Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Plant Disease Detection and Classification Using Hybrid Model Based on Convolutional Auto Encoder and Convolutional Neural Network

1 Computer Science & Engineering Department, Jai Parkash Mukand Lal Innovative Engineering & Technology Institute, Radaur, Yamunanagar, 135133, India

2 Department of Computer Science, Government PG College, Ambala Cantt, Ambala, 134003, India

3 School of Computer Science & Engineering, Galgotias University, Greater Noida, 203201, India

4 Department of Computer Science and Applications, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, 136118, India

5 Computer Science Department, Bay Campus Fabian Way, Swansea University, Swansea, SA1 8EN, UK

6 Department of Engineering and Technology, Gurugram University, Gurugram, 122003, India

7 Department of CSE, Panipat Institute of Engineering and Technology, Panipat, 132103, India

* Corresponding Authors: Purushottam Sharma. Email: ; Xiaochun Cheng. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 5219-5234. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.062010

Received 08 December 2024; Accepted 07 April 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

During its growth stage, the plant is exposed to various diseases. Detection and early detection of crop diseases is a major challenge in the horticulture industry. Crop infections can harm total crop yield and reduce farmers’ income if not identified early. Today’s approved method involves a professional plant pathologist to diagnose the disease by visual inspection of the afflicted plant leaves. This is an excellent use case for Community Assessment and Treatment Services (CATS) due to the lengthy manual disease diagnosis process and the accuracy of identification is directly proportional to the skills of pathologists. An alternative to conventional Machine Learning (ML) methods, which require manual identification of parameters for exact results, is to develop a prototype that can be classified without pre-processing. To automatically diagnose tomato leaf disease, this research proposes a hybrid model using the Convolutional Auto-Encoders (CAE) network and the CNN-based deep learning architecture of DenseNet. To date, none of the modern systems described in this paper have a combined model based on DenseNet, CAE, and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to diagnose the ailments of tomato leaves automatically. The models were trained on a dataset obtained from the Plant Village repository. The dataset consisted of 9920 tomato leaves, and the model-to-model accuracy ratio was 98.35%. Unlike other approaches discussed in this paper, this hybrid strategy requires fewer training components. Therefore, the training time to classify plant diseases with the trained algorithm, as well as the training time to automatically detect the ailments of tomato leaves, is significantly reduced.Keywords

India is among the greatest agricultural nations in the world. Agriculture contributes 16% to the country’s gross domestic product and accounts for 10% of its total exports. Whether directly or indirectly, more than 75% of India’s population is employed in agriculture. When a plant disease lacks obvious signs, it is necessary to apply cutting-edge analysis techniques [1]. Most plant illnesses do, however, exhibit visible symptoms, and the standard method for diagnosing plant diseases today involves a skilled crop pathologist observing illness optically on diseased plant leaves. Agronomists can benefit greatly from the availability of knowledgeable as well as smart technologies that identify the illness accurately on their own. On the other hand, giving farmers who lack access to agronomic and psychopathological support infrastructure an arrangement with straightforward smartphone software that even novice agriculturalists can utilize is also a commendable accomplishment [2]. The development of artificial intelligence technology has made it possible to create automated systems that can identify illnesses more rapidly and precisely. Using Support Vector Machines (SVM), reference [3] investigated the early detection and classification of illnesses observed in sugar beets. In the search for five distinct leaf disorders, the author in [4] employed Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) to categorize those regions after completing the extraction of features based on texture and color. They segmented the affected regions by grouping the attributes gathered from the pre-processing methods using K-Means. A method to identify six different forms of diseases visible on cotton leaves was proposed by Revathi and Hemalatha [5]. Their suggested approach uses Particle Swarm Optimization to accomplish feature selection from a feature vector that includes edge, color, and texture-based data gathered through image processing to categorize the condition.

The extraction of features, a difficult process that directly affects classification performance, is necessary for machine learning (ML) classification. Since “Graphics Processing Units (GPUs)” and “Central Processor Units (CPUs)” have become more powerful and fast, deep learning architectures were possible due to the invention of new effective techniques that can manage actual data with no requirement for handmade attributes [6]. By processing enormous amounts of input, deep neural network topologies having numerous neurons and extracting layers may effectively complete complicated jobs like picture and speech identification [7]. These methods make use of “Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)” as well as their numerous varieties, including “Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)” and “Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)”, to find hidden patterns in data. A separate module to extract features is not required as a variety of features are inevitably extracted from raw data. Second, deep learning approaches shorten the time needed to handle big datasets with lots of dimensions [8]. The proposed hybrid model is therefore constructed using Deep Learning (DL) techniques. The author has used the PlantVillage dataset to train 9-layer CNN architecture with varying epochs, batch sizes, and dropout rates. They then compared the performance of the developed models to well-known transfer learning strategies [9]. Their proposed prototype had 96.46% classification accuracy on the testing data. Apart from that, there are two more types of research on different datasets that have been augmented with additional photos, such as the PlantVillage dataset. In one of them, Ferentinos used 87,848 pictures and the AlexNet, GoogLeNet, and VGG architectures to classify 58 distinct diseases affecting 25 different plant species. Deep learning architectures are increasingly being employed in the literature to diagnose plant leaf diseases, as evidenced by the previously mentioned publications [10,11]. Nonetheless, further research is necessary in several areas concerning the use of novel DL models, especially in the identification of plant leaf diseases. In particular, inevitably, efficient prototypes with fewer limitations, faster training times, and no performance modifications will be used. Due to their efficiency on image data, a pre-trained CNN model named DenseNet-121 and Convolutional Auto-Encoders (CAEs), two Deep Learning approaches, are employed in numerous computer vision applications. Both of these methods extract numerous structural and chronological information from picture data using convolutional operations. While CAEs work to effectively decrease an image’s proportions, CNN-based DenseNet-121 is used to categorize input images into the appropriate classifications. In contrast to existing cutting-edge systems described in the literature, this work offers a fresh hybrid prototype for autonomous crop ailment diagnosis based on CAE as well as DenseNet-121 using fewer training constraints. To the best of our knowledge, no research study has yet developed a composite CAE model integrated through a CNN-based DenseNet-121 model, although there are numerous methodologies for automatic plant disease identification that are current in the literature. The result is less efficient using CAE. The projected composite prototype is utilized to identify the biotic ailment in tomato crops. This technology may be employed to identify other plant diseases.

The remaining research is structured as follows: In Section 2, a quick summary of the research for detecting ailment in plants using various DL techniques is presented. The architecture of the suggested model for identifying plant diseases from infected leaves is discussed in Section 3. Section 4 presents the result of the Hybrid CNN model, and Section 5 concludes the work.

As early as the 1990s, information technology was utilized by several scholars to recognize as well as diagnose crop ailments. Numerous researchers across the globe studied several Deep Learning, Machine Learning (ML), and Image Processing methodologies to automate plant disease diagnosis. This section describes new methods reported in the literature for automatic identification of plant diseases. By using five different CNN architectures, reference [12] created a device to detect banana crop diseases. ResNet-18, VGG-16, ResNet-152, InceptionV3, and ResNet-50 were the designs in question. ResNet-152 was discovered to be 99.2% more precise than its rivals. In addition, they created a mobile application that enables producers to upload leaf images of banana plants, thus enabling the application to quickly detect any problems that may be present. The smartphone application predicted maladies utilizing the InceptionV3 model with a 99% accuracy rate. According to the ResNet article, their top-performing model, ResNet-152, utilized 60 million training parameters [13].

The study written by [14] contained additional work of a similar nature. They employed InceptionV3 and VGG-19 CNN architectures for autonomous illness detection in plants using the PlantVillage dataset. To artificially expand the set of data for the study, they also used data augmentation. With testing and training accuracy of 95% and 98%, respectively, the “VGG-19” model outperformed the “InceptionV3” model, according to their study. In their research, they reported in [15] that the VGG-19 model, which was their best-performing model, required 143 million training parameters.

On the PlantVillage dataset, reference [16] utilized several contemporary CNN techniques and various identifiers for independent crop illness detection. GoogLeNet CNN, VGG-16, and ResNet-50 were used by them for feature extraction. “Support Vector Machine (SVM)” and “K-Nearest Neighbor” classifiers were employed to classify the disease. They discovered that SVM with ResNet-50 outperformed the competition with 98% accuracy. The ResNet-50 model used around 25 million training constraints. There was also similar work done by [17]. For potato plants, they propose an automated structure to detect diseases. For feature extraction and disease identification, this system uses a variety of classifiers, including “K-Nearest Neighbor”, “Logistic Regression”, “Neural Network”, and “Support Vector Machine (SVM)” architectures from CNN, including InceptionV3, VGG-19, and VGG-16. Possessing 97.8% accuracy, they found that VGG-19 with Logistic Regression performed better than others. In [18], various CNN architectures are employed for the identification of tomato plants. It is simple to identify the method of system calculation and strength for identifying a virus in a growing stage.

The authors of [19] proposed a color fusion balancing approach to identify the damaged parts from under a clean environment and differing color studies. The color transformation technique is used in the first step. Second, the threshold technique is used to separate the undesirable image portion from the remaining leaf portion. Finally, the classification of photos using the cross-validation method has obtained 93.12% accuracy. To identify and classify illness in plant leaves, reference [20] combines DL models such as CNN with ML models such as Decision Tree, SVM, etc. The main difficulty in agriculture is the correct diagnosis of diseases, which cannot be done with the naked eye. Different ML and DL techniques were described to diagnose and classify leaf ailments in the context of image processing.

In [21], a useful Mask R-CNN (Mask Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks) customized for Deep Learning (DL) is suggested for the independent segmentation as well as identificationof leaf diseases in tomato crops. The deep learning technique of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) has previously proven to be one of the most effective methods for classifying images [22,23]. For ten prevalent rice ailments, the 10-fold cross-validation approach yielded an average diagnosis rate of 95.48%. Because of its superior speed and accuracy, the Faster R-CNN approach described by [24] seems suitable for rice disease identification. The Faster R-CNN was used to process the full leaf region to segment it. In [25], it suggested a “Deep Convolutional Encoder Network” system to identify seasonal agricultural diseases. They utilized CNN and Autoencoder to identify seasonal crop diseases. However, the new hybrid approach that is being presented is grounded on CNN as well as CAE. Additionally, the proposed model achieves greater testing accuracy than the model put forth. To automatically identify the disease in potatoes and plants, reference [26] developed a method by using SVM and CAE classifiers.

The researchers extracted corn and potato leaf images from the PlantVillage dataset, achieving disease identification accuracies of 87.01% and 80.42% for potato and maize plants, respectively. While deep learning architectures have demonstrated increasing promise for plant disease diagnosis, as evidenced by prior studies, several research gaps remain regarding the application of specialized DL architectures for leaf disease detection. A critical limitation observed in existing approaches is their reliance on excessive training parameters. This not only necessitates extended training durations but also demands substantial computational resources. To address these challenges, we propose an innovative hybrid model that significantly reduces parameter requirements while maintaining classification accuracy. Our framework employs a two-stage process: first, a Convolutional Auto-Encoder (CAE) reduces the dimensionality of input leaf images; subsequently, a lightweight CNN-based classifier performs disease identification. This approach yields two key advantages: (1) a substantial reduction in trainable parameters through preliminary dimensionality reduction, and (2) preserved classification performance despite the simplified architecture. Experimental results confirm that preprocessing leaf images through dimensional compression effectively optimizes the model’s computational efficiency without compromising diagnostic accuracy.

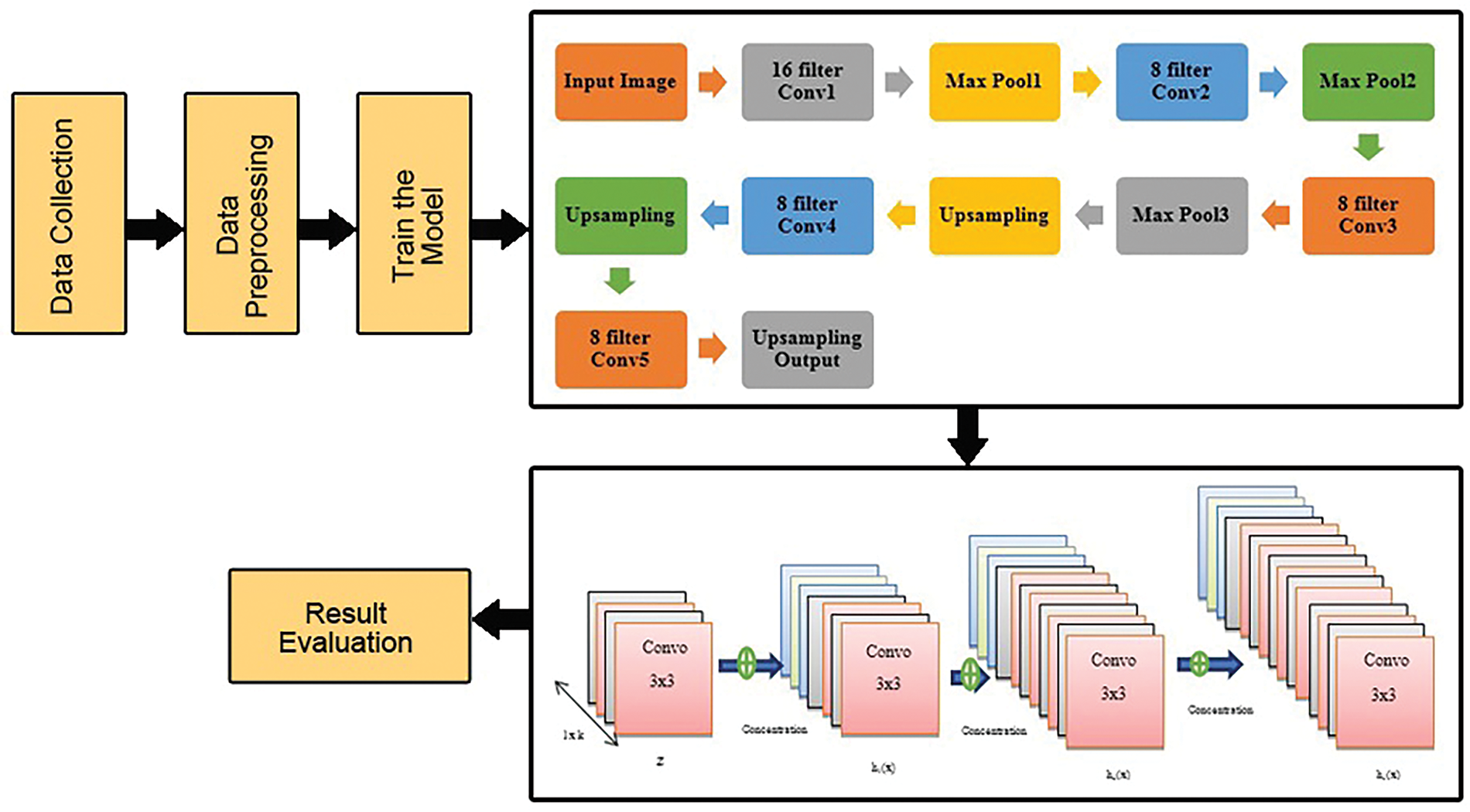

This section goes into detail on the methodology used in this paper. This discovery leads to the comparison of pre-trained multiclass classification models (ten classes of tomato leaves) [27] that have been tweaked using a combined collection of image data. The several steps that comprise the research process are depicted in Fig. 1. The subsequent sections contain a full breakdown of the recommended technique’s steps.

Figure 1: Dataflow architecture of proposed work

They input the data from the dataset and preprocessed the image. 70% of data have been used to train the model and the remaining 30% for testing. In this study, novel hybrid systems for the automatic detection of agricultural diseases were developed. To the best of our knowledge, no literature study has proposed a hybrid model that uses both CAE and DenseNet121 models to automatically detect crop diseases. This model employs the CAE and DenseNet121 deep learning techniques. The CAE network has first been trained to reduce the dimensionality of the input leaf pictures. The main components of the leaf photos were retained throughout the dimensionality reduction procedure.

3.1 Data Collection and Pre-Processing

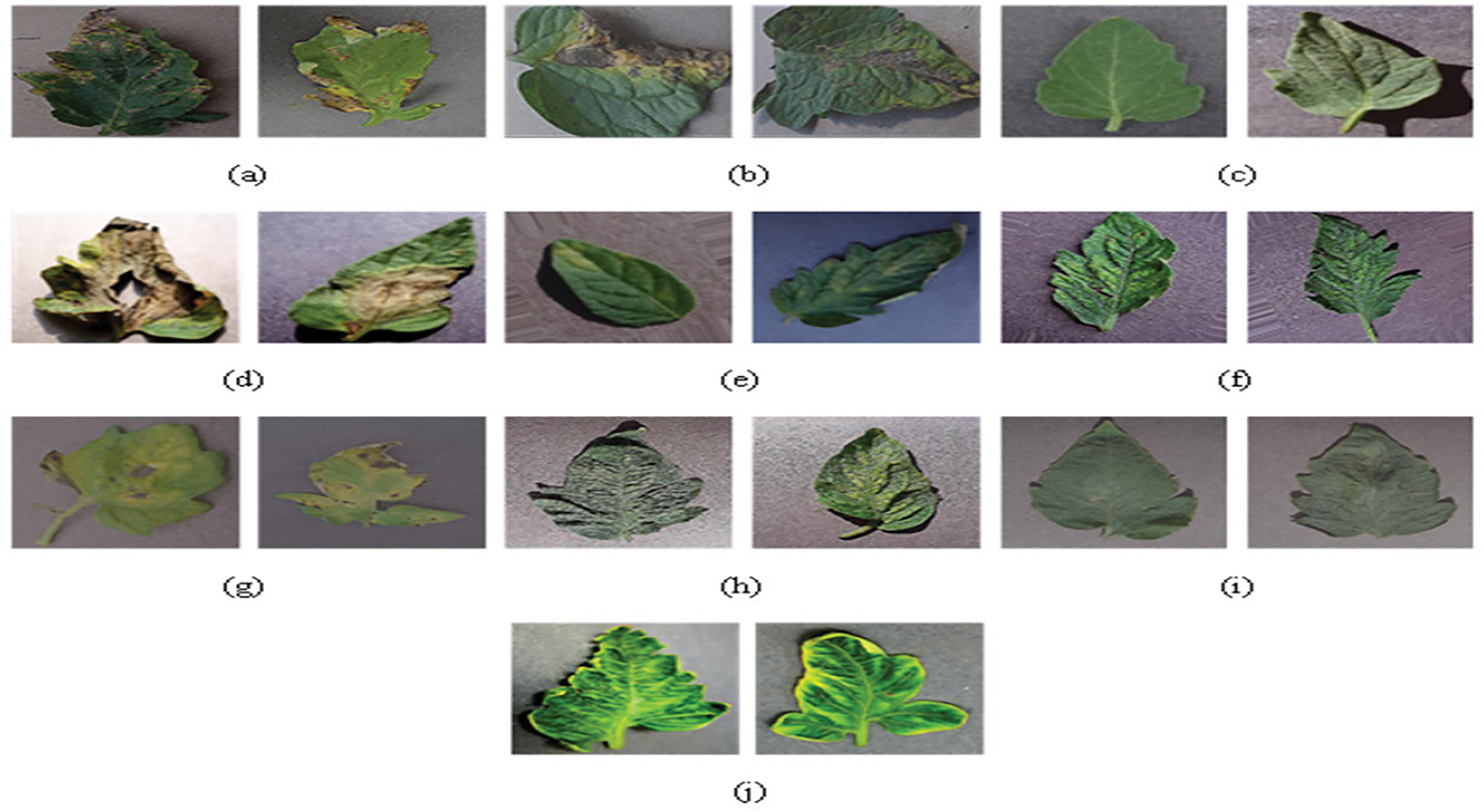

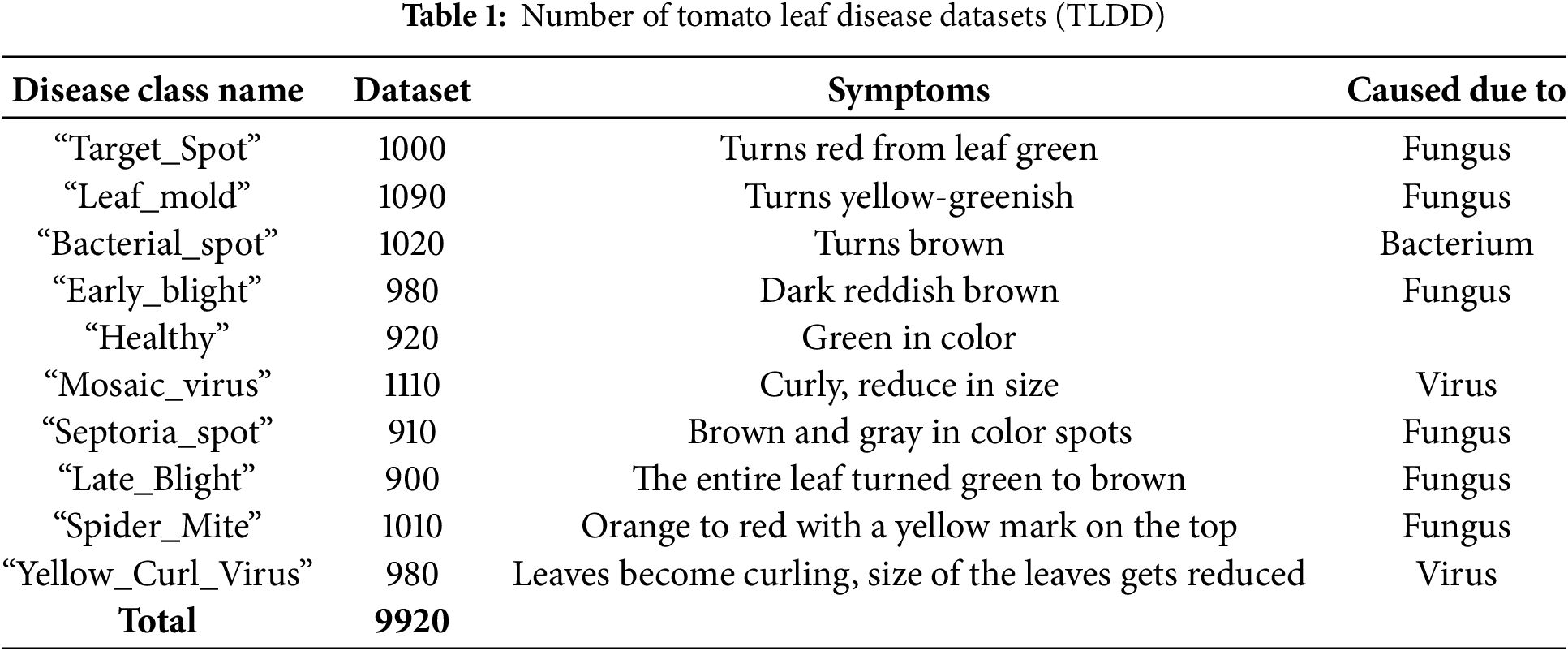

Plant Village provides high-resolution photos of tomato leaves that are used to assess performance [27]. Fig. 2 shows some typical pictures and Table 1 summarizes the amount of picture data extracted from the dataset containing the indications.

Figure 2: Sample of Images. Tomato leaf disease manifestation is influenced by multiple biotic and abiotic factors, including fungal/bacterial pathogens, insect infestations, and environmental conditions (e.g., moisture levels, and nutrient availability). Fig. 2 presents representative samples of our input image dataset, showcasing: (a) Target_Spot, (b) Leaf_mold, (c) Healthy, (d) Early_blight, (e) Bacterial_spot, (f) Mosaic_virus, (g) Septoria_spot, (h) Late_Blight, and (i,j) Spider_Mite infestations

For real-time detection systems, data quality assurance is paramount—any inaccuracies in the training dataset may significantly compromise model performance. We therefore established rigorous data collection protocols based on preliminary experimental results. The dataset was partitioned following standard machine learning practice, with an 80:20 training-to-testing split to ensure robust model evaluation.

After analyzing a range of data, it is only natural to have questions about using the information efficiently. It is well known that data gathered from any source can become contaminated by several elements, such as noise and human mistakes. If the algorithm uses such data directly, it can yield erroneous results. Thus, the next step is to preprocess the supplied data. Pre-processing data enhances its quality and removes or minimizes noise from the original input data, among other benefits. Among the pre-processing methods are scaling, color space change, noise reduction, and image enhancement. These techniques handle the class imbalance issue in the dataset. The leaf image is resized to

Even when trained on high-end GPU processors, the majority of contemporary models require days or weeks of training and fine-tuning. A substantial amount of time is required to both train and construct a model from the beginning. To illustrate, a CNN model constructed entirely from the ground up using a publicly accessible dataset of plant diseases achieved an accuracy of 63% after undergoing nearly half as many iterations as a CNN model constructed from the ground up using a 25% accuracy dataset and 200 iterations. There are numerous methods of transfer learning. Which one is utilized for classification is contingent on the dataset characteristics and the pre-trained network model in use.

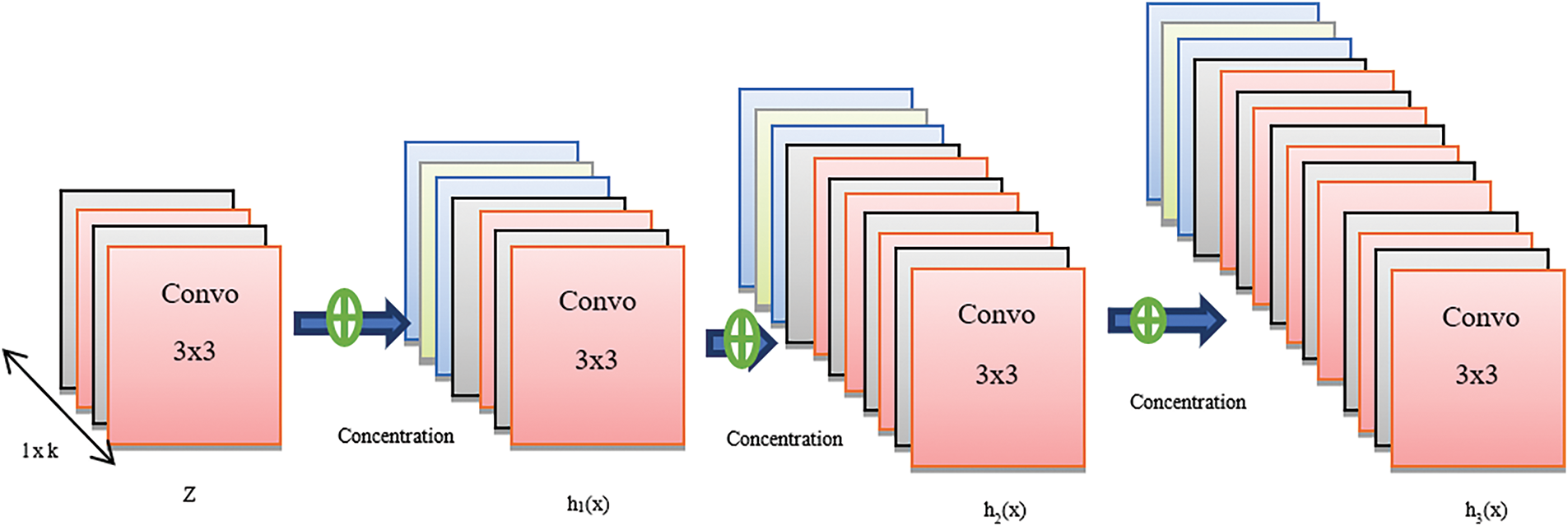

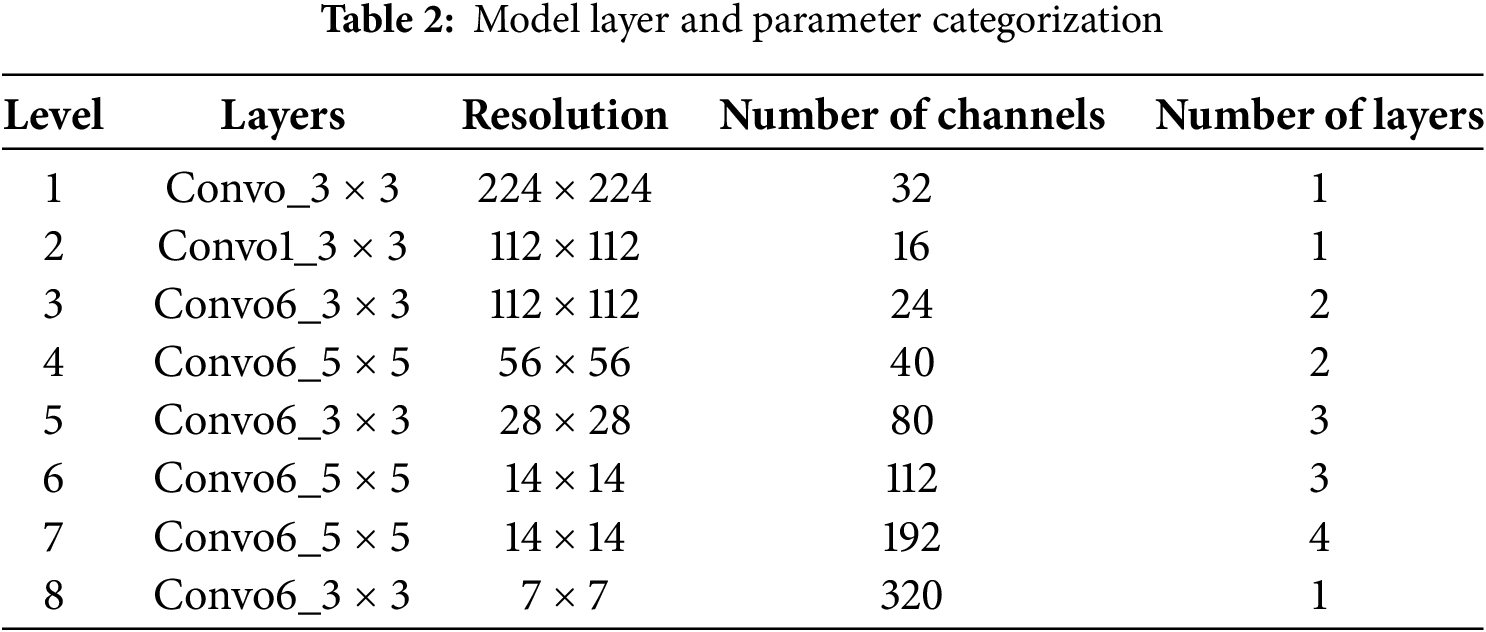

A deep CNN model specifically developed for image classification, DenseNet-121 [28] employs dense layers connected by shortened paths. As illustrated in Fig. 3, a dense block operates within a DenseNet application. Each composition layer generates k-channel feature maps. ReLu activation & convolution are utilized to regularize, convolve, and activate the output feature maps. The subsequent layers’ outputs are modified via batch normalization and pooling.

Figure 3: Architectural framework of DenseNet

There are numerous features and a significant gradient of flow in the strata. ResNet has a significantly larger footprint than DenseNet. Furthermore, the classifiers implemented in the traditional ConvNet model operate on intricate datasets, whereas DenseNet guarantees the inclusion of every feature, irrespective of the data’s complexity, and establishes seamless decision boundaries. The complete categorization of the model layer and parameters are given in Table 2.

Transfer learning [28] enables the effective transfer of knowledge acquired from solving one problem domain to facilitate learning in a different but related task or application domain. In deep neural networks, the initial layers typically learn general feature representations through training. The transfer learning paradigm allows for the removal of selected final layers from a pre-trained model and their replacement with task-specific layers optimized for the target application. Compared with training models from scratch, this approach offers significant advantages when leveraging models pre-trained on large-scale visual datasets, including: (1) reduced training time, and (2) enhanced model accuracy through the utilization of learned feature representations.

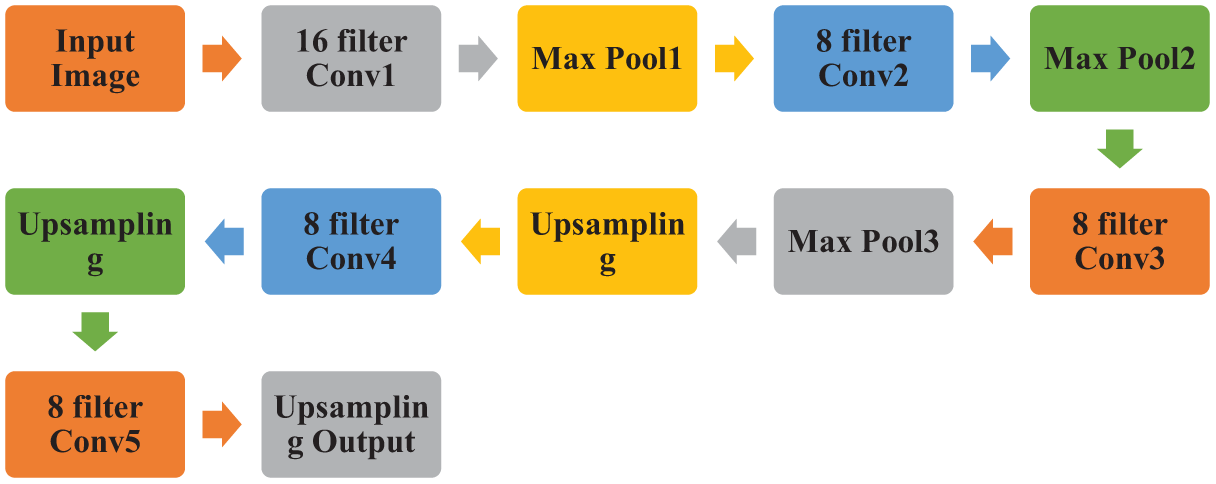

3.3 Convolutional Auto-Encoder (CAE)

A self-supervised learning system called Autoencoder employs a neural network to learn representations. A method for teaching a system to encode input data is called representation learning. Data input is mapped to a compressed domain representation or a lower-dimensional space using auto-encoders. To achieve this, a network bottleneck is established, forcing the structure to acquire the constricted domain depiction of the incoming data. The bottleneck Layer, Encoder Network, Reconstruction Loss, and Decoder Network are the four parts of an auto-encoder [29]. A neural network called an encoder network compresses input data before encoding it. The output of the encoder network’s bottleneck layer, the last layer, is encoded input data. Let’s assume that an encoder network has N layers, with the N-th layer serving as the bottleneck layer which is shown in Eq. (2).

where

where

Figure 4: CAE architecture based on the proposed hybrid model

The approach shrinks the proportions of the leaf pictures while preserving their key characteristics, which are then used for categorization. A substantial reduction in the number of elements occurs because of the compressed domain representation of leaf images. Additionally, the composite model requires less time for training and classification and has fewer training parameters.

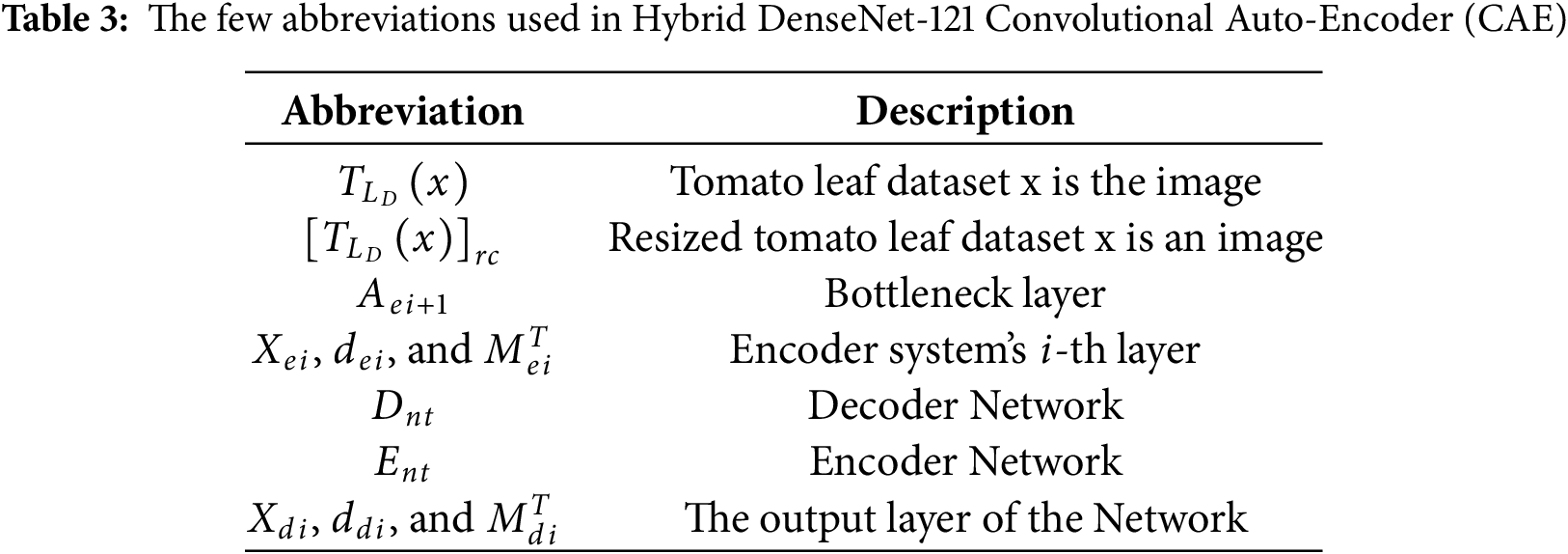

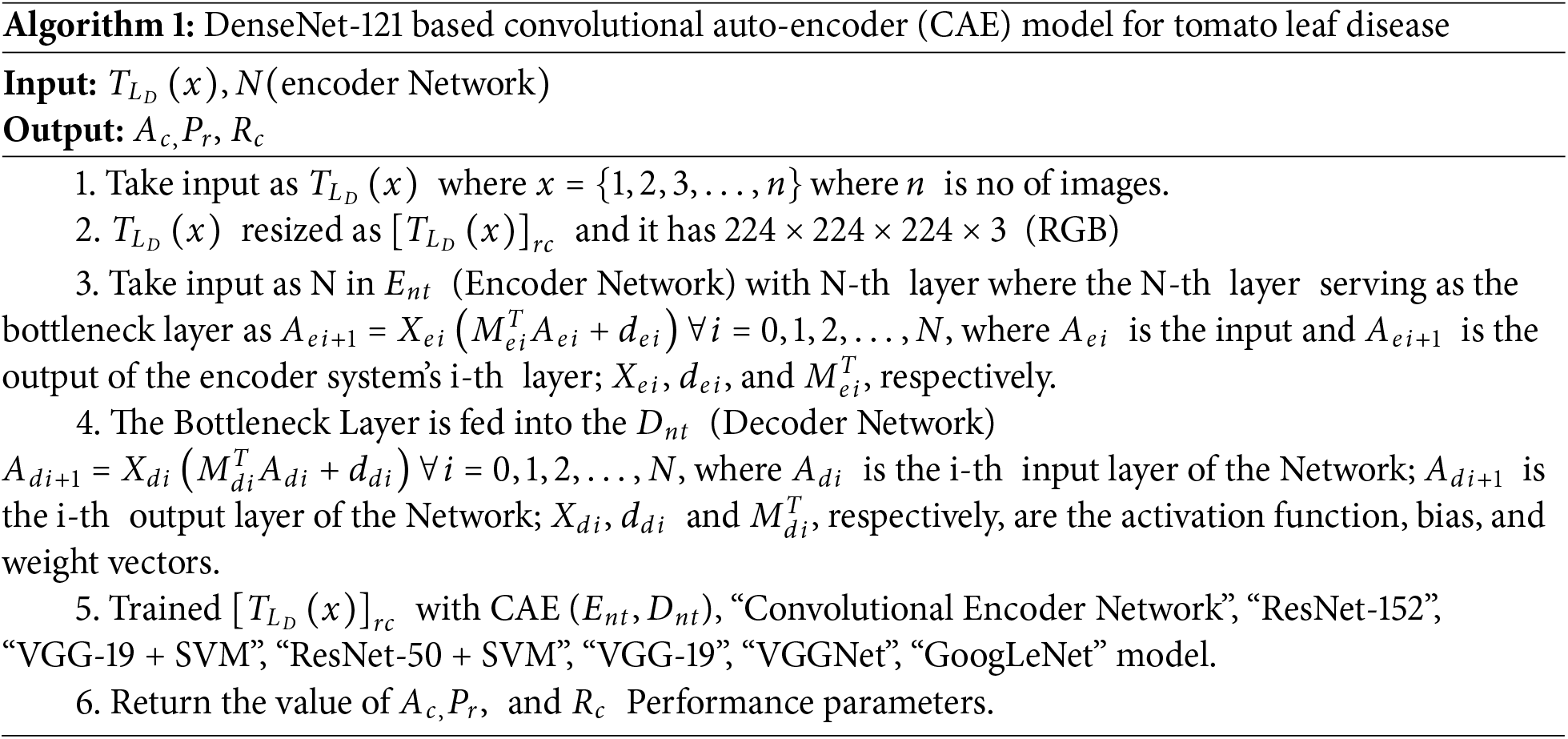

This study develops a novel hybrid system for crop disease identification. To the best of our knowledge, no existing research has proposed a hybrid model combining DenseNet121 and CAE for automated crop disease detection. The proposed architecture integrates two deep learning approaches: a Convolutional Auto-Encoder (CAE) and the DenseNet121 model. In the first stage, the CAE network processes input leaf images to achieve dimensionality reduction while preserving their principal components. The CAE is optimized by minimizing reconstruction loss during this compression process. Subsequently, the compressed feature representations generated by the CAE encoder are fed into a CNN-based classifier (DenseNet121) for final disease classification between healthy and infected leaves. The hybrid system’s architecture comprises two key components: (1) the CAE-based dimensionality reduction module, and (2) the DenseNet121 classification module. Relevant abbreviations used in the system implementation are listed in Table 3 and referenced in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1 has demonstrated the H-DCAE (Hybrid DenseNet-121 Convolutional Auto Encoder).

Take input as

4.1 Experimental Configuration

The hybrid model that was proposed was implemented in the experiments conducted for this research utilizing Google Colab for Python. To generate the model training and model testing data sets, the train test separation function of the Python sklearn API was utilized. The Keras API is used to build and train the prototype. Adam optimizer was utilized for the training of the CAE network using batches of 32 and 100 epochs. The “Adam” optimizer and “Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE)” loss with batch sizes of 32 and 100 epochs were used to train the suggested hybrid model [30]. Specifically, layers 1 through 8 imported from the CAE network should not be retrained. The trainable flag of such layers was changed to False amidst the training phase of the suggested hybrid approach. Early halting has been employed with a patience value equal to 5 to prevent model overfitting.

This study examines the suggested hybrid model’s efficiency using five evaluation criteria. The following metrics are employed in the analysis: “specificity”, “accuracy”, “precision”, “recall”, and “F1-score” [19]. “False Positives (

Eq. (5) states that “precision” is defined as the ratio of the expected true constructive rate to the sum as established by the given picture dataset. Eq. (6) illustrates that “recall value” or “sensitivity” is a positive value that is computed to the expected value of a particular class [31].

The F1-Score, or average of precision and recall, in Eq. (7) represents the result of determining the efficacy of diseased areas in the dataset. Accuracy is one of the parameters used to evaluate the classification model. It can be thought of as a measure of the neural network’s conversion into positive detection; its calculation is shown in Eq. (8).

By utilizing a model, specificity determines the genuine negative values. Eq. (9) is typically used in this paradigm to represent negative values.

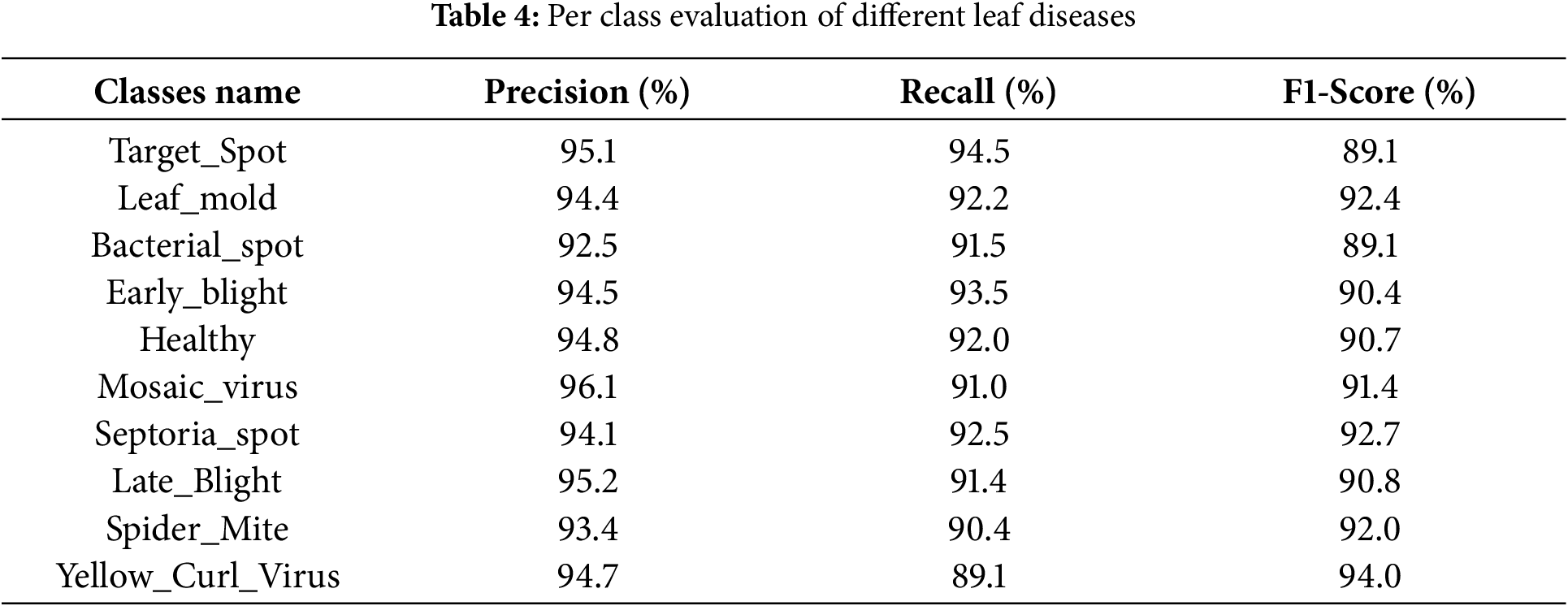

This study conducts a comparative analysis between state-of-the-art CNN architectures documented in recent literature and the DenseNet121 deep learning structure for classifying tomato leaf diseases. The computational efficiency was evaluated by deriving the time per epoch through the ratio of total epochs to complete training duration. Experimental results from our investigation demonstrate that the CAE network’s performance was evaluated using NRMSE (Normalized Root Mean Square Error) loss metrics, computed on authentic tomato leaf images. Comprehensive performance evaluations of the proposed model are presented in Table 4.

The bacterial spot is identified with a precision of 92.5%. In contrast to these, the yellow_curl_virus is identified with a recall of only 89.1% with an F1-score of 94.0%. The proposed hybrid strategy has a testing loss of 0.05 a training loss of 0.02 and a testing accuracy of 97.38%, and a training accuracy of 98.35%.

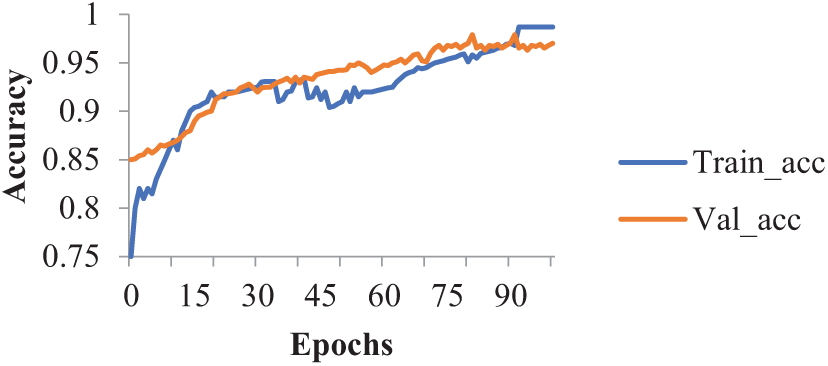

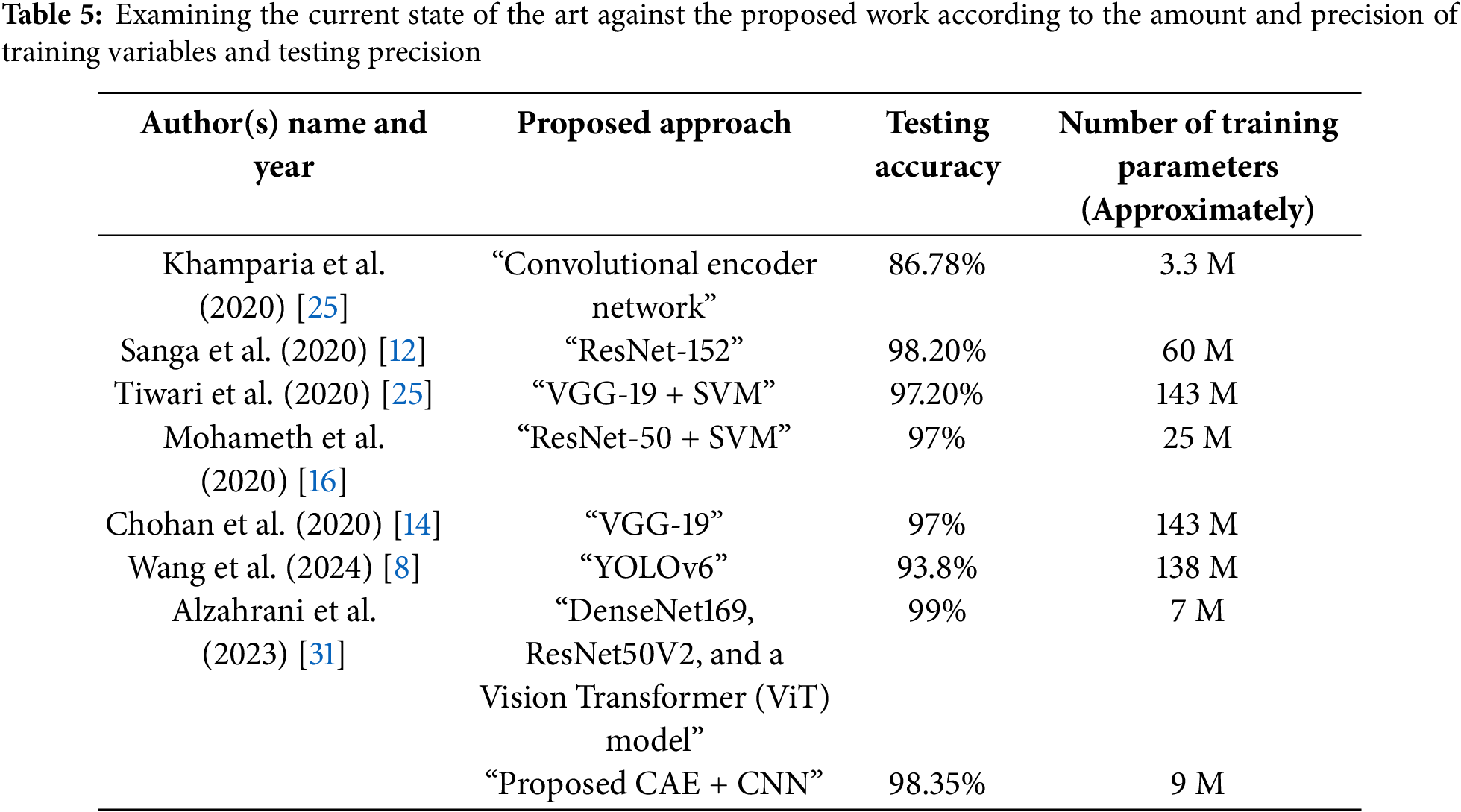

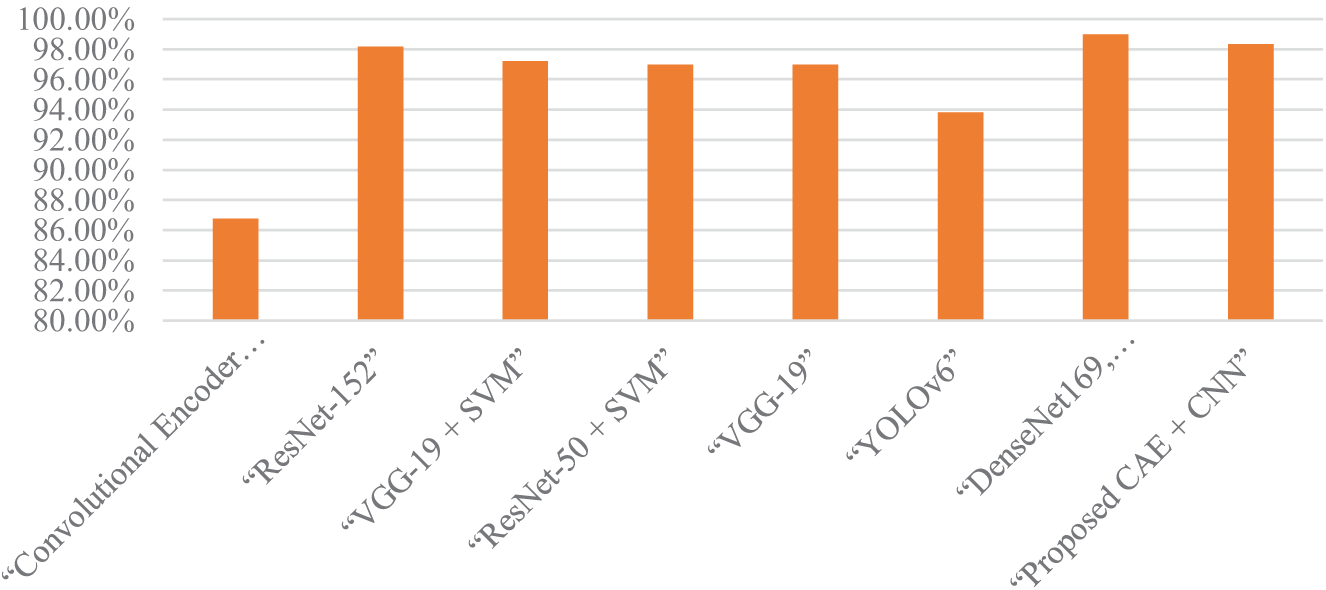

Fig. 5 shows how training and testing accuracy as well as loss as they relate to epochs have changed over time. For the suggested model, precision, recall, and F1-measure have also been calculated. The precision of the suggested hybrid model is 96.0%. Its F1 measure is 96.36%, and its Recall is 95.72%. Table 5 compares the proposed work with the many research projects published in the literature. For the suggested model, recall, precision, and F1-measure were calculated too. The precision of the suggested hybrid model is 98.0%. Its F1 measure is 98.36%, and its Recall is 98.72%. Table 5 shows that the suggested hybrid approach had 97.38% testing accuracy, which is higher in comparison to the research work accuracy by different authors. The proposed hybrid model achieved a training accuracy of 98.35% with a corresponding training loss of 0.02. On the validation dataset, the model attained an accuracy of 97.38% and a validation loss of 0.05. These metrics indicate that the model performs well on training and unseen data, demonstrating its effectiveness in accurately detecting and classifying plant diseases. The proposed model’s testing accuracy is marginally lower than that of the research works by having testing accuracy scores of 99.2%, 99.3%, and 99.5%, respectively. However, in comparison to the number of training variables in the cutting-edge systems addressed as a result, the projected hybrid approach needs relatively little time for both training and prediction. There are two key use cases for the suggested model. First, systems with minimal processing capacity can be utilized for automated illness diagnosis in plants with shorter training and estimation time. Following this, the suggested approach can be learned and applied to mobile devices. Instead of uploading plant leaf photos to the cloud or server, using a DL prototype in smartphone applications minimizes latency and gives farmers access to private data.

Figure 5: Accuracy graph of proposed hybrid model

The suggested hybrid approach attained a precision of 98.0%. It has a 98.72% Recall and an F1 rate of 98.36%.

The testing accurateness of the projected hybrid prototype was 97.38%, according to Table 3, which is higher as compared to the testing accuracy of research works by Kamparia et al. (2020), Tiwari et al. (2020), Chohan et al. (2020), and Mohamed et al. (2020), which were each 86.78 percent, 97.8 percent, and 98 percent, respectively shown in Fig. 6. Variations in precision and recall across several disease classifications indicate that the model misclassified diseases in its predictions. The model’s high precision of 96.1% for Mosaic Virus, for example, indicates a low false positive rate, whereas Yellow Curl Virus’s recall of 89.1% indicates a larger false negative rate for this class. These differences show where the model may improve in terms of lowering misclassification rates for some diseases while also highlighting its strengths in accurately detecting others.

Figure 6: Model comparison graph

Early detection of diseases in tomato plant leaves remains a challenging task due to the complex nature of pathological patterns. Although various deep learning and machine learning approaches have been developed for automated plant disease detection, most existing methods either achieve limited classification accuracy or require excessive computational resources. This study presents a novel hybrid architecture that combines convolutional neural networks (CNN) with convolutional autoencoder (CAE) for automated tomato leaf disease identification. The proposed approach first generates compact latent representations of leaf images through CAE-based dimensionality reduction, then performs classification using these compressed features via CNN. Compared to state-of-the-art models, this dual-stage framework significantly reduces feature dimensions and consequently decreases the number of required training parameters while maintaining high diagnostic accuracy. Experimental results demonstrate the model’s effectiveness with 98.35% classification accuracy. The reduced parameter count leads to substantially shorter training times for disease detection algorithms and enables faster diagnosis when deploying the trained model, making this solution particularly suitable for practical agricultural applications where both accuracy and efficiency are crucial.

Acknowledgement: Authors were supported by UKRI EPSRC Grant-funded Doctoral Training Centre at Swansea University, through PhD project RS718 on Explainable AI. Authors also have been supported by UKRI EPSRC: The Security, Privacy, Identity, and Trust Engagement Network Plus (phase 2). The authors acknowledge the above financial support.

Funding Statement: The authors have been funded by UKRI EPSRC Grant EP/W020408/1 Project SPRITE+ 2: The Security, Privacy, Identity, and Trust Engagement Network plus (phase 2) for this study. The authors also have been funded by PhD project RS718 on Explainable AI through the UKRI EPSRC Grant-funded Doctoral Training Centre at Swansea University.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Tajinder Kumar and Purushottam Sharma; methodology, Xiaochun Cheng; software, Sachin Lalar; validation, Xiaochun Cheng, Purushottam Sharma and Sarbjit Kaur; formal analysis, Sarbjit Kaur; investigation, Tajinder Kumar and Purushottam Sharma; resources, Xiaochun Cheng; data curation, Purushottam Sharma; writing—original draft preparation, Sarbjit Kaur and Ankita Chhikara; writing—review and editing, Ankita Chhikara and Purushottam Sharma; visualization, Vikram Verma; supervision, Vikram Verma; project administration, Purushottam Sharma; funding acquisition, Xiaochun Cheng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Trivedi NK, Gautam V, Anand A, Aljahdali HM, Villar SG, Anand D, et al. Early detection and classification of tomato leaf disease using high-performance deep neural network. Sensors. 2021;21(23):7987. doi:10.3390/s21237987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Kaur P, Harnal S, Gautam V, Singh MP, Singh SP. A novel transfer deep learning method for detection and classification of plant leaf disease. J Am Intell Humaniz Comput. 2023;14(9):12407–24. doi:10.1007/s12652-022-04331-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rumpf T, Mahlein AK, Steiner U, Oerke EC, Dehne HW, Plümer L. Early detection and classification of plant diseases with support vector machines based on hyperspectral reflectance. Comput Electron Agric. 2010;74(1):91–9. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2010.06.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Al Hiary H, Bani Ahmad S, Reyalat M, Braik M, ALRahamneh Z. Fast and accurate detection and classification of plant diseases. Int J Comput Appl. 2011;17(1):31–8. doi:10.5120/2183-2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Revathi P, Hemalatha M. Identification of cotton diseases based on cross information Gain_Deep forward neural network classifier with PSO feature selection. Int J Eng Technol. 2014;5(6):4637–42. [Google Scholar]

6. LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521(7553):436–44. doi:10.1038/nature14539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Haykin S. Neural networks: a comprehensive foundation. 2nd ed. Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

8. Wang Y, Zhang P, Tian S. Tomato leaf disease detection based on attention mechanism and multi-scale feature fusion. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1382802. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1382802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Kaur P, Mishra AM, Goyal N, Gupta SK, Shankar A, Viriyasitavat W. A novel hybrid CNN methodology for automated leaf disease detection and classification. Expert Syst. 2024;41(7):e13543. doi:10.1111/exsy.13543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kukreja V, Dhiman P. A deep neural network based disease detection scheme for citrus fruits. In: 2020 International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC); 2020 Sep 10–12; Trichy, India. p. 97–101. doi:10.1109/icosec49089.2020.9215359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Nandhini S, Ashokkumar K. An automatic plant leaf disease identification using DenseNet-121 architecture with a mutation-based henry gas solubility optimization algorithm. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(7):5513–34. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06714-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sanga SL, Machuve D, Jomanga K. Mobile-based deep learning models for banana disease detection. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2020;10(3):5674–7. doi:10.48084/etasr.3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chohan M, Khan A, Chohan R, Katpar SH, Mahar MS. Plant disease detection using deep learning. Int J Recent Technol Eng. 2020;9(1):909–14. doi:10.35940/ijrte.a2139.059120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2015. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mohameth F, Chen B, Sada KA. Plant disease detection with deep learning and feature extraction using plant village. J Comput Commun. 2020;8(6):10–22. doi:10.4236/jcc.2020.86002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gupta S, Dwivedi A, Sharma P. Plant leaf disease detection using a hybrid model. Lect Notes Electr Eng. 2025;1278:139–54. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-8193-5_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mkonyi L, Rubanga D, Richard M, Zekeya N, Sawahiko S, Maiseli B, et al. Early identification of Tuta absoluta in tomato plants using deep learning. Sci Afr. 2020;10:e00590. doi:10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Khan S, Narvekar M. Novel fusion of color balancing and superpixel based approach for detection of tomato plant diseases in natural complex environment. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(6):3506–16. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Vallabhajosyula S, Sistla V, Kolli VKK. A novel hierarchical framework for plant leaf disease detection using residual vision transformer. Heliyon. 2024;10(9):e29912. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Dhiman P, Kukreja V, Manoharan P, Kaur A, Kamruzzaman MM, Ben Dhaou I, et al. A novel deep learning model for detection of severity level of the disease in Citrus fruits. Electronics. 2022;11(3):495. doi:10.3390/electronics11030495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Catal Reis H, Turk V. Potato leaf disease detection with a novel deep learning model based on depthwise separable convolution and transformer networks. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133:108307. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lv M, Su WH. YOLOV5-CBAM-C3TR: an optimized model based on transformer module and attention mechanism for apple leaf disease detection. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1323301. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1323301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhou Z, Zang Y, Li Y, Zhang Y, Wang P, Luo X. Rice plant-hopper infestation detection and classification algorithms based on fractal dimension values and fuzzy C-means. Math Comput Model. 2013;58(3–4):701–9. doi:10.1016/j.mcm.2011.10.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Khamparia A, Saini G, Gupta D, Khanna A, Tiwari S, de Albuquerque VHC. Seasonal crops disease prediction and classification using deep convolutional encoder network. Circ Syst Signal Process. 2020;39(2):818–36. doi:10.1007/s00034-019-01041-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pardede HF, Suryawati E, Sustika R, Zilvan V. Unsupervised convolutional autoencoder-based feature learning for automatic detection of plant diseases. In: 2018 International Conference on Computer, Control, Informatics and its Applications (IC3INA); 2018 Nov 1–2; Tangerang, Indonesia. p. 158–62. doi:10.1109/IC3INA.2018.8629518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hughes DP, Salathe M. An open access repository of images on plant health to enable the development of mobile disease diagnostics. arXiv:1511.08060. 2015. [Google Scholar]

28. Weiss K, Khoshgoftaar TM, Wang D. A survey of transfer learning. J Big Data. 2016;3(1):9. doi:10.1186/s40537-016-0043-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bisong E. Autoencoders. In: Building machine learning and deep learning models on google cloud platform: a comprehensive guide for beginners. Berkeley, CA, USA: Apress; 2019. p. 475–82. doi:10.1007/978-1-4842-4470-8_37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kingma D, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In: International Conference on Learning Representations; 2014 Apr 14–16; Banff, AB, Canada. p. 1–15. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Alzahrani MS, Alsaade FW. Transform and deep learning algorithms for the early detection and recognition of tomato leaf disease. Agronomy. 2023;13(5):1184. doi:10.3390/agronomy13051184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools