Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Label-Guided Scientific Abstract Generation with a Siamese Network Using Knowledge Graphs

Graduate School of Information, Production and Systems, Waseda University, Fukuoka, 808-0135, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Haotong Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4141-4166. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.062806

Received 28 December 2024; Accepted 01 April 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

Knowledge graphs convey precise semantic information that can be effectively interpreted by neural networks, and generating descriptive text based on these graphs places significant emphasis on content consistency. However, knowledge graphs are inadequate for providing additional linguistic features such as paragraph structure and expressive modes, making it challenging to ensure content coherence in generating text that spans multiple sentences. This lack of coherence can further compromise the overall consistency of the content within a paragraph. In this work, we present the generation of scientific abstracts by leveraging knowledge graphs, with a focus on enhancing both content consistency and coherence. In particular, we construct the ACL Abstract Graph Dataset (ACL-AGD) which pairs knowledge graphs with text, incorporating sentence labels to guide text structure and diverse expressions. We then implement a Siamese network to complement and concretize the entities and relations based on paragraph structure by accomplishing two tasks: graph-to-text generation and entity alignment. Extensive experiments demonstrate that the logical paragraphs generated by our method exhibit entities with a uniform position distribution and appropriate frequency. In terms of content, our method accurately represents the information encoded in the knowledge graph, prevents the generation of irrelevant content, and achieves coherent and non-redundant adjacent sentences, even with a shared knowledge graph.Keywords

A well-written abstract in a scientific paper enhances the understanding and dissemination of the research work. As a part of the academic writing system [1], text generation for scientific abstracts has garnered significant attention with the advancement of Natural Language Processing (NLP) technologies, aiming to assist researchers in drafting and refining their academic works [2]. As a type of text summarization task [3], the focus of generating a scientific abstract is on precisely summarizing the core content and producing a complete and logically rigorous paragraph structure. This involves structured sentences that follow a typical order, sequentially introducing the background, objectives, methods, and results [4].

Utilizing knowledge graphs (KGs) for text generation holds significant potential [5,6]. Knowledge graphs explicitly represent core content, making structured information more accessible for people to understand and control. They also serve as a unified intermediate form, allowing the input format (regardless of text length or whether it is text at all) to be disregarded, thereby enabling the generation of fixed-pattern text, which reduces training complexity for specialized models. Therefore, our work focuses on generating well-described content paragraphs based on existing knowledge graphs, ensuring these paragraphs adhere to the writing characteristics of a scientific abstract. Practically, people can overlook issues such as grammar and non-academic descriptions as long as they provide sufficient and explicit content to create a coherent and fluent scientific abstract.

A primary focus in graph-to-text generation is developing structure-aware models [7–9]. These models need to understand entities and relations and capture structural features. Meanwhile, some approaches [10–12] leverage the powerful generation capabilities of pre-trained language models (PLMs) by linearizing hierarchical knowledge as input, thereby transforming the graph-to-text generation into a text-to-text generation. Most of these efforts focus on sentence-level generation, but applying it to paragraph generation presents several issues: Firstly, entity repetition leads to unnatural expressions. In structure-aware models, an entity with multiple relationships is considered a central node and gets higher weights when computing attention in a transformer. This causes the entity to appear more frequently and prominently; for example, “The proposed method” repeatedly appearing at the start of sentences results in an unnatural paragraph. For models that linearize graph inputs, the discrete knowledge and the repeated entities can result in sentence fragments having similar meanings due to the lack of structural awareness. At the same time, as a fixed word combination, the entity needs to be adjusted according to the context of the paragraph, “The proposed method” is a substitute for a certain method, Still, it should not appear multiple times within a paragraph if this entity in a knowledge graph appears frequently (the case presented in [11]). These situations are common due to overemphasizing content consistency and lacking diverse expression. This leads to the second point: balancing content consistency and coherence within a paragraph. Generated sentences should not have overly similar meanings due to adjacent sentences sharing similar knowledge, nor should semantic separation occur due to discrete sentence knowledge. Especially in scientific abstracts, it is important to preserve the content expressed by the knowledge graph while also constructing a coherent and logical paragraph structure.

To address these issues, we first introduce label-guided text generation, where the entire paragraph knowledge graphs are used as input, and sentence labels are injected for paragraph segmentation to hard control the text structure and enrich its expression. Our model is a dual-task Siamese network [13], which employs encoder-decoder PLMs like BART [14], T5 [15], and FLAN-T5 [16] to capture the mapping between input and output better. These two tasks, graph-to-text generation and entity alignment, have complementary focal points in their generative capabilities. Graph-to-text generation involves producing relation-descriptive texts from specific entities and generalized relations. In contrast, entity alignment involves concretizing entities within texts using generalized entities from specific relation-descriptive texts. The training with shared parameters simultaneously enhances the concretization capabilities of both relations and entities, while improving sentence generalization and maintaining the coherence and consistency of the content. Fig. 1 shows an example of the generation process; the model is flattened in sequential order. The graph-to-text implementation enables content generation, followed by entity alignment, which focuses on adjusting entities according to the context to ensure paragraph coherence and avoid issues such as repetition. Our work focuses on generating abstract paragraphs in the field of NLP and computational linguistics, and our contributions are summarized as follows:

• We implement a simple approach to construct a KG-Text paired abstract dataset using abstracts from the ACL Anthology 1, expanding triples into quadruples by adding a sentence label element to mark the knowledge graph differentially and for label-guided text generation 2.

• We propose a method based on a Siamese network that achieves both graph-to-paragraph generation and entity alignment, guaranteeing the generation of a complete abstract while maintaining content consistency and coherence.

• The experiments on ACL-AGD demonstrate that our method enables the appropriate position distribution and frequency of entities within a paragraph. The label provides rhetorical information that guides the production of diverse expressions and contributes to a stable paragraph structure.

Figure 1: The generation process of the proposed method. On the left is the actual knowledge contained in a sentence from the paragraph, while on the right is the process from the initial input to the final generated output

2.1 Text Generation for Abstract

Text generation for abstract is a type of text summarization task [3], mainly focused on generating the abstract section of a scientific paper; models are built to generate a complete abstract by assembling the key information extracted from the input. The main difference among text generation tasks for abstract lies in the length of input data; they can be categorized into: document-based [17], paragraph-based [18], and sentence-based generation [19]. This also reflects the difference in information density, which is the proportion of useful information in the total text. For example, the information density in a document may be lower due to redundant or irrelevant information, whereas heuristic generation [19] based on associative ideas has a very high input information density. However, the knowledge graph explicitly represents key information, making the generation process more controllable and interpretable than the implicit extraction used in the text-to-text mentioned above generation methods. It also provides a high-density information expression and serves as a unified intermediate representation, allowing researchers to focus less on the length or format of the text. Moreover, the ease of storage and scalability of knowledge graphs and their various other benefits, open up numerous possibilities for future text generation [20]. Therefore, generating scientific abstracts requires leveraging the capabilities of knowledge graphs to achieve comprehensive and accurate summarization of complex research findings, facilitating better understanding and discovery within the scientific community.

The knowledge graph is composed of entities, relations, and structure. Such hierarchical structures are difficult for neural networks to capture and describe, so many efforts have focused on graph structure awareness [7–9]. Specifically, the methods would encode a graph’s neighborhood information and decode its corresponding textual representation. With the advent of PLMs such as BART [14] and T5 [15], these models have been directly adapted and fine-tuned for the graph-to-text generation task. Considering the limitations of sequence-to-sequence models in handling hierarchically structured graphs, leveraging PLMs requires the linearization of knowledge graphs. These approaches [10–12] directly shift the input from knowledge graph to text. While it may not enable a direct grasp of the knowledge structure, it significantly boosts the generated text output’s efficiency and quality. Most related work focuses on sentence-level generation, and even when training on databases that include paragraphs, such as Abstract GENeration DAtaset (AGENDA) [21,22], the output remains sequential at the sentence level. Consequently, these models lack a holistic understanding of abstract paragraphs, resulting in issues with readability and comprehension. Specifically, paragraph generation suffers from problems such as entity repetition, excessive semantic similarity, and lack of coherence. To address these, we implement a Siamese network to enhance graph-to-text generation. Due to the necessity of introducing sentence labels into the knowledge graph and aligning with the latest research abstracts, we construct ACL-AGD that pairs the knowledge graph with text. Following this, in this paper, we then detail the implementation process of the Siamese network, and the experiments validate the superiority of our method in generating abstract paragraphs, demonstrating improved content consistency and coherence.

The initial work is to extract knowledge graphs from abstracts in the field of NLP and computational linguistics. We introduce the ACL Abstract Graph Dataset (ACL-AGD), where the abstracts are derived from the ACL Anthology. The BibTeX database on the official site catalogs 84,220 publications in computational linguistics and NLP, encompassing a broad spectrum of ACL conference proceedings, journal articles, and contributions from non-ACL events, covering the period from 1965 to 2023. The abstracts in the ACL Anthology exhibit a technical, precise academic style. The detailed statistics of the dataset can be found in Section 5.1. The process involved two steps to meet our requirements: zero-shot learning for knowledge extraction and few-shot learning for sentence labeling.

3.1 Zero-Shot Learning for Knowledge Extraction

We utilized the Princeton University Relation Extraction (PURE) system [23] to construct the knowledge graph. The pre-trained model of PURE was trained on the SciERC dataset [22]. Its vocabulary was expanded to enhance coverage. The system utilizes a flexible text span estimation to predict entities, including six types (shown in Table 1): Task, Method, Generic, Metric, Material, or Other Scientific Terms. Once the entity types are predicted, the system estimates the relationships between the entities, which include Compare, Used-for, Part-of, Feature-of, Hyponym-of, Evaluate-for, and Conjunction (shown in Table 1). These relationships offer a clear understanding of the connections and dependencies among the entities in the knowledge graph.

3.2 Few-Shot Learning for Sentence Labeling

Labeling the sentences within the abstract is essential for assigning labels to the knowledge graph. A few-shot learning approach trains a BART-based classifier [14]. The training data is sourced from the CS Abstracts Dataset [4], which consists of 654 abstracts specifically about the field of computer science, collected through crowdsourcing and collective intelligence. The sentences within these abstracts are categorized into five classes (shown in Table 1): Background, Objective, Methods, Results, and Conclusion. We provide automatic labeling for each knowledge point based on the classification results of the previous five classes. The labeling pipeline operates under a fixed model configuration, guided by a minimal set of labeled examples from the CS Abstracts Dataset [4]. During deployment, the model computes confidence scores for each class, selecting the highest-confidence label as the final assignment. By standardizing label definitions and maintaining a consistent model setup, this process ensures reproducibility and guarantees consistent performance at scale.

We ascertain the reliability of the automatic labeling process by having two Large Language Models (LLMs) independently perform the same labeling task. We consider these LLMs, Deepseek-V2-16B and Gemma2-9B, as additional judges and compute the inter-annotator agreement between our automated labeling pipeline and these additional judges under the same label definitions and a small set of example-based prompts. This setup was applied to 500 validation examples. We then aggregated the outputs from these models and calculated Fleiss’ Kappa to measure the inter-annotator agreement, indicating how strongly different annotation sources converge beyond chance. Our final Fleiss’ Kappa score of 0.64 suggests a meaningful level of correlation among the models, indicating that the labeling process are reasonably reliable.

4 A Siamese Network for Graph-to-Text Generation

In an abstract, the knowledge graph is represented as a set

This form of controlled text generation is frequently observed in the style transfer task [24]. Our work deviates from the opposing text style transfer,

Our input consists of an entire paragraph of knowledge graphs segmented using sentence labels. The format needs to be designed accordingly to ensure alignment between input and output. First, special tokens divide the target sentence

As shown in Table 2, and are special tokens for marks of the label and sentence. To better align the mapping

As illustrated in Fig. 2, a dual-task Siamese network model performs two main tasks: graph-to-text generation and entity alignment. The network leverages pre-trained language models built on the encoder-decoder frameworks of BART, T5, and FLAN-T5, we name them as Siamese-BART, Siamese-T5, and Siamese-FLAN. Previous researches [10–12] have shown that these models possess a notable ability to adapt to graph-to-text tasks.

Figure 2: An overview of the Siamese network. The text generation processes for training and testing are distinguished by blue and red, respectively. During training,

A flattened generation process is implemented during the test as outlined in Eq. (2). The input is a linearized paragraph knowledge graph

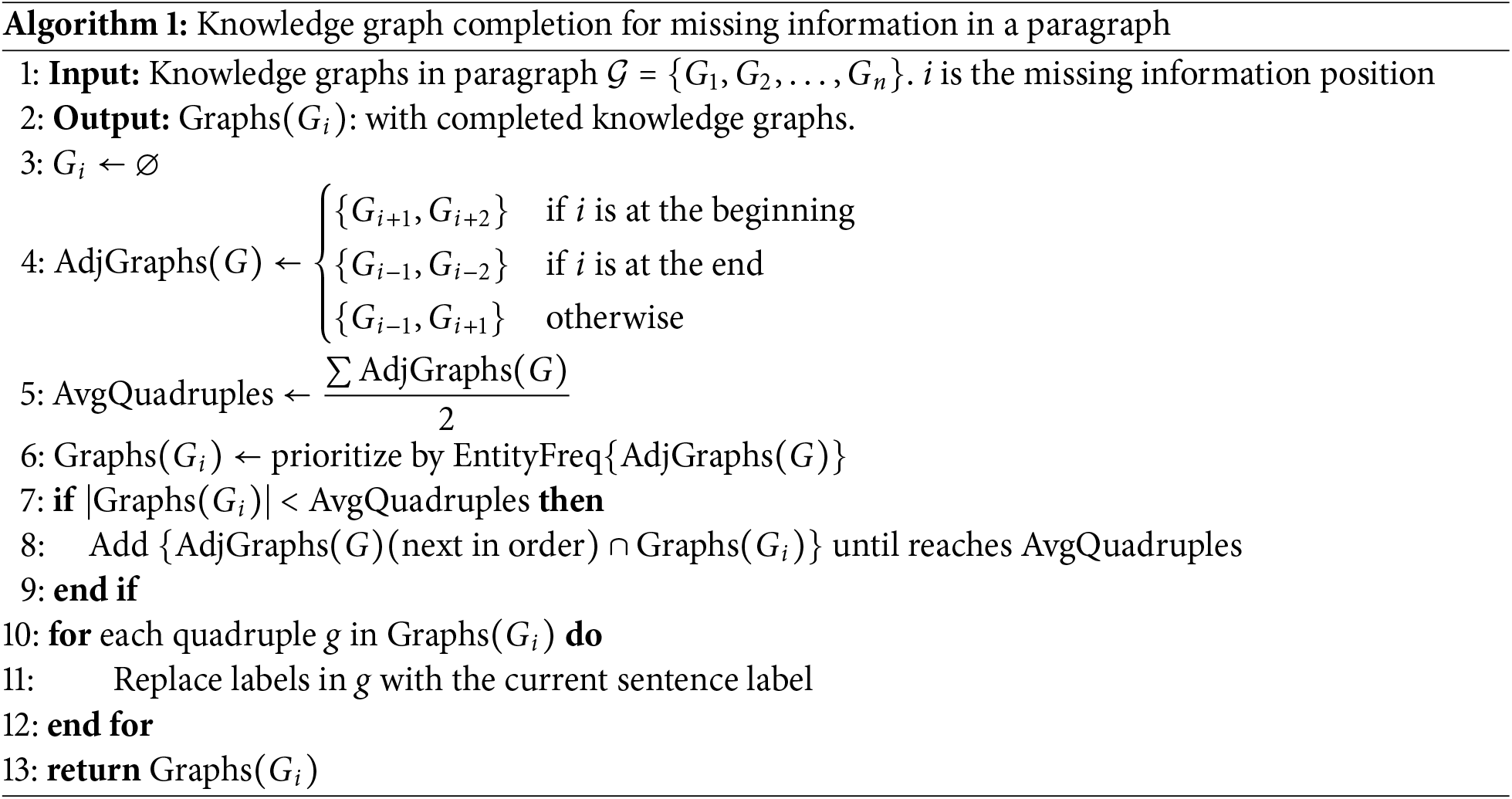

Knowledge Graph Completion: We adopt a zero-shot learning method to extract knowledge graphs. Still, it does not rely on retraining the model, causing some texts not to adapt to the task, which results in difficulties in entity extraction and relation recognition, leading to some sentences lacking corresponding knowledge graphs. This paper will complete the knowledge within the paragraph to address the issue of paragraph coherence caused by missing information. This work is inspired by the paragraph completion task [28], where adjacent sentences share certain information to maintain coherence.

We designed an Algorithm 1 to extract adjacent knowledge graphs. First, the positions of the adjacent sentences are located based on the position

Our training is based on linearized discrete knowledge and does not provide the structural information of the knowledge graph, which enables the model to adapt to randomly assembled knowledge. Additionally, using sentence labels to guide diverse sentence expressions and adjusting for entities reduces semantic repetition issues between adjacent sentences, even when sharing knowledge graphs.

Table 3 presents the statistics for ACL-AGD. By filtering, 35,063 abstracts were obtained, excluding non-English articles and those without extracted abstracts. These abstracts comprise 189,601 sentences, each corresponding to an equal number of sentence labels, with an average of 5.41 sentences per paragraph. In total, 552,749 entities were extracted, averaging 15.76 entities per abstract. In addition, these abstracts collectively contain 258,394 relations (quadruples), averaging 7.37 per abstract.

Fig. 3 illustrates the distribution of the number of sentences, relations, and entities within an abstract. We find that 812 abstracts (2.3% of the total) do not produce any knowledge graph, and 42 abstracts (0.1% of the total) do not deliver any entity, indicating that identifying entities does not necessarily imply obtaining knowledge graphs. Because a quadruple contains two entities, it is reasonable that the average number of entities in an abstract is approximately twice that of relations. The number of sentences should correlate with the number of knowledge graphs. The more sentences there are, the more knowledge graphs can potentially be extracted. Fig. 3 shows that the count of abstracts in terms of sentences and the count of abstracts in terms of relations follow a similar trend, validating the sustainability and stability of the method applied for extracting knowledge graphs.

Figure 3: Distribution of the number of sentences, graphs, and entities within an abstract, indicating the maximum, minimum, and average values for the corresponding attributes

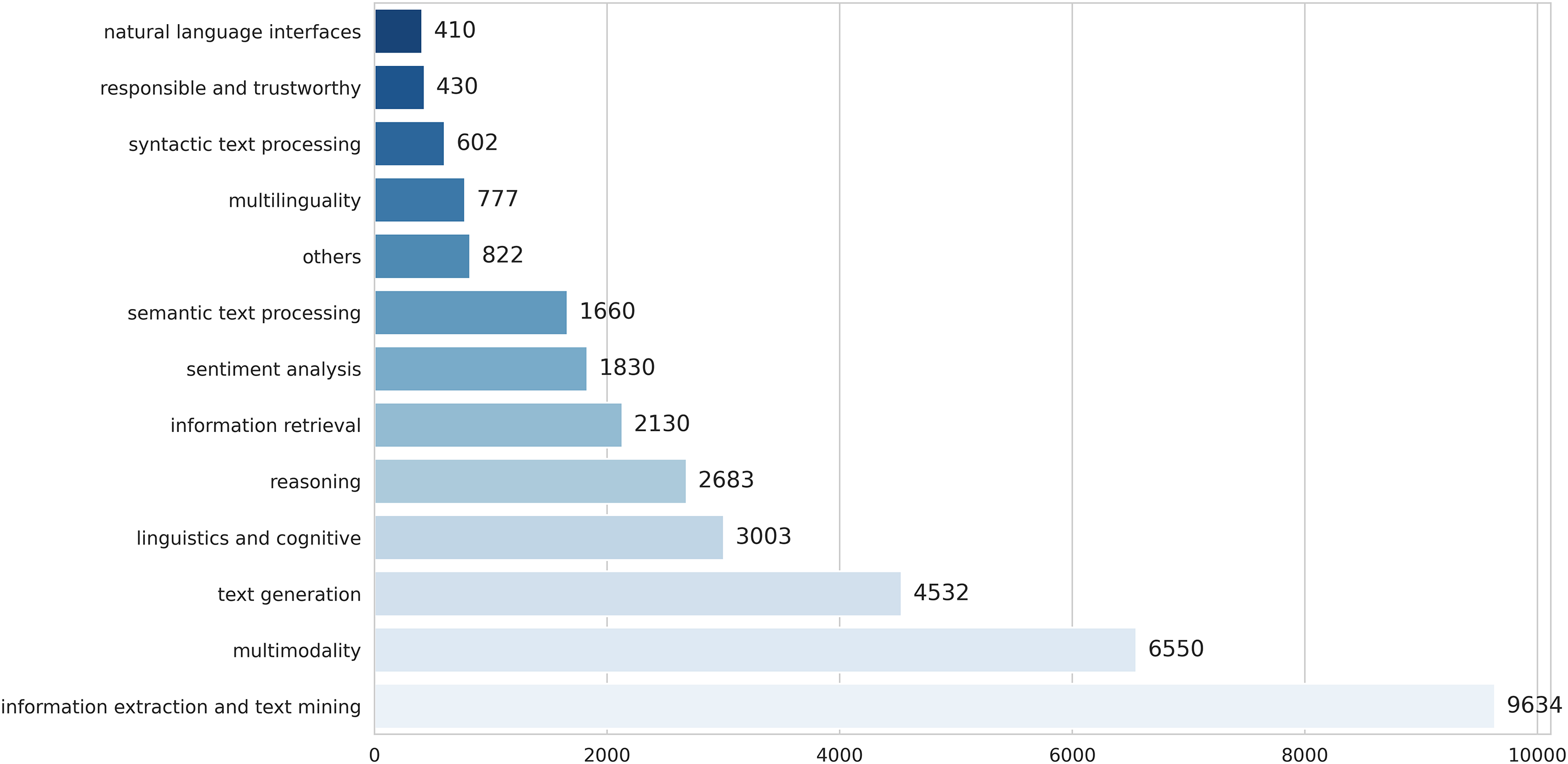

Based on the Taxonomy of Fields of Study in NLP [29], we classify the abstracts into 13 fields, with the results shown in Fig. 4. The category “Others” includes abstracts that could not be confidently assigned to any specific field. The classification is performed using DeepSeek V2-16B.

Figure 4: Distribution of research fields in ACL-AGD

The experiments were conducted on ACL-AGD, with the train/test/dev randomly split into 33063/1000/1000. Our models were trained on two Nvidia RTX A6000 GPUs (48 GB each). The training process was conducted with the following hyperparameters: a learning rate of 3e-5, 30 training epochs, a batch size of 2, a maximum sequence length of 512, a beam size of 4, and a repetition penalty of 2.0. Following related work [11], we employed Supervised Task Adaptation (STA) training before fine-tuning our model to enhance its domain-specific text understanding. Instead of using a knowledge graph (KG) as input, the model was trained with target texts containing 15% masked tokens, aiming to reconstruct the original domain-specific text as output.

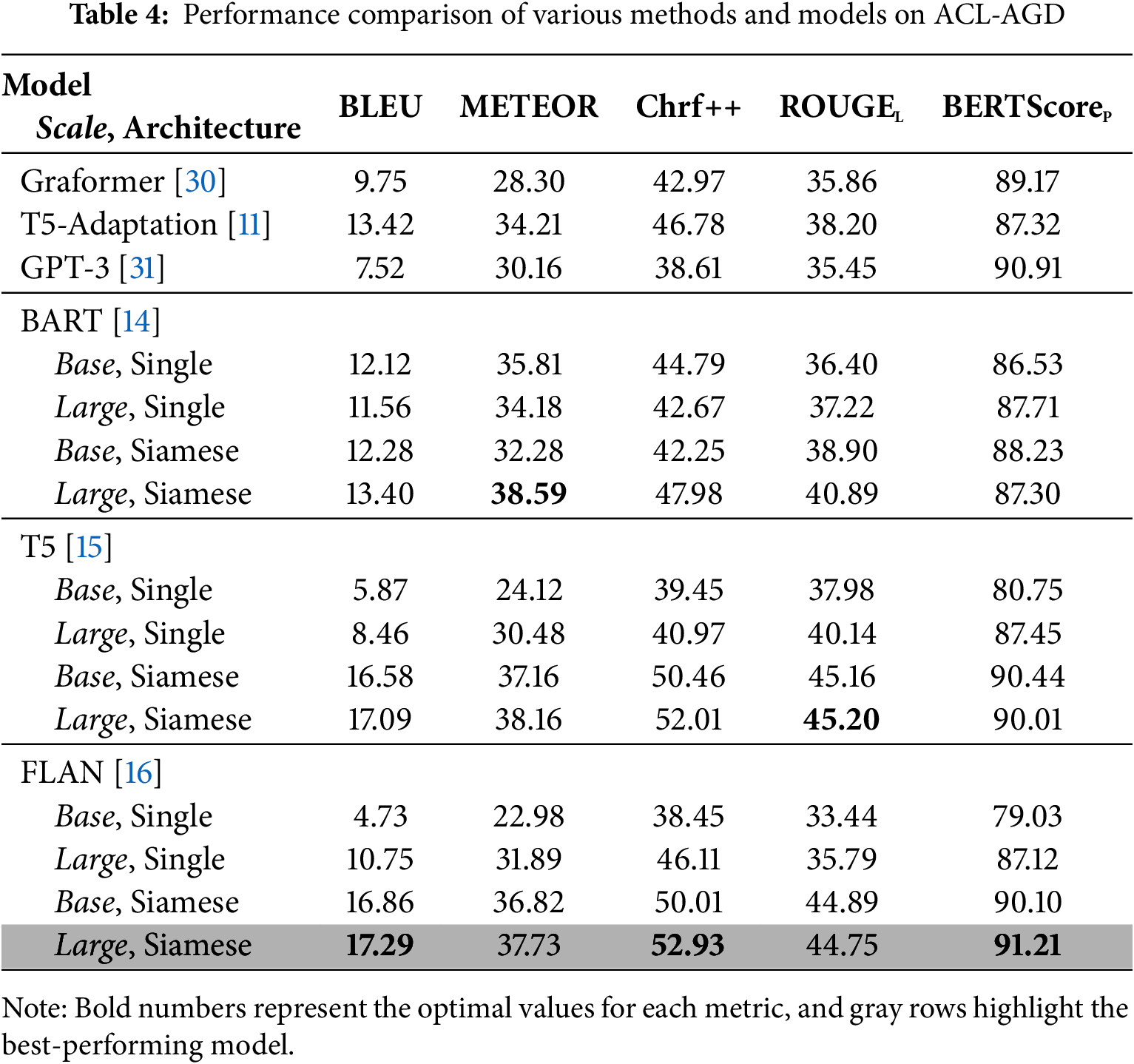

Baselines: For our experiments, we employed Siamese models using base and large variants of BART [14], T5 [15], and FLAN-T5 [16], with model parameters obtained from Huggingface’s GitHub 3. BART is a transformer-based model trained with a denoising objective, making it well-suited for text generation and summarization. T5 treats all NLP tasks as text-to-text transformations, offering a versatile approach to tasks like translation and question answering. FLAN-T5 extends T5 by incorporating instruction tuning, allowing it to generalize better across different tasks, especially in zero-shot and few-shot settings. As baseline models, we included those trained directly on ACL-AGD, meaning they mapped the linearized knowledge graph directly to text. We also retrained the Grafomer [30], which leverages shallow networks to capture global structural patterns. T5-Adaptation [11] incorporates task adaptation for optimizing text generation from linearized knowledge graphs and uses PLMs such as BART and T5. We selected the optimal T5-large model from this paper. This model had been fine-tuned on the AGENDA dataset [21,22], and we further fine-tuned it on ACL-AGD. In addition, as another baseline to evaluate the capability of a general-purpose large language model for our task, we investigate the performance of a GPT-based model. We adopt the prompt design and parameter settings of [31], which examines GPT models in graph-to-text generation, and apply them to our ACL-AGD dataset.

Evaluation Metrics: We followed previous work [8,11] and primarily measured the similarity between the generated and reference texts. The evaluation metrics utilized, implemented using Hugging Face’s evaluate library, are BLEU-4 [32], which calculates n-gram precision with a brevity penalty to balance fluency and accuracy; METEOR [33], which incorporates synonym matching and stemming for a more flexible evaluation; chrF+ + [34], a character-level F-score metric well-suited for morphologically rich languages; and ROUGE-L [35], which measures recall based on the longest common subsequence. In addition, we employ BERTScore’s precision [36] to evaluate the semantic similarity of texts, aligning meaning rather than exact wording using contextual embeddings.

The results, as shown in Table 4, illustrate the different performance in generation quality across various methods and models. Both Graformer [30] and T5-Adaptation [11] validate the effectiveness of our ACL-AGD, demonstrating that knowledge extraction under zero-shot learning can effectively describe the corresponding text. Moreover, the performance of pre-trained language model [11] exceeds that of non-pretrained language model [30]. GPT-3 [31] achieves a relatively high BERTScore (90.91), indicating strong semantic alignment with reference texts. However, as a non-finetuned model, its BLEU score (7.52) and ChrF++ (38.61) are the lowest among the models, suggesting that while prompt-based generation preserves meaning, it lacks lexical precision and surface-level similarity to the target abstracts. Single-BART, Single-T5, and Single-FLAN represent models trained only for graph-to-text generation, with the input being quadruple knowledge graphs. Compared to our method, these models do not incorporate knowledge completion and entity alignment. However, Single-T5 and Single-FLAN produced the poorest results because the input is a sequence of paragraph knowledge graphs rather than being split into individual sentences. They excel at generating continuous long texts, which, for our task, leads to the generation of much irrelevant content, as a single sentence label can result in multiple sentences. In contrast, BART-based models do not exhibit this issue.

Furthermore, when training the Siamese network, the model, with shared weights for entity alignment, effectively restricts the generation of overly long texts, and the output sentence format aligns well with the designed input format of this paper. Fig. 5 presents the statistical distribution of the number of sentences in the output generated by various models. The Siamese-T5-large and T5-Adaptation models exhibited significant fluctuations in the number of sentences generated, though the Siamese network structure partially mitigated this variability. Conversely, Siamese-BART-large models consistently produced a lower range of sentence counts, demonstrating a propensity for generating more concise text. Remarkably, the Siamese-FLAN-large model maintained a moderate and stable range of sentence counts, highlighting its superior stability and consistency, making it particularly well-suited for tasks requiring reliable output.

Figure 5: The distribution of sentence count in outputs from different models

In our method, T5-based models outperform BART-based models and significantly exceed the performance of the Grafomer and T5-Adaptation models. In Table 4, the bolded numbers represent the best values for the corresponding metrics. Siamese-FLAN-large demonstrates optimal performance, achieving the highest BLEU-4, Chrf++, and BERTScore. These metrics demonstrate that our method’s output is closer to the reference, providing preliminary evidence of its advantage in content consistency. However, excessive consistency is not always desirable, so further investigation into content coherence and related issues is needed.

5.4 Evaluating Content Coherence with Entities

In this part, we will analyze paragraphs from the perspective of entities, focusing on two main aspects: frequency and position distribution. We first assume that entities have a strong correlation with semantic content. If an entity appears consecutively in adjacent sentences, this can be considered an indication of content coherence. However, there should be an appropriate frequency: an entity should not appear too frequently within a sentence for content consistency, nor should it be too dispersed to maintain content coherence. For graph-to-text generation, the frequency should be comparable to the reference text’s. Too low a frequency results in information loss, while too high a frequency leads to redundancy.

Fig. 6 is an intuitive example that demonstrates the frequency and positional information of entities within a paragraph, comparing the models Graformer [30] and T5-Adaptation [11], our method (Siamese-FLAN-large), and the reference. The top four figures show the “Entity Frequency Ratio”, which measures the ratio of an entity’s frequency in the paragraph to its frequency in the knowledge graphs. The bottom four figures show the “Entity Grid”, which illustrates the position of an entity in the sentences along with its frequency. In summary, our entity frequency ratio (b1) is closer to the reference (a1). Although the position distribution of Graformer (c2) is more similar than ours (b2) when compared to the reference (a2), ours (b2) shows the consecutive occurrence of entities in adjacent sentences. While (d2) may indicate content coherence, it also reflects redundancy and high repetition of entities.

Figure 6: An example comparing the entity frequency ratio (top) and the entity grid (bottom) for the reference and the outputs of Siamese-FLAN-large, Graformer [30], and T5-Adaptation [11]

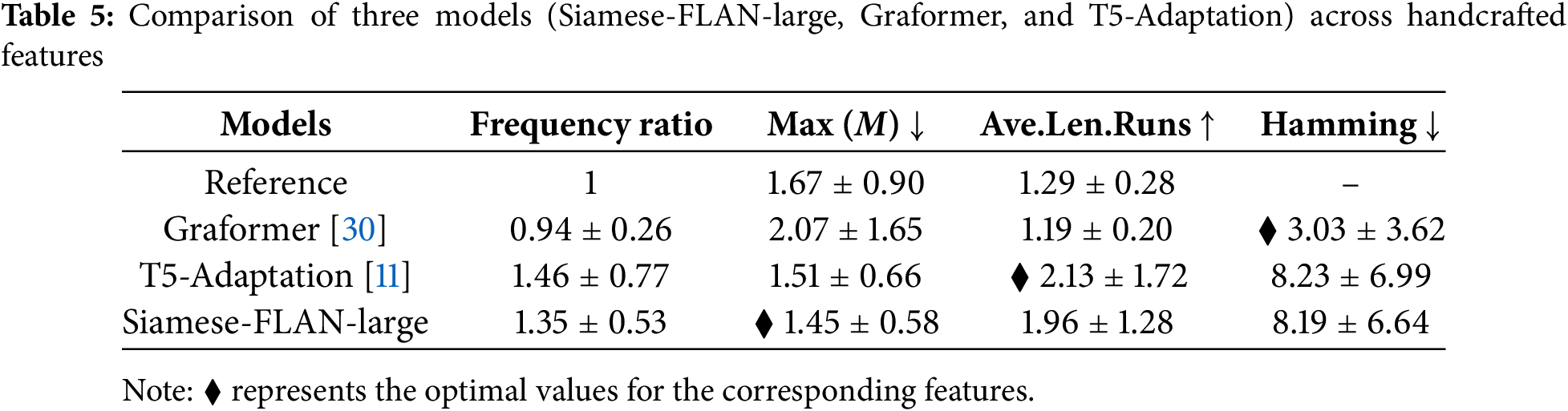

To better quantify these analysis examples, we design four handcrafted features based on the entity grid matrix

1. The frequency ratio,

2. The maximum frequency,

3. The average length of runs. Runs refer to groups of consecutive identical elements in each column of M (representing an entity). This can identify the occurrences of an entity in adjacent sentences, thereby measuring content coherence. The average length of consecutive identical elements measures how many sentences, on average, an entity spans consecutively.

4. Hamming distance,

Table 5 shows the performance of the three models on our handcrafted features. Graformer [30] achieved the smallest Hamming distance, indicating a similar entity position distribution to the reference text. However, it has a frequency ratio of 0.94, which is less than 1, indicating information loss and sparse position distribution. At the same time, it has the highest maximum frequency, implying that situations like those in Fig. 6 (c2) often occur, where a single sentence has a high repetition of an entity due to the model’s tendency to maintain content consistency excessively. Furthermore, the lowest average length of runs value indicates that entities do not appear consecutively in adjacent sentences. Coupled with the previously analyzed information loss, this suggests that the paragraphs generated by Grafomer [30] lack coherence.

The results of T5-Adaptation [11] have strong content coherence, with the most extended average run length. However, this leads to information redundancy because, although the maximum frequency of entities is similar to our method, the high-frequency ratio means that entities are highly repetitive throughout the paragraph, which also indicates that the entity distribution is too uniform, as exemplified in Fig. 6 (d2), the entity “isotropy calibration” appearing consecutively in six sentences is unreasonable.

Our method demonstrates a strong ability to balance content consistency and coherence. While our average length of runs is not as high as T5-Adaptation’s, it is around 2, indicating that an entity frequently appears in two adjacent sentences, leading to a uniform and reasonable position distribution. Our entities’ frequency is higher than the reference text, but we perform entity alignment, which leads to a reduction in the maximum entity frequency. The content determines the substituted entity and falls within an appropriate frequency range. Therefore, our method ensures a robust uniform position distribution and appropriate entity frequency range, maximizing content and paragraph structure integrity.

5.5 Evaluation of Linguistic Quality and Diversity

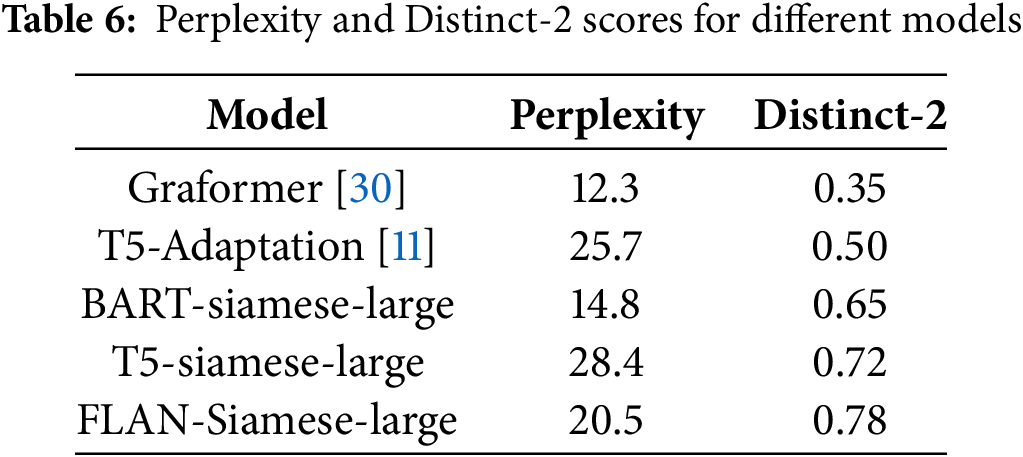

This part assesses the quality and diversity of the generated text using Perplexity and Distinct-2. Perplexity evaluates fluency and coherence by measuring the inverse probability of a text under the language model, normalized by word count. Lower values indicate more predictable and natural text (1–10: fluent, 10–50: reasonable, 50+: unnatural). Distinct-n quantifies lexical diversity by computing the ratio of unique n-grams to the total number of n-grams in the text. A higher Distinct-n value indicates more varied expressions, while a lower value suggests repetitive patterns.

As shown in Table 6, FLAN-Siamese-large achieves the highest lexical diversity (Distinct-2: 0.78) while maintaining a competitive perplexity (20.5), demonstrating its ability to generate varied and less repetitive text without a significant loss in fluency. Compared to other models, Graformer shows the lowest perplexity (12.3) but suffers from severe redundancy (Distinct-2: 0.35). T5-siamese-large, despite its high diversity (Distinct-2: 0.72), has the highest perplexity (28.4), indicating lower confidence in generation. BART-siamese-large offers a more balanced performance (Perplexity: 14.8, Distinct-2: 0.65) but does not surpass FLAN-Siamese-large in diversity. These results highlight FLAN-Siamese-large as the most effective model in producing diverse yet fluent text, making it a strong candidate for graph-to-text generation.

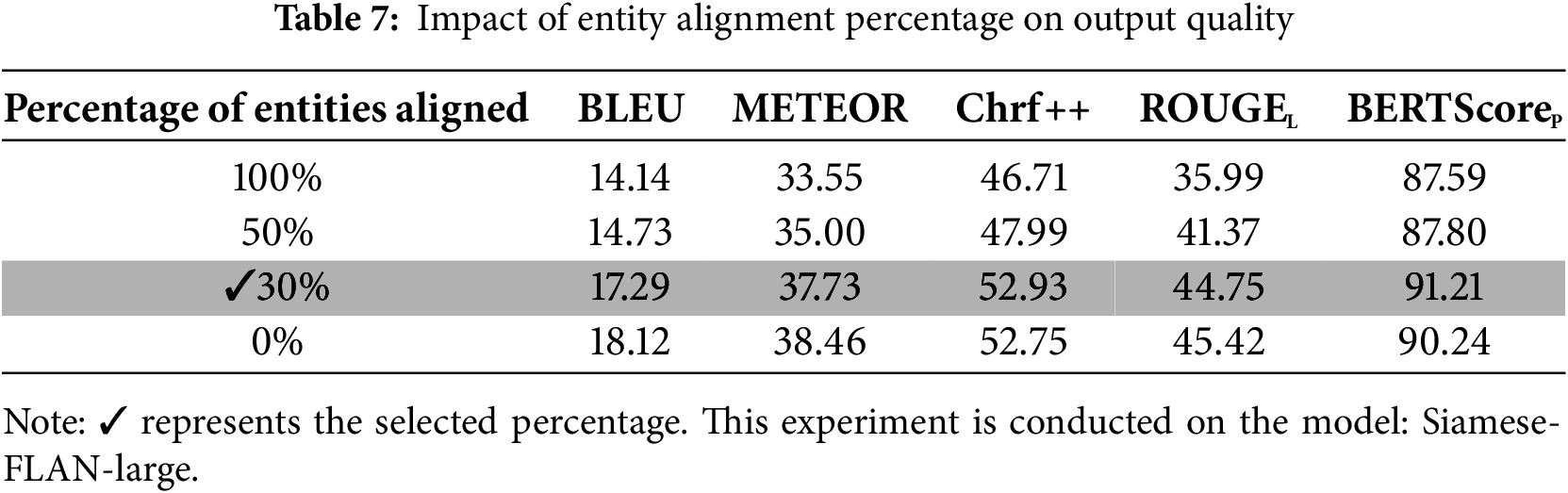

Entity alignment: Here, we aim to validate two aspects: (1) whether the percentage of entities selected for alignment affects the quality of the generated text and (2) what is the level of similarity between the aligned entities?

Table 7 illustrates the impact of different alignment percentages on the quality of the generated text using the Siamese-FLAN-large model. During training, 100% of entities were aligned to enhance the model’s generalization ability. However, an excessively high replacement percentage during testing can alter the context. If any of the preceding entities deviates, it can cause the entire sentence to deviate. We tested four thresholds, 0%, 30%, 50%, and 100%, with 0% representing no alignment and 30% ensuring that at least one entity per paragraph is aligned. As indicated in Table 7, when the percentage is 0% or 30%, the difference in the generated paragraphs is minimal. A small amount of replacement does not significantly affect semantic content. However, if half or all entities are aligned and replaced, the similarity to the reference is severely reduced, indicating that an excessive percentage of entities selected for alignment significantly impacts the quality of the generated text.

We also measured the average similarity of aligned entities using Sentence-BERT [37] by calculating their cosine similarity (ranging from 0 to 100). As shown in Fig. 7, we tested three models: Siamese-BART-large, Siamese-T5-large, and Siamese-FLAN-large. At the same percentage of alignment, these models exhibited similar alignment capabilities, with only minor differences in average similarity. However, as this percentage increases, the aligned entities become increasingly dissimilar to the original entities. When reaching 100%, Siamese-T5-large only achieved an average score of 58. Excessive replacement leads to content generalization in sentences, thereby impacting the accuracy of identifying similar entities. Therefore, we adjusted 30% of the entities during the generation process, as high similarity in experiments demonstrated the effectiveness of this level of entity alignment.

Figure 7: The average similarity of aligned entities and performance variation for Siamese-BART-large, Siamese-T5-large, and Siamese-FLAN-large across different alignment percentages

Sentence label and knowledge completion: Our proposed method involves two preprocessing steps for the input of knowledge graphs. First, the sentence label in the quadruple serves as a prompt to guide the model in generating sentences with corresponding sentence features. Second, to address the problem of incomplete knowledge graphs, knowledge completion is performed to fill in the missing information. Therefore, we investigate the impact of these two preprocessing steps on the generation results, results shown in Table 8. Adding a label prompt and performing knowledge completion significantly improves these scores. The absence of knowledge graphs within a paragraph results in incomplete or randomly generated text, leading to lower metrics. Compared to results generated without label prompts, the performance is significantly worse. This is because the label provides rhetorical information rather than semantic information. It can guide the sentence to produce diverse expressions but cannot help with content completion and association. Diverse expressions result in the generation of typical lexical bundles [38] in the text. For example, “we propose” is commonly found in the “Methods”, and “our experiments show” is typical in the “Results”. Texts with these lexical bundles further improve the scores.

As introduced in the data construction for ACL-AGD, a BART-based classifier was trained using the CS Abstracts Dataset [4] to label our knowledge graphs. This classifier here aims to evaluate whether adding labels can help the model generate sentences with corresponding features. Without labels and with only knowledge completion, the generated sentences matched the reference labels only 56.12% of the time. However, by adding labels, this probability increased to 89.45% and 86.17%, thereby demonstrating that prompts can significantly influence sentence expression, but the prerequisite is that these expressions must be discernible. Furthermore, the model was trained to predict the masked label in

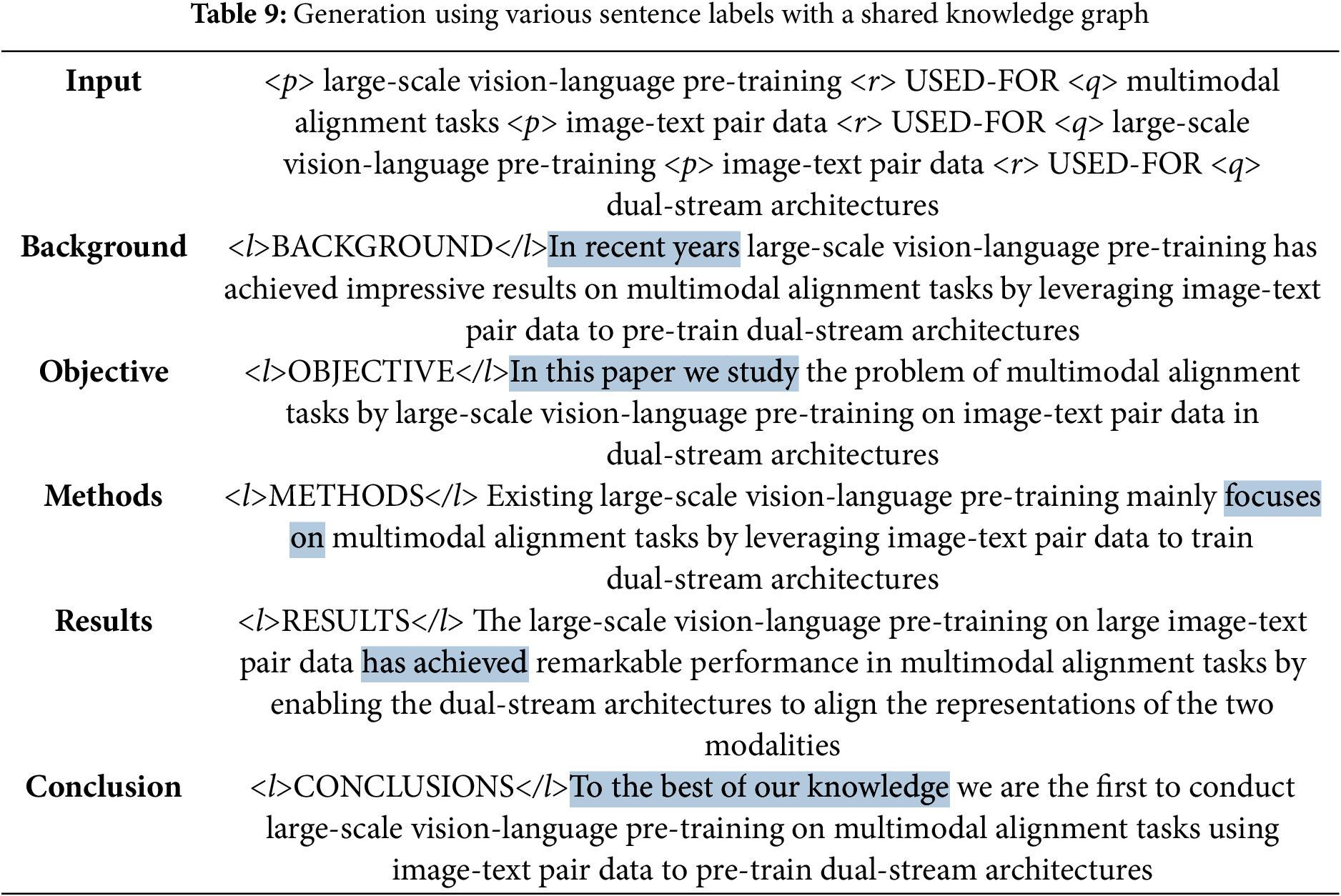

In this part, we present illustrative examples comprising three cases: generation guided by different sentence labels under the same knowledge graph, an overall comparison of the generated outputs and the generation process.

Generation based on sentence labels using a shared knowledge graph: As shown in Table 9, the model can generate different texts with different modes of expression in the text under the guidance of labels. These texts accurately convey the knowledge structure and relationships; the key difference lies in the additional rhetorical information provided by the labels. For example, “In recent years” is a specific form of expressing background information. In the “Objective” section, the simply present tense “we study” is used, while in the “Results” section, the present perfect tense is employed. These variations align with the characteristics of the corresponding sentences. This demonstrates that even with highly similar knowledge, our method can maintain coherence rather than produce similar sentences.

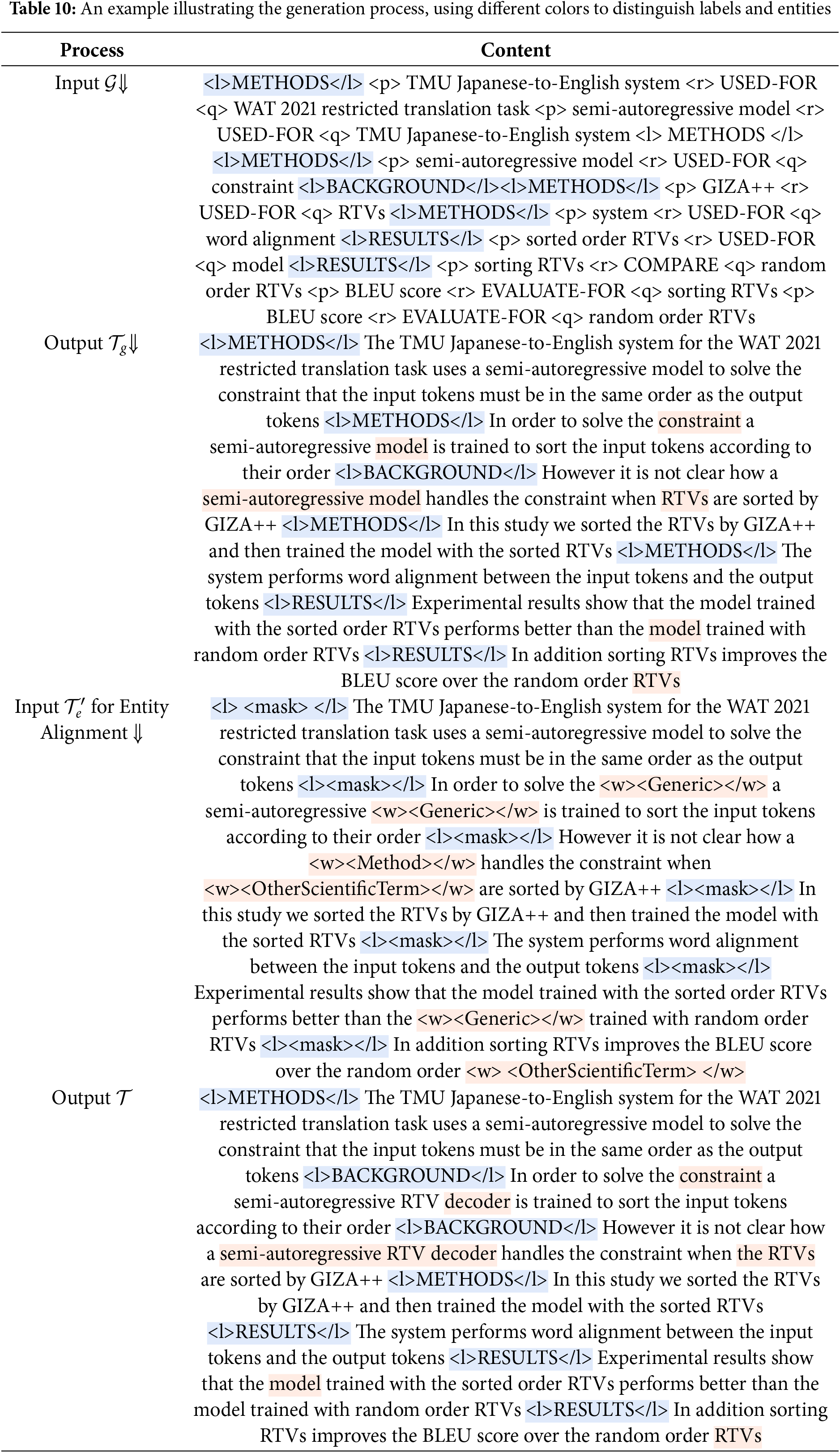

Generation process: Our text generation process follows:

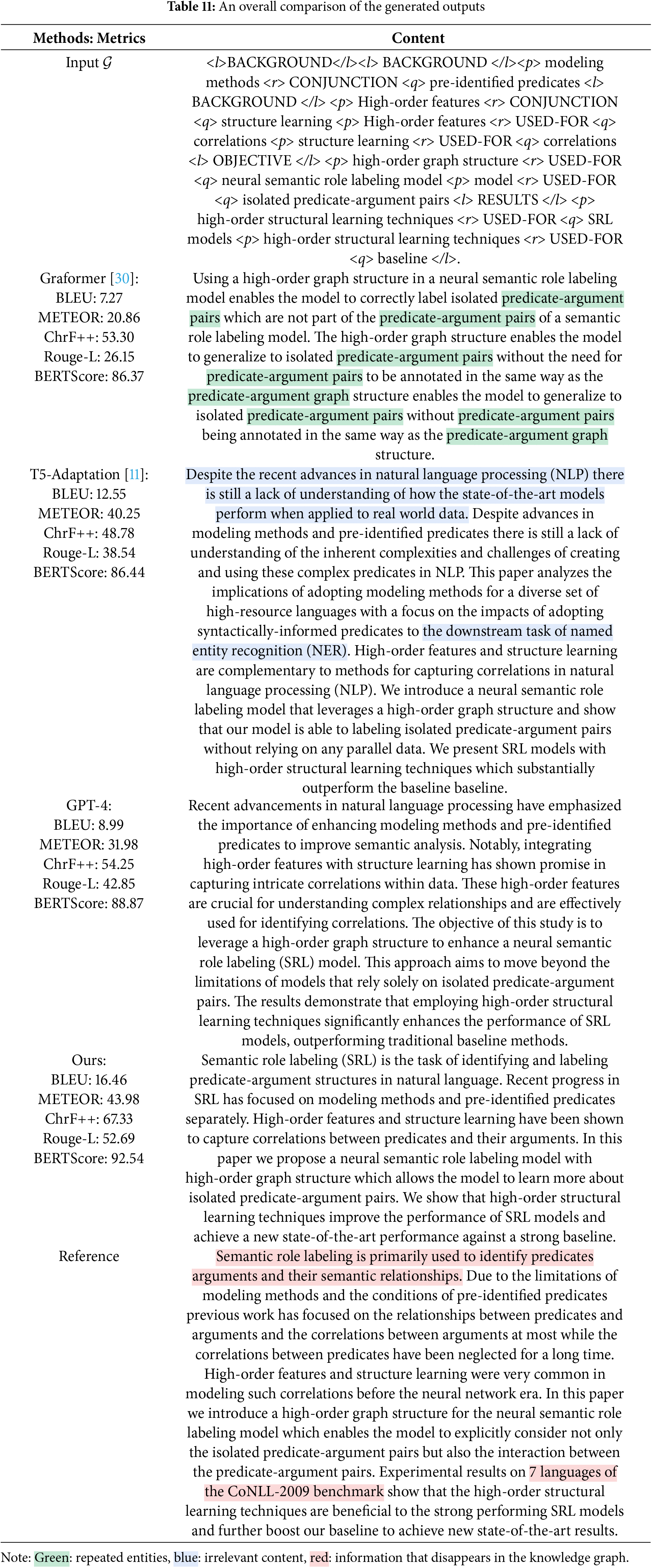

An overall comparison of the generated outputs: Table 11 presents comparative results from Graformer [30], T5-Adaptation [11], GPT-4 4, and our proposed method, along with the actual reference. A GPT-4 model has been customized for generating scientific abstracts with a specific prompt. Its generated structure is highly organized, but it tends to deviate from the content in terms of meaning, especially in the first sentence when lacking knowledge graphs. Meanwhile, Grafomar generates many repeated entities, and T5-Adaptation produces irrelevant content with paragraph structures that are also unreasonable. Our results are closer to the actual reference despite some missing knowledge (the red indicates the information missing from the knowledge graphs in the reference). However, our results demonstrate reliability, reducing content redundancy compared to the baselines. Our model can generate a variety of sentence structures, maintains logical coherence, and ensures smooth transitions between paragraphs, aligning well with the characteristics of abstract writing.

5.8 Discussion and Research Limitations

Noise and Incompleteness in Knowledge Graphs: Noisy quadruples may arise from incorrect entity linking or relation misclassification, leading to hallucinated content in the generated abstracts. Conversely, missing quadruples can result in incomplete summaries, particularly when key background information or experimental results are absent. A preliminary analysis of the extracted knowledge graphs (as presented in Section 5.1) indicates that approximately 2.3% of abstracts in ACL-AGD lack any associated knowledge graph, highlighting potential issues of missing or inconsistent information. While we are currently unable to systematically quantify erroneous information, future work could explore potential mitigation strategies. For instance, graph inference techniques [39] could be employed to infer implicit relationships and enhance the completeness of the knowledge graph, while external knowledge integration [40] could supplement missing quadruples using structured knowledge sources.

Challenges in Domain Adaptation: This study focuses on the generation of scientific abstracts within the academic domain. When adapting graph-to-text generation to other domains, two key challenges must be addressed. First, labels, which structure the logical flow of the generated paragraph, need to be redefined. In other tasks, these labels could take the form of either textual descriptions or ordered terms that guide the generation process. Second, our entity alignment strategy relies on special tokens to mask information, facilitating content prediction. However, in other domains, a standardized masking approach using unified special tokens could be directly applied. The effectiveness of this alternative strategy remains an open question and warrants further investigation.

Limitations of the Siamese Network: Our study employs a Siamese network architecture for graph-to-text generation and entity alignment; however, this approach introduces notable limitations. One major drawback is the increased computational complexity resulting from the multi-task learning framework and the additional similarity computation step, which can be incredibly challenging when mapping complex graph structures into textual representations. Moreover, the network’s performance heavily depends on the selection of negative samples, and given the substantial semantic differences among data samples, randomly generated negatives may not adequately capture the nuanced relationships, potentially distorting the training process and leading to suboptimal results in both graph-to-text generation and entity alignment tasks.

This paper explores the use of knowledge graphs for scientific abstract generation, with a focus on maintaining content consistency and coherence. Through the development of the ACL Abstract Graph Dataset (ACL-AGD), we introduced a structured method to align knowledge graphs with text, utilizing sentence labels to guide text organization and improve expressive diversity. We introduced a Siamese network to enhance entity and relation concretization within paragraphs by addressing the tasks of graph-to-text generation and entity alignment. Our experimental results indicate that our method produces logical paragraphs with uniformly distributed and appropriately frequent entities. The generated content accurately reflects the information in the knowledge graph, avoiding irrelevant content and maintaining coherence and non-redundancy between adjacent sentences. These findings underscore the potential of integrating knowledge graphs with advanced neural network architectures to produce high-quality, coherent, and consistent scientific text.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization of this study, Methodology, Experimentation, Formal analysis, Software: Haotong Wang; Research topic, review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision: Yves Lepage. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on the website: http://lepage-lab.ips.waseda.ac.jp/projects/scientific-writing-aid/ (accessed on 31 March 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

2Our dataset is publicly available at http://lepage-lab.ips.waseda.ac.jp/projects/scientific-writing-aid/ (accessed on 31 March 2025).

3https://github.com/huggingface (accessed on 31 March 2025)

References

1. Jourdan L, Boudin F, Dufour R, Hernandez N. Text revision in scientific writing assistance: an overview. In: Org CW, editor. 13th International Workshop on Bibliometric-enhanced Information Retrieval (BIR 2023). Vol. 3617 of CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Dublin (IEIreland; 2023. p. 22–36. [Google Scholar]

2. Benites F, Delorme Benites A, Anson CM. Automated text generation and summarization for academic writing. In: Digital writing technologies in higher education. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 279–301. [Google Scholar]

3. Ibrahim Altmami N, El Bachir Menai M. Automatic summarization of scientific articles: a survey. J King Saud Univ-Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(4):1011–28. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.04.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gonçalves S, Cortez P, Moro S. A deep learning classifier for sentence classification in biomedical and computer science abstracts. Neural Comput Appl. 2020;32(11):6793–807. doi:10.1007/s00521-019-04334-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yu W, Zhu C, Li Z, Hu Z, Wang Q, Ji H, et al. A survey of knowledge-enhanced text generation. ACM Comput Surv. 2022 Nov;54(11s):1–38. doi:10.1145/3512467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Han Z, Chen F, Zhang H, Yang Z, Liu W, Shen Z, et al. An attention-based representation learning model for multiple relational knowledge graph. Expert Syst. 2023;40(6):e13234. doi:10.1111/exsy.13234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ke P, Ji H, Ran Y, Cui X, Wang L, Song L, et al. JointGT: graph-text joint representation learning for text generation from knowledge graphs. In: Zong C, Xia F, Li W, Navigli R, editors. Findings of the association for computational linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 2526–38. [Google Scholar]

8. Chen W, Su Y, Yan X, Wang WY. KGPT: knowledge-grounded pre-training for data-to-text generation. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2020; Online: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 8635–48. [Google Scholar]

9. Colas A, Alvandipour M, Wang DZ. GAP: a graph-aware language model framework for knowledge graph-to-text generation. In: Calzolari N, Huang CR, Kim H, Pustejovsky J, Wanner L, Choi KS et al., editors. Proceedings of the 29th international conference on computational linguistics. Gyeongju, Republic of Korea: International Committee on Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 5755–69. [Google Scholar]

10. Yang Z, Einolghozati A, Inan H, Diedrick K, Fan A, Donmez P, et al. Improving text-to-text pre-trained models for the graph-to-text task. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Natural Language Generation from the Semantic Web (WebNLG+); 2020; Dublin, Ireland (VirtualAssociation for Computational Linguistics. p. 107–16. [Google Scholar]

11. Ribeiro LFR, Schmitt M, Schütze H, Gurevych I. Investigating pretrained language models for graph-to-text generation. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Conversational AI; 2021; Online: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 211–27. [Google Scholar]

12. Kale M, Rastogi A. Text-to-text pre-training for data-to-text tasks. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Natural Language Generation; 2020; Dublin, Ireland: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 97–102. [Google Scholar]

13. Li Y, Chen CLP, Zhang T. A survey on siamese network: methodologies, applications, and opportunities. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2022;3(6):994–1014. doi:10.1109/TAI.2022.3207112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lewis M, Liu Y, Goyal N, Ghazvininejad M, Mohamed A, Levy O, et al. BART: denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. In: Jurafsky D, Chai J, Schluter N, Tetreault J, editors. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 7871–80. [Google Scholar]

15. Raffel C, Shazeer N, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2020;21(140):1–67. [Google Scholar]

16. Chung HW, Hou L, Longpre S, Zoph B, Tay Y, Fedus W, et al. Scaling instruction-finetuned language models. J Mach Learn Res. 2024;25(70):1–53. [Google Scholar]

17. Gupta S, Gupta SK. Abstractive summarization: an overview of the state of the art. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;121(17):49–65. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2018.12.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ito T, Kuribayashi T, Kobayashi H, Brassard A, Hagiwara M, Suzuki J, et al. Diamonds in the rough: generating fluent sentences from early-stage drafts for academic writing assistance. In: Van Deemter K, Lin C, Takamura H, editors. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Natural Language Generation. Tokyo, Japan: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 40–53. [Google Scholar]

19. Wang Q, Huang L, Jiang Z, Knight K, Ji H, Bansal M, et al. PaperRobot: incremental draft generation of scientific ideas. In: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019; Florence, Italy: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 1980–91. [Google Scholar]

20. Ji S, Pan S, Cambria E, Marttinen P, Yu PS. A survey on knowledge graphs: representation, acquisition, and applications. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;33(2):494–514. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3070843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Koncel-Kedziorski R, Bekal D, Luan Y, Lapata M, Hajishirzi H. Text generation from knowledge graphs with graph transformers. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); 2019; Minneapolis, Minnesota: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 2284–93. [Google Scholar]

22. Luan Y, He L, Ostendorf M, Hajishirzi H. Multi-task identification of entities, relations, and coreference for scientific knowledge graph construction. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2018; Brussels, Belgium: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 3219–32. [Google Scholar]

23. Zhong Z, Chen D. A frustratingly easy approach for entity and relation extraction. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2021; Online: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

24. Nouri N. Text style transfer via optimal transport. In: Carpuat M, de Marneffe MC, Ruiz Meza IV, editors. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Seattle, WA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 2532–41. [Google Scholar]

25. Suzgun M, Melas-Kyriazi L, Jurafsky D. Prompt-and-rerank: a method for zero-shot and few-shot arbitrary textual style transfer with small language models. In: Goldberg Y, Kozareva Z, Zhang Y, editors. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 2195–222. [Google Scholar]

26. Elekes Á., Englhardt A, Schäler M, Böhm K. Toward meaningful notions of similarity in NLP embedding models. Int J Digit Libr. 2018;21(2):109–28. doi:10.1007/s00799-018-0237-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zeng K, Li C, Hou L, Li J, Feng L. A comprehensive survey of entity alignment for knowledge graphs. AI Open. 2021;2(6):1–13. doi:10.1016/j.aiopen.2021.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kang D, Hovy E. Plan ahead: self-supervised text planning for paragraph completion task. In: Webber B, Cohn T, He Y, Liu Y, editors. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 6533–43. [Google Scholar]

29. Schopf T, Arabi K, Matthes F. Exploring the landscape of natural language processing research. In: Mitkov R, Angelova G, editors. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing. Varna, Bulgaria: INCOMA Ltd.; 2023. p. 1034–45. [Google Scholar]

30. Schmitt M, Ribeiro LFR, Dufter P, Gurevych I, Schütze H. Modeling graph structure via relative position for text generation from knowledge graphs. In: Proceedings of the Fifteenth Workshop on Graph-Based Methods for Natural Language Processing (TextGraphs-15); 2021; Mexico City, Mexico: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

31. Yuan S, Faerber M. Evaluating generative models for graph-to-text generation. In: Mitkov R, Angelova G, editors. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing. Varna, Bulgaria: INCOMA Ltd.; 2023. p. 1256–64. [Google Scholar]

32. Papineni K, Roukos S, Ward T, Zhu WJ. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In: Isabelle P, Charniak E, Lin D, editors. Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2002. p. 311–8. [Google Scholar]

33. Banerjee S, Lavie A. METEOR: an automatic metric for mt evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments. In: Goldstein J, Lavie A, Lin CY, Voss C, editors. Proceedings of the ACL Workshop on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evaluation Measures for Machine Translation and/or Summarization. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2005. p. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

34. Popović M. chrF: character n-gram F-score for automatic MT evaluation. In: Bojar O, Chatterjee R, Federmann C, Haddow B, Hokamp C, Huck M et al., editors. Proceedings of the Tenth Workshop on Statistical Machine Translation. Lisbon, Portugal: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2015. p. 392–5. [Google Scholar]

35. Lin CY. ROUGE: a package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In: Text Summarization Branches Out. Barcelona, Spain: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2004. p. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

36. Zhang T, Kishore V, Wu F, Weinberger KQ, Artzi Y. BERTScore: evaluating text generation with BERT. In: 8th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2020; April 26–30, 2020; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2020. p. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

37. Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: sentence embeddings using siamese BERT-networks. In: Inui K, Jiang J, Ng V, Wan X, editors. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). Hong Kong, China: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 3982–92. [Google Scholar]

38. Wang H, Lepage Y, Goh CL. Typicality of lexical bundles in different sections of scientific articles. In: Proceedings of the 2020 2nd Symposium on Signal Processing Systems, SSPS ’20; 2020; New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 56–60. [Google Scholar]

39. Wang J, Wang W, Meng F, Zhou L, Guo S. A review of knowledge reasoning based on neural network. In: 2023 IEEE 12th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT); 2023; Bhopal, India. p. 580–4. [Google Scholar]

40. Rezayi S, Zhao H, Kim S, Rossi R, Lipka N, Li S, et al. Enriching knowledge graph embeddings with external text. In: Toutanova K, Rumshisky A, Zettlemoyer L, Hakkani-Tur D, Beltagy I, Bethard S, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 2767–76. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools