1 Introduction

Encryption was utilized about two thousand years ago, with early examples including the scytale transposition and Caesar cipher. Encryption methods fall into two categories. The first is symmetric encryption, which uses the same key for encryption and decryption. The second is public-key encryption, where the public key differs from the private key. Both symmetric and public key encryption are one-to-one encryption techniques. However, modern applications often require one-to-many encryption. For example, in encrypted file systems like cloud storage, a file might need to be securely shared with multiple users. In encrypted email systems, an email might need to be sent securely to several recipients. A private message might need to be sent to a group on social networks. Likewise, in pay-TV systems, a broadcaster might need to transmit a channel to a group of subscribers.

To address the challenge of flexible one-to-many encryption, Sahai and Waters [1] introduced the concept of attribute-based encryption (ABE), where user attributes govern encryption and decryption. Based on this, Bethencourt et al. [2] defined a variant of ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE) and developed a CP-ABE instance using bilinear pairing. In CP-ABE, encryption assigns an access policy to the ciphertext, and decryption is restricted to users whose attributes match this policy. This method allows for fine-grained access control. CP-ABE is ideal for large-scale data sharing across numerous devices, such as in cloud storage systems, mobile pay-TV, and IoT applications. With CP-ABE, the data owner sets an access policy, and the user’s secret key is derived from their attributes, enabling secure data sharing while preserving access control.

Currently, the most advanced technique for constructing CP-ABE schemes is based on bilinear pairing [3]. However, bilinear pairing is a complex operation with high computational costs, leading to long encryption times and high energy consumption. As a result, CP-ABE schemes using bilinear pairing are not suitable for lightweight devices that typically have limited computational resources and energy storage, such as mobile pay-TV, satellite transmission, and IoT applications.

To address this issue, CP-ABE schemes based on elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) were introduced [4–7]. Compared to bilinear pairing, scalar multiplication in ECC is much more efficient, making it suitable for implementation in lightweight devices. The first ECC-based CP-ABE scheme was proposed by Yao et al. [4]. However, it did not support fine-grained access policies, limiting its applicability in complex access control scenarios. Later, Ding et al. [5] introduced an ECC-based CP-ABE scheme that supports fine-grained access policies using linear secret sharing. Subsequently, Wang et al. [6] and Sowjanya and Dasgupta [7] proposed additional ECC-based CP-ABE schemes with support for fine-grained access control.

It is known that ABE (hence CP-ABE schemes)-even those limited to AND-gate policies, not just one supporting fine-grained access policy-is a generalization of identity-based encryption (IBE) (see [8]). This relation implies that the implementation of ABE (particularly, CP-ABE) encompasses the challenges of IBE. We also know that constructing a pairing-free IBE poses significant challenges in possibility, efficiency, complexity, and security, as evidenced in the literature, e.g., references [9,10] (note that theoretically several pairing-free IBE schemes have been proposed [11–13]). Therefore, pairing-free CP-ABE systems, including ECC-based ones, substantially amplifies these difficulties; the reader can also refer to [14] for a detailed discussion on this. This is also the reason, why several significant CP-ABE schemes based on bilinear pairing have also been developed, including those by [15–19], and [20–24] among others. Despite their higher computational requirements, these schemes remain important in the field.

Security in ABE. Attacks in ABE can be divided into external and internal. External attacks come from unauthorized users trying to access the system. Most ABE schemes handle these well through access control structures, assuming legitimate users do not publicly leak information. In contrast, internal attacks involve legitimate but dishonest users (malicious insiders) who may leak their secret information to outsiders. These are more difficult to prevent, as the main deterrent is the ability to trace leaks back to their source.

One of the internal attacks is the attribute collusion attack. In the attack, multiple users with distinct attributes, none of whom individually satisfies the access policy, collaborate by combining their attributes to bypass the policy and successfully decrypt a ciphertext. For instance, in a hospital’s record system using ABE, different staff members (e.g., doctors and nurses) may have individual permissions. Without resistance to attribute collusion, a group of nurses could pool their attributes to gain access to patient records intended for doctors, violating privacy policies. Therefore, the collusion resistance is a required and desired property for any ABE system. In particular, the standard security model for CP-ABE is defined through the game against the attribute collusion attack.

We know that the most severe case of internal attacks is when a single user or a small group of users can generate an anonymous secret key (any polynomial-time algorithm cannot trace that) and publicly release or sell this key. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no ABE work in the literature that discusses, defines, and deals with such attacks. Our paper is the first to define this attack and call it the anonymous key-leakage (AKL) attack. We also stress that the attack is defined outside the security model (against the attribute collusion attack) of the ABE scheme. Therefore, an ABE scheme that is insecure against this AKL attack does not mean the scheme is insecure in its security model. However, when choosing CP-ABE schemes to deploy in practice, this new attack is worth considering.

Contribution. This work’s contribution includes the following:

• We present the attribute collusion attack on several ECC-based CP-ABE schemes.

• We are the first to define the anonymous key-leakage (AKL) attack.

• We theoretically conduct the AKL attack on several important pairing-based CP-ABE schemes in the literature.

Related Work and Comparison. In 2020, Javier Herranz proposed the attribute collusion attack on several ECC-based CP-ABE schemes [14]. He also argued about the difficulty in constructing pairing-free CP-ABE schemes. Our work proposes the attribute collusion attack on several new other ECC-based CP-ABE schemes. Our and his proposed attack are practical but in different ECC-based CP-ABE schemes. Moreover, in this work, we additionally propose a new kind of practical attack (different from the attribute collusion attack) on several important pairing-based CP-ABE schemes (published in several flagship conferences such as ACM CCS, Eurocrypt, PKC, Asia CCS). Although these pairing-based CP-ABE schemes are still secure in their defined security model, we should consider this new attack when choosing them to deploy in practice.

Very recently, Siyal et al. [25] have introduced the so-called adaptive attribute-based honey encryption (AABHE) scheme to protect cloud data by generating believable decoy ciphertexts (“honeywords”) to deceive attackers. While our study focuses on CP-ABE vulnerabilities, particularly insider attacks such as attribute collusion and anonymous key-leakage attacks, AABHE offers a potential mitigation strategy by making leaked keys less exploitable. However, as honey encryption primarily defends against side-channel and brute-force attacks rather than insider threats, its effectiveness against collusion-based key leakage remains uncertain.

Traitor tracing [26] is a technique that allows the tracing of the traitor who used her secret key to produce a pirate box (decryption box). This technique is based on the property that each user’s secret key will have a unique property associated with this user. In contrast, the AKL attack is based on the property that the secret key used to produce the pirate box can be created by many users and has no unique property. Therefore, the traitor tracing technique cannot be applied to defend against the AKL attack.

Organization. The paper is organized as follows: In Section 1, we give an introduction to the research problem. Section 2 presents some related background knowledge. Next, we describe the attribute collusion attack in several ECC-based CP-ABE schemes in Section 3. Section 4 defines the anonymous key-leakage attack and then presents the attack on several pairing-based CP-ABE schemes. Finally, we conclude this work in Section 5.

2 Preliminaries

2.1 Pairings

Given a security parameter λ, let p=p(λ) be a prime number. Define G,G~,GT as cyclic groups of order p with generators g and g~ for G and G~, respectively. The generator gT of GT is computed as e(g,g~), where e:G×G~→GT is a non-degenerate bilinear map (also known as a pairing). For all x,y∈Zp, the following properties hold: (i) e(gx,g~y)=e(g,g~)xy; (ii) If g≠1G and g~≠1G~, then e(g,g~)≠1GT; (iii) It is efficient to compute e(g,g~). The tuple D=(p,G,G~,GT,e) is referred to as a bilinear map group system.

2.2 Attribute-Based Encryption

This section outlines the syntax and security model of a CP-ABE scheme.

2.2.1 Syntax

A CP-ABE scheme comprises four probabilistic algorithms:

• (MSK,param)←Setup(1λ,ℬ): On input a security parameter λ and an attribute universe ℬ, the algorithm outputs a master secret key MSK and public parameters param for the system.

• du←Extract(u,ℬ(u),MSK,param): Given a user u, the set of attributes ℬ(u) associated with u, the public parameters param, and the master secret key MSK, this algorithm produces the user’s private key du.

• ct←Encrypt(ℳ,A,param): This algorithm takes a message ℳ, an access policy A over the attribute universe ℬ, and the public parameters param as inputs. It generates a ciphertext ct.

• ℳ/⊥←Decrypt(ct,du,param): This algorithm takes a ciphertext ct, the private key du of user u, and the public parameters param. It returns the message ℳ if the attributes ℬ(u) of user u meet the criteria set by the access policy A. If not, it outputs ⊥.

2.2.2 Security Model

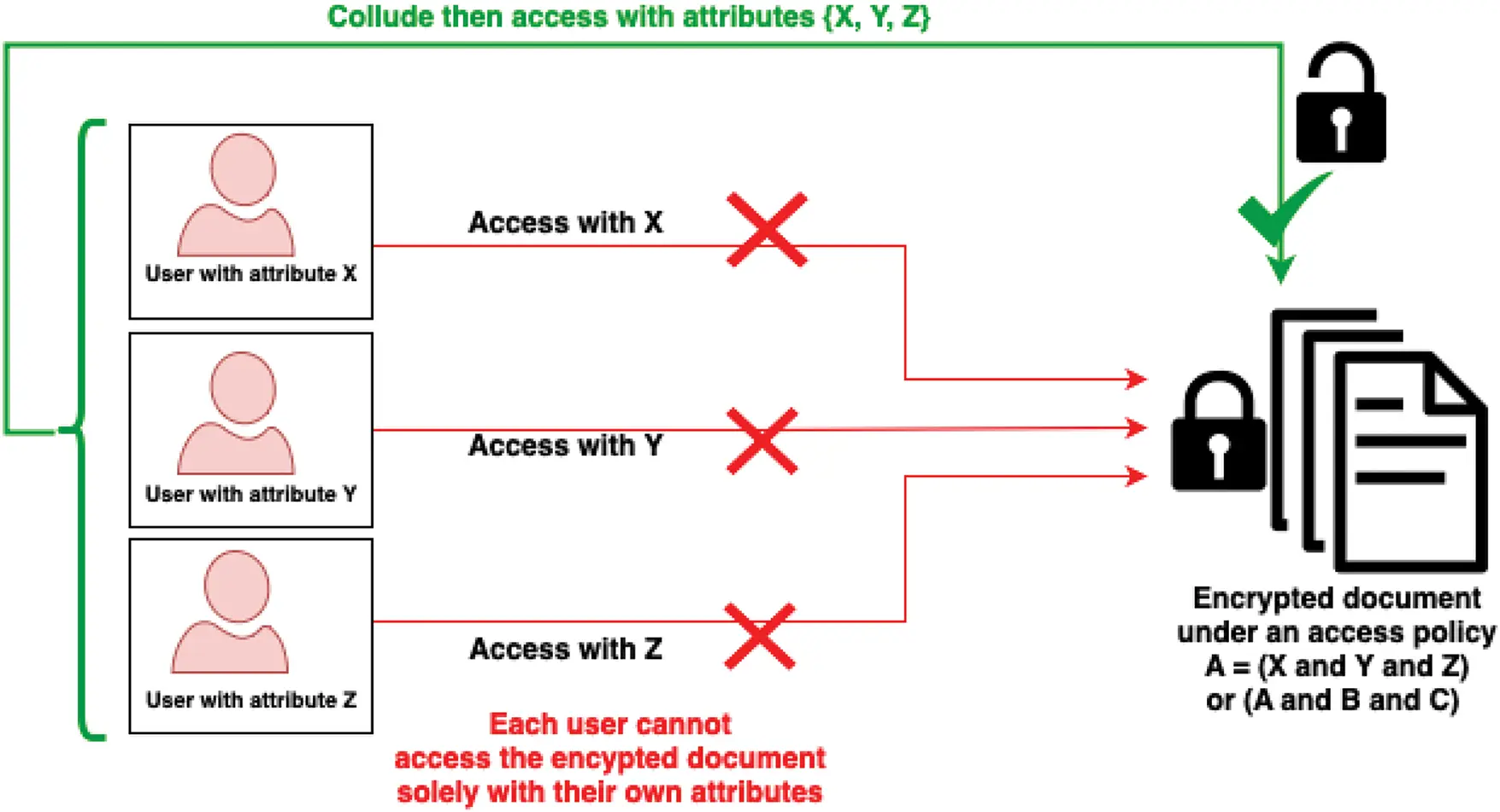

In ABE and particularly CP-ABE schemes, multiple users with different attributes (each user not meeting the access policy alone) may collaborate to decrypt a ciphertext they otherwise could not access individually. Users can combine their attributes to bypass the intended access control when collusion is possible. This is called the attribute collusion attack. We illustrate the attack in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The figure illustrates an attribute collusion attack in ABE, where multiple users combine their attributes to bypass access restrictions. Each user possesses only one attribute (X, Y, or Z), which is insufficient to decrypt the document individually. However, by colluding and pooling their attributes, they satisfy the access policy (X, Y, and Z) and successfully decrypt the document

The security model for a CP-ABE scheme is defined through the following probabilistic game involving an attacker 𝒜 and a challenger 𝒞, which models an attribute collusion attack:

ATTRIBUTE COLLUSION SECURITY GAME:

1. (param,MSK)←Setup(1λ,ℬ), /* Challenger keeps MSK secret.*/

ΛC:=∅. /* Corruption list.*/

2. (ΛC,{(ℬ(u),du)}u)←𝒜Extract(⋅,⋅,MSK,param). /* du←Extract(u,ℬ(u),MSK,param), */

/* ΛC:=ΛC∪{u}u. */

3. (A∗,ℳ0∗,ℳ1∗)←𝒜, /* where |ℳ0∗|=|ℳ1∗|.

4. b←${0,1}, ct∗←Encrypt(ℳb∗,A∗,param).

5. (ΛC,{(ℬ(u),du)}u)←𝒜Extract(⋅,⋅,MSK,param).

6. b′←𝒜.

The adversary wins the game if b′=b and if the attribute set ⋃u∈ΛCℬ(u) does not satisfy the target policy A∗. The adversary’s advantage is defined as Adv𝒜:=Pr[𝒜 wins the game].

Definition 1: A CP-ABE scheme is considered secure against the attribute collusion attack if the advantage of any polynomial-time adversaries in the above game is negligible.

3 Attribute Collusion Attack on Several ECC-Based CP-ABE Schemes

In this section, we show that several important existing pairing-free CP-ABE schemes [5–7] are susceptible to the attribute collusion attack, or these schemes are insecure in their defined security model. The reason why this attack exists in such schemes comes from the insecure structures of their schemes. To analyze deeper, we know that CP-ABE scheme is a generalization of IBE, and as shown in [9,10], constructing a pairing-free IBE poses significant challenges in possibility, efficiency, complexity, and security. Therefore, constructing pairing-free CP-ABE systems, including ECC-based ones, substantially amplifies these difficulties. Revising the insecure structures of their schemes is a challenging task. Note that to date, there are only a few inefficient pairing-free IBE schemes have been proposed [11–13].

3.1 Attribute Collusion Attack on Ding et al.’s Scheme

In Ding et al.’s scheme [5], each user is associated with an identity GID and receives a secret key SKi,GID corresponding to each possessed attribute i as SKi,GID=ki+H(GID)⋅n, where ki is a random element chosen for each attribute i, H is a secure hash function and n is the master key MSK.

For simplicity, let us consider that Bob with identity GIDBob possesses attributes i and j. Alice with identity GIDAlice possesses attribute i. We will show that when Bob and Alice collude, they can produce secret key of attribute j for Alice. To this end, they first compute:

X=SKi,GIDBob−SKi,GIDAlice=ki+H(GIDBob)⋅n−ki−H(GIDAlice)⋅n=H(GIDBob)⋅n−H(GIDAlice)⋅n

Next, compute the secret key of attribute j for Alice as:

Y=SKj,GIDBob−X=kj+H(GIDBob)n−(H(GIDBob)n−H(GIDAlice)n)=kj+H(GIDAlice)⋅n

Correctness. In Ding et al.’s scheme, each user associated with an identity GID and possessing attribute i will receive a secret key SKi,GID=ki+H(GID)⋅n. Hence, it is obvious to verify that Y=kj+H(GIDAlice)⋅n is the Alice’s secret key corresponding to attribute j. Consider a general case, Bob possesses attributes i,j1,j2,…,jk, Alice possesses attribute i and u. A secured CP-ABE scheme requires that even if Alice and Bob collude, they cannot decrypt the access policy required possessing all attributes i,j1,j2,…,jk,u. However, as shown above, Bob can help Alice to produce secret keys corresponding to attributes j1,j2,…,jk. Alice thus can possess all attributes i,j1,j2,…,jk,u. Hence, Alice can easily decrypt the access policy requiring possessing all attributes i,j1,j2,…,jk,u, so Ding et al.’s scheme is susceptible to attribute collusion attack. We also emphasize that Bob needs to know only Alice’s secret key corresponding to attribute i to help Alice to produce secret keys corresponding to attributes j1,j2,…,jk.

Performance. To compute the secret key for one attribute, it is easy to see that Bob only needs to compute two subtractions, one to compute X and the other to compute Y. Hence, the complexity of cryptanalysis depends on each specific case of attack. In general, to generate secret keys for t attributes, the complexity is just 2t subtractions, which is very practical.

3.2 Attribute Collusion Attack on Wang et al.’s Scheme

In Wang et al.’s scheme [6], the master key MSK is the set (α,β,γ,aatt1,…,aatt|𝒰|), where aatti is the secret element corresponding to attribute atti, and 𝒰 is the set of attributes in the system. For each user Uj possessing the attribute set UAj={att1j,…,attmj}⊆𝒰, the authority chooses uj←$Zp∗ and computes the secret key skj=(skj1,skj2) for user Uj as

skj1=α−uj,skj2={(rattij1,rattij2)|i=1,…,m}

where (rattij1,rattij2),i=1,…,m are randomly chosen such that aattij+uj=γrattij1+βrattij2.

For simplicity, let us consider the case that Bob possesses the attribute set UABob={att1,att2}. Alice possesses the attribute set UAAlice={att1}. We will show that when Bob and Alice collude, they can produce secret key of attribute att2 for Alice. To this end, they first compute:

skBob1−skAlice1=α−uBob−(α−uAlice)=uAlice−uBob.

Consider the attribute att1, the corresponding sub secret key for Bob is (ratt11,Bob,ratt12,Bob), for Alice is (ratt11,Alice,ratt12,Alice), where

aatt1+uBob=γratt11,Bob+βratt12,Bob,

and aatt1+uAlice=γratt11,Alice+βratt12,Alice. So, it implies that

aatt1+uAlice−aatt1−ubob=uAlice−uBob=γ(ratt11,Alice−ratt11,Bob)+β(ratt12,Alice−ratt12,Bob).

Consider the attribute att2, the corresponding sub secret key for Bob is (ratt21,Bob,ratt22,Bob), where

aatt2+uBob=γratt21,Bob+βratt22,Bob.

So, they have:

aatt2+uBob+uAlice−uBob=aatt2+uAlice=γratt21,Bob+βratt22,Bob+γ(ratt11,Alice−ratt11,Bob)+β(ratt12,Alice−ratt12,Bob)=γ(ratt21,Bob+ratt11,Alice−ratt11,Bob)+β(ratt22,Bob+ratt12,Alice−ratt12,Bob).

Correctness. Let ratt21,Alice=ratt21,Bob+ratt11,Alice−ratt11,Bob,ratt22,Alice=ratt22,Bob+ratt12,Alice−ratt12,Bob. We can easily check that (ratt21,Alice,ratt22,Alice) is Alice’s secret key corresponding to attribute aatt2 since

aatt2+uAlice=γ(ratt21,Bob+ratt11,Alice−ratt11,Bob)+β(ratt22,Bob+ratt12,Alice−ratt12,Bob)=γratt21,Alice+βratt22,Alice.

as requirement of Alice’s secret key corresponding to attribute att2. In addition, to compute (ratt21,Alice,ratt22,Alice), it is easy to see that Bob only needs to know Alice’s secret key corresponding to attribute att1. Hence, as Ding et al.’s scheme [5], Wang et al.’s scheme is also susceptible to attribute collusion attack.

Performance. It is easy to see that to compute (ratt21,Alice,ratt22,Alice) (the secret key for one attribute) Bob needs to compute four additive operations and two subtractions. Hence, as Ding et al.’s scheme, the complexity of cryptanalysis depends on each specific case of attack. In general, to generate secret keys for t attributes, the complexity is just 6t additions/subtractions, which is very practical.

3.3 Attribute Collusion Attack on Sowjanya et al.’s Scheme

In Sowjanya et al.’s scheme [7], the master key MSK is the set (α,α1,…,αn), where αi is the secret element corresponding to attribute Ai. Each user is associated with an identity UID. If she possesses the attribute Ai, she receives a secret key Di corresponding to attribute Ai as

Di=H(UID)⋅α⋅αi−1.

Note that in the decryption algorithm, the data receiver needs to know H(UID) to decrypt. Hence, each user in the system knows her identity.

For simplicity, let us consider the case that Bob possesses the attribute set {A1,A2} and Alice possesses the attribute set {A1}, we will show that when Bob and Alice collude, they can produce secret key of attribute A2 for Alice. To this end, they compute:

D2Alice=D2BobH(UIDBob)⋅H(UIDAlice)=H(UIDAlice)⋅α⋅α2−1.

Note that they know UIDBob and UIDAlice.

Correctness. We can easily verify that D2Alice=H(UIDAlice)⋅α⋅α2−1 is Alice’s secret key corresponding to attribute A2. Bob needs to know Alice’s identity to compute D2Alice. Hence, Sowjanya et al.’s scheme is also susceptible to attribute collusion attacks.

Performance. To compute D2Alice (the secret key for one attribute), Bob needs to compute one multiplicative operation and one inverse operation. Hence, the complexity of cryptanalysis depends on each specific case of attack. In general, the complexity of generating secret keys for t attributes is just 2t multiplicative/inverse operations. Thus, it is very practical.

4 Anonymous Key-Leakage Attack on Pairing-Based CP-ABE Schemes

This section defines a novel attack called the anonymous key-leakage (AKL in short) attack. We then present the attack on several CP-ABE schemes, including the schemes by [15], the Riepel and Wee’s CP-ABE scheme at CCS’22 [22] and some others.

4.1 Definition of the Anonymous Key-Leakage Attack

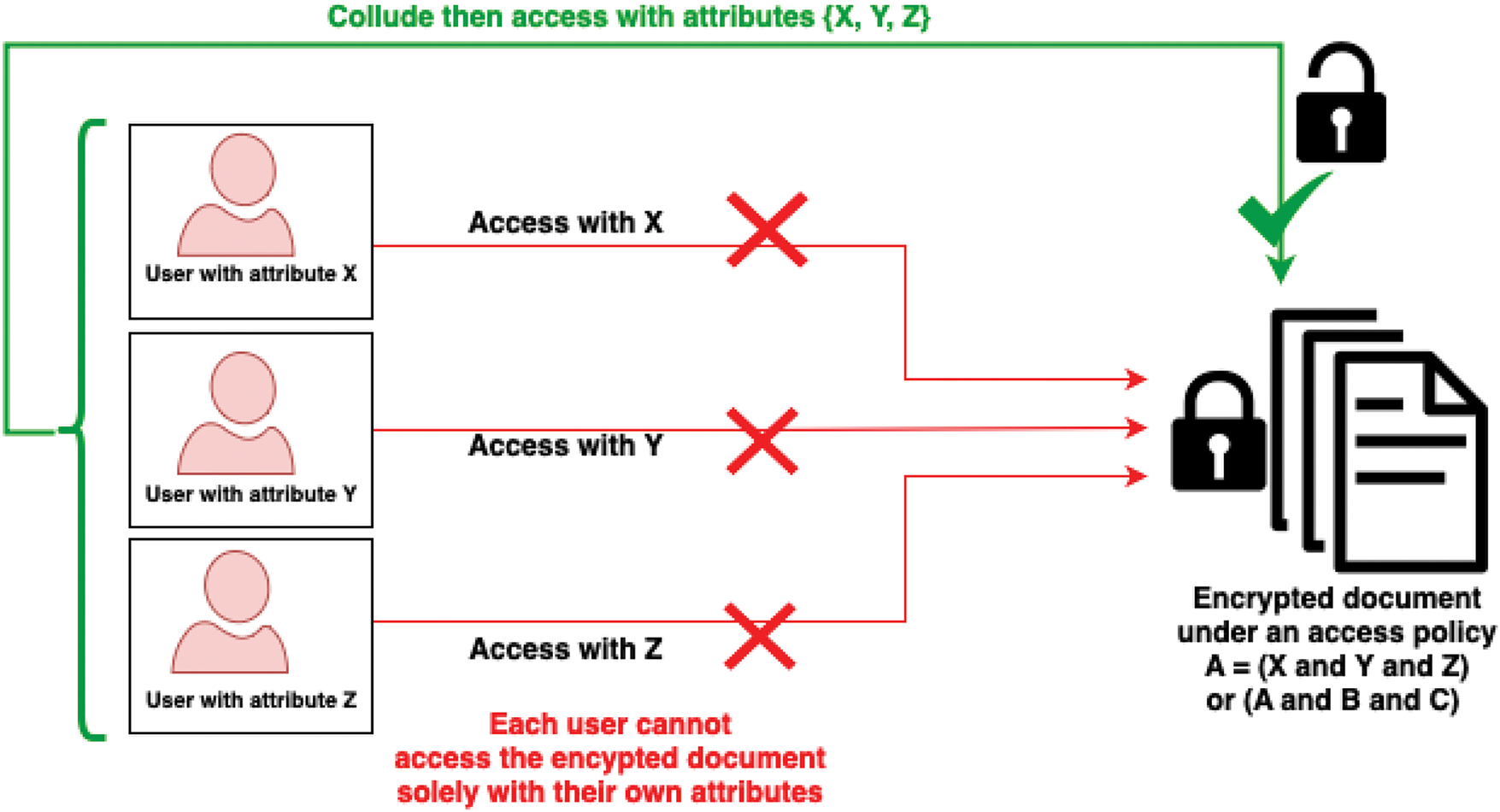

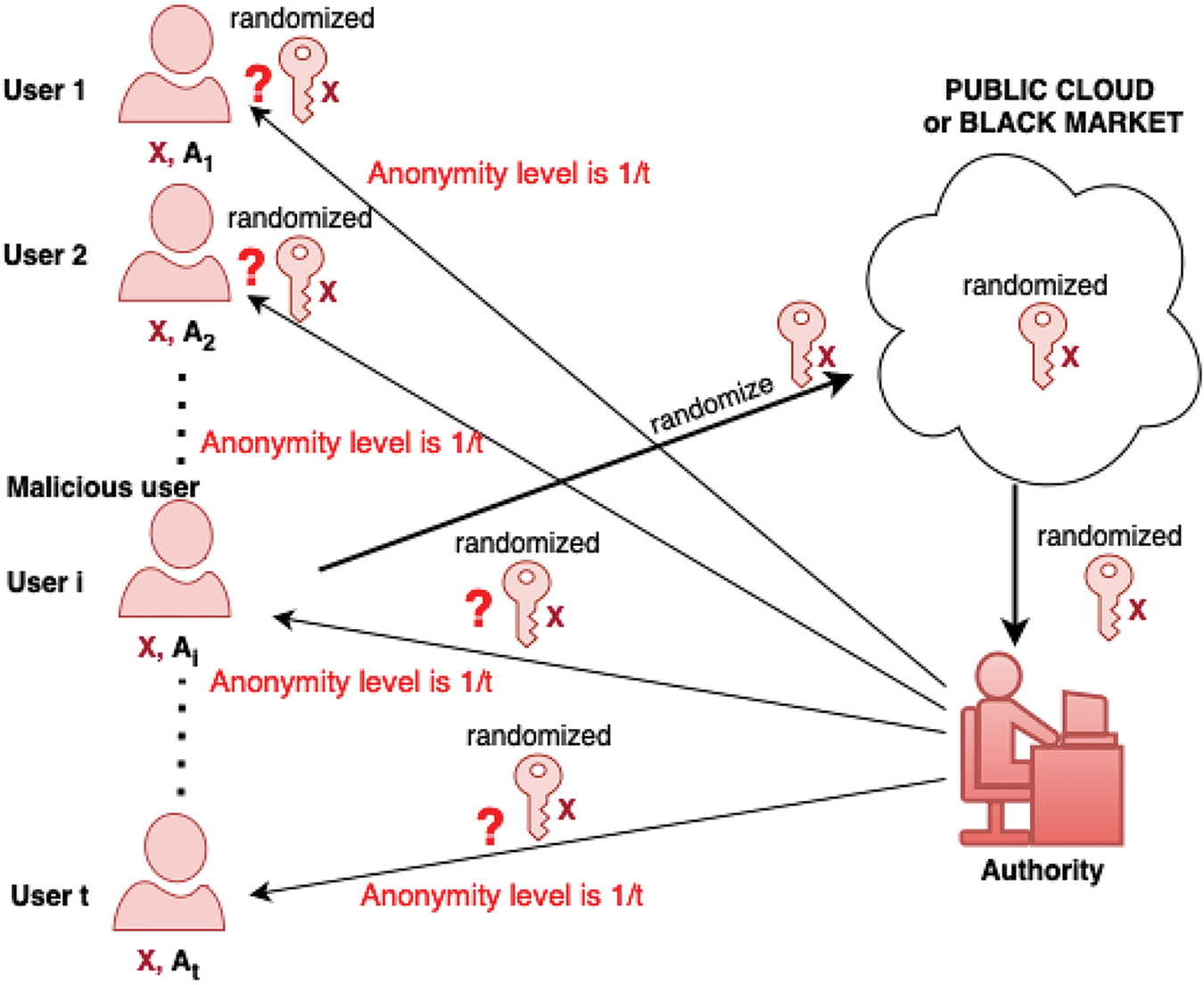

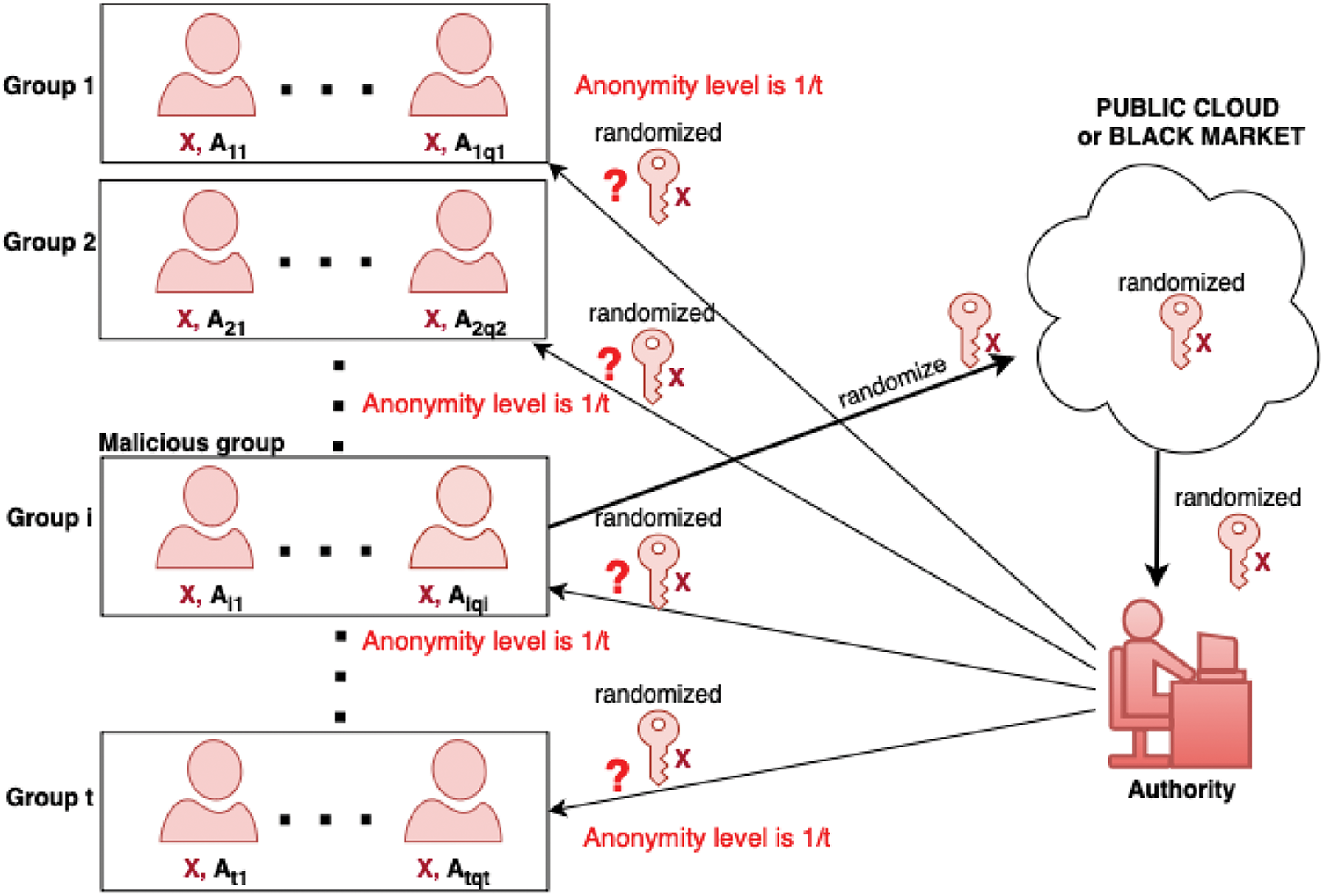

When considering encryption for a set of users, one can classify the attacks into external and internal. The external attacks come from non-legitimate users trying to access the system. Most CP-ABE schemes deal well with this kind of attack via the structure of access control and with the assumption (defined by the security model) that legitimate users leak nothing into the public database. Internal attacks are about the insiders in the system who are legitimate but dishonest users (called malicious users) who want to leak their secret information to an external pirate. It is often quite complicated to deal with internal attacks because we can only discourage legitimate users from leaking information by the possibility of tracing the source of the leakage. The most disastrous scenario is when a sole legitimate user (see Fig. 2) or multiple collusion groups of legitimate users (see Fig. 3) can produce an anonymous secret key (i.e., any polynomial time trace algorithm cannot determine who exactly generates this key) and leak this key into the public (even sell it to the black market). We name this the anonymous key-leakage attack.

Figure 2: This figure illustrates the scenario of AKL attack with a single malicious user, where multiple users (t users) possess the same attribute set X (though each user may have additional attributes). Here, one (malicious) user could randomize a part of the secret key that corresponds to X and then publish the randomized secret key on a public cloud or a black market while retaining anonymity at a level of 1/t, as any of the t users could perform this action

Figure 3: This figure depicts a case of AKL attack with a group of malicious users, where multiple groups (say, t) of users have a common set of attributes X. Here, one (malicious) group of users could randomize a part of the secret key that corresponds to X and then publish the randomized secret key on a public cloud or a black market while retaining anonymity at a level of 1/t as any of the t groups could perform this action

Definition 2: An AKL attack is formally defined as follows.

• In the beginning, a single malicious user (or a group of malicious users) receives the secret keys from the authority (who runs the key generation).

• The malicious user (or a group of malicious users that collude to produce) produces a new randomized secret key d with the property that this key can also be produced by t different users (or by t different groups of users).

• The malicious user (or a group of malicious users) publishes d in the public domain and remains anonymous at level t, in the sense that any polynomial time trace algorithm cannot exactly determine who generates d with a larger correctness probability 1/t.

If such an AKL attack exists on a scheme, then this scheme is said to be susceptible to the AKL attack.

The difference between the AKL attack model and the traditional security model is emphasized below.

• In the traditional security model, the attacker has all the secret keys of the malicious users and tries to decrypt the ciphertext that each of these secret keys is not capable of decrypting (equivalent to trying to create a new secret key that is stronger than all malicious secret keys).

• In the AKL attack model, the attacker still has all secret keys of the malicious users. However, on the contrary, she tries to create a new secret key that is a part of each of these secret keys (equivalent to trying to create a new secret key that is weaker than each malicious secret key), so that no one can know who created this new secret key. The AKL attack thus occurs due to the key structure of CP-ABE schemes.

In the rest of this section, we describe the AKL attack on several important CP-ABE schemes. However, we emphasize that these CP-ABE schemes are still secure in their defined security model. We argue here that even though the AKL attack is defined outside of their security model, it is worth considering this new kind of attack when choosing CP-ABE schemes to deploy in practice.

4.2 AKL Attack From a Single Malicious User

4.2.1 AKL Attack on Waters’ Scheme

We first recall the Waters’ scheme [15] at PKC’11 as follows.

• Setup(λ,ℬ): Let λ be a security parameter, N=|ℬ| be the maximal number of attributes in the system, and let (p,G,GT,e(⋅,⋅)) be a bilinear group system. First, pick a random generator g∈G, random scalars a,α∈Zp, and then calculates ga,gα. Next, generateN group elements in G associated with N attributes in the system h1,…,hN. The master secret key is MSK=gα. The public parameters are param=(g,ga,e(g,g)α,h1,…,hN).

• Extract(i,ℬi,MSK,param): The set of attributes of user i is ℬi. Pick randomly r∈Zp, and compute the secret key for user i as di=(d0,d0′,{di}i∈ℬi), where: d0=gα⋅ga⋅r,d0′=gr,{di=hir}i∈ℬi.

• Encrypt(ℳ,(M,ρ)∈(Zpℓ×ℓ′,ℱ([ℓ]→[N])),param): First pick k←$Zp, and compute: C0=ℳ⋅e(g,g)kα,C0′=gk, then choose a random vector v→=(k,y2,…,yℓ′)∈Zpℓ′. For i=1,…,ℓ, compute λi=v→⋅Mi, where Mi is the i-th row of M. Computes:

Ci=ga.λihρ(i)−k,i=1,…,ℓ.

Finally, the ciphertext CP=(C0,C0′,…,Cℓ) is output.

• Decrypt(CP,di,param): First parse the ciphertext CP as (C0,C0′,…,Cℓ), then find the set of attributes 𝒜⊂ℬi that satisfies the access policy (M,ρ). Let I={i:ρ(i)∈𝒜}, find the constants {βi∈Zp}i∈I such that ∑i∈Iβi⋅Mi=(1,0,…,0), where Mi is the i-th row of the matrix M. Next, compute

e(∏i∈ICi−ωi,d0′)⋅e(C0′,d0∏i∈Idρ(i)−ωi)=e(g,g)α⋅k.

Finally, return ℳ=C0e(g,g)kα.

TheAKL attack. For simplicity, we assume that several users possess the common set of attributes Ai1,…,Aik. We will show that a malicious user u can publish a part of her secret key related to this set of attributes and remain anonymous. To this aim, she randomly chooses r′ and, based on her secret key, computes a new sub-key d corresponding to new randomness r+r′:

d0=gα⋅ga⋅(r+r′),d0′=gr+r′,{di=hir+r′}i=i1,…,ik

and then publishes d to the public domain.

Correctness. It is straightforward to see that d=(d0,d0′,{di}i=i1,…,ik) is a secret key corresponding to the attribute set Ai1,…,Aik. In addition, it is obvious that any user can produce d (assume t such users) who possesses at least the attribute set Ai1,…,Aik. Hence, any polynomial time trace algorithm cannot determine who generates d with a correctness probability larger than 1/t.

Performance. To compute d, user needs to compute k+2 exponential operations and k+2 multiplicative operations. Hence, the complexity of cryptanalysis depends on each specific case of AKL attack. In the general case, the complexity of the AKL attack is T+2 exponential operations and T+2 multiplicative operations, where T is the number of attributes in the common set of attributes, and therefore it is very practical.

4.2.2 AKL Attack on Riepel and Wee’s Scheme

We first recall Riepel and Wee’s CP-ABE scheme at CCS’22 [22] as follows.

• Setup(λ,ℬ): Let λ be a security parameter, N=|ℬ| and (p,G,G~,GT,g,g~,e) be a bilinear group system, and ℋ:[N+1]→G be a hash function. Pick α∈Zp randomly.

The master secret key is MSK=α. The public parameters are

param=(p,G,G~,GT,g,g~,e,e(g,g~)α,ℋ).

• Extract(i,ℬi,MSK,param): The set of attributes of user i is ℬi. The algorithm picks randomly a scalar r∈Zp, and computes the secret key for user i as

di=(d0,d0′,{du}u∈ℬi)

where d0=gα⋅ℋ(N+1)r,d0′=g~r,{du=ℋ(u)r}u∈ℬi.

• Encrypt((M,π)∈(Zpℓ×ℓ′,ℱ([ℓ]→ℬ)),param): Let ρ(i)=|{z|π(z)=π(i),z≤i}|, and τ=maxi∈[ℓ]ρ(i) corresponding to maximum number of times an attribute is used in M.

Randomly pick k←$Zp,v→=(k,y2,…,yℓ′)←$Zpℓ′,w→=(w1,w2,…,wτ)←$Zpτ, then computes:

ct1=g~k,ct2,j=g~wj

for j∈[τ]. For i∈[ℓ], compute λi=v→⋅Mi, where Mi is the i-th row ofM. Computes:

ct3,i=ℋ(N+1)λi⋅ℋ(π(i))wρ(i),i=1,…,ℓ

Finally, output the ciphertext CP=(ct1,(ct2,j)j∈[τ], (ct3,i)i∈[ℓ]) along with a description of (M,π), and session key K=e(g,g~)k⋅α.

• Decrypt(CP,di,param): First parse the ciphertext CP as (ct1,(ct2,j)j∈[τ],(ct3,i)i∈[ℓ]), then find the attribute set 𝒜⊆ℬi which satisfies the access policy (M,π). Let I={i:π(i)∈𝒜}, find {βi∈Zp}i∈I such that ∑i∈Iβi⋅Mi=(1,0,…,0), where Mi is the i-th row ofM. Next, compute the session key: K=e(d0,ct1)⋅∏j∈[τ]e(∏i∈I,ρ(i)=j(dπ(i))βi,ct2,j)e(∏i∈I(ct3,i)βi,d0′).

The AKL Attack. For simplicity, we assume that there are several users {A1,…,At} who possess the common set of attributes Pℬi′={u1,…,uk}. To build the AKL attack, a malicious user 𝒜i,1≤i≤t, asks secret key corresponding to this set of attributes to get

d0=gα⋅ℋ(N+1)r,d0′=g~r,{du=ℋ(u)r}u∈ℬi′

and then randomly chooses r′ to compute a new secret key d corresponding to new randomness r+r′:

d=(d0=gα⋅ℋ(N+1)r+r′,d0′=g~r+r′,{du=ℋ(u)r+r′}u∈ℬi′).

Finally, she publishes d to the public domain.

Correctness. It is easy to verify that d=(d0,d0′,{du}u∈ℬi′) is a secret key corresponding to attribute set ℬi′. In addition, d can be produced by any user (assume t such users) who possesses at least the attribute set ℬi′. Hence, any polynomial time trace algorithm cannot determine who generates d with a correctness probability larger than 1/t.

Performance. To compute d, user needs to compute k+2 exponential operations and k+2 multiplicative operations (k is the cardinality of the attribute set ℬi′). Hence, the complexity of cryptanalysis depends on each specific case of AKL attacks. In the general case, the complexity of the AKL attack is T+2 exponential operations and T+2 multiplicative operations, where T is the number of attributes in the common set of attributes; it thus is very practical.

To conclude, we name several other CP-ABE schemes that are also susceptible to the AKL attack from a single malicious user such as [23,24,27,28].

4.3 AKL Attack from a Group of Malicious Users

This section describes the AKL attack from a group of malicious users on several important CP-ABE schemes. Regarding CP-ABE scheme, there is an elegant generic framework to construct adaptively secure CP-ABE schemes introduced in [18–21,29]. This framework also leads to CP-ABE schemes with short ciphertext size and efficient decryption time. We will show that all these schemes are susceptible to the AKL attack from a group of malicious users.

We consider the AKL attack on Chen et al.’s CP-ABE scheme [29] (at Appendix B.2, similarity for other schemes [18–21]), for a given parameter k (see discussion in [29] and below), the secret key of user u, who possesses the attributes (1,…,m), is of the following form:

K0=gB.ru,K1=gA1.ru,…,Km=gAm.ru,Kℓ+1=gk+C.ru,

where A1,…,Am, B, C∈Zpk+1×k are matrices, k ∈Zpk×1 is a vector, ℓ is the number of attributes in the system (ℓ≥m). Note that all A1,…,Am, Am+1,…,Aℓ, B, C, k are in the master key (more precisely, in their scheme C=VB, and each matrix Ai=WiB,i=1,…,ℓ), ru∈Zpk×1 is a random vector chosen for user u. We use the same group vector notation as in [29], which means that the first row of the matrix Ai is Ai,1=(ai,1,1,…,ai,1,k), ru=(ru,1,…,ru,k) and the group element K1,1=gai,1,1.ru,1+⋯+ai,1,k.ru,k. Note also that K1=(K1,1,…,K1,k+1).

Observer that if a single user wants to produce an AKL attack as in the case of Riepel and Wee’s CP-ABE scheme above, she needs to randomize the vector ru by first choosing a random element t∈Zp and then trying to derive a new decryption key K′ associated to a new random vector ru′=t.ru. However, there are two problems:

1. First, she cannot randomize Kℓ+1=gk+C.ru. Note that k is in the master key.

2. Second, assume that she chooses a random element t∈Zp and randomizes Kit=gdi for some di, it becomes feasible for the Tracing algorithm to trace back Ki. Since, given gdi, there is only one Ki satisfying Kit=gdi for some t∈Zp.

The above problems lead to the fact that the AKL attack from a single malicious user cannot straightforwardly apply in these schemes. However, we show that the AKL attack from a group of malicious users can be applied in these schemes.

More precisely, assume that q users u1,…,uq who possess the common set of attributes (1,…,m) secretly collude. As far as q≥2, an AKL attack from a group of malicious users can be realized. Indeed, each user ui,i=1,…,q, chooses a random element ti∈Zp such that ∑i∈[q]ti=1. They then compute the derived secret key K′=(K0′,K1′,…,Km′,Kℓ+1′)=(gd0,gd1,…,gdm,gdℓ+1) as follows:

K0′=∏i∈[q]Kui,0ti,K1′=∏i∈[q]Kui,1ti,…,Km′=∏i∈[q]Kui,mti,Kℓ+1′=∏i∈[q]Kui,ℓ+1ti.

Finally, they publish K′ to the public domain.

Correctness. It is easy to verify that the derived secret key K′ is in right form with a random vector r′=∑i∈[q]ti⋅rui where rui is a random vector associated to secret key of user ui. We see that Kℓ+1′=gk+C.r′ is in right form since ∑i∈[q]ti=1. That means the first problem above is solved.

Given K′ associated with a random vector r′, it is easy to see that any combination of q users where q is bigger than the length of the vector r′ (denoted k) can lead to r′, as one easily solves equations k with variables q (where k is a system parameter giving the size of the vectors and matrices and q is the number of colluding users). Therefore, if there are more than k users (q≥k) sharing the same m attributes, the tracking algorithm cannot exactly identify who publishes K′ in the public domain. That means the second problem above is solved. More precisely, assume that q≥k×t then we have at least t different groups of users who can produce K′, note that we only need k malicious users in q users to mount the AKL attack. In the context of the AKL attack, we can say that the scheme is susceptible to the AKL attack since any polynomial time trace algorithm cannot determine who generates K′ with a correctness probability larger than 1/t.

To fight against the aforementioned attack, the parameter k (fixed at the setup phase) needs to be large enough to ensure that no more than k users share the same m attributes. In these schemes, the key and ciphertext sizes are linear in k2⋅ℓ and k⋅ℓ, respectively. Note that ℓ is the length of a one-use linear secret-sharing matrix. Therefore, their scheme is completely impractical if k is large. In fact, when compared to other schemes, the competitive case of these schemes is when k=1.

Performance. Consider K0′=∏i∈[q]Kui,0ti, each Kui,0 is a vector of k+1 elements. Therefore, to compute K0′ we need (k+1)q exponential operations and (k+1)q multiplicative operations. Similarity for other terms K1′,…,Km′,Kℓ+1′. Hence, to compute K′=(K0′,K1′,…,Km′,Kℓ+1′) we need (m+2)(k+1)q exponential operations and (m+2)(k+1)q multiplicative operations, where m is the number of attributes in the common set of attributes, q is the number of colluded users (note that q≥k), and k is the system parameter. As discussed above, compared to other schemes, the competitive case of these schemes is when k=1, which means it is efficient to build an AKL attack from a group of malicious users.

4.4 Discussion on Potential Countermeasures to the AKL Attack and Performance Evaluation

We observe that AKL attacks directly apply on CP-ABE schemes whose secret keys have the following two properties:

• First, the secret key consists of sub-key components, each of which corresponds to an attribute.

• Second, these sub-key components can be re-randomized by themselves or combined to be re-randomized.

We thus cannot apply directly AKL attacks on CP-ABE schemes, such as [30–33], whose secret keys do not have the aforementioned two properties. Regarding CP-ABE schemes that are susceptible to AKL attacks, to modify these schemes so that AKL attacks cannot be applied directly to them, we need at least to change the secret key structure in these schemes to ensure that whose secret keys do not have the aforementioned two properties. This will lead to changing the entire structure of each scheme (including encryption and decryption algorithms) and the corresponding security proof of each scheme. This is a large and challenging workload. We consider this as an open problem for future research.

Regarding the success rate of AKL attack, it is straightforward to see that the AKL attack from a single malicious is considered successful if the number of users (denotes t) sharing the same common set of attributes is large enough (at least t≥2) and there are at least one malicious user in such t users. On the other hand, the AKL attack from a group of malicious users is considered successful if the number of users (in this case denotes q) sharing the same common set of attributes is large enough (at least q≥2k) and there are at least k colluded malicious users in such q users. Note that if k=1, the AKL attack from a group of malicious users is exactly the AKL attack from a single malicious user.

We exploit the AKL attack on schemes [15,22,29] and evaluate its effectiveness based on attack success rate, computational complexity and practicality, as shown in Table 1. The attack succeeds in [15] and [22] when there is at least one malicious user and the number of users sharing the same common set of attributes is at least 2 (t≥2), whereas in [29], it requires at least k colluded malicious users and at least (q≥2k) users sharing the same common set of attributes. The computational complexity of the AKL attack on [15] and [22] is (T+2)E+(T+2)M which is quite efficient. In contrast, attacking [29] is significantly more complex, with a cost of 2q(k+1)(T+2)E+2q(k+1)(T+2)M. In terms of practicality, references [15] and [22] allow both single AKL and group AKL, whereas reference [29] mitigates single-user attacks but remains vulnerable to group-based one.

5 Conclusion

This work considers the attribute collusion attack on several ECC-based CP-ABE schemes. Then, we define a novel type of insider attack, called the anonymous key-leakage attack or AKL. This attack can be applied to many important existing pairing-based CP-ABE schemes. We argue that even though these pairing-based CP-ABE schemes are still secure in their security model, we should consider the AKL attack when choosing these schemes to deploy in practice.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Viet Cuong Trinh; methodology, Viet Cuong Trinh; investigation, Phi Thuong Le; resources, Viet Cuong Trinh; writing—original draft preparation, Phi Thuong Le; writing—review and editing, Huy Quoc Le, Viet Cuong Trinh; visualization, Phi Thuong Le, Huy Quoc Le; supervision, Viet Cuong Trinh; project administration, Viet Cuong Trinh. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AABHE | Adaptive attribute-based honey encryption |

| ABE | Attribute-based encryption |

| AKL | Anonymous key-leakage |

| CP-ABE | Ciphertext-policy ABE |

| ECC | Elliptic curve cryptography |

| IBE | Identity-based encryption |

References

1. Sahai A, Waters B. Fuzzy identity-based encryption. In: Advances in cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2005. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2005. Vol. 3494. [Google Scholar]

2. Bethencourt J, Sahai A, Waters B. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption. In: 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP ’07); 2007; Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

3. Galbraith SD, Paterson KG, Smart NP. Pairings for cryptographers. Discrete Appl Math. 2008;156(16):3113–21. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2007.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yao X, Chen Z, Tian Y. A lightweight attribute-based encryption scheme for the Internet of Things. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2015;49(1):104–12. doi:10.1016/j.future.2014.10.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ding S, Li C, Li H. A novel efficient pairing-free CP-ABE based on elliptic curve cryptography for IoT. IEEE Access. 2018;6:27336–45. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2836350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang Y, Chen B, Li L, Ma Q, Li H, He D. Efficient and secure ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption without pairing for cloud-assisted smart grid. IEEE Access. 2020;8:40704–13. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2976746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sowjanya K, Dasgupta M. A ciphertext-policy attribute based encryption scheme for wireless body area networks based on ECC. J Inf Secur Appl. 2020;54(C):102559. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2020.102559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Herranz J. Attribute-based encryption implies identity-based encryption. IET Inf Secur. 2017;11(6):332–337. doi:10.1049/iet-ifs.2016.0490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Boneh D, Papakonstantinou PA, Rackoff C, Vahlis Y, Waters B. On the impossibility of basing identity based encryption on trapdoor permutations. In: 2008 49th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science; 2008; Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

10. Papakonstantinou P, Rackoff C, Vahlis Y. How powerful are the DDH hard groups? Cryptology eprint Archive. 2012;2012/653:1–31. [Google Scholar]

11. Gaborit P, Hauteville A, Phan DH, Tillich JP. Identity-based encryption from codes with rank metric. In: Advances in cryptology–CRYPTO 2017. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. Vol. 10403. [Google Scholar]

12. Döttling N, Garg S. Identity-based encryption from the diffie-hellman assumption. J ACM. 2021;68(3):14. [Google Scholar]

13. Izabachène M, Prabel L, Roux-Langlois A. Identity-based encryption from lattices using approximate trapdoors. In: Information security and privacy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. Vol. 13915. [Google Scholar]

14. Herranz J. Attacking pairing-free attribute-based encryption schemes. IEEE Access. 2020;8:222226–32. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3044143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Waters B. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption: an expressive, efficient, and provably secure realization. In: Public key cryptography–PKC 2011. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2011. Vol. 6571. [Google Scholar]

16. Rouselakis Y, Waters B. Practical constructions and new proof methods for large universe attribute-based encryption. In: Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2013; New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

17. Hohenberger S, Waters B. Attribute-based encryption with fast decryption. In: Public-key cryptography–PKC 2013. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. Vol. 7778. [Google Scholar]

18. Attrapadung N. Dual system encryption via doubly selective security: framework, fully secure functional encryption for regular languages, and more. In: Advances in cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2014. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. Vol. 8441. [Google Scholar]

19. Wee H. Dual system encryption via predicate encodings. In: Theory of cryptography. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. Vol. 8349. [Google Scholar]

20. Agrawal S, Chase M. FAME: fast attribute-based message encryption. In: Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2017; New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

21. Agrawal S, Chase M. Simplifying design and analysis of complex predicate encryption schemes. In: Advances in cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2017; Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2017. Vol. 10210. [Google Scholar]

22. Riepel D, Wee H. FABEO: fast attribute-based encryption with optimal security. In: Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2022; New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

23. Shen H, Zhou J, Wu G, Zhang M. Multi-keywords searchable attribute-based encryption with verification and attribute revocation over cloud data. IEEE Access. 2023;11:139715–27. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3334733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Venema M, Alpár G. GLUE: generalizing unbounded attribute-based encryption for flexible efficiency trade-offs. In: Public-key cryptography–PKC 2023. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. Vol. 13940. [Google Scholar]

25. Siyal R, Jun L, Elaffendi M, Asim M, Iftikhar S, Alnashwan R, et al. Adaptive attribute-based honey encryption: a novel solution for cloud data security. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(2):2637–64. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.058717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Luo F, Al-Kuwari S. Generic construction of black-box traceable attribute-based encryption. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2023;11(1):942–55. doi:10.1109/TCC.2021.3121684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Rouselakis Y, Waters B. Efficient statically-secure large-universe multi-authority attribute-based encryption. In: Financial cryptography and data security. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2015. Vol. 8975. [Google Scholar]

28. Malluhi QM, Shikfa A, Trinh VC. A ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption scheme with optimized ciphertext size and fast decryption. In: ASIA CCS, 2017—Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2017; New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

29. Chen J, Gay R, Wee H. Improved dual system ABE in prime-order groups via predicate encodings. In: Advances in cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2015. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2015. Vol. 9057. [Google Scholar]

30. Canard S, Phan DH, Trinh VC. Attribute-based broadcast encryption scheme for lightweight devices. IET Inf Secur. 2018;12(1):52–59. doi:10.1049/iet-ifs.2017.0157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Attrapadung N, Hanaoka G, Yamada S. Conversions among several classes of predicate encryption and applications to ABE with various compactness tradeoffs. In: Advances in cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2015. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2015. Vol. 9452. [Google Scholar]

32. Attrapadung N. Dual system encryption framework in prime-order groups via computational pair encodings. In: Advances in cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2016. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2016. Vol. 10032. [Google Scholar]

33. Le HQ, Le PT, Trinh ST, Susilo W, Trinh VC. Levelled attribute-based encryption for hierarchical access control. Comput Stand Interfaces. 2025;93(2):103957. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2024.103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Open Access

Open Access

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools