Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Leveraging Safe and Secure AI for Predictive Maintenance of Mechanical Devices Using Incremental Learning and Drift Detection

1 Department of Information Science and Engineering, Nitte Meenakshi Institute of Technology, Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belagavi, 590018, India

2 Department of Information Science and Engineering, Nitte Meenakshi Institute of Technology, Bangalore, 560064, India

3 Dubai Business School, University of Dubai, Academic City, Dubai, P.O. Box 14143, United Arab Emirates

4 Department of Computer Science and Business Systems, Bapuji Institute of Engineering and Technology, Davangere, 577004, India

* Corresponding Authors: Prashanth B. S. Email: ; Manoj Kumar M. V.. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Safe and Secure Artificial Intelligence)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4979-4998. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.060881

Received 12 November 2024; Accepted 08 February 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

Ever since the research in machine learning gained traction in recent years, it has been employed to address challenges in a wide variety of domains, including mechanical devices. Most of the machine learning models are built on the assumption of a static learning environment, but in practical situations, the data generated by the process is dynamic. This evolution of the data is termed concept drift. This research paper presents an approach for predicting mechanical failure in real-time using incremental learning based on the statistically calculated parameters of mechanical equipment. The method proposed here is applicable to all mechanical devices that are susceptible to failure or operational degradation. The proposed method in this paper is equipped with the capacity to detect the drift in data generation and adaptation. The proposed approach evaluates the machine learning and deep learning models for their efficacy in handling the errors related to industrial machines due to their dynamic nature. It is observed that, in the settings without concept drift in the data, methods like SVM and Random Forest performed better compared to deep neural networks. However, this resulted in poor sensitivity for the smallest drift in the machine data reported as a drift. In this perspective, DNN generated the stable drift detection method; it reported an accuracy of and an AUC of while detecting only a single drift point, indicating the stability to perform better in detecting and adapting to new data in the drifting environments under industrial measurement settings.Keywords

Machine failure prediction and classification is an indispensable perspective in predictive maintenance and industrial engineering. This enables preparedness in handling the machinery failures and executing the strategies for efficiently handling the significant downtime/damage. With increasing machinery complexity and the high costs of breakdowns, businesses leverage data analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence to enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and improve productivity.

Incremental/online learning allows models to adapt to new data, making it ideal for real-time environments. The working of incremental/online learning is contradictory to traditional batch learning. These methods update models continuously for timely maintenance, thereby reducing downtime in industrial settings. The benefits of incremental learning are memory efficiency and adaptability. Though this kind of learning involves challenges such as catastrophic forgetting, effectively handling the situation of concept drift, where data evolves, is crucial for models to remain applicable and adaptive. Incremental learning mechanisms provide real-time insights, driving advancements in predictive maintenance.

Concept drift presents a significant challenge in evolving settings and environments. In this particular type of setting, distributions of data change over time, affecting the predictive maintenance model parameters [1,2]. Continuous sensor data capture operational changes caused by wear, environmental factors, or adjustments. Incremental learning algorithms handle such drift. It is done with the help of retraining the models with new data, periodic retraining, and ensemble methods. Real-time performance monitoring ensures accuracy. This also plays a pivotal role in signaling the need for adjustments. Adaptive learning techniques combined with real-time monitoring maintain robust predictive maintenance strategies. Thereby ensuring minimal downtime and reliability [3,4].

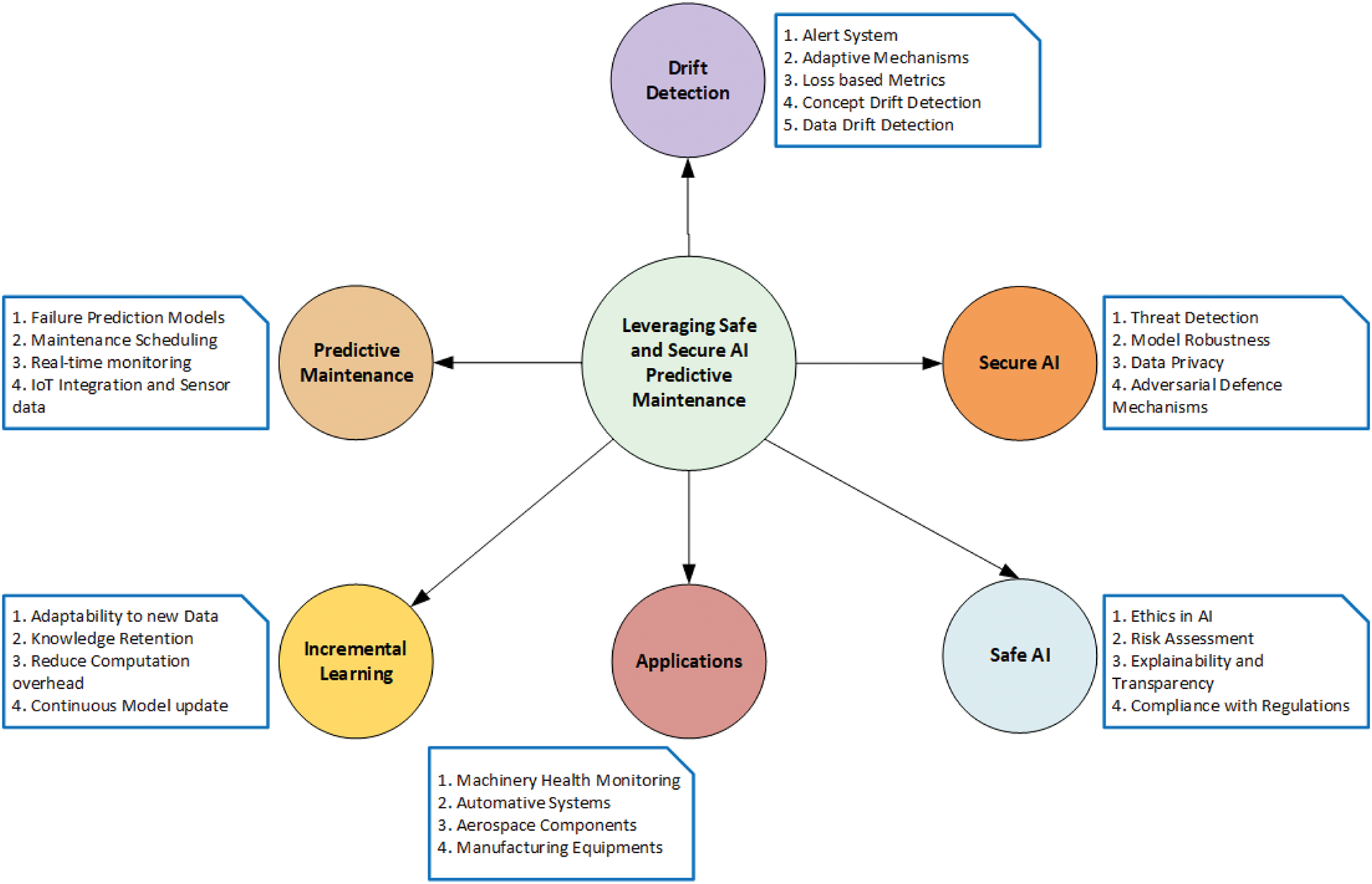

Fig. 1 shows the mindmap for leveraging safe and secure artificial intelligence (AI) in the predictive maintenance of mechanical devices. It has the following key components: safe/secure AI, predictive maintenance, incremental learning, drift detection, and applications. Each of these components portrays an important component in a secure AI system. Safe AI ensures ethical, transparent, and regulation-compliant operations. It plays a multifaceted role in ethics in AI, compliance, risk assessment, and explainability, thereby creating trustworthy models. Secure AI enhances security through data privacy, model robustness, threat detection, and adverse defense mechanisms. Predictive maintenance is pivotal in data collection, failure prediction models, maintenance scheduling, and real-time monitoring. Incremental learning is used in model updates, new data adaptability, reduced computation, and knowledge retention.

Figure 1: Leveraging safe and secure AI for predictive maintenance of mechanical devices using incremental learning and drift detection

Drift detection is important for adapting to changes in data patterns and distributions. Important characteristics include concept drift detection and data drift detection. An alert system ensures efficient response performance. The applications component demonstrates the framework’s applicability across machinery monitoring, thereby emphasizing reliability and early failure detection. These elements act as a cohesive framework leveraging safe, secure, and adaptive AI for effective mechanical device maintenance. This setting ensures enhanced reliability and helps in reducing the downtime.

The following are the objectives of this work:

1. Develop an adaptive incremental learning model for real-time machine failure detection from streaming data

2. Integrate drift detection mechanisms to identify shifts in machine behavior indicative of potential failures

3. Track and visualize model performance over time to observe trends and mark drift points related to machine failure

The organization of the remaining sections is as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on incremental learning within the context of drift detection. Section 4 provides an in-depth discussion of the dataset used and the methodology and algorithms implemented. Section 5 presents insights into the findings and includes an analysis of the results. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the work and discusses potential future enhancements.

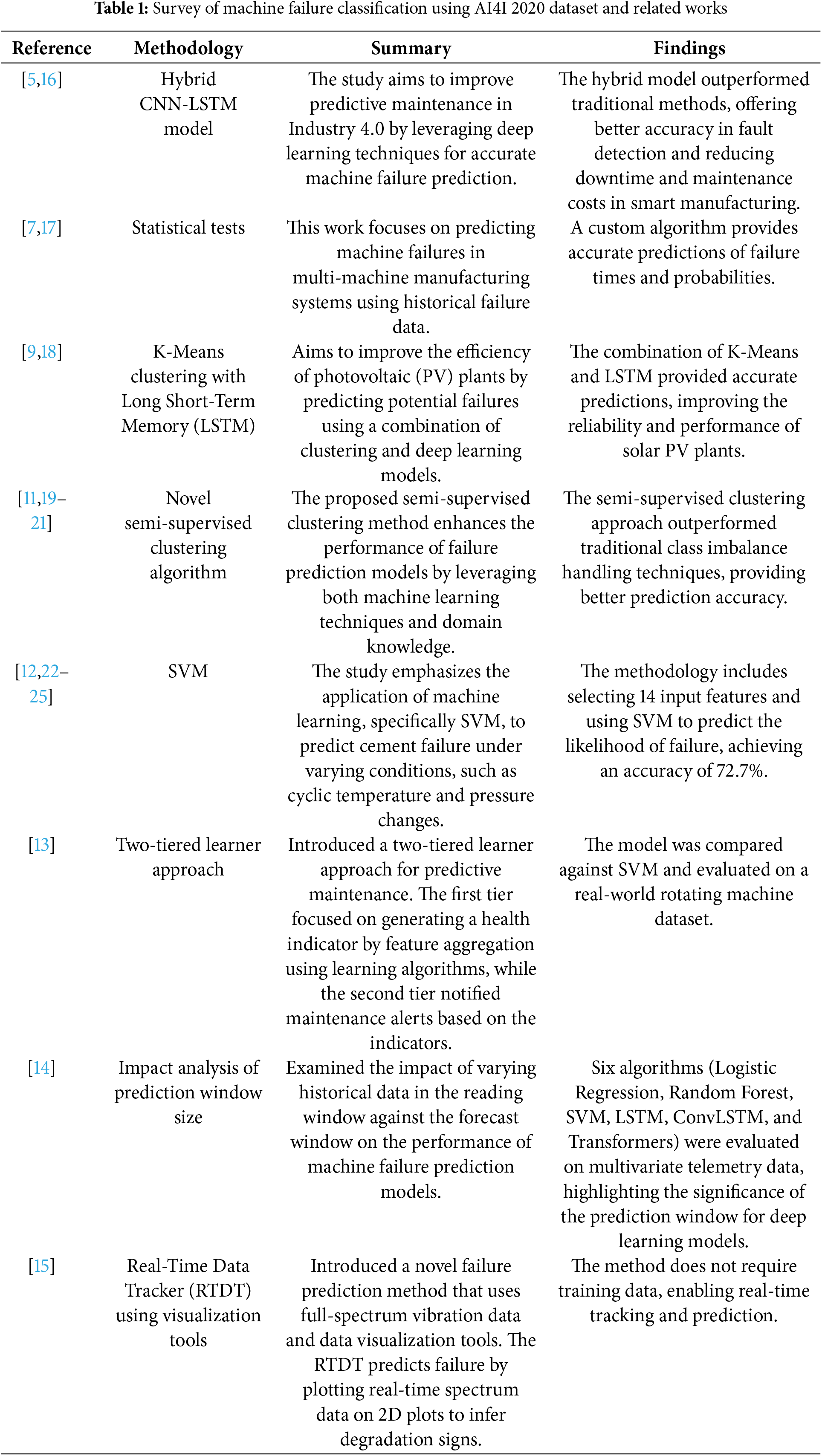

Machine device failure due to environmental factors has been a challenge. To overcome this problem in various machinery-intensive industrial landscapes, many approaches have been employed. With advancements in technology and the introduction of new equipment in the industry, machinery tends to wear out, which can be due to maintenance issues, human error, or mechanical wear. The presented work tries to address this challenge from a different perspective. The work uses the measurement data to estimate machine failures. In this section, primarily, we examine the recent literature. Following the recent literature, the survey methodology is briefly discussed. Relevant literature is examined based on the keyword search from Scopus and IEEE-indexed databases. The papers are picked based on their relevance and published during the years 2020–2024. The list of literature and their respective works is summarized in the table. The research [5,6] presents a hybrid CNN-LSTM framework (CNN-LSTM is a hybrid deep learning architecture that combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM)) for predicting machine failures. The model uses CNNs to extract features, while LSTMs are used to capture long-term dependencies and detect potential failures over time. The framework demonstrated good performance over traditional machine learning models. The work in [7,8] introduces a time-based equipment failure prediction algorithm that uses historical patterns to forecast future failures by using survival analysis. The approach presents the output based on the historical data as a failure forecast, enhances maintenance, reduces costs, and reduces downtime. The paper [9] proposes an approach for reducing operational costs of large-scale photovoltaic plants. The paper [10] focuses on developing a systematic reliability assessment and optimized preventive maintenance strategy for lower limb exoskeleton rehabilitation robots by predicting component degradation and minimizing maintenance costs while ensuring system reliability. The work combined K-Means clustering with LSTM to estimate the predictive maintenance score. The authors have used LSTM solely for detecting anomalies, whereas the K-Means algorithm is used for segmenting data into temperature and irradiance factors. Based on the historical trend, the model was able to forecast equipment failures with a root mean squared error (RMSE) of

The research in [11] presents a method for predicting pipe failures in water distribution networks (WDNs). The data is imbalanced and missing. Hence, the researchers have developed a method wherein the domain knowledge is used in conjunction with unsupervised learning. This approach has improved classification accuracy. Based on the model failure likelihood and cost. The work introduced an economic indicator that ranks pipes for rehabilitation. The paper [12] focuses on predicting the fatigue failure of the cement for maintaining wellbore integrity. This work is related to the oil and gas industry. The study emphasizes the application of machine learning. Specifically, this study employs the SVM to predict cement failure under varying conditions. The study predicts that cyclic temperature and pressure change. The research is based on experimental data and integrates multiple cement-related and experimental factors. The methodology includes selecting

The work [13] introduced a two-tiered learner approach for predictive maintenance. The first tier focused on generating a health indicator. The second tier focused on a decision-making system that notifies maintenance alerts based on indicators. The presented model was compared against Support Vector Machine (SVM) and evaluated on a real-world rotating machine dataset. Researchers in [14] examined the impact of varying historical data in a reading window. It is done against the forecast window over the performance of models. The model was trained to predict machine failures. The work examined six algorithms on multivariate time series data collected from industrial equipment. The study also infers how significant the prediction/forecast window is. This study is evaluated in the context of deep learning architectures for improved performance. The work in [15] introduced a novel failure prediction method. This method uses full-spectrum vibration data using data visualization. The Real-Time Data Tracker (RTDT) tool. RTDT introduced in this work predicts failure by plotting real-time spectrum data on 2-dimensional plots. It is done over the normal data to infer the degradation signs. Also, this method does not require training data.

Table 1 presents the various works related to the context of the research work presented in this paper.

The key findings and research gaps identified are:

1. Most machine learning architectures for modeling machine failure prediction and classification make the unrealistic assumption that the dataset is static and the learning environment is stationary.

2. There is a need to develop models that can integrate diverse data sources, such as sensor data, real-time operational metrics, and historical maintenance records, for more accurate failure predictions in various industries [9].

3. Current models, including CNN-LSTM and SVM-based approaches, often struggle to generalize across different sectors, suggesting the need for scalable models that can be adapted to various industrial domains [5,12].

4. While semi-supervised clustering and other techniques handle imbalanced data, more advanced methods are required to deal with extreme data imbalances and missing values, particularly in real-time applications [11].

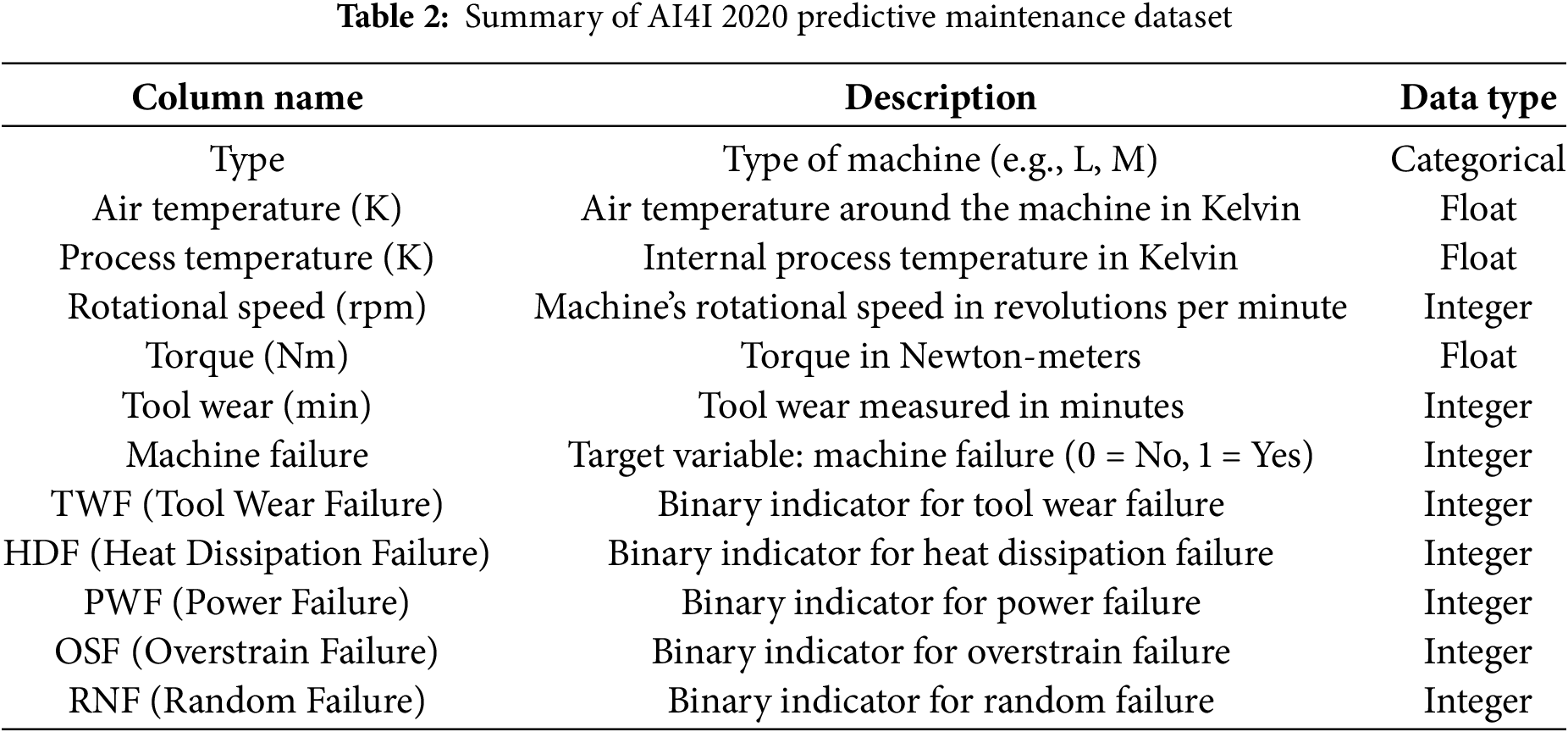

The original dataset is taken from [26] which is the AI4I 2020 Predictive Maintenance Dataset, available from the UCI Machine Learning Repository. The AI4I 2020 Predictive Maintenance Dataset is designed for predictive maintenance research, featuring 10,000 instances of industrial machine data. Each instance records measurements from various sensors, such as air and process temperature, rotational speed, torque, and tool wear, alongside machine type and failure indicators. The target variable “machine failure,” indicates whether a machine failed, with additional binary labels specifying failure modes like tool wear, heat dissipation, power, overstrain, and random failures. This dataset is commonly used to build predictive models aimed at forecasting machine failures and scheduling preventive maintenance. The following Table 2 gives a detailed description of the original dataset.

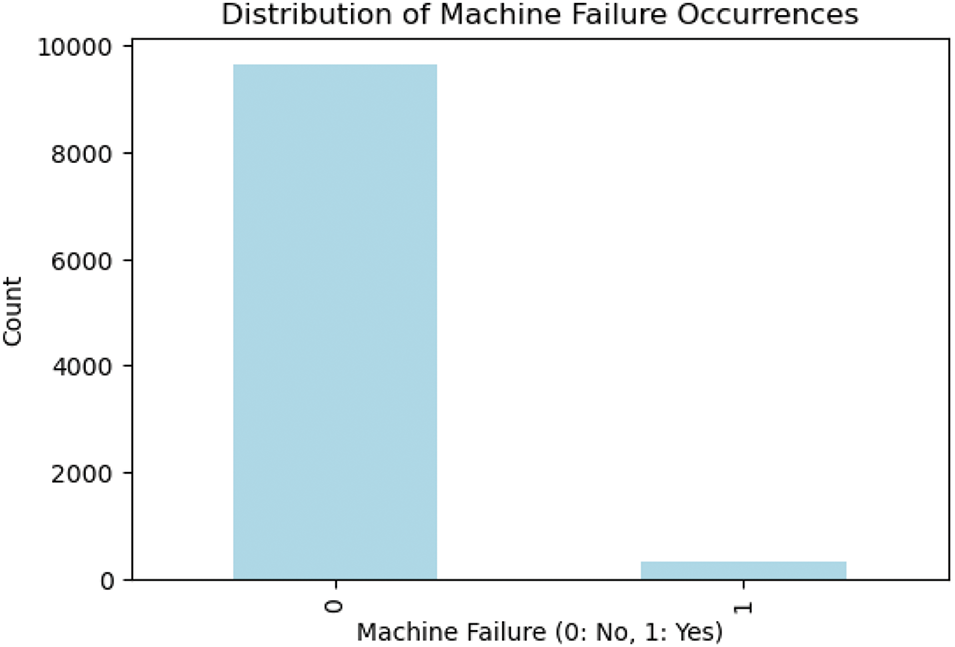

The process depicted in Fig. 2 outlines a structured approach for preparing a dataset from the original dataset, specifically for tasks related to class imbalance and concept drift in machine learning. Following are the steps applied:

1. Data Collection: The first step involves gathering the dataset from various sources, including web-based data repositories or internal data sources.

2. Preprocessing and Data Cleaning: The collected dataset undergoes preprocessing, which includes handling missing values, removing noise, formatting data, and preparing it for analysis. This step is essential for ensuring data quality.

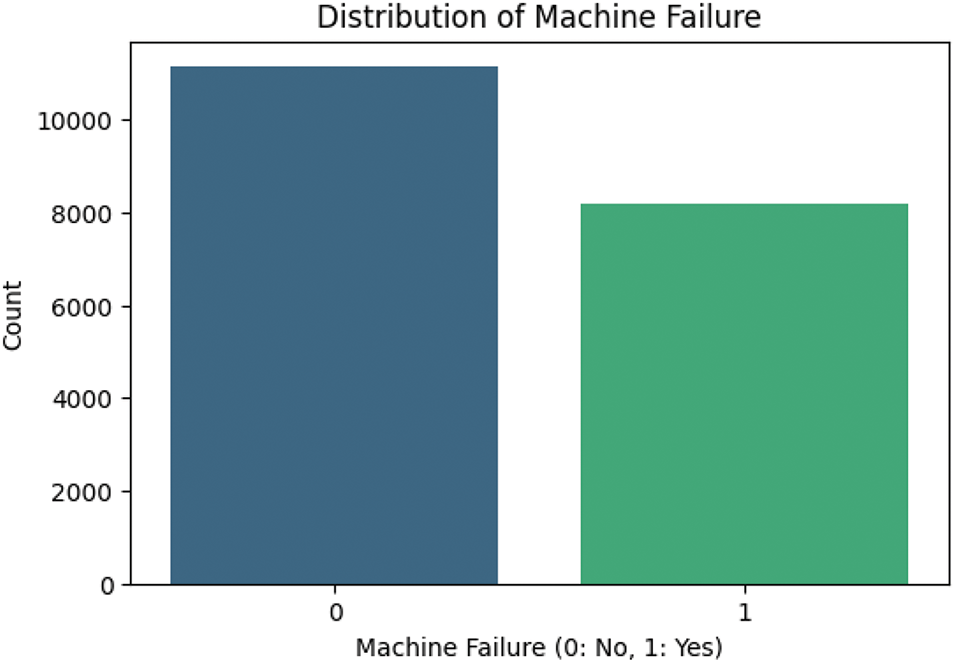

3. Class Label Balance Check: After cleaning, the dataset is checked for class label balance. If the labels are balanced, the process moves directly to exploratory data analysis (EDA) [27,28]. If the labels are imbalanced (i.e., one class has significantly more instances than the other), the process moves to the SMOTE step.

4. Apply SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique): If an imbalance is detected, the SMOTE algorithm is applied to balance the class labels by generating synthetic samples for the minority class [28]. This ensures that both classes are more evenly represented, which is crucial for building accurate and unbiased models.

5. EDA: Once the dataset is balanced, EDA is performed. EDA involves visualizing data distributions, identifying patterns, and understanding relationships among features. This step helps uncover insights about the dataset’s characteristics.

6. Drift Induction: After EDA, the process induces drift in the dataset. Drift refers to changes in the statistical properties of the data over time, simulating scenarios where the data distribution changes, which is a common occurrence in real-world applications.

7. Resulting Dataset: The final output is a clean, balanced, and drift-induced dataset, ready for use in training or testing machine learning models.

Figure 2: Data pre-processing and balancing

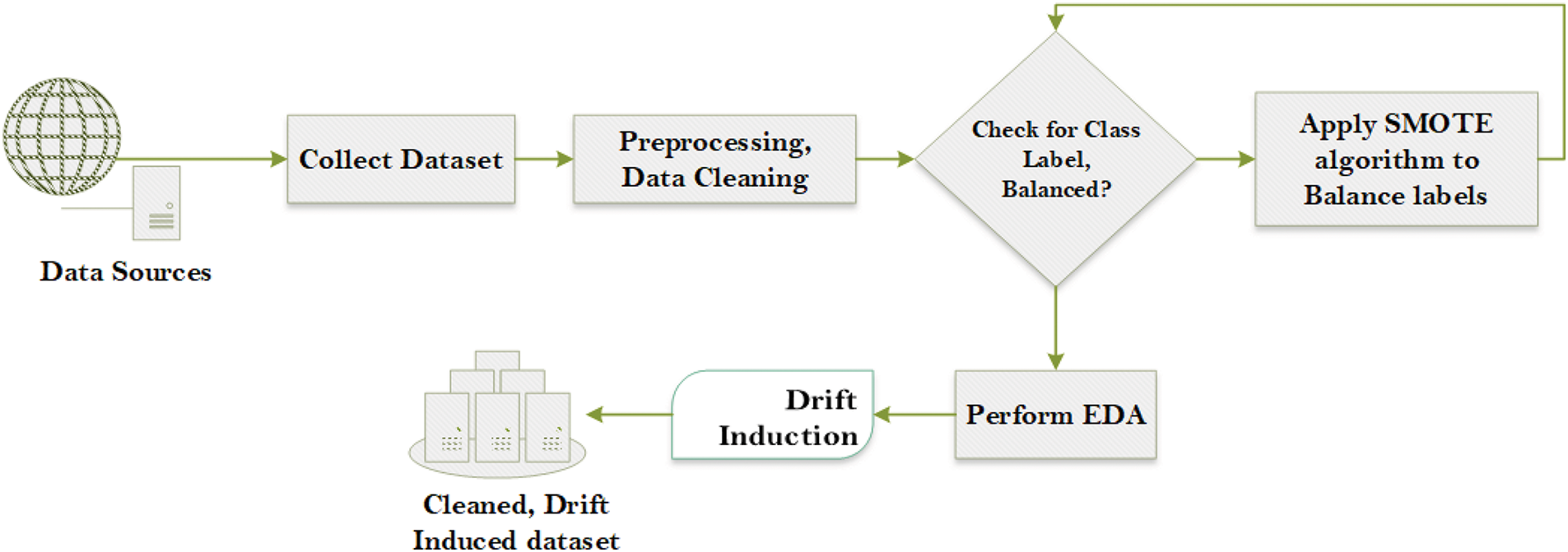

SMOTE is a technique specifically designed to address class imbalance in datasets. When one class (the minority class) has significantly fewer samples than the other, machine learning models may become biased toward the majority class, leading to poor performance in predicting the minority class. SMOTE helps mitigate this issue by artificially increasing the number of samples in the minority class. SMOTE generates synthetic samples by interpolating between existing instances of the minority class. Instead of simply duplicating samples, SMOTE takes each minority class sample and creates synthetic points along the line segments joining any/all of the k-nearest neighbors of that sample. A random neighbor from the k-nearest neighbors is chosen, and a new synthetic sample is created by combining the feature values of the minority instance and its neighbor. This process creates more diversity in the synthetic samples. Concept drift was introduced by selectively flipping the target labels in the dataset. Labels were altered where the torque exceeded a threshold of

Figure 3: Class distribution before SMOTE

Figure 4: Class distribution after SMOTE

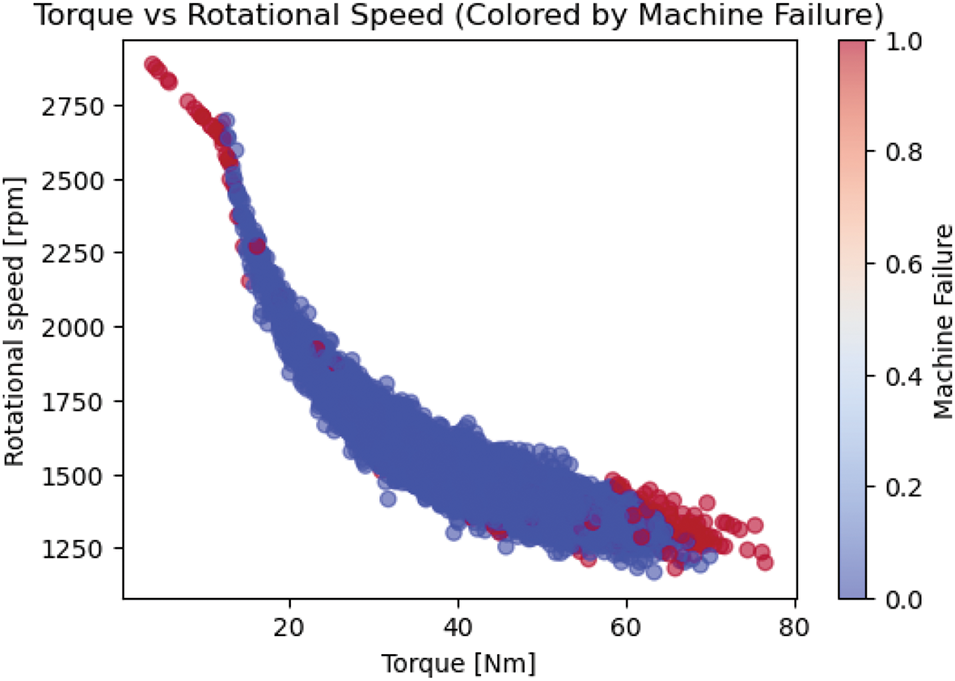

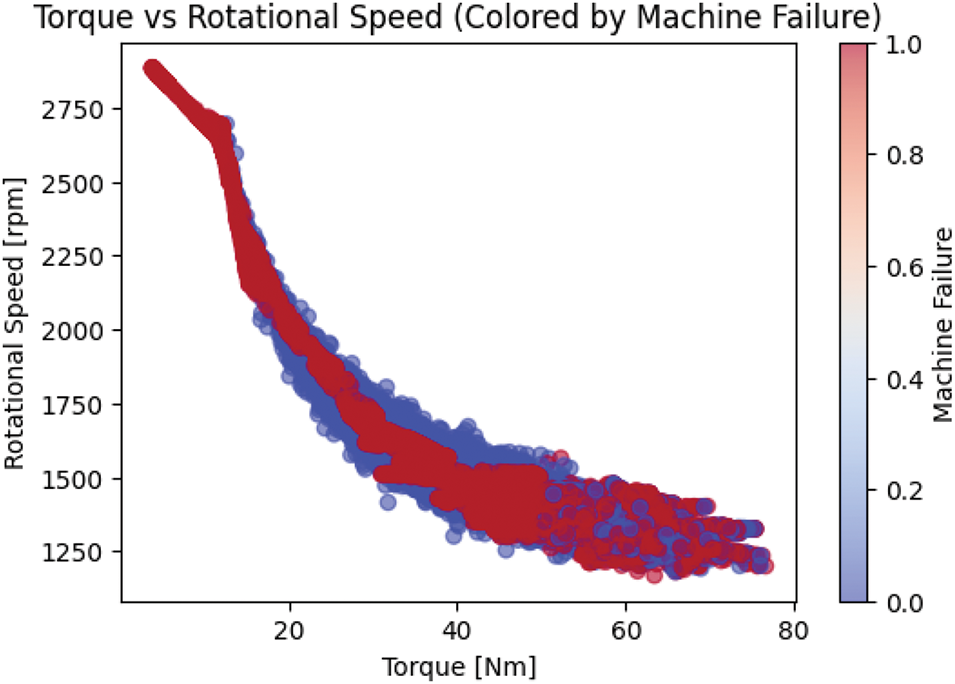

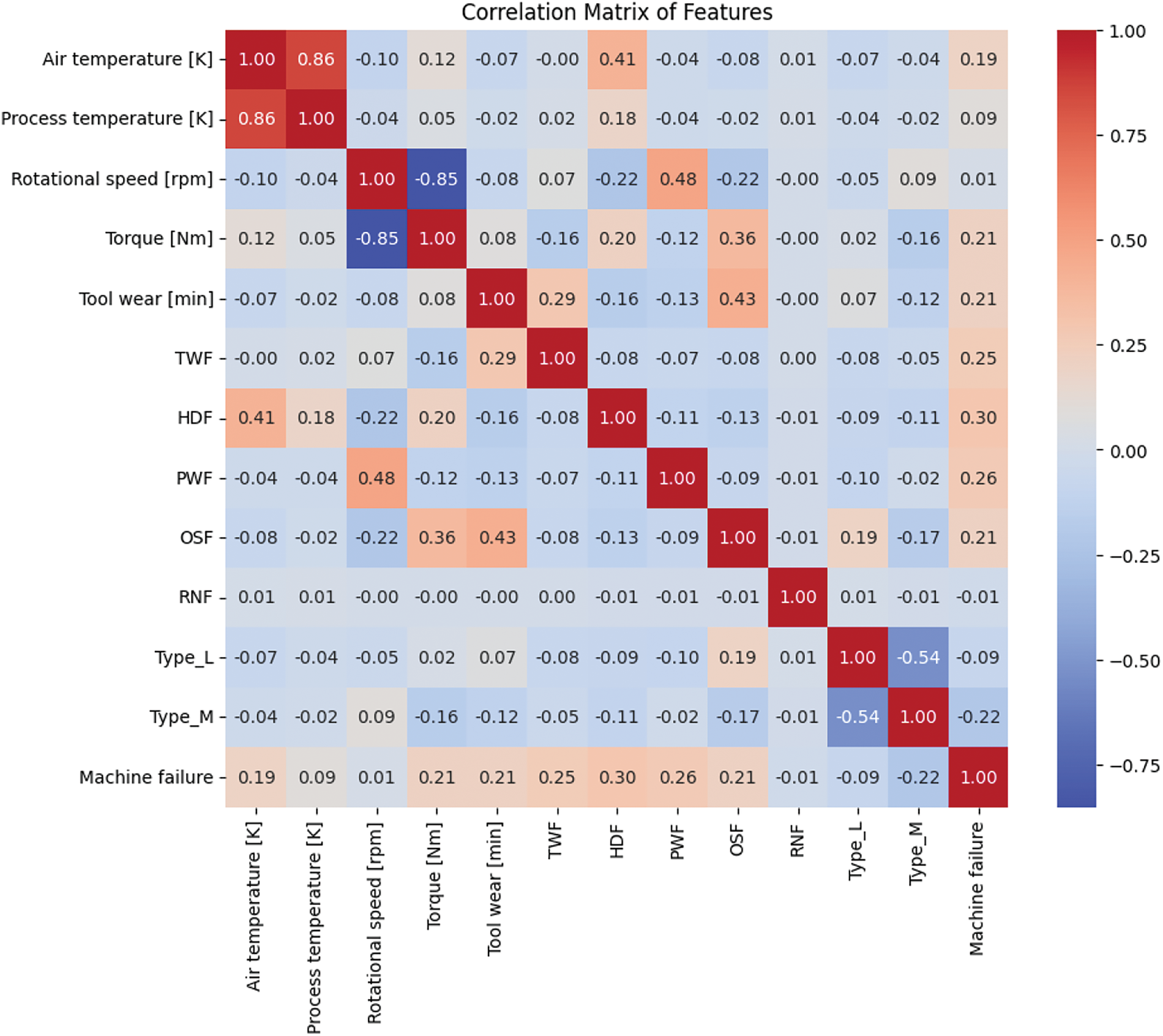

Similarly, we can also observe the change in the properties of features like torque and rotation speed mapped against the Machine Failure class label as shown in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. The overall correlation of the features can be summarized in Fig. 7.

Figure 5: Torque, rotation speed mapped with machine failure label before SMOTE

Figure 6: Torque, rotation speed mapped with machine failure label after SMOTE

Figure 7: Correlation between features and class-label

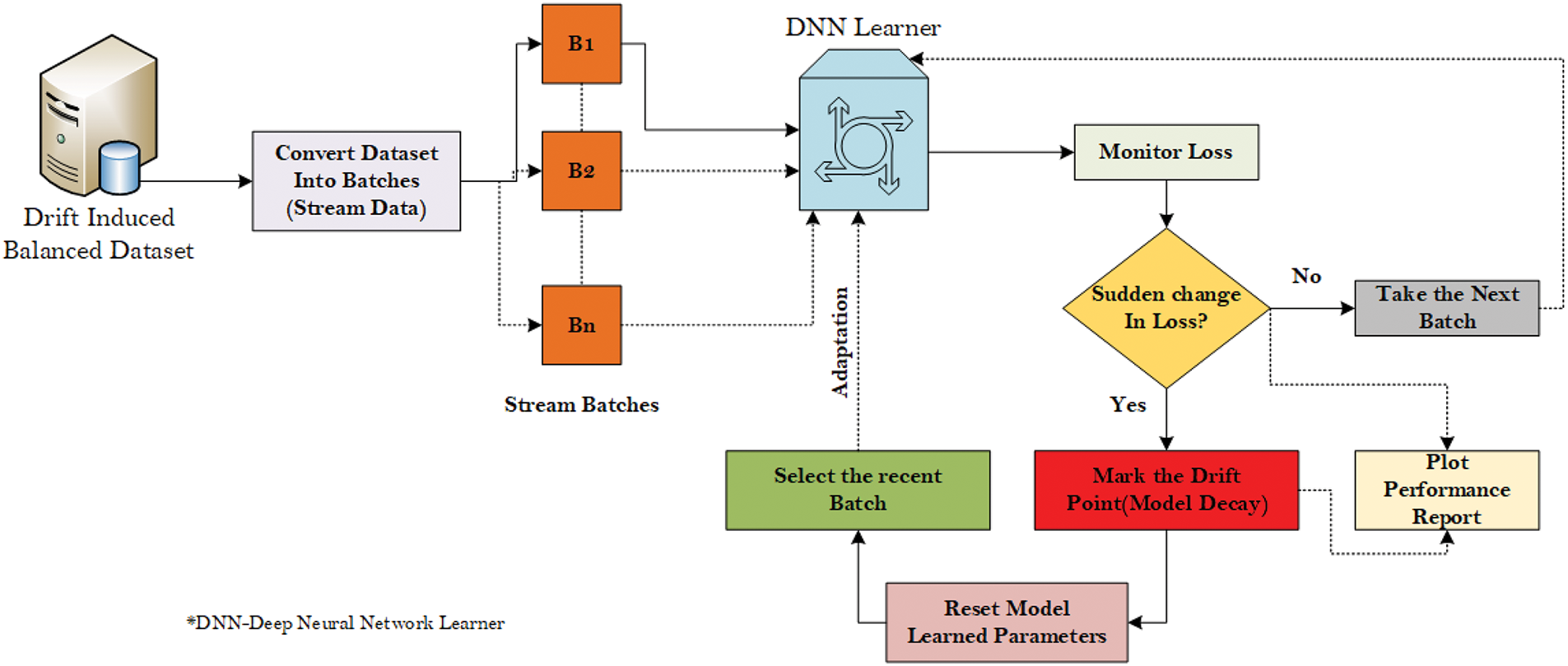

In predictive maintenance, accurately predicting machine failure in the dynamic industrial setting is pivotal to minimizing operational loss in real time. Traditional machine learning assumes a static setting in terms of data measurements and equipment readings from mechanical equipment. But in reality, the entire learning environment can be dynamic, and traditional models, when training in this environment, often face a problem of model decay due to the presence of concept drift. The study addresses this challenge by incorporating incremental learning with a dataset assumed to be streamed into the environment where machine failure is frequent due to environmental factors, operational changes, or machine wear. The overall methodology is as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Proposed architecture

The dataset is first made to resemble a stream of data batches incoming over time batch-by-batch to fit with an incremental learning setup. The dataset was segmented into batches of 20 samples. The learner receives each batch as an input, enabling real-time learning as soon as the data arrives. Initial datasets are used by models to learn their weight, whereas the subsequent batches are used for fine-tuning. This ensures the historical context and newer concepts are learned on the fly without catastrophic forgetting. A few of the batches are held as hold-outs for validation. The dynamic learning rate mechanism ensures that the model doesn’t react to minor changes in the data distribution but instead responds to large changes in the distribution, thus adding resilience to the model. Unlike traditional batch methods, the incremental learning approach mandates the processing of data in smaller, sequential batches to adapt to evolving data distribution in real-time, with few iterations per batch reducing the computational overhead. It also enables the model not to overfit and be responsive when new concepts occur in the data patterns; instead, it learns incrementally to adapt to change.

Fig. 8 shows the detailed architecture of our proposed model. The following are the steps followed:

1. The preprocessed dataset, upon balancing the class labels using the SMOTE algorithm followed by drift induction, is considered as input for the model.

2. The incoming dataset is divided into batches of 20 samples to emulate stream data and each batch is used for training model.

3. The learning model selected here is DNN. The reason for choosing this learner is the innate resilience that persists with DNN on anomalies and outliers and its quick learning capability.

4. During the learning process, we continuously monitor the loss, and we compute the rolling average loss using the previous batches. If the current loss is much greater than the rolling average loss, we identify that the learned concept is drifted due to statistical changes in features and point out the drifting point.

5. Once the drift is identified, we reset the learned parameters and optimizer values and retrain the model with the newest batch that adapts the learner for a new data batch followed by the next set of batches.

6. During this process, the performance charts and graphs are recorded as evidential proof.

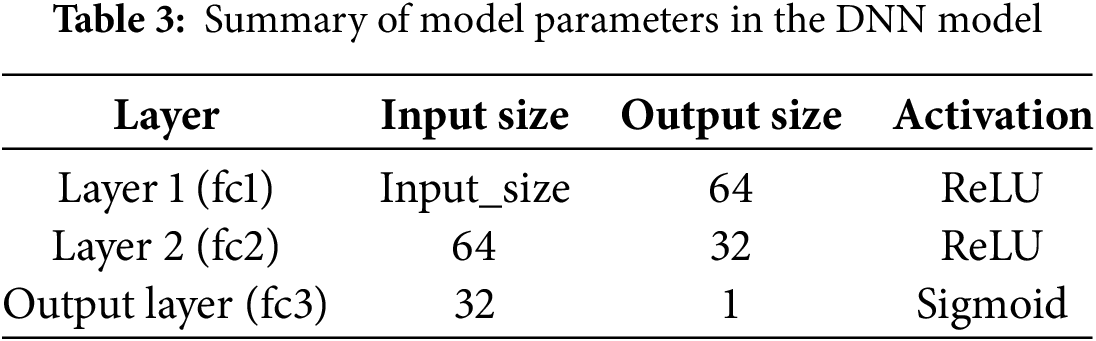

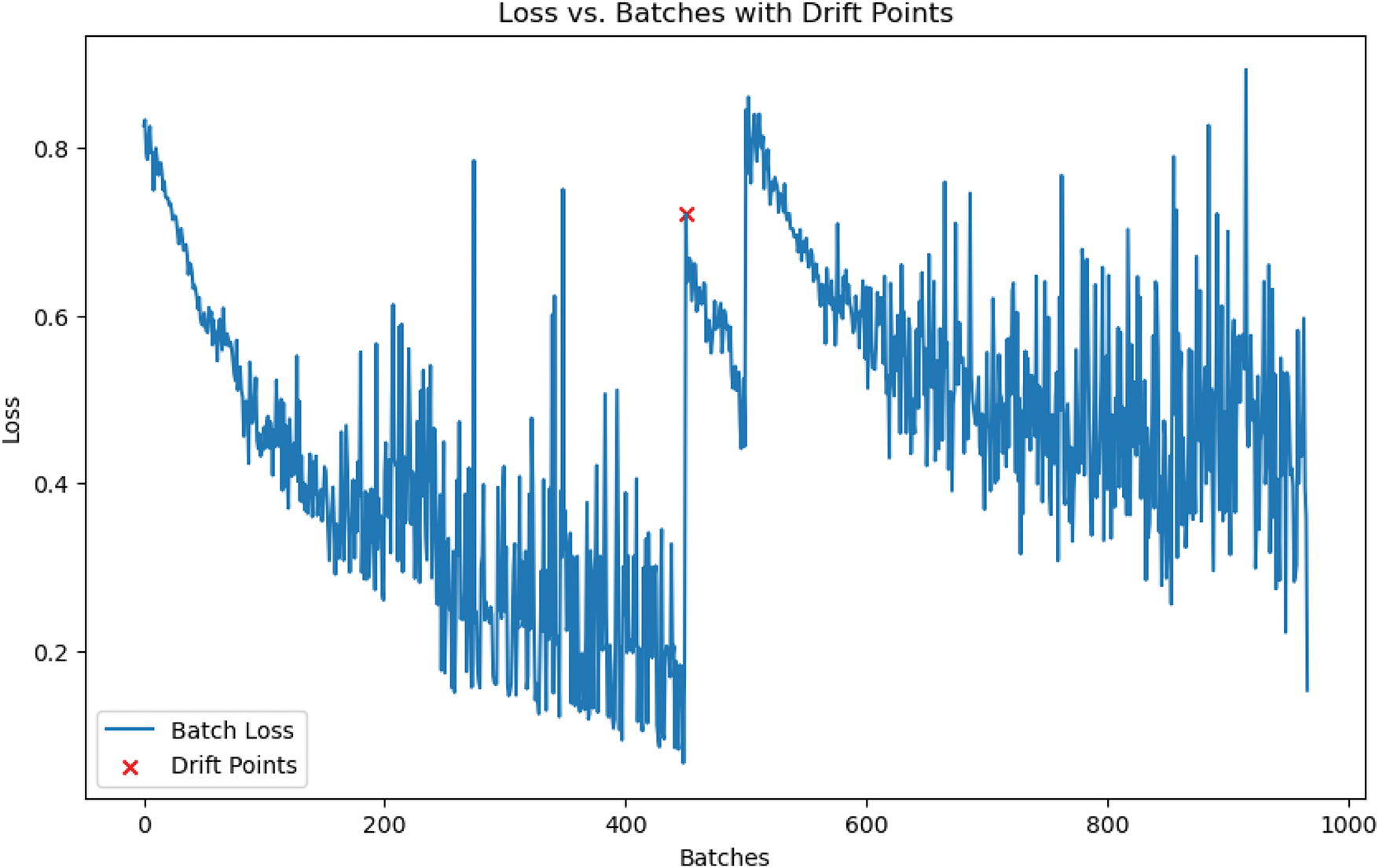

The adaptive learner used in this experiment is a custom DNN, optimized with multiple hidden layers for the binary classification task of predicting whether a machine failure has occurred based on input features. Given an input vector

The first layer applies a linear transformation followed by a ReLU activation:

where

The output of the first layer,

where

The output from the second layer,

where

Overall, the model’s output

This final output,

The algorithm of the presented work is given in Algorithm 1. The algorithm shows the overall process flow of the work, starting from using SMOTE for class balancing, the drift induction process, loss-based drift induction, and adaptive model reset as an adaptation strategy. The SMOTE algorithm is employed to balance the class labels by synthetically generating samples based on the original data without corrupting it. Drift in the dataset was introduced by flipping the class label based on certain features exceeding the threshold. The model was fed with the simulated stream data coming in batches, and during training, the model tracked the loss history and computed the rolling average of the loss. If the current loss exceeds the rolling average by a threshold, it is marked as a drift point, triggering the model and optimizer to reset and adapt to the new data pattern. This ensures that the model can adapt to change over time, providing an incrementally updated model that is resilient even in a dynamic environment.

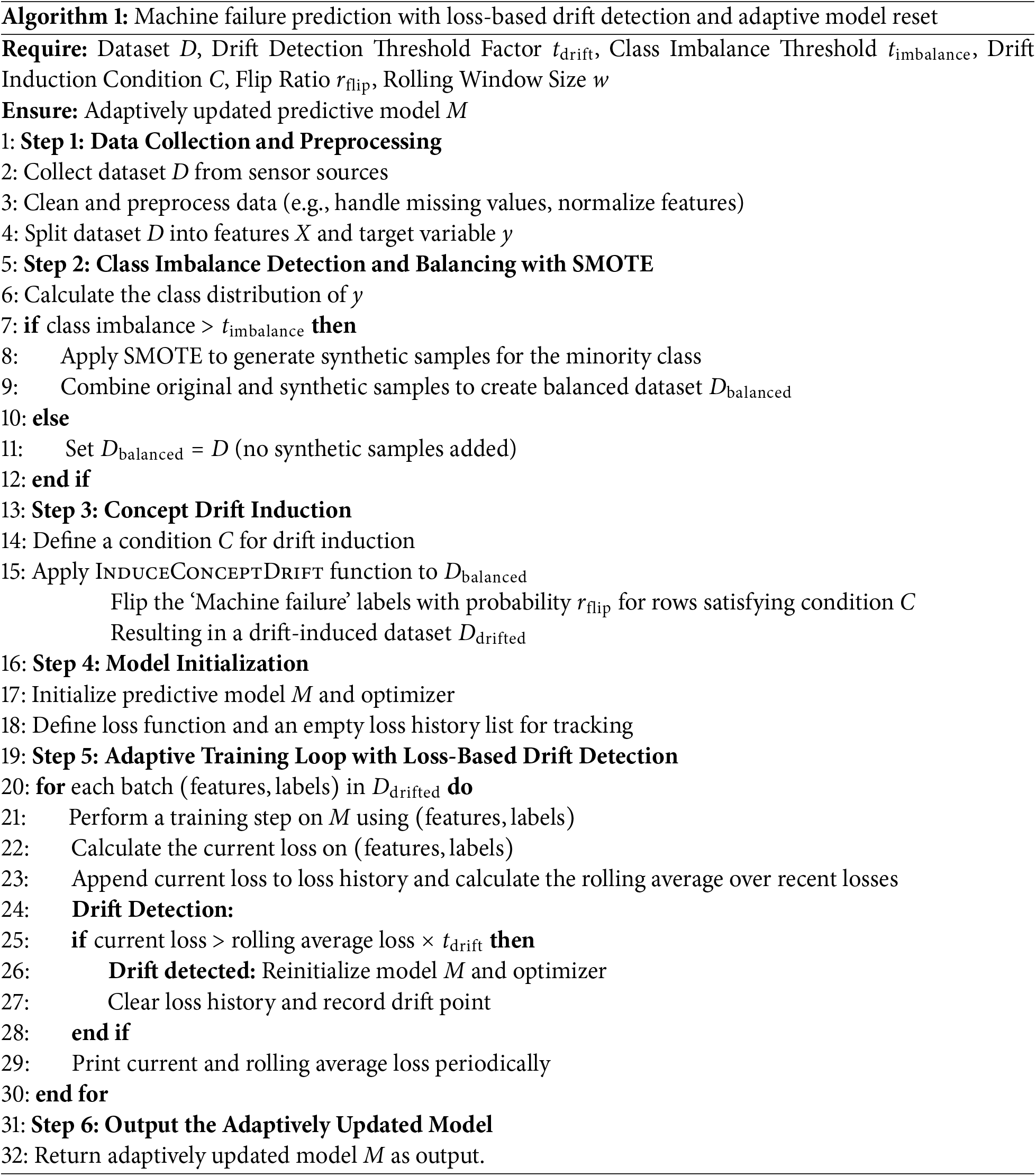

The proposed architecture for machine failure prediction, which uses loss-based drift detection and adaptive model reset, was evaluated using a batch size of 20, a rolling window of

The loss vs. batch plot in Fig. 9 illustrates the behavior of the model across batches, highlighting points where drift was detected. In this experiment, the batch loss was monitored, with a rolling window of 10 batches used to calculate the average loss over recent batches. A drift was detected when the current batch loss exceeded the rolling average loss by a factor of 3 (i.e., drift threshold factor). This detection triggered a model reset, as shown by the red markers in the plot. The model’s ability to reset adaptively allowed it to respond to substantial changes in data distribution, thereby preventing the model from becoming overly biased or inaccurate following shifts in the underlying data. The adaptive reset mechanism is crucial in dynamic environments, as it allows the model to adjust to new data patterns effectively. By recalculating loss within a short window of

Figure 9: Loss vs. batches with drift points. The red crosses indicate detected drift points where the model was reset

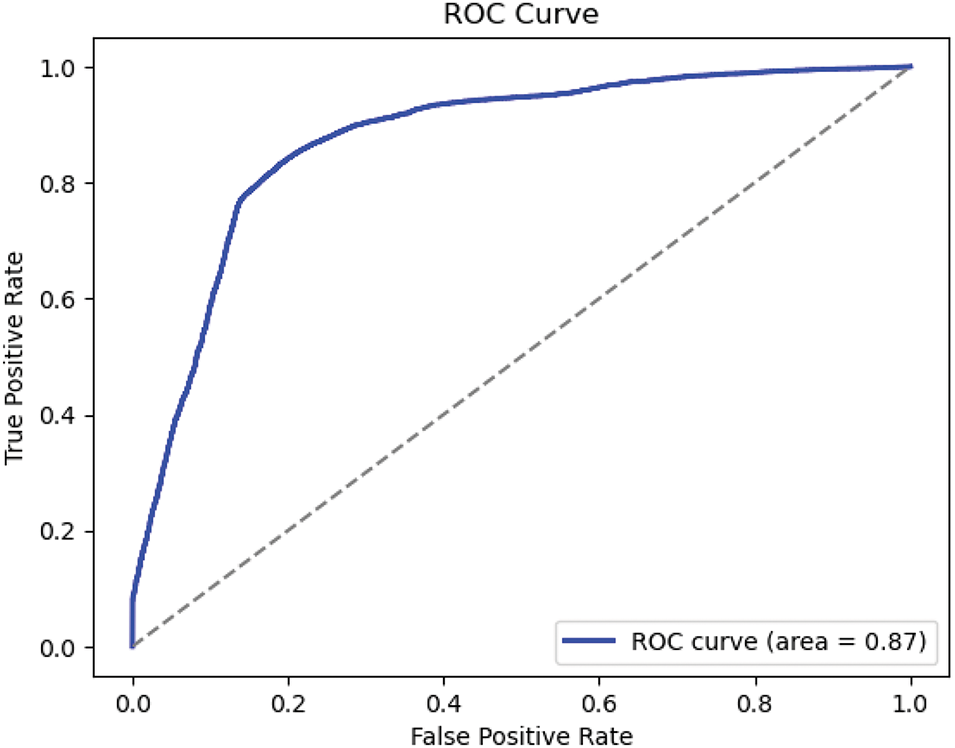

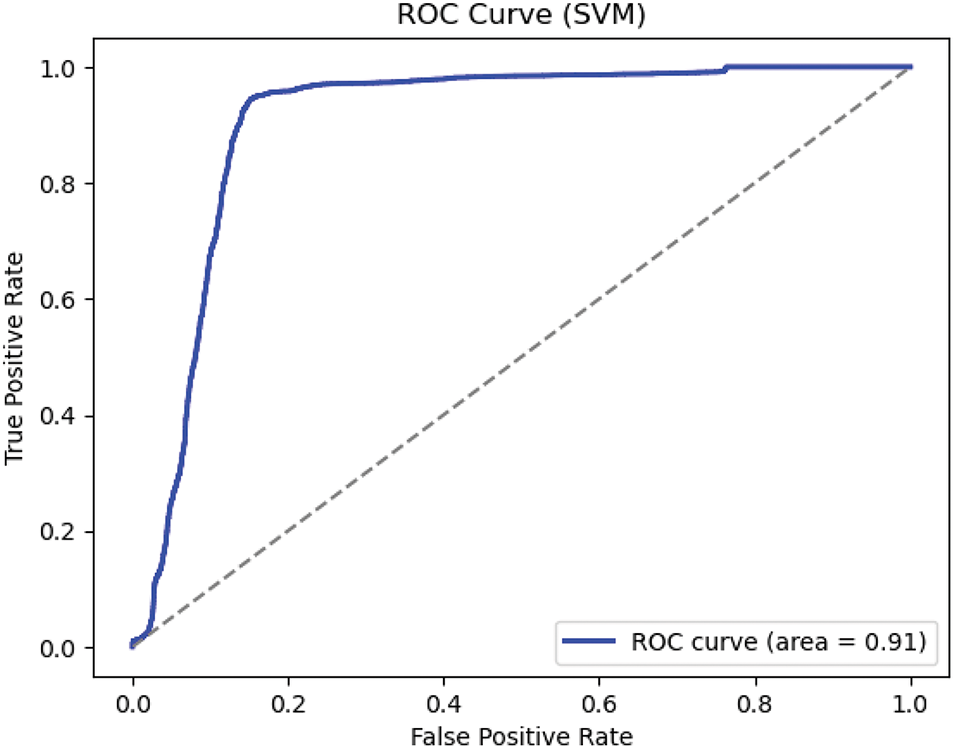

The ROC curve shown in Fig. 10 demonstrates the trade-off between the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the false positive rate across different classification thresholds. With an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of approximately

Figure 10: ROC of the model, indicating an AUC of

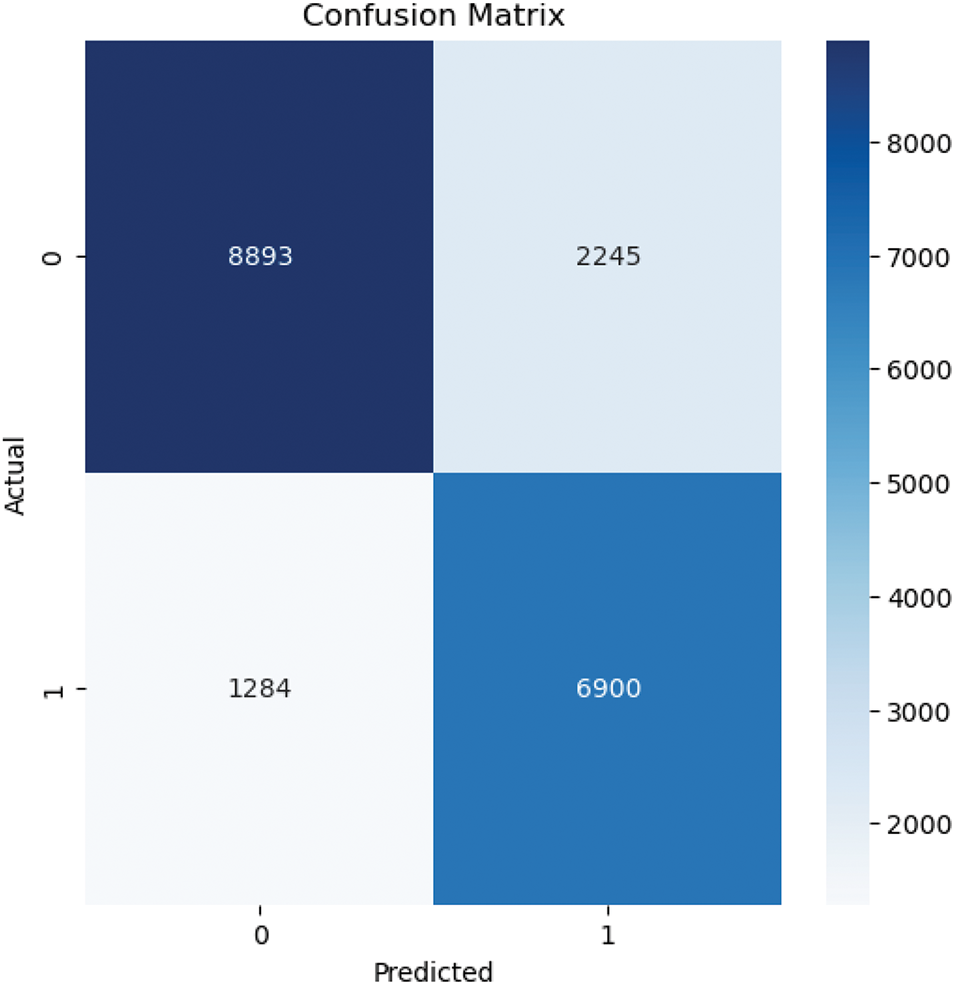

The confusion matrix in Fig. 11 provides further insight into the model’s classification performance. The model achieved a strong balance between true positives (

Figure 11: Confusion matrix showing the classification results of machine failure prediction

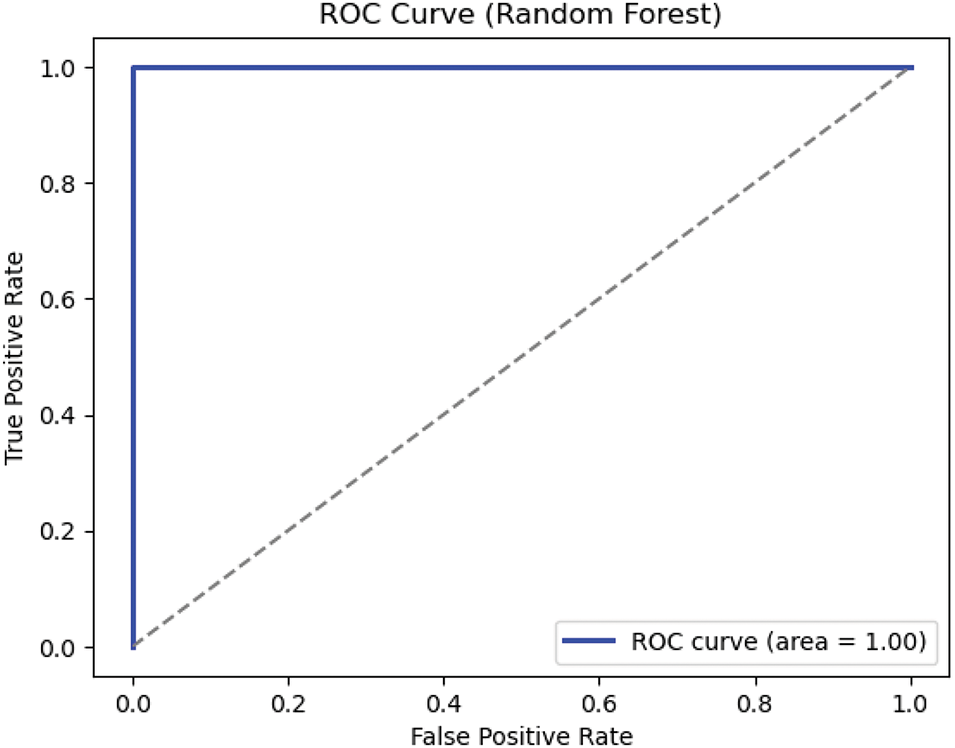

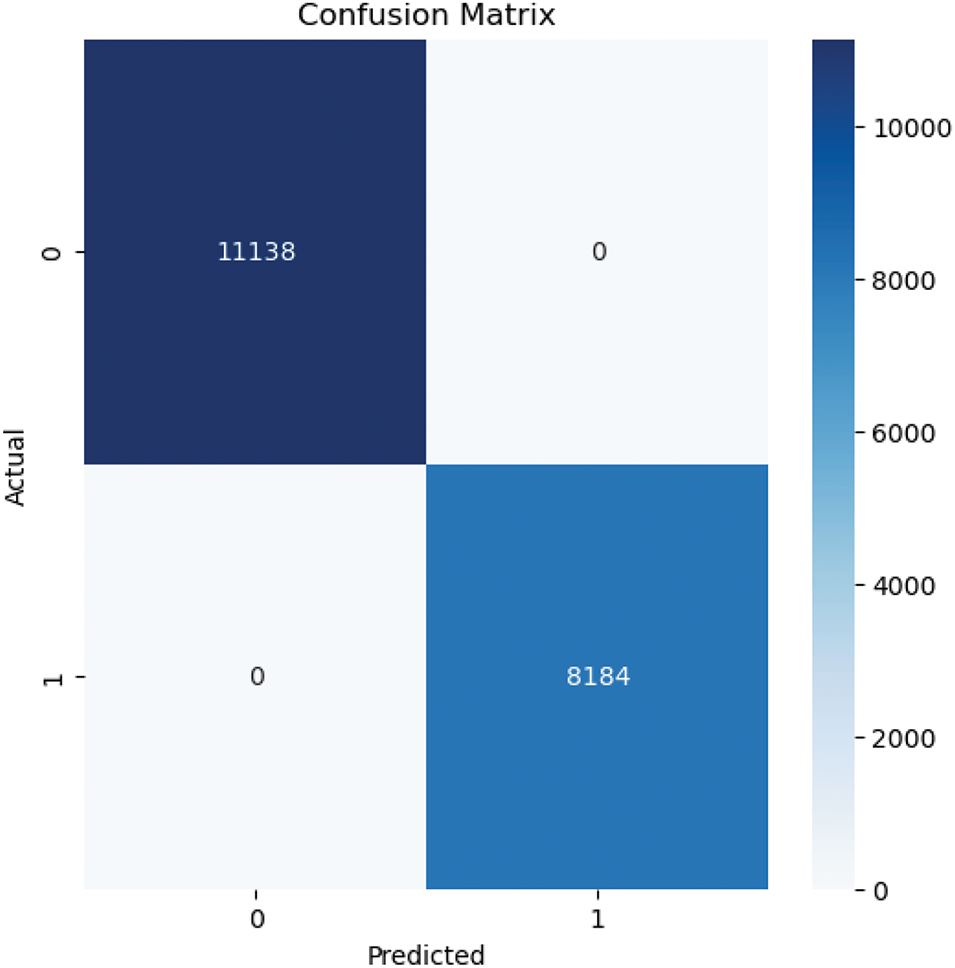

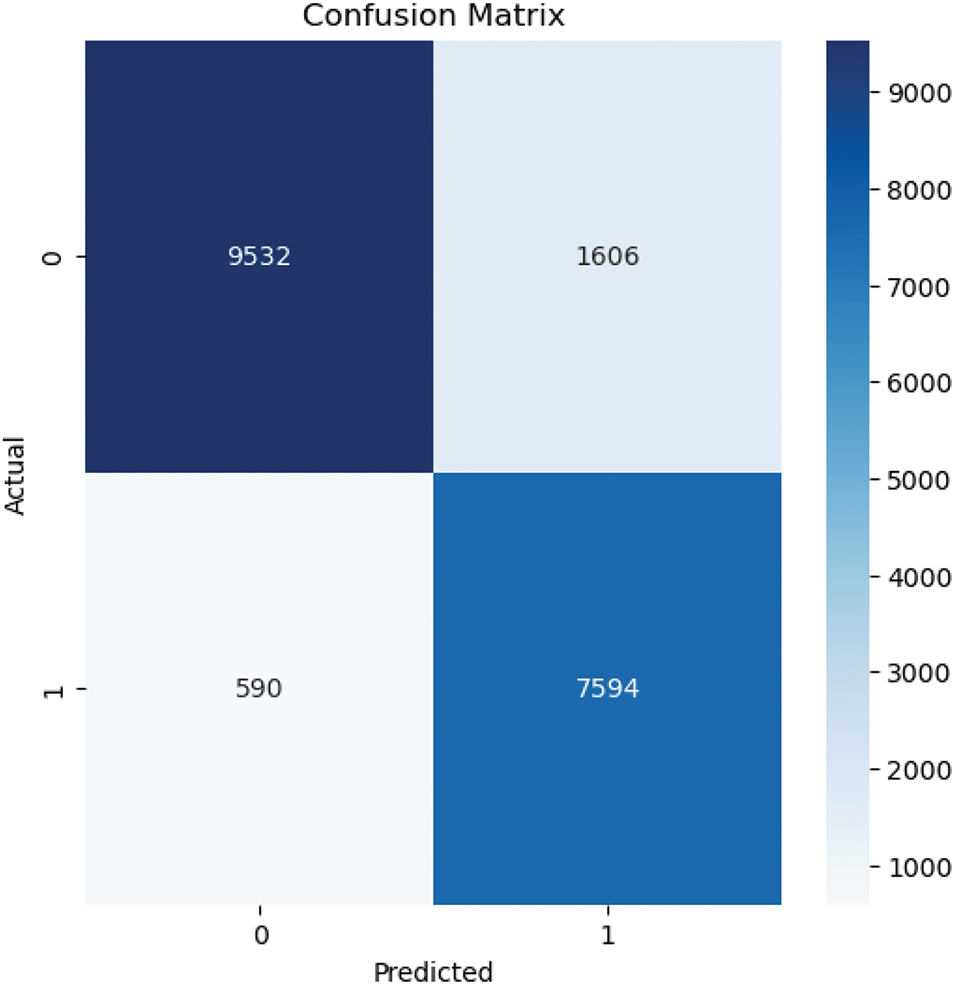

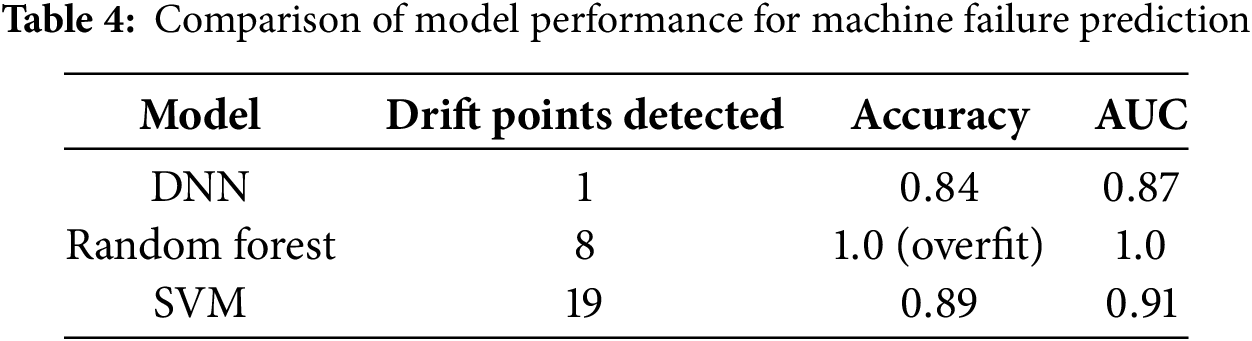

The DNN learner model is compared against two machine learning models, namely random forest and support vector machine, for comparison of performance. The Random Forest model achieved perfect classification results as shown in Figs. 12 and 13, with an AUC of

Figure 12: ROC Curve of the random forest

Figure 13: Confusion matrix of random forest

Figure 14: ROC curve of the SVM

Figure 15: Confusion matrix of SVM

The following Table 4 summarizes the comparison of the performance of the 3 models. The table infers that the Random Forest and SVM models performed highly in terms of classification accuracy and AUC scores; these models proved to be extremely sensitive to minor changes in the distribution evident from the number of drift points. If too many drift points are identified by the model, then it leads to redundant updates as a part of the retraining phase, thus not suitable for a non-stationary dynamic industrial environment. Comparatively, the DNN model provided a balanced performance of 84% classification accuracy and

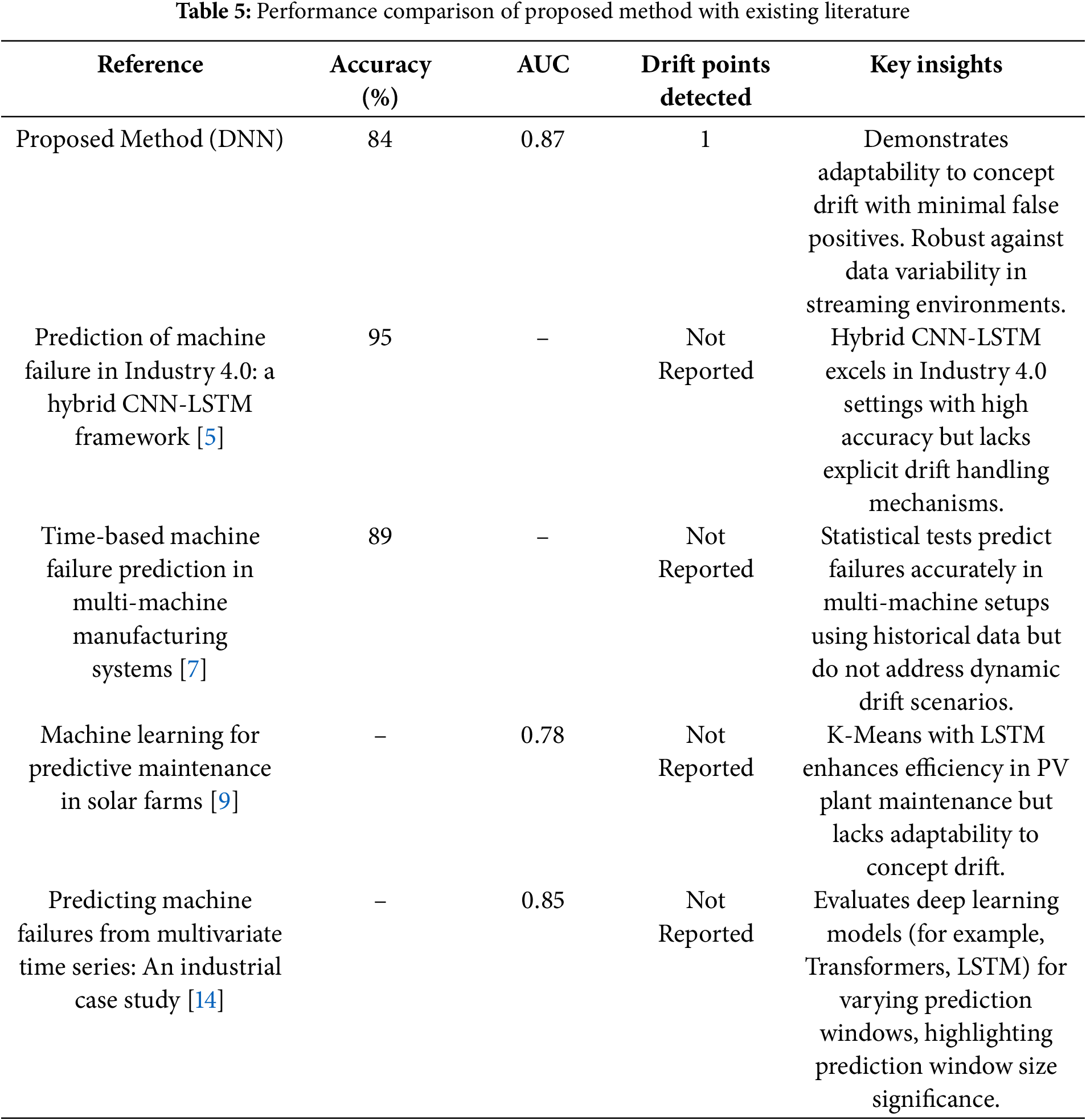

The performance of our presented model is compared against the recent works from the existing literature; the comparison is shown in Table 5. Though the usage of models like CNN-LSTM [5] achieves a higher accuracy of (95%), these models do not account for drifting environments, which is difficult to model as the literature reviewed models assume the environment is stationary. Similarly, semi-supervised clustering and statistical methods do favor the static environment and do not work so well in the dynamic environment where data is coming as a stream. Compared to these models, our proposed architecture is tuned to work in a non-stationary environment and thus adaptive in nature, which is evident from identifying the point at which model prediction degrades, inducing model decay by capturing drift points with a competitive accuracy of (

Overall, DNN’s superior performance can be attributed to its ability to capture complex, nonlinear patterns, greater adaptability to minor data fluctuations, and robustness in classification. This combination of traits makes DNNs particularly well suited for predictive maintenance tasks where complex interactions and evolving data distributions are common, as in the case of machine failure prediction. The DNN’s lower sensitivity to small anomalies and consistent performance across batches make it a more reliable model for this specific application compared to SVM and Random Forest. The experimental results demonstrate that the adaptive learner, with its ability to reset based on loss spikes, effectively handles concept drift and maintains strong predictive performance.

The research work introduced a novel incremental learning approach with drift detection and adaptation in the context of real-time mechanical failure detection. Unlike the conventional methods that assume that the learning environment is static, our presented model is resilient enough to work in a non-stationary dynamic environment as well as in static. Our approach also explores the horizon of balancing the dataset using SMOTE, with loss-based drift detection and minimal retraining as an adaptation strategy to ensure that it is a viable solution for predictive maintenance in dynamic industrial settings. The experimentation results indicate that both SVM and Random Forest algorithms, which are traditional machine learning approaches, excelled in terms of classification accuracy and AUC metrics, but their sensitivity to the smallest changes in the data distribution made them detect redundant drift points due to recurrent retraining in drift conditions, and minor anomalies made them less suitable for dynamic industrial environments. Contrary to it, the model DNN performed moderately in non-stationary settings and yielded 84% classification accuracy with an AUC of

Though the proposed architecture is resilient, the streaming batch-based input (incremental learning) for training and drift detection and adaptation induces delays in real-time streaming scenarios, which is the limitation of the presented work. Additionally, the focus on binary classification limits its applicability to more complex industrial failure scenarios. Future research should explore advanced drift detection methods, such as adaptive windowing and ensemble-based approaches, to enhance sensitivity to gradual or recurring drift patterns. Expanding the framework to accommodate multiclass or multi-label categorization will further improve its versatility across diverse industrial domains. Incorporating edge computing could enhance deployment by enabling low-latency, on-device drift detection in Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) settings. Furthermore, integrating automated model adjustment and retraining mechanisms in response to detected drifts would significantly improve the system’s adaptability and robustness.

Acknowledgement: The authors express their sincere gratitude to their respective institutions for providing the necessary resources and support to carry out this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Prashanth B. S and Manoj Kumar M. V.; methodology, Prashanth B. S; software, Prashanth B. S; validation, Prashanth B. S, Manoj Kumar M. V. and Nasser Almuraqab; formal analysis, Prashanth B. S; investigation, Prashanth B. S; resources, Manoj Kumar M. V.; data curation, Prashanth B. S; writing—original draft preparation, Prashanth B. S; writing—review and editing, Prashanth B. S and Puneetha B. H; visualization, Prashanth B. S; supervision, Manoj Kumar M. V.; project administration, Prashanth B. S; funding acquisition, Nasser Almuraqab. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Agrahari S, Srivastava S, Singh AK. Review on novelty detection in the non-stationary environment. Knowl Inform Syst. 2024;66(3):1549–74. doi:10.1007/s10115-023-02018-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hu Q, Gao Y, Cao B. Curiosity-driven class-incremental learning via adaptive sample selection. IEEE Transact Circ Syst Video Technol. 2022;32(12):8660–73. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2022.3196092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Babüroğlu ES, Durmuşoğlu A, Dereli T. Concept drift from 1980 to 2020: a comprehensive bibliometric analysis with future research insight. Evol Syst. 2024;15(3):789–809. doi:10.1007/s12530-023-09503-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bayram F, Ahmed BS, Kassler A. From concept drift to model degradation: an overview on performance-aware drift detectors. Knowl-Based Syst. 2022;245:108632. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.108632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wahid A, Breslin JG, Intizar MA. Prediction of machine failure in Industry 4.0: a hybrid CNN-LSTM framework. Appl Sci. 2022;12(9):4221. doi:10.3390/app12094221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zuo J, Zeitouni K, Taher Y. Incremental and adaptive feature exploration over time series stream. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2019; Los Angeles, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 593–602. [Google Scholar]

7. SobASzek Ł., GolA A, Świć A. Time-based machine failure prediction in multi-machine manufacturing systems. Eksploatacja I Niezawodność. 2020;22(1):52–62. doi:10.17531/ein.2020.1.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li H, Zhang Z, Li T, Si X. A review on physics-informed data-driven remaining useful life prediction: challenges and opportunities. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2024;209(18):111120. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2024.111120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Qureshi MS, Umar S, Nawaz MU. Machine learning for predictive maintenance in solar farms. Int J Adv Eng Technol Innovat. 2024;1(3):27–49. [Google Scholar]

10. Chen L, Liang Y, Yang Z, Dui H. Reliability analysis and preventive maintenance of rehabilitation robots. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2025;256:110704. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2024.110704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Beig Zali R, Latifi M, Javadi AA, Farmani R. Semisupervised clustering approach for pipe failure prediction with imbalanced data set. J Water Resour Plan Manag. 2024;150(2):04023078. doi:10.1061/JWRMD5.WRENG-6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zheng D, Wang J, Jing H, Ozbayoglu E, Silvio B, Jakaria M. Identifying the robust machine learning models to cement sheath fatigue failure prediction. In: ARMA US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium; 2024; Golden, CO, USA: ARMA. p. D042S058R006. [Google Scholar]

13. Hamaide V, Joassin D, Castin L, Glineur F. A two-level machine learning framework for predictive maintenance: comparison of learning formulations. arXiv:220410083. 2022. [Google Scholar]

14. Pinciroli Vago NO, Forbicini F, Fraternali P. Predicting machine failures from multivariate time series: an industrial case study. Machines. 2024;12(6):357. doi:10.3390/machines12060357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Talmoudi S, Kanada T, Hirata Y. Tracking and visualizing signs of degradation for early failure prediction of rolling bearings. J Robot Mechatr. 2021;33(3):629–42. doi:10.20965/jrm.2021.p0629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Park J, Kang M, Han B. Class-incremental learning for action recognition in videos. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021;Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 13698–707. [Google Scholar]

17. Hinder F, Artelt A, Hammer B. Towards non-parametric drift detection via dynamic adapting window independence drift detection (DAWIDD). In: International Conference on Machine Learning; 2020; Virtual Conference (originally planned for Vienna, AustriaPMLR. p. 4249–59. [Google Scholar]

18. Wang FY, Zhou DW, Ye HJ, Zhan DC. Foster: feature boosting and compression for class-incremental learning. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2022; Tel Aviv, Israel: Springer. p. 398–414. [Google Scholar]

19. De Lange M, Tuytelaars T. Continual prototype evolution: learning online from non-stationary data streams. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 8250–9. [Google Scholar]

20. Chen W, Liu Y, Pu N, Wang W, Liu L, Lew MS. Feature estimations based correlation distillation for incremental image retrieval. IEEE Transact Multim. 2021;24:1844–56. doi:10.1109/TMM.2021.3073279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Menezes AG, de Moura G, Alves C, de Carvalho AC. Continual object detection: a review of definitions, strategies, and challenges. Neur Netw. 2023;161(3):476–93. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.01.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zheng X, Li P, Chu Z, Hu X. A survey on multi-label data stream classification. IEEE Access. 2019;8:1249–75. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2962059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu W, Zhu C, Ding Z, Zhang H, Liu Q. Multiclass imbalanced and concept drift network traffic classification framework based on online active learning. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;117:105607. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mundt M, Hong Y, Pliushch I, Ramesh V. A wholistic view of continual learning with deep neural networks: forgotten lessons and the bridge to active and open world learning. Neu Netw. 2023;160(2):306–36. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yang X, Hu X, Zhou S, Liu X, Zhu E. Interpolation-based contrastive learning for few-label semi-supervised learning. IEEE Transacti Neu Netw Learn Syst. 2022;35(2):2054–65. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3186512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Matzka S. AI4I 2020 predictive maintenance dataset. UCI Machine Learning Repository. 2020. doi:10.24432/C5HS5C.448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou DW, Ye HJ, Zhan DC. Co-transport for class-incremental learning. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2021; Chengdu, China. p. 1645–54. [Google Scholar]

28. Korycki Ł, Krawczyk B. Concept drift detection from multi-class imbalanced data streams. In: 2021 IEEE 37th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE); 2021; Virtual Conference (originally planned for Chania, GreeceIEEE. p. 1068–79. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools