Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Electronic Structure Computations and Optical Spectroscopy Studies of ScNiBi and YNiBi Compounds

M.N. Mikheev Institute of Metal Physics of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IMP UB RAS), S. Kovalevskaya str. 18, Ekaterinburg, 620108, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Alexey V. Lukoyanov. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4085-4095. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065091

Received 03 March 2025; Accepted 22 April 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

The work presents the electronic structure computations and optical spectroscopy studies of half-Heusler ScNiBi and YNiBi compounds. Our first-principles computations of the electronic structures were based on density functional theory accounting for spin-orbit coupling. These compounds are computed to be semiconductors. The calculated gap values make ScNiBi and YNiBi valid for thermoelectric and optoelectronic applications and as selective filters. In ScNiBi and YNiBi, an intense peak at the energy of −2 eV is composed of the Ni 3d states in the conduction band, and the valence band mostly contains these states with some contributions from the Bi 6p and Sc 3d or Y 4d electronic states. These states participate in the formation of the indirect gap of 0.16 eV (ScNiBi) and 0.18 eV (YNiBi). Within the spectral ellipsometry technique in the interval 0.22–15 μm of wavelength, the optical functions of materials are studied, and their dispersion features are revealed. A good matching of the experimental and modeled optical conductivity spectra allowed us to analyze orbital contributions. The abnormally low optical absorption observed in the low-energy region of the spectrum is referred to as the results of band calculations indicating a small density of electronic states near the Fermi energy of these complex materials.Keywords

Nowadays, computational modeling of materials is the foremost leading technique for discovering and engineering novel multifunctional materials [1]. Among such materials, those containing rare-earth metals can provide exceptional properties and further applications [2]. The ternary half-Heusler XTZ compounds, with X, T—transition elements; Z usually denotes p element, crystallized in MgAgAs-type structure considered as filling up of T atoms into the rock-salt structure of XZ atoms. These alloys attract attention owing to diverse magnetic properties [3], colossal magnetocaloric and magnetoresistive effects [4,5], field-induced metal-semiconductor transition [6], coexisting magnetism and superconductivity [7], corrosion resistance [8], and more. The unique combination of electronic, magnetic, thermal, and mechanical characteristics in half-Heuslers makes them promising materials for numerous technological applications, ranging from spintronics [9], optoelectronics [10], piezoelectricity [11] to topological insulators [12,13]. The prospects for the practical use of such alloys are also associated with their valuable thermoelectric characteristics, which make it possible to convert thermal energy into electrical efficiently [14,15]. The high thermoelectric power factor of such materials is related to the major characteristics of their electronic structure—the presence of the narrow energy semiconducting gaps localized near the Fermi level (EF) [16–18]. The origin of such anomalies, as shown in the calculations of electronic spectra, is related to the specificity of the p-d bands hybridization. The thermoelectric properties of XTZ compounds can be improved by changing the concentration of doping components and sample defects [19–21].

The paramagnetic compounds ScNiBi and YNiBi are typical representatives of this extensive family. Experimentally, only a few papers studied the properties of these materials. The ScNiBi single crystal was identified as a hole-dominant semiconductor with positive linear magnetoresistance [22]. The size of the energy gap, determined from the temperature dependence of the electrical resistance, is 83.7 meV, i.e., somewhat less than a theoretical estimate [23,24]. The electrical transport and thermoelectric characteristics of YNiBi were measured and evaluated from 10 to 925 K [25]. This alloy is a promising p-type thermoelectric compound because of its small lattice thermal conductivity with the max. Power factor gaining 13.3 μWcm−1K−2 at 485 K. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) combined with DFT computations showed that both compounds exhibit properties typical of topologically nontrivial half-Heusler alloys [26]. The crystalline properties of both compounds, as well as the method of their synthesis, are described in detail in [27]. Their structural [28,29], mechanical [30], electronic [31], magnetic, excited states, elastic, and thermal [32] properties were investigated by performing first-principles calculations within the framework of various computational schemes [33–35]. The sizes of the band gap in both compounds, calculated in these works, with some difference, located nearby of 0.158–0.314 eV (ScNiBi: 0.286 [23], 0.158 [24], 0.256 [29], 0.22 [33], 0.185 [35] eV; YNiBi: 0.314 [23], 0.166 [24], 0.32 [28], 0.266 [29], 0.19 [32], 0.205 [35] eV). Computed optical properties of ScNiBi and YNiBi [35] revealed interband light absorption, as well as spectral and dielectric characteristics over a wide energy range, were determined.

Helpful data on the electronic properties of ScNiBi and YNiBi could be gained from a joint experimental study of their optical characteristics and calculations of first-principles band spectra. Optical spectroscopy is well known as a convenient and sensitive method for investigating the band structure of intermetallic compounds in the vicinity of the Fermi energy. The explanation of the experimental results, taking into account the first-principles calculations, allows for a more comprehensive analysis and also to assess the validity of the computation method. The results of such a combined experimental and theoretical study are reported in this paper. In optical studies carried out in a wide range of wavelengths using the ellipsometric method, the energy dependencies of several spectral characteristics were obtained. Spectroscopic ellipsometry uses the change of polarization state of incident light on reflection. This change is closely connected with the dielectric function of an investigated matter. As far as we know, no studies of this kind have been published on these semiconducting compounds.

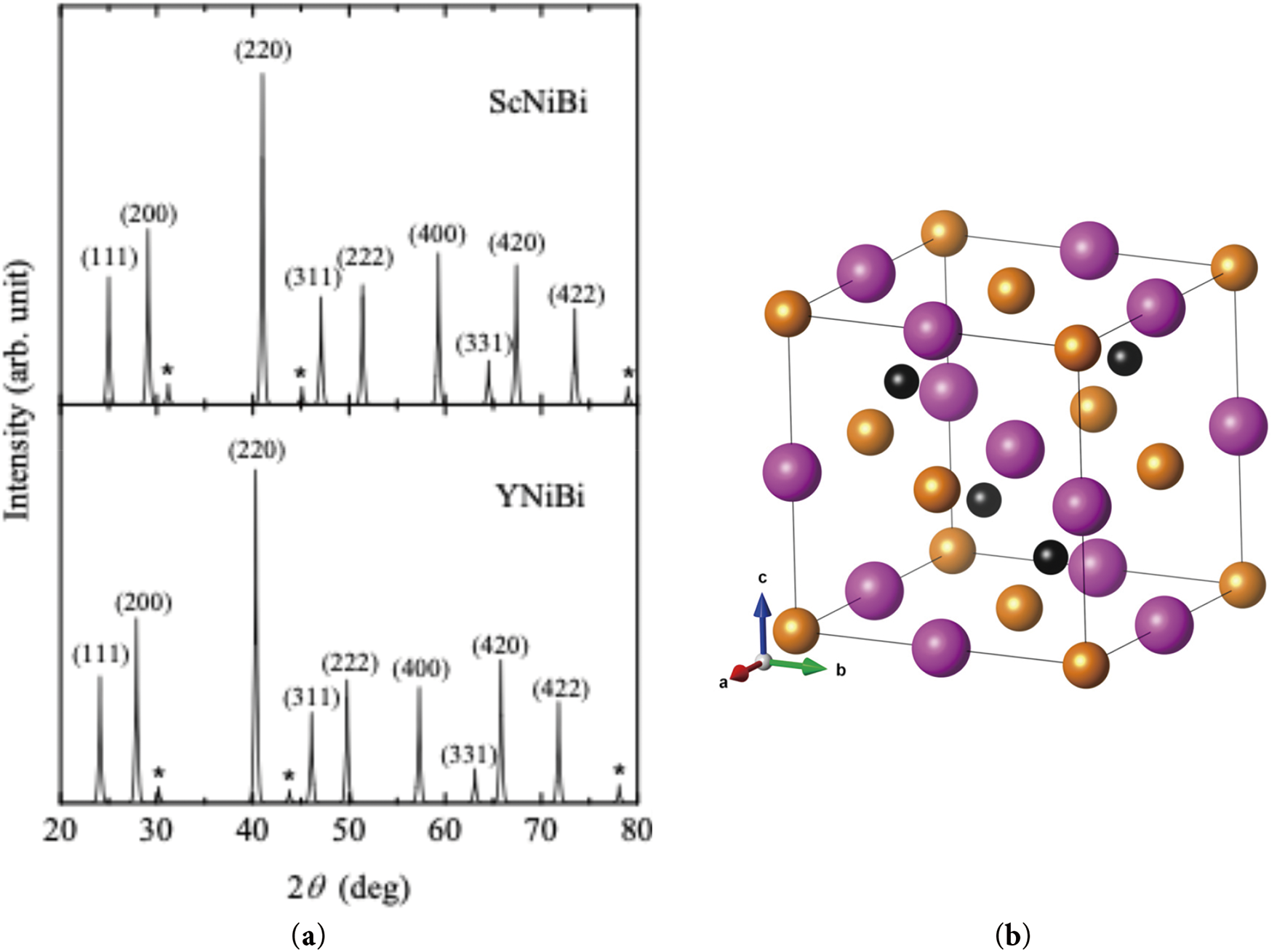

Polycrystalline samples ScNiBi and YNiBi were prepared by arc-melt technique which was previously used for the synthesis of these materials [25,27]. The melting process of high-purity (at least 99.9%) metals in a ratio of 1:1:1 took place in an atmosphere of purified argon. The initial bismuth content was increased by 6% to cover for its evaporation during the melting. The resulting ingots were sealed under vacuum into silica tubes and annealed for 5 days at 800 C to homogenize the samples. Powder X-ray diffraction was performed using a high-resolution PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with Cu Kα monochromator (λ0 = 1.54056 Å) and scanning step of 0.013° in angles 20°–80°. The analysis of the phase composition and calculation of the lattice parameters were performed using the Rietveld method with the FullProf software, see Fig. 1. The study showed that the crystal structure of both compounds consists of almost 98% cubic MgAgAs-type phase

Figure 1: Powder diffraction patterns (a) of ScNiBi and YNiBi. The asterisk corresponds to the impurity signals. Crystal structure (b) of ScNiBi compound with Sc—orange, Ni—black, and Bi—magenta atoms

The optical properties of the ScNiBi and YNiBi alloys were experimentally measured using the Beattie ellipsometric technique with a rotating analyzer measuring the phase shifts and amplitudes of reflected light waves of s and p polarizations [36]. Using these parameters provides the possibility to determine the optical constants of the materials—refractive indices n(E) and extinction coefficients k(E), here E—the light wave energy. Several other optical characteristics, namely the complex permittivity ε(E) = ε1(E) − iε2(E) that describes the linear response of the medium to incident electromagnetic radiation, reflectivity R(E), optical conductivity σ(E) = ε2ω/4π (ω—frequency of the light) and the electron energy loss function can be calculated from n and k. Measurements were performed at room temperature in the wavelength range λ = 0.22–15 μm (E = 0.083–5.64 eV) and covered the ultraviolet (UV), visible, and infrared (IR) spectral intervals.

All electronic structure computations were conducted using so-called first-principles methods in density functional theory (DFT). The functional was chosen to be generalized gradient approximation (GGA) per Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof form (PBE) [37]. For pseudopotentials [38], ultrasoft full relativistic ones account for spin-orbit coupling (SOC) in the considered ScNiBi and YNiBi compounds. This approach provides reliable electronic structure and other physical characteristics [39]. The computations were done in the Quantum ESPRESSO software [40], pseudopotentials were chosen from its libraries, with valence states: 3s, 4s, 3p, 3d for Sc; 4s, 5s, 4p, 5p, 4d for Y; 4s, 4p 3d for Ni and 6s, 6p, 5d for Bi. The wave functions were presented based on plane waves. The reciprocal space was divided into a grid of 12 × 12 × 12 k-points. It is enough for a good convergence of the results with standard energy and other thresholds. Kinetic energy cutoffs for the wavefunctions and the charge density were chosen as 70 and 700 Ry. It was found to be enough for the self-consistency of the results. When constructing densities of states, the value of the Gaussian broadening was chosen to be 0.01 Ry for the density peaks.

3 Electronic Structure and First-Principles Calculations

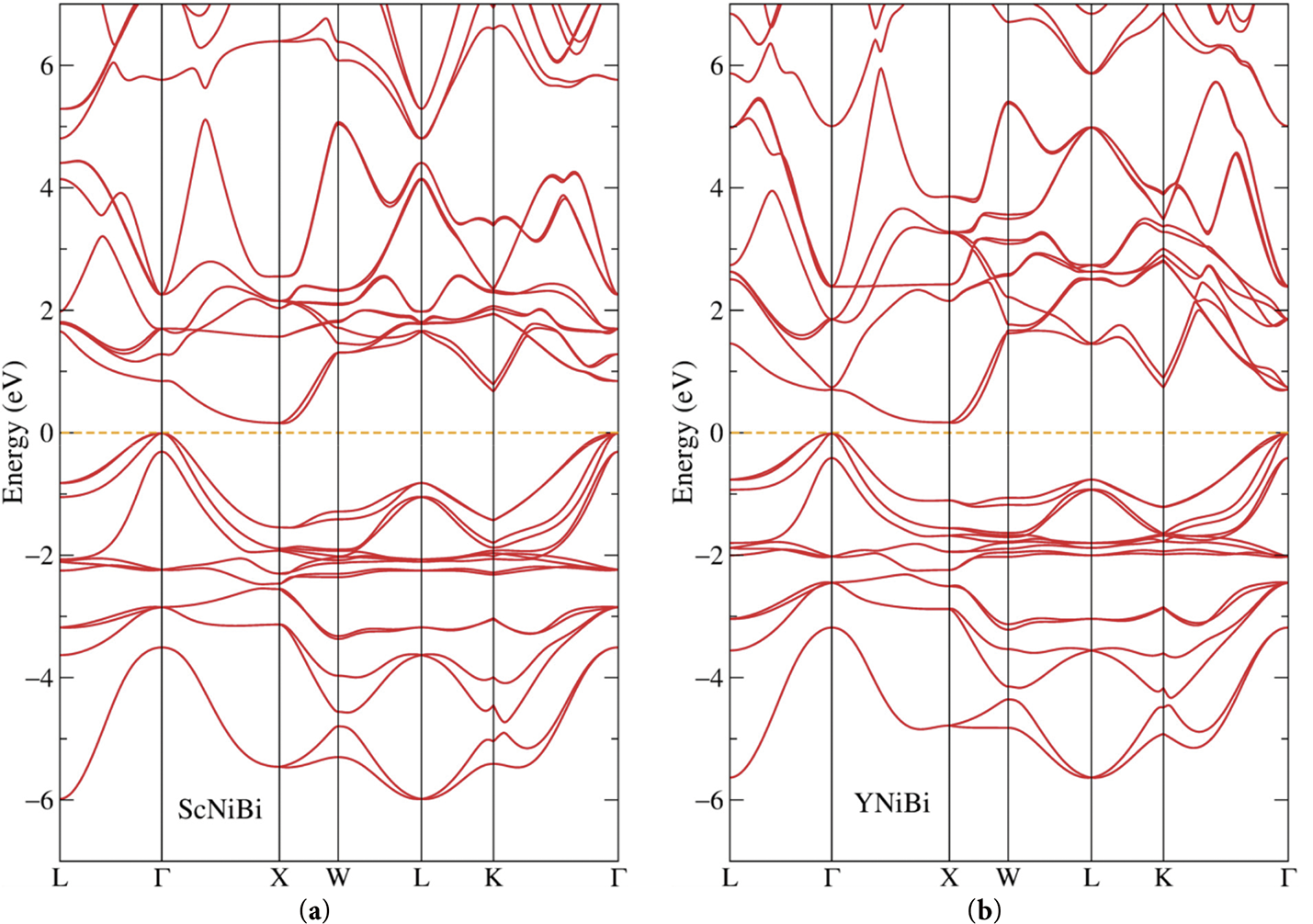

In Fig. 2, one can see the band structures of the ScNiBi and YNiBi compounds, the DFT calculated considering spin-orbit coupling. A pronounced feature that characterizes ScNiBi as a semiconductor, namely, the band gap can be seen at the Fermi level at zero energy demonstrated with the orange dashes. The gap is indirect with the smallest value between Г and X, the value of the band gap was computed as 0.16 eV in our study. One can also notice a high number of localized bands in the vicinity of –2 eV which would produce a peak with a high density of the occupied nickel states as we can see below from the projected densities of states. From Fig. 2, one can observe that the bands of YNiBi are similar to the structure of ScNiBi in some regards. The lowest part of the valence band is shifted above in energy relative to the ScNiBi compound. It makes the valence band in YNiBi more localized. The band gap in the YNiBi compound is also present. It is indirect with a slightly higher value of 0.18 eV. The localized bands at –2 eV are also present in this compound because it contains nickel.

Figure 2: Band structure of the semiconductor (a) ScNiBi, (b) YNiBi alloys

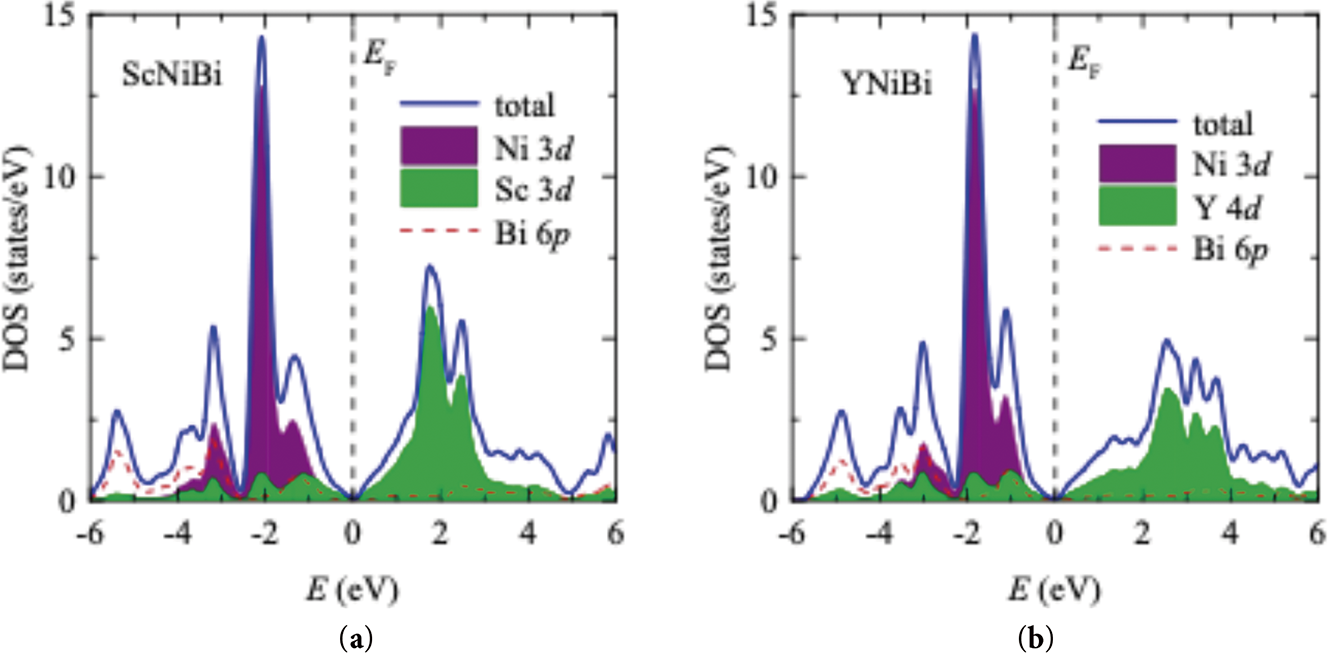

The densities of states (DOS) for both materials are depicted in Fig. 3. In ScNiBi, there is an intense peak at the energy of –2 eV. This peak is composed of the Ni 3d states. The valence band mostly contains these states with some contributions from the Bi 6p and Sc 3d electronic states. The scandium 3d states are mainly unoccupied excited states and in the conduction band. The total density of states around the Fermi level is very low. It is a manifestation of a narrow gap of 0.16 eV partially covered by a broadening procedure of a DOS plot but seen from the band structure in Fig. 2. From Fig. 3, we can also tell that the states of scandium are dominant around the Fermi. The densities of states of YNiBi, also shown in Fig. 3, are similar to those calculated for the semiconductor ScNiBi compound. There is also an intense peak at –2 eV from the Ni 3d states. It corresponds to the localized bands in the compound bands. The Y 4d electronic states exhibit the same behavior as the Sc 3d states being mostly unoccupied and forming the conduction band. As we guessed from its band structure, the valence band in the semiconductor YNiBi compound is narrower in the energy spectrum with the conduction band being the opposite. It is more spread out with the less intense peaks from the Y 4d states.

Figure 3: Distribution of the total and partial densities of electronic states of (a) ScNiBi and (b) YNiBi compounds

4 Dielectric Functions and Optical Conductivity

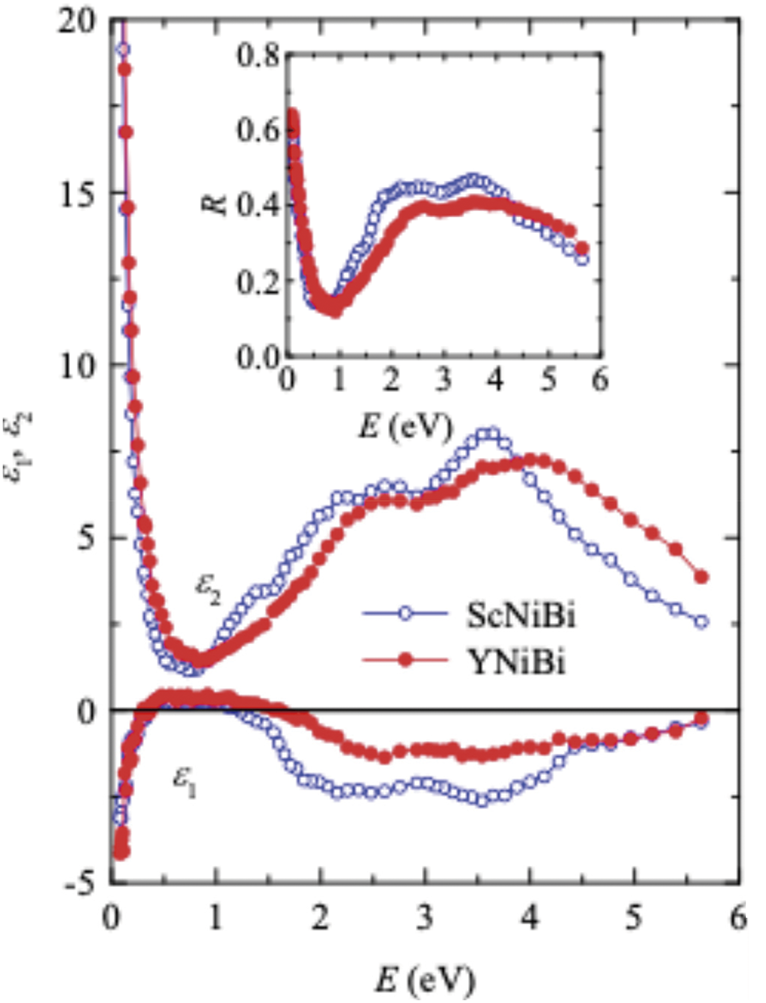

The real ε1(E) and imaginary ε2(E) components (as functions of energy) of the permittivity of half-Heusler ScNiBi and YNiBi compounds are shown in Fig. 4. The real ε1(E) part describes the intensity of the electrostatic interaction between charges (polarizability of material) and ε2(E) is related to the material’s light absorption. In IR less ~0.6 eV, the real dielectric functions of both alloys decrease and have negative values which is explained by the fact that the compounds reflect the incident radiation, and the materials demonstrate a metallic behavior. As the light energy increases, the ε1(E) values become positive, indicating a recession of the metallic properties of the compounds. In the visible region, at E > ~1.5 eV, the real dielectric functions become negative again, accompanied by an increase in reflectivity. In Fig. 4, the imaginary components ε2(E) and reflectivity R(E) are plotted for both alloys. The reflectivity R(E), defined relative to the unit, represents the proportion of reflected light to incident light. At low energies, these characteristics abruptly increase. It is also typical of a conductive medium. It is important to note that relatively low R and |ε1| in the IR interval show a drop in the metallic properties of ScNiBi and YNiBi. For comparison in good metals at these energies, the |ε1| value is two to three orders of magnitude higher, and the reflectivity is close to unity [41,42]. As the frequency of light grows, several peaks related to quantum light absorption are seen on these curves in the same energy intervals.

Figure 4: Experimental results for reflectivity R and dielectric functions ε1 and ε2 as functions of energy

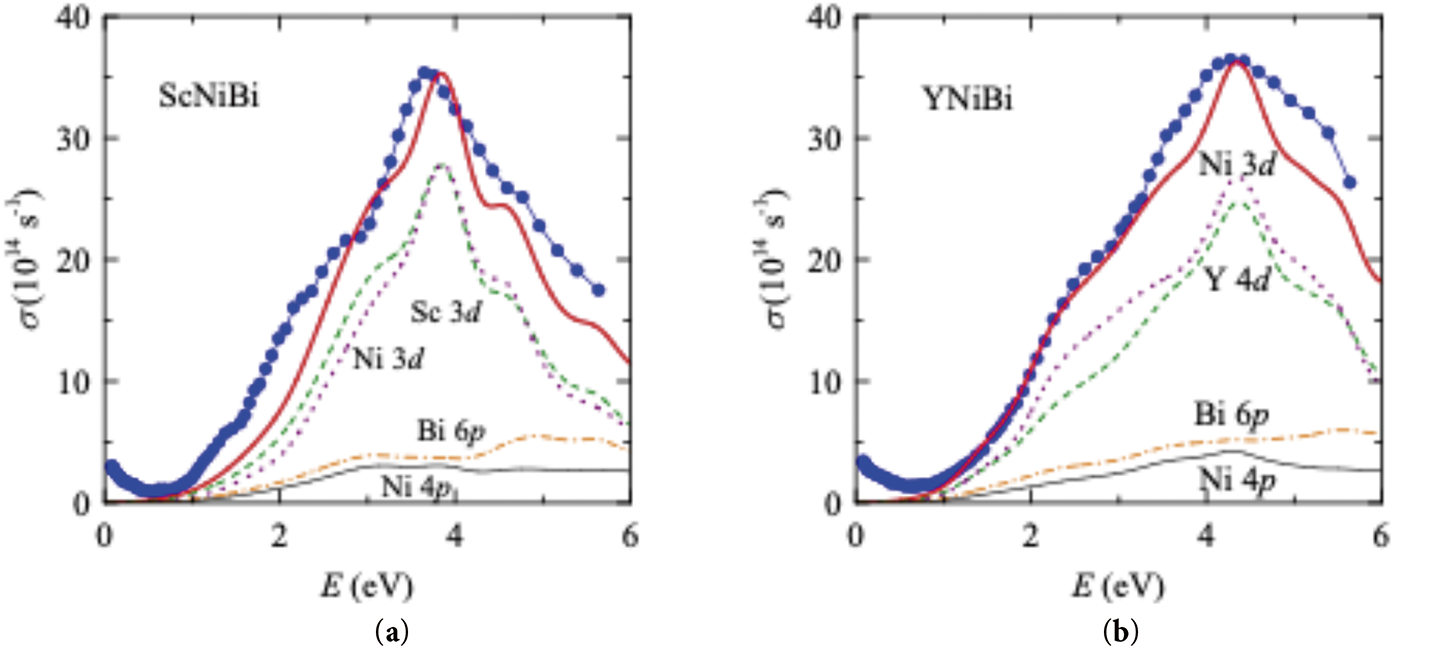

The experimental energy dependences of the optical conductivities σ(E) of ScNiBi and YNiBi are drawn by dots, see Fig. 5. This function, in contrast to the static conductivity, depends on both the states at the EF, and on its values over the entire range of energies. In low energies, where the values of σ(E) are small, a broad minimum below 1 eV is observed on both curves. As the photon energy increases (visible and UV regions), wide bands of interband absorption corresponding to electronic transitions are indicated in the submitted σ(E) dependences. For ScNiBi and YNiBi, these bands have a similar shape, and their maxima are at energies of 3.7 eV (ScNiBi) and 4.3 eV (YNiBi). The structure of the σ(E) dependencies of both materials corresponds to the spectra obtained in theoretical calculations [35]. The origin of these transitions from the occupied valence states to the empty conduction states produces the named maxima. For this purpose, we compared the experimental curves σ(E) with the theoretical interband conductivity σib(E) calculated from the densities of electronic states. The calculations were performed within the framework of the method [43] in which the σib(E) is proportional to the DOS convolution from both sides of the EF under the assumption of equal probability of electronic transitions, both direct as well as indirect ones. Such theoretical curves, being qualitative in this approximation, are presented for both compounds in Fig. 5 by solid lines together with the experimental data.

Figure 5: Optical conductivity of (a) ScNiBi and (b) YNiBi: circles—experimental, thick solid curves—calculated. Dash, dash-dot, dot, and thin solid curves are different contributions from the Sc 3d (Y 4d), Bi 6p, Ni 3d, and Ni 4p electrons, accordingly

Fig. 5 displays the calculated curves of the interband optical conductivities for ScNiBi and YNiBi. The computed conductivities are in good accordance with the experimental ones. Both the general shape of the absorption bands and the position of the maxima are reproduced quite well. The large intensity of absorption above ~2 eV is similar in ScNiBi and YNiBi, as well as in the densities of states. Based on the DOS plots drawn in Fig. 3, the increased values of optical conductivities in ~2–6 eV can be attributed to transitions from the valence Ni 3d, Sc 3d (Y 4d) states to the conduction Sc 3d (Y 4d), Bi 6p states. These transitions are vibrant in the whole energy range, but their contributions are the largest in the regions of the main peaks. Fig. 5 shows the largest contributions to σib(E) curves from different electronic states. It can be seen that transitions involving the Ni 3d and Sc 3d (Y 4d) states play a decisive role in the formation of interband absorption maxima. Contributions from transitions involving the bands of Bi 6p and Ni 4p are much weaker, demonstrating a weak uniform growth with the energy growth.

The obtained dependences of σib(E), see Fig. 5, demonstrate no presence of optical absorption at low energies due to the occurrence of the band gap in the bands of compounds. At the same time, an increase in optical conductivity is visible in the experimental spectra in this range. In metallic materials, this growth is related to the mechanism of intraband light absorption and is described by the Drude term σ~ω−2. For the studied compounds, the low-energy rise of the σ(E) curves is weak and does not correspond to a similar dependency. The nonzero experimental values of σ(E) in this range point out the pseudogap behavior of these splits in the densities of states, which is typical for semimetallic materials. Previous studies have shown that a similar behavior of optical conductivity is noticed in many materials whose electronic structure includes the same feature located at EF [44]. In our case, a weak increase in optical conductivity in the IR region can be attributed to a structural imperfection of the studied samples, namely, the occurrence of a small percentage of the other phases, impurities, and deviations from stoichiometry. Such defects in the crystal structure contribute to the presence of free electrons, whose interaction with the electromagnetic field of a light wave (intraband absorption of light) leads to an observed behavior of σ(E) curves in the low-energy interval. The non-Drude dispersion of these dependencies manifests that the metallic properties of the compounds are strongly weakened. Note that the presence of such a very low optical conductivity in the IR region was found to be typical for semimetals with a low concentration of current carriers, in particular for Bi and Sb [42]. Hence, the main features of the experimental σ(E) spectra of ScNiBi and YNiBi are weak low-energy contribution below ~1 eV, related to intraband light absorption, and the large interband absorption above this value. Low values of optical conductivity in IR correlate with calculations of their electronic structures and densities of electronic states, which indicate the occurrence of an energy gap located at the Fermi energy. Consequently, ScNiBi and YNiBi can contribute to the elaboration of optoelectronic and luminescent materials with other inorganic materials [10–12,23,45].

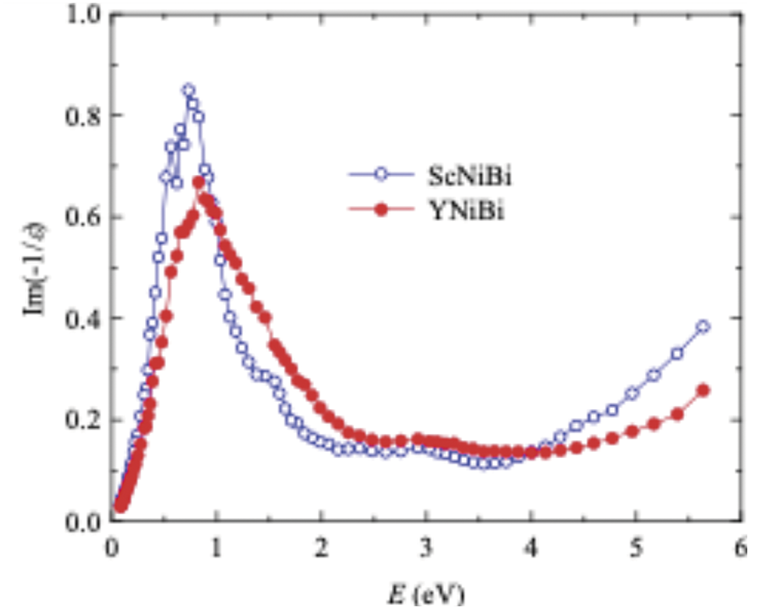

Another characteristic derived from the complex dielectric constant is the energy loss function L(ω) = Im(−1/ε(ω)) = ε2/(ε12 + ε22), which makes it possible to assess the probability of the existence and energy of plasma fluctuations, i.e., collective oscillations of an electron gas in a conductive medium. This parameter describes the discrete energy losses of conduction electrons during the excitation of volume plasma oscillations. It has a maximum at ε1 → 0, the localization of which corresponds to the plasma frequency ωP. The energy dependences of these functions (Fig. 6) show that such maxima in both materials are located at Emax ≈ 0.8 eV, i.e., the plasma frequency ωP = Emax/ħ ≈ 1.2 · 1015 s−1 for the conduction electrons.

Figure 6: Electron energy loss spectra of the ScNiBi and YNiBi compounds

Our article reports the electronic structure theoretical modeling and experimental optical results for two ternary ScNiBi and YNiBi compounds, both belonging to the class of half-Heuslers. The first-principles calculations were carried out considering spin-orbit coupling and revealed that these materials are semiconductors with an indirect gap of 0.16 eV (ScNiBi) and 0.18 eV (YNiBi). The optical properties of these compounds were investigated by the ellipsometric method in 0.22–15 μm. The energy dependences of dielectric permittivity, reflectivity, optical conductivities, and characteristic loss functions are obtained. It is shown that in the optical conductivity of ScNiBi and YNiBi, the intense interband absorption occurs at energies above ~1 eV and is weakly manifested at low energies. The structural features of the experimental σ(E) are qualitatively reproduced by calculations of this function based on the spectra of electronic states. The weak optical absorption observed in IR correlates with the theoretical results showing the presence of the band gap of both ternary compounds. The first-principles calculated gap values make ScNiBi and YNiBi valid for thermoelectric and optoelectronic applications and as selective filters.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The work was carried out in the state assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation for IMP UB RAS.

Author Contributions: Study conception, investigation, draft manuscript preparation, review, and editing: Yury V. Knyazev; investigation, draft manuscript preparation: Semyon T. Baidak; investigation: Yury I. Kuz’min; study design, investigation, draft manuscript preparation, review, and editing: Alexey V. Lukoyanov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Alexey V. Lukoyanov, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Liu Y, Cui Y, Zhou H, Shen T, Lei S, Yuan H, et al. Machine learning-based methods for materials inverse design: a review. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(2):1463–92. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.060109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yan J, Wang X, Yao M, Hu N. Electronic structure and magnetic properties of new rare-earth half-metallic materials AcFe2O4 and ThFe2O4: ab initio investigation. Comput Mater Contin. 2014;39(1):73–84. doi:10.3970/cmc.2014.039.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Tavares S, Yang K, Meyers MA. Heusler alloys: past, properties, new alloys, and prospects. Prog Mater Sci. 2023;132:101017. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2022.101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ueda K, Yu T, Hirayama M, Kurokawa R, Nakajima T, Saito H, et al. Colossal negative magnetoresistance in field-induced Weyl semimetal of magnetic half-Heusler compound. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):6339. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-41982-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Gupta S, Suresh KG, Nigam AK, Knyazev YV, Kuz’min YI, Lukoyanov AV. The magnetic, electronic and optical properties of HoRhGe. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2014;47(36):365002. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/47/36/365002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen J, Li H, Ding B, Hou Z, Liu E, Xi X, et al. Structural and magnetotransport properties of topological trivial LuNiBi single crystals. J Alloys Compd. 2019;784:822–6. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.01.128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xiao H, Hu T, Liu W, Zhu YL, Li PG, Mu G, et al. Superconductivity in the half-Heusler compound TbPdBi. Phys Rev B. 2018;97(22):224511. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.97.224511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Khan MA, Usman M, Zhao Y. First principles calculations for corrosion in Mg-Li-Al alloys with focus on corrosion resistance: a comprehensive review. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(2):1905–52. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.054691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Casper F, Graf T, Chadov S, Balke B, Felser C. Half-Heusler compounds: novel materials for energy and spintronic applications. Semicond Sci Technol. 2012;27(6):063001. doi:10.1088/0268-1242/27/6/063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Menaria GL, Rani U, Kamlesh PK, Singh R, Rani M, Singh N, et al. Electro-optic and transport properties with stability parameters of cubic KMgX (X = P, As, Sb, and Bi) Half-Heusler materials: appropriate for green energy applications. Mod Phys Lett B. 2024;38(29):2450283. doi:10.1142/S021798492450283X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Huang Y, Lv F, Han S, Chen M, Wang Y, Lou Q, et al. Piezoelectricity in Half-Heusler narrow-bandgap semiconductors. Science. 2025;387(6739):1187–92. doi:10.1126/science.ads9584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Liu ZK, Yang LX, Wu S-C, Shekhar C, Jiang J, Yang HF, et al. Observation of unusual topological surface states in half-Heusler compounds LnPtBi (Ln = Lu, Y). Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):12924. doi:10.1038/ncomms12924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Singh AK, Ramarao SD, Peter SC. Rare-earth based half-Heusler topological quantum materials: a perspective. APL Mater. 2020;8(6):060903. doi:10.1063/5.0006118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mitra M, Benton A, Akhanda MS, Qi J, Zebarjadi M, Singh DJ, et al. Conventional Half-Heusler alloys advance state-of-the-art thermoelectric properties. Mater Today Phys. 2022;28(6358):100900. doi:10.1016/j.mtphys.2022.100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Paul S, Ghosal S, Pati SK. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of Bi-based Half-Heusler compounds XYBi (X: ti, Zr, Hf; Y: co, Rh, Ir). ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2024;7(21):9595–607. doi:10.1021/acsaem.4c01652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li Y, Chen J, Lu C, Fukui H, Yu X, Li C, et al. Multiphonon interaction and thermal conductivity in Half-Heusler LuNiBi. Phys Rev B. 2024;109(17):174302. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.109.174302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Shobana Priyanka D, Srinivasan M, Sudharsan JB, Fujiwara K. Computational analysis on novel Half Heusler alloys XPdSi (X = Ti, Zr, Hf) for waste heat recycling process. Mater Sci Semicond Process. 2024;180(20):108524. doi:10.1016/j.mssp.2024.108524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Huang J, Liu R, Ma Q, Jiang Z, Jiang Y, Li Y, et al. Discovery of YbNiSb-based Half-Heusler alloys as promising thermoelectric materials. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2022;5(10):12630–9. doi:10.1021/acsaem.2c02269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhu H, Li W, Nozariasbmarz A, Liu N, Zhang Y, Priya S, et al. Half-Heusler alloys as emerging high power density thermoelectric cooling materials. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3300. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-38446-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tan S, Jiang L, Xian J, Li H, Li X, Kang H, et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of ZrCoSb Half-Heusler compounds by Sn-Bi codoping. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2024;7(18):8025–34. doi:10.1021/acsaem.4c01302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Fang T, Xia K, Nan P, Ge B, Zhao X, Zhu T. A new defective 19-electron TiPtSb Half-Heusler thermoelectric compound with heavy band and low lattice thermal conductivity. Mater Today Phys. 2020;13:100200. doi:10.1016/j.mtphys.2020.100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Deng L, Liu ZH, Ma XQ, Hou ZP, Liu EK, Xi XK, et al. Observation of weak antilocalization effect in high-quality ScNiBi single crystal. J Appl Phys. 2017;121(10):105106. doi:10.1063/1.4978015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Guo SD. Importance of spin-orbit coupling in power factor calculations for Half-Heusler ANiB (A = Ti, Hf, Sc, Y; B = Sn, Sb, Bi). J Alloys Compd. 2016;663:128–33. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.12.139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Winiarski MJ, Bilińska K. Power factors of p-type Half-Heusler alloys ScNiBi, YNiBi, and LuNiBi by ab initio calculations. Acta Phys Pol A. 2020;138(3):533–8. doi:10.12693/APhysPolA.138.533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li S, Zhao H, Li D, Jin S, Gu L. Synthesis and thermoelectric properties of Half-Heusler alloy YNiBi. J Appl Phys. 2015;117(20):205101. doi:10.1063/1.4921811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang X, Hou Z, Wang Y, Xu G, Shi C, Liu EK, et al. NMR evidence for the topologically nontrivial nature in a family of Half-heusler compounds. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):23172. doi:10.1038/srep23172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Haase MG, Schmidt T, Richter CG, Block H, Jeitschko W. Equiatomic rare earth (Ln) transition metal antimonides LnTSb (T = Rh, Ir) and bismuthides LnTBi (T = Rh, Ni, Pd, Pt). J Solid State Chem. 2002;168(1):18–27. doi:10.1006/jssc.2002.9670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sarwan M, Shukoor AV, Shareef MF, Singh S. A first principle study of structural, elastic, electronic and thermodynamic properties of Half-Heusler compounds YNiPn (Pn = As, Sb and Bi). Solid State Sci. 2021;112:106507. doi:10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2020.106507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tarekuzzaman M, Ishraq MH, Rahman MA, Irfan A, Rahman MZ, Akter MS, et al. A systematic first-principles investigation of the structural, electronic, mechanical, optical, and thermodynamic properties of Half-Heusler ANiX (A = Sc, Ti, Y, Zr, Hf; X = Bi, Sn) for spintronics and optoelectronics applications. J Comput Chem. 2024;45(29):2476–500. doi:10.1002/jcc.27455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Miranda J, Gruhn T. Mechanical and heat transport properties of Ti1−xZrxNiSn Half-Heuslers: a molecular dynamic simulation study using ab initio-based interaction potentials. Comput Mater Sci. 2022;204(12):111147. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2021.111147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bano A, Gaur NK. Investigation of strain effect on electronic, chemical bonding, magnetic and phonon properties of ScNiBi: a DFT study. Mater Res Express. 2018;5(4):046502. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/aab7ca. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sharma S, Kumar P. Tuning the thermoelectric properties of YNiBi Half-Heusler alloy. Mater Res Express. 2018;5(4):046528. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/aabbf1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang L, Yang C, Wu H. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation liquid and amorphous Al94−xNi6Lax (x = 3-9) alloys. Comput Mater Contin. 2019;60(2):757–65. doi:10.32604/cmc.2019.04499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Missoum DE, Bencherif K, Bensaid D. Ab initio study of thermodynamic and thermoelectric properties of the paramagnetic p-type Half Heusler XNiBi (X = Sc, Y). Eur Phys J B. 2023;96(12):160. doi:10.1140/epjb/s10051-023-00633-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Missoum D-E, Bencherif K, Bensaid D. First-principle investigation of physical properties of MNiBi: (M = Sc, Y) Half-Heusler compounds. Rev Mex Fis. 2022;68:061601. doi:10.31349/RevMexFis.68.061601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Fujiwara H. Spectroscopic ellipsometry: principles and applications. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2007. doi:10.1002/9780470060193 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(18):3865–8. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Prandini G, Marrazzo A, Castelli IE, Mounet N, Marzari N. Precision and efficiency in solid-state pseudopotential calculations. npj Comput Mater. 2018;4(1):72. doi:10.1038/s41524-018-0127-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Alibagheri E, Mortazavi B, Rabczuk T. Predicting the electronic and structural properties of two-dimensional materials using machine learning. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;67(1):1287–300. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.013564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Giannozzi P, Andreussi O, Brumme T, Bunau O, Buongiorno Nardelli M, Calandra M, et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J Phys Condens Matter. 2017;29(46):465901. doi:10.1088/1361-648X/aa8f79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Ordal MA, Long LL, Bell RJ, Bell SE, Bell RR, Alexander RW, et al. Optical properties of the metals Al, Co, Cu, Au, Fe, Pb, Ni, Pd, Pt, Ag, Ti and W in the infrared and far infrared. Appl Opt. 1983;22(7):1099–119. doi:10.1364/AO.22.001099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Palik EDeditor. Handbook of optical constants of solids. London, UK: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

43. Knyazev YV, Lukoyanov AV, Kuz’min YI, Kuchin AG, Nekrasov IA. Electronic structure, magnetic, and optical properties of the intermetallic compounds R2Fe17 (R = Pr, Gd). Phys Rev B. 2006;73(9):094410. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.73.094410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Knyazev YV, Lukoyanov AV, Kuz’min YI. Spectral characteristics and electronic structure of semimetallic ScSb and YSb. Opt Mater. 2022;129:112466. doi:10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ji W, Ju M, Yuan H, Xiao Y, Yeung YY. Theoretical determination of the electronic structures and energy-level splitting for Pr3+-doped Y2SiO5 crystals. J Phys Chem A. 2024;128(22):448–55. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.4c01251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools