Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Smart Contract-Aided Attribute-Based Signature Algorithm with Non-Monotonic Access Structures

1 Department of Electronic Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China

2 School of Cyberspace Security, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, 100876, China

* Corresponding Author: Xin Xu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 5019-5035. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.061046

Received 15 November 2024; Accepted 06 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

Attribute-Based Signature (ABS) is a powerful cryptographic primitive that enables fine-grained access control in distributed systems. However, its high computational cost makes it unsuitable for resource-constrained environments, and traditional monotonic access structures are inadequate for handling increasingly complex access policies. In this paper, we propose a novel smart contract-assisted ABS (SC-ABS) algorithm that supports non-monotonic access structures, aiming to reduce client computing overhead while providing more expressive and flexible access control. The SC-ABS scheme extends the monotonic access structure by introducing the concept of negative attributes, allowing for more complex and dynamic access policies. By utilizing smart contracts, the algorithm supports distributed trusted assisted computation, and the computation code is transparent and auditable. Importantly, this design allows information about user attributes to be deployed on smart contracts for computation, both reducing the risk of privacy abuse by semi-honest servers and preventing malicious users from attribute concealment to forge signatures. We prove that SC-ABS satisfies unforgeability and anonymity under a random oracle model, and test the scheme’s cost. Compared with existing schemes, this scheme has higher efficiency in client signature and authentication. This scheme reduces the computing burden of users, and the design of smart contracts improves the security of aided computing further, solves the problem of attribute concealment, and expresses a more flexible access structure. The solution enables permission control applications in resource-constrained distributed scenarios, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and distributed version control systems, where data security and flexible access control are critical.Keywords

With the growth of information technology, distributed file systems and information management have become essential components of modern data management. Systems like Git, vehicle networking, and the Internet of Things (IoT) require efficient data sharing and collaboration while ensuring information security and privacy. These systems face complex access control challenges. Traditional public key encryption, relying on certificates and key maintenance, is insufficient for addressing access control needs in distributed environments.

Attribute-based cryptography (ABC), including Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE) and Attribute-Based Signatures (ABS) [1], offers a novel solution for access control in distributed file systems by using attributes to define access policies. Xu et al. [2] proposed an access control scheme using ABE and ABS for read-write permissions on distributed version control systems. Hong et al. [3] proposed an attribute-based online/offline signature scheme for mobile crowdsensing scenarios. Li et al. [4] and Patil et al. [5] proposed an access control scheme based on ABC for electronic health records. In the above application scenarios, ABS is often used to verify or manage permissions, especially for writing. In this framework, users’ signing keys are linked to their attributes, and signatures are associated with specific access policies. Only entities whose attributes meet predefined conditions can generate valid signatures. This simplifies key distribution, reduces maintenance costs, and enhances flexibility, making it ideal for distributed environments.

In practical applications, several challenges hinder the effectiveness of existing solutions. Most ABS implementations rely on monotonic access structures, limiting their ability to express complex access control logic. Compared to traditional access control lists (ACL), ABS struggles to offer fine-grained revocation or permission adjustments at the individual attribute or user level. To better align with real-world needs, ABS must support non-monotonic access policies, such as AND, OR, NOT, and Threshold gates. These enhancements would improve policy expressiveness and enable more precise permission management, such as “Faculty AND Accounting AND (non-math department)”. However, extending monotonic ABS to non-monotonic schemes is challenging. In non-monotonic designs, user key attributes are often independent, allowing malicious users to forge signatures by concealing certain attributes(such as “math department”), which poses a security risk. We refer to this type of forgery as “attribute concealment.” Okamoto et al. propose an ABS supporting non-monotonic structures [6]. To avoid attribute concealment, the scheme requires that the key must contain information about all attributes in the attribute space, but its low verification efficiency makes it impractical.

This also highlights another critical challenge faced by ABS: ABS algorithms typically involve complex bilinear pairing operations, which pose significant challenges for resource-constrained devices. The introduction of non-monotonic access structures further increases this computational burden, conflicting with the lightweight computing demands of IoT devices. To address this, researchers have explored server-aided mechanisms [7–11] where remote servers take on most of the computational tasks. However, this approach raises new concerns about server trustworthiness. Although server assistance can reduce client-side computational load, it also introduces security and trust issues, as users must trust that servers will not leak sensitive information or tamper with computation results. Additionally, the trustworthiness of servers hinders the delegation of attribute-related computations in ABS. If the server is responsible for verifying the correctness of user attributes, it introduces the risk of compromising user attribute privacy, making challenges like attribute concealment difficult to address. Thus, the trust issue with external servers and the forgery risk of non-monotonic access structures present conflicting problems.

Therefore, developing ABS algorithms that support non-monotonic access policies while maintaining efficiency is an urgent research topic. This paper proposes a smart contract-aided ABS scheme (SC-ABS) that supports non-monotonic access policies, effectively addressing the conflict between server trust issues and attribute concealment. Our contributions are outlined below:

1. We present a new attribute-based signature scheme that supports non-monotonic access structures on attributes. Our scheme can handle any access structure that can be represented by a boolean formula involving AND, OR, NOT, and threshold operations.

2. Our scheme introduces a smart contract-aided computation mechanism in which the computation program is transparently recorded on the blockchain and automatically executed upon meeting predefined conditions. This ensures the security of intermediate results. Compared to traditional server-aided schemes, this approach is secure against collusion attacks and simultaneously reduces computational overhead for users.

3. We implemented SC-ABS, then tested its computational overhead and compared it with other server-assisted ABS algorithms. Additionally, we conducted a comprehensive security analysis. SC-ABS is more suitable for data security protection and permission control in the distributed scenario of limited resources.

Attribute-based signatures (ABS), first proposed in [1], ensure that only entities whose attributes satisfy the access policy can generate valid signatures. The most widely used existing ABS schemes are monotonic access structures such as the schemes of Maji et al. [1,12]. Okamoto et al. [6] present a fully secure ABS scheme in the standard model that supports general non-monotonic predicates. However, this scheme requires a fixed classification for attributes, and users must possess all attribute types, resulting in low efficiency due to the need for multiple bilinear pairings, making it impractical.

The computational overhead of ABS is a significant barrier to its widespread use. To address this, several server-aided ABS schemes have been proposed. Cui et al. [7] introduced server-aided ABS, transferring the signature and verification work to the server to reduce overhead. However, Xiong et al. [13] demonstrated that Cui et al.’s scheme lacks collusion security, and their scheme had correctness issues. Huang et al. [8] proposed a secure server-aided ABS that meets stronger security definitions. Chen et al. [9] used an access tree structure and delegated verification to the server, while Li et al.’s scheme [10] only supports threshold-based access strategies. These server-aided ABS schemes typically face server trust issues and do not support non-monotonic access policies.

ABS supporting non-monotonic access structures offers more expressive access control strategies, but it also incurs high computational overhead and poses a risk of attribute concealment. Current server-aided ABS are limited by server trust and struggle to address attribute concealment. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a smart contract-based trusted aided ABS algorithm that incorporates a non-monotonic access structure.

Smart contracts, introduced by Nick Szabo in 1994, are “computerized transaction protocols that execute the terms of a contract” [14]. They aim to fulfill common contractual conditions without the need for intermediaries [14,15]. Smart contracts are facilitated by blockchain platforms like Ethereum. The scheme presented in this paper leverages Ethereum [16] for the design and deployment of smart contracts aimed at assisted computing. As a widely deployed blockchain, Ethereum enables developers to create smart contracts using languages like Solidity and Vyper, compile them, and deploy them. To deploy a smart contract, the owner initiates a transaction, creating a contract account. Any Ethereum account interacts with the smart contract through the contract account. When an Ethereum account invokes a function to update data stored on the Ethereum network, it submits a corresponding transaction, which is recorded on the Ethereum network.

Advantages of Smart Contract Assistance. Smart contracts aided ABS is different from server-aided ABS, and blockchain-based smart contracts have more advantages than traditional third-party servers.

• Distributed services: Smart contracts, deployed on the blockchain, provide distributed and decentralized services, mitigating the single point of failure risk faced by traditional third-party servers.

• Reliability: Once issued, a smart contract cannot be tampered with. It is automatically executed when conditions are met, and no party can alter the result. Multiple independent nodes process and verify the contract logic, effectively preventing manipulation and ensuring timely execution according to specified terms. This makes smart contract results more reliable than those from traditional servers.

• Security: Smart contracts function as digital protocols, with open and transparent logic that can be reviewed by all users. As long as the code logic is correct, the stored information cannot be maliciously exploited, and the contract cannot perform actions outside the agreement, such as colluding with malicious users. In comparison to traditional third-party servers, smart contracts offer greater security for aided services.

First, we provide the definition of an access structure. Then we give background information on bilinear maps and our cryptographic assumption. Finally, we give some background on linear secret-sharing schemes.

Definition 1: Access Structure [17]: Let

The ABS algorithms use the idea of bilinear pairs based on elliptic curves. Let

1. Bilinearity:

2. Non-degeneracy:

The security model is defined as a game between a polynomial-time adversary A and a challenger C, where the challenger C interacts with a smart contract to perform its operations.

Setup: Adversary A allocates the target attribute set

Query: The adversary A adaptively issues the following query to C.

• Key extraction query: The adversary A selects the access policy

• Signature query: The adversary A selects a message

• User signature verification query: The adversary A has the signature

Signature forgery: A generates a forged signature

• A sends

• Adversary A has never issued a signature query for message

3.3 Linear Secret-Sharing Schemes

First, we introduce the design of a non-monotonic access policy based on the Linear Secret-Sharing Scheme (LSSS).

Definition 2: Linear Secret-Sharing Schemes [18]: Let

Non-Monotonic Access Structures. We refer to the method proposed by [18] to transform the monotonic access policy into a non-monotonic access policy. Assume a linear secret-sharing scheme family

Definition 3: non-monotonic access policy family

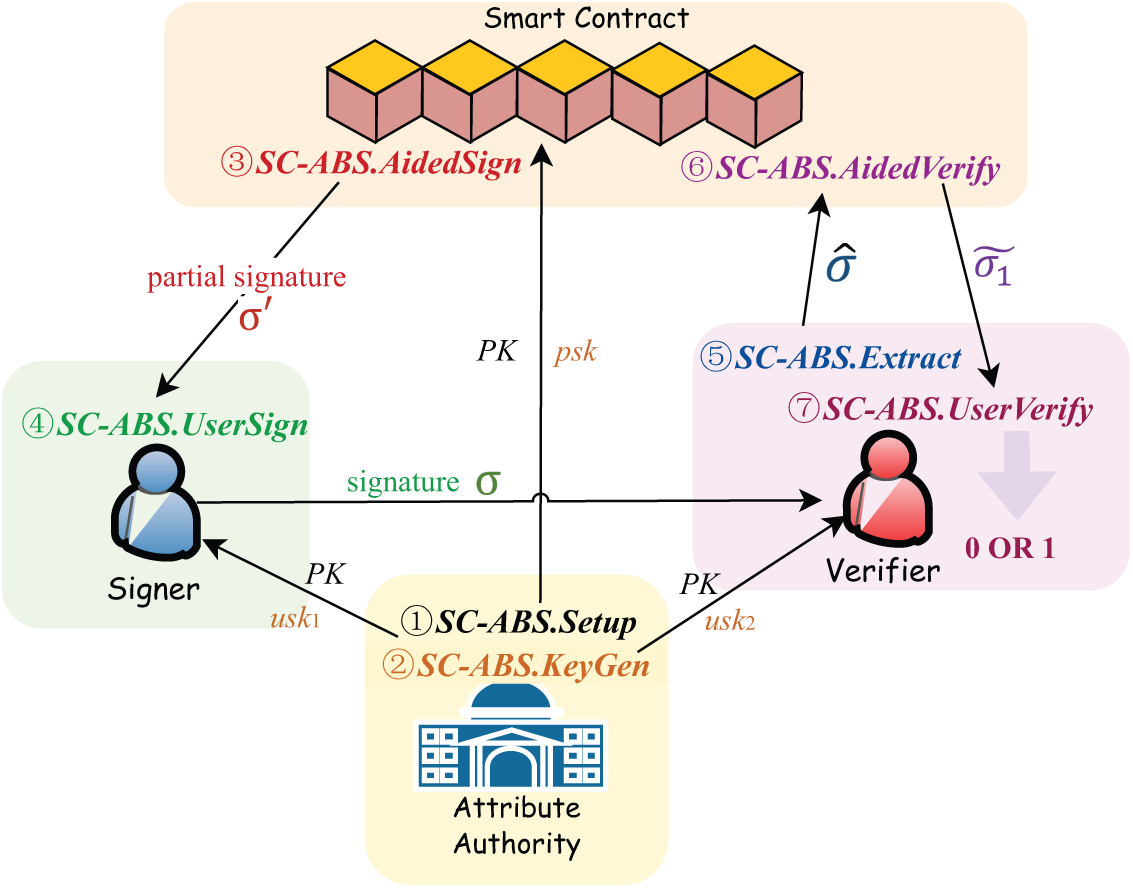

We designed a smart contract-aided attribute-based signature algorithm with non-monotonic access structures (SC-ABS). The algorithm involves three entities: attribute authorities, smart contracts, and users. As shown in Fig. 1, the attribute authority is responsible for key initialization and issuance, while the smart contract assists with calculations that users can sign and verify as needed. Compared to traditional ABS, our algorithm supports non-monotonic access strategies. Additionally, it introduces smart contracts as trusted, autonomous computing agents that execute programs automatically upon invocation, thereby eliminating the need for third-party involvement.

Figure 1: Algorithm framework of SC-ABS

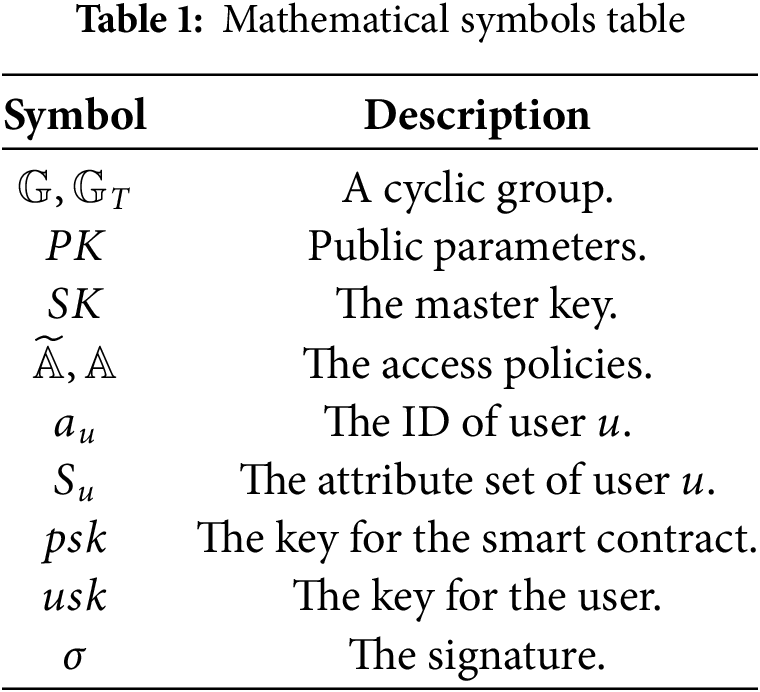

As shown in the Fig. 1, referring to Xiong et al., we designed the SC-ABS algorithm as follows, of which the meaning of symbols is shown in Table 1:

SC-ABS.Setup(

1. Select the multiplicative cyclic group

2. Randomly select

3. Set the attribute universe

4. Randomly select

Then, the system’s public parameters are denoted as

SC-ABS.KeyGen(

1. The non-monotonic access policy

2. Randomly select

3. For each row

4. Compute

5. Similarly, calculate

Then, based on the linear secret-sharing scheme

SC-ABS.AidedSign(

1. Confirm whether the attribute set

2. Randomly select

Then the partial signature generated by the smart contract for the signer

SC-ABS.UserSign(

Finally, the user gets the signature of message

SC-ABS.Extract(

SC-ABS.AidedVerify(

The smart contract returns

SC-ABS.UserVerify(

Determine whether

In SC-ABS, the smart contract is responsible for the auxiliary calculation of signature and verification. After completing the local calculation, the user initiates a calculation request to the smart contract in the form of publishing a transaction, and the smart contract verifies the user identity, performs the calculation, and returns the calculation result.

Theorem 1: SC-ABS is correct if for all

Proof Proving the correctness of SC-ABS requires showing the equivalence between

Therefore, we can deduce:

For

Therefore,

This section is the analysis of SC-ABS security. We will analyze the security of the algorithm and smart contracts.

5.1 Unforgeability and Anonymity

We refer to Waters et al.’s [20] definitions and demonstrate in the appendix that SC-ABS satisfies unforgeability and anonymity under the random oracle model.

In SC-ABS, the smart contract manages aided signing and verification. During signing, the signer initiates a transaction, and the smart contract determines their attribute information based on the account, enhancing security. SC-ABS relies not only on the difficulty of bilinear pairing problems but also on the trustworthiness of the smart contract. During aided signing, when an adversary requests a signature, the challenger provides the attribute set and signature for the message. However, users cannot specify their attributes in the smart contract signing phase; it strictly adheres to the rules and uses the set linked to the user’s account. Therefore, as long as the user’s account is secure, attackers cannot query a signature for any attribute set.

By introducing the smart contract, the computational process can be transparently displayed on the blockchain, and all user transactions are immutable. This ensures that the entire SC-ABS system is auditable and traceable. Additionally, implementing an audit penalty mechanism in practice can effectively raise the cost of malicious attacks.

This section will focus on analyzing the security of the data stored in the smart contract on the blockchain, specifically addressing the variables security, the intermediate results security, and collusion security.

Data Stored by Smart Contracts. The data stored by the smart contract on the blockchain can be classified into two categories:

1. Variables in the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) environment: public parameters

2. Transactions on the blockchain: intermediate results generated by the smart contract, namely partial signature

For the stored variables,

5.2.2 Intermediate Result Security

The intermediate result generated by the smart contract contains a partial signature

1. Man-in-the-middle attack: Suppose there is a middleman

2. Replay attack: Assume that user

Since

5.2.3 Collusion Security Analysis

In SC-ABS, collusion attacks among multiple users occur when users with attribute sets that don’t satisfy the access policy try to generate valid signatures by combining their signature keys. Since the full signature is generated from partial signatures that contain attributes of the user, conspirators must merge their partial signatures. The

In collusion attacks between signers and smart contracts, all transactions are stored on the blockchain, ensuring that intermediate signatures and aided verification results are auditable and non-repudiable. Smart contracts issued by trusted attribute authorities are deployed as open, transparent programs on the blockchain, executing automatically when specific conditions are met. Unlike third-party servers with opaque logic, participants can review the code’s logic and security, significantly reducing the risk of malicious behavior. A correct smart contract generates intermediate signatures only based on the attribute set associated with the user account that initiated the request. In the signature verification algorithm, the smart contract cannot access the message

In summary, the use of smart contracts for aided computation is secure against collusion attacks. Additionally, the information stored on the blockchain is secure under the design of this solution, effectively protecting against privacy threats.

In this section, we conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the SC-ABS scheme. This includes analyzing its storage, computing, and communication overhead; comparing its computing overhead with that of other server-assisted ABS algorithms; and performing a functional comparison with related algorithms.

We implemented the SC-ABS algorithm based on the PBC (Pairing-Based Cryptography) library, and our experiments were conducted using C on a system with an Intel Core CPU (1.60 GHz, 2 GB RAM). We tested the computing time overhead of the smart contract and the client respectively. We set the size of the attribute space to 10 and the number of attributes involved in the access policy to 5, for a total of 100 times. The average time of smart contract-aided signature is 0.0082 s, the average time of user signature is 0.0044 s, the average time of smart contract-aided verification is 0.0034 s, and the average time of user signature extraction and verification is 0.006 s, which the verification time is 0.0012 s.

Let

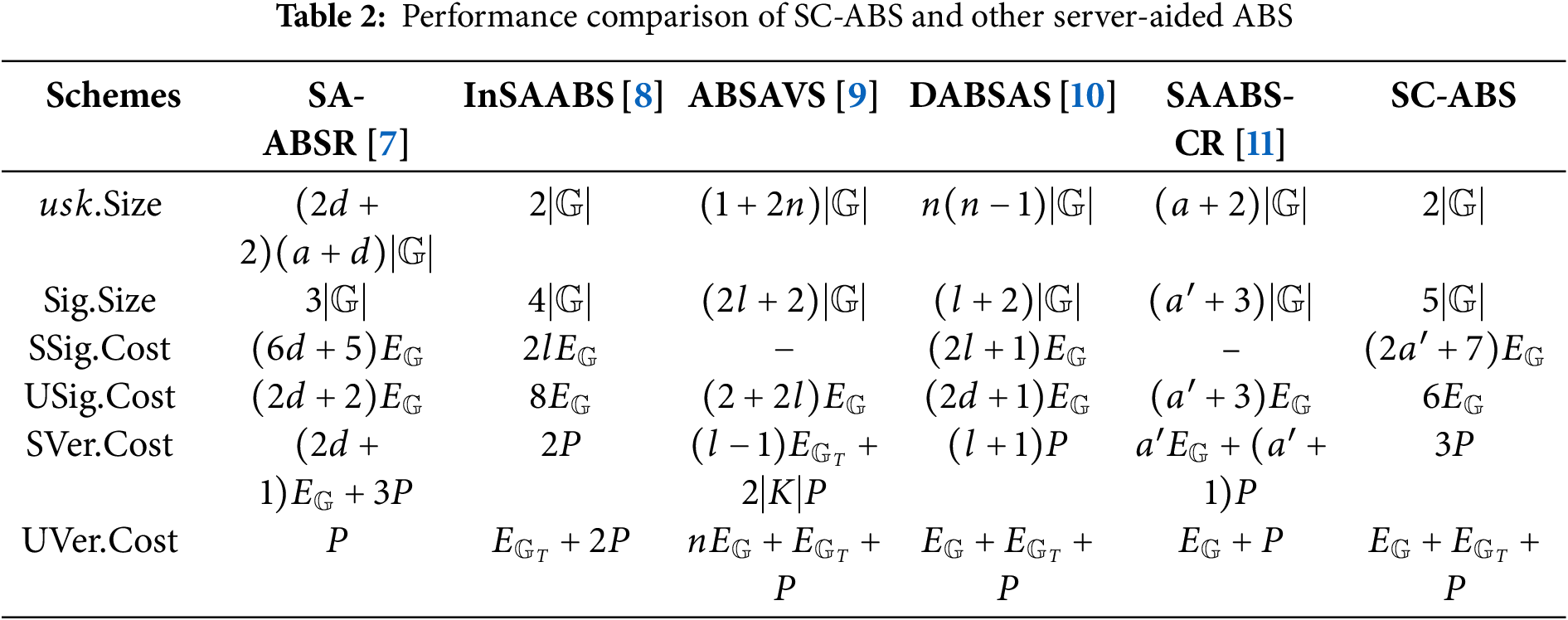

As shown in Table 2, we compare our SC-ABS scheme with other 5 server-aided attribute-based signature (SAABS) schemes [7–11]. Compared to other SAABS, SC-ABS features the shortest user secret key length and incurs the least user-end signing cost. The aided verification cost is also minimal, involving just one additional pairing operation compared to the two pairings of SA-ABSR [7]. Moreover, the user-end verification cost is comparable to that of most SAABS schemes. For aided signing costs, when

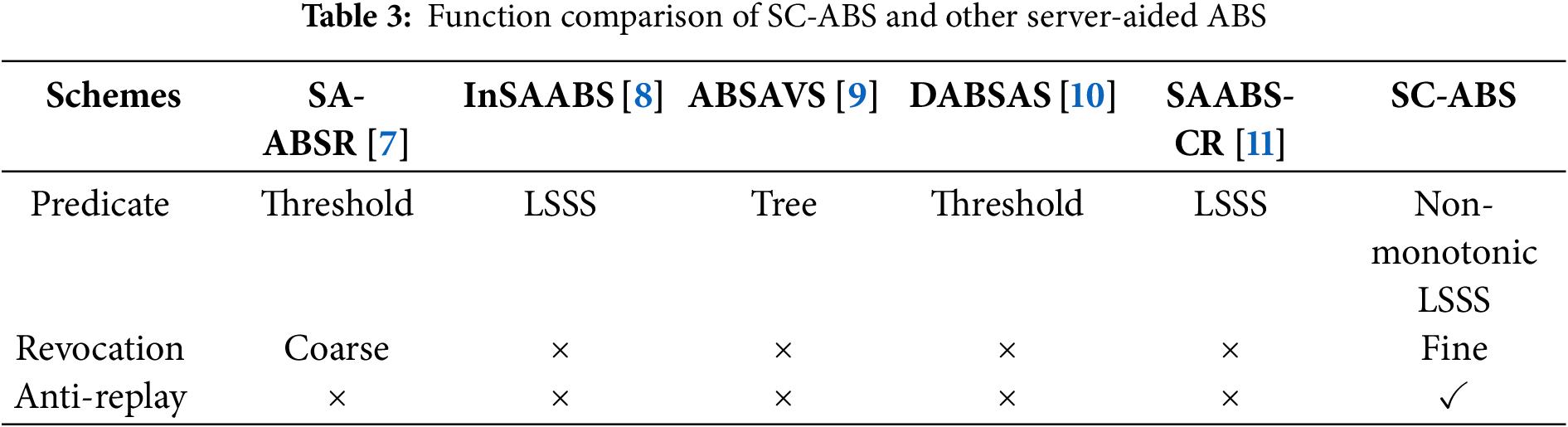

We also compared the security features of the above six schemes, as shown in Table 3. Only SC-ABS employs the most expressive non-monotonic LSSS access structure, which supports both fine-grained attribute revocation and replay resistance. While SA-ABSR supports coarse-grained attribute revocation, it is vulnerable to collusion attacks; InSAABS and SAABS-CR utilize more expressive LSSS access structures but do not support revocation functionality. The other five SAABS fail to protect against malicious user replay attacks on signatures in distributed systems (such as Git). Therefore, compared with other SAABS, SC-ABS supports a richer set of security features without increasing computational overhead, making it better suited for the requirements of distributed systems.

In this paper, we propose a smart contract-aided ABS scheme that supports a non-monotonic access structure. We use negative attributes to extend the monotonic access structure to the non-monotonic access structure. Based on the distributed and reliable characteristics of smart contracts, we perform auxiliary computations to reduce the computing cost of users and prevent users from forging signatures by attribute concealment. We prove that SC-ABS satisfies unforgeability and anonymity under a random oracle model, and evaluate its computational performance. Experimental results show that compared with other server-assisted schemes, our scheme can improve security and reduce the computing cost of the client.

In the future, we plan to apply this solution to popular distributed file systems such as Git and design fine-grained user permission granting and revocation schemes based on this approach. The proposed scheme will require users to have closer interactions with blockchain technology. However, it is also essential to consider whether the introduction of smart contracts might introduce additional security risks and overheads. Evaluating and mitigating these potential issues will be a key focus of our further research.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors wish to thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that improved this paper.

Funding Statement: The specific funding Grant Number is No. 82090053.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xin Xu, Zhen Yang; analysis and interpretation of results: Xin Xu; draft manuscript preparation: Xin Xu, Yongfeng Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Xin Xu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A SC-ABS Security Proofs: We analyze the security of the SC-ABS algorithm. The security analysis of the ABS algorithm usually includes two points: unforgeability and anonymity.

Appendix A.1 Unforgeability

Unforgeability means that a valid signature can only be generated using a partial signing key and the corresponding user signing key.

Theorem A1: If there exists a polynomial-time adversary A that wins the above game with non-negligible probability

Proof: Assuming that under the polynomial time algorithm A can destroy the proposed solution with a non-negligible probability

Initialization: Challenger C manages an attribute domain

According to the security proof of [20], we define the following function for each message:

According to the above function, for a message

where

Query: Adversary A issues the following query to challenger C:

• Key extraction query: Suppose there is an access policy

– If

– If

Set

For the additional attribute

• Signature query Adversary A selects message

– If

– If

Finally, for the signature query of message

• User signature verification query: The adversary A has the signature

The challenger computes

Signature forgery: The adversary A forges the signature of the message

The challenger can then calculate:

If the challenger can calculate

1.

2.

In addition, define an event

□

Appendix A.2 Anonymity

Anonymity refers to: assuming there are two signatures

Among them, there are

References

1. Maji H, Prabhakaran M, Rosulek M. Attribute-based signatures: achieving attribute-privacy and collusion-resistance. Cryptology ePrint Archive; 2008 [cited 2025 Feb 28]. Available from: http://eprint.iacr.org/2008/328. [Google Scholar]

2. Xu X, Cai Q, Lin J, Pan S, Ren L. Enforcing access control in distributed version control systems. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME) 2019; 2019 Jul 8–12; Shanghai, China. New York, NY, USA: IEEE. 2019. p. 772–7. doi:10.1109/ICME.2019.00138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hong H, Hu B, Sun Z. An efficient and secure attribute-based online/offline signature scheme for mobile crowdsensing. Hum-Cent Comput Inf Sci. 2021;11:26. doi:10.22967/HCIS.2021.11.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li X, Wang H, Ma S, Xiao M, Huang Q. Revocable and verifiable weighted attribute-based encryption with collaborative access for electronic health record in cloud. Cybersecurity. 2024;7(1):1–19. doi:10.1186/s42400-024-00211-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Patil RY. A secure privacy preserving and access control scheme for medical internet of things (MIoT) using attribute-based signcryption. Int J Inf Technol. 2024;16(1):181–91. doi:10.1007/s41870-023-01569-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Okamoto T, Takashima K. Efficient attribute-based signatures for non-monotone predicates in the standard model. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2014;2(4):409–21. doi:10.1109/TCC.2014.2353053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cui H, Deng RH, Liu JK, Yi X, Li Y. Server-aided attribute-based signature with revocation for resource-constrained industrial-internet-of-things devices. IEEE Trans Industr Inform. 2018;14(8):3724–32. doi:10.1109/TII.2018.2813304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang Z, Lin Z. Secure server-aided attribute-based signature with perfect anonymity for cloud-assisted systems. J Inf Secur Appl. 2022;65(1):103066. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen Y, Li J, Liu C, Han J, Zhang Y, Yi P. Efficient attribute based server-aided verification signature. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;15(6):3224–32. doi:10.1109/TSC.2021.3096420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li J, Chen Y, Han J, Liu C, Zhang Y, Wang H. Decentralized attribute-based server-aid signature in the internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(6):4573–83. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen B, Xiang T, Li X, Zhang M, He D. Efficient attribute-based signature with collusion resistance for internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2023;72(6):7844–56. doi:10.1109/TVT.2023.3240824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Maji HK, Prabhakaran M, Rosulek M. Attribute-based signatures. In: Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference; 2011; Berlin, Germany: Springer. p. 376–92. [Google Scholar]

13. Xiong H, Bao Y, Nie X, Asoor YI. Server-aided attribute-based signature supporting expressive access structures for industrial internet of things. IEEE Trans Indust Inform. 2019;16(2):1013–23. doi:10.1109/TII.2019.2921516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. SZABO N. Smart contracts; 1994 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://nakamotoinstitute.org/library/smart-contracts/. [Google Scholar]

15. Christidis K, Devetsikiotis M. Blockchains and smart contracts for the internet of things. IEEE Access. 2016;4:2292–303. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2016.2566339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wood G et al. Ethereum: a secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger. Ethereum Project Yellow Paper. 2014;151:1–32. [Google Scholar]

17. Bethencourt J, Sahai A, Waters B. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption. In: 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP’07); 2007;Oakland, CA, USA. Washington, DC, USA: IEEE Computer Society. p. 321–34. doi:10.1109/SP.2007.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ostrovsky R, Sahai A, Waters B. Attribute-based encryption with non-monotonic access structures. In: Proceeding of the 2007 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS 2007; 2007 Oct 28–31; Alexandria, VA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2007. p. 195–203. doi:10.1145/1315245.1315270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Goyal V, Kothapalli A, Masserova E, Parno B, Song Y. Storing and retrieving secrets on a blockchain. In: IACR International Conference on Public-Key Cryptography; 2022 Mar 8–11; Virtual Event. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. Vol. 13177, p. 252–82. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-97121-2_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Waters B. Efficient identity-based encryption without random oracles. In: Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2005 May 22–26; Aarhus, Denmark. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2005. Vol. 3494, p. 114–27. doi:10.1007/11426639_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools