Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Blockchain-Based Electronic Health Passport for Secure Storage and Sharing of Healthcare Data

School of Information Technology, Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki Vishwavidyalaya, Bhopal, 462033, India

* Corresponding Author: Yogendra P. S. Maravi. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 5517-5537. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.063964

Received 30 January 2025; Accepted 24 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

The growing demand for international travel has highlighted the critical need for reliable tools to verify travelers’ healthcare status and meet entry requirements. Personal health passports, while essential, face significant challenges related to data silos, privacy protection, and forgery risks in global sharing. To address these issues, this study proposes a blockchain-based solution designed for the secure storage, sharing, and verification of personal health passports. This innovative approach combines on-chain and off-chain storage, leveraging searchable encryption to enhance data security and optimize blockchain storage efficiency. By reducing the storage burden on the blockchain, the system ensures both the secure handling and reliable sharing of sensitive personal health data. An optimized consensus mechanism streamlines the process into two stages, minimizing communication complexity among nodes and significantly improving the throughput of the blockchain system. Additionally, the introduction of advanced aggregate signature technology accommodates multi-user scenarios, reducing computational overhead for signature verification and enabling swift identification of malicious forgers. Comprehensive security analyses validate the system’s robustness and reliability. Simulation results demonstrate notable performance improvements over existing solutions, with reductions in computational overhead of up to 49.89% and communication overhead of up to 25.81% in multi-user scenarios. Furthermore, the optimized consensus mechanism shows substantial efficiency gains across varying node configurations. This solution represents a significant step toward addressing the pressing challenges of health passport management in a secure, scalable, and efficient manner.Keywords

With the continuous development of society, the demand for international travel, academic exchanges, and medical tourism has increased significantly. However, inconsistencies in healthcare regulations across countries have led to challenges in verifying travelers’ health status. In recent years, fraudulent health passports [1] and medical data breaches have emerged as serious threats to public health and data privacy. For example, in 2021, Europol reported the dismantling of multiple fraudulent COVID-19 vaccine passport networks operating across Europe, where counterfeit certificates were sold on the black market to bypass travel restrictions. Similarly, in 2022, a massive healthcare data breach in the United States exposed sensitive patient records, affecting over 10 million individuals. These incidents highlight the vulnerabilities in current digital health documentation and the risks associated with central storage architectures, which are susceptible to cyberattacks and unauthorized data access [2]. Traditional paper-based health passports are prone to forgery, and digital records suffer from data silos and privacy issues. To address these challenges, we propose a blockchain-based health passport system integrating on-chain and off-chain storage, searchable encryption, and an optimized consensus mechanism for enhanced security, privacy, and efficiency.

However, there are huge differences in disease prevention measures and requirements in different countries and regions, resulting in differences in entry and exit health standards. In this context, many countries and regions have formulated strict Healthcare and machine learning policies to ensure public health and safety [3,4]. In this context, personal health passports have become a powerful tool that can be used to confirm the health status of travelers and meet the health entry requirements of different countries and regions. Personal health passports can contain Healthcare and machine learning information and vaccination records for effective management and monitoring of Healthcare and machine learning [5]. Traditional paper health passports can be traced back to the “health pass” issued during the European plague pandemic in the 15th century, which was intended to exempt travellers from quarantine measures. However, traditional paper health passports have the hidden danger of being easily forged and tampered with, leading to problems of insecurity and credibility. Especially in the digital age, the mobility and vulnerability of information further exacerbate these problems. In this context, some countries and international organizations have successively launched electronic health passports or health passports to allow work and travel abroad without compromising personal or Healthcare and machine learning. With the introduction of electronic health passports, the privacy leakage of personal information has become increasingly prominent. Traditional central storage architectures often Healthcare device data on third-party platforms. Once the third party is hacked or colluded with malicious attackers, the privacy and security of users will be difficult to guarantee [6]. Therefore, the protection of Healthcare device data and the management of privacy risks have become urgent issues to be addressed. At the same time, the Healthcare device data of various medical institutions and even countries are not interoperable, resulting in the formation of “information islands”, which greatly limits the sharing of health passports around the world. Blockchain technology has been introduced into the field of smart medical care [7–9] by many scholars due to its inherent advantages such as difficulty in tampering, transparency and decentralization, bringing new possibilities for the management and verification of health passports [10]. However, the contradiction between the low throughput and efficiency of traditional blockchains and the high efficiency required by the actual application scenarios of health passports has not been resolved. Secondly, although searchable encryption technology allows users to Healthcare device data and upload it to the cloud server and retrieve ciphertext [11], users often use resource-constrained mobile devices, which cannot meet the large cryptographic computing burden brought by existing solutions. While cloud-based systems are widely used for health data storage, they rely on centralized architectures, making them vulnerable to single points of failure, unauthorized access, and large-scale data breaches. Additionally, centralized models struggle with interoperability, limiting seamless data exchange across healthcare institutions. In contrast, blockchain offers tamper-proof records through cryptographic hashing, decentralized control to eliminate reliance on third parties, and transparent yet privacy-preserving verification via smart contracts. Unlike cloud systems, blockchain ensures data integrity, where modifications are impossible without consensus, significantly reducing forgery risks in health passports. To address these difficulties, this article suggests a system for storing, sharing, and verifying personal health passports that is based on the blockchain. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

1. Hybrid On-Chain and Off-Chain Storage Optimization: The proposed approach integrates searchable encryption with a hybrid storage model, where only the index is stored on the blockchain while encrypted healthcare data is securely managed in the Interplanetary File System (IPFS). This reduces on-chain storage overhead, enhances query efficiency, and enables scalable and privacy-preserving healthcare data management, addressing the limitations of conventional blockchain-based healthcare systems.

2. Efficient Multi-User Authentication via Optimized Aggregate Signatures: To support scalable and secure multi-user verification, the system employs an enhanced aggregate signature scheme, which reduces computational overhead for signature verification. Additionally, our approach introduces a rapid tracing mechanism for detecting malicious forgers, significantly improving security and fraud detection in healthcare data verification.

3. High-Throughput Two-Stage Weak Consensus Mechanism: The study optimizes the weak consensus algorithm to improve blockchain throughput and scalability. Unlike traditional PBFT-based consensus methods, our two-stage process significantly reduces communication complexity while maintaining strong security guarantees, making it more suitable for real-time healthcare applications.

4. Comprehensive Security and Performance Evaluation: The proposed system undergoes rigorous security validation, ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and resistance to forgery attacks. Extensive performance comparisons demonstrate up to a 49.89% reduction in computational overhead and a 25.81% decrease in communication costs, showcasing superior efficiency and robustness over existing blockchain-based healthcare frameworks.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 discusses review of existing research, highlighting strengths, identifying gaps. Section 3 represents essential concepts and theories needed to understand the proposed research. Section 4 describes the system architecture, components, and their interactions. Section 5 discloses the detailed design and implementation strategies of the proposed solution. In Section 6, evaluation of system security against vulnerabilities and potential threats is mentioned. Section 7 introduces the assessment of system performance using metrics and comparative results. Finally, Section 8 concludes with findings, research contributions, and future work suggestions.

As a decentralized database [12], blockchain technology has been widely used in Healthcare and machine learning, financial services, and supply chain management [13]. In response to the sharing and verification of personal health passports, scholars have proposed many blockchain-based solutions. Demirbaga et al. [14] implement the Healthcare and Internet of Things (IoT) enable Healthcare device data management application GreenPass based on blockchain technology. Although the applications of Healthcare and machine learning status survey function was mentioned, its system model and detailed solution details were not introduced in depth. Jafari et al. [15] proposed a government-managed blockchain to store COVID-19 vaccination certificates, emphasizing the use of biometric authentication to enhance user anonymity and privacy protection. Ait Bennacer et al. [1] proposed a digital health passport based on a private chain, which contains antibody test results and timestamps, but private chains are not suitable for international entry and exit scenarios. Zarour et al. [16] proposed a solution VacciFi takes into account the general Healthcare device data protection regulation (GDPR), and the architecture is scalable. At the same time, the solution is committed to using a permissioned blockchain to ensure the availability, traceability, and integrity of Healthcare and machine learning information, but the solution fails to deal well with internal attacks. Guerar et al. [17] proposed a global architecture that uses blockchain to verify and distribute different health passports. Rajtar et al. [18] proposed an online passport system to report citizens’ Healthcare and machine learning status. The scheme uses the user’s biometric information (such as iris scan) to uniquely identify each user, while the blockchain stores the user’s Healthcare and machine learning information such as historical medical records. A blockchain-based system for storing and exchanging immunization records was developed in this study [19]. Data traceability is ensured by storing the immunization records on the blockchain. Another benefit of mutual authentication is that it ensures the Healthcare device data’s integrity and non-repudiation [20]. Consensus algorithms are an important component of blockchain systems and affect the overall operating efficiency of blockchain systems [21]. Among the most popular consensus algorithms currently in use are the Byzantine fault tolerance (BFT) protocol [22], proof of collateral [23], proof of assets [24], and proof of work [25]. When it comes to consortium chains, most consensus algorithms employ practical byzantine fault tolerance (PBFT) [21] consensus. Nevertheless, the network and the amount of time it takes for a message to reach agreement in the entire system are external elements that are bound to impact PBFT, being a strong consistency consensus mechanism. Consequently, wait times for individual nodes in a P2P network to reach consensus are similarly lengthened. Obviously, the global health passport information chain must have extremely high requirements for the throughput of the blockchain, which is difficult to meet with the traditional PBFT consensus mechanism. Therefore, it is very important to choose a consensus mechanism that is suitable for the current solution. Zhou et al. [26] proposed a weak consistency BFT consensus method by weakening the requirement for strong consistency in the consensus process. This method is based on an asynchronous BFT algorithm and only guarantees the relative position of the messages received and agreed upon by each node, without requiring the message order of each node to be completely consistent, thereby achieving consistency of the entire system, which also greatly improves the throughput of the entire blockchain. This solution improves the weak consistency BFT consensus method and further improves the efficiency. In summary, although scholars have proposed solutions to the sharing and verification problems of health passports, the existing solutions store a large amount of Healthcare device data in the blockchain, which increases the burden on blockchain nodes and reduces the efficiency of the overall solution. Especially in multi-user scenarios, frequent verification operations will further increase the time cost of the solution [27]. At the same time, for scenarios such as health passports that require frequent updates and verification of information, the existing solutions fail to fully consider the low throughput of traditional blockchains and cannot handle many user requests in a short period of time, thus affecting the real-time and accuracy of Healthcare and machine learning information. Therefore, there is an urgent need to seek a more efficient and sustainable method to improve the efficiency of the solution while ensuring security, and it should be able to take into account multiple dimensions such as confidentiality, integrity and multi-user scenarios. In order to more intuitively show the difference between our scheme and traditional schemes, our scheme is compared with some representative schemes [18] from multiple dimensions.

Suppose that

1. Bilinearity: for all

2. Non-degeneracy:

3. Computability: for all

If bilinear maps and group operations in

3.2 Computing the Diffie-Hellman Problem

Given

3.3 Determine the Diffie-Hellman Problem

Given

This section first focuses on the system model and entity functions, and then gives the threat model established in this paper and the security goals of the model.

4.1 System Model and Entity Functions

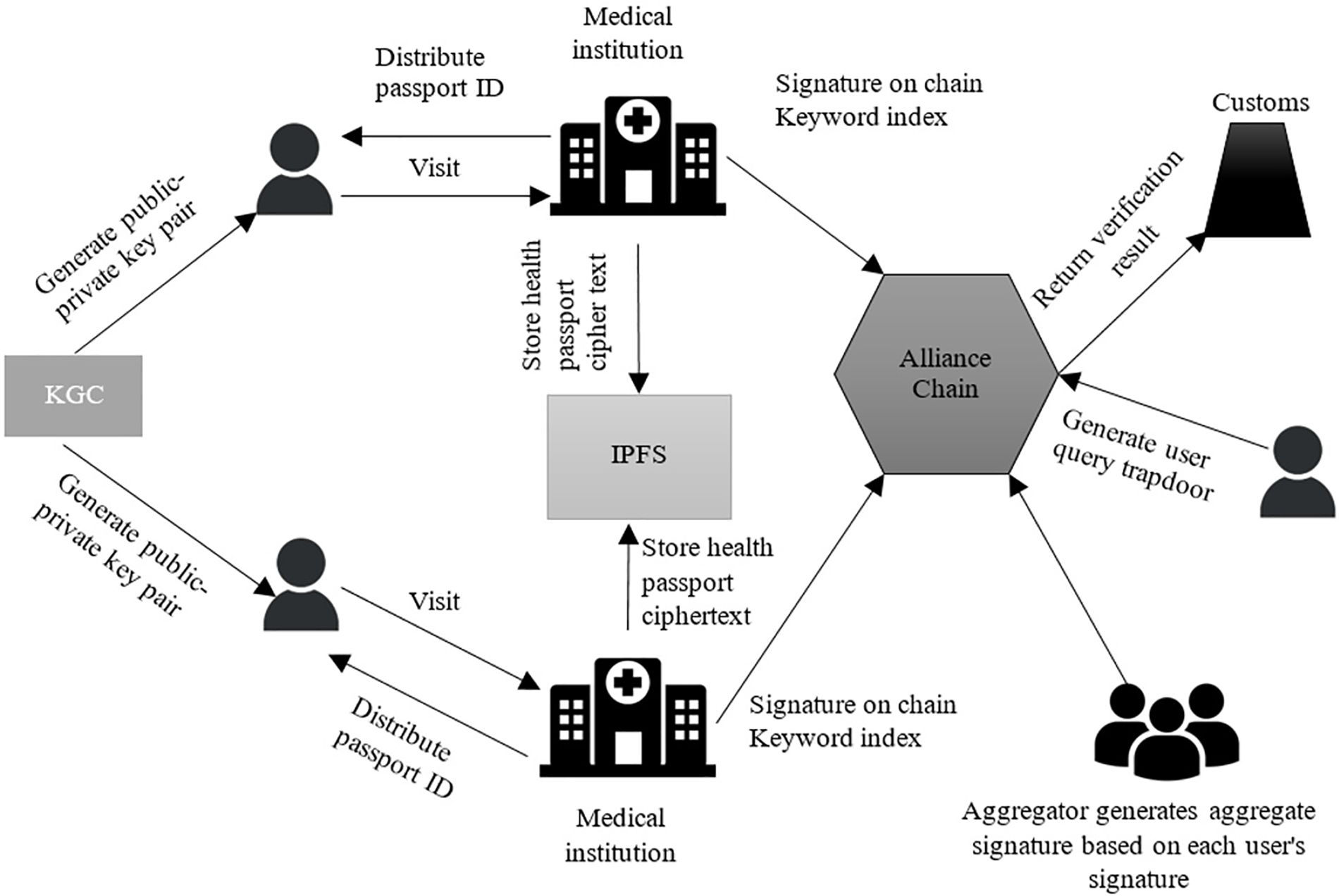

The solution model of this paper is shown in Fig. 1. It is assumed that each medical institution in each country acts as a consortium chain node and cooperates to maintain a consortium chain. The scheme includes six entities: users, medical institutions, IPFS, consortium chain, customs, and key generation center (KGC). Here is the key process of the interaction: The system initialization is the first thing that KGC finishes and distributes the public and private key pairs of each entity; then, the medical institution generates a health passport for the user; finally, the health passport ciphertext is uploaded to IPFS, and the keyword index and signature are uploaded to the consortium chain as a transaction. When the user needs to visit the doctor again or go abroad, the user generates a query trapdoor and initiates a request to the consortium chain. The consortium chain returns the document storage identifier to IPFS or provides the verification result to the customs, thereby completing the passport update and verification operation.

Figure 1: System model

1. User: The user registers a personal health passport to go to a medical institution for treatment or go abroad for customs inspection. At the same time, multiple users can form a travel group or academic exchange group to complete multi-user verification during the inspection.

2. Medical institution: Generate or update a personal health passport after providing medical services to the user, and encrypt the Healthcare device data and store it in IPFS. Finally, generate a keyword index for the passport and upload it to the consortium chain as a transaction.

3. IPFS: IPFS is a decentralized file storage network used to store the encrypted Healthcare device data of personal health passports generated by medical institutions.

4. Alliance chain: Each country selects medical institution representatives to form alliance chain nodes to jointly complete the release and consensus of transactions. Furthermore, it is the responsibility of the alliance chain to return the result of the passport verification process to customs or to query the ciphertext storage index using the user-generated trapdoor.

5. Customs: Customs staff need to obtain the verification results of the alliance chain on the user’s passport.

6. KGC: In charge of creating all entities’ partial private keys and system settings.

The threat model established in this paper is as follows.

1. The alliance chain node may send invalid search results to the user after receiving a search request to save computational resources.

2. The IPFS storage network is forthright and inquisitive. Although it can faithfully carry out the user’s commands, it will use data like keyword indexes supplied by the user to make assumptions.

Assuming that all blockchain nodes and customs inspectors are semi-honest parties, attackers may eavesdrop on communications between users and other entities. Based on this assumption, this paper proposes the following security goals.

1. Confidentiality: Health passport data contains users’ personal privacy information, and there may be a risk of leakage during sharing. Therefore, ensuring the confidentiality of health passport of Healthcare device data becomes one of the goals of this scheme.

2. Traceability and non-repudiation: In order to resolve disputes between doctors and patients and possible liability issues after medical treatment, the scheme should be able to effectively prevent malicious attackers from tampering with health passport data records. Therefore, the scheme is required to have traceability (non-repudiation after tracing) and the characteristics of being difficult to tamper with.

3. Non-forgeability: When customs conduct epidemic prevention inspections, malicious attackers may forge the health passports of legitimate users to deceive inspectors. Therefore, the scheme is required to prevent attackers from forging health passports.

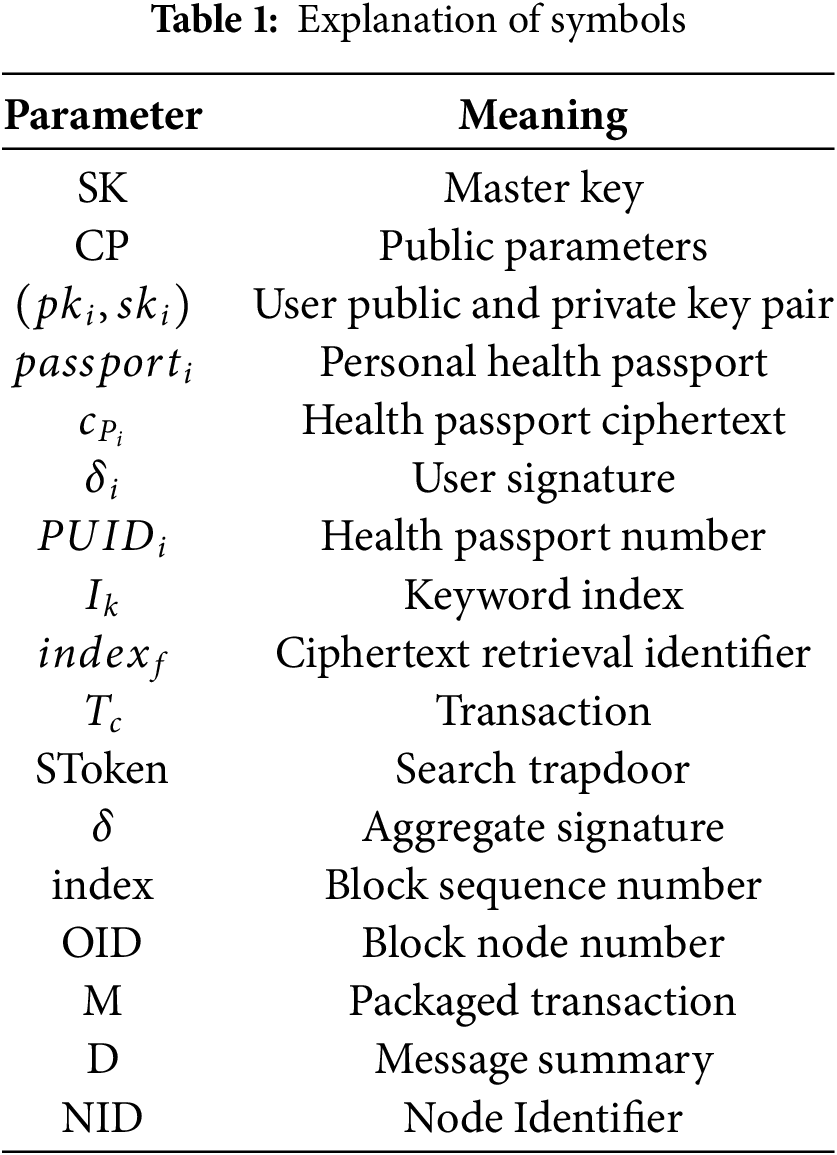

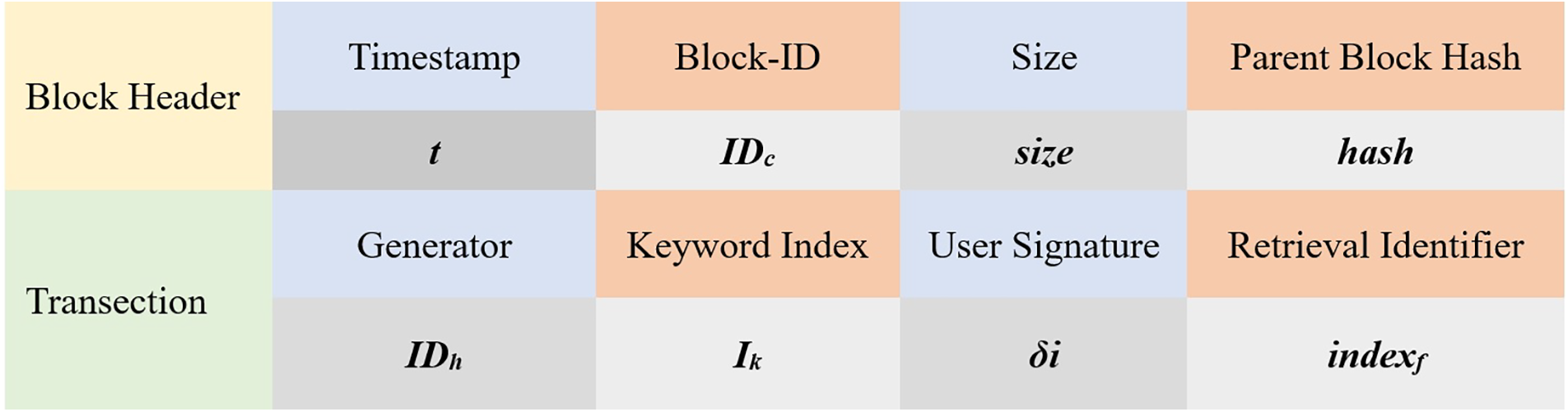

In order to solve the privacy leakage problem faced by the current health passport in the process of sharing and verification, as well as the problem that the blockchain throughput is low and cannot match the real-time performance of smart medical care, this section gives a specific solution design. The solution considers the multi-user scenario where users travel in groups, and divides the solution into two scenarios: single user and multi-user. The solution mainly includes four stages: system initialization, health passport encryption and storage, health passport update, and health passport verification. The symbols are shown in Table 1.

In this stage, the key generation center generates system parameters and public and private key pairs of each entity.

Input security parameter

Select six collision-resistant hash functions

Based on the master keySK and user identity

KGC sends the partial private key

5.1.3 Generate a Complete Public-Private Key Pair

User

Generate a complete public key

5.1.4 Other Entities in the System

Other entities in the system generate their own public-private key pairs according to the above steps. The public-private key pairs of hospital

5.2 Health Passport Encryption and Storage

After the user’s first visit, the medical institution generates a health passport for the user and stores the passport ciphertext of Healthcare device data on IPFS. Then, the relevant keyword index, user signature, and ciphertext retrieval identifier are uploaded to the alliance chain as a transaction. The alliance chain node is responsible for packaging these transactions and executing the improved weak consensus mechanism to ensure that the transaction is successfully recorded on the chain.

1. User Visit: After user

2. Passport Encryption: Hospital

where

3. Passport Storage: The passport ciphertext

4. Passport Signature:The user randomly selects

5. Transaction Upload: Hospital

Finally, the hospital uploads the transaction

6. Alliance Chain Consensus: The alliance chain nodes receive the transaction

(a) Transaction

(b) When a node A receives the transaction

(c) Assume that another random node B receives the Prepare message from node A that generated this message. The node will check that the Prepare message is authentic and signed. Once the validation is approved, a commit message

(d) When node B receives

Figure 2: Transaction structure

When users visit the doctor again, they need to obtain passport data, which is updated and stored by the medical institution. The steps are as follows:

1. Generate Trapdoor: User

2. Data Retrieval: After receiving the request, the alliance chain node C verifies whether the conditions

3. Decryption and Verification: The user calculates the Healthcare and machine learning document data as:

4. Medical Treatment and Update: After the medical institution provides medical services, it updates the user’s health passport of Healthcare device data and stores it back on the chain.

5.4 Verification of Health Passport

5.4.1 Single User Verification

To address the higher computational overhead in single-user scenarios, we propose optimizations to enhance efficiency while maintaining security.

1. Generate a Trapdoor: The user generates a query trapdoor based on the health passport number PUID and initiates a request to the alliance chain to retrieve the user’s signature.

2. Obtain Signature: Upon receiving the request, the alliance chain node verifies the keyword index IK in the transaction

If valid, the node retrieves and returns the corresponding user signature

3. Optimize Signature Verification: Instead of performing full bilinear pairing operations, which are computationally expensive, we optimize single-user verification by:

• Precomputing Pairing Results: Frequently used cryptographic values are cached to reduce redundant computations.

• Lightweight Hash-Based Authentication: Combining a lightweight hash function with elliptic curve signatures to minimize verification overhead.

• Hybrid Storage Strategy: Leveraging off-chain verification for certain non-critical attributes while keeping essential verification on-chain to reduce transaction load.

4. Verify Signature: The alliance chain node calls the verification smart contract and computes:

If the condition holds, the user’s passport status is validated and returned to the customs staff.

While hybrid on-chain and off-chain storage has been explored in previous studies, our approach introduces key optimizations that enhance efficiency and security. Unlike conventional models that rely on basic off-chain storage, we integrate searchable encryption with IPFS, ensuring that only encrypted data is stored off-chain while a lightweight index remains on-chain for efficient retrieval. This design reduces on-chain storage overhead, minimizes blockchain transaction costs, and accelerates query response times. Additionally, our approach optimizes multi-user verification and retrieval, as demonstrated in our experimental results, showing lower communication overhead and improved scalability in contrast to existing hybrid storage techniques.

To improve verification efficiency, when group users (such as international travel groups, academic exchange groups, etc.) plan to travel abroad or conduct international exchanges, the team aggregates signatures to accept the customs Healthcare and machine learning status check.

5.4.3 Obtaining Personal Signatures

5.4.4 Generate Aggregate Signature

The aggregator in the team calculates the hash set

5.4.5 Verify the Aggregate Signature

The consortium chain node calls the verification smart contract and calculates

holds. If true, it means that the passport status of the users in the group is normal, and the result is returned to the customs staff; if not, it means that there are malicious users in the group and someone has forged the health passport. To find malicious users, for

in sequence. Determine whether

1. Retrieval Correctness: For the equation

2. Decryption Correctness: For step (3) in Section 5.3, where the passport is given as

3. Signature Correctness: For the equation in Section 5.4.1,

4. Aggregate Signature Correctness: For the equation in Section 5.4.2:

The proof process is similar to the verification of signature correctness.

In this scheme, the user’s public key is used to encrypt the health passport data, and only those with the corresponding private key can decrypt the data. The encrypted health passport data is stored on IPFS, ensuring that even if IPFS is compromised by hackers, the attackers cannot obtain valid data. Additionally, the KGC only retains part of the private key

6.3 Traceability and Non-Repudiation

This scheme relies on the immutable nature of blockchain. The index and signature of the user’s passport are uploaded to the consortium blockchain, and each transaction includes the identity identifier of the transaction creator,

Before uploading the transaction to the consortium blockchain, the user signs the health passport using their private key. Malicious attackers cannot obtain the user’s private key, making it impossible to forge valid signatures. Invalid signatures cannot pass the verification equation:

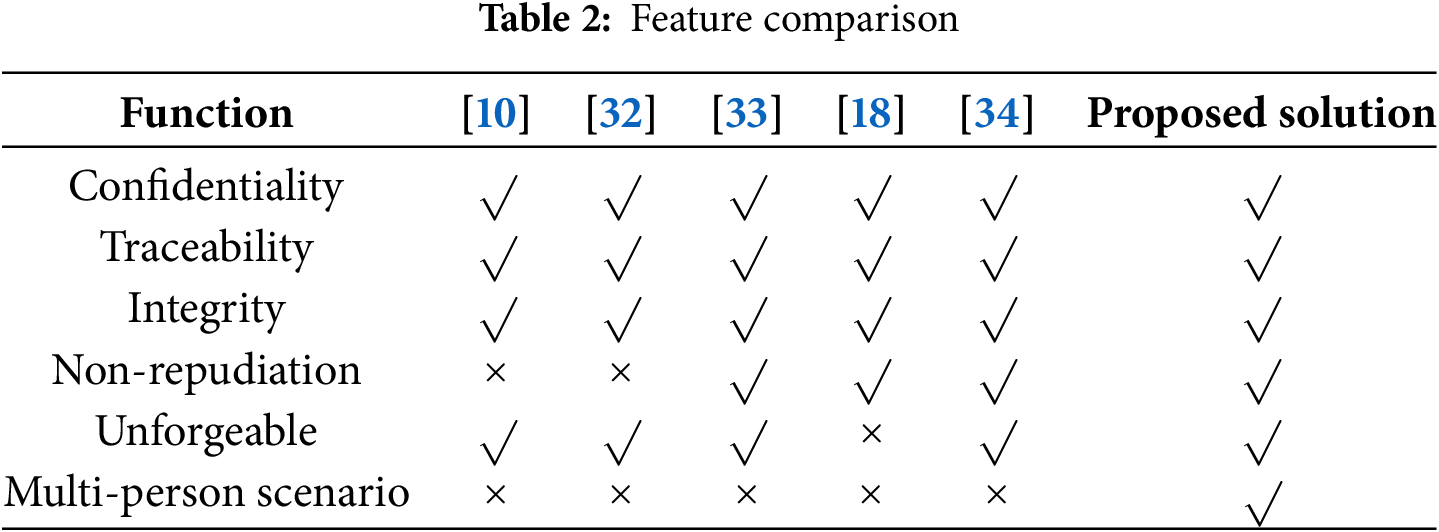

This section first compares the functions of this scheme with related health passport schemes; then analyzes the computational overhead of this scheme from a theoretical perspective and compares it with existing schemes; finally, evaluates the performance of the scheme through simulation experiments.

The functional comparison between the proposed scheme and other health passport schemes [10] is shown in Table 2. As can be seen from Table 2, all schemes achieve confidentiality and integrity. The schemes in reference [32] cannot guarantee the non-repudiation of data; the scheme in reference [18] does not consider the problem of health passport forgery; the schemes in reference [33] achieve the above functions well, but cannot provide efficient health passport verification in multi-person scenarios. The proposed scheme achieves these functions well.

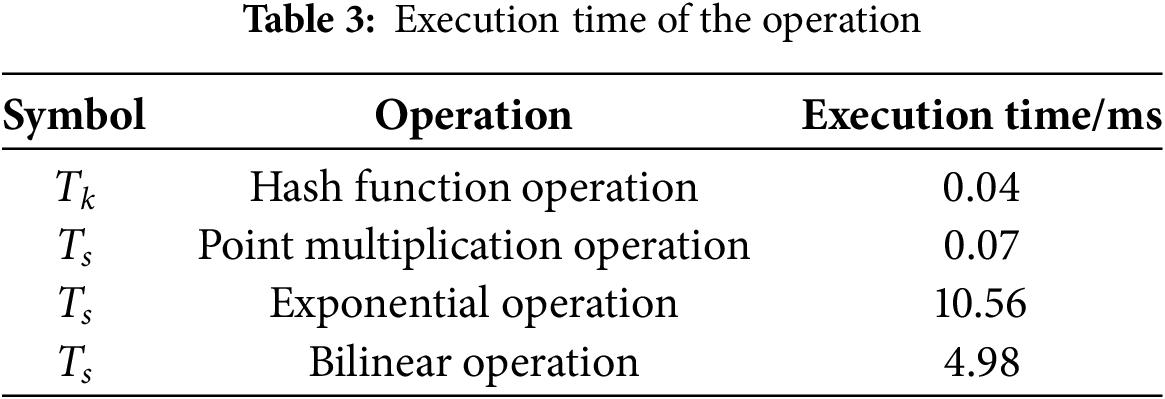

To compare the computational overhead, we conducted simulation experiments using a desktop PC equipped with Windows 10, an Intel Core i3-10100 CPU running at 3.60 GHz, and 16 GB of RAM. The evaluation focuses on health passport retrieval and signature verification, which are the primary computationally intensive stages in our proposed scheme. Table 3 presents the execution time for key cryptographic operations.

We benchmarked our approach against existing blockchain-based healthcare authentication schemes, specifically those in references [18,33,34]. The computational overhead comparison is provided in Table 4, where n represents the number of users. Reference [32] was excluded from this comparison as it does not provide detailed computational metrics.

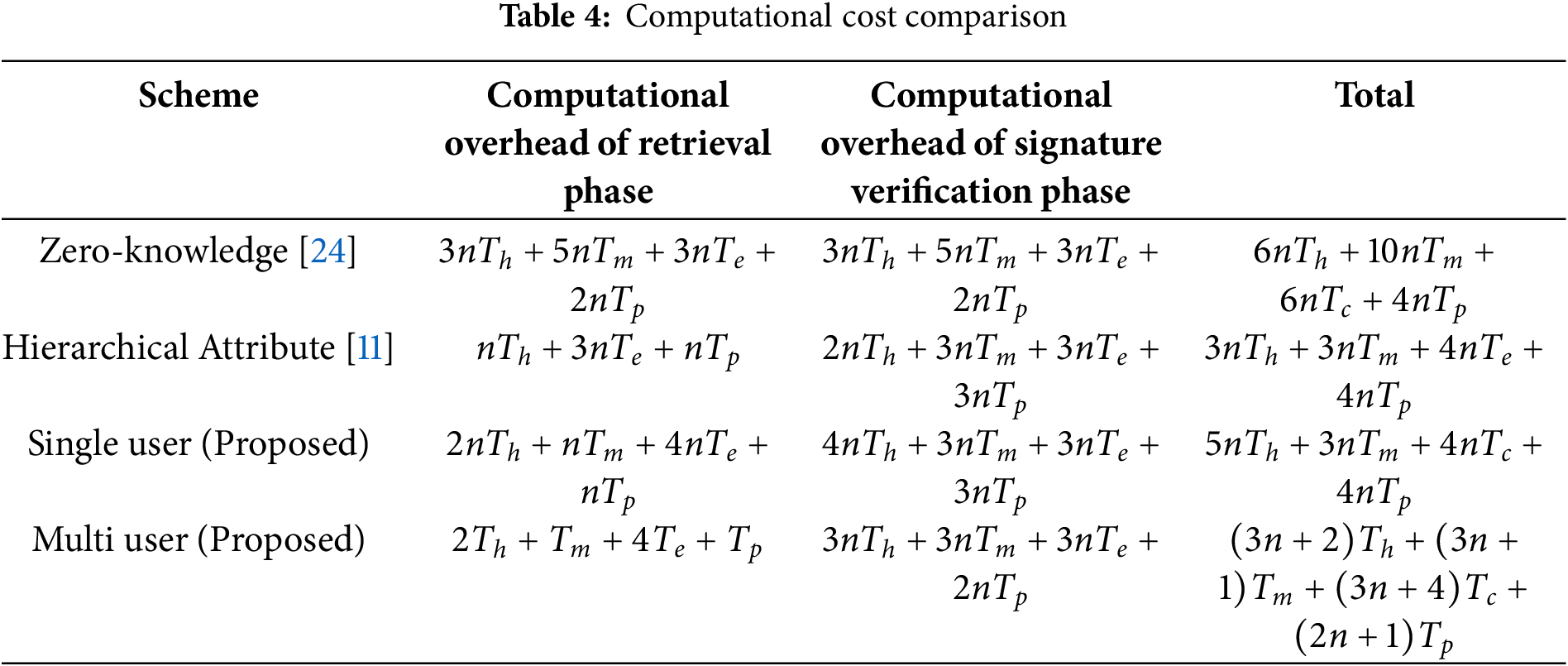

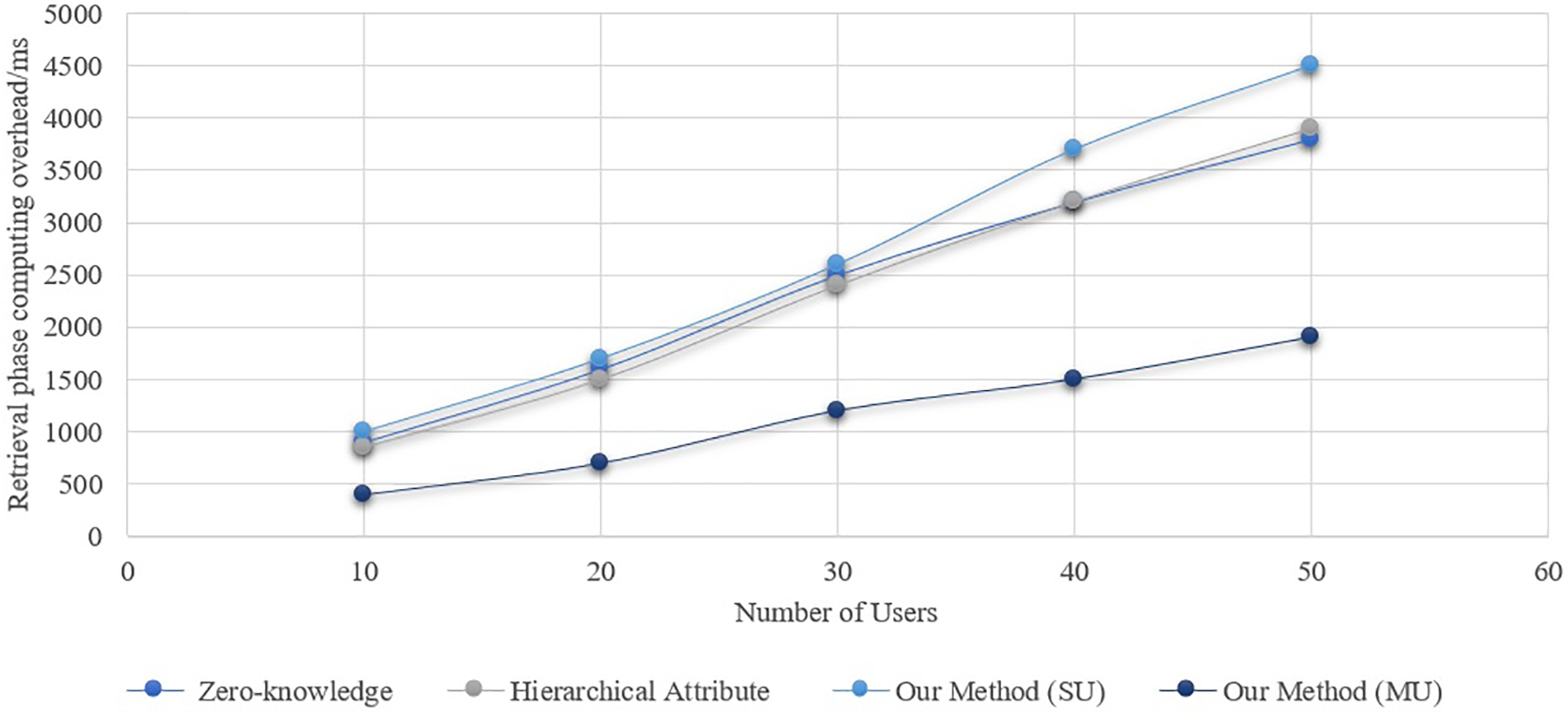

Figs. 3–5 compare the computational overhead at several levels. Fig. 3 shows the computational overhead during the health passport retrieval stage. The x-axis represents the number of users, while the y-axis shows the time taken (in milliseconds) for data retrieval. The comparison includes our proposed scheme against prior methods [34] and [33]. Lower computational overhead indicates a more efficient retrieval process.

Figure 3: Computational overhead at the retrieval stage

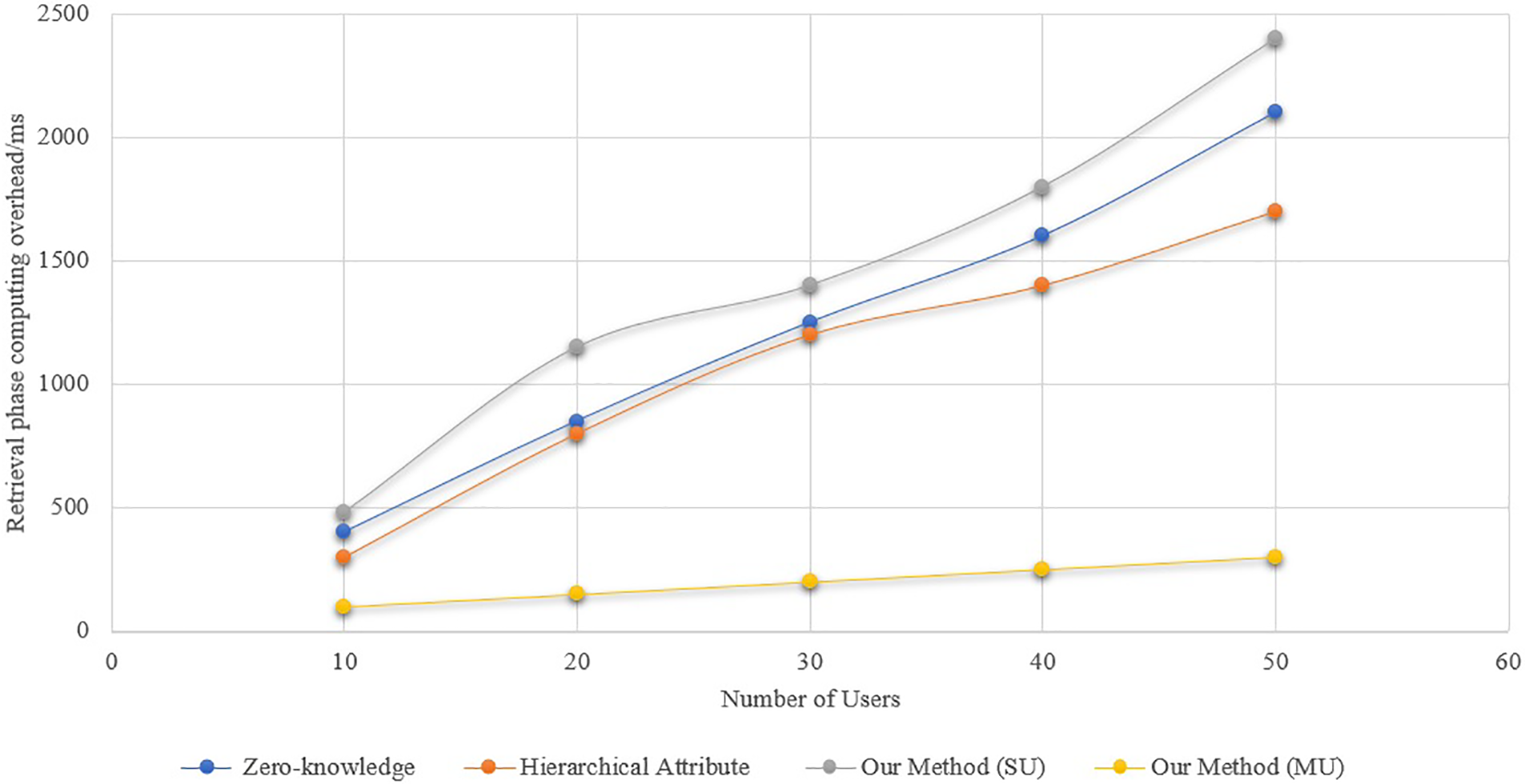

Figure 4: Computational overhead at the signature verification stage

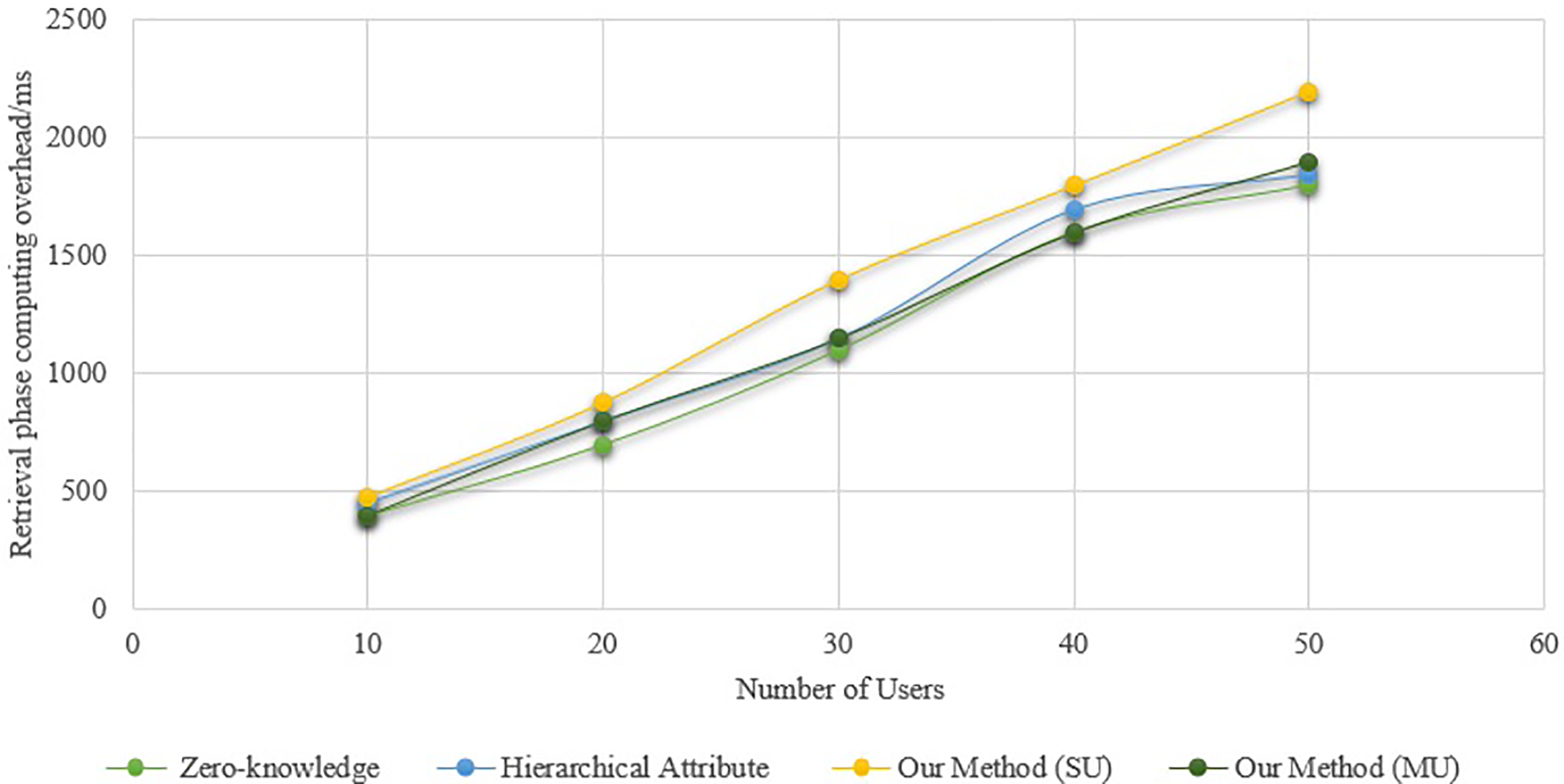

Figure 5: Total computational overhead

The systems mentioned in reference [34] have lower computational overheads than the scheme in the single-user case, but they aren’t as good as the method in the multi-user situation. The difference will widen as the number of users increases. Unlike earlier techniques, which necessitate retrieving each user’s health passport individually, the aggregate signature technology introduced in this paper’s scheme simply requires one retrieval. The retrieval stage’s computing overhead increases with the number of users. During the signature verification stage, Fig. 4 shows the computational overhead of the technique. In the single-user scenario, the computational cost of the signature verification in this paper’s technique is higher than in reference [33], but it’s about the same as in reference [18]. This paper’s approach, which is applicable to both single- and multiple-user scenarios, has lower computing cost during the signature verification stage compared to the scheme in reference [33]. Reason being, compared to the scheme in reference [18], the signature verification procedure of the scheme in reference [34] and this paper’s scheme reduces one bilinear operation, slightly lowering the computational overhead of signature verification. Also, the suggested technique has a small benefit over the solution in the literature [33] since it reduces 2 multiplication processes.

Fig. 5 is for the scheme’s total computing cost. With a maximum optimization of 49.89%, the suggested method clearly outperforms the current system in terms of overall computing cost in the multi-user situation. The reason behind this is that the suggested system takes into account the possibility of merging complex calculations (like bilinear mapping and exponential operations) when the user group performs retrieval and verification, in contrast to the present scheme. Combining the calculation processes for a single user with those for a multi-user scenario allows for the realization of calculation merging in the latter. Despite this, in the single-user scenario, the computational cost of the proposed scheme will be higher than other existing schemes. However, in the multi-user scenario, from the Healthcare device data retrieval stage to the verification stage, other existing schemes clearly have higher computational costs than the proposed scheme (Figs. 3–5). Consequently, the suggested approach is better suited to situations involving international communication or foreign travel due to its greater efficiency advantage in real applications. An adversarial actor might potentially falsify a valid user’s health passport within the scheme, rendering the signature verification ineffective. Finding the malicious forger after signature verification fails requires re-obtaining and confirming each user’s signature individually.

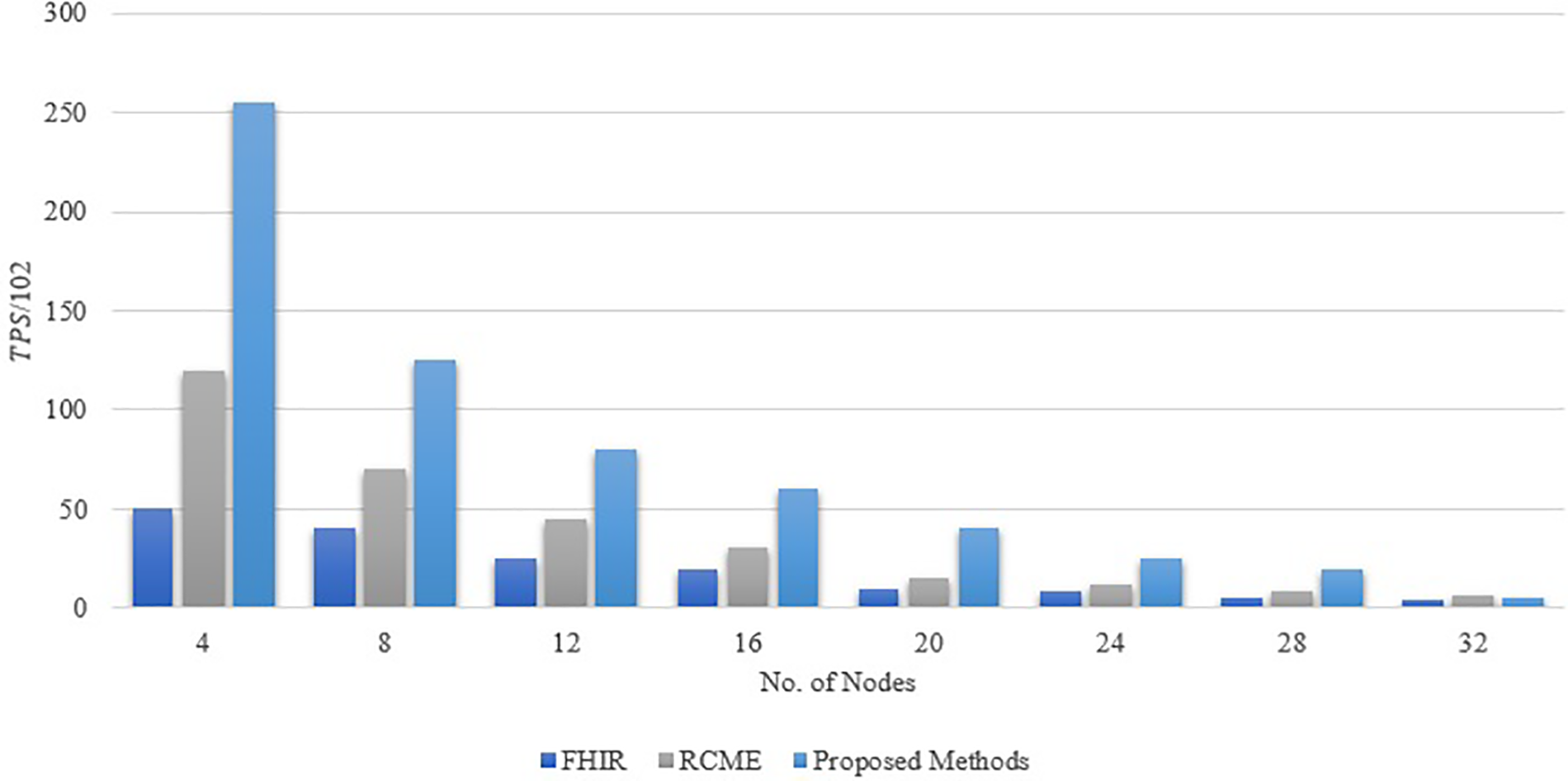

To evaluate the efficiency of the improved weak consensus algorithm proposed in this paper, simulations of the PBFT algorithm [35], the weak consensus algorithm, and the improved weak consensus algorithm were conducted using Java as the programming language. The simulations modeled a P2P network environment with

where

Figure 6: Comparison of consensus efficiency

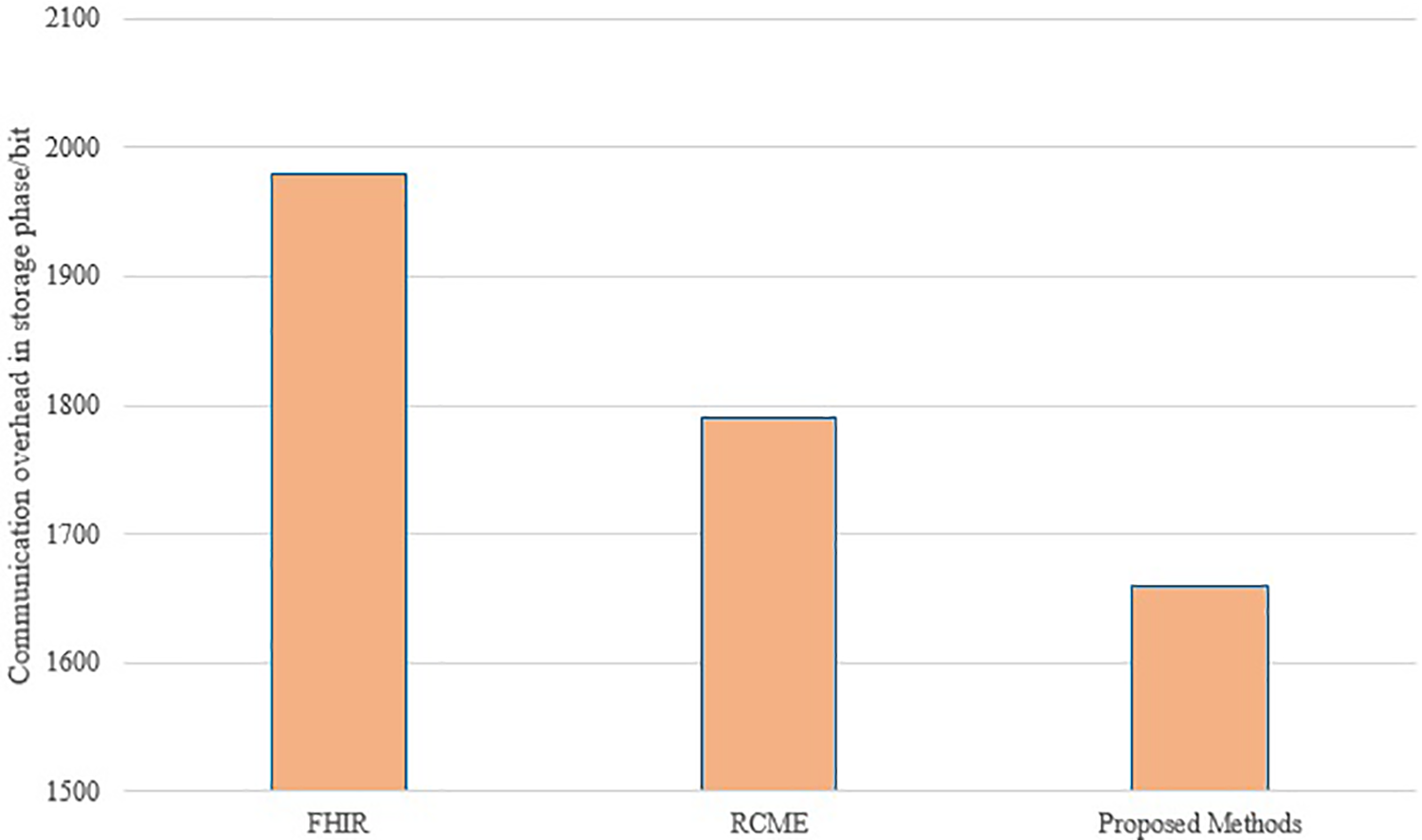

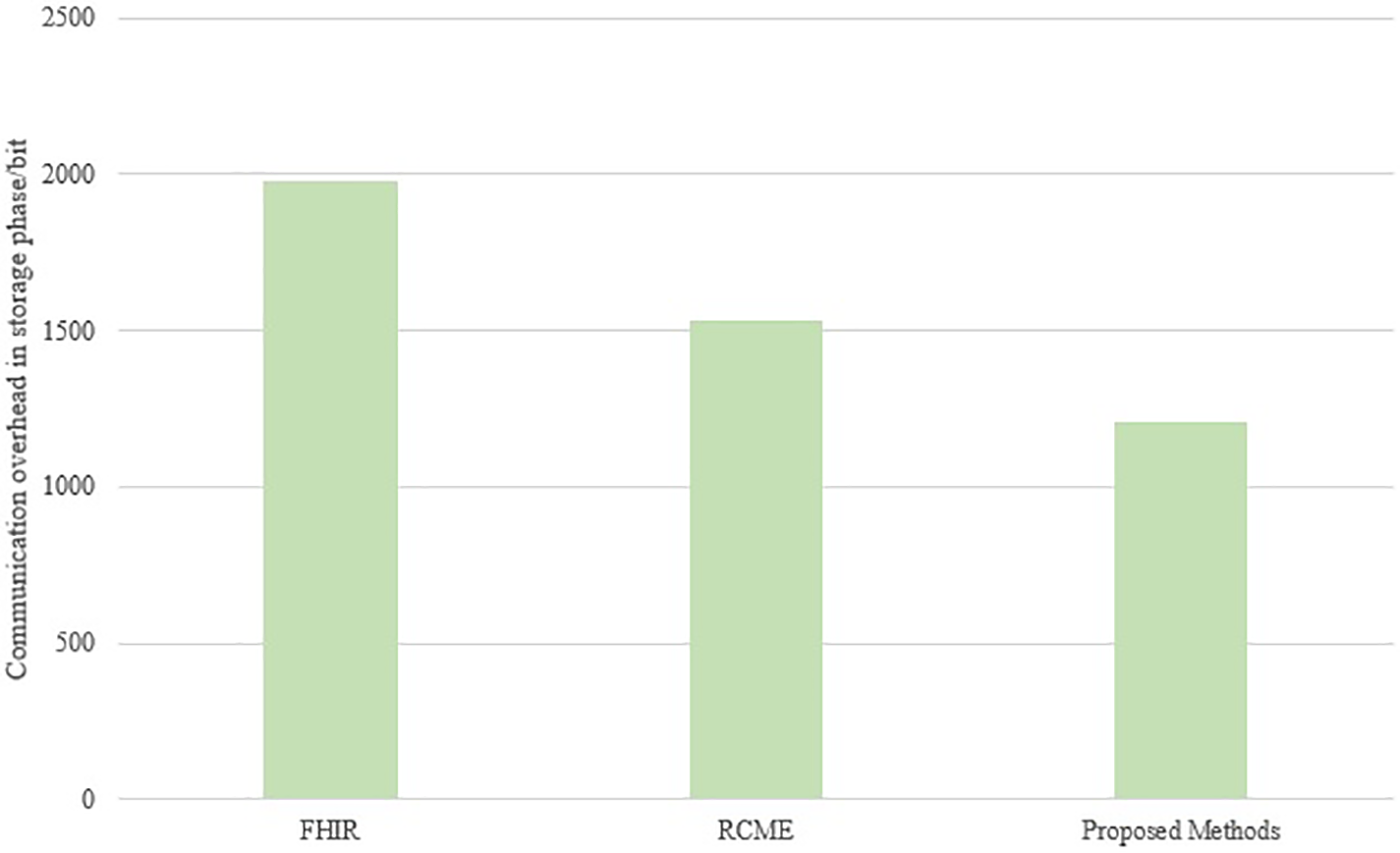

Assuming that the length of the index, trapdoor, hash value, and key pair is 256 bits, the length of the health passport data ciphertext is 512 bits, the length of the signature is 1024 bits, the length of the ID is 128 bits, and the length of the timestamp is 64 bits, the communication overhead in the storage phase is shown in Fig. 7. In the health passport data storage phase, the solution in reference [34] needs to send 1984 bits, the solution in reference [33] needs to send 1792 bits, and the solution in this paper only needs to send 1664 bits; in the retrieval phase, the communication overhead is shown in Fig. 8. The solution in reference [34] needs to send 1984 bits, the solution in reference [33] needs to send 1536 bits, and the solution in this paper only needs to send 1280 bits. Compared with the solutions in reference [34], the communication overhead of the solution in this paper is smaller, with the highest optimization of 25.81%, which is attributed to the reduction of unnecessary transmission (such as timestamps and keys).

Figure 7: Comparison of communication overhead in storage phase

Figure 8: Comparison of communication overhead in the retrieval phase

While our proposed blockchain-based health passport system offers significant security and efficiency advantages, real-world deployment presents several challenges:

1. Cost and Infrastructure Requirements: Implementing blockchain-based solutions requires computational resources for consensus mechanisms, storage, and encryption operations. Healthcare institutions must invest in compatible hardware and software, which may pose financial constraints, especially in resource-limited regions.

2. Energy Consumption: Blockchain networks, particularly those using consensus mechanisms like PBFT, can be computationally intensive. Although our optimized weak consensus algorithm reduces communication overhead, further work is needed to explore energy-efficient blockchain frameworks suitable for large-scale healthcare adoption.

3. Regulatory Compliance: Ensuring compliance with healthcare data protection laws (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA) is critical. Blockchain’s immutability raises challenges for data modification or removal requests, necessitating privacy-preserving mechanisms such as zero-knowledge proofs.

4. User Adoption and Usability: Medical professionals and travelers may require training to interact with blockchain-based health passport systems. A user-friendly interface and integration with existing electronic health record (EHR) [36] systems will be essential for seamless adoption.

Future research will focus on optimizing energy efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and regulatory adaptability to facilitate real-world deployment in healthcare environments.

This paper addresses critical challenges in the global sharing of personal health passports, including “information islands,” inadequate privacy protection, and risks of forgery. To overcome these, a blockchain-based solution for health passport storage, sharing, and verification is proposed, integrating searchable encryption technology with blockchain to ensure secure, efficient, and scalable data management. The proposed scheme introduces an innovative combination of on-chain and off-chain storage using IPFS, enhancing storage optimization while maintaining reliability. Additionally, an improved aggregate signature mechanism is employed to facilitate efficient multi-user verification, while a two-stage weak consensus algorithm significantly improves blockchain throughput and reduces communication complexity. Through comprehensive security analysis and experimental validation, the scheme demonstrates notable advantages, achieving up to 49.89% optimization in computational overhead and up to 25.81% reduction in communication overhead in multi-user scenarios. However, challenges remain in single-user cases, where retrieval and signature verification overheads are higher than existing solutions. To address this, future research will explore lightweight cryptographic operations and hybrid storage mechanisms to enhance efficiency in low-volume transactions. Furthermore, ethical and legal considerations are paramount in blockchain-based healthcare systems. Our approach ensures compliance with GDPR and HIPAA by utilizing off-chain storage for sensitive data while maintaining secure on-chain references. To address blockchain immutability challenges, potential solutions include zero-knowledge proofs, revocable encryption, and hybrid blockchain governance models to uphold user privacy and the right to data modification. Future research will refine privacy-preserving techniques, regulatory adaptability, and energy-efficient consensus mechanisms to enhance scalability and real-world applicability. By addressing key concerns in security, privacy, efficiency, and ethical compliance, this work presents a robust and adaptable framework for secure health passport management, with significant potential for global healthcare data interoperability and secure international travel.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Yogendra P. S. Maravi drafted the manuscript, conducted the literature review, and implemented the proposed solution. Nishchol Mishra provided conceptualization, supervision, and manuscript review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ait Bennacer S, Aaroud A, Sabiri K, Rguibi MA, Cherradi B. Design and implementation of a New Blockchain-based digital health passport: a Moroccan case study. Inform Med Unlocked. 2022;35(2):101125. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2022.101125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Raman R, Sahayaraj KA, Soni M, Nayak NR, Govindaraj R, Singh NK. Semantic web techniques for clinical topic detection in health care. Comput Assist Methods Eng Sci. 2024;31(2):139–55. doi:10.24423/cames.2024.493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cao K, Cui Y, Li L, Zhou J, Hu S. CPU-GPU cooperative QoS optimization of personalized digital healthcare using machine learning and swarm intelligence. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2024;21(4):521–33. doi:10.1109/TCBB.2022.3207509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Hendy A, Abdelaliem SMF, Osman YM, Al-Kurdi Z, Zaher A, Hendy A, et al. Understanding Nurses’ perspectives on electronic health records in Egypt: insights from a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2025;80(7):e255–63. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2025.01.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Nguyen HS, Voznak M. A bibliometric analysis of technology in digital health: exploring health metaverse and visualizing emerging healthcare management trends. IEEE Access. 2024;12:23887–913. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3363165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alrowais F, Mohamed HG, Al-Wesabi FN, Al Duhayyim M, Hilal AM, Motwakel A. Cyber attack detection in healthcare data using cyber-physical system with optimized algorithm. Comput Electr Eng. 2023;108(9):108636. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Singh NK, Tomar DS, Singh RK. Blockchain-based privacy-protected reputation model for internet of vehicles. In: Kumar A, Ahuja NJ, Kaushik K, Tomar DS, Khan SB, editors. Contributions to environmental sciences & innovative business technology. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2024. p. 1–22. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-0088-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. George M, Chacko AM. Health passport: a blockchain-based PHR-integrated self-sovereign identity system. Front Blockchain. 2023;6:100001. doi:10.3389/fbloc.2023.1075083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rashid MM, Choi P, Lee SH, Kwon KR. Block-HPCT: blockchain enabled digital health passports and contact tracing of infectious diseases like COVID-19. Sensors. 2022;22(11):1–23. doi:10.3390/s22114256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Hasan HR, Salah K, Jayaraman R, Arshad J, Yaqoob I, Omar M, et al. Blockchain-based solution for COVID-19 digital medical passports and immunity certificates. IEEE Access. 2020;8:222093–108. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3043350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wei J, Huang X, Liu W, Hu X. Cost-effective and scalable data sharing in cloud storage using hierarchical attribute-based encryption with forward security. Int J Found Comput Sci. 2017;28(7):843–68. doi:10.1142/S0129054117500289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mohd Shari NF, Malip A. Enhancing privacy and security in smart healthcare: a blockchain-powered decentralized data dissemination scheme. Internet Things. 2024;27(1):101256. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ramzan S, Aqdus A, Ravi V, Koundal D, Amin R, Al Ghamdi MA. Healthcare applications using blockchain technology: motivations and challenges. IEEE Trans Eng Manag. 2023;70(8):2874–90. doi:10.1109/TEM.2022.3189734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Demirbaga U, Aujla GS. MapChain: a blockchain-based verifiable healthcare service management in IoT-based big data ecosystem. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2022;19(4):3896–907. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2022.3204851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jafari AMH, Patchmuthu RK, Tajuddin STH. Immutable COVID-19 vaccination certificate using blockchain. Procedia Comput Sci. 2024;233(3):194–203. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2024.03.209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zarour M, Ansari MTJ, Alenezi M, Sarkar AK, Faizan M, Agrawal A, et al. Evaluating the impact of blockchain models for secure and trustworthy electronic healthcare records. IEEE Access. 2020;8(X):157959–73. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3019829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Guerar M, Migliardi M, Russo E, Khadraoui D, Merlo A. SSI-MedRx: a fraud-resilient healthcare system based on blockchain and SSI. Blockchain: Res Appl. 2024;100242. doi:10.1016/j.bcra.2024.100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rajtar M. Patient passports and vulnerability: disjunctures in health policy instruments for people with rare diseases. Soc Sci Med. 2025;366(3):117642. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Moulahi W, Jdey I, Moulahi T, Alawida M, Alabdulatif A. A blockchain-based federated learning mechanism for privacy preservation of healthcare IoT data. Comput Biol Med. 2023;167(3):107630. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Seong D, Jung S, Bae S, Chung J, Son DS, Yi BK. Fast healthcare interoperability resources (FHIR) based quality information exchange for clinical next-generation sequencing genomic testing: implementation study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):1–21. doi:10.2196/26261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yang N, Tang C, Xiong Z, He D. RCME: a reputation incentive committee consensus-based for matchmaking encryption in IoT healthcare. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2024;17(5):2790–806. [Google Scholar]

22. Bharathi Murthy CVNU, Lawanya Shri M. Secure sharing architecture of personal healthcare data using private permissioned blockchain for telemedicine. IEEE Access. 2024;12:106645–57. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3436075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ren Z, Yan E, Chen T, Yu Y. Blockchain-based CP-ABE data sharing and privacy-preserving scheme using distributed KMS and zero-knowledge proof. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(3):101969. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nyato EJ, Kimito E, Yang J, Lee D, Lee D. Blockchain-integrated zero-knowledge proof system for privacy-preserving near-miss reporting in construction projects. Autom Constr. 2024;168(6):105825. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Singh MK, Pippal SK, Sharma V. Lightweight blockchain mechanism for secure data transmission in healthcare system. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2025;102(5):107411. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2024.107411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhou F, Huang Y, Li C, Feng X, Yin W, Zhang G, et al. Blockchain for digital healthcare: case studies and adoption challenges. Intell Med. 2024;4(4):215–25. doi:10.1016/j.imed.2024.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. d’Almeida S, Jamrozik E, Kerouedan D, Mossialos E. Challenges of balancing international health and travel in a pandemic: lessons from the French Caribbean during COVID-19 passports. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13(6):100327. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Abd-Alhalem SM, Marie HS, El-Shafai W, Altameem T, Rathore RS, Hassan TM. Cervical cancer classification based on a bilinear convolutional neural network approach and random projection. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;127(1):107261. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kim TH, Kumar G, Saha R, Alazab M, Buchanan WJ, Rai MK, et al. CASCF: certificateless aggregated signcryption framework for internet-of-things infrastructure. IEEE Access. 2020;8:94748–56. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2995443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yin H, Zhao Y, Zhang L, Qiao B, Chen W, Wang H. Attribute-based searchable encryption with decentralized key management for healthcare data sharing. J Syst Archit. 2024;148(12):103081. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2024.103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Shukla S, Thakur S, Hussain S, Breslin JG, Jameel SM. Identification and authentication in healthcare internet-of-things using integrated fog computing based blockchain model. Internet Things. 2021;15(11):100422. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2021.100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. de Figueiredo A, Larson HJ, Reicher SD. The potential impact of vaccine passports on inclination to accept COVID-19 vaccinations in the United Kingdom: evidence from a large cross-sectional survey and modeling study. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101109. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Uvaliyeva I, Borozenets D. Realization of conceptual model of IT-infrastructure of technology of differential diagnostics of clinical and hematological syndromes for health passport. In: 2024IEEE AITU: digital generation. Astana, Kazakhstan: IEEE; 2024. p. 174–80. [Google Scholar]

34. Shen Y, Yu J, Zhou J, Hu G. Twenty-five years of evolution and hurdles in electronic health records and interoperability in medical research: comprehensive review. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27(8):e59024. doi:10.2196/59024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Riahi K, el Amine Brahmia M, Abouaissa A, Idoumghar L. Multi-task learning for PBFT optimisation in permissioned blockchains. Blockchain: Res Appl. 2024;5(3):100206. doi:10.1016/j.bcra.2024.100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ullah F, He J, Zhu N, Wajahat A, Nazir A, Qureshi S, et al. Blockchain-enabled EHR access auditing: enhancing healthcare data security. Heliyon. 2024 Aug;10(16):e34407. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools