Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Intelligent Spatial Anomaly Activity Recognition Method Based on Ontology Matching

1 The Knowledge-intensive Software Engineering (NiSE) Research Group, Department of Artificial Intelligence, Ajou University, Suwon City, 16499, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Software and Computer Engineering, Ajou University, Suwon City, 16499, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Seok-Won Lee. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4447-4476. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.063691

Received 21 January 2025; Accepted 18 April 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

This research addresses the performance challenges of ontology-based context-aware and activity recognition techniques in complex environments and abnormal activities, and proposes an optimized ontology framework to improve recognition accuracy and computational efficiency. The method in this paper adopts the event sequence segmentation technique, combines location awareness with time interval reasoning, and improves human activity recognition through ontology reasoning. Compared with the existing methods, the framework performs better when dealing with uncertain data and complex scenes, and the experimental results show that its recognition accuracy is improved by 15.6% and processing time is reduced by 22.4%. In addition, it is found that with the increase of context complexity, the traditional ontology inference model has limitations in abnormal behavior recognition, especially in the case of high data redundancy, which tends to lead to a decrease in recognition accuracy. This study effectively mitigates this problem by optimizing the ontology matching algorithm and combining parallel computing and deep learning techniques to enhance the activity recognition capability in complex environments.Keywords

In the fast-developing Internet era, the widespread popularity of artificial intelligence, big data, Internet of Things (IoT), and sensing technologies have enabled more and more smart devices (e.g., Huawei smart wearables) to recognize human activities by sensing user behaviors (including location changes, environmental changes, and other peripheral information) [1]. The application of smart wearables with multiple sensors (e.g., smartphones) aims to provide more convenient and intelligent services to the public. However, current technologies still face many challenges in sensor data processing and anomalous activity recognition.

Currently, most context-aware applications rely on extracting features directly from sensor data and reasoning using traditional machine learning or rule-based approaches [2]. However, these approaches often have limitations when dealing with complex environments. For example, when sensor data is noisy or missing, the accuracy and robustness of the system will be significantly degraded. In addition, most existing activity recognition systems mainly target a single scene or a fixed pattern of activities, failing to fully consider diverse and complex contexts in the real world. With the expansion of application domains, the challenges of scalability and adaptability are becoming more and more prominent.

To address these challenges, various approaches have been proposed in academia and industry to enhance the performance of context-aware systems. For example, agent-based frameworks achieve context-awareness through sensor data fusion and knowledge exchange, but still face scalability issues in large-scale application scenarios. In addition, some studies have explored energy-efficient sensor architectures for automatic detection of human states and state transitions, which are effective in improving energy efficiency but still have difficulties in facing real-time spatial, temporal, and individual complexity scenarios [3].

As a high-level knowledge representation, ontology technology is gradually becoming an important tool for solving context-aware problems. Ontologies can significantly enhance the interoperability and integration of heterogeneous data by adding semantic annotations to the sensed data (e.g., temporal, spatial, and subject attributes). For example, the SOUA and CONON ontology frameworks can be used to model complex situations and behaviors [4]. However, most existing ontology models mainly describe daily activities and still have limited capability in recognizing abnormal activities, especially in complex and uncertain environments.

Ontology-driven context-aware approaches are not only applicable to smart homes, but also have important applications in areas such as healthcare and industrial IoT.

Smart Home: Abnormal activity detection is one of the important applications of smart home, and real-time monitoring can significantly improve user safety and convenience. For example, smart home systems can detect abnormal waking up at night, prolonged stationary behavior, etc., and remind family members or emergency contacts to take measures.

Healthcare: In the medical field, accurate activity recognition is crucial for health monitoring of the elderly and cognitively impaired patients. For example, systems can detect falls or abnormal behavior in real time to prevent accidents and improve response times. However, traditional statistical and rule-based reasoning methods often struggle to effectively handle uncertain and dynamic healthcare environments when faced with large-scale, heterogeneous sensor data [5].

Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT): In industrial scenarios, activity recognition plays a key role in keeping workers safe and optimizing production processes. For example, in factories, detecting deviations in the workflow or identifying dangerous behaviors can effectively prevent workplace accidents and improve operational efficiency. However, existing methods mostly rely on large-scale data collection and analysis, leading to high energy consumption and low efficiency, especially in large-scale industrial deployments.

Research Innovations and Contributions:

In response to the above challenges, this paper proposes an ontology matching-based anomalous activity recognition method for a variety of application scenarios such as smart space, healthcare and industrial IoT. The main innovations of this paper are as follows:

1. Ontological context modeling: An ontology modeling approach is used to semantically describe contextual information, enabling the system to reason about complex scenarios [6] and improve recognition accuracy and interpretability.

2. Multi-level activity categorization system: A multi-level activity categorization framework is designed to classify activities into predefined and inferred categories, and further distinguish static and dynamic activities. This categorization improves the recognition accuracy and also enhances the system’s ability to respond to anomalous activities [7].

3. Event Sequence Segmentation Optimization: Accurate event sequence segmentation is the key to activity recognition. In this paper, we propose a segmentation method that combines location-awareness and time-interval reasoning to improve the accuracy of activity recognition using ontological reasoning.

Through comparative experiments with existing techniques, the method in this paper demonstrates significant advantages in several real-world scenarios [8]. Unlike traditional rule- or statistics-based methods, the ontology matching method in this paper is able to perform efficient contextual reasoning and activity recognition for large-scale, multi-source sensor data. The method can not only quickly identify potential associations between data and improve the reasonableness and accuracy of inference, but also extend and adapt new activity patterns in different scenarios with excellent scalability and adaptability to effectively recognize new activity patterns, which is a key concern in the current research field.

Ontology matching is crucial for knowledge representation and integration because it can integrate different ontologies and facilitate data exchange. Deep learning has achieved remarkable results in various fields such as natural language processing [9]. It can learn the distributed representations of concepts and entities in ontology matching to improve the accuracy and efficiency. By systematically exploring the application of deep learning in ontology matching, the aim is to answer key questions such as common methods, advantages and disadvantages, evolution, and research directions and make significant contributions to the existing literature on ontology matching using deep learning techniques [10]. Sensor technologies are widely used in many fields, such as healthcare, home life, industrial technology, safety, and security. A review of related literature focused on the potential of ontology technology in manufacturing, home appliances, robotics, defense, and geographic information science [11]. Smartwatches and smartphones have enhanced their functionality by embedding a variety of rich sensors, opening the prospect of applications in real-time healthcare, traffic monitoring, environmental monitoring, security, gaming and entertainment, and social networking. One study proposed an energy-efficient framework of sensors embedded in mobile devices for the automatic recognition of human states and state transitions. However, in complex strategic environments, the large-scale sensor data integration of smartphones and smartwatches in space, time, and content is very difficult, especially for real-time decision-making tasks.

This paper introduces an agent-based framework that seamlessly integrates sensor data exchange with context-aware knowledge. However, its scalability remains a challenge, highlighting the need for further optimization in large-scale applications. Currently, most context-aware systems rely on brute-force methods for sensor data collection and analysis, leading to inefficient resource utilization and significant energy waste due to the underutilization of valuable data and observations.

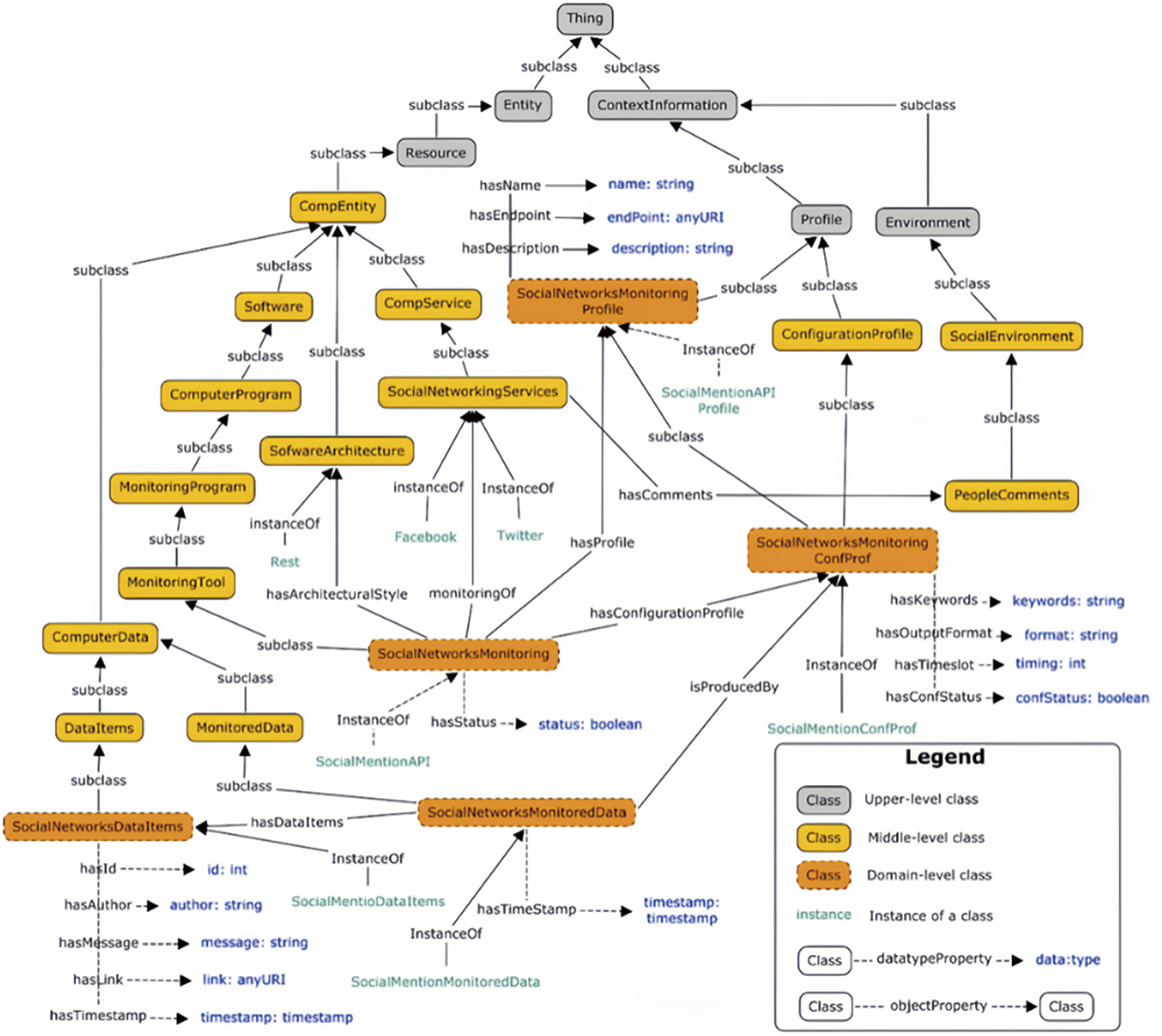

Several studies have investigated the role and foundation of ontologies in context modeling, particularly in context-aware systems [12]. These studies not only described the basic design features of context-aware systems, but also analyzed the applicability of and differences between different context models in detail. Some researchers have further explored the need for modeling different contexts, described the abstraction process of high-level contexts in detail, and conceptualized various context-based ontology models. Other studies have explored the applicability of ontologies in the semantic annotation and representation of sensors and their networks and emphasized the importance of establishing common standards to facilitate the integration and interoperability of sensor data.

Smartphone sensors have similar functions to traditional sensors but are more widely used because smartphones not only integrate sensing capabilities but also incorporate powerful processing, storage, and communication technologies that transform them into feature-rich smart devices. However, the existing sensor network ontology has not been fully adapted to the needs of context-aware smartphone applications.

Several ontologies have been used to model and recognize human behavior and situations, with Standard Ontology for Universal Adaptation (SOUA) and Contextual Ontology (CONON) being the most representative ontologies for situation recognition [13,14]. These ontologies are highly generalizable and can be extended to specific domains. The Contextual Agent Architecture (CAA) is based on the SOUA ontology, whereas Service-Oriented Context-Aware Middleware (SOCAM) extends the CONON ontology [15]. In a research study, an ontology-based context recognition system using accelerometers, gyroscopes, vision, and environmental sensors for context recognition was proposed [16]. However, this system does not provide a detailed definition of the object context for activity reasoning in the ontology. Another study proposed an ontology-based activity recognition system that specifies the human posture, position, and object context using activity modeling [17]. Other studies have focused on context detection in the form of activities such as location perception. Activity is an activity recognition method that combines statistical and ontological reasoning mechanisms.

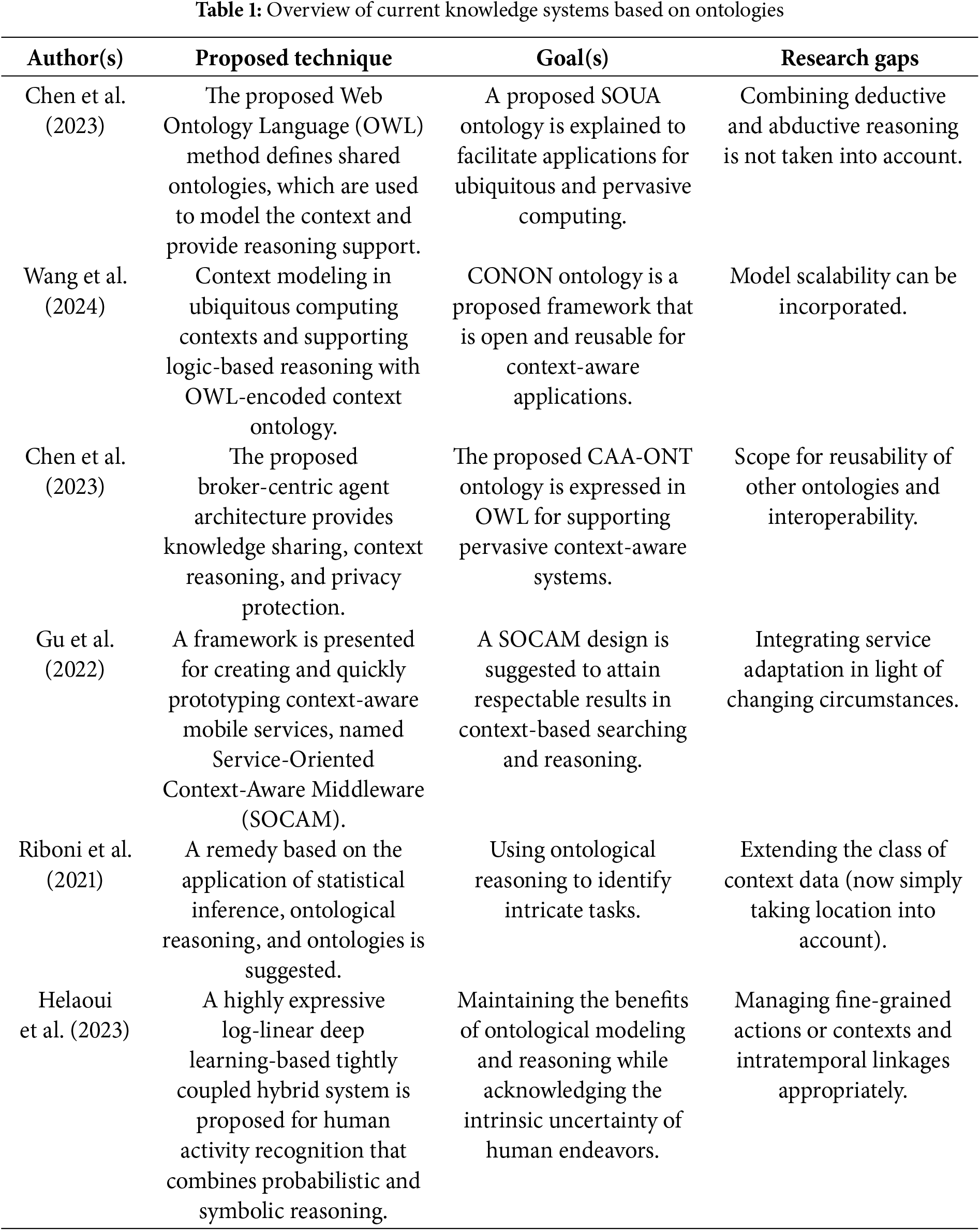

Some scholars have proposed ontology-based systems for context recognition using a multi-level approach with ontologies that conceptualize different types of activities or gestures, including atomic gestures, complex gestures, simple actions, and complex activities [18]. Others have proposed a fuzzy logic-based ontology for reasoning and inference when dealing with uncertainty and unknown data [19]. The ontology covers four domains: user, behavior, location, and actions in the user’s environment. Table 1 lists existing ontology-based knowledge systems, techniques, and goals.

2.2 Motivation and Research Gaps

To realize the full potential of emerging sensor technologies, there is an urgent need for a well-established common platform to express the various dimensions of sensors and their sensing processes comprehensively [20]. At present, several sensor devices and measurement specification standards exist that provide a unified format for sensor data repositories and applications to address data heterogeneity. However, these requirements fall short when it comes to providing semantic descriptions, especially for complex activities that involve logical reasoning. To enhance semantic compatibility and interoperability, semantic technologies such as OWL, RDF, and SPARQL can introduce a semantic layer for sensor devices and observational data. In this context, ontologies are used to semantically annotate temporal, geographical, and thematic metadata onto observed data, thereby improving interoperability, clarifying axioms and norms, and mapping relationships between various terms [21]. In activity analysis, the effectiveness of reasoning mechanisms relies on the semantic annotation of sensed data, ensuring that semantically processed information aligns with open-world assumptions and supports more advanced inference capabilities.

Through the use of the semantic mechanisms of ontologies, certain unknown information is inferred during semantic reasoning rather than being explicitly regarded as missing. In addition, the integration and interoperability of heterogeneous sensor data can be enhanced using ontologies, allowing the reuse of contextual information to assist situational awareness in systems that recognize human behavior. The creation of ontologies can revolutionize context-aware applications in smartphones and smartwatches through a wide range of data representation models that not only add newly inferred attributes to the data but also identify latent relationships that are not yet revealed in the original data. Ontologies also simplify the implementation of knowledge management by separating the application and operational knowledge layers.

Current smart device-based context-aware applications are good at spotting human activity, but they still struggle to handle unprocessed sensor data and measurements. It is challenging to adjust to dynamic changes since even little modifications to the environment necessitate redesigning the entire program. Furthermore, developers desperately need actionable knowledge and information—which are frequently not readily available from raw sensor observations—when creating realistic apps. Consequently, one of the biggest challenges nowadays is efficiently handling, displaying, processing, and evaluating the vast volume of data gathered by sensor devices like smartphones and smartwatches. Applications for context awareness and human activity detection will be greatly aided by the rich semantic encoding and interpretation of sensor and observation data made possible by state-of-the-art semantic technologies.

3 Ontology-Based Context Modeling in the Smart Home

3.1 Analysis of Ontology-Based Context Modeling

For the anomalous activity detection problem proposed in this study, a formalized description of the activity is crucial. A large number of current inference models only study the person who produces the behavior in isolation, while ignoring the scene in which the person is located, which reduces the inference accuracy. In this study, the research on abnormal activity detection combines the realization of context-aware technologies in smart spaces. First, an ontology is adopted to model the smart home, which is centered on activities of daily living (ADL), including scenes, sensors, users, and related attributes and instances. The problem of sharing heterogeneous data is resolved through ontological context modeling, and it serves as the foundation for semantic reasoning, which can be applied to the sharing of domain knowledge. Ontology-based domain modeling is machine understandable, scalable, and has strong formal expression capabilities. For the smart home ontology developed in this study, the core ontology is extended in accordance with the particular requirements, and the extended ontology is created and instantiated one step at a time. This study examines the daily activities of regular users and classifies user activities into multi-tasking interaction scenarios to categorize activity information, considering the suitability and generality of the activity ontology. The following two activity classification methods are suggested:

(1) Classification according to the method of generating activity information

Activities that are prepared or documented ahead of time in accordance with the user’s everyday behavior are referred to as predefined ADLs. This kind of activity data is comparatively stable and can be automatically gathered by the system beforehand or pre-configured by the user. Simple actions and complex scenario activities make up the majority of the predefined activities. The activity status is used to further categorize simple actions. Activities in the kitchen and bedroom, for instance, are further divided into particular contextual activities like housework and cooking. Getting up and watching TV are two activities that take place in the bedroom. The activity performer (user), activity performer location, activity start time, and activity finish time are the primary components of the activity attributes.

Deduced ADL: This type of activity information is derived by reasoning based on the simple behavior information of the detected user, scene information, and predefined activities.

(2) Classification according to the state of activities

Based on the predefined activities of simple actions, they are classified into static and dynamic actions, according to the state of the activity.

Static action: squatting, sitting, standing, lying down, bending, etc.

Dynamic action: sitting up, standing up, turning around, walking, jogging, running, etc. Research on activity recognition has mainly focused on walking, jogging, and running.

Current research on activity detection focuses on normal activities; however, the detection of abnormal activity is the most important task in safety monitoring.

(3) Classification of complex activities derived from reasoning from the perspective of intelligent assistance

The key of this study lies in the identification of abnormal activities, which is mainly analyzed from the perspective of security monitoring and intelligent assistance, and the complex activities derived from reasoning can be further classified into normal ADL and abnormal ADL.

Normal activity: Normal activity includes a series of daily behavioral activities, mainly referring to the activities that occur at the right time, place, and occasion.

Abnormal activity: An activity that does not fall within the scope of everyday behavioral activities and does not match predefined scenario activities. For example, kitchen activities may include simple actions, such as standing and sitting. Complex activities include cooking, housework, and standing in the kitchen. If the kitchen activity generated by the inference is lying in the kitchen, it obviously does not match the kitchen activity; therefore, it can be judged as generating anomalies.

The basic behaviors and predefined scenario activities described above can be stored in an ontology repository for persistent storage. Complex activity information can be inferred by combining simple activity and scenario information. After storing the complex high-level activities in the ontology library, to recognize whether an abnormal activity has been generated, it must be obtained by matching with predefined scene activities. Therefore, this study proposes an abnormal activity recognition method based on ontology matching, in which the complex activities derived from reasoning are matched with predefined scene activities when they are stored in Deduced ADL; the resulting unsuccessful matches are stored in Abnormal ADL as abnormal activities, which are further processed by the system.

Fig. 1 shows a smart home ontology model with activities (ADL) at its core, which can be created using the Protégé ontology builder.

Figure 1: Smart home ontology model (OWL Diagram)

An ontology repository can permanently store the aforementioned tasks. Complex activity information can be obtained by integrating simple activity information. Existing ontology resources must be considered before ontology construction, and the ontologies published by authoritative organizations have very high reference values. In this study, we rely on the existing smart space ontology, DogOnt, when constructing the scene ontology.

3.2 Custom Rule Creation Based on Ontology Reasoning

In this study, we consider activity recognition as an induced reasoning task for obtaining high-level complex activity information through a rule-based reasoning approach. Customized rules are created to establish semantic relationships between activity ontologies and other ontologies. The custom rules are created by extracting the relevant properties (including object and data properties) from the ontology and then matching the existing knowledge in the ontology library with the predefined rules to derive implicit information.

For example, the user is in the kitchen and generates a series of kitchen activities (predefined activities) such as cooking and washing dishes. Action behaviors include static behaviors such as squatting, sitting, and standing. Dynamic behaviors include squatting, sitting, standing, standing up, turning around, and walking. If the sensor detects that the user is static and lying down, it is inferred that the user is lying in the kitchen.

The description of the created rule is as follows.

@prefix u:<http://http://www.Semanticweb.org/ontologies/2014/5/User.owl#>.

@prefix act:<http://http://www.semanticweb.org/ontologies/2014/5/Lying.owl#>.

@prefix sce:<http://http://www.semanticweb.org/ontologies/2014/5/Kitchen.owl#>.

@include<RDF>.

[rule1: (? user: has Activity ? b) (? b rdf: has State act: Lying) ((?

user: is Located In ? c) (? c rdf: has Type sce: Kitchen) →(? user: has P-

re Activity Kit Activity)) →(? user rdf: Lying in the Kitchen)]

The above rule represents the inference for deriving the state of the user lying in the kitchen (Lying In Kitchen), taking the simple static behaviors lying (Lying) and in the kitchen (Located In Kitchen) as the inference conditions to produce the kitchen activity, which yields the implicit knowledge that the user is lying in the kitchen (Lying In Kitchen). This does not match either the simple behavior or the complex high-level activity in the kitchen activity (Kitchen Activity), thus generating the anomaly.

Identifying users’ everyday actions in a smart space (ADL) using ontological reasoning can produce new information or high-level complicated activities. For instance, it can be assumed that A is sleeping if a sensor finds that A is in a bedroom with the curtains closed and the light level low. In order to extract the latent knowledge in explicit definitions and declarations, the ontological reasoning process mainly makes use of the reasoning principles offered by OWL itself, such as transitive and symmetric properties. Since the ontology-based reasoning method is unable to effectively identify abnormal activities, this study proposes an ontology matching-based methodology to further identify the abnormal activity techniques based on this premise.

4 Anomalous Activity Detection Method Based on Ontology Matching

4.1 Basic Concepts of Ontology Matching

The basic idea of ontology matching is to discover inter-semantic relationships, and the matching can analyze the similarities and differences between concepts to predict their semantic compatibility.

Semantic similarity is an important criterion for determining semantic relationships. In this study, ontology matching is used to discover the similarity between semantics and, in the process, to identify the incompatible parts for abnormal activity detection. The basic concepts of ontology matching are analyzed using structural layer-based matching, where classes and instances in the ontology are considered as nodes in the structural layer, and attributes and relations in the ontology are analyzed as edges in the structural layer. First, some basic definitions are provided.

Definition 1. Similarity of nodes

where

The similarity of ontology concept 3 is composed of the weighted similarity of all nodes and edges, and the formula is as follows:

where

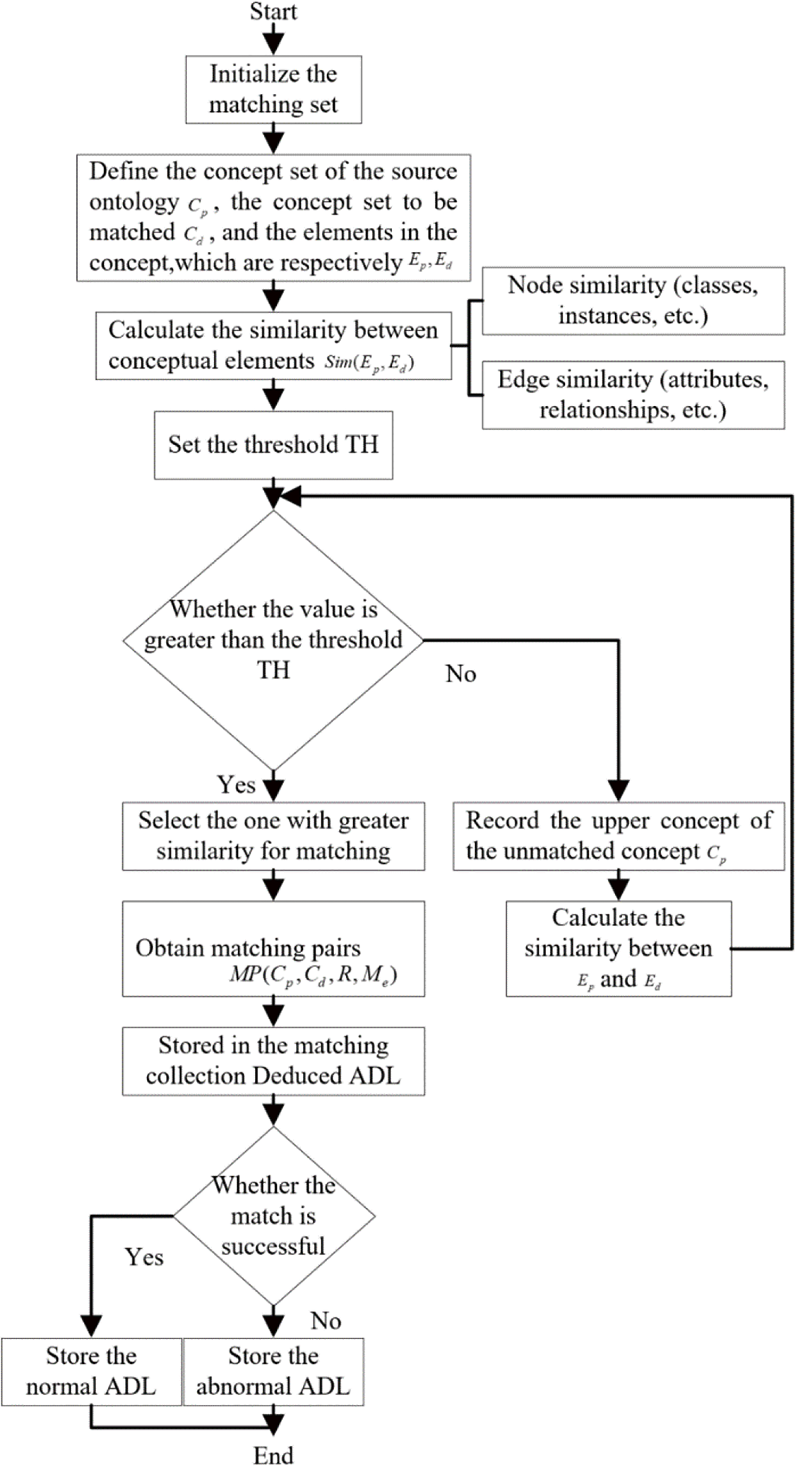

The basic flow of the ontology matching is analyzed in the following and shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the ontology matching algorithm (Algorithm 1)

4.2 Ontology Matching-Based Anomalous Activity Detection Method

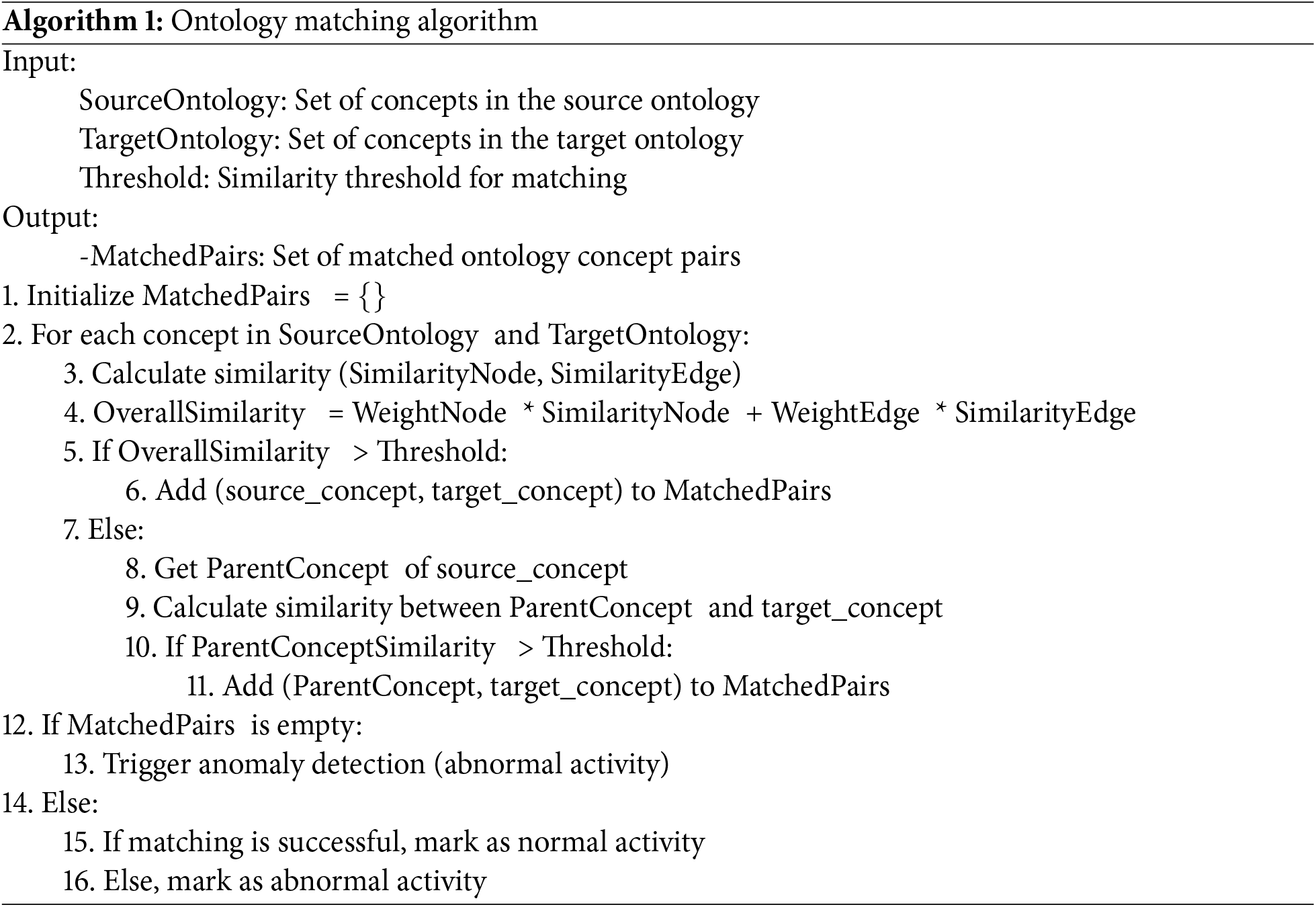

The flow of the ontology matching-based anomalous activity detection method is shown in Fig. 3. The following is a detailed analysis of Algorithm 2.

Figure 3: Flowchart of anomalous activity detection based on ontology matching

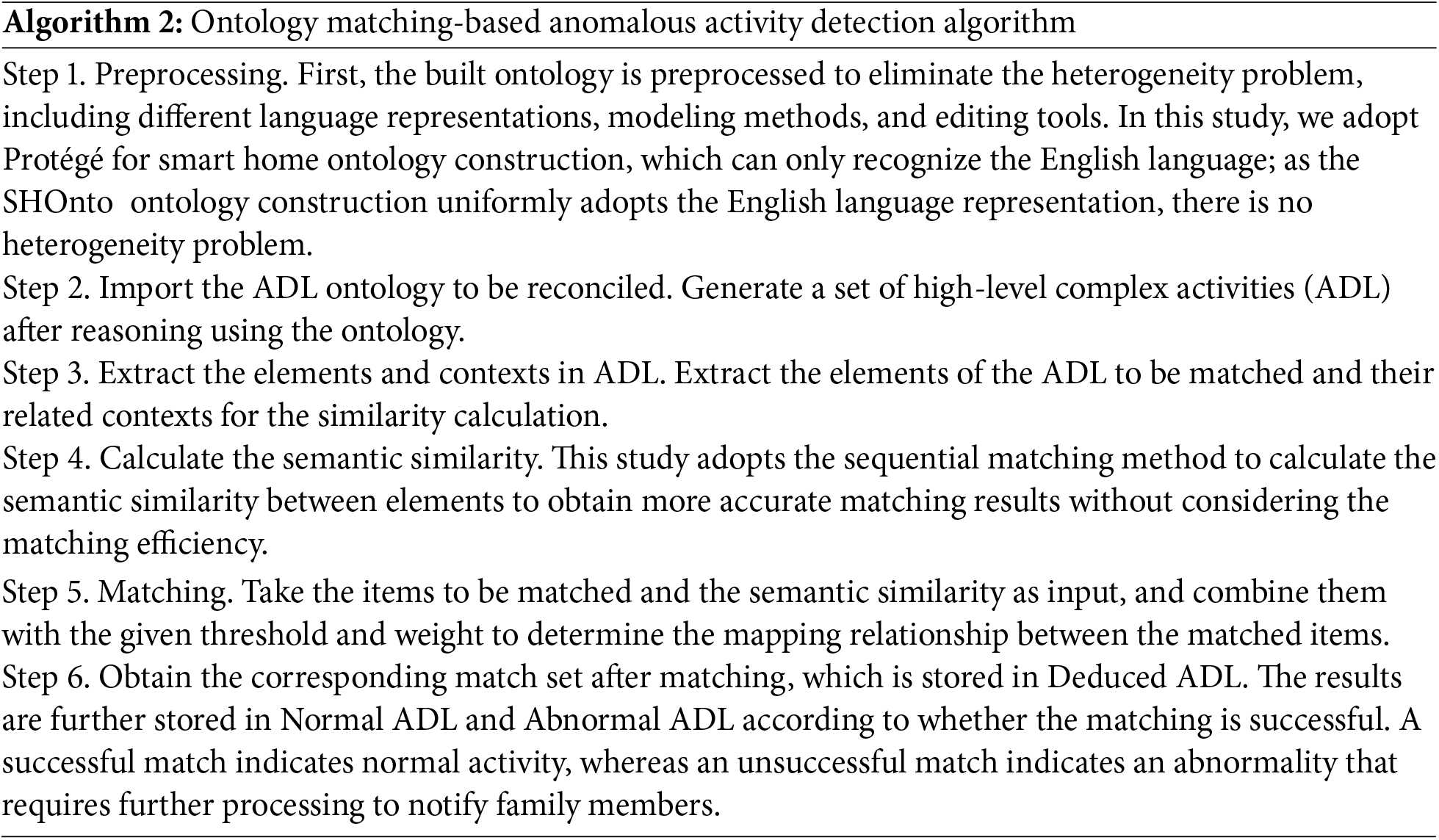

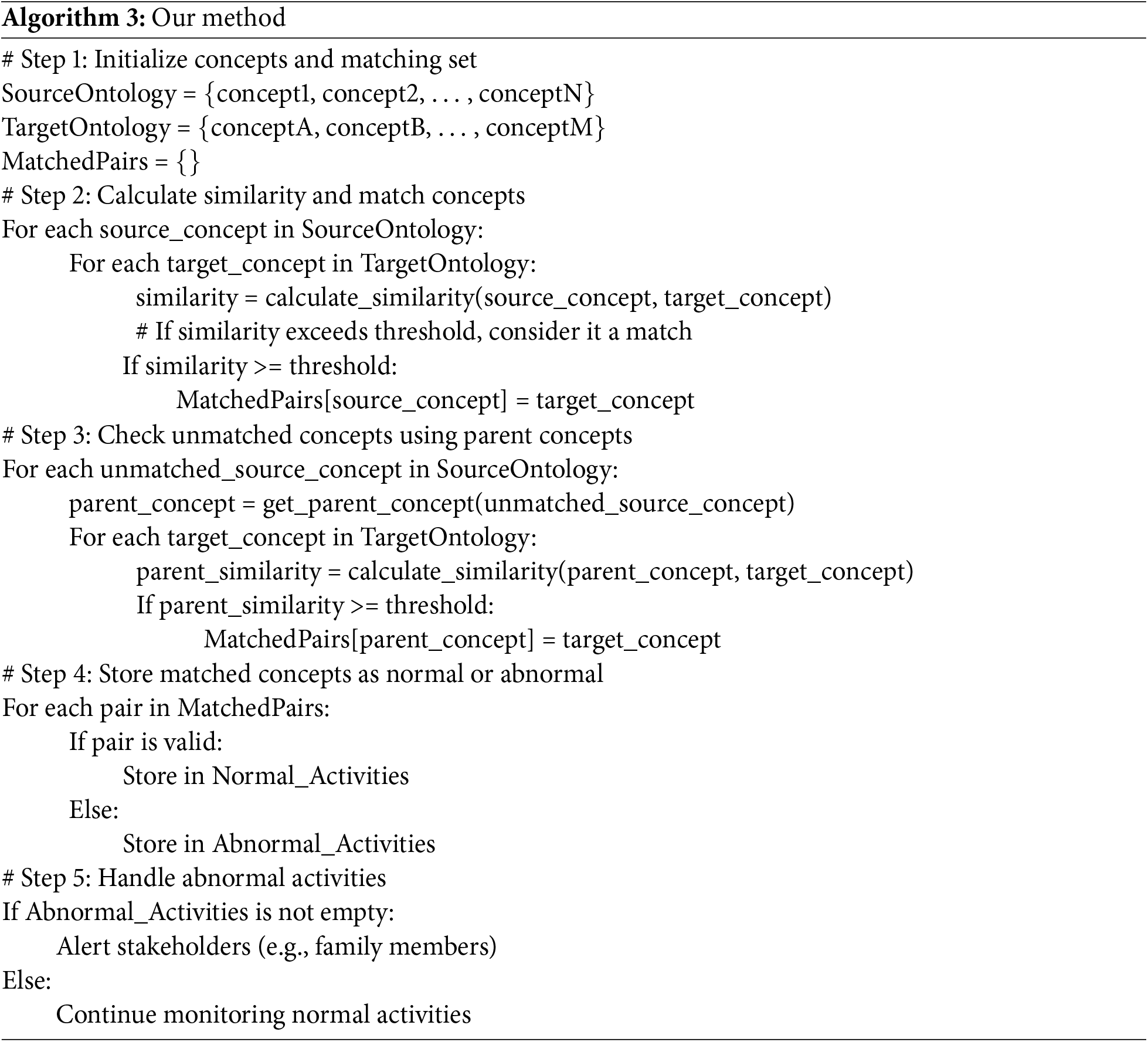

The entire algorithm implementation process is shown in Algorithm 3.

Define the source and target ontology concepts and initialize the matching set. Systematically compare each pair of concepts from both ontologies and determine whether they satisfy the predefined similarity threshold. For unmatched concepts, attempt matching using the parent concepts. Classify activities into “normal” or “abnormal” based on the matching results. If abnormalities are detected, notify stakeholders.

4.3 Analysis of the Ontology Matching-Based Anomalous Activity Detection Method

Ontology-based reasoning is the foundation of the suggested ontology-matching-based anomalous activity detection technique. Initially, an activity-centered domain ontology is built, and the high-level complex activities (ADL) derived from basic user behavioral activities are realized via ontology reasoning. The ontology matching approach is then used to match the reasoning-derived activities (De-reduced ADL) with predefined scenario activities (Predefined ADL) and determine how comparable they are once the reasoning results are saved in the ontology library. The activities (Derived ADL) derived from reasoning are compared with the predefined scenario activities (Predefined ADL) using the ontology matching method. The similarity between the two is calculated, and a set of matches is derived, with the incompatible components (concepts with unsuccessful matches) being regarded as anomalous activities. Lastly, the system uses the resulting anomalous behaviors to give the proper service actions. The weighting employed in the ontology matching process might lessen the impact of dissimilar sections on the similarity, according to the given ontology matching method. Furthermore, the concepts of the previous layer in the source ontology are compared with the unmatched concepts in the ontology to be matched. This eliminates the issue of inconsistent granularity delineation between the concepts and guarantees that there are no mismatches, resulting in a more accurate matching result and, consequently, a more accurate detection of abnormal activities.

4.4 Handling of Noisy or Missing Sensor Data

To mitigate the impact of sensor failures, the system is designed with redundant sensors where possible. If one sensor fails, the data from other sensors in the same context can be used to fill in the missing information. For example, if an RFID sensor fails to capture the user’s position, other sensors (e.g., infrared or motion sensors) can provide backup data.

The system includes failure detection mechanisms that identify when sensor data is missing or unreliable. Once a sensor failure is detected, the system can either attempt to interpolate the missing data based on historical patterns or flag the data as invalid for further processing.

To handle data sparsity, especially in scenarios where some sensor data may be sparse or incomplete, the system employs data fusion techniques. By combining data from multiple sensors, the system can create a more complete and robust representation of the user’s activity. For example, integrating data from both RFID and inertial sensors can help fill gaps in activity recognition when either of the sensor types provides incomplete data.

The system uses context-aware reasoning to fill in missing data based on the known environment and activity context. For instance, if the system detects that a user is likely performing a known activity based on partial sensor data, it can infer the missing information based on this context, minimizing the impact of sparse data.

To prevent strong outliers from affecting activity recognition, statistical outlier detection techniques are employed. For example, any data points that deviate significantly from expected sensor readings are flagged as outliers and excluded from the matching process. Common techniques such as z-score analysis, interquartile range (IQR), or clustering-based methods are applied to detect and filter out extreme values.

In the case of missing sensor data during ontology reasoning, the system leverages the inherent structure of the ontology to infer missing information. For example, if the system cannot determine a user’s precise location due to a sensor failure, it can reason based on nearby sensors or previously recorded behaviors to infer the most likely activity or location.

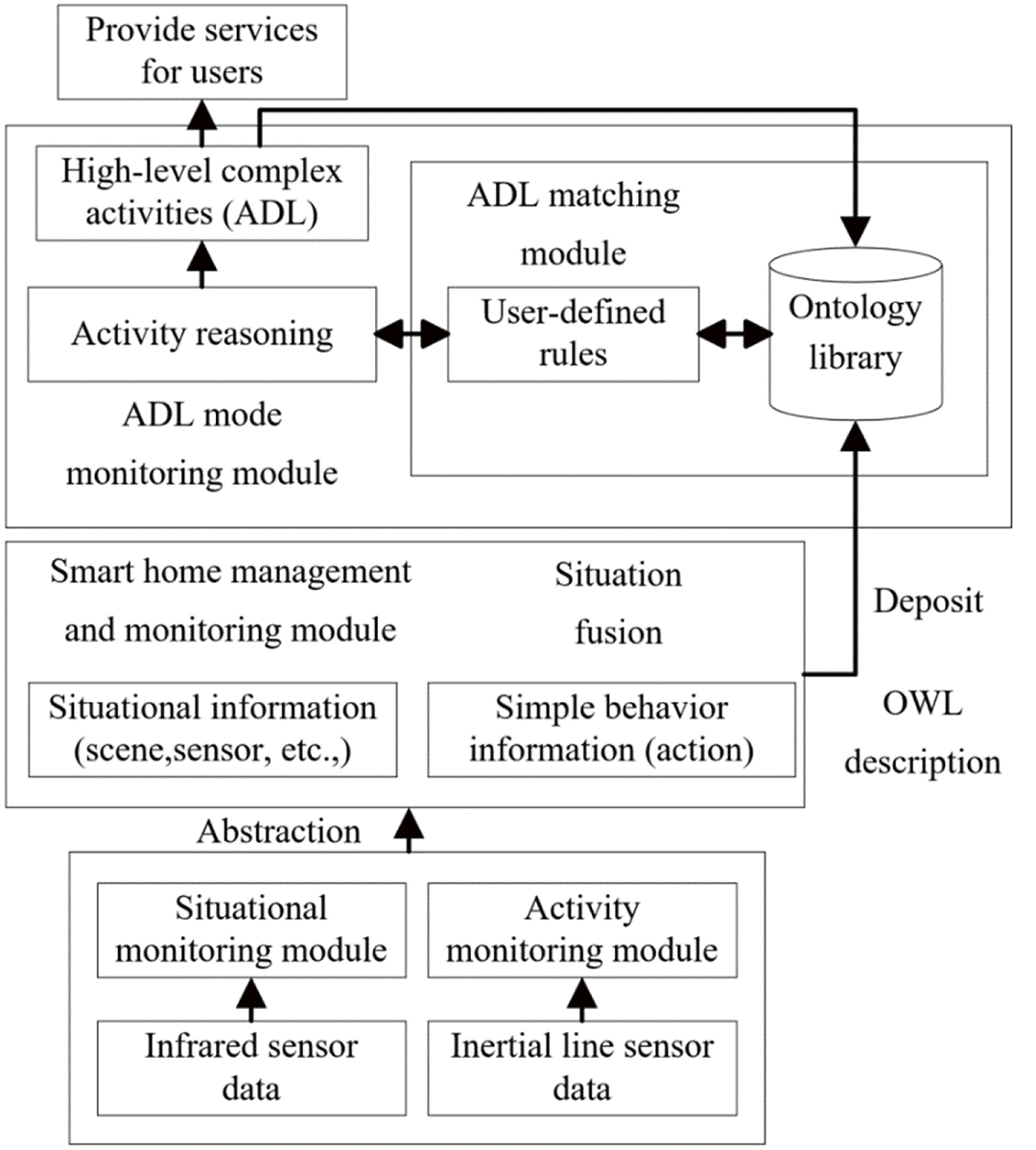

The architecture of the Anomalous Activity Recognition System (AARS) is shown in Fig. 4, which provides a solution for the anomalous activity recognition method proposed in this paper. Overall, it is divided into four modules: the data acquisition, context fusion, ADL pattern monitoring, and service modules. The user’s position information in a scene can be obtained using an infrared sensor system, simple behaviors can be obtained using an inertial sensor module, and high-level complex scene activities can be obtained using ontological reasoning. The data generated by the data acquisition module are submitted to the context fusion module and the mapping method is used for information fusion processing. The fused information is stored in the ontology library and reasoned using a set of customized rules to obtain the ADL currently performed by the user. The proposed ontology matching method is used to match the reasoned activities with the predefined scenario activities to derive anomalous activities. The activity-centric smart home ontology proposed in this study was created using the Protégé tool. The smart home ontology includes entities and attributes such as scenes, activities, sensors, users, and their corresponding relationships. The system reasoning module was implemented using Jena, which is a Java framework for building semantic web applications that provides a programmable environment for OWL and a rule-based reasoning engine. The service module provides appropriate services to the user by analyzing abnormal activities. For example, family members should be notified that help will be available in a timely manner.

Figure 4: Anomaly detection system architecture

In this study, the system scheme was deployed in the smart space laboratory, where 12 electronic tags were tied to the experimenter’s body to indicate the user’s position with the tag position coordinates; the tags were attached to the elbow, wrist, hip, knee, and ankle. The sampling frequency was 60 Hz, the coordinates of the tags were acquired by the motion capture system, six RFID sensors were embedded into the wall, and the tags were attached to the user’s body to capture the user’s movements. Sensors are also used in devices such as home appliances in smart rooms. The system runs on an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-3210MCPU 2.5 GHz Duo processor host computer with 6.00 GB of RAM and 800 GB of hard-drive capacity. The data had a standard noise deviation of 0.8 mm. The position of each object’s sensor tag was recorded in a session that lasted for 3 to 5 s. In addition, the simple behavior of the user was captured by an inertial sensor system that recorded acceleration data for each of the 10 tags: upper and lower arms, thighs and ankles, chest, and waist, with 100 Hz samples, and sent the data to the computer via Bluetooth.

The accuracy and false alarm rate were used to assess the experimental results to confirm the validity and viability of the proposed approach. The ability of the algorithm to provide accurate matching results is measured by its accuracy. The incidence of false alarms indicates that aberrant behavior occurs but is not detected by the system. The following are the formulas for accuracy and false alarm, where the numbers representing the number of abnormal activities that are successfully detected (TP), the number that are unsuccessfully detected (TN), the number of false alarms (FP), and the number of missing abnormal activities (FN) are shown.

Accuracy (Accuracy, %) = Number of activities correctly reasoned by the system/number of activities performed by the user (total number of executions) = (TP + TN)/(TP + FP + TN + FN).

False alarm rate (False Alarm, %) = False alarmed unusual activities/number of activities performed by the user = FP/(FP + TP).

To validate the viability and efficiency of the proposed anomalous activity detection technique, a series of experiments were conducted using representative examples. An activity-centric smart home ontology was developed using the Protégé tool, which serves as the foundation for modeling and reasoning about user activities.

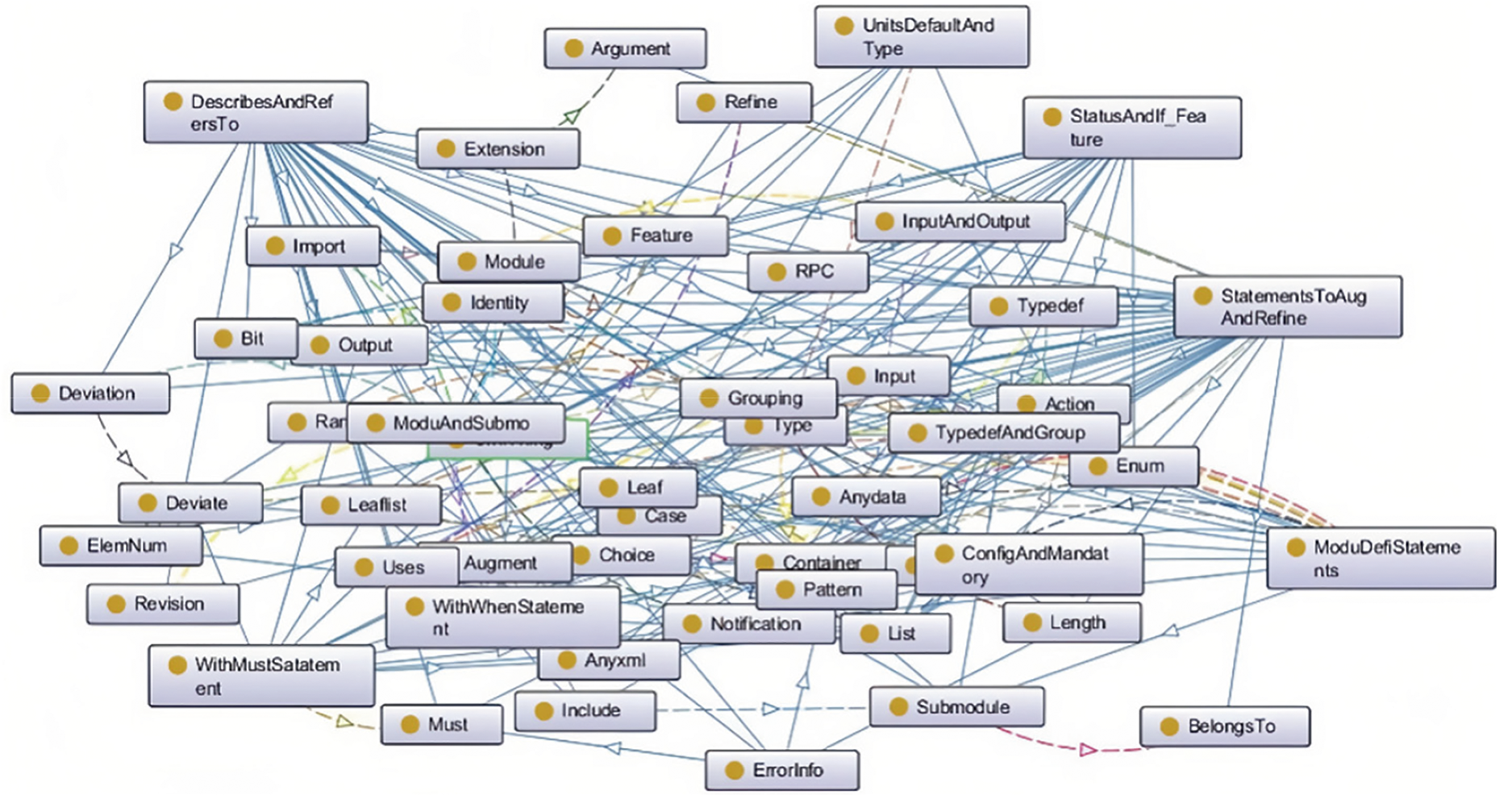

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the Onto-Graph diagram generated by Protégé provides a structured representation of the smart home ontology, encompassing key entities such as Activities of Daily Living (ADL), sensors (Sensor), users (User), and their associated subclasses and instances. Specifically, the ontology captures both static and dynamic behaviors, where static behaviors are categorized under Simple Behavior in Action, while dynamic activities are further classified under Activity and Simple Behavior in Activity.

Figure 5: Smart home ontology created by Protégé (OntoGraf Diagram)

Furthermore, the ontology distinguishes between different types of actions. For instance, Static Action, which includes actions such as Lying and Standing, represents stationary behaviors, whereas Activity and Action serve as hierarchical subclasses of ADL, encapsulating more complex, multi-step interactions. This structured representation enables efficient reasoning and anomaly detection by leveraging ontology-based inference mechanisms.

These experiments demonstrate how the ontology facilitates the recognition of normal and anomalous activities within a smart home environment, contributing to advancements in intelligent monitoring and assisted living applications.

Fig. 5 (Onto-Graph diagram generated by Protégé) visualizes the structure of the smart home ontology (ontology), which contains the following key entities: Activities of Daily Living (ADL): This category covers the daily behaviors performed by users in the smart home environment, including Simple Behavior in Action (SBIA) and Complex Dynamic Activity in Action (CDA). For example, activities such as “get up”, “sit down”, “walk”, etc., belong to this category, reflecting the user’s behavioral patterns in different contexts.

Sensor: The Sensor category contains a variety of sensing devices in the home environment, such as motion sensors, pressure sensors, temperature and humidity sensors, etc., which are able to sense user behaviors and environmental changes and provide data support for ontological reasoning. For example, pressure sensors detecting the bed state can be used to infer whether the user is sleeping or not, and infrared motion sensors can recognize the activity trajectory in the room.

User: This category defines individual users in the smart home environment, including the elderly, ordinary occupants, etc., and analyzes their behavioral patterns in conjunction with sensing data. In anomaly detection, the system can identify possible anomalies, such as the elderly falling, long time static inactivity, etc., through the user’s activity trajectory and habit pattern, and trigger an alarm.

Static Behavior (Static Behavior) and Dynamic Behavior (Dynamic Behavior): Static Action (Static Action) includes “standing (Standing)” “lying (Lying)” and other activities that do not involve significant movement. Activity and Action represent complex multi-step behaviors such as “Walking from Bedroom to Kitchen”, “Leaving Home”, etc. “etc.” Through this hierarchical classification, the ontology is able to describe and reason more finely about different types of behaviors, improving the accuracy of activity recognition.

Further analysis and application:

The application of ontology reasoning in smart homes is mainly reflected in two aspects: abnormal behavior detection and intelligent monitoring:

Through the ontology structure in Fig. 5, we can see the advantages of the ontology approach in the smart home:

1. structured description of sensing data to improve the interpretability and reasoning ability of the data;

2. improving the accuracy of activity recognition and adapting to complex scenes through hierarchical classification;

3. combining with contextual reasoning, supporting intelligent anomaly detection, and providing effective means for safety monitoring.

In summary, the ontology model is not only applicable to the smart home environment but can also be promoted to medical monitoring, industrial IoT, intelligent pension, and other fields, to achieve a wider range of intelligent scene sensing and anomaly detection.

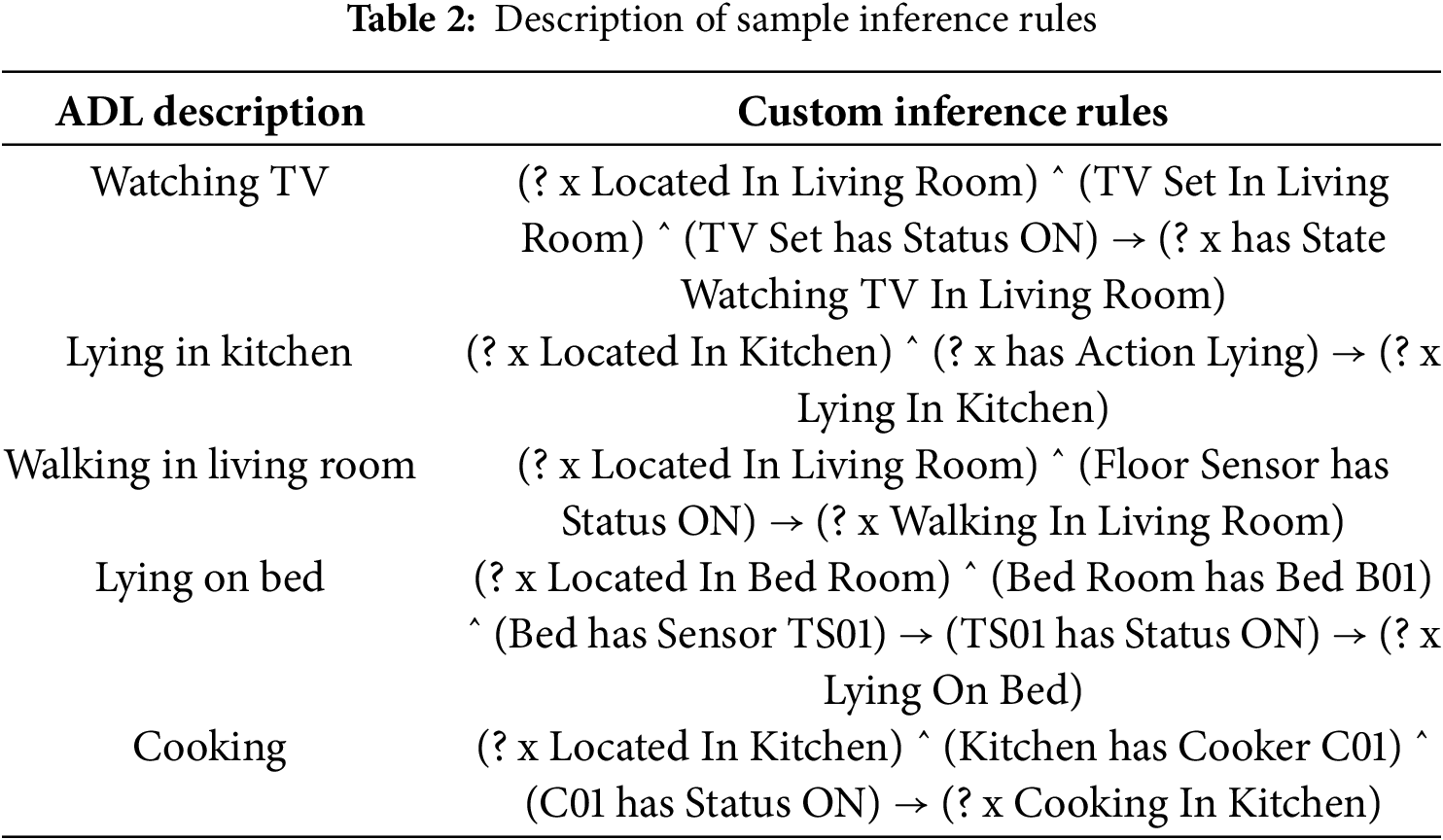

5.3.1 Matching Rules and Effects

The user performed the following five sets of actions in the smart space: watching TV in the living room (Watching TV In Living Room), lying in the kitchen (Lying In Kitchen), walking in the living room (Walking In Living Room), lying on the bed (Lying On Bed), and cooking (Cooking), as shown in Table 2. The actions performed by the user and custom rules created in conjunction with the ontology are described in detail in Table 2.

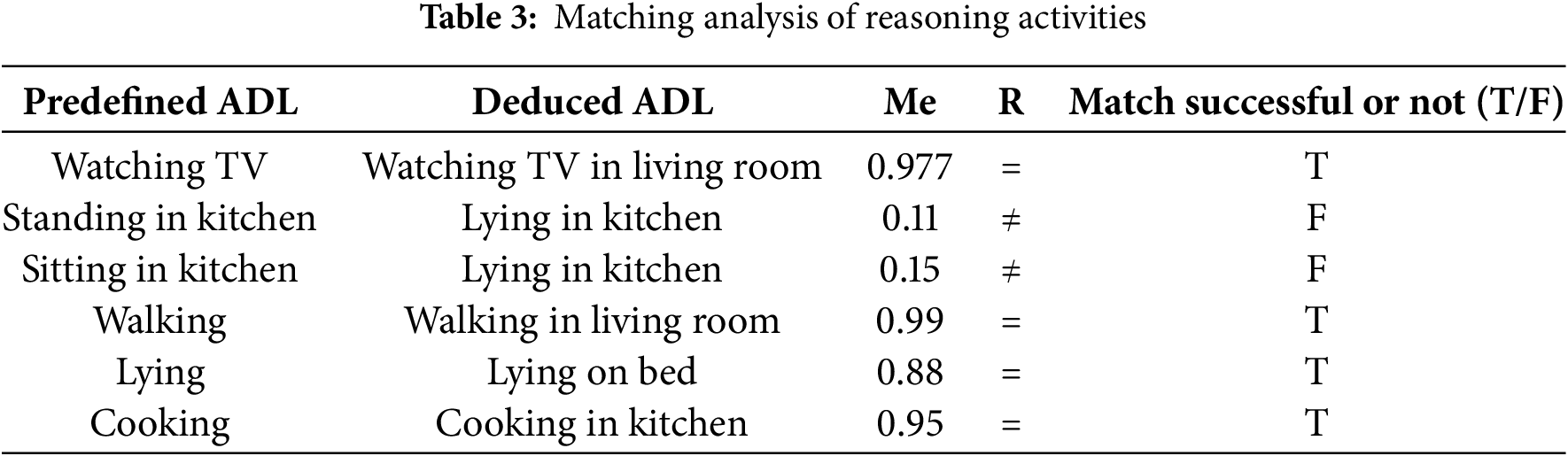

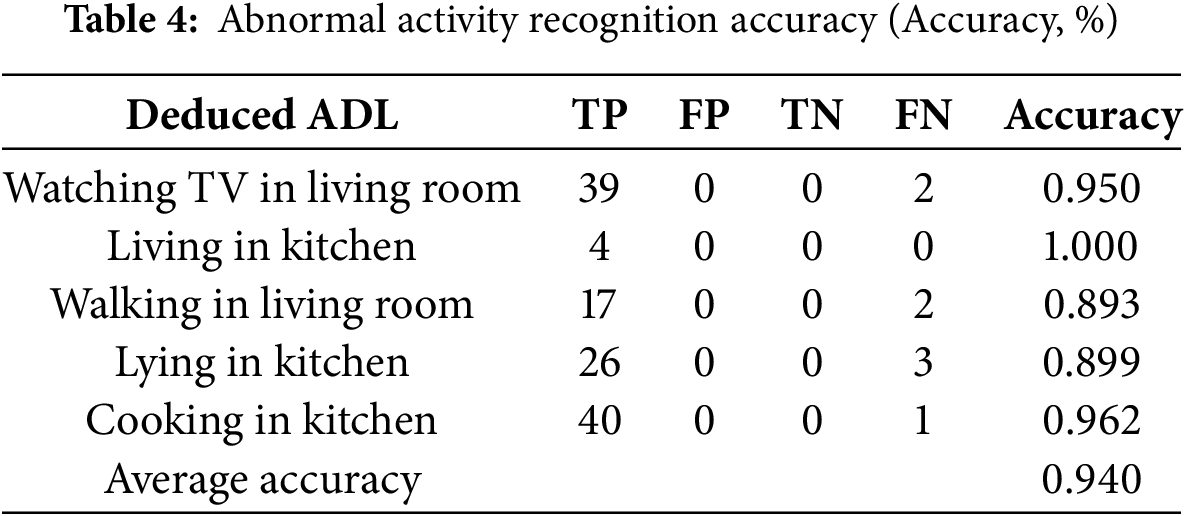

Table 3 shows the analysis of the matching results of the reasoning activities. For the above user-executed activities, the inference results were matched with the predefined scenario activities, and the matching analysis is as follows: Me denotes the similarity between the inference-derived activities and predefined scenario activities and R denotes the relationship between the two, which clearly shows that the matching accuracy was high. The key conclusion is that Lying In Kitchen did not match the kitchen scenario.

In the experiment, many users were selected to complete each of the five activity categories presented in Table 1, and recognition was performed using the technique suggested in this study. Table 4 presents the recognition outcomes. The identification results show that the proposed approach could accurately and successfully identify the tasks performed by users.

In addition, this study compared the proposed anomalous activity recognition method based on ontology matching with a method based on sensor data from the literature [8] and tested the accuracy and false alarm rate of the two methods. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Comparison of experimental results

In Fig. 6, the horizontal coordinates represent the false alarm rate (False Alarm) and the vertical coordinates represent the accuracy rate (Accuracy) of the anomalous activity recognition. It can be observed that the proposed method was significantly better than the traditional data-based abnormal activity recognition method. For some groups of activities proposed in this paper, it can be observed that the false alarm rate of the sensor data-based anomalous activity recognition method proposed in the literature [8] increased and the accuracy rate was low, whereas the false alarm rate of the proposed method generally tended to be stable, while the accuracy rate was also high. Therefore, the proposed method has certain advantages over the traditional sensor data-based abnormal activity detection method.

5.3.3 Comparison of Deep Learning Performance

In order to solve the problem of threshold selection, the event sequence segmentation method proposed in this paper establishes predetermined thresholds by combining location-aware and time-interval reasoning. These thresholds are used to segment the event sequences more accurately and to achieve more accurate activity recognition by matching the composite activities of human behaviors (e.g., “cleaning” or “preparing soup”) formed during the inference process with the actual scenes. When selecting the threshold value, it can be adjusted according to the needs of different application scenarios. Specifically, the selection of thresholds can be calibrated based on the following aspects:

1. location-aware thresholds: according to the spatial distribution of sensors, a reasonable spatial distance threshold is set to ensure that the positional changes in the event sequence can effectively reflect the changes in the actual activities.

2. time interval thresholds: set reasonable time interval thresholds according to the temporal characteristics of the activities to ensure that the time intervals between different activities are correctly recognized in the inference process.

The calibration of these thresholds enables better adaptation to different activity scenarios and improves the accuracy of event sequence segmentation. To help readers better reproduce the method, the selection of thresholds can be adjusted by experimental data or manually adjusted according to the characteristics of specific application scenarios.

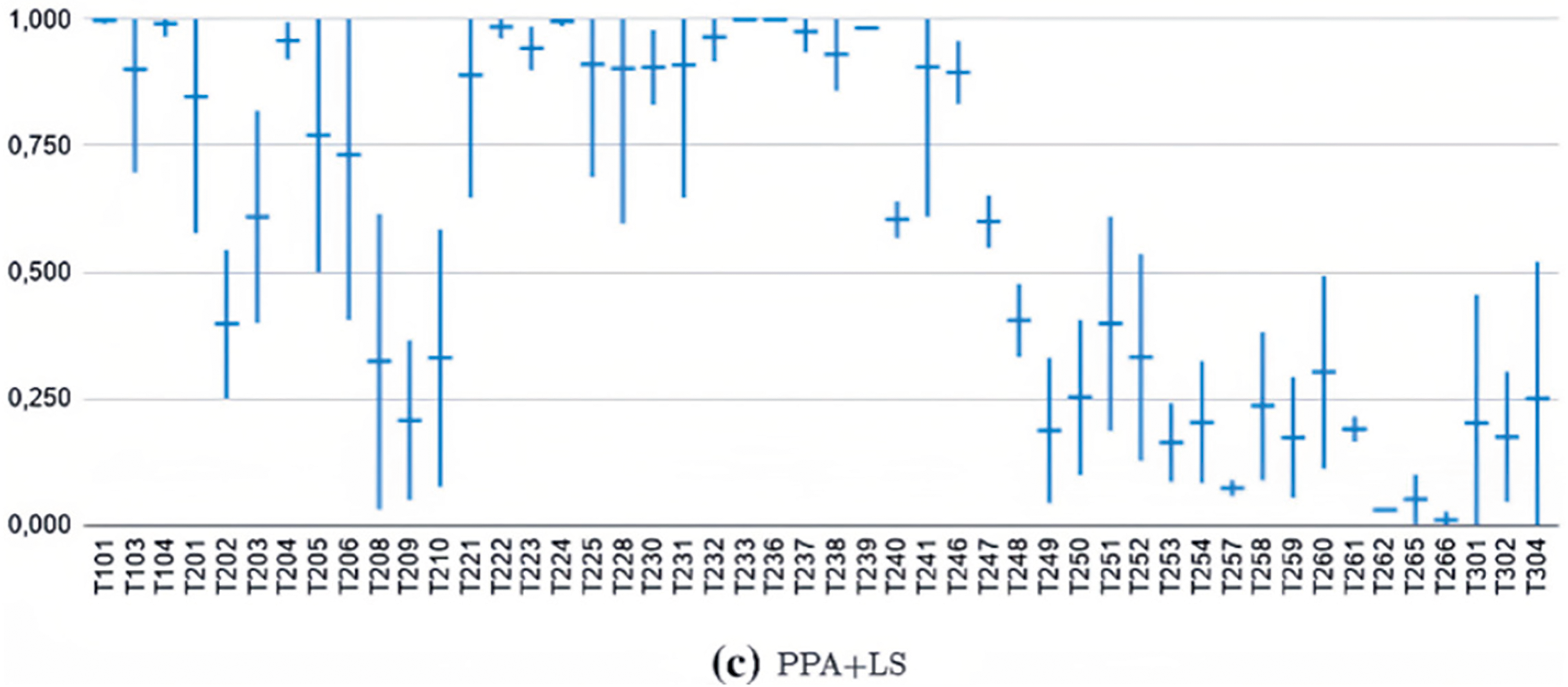

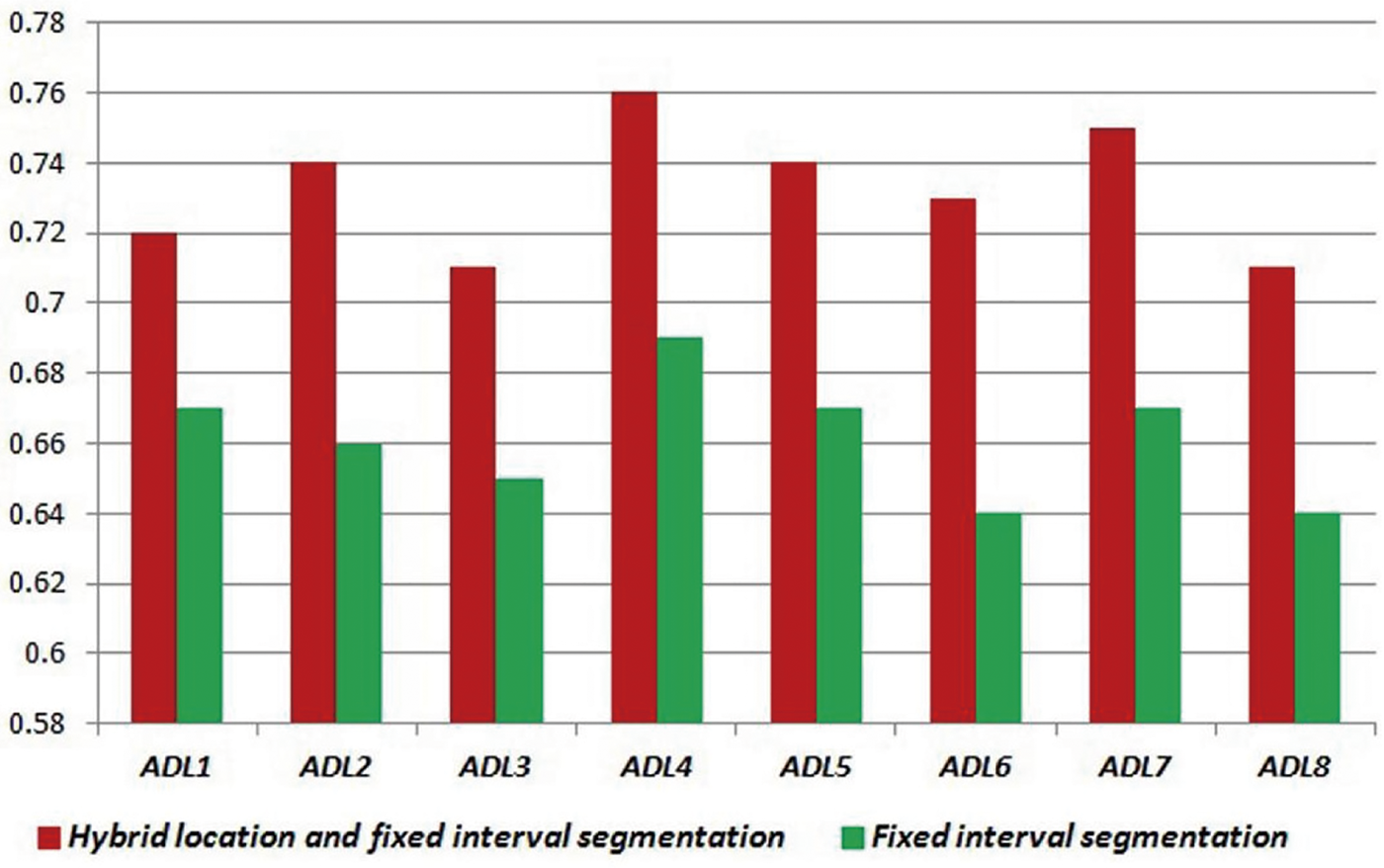

Fig. 7 compares the results of the fixed time interval segmentation method with those of the mixed location and fixed time interval segmentation method. The resulting event sequences were largely incomplete, which contributed to the relatively low accuracy of the fixed time interval segmentation techniques. By reasoning about location and time, the ontological reasoning method presented in this study can identify and produce entire event sequences more precisely, thereby increasing the precision of human activity recognition.

Figure 7: Comparison of results of segmentation methods

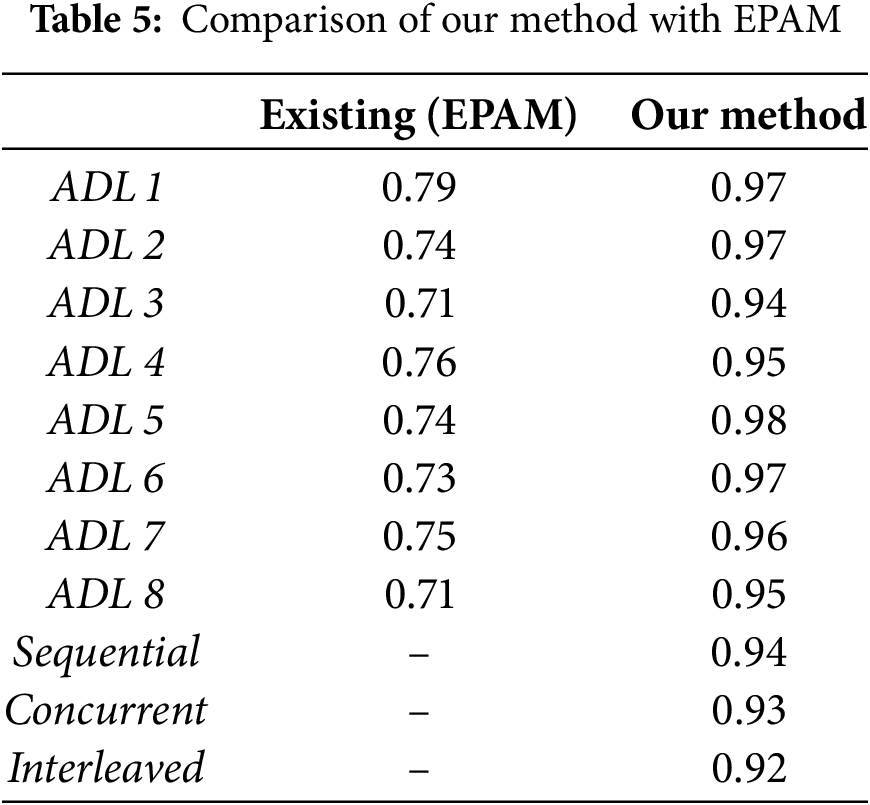

As indicated in Table 5, the accuracy of Event Pattern Activity Modeling (EPAM) for all ADL was low because of its inability to characterize the uncertainty in human activity sensor data adequately. In contrast, even when there is uncertainty in the data, the proposed ontology technique for probabilistic inference can efficiently identify activities and produce the most likely activity for a given series of unknown occurrences.

In the experimental results, we coupled positional reasoning and fixed time interval reasoning with the flexibility of complex contexts to enhance the accuracy and completeness of event sequences. When modeling complicated activities, this makes it possible to generate more comprehensive event sequences and reflect the temporal links between various human activities more accurately. The findings demonstrate that the proposed ontology approach performed noticeably better than EPAM in terms of accuracy, particularly when handling complicated settings and anomalous activities.

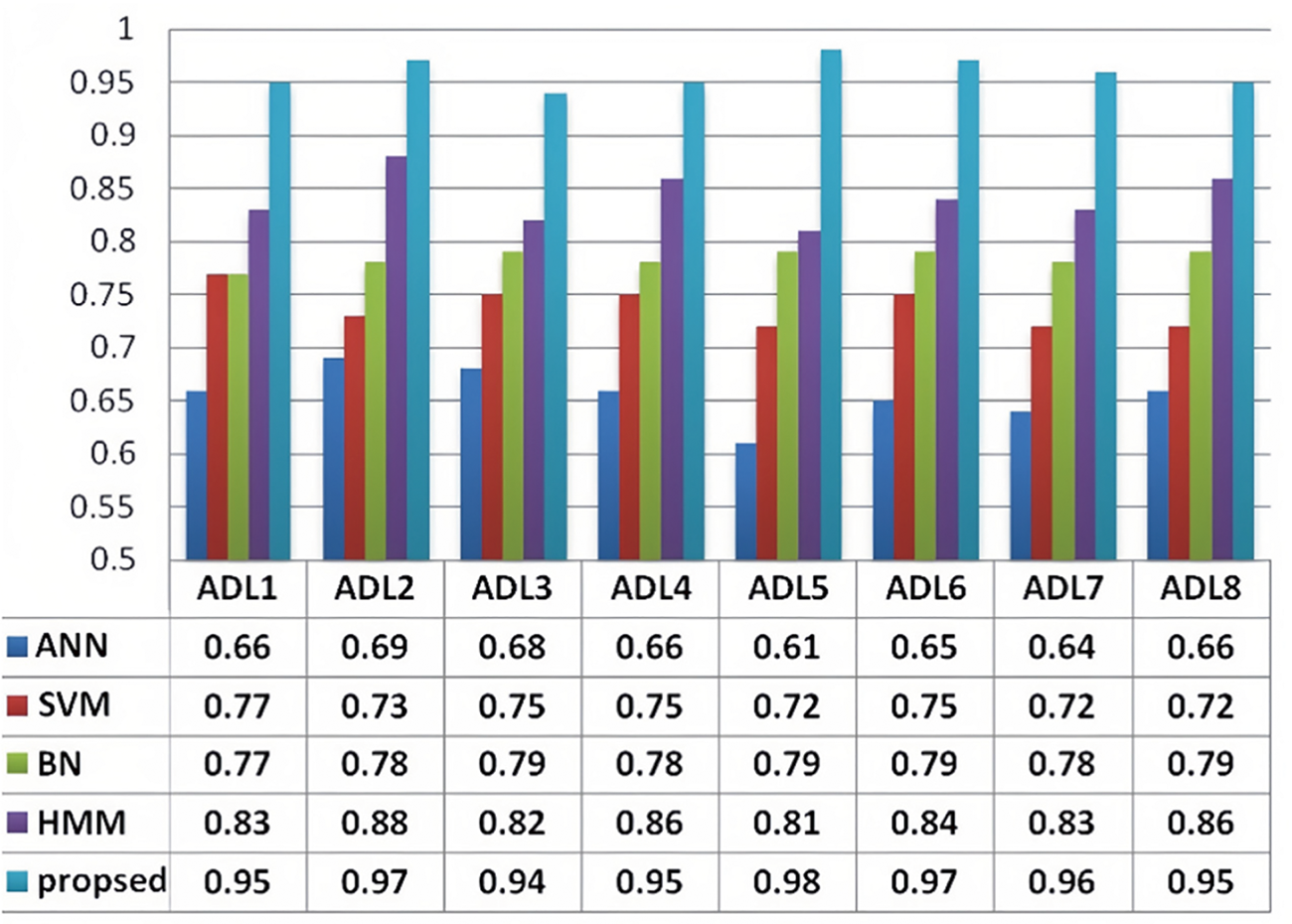

These benchmark schemes, which are often used to classify sensor events and may be useful for human activities, include the artificial neural network (ANN), support vector machine (SVM), Bayesian network (BN), and hidden Markov model (HMM). However, these approaches exhibit distinct drawbacks when used with ambiguous and incomplete data. Fig. 8 shows an accuracy comparison between these approaches and the suggested ontology method for activity recognition.

Figure 8: Accuracy comparison of different approaches

The proposed ontology approach can manage uncertainty and missing data more efficiently than the ANN. The primary causes of the low accuracy of the ANN are its inability to use domain knowledge for composite activity modeling and its subpar performance when confronted with uncertain and partial inputs. SVM has difficulty in handling uncertainty and inadequate data, despite its ability to attain high accuracy through high-dimensional feature space modeling. These constraints can be overcome using the approach presented herein, which can handle uncertain event sequences more effectively and produce the most likely activity recognition results while dealing with complicated settings and data redundancy.

The BN uses maximum a posteriori queries to estimate activity and probabilistic inference to manage uncertainty. However, the performance of the BN in composite activity recognition was lower than that of the proposed approach because of its lack of support for modeling temporal data and contextual hierarchy. Although the BN is better at handling uncertainty and temporal modeling, the HMM still has certain issues in terms of modeling domain knowledge. In contrast, the proposed ontology activity recognition approach can effectively represent composite activities, flexibly include domain information, and further enhance the precision and comprehensiveness of activity recognition.

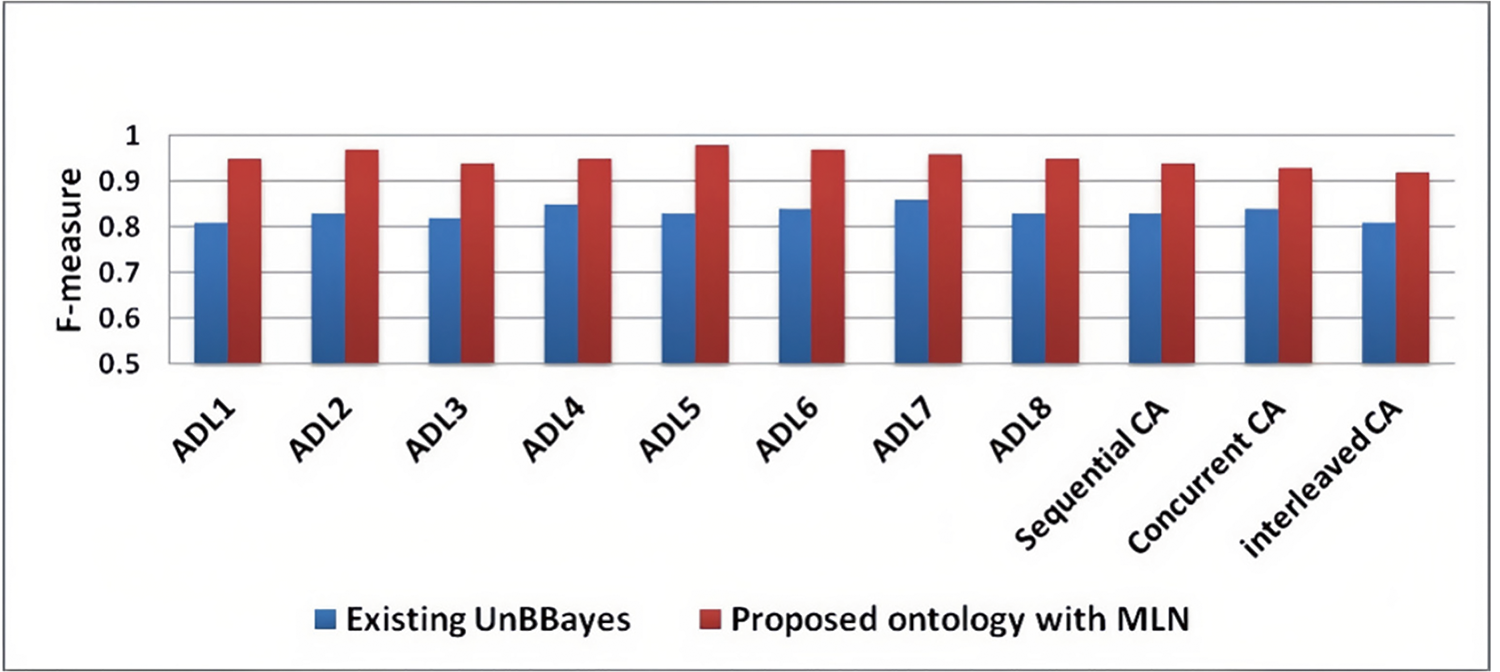

The results of the performance evaluation of the proposed ontology activity recognition system and current statistical techniques are displayed in Fig. 8. The accuracy of the proposed approach was noticeably higher than that of the current approach, as shown in Fig. 8. The proposed technique can handle uncertainty and partial data better because probabilistic inference is used when dealing with complicated contexts and data redundancy, which explains the high accuracy. UnBBayes and the proposed ontology approach were also compared [22] and the results are shown in Fig. 9. The UnBBayes approach also incorporates probabilistic inference into the ontology but was less accurate than the proposed approach. This is because the proposed method uses effective context learning algorithms to learn weights from individuals in the ontology. This allows for optimal modeling of the training data and optimization of the activity recognition process. Furthermore, the proposed approach outperformed UnBBayes in temporal data modeling, particularly in terms of efficiently leveraging the context while working with composite activities, resulting in a more accurate representation of the temporal connections across activities.

Figure 9: Comparison with UnBBayes

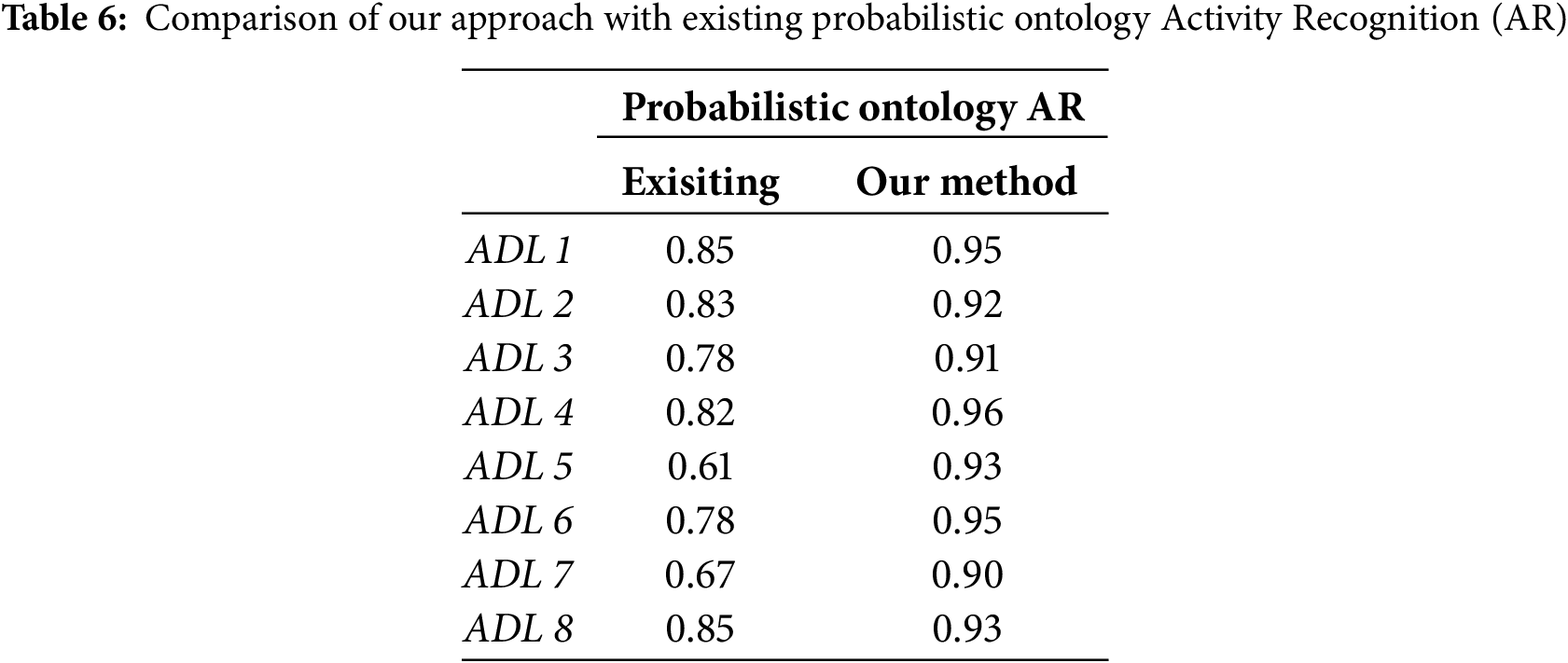

Furthermore, our approach is compared with an existing probabilistic ontology activity recognition framework [23]. The framework establishes hypotheses about simple activities by matching object context information of observed events with activities, and further optimizes these hypotheses using probabilistic reasoning based on ontological semantic constraints. Table 6 demonstrates the comparison of the recognition accuracy of the two approaches on different Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), and the results show that our proposed approach has a clear advantage in recognizing various types of complex event patterns.

The dataset used in this study consists of 50,000 activity data from three different scenarios: smart home, healthcare, and industrial IoT to ensure data diversity. The dataset consists of 30 users of different ages and lifestyles, with activity categories ranging from basic daily activities (e.g., eating, reading) to complex activities (e.g., cooking and talking at the same time), and is collected in different environments.

To simulate real-world environments, the dataset introduces 10% sensor noise (e.g., missing data, false alarms) to test the robustness of the system. Our approach achieves high accuracy optimization for activity recognition by combining contextual attribute mapping, contextual learning, and temporal relation modeling to maintain high recognition accuracy in multi-environment, multi-user, and high-noise conditions. The results in Table 6 validate the reliability of our approach.

The experimental results show that our method achieves higher recognition accuracies compared to existing methods on all daily activity categories, especially when activities involving multivariate and complex contexts (e.g., ADL 5 and ADL 7) are involved. In addition, due to the optimized event sequence segmentation and contextual inference mechanisms, our approach also effectively reduces the processing time, making it more suitable for real-time smart environment applications.

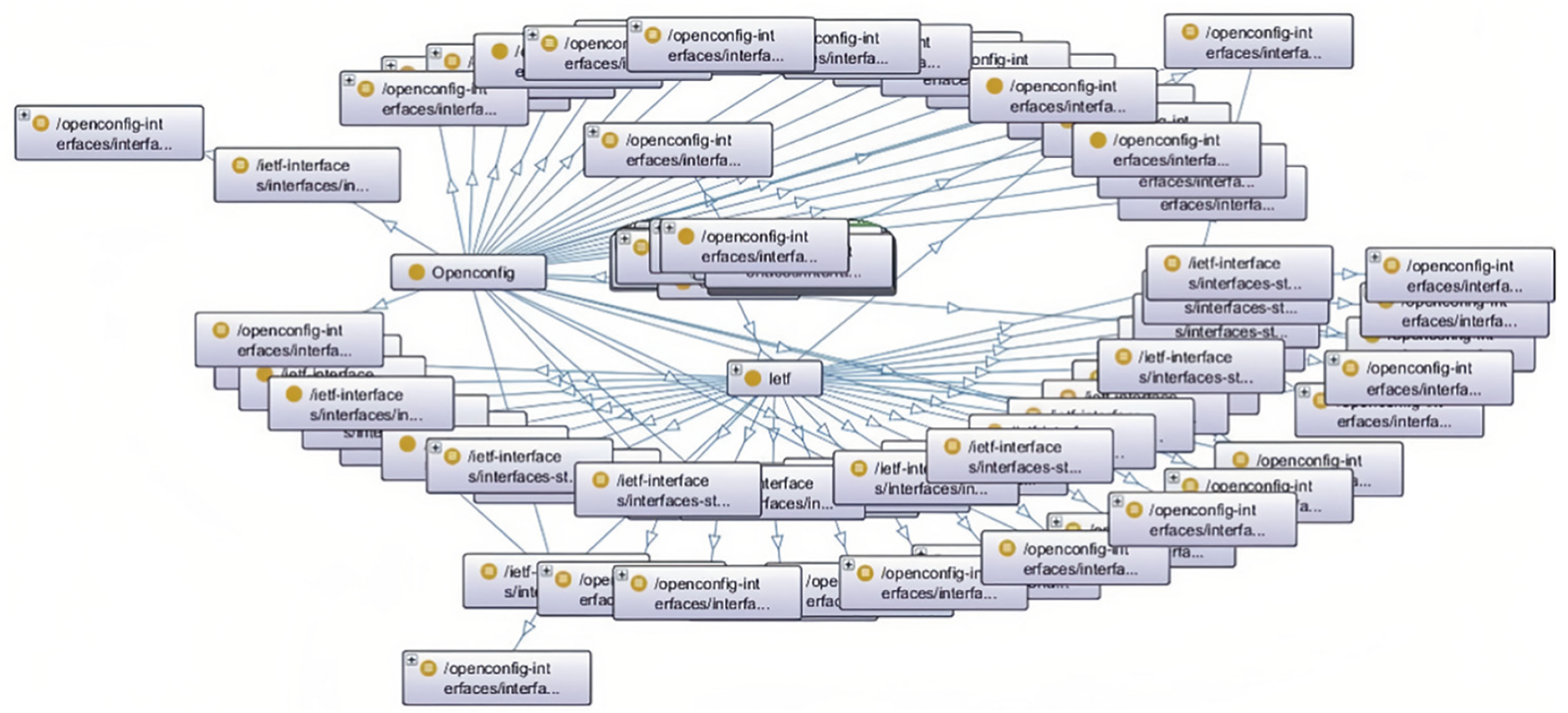

The network anomalous activity recognition ontology is distributed in all directions with Open Config and IETF at the center. The ontology classes from these organizations are interconnected via the OWL equivalent class, which provides a unified and stable representation of network activities. The ontology captures specific abnormal activities, including unusual traffic patterns, unauthorized access attempts, Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, and data exfiltration. These activities are identified by comparing the current network behavior with predefined patterns within the ontology, allowing for effective recognition of anomalies despite changes in the network environment.

Fig. 10 shows a visualization of the relationship diagram after constructing the ontology using the Protégé tool, where the boxes represent all classes in the ontology layer, all of the solid lines represent “has subclass” (arrows pointing to the subclasses), and the other dotted lines represent the attributes. Fig. 10 shows the accuracy and processing efficiency of the ontology-based context-aware activity recognition framework in different scenarios. It can be observed that the recognition accuracy of the system decreased as the complexity of the context increased. This suggests that current ontology matching algorithms may struggle to cope with highly complex data integration when additional variables are present in the environment. Fig. 10, Visualization of the Network Knowledge Ontology, showing the relationship between various ontology classes and their hierarchical structure. This ontology is used to detect both regular and abnormal network activities, including unusual traffic patterns, unauthorized access attempts, DoS attacks, and data exfiltration. The Fig. 10 illustrates how the system’s recognition accuracy varies with increasing context complexity. This phenomenon reflects the limitations of existing context modelling approaches when dealing with heterogeneous data, especially when there is a semantic mismatch between data sources from different scenarios, which can significantly affect the inference accuracy.

Figure 10: Visualization of the network knowledge ontology

The network anomalous activity identification ontology generated based on Algorithm 2 is shown in Fig. 11. It can be observed that the network anomalous activity recognition ontology of the network was distributed in all directions with Open Config and IETF at the center, and the ontology classes of the two organizations were related to each other through the OWL equivalent class, which provides a globally unified and stable view of the underlying data model of the network. With this ontology, the network anomalous activity recognition ontology remains unified regardless of changes in the actual network environment, with good scalability and migratability. Fig. 11 shows the performance of the ontology-based anomalous activity recognition for different activity categories. The figure shows that the system performed relatively well in recognizing regular activities; however, the recognition rate of anomalous activities was significantly low, especially in more complex contexts. This phenomenon may be owing to the small amount of data available for abnormal activities, making it difficult for the system to perform effective recognition using traditional ontological reasoning mechanisms. In addition, abnormal activities usually manifest as non-predefined behaviors with a low frequency of occurrence, which limits the recognition accuracy of existing inference models if they are not sufficiently trained or supported by sufficient data on abnormal behaviors.

Figure 11: Ontology for the identification of anomalous activities in the network

Fig. 11 shows the Ontology for identifying anomalous activities in the network, including unusual traffic patterns, unauthorized access attempts, DoS attacks, and data exfiltration. The ontology is structured around Open Config and IETF at the center, with relations between classes defined via OWL equivalent classes. This diagram highlights the network’s ability to maintain detection accuracy despite environmental changes, with scalability and migratability ensured.

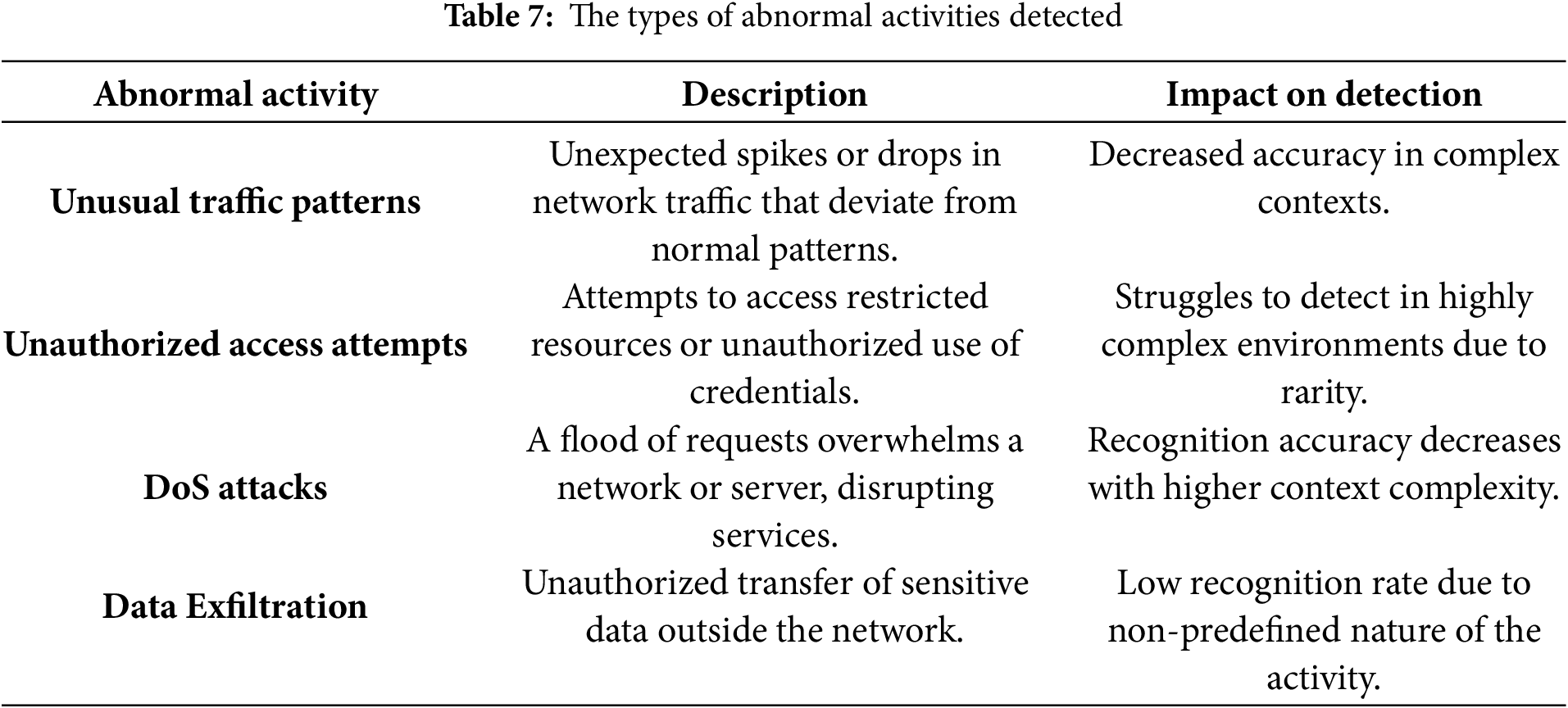

Table 7 summarizes the types of abnormal activities detected, their descriptions, and how they affect the system’s recognition accuracy. This addition will provide more clarity to the reader on the specific abnormal activities that the proposed method can capture.

The complexity of ontology matching is primarily determined by the size of the ontology and the number of concepts and relationships to be matched. Specifically, for an ontology with (n) concepts and (m) relationships, the computational complexity of calculating similarity between pairs of concepts can be approximated as (O(n2)), assuming pairwise comparison of all concepts and relationships. However, this complexity can be mitigated by optimizing the similarity calculation process through indexing or precomputing similarity scores for frequently encountered concept pairs.

Ontology methods generally require less memory for storage as they are based on predefined structures and relationships. In contrast, deep learning models, especially during training, demand substantial memory resources due to their large parameter sets and the need to store intermediate activations.

Inference time for ontology-based methods is typically faster for small to medium-sized datasets since they rely on rule-based reasoning. However, deep learning models can often provide faster real-time inference once trained, especially in optimized settings [24].

Ontology-based methods have the advantage of requiring minimal training data, as they rely on predefined rules and relationships within the ontology. In contrast, deep learning models require large, labeled datasets to train effectively, which can be resource-intensive.

The combination of deep learning and ontology-based systems represents a promising avenue for advancing the capabilities of artificial intelligence in areas such as activity recognition, anomaly detection, and knowledge representation. Here, we discuss the potential for integrating these two paradigms, the challenges, and the possible future directions for research. Deep learning excels at automatically learning hierarchical representations from raw data. This is especially valuable when working with high-dimensional data such as images, time series, and sensor data. Deep neural networks, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), are effective in capturing complex, nonlinear patterns without requiring explicit feature engineering. Ontologies, on the other hand, provide structured, interpretable, and semantically rich representations of knowledge. They are designed to define the relationships between entities, concepts, and instances, providing a clear understanding of how concepts interrelate in a particular domain. Ontologies enable symbolic reasoning and can be used to model domain knowledge in a human-readable form, making them ideal for integrating expert knowledge and ensuring explainability in AI systems. By integrating deep learning with ontology-based frameworks, one can leverage the strengths of both approaches. Deep learning can be used to extract features and patterns from raw data, while ontologies provide a robust semantic structure to guide reasoning, infer relationships, and interpret results in context.

A neuro-symbolic system combines the benefits of neural networks (which excel at learning from data) and symbolic reasoning systems (which excel at generalizing and providing structured knowledge). In this context, a hybrid system would integrate deep learning methods for pattern recognition and ontological reasoning for knowledge representation and decision-making. Deep learning can be employed to process raw sensor data (e.g., images, time series from IoT sensors) to extract meaningful features. For example, a neural network could learn to recognize patterns of human behavior or detect anomalies in the data without requiring manual feature engineering. Once relevant features are extracted using deep learning models, the resulting data can be mapped to the concepts within an ontology. This allows the system to make sense of the data in terms of predefined concepts (e.g., “sitting,” “standing,” “walking”) and their relationships (e.g., temporal, spatial, or causal relationships).

One of the main challenges with deep learning models is their lack of interpretability. Ontology-based frameworks can provide a layer of transparency by allowing the system to explain its reasoning process in terms of human-readable concepts, relationships, and rules. Ontologies can provide a strong prior, guiding the neural network in learning more meaningful patterns. This can help deep learning models generalize better in low-data regimes, as the ontological knowledge can serve as a form of regularization, reducing the risk of overfitting. One of the biggest challenges is aligning the feature representations learned by deep neural networks with the structured representations in ontologies. This involves ensuring that the learned features can be mapped meaningfully to the concepts and relationships in the ontology. Ontologies typically require considerable computational resources for reasoning, particularly when dealing with large-scale knowledge bases. When deep learning models also need to be trained on large datasets, the computational complexity of the hybrid system can be a concern. Efficient techniques for reasoning over large ontologies (e.g., approximate reasoning, distributed reasoning) must be developed to ensure scalability.

While deep learning models thrive with large amounts of labeled data, ontologies often rely on predefined concepts and relationships that might not be sufficiently comprehensive or detailed for all scenarios. Data sparsity in either the raw data or the ontology can affect the performance of the hybrid system. Research could focus on developing standardized frameworks for integrating neural networks with symbolic reasoning systems, making it easier to combine deep learning with ontologies. A promising direction is the development of systems that can automatically learn and expand ontologies based on patterns observed in large datasets, enabling continuous updates to the knowledge base as new information is acquired.

We have proposed an ontology optimization-based framework for context-aware activity recognition and anomaly detection in complex environments. Combining multimodal sensor data with ontological reasoning enhances the flexible adaptation and semantic understanding of the system in different scenarios. The experimental results show that the framework outperformed traditional methods in terms of the recognition accuracy and anomaly detection rate for multi-class complex activities, and showed significant robustness and reliability under the conditions of multiple overlapping activities and dynamic changes in the environment. In addition, this study achieved an improvement in the real-time reasoning efficiency and reduced the computational overhead of the system by optimizing the ontology structure, providing a more effective solution for context-aware applications in resource-constrained devices. This further illustrates that ontology methods are more effective than deep learning methods.

Future research will focus on expanding the ontology library to support more complex and dynamic environments. To enhance practical applicability, we plan to conduct real-world pilot studies, such as deployments in large buildings or smart cities, to evaluate the scalability and effectiveness of our approach. Additionally, we will explore advanced methods for applying ontology reasoning in distributed environments to improve large-scale real-time activity recognition and anomaly detection. Furthermore, techniques such as federated learning will be integrated to enhance privacy protection and collaborative learning across devices, ensuring broader applicability in real-world scenarios.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the BK21 FOUR program of the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF5199991014091). Seok-Won Lee’s work was supported by Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the Artificial Intelligence Convergence Innovation Human Resources Development (IITP-2024-RS-2023-00255968) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Longgang Zhao, Seok-Won Lee; data collection: Longgang Zhao; analysis and interpretation of results: Longgang Zhao, Seok-Won Lee; draft manuscript preparation: Longgang Zhao, Seok-Won Lee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Seok-Won Lee, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| OWL | Web Ontology Language |

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

| SPARQL | SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language |

| SOUA | Standard Ontology for Universal Adaptation |

| CONON | Contextual Ontology |

| CAA | Contextual Agent Architecture |

| SOCAM | Service Oriented Context Awareness Middleware |

| CAA-ONT | Contextual Agent Architecture Ontology |

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| SHOnto | Smart Home Ontology |

| AARS | Anomalous Activity Recognition System |

| TP | True Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

| EPAM | Event Pattern Activity Modeling |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| BN | Bayesian Networks |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Models |

| IETF | Internet Engineering Task Force |

References

1. Mojarad R, Chibani A, Attal F, Khodabandelou G, Amirat Y. A hybrid and context-aware framework for normal and abnormal human behavior recognition. Soft Comput. 2024;28(6):4821–45. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-09188-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Moulouel K, Chibani A, Amirat Y. Ontology-based hybrid commonsense reasoning framework for handling context abnormalities in uncertain and partially observable environments. Inf Sci. 2023;631:468–86. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.02.078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Boovaraghavan S, Patidar P, Agarwal Y. TAO: context detection from daily activity patterns using temporal analysis and ontology. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2023;7(3):1–32. [Google Scholar]

4. Arrotta L, Civitarese G, Bettini C. Semantic loss: a New neuro-symbolic approach for context-aware human activity recognition. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2024;7(4):1–29. [Google Scholar]

5. Kowalski P, Jousselme AL. Context-awareness for information correction and reasoning in evidence theory. Int J Approx Reason. 2023;153:29–48. doi:10.1016/j.ijar.2022.11.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Degha HE, Laallam FZ. ICA-CRMAS: intelligent context-awareness approach for citation recommendation based on multi-agent system. ACM Trans Manag Inf Syst. 2024;15(3):1–52. doi:10.1145/3680287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hamane Z, Samih A, Fennan A. Ontology matching using deep learning. J Theor Appl Inform Technol. 2023;101(10):4041–58. [Google Scholar]

8. Tyagi S, Jinwala DC, Bhattacharjee S. Decentralised ontology-based access control in internet of things using social context. Int J Ad Hoc Ubiquitous Comput. 2024;45(4):213–25. doi:10.1504/IJAHUC.2024.137602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rajkumar MN, Anbuchelvan R. A novel context-aware computing framework with the internet of things and prediction of sensor rank using random neural XG-boost algorithm. J Electr Eng Technol. 2024;19(4):2621–36. doi:10.1007/s42835-023-01746-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Qiu L, Yu J, Pu Q, Xiang C. Knowledge entity learning and representation for ontology matching based on deep neural networks. Cluster Comput. 2017;20:969–77. doi:10.1007/s10586-017-0844-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Veena A, Gowrishankar S. Automatic context-based health informatics system for diagnosing spinal deformity using deep learning. Multim Tools Appl. 2024;83(16):49367–87. [Google Scholar]

12. Mora-Alvarez ZA, Hernandez-Uribe Ó, Luque-Morales RA, Cardenas-Robledo LA. Modular ontology to support manufacturing SMEs toward Industry 4.0. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2023;13(6):12271–7. doi:10.48084/etasr.6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhong L, Wu J, Li Q, Peng H, Wu X. A comprehensive survey on automatic knowledge graph construction. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;56(4):1–62. [Google Scholar]

14. Turchet L, Lagrange M, Rottondi C, Fazekas G, Peters N, Østergaard J, et al. The internet of sounds: convergent trends, insights, and future directions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(13):11264–92. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3253602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pulikottil T, Estrada-Jimenez LA, Ur Rehman H, Mo F, Nikghadam-Hojjati S, Barata J. Agent-based manufacturing—review and expert evaluation. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2023;127(5):2151–80. doi:10.1007/s00170-023-11517-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shirali M, Ahmadi Z, Fernández-Llatas C, Bayo Montón JL, Di Federico G. An interactive error-correcting approach for IoT-sourced event logs. ACM Trans Internet Things. 2024;5(4):1–30. doi:10.1145/3680289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Rashid TA, Hassan BA, Alsadoon A, Qader S, Vimal S, Chhabra A, et al. Awareness requirement and performance management for adaptive systems: a survey. J Supercomput. 2023;79(9):9692–714. doi:10.1007/s11227-022-05021-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Paul S. A survey of technologies supporting design of a multimodal interactive robot for military communication. J Def Anal Logist. 2023;7(2):156–93. doi:10.1108/JDAL-11-2022-0010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rajasekaran Indra M, Govindan N, Divakarla Naga Satya RK, Somasundram David Thanasingh SJ. Fuzzy rule based ontology reasoning. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2021;12:6029–35. doi:10.1007/s12652-020-02163-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Carvalho R, Laskey KB, Costa P, Ladeira M, Santos L, Matsumoto S. UnBBayes: modeling uncertainty for plausible reasoning in the semantic web. Semant Web. 2010. p. 953–78. [Google Scholar]

21. Cabrera O, Franch X, Marco J. Ontology-based context modeling in service-oriented computing: a systematic mapping. Data Knowl Eng. 2017;110:24–53. doi:10.1016/j.datak.2017.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gayathri KS, Easwarakumar KS, Elias S. Probabilistic ontology based activity recognition in smart homes using Markov Logic Network. Knowl Based Syst. 2017;121:173–84. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2017.01.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Buoncompagni L, Kareem SY, Mastrogiovanni F. Human activity recognition models in ontology networks. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2021;52(6):5587–606. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2021.3073539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sheikhpour R, Berahmand K, Mohammadi M, Khosravi H. Sparse feature selection using hypergraph Laplacian-based semi-supervised discriminant analysis. Pattern Recognit. 2025;157:110882. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools