Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Digital Twins in the IIoT: Current Practices and Future Directions Toward Industry 5.0

1 Computer & Network Engineering, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, 15551, United Arab Emirates

2 Big Data Analytics Centre, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, 15551, United Arab Emirates

3 Department of Business Information Technology, Liwa College, Abu Dhabi, 41009, United Arab Emirates

4 Information System & Security, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, 15551, United Arab Emirates

* Corresponding Author: Mohammad Hayajneh. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 3675-3712. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.061411

Received 24 November 2024; Accepted 11 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

In this paper, we explore the ever-changing field of Digital Twins (DT) in the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) context, emphasizing their critical role in advancing Industry 4.0 toward the frontiers of Industry 5.0. The article explores the applications of DT in several industrial sectors and their smooth integration into the IIoT, focusing on the fundamentals of digital twins and emphasizing the importance of virtual-real integration. It discusses the emergence of DT, contextualizing its evolution within the framework of IIoT. The study categorizes the different types of DT, including prototypes and instances, and provides an in-depth analysis of the enabling technologies such as IoT, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Extended Reality (XR), cloud computing, and the Application Programming Interface (API). The paper demonstrates the DT advantages through the practical integration of real-world case studies, which highlights the technology’s exceptional capacity to improve traceability and fault detection within the context of the IIoT. This paper offers a focused, application-driven perspective on DTs in IIoT, specifically highlighting their role in key production phases such as designing, intelligent manufacturing, maintenance, resource management, automation, security, and safety. By emphasizing their potential to support human-centric, sustainable advancements in Industry 5.0, this study distinguishes itself from existing literature. It provides valuable insights that connect theoretical advancements with practical implementation, making it a crucial resource for researchers, practitioners, and industry professionals.Keywords

In the era of Industry 4.0, businesses are increasingly utilizing advanced technologies to enhance operational efficiencies and gain a competitive edge. IIoT is revolutionizing manufacturing by connecting the physical and digital worlds, leading to the deployment of cyber-physical systems (CPS). IIoT adds value to traditional devices and has emerged as a crucial business and technology paradigm in the era of Industry 4.0. From raw material processing to the final product, the product lifecycle involves complex phases, including intricate industrial processes and supply chain events. In navigating this complex field, industries face the challenge of managing multiple intertwined factors to maximize revenues. Key considerations include cost management, risk assessment, and quality assurance. To thrive in this dynamic environment, industries must adopt a comprehensive approach that addresses the complexities of the manufacturing process [1]. Currently, a multitude of transformative technologies are reshaping the industry landscape. Examples of these include the IoT, 3D simulations, high-performance computing, AI, and distributed ledger technology [2]. Properly utilizing these emerging technologies to improve overall efficiency is the main concern in industrial infrastructure. A promising solution lies in creating a digital fingerprint or virtual replica of the underlying product, process, or service. This digital representation allows thorough analysis, prediction, and optimization of all operations before they are implemented in the real world. Through a closed loop, data generated from simulations are fed back to the physical system, enabling the calibration of operations and the improvement of system performance. This reciprocal mapping between the physical and virtual realms is commonly referred to as a DT.

DT technology has garnered significant attention from both industry and academia, becoming a key innovation across various sectors. This technology enables the creation of realistic virtual representations of objects and simulations of operational processes. A 2019 Gartner survey [3] highlighted that DTs were entering mainstream use, with projections suggesting that by 2027, more than 40% of large companies around the world will adopt DTs to enhance revenue [4]. The DT industry, valued at $8 billion in 2022, is expected to grow at a robust Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of approximately 25% between 2023 and 2032, according to Global Market Insight [5]. Furthermore, a global technology report predicts that the DT market will expand by nearly $32 billion between 2021 and 2026. Aligning with these trends, a 2022 report revealed that nearly 60% of executives across various industries plan to integrate DTs into their operations by 2028 [6]. This cutting-edge technology, capable of digitally replicating goods, services, and processes, has revolutionized industries. By providing engineers with feedback from virtual environments, DTs enable businesses to quickly identify and resolve physical issues, optimize product design, and enhance development processes [7]. Furthermore, DTs improve business performance by streamlining operations and accelerating the achievement of value and competitive advantages [8].

The integration of the IoT and DT can facilitate the merging of the digital (virtual) and physical (real) worlds, serving as a pivotal factor in maximizing the potential of IIoT [9]. In the standard IIoT framework, DT is commonly positioned in the service layer as a logical entity, capable of virtualization and replication [10]. A common use case involves establishing a DT system in the cloud to offer services. A pivotal question driving current research is how can DTs be integrated within the IIoT to enhance operational efficiencies in Industry 4.0? This question forms the main objective of our paper, which guides the exploration of the synergy between DTs and IIoT. We aim to enhance the understanding of DT by conducting a thorough examination that encompasses its definition, applications, historical evolution, technological foundations, practical implementations, challenges, and future research directions. Our exploration takes place within the context of Industry 4.0 and the emerging landscape of Industry 5.0. Key contributions of our work include the following.

• Providing a detailed analysis of the definition and concept of DT across a range of industrial sectors.

• Highlighting the diverse applications of DT, with a particular emphasis on how it facilitates the connection between virtual and physical domains within the framework of Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0.

• Investigating the historical development of DT, offering insights into its transformative journey and its impact on industrial practices.

• Engaging in a comprehensive discussion of the enabling technologies that drive the development and effectiveness of DT.

• Exploring practical applications of DT in various domains, including manufacturing, maintenance, resource management, supply chain, automation, safety, and security.

• Addressing the challenges encountered in the implementation of DT and providing information on future research directions.

2 Background Concept and Definitions

The concept of a DT originated in computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided engineering (CAE), which emerged during the 1960s and 1970s. These technologies enabled engineers to develop virtual models and simulations of physical entities and systems, which allowed them to explore and optimize their designs before they built the physical prototypes. The theoretical idea of DTs initially appeared in the book by David Gelernter titled “Mirror Worlds”, published in 1993 [11]. The author envisioned the idea of software models replicating reality using data input from the physical world. In 2002, Michael Grieves, a professor at the University of Michigan, provided a conceptual description by introducing a three-component model related to Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) systems for manufacturing and was initially referred to as the “Mirrored Spaces Model” [12]. Later, the author changed its name to “Information Mirroring Model” in his first book on PLM, published in 2006 [13]. However, in recent years, the author himself also referred to the DT as a Virtual Doppelganger [14]. Apart from that, Framling et al. [15] in 2003, proposed an agent-based framework in which every single consequent item has a connected “agent associated with it” or “virtual counterpart” as a resolution to inefficient transfer of production details by paper for PLM. Similar to DT, Hribernik et al. [16] introduced another concept called the “product avatar” in 2006. The concept aims to establish an information management framework that facilitates a bidirectional flow of information from a product-centric point of view.

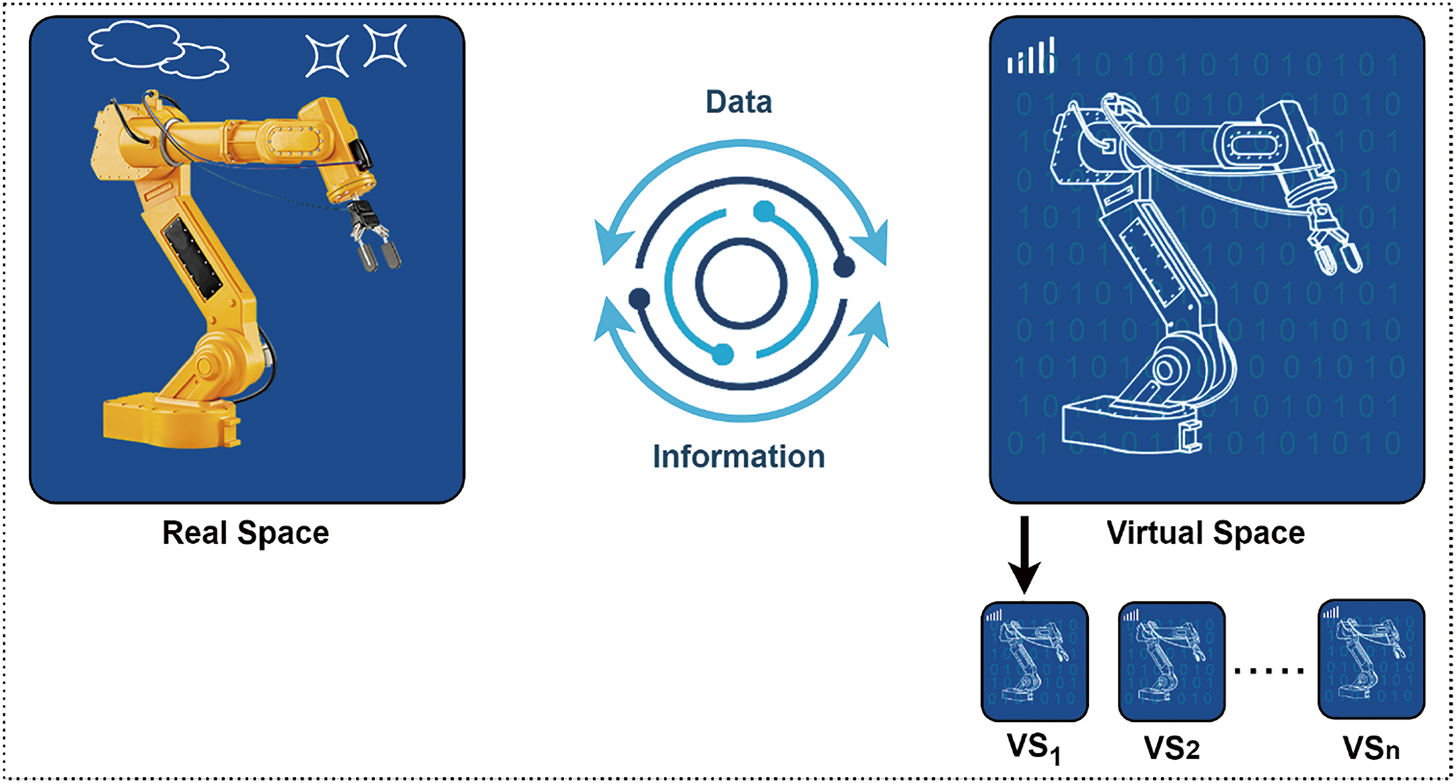

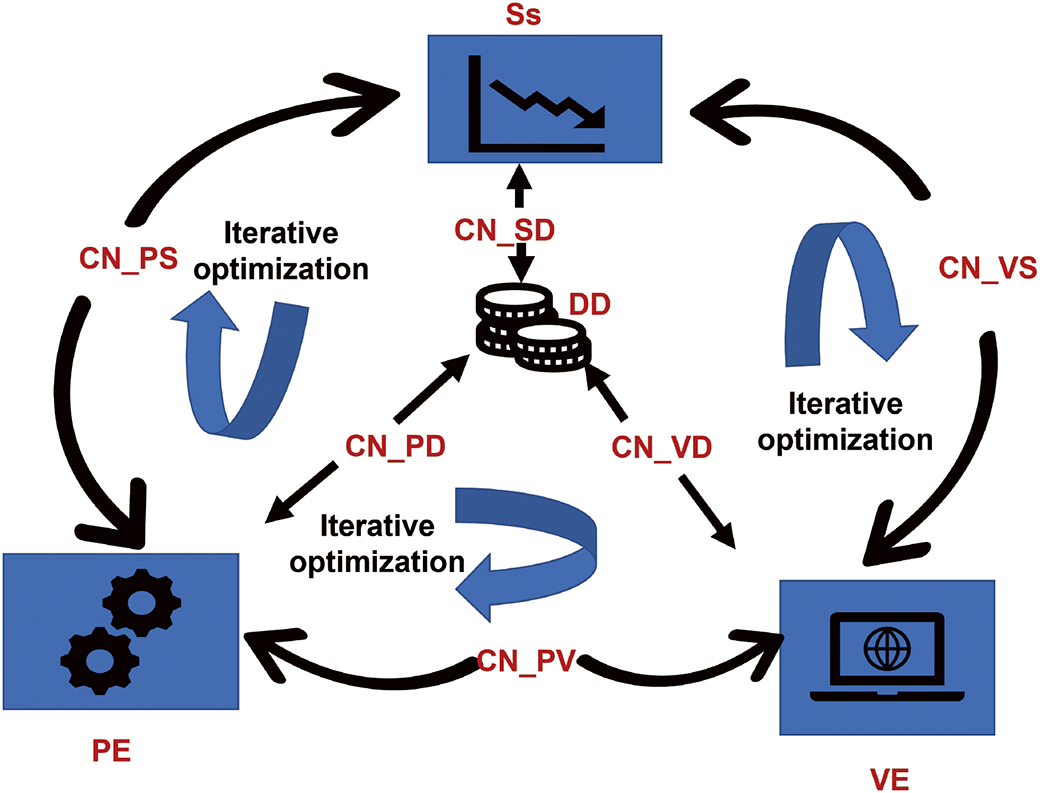

John Vickers, a colleague of Michael Grieves, introduced the term “Digital Twin” for the very first time at the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). This term was coined after several other names (e.g., Virtual Twin) had been considered. In his 2010 roadmap, he introduced the concept of DT within NASA [17]. However, NASA had previously employed the same concept during the Apollo program as a “living model”, in which two identical spacecraft were manufactured exactly mirror to each other [18,19]. Subsequently, following NASA’s footsteps, the US Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) adopted DT technology for aircraft design, maintenance, and prediction [20]. The proposed approach involved utilizing DT technology to replicate the aircraft’s physical and mechanical characteristics, aiming to forecast potential fatigue or structural cracks. This strategy would effectively extend the operational lifespan of the aircraft [21]. Tuegel et al. [22] and Gockel et al. [23] proposed the concept of DT entirely for aircraft and referred to it as the “Airframe Digital Twin”. This required creating a digital model to oversee the aircraft during every phase of its life. Following that, the concept of DTs has garnered significant attention within the aerospace industry. In 2014, Professor Grieves published a white paper to provide a more comprehensive explanation of the connotation. The article [24] comprehensively analyzed the DTs conceptual model, fulfillment requirements, and use cases. The three components of Grieves’ proposed model include the Real Space, the Virtual Space, and the interlinking mechanisms between these two for transferring data/information enabling seamless convergence and synchronization between them [25]. The real space represents the physical environment where data is collected, while the virtual space is its digital replica that analyzes, simulates, and provides feedback to optimize real-world operations in real-time. The interlinking mechanisms include IoT devices, data communication protocols, edge and cloud computing, machine learning algorithms, and feedback control systems [26–28]. As shown in Fig. 1, the virtual space may comprise several virtual domains corresponding to a singular physical space. Within these domains, alternate concepts, designs, modelling, testing, and optimization might be explored simultaneously. There are numerous interpretations of the concept of DTs. Some scholars argue that DT studies should focus on simulation, while others contend that DT has three components: physical, virtual, and link parts [29]. The development and application of DT are dependent on novel products and requirements due to the ongoing expansion and improvement of application demands. In recent years, the adoption of DT has progressively widened to encompass civilian sectors, following its initial implementation in the military and aerospace domains. The increasing number of application domains has resulted in an increased demand for services from DT across various fields, user levels, and business sectors. At the same time, the Internet of Everything (IoE) creates the conditions required for cyber-physical contact and data integration that are crucial to DT. Therefore, Tao et al. [30] posited that a comprehensive DT ought to comprise five dimensions, namely the physical entity, virtual entity, connectivity, data, and service, based on the Grieves three-dimensional model of the DT. Fig. 2 illustrates the conceptual framework in which PE and VE denote physical and virtual entities, respectively.

Figure 1: The current conceptual model of the DT illustrates the link between the Virtual and Real Spaces

Figure 2: Five dimensional DT model architecture

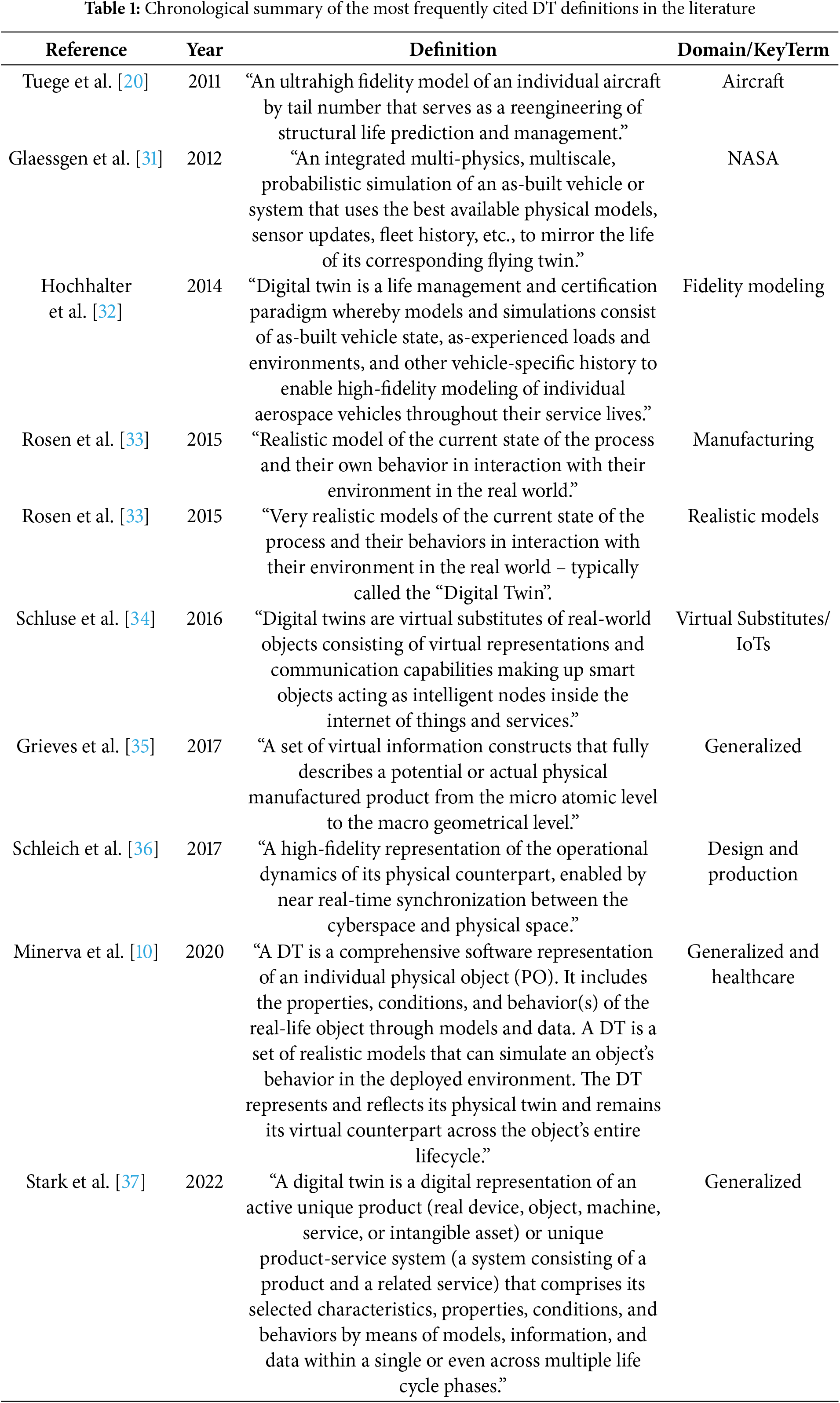

NASA was the first to provide an explicit description of DT, which was the most widely adopted and accepted definition at the time. Since then, different industries and researchers have proposed various descriptions and definitions of DT in the academic literature based on specified applications. Hence, the concept of DT is still relatively fuzzy because the research and number of publications on DTs are rapidly increasing. As a result, there is no universal definition of DT that is valid and applies to all applications [38]. In fact, numerous definitions can be discovered in the existing literature. These definitions exhibit significant differences with respect to the scope of coverage, technological aspects, and requisite characteristics that a DT must possess. In simple terms, DTs are virtual representations of actual assets that are made functional through data and simulators to enable instantaneous prediction, monitoring, optimization, supervision, control, and improved decision-making [39]. Table 1 presents a chronological summary of the most frequently cited DT definitions in the literature, demonstrating the evolution of the DT concept.

DT can be compared to several existing concepts, including simulations, emulations, digital shadows, and digital threads, but it is distinctly different in its functionality and purpose. A DT represents a virtual replica of a real-world system that not only receives data from the physical counterpart but also sends feedback to enable closed-loop control and decision-making. Unlike simulations, which focus on replicating the internal state of a system to predict potential behaviors, DTs maintain a continuous, dynamic connection with the physical system for real-time interaction. Emulations, on the other hand, aim to mimic the external behavior of a system as closely as possible but do not achieve the bidirectional data flow characteristic of DTs. Additionally, although DTs and digital shadows both create a digital representation of physical objects or processes, digital shadows operate with one-way data flow changes in the physical world to update the virtual model, but there is no reverse interaction [40]. In contrast, DTs facilitate two-way communication, enabling both monitoring and control. Another related concept is the digital thread, which serves as a framework connecting the different components of a DT. It provides a comprehensive, integrated view of an asset’s lifecycle, from design to manufacturing and maintenance. The digital thread bridges data silos, allowing seamless access to critical information for lifecycle management, whereas DTs leverage this framework for enhanced representation, analysis, and control of systems [41].

2.3 Industrial Revolution and Emergence of DT in Industry 4.0

During the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, production processes were automated through the use of steam and water power. Then came the second industrial revolution, defined by the use of electricity to set up assembly lines and enable mass manufacturing. A major change occurred during the third industrial revolution when companies adopted computing and embedded hardware, resulting in production automation. The fourth industrial revolution is commonly defined as a smart manufacturing setting that integrates high-tech manufacturing technologies, forming an interconnected manufacturing system capable of analyzing, communicating, and utilizing data to make smart decisions in the real world. Industry 4.0 utilizes analytics, AI, and the IoT to improve operational procedures and decision-making [42,43].

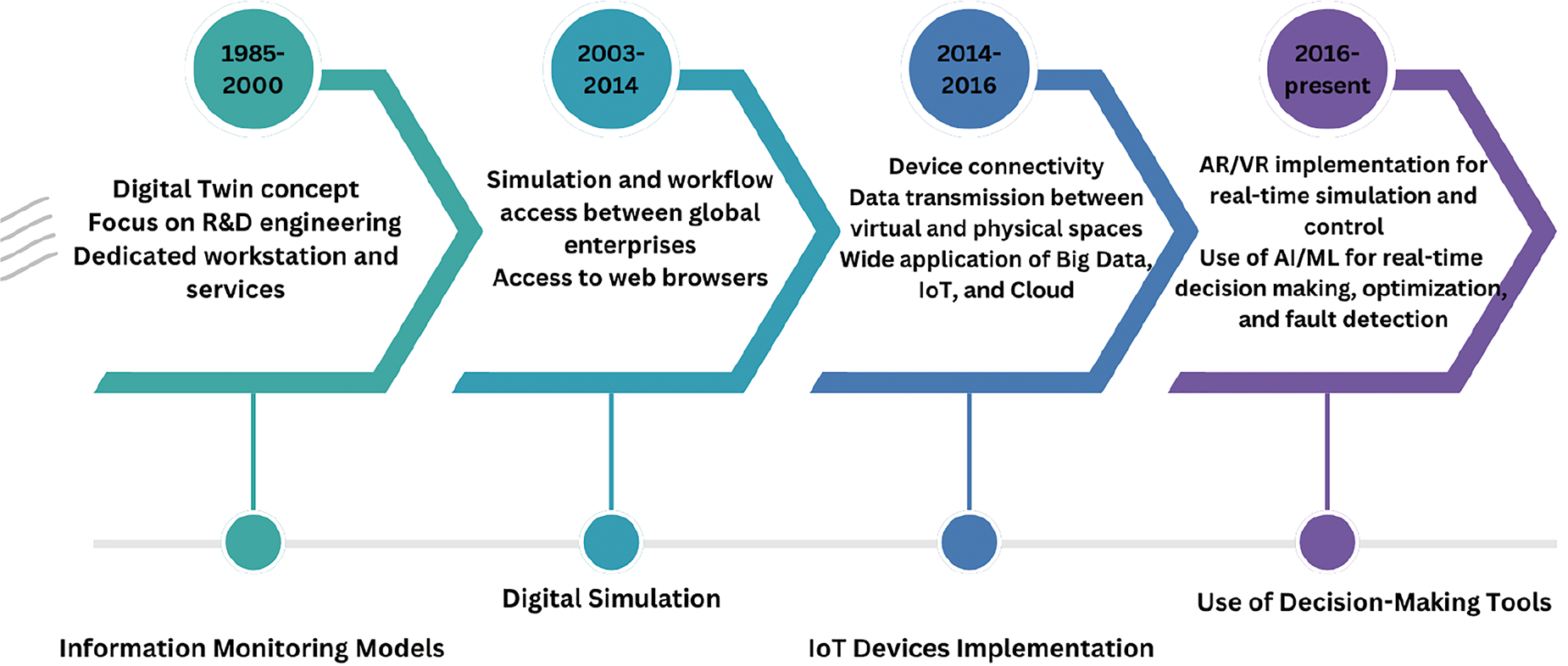

The industrial evolution of DT can be delineated into four distinct phases as shown in Fig. 3. The initial phase, spanning from 1985 to 2000, emphasized the information monitoring model specifically designed for workstations and services. The second phase, from 2003 to 2014, was characterized by a shift towards digital simulation. The third phase, extending from 2014 to 2016, saw the implementation of IoT devices. Lastly, the fourth phase, starting from 2017 to the present, is dedicated to the utilization of decision-making tools [44].

Figure 3: The evolutionary growth of digital twins in manufacturing

Two pivotal concepts stand out in the realm of Industry 4.0, namely DT and IIoT. IIoT plays a crucial role in enabling the real-time acquisition, processing, and analytics of data generated by sensors within an intelligent factory. On the other hand, DT technology, with remarkable precision, empowers Industry 4.0 to create digital replicas of people, physical machines, or processes. Consequently, IIoT emerges as an indispensable strategic element. It serves as an essential foundation to unleash the complete capabilities of DT [45]. IIoT records the physical experiences of people, processes, and products, meeting the fundamental requirements of authentic DT to optimize operations both in the factory and the field. Consequently, DT empowers manufacturing companies to create superior products, identify physical issues earlier, and make more accurate predictions. The broad use of DT technology was impeded until recently by limits in digital technology capabilities, such as bandwidth, computing, and storage expenses. However, the manufacturing industry has seen exponential growth in the use of DT due to much lower costs and improved computational capabilities [46].

The following section describes the various types of DTs and the enabling technologies that support their implementation.

3 Digital Twin Types and Enabling Technologies

Grieves and Vickers [35] have identified two subtypes of DT, namely: Digital Twin Prototype (DTP) and Digital Twin Instance (DTI). The platform known as Digital Twin Environment (DTE) integrates and operates both design and production phases for various purposes. This means that it can be used either at the stage of design or after the product has been finalized during the production phase.

3.1.1 Digital Twin Prototype (DTP)

DTP refers to the process of creating a physical copy from a virtual one by collecting all the necessary data and information such as design files, bills of materials, CAD models, etc. Before creating any physical twin, the product cycle begins with creating a DTP that may undergo a series of tests, including damaging ones. DTP is crucial as it assists to identify and prevent unanticipated and unwanted circumstances that are challenging to detect using conventional prototyping. Once the DTP is completed and verified, its physical twin is created in the real world. The quality of the physical twin depends on the precision of the simulation or model used during the DTP process.

3.1.2 Digital Twin Instance (DTI)

DTI is created during the production process to remain connected to its physical version throughout its lifespan. After the completion of a physical system, data obtained from the physical spaces is sent to the virtual space and reciprocally, used to oversee and anticipate the system’s performance [35]. By analyzing this data, it is possible to determine whether the system is behaving as desired and whether any predicted undesirable situations have been effectively mitigated. Since the connection between the two systems is bidirectional, any modifications made to one will be reflected in the other. The authors of [35] proposed the term “Digital Twin Aggregate” (DTA) to describe a group of DTIs.

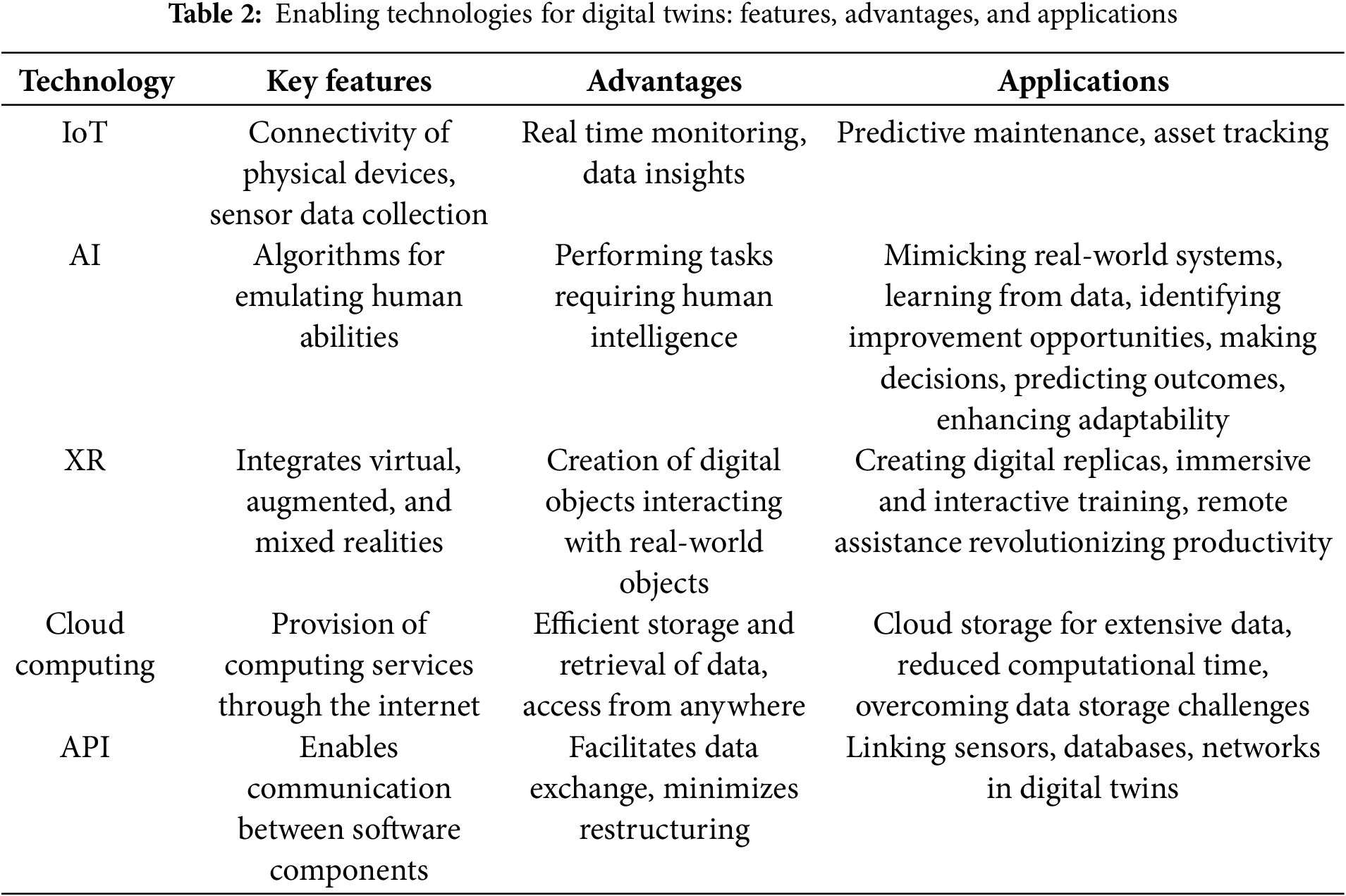

According to literature [47], DTs consist of three primary phases: the data acquisition phase, the data modeling phase, and the data application phase. But, Attaran et al. [48] explained that the DT technique incorporates a combination of four technologies to acquire and store real-time data, extract details to provide meaningful insights, and build a virtual model of an actual entity. The technologies above encompass the Extended Reality (XR), AI, IoT, and Storage (Cloud). Furthermore, Warke et al. [44] added the API to the list, as illustrated in Fig. 4. However, the implementation of DT relies on a specific technology, which varies in its degree of utilization based on the type of application.

Figure 4: Digital Twin enabling technologies

3.2.1 Internet of Things (IoTs)

The term IoT pertains to an extensive network of interconnected entities commonly named “things”. The relationship can manifest in various forms, including but not limited to thing-things, human-things, or human-human interactions [49]. It is a technology that is used primarily and is adopted by DT almost in all applications. According to a study [6], it is projected that by 2027, over 90% of IoTs platforms will be able to perform Digital Twinning. The IoT employs sensors to acquire data from real-world entities. This acquired data is further used to generate a virtual replica of that physical entity. Later, different processes like analysis, manipulation, and optimization, can be applied to this digital version. The ability of IoTs to continuously update the data helps the DT application create a real-time virtual representation of a real object.

3.2.2 Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI is a subfield of Computer Science devoted to the evolution of intelligent machines that can perform tasks that usually require human intelligence. AI involves the development of algorithms and models that enable computers or machines to mimic or simulate human cognitive abilities such as learning, problem solving, perception, and decision-making. AI has the potential to assist DTs through the utilization of advanced analytical tools such as Neural Networks (NN), Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), and expert systems [50]. In the context of Industry 4.0, AI plays a key role in enabling DTs to mimic complex real-world systems. By accessing data from IoT devices, AI learns and operates alongside actual manufacturing systems. It identifies opportunities for improvement and provides crucial support in making tactical decisions. ML algorithms play a pivotal role in predictive maintenance by analyzing historical and real-time data to forecast equipment health and optimize maintenance schedules. Key contributions of ML in predictive maintenance include data analysis, real-time monitoring, and cost reduction. Neural networks and deep learning greatly enhance the capabilities of DTs by providing advanced data analysis and real-time decision-making. Neural networks are particularly effective in optimizing processes by simulating system behavior and enabling dynamic adjustments to improve efficiency [51]. Deep learning shines in predictive maintenance, using sensor data to detect subtle patterns and predict equipment failures before they happen [52]. These technologies also excel at anomaly detection, identifying deviations or potential faults in complex, high-dimensional data. By integrating these tools, DTs become smarter and more reliable, offering valuable insights for advanced industrial applications. Recent studies indicate that incorporating AI has the potential to enhance the adaptability of DTs to cope with dynamic alterations in workshops and factories. This improved adaptability offers useful applications, especially in areas such as control, quality assurance, and production planning [53].

The term XR encompasses a range of immersive technologies, including Virtual (VR), Augmented (AR), and Mixed Realities (MR). These technologies have the ability to integrate the physical and virtual worlds and expand the scope of our experienced reality [54]. XR technology enables the creation of digital objects that can coexist and interact with real-world objects in real time. DTs employ XR capabilities to create a digital replica of real-world objects by enabling individuals to interact and communicate with digital content. Furthermore, human-to-human interactions can be greatly enhanced by XR technology, especially in the context of training and remote aid [55]. In an industrial setting, for example, a trainer can guide trainees through procedures or processes in a virtual environment, giving them the opportunity to experience and learn in a context that is immersive and interactive from a distance. In the same way, real-time AR instruction for technicians can revolutionize remote help by decreasing the requirement of physical presence, increasing productivity, and reducing cost [53].

A key advantage of Industry 4.0 lies in the real-time gathering of data through IoT and IIoT sensors embedded in every plant asset. This continuous and transmitted data serves as a valuable source, offering crucial insights into the overall performance of the factory. Furthermore, these insights can be leveraged to make informed decisions related to production, inventory control, and forecasting. However, the sophisticated technologies inherent in Industry 4.0, such as IoT, AI, and DT, require robust computational potential and storage. Creating an in-house solution is not economically viable [49]. Cloud computing provides DTs with cloud storage and data computing technologies. Also, it allows DT to store extensive amounts of data in the virtual Cloud and instantly access the relevant information from anywhere at any location. By using cloud computing, DT can reduce the computational time required for complex systems and overcome challenges associated with storing huge amounts of data [56].

3.2.5 Application Programming Interface (API)

As DTs are software-based representations of their corresponding physical entities, these software-based representations operate via application program interfaces (APIs). The API serves as a link for enabling communication between various components such as sensors, databases, and networks, facilitating the exchange of data and information. It minimizes the need for extensive restructuring in response to modifications in the given scenario [44]. The key features, advantages and application of enabling technologies for DT are summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 5 illustrates a cohesive integration of an AI-based system, blockchain, and a DT to form an intelligent and trusted DT ecosystem. At the core of this framework is the intelligent DT, which serves as a dynamic and reliable virtual representation of a physical asset or system. The AI-based system, positioned at the top, plays a crucial role in analyzing production data and providing insights for continuous model calibration, ensuring the DT accurately reflects real-time conditions. On the left, the blockchain component secures the system by recording and storing updated models and data changes, creating a tamper-proof and transparent ledger that guarantees data integrity and authenticity. Meanwhile, the DT, situated on the right, feeds operational data back to the AI system, enabling refined decision-making and predictive analytics. The interaction between these components is seamless and cyclic production data is provided to the AI system, insights and updates are securely stored on the blockchain, and the DT continuously evolves with accurate and verified information. This integrated approach enhances system efficiency, security, and decision-making capabilities, enabling proactive maintenance, optimized operations, and resilient performance across various industrial applications.

Figure 5: Synergizing AI and blockchain for smart and trusted digital twins [57]

4 Integration with Industry 4.0

Industry 4.0 encompasses a broad spectrum of innovative technologies and digital advancements that are transforming production processes by seamlessly integrating the physical and virtual realms. Despite the gradual evolution of these developments, many organizations have been cautious in establishing extensive digital networks for their production operations, incorporating IIoT platforms along with the DT concept for production lines and manufacturing devices. The creation of a thorough DT requires a substantial amount of information from various sources to construct a representation that closely mirrors the real entity. Industry 4.0 environments involve a wide variety of devices, systems, and protocols that generate and process data in different formats. Ensuring seamless communication between heterogeneous systems and enabling consistent data exchange often requires advanced standardization and middleware solutions, which can be complex and resource-intensive. The real-time data exchange required for DTs relies heavily on robust and low-latency network infrastructure. Challenges such as unreliable connections, limited bandwidth, and cybersecurity threats can hinder the smooth functioning of DT systems in Industry 4.0 setups. This is especially critical in distributed manufacturing environments or remote operations where connectivity stability may be compromised. The DT must accurately simulate the behavior of particular physical elements and how they interact with other elements, and the overall DT itself. Through remote operation, augmented and virtual reality equipment enables optimal predictive maintenance, enhancing efficiency in manufacturing processes [58–60].

The term “Industry 4.0” describes the multitude of tools and systems required to establish the fabled “lights out” factory, where worker safety is maximized and human presence is drastically reduced. In order to be competitive in the next years, manufacturers need to reconfirm their obligation to invest in IIoT framework that collects and analyzes data as well as DTs that use the data to track, control, and enhance industrial operations [61,62]. The first step in implementing Industry 4.0 business models is to collect and analyze data in an organized manner, which is necessary for making accurate decisions and executing relevant tasks. A metamodel can assist organizations in navigating this complex transformation process toward Industry 4.0 [63]. The goal of the DT for Industry 4.0 product is to digitally represent authentic machinery and procedures that are connected to their physical counterparts through mechanical, geometric, and behavioral characteristics [64,65]. The DT solution for Industry 4.0 applies to businesses across diverse fields seeking to digitally transform their industrial assets. Specifically tailored for manufacturing organizations, the solution aims to enhance production system efficiency, improve product quality, and reduce waste and environmental impact.

Implementing the DT concept for Industry 4.0 poses distinctive challenges. The DT model extends beyond IoT devices, requiring broader abstraction capabilities. A comprehensive DT solution should not only support the modeling of individual IoT devices but also encompass a wider range of abstraction functionalities. It should enable users to design customized DT models tailored to their specific industry or use case. The platform must include a provisioning framework for creating DTs and establishing their connections with various IoT devices.

4.1 Revolutionizing Industry: DTs and the Shift to Industry 5.0

Industry 5.0 is a new industrial framework that focuses on sustainability and social responsibility. It aims to minimize the adverse ecological impacts on the environment. This concept introduces various challenges across technological, socioeconomic, regulatory, and governance spheres. The transition from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 represents a paradigm shift in industrial evolution. It is characterized by enhanced connectivity, intelligence, and collaboration. Several Key enabling technologies enable the transition from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0. These technologies encompass several crucial elements:

• Solutions centered around human needs and technologies facilitating interaction between humans and machines, leveraging the strengths of both.

• Bio-inspired technologies and intelligent materials that enable the creation of materials that can be recycled, embedded with sensors, and enhanced characteristics.

• Simulation and real-time DTs, serving to develop the complete systems.

• Cybersecurity technologies for transmission, storage, and data analysis, capable of managing system and data interoperability.

• AI, with the capability to identify causal relationships in complex, dynamic systems and generate valuable information.

• Energy-efficient and reliable automation technologies, given the substantial energy requirements of the key enabling technologies.

Fig. 6 compares the key characteristics of the two industrial revolutions, highlighting their differences in time period, technologies, human roles, supply chain structures, and production approaches. Industry 4.0 represents the current industrial era, beginning in the early 21st century and characterized by the adoption of technologies such as the IoT, AI, and Big Data as mentioned in the previous sections. It focuses on advanced AI replacing human labor in repetitive tasks and is supported by agile and responsive supply chains designed for flexibility and adaptability. Production in Industry 4.0 emphasizes flexible and adaptive processes that cater to changing market demands. In contrast, Industry 5.0 envisions the future of industrial development, with a focus on emerging technologies such as nanotechnology and renewable energy. Unlike Industry 4.0’s centralized, agile supply chains, Industry 5.0 prioritizes decentralized and sustainable supply chains to minimize environmental impact. Through the incorporation of innovation and cognitive abilities, various technological trends such as DT, Big Data Analytics (BDA), Edge Computing (EC), IoE, Cobots, blockchain, and 5G, can assist industries in boosting production and delivering customized products more rapidly. Industry 5.0 represents an advanced production model emphasizing the communication between humans and machines, facilitated by these enabling technologies. DTs involve transferring data from real objects to their virtual counterparts via IoT devices to enable simulation. This process allows for the analysis, monitoring, and proactively addressing problems before they manifest in the physical world. This can be accomplished through the real-time digital mapping of systems and objects. The rapid advancements in BDA, ML, and AI have enabled DTs to reduce maintenance expenses and enhance overall system performance [66,67]. In the context of Industry 5.0, DTs play a crucial role in customization, enhancing the user experience by aligning products with specific requirements. Industry 4.0 has already integrated advanced technologies to enhance manufacturing productivity [68]. Additionally, wearable technologies play a critical role in optimizing industrial processes [69]. Despite these advancements, debates persist regarding the challenges and opportunities of automation, particularly concerns about job displacement and the demand for upskilling and reskilling the workforce. Industry 5.0 builds upon these discussions by emphasizing collaboration between humans and machines rather than focusing on human replacement, thus recognizing the value of human expertise and skills alongside intelligent technologies [70]. Based on the existing literature, we can categorize the objectives of Industry 5.0 into three categories. These three fundamental objectives are resilience, sustainability, and human-centricity [71].

Figure 6: Industry 4.0 v/s Industry 5.0

A human-centric approach in Industry 5.0 aims to prioritize human needs within digital transformation efforts, fostering collaborative workspaces shared with autonomous robots [72]. Kaasinen et al. [73] propose three key strategies for designing effective human-machine collaboration. First, it is essential to analyze the complex networks formed by interactions between humans and non-human actors, recognizing technology’s influential role and understanding interactions and processes in digitalized networks. Second, operations in Industry 5.0 should be designed from a user-oriented perspective, focusing on system characteristics, operational goals, constraints, and high-level user requirements. Finally, ethical design is critical, emphasizing worker autonomy, privacy, dignity, and meaningfulness. This can be achieved through methods such as value-sensitive design, ethical impact assessments, and the development of ethical guidelines to guide responsible decision-making.

Human-centricity extends beyond individual workers using technology, encompassing all stakeholders involved in or impacted by the system, both within and outside the organization, now and in the future. By addressing these broader perspectives, Industry 5.0 has the potential to revolutionize the industrial sector, moving beyond productivity and operational enhancements to foster sustainable and inclusive development. In Industry 5.0, sustainability emphasizes meeting current production demands without compromising the ability of future generations to fulfill their needs. Achieving this involves optimizing the use of resources like energy, water, and raw materials to minimize waste and reduce the environmental impact of manufacturing processes. AI plays a vital role by monitoring and analyzing environmental conditions using data from sensors, satellites, and other sources. As the first human-led industrial revolution, Industry 5.0 is guided by the 6R principles: reduce, realize, reuse, recycle, reconsider, and recognize. These principles promote the development of circular methods for repurposing, reusing, and recycling natural resources to minimize waste and environmental damage, ultimately fostering a circular economy that enhances resource efficiency and effectiveness [69].

Additionally, incorporating EC supports sustainability by reducing the need for extensive data transfers to centralized data centers. By processing and filtering data locally, edge devices communicate only critical insights, reducing the volume of transmitted data. This approach decreases network congestion, lowers energy consumption, and minimizes the carbon footprint associated with large-scale data transmission, aligning with the sustainability goals of Industry 5.0.

4.2 Emerging Use Cases of Digital Twins in Industry 5.0

Existing studies have extensively explored DTs for enhancing operational efficiency, monitoring energy usage, and improving worker safety. However, significant opportunities remain for extending and refining these use cases to address emerging trends and challenges in Industry 5.0. The following details present innovative and emerging applications that build upon or extend current research, contributing to more sustainable, resilient, and human-centric industrial environments.

• Carbon Footprint and Emissions Monitoring in Green Manufacturing: DTs can be employed for real-time monitoring and simulation of carbon emissions at different stages of production. By integrating carbon footprint prediction models, DTs can optimize manufacturing workflows to reduce emissions, improve sustainability assessments, and enhance compliance with environmental regulations.

• Personalized Human-Robot Collaboration for Enhanced Worker Safety: A novel application involves creating DT models of human workers and collaborative robots (cobots). These DTs can monitor motion patterns to predict safety risks and provide real-time safety alerts, reducing workplace accidents and promoting safer human-machine interactions.

• Zero-Waste Supply Chain Management: DTs offer the potential to develop dynamic, zero-waste supply chain models. By simulating waste generation throughout production and logistics, DTs can provide actionable recommendations for material reuse, recycling, and inventory optimization, advancing circular economy practices.

• Dynamic Energy Pricing and Resource Allocation: Integrating DTs with dynamic energy pricing systems allows smart factories to optimize resource consumption. DTs could dynamically adjust production schedules in response to fluctuating energy costs, minimizing operational expenses and maximizing energy efficiency.

• Circular Economy through Lifecycle Traceability: DTs can enable circular economy strategies by providing detailed lifecycle traceability of products. Digital threads powered by DTs could track products from creation to disposal, facilitating refurbishment, recycling, and sustainable resource use.

• Decentralized Data Markets for Manufacturing Networks: By combining DTs with blockchain technology, secure and decentralized data-sharing platforms can be established. These platforms would allow manufacturers to monetize operational insights and foster collaborative innovation within and across industries.

• Cognitive Load and Mental Fatigue Monitoring: DTs can simulate and monitor worker cognitive states using biometric data. This approach would enable real-time mental fatigue detection, allowing dynamic task adjustments and break scheduling to reduce burnout and enhance productivity.

• Autonomous Quality Control and Defect Prediction: DTs integrated with AI-driven prediction models could revolutionize quality control by identifying subtle defect patterns before they become problematic. This proactive approach would reduce material waste, improve product consistency, and minimize costly rework.

• Water Resource Optimization in Manufacturing: DTs of water management systems can be used to monitor consumption, simulate recycling strategies, and optimize water usage. Such implementations would help manufacturers achieve sustainability targets and conserve critical resources.

• Predictive Supply Chain Resilience: DTs can simulate geopolitical, economic, and logistic risks to predict supply chain disruptions. Using these insights, manufacturers can develop adaptive strategies to ensure business continuity and maintain supply chain robustness during global crises.

4.3 Smart Factories and Roles of DT

The integration of IoT and CPS technologies into manufacturing systems has brought about enhanced capabilities, allowing the management of intricate and adaptable systems to effectively handle sudden changes in production quantity and customization needs [74]. These new technologies contribute to the development of effective real and virtual manufacturing systems, elevating awareness of context to support both people and machines in the seamless execution of their tasks [75]. Context-awareness involves having knowledge about system components, understanding the past of system performance, and being aware of the current state of the system. This type of manufacturing system is commonly referred to as a smart factory. In the realm of Industry 4.0 research, the term “smart factory” holds significance, often considered as the core of the Industry 4.0 paradigm. The major roles of DT in smart factories include the following: tracking a product throughout its life cycle [76], designing and validating products [77,78], real-time monitoring and control [79], predictive maintenance [35], energy management [29], worker safety and training [78], supply chain optimization, and enabling customization and flexibility in production processes [79].

4.4 IoT and Connectivity in DT Systems

The integration of IoT with DT technology in Industry 4.0 offers several advantages:

• Enhanced monitoring of machine operations and the state of systems that are interconnected.

• Precise forecasting through the retrieval of future machine states from the DT model.

• Conducting hypothetical analyses by engaging with the model to simulate distinct machine scenarios.

• Understanding, documenting, and explaining the characteristics of a specific machine or a combination of machines

5 Application of DT in Industrial Enterprises

The use of DT technology has seen tremendous transformation in the field of industrial companies. This section demonstrates the importance and diverse applications of DT by examining its varied role across key fields. These areas were selected because they represent the core stages and critical components of industrial operations. Starting with design, DT enables precise virtual modeling, which is essential for efficient smart manufacturing. The progression includes predictive maintenance, resource optimization, supply chain traceability enhancement, automation, intelligent control systems, and robust safety and security monitoring with swift threat response. These interconnected applications demonstrate DT’s potential to enhance operational efficiencies and drive innovation in the industry. The following subsections will elaborate on this.

The integration of the DT facilitates the convergence of the information model and the physical model of a product, leading to iterative optimization. This, in turn, results in a shortened design cycle and reduced costs associated with rework [80]. Typically, the design process involves four key steps: a) defining tasks, b) conceptualizing the design, c) embodying the design, and d) detailing the design [81].

In [82], a ’cobbler model is discussed where the cobbler possesses knowledge of customer requirements, design constraints, required materials, and the associated processes. The DT presents itself as a potential substitute for ‘the cobbler’s mind’ in the current landscape of complex and variable products, enhancing data integrity, product traceability, and accessibility to knowledge. According to Tao et al. [29], DT technology allows designers to create a comprehensive digital representation of products during the design process. It functions as an ‘engine’ that transforms large sets of data into actionable information. Designers can then directly use this information to make well-informed decisions at various stages of the design process. The paper envisions the capabilities of DTs in task clarification, conceptual design, and virtual verification.

5.2 DT in Intelligent/Smart Manufacturing

The term ‘smart manufacturing’ first appeared in literature in the 1980s. Manufacturing has embraced the digital age with the help of development in data-acquisition systems, IT, and networking technologies. With significant advances in digital technologies, the manufacturing industry is confronting worldwide problems [83]. Various advanced manufacturing initiatives have been developed in response, including the Industrial Internet in the United States [84], Society 5.0 in Japan [85], Industry 4.0 in Germany [86], “Made in China 2025” and “Internet +” in China [87]. The influx of future manufacturing visions hinges on utilizing the potential of computation in production systems. The goal of these methods is smart manufacturing [88], often known as intelligent manufacturing. Smart manufacturing, as defined by Davis et al. [89], is the widespread, intensive use of “manufacturing intelligence” in all aspects of industrial manufacturing and supply chain. It involves advanced sensor-based data mining, modeling, and simulations to enable real-time perception, reasoning, planning, and management of all facets of manufacturing processes. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) of the United States, “smart manufacturing systems” are “fully-integrated, collaborative manufacturing systems that respond in real time to meet changing demands and conditions in the factory, in the supply network, and customer needs”.

The manufacturing sector is transforming rapidly. Therefore, there is growing interest in utilizing technology such as DTs in the industrial sector. The specific application of DT for the optimization of the process and real-time tracking has been made possible by the recent technical developments in monitoring, decision-making tools, and sensing during Industry 4.0 [90]. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the DT for manufacturing processes has experienced considerable technological advancement over the last four decades [44]. The utilization of DTs can help manufacturers improve customer satisfaction by better understanding their demands, generating changes to existing products, operations, and services, and driving new business innovation [91]. The manufacturing industry can lead to the transition from reactive to predictive by leveraging the capabilities of the DT. They can learn to redesign the apparatus to make it more efficient and extend its useful life, as well as foresee when it will break down and when repairs would be necessary.

Several state-of-the-art manufacturing works presented earlier highlight the importance of continuous interaction, convergence, and self-adaptation of the DT to ensure full synchronization between the physical and its digital twin. This synchronization is necessary for constant surveillance, optimizations, and predictive maintenance processes to mention some. The notion of a CPS governing a specific manufacturing organization, with the goal of managing and optimizing all machinery and equipment operations via the interconnection of DTs, was described by Lee et al. [92] in the background of maximizing manufacturing efficiency. In this regard, a DT (of equipment and/or machinery) is defined as a “coupled model that operates in the cloud platform and simulates the health condition with an integrated knowledge from both data driven analytical algorithms and other available physical knowledge.” Sensing, storing, synchronizing, synthesizing, and servicing are the five pillars of the DT model. The advantages of a Big Data-Driven Smart manufacturing (BDD-SM) strategy using DTs were described by Qi et al. [79]. BDD-SM makes use of sensors and the IoT to generate and transmit large amounts of data. Cloud-based AI applications and BDA can be executed on these data to track processes, detect failures, and determine the best possible solution. In contrast, DT technology allows manufacturers to handle real-time and two-way mappings between real objects and virtual representations, resulting in an “intelligent, predictive, prescriptive” strategy that targets monitoring, optimization, and self-healing. Typical DT-based industrial information integration system design in smart manufacturing enabled by the IoTs is depicted in Fig. 7 [93]. As depicted in Fig. 7, the digital virtual body resides primarily in the cloud platform layer, while its control-oriented dimension model is set up in the edge layer to take part in real-time control. The industrial internet is made up of four layers: the field layer, the edge layer, the platform layer, and the application layer. The time dimension of the processes of design, production, operation, and maintenance is considered alongside these layers to examine the potential applications of DT.

Figure 7: Structure of a typical industrial information integration system in smart manufacturing with DT and IIoT support [93]

Various maintenance strategies are available for determining when and what maintenance activities should be undertaken. These strategies encompass reactive maintenance, preventive maintenance, condition-based maintenance, predictive maintenance, and prescriptive maintenance [64]. Conventional maintenance approaches rely on practical knowledge and addressing worst-case situations rather than tailoring strategies to the specific characteristics of materials, structural design, and usage patterns of each individual product. This makes these methods more reactive than proactive [31].

Conversely, DT technology has the ability to predict defects and damages in manufacturing machines or systems. This allows for proactive scheduling of product maintenance. DT simulates various scenarios and identifies optimal solutions and maintenance strategies, streamlining the overall maintenance process. Predictive maintenance is the most commonly employed approach. It involves planned corrective maintenance that is scheduled for convenience, with a primary focus on the system’s performance. Furthermore, the continuous transfer of information between DT and its physical counterpart enables ongoing validation and optimization of the system’s processes [21]. Early fault detection and diagnosis (EFDD) constitutes a crucial element within predictive maintenance, allowing facility managers to proactively address issues and prevent costly repairs or replacements. The methods for fault detection and diagnosis can be categorized into three groups: knowledge-based, analytical-based, and data-driven methods [94–96]. Knowledge-based methods utilize expert knowledge and rules for fault detection and decision-making. Conversely, analytical-based methods rely on mathematical models and physical laws to identify faults in building systems. Data-driven methods leverage statistical analysis and ML algorithms to detect faults by identifying patterns and anomalies in data. The integration of DT technology enhances EFDD through real-time monitoring of components and systems, facilitating predictive maintenance, and improving communication and collaboration among stakeholders. Furthermore, advancements in simulation experiences, such as extended reality technology, present opportunities to enhance predictive capabilities within the realm of DT. The predominant maintenance strategy among the top three sectors, namely manufacturing, energy industry, and aerospace, is predictive maintenance. Additionally, examples of prescriptive maintenance, based on DT technology, are only observed in the manufacturing and energy industry sectors.

5.4 DT in Resource Management and Supply Chain

Increasing cooperation amongst stakeholders, management authorities, expert teams, and ground workers to actively monitor a facility’s output and provide feedback when needed is another important function of DT [97]. This collaboration allows data scientists, field engineers, designers, and product managers to acquire a deep comprehension of the intricate operations within a production plant [98]. Furthermore, it helps to enhance the understanding of operational knowledge, which facilitates the design of novel prototype systems and their efficient testing. For instance, ThyssenKrupp, a prominent elevator manufacturer, partnered with Microsoft and Willow to develop an intelligent cloud-enabled DT model for a 246-m innovation test tower in Rottweil, Germany. Data collected from numerous sensors strategically placed throughout the building is compiled to create a digital representation of the structure in the cloud. This offers a distinctive visual perspective for real-time asset and resource management [99]. The continuous increase in supply chain expenses has repercussions for the profitability of all involved parties. Consequently, manufacturers, retailers, and distributors view the reduction of supply chain costs as essential. Furthermore, achieving outstanding performance in the supply chain holds strategic significance, potentially resulting in swift financial returns, often seen within months, along with enhancements in productivity and overall profits [100]. DT technology emerges as a solution to address supply chain challenges, encompassing aspects like packaging effectiveness, fleet management, and route optimization [101]. Moreover, DTs play a crucial role in enhancing just-in-time or just-in-sequence production processes and analyzing the efficiency of distribution routes. The technology extends its utility to various essential stages in supply chain management, encompassing the conceptualization of products, their development, and the subsequent distribution. It proves invaluable in optimizing production schedules, evaluating logistical strategies, and facilitating key aspects such as product development, product inception, and efficient distribution within the broader supply chain ecosystem [102].

An Intelligent DT (IDT) is an advanced version of the traditional DT. It has all the features of a DT, but it also has the ability to observe its physical surrounding environment and analyze and learn from it. This allows for the adaptation of existing models or adjustments based on the real asset’s interactions with its environment [103]. The implemented intelligent modular production system, utilizing the IDT, allows the system to respond automatically to new customer demands for novel products. This is achieved through the automatic generation of a new control code based solely on the analysis of environmental parameters, which means that the IDT can autonomously control and configure the actual system without any manual intervention.

Nowadays, advanced warehousing and logistics systems exhibit distinct features, including intricate operational processes, a heightened pace of activities, and significant labor intensity, particularly in complex work environments. Notably, to meet the rising customer expectations for fresh food and refrigerated medicine, the cold storage service plays a crucial role in maintaining strict environmental control over inventory. Consequently, there is a heightened focus on the safety of operators due to the inherent risks to human health posed by extreme working conditions, such as cold or confined spaces. In [104], a tracking framework for managing operator safety, enabled by IoT and DT technology, was introduced. The synchronization of the physical and cyber worlds is facilitated through the crucial attributes of time and space. A series of DT models for indoor safety tracking has been created. These models are designed to identify abnormal motionless behavior and implement self-learning genetic positioning. They are utilized to monitor the status of operators and provide accurate information on their precise indoor location. Managing and responding to the diverse statuses and locations of operators within a scenario poses a challenge for the management level. To achieve real-time visibility and traceability, the DT concept has been seamlessly integrated into the design and development of the framework. Physical assets, including personnel, machinery, and materials, are treated as tangible entities. Corresponding digital entities are then generated as digital representations of these physical assets, using real-time field data collected through IoT devices and services. Any change in the location or status of a physical entity is promptly mirrored in the digital representation within the cyber realm. For instance, an operator’s movement from point A to point B is visually depicted as a marked transition on the digital location map. Furthermore, alterations in the operator’s health status are represented through color changes in the digital twin. The abundant data generated by IoT devices is supported, while IoT services contribute to the analysis of these data. Edge IoT gateways, strategically deployed at various locations, facilitate the transmission of data to the cyber world for informed decision making.

Cybersecurity in the integration of IIoT with DT involves safeguarding data and ensuring the integrity, confidentiality, and availability of information exchanged between physical assets and their digital counterparts [105]. DT data is both delay-sensitive and mission-critical. In the Internet of Digital Twins (IoDT), this data needs to flow through various networks, software, and applications during its lifecycle to enable service delivery. As a result, ensuring end-to-end security and establishing trust throughout the entire process becomes a significant challenge. The swift expansion of the IIoT has occurred simultaneously with the rise of cyber threats targeting critical infrastructure, such as smart factories and grids [106]. Malicious actors now employ sophisticated techniques and tools, like Denial of Service (DoS), Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), firmware alteration, Man-in-the-Middle (MitM), and false code injection, allowing them to gain full control over IIoT infrastructure [107]. In addressing these security challenges, technologies such as blockchain and ML have been shown to be effective. ML, as applied in the detection of attacks in web applications, can be adapted to detect anomalies in DT environments. Furthermore, integrating knowledge graphs improves explainability, helping to identify and understand potential threats more effectively [108]. These methods demonstrate the critical role of advanced detection mechanisms in the protection of industrial systems. In addition, building a strong cybersecurity foundation, as described in the cybersecurity education frameworks [109,110], ensures that personnel are prepared to handle evolving threats. The blockchain employs cryptographic hashing algorithms and distributed consensus protocols to facilitate secure data transfer [111]. Within the context of DTs, blockchain’s distributed ledgers contribute to the auditability, accessibility, and traceability of design data. The encrypted DT data stored in the ledger remains unalterable and beyond the control of any central authority. This feature not only ensures unmatched levels of confidence and data integrity but also enhances the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the DT audit process [2].

In [112], an innovative IIoT network empowered by DT technology was introduced. The system model outlined encompasses IIoT devices, edge servers, and cloud servers. In the realm of DT-enabled IIoT systems, they devised a comprehensive framework integrating blockchain and deep learning. This framework ensures data privacy and secure data communication. The ENIGMA approach uses gamification and explainable AI to evaluate DT security and train analysts. It offers a controlled virtual environment where analysts can practice detecting and responding to threats [113]. In wireless networks, DTs are susceptible to attacks, requiring security solutions such as Stackelberg game-based models for anti-jamming and residual-enabled reweighting aggregation methods to improve training resilience against incorrect parameters [114]. These approaches reflect ongoing efforts to address security challenges in DT applications in different fields.

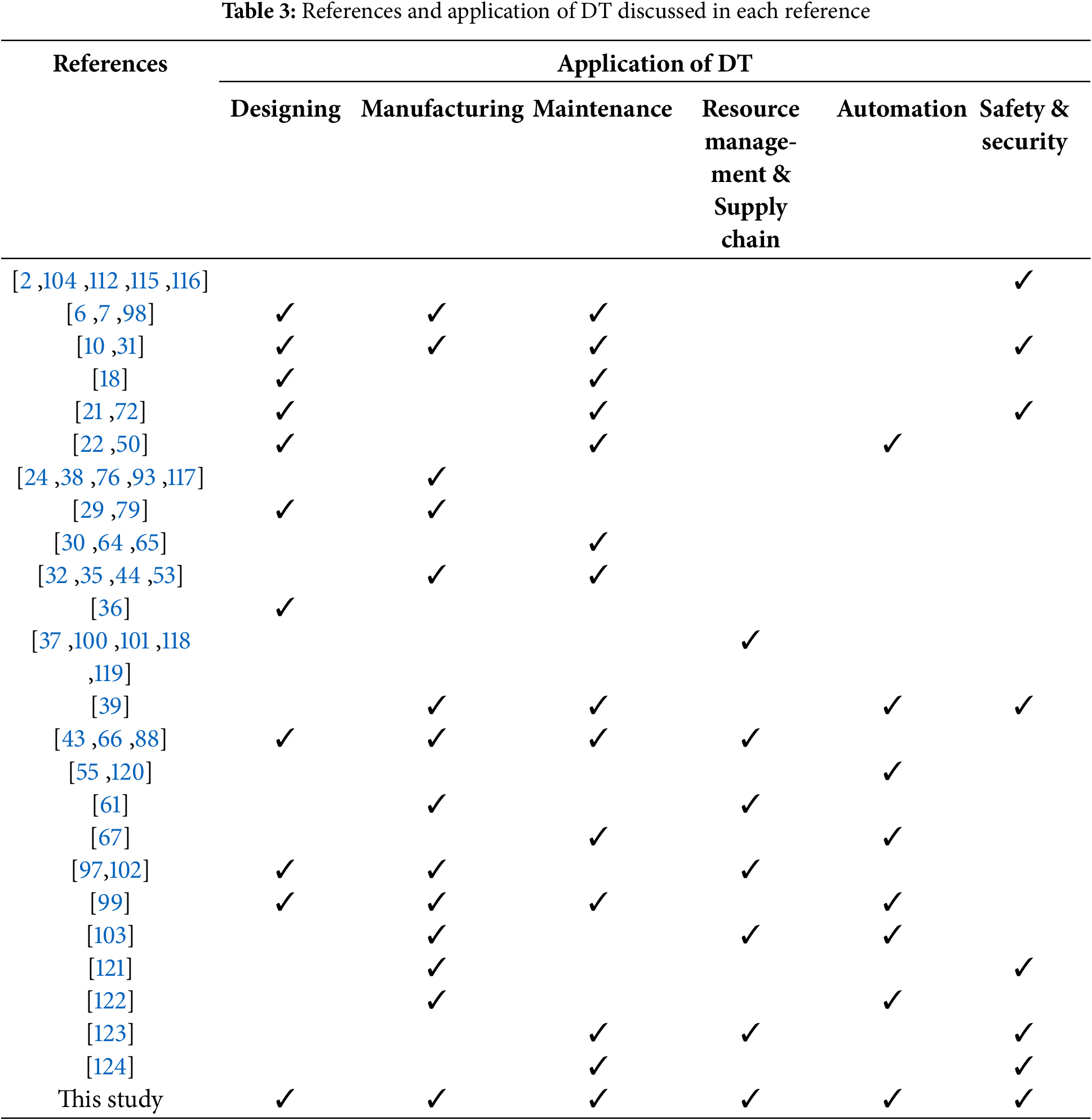

To sum up the key points discussed in this section, we have incorporated Fig. 8 and Table 3. Fig. 8 lists the contribution of DT in each area that offers insight into how DT improves processes such as design, manufacturing, and more. Out of the 142 references we reviewed, we identified and tabulated those discussing the application of DTs relevant to our criteria. Specifically, 54 references fell under the major areas we examined, with most papers addressing more than one application area, whereas our paper discusses all the application areas. The references and the applications discussed in each are presented in Table 3.

Figure 8: Application of DT in various domain of Industry

The following section presents a case study detailing the implementation of a DT prototype within a smart factory environment.

6 Case Study: Implementation of a Real-Time DT System in a Smart Manufacturing Environment

The advancement of smart manufacturing relies heavily on digital transformation technologies, with DTs playing a critical role. This case study examines a real-world implementation of a cost-effective, real-time DT system within a smart factory. The proposed DT system for a smart factory utilizes Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) and Open Platform Communication Unified Architecture (OPC UA) protocols to achieve seamless data integration, synchronization, and visualization between physical and digital environments. The primary objectives of the study were to design a practical DT system capable of real-time monitoring and control, address common challenges such as heterogeneous data formats, high system costs, and limited scalability, and provide a cost-effective, scalable, and accessible solution for small and medium-sized manufacturers.

The implementation was structured around three key layers:

• Physical Space Layer: Real-time data collection from programmable logic controllers (PLCs), robots, and sensors through edge computing systems.

• Communication Layer: MQTT was employed for lightweight, real-time data transmission, while OPC UA facilitated standardized communication between diverse manufacturing devices.

• Digital Space Layer: Integration of machine and human DTs allowed real-time 3D visualization and monitoring via a web-based platform powered by WebGL.

Figs. 9 and 10 illustrate the DT factory system configuration and the digital monitoring dashboard, respectively. The system was implemented in a test environment, using PLCs from two manufacturers (LS and Mitsubishi), edge computers running Ubuntu for data collection and preprocessing, and web-based dashboards for high-resolution visualization powered by WebGL. Real-time collaboration tools using WebRTC enabled multiparty communication. The system’ s performance was evaluated using several metrics:

• Data Collection Rate: Achieved an average transmission latency of 12.40 ms, ensuring real-time responsiveness.

• Interoperability: Successfully converted data from heterogeneous PLCs into OPC UA format, demonstrating the ability to integrate diverse devices.

• Visualization Performance: Maintained an average frame rate of 124.99 fps, enabling smooth and high-quality visualization.

• Collaboration: Achieved a multiparty video and audio synchronization latency of 13.3 ms, facilitating real-time communication and decision-making.

Figure 9: DT factory system configuration [125]

Figure 10: DT factory digital monitoring dashboard [125]

The implementation highlights several strengths:

• Cost-Effectiveness: Lightweight protocols and web-based platforms minimized hardware costs.

• Scalability: The modular architecture supported the seamless integration of additional devices and systems.

• Accessibility: The web-based interface enabled remote monitoring and control across multiple devices.

However, the study also identified limitations. Integration with a broader range of PLC brands was not explored, limiting the findings’ generalizability to manufacturing environments with diverse equipment. Additionally, advanced features, such as AI-driven anomaly detection and optimization algorithms, were not incorporated, which could enhance the system’s capabilities for predictive maintenance and process optimization.

The case study demonstrates that implementing a DT system requires significant initial investment in hardware, software, and integration processes. For example, the edge computer played a crucial role in enabling real-time data collection, achieving an average transmission latency of 12.40 ms. However, this necessitated investment in robust computing hardware and reliable network infrastructure, such as MQTT for efficient data transmission. The conversion of heterogeneous PLC data to a standardized OPC UA protocol required integration tools to ensure seamless communication between diverse devices, adding to the implementation cost. The use of Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) scanning and Unity for creating 3D models and digital factories is another cost-intensive aspect. LiDAR technology facilitated precise digital mapping of physical spaces, while Unity software enabled immersive environment development. These tools, while enhancing accuracy and visualization, required specialized expertise and software licenses, further contributing to the overall cost. Additionally, training operators to interact with WebGL-based dashboards introduced further costs, as users needed to familiarize themselves with the digital interface. Despite these initial costs, the long-term benefits are significant. Interoperability achieved through standardized communication protocols reduces reliance on proprietary solutions, while real-time data collection and visualization minimize downtime and operational disruptions. These efficiencies translate into measurable cost savings over time, particularly through reduced maintenance costs and improved productivity.

The scalability of the DT system is evident in its ability to integrate diverse devices and manage increasing data volumes without compromising performance. The use of edge computing ensured distributed processing, reducing the load on central servers and enabling effective scaling as additional devices and data points were incorporated. For example, the edge computer’s efficient data collection from multiple devices demonstrated its capability to support larger manufacturing setups or expand across multiple factory locations. The successful conversion of heterogeneous PLC data into OPC UA format underscored the system’s flexibility to accommodate new equipment without extensive modifications. The WebGL-based real-time visualization tool, with a frame rate of 124.99 fps, ensured consistent performance across user locations, making the system suitable for geographically distributed teams. Furthermore, WebRTC-enabled multiparty video and audio synchronization facilitated real-time collaboration for larger groups.

While the case study demonstrates scalability and cost-effectiveness, several challenges remain. Scaling the system to larger factories or multi-factory operations may strain computational and network resources, necessitating costly infrastructure upgrades. Maintaining accurate digital representations over time requires frequent updates to account for physical changes, which can be resource-intensive and costly in dynamic environments. While OPC UA facilitates interoperability, integrating new or legacy devices may still demand additional customization, driving up costs. Real-time collaboration tools like WebRTC, though effective for smaller-scale implementations, may face latency and performance issues as the number of users or their geographic distribution increases, requiring further network enhancements. Additionally, growing data complexity increases computational demands on edge devices, necessitating investment in more advanced hardware. The system’s increased connectivity and expansion also expose vulnerabilities, posing cybersecurity risks during data transmission and real-time collaboration. These challenges underscore the importance of strategic planning and targeted investment to ensure that DT systems remain scalable and cost-efficient in real-world applications.

7 Challenges and Considerations

As DTs continue to gain traction in industrial environments, researchers and practitioners alike are confronted with a myriad of challenges that must be addressed to fully realize their potential. From the complexities of integrating DT into existing industrial processes to the need for robust data privacy and security measures, the journey towards seamless DT adoption is marked by hurdles that require careful consideration and innovative solutions. This section delves into the current research problems and challenges surrounding the implementation and utilization of DT in industrial settings, shedding light on the critical areas that demand further exploration and development.

7.1 Investments in Infrastructure

On one side, embracing developing trends in technology like DTs, IoT, blockchains, etc., proves beneficial in lowering operational costs and achieving heightened efficiency of operation. Conversely, companies must allocate substantial capital for ongoing expenses related to the day-to-day management of networked devices (which may be distributed geographically) and training staff in the use of applied tools and knowledge required for data modeling. These practices could strain operational resources dedicated to managing industry assets and business processes, necessitating a delicate balance in the expense-profit analysis.

While acknowledging the significance of DTs, many businesses concede that it is economically challenging to acquire the necessary connectivity, processing capacity, storage, and bandwidth to manage the vast amounts of data essential for creating DTs. Similarly, in the context of blockchain technology, the high initial implementation costs, perceived risks associated with relatively emerging technology, and the potential disruption to existing practices present a substantial obstacle for enterprises, prompting the need for open-ended discussions.

7.2 Precise Depiction of Digital Traces

A significant obstacle facing a virtual model emulating real-world scenarios is the achievement of a high degree of accuracy. In manufacturing settings, the optimal DT (for instance, representing a robotic arm) should precisely reflect all properties and roles of the physical component, remaining synchronized in real-time throughout its operational life. However, the challenge lies in accurately modeling DTs, given the variability, vagueness, and uncertainty inherent in physical space, making it an ongoing and unresolved concern [126]. Real-time communication between physical systems and DTs is often hindered by data latency and bandwidth limitations, particularly in IIoT environments. Edge computing and 5G networks offer promising solutions by processing data closer to its source, significantly reducing latency and enhancing synchronization [127,128]. These technologies enable faster and more efficient communication, critical for maintaining real-time updates. Another major issue is ensuring data consistency when integrating information from various sources such as IoT sensors, enterprise systems, and cloud platforms. Inconsistent or conflicting data can disrupt synchronization. Robust data integration frameworks that standardize and harmonize information from multiple sources, alongside blockchain technologies to ensure data immutability, provide effective solutions [129]. These approaches improve data reliability, which is essential for seamless DT operation. Furthermore, efficient synchronization algorithms are necessary to handle high-frequency updates without overwhelming computational resources. Advanced ML techniques, such as reinforcement learning and predictive analytics, can optimize synchronization processes by predicting updates and reducing computational loads [130]. These methods not only improve accuracy but also enhance system efficiency. As DT systems scale up, they face additional challenges due to the increasing volume of data. Scalable cloud-based platforms with dynamic resource allocation offer an effective solution to manage these larger datasets while maintaining synchronization [131]. These platforms ensure that even as systems grow, real-time performance is not compromised. By integrating these solutions, edge computing, blockchain, ML, and scalable cloud platforms, the challenges of real-time synchronization can be effectively addressed. These advances improve the reliability and applicability of DT systems, paving the way for broader adoption in IIoT environments

7.3 Standardization Challenges

Standardization in Industry 5.0 involves the creation and implementation of uniform standards for planning, developing, and managing industrial systems and processes. This is vital to ensure interoperability, cost efficiency, and enhanced productivity in industrial operations. Organizations such as the International Society of Automation (ISA) and the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) play a pivotal role in establishing these standards. ISA, for instance, focuses on enhancing safety, simplifying component integration, and providing robust instrumentation standards, such as ISA18 for alarm systems and ISA12 for hazardous environment equipment. Similarly, ANSI collaborates with ISA to develop standards for industrial control systems, thereby fostering operational excellence [132].

Germany’s strong emphasis on manufacturing standards, particularly through ISO certifications such as ISO 9001 (Quality Management Systems) and ISO 14001 (Environmental Management Systems), further underscores the importance of quality control and sustainability in global industrial operations. However, these standards also highlight the challenges of ensuring widespread adoption in industries and regions [71].

A significant barrier to standardization arises from industry competition, which discourages companies from sharing models and frameworks with rivals. This dynamic results in a market where prominent companies such as General Electric, Siemens, and International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) play a leading role in the development and adoption of DT technologies. Additionally, the lack of collaboration between industry and academia exacerbates the issue, as it inhibits communication and knowledge sharing among experts. The fragmentation of data ownership, disparate data types, and challenges related to patenting and proprietary knowledge further limit accessibility and integration [133].

The integration of emerging technologies such as blockchain into industrial systems introduces additional standardization challenges. Blockchain networks, while fundamentally based on decentralized peer-to-peer (P2P) architectures, vary significantly in their data structures, scalability solutions, and consensus mechanisms. Non-interoperable blockchain implementations lead to fragmented industrial ecosystems, siloed networks, and limited information flow. Addressing these issues requires prioritizing the seamless integration of data across diverse blockchains to encourage adoption and innovation. Efforts by organizations such as the International Telecommunications Union (ITU-T), the Enterprise Ethereum Alliance, the ISO, and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) are critical in bridging these gaps.

To mitigate these challenges, there is a pressing need for platforms managed by government or private organizations to establish unified standards for data and model governance, ownership, and openness. Such initiatives would enable industries to overcome existing barriers, fostering a more collaborative, efficient, and sustainable industrial ecosystem.