Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A NAS-Based Risk Prediction Model and Interpretable System for Amyloidosis

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110003, China

2 Neusoft Research, Neusoft Group Ltd., Shenyang, 110179, China

* Corresponding Author: Yingyou Wen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Neural Architecture Search: Optimization, Efficiency and Application)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 5561-5574. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.063676

Received 21 January 2025; Accepted 24 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

Primary light chain amyloidosis is a rare hematologic disease with multi-organ involvement. Nearly one-third of patients with amyloidosis experience five or more consultations before diagnosis, which may lead to a poor prognosis due to delayed diagnosis. Early risk prediction based on artificial intelligence is valuable for clinical diagnosis and treatment of amyloidosis. For this disease, we propose an Evolutionary Neural Architecture Searching (ENAS) based risk prediction model, which achieves high-precision early risk prediction using physical examination data as a reference factor. To further enhance the value of clinic application, we designed a natural language-based interpretable system around the NAS-assisted risk prediction model for amyloidosis, which utilizes a large language model and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to achieve further interpretation of the predicted conclusions. We also propose a document-based global semantic slicing approach in RAG to achieve more accurate slicing and improve the professionalism of the generated interpretations. Tests and implementation show that the proposed risk prediction model can be effectively used for early screening of amyloidosis and that the interpretation method based on the large language model and RAG can effectively provide professional interpretation of predicted results, which provides an effective method and means for the clinical applications of AI.Keywords

With the rapid development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology, its application in healthcare has become increasingly promising, and various Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) [1–3] techniques have been widely used in different healthcare fields, especially DL-based methods provide higher quality performance for various healthcare tasks including medical image reconstruction, electronic health record management, cancer diagnosis [4,5], disease prediction, medical image analysis [6], image retrieval, and computational biology [7–10]. DL models have a complex network structure consisting of multiple layers of neurons connected by nonlinear activation functions. Complex DL models are more accurate than traditional ML. However, typical DL such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) may suffer from vanishing gradient and saturation accuracy owing to the increase in depth.

Neural Architecture Search (NAS) attempts to detect effective model architectures without human intervention. Moreover, Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) for NAS can find better solutions than human-designed architectures by exploring a large search space for possible architectures and apply to different search spaces for NAS [11,12]. NAS has surpassed hand-designed architectures on some difficult tasks, particularly in the medical field [13], it can efficiently and automatically complete analytical tasks in electronic health records (EHRs), including disease prediction and classification, data enhancement, privacy protection, and clinical event prediction [14]. NAS combined with CNN can help medical practitioners make more accurate and efficient medical diagnoses while minimizing human intervention [15].

Therefore, the use of evolutionary NAS [16–19] in healthcare applications is necessary. Firstly, healthcare datasets are often massive and complex, making it challenging to extract relevant information and insights using traditional ML approaches. Secondly, evolutionary NAS can adapt to meet the multiple requirements of a given task. By automating the design process, NAS can help reduce the time and cost required to develop new AI solutions in healthcare, while also improving their performance and reducing the risk of human error [20–22]. Moreover, NAS can automatically predict and classify diseases, to assist physicians in making personalized diagnoses and treatment [23–25].

Primary Light Chain Amyloidosis is a rare hematological disease caused by the deposition of amyloid proteins (proteins abnormally folded to form fibrillar-like structures containing β-folded sheets) in the extracellular matrix, resulting in damage to the tissues and organs at the site of deposition, which can involve a variety of organs and tissues, such as the kidneys, the heart, the gastrointestinal tract, the liver, the spleen, the nervous tissues, the soft tissues, the thyroid, the adrenals, etc. Among them, lymph node involvement accounts for 20%–33% and heart involvement accounts for 32%–45%. As amyloidosis is a rare disease associated with high mortality and difficult early diagnosis, nearly one-third of patients with amyloidosis experience five or more consultations before diagnosis, which may lead to a poor prognosis due to delayed diagnosis, with up to 30% of patients with AL amyloidosis dying within the first year of diagnosis.

Amyloidosis is a rare hematological disease with no typical case. Its early onset symptoms are very similar to those of common diseases such as heart disease, kidney disease, and lung disease, and it is often misdiagnosed as heart failure, diabetes mellitus, over-exercise, respiratory disease, allergies, etc. Therefore, it is very difficult to make predictions using a variety of routine clinical data and hand-designed deep-learning networks. Generally, the predicted results of AI models for amyloidosis cannot be effectively differentiated from various common diseases and are difficult to use in the clinic. As a result, research in this area has progressed slowly. On the other hand, an AI-based risk prediction model must provide a sufficient diagnostic basis from a professional perspective to be truly accepted by physicians. Therefore, the interpretability of the AI model is also a practical requirement that must be considered in the implementation of the risk prediction system.

Aiming at the problems of risk prediction for amyloidosis and providing explainable assistant diagnosis, this paper proposes a NAS-assisted risk prediction model for amyloidosis, and around this model, we use Large Language Model (LLM) and RAG to provide professional interpretations in natural language, which can in turn realize accurate early warning and assistant diagnosis of amyloidosis.

2 NAS-Assisted Risk Prediction Model for Amyloidosis

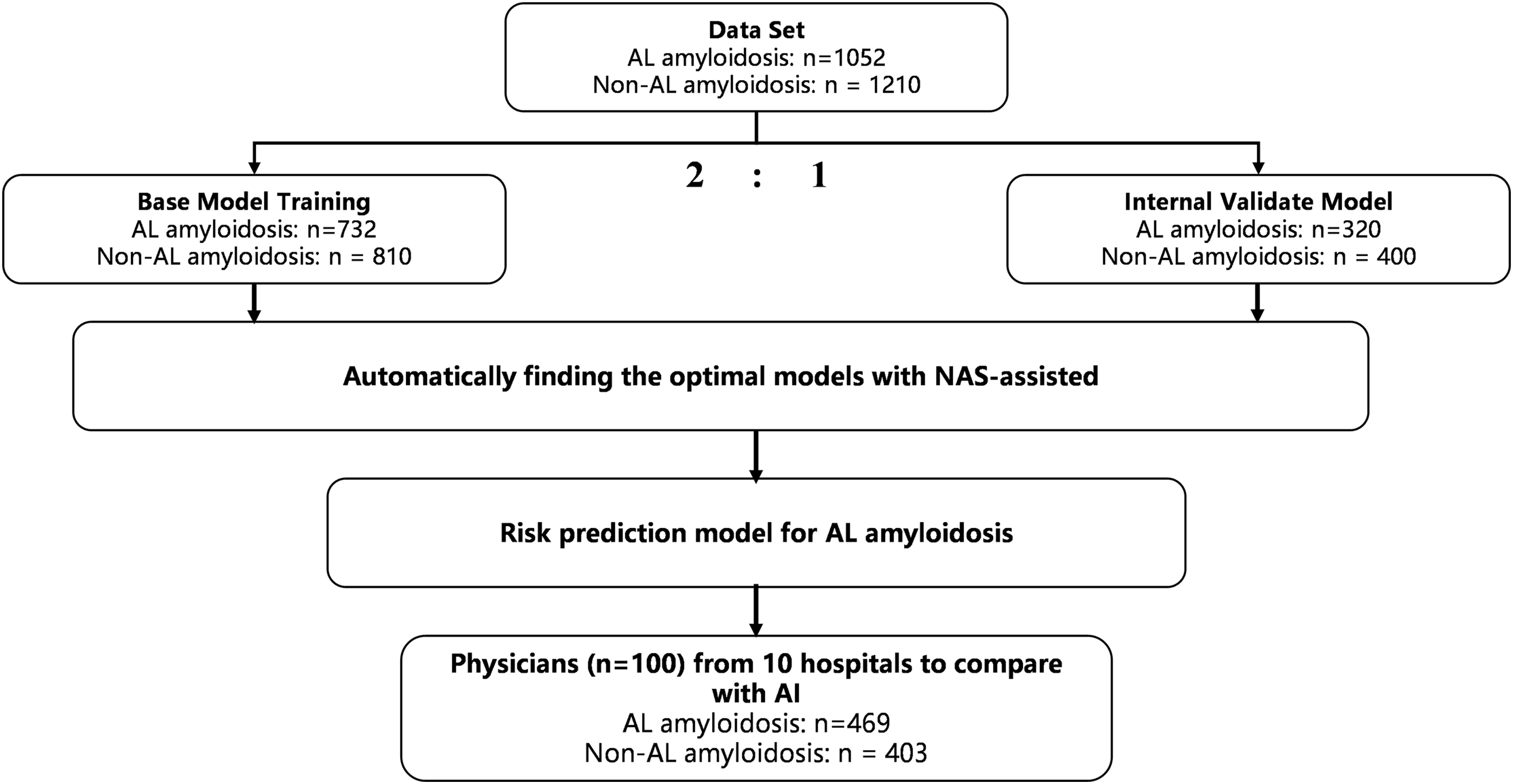

The prediction for amyloidosis aims to achieve highly accurate results by exploiting routine screening indicators. To tackle this issue, we propose a NAS-assisted framework aiming at automatically finding the optimal model to enhance the accuracy of predictions. The training and validation process of the risk prediction model for amyloidosis is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The training and validation process of the model

A total of 1355 diagnosed cases were collected from 18 medical institutions participating in this study, of which 302 cases were removed due to too many missing values. We constructed training and validation datasets using data from 1052 diagnosed and 1210 non-amyloidosis patients. In addition, in order to test the generalization ability of the model, we collected 469 amyloidosis cases from 10 hospitals that did not participate in the study, which constituted an external dataset for testing. All datasets were de-privatized and ethically checked.

As to the NAS-assisted framework, we first sample architectures from the designed search space to initiate the population (P). Then, we compute the constraint

2.1 Problem Formulation of a Risk Prediction Model for Amyloidosis

We consider the design of a risk prediction model for amyloidosis as an optimization problem, aiming to improve the accuracy of prediction with smaller parameter sizes. It can be expressed as Eq. (1).

where p

where

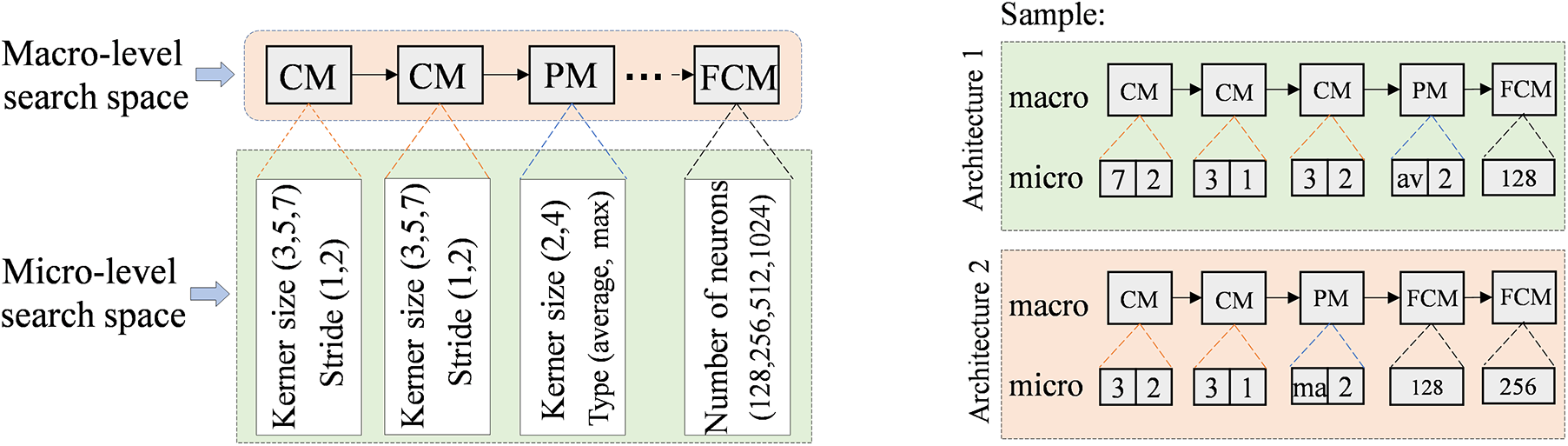

We adopt a macro-level and micro-level search space devoted to the risk prediction of amyloidosis as shown in Fig. 2 (left). At the macro-level, we built the backbone architecture of the medical model via Convolutional Module (CM), Pooling Module (PM), and Fully Connected Module (FCM), where multiple CM, PM, and FCM modules are stacked to form a deep-level feature extraction network. The combination of these modules not only captures local features but also effectively extracts high-level semantic information that is closely related to amyloidosis risk. In this way, we ensure the medical model can extract multi-scale features at different layers, thus enhancing the accuracy of risk prediction.

Figure 2: Search space of AI model for amyloidosis

At the micro-level, we pay attention to the effects of convolution kernel size and pooling operation on feature extraction. Through systematic tuning and optimization of the parameters in the micro-level search space, the medical model can enhance the model’s sensitivity to the risk of amyloidosis while maintaining computational efficiency. In Fig. 2 (right), we display the network architecture consisting of macro- and micro-level search space sampling components through two examples. The macro-level backbone of Architecture 1 consists of CM, PM, and FCM stacked in sequence, with the structure CM-CM-CM-PM-FCM; the micro-level parameters are configured as (7, 2) for a convolutional kernel size of 7 × 7 with a step size of 2; (3, 1) for a convolutional kernel size of 3 × 3 with a step size of 1; (3, 2) for a convolutional kernel size of 3 × 3 with a step size of 2; (Average) for the pooling layer to use the average pooling operation; and (128) for the number of neurons of the fully connected layer to be 128; i.e., the micro-level parameters are configured as (7, 2)-(3, 1)-(3, 2)-(Average,2)-(128).

For the Architecture 2, the macro-level backbone is CM-CM-PM-FCM-FCM, the micro-level parameters are configured as (3, 2)-(3, 1)-(Max,2)-(128)-(256).

For initializing the population, we first randomly chose three positive integers to represent the number of CMs, PMs, and FCMs in the backbone network (i.e., population individuals). For example, suppose the randomly generated values are CM = 3, PM = 1, and FCM = 1, then the macro-level structure of this backbone network is CM-CM-CM-PM-FCM. Next, we sampled the corresponding parameter

2.4 Quality Evaluation of Evolutionary Populations

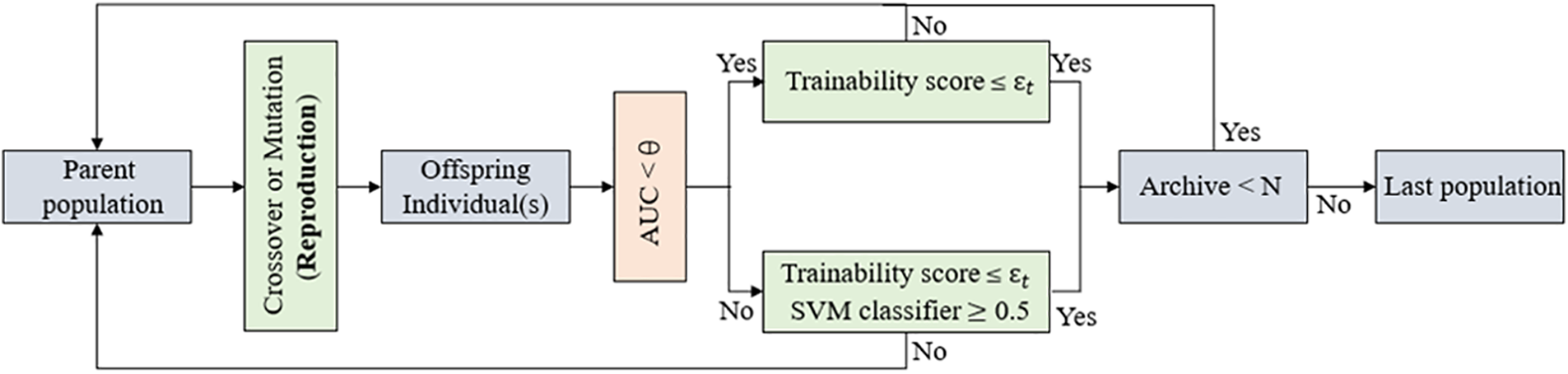

In ENAS, the better-performance architectures may be impacted by the poorer ones during the evolutionary process, leading to a gradual decrease in the probability that the better-performance architectures will generate offspring. To address this problem, we train a classifier to discriminate between good and bad architectures in the population to boost the probability that a high-performing architecture performs cross-mutations, thus enhancing the chances of generating high-quality offspring. Specifically, we first sort the individuals in the population in descending order based on the shift-based density estimation [29,30]; then, the top K architectures of the sort are selected to represent the positive samples with potential architectures, while the remaining architectures are considered as the negative samples with poor performance. Next, we train a support vector machine classifier by exploiting these positive and negative samples for efficiently distinguishing potential architectures and non-potential architectures. Subsequently, we evaluate the probability that the support vector machine correctly classifies the architectures through the AUC to provide auxiliary support for environment selection.

Before using support vector machine classifiers to assist environment selection, we generate offspring through crossover and mutation operators. For the crossover operator, we randomly select two parent individuals in the population and exchange some of the components of their macro-level modules, as well as exchange the corresponding macro-level parameter configurations. For the mutation operators, we divide into two types: macro-level mutation and micro-level mutation. In macro-level mutation, we perform mutation by replacing one module with another, e.g., replacing a pooling module (PM) with a convolutional module (CM). In micro-level mutation, we change the parameter settings within a module for mutation, e.g., replacing a 3 × 3 convolution kernel in a CM with a 7 × 7 convolution kernel.

As shown in Fig. 3, when performing environmental selection with the assistance of the support vector machine classifier, we design a strategy to ensure the quality of the offspring population. Specifically, we first generate offspring individuals through crossover and mutation operators; then, the current offspring are evaluated using the support vector machine classifier and the AUC score is used to determine the classifier’s reliability for the current classification (when AUC < θ, it indicates that the classifier is unreliable). If the classifier is unreliable and the trainability score

Figure 3: Environmental selection

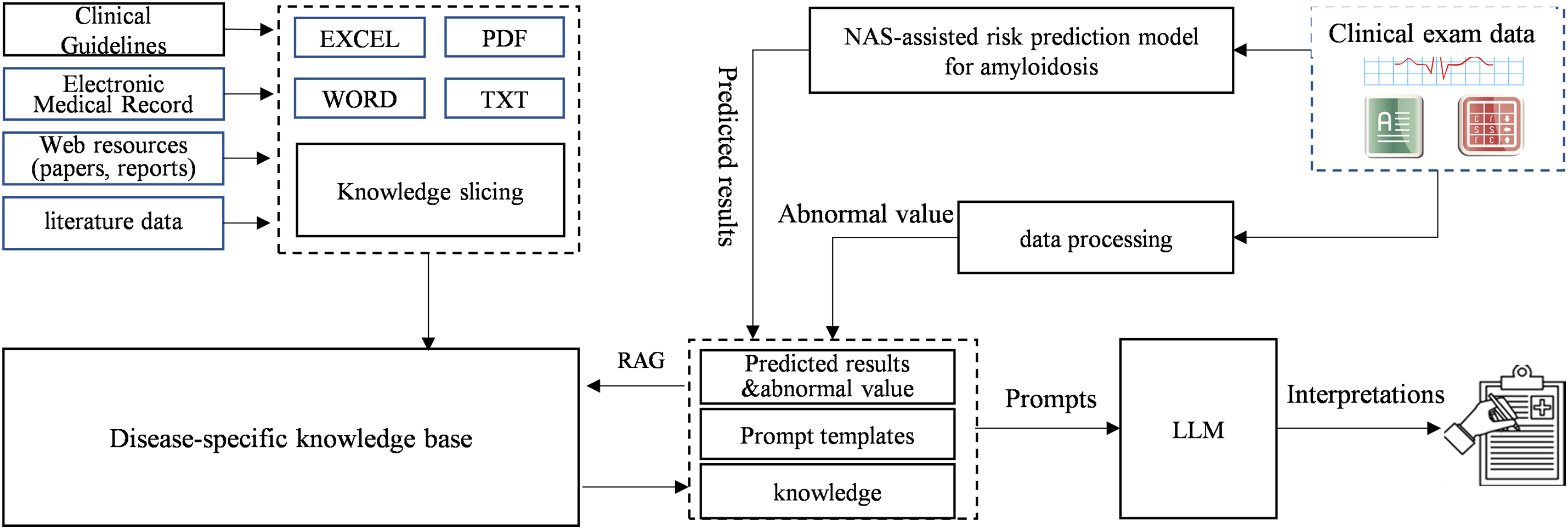

3 Risk Prediction System with Interpretability

The use of the NAS-assisted risk prediction model for amyloidosis yields accurate predictions. However, the high accuracy of the AI model does not mean the model is acceptable and usable by clinicians. For this reason, we constructed a risk prediction system with interpretability, as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Risk prediction system for amyloidosis

The basic objective of the system is to provide professional interpretations of small model using LLM and knowledge engineering. This professional interpretation is centered around the NAS-assisted risk prediction model’s result to find the clinical diagnostic basis related to the patient’s symptoms in clinical guidelines, electronic cases, literature data, etc. and then the RAG method and prompt engineering is used to generate an interpretation of the results in natural language to be output to the clinician through the LLM.

The system consists of the following components: NAS-assisted risk prediction model, large language model, clinical disease knowledge base, and interpretation generation module. The NAS-assisted risk prediction model (small model) generates the predicted probability of a case’s risk of developing amyloidosis based on the input of complex clinical indicators. The large language model uses RAG to retrieve the clinical diagnostic basis and knowledge for each clinical indicator, especially for those abnormal clinical indicators, which indicate possible disease factors in the patient and are important references for clinical diagnosis. These abnormalities have been clinically validated before use. The clinical knowledge base supports RAG implementation by slicing various documents and knowledge sources and providing a retrieval interface. The interpretation generation module summarizes the retrieved case-related knowledge and clinical guidelines, inputs them into the LLM using prompt engineering, and ultimately generates professional interpretations of the risk prediction result.

In this system, RAG is the key to enabling the generation of professional interpretations for prediction results. RAG is a unified solution paradigm currently being used to assist in solving knowledge problems of LLM such as illusions, factual errors in knowledge, outdated knowledge, etc., and is currently able to be modularly decomposed into multiple steps such as retrieval, reordering, reasoning, etc. The knowledge used throughout its lifecycle comes from external resources in multiple formats such as databases, documents, etc., which are organized in the form of text blocks. Therefore, this process requires extracting documents into strings and slicing them into text blocks as the first processing step. However, existing RAG optimization frameworks usually ignore the importance of this phase and directly use rule-based or semantic similarity-based slicing, which limits the accuracy of slicing and further affects the overall performance of RAG. For this reason, around the realization of the risk prediction system for amyloidosis, we propose a document-based global semantic slicing approach to achieve a more accurate slicing of the document, to ensure the semantic integrity of the sliced text block, and to avoid the impact of missing important information or incomplete reasoning logic on the professional interpretation.

3.1 Knowledge Slicing and Retrieval for Amyloidosis Based on Document Global Semantics

In slicing, our approach aims to achieve lossless slicing of amyloidosis-related knowledge documents without losing the semantic integrity of the original document and without introducing additional error messages. In this regard, we expect to utilize the association relations at the document token level to mine the link weaknesses within the document sentences, and these weak association relations can be considered as a natural manifestation of phenomena such as semantic transitions and semantic breaks. The pre-trained language model learns the global semantic information of the text through a large amount of pre-training data in the training stages, and has a strong natural language understanding capability. Therefore, the document representation and attention weights generated by the model in document encoding can be considered as a reflection of the global semantics of the document. To make full use of this global semantic information, we propose a method to construct a slice evaluator based on the text encoding model, which is capable of accurately identifying the correct slice position in a document by exploiting the potential semantic relevance of chunking in the document’s attentional representation.

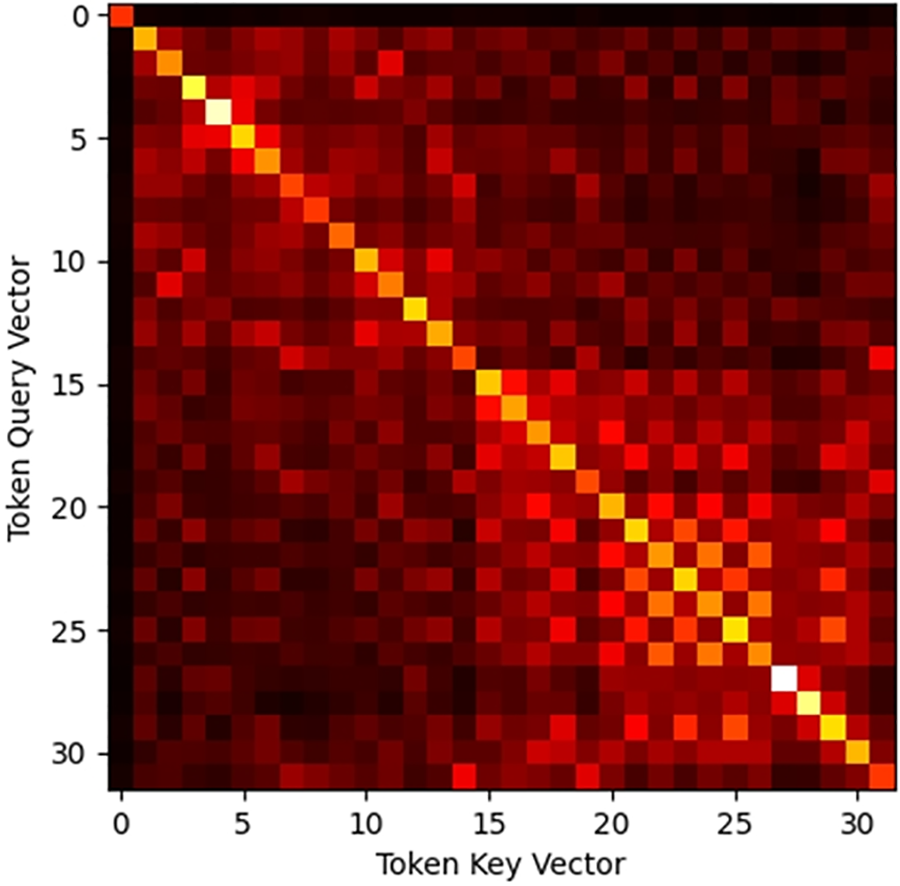

By visualizing the QKV matrices of the language model, we can observe significant correlation differences between the tokens of relevant and irrelevant sentences in these matrices, which indicates the potential cut-off position of the document. To do this, we try to treat the attention matrix as image information and extract the global semantic information of a document through feature extraction methods in image processing. Specifically, for a document, to ensure the completeness of sentences, we use sentences rather than tokens as the minimum granularity for cuts. We first slice the document into independent sentences using the clause model and construct the mapping relationship between tokens and sentences using the tokenizer of BGE-M3. Subsequently, we feed the documents into BGE-M3 to obtain the Q, and K matrices generated by multiple attention heads at different layers within its network. These matrices are pooled evenly according to the mapping relationships to construct a global association graph of the document at the sentence level as shown in Fig. 5. The two axes of the graph represent the sentences in the document, and each node in the graph represents the closeness of the association between two sentences, with a brighter color indicating a higher degree of association.

Figure 5: Attention correlation diagram

To capture the semantic information of the document at the global level, we take the local part of the global association relation graph as the image input each time, each pixel value in the graph as an element value, and the outputs of the different layers of the encoding model and the attention header as multiple channels of the image. The model uses a convolutional neural network architecture that performs a convolutional operation on each input association graph to extract a feature representation of the image, and the feature representation is passed through a fully connected layer to output the probability that the current document part belongs to the same text block in a regression manner.

In the training phase, we take the existing amyloidosis knowledge text dataset as the basis and consider each chunk in the original dataset as a correct text chunk that does not need to be sliced again, and the splicing of multiple chunks as a complete document sample. Each full document sample is fed into BGE-M3 to construct an association relation graph, and we construct the training dataset using the part of the images in the association relation graph belonging to the sentences in the same chunk as positive samples, and the part of the images randomly selected and containing sentences across chunks as negative samples. We constructed a model containing four CNN layers and two fully connected layers and completed the training of the model using binary cross entropy as the loss function.

3.2 Quality Control of Interpretation

The problem of hallucinations in large language models is a great challenge for medical AI applications. RAG can improve the professionalism of LLM and thus reduce the probability of hallucinations to some extent. Therefore, we designed a quality control scheme with the main purpose of reducing hallucinations and improving professionalism. We achieved supplementation of amyloidosis specialized knowledge through the RAG and wanted the output of the LLM to cover all the specialized knowledge provided by the RAG. For this purpose, we used a methodology based on fact-checking. We use the same slicing model described above to segment the output text and calculate the similarity between it and the retrieved knowledge to discriminate whether the output matches the specialized knowledge. Each interpretation is generated several times, each time using a different prompt. The output with the highest similarity is ultimately selected as the final interpretation.

To validate the NAS-assisted risk prediction for amyloidosis and the interpretable system proposed in this paper, we established a validation environment, including a server configured with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8260 CPU and 1 TB of RAM, with an operating system of Ubuntu 20.04 LTS. The system was developed in Python, using a MySQL relational database, a Milvus vector database, and a Neo4j graph database for storing and managing multiple data types. For the large language model, the Qwen2-72B model was selected for local deployment on 2 × 32 GB A V100 Tensor Core GPUs.

4.1 Risk Prediction for Amyloidosis

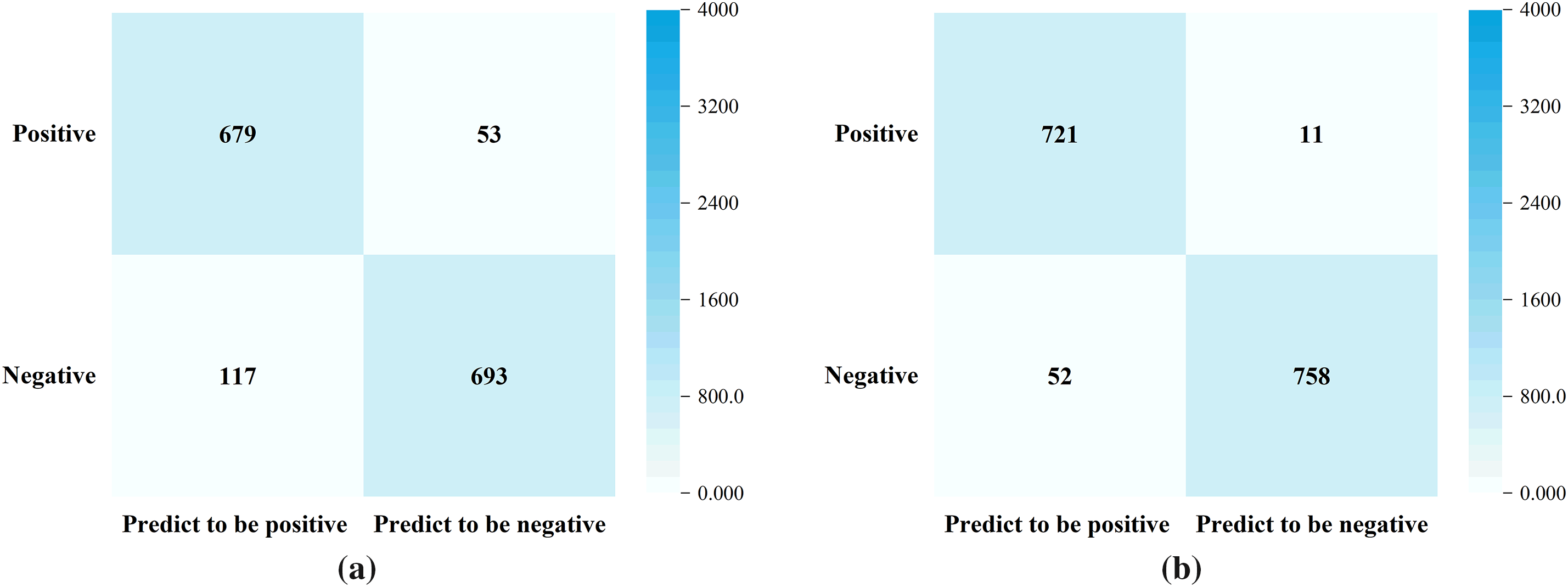

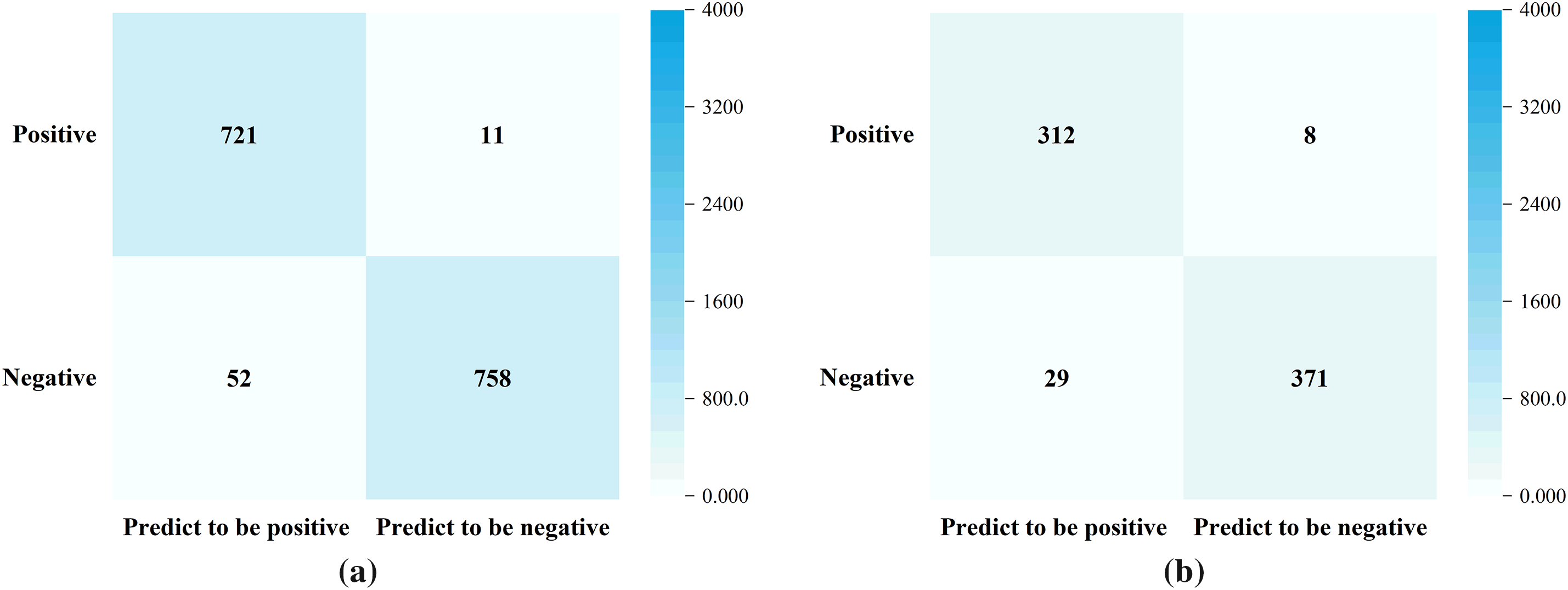

NAS-assisted risk prediction model for amyloidosis was trained on a real internal dataset. This internal dataset includes data from 1052 amyloidosis patients after de-privatization. All these samples have been diagnosed with amyloidosis based on tissue biopsy of amyloid deposits formed by immunoglobulin light chains. At the same time, another 1210 samples were randomly selected from nephrology, cardiology, gastroenterology, respiratory, rheumatology, and immunology, as well as healthy individuals respectively. We divided the internal dataset into two parts, one for model training and one for model validation. The training dataset includes sample data from 732 amyloidosis patients and 810 non-AL amyloidosis patients; the validation dataset includes sample data from 320 amyloidosis patients and 400 non-AL amyloidosis patients. The accuracy of the model on the training dataset is shown in Fig. 6. The accuracy of the base model without NAS-assisted and with NAS-assisted on the training dataset is 90.26% and 95.91%, respectively.

Figure 6: The performance of the model on the training dataset. (a) without NAS-assisted (Accuracy = 90.26%); (b) NAS-assisted (Accuracy = 95.91%)

The comparison of the NAS-assisted risk prediction model on training dataset and validation dataset is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Performance evaluation of NAS-assisted risk prediction model. (a) Training dataset (Accuracy = 95.91%); (b) Validation dataset (Accuracy = 94.86%)

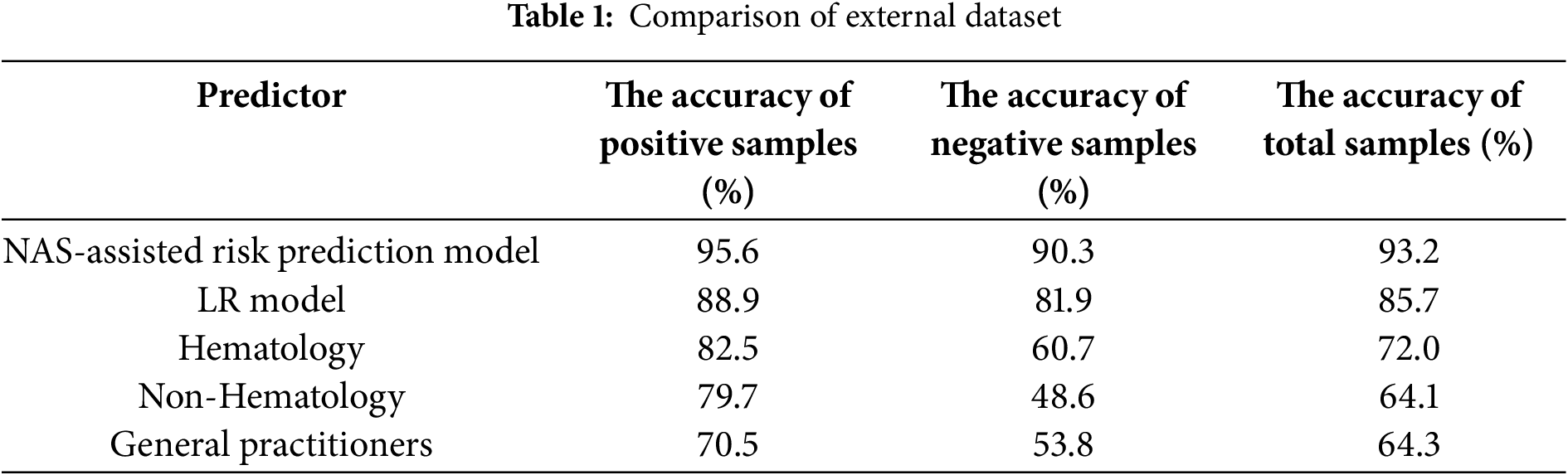

Meanwhile, to evaluate the performance of the NAS-assisted risk prediction model for amyloidosis involved in this paper, we introduced physicians as a control group and also constructed an LR model as a reference. One hundred physicians from 10 hospitals were invited to give diagnostic judgments, including 40 hematologists, 40 non-hematologists and 20 general practitioners. We evaluate the performance of the model on the external dataset, which is provided by the external hospital and includes 469 amyloidosis patients and 403 non-amyloidosis patients from 10 hospitals that did not participate in the study. The test results are shown in Table 1.

4.2 Professionalism Assessment of Interpretation

To enhance the accuracy of document slicing and knowledge extraction in RAG, we adopted a document-based global semantic slicing approach to achieve a more accurate slicing of the document during system implementation to ensure the semantic integrity of the sliced text block, and to avoid the impact of missing important information or incomplete reasoning logic. By doing this, we want the output of LLM to cover all the specialized knowledge, so we record the similarity of the output to the knowledge retrieved and evaluate the knowledge usage, as well as the acceptance rate of physicians.

We tested the prediction results on 100 sets of samples. For the predicted result of each set of samples, five interpretations of the result were generated. By comparing the knowledge similarity of the content of each interpretation, the best one was selected and provided to physicians for quality assessment, and then the acceptance rate of physicians was counted.

Knowledge similarity is calculated as follows. First, we slice the interpretation into independent sets of slices a ∈ A using the same trained slicing model and perform a vectorization operation. Then calculate the similarity between a ∈ A and the vectorized knowledge set b ∈ B retrieved by RAG to discriminate whether the output content fits into the specialized knowledge or not. Cosine similarity was used in Eq. (3):

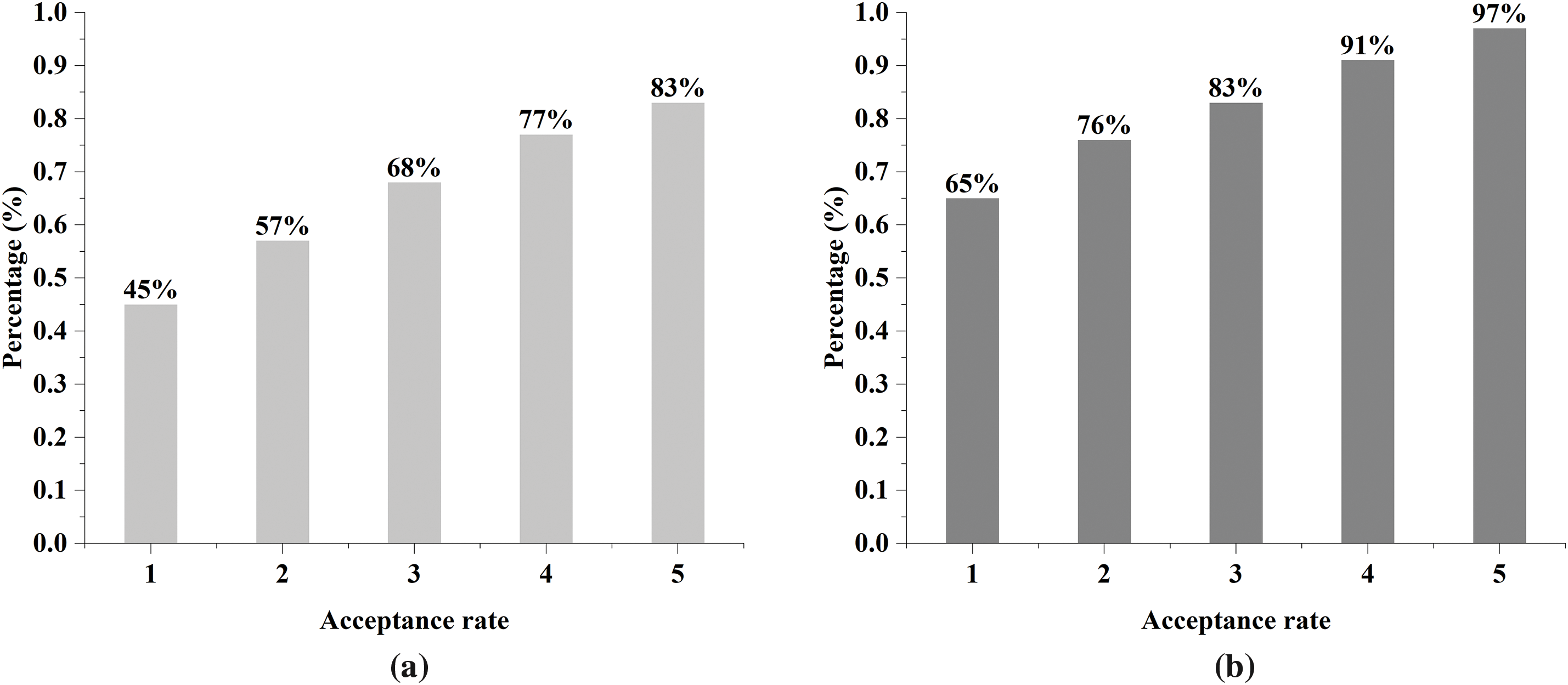

In the test of acceptance rate, we set the knowledge similarity threshold to 90%, and the results are shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Acceptance rate of interpretations by physicians. (a) Without document-based global semantic slicing; (b) With document-based global semantic slicing

This suggests that physicians’ acknowledgment of the interpretation significantly improved by introducing of document-based global semantic slicing method, which is attributed to the fact that by improving the quality of semantic slicing, it can provide the LLM with more accurate knowledge complement related to amyloidosis, which, in turn, significantly improves the physician’s acceptance rate.

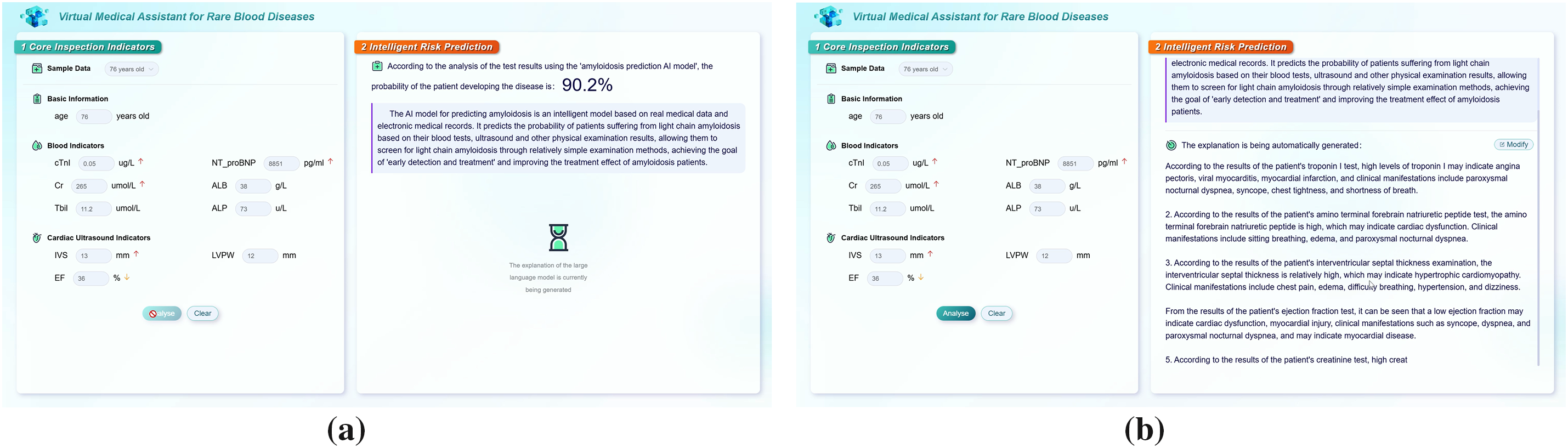

The implementation of the system contains three parts of work: a NAS-assisted risk prediction model, an RAG framework, and an interpretable assistant diagnosis system, and the specific implementation of the system is shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: System implementation. (a) Risk prediction; (b) Interpretation

The system first performs knowledge extraction and forms a knowledge base for amyloidosis-specific diseases through document slicing. Then the probability of developing amyloidosis is assessed using risk prediction models according to the clinical indicators for a specific clinical case, while relevant diagnostic and treatment knowledge is retrieved using RAG. Finally, the prompt template is used to generate prompts and the LLM is used to generate a professional interpretation of the predicted result for the case, providing clinical assistance to hematologists.

In this paper, we propose a risk prediction model for amyloidosis by using evolutionary neural architecture searching, defining the search space, and designing an assessment method of evolutionary population quality. To further enhance the clinical application value of the model, we designed a natural language-based interpretable system around the NAS-assisted risk prediction model for amyloidosis, utilizing a large language model and RAG to achieve further interpretation and explanation of the prediction. Tests and application showed that the proposed risk prediction model can be effectively used for early screening of amyloidosis, and the proposed document-based global semantic slicing method in RAG can effectively provide professional interpretation of AI conclusions, which provides an effective method and means for the clinical applications of AI.

Although this paper adopts the evolutionary NAS to optimize the structure of the risk prediction model, and uses a large language model and an RAG to provide an interpretation of the predicted results, the work still needs to be further deepened, in particular, a more systematic framework needs to be considered to improve the accuracy and the professionalism of the interpretation.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by Liaoning Province Key R&D Program Project (Grant Nos. 2019JH2/10100027) and in part by Grants from Shenyang Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. RC210469).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Chen Wang and Yingyou Wen; methodology, Chen Wang and Yanyi Liu; software, Tiezheng Guo and Qingwen Yang; validation, Tiezheng Guo and Jiawei Tang; data curation, Jiawei Tang; writing—original draft preparation, Tiezheng Guo; writing—review and editing, Yingyou Wen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: This paper focuses on the construction of a NAS-based disease risk prediction model and an interpretable approach to the prediction model. The dataset used for the basic model construction in this paper comes from the de-privatized data provided by the relevant medical institutions. The medical institutions concerned, together with Northeastern University, where the authors of this paper are based, and Neusoft Group, have jointly undertaken the Liaoning Province Key R&D Program Project (Research on Key Technologies for Systems Engineering of Large Language Models; Grant No. 2019JH2/10100027) and Shenyang Science and Technology Plan Project (Intelligent Clinical Testing Technology Research Based on Big Data; Grant No. RC210469), and provides de-privatized data for medical AI technology research. This paper belongs to the research results of the above collaborative project and can use the de-privatized data involved in the project for research. This study does not involve any human or animal clinical trials.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Varghese J. Artificial intelligence in medicine: chances and challenges for wide clinical adoption. Visc Med. 2020;36(6):443–9. doi:10.1159/000511930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ghandi T, Pourreza H, Mahyar H. Deep learning approaches on image captioning: a review. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(3):1–39. doi:10.1145/3617592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Taylor J, Fenner J. The challenge of clinical adoption-the insurmountable obstacle that will stop machine learning? BJR Open. 2018;1(1):20180017. doi:10.1259/bjro.20180017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Morera-Ocon FJ. Early detection of pancreatic cancer. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12(17):2935–8. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v12.i17.2935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Ejiyi CJ, Qin Z, Agbesi VK, Yi D, Atwereboannah AA, Chikwendu IA, et al. Advancing cancer diagnosis and prognostication through deep learning mastery in breast, colon, and lung histopathology with ResoMergeNet. Comput Biol Med. 2025;185(14):109494. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ling Y, Wang Y, Dai W, Yu J, Liang P, Kong D. Multi-task attention network for automatic medical image segmentation and classification. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2023;43(2):674–85. doi:10.1109/TMI.2023.3317088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Chen R, Yang L, Goodison S, Sun Y. Deep-learning approach to identifying cancer subtypes using high-dimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(5):1476–83. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Litjens G, Kooi T, Bejnordi BE, Setio AA, Ciompi A, Ghafoorian F, et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 2017;42:60–88. doi:10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wang H, Jin Q, Li S, Liu S, Wang M, Song Z. A comprehensive survey on deep active learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 2024;95:103201. doi:10.1016/j.media.2024.103201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Xiao C, Choi E, Sun J. Opportunities and challenges in developing deep learning models using electronic health records data: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(10):1419–28. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocy068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Real E, Moore S, Selle A, Saxena S, Suematsu YL, Tan J, et al. Large-scale evolution of image classifiers. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2017 Aug 6–11; Sydney, NSW, Australia. p. 2902–11. [Google Scholar]

12. Pham H, Guan M, Zoph B, Le Q, Dean J. Efficient neural architecture search via parameters sharing. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2018 Jul 10–15; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 4095–104. [Google Scholar]

13. Lu Z, Whalen I, Dhebar Y, Deb K, Goodman ED, Banzhaf W, et al. Multiobjective evolutionary design of deep convolutional neural networks for image classification. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2020;25(2):277–91. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2020.3024708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Agneya DA, Shekar MS, Bharadwaj A, Vineeth N, Neelima ML. Deep learning in medical image analysis: a survey. In: 2024 International Conference on Innovation and Novelty in Engineering and Technology (INNOVA); 2024 Dec 20–21; Vijayapura, India. [Google Scholar]

15. Xu S, Quan H. Ect-nas: searching efficient cnn-transformers architecture for medical image segmentation. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); 2021 Dec 9–12; Houston, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

16. Ma L, Kang H, Yu G, Li Q, He Q. Single-domain generalized predictor for neural architecture search system. IEEE Trans Comput. 2024;73(5):1400–13. doi:10.1109/TC.2024.3365949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lu Z, Whalen I, Boddeti V, Dhebar Y, Deb K, Goodman E, et al. NSGA-Net: neural architecture search using multi-objective genetic algorithm. In: Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference; 2019 Jul 13–17; Prague, Czech Republic. p. 419–27. [Google Scholar]

18. Song SB, Nam JW, Kim JH. NAS-PPG: PPG-based heart rate estimation using neural architecture search. IEEE Sens J. 2021;21(13):14941–9. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2021.3073047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu X, Li J, Zhao J, Cao B, Yan R, Lyu Z. Evolutionary neural architecture search and its applications in healthcare. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;139(1):143–85. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.030391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pinos M, Mrazek V, Sekanina L. Evolutionary approximation and neural architecture search. Genet Program Evolvable Mach. 2022;23:351–74. doi:10.1007/s10710-022-09441-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Liu Y, Sun Y, Xue B, Zhang M, Yen GG, Tan KC. A survey on evolutionary neural architecture search. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;34(2):550–70. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3100554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Yan L, Zhang Z, Liang J, Qu B, Yu K, Wang K. ASMEvoNAS: adaptive segmented multi-objective evolutionary network architecture search. Appl Soft Comput. 2023;146(4):110639. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu X, Tian J, Duan P, Yu Q, Wang G, Wang Y. GrMoNAS: a granularity-based multi-objective NAS framework for efficient medical diagnosis. Comput Biol Med. 2024;171:108118. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Qin S, Zhang Z, Jiang Y, Cui S, Cheng S, Li Z. NG-NAS: node growth neural architecture search for 3D medical image segmentation. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2023;108:102268. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2023.102268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yu C, Wang Y, Tang C, Feng W, Lv J. EU-Net: automatic U-Net neural architecture search with differential evolutionary algorithm for medical image segmentation. Comput Biol Med. 2023;167:107579. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107579. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Z, Hensley C, Chen Z. Improving node classification with neural tangent kernel: a graph neural network approach. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Pattern Recognition and Automation Engineering (MLPRAE’24); 2024 Aug 7–9; Singapore. p. 93–7. [Google Scholar]

27. Wang L, Fan W, Li J, Ma Y, Li Q. Fast graph condensation with structure-based neural tangent kernel. In: Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference (WWW’24); 2024 May 13–17; Singapore. p. 4439–48. [Google Scholar]

28. Jacot A, Gabriel F, Hongler C. Neural tangent kernel: convergence and generalization in neural networks. In: Bengio S, Wallach H, Larochelle H, Grauman K, Cesa-Bianchi N, Garnett R, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems 31. Grand Isle: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

29. Li M, Yang S, Liu X. Shift-based density estimation for Pareto-based algorithms in many-objective optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2013;18(3):348–65. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2013.2262178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jiang S, Zou J, Yang S, Yao X. Evolutionary dynamic multi-objective optimisation: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(4):1–47. doi:10.1145/3524495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools