Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Learning Approaches for Battery Capacity and State of Charge Estimation with the NASA B0005 Dataset

1 School of Computer Science, Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia

2 School of Data Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Bhopal, 462066, India

3 Research Institute of Marine Systems Engineering, Seoul National University, Seoul, 08826, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Delhi NCR Campus, Ghaziabad, 201204, India

5 Battery System Modelling Department, CLARIOS VARTA Hannover GmbH, Hanover, 30419, Germany

6 Science and Innovation Group, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane, 4000, Australia

* Corresponding Authors: Zeyang Zhou. Email: ; Mukesh Prasad. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4795-4813. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.060291

Received 29 October 2024; Accepted 07 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

Accurate capacity and State of Charge (SOC) estimation are crucial for ensuring the safety and longevity of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. This study examines ten machine learning architectures, Including Deep Belief Network (DBN), Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Network (BiDirRNN), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and others using the NASA B0005 dataset of 591,458 instances. Results indicate that DBN excels in capacity estimation, achieving orders-of-magnitude lower error values and explaining over 99.97% of the predicted variable’s variance. When computational efficiency is paramount, the Deep Neural Network (DNN) offers a strong alternative, delivering near-competitive accuracy with significantly reduced prediction times. The GRU achieves the best overall performance for SOC estimation, attaining an of 0.9999, while the BiDirRNN provides a marginally lower error at a slightly higher computational speed. In contrast, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFN) exhibit relatively high error rates, making them less viable for real-world battery management. Analyses of error distributions reveal that the top-performing models cluster most predictions within tight bounds, limiting the risk of overcharging or deep discharging. These findings highlight the trade-off between accuracy and computational overhead, offering valuable guidance for battery management system (BMS) designers seeking optimal performance under constrained resources. Future work may further explore advanced data augmentation and domain adaptation techniques to enhance these models’ robustness in diverse operating conditions.Keywords

Lithium-ion batteries (LiB) are the most widely used energy storage technology for electric vehicles (EV) due to their relatively high energy density and extended lifespan. As the global adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) accelerates, Automakers are rapidly transitioning to battery electric vehicles (BEVs) to meet rising consumer demand and regulatory requirements, with BEV sales reaching approximately 14 million units (18% of total automobile sales) in 2023 and projected to increase to 17 million units, potentially surpassing 20% of the market in 2024 [1]. Within an electrical system, the batteries are managed by a battery management system (BMS) to optimise the system’s performance. Accurate estimation of unmeasurable battery states, such as State of Health (SOH), State of Charge (SOC), and remaining capacity is critical for ensuring the battery operates safely and efficiently. LiB research has garnered substantial attention, particularly in the EV domain, due to its use in high-power applications. The global transition to EVs is primarily driven by the imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions [2]. Consequently, monitoring and diagnosing battery states are vital for real-time controller design, thermal analysis, fault diagnosis, and BMS development in EVs. Key internal states, including SOC and SOH, directly impact battery lifespan and drivability [3].

The European market is witnessing a surge in EV deployment [3]. However, challenges persist in the second-hand EV market, particularly regarding accurate estimations of SoC and SoH. An inaccurate SOC compromises the prediction of SOH and other essential attributes needed to assess battery condition, ultimately affecting EV performance [4]. Such inaccuracies undermine consumer confidence and pose long-term risks to EV market growth [3]. Continually manufacturing new EVs without addressing these uncertainties in the second-hand market could exacerbate environmental harm. Accurate SOC estimation is, therefore, a pivotal requirement for maintaining vehicle safety and optimising battery lifespan [5]. Although numerous studies have applied machine learning approaches to SOC estimation, many remain confined to controlled environments or highly simulated laboratory datasets [6]. In contrast, our work underscores the importance of real-world driving conditions, including inconsistent temperatures, various environmental factors, and frequent charging-discharging cycles, which introduce significant complexities often overlooked in prior research.

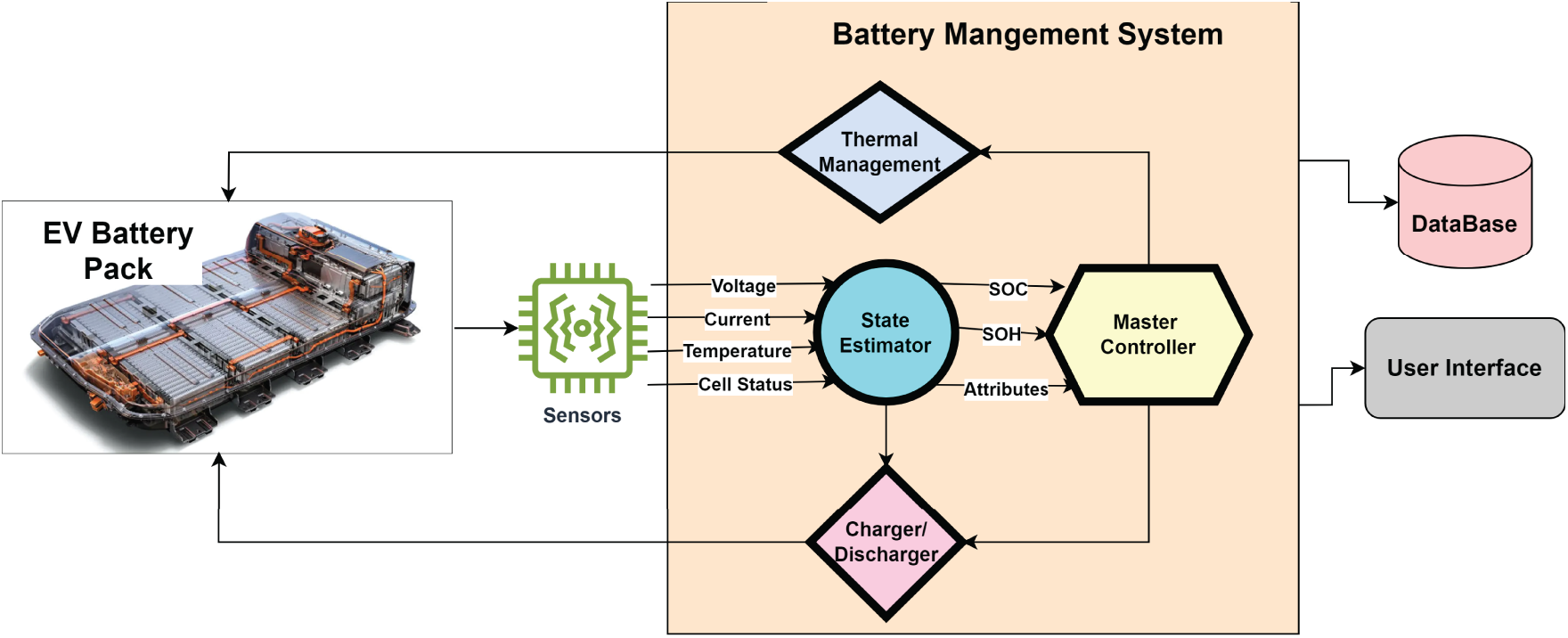

Accurately estimating the SOC of EV batteries is particularly critical for robust battery management systems under variable, real-world conditions. The complexity of SOC estimation arises from the battery’s electrochemical reactions and the many external factors influencing battery health. Traditional methods like equivalent circuits or other electrical models have limitations when aging factors lead to complex parameter identification challenges [7]. Fig. 1 highlights the structure of an EV BMS, emphasising its core function in ensuring both vehicle performance and safety. Central to this system is the EV battery pack, whose voltage, current, and Temperature are continuously monitored by a suite of sensors to guard against overcharging, deep discharging, or excessive heat.

Figure 1: Battery management system overview

The state estimator plays a role in the BMS by processing raw sensor data to generate important attributes. SOC provides essential real-time information on the remaining energy in the battery, while SOH offers insight into the battery’s long-term health and durability. Dynamic SOC estimates inform drivers and vehicle control units about the available driving range, enabling the master controller to optimise battery usage for safety and efficiency. The thermal management system integrates sensor feedback to regulate battery temperature using cooling or heating mechanisms. At the same time, the charger/discharge unit manages the energy flow to prevent damaging overcharge or over-discharge events. The present study investigates the effectiveness of various machine learning models, focusing on two primary tasks: capacity estimation and SOC estimation in LiBs. It begins by reviewing the existing literature on SOC and SOH estimation methods’ ranging from look-up tables and Kalman filters to observer-based and data-driven techniques. An in-depth account of the dataset and data analysis details how raw data was cleaned and prepared for machine learning. Afterwards, customised normalisation strategies are introduced, and the rationale behind model-specific adjustments are explained.

A diverse set of ten architectures are explored, including Deep Learning Neural Networks (DNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Networks (BiDirRNN), Bidirectional LSTM (BiDirLSTM), Bidirectional GRU (BiDirGRU), Deep Belief Networks (DBNs), and Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFNs). Each model is examined to highlight respective advantages and drawbacks in the context of battery data. Following the implementation details, an extensive comparative analysis of each model’s accuracy and computational efficiency performance is presented. Subsequent discussion addresses the implications for battery state estimation, emphasising real-time feasibility in EV BMS applications. Finally, the findings are synthesised to offer insights on integrating these machine learning models into practical battery management systems, thus contributing to the next generation of EV technologies. The discussion addresses the critical gap between academic research in controlled settings and the rapidly evolving requirements of real-world EV deployments.

This paper explores the performance of different machine learning models in terms of capacity and SOC estimation. First, we cover the existing SOC and SOH estimation literature, including look-up tables, Kalman filters, Particle filters, and observer-based and data-driven methods. Next, the dataset and data analysis will include an overview of the data, insights gained from the data exploration, and any steps to prepare the data for use

Battery states such as State of Charge (SOC) and State of Health (SOH) cannot be directly measured by the Battery Management System (BMS). Current SOC estimation methods can be broadly classified into [six] categories: 1) Look-Up Tables (LUT), 2) Impedance-based approaches, 3) Ampere-Hour Integral (AHI), 4) Filter-based methods, 5) Observer-based methods, and 6) Data-driven approaches. LUT utilises the relationship between the battery’s SOC and open-circuit voltage (OCV) [7]. A look-up table is constructed, correlating the OCV to the SOC and allowing SOC deduction from OCV measurement [8]. This relationship for lithium-ion polymer batteries (LiPB) has OCV rising with SOC, allowing for measured OCV to determine SOC [9]. This method can also be used to calibrate errors in SOC estimation. However, accurate measurement of OCV requires load shedding, making this method unsuitable for online SOC estimation, like during EV operation. Therefore, this method is typically reserved for laboratory bench-top tests [10]. The Ampere Hour Integral (AHI) method is more straightforward than the previous options and involves calculating SOC by current integration [11], though it does have its issues. Error is cumulative due to the open-loop calculation, and aging and Temperature can cause differences in rated capacity and coulomb efficiency, decreasing accuracy [12]. Observer-based methods (SMOs), introduced by Luenberger in 1971, estimate state variables for control systems [13]. Advances include research in adaptive Luenberger observer [14], Lyapunov-based observer [15].

Several filter-based methods estimate SOC, falling into two main categories: Gaussian process-based filters and probability-based filter approaches. Gaussian process-based filters are based on the Kalman filter. The Kalman filter operates in a cyclical two-step process. First, it forecasts the state and output of the system; second, it revises the system state based on discrepancies in the output [16]. In a method for estimating the SOC of LIBs using a Linear Kalman filter (LKF), the OCV function is linearized in segments, making it more suitable for SOC estimation [17,18]. The Extended Kalman filter (EKF) linearises nonlinear systems, making it suboptimal for SOC estimation [19]. It expands the OCV function by applying partial derivatives by the linearisation principle of nonlinear functions. Improved methods have been developed, such as Bizeray’s thermal-electrochemical battery model and reduced Order Model with an Extended Kalman filter, whose parameters are temperature-compensated, and EKF estimates SOC [20,21]. In the Adaptive Extended Kalman Filter (AEKF), the covariance of process and observation noise is adaptive, enabling this method to prevent divergence or bias in the algorithm [22]. Xing et al. built an OCV estimation using AEKF, with SOC determined by an OCV-SOC LUT [23]. Xiong et al. later examined SOC-chemical composition relationships, achieving SOC estimation within 3% error using AEKF within a multi-parameter closed-loop feedback system, even with battery aging issues [24]. A study in 2013 proposed an electrochemical model-based SOC estimation method using an adaptive square root sigma point Kalman filter (ASRSPKF) [25], and a recent study achieved a 30% accuracy increase and an 88% reduction in convergence time compared to AEKF [26]. Additionally, advanced Kalman filter variants such as the Adaptive Unscented Kalman Filter (AUKF), Central Difference Kalman Filter (CDKF), and Cubature Kalman Filter (CKF) have been developed, with AUKF demonstrating a minimal 0.028% absolute average error [27,28], CDKF achieving SOC errors below 2% [29], and CKF outperforming EKF in accuracy but being 8.8 times slower [30].

More recent research emphasises applying a data-driven approach, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) to handle the nonlinearities and aging, State of Health (SoH) effects present in lithium-ion batteries [31,32]. As this study employs a data-driven methodology, further insights into these approaches will be provided. In recent advancements, Two notable studies have explored how DNNs can be applied to estimate SOC in lithium-ion batteries for EVs. A recent study introduced a DNN architecture employing dense and concatenate layers with ReLU and linear activation functions. This model was trained on datasets from LG 18650HG2 and Panasonic NCR18650PF batteries across various temperatures (

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are designed to process sequential data by maintaining a hidden state, enabling them to model temporal dependencies effectively [42,43]. In SOC estimation, a study comprehensively analysed RNN architectures, including Vanilla RNN, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU). The findings highlighted GRU’s ability to balance estimation accuracy and computational efficiency, making it suitable for real-time applications under varying battery aging and measurement uncertainties [44]. Further supporting this, a temperature-dependent SOC estimation study compared MNN, LSTM, and GRU models, with GRU achieving the highest accuracy (MAE 2.15%), highlighting its robustness across varying thermal conditions for EV applications [45]. A further developed study introduced a hybrid model combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) with GRU-based RNNs was introduced to enhance SOC estimation further. The CNN component captured spatial features, while the GRU modelled temporal dependencies in charge-discharge cycles. This integrated approach outperformed traditional RNNs, demonstrating higher accuracy and robustness across diverse operating conditions [46]. Another study introduces a novel framework that combines deep learning techniques with conventional diagnostic methods to assess the state of health (SOH) of series-connected lithium-ion batteries. By integrating CNNs for feature extraction and RNNs for temporal sequence modelling, the framework effectively captures complex patterns in battery behaviour. Implementing this method demonstrates significant improvements in monitoring and managing battery systems, contributing to the advancement of battery management technologies [47].

Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Networks (BiDirRNNs) consist of two RNN layers: one processes the input sequence from start to end (forward direction), and the other processes it from end to start (backward direction) [48]. Building upon these approaches, recent research has proposed hybrid deep learning models to enhance SOC estimation accuracy further. One such study introduced a hybrid deep learning model combining CNNs and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks. This model leverages CNNs to capture spatial features and Bi-LSTM networks to capture temporal dependencies in battery data, improving SOC estimation performance [49]. Another study proposed A parallel hybrid model combining a Vision Transformer (ViT) with a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) network to estimate the State of Health (SOH) of lithium-ion batteries. The ViT component extracts features from battery data, while the GRU addresses positional encoding limitations, enabling comprehensive capture of information relevant to battery SOH [50]. Nazim proposed a parallel hybrid approach using RNN-CNN for battery SOC estimation, accounting for various temperatures, discharging cycles, and noisy conditions [51]. Several studies have utilised the NASA B0005 dataset to develop deep learning models for lithium-ion battery state estimation; Shin developed a deep learning approach for SOH estimation, employing RNN, LSTM, and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) models [52]. Furthermore, Tian developed a hybrid model that integrates CNN, BiLSTM, and an Attention Mechanism (AM) to predict the State of Health (SOH) of lithium-ion batteries. Trained and tested on NASA’s B0005 dataset, the model outperformed single models, achieving root mean square errors (RMSE) of SOH predictions below 0.01. These results highlight the model’s high accuracy in SOH estimation [53].

The dataset employed in this study for evaluating deep learning models, NASA cycle dataset B0005, originates from the NASA Prognostics Center of Excellence. It contains nine features and 591,458 instances, as outlined in Table 1. The dataset is an open-source and publicly available resource that comprises charging, discharging, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) profiles gathered until the battery voltage drops to a 2.7 V threshold. SOC Cycles were continued until the battery met end-of-life (EOL) criteria, defined as a capacity fade of 30% from 2 Ah to 1.4 Ah. An initial data integrity check revealed two notable issues. First, the ambient temperature feature contained missing values, leading to its exclusion. Second, two cycles exhibited zero capacity readings, which were replaced using a maximum-value imputation approach to maintain continuity in capacity measurements.

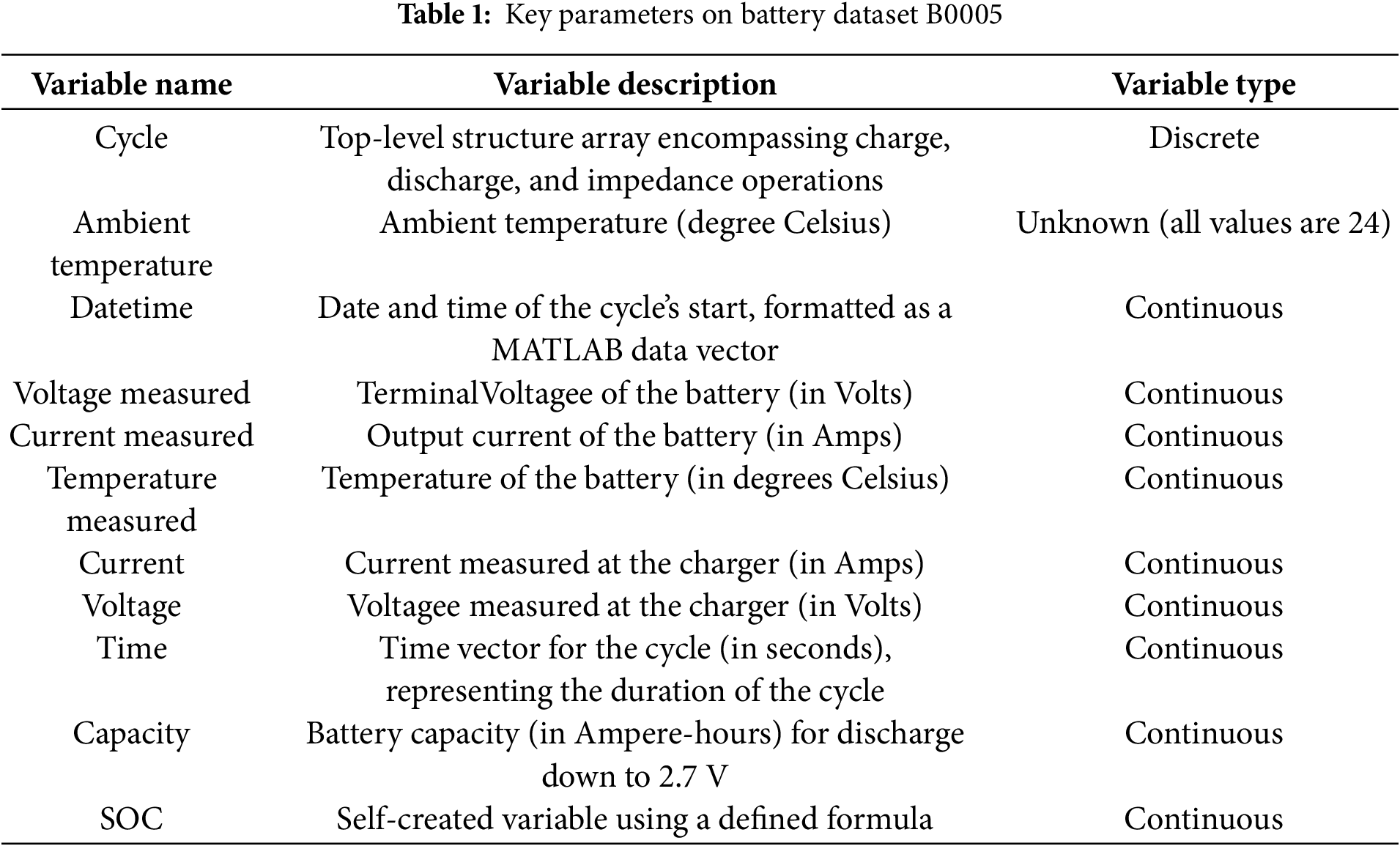

The initial analysis involved checking null values using the pd.DataFrame.info () function and assessing unique values, yielding the following results. “Ambient temperature” was excluded, and capacity analysis revealed two cycles with zero capacity values. The remaining cycles were filled with their respective values using the max value function. From Fig. 2, box plots and frequency histograms show that capacity exhibits a relatively normal distribution. In contrast, the measured voltage exhibited a significant outlier, likely due to measurement error or specification deviation, and was subsequently removed. Following outlier removal, capacity values were normalized, and voltage readings slightly dropped below the 2.7-volt threshold, aligning with the expected lower bound defined by the cell specifications. This normalization ensured data consistency and improved the reliability of subsequent analyses.

Figure 2: Normalised capacity distribution after outlier removal, showing a slight drop in voltage below the 2.7-volt threshold

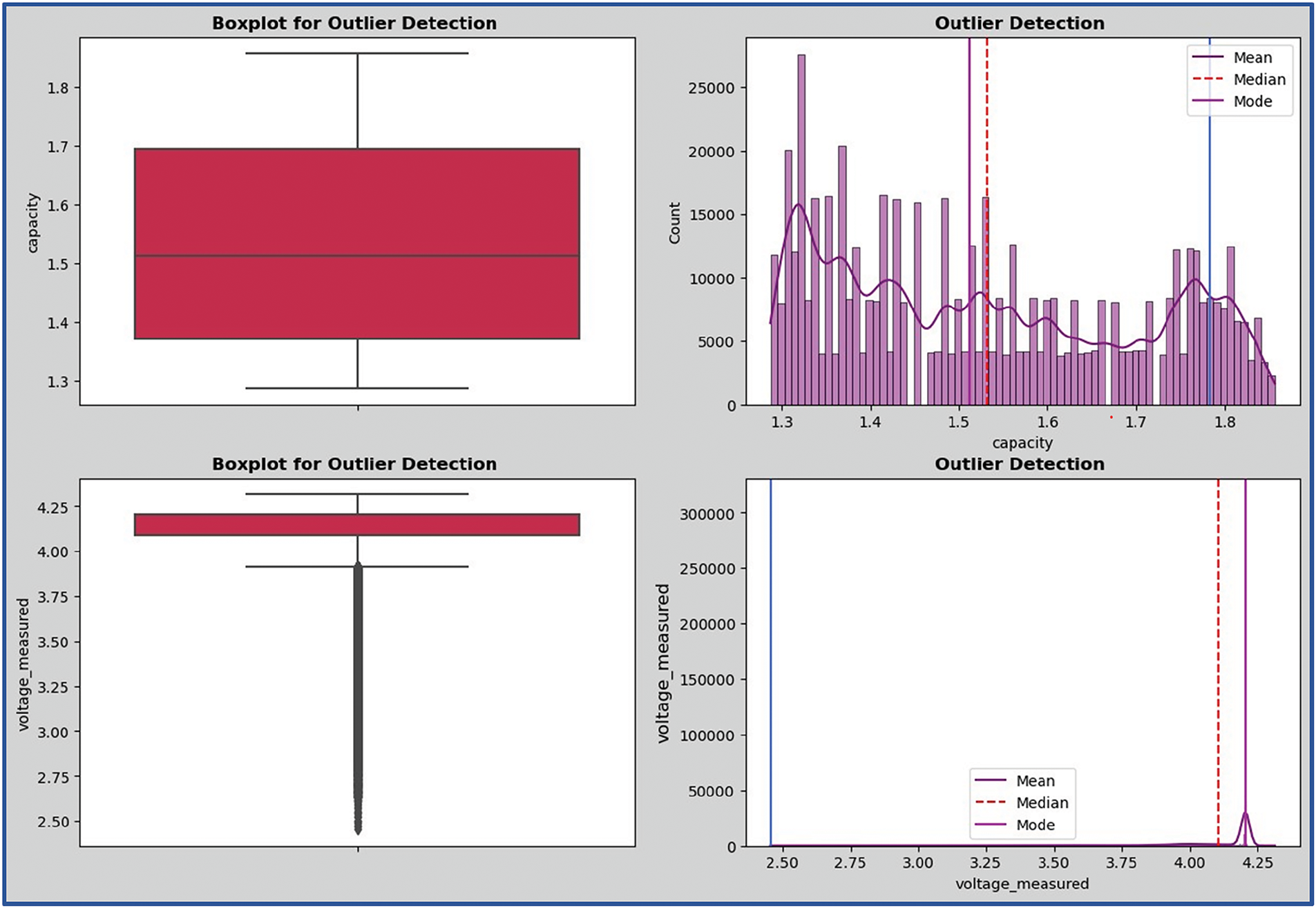

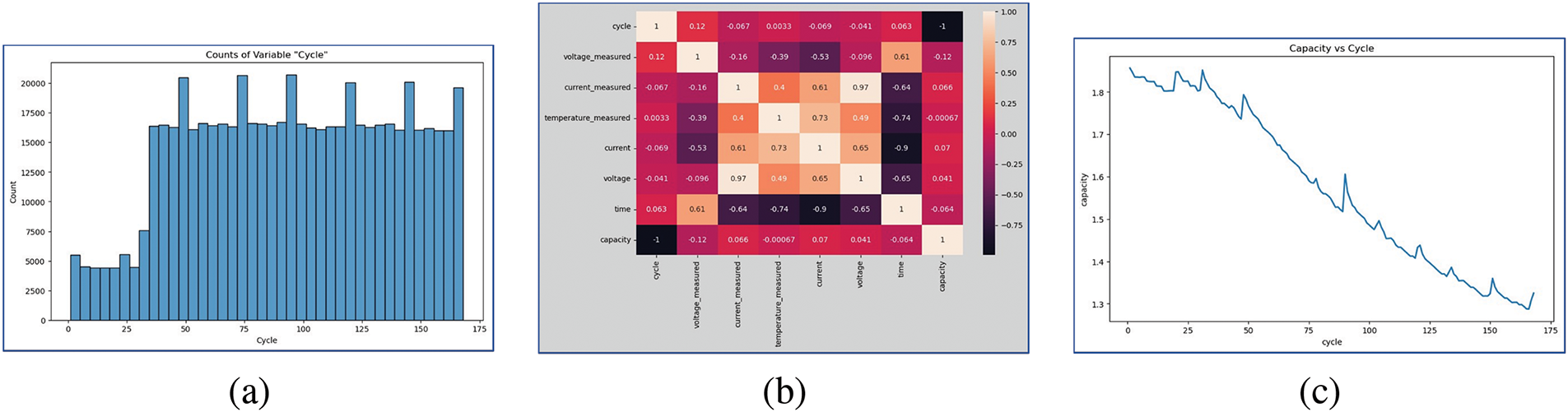

Fig. 3 emphasises the impact of Temperature on battery efficiency, indicating that deviations from optimal Temperature ranges significantly reduce cycle times. These findings underscore the importance of rigorous data preprocessing, including outlier management and appropriate feature selection, to ensure robust model training and evaluation. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the distribution of data points across battery cycles reveals a pronounced imbalance where early cycles are underrepresented. In contrast, later cycles exhibit a denser and more consistent spread. Such an uneven distribution may introduce bias during model training and must be addressed through appropriate preprocessing techniques. In the correlation matrix shown in Fig. 4b, a near-perfect negative correlation between cycle and capacity is evident, reflecting the natural decline in battery capacity over repeated use. Additionally, measured voltage and current display a strong positive correlation, indicating their intrinsic relationship in battery operation. In contrast, capacity weakly correlates with other variables, suggesting that cycle count is the dominant factor influencing capacity degradation. The capacity trajectory across cycles, depicted in Fig. 4c, reinforces this observation by showing a steady decline with minor fluctuations that could stem from operational variations or measurement noise. These insights underscore the critical role of cycle count in battery performance analysis and highlight the importance of managing data imbalance to ensure robust and accurate modeling.

Figure 3: Impact of temperature on battery efficiency, demonstrating a clear correlation between deviations from the optimal temperature range and reduced cycle times

Figure 4: (a) Binned count of variables showing imbalanced data distribution across cycles, with early cycles having fewer points. (b) Correlation heatmap showing a perfect negative correlation between cycle and capacity, with strong correlations between voltage and current and weak correlations elsewhere. (c) Capacity decline over cycles, confirming the expected negative correlation with cycle count

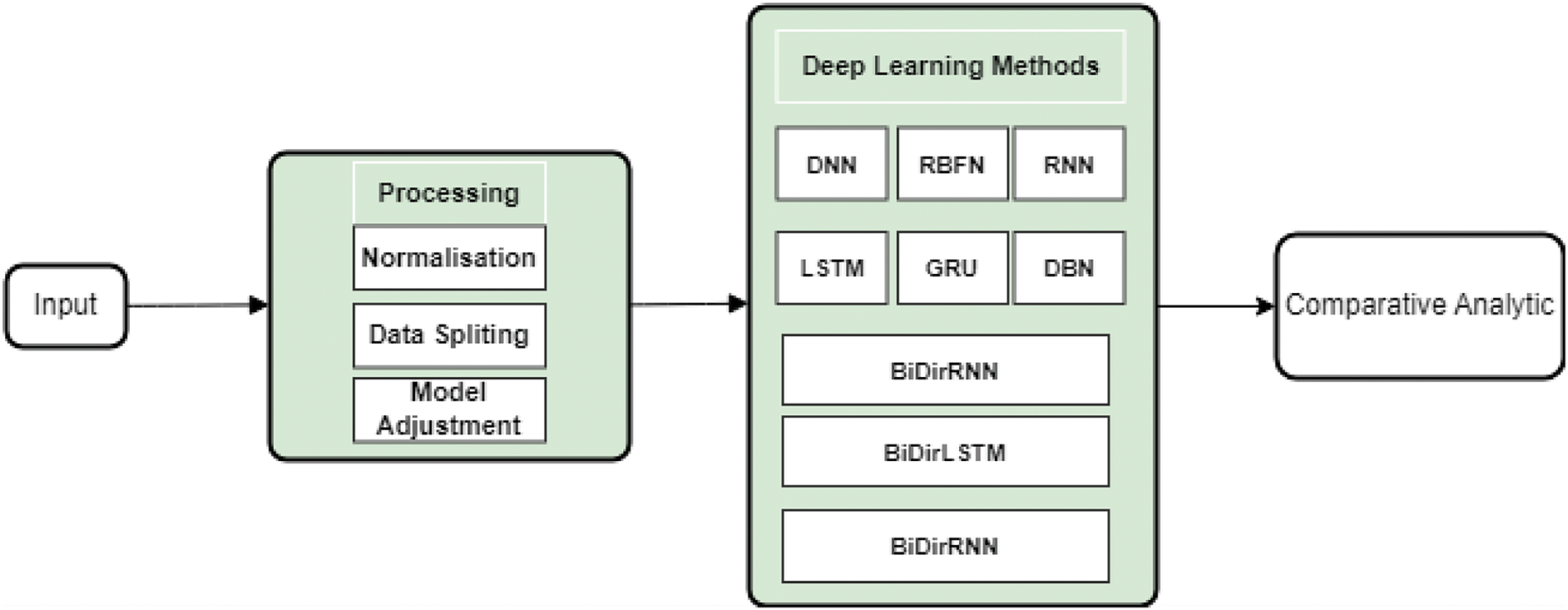

The proposed approach conducts a detailed comparative analysis of ten deep-learning models to estimate battery capacity and SOC using the NASA B0005 dataset. Fig. 5 presents an overview of the research methodology, beginning with data cleaning and normalisation procedures tailored to each model. These steps involve detecting and handling outliers, addressing data imbalances, and applying appropriate scaling techniques to ensure model stability. Subsequently, multiple deep learning architectures are investigated, encompassing Deep Learning Neural Networks (DNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks, and additional variants. Each architecture is configured and trained to evaluate performance in capacity and SOC estimation tasks, emphasising key performance indicators, such as accuracy, root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and computational efficiency. After model training and validation, comparative analyses are performed to identify strengths and limitations under a unified evaluation framework. Results guide the assessment of model suitability for real-time EV battery management system (BMS) applications, considering hardware resource constraints and operational demands. This methodology reinforces how tailored data preprocessing, careful model selection and rigorous evaluation can yield actionable insights into the practical deployment of machine learning in modern battery management systems.

Figure 5: Flow chart of the research methodology

The NASA B0005 dataset was chosen for this project because it is a commonly used reference in SOC estimation research. Additional investigation was conducted to refine model performance and facilitate a deeper dataset understanding. In machine learning, data preprocessing encompasses cleaning, transforming, and organising raw data to optimise model training. This work’s preprocessing steps included handling missing values, data cleaning, and normalisation. Initially, the B0005 dataset was converted and organised using a Python script, initially in the form of “.mat” Matlab files. The process involved loading the file with the SciPy library’s loadmat() function, extracting and structuring data with predetermined titles, and converting the result into a Pandas DataFrame. After loading the data into each Python notebook, a brief analysis was conducted, as detailed in Section 3.1. A single ambient temperature variable and the DateTime variable were removed to enhance computational efficiency. Missing capacity values were addressed by discarding the corresponding battery cycles due to the dataset’s sufficiently large size, ensuring minimal impact on overall representation. An extreme outlier exceeding 8 volts was also identified and removed, as it deviated significantly from acceptable operating ranges.

3.2.2 Normalization, Dataset Splitting, and Model Adjustments

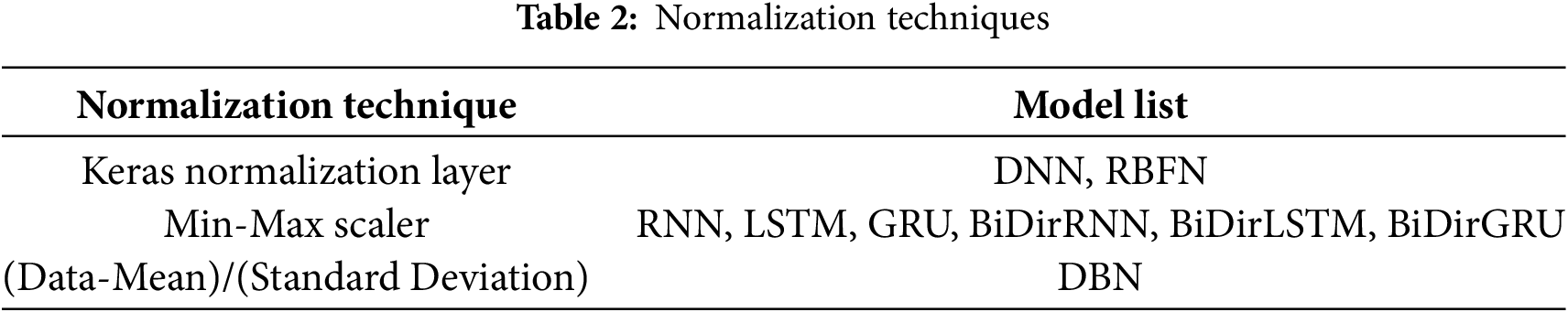

Normalisation was applied individually to each model, consistently derived from the training dataset. The normalisation technique choice was guided by experimental testing and supporting literature. Table 2 outlines the specific normalisation methods adopted for each model. The dataset was split 80:20 for training and testing, and the training portion was further subdivided during model fitting. A constant random seed (0) was applied to maintain consistent splitting and reproducibility across all models. Specific models required reshaping of the input tensors to meet architecture-specific requirements, ensuring appropriate dimensionality for sequential or convolutional layers. Model parameters were fine-tuned through iterative experimentation and referencing established implementations in similar contexts. The final configuration of model hyperparameters is presented in the results section of this paper, offering clarity on each model’s optimal setting for the given dataset. Additional steps were undertaken to enhance model robustness, address potential data imbalance, and ensure comprehensive preprocessing. For instance, random oversampling techniques (e.g., SMOTE) were explored to mitigate the underrepresentation of specific cycles. Noise injection was also considered to simulate sensor inaccuracies and broaden the training distribution.

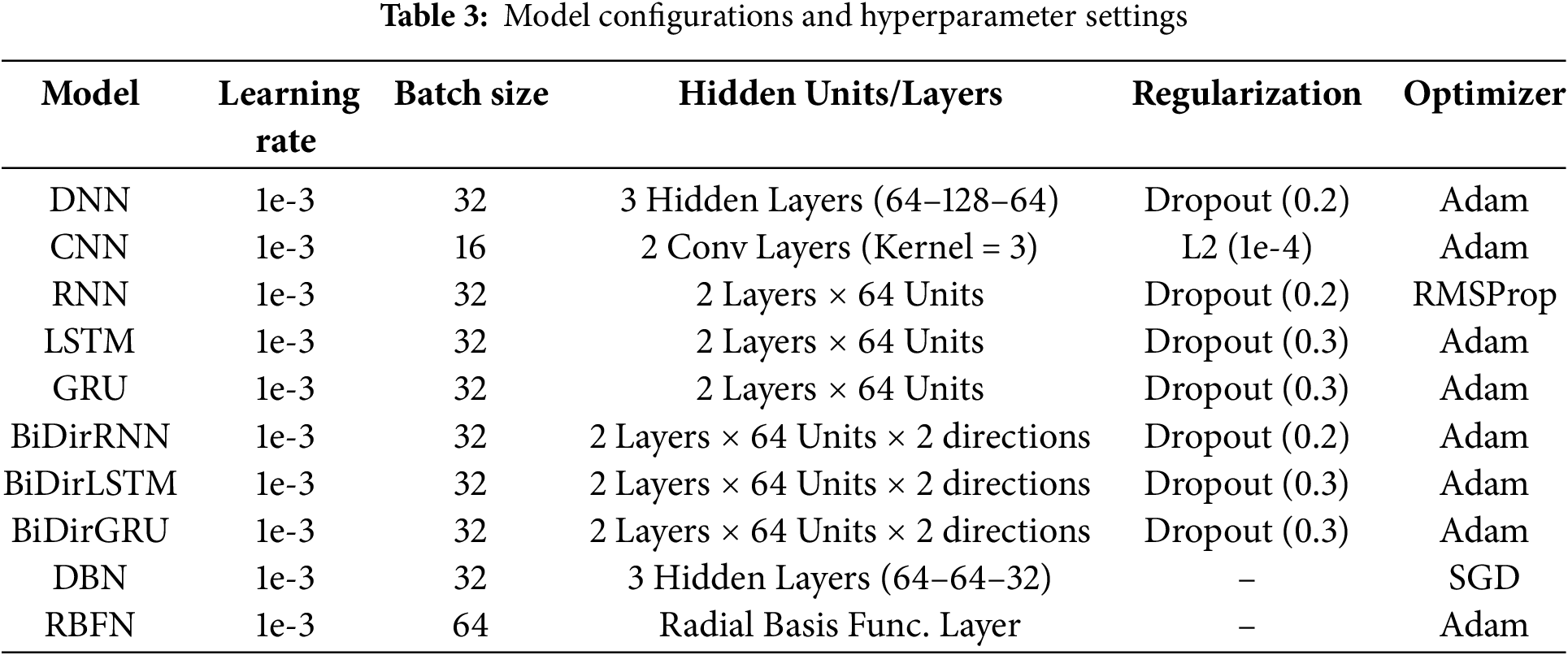

Deep learning approaches have demonstrated substantial promise in capturing complex patterns and nonlinear relationships in lithium-ion battery datasets. The ten models selected for this study, including DNN, CNN, RNN, LSTM, GRU, BiDirRNN, BiDirLSTM, BiDirGRU, DBN, and RBFN, collectively represent a spectrum of architectures capable of handling time-series or quasi-stationary data. Models such as RNN, LSTM, GRU, and their bidirectional variants are particularly suited for sequential patterns in charge/discharge profiles. Feed-forward networks like DNN can effectively estimate capacity in a single-step regression framework. CNN is included for its localised feature extraction capabilities, while DBN and RBFN offer alternative learning paradigms that may generalise differently compared to standard deep architectures. The objective is to evaluate each architecture’s suitability for battery applications with varying computational demands, data structures, and accuracy requirements.

Table 3 summarises key parameters for each model. All models are examined in single rather than hybrid configurations, which means no additional physical or ensemble models have been combined. While hybrid approaches merging physical battery models with machine learning—may enhance interpretability, the primary aim is to compare pure deep learning architectures under uniform conditions. Input data for capacity estimation are treated as quasi-stationary features over each cycle, leveraging aggregated statistics (e.g., voltage, current, temperature) at discrete time intervals. By contrast, SOC estimation employs sequential inputs, enabling RNN-based models to leverage time dependencies across multiple samples. This distinction is central to the neural network selection and input reshaping processes, where models like LSTM, GRU, and BiDir variants excel in capturing hidden temporal relationships. In contrast, DNN and DBN rely on static snapshots of features or manually engineered vectors. Table 3 summarises key parameters for each model; All models are implemented in Python using TensorFlow or PyTorch (depending on best practices for each architecture). Hyperparameters such as learning rate, batch size, and number of hidden units were tuned through grid search and reference to related literature on battery state estimation. Early stopping and dropout layers were employed to mitigate overfitting, especially in deeper models like BiDirGRU and DBN.

To further analyse how well the model performs in predicting the 3765 data points, we take into account four critical metrics: Mean Squared Error (MSE) (Eq. (1)), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) (Eq. (2)), Mean Absolute Error (MAE) (Eq. (3)), and the

4.2 Analysis of Models Performance

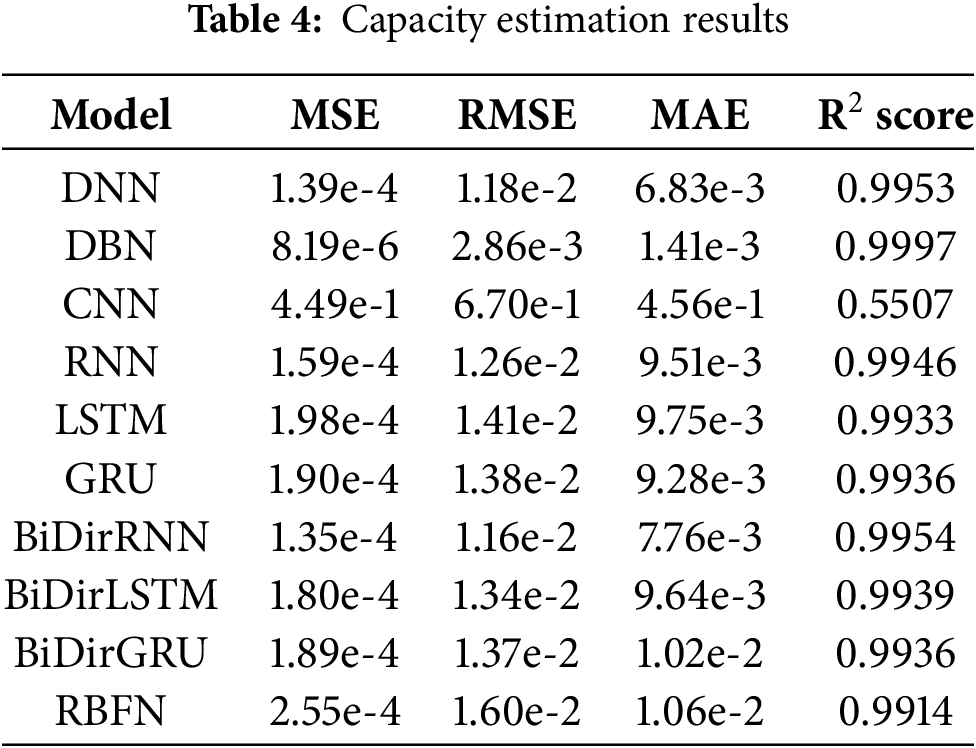

The deep belief network (DBN) performs highest From Table 4, achieving orders-of-magnitude lower error values than the other models. It also attains the best

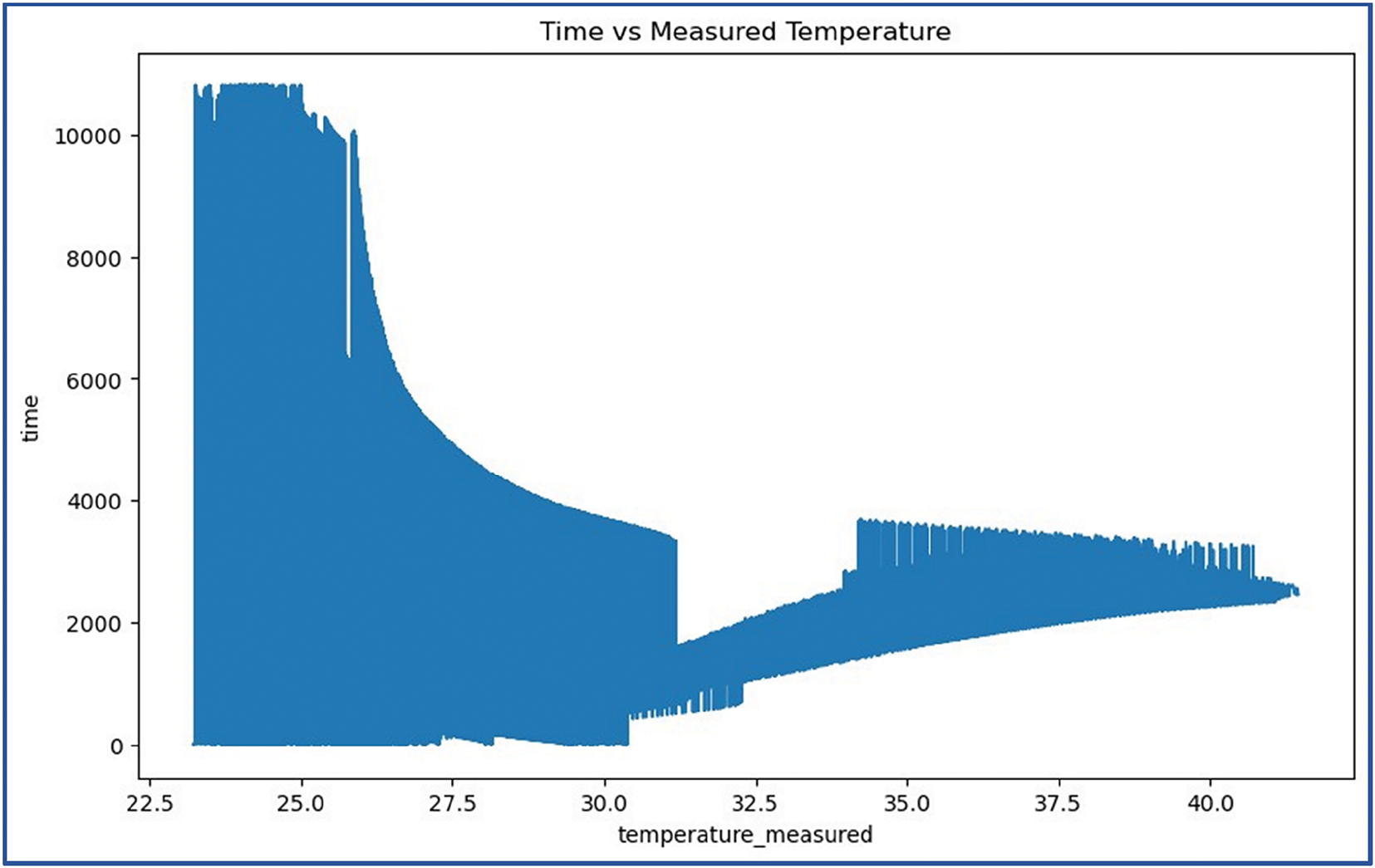

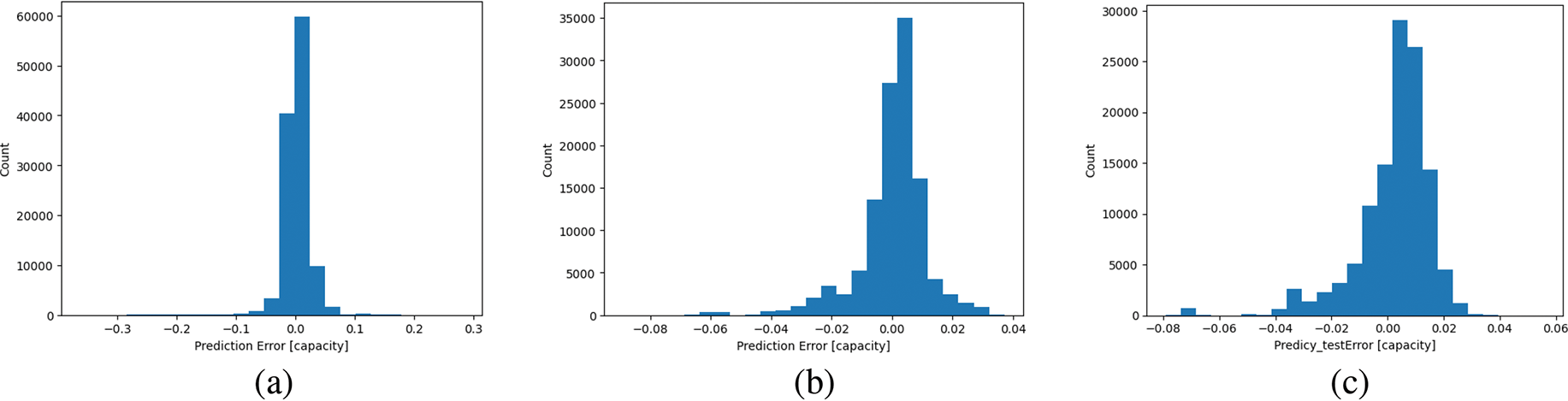

In examining the three top-performing models, DBN, BiDirRNN, and BiDirGRU, A tight clustering of errors around zero is evident. DBN exhibits over 90% of residuals within the range of −0.02 to +0.02 (Fig. 6a), reflecting minimal bias and an unimodal distribution centred near zero, with only a few outliers extending to approximately −0.05 and +0.04. BiDirRNN similarly concentrates around 85%–90% of errors in the −0.025 to +0.025 interval (Fig. 6b), indicating strong consistency, though a small fraction of points appears at extremes of roughly −0.06 and +0.05. Meanwhile, BiDirGRU aligns closely with DBN in maintaining around 90% of predictions within −0.02 and +0.02 (Fig. 6c), highlighting a low overall deviation and a pronounced peak near zero; the few tails extending toward −0.08 and +0.06 suggest rare instances of more substantial misestimation. Accurate capacity estimation is pivotal for electric battery systems’ operational efficiency and long-term viability. Several significant benefits emerge when capacity errors remain within a narrow margin, as demonstrated by DBN, BiDirRNN, and BiDirGRU. First, precise knowledge of remaining capacity reduces the likelihood of overcharging or deep discharging, accelerating battery degradation and diminishing overall lifespan. Second, improved capacity prediction fidelity directly translates into more reliable range estimates, enhancing driver confidence and reducing “range anxiety.” This level of accuracy is especially beneficial in real-world driving conditions, where fluctuating load demands and environmental variations can complicate conventional estimation techniques.

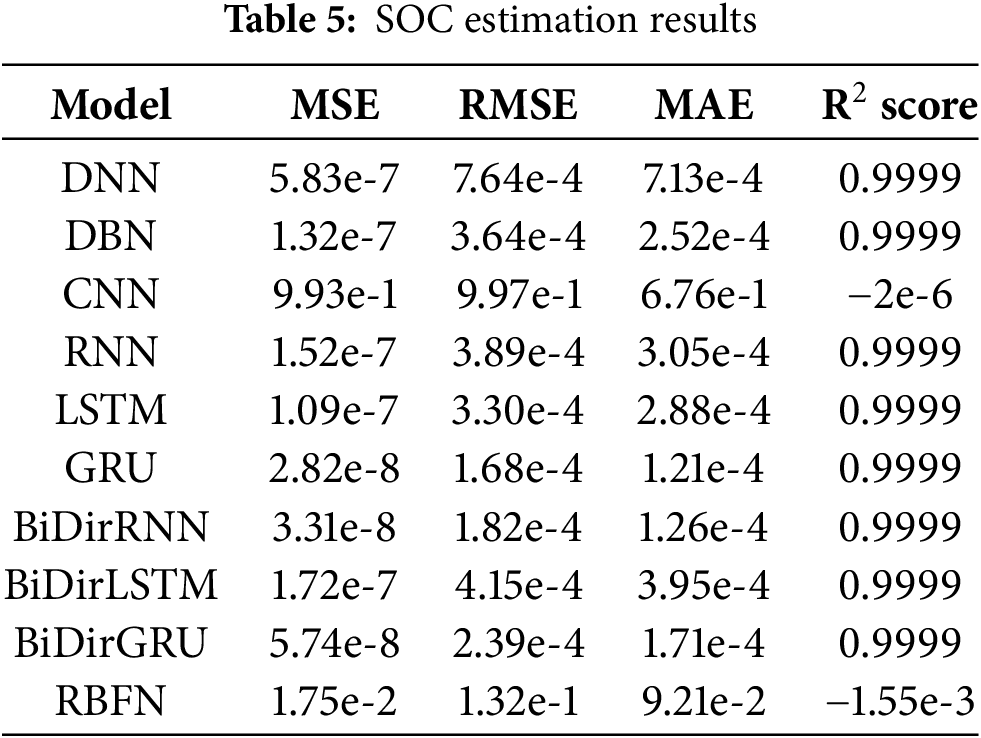

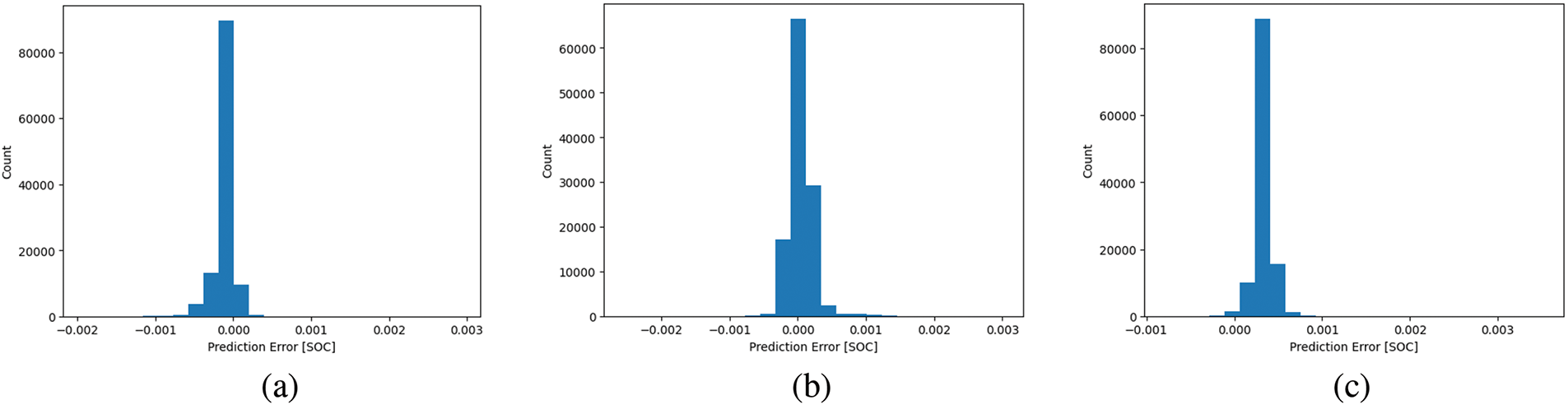

Figure 6: SOC prediction error distributions for top-performing models, (a) GRU with the narrowest spread of residuals; (b) BiDirRNN exhibiting minimal bias and slightly more outliers; (c) BiDirGRU demonstrating a similarly sharp peak around zero and a low overall deviation

SOC estimation is generally more consistent than capacity estimation, except for CNN and RBFN. As shown in Table 5, the highest-performing model is the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), followed closely by BiDirRNN, both attaining

RBFN and CNN show a notable performance drop, with

Figure 7: Capacity estimation error histograms for top-performing models (a) DBN error distribution with over 90% of residuals within −0.02 to +0.02; (b) BiDirRNN histogram showing 85%–90% clustering around −0.025 to +0.025; (c) BiDirGRU exhibiting similar distribution to DBN, with approximately 90% of errors in the −0.02 to +0.02 range

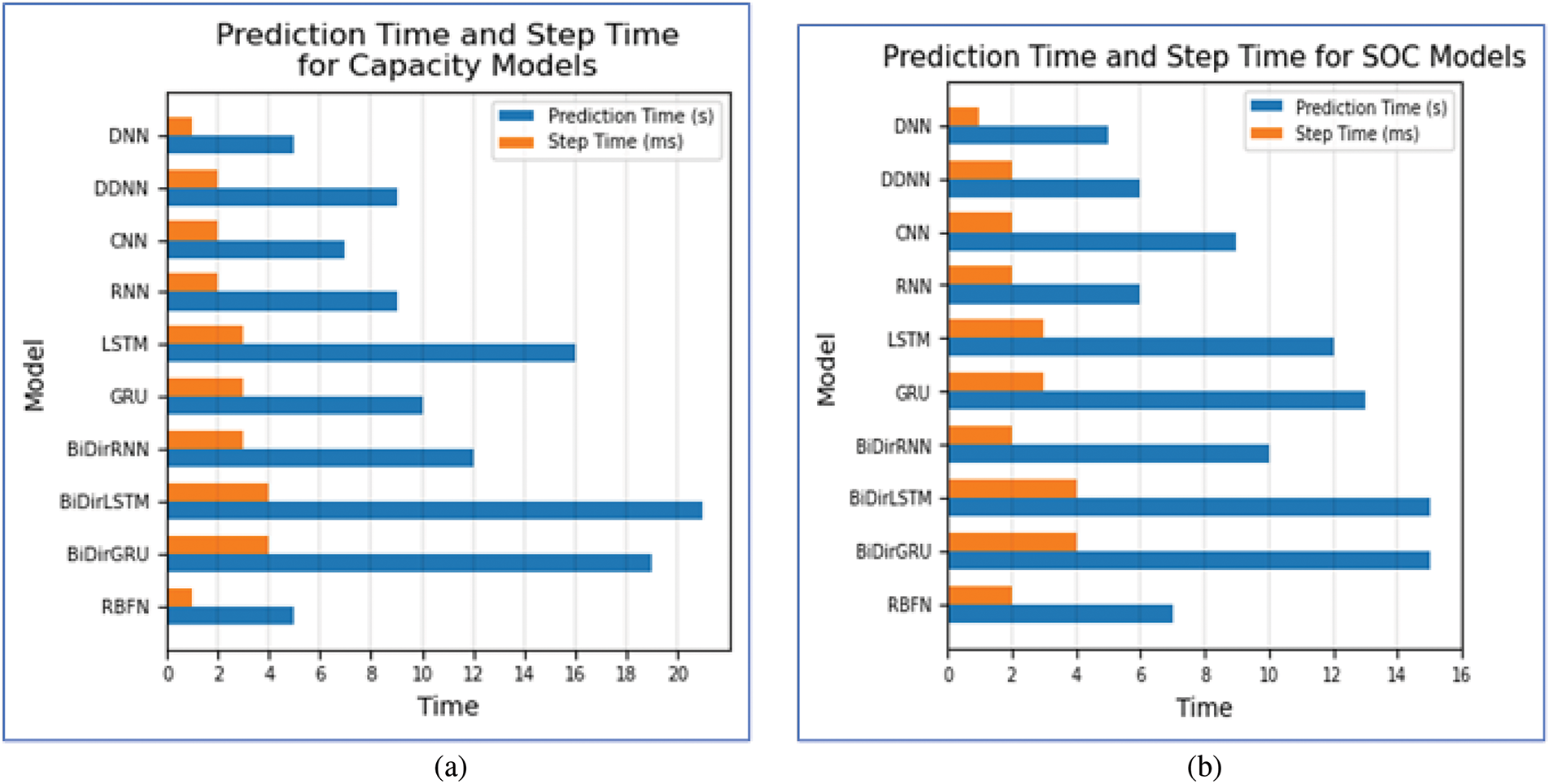

The Fig. 8a and b displays the estimation times of different models for capacity and SOC, respectively. Firstly, it presents the total time required to generate 3765 predictions, illustrated with a blue line. Secondly, it highlights the step time, which is the duration needed to predict a single value, depicted in orange.

Figure 8: (a) Capacity estimation times, (b) SOC estimation times

4.3.1 Analysis of Efficiency Results

It is worth noting that the order of each model’s relative computational efficiency varies in both situations. For example, while BiDirGRU is faster than BiDirLSTM in capacity estimation, it achieves the same computational efficiency in SOC estimation. Despite this inconsistency, the quickest model in both SOC and capacity estimation is the DNN, which is tied with RBFN in capacity estimation. There is also a consistent loss of efficiency in bidirectional models compared to their standard counterparts, though the difference is more minor in BiDirRNN than in the other two. The DBN also fails to double the DNN prediction time in either test, even with double its depth.

DBN remains the most effective model for capacity estimation, offering a significant advantage in accuracy despite ranking fourth in computational efficiency. If computational speed is paramount, DNN is an acceptable choice, delivering respectable accuracy with a 44.4% reduction in prediction times. In SOC estimation, BiDirRNN stands out as the most efficient model, although its accuracy is marginally lower than GRU. The difference in accuracy is relatively tiny compared to the 23.1% increase in computational efficiency that BiDirRNN provides. Conversely, GRU offers superior accuracy if computational resources permit a slight efficiency trade-off. Where efficiency is a critical constraint, DBN remains only 16.7% slower than the DNN but achieves a 77.4% improvement in MSE. Consequently, the DBN may be favoured under rigorous resource limitations. At the same time, CNN and RBFN consistently show the poorest performance across both SOC and capacity estimation tasks and are, therefore, less suitable for real-world applications.

This study systematically examined the accuracy and efficiency of multiple machine learning models for capacity and SOC estimation using the NASA B0005 dataset. An initial review of SOC and SOH estimation techniques—encompassing look-up tables, Kalman filters, Particle filters, observer-based approaches, and data-driven methods—provided context for the subsequent focus on deep learning architectures. The data exploration revealed key attributes and necessitated preprocessing and normalisation steps tailored to each model’s requirements. The comparative analysis demonstrated that CNN performed the weakest across both capacity and SOC tasks. At the same time, DBN emerged as the most accurate model for capacity estimation, albeit with moderately higher computational overhead. The DNN remains a viable alternative if computational efficiency is paramount, offering near-competitive accuracy with significantly reduced prediction times. GRU and BiDirRNN delivered leading results for SOC estimation, with GRU slightly outperforming BiDirRNN in accuracy but incurring a marginal penalty in computational speed. BiDirGRU also performed strongly, reinforcing the robustness of bidirectional recurrent architectures for SOC tasks.

These findings highlight the importance of balancing accuracy and efficiency, particularly for real-time electric vehicle (EV) battery management systems (BMS) applications. Models exhibiting narrow error bands and minimal bias in capacity and SOC predictions are better suited to prolong battery health, optimise charging strategies, and enhance driver confidence in the remaining range. Future research may extend these insights through cross-dataset validation, advanced augmentation methods, or transfer learning approaches to accommodate new battery chemistries and real-world operational variations. By integrating high-performing, resource-efficient models, BMS solutions can achieve excellent reliability and foster wider adoption of electric mobility.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualisation, Zeyang Zhou and Mukesh Prasad; Methodology, Zeyang Zhou and Zachary James Ryan; Software, Zeyang Zhou and Zachary James Ryan; Validation, Utkarsh Sharma, and Tran Tien Anh; Investigation, Zeyang Zhou, Utkarsh Sharma and Zachary James Ryan; Resources, Tran Tien Anh and Zachary James Ryan; Data curation, Zeyang Zhou, and Tran Tien Anh; Writing—original draft preparation, Zeyang Zhou and Zachary James Ryan; Writing—review and editing, Zeyang Zhou, Utkarsh Sharma, Zachary James Ryan, Angelo Greco, Shashi Mehrotra, Jason West and Mukesh Prasad; Visualisation, Zeyang Zhou and Zachary James Ryan; Supervision, Mukesh Prasad. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the NASA Opening Data Portal at https://data.nasa.gov/dataset/Li-ion-Battery-Aging-Datasets (accessed on 6 March 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2024. Paris: IEA; 2024. Licence: CC BY 4.0. [cited 2025 Mar 5]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024. [Google Scholar]

2. Ajao Q, Olukotun O, Lanre SEPS. EPS: an efficient electrochemical-polarization system model for real-time battery energy storage system in autonomous electric vehicles. USA: INDIGO (University of Illinois at Chicago); 2023 Jun 27. [Google Scholar]

3. Global EV outlook 2023: catching up with climate ambitions. Paris, France: International Energy Agency, Global EV Outlook; 2023. [Google Scholar]

4. Ghalkhani M, Habibi S. Review of the Li-ion battery, thermal management, and AI-based battery management system for EV application. Energies. 2022;16(1):185. doi:10.3390/en16010185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Poh WQT, Xu Y, Tan RTP. A review of machine learning applications for Li-ion battery state estimation in electric vehicles. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT Asia); 2022; Singapore. p. 265–9. [Google Scholar]

6. Vidal C, Malysz P, Kollmeyer P, Emadi A. Machine learning applied to electrified vehicle battery state of charge and state of health estimation: state-of-the-art. IEEE Access. 2020;8:796–814. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2980961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Korolev VI. Methods of predictive monitoring of the technical condition of electrical systems. Èlektrotehniceskie I Informacionnye Kompleksy I Sistemy. 2023;19(2):62–72. [Google Scholar]

8. Gao Y, Zhang X, Yang J, Guo B. Estimation of state-of-charge and state-of-health for lithium-ion degraded battery considering side reactions. J Electrochem Soc. 2018;165(16):18–26. doi:10.1149/2.0981816jes. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Barcellona S, Piegari L. Lithium ion battery models and parameter identification techniques. Energies. 2017;10(12):2007. doi:10.3390/en10122007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lee YY, Chan HS, Weber A, Krewer U. Accelerated aging of lithium-ion batteries: insights from nonlinear frequency response analysis. ECS Meeting Abstracts. 2023;2(2):172. doi:10.1149/MA2023-022172mtgabs. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wang Z, Fan X, He Q, Zhang B, Miao Y, Chen H. SOC evaluation of lithium batteries based on VKF, ampere-hour integration and unsteady open circuit voltage fusion method. In: Proceedings of the 2022 15th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (ISCID); 2022; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 228–31. [Google Scholar]

12. Chen Y, Ma Y, Duan P, Chen H. Estimation of state of charge for lithium-ion battery considering effect of aging and temperature. In: Proceedings of the 2018 37th Chinese Control Conference (CCC); 2018; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 72–7. [Google Scholar]

13. Dochain D. State and parameter estimation in chemical and biochemical processes: a tutorial. J Process Control. 2003;13(8):801–18. doi:10.1016/S0959-1524(03)00026-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hu X, Sun F, Zou Y. Estimation of state of charge of a lithium-ion battery pack for electric vehicles using an adaptive luenberger observer. Energies. 2010;3(9):1586–603. doi:10.3390/en3091586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li PC, Chen N, Chen JS, Zhang N. A state-of-charge estimation method based on an adaptive proportional-integral observer. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC); 2016; Hangzhou, China. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

16. Azam SNM. Linear discrete-time state space realization of a modified quadruple tank system with state estimation using Kalman filter. J Physics: Conf Ser. 2017;783:12–3. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/783/1/012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yu Z, Huai R, Xiao L. State-of-charge estimation for lithium-ion batteries using a Kalman filter based on local linearization. Energies. 2015;8(8):54–73. doi:10.3390/en8087854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li J, Min Y, Gao K, Xu X, Wei M, Jiao S. Joint estimation of state of charge and state of health for lithium-ion battery based on dual adaptive extended Kalman filter. Int J Energy Res. 2021;45(9):7–22. doi:10.1002/er.6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Haus B, Mercorelli P. Polynomial augmented extended Kalman filter to estimate the state of charge of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2020;69(2):52–63. doi:10.1109/TVT.2019.2959720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhao S, Bizeray AM, Duncan SR, Howey DA. Performance evaluation of an extended kalman filter for state estimation of a pseudo-2D thermal-electrochemical lithium-ion battery model. In: Proceedings of the ASME, 2015 Dynamic Systems and Control Conference; 2015; New York, NY, USA: ASME. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

21. Bi Y, Zhao X, Choe SY. A hybrid state of charge estimation method of a LiFePO4/graphite cell using a reduced order model with an extended Kalman filter. In: Proceedings of the 2019 American Control Conference (ACC); 2019; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

22. He H, Xiong R, Zhang X, Sun F, Fan J. State-of-charge estimation of the lithium-ion battery using an adaptive extended kalman filter based on an improved thevenin model. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2011;60(4):1461–9. doi:10.1109/TVT.2011.2132812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xing Y, He W, Pecht M, Tsui KL. State of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries using the open-circuit voltage at various ambient temperatures. Appl Energy. 2014;113:106–15. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.07.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xiong R, Sun F, Chen Z, He H. A data-driven multi-scale extended Kalman filtering based parameter and state estimation approach of lithium-ion polymer battery in electric vehicles. Appl Energy. 2014;113:463–76. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.07.061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gholizade-Narm H, Charkhgard M. Lithium-ion battery state of charge estimation based on square-root unscented Kalman filter. IET Power Electron. 2013;6(9):1833–41. [Google Scholar]

26. Bi Y, Choe SY. An adaptive sigma-point Kalman filter with state equality constraints for online state-of-charge estimation of carbon battery using a reduced-order electrochemical model. Appl Energy. 2020;258:113925. [Google Scholar]

27. Partovibakhsh M, Liu G. An adaptive unscented Kalman filtering approach for online estimation of model parameters and state-of-charge of lithium-ion batteries for autonomous mobile robots. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2015;23(1):357–63. [Google Scholar]

28. Peng S, Chen C, Shi H, Yao Z. State of charge estimation of battery energy storage systems based on adaptive unscented Kalman filter with a noise statistics estimator. IEEE Access. 2017;5:202–12. [Google Scholar]

29. He L, Wang Y, Wei Y, Wang M, Hu X, Shi Q. An adaptive central difference Kalman filter approach for state of charge estimation by fractional order model of lithium-ion battery. Energy. 2022;244:122627. [Google Scholar]

30. Peng J, Luo J, He H, Lu B. An improved state of charge estimation method based on cubature Kalman filter for lithium-ion batteries. Appl Energy. 2019;253:1. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang Y, Zhang D, Wu T. Method for estimating the state of health of lithium-ion batteries based on differential thermal voltammetry and sparrow search algorithm-elman neural network. Energy Eng. 2025;122(1):203–20. doi:10.32604/ee.2024.056244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hannan MA, How DNT, Hossain Lipu MS, Mansor M, Ker PJ, Dong ZY, et al. Deep learning approach towards accurate state of charge estimation for lithium-ion batteries using self-supervised transformer model. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19541. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-98915-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Saleem A, Batunlu C, Direkoglu C. Precise state-of-charge estimation in electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries using a deep neural network. Arab J Sci Eng. 2024. doi:10.1007/s13369-024-09870-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. How DNT, Hannan MA, Lipu MSH, Sahari KSM, Ker PJ, Muttaqi KM. State-of-charge estimation of li-ion battery in electric vehicles: a deep neural network approach. IEEE Trans Ind Appl. 2019;56(5):5565–74. doi:10.1109/TIA.2020.3004294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Premkumar M, Sowmya R, Sridhar S, Kumar C, Abbas M, Alqahtani MS, et al. State-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion battery for electric vehicles using deep neural network. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;73(3):6289–306. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.030490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zafar M, Mansoor M, Abou Houran M, Khan N, Khan K, Moosavi S, et al. Hybrid deep learning model for efficient state of charge estimation of Li-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Energy. 2023;282(4):128317. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.128317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ma H, Bao X, Lopes A, Chen L, Liu G, Zhu M. State-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion battery based on convolutional neural network combined with unscented Kalman filter. Batteries. 2024;10(6):198. doi:10.3390/batteries10060198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chen J, Manivanan M, Duque J, Kollmeyer P, Panchal S, Gross O, et al. A convolutional neural network for estimation of lithium-ion battery state-of-health during constant current operation. In: 2023 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference & Expo (ITEC); 2023; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

39. Li Y, Li K, Liu X, Zhang L. Fast battery capacity estimation using convolutional neural networks. Trans Inst Meas Contr. 2020;1(1). doi:10.1177/0142331220966425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Song X, Yang F, Wang D, Tsui KL. Combined CNN-LSTM Network for state-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Access. 2019;7:894–902. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2926517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chen J, Zhang C, Chen C, Lu C, Xuan D. State-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries using convolutional neural network with self-attention mechanism. ASME J Electrochem En Conv Stor. 2023 Aug;20(3):031010. doi:10.1115/1.4055985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Che Z, Purushotham S, Cho K, Sontag D, Liu Y. Recurrent neural networks for multivariate time series with missing values. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):60–85. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-24271-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Ohno K, Kumagai A. Recurrent neural networks for learning long-term temporal dependencies with reanalysis of time scale representation. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Big Knowledge (ICBK); 2021; Auckland, New Zealand. p. 182–9. [Google Scholar]

44. Tao S, Jiang B, Wei X, Dai H. A systematic and comparative study of distinct recurrent neural networks for lithium-ion battery state-of-charge estimation in electric vehicles. Energies. 2023;16(4):2008. doi:10.3390/en16042008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Wang D, Lee J, Kim M, Lee I. Neural network-based state of charge estimation method for lithium-ion batteries based on temperature. Intell Autom Soft Comput. 2023;36(2):2025–40. doi:10.32604/iasc.2023.034749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Huang Z, Yang F, Xu F, Song X, Tsui KL. Convolutional gated recurrent unit-recurrent neural network for state-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Access. 2019;7:139–49. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2928037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Yamacli V. State-of-health estimation and classification of series-connected batteries by using deep learning based hybrid decision approach. Heliyon. 2024;10(20):e39121. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Schuster M, Paliwal KK. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 1997 Nov;45(11):2673–81. doi:10.1109/78.650093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Khan MK, Houran MA, Kauhaniemi K, Zafar MH, Mansoor M, Rashid S. Efficient state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles using evolutionary intelligence-assisted GLA-CNN-Bi-LSTM deep learning model. Heliyon. 2024;10(15):e35183. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Cheng S. A hybrid deep learning method for the estimation of the state of health of lithium-ion batteries. Int Trans Electr Energy Syst. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2025. [Google Scholar]

51. Nazim MS, Rahman MM, Joha MI, Jang YM. An RNN-CNN-based parallel hybrid approach for battery state of charge (SoC) estimation under various temperatures and discharging cycle considering noisy conditions. World Electr Veh J. 2024;15(12):562. doi:10.3390/wevj15120562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Shin J, Joe I, Hong S. A state of power based deep learning model for state of health estimation of lithium-ion batteries, data science and intelligent systems. In: Silhavy RPZ, Silhavy P, editors. Data science and intelligent systems. CoMeSySo 2021. Vol. 231. Cham: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

53. Tian Y, Wen J, Yang Y, Shi Y, Zeng J. State-of-health prediction of lithium-ion batteries based on CNN-BiLSTM-AM. Batteries. 2022;8:155. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools