimodal, high-dimensional multimodal, fixed-dimensional multimodal ones, and the CEC 2017 test suite. Furthermore, its performance is compared against 12 well-established metaheuristic algorithms. Additionally, the BaOA’s capabilities in solving real-world optimization problems are demonstrated through four engineering design case studies.

Accordingly, the key contributions of this research can be described in completely different and more detailed terms as follows:

• The Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA) draws inspiration from the intricate human interactions observed between a barber and a customer, emphasizing their dynamic relationship during the haircut process.

• The fundamental basis of BaOA originates from two key processes: the customer’s selection of a desired hairstyle and the refinement or correction of hairstyle details during the haircut, simulating real-world decision-making and problem-solving behaviors.

• The theoretical structure of BaOA is comprehensively articulated and mathematically formulated to represent two distinct phases: exploration, which mimics the creative selection of solutions, and exploitation, which focuses on refining and improving the selected solutions to achieve optimal results.

• BaOA’s effectiveness is extensively evaluated using a completely diverse set of fifty-two benchmark functions. These include unimodal functions for testing convergence speed, high-dimensional multimodal functions for global search capability, fixed-dimensional multimodal functions for specific challenges, and the comprehensive CEC 2017 test suite for advanced performance analysis.

• The algorithm’s results are rigorously compared against the performance of twelve widely recognized metaheuristic algorithms, showcasing BaOA’s superior ability to solve optimization problems and its competitive edge in achieving better solutions.

• Finally, BaOA’s capability to address real-world challenges is validated by applying it to four distinct engineering design problems, demonstrating its practicality and versatility in solving complex optimization applications across various domains.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review. Section 3 introduces and mathematically models the proposed BaOA approach. Section 4 discusses simulation studies and results. Section 5 evaluates the BaOA’s performance in real-world applications. Finally, Section 6 provides some conclusions and suggestions for future research directions.

Metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as powerful computational tools inspired by a wide array of completely different and intriguing phenomena observed in nature, science, and human behavior. These algorithms draw inspiration from diverse sources, including the complex dynamics of natural phenomena, the organized and collective behavior of animals, the intricate mechanisms of biological processes, the fundamental laws governing physics, strategic principles derived from games, and even the rich spectrum of human interactions and cultural practices. Each source offers unique insights and methodologies for solving challenging optimization problems across various domains.

To better understand their underlying principles, metaheuristic algorithms are categorized into four distinct groups based on the foundational ideas they emulate.

Swarm-based metaheuristic algorithms are completely different from other groups, as they are inspired specifically by swarming phenomena and collective behaviors observed in the natural life of animals, aquatic creatures, insects, reptiles, plants, and various other living organisms. Some of the most prominent and widely used swarm-based metaheuristic algorithms include Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [24], Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) [25], the Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [26], and Firefly Algorithm (FA) [27]. PSO’s fundamental concept is derived from the coordinated swarm movement of birds and fish as they search for food sources. Similarly, ACO is inspired by the remarkable ability of ants to find the shortest communication path between their nest and food sources. In the case of ABC, the foraging activities of honey bee colonies have been the core inspiration, while the optical communication observed among fireflies has influenced the design of FA. The hunting strategies, foraging, and migratory behaviors commonly observed in wildlife have inspired the development of several other swarm-based algorithms, such as the Emperor Penguin Optimizer (EPO) [28], the Reptile Search Algorithm (RSA) [29], Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) [30], the Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA) [31], the White Shark Optimizer (WSO) [32], the African Vultures Optimization Algorithm (AVOA) [33], and the Marine Predators Algorithm (MPA) [34] which further demonstrate the diversity of swarm-based algorithms.

Evolutionary-based metaheuristic algorithms are fundamentally different in their inspiration, as they are based on biological sciences, genetic processes, and the principles of natural selection and survival of the fittest. These algorithms often simulate evolutionary concepts to solve optimization problems. Two of the most notable evolutionary-based algorithms are a Genetic Algorithm (GA) [35] and Differential Evolution (DE) [36]. The design of GA and DE incorporates elements such as reproduction, genetic inheritance, Darwinian evolutionary theory, and stochastic operators like selection, crossover, and mutation. Other examples in this category include Genetic Programming (GP) [37], the Cultural Algorithm (CA) [38], the Artificial Immune System (AIS) [39], the Evolution Strategy (ES) [40], and the Biogeography-based Optimizer (BBO) [41]. These algorithms provide unique frameworks to address optimization challenges by mimicking the complex mechanisms of evolution and natural adaptation.

Physics-based metaheuristic algorithms, as their name suggests, are derived from completely different sources of inspiration—namely, the fundamental laws, phenomena, transformations, and forces in physics. Simulated Annealing (SA), one of the most prominent physics-based algorithms, takes its cue from the process of annealing metals, where a controlled cooling process enables the material to reach a state of minimal energy and maximum structural integrity [42]. Various physical forces have inspired other algorithms, such as the Spring Search Algorithm (SSA) based on tensile force of springs [1], which draws on the tensile force of springs, and the Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) [43] models the gravitational pull as a means of guiding optimization. Furthermore, cosmological concepts play a significant role in algorithms like cosmological concepts are employed in the design of algorithms such as the Galaxy-based Search Algorithm (GbSA) [44], Black Hole (BH) [45], and the Multi-Verse Optimizer (MVO) [46]. Other physics-based algorithms include the Artificial Chemical Reaction Optimization Algorithm (ACROA) [47], the Small World Optimization Algorithm (SWOA) [48], the Ray Optimization (RO) [49] algorithm, and the Magnetic Optimization Algorithm (MOA) [50]. These algorithms reflect the application of physical theories to computational problem-solving.

Human-based metaheuristic algorithms are entirely different in their foundation, as they are inspired by human thoughts, interactions, and social dynamics. Teaching-Learning Based Optimization (TLBO) [51] is perhaps the most well-known example, modeled after the knowledge transfer between teachers and students in an educational setting. The Mother Optimization Algorithm (MOA) is a novel human-based metaheuristic approach that draws inspiration from the nurturing relationship between Eshra’s moher and her children, simulating the phases of education, advice, and upbringing to guide the optimization process [52]. Other examples include Brain Storm Optimization (BSO) [53] and War Strategy Optimization (WSO) [54].

Despite the extensive diversity of inspirations, a completely different approach has yet to be explored: designing a metaheuristic algorithm based on the dynamic interactions between a barber and a customer in a barbershop. Activities such as selecting a hairstyle, making detailed adjustments, and finalizing the haircut represent intelligent and iterative processes with significant potential for computational modeling. This research paper addresses this gap by presenting a novel human-based metaheuristic algorithm inspired by the mathematical modeling of barber-customer interactions, as elaborated in the subsequent section.

3 Barber Optimization Algorithm

In this section, the newly developed Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA) is comprehensively introduced, and its underlying mathematical framework is elaborated in detail.

Hairstyles and haircuts have been an important part of the tradition and culture of societies since ancient times. Photographs, texts, and descriptions indicate that over the centuries, women’s and men’s hair has been seen in various ways, such as curled, styled, arranged, and colored, or even enhanced by the use of wigs [55]. This shows that barbering is a long-standing profession that has a special impact on people’s culture. People are looking for a skilled barber to provide various hairdressing services to customers based on their needs, tastes and preferences. When the customer visits the barbershop, she/he asks the barber to suggest several suitable hairstyles so that he can choose one among them. It is also possible that the customer has already chosen a hairstyle and asks the barber to use that hairstyle for her/him. After the customer chooses a hairstyle, the barber starts her/his work and cuts the hair according to the hairstyle. In the second step, during the haircut, the customer pays attention to the details of the hairstyle and asks the barber to apply corrections to make the hairstyle more attractive. Therefore, the barber must be able to establish a strong relationship with the customer and follow the customer’s instructions to perform the desired hairstyle on the customer’s hair.

The inspiration behind BaOA lies in the intelligent decision-making process involved in hairstyling. The algorithm models the two key stages of hairstyling—initial selection and refinement—as exploration and exploitation phases in the optimization. By formalizing these human-driven selection and refinement processes, BaOA introduces a novel approach that aligns intuitive decision-making with systematic search mechanisms.

Among the human interactions between the barber and the customer, (i) choosing a hairstyle by the customer and (ii) correcting the details of the hairstyle during the haircut are the most prominent intelligent processes. A mathematical modeling of these intelligent behaviors is employed in the BaOA design, which is discussed below. These processes are translated into computational operations to enhance BaOA’s efficiency in solving optimization problems, as elaborated in the following sections.

The proposed BaOA operates as a population-based optimization algorithm, utilizing iterative processes to identify optimal solutions within a problem space. Each BaOA member represents a potential solution, modeled mathematically as a vector. The dimensionality of this vector corresponds to the number of decision variables in the problem, with each element representing a specific variable.

Collectively, the BaOA members form a population represented by a matrix, initialized randomly at the start of the algorithm. This initialization adheres to Eqs. (1) and (2):

where

The objective function values of the problem are evaluated for all BaOA members, forming a vector as shown in Eq. (3):

where

The algorithm identifies the best and worst members based on their respective objective function values. Iteratively, the BaOA population undergoes updates through two distinct phases: exploration and exploitation, which are modeled mathematically based on barber-customer interactions. The initialization process ensures a diverse population, thereby preventing premature convergence and improving the robustness of the search process.

3.3 Phase 1: Choice of Hairstyle by the Customer (Exploration Phase)

Choosing a suitable hairstyle is the most important step for the customer in the barbershop. With the help of the barber, the customer chooses a hairstyle among the hairstyles offered by the barber according to her/his appearance and interests. The hairstyle selection simulation is employed in the design of the first phase of the BaOA update. The choice of a hairstyle by the customer phase, by making major changes in the position of the population members in the search space, leads to an increase in the global search capability and BaOA exploration in escaping from locally optimal solutions and identifying the main optimal area in the search space. This mechanism enhances the diversity of candidate solutions, thereby reducing the likelihood of getting trapped in local optima. The schematic of this phase of BaOA is shown in Fig. 1. This figure shows that the customer first selected the hairstyle he wants. Then the barber, based on this hairstyle, has made widespread changes to the customer hair. These widespread changes to customer’s hair correspond to widespread changes to the position of population members that represent a global search with the aim of enhancing the exploration ability of the BaOA.

Figure 1: Schematic of the exploration phase of BaOA

In order to model this phase, first, the set of hairstyles offered by the barber to the customer for each BaOA member is determined based on the comparison of the objective function values using Eq. (4). In fact, for each member of BaOA, the position of other population members that have a better objective function value than the corresponding member is considered as a hairstyle.

here,

In the BaOA design, it is assumed that the customer chooses a hairstyle randomly among the proposed hairstyles. Then, based on modeling the customer’s haircut according to the chosen hairstyle, a new position for each BaOA member is calculated using Eq. (5). If the value of the objective function is improved at this new position, this new position replaces the previous position of the corresponding coefficient according to Eq. (6).

here,

3.4 Phase 2: Correction of Hairstylist Details While Cutting Hair (Exploitation Phase)

An important factor in the success of a barber is that she/he must be detail-oriented and able to establish close relationships with the customers by having strong communication skills. An excellent and professional barber must be able to follow the customer’s orders, so that she/he can satisfy the customer by correctly executing the customer’s favorite hairstyle. This phase corresponds to the exploitation process in optimization, where local adjustments refine solutions for better accuracy. The schematic of the second phase of BOA is shown in Fig. 2. This figure illustrates that during the haircut, the barber makes small, minor adjustments to the customer’s hair in coordination with the customer. These precise and small changes to the customer’s hair correspond to small changes to the position of the population members, which indicates a local search aimed at enhancing the exploitation ability of the BOA.

Figure 2: Schematic of the exploitation phase of BaOA

The simulation of the correction of hair style details based on the barber’s follow-up of the customer’s instructions is employed in the design of the second phase of the BaOA update. The correction of hairstylist details durint the cutting hair phase by making small changes in the position of the population members in the search space, leads to an increase of the local search capability and the exploitation of BaOA in the accurate scanning of the search space in the promising areas and near the discovered solutions with the aim of achieving better solutions.

In order to model this phase of BaOA, for each population member, the small changes in the position of that member in the search space caused by the simulation of the correction of hairstyle details based on the customer’s orders, have been calculated using Eq. (7). Then, this new position replaces the previous position of the corresponding member if it improves the value of the objective function according to Eq. (8).

here,

By integrating these two phases, BaOA balances exploration and exploitation more effectively than many conventional metaheuristic algorithms. This dual-phase approach enhances convergence speed while maintaining solution diversity, providing a theoretical and practical advantage over existing frameworks.

3.5 Computational Complexity of BaOA

In this subsection, the computational complexity of BaOA is analyzed from a completely different perspective, employing more words and sentences to provide clarity and details. During the initialization phase, BaOA performs several operations such as generating the initial population and setting up necessary parameters, which together contribute to a computational complexity expressed as O(Nm). Here, N denotes the total count of population members involved in the optimization process, while m represents the number of decision variables associated with the problem under consideration.

Furthermore, in the exploration and exploitation phases, the population undergoes iterative updates designed to enhance solution quality and convergence. These updates involve computational tasks proportional to O(2NmT), where T symbolizes the algorithm’s maximum iteration count. Combining these contributions yields an overall computational complexity for BaOA, succinctly represented as O(Nm(1 + 2T)). This revised analysis underscores the interplay of key algorithmic components and their impact on computational demands.

3.6 Repetitions Process, Flowchart, and Pseudocode of BaOA

The execution of the proposed Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA) involves a completely different sequence of steps that are more detailed and elaborate. Initially, the algorithm completes its first iteration by systematically updating all members of the population. This update process, divided into two primary phases, ensures that the solution search is efficient and effective. Once this initial stage is completed, the algorithm transitions into the subsequent iterations. During these iterations, the population members are dynamically updated based on their newly calculated positions. These updates are performed iteratively following the mathematical expressions provided in Eqs. (4)–(8). This iterative cycle continues systematically until the algorithm reaches the final iteration, thereby ensuring a thorough exploration and exploitation of the search space.

With each iteration, the algorithm meticulously evaluates and identifies the best candidate solution. This solution is continuously updated and preserved as the best result discovered up to that point in the execution. By the conclusion of the algorithm’s operation, the most refined and near-optimal candidate solution is presented as the final output, representing the resolution of the problem being addressed.

To provide a clearer understanding of the entire process, the implementation steps of the BaOA are illustrated comprehensively in Fig. 3 using a flowchart. Additionally, the pseudo-code representation in Algorithm 1 complements the flowchart by offering a more detailed, step-by-step procedural view of the algorithm’s execution. These representations ensure that the algorithm’s workings are fully transparent and accessible to readers, providing more words and more sentences to thoroughly describe the methodology.

Figure 3: Flowchart of the proposed BaOA

In this section, the evaluation of the Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA) for tackling various optimization challenges is presented. To comprehensively assess its performance, the proposed BaOA has been tested on an extensive suite of optimization problems. This evaluation includes fifty-two standard benchmark functions categorized into three distinct types: unimodal functions, which assess convergence accuracy, high-dimensional multimodal functions, which evaluate the algorithm’s exploration and exploitation balance, and fixed-dimensional multimodal functions, which measure its ability to escape local optima [56]. Furthermore, the assessment incorporates the CEC 2017 test suite [57], recognized as a challenging benchmark for modern optimization algorithms.

The reasons for choosing the CEC 2017 test suite are as follows:

1. Benchmark Consistency: CEC-2017 provides a well-established and standardized set of benchmark functions that are widely recognized in the optimization community. Using CEC-2017 ensures that comparisons between different algorithms are consistent with past studies, which helps validate the results and maintain the integrity of research over time.

2. Diversity of Problem Types: The CEC-2017 test suite includes a diverse set of problem types, including unimodal, multimodal, fixed-dimensional, and high-dimensional problems. This variety is important for thoroughly evaluating an algorithm’s performance across different problem landscapes, and it has become a reference for testing new algorithms in a comprehensive manner.

3. Comparison with the Existing Literature: Since many studies and algorithms have already been evaluated using the CEC-2017 suite, it allows for a direct comparison with existing results. This is important for demonstrating the relative performance of the new algorithm in relation to established methods.

4. Widely Accepted Validation: The CEC-2017 suite is considered a reliable and robust validation tool for assessing optimization algorithms. It has been used in numerous publications and competitions, making it a trusted resource for benchmarking.

The effectiveness of BaOA is compared against twelve well-established metaheuristic algorithms, namely GA (1988), PSO (1995), GSA (2009), TLBO (2011), GWO (2014), MVO (2016), WOA (2017), MPA (2020), TSA (2020), RSA (2022), AVOA (2021), and WSO (2022). It should be mentioned that in order to provide a fair comparison, in the simulation studies, the original versions of competing algorithms published by their main researchers have been used. Also, regarding GA and PSO, the standard versions published by Professor Seyed Ali Mirjalili have been used. Moreover, a complete information and details about the experimental test suites and their optimal values are available in their respective references introduced in each subsection.

The experimental results are reported using six critical statistical metrics to provide a more detailed and nuanced understanding of the algorithm’s performance. These include the mean, best, and worst values, which demonstrate the overall solution quality, the standard deviation, which indicates solution stability, the median value, which highlights the central tendency, and the rank, which facilitates a comparative analysis. To determine the relative effectiveness of the algorithms on individual benchmark problems, the mean values are employed as the primary ranking index.

4.1 Evaluation of Unimodal Objective Functions

The performance evaluation of the Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA) on unimodal objective functions, specifically F1 through F7, is detailed in Table 1. These functions are designed to test the algorithm’s exploitation capabilities by focusing on the convergence toward the global optimum. According to the results, BaOA has demonstrated a remarkable exploitation strength, achieving the global optimum for the functions F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, and F6. Furthermore, BaOA has emerged as the top-performing optimizer for the F7 function. A deeper analysis reveals that the BaOA, with its exceptional local search and exploitation capabilities, outperforms the competing algorithms when applied to these unimodal functions. Compared to alternative metaheuristics, BaOA’s performance is not only superior but also consistently competitive, highlighting its effectiveness in handling unimodal problems.

4.2 Evaluation of High-Dimensional Multimodal Objective Functions

The optimization outcomes for high-dimensional multimodal functions, ranging from F8 to F13, are presented in Table 2. These functions are particularly challenging as they evaluate the algorithm’s ability to balance exploration and exploitation while avoiding local optima. The simulation results indicate that BaOA successfully converges to the global optimum for F9 and F11, showcasing its strong exploratory capabilities. Additionally, BaOA outperforms all competitor algorithms, claiming the top rank for F8, F10, F12, and F13. The results suggest that BaOA’s global search mechanism excels in traversing complex solution landscapes, making it highly effective for these high-dimensional multimodal problems. Compared to other algorithms, BaOA provides a superior performance, achieving high-quality solutions across all tested functions in this category. Although the performance of some competing algorithms is close to that of BaOA based on the simulation results, an important issue is that functions F8 to F13, by their nature, have a large number of local optima, which challenge the exploration ability of metaheuristic algorithms. Therefore, the greater an algorithm’s ability to converge to better solutions, the higher its capacity to escape from local optima and explore the search space more effectively. To further confirm the superiority of BaOA over the competing algorithms, this issue is also addressed through a statistical analysis in Section 4.4 “Comprehensive Evaluation of the CEC 2017 Benchmark Suite”. In that subsection, it is shown that BaOA has a significant statistical advantage over the competing algorithms.

4.3 Evaluation of Fixed-Dimensional Multimodal Objective Functions

The results of employing BaOA on fixed-dimensional multimodal functions, specifically F14 through F23, are reported in Table 3. These functions challenge the algorithm’s robustness and precision in dealing with problems of fixed dimensionality. BaOA emerges as the best-performing optimizer for the functions F14, F15, F21, F22, and F23. For the functions F16 to F20, the proposed BaOA approach achieves comparable mean index values to some competitor algorithms. However, BaOA demonstrates a superior consistency, as evidenced by its lower standard deviation (std) values, which indicate a stable performance across multiple runs. This consistency reinforces BaOA’s ability to effectively solve fixed-dimensional multimodal functions. Overall, the BaOA achieves competitive results across this function set, yet BaOA delivers more reliable and efficient solutions, affirming its superiority in optimizing fixed-dimensional problems.

To provide further insight into the comparative performance of BaOA and the other algorithms, boxplot diagrams summarizing the optimization outcomes for the functions F1 through F23 are depicted in Fig. 4. These visualizations highlight the robustness and reliability of BaOA in achieving consistent results across diverse benchmark functions, solidifying its status as a leading metaheuristic algorithm.

Figure 4: Boxplots of BaOA and the competitor algorithms performances for F1 to F23

4.4 Comprehensive Evaluation of the CEC 2017 Benchmark Suite

This subsection provides a detailed analysis of the performance of the proposed Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA) in addressing the challenging functions of the CEC 2017 test suite. The CEC 2017 benchmark suite is widely recognized in the optimization community for its rigor and diversity, consisting of thirty benchmark functions categorized into four distinct types: three unimodal functions (C17-F1 to C17-F3), seven multimodal functions (C17-F4 to C17-F10), ten hybrid functions (C17-F11 to C17-F20), and ten composite functions (C17-F21 to C17-F30). These functions are specifically designed to test various aspects of optimization algorithms, including exploitation, exploration, and the ability to navigate complex, high-dimensional landscapes.

It is important to note that the C17-F2 function was excluded from this study due to its unstable behavior during preliminary simulations, which could lead to unreliable results. The performance results of BaOA, along with those of the competing algorithms, are presented in Table 4 for comparison. Additionally, boxplot diagrams summarizing the statistical performance of BaOA and the other algorithms across all test functions are shown in Fig. 5. These diagrams provide a visual representation of BaOA’s stability and consistency.

Figure 5: Boxplots of BaOA and the competitor algorithms performances for the CEC 2017 test suite

The optimization results demonstrate that BaOA achieves first-place rankings in the majority of the benchmark functions, specifically for the functions C17-F1, C17-F3 through C17-F6, C17-F8 through C17-F21, and C17-F23 through C17-F30. This highlights BaOA’s versatility and capability to handle diverse problem types. For unimodal functions, BaOA excels in a precise convergence toward the global optimum, showcasing its strong exploitation ability. For the multimodal functions, BaOA effectively avoids local optima, thanks to its robust exploration mechanisms. When tackling hybrid and composite functions, which combine the characteristics of multiple landscapes, BaOA demonstrates a remarkable adaptability and efficiency in navigating complex solution spaces.

A comprehensive analysis of these results indicates that BaOA outperforms many well-established metaheuristic algorithms in terms of accuracy, convergence speed, and solution quality. This superior performance is evident in its ability to produce better optimization outcomes for most of the benchmark functions compared to its competitors. The findings reinforce BaOA’s potential as a powerful and reliable tool for solving a wide range of real-world and theoretical optimization problems.

4.5 Comprehensive Statistical Evaluation

In this subsection, a completely different approach is taken to statistically analyze the performance of BaOA in comparison with the other metaheuristic algorithms. The primary goal of this statistical evaluation is to determine whether the observed superiority of BaOA over its competitors is statistically significant. To achieve this, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [58], a widely recognized non-parametric statistical method, is employed. This test is particularly suitable for comparing paired data samples and assessing whether there is a significant difference between their central tendencies.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test utilizes a key metric known as the p-value to determine statistical significance. A p-value less than 0.05 indicates that there is a statistically significant difference between the two data samples being compared. This threshold provides a rigorous basis for confirming whether BaOA consistently outperforms the other algorithms or if the observed differences could be attributed to random variations.

It is important to note that the simulation studies were conducted using the MATLAB software. In order to report visually and reader-friendly, the results are reported in a simple manner. The important issue in the results obtained from the statistical analysis is that p-values are less than 0.05. The smaller the p-value, the more significant is the superiority of BaOA over the corresponding competing algorithm.

The detailed results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, which compare BaOA against each competing algorithm, are comprehensively presented in Table 5. The table highlights cases where BaOA achieves a statistically significant advantage, underscoring its reliability and robustness in solving complex optimization problems. Specifically, for benchmark functions where the p-value is less than 0.05, it can be concluded that BaOA demonstrates a superior performance compared to the corresponding metaheuristic algorithm.

By incorporating this rigorous statistical analysis, it becomes evident that BaOA’s enhanced optimization capabilities are not only apparent in the numerical results but also substantiated through a formal statistical validation. This comprehensive evaluation adds more credibility to the effectiveness of BaOA and further solidifies its position as a leading optimization technique in both theoretical and practical applications.

5 Application of BaOA to Real-World Problems

This section provides a completely different and detailed evaluation of the proposed BaOA approach by applying it to real-world engineering design problems. These problems, which represent practical optimization challenges, include the tension/compression spring design, the welded beam design, the speed reducer design, and the pressure vessel design. The results demonstrate how effectively BaOA addresses these challenges and compares its performance with other metaheuristic algorithms.

5.1 Tension/Compression Spring Design

The tension/compression spring design problem is a classic and widely studied engineering optimization task aimed at minimizing the weight of a spring while satisfying specific constraints. This problem is particularly significant due to its practical implications in the design of lightweight and efficient mechanical components. A completely different perspective can be taken by analyzing both the design variables and constraints to achieve optimal results.

The schematic representation of the tension/compression spring design problem is shown in Fig. 6. The problem can be mathematically formulated as follows [59]:

Figure 6: Schematic of the tension/compression spring design

subject to:

with

The BaOA approach, along with the competitor algorithms, was implemented to solve this optimization problem. The numerical results are presented in Tables 6 and 7, showcasing the best found design values and statistical performance. Based on the simulation results, BaOA successfully identified a near-optimal optimal design with the following values for the design variables: (0.0516885, 0.3567142, 11.288853) and the objective function’s minimized value was found to be (0.012665233). These results illustrate that BaOA provides a completely different level of precision and efficiency in optimizing this problem compared to other algorithms.

The convergence behavior of BaOA during the optimization process is depicted in Fig. 7, highlighting its rapid and stable convergence to an optimal solution. A detailed analysis of the simulation results demonstrates that BaOA outperforms the competitor algorithms in achieving superior design variable values and satisfying statistical performance indicators. This finding underscores the algorithm’s ability to handle complex engineering design challenges effectively and with more accuracy.

Figure 7: BaOA’s performance convergence curve for tension/compression spring

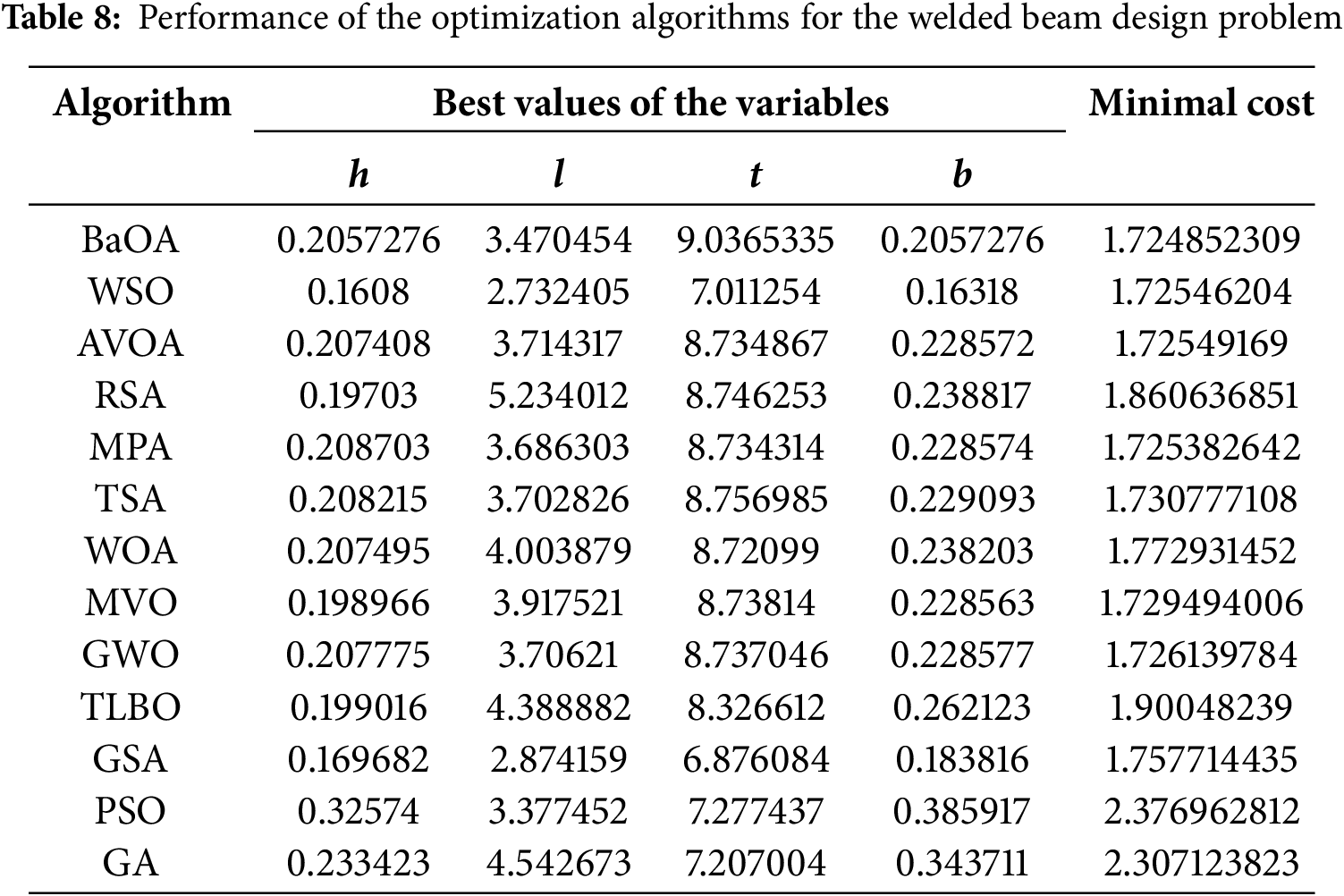

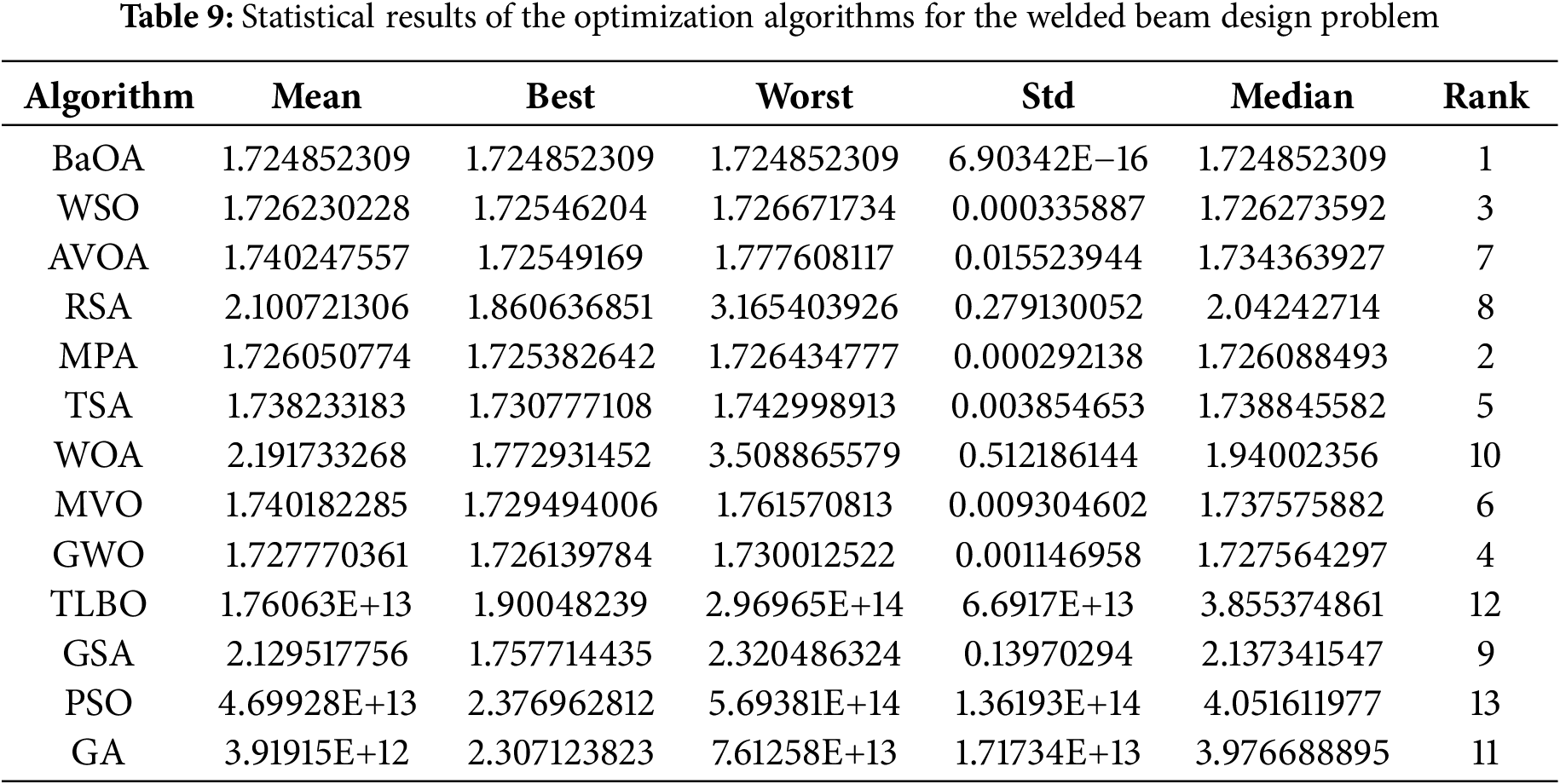

The welded beam design problem is a completely different type of optimization challenge compared to many other engineering design problems. Its primary objective is to minimize the total cost associated with the fabrication of a welded beam while satisfying multiple constraints related to mechanical and structural performance. This problem is crucial in practical engineering applications where cost efficiency and reliability are critical considerations. To address this, a mathematical model of the welded beam design problem has been formulated, which incorporates more words and details about its components and constraints.

The schematic representation of the welded beam design is shown in Fig. 8. The problem involves optimizing four design variables, which are defined as follows [59]:

Figure 8: Schematic of welded beam design

subject to:

where

with

The application of BaOA and the competing algorithms to solve this problem has produced significant results, which are summarized in Tables 8 and 9. BaOA demonstrated a superior performance by identifying the best design variables as: (0.2057276, 3.470454, 9.0365335, 0.2057276) and the corresponding minimized cost function value is: (1.724852309). The convergence curve of BaOA during the optimization process is depicted in Fig. 9. A detailed analysis of the simulation results shows that BaOA achieved completely different and superior outcomes compared to other algorithms. It not only provided the best design variables but also excelled in statistical performance indicators. The results underscore BaOA’s capability to effectively solve welded beam design problems by delivering highly efficient and cost-effective solutions.

Figure 9: BaOA’s performance convergence curve for the welded beam design

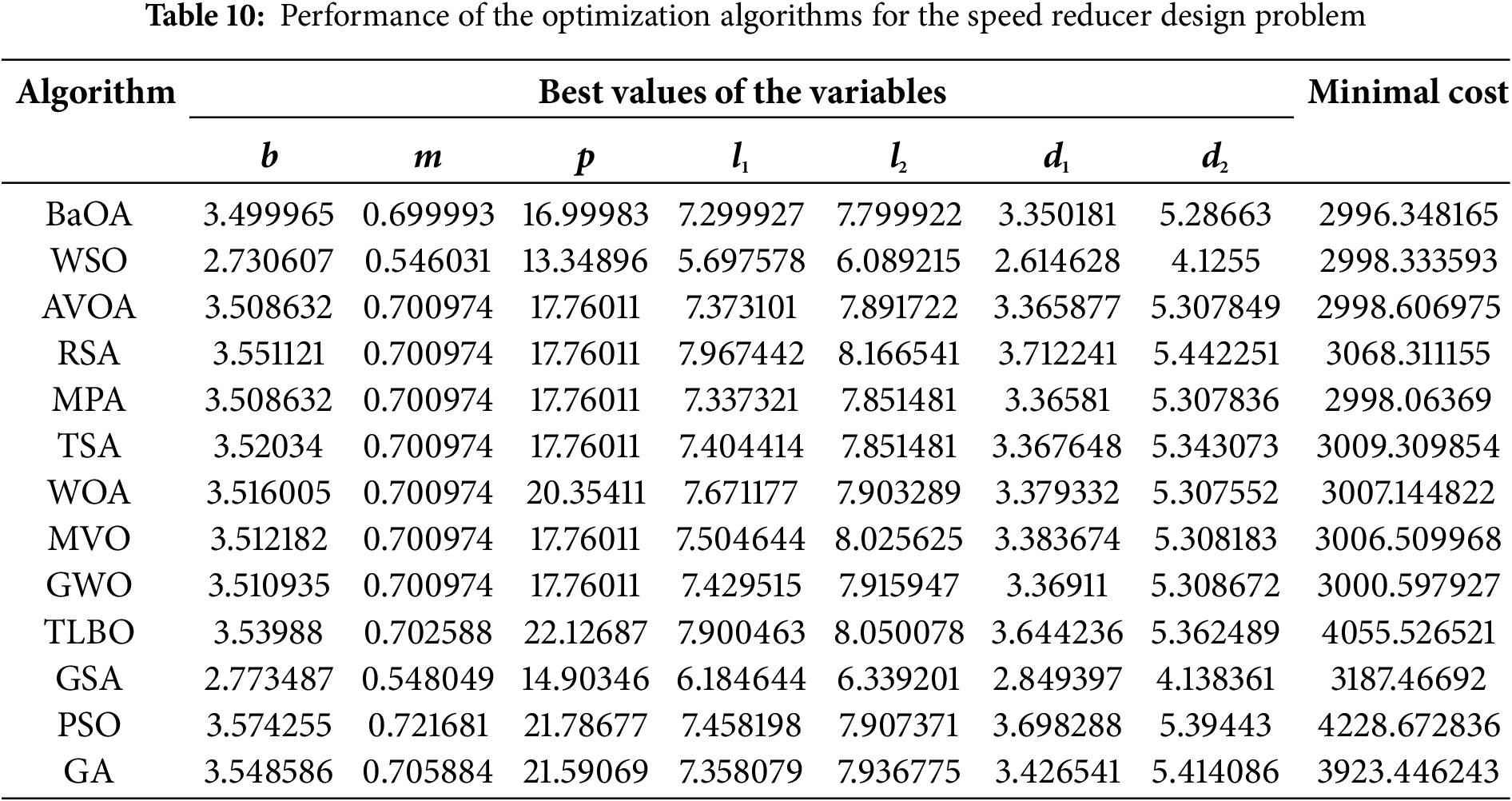

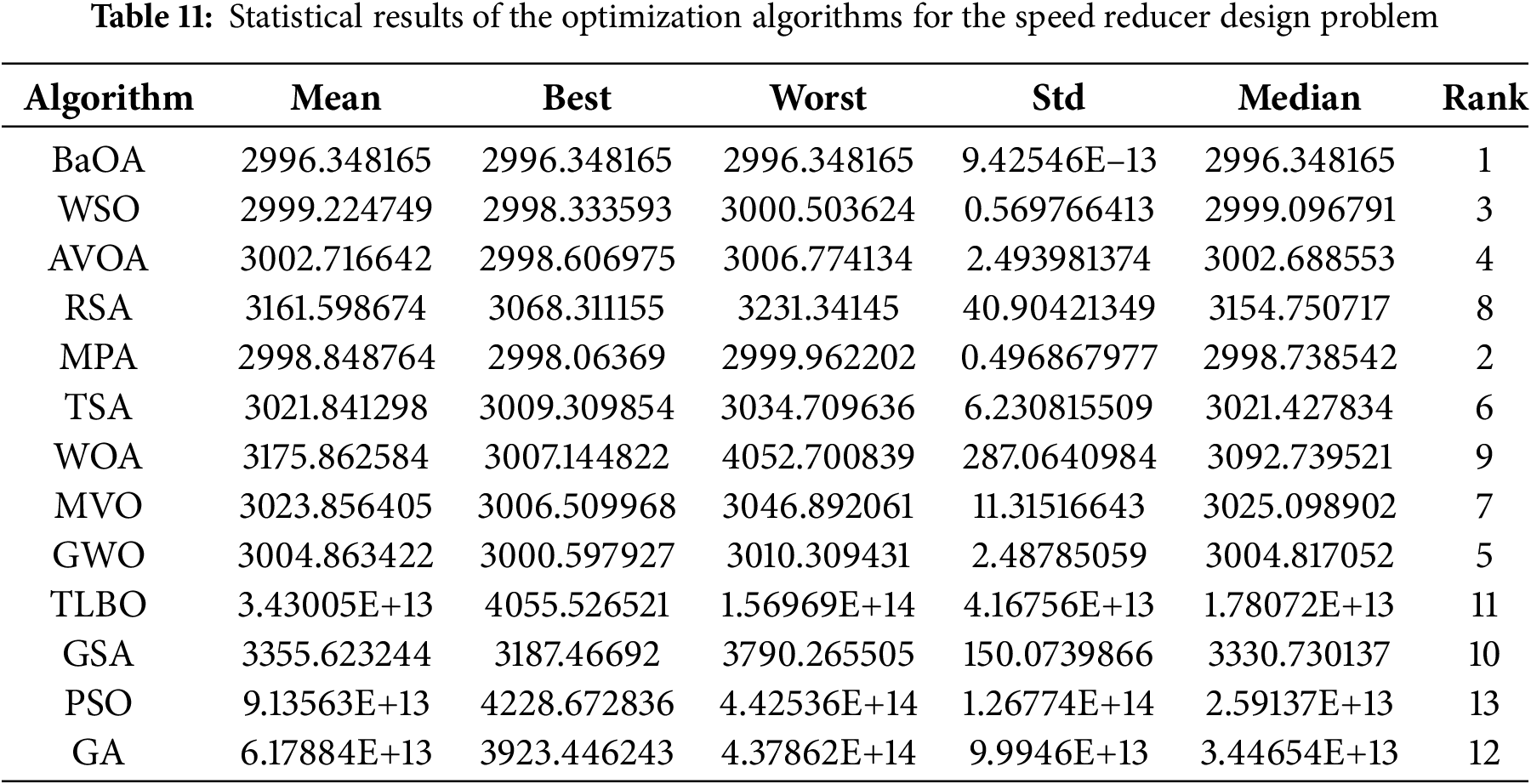

The speed reducer design presents a significant engineering challenge, with the primary objective being the reduction of weight while maintaining or improving performance. This complex task involves a detailed schematic representation, which can be found in Fig. 10, accompanied by the mathematical model that underpins the design process [60,61]:

Figure 10: Schematic of the speed reducer design

subject to:

with

In addressing this challenge, various optimization algorithms have been applied, and their performance compared in terms of how effectively they solve the speed reducer design problem. The results are presented in Tables 10 and 11. One such algorithm, namely BaOA, has shown promising results in the simulation studies, offering the best design solutions. This is evident from the values of the design variables—(3.499965, 0.699993, 16.99983, 7.299927, 7.799922, 3.350181, 5.28663)—and the corresponding objective function value of 2996.348165. Moreover, the convergence curve for BaOA, shown in Fig. 11, illustrates how the algorithm efficiently converges to the optimal solution for the speed reducer design.

Figure 11: BaOA’s performance convergence curve for the speed reducer design

A deeper analysis of these simulation results reveals that BaOA consistently outperforms the competing algorithms in terms of achieving better values for the design variables, as well as superior statistical performance indicators. These findings suggest that BaOA not only provides a more efficient solution but also offers a more reliable approach when compared to other optimization methods applied to the speed reducer design problem. Therefore, this research underscores the effectiveness of BaOA in tackling the complexities associated with speed reducer design optimization.

The pressure vessel design is a crucial engineering challenge, especially in practical applications, where the primary objective is to minimize the overall cost of the design while ensuring safety, durability, and efficiency. The complexity of this task is demonstrated by the pressure vessel design schematic, which is shown in Fig. 12, alongside its associated mathematical model, as detailed in [62]:

Figure 12: Schematic of the pressure vessel design

subject to:

with

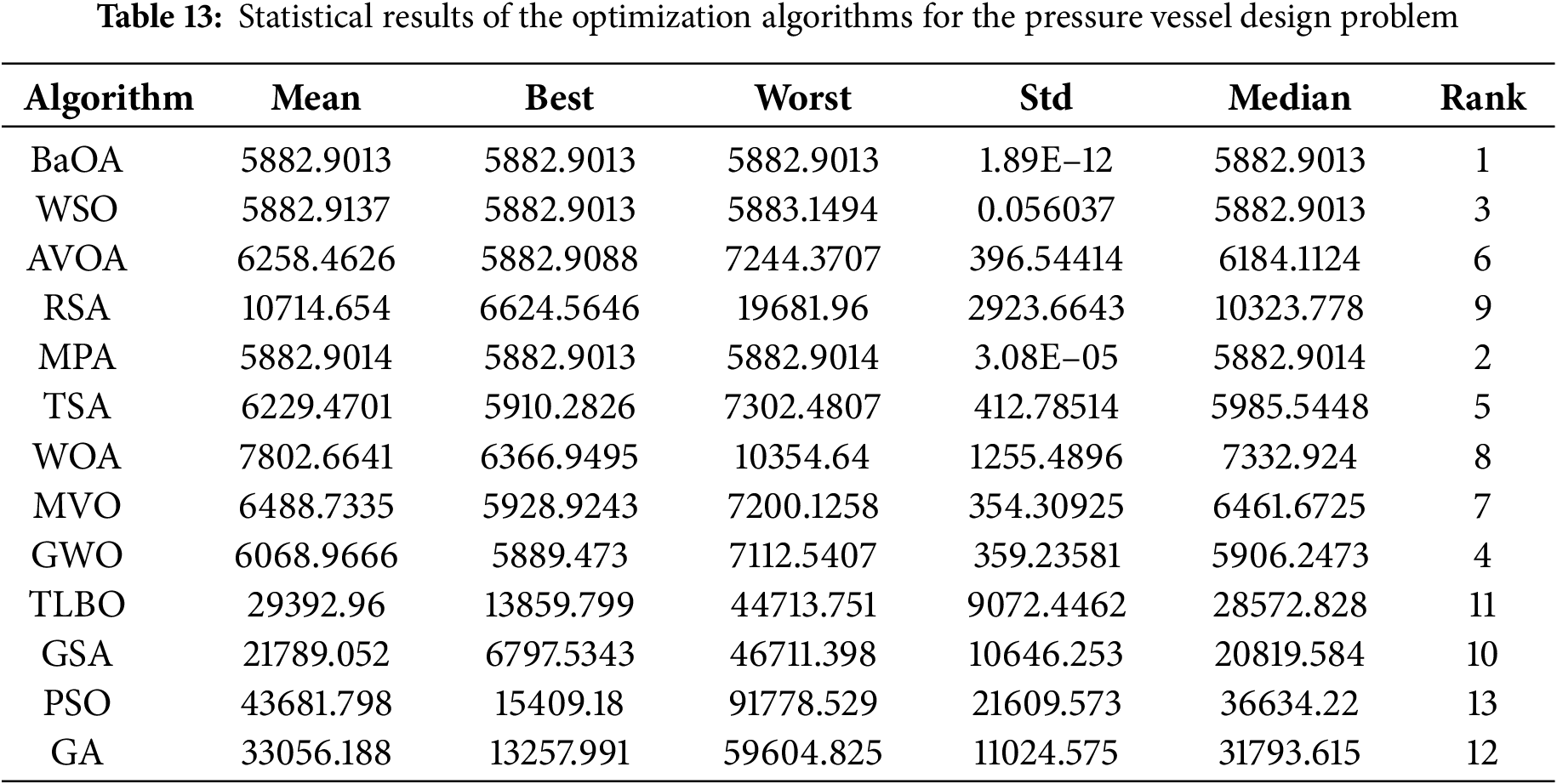

To solve this complex problem, various optimization algorithms are employed. One of the most effective algorithms in this context is the BaOA, which has shown promising results in comparison to other algorithms. The optimization results using BaOA and the other competing algorithms are presented in Tables 12 and 13, providing a comprehensive comparison of the performance of each method.

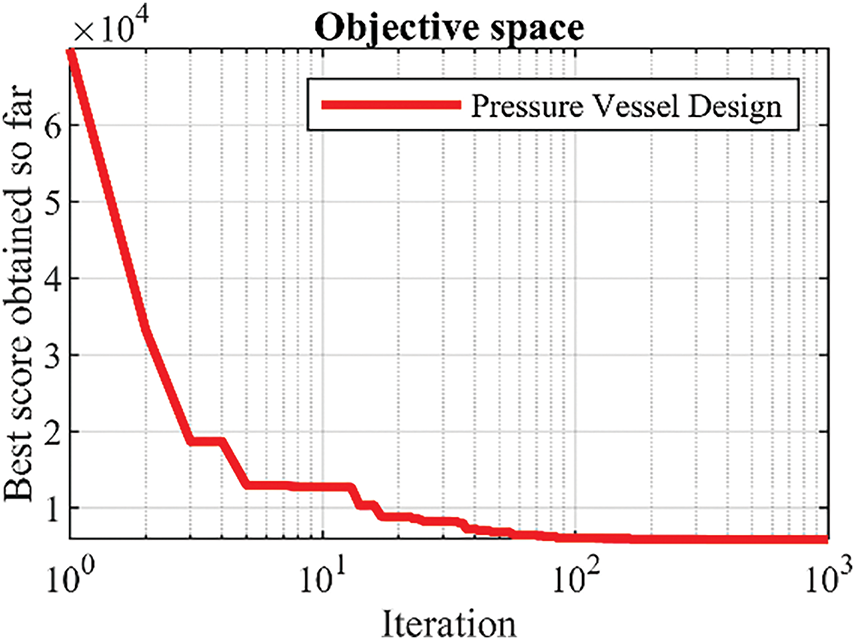

The simulation results indicate that BaOA delivers the best design with the values of the design variables being (0.778019, 0.384575, 40.31188, 199.998) and the objective function value equal to 5882.9013. The convergence curve for BaOA, shown in Fig. 13, illustrates how the algorithm efficiently approaches the optimal solution for the design variables. This demonstrates BaOA’s superior performance in solving the pressure vessel design problem.

Figure 13: BaOA’s performance convergence curve for the pressure vessel design

Upon analyzing the results, it is clear that BaOA outperforms the competing algorithms, not only providing better design values but also offering superior statistical performance indicators. This makes BaOA a more effective and reliable tool for addressing pressure vessel design challenges in engineering applications.

In this paper, we presented a novel metaheuristic algorithm inspired by human behavior, called the Barber Optimization Algorithm (BaOA). This new approach is designed to solve complex optimization problems across various scientific disciplines. The core inspiration behind BaOA stems from the human interactions between a barber and a customer, which include two key processes: (1) the customer’s selection of a hairstyle and (2) the refinement or correction of the hairstyle during the haircut. These human elements form the basis for the two-phase process of BaOA: the exploration phase, modeled on the selection of a hairstyle, and the exploitation phase, which simulates the correction of hairstyle details. Both phases are mathematically modeled to guide the optimization process effectively.

The performance of BaOA in solving optimization problems was rigorously tested on a diverse set of fifty-two benchmark functions. These functions include unimodal, high-dimensional multimodal, fixed-dimensional multimodal ones, and those from the CEC 2017 test suite. The results from these tests demonstrate BaOA’s strong capability to balance exploration and exploitation, allowing it to find optimal or near-optimal solutions with high efficiency. In comparison with twelve well-established metaheuristic algorithms, BaOA consistently delivered a superior performance, providing better solutions for the majority of the benchmark functions. This highlights BaOA’s competitive edge in solving complex optimization problems.

Furthermore, BaOA was applied to four engineering design problems, where it showcased its potential for real-world applications, solving practical design challenges with remarkable accuracy. The study concludes by suggesting several avenues for future research, including the development of binary and multi-objective versions of BaOA. Additionally, the application of BaOA to further optimization problems in a wide range of scientific and engineering fields presents exciting opportunities for future exploration.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Tareq Hamadneh, Belal Batiha, Omar Alsayyed, Ibraheem Kasim Ibraheem, Kei Eguchi, Mohammad Dehghani; data collection: Belal Batiha, Widi Aribowo, Riyadh Kareem Jawad, Kei Eguci, Zeinab Montazeri, Frank Werner, Ibraheem Kasim Ibraheem, Haider Ali, Tareq Hamadneh; analysis and interpretation of results: Omar Alsayyed, Kei Eguci, Widi Aribowo, Frank Werner, Haider Ali, Riyadh Kareem Jawad, Mohammad Dehghani, Tareq Hamadneh; draft manuscript preparation: Tareq Hamadneh, Zeinab Montazeri, Frank Werner, Haider Ali, Widi Aribowo, Riyadh Kareem Jawad, Omar Alsayyed, Belal Batiha, Ibraheem Kasim Ibraheem, Mohammad Dehghani. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dehghani M, Montazeri Z, Dhiman G, Malik O, Morales-Menendez R, Ramirez-Mendoza RA, et al. A spring search algorithm applied to engineering optimization problems. Appl Sci. 2020;10(18):6173. doi:10.3390/app10186173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Dehghani M, Montazeri Z, Dehghani A, Samet H, Sotelo C, Sotelo D, et al. DM: dehghani method for modifying optimization algorithms. Appl Sci. 2020;10(21):7683. doi:10.3390/app10217683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Coufal P, Hubálovský Š, Hubálovská M, Balogh Z. Snow leopard optimization algorithm: a new nature-based optimization algorithm for solving optimization problems. Mathematics. 2021;9(21):2832. doi:10.3390/math9212832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kvasov DE, Mukhametzhanov MS. Metaheuristic vs. deterministic global optimization algorithms: the univariate case. Appl Math Comput. 2018;318(9):245–59. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2017.05.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mirjalili S. The ant lion optimizer. Adv Eng Softw. 2015;83:80–98. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2015.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hamadneh T, Batiha B, Gharib GM, Montazeri Z, Werner F, Dhiman G, et al. Orangutan optimization algorithm: an innovative bio-inspired metaheuristic approach for solving engineering optimization problems. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2025;18(1):47–57. doi:10.22266/ijies2025.0229.05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cheng MY, Sholeh MN. Artificial satellite search: a new metaheuristic algorithm for optimizing truss structure design and project scheduling. Appl Math Model. 2025;143(3):116008. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2025.116008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Truong DN, Chou JS. Metaheuristic algorithm inspired by enterprise development for global optimization and structural engineering problems with frequency constraints. Eng Struct. 2024;318:118679. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.118679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mortazavi A, Moloodpoor M. Tactical flight optimizer: a novel optimization technique tested on mathematical, mechanical, and structural optimization problems. Mater Test. 2025;67(2):330–52. doi:10.1515/mt-2024-0327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hamadneh T, Batiha B, Gharib GM, Montazeri Z, Dehghani M, Aribowo W, et al. Paper publishing based optimization: a new human-based metaheuristic approach for solving optimization tasks. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2025;18(2):504–19. doi:10.22266/ijies2025.0331.37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hamadneh T, Batiha B, Gharib GM, Montazeri Z, Dehghani M, Aribowo W, et al. Revolution optimization algorithm: a new human-based metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2025;18(2):520–31. doi:10.22266/ijies2025.0331.38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Y, Xiong G. Metaheuristic optimization algorithms for multi-area economic dispatch of power systems: part II—a comparative study. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(5):132. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11125-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Akçay Ö, İlkılıç C. Light-weight design of aerospace components using genetic algorithm and dandelion optimization algorithm. Int J Aeronaut Space Sci. 2025;26(2):1–12. doi:10.1007/s42405-025-00900-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nassar SM, Saleh A, Eisa AA, Abdallah E, Nassar IA. Optimal allocation of renewable energy resources in distribution systems using meta-heuristic algorithms. Results Eng. 2025;25(2):104276. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Daravath R, Bali SK. Optimal distributed energy resources placement to reduce power losses and voltage deviation in a distribution system. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Electr Eng. 2025;49(1):1–12. doi:10.1007/s40998-024-00780-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chau ML, Gkiotsalitis K. A systematic literature review on the use of metaheuristics for the optimisation of multimodal transportation. Evol Intell. 2025;18(2):1–37. doi:10.1007/s12065-025-01020-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang H, Chen B, Sun H, Li A, Zhou C. AnFiS-MoH: systematic exploration of hybrid ANFIS frameworks via metaheuristic optimization hybridization with evolutionary and swarm-based algorithms. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;167(2):112334. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jaber I, Hassouneh Y, Khemaja M. A hybrid meta-heuristic algorithm for optimization of capuchin search algorithm for high-dimensional biological data classification. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(7):5719–50. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10815-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dokeroglu T, Sevinc E, Kucukyilmaz T, Cosar A. A survey on new generation metaheuristic algorithms. Comput Ind Eng. 2019;137(5):106040. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2019.106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dehghani M, Montazeri Z, Dehghani A, Malik OP, Morales-Menendez R, Dhiman G, et al. Binary spring search algorithm for solving various optimization problems. Appl Sci. 2021;11(3):1286. doi:10.3390/app11031286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hussain K, Mohd Salleh MN, Cheng S, Shi Y. Metaheuristic research: a comprehensive survey. Artif Intell Rev. 2019;52(4):2191–233. doi:10.1007/s10462-017-9605-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Iba K. Reactive power optimization by genetic algorithm. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 1994;9(2):685–92. doi:10.1109/59.317674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wolpert DH, Macready WG. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 1997;1(1):67–82. doi:10.1109/4235.585893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kennedy J, Eberhart R. Particle swarm optimization. In: Proceedings of ICNN’95—International Conference on Neural Networks; 1995 Nov 27–Dec 1; Perth, WA, Australia. doi:10.1109/ICNN.1995.488968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dorigo M, Maniezzo V, Colorni A. Ant system: optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Part B. 1996;26(1):29–41. doi:10.1109/3477.484436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Karaboga D, Basturk B. Artificial bee colony (ABC) optimization algorithm for solving constrained optimization problems. In: Foundations of fuzzy logic and soft computing; Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2007. p. 789–98. [Google Scholar]

27. Yang XS, editor. Firefly algorithms for multimodal optimization. In: International Symposium on Stochastic Algorithms; 2009 Oct 26–28; Sapporo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

28. Dhiman G, Kumar V. Emperor penguin optimizer: a bio-inspired algorithm for engineering problems. Knowl -Based Syst. 2018;159(2):20–50. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2018.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Abualigah L, Abd Elaziz M, Sumari P, Geem ZW, Gandomi AH. Reptile Search Algorithm (RSAa nature-inspired meta-heuristic optimizer. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;191(11):116158. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.116158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Mirjalili S, Mirjalili SM, Lewis A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv Eng Softw. 2014;69:46–61. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2013.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kaur S, Awasthi LK, Sangal AL, Dhiman G. Tunicate Swarm Algorithm: a new bio-inspired based metaheuristic paradigm for global optimization. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2020;90(2):103541. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Braik M, Hammouri A, Atwan J, Al-Betar MA, Awadallah MA. White Shark Optimizer: a novel bio-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Knowl-Based Syst. 2022;243(7):108457. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Abdollahzadeh B, Gharehchopogh FS, Mirjalili S. African vultures optimization algorithm: a new nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Comput Ind Eng. 2021;158(4):107408. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2021.107408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Faramarzi A, Heidarinejad M, Mirjalili S, Gandomi AH. Marine predators algorithm: a nature-inspired metaheuristic. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;152:113377. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Goldberg DE, Holland JH. Genetic algorithms and machine learning. Mach Learn. 1988;3(2):95–9. doi:10.1023/A:1022602019183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Storn R, Price K. Differential evolution—a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J Glob Optim. 1997;11(4):341–59. doi:10.1023/A:1008202821328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Banzhaf W, Nordin P, Keller RE, Francone FD. Genetic programming: an introduction: on the automatic evolution of computer programs and its applications. San Francisco, CA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

38. Reynolds RG. An introduction to cultural algorithms. In: Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference on Evolutionary Programming; 1994 Feb 24–26; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

39. De Castro LN, Timmis JI. Artificial immune systems as a novel soft computing paradigm. Soft Comput. 2003;7(8):526–44. doi:10.1007/s00500-002-0237-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Beyer HG, Schwefel HP. Evolution strategies—a comprehensive introduction. Nat Comput. 2002;1(1):3–52. doi:10.1023/A:1015059928466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Simon D. Biogeography-based optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2008;12(6):702–13. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2008.919004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kirkpatrick S, Gelatt CD, Vecchi MP. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science. 1983;220(4598):671–80. doi:10.1126/science.220.4598.671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Rashedi E, Nezamabadi-Pour H, Saryazdi S. GSA: a gravitational search algorithm. Inf Sci. 2009;179(13):2232–48. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2009.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Shah-Hosseini H. Principal components analysis by the galaxy-based search algorithm: a novel metaheuristic for continuous optimisation. Int J Comput Sci Eng. 2011;6(1–2):132–40. doi:10.1504/IJCSE.2011.041221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Hatamlou A. Black hole: a new heuristic optimization approach for data clustering. Inf Sci. 2013;222:175–84. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2012.08.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Mirjalili S, Mirjalili SM, Hatamlou A. Multi-verse optimizer: a nature-inspired algorithm for global optimization. Neural Comput Appl. 2016;27(2):495–513. doi:10.1007/s00521-015-1870-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Alatas B. ACROA: artificial chemical reaction optimization algorithm for global optimization. Expert Syst Appl. 2011;38(10):13170–80. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2011.04.126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Du H, Wu X, Zhuang J. Small-world optimization algorithm for function optimization. In: Advances in Natural Computation: Second International Conference, ICNC 2006; 2006 Sep 24–28; Xi’an, China. [Google Scholar]

49. Kaveh A, Khayatazad M. A new meta-heuristic method: ray Optimization. Comput Struct. 2012;112-113:283–94. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2012.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Tayarani NMH, Akbarzadeh TMR. Magnetic optimization algorithms a new synthesis. In: 2008 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence); 2008 Jun 1–6; Hong Kong, China. doi:10.1109/CEC.2008.4631155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Rao RV, Savsani VJ, Vakharia D. Teaching-learning-based optimization: a novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput-Aided Des. 2011;43(3):303–15. doi:10.1016/j.cad.2010.12.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Matoušová I, Trojovský P, Dehghani M, Trojovská E, Kostra J. Mother optimization algorithm: a new human-based metaheuristic approach for solving engineering optimization. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):10312. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-37537-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Shi Y. Brain storm optimization algorithm. In: Advances in Swarm Intelligence: Second International Conference, ICSI 2011; 2011 Jun 12–15; Chongqing, China. [Google Scholar]

54. Ayyarao TL, RamaKrishna N, Elavarasam RM, Polumahanthi N, Rambabu M, Saini G, et al. War strategy optimization algorithm: a new effective metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization. IEEE Access. 2022;10(4):25073–105. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3153493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Lawson HM. Working on hair. Qual Sociol. 1999;22(3):235–57. doi:10.1023/A:1022957805531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Yao X, Liu Y, Lin G. Evolutionary programming made faster. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 1999;3(2):82–102. doi:10.1109/4235.771163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Awad N, Ali M, Liang J, Qu B, Suganthan P, Definitions P. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for the CEC, 2017 special session and competition on single objective real-parameter numerical optimization. Technol Rep. 2016;1:8. [Google Scholar]

58. Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. In: Kotz S, Johnson N, editors. Breakthroughs in statistics. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1992. p. 196–202. [Google Scholar]

59. Mirjalili S, Lewis A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv Eng Softw. 2016;95(12):51–67. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Gandomi AH, Yang XS. Benchmark problems in structural optimization. In: Computational optimization, methods and algorithms. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. p. 259–81. [Google Scholar]

61. Mezura-Montes E, Coello CAC. Useful infeasible solutions in engineering optimization with evolutionary algorithms. In: Mexican International Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2005 Nov 14–18; Monterret, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

62. Kannan B, Kramer SN. An augmented Lagrange multiplier based method for mixed integer discrete continuous optimization and its applications to mechanical design. J Mech Des. 1994;116(2):405–11. doi:10.1115/1.2919393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools