Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Dynamic Route Optimization for Multi-Vehicle Systems with Diverse Needs in Road Networks Based on Preference Games

1 School of Transportation Science and Engineering, Beihang University, Beijing, 100191, China

2 School of Electrical and Control Engineering, North China University of Technology, Beijing, 100144, China

3 Hangzhou Innovation Institute, Beihang University, Hangzhou, 310023, China

4 The State Key Lab of Intelligent Transportation System, Beijing, 100191, China

* Corresponding Author: Yilong Ren. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4167-4192. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.062503

Received 19 December 2024; Accepted 06 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

The real-time path optimization for heterogeneous vehicle fleets in large-scale road networks presents significant challenges due to conflicting traffic demands and imbalanced resource allocation. While existing vehicle-to-infrastructure coordination frameworks partially address congestion mitigation, they often neglect priority-aware optimization and exhibit algorithmic bias toward dominant vehicle classes—critical limitations in mixed-priority scenarios involving emergency vehicles. To bridge this gap, this study proposes a preference game-theoretic coordination framework with adaptive strategy transfer protocol, explicitly balancing system-wide efficiency (measured by network throughput) with priority vehicle rights protection (quantified via time-sensitive utility functions). The approach innovatively combines (1) a multi-vehicle dynamic routing model with quantifiable preference weights, and (2) a distributed Nash equilibrium solver updated using replicator sub-dynamic models. The framework was evaluated on an urban road network containing 25 intersections with mixed priority ratios (10%–30% of vehicles with priority access demand), and the framework showed consistent benefits on four benchmarks (Social routing algorithm, Shortest path algorithm, The comprehensive path optimisation model, The emergency vehicle timing collaborative evolution path optimization method) showed consistent benefits. Results show that across different traffic demand configurations, the proposed method reduces the average vehicle traveling time by at least 365 s, increases the road network throughput by 48.61%, and effectively balances the road loads. This approach successfully meets the diverse traffic demands of various vehicle types while optimizing road resource allocations. The proposed coordination paradigm advances theoretical foundations for fairness-aware traffic optimization while offering implementable strategies for next-generation cooperative vehicle-road systems, particularly in smart city deployments requiring mixed-priority mobility guarantees.Keywords

With the rising number of vehicles on the road networks, traffic congestion has become more frequent. Expanding roads and imposing vehicle restrictions are ineffective solutions to this issue [1,2]. In a vehicle-road collaborative environment, vehicle-road communication technology enables the real-time exchange of traffic status information between vehicles and the road infrastructure [3,4]. Consequently, transportation systems display key characteristics such as interconnectivity, personalization, and adaptability. These features not only enhance the intelligence of road traffic control but also significantly increase the complexity of traffic management challenges [5].

Intelligent collaborative decision-making technology for vehicle groups, which considers varying traffic needs, is seen as an effective solution for alleviating congestion and optimizing traffic. This is achieved through the transmission, fusion, and interaction of traffic information across both time and space [6–8]. Through dynamic vehicle route planning at the micro level, traffic performance at the macro level can be enhanced, addressing the needs of various vehicles and optimizing the use of road network resources [9–12].

Most existing studies on vehicle routing planning are static and can be classified into two categories: routing planning and centralized multi-vehicle routing planning [13–15]. Single-vehicle route selection planning identifies the most efficient path by analyzing the current road conditions and predicting future road states. Rosita et al. applied the Dijkstra algorithm with multi-criteria decision-making to optimize route assignment for individual vehicles [16]. Wang et al. introduced a comprehensive path optimization model that incorporates Kalman-filtered short-term predictions and an enhanced bootstrap-based Dijkstra algorithm to determine the optimal vehicle routes [17]. Chauhan et al. developed a path discovery model combining the Bellman-Ford algorithm with a Topology-Preserving Feature Network (TPFN), leveraging a deep Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) classifier and Bellman-Ford pattern search optimization to compute the nearest optimal route for a single-vehicle [18]. While these methods offer the benefits of clarity and simplicity, they also have notable limitations. Besides involving complex computations and being prone to local optima, single-vehicle optimization methods overlook vehicle interaction. As a result, multiple vehicles may be directed onto the same route, and the planned paths may fail to adapt to emergencies or prioritize certain vehicles. Consequently, actual travel results often deviate from expectations, limiting their effectiveness in alleviating traffic congestion. Centralized multi-vehicle route selection planning reformulates the problem as a maximum-minimum optimization task, aiming to determine the globally optimal set of recommended routes for multi-vehicles [19,20]. Ebrahimi et al. introduced the Best Neighborhood Algorithm for Routing Traffic (BNART), a heuristic approach designed for centralized route guidance of autonomous vehicles [21]. Multi-vehicle centralized route planning methods can achieve a global benefit, but this often comes at the expense of some vehicles. Being static, these methods are ill-equipped to handle emergencies and may even lead to traffic congestion drifts. In contrast to static vehicle routing planning, vehicles in large-scale road networks with multiple intersections must navigate through diverse regions and interact with multiple vehicles and edge devices [22]. Therefore, there is a coupling between the trajectories of the same vehicle across different regions, as well as between the trajectories of different vehicles within the same region. Furthermore, the urgency for different vehicles to pass through certain areas varies significantly, posing a considerable challenge in solving the collaborative decision-making problem for vehicle path selection in road network scenarios. Conventional static vehicle path planning methods are no longer suitable for future cooperative vehicle path scenarios. Several researchers have conducted preliminary studies on the collaborative decision-making problem for multi-vehicle dynamic route selection in large-scale scenarios [23–25]. One approach integrates heuristic algorithms with conventional path optimization techniques. Jiang et al. combined ant colony and particle swarm algorithms with the A∗ method to develop an intelligent optimization algorithm featuring adaptive ant colony and particle swarm optimization. By employing different search strategies at various stages of the algorithm, they dynamically adjusted the vehicle routes [26]. Typaldos et al. developed a method for determining the quickest route using the A∗ algorithm [27]. While the single-vehicle dynamic path optimization method addresses the limitations of static path planning and enhances both performance and responsiveness, its reliance on individual decision-making prevents effective coordination of overall road network demands, making it challenging to prioritize the needs of high-priority vehicles. Another common approach is the decentralization strategy, where the large road network is segmented into smaller areas, with vehicles coordinating and performing path selection planning within their respective zones. Lu et al. designed a two-layer traffic coordination control system, where the claims of multiple vehicles were sent to the intersection’s edge for game control [28]. Similarly, Batista et al. created a path selection model and developed an optimization algorithm by dividing the traffic into sub-areas and limiting the search range [29]. Due to the independence of vehicle trajectories across different zones, the decentralized strategy fails to fully harness the benefits of vehicle group collaborative decision-making for optimal route selection, thereby increasing the uncertainty in traffic control performance. Current methods struggle to dynamically and effectively address the varying individual traffic needs and the overall traffic system control performance. Consequently, there is an urgent need for a new vehicle group collaborative route selection algorithm to effectively balance individual needs with the coordination performance of the road network. To address this, this study presents a collaborative routing algorithm for multiple vehicles at single intersections, grounded in preference games (ACRABPG). A collaborative decision-making model was developed for vehicles with varying traffic demands, based on micro-intersections, to address the challenge of multi-vehicle route selection in a large-scale transportation network. A comparative analysis was conducted with two alternative algorithms to assess the effect of changing the relative frequency of vehicles with different traffic demand profiles on the mean travel duration of automobiles. A comparative analysis was performed on the traffic control performance of the collaborative decision-making models for vehicles with varying traffic demands across different traffic scenarios.

This study is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the problem description, while Section 3 covers the development of a multi-vehicle dynamic route selection model based on game theory. Section 4 discusses the application of the multi-vehicle collaborative route selection algorithm in road networks using game theory principles. Section 5 presents a simulation analysis, and Section 6 summarizes the limitations of this study.

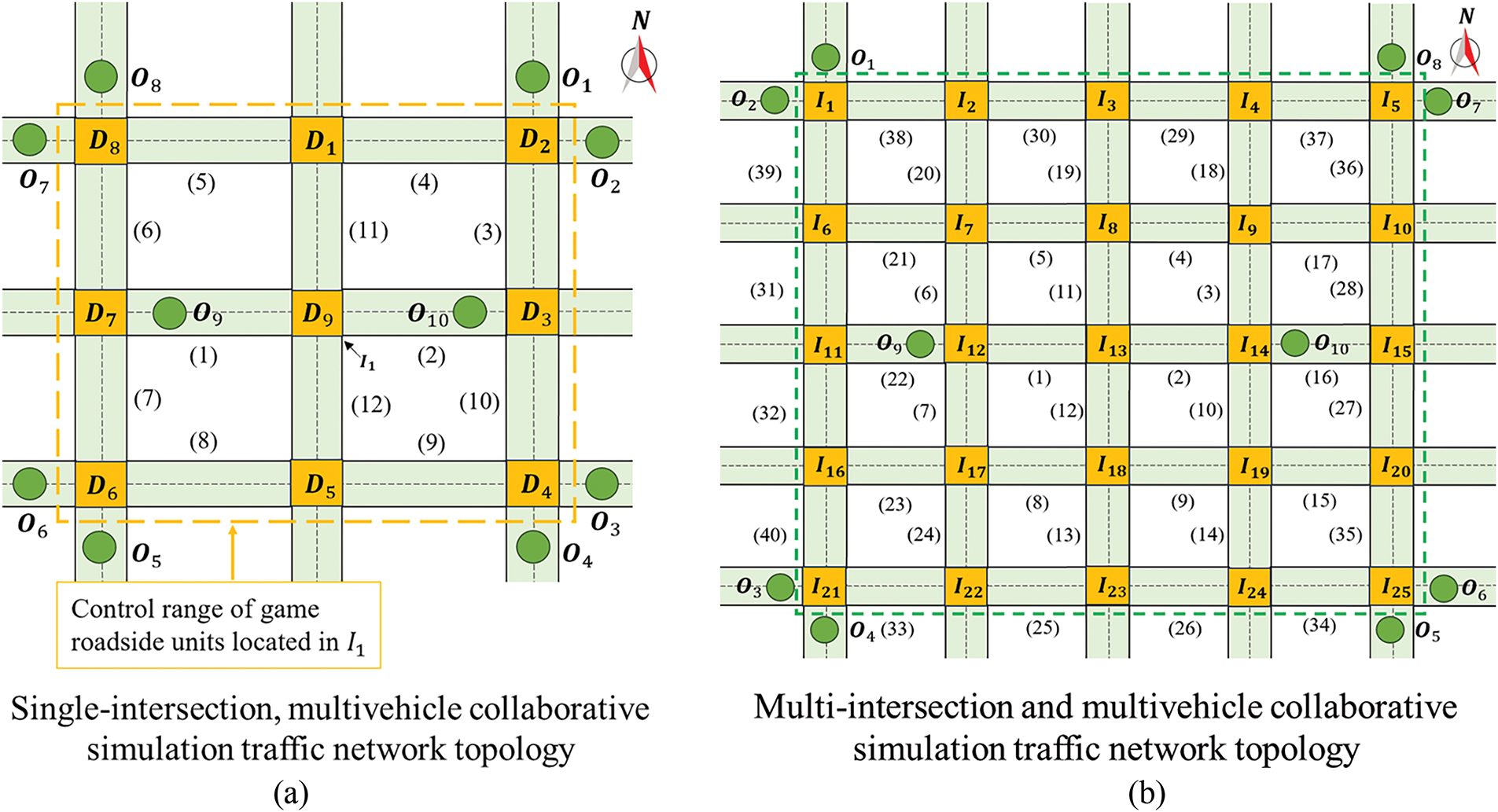

Fig. 1 illustrates the scenario of vehicle group collaborative route selection decision-making in the vehicle-road collaborative environment examined in this study. The blue area represents the intersection conflict zone, where vehicles make specific path choices. The vehicles are categorized into two types: ordinary traffic demand vehicles, denoted as Cargeneral, do not have high traffic urgency, while priority vehicles, denoted as Carspecial, have urgent traffic demands. Carspecial prefers smooth road sections. The identification process for Carspecial involves two steps: vehicle initiation and confirmation by the roadside unit. In the vehicle-road collaborative environment, roadside units are classified into two types. The first type, known as the conventional roadside unit, includes an information collection module and a data distribution module, facilitating direct communication with vehicles and other roadside infrastructure. The second type, known as the game roadside unit, is positioned at intersections and comprises an information collection module, a game computation module, and a data distribution module. Its primary function is to optimize vehicle route planning within its designated control area. The game roadside unit operates within a defined control area. As shown in Fig. 1, the game roadside unit at intersection I1 manages a control area encompassing 9 intersections and 12 directed roads, delineated by the green dashed box. For clarity, this study is based on three key assumptions regarding the research scenario: In the road network setting, all vehicles are considered connected. In other words, vehicles are equipped with communication capabilities for vehicle-to-road interactions. This study assumes an ideal vehicle-to-road communication environment, disregarding factors such as delay and packet loss. In addition, vehicle lane-changing behavior on road segments was not considered.

Figure 1: Typical large-scale road network scenario

The objective of collaborative vehicle routing decision-making in large-scale road network scenarios is to use the vehicle-road collaboration platform to generate optimal routes based on real-time traffic conditions. This approach balances road network usage while accommodating the diverse requirements of individual vehicles. This study defines a relatively balanced road network from the vehicle’s perspective, assessing whether similar vehicles opt for a particular road despite the availability of potentially better alternatives. This metric is used to determine whether a road is experiencing excessive usage. The definition of a road being idle is determined by whether similar vehicles opt for alternative routes and whether selecting this road results in increased revenue. To accomplish the objectives of this research, the following two key scientific challenges must be addressed:

Problem 1: The collaboration of multiple vehicles at a single intersection is fundamentally a game-theoretic process, where the Nash equilibrium of the vehicles’ interest determines the optimal collaborative road choice for the groups of vehicles passing through the intersection. A Nash equilibrium is a game scenario in which each participant selects their optimal strategy independently of others’ choices, leading to a stable outcome for the entire game. At a single intersection, vehicles display varying levels of traffic urgency, and the number of vehicles can fluctuate. Consequently, identifying the right game model and selecting an algorithm to achieve equilibrium are key challenges. These factors add to the difficulty of achieving a Nash equilibrium in the multi-vehicle cooperative path selection problem at a single intersection.

Problem 2: A large-scale road network consists of numerous junctions and route segments, where overlapping control areas and restricted cognitive ranges between intersections pose a challenge. Furthermore, when developing a game model at a single intersection to assess the benefits of each strategy, the current road conditions were used to estimate the time required to reach the temporary terminus. However, when a vehicle arrives at the next game intersection, the actual road condition may differ to varying extents from the previously predicted state. The traffic conditions on unconnected roads may have changed significantly, potentially causing vehicles to receive conflicting routing outcomes at both the next and previous intersections. The routing recommendation provided to the vehicle at the yellow intersection I5 in Fig. 2 may differ from the recommendation given when driving to the green intersection I8. Consequently, coordinating vehicle routing decisions across multiple intersections within a road network to achieve traffic balance and maintain the continuity of traffic flow presents a significant challenge.

Figure 2: Large-scale road network

3 Construction of a Multi-Vehicle Dynamic Route Selection Model Based on Game Theory

3.1 Multi-Vehicle Collaborative Model at a Single Intersection

To address the challenges of model determination and Nash equilibrium solutions in multi-vehicle collaborative road selection at a single intersection, this study introduces a collaborative modeling approach. The proposed model facilitates a road selection game among vehicles with diverse requirements, ensuring efficient traffic management and optimal road resource allocation in single-intersection scenarios.

The scenario shown in Fig. 2 was selected, and the road model was represented using a directed weighted graph

The road model was developed based on the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) formula [30]. It represents a high-level, macroscopic road model. By evaluating the maximum load capacity of the road, the highest permissible driving speed, and the current quantity of vehicles on the road, the determination of the time required for vehicles to traverse a specific road section becomes possible. The BPR formula is expressed as follows:

In this context, t denotes the duration required for a vehicle to traverse the road section, while tfree represents the time needed for vehicles to navigate the section at their maximum speed, assuming unobstructed road conditions. Cap represents the maximum vehicular capacity of the road section, and n denotes the current number of vehicles present.

Given the large number of vehicles involved in road selection planning at intersections and their varying urgency levels, priority is assigned to vehicles with higher urgency. Consequently, vehicles with lower urgency must yield and take less congested road sections. However, it is equally important to consider the overall traffic efficiency of the vehicles. Therefore, a population game model incorporating altruistic preferences is established, with the game process defined as

Each group of vehicles is defined as a “population”

For a “population”

To achieve this objective, this study evaluates the benefits of each strategy based on the time required for a vehicle to reach its temporary endpoint. It aims to enhance the revenue of priority vehicles,

The delay

here,

The objective of this study is to identify a community state

3.2 Collaborative Model between Multiple Intersections

When a vehicle leaves the game intersection following a recommended strategy, the recommendation results at the next game intersection may differ due to changes in the road network status. This study introduces a multi-vehicle collaborative model that integrates the recommended routing outcomes across multiple intersections, developing a routing game for vehicles with varying demands in multi-intersection scenarios. This approach ensures seamless traffic scheduling and optimal road resource allocation.

Given the large number of vehicles participating in road selection planning at multiple intersections and the different attributes of different vehicles, some vehicles have urgent traffic needs. Some vehicles follow the strategy recommended by the previous game intersection and prefer to ensure the continuity of traffic scheduling when reaching that intersection. Some are vehicles that have just entered the intersection of the game; some are vehicles that have completed the previous intersection recommendation strategy. Therefore, it is still necessary to classify these vehicles into three categories. One consists of priority vehicles

To address the needs of

The vehicles participating in the game are grouped according to their starting point and temporary endpoint near the intersection of the game. Vehicles within the same group have the same temporary endpoint and are currently driving on the same road segment. To make the description more concise, this article refers to the current section of a vehicle as the initial point of the vehicle. In this way, the population in the model, which is the number of vehicle groups, is equal to the product of the number of temporary endpoints and the number of initial points.

For a “population”

This article evaluates the benefits of each strategy based on the time required for the vehicle to reach the temporary endpoint. We use

The delay

here,

As the primary aim of this article is to identify a community state

4 Implementation of the Multi-Vehicle Collaborative Route Selection Algorithm in Road Networks Based on Game Theory

4.1 Single-Intersection, Multi-Vehicle Collaborative Road Selection Algorithm

The population game model is transformed into a replicator subdynamic model to determine the Nash equilibrium. During initialization, the control range and the temporary endpoint position of each game roadside unit are established. Vehicles assign driving routes based on each strategy, selecting roads at game intersections according to the strategic direction. In non-intersection segments, vehicles continue along the optimal route in terms of the physical distance to the temporary endpoint. When multiple shortest paths with equal physical distances exist, the selection is made proportionally. The strategic benefits are then computed, and the average sum of the benefits is determined for these road segments.

During vehicle operation, the assisted driving system registers an agent for each vehicle on the conventional roadside unit. This unit categorizes vehicles as

The fourth-order Runge–Kutta solution method is described as follows. For ordinary differential equations, the expression is given as follows:

Given the initial state

Through multiple iterations, the game converges dynamically to a stable point, representing the Nash equilibrium state for all vehicle agents on the current roadside unit. Subsequently, the game is played with roadside units, and the number of vehicles traveling in each direction is calculated for each agent group based on the Nash equilibrium state. For each group and travel direction, a corresponding number of vehicle agents is evenly selected according to their expected arrival time at the intersection, and their travel direction is determined. Upon receiving the recommended routing scheme, each agent communicates directly with the corresponding vehicle through the game’s roadside unit, relaying the routing scheme to the vehicle’s assisted driving system. The driver then follows the vehicle’s system guidance to implement the travel route. A vehicle agent that completes the game is removed from the game by the roadside unit. Vehicles that have passed through the intersection register their agents with the game’s roadside unit at the next intersection, obtaining new routes through another iteration of the game. Fig. 3 shows the primary process of the multi-vehicle cooperative route algorithm conducted on a single-game roadside unit. The corresponding algorithm is Algorithm 1.

Figure 3: Flowchart of the single intersection, multi-vehicle collaborative road selection algorithm

4.2 Multi-Vehicle Collaborative Route Selection Algorithm in a Road Network

Similar to the multi-vehicle collaborative road selection at a single intersection, the multi-vehicle collaborative road selection algorithm in the road network also converts the population game model into a replicator subdynamic model to compute the Nash equilibrium. The control range and temporary endpoint position for each game roadside unit are established at the start. For each strategy, the appropriate driving route is assigned, with the road selected based on the strategy’s direction at the game intersection. The vehicles then continue to the temporary endpoint in the non-intersection section, following the route that minimizes the physical distance. When multiple shortest paths with equal physical distances exist, these paths are selected based on their proportional lengths. The strategic benefits are calculated, and the average total benefits for these road segments are determined.

Throughout the vehicle’s journey, the assisted driving system assigns an agent to the vehicle on the conventional roadside unit. The conventional roadside unit categorizes vehicles into

Figure 4: Flowchart of the single-intersection, multi-vehicle collaborative road selection algorithm

To validate the effectiveness of the optimization method proposed in this study, a simulation scenario, as shown in Fig. 5, was employed. The analysis focuses on various performance indicators, such as average travel time, road network throughput, road load balance, and other metrics, across different vehicle types and traffic demand conditions. The road model in the scenario shown in Fig. 5a comprises 9 intersections and 24 bidirectional roads, with 10 starting points and 9 temporary endpoints defined within the model. Vehicles enter the network from the starting points and exit at the endpoints. Upon entry, there is an 80% probability that vehicles will select intersections with a diagonal direction as their destination, while 10% are designated as

Figure 5: Two types of simulation scenarios

This study uses VISSIM 4.3 (PTVAG, 2008) for simulation, with the model implemented in Python 3.7.4. The experiments were conducted on a desktop computer featuring an Intel 3.6 GHz CPU and 16 GB of RAM. Each simulation run lasted for 1.5 h.

Several routing algorithms have been developed to address different aspects of vehicle navigation. The social routing algorithm [31] follows fair game principles but does not consider specific vehicle requirements. It uses social networks to group vehicles based on trajectory overlap, with all but the last vehicle in each group following historical routes. The last vehicle calculates the shortest path to its destination, considering the plans of the preceding vehicles. This algorithm clusters vehicles within a 30 s. The shortest path algorithm [32], a non-collaborative approach, directs each vehicle to follow the shortest physical route to its destination. The comprehensive path optimization model (CPOM) [17] incorporates Kalman filtering for short-term predictions and introduces a time dimension factor through a layered approach. It employs an enhanced Dijkstra algorithm for optimal route planning. The emergency vehicle timing collaborative evolution path optimization method (TCEPO) [33] introduces a second-level optimization objective, incorporating flexible time windows for intersection safety evaluation in uncertain environments. TCEPO aims to optimize rescue path risk coefficients using an improved ripple expansion algorithm.

5.2 Simulation Results and Analysis

This study first examines the multi-vehicle collaborative routing problem under varying traffic demands at a single intersection. The road network throughput and average vehicle travel time are the primary performance metrics used to evaluate traffic efficiency. The network throughput is quantified by recording the number of vehicles that reached their endpoint during the simulation. Since travel times for vehicles still en route remained undetermined, the average travel time was calculated based only on completed trips. To compare the performance of the multi-vehicle collaborative routing algorithms under different traffic conditions at single intersections, an average vehicle inflow of 10 veh/min was set as the starting point. For the starting points

Figure 6: Road network throughput and average vehicle travel time under varying traffic flow conditions

The multi-vehicle collaborative optimization algorithm based on the preference game proposed in this study consistently achieves maximum or near-maximum throughput, regardless of traffic flow variations. Moreover, its effectiveness in improving the traffic throughput increases with higher traffic volumes. For example, when vehicle inflow at the starting points

Compared to the four existing methods, the algorithm proposed in this study achieves the shortest average travel time across various traffic flow densities. Under all four traffic conditions, the average travel time using the proposed method remains below 225 s. When the vehicle inflow at the starting points

Figure 7: Average travel time of vehicles in environments with varying proportions of priority vehicles

Fig. 7 demonstrates that regardless of variations in vehicle inflow rates and the proportion of priority vehicles among all simulated vehicles, the average travel time for priority vehicles remains significantly lower than that for ordinary vehicles, achieving a minimum time saving of 16 s. Notably, the travel time of ordinary vehicles is at most 8 s longer than the overall average. These results indicate that the proposed algorithm effectively balances individual requirements with road network coordination performance across environments with varying priority vehicle ratios. To further assess the algorithm’s efficacy in managing vehicle diversion, a statistical evaluation of traffic density was conducted within the control range of the game roadside unit. This evaluation took place every 15 min during each simulation process, under conditions where the average vehicle inflow rate at the starting points

Figure 8: Vehicle density distributions of various algorithms at different time intervals

As shown in Fig. 8a,b, a significant diversion effect is demonstrated by the proposed method. Although higher vehicle densities in both directions are exhibited by Roads 1 and 2 compared to other roads, the overall distribution of vehicles is relatively balanced. The timely diversion of vehicles to less congested roads ensures that most routes do not experience high vehicle density or slow traffic. In contrast, dynamic routing adjustments based on road conditions are lacking in the shortest path algorithms illustrated in Fig. 8e,f, leading to uneven traffic distribution. Saturation is reached by some roads while others remain underutilized. As the simulation progressed, traffic congestion worsened, with an increase in the number of congested road sections. Initially, higher traffic densities are only known on Road 1 (positive direction) and Road 2 (reverse direction), but by the 90-min mark, saturation is reached on 14 roads, including both directions of Roads 1 and 2. High traffic density and congestion on certain roads are also exhibited by the social routing selection algorithms shown in Fig. 8c,d in the latter stages of the simulation. The CPOM method, shown in Fig. 8g,h, is employed to divert vehicles to less congested road sections using the predicted data. However, due to its inability to effectively prioritize certain vehicles, a gradual increase in the traffic flow density was observed after 60 min. The TCEPO method, shown in Fig. 8i,j, places so much emphasis on the passage rights of priority vehicles that it significantly compromises the passage rights of ordinary vehicles. As the simulation time advances, congestion begins to build on all roads. This highlights that improving traffic efficiency becomes a significant challenge without effectively balancing the competing interests of multiple vehicles.

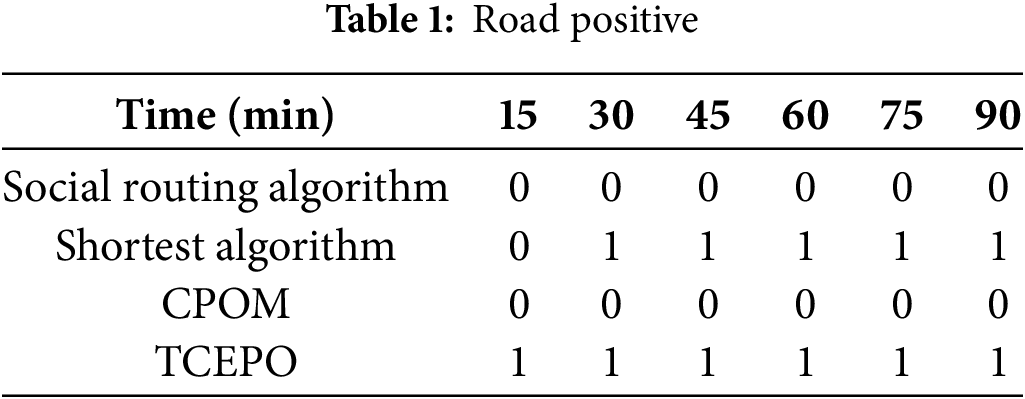

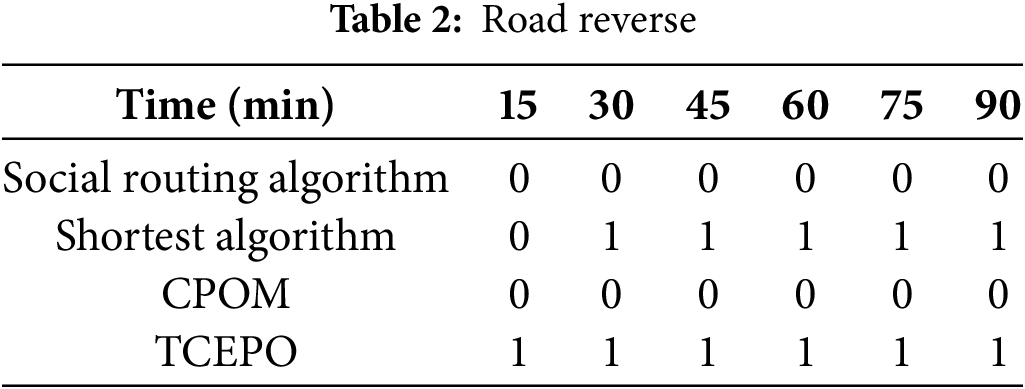

The proposed ACRABPG method and the four other methods underwent simultaneous significance testing using the Origin software. Because the data did not follow a normal distribution, non-parametric testing was used for the significance analysis. The null hypothesis stated that ACRABPG does not differ significantly from the other four methods, with the significance level set at 0.05. Tables 1 and 2 present the simulation results, where a value of 0 indicates no significant difference between the two methods and 1 denotes a significant difference.

The results in Tables 1 and 2 show that the proposed method in this study exhibits no significant difference from the social routing and CPOM methods in terms of skewness. However, its mean is notably smaller—approximately 2.7 and 2.4 times lower than those of the social routing and CPOM methods, respectively. After 15 min of simulation, a significant difference emerged between the proposed method and both the shortest path and TCEPO methods, indicating distinct data biases among these approaches. The effectiveness of the proposed method lies in its ability to redirect vehicles to uncongested road sections while maintaining traffic efficiency, thereby preventing partial road congestion and low traffic flow on certain roads. This capability highlights the progressive nature of the proposed method.

To evaluate the ACRABPG proposed in this study for the multi-vehicle collaborative routing problem with varying traffic demands in road network scenarios, this study focuses on two key indicators: road throughput and average vehicle travel time. These metrics are similar to those used in the single-intersection scenarios. The initial game vehicle composition included 30% directional vehicles and 10% priority vehicles. The inflow rate from the starting points

Figure 9: Road network throughput and average vehicle travel time under varying traffic flow conditions

Figure 10: Average travel times of vehicles in environments with varying proportions of priority vehicles

Fig. 9 shows that the ACRABPG method consistently achieves the highest road network throughput, regardless of the vehicle inflow rates. Its advantage becomes more pronounced as the vehicle inflow rate increases. For example, when the inflow rate at

Fig. 10 shows that regardless of variations in the vehicle inflow rate and the proportion of priority vehicles among all game vehicles, the average travel time for priority vehicles remains substantially lower than that of ordinary vehicles, with a minimum difference of 37 s. Meanwhile, the travel time for ordinary vehicles does not substantially exceed that of all game vehicles, with a maximum difference of only 19 s. This result indicates that the proposed algorithm effectively balances individual needs and road network coordination in scenarios with different priority vehicle ratios. To further evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in vehicle diversion, a simulation was conducted under the following conditions: an average vehicle inflow rate of 80 veh/min at the starting points

Figure 11: Vehicle density distributions of different algorithms at various time points

As shown in Fig. 11a,b, the proposed ACRABPG method effectively redirects vehicles to less congested roads, enabling them to exit the road network quickly. This approach prevents any road network from reaching saturation density, maintaining an average network traffic density of 34 vehicles, thereby demonstrating its strong traffic diversion capability. Fig. 11c,d shows that the social routing algorithm successfully distributes vehicles across less congested roads, promoting load balancing. However, after 60 min of simulation, it still results in high vehicle density and congestion on multiple roads, such as roads 17 to 20. Fig. 11e,f indicates that the shortest path algorithm, which prioritizes the shortest physical distance, leads to severe congestion on these routes while leaving alternative roads underutilized. For example, intersections 22 to 40 experience full congestion, whereas roads 3 to 14 accommodate fewer than 24 vehicles. As shown in Fig. 11g,h, the CPOM method effectively allocates vehicles to low-traffic road sections because of its predictive capability. Although it prevents road saturation, its limited prediction range hampers congestion reduction, resulting in an overall traffic density 1.6 times higher than that of ACRABPG. Finally, Fig. 11i,j demonstrates that the TCEPO method, which prioritizes certain vehicles, inevitably leads to congestion by compromising ordinary vehicles. This highlights the importance of balancing the needs of different participants to prevent worsening congestion.

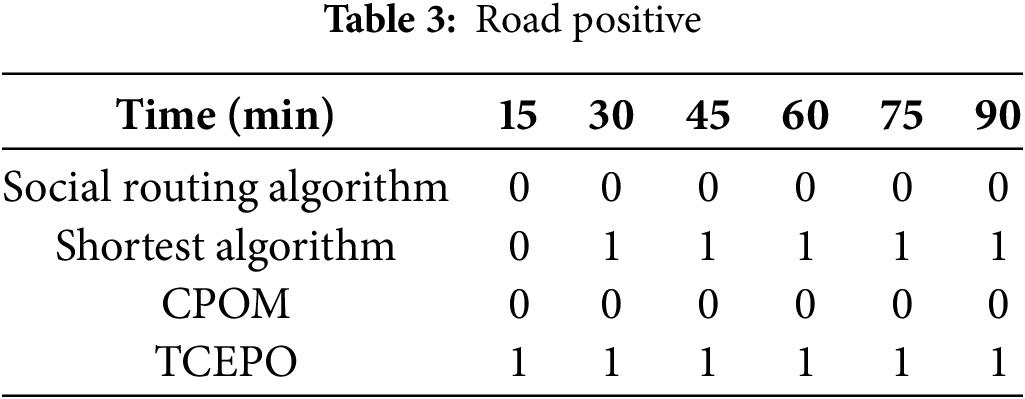

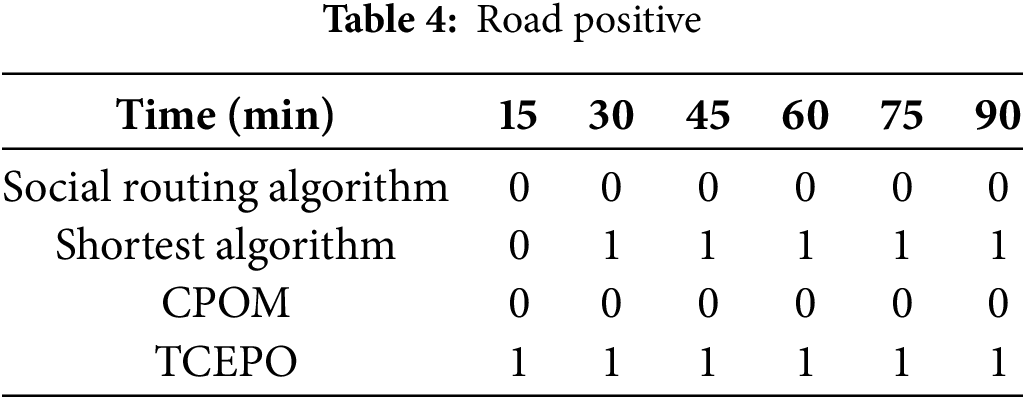

Concurrently, the proposed ACRABPG method and the four alternative methods underwent significance testing using the Origin software. Because the data did not follow a normal distribution, this study employed a non-parametric test for significance analysis. The null hypothesis stated that ACRABPG does not differ significantly from the other four methods, with a significance level of 0.05. Tables 3 and 4 present the simulation results, where 0 indicates no significant difference between the two methods and 1 denotes a significant difference.

The results presented in Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate that the proposed method exhibits no significant difference in skewness from the social routing and CPOM methods. However, its mean value is notably smaller—approximately 2.8 and 3.1 times lower than the social routing and CPOM methods, respectively. After 15 min of simulation, significant differences emerged between the proposed method and both the shortest path and TCEPO methods, indicating distinct data biases among these approaches. The effectiveness of the proposed method lies in its ability to redirect vehicles to uncongested sections while maintaining traffic efficiency, thereby preventing partial road congestion and low traffic flow on certain roads. This capability underscores the progressive nature of the method introduced in this study.

This study proposes a dynamic multi-vehicle routing method for road networks with varying traffic demands based on preference games. The collaborative routing problem for vehicle groups in a large-scale road network scenario is transformed into a collaborative decision-making problem at a micro-scale intersection. This transformation effectively reduces the complexity of modeling and solving the collaborative routing decision-making problem for vehicle groups in large-scale scenarios. Vehicles participating in road selection decisions at intersections were modeled using a population game approach. By categorizing vehicle types and assigning corresponding weights, the model balances the road network to accommodate priority traffic demands while enhancing general applicability. A rapid algorithm for solving the population game model was designed for specific scenarios, ensuring benefits for both individual vehicle and multi-vehicle cooperative operations. As a result, the proposed method improves the performance in terms of the average vehicle travel time, road network throughput, and road load balancing.

The approach presented in this study can be extended in several significant directions. First, this study focuses exclusively on the routing problem for connected vehicles. Future research could explore integrating this approach with signalization control to enable collaborative decision-making that considers both vehicle routes and signalized rights of way. Second, while this study evaluates vehicle movement efficiency, it does not account for key factors such as vehicle energy consumption. Future work should incorporate multiple performance metrics to enhance the applicability. In addition, subsequent research should investigate the proposed control approach in more complex intersection scenarios, including intersections with multiple legs and lanes per leg. Finally, improving the overall traffic performance by coordinating various vehicle types such as buses and lorries presents another promising avenue for future studies.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the laboratory of the School of Transportation Science and Engineering at Beihang University and the laboratory of the School of Electrical and Control Engineering at North China University of Technology for their support.

Funding Statement: This research was financially funded by the National Key Research and Development Program Project 2022YFB4300404.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jixiang Wang; data collection: Jing Wei; analysis and interpretation of results: Siqi Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Haiyang Yu and Yilong Ren. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zheng X, Huang N, Bai YN, Zhang X. A traffic-fractal-element-based congestion model considering the uneven distribution of road traffic. Phys A Stat Mech Appl. 2023;632:129354. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2023.129354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Vishnoi SC, Ji J, Bahavarnia M, Zhang Y, Taha AF, Claudel CG, et al. CAV traffic control to mitigate the impact of congestion from bottlenecks: a linear quadratic regulator approach and microsimulation study. ACM J Auton Transport Syst. 2024;1(2):1–37. doi:10.1145/3636464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hu J, Li X, Hu W, Xu Q, Kong D. A cooperative control methodology considering dynamic interaction for multiple connected and automated vehicles in the merging zone. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(9):12669–81. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3386200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Deng J, Wu X, Wang F, Li S, Wang H. Analysis and classification of vehicle-road collaboration application scenarios. Procedia Comput Sci. 2022;208:111–7. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.10.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Diderot CD, Bernice NWA, Tchappi I, Mualla Y, Najjar A, Galland S. Intelligent transportation systems in developing countries: challenges and prospects. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;224:215–22. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2023.09.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Shao C, Cheng F, Xiao J, Zhang K. Vehicular intelligent collaborative intersection driving decision algorithm in Internet of Vehicles. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2023;145:384–95. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.03.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang J, Yu H, Chen S, Ye Z, Ren Y. Heterogeneous traffic flow signal control and CAV trajectory optimization based on pre-signal lights and dedicated CAV lanes. Sustainability. 2023;15(21):15295. doi:10.3390/su152115295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yu H, Wang J, Ren Y, Chen S, Dong C. Signal control study of oversaturated heterogeneous traffic flow based on a variable virtual waiting zone in dedicated CAV lanes. Appl Sci. 2023;13(5):3054. doi:10.3390/app13053054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ishtiaque Mahbub AM, Malikopoulos AA. Conditions to provable system-wide optimal coordination of connected and automated vehicles. Automatica. 2021;131:109751. doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2021.109751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xie Y, Lu G, Zheng F, Cao P, Liu X. A hierarchical approach for integrating merging sequencing and trajectory optimization for connected and automated vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(7):7552–67. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3350708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wu Q, Xia X, Song H, Zeng H, Xu X, Zhang Y, et al. A neighborhood comprehensive learning particle swarm optimization for the vehicle routing problem with time windows. Swarm Evol Comput. 2024;84:101425. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2023.101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xu B, Li SE, Bian Y, Li S, Ban XJ, Wang J, et al. Distributed conflict-free cooperation for multiple connected vehicles at unsignalized intersections. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2018;93:322–34. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2018.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mak S, Xu L, Pearce T, Ostroumov M, Brintrup A. Fair collaborative vehicle routing: a deep multi-agent reinforcement learning approach. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2023;157:104376. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2023.104376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ma K, Liao S, Niu Y. Connected vehicles’ dynamic route planning based on reinforcement learning. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;153:375–90. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.11.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ahmed F, Huynh N, Ferrell W, Badyal V, Padmanabhan B. Vehicle re-routing under disruption in cross-dock network with time constraints. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;237:121517. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rosita YD, Rosyida EE, Rudiyanto MA. Implementation of dijkstra algorithm and multi-criteria decision-making for optimal route distribution. Procedia Comput Sci. 2019;161:378–85. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2019.11.136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang J, Niu H. A distributed dynamic route guidance approach based on short-term forecasts in cooperative infrastructure-vehicle systems. Transp Res Part D Transp Environ. 2019;66:23–34. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2018.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chauhan SS, Kumar D. Mode search optimization algorithm for traffic prediction and signal controlling using bellman-ford with TPFN path discovery model based on deep LSTM classifier. SN Comput Sci. 2023;4(5):686. doi:10.1007/s42979-023-02140-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xue D, Guo Y, Li N, Song X, He M. Cross-domain cooperative route planning for edge computing-enabled multi-connected vehicles. Comput Electr Eng. 2023;108:108668. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li T, Guo F, Krishnan R, Sivakumar A. An analysis of the value of optimal routing and signal timing control strategy with connected autonomous vehicles. J Intell Transp Syst. 2024;28(2):252–66. doi:10.1080/15472450.2022.2129021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ebrahimi D, Sudarshan G, Alzhouri F. BNART: a novel centralized traffic management approach for autonomous vehicles. In: 2024 20th International Conference on the Design of Reliable Communication Networks (DRCN); 2024 May 6–9; Montreal, QC, Canada. doi: 10.1109/DRCN60692.2024.10539171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang J, Pei H, Ban X, Li L. Analysis of cooperative driving strategies at road network level with macroscopic fundamental diagram. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2022;135:103503. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2021.103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang Y, Cai P, Lu G. Cooperative autonomous traffic organization method for connected automated vehicles in multi-intersection road networks. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2020;111:458–76. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2019.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ishtiaque Mahbub AM, Malikopoulos AA, Zhao L. Decentralized optimal coordination of connected and automated vehicles for multiple traffic scenarios. Automatica. 2020;117:108958. doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2020.108958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu Y, Zhang K, Hou B, Li Q, Feng J, Nguyen TMT, et al. Real-time traffic impedance and priority based cooperative path planning mechanism for SOC-ITS: efficiency and equilibrium. Simul Model Pract Theory. 2023;122:102683. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2022.102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jiang C, Fu J, Liu W. Research on vehicle routing planning based on adaptive ant colony and particle swarm optimization algorithm. Int J Intell Transp Syst Res. 2021;19(1):83–91. doi:10.1007/s13177-020-00224-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Typaldos P, Papageorgiou M, Papamichail I. Optimization-based path-planning for connected and non-connected automated vehicles. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2022;134:103487. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2021.103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lu J, Li J, Yuan Q, Chen B. A multi-vehicle cooperative routing method based on evolutionary game theory. In: 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC); 2019 Oct 27–30; Auckland, New Zealand. doi: 10.1109/itsc.2019.8917441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Batista SFA, Leclercq L, Menéndez M. Dynamic traffic assignment for regional networks with traffic-dependent trip lengths and regional paths. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2021;127:103076. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2021.103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Gore N, Arkatkar S, Joshi G, Antoniou C. Modified bureau of public roads link function. Transp Res Rec. 2023;2677(5):966–90. doi:10.1177/03611981221138511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lin K, Li C, Fortino G, Rodrigues JJPC. Vehicle route selection based on game evolution in social Internet of vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018;5(4):2423–30. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2018.2844215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Caprio DD, Ebrahimnejad A, Alrezaamiri H, Arteaga FJS. A novel ant colony algorithm for solving shortest path problems with fuzzy arc weights. Alex Eng J. 2022;61(5):3403–15. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2021.08.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wu J, Lin Y, Qi W. Timing co-evolutionary path optimisation method for emergency vehicles considering the safe passage. Transp A Transp Sci. 2023;25:1–33. doi:10.1080/23249935.2023.2253477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools