Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

VPAFL: Verifiable Privacy-Preserving Aggregation for Federated Learning Based on Single Server

1 College of Cryptography Engineering, Engineering University of PAP, Xi’an, 710086, China

2 Key Laboratory of PAP for Cryptology and Information Security, Xi’an, 710086, China

* Corresponding Author: Minqing Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 84(2), 2935-2957. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065887

Received 24 March 2025; Accepted 08 May 2025; Issue published 03 July 2025

Abstract

Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a promising distributed machine learning paradigm that enables multi-party collaborative training while eliminating the need for raw data sharing. However, its reliance on a server introduces critical security vulnerabilities: malicious servers can infer private information from received local model updates or deliberately manipulate aggregation results. Consequently, achieving verifiable aggregation without compromising client privacy remains a critical challenge. To address these problem, we propose a reversible data hiding in encrypted domains (RDHED) scheme, which designs joint secret message embedding and extraction mechanism. This approach enables clients to embed secret messages into ciphertext redundancy spaces generated during model encryption. During the server aggregation process, the embedded messages from all clients fuse within the ciphertext space to form a joint embedding message. Subsequently, clients can decrypt the aggregated results and extract this joint embedding message for verification purposes. Building upon this foundation, we integrate the proposed RDHED scheme with linear homomorphic hash and digital signatures to design a verifiable privacy-preserving aggregation protocol for single-server architectures (VPAFL). Theoretical proofs and experimental analyses show that VPAFL can effectively protect user privacy, achieve lightweight computational and communication overhead of users for verification, and present significant advantages with increasing model dimension.Keywords

With the widespread adoption of cloud computing technologies [1], the migration of large amounts of user data to the cloud has become an irreversible trend. To address the risks of privacy breaches, encrypting data for storage has become essential. However, this measure introduces new challenges, particularly in performing operations such as metadata embedding and identity authentication while ensuring data confidentiality.

To address these challenges, the technique of reversible data hiding in the encrypted domain (RDHED) [2–4] has emerged as a promising solution. This technology enables the reversible embedding of data, such as identity markers and integrity labels, within encrypted data [5,6]. Upon decryption, both the original data and the embedded data can be completely recovered, providing an innovative approach to managing encrypted data. Despite significant advancements in traditional RDHED methods, most existing schemes rely on stream cipher encryption mechanisms, which do not support ciphertext operations [2,4–6]. This limitation makes them unsuitable for emerging privacy-preserving computing scenarios, such as federated learning (FL) [7].

In recent years, homomorphic encryption (HE)-based RDHED schemes have gained attention as a potential solution [8–10]. However, these approaches face two major technical challenges. First, their applicability is often limited because most existing research focuses on image data processing, while FL predominantly involves model parameters. Second, compatibility issues arise: existing methods do not adequately address the destructive effects of homomorphic processing on embedded data [11]. For instance, when encrypted data undergo homomorphic processing, such as ciphertext aggregation, embedded data may suffer irreversible distortion, resulting in extraction failures [12–14]. Furthermore, FL usually involves multiple participants, yet enabling each user to independently perform data embedding and extraction independently in decentralized scenarios remains a great challenge.

In a typical FL architecture, users upload their local models to the server, which aggregates the received local models to generate the global model and distributes it back to users. However, this collaborative training mechanism raises concerns about privacy leakage. In particular, a semi-honest server can infer user privacy by analyzing local or global gradients [15–17], while a malicious server could manipulate the aggregation results, thereby compromising the usability of the global model [18]. Existing privacy protection solutions, such as HE [19,20], differential privacy [21,22], and secure multiparty computation [23], can mitigate some privacy risks. However, they fail to address a critical issue: verifying the correctness of model aggregation.

To address these challenges, several verifiable federated learning (VFL) schemes have been successively proposed [18,24–27]. These solutions primarily utilize linear homomorphic hash (LHH) [18,24–26] or dual-aggregation techniques [27] to achieve verifiability. However, they exhibit limitations: the former incurs computational overhead that scales with the model dimension, while the latter suffers from the inflation of communication costs and requires auxiliary protocols for full verifiability [28,29].

This study addresses existing challenges by focusing on two core issues: (1) designing a RDHED scheme compatible with homomorphic processing, and (2) integrating this RDHED scheme with cryptographic tools to develop an efficient verifiable privacy-preserving aggregation protocol under a single-server architecture.

To achieve these goals, we propose a joint embedding-extraction mechanism (JEEM). Using the additive homomorphic property of the Paillier encryption algorithm [19], JEEM enables multiple users to collaboratively embed and extract secret messages without altering the original plaintext. Building on JEEM, we further integrate LHH [30] and digital signatures to design a verifiable privacy-preserving aggregation protocol based on a single server (VPAFL).

The contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

1) RDHED Scheme for Joint Secret Message Embedding and Extraction: This study resolves the compatibility limitations of existing RDHED schemes with homomorphic processing. Each user independently exploits ciphertext redundancy during encryption to embed secret messages. After the server aggregates the ciphertexts, homomorphic properties enable the fusion of all user-embedded messages within the ciphertext space, yielding a joint embedded message. Users can then extract this joint embedded message after decrypting the aggregation result.

2) Efficient Verifiable Aggregation Protocol: Compared to existing LHH-based VFL schemes, VPAFL enhances efficiency by integrating the proposed RDHED scheme. Specifically, VPAFL utilizes the secret message embedded by the users in each communication round as input for the hash value computation. This design decouples hash generation computational overhead from the model dimension, thereby significantly reducing the computational overhead of users for verification. Furthermore, VPAFL maintains minimal communication overhead of users for verification (below 0.2 KB) and achieves verification of aggregation results within only two interaction rounds under a single-server framework, significantly enhancing practical deployability.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related works, while Section 3 introduces preliminary concepts. Section 4 provides an overview of the system and the threat Section 5 presents the proposed RDHED scheme and details the VPAFL protocol. Sections 6 and 7 offer theoretical analyses and experimental results, respectively. Finally, Section 8 concludes this study.

In this section, we provide a brief review of the work related to RDHED schemes in the homomorphic encrypted domain and VFL.

2.1 RDHED Schemes in the Homomorphic Encrypted Domain

With the widespread application of HE in privacy computing, HE-based RDHED methods have emerged as a research hotspot [12]. These schemes are categorized into two types based on their impact on plaintext: plaintext modification schemes (Type I) and lossless data hiding schemes (Type II). Specifically, Type I methods involve embedding operations that result in changes to plaintext [9,10,13,14]. For example, a typical method modifies the ciphertext value

In contrast, Type II schemes aim to achieve lossless data hiding in ciphertexts (LDH-CT) without altering plaintexts or increasing ciphertext size [8,11,12]. For example, Zheng et al. [12] proposed a LDH-CT scheme based on numerical interval mapping: the data hider modifies the ciphertext to fall into specific subintervals corresponding to embedded bits. Using the homomorphic and probabilistic properties of cryptosystems to ensure invariance of plaintext. Wu et al. [11] proposed a RDHED scheme using random number substitution (RS). In this scheme, binary secret messages are first converted into decimal numbers that then replace the random numbers used during the encryption process to embed the data. However, this method constrains the bit length of embedded messages, as exceeding predefined limits disrupts both encryption and decryption processes.

Despite advances in existing research, two critical challenges hinder the application of RDHED schemes to FL: First, existing RDHED schemes primarily target image data carriers, whereas FL predominantly processes model parameters. Second, existing schemes do not adequately address compatibility with homomorphic processing [12–14]. In particular, when encrypted data containing embedded information undergoes homomorphic computations, such as ciphertext aggregation, the embedded data may suffer irreversible distortion, thereby leading to extraction failure.

2.2 Verifiable Federated Learning

In FL, the trustworthiness of the servers cannot be absolutely guaranteed as malicious servers can return incorrect aggregation results [18,24,25]. Models derived from such compromised servers inevitably underperform in prediction or classification tasks, necessitating VFL schemes to mitigate these risks.

Existing VFL research follows mainly two technical paths: LHH-based schemes [18,24–26] and dual-aggregation frameworks [27]. Xu et al. [18] proposed the first VFL framework, integrating a double-masking protocol [23] for privacy protection with LHH and pseudorandom techniques to achieve verifiable aggregation. However, this scheme suffers from two critical drawbacks: First, communication overheads scale with the model dimension. Second, computationally intensive bilinear pairing operations. To optimize communication efficiency, Guo et al. [24] proposed VeriFL, which decouples communication overhead for verification from model dimensions via LHH combined with equivocal commitments. Recent advances include VPFLI [25] and PriVeriFL [26], where VPFLI [25] designs a novel aggregation protocol to minimize performance degradation caused by heterogeneous client data quality, while PriVeriFL [26] employs a blockwise encryption strategy to alleviate computational bottlenecks of HE, reducing resource demands without compromising security.

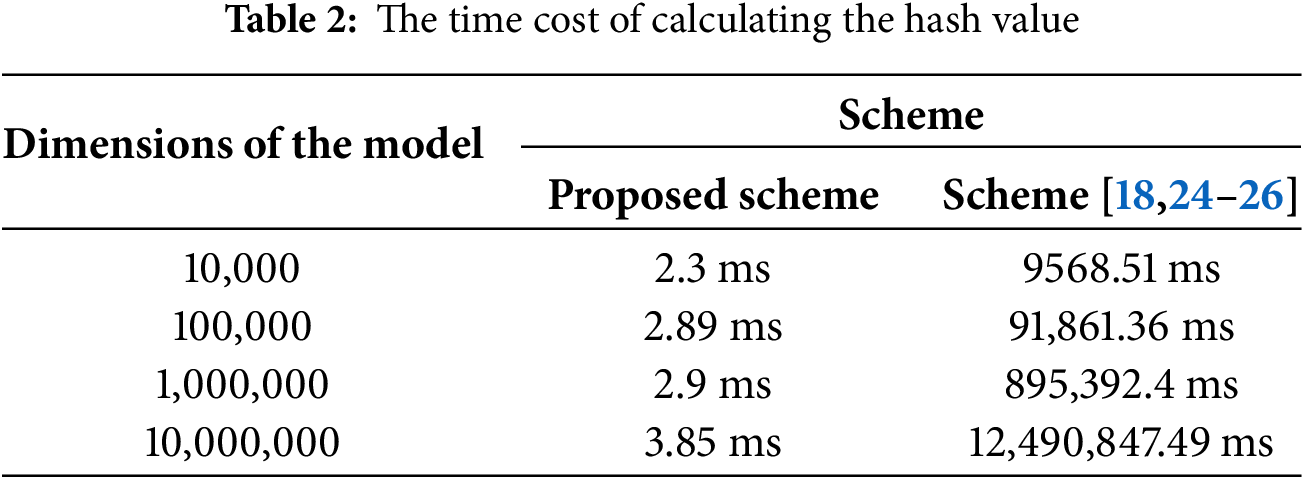

However, LHH-based VFL schemes remain plagued by high computational overhead, as the complexity of hash value calculation increases with model dimensions [26]. To enable lightweight verification, Hahn et al. proposed VERSA [27], a dual-aggregation verification framework that eliminates the need for trusted setups and uses a lightweight pseudorandom generator (PRG) to enable efficient verification of the aggregation result. However, recent studies have identified vulnerabilities that compromise its verifiability [28,29].

In summary, neither LHH-based VFL nor dual-aggregate verification-based schemes achieve high efficiency. As shown in Table 2 (detailed in Section 7.4.1), the LHH-based approach incurs significant computational overhead during verification as the model dimension grows, requiring approximately 12,490 s to compute the LHH values for models with dimensions reaching 10,000,000. In contrast, dual-aggregate verification-based schemes face substantial communication overhead: Users must submit both local model updates and validation codes derived from these parameters, which doubles their communication expenditure. Furthermore, as the model dimensionality increases, the communication overhead introduced by validation becomes impractical for real-world applications. Crucially, given the resource constraints of end-user devices, the designed VFL framework should maintain lightweight communication and computational overheads for verification to facilitate practical deployment.

In this section, we provide the foundational concepts necessary to understand our VPAFL scheme.

Deep learning has attracted significant attention for its remarkable achievements in various fields, though high-performance deep neural networks (DNNs) typically rely on extensive datasets. However, the data used to train DNNs often contain sensitive information. For example, location-based services [31] could expose personal whereabouts, while goods purchase records can be exploited for targeted advertising. More critically, the leakage of health information or facial data poses serious privacy risks. To address these challenges, FL has emerged as a promising solution [7]. Since its inception, FL has been widely adopted in various applications such as the Internet of Things (IoT), smart healthcare [32], and smart cities [33]. FL is a distributed machine learning paradigm that collaboratively trains a global model by coordinating multiple participants without compromising data privacy. In this architecture, the server does not directly access user data; instead, it iteratively aggregates parameters to optimize the global model. Let

a) Global Model Distribution: The server broadcasts the current global model

b) Local Model Training: Each user

c) Model Aggregation: The server aggregates the received local models via the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm [7] to generate the updated global model

Formally, during the

where

LHH [30] is a one-way and collision-resistant homomorphic hash function that can calculate the hash of a composite data block based on the hash of a single data block. The LHH scheme is formally defined by three algorithms LHH = (LHH.Gen, LHH.Hash, LHH.Eval):

a)

b)

c)

4 Overview of the System and the Threat Model

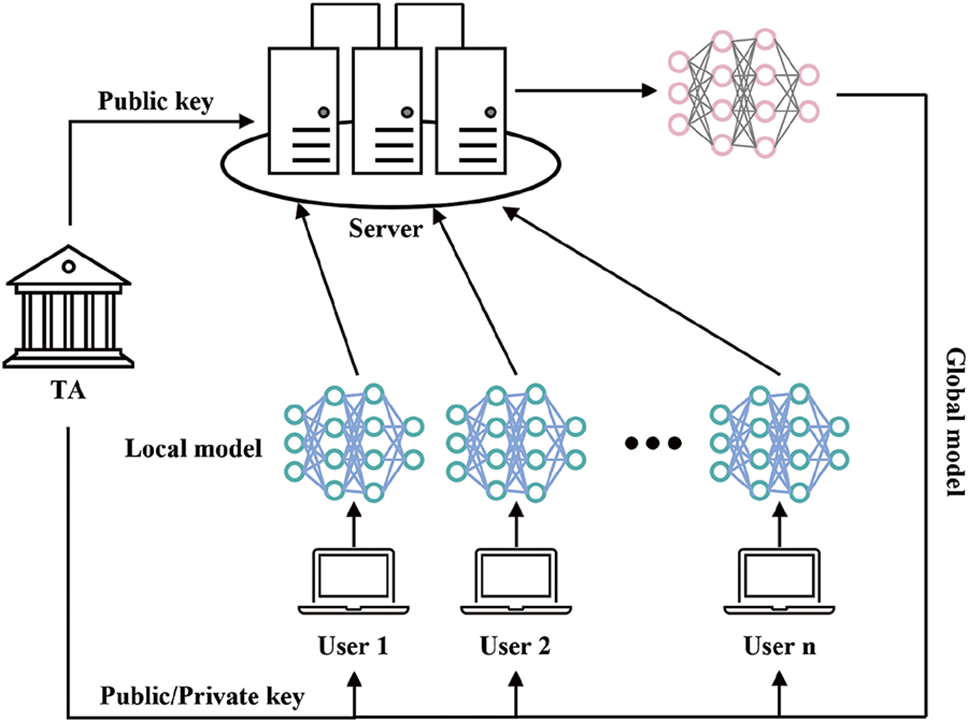

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the system model of the VPAFL protocol comprises three entities, consistent with previous works [18,24]: The trusted authority (TA), the server, and the users.

Figure 1: System model of VPAFL

• TA: The TA initializes the system by generating cryptographic parameters (public/private keys) and distributing the initial global model to all participants. It is considered trustworthy and remains offline after initialization.

• Server: The server aggregates encrypted local models received from users, updates the global model, and broadcasts the aggregated result to the user for verification.

• Users: In each communication round (except for the first), users download the latest global model from the server as their local mode. During the first communication round, the TA initializes the global model. Each user trains the local model on their private dataset, encrypts the local model parameters with their private key, and uploads the ciphertext to the server. Upon receiving the aggregated result, users verify its correctness. Training continues only if verification succeeds; otherwise, training is aborted.

Our threat model is defined as follows:

• Semi-honest users: Users follow the FL protocol faithfully, but may attempt to infer sensitive information from the data of honest users. Additionally, a subset of users may collude with the server to manipulate the aggregation results.

• Server: The server may attempt to infer user privacy or forge verifiable aggregation results. In particular, the server can collude with up to

• Out-of-Scope attacks: In FL systems, not all participants are trustworthy, as malicious users can launch poisoning attacks [36] aimed at manipulating local models to compromise the performance of the global model. However, this paper does not consider poisoning attacks, as our primary objective focuses on ensuring the correctness of the aggregation results while maintaining user privacy protection.

In this section, we first propose a RDHED scheme designed for compatibility with homomorphic processing. In particular, we design a JEEM by utilizing the additive homomorphic properties of the Paillier cryptosystem [19]. Subsequently, we further construct the VPAFL protocol by integrating the proposed RDHED scheme with the LHH [30] and digital signature algorithms.

5.1 Joint Embedding-Extraction Mechanism

Extending the drop-tolerant secure aggregation algorithm (DTSA) proposed by Zhao et al. [20], we propose a novel secure aggregation-data hiding (SADH) hybrid algorithm that is compatible with homomorphic processing. The core innovation of SADH lies in its JEEM, which enables users to collaboratively embed secret messages in ciphertext and extract them after aggregation. For simplicity, we assume that no user dropout occurs during training. The scheme operates as follows:

•

where the private key is denoted as

•

The core mechanism lies in embedding secret messages through redundant ciphertext values without changing the plaintext, as demonstrated in Section 6.1. The key parameters are defined as follows:

– The embedded message

– The random number

– The user set

where

Define

5.2 Verifiable Privacy-Preserving Aggregation for Federated Learning

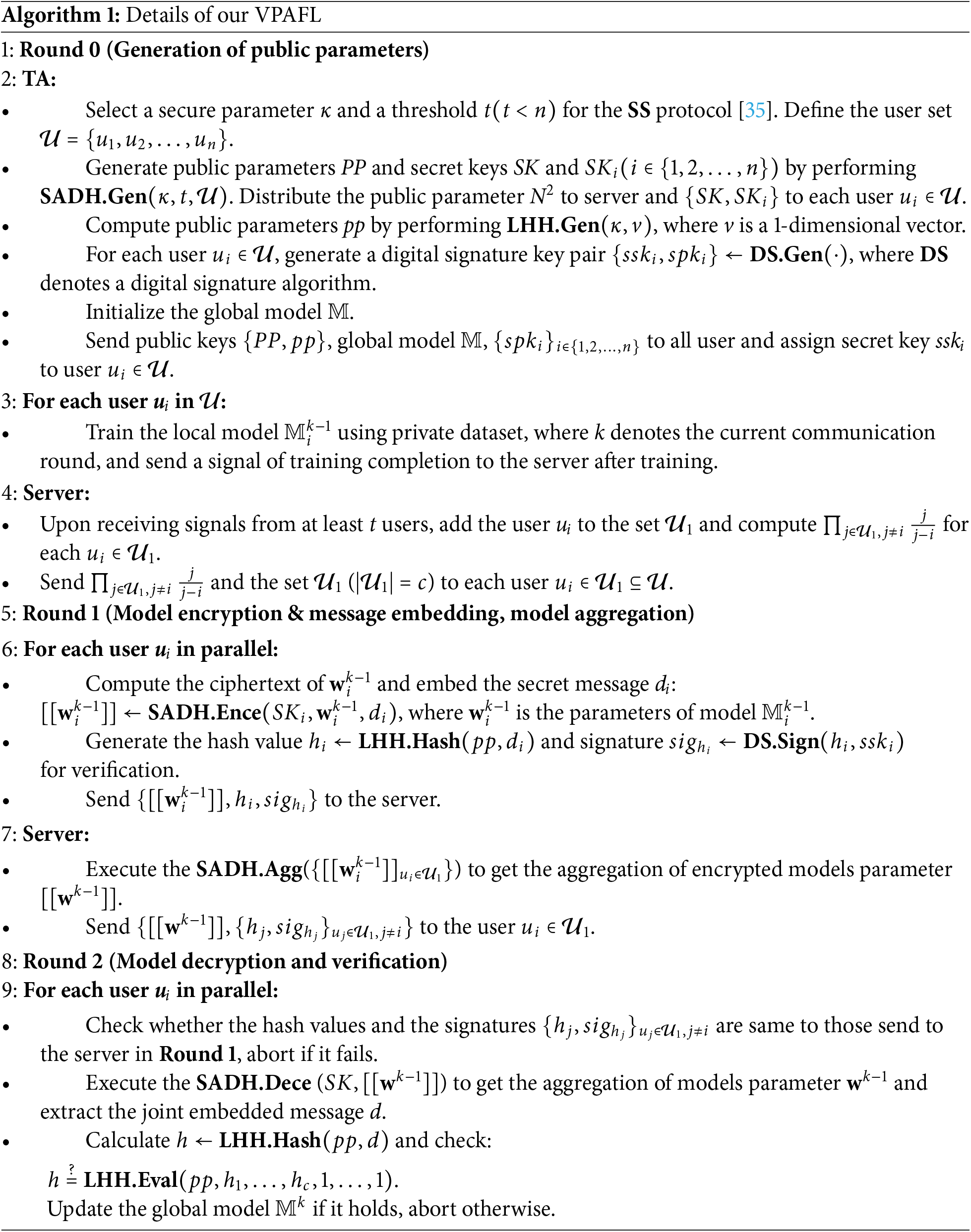

In the proposed protocol, users first utilize SADH to encrypt their local models and embed secret messages, subsequently uploading both the hash and the signature to the server. Following this, the server aggregates the received ciphertexts and returns the aggregation results along with the collected hashes and signatures to the users. Finally, after receiving these, each user decrypts the aggregation result to obtain the global model, extracts the joint embedded message, and performs verification to confirm the correctness of the aggregation result. The specific details of VPAFL (Algorithm 1) is illustrated in protocol in particular, the proposed protocol requires two rounds of interaction, with the specific processes for processes for each round described below:

In Round 0, TA initializes the system, distributes the public parameters PP,

In Round 1, each user

In Round 2, each user

6 Theoretical and Comparative Analysis

We define correctness as the ability to ensure that the user gets the correct aggregation result to update the local model when all entities involved in the FL honestly perform the predetermined operations in the protocol.

Theorem 1. The user can obtain the correct aggregation result if at least

Proof of Theorem 1: Assume

Then, as shown in Protocol 1, the ciphertext received by server aggregation in Round 1 is as follows:

where

From Eq. (3),

where

This concludes the proof.

This section begins by analyzing the security of SADH and subsequently evaluates the security of VPAFL under two adversarial scenarios: (1) a malicious server operating independently and (2) a malicious server colluding with up to

Theorem 2. If DTSA is indistinguishability under chosen-plaintext attack (IND-CPA) security, then the SADH is IND-CPA security.

Proof of Theorem 2: As mentioned earlier, according to Eq. (4), the user replaces the random number used in the encryption process with the product of a decimal number and the random number

Theorem 3. (Security Against Malicious Server) In the absence of collusion between the malicious server and semi-honest users, the privacy of all honest users is preserved.

Proof of Theorem 3: To formally prove privacy guarantees, we employ a standard hybrid argument [37], proved as follows: Under the (SADH, LHH)-hybrid model, assuming that the security parameter of VPAFL is

hyb0 First, we create a series of random variables, which are indistinguishable from the joint real view of V in

hyb1 In this hybrid, we change the behavior of the user

where

hyb2 In this hybrid, the server aggregates the received ciphertext and returns the aggregation result, the received LHH value and the digital signature to each user:

Similarly, the security of SADH algorithm ensures the same distribution between hyb2 and hyb1.

As mentioned above, based on the security of the SADH and LHH algorithms, we prove that the view in the PPT simulator

Theorem 4. (Security against Colluding Malicious Server and Users) Even if a malicious server colludes with up to

Proof of Theorem 4: According to Eq. (7), the user

where

where

According to Theorem 3 and Theorem 4, we further demonstrate the resistance of VPAFL to inference attacks under two threat scenarios: (1) attacks initiated solely by the server and (2) collusion between the server and malicious users.

Regarding the global model, since all users transmit encrypted model parameters, the server exclusively operates on ciphertexts during aggregation. This prevents the server from directly analyzing sensitive information. Even if the server colludes with a user to obtain the private key SK, the inherent lack of auxiliary training data ensures that meaningful inference remains infeasible.

For local updates, in the VPAFL protocol, users employ SADH to encrypt local model updates. Under the first threat model (only malicious server), Theorem 3 guarantees that the server cannot decrypt the encrypted parameters of any user without access to the corresponding private key

Theorem 5. We define verifiability as the ability of each client to independently verify the correctness of the aggregation results under the threat model defined in Section 4.2.

Proof of Theorem 5: According to the operation of the malicious server on the aggregation results, we consider two scenarios to prove the effectiveness of the verification.

Scenario 1 (Partial Model Aggregation): Let the total number of users be

According to Eq. (10), the user decrypts the ciphertext using private key SK to to obtain the global model

Based on the definitions in Section 3.2, we have:

Obviously Eq. (18) does not hold and therefore the aggregation result fails to pass validation.

Scenario 2 (Collusion Attack): The server colludes with

Let

where

where

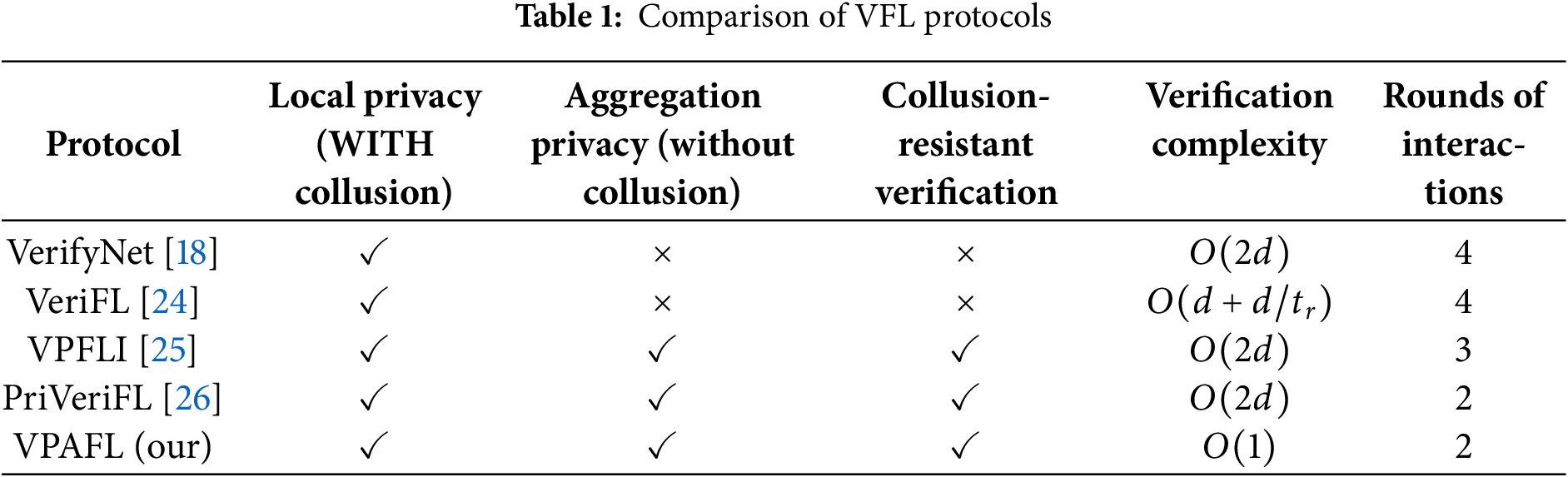

We compare VPAFL with existing LHH-based VFL schemes, including VerifyNet [18], VeriFL [24], VPFLI [25], and PriVeriFL [26], as shown in Table 1. VerifyNet [18] and VeriFL [24] are based on the double-masking protocol [23], which effectively protects the local gradients of users but fails to protect the privacy of aggregation results. Moreover, these schemes require multiple rounds of interaction between users and the server, increasing communication overhead. In particular, they do not address the risk that corrupted clients colluding with a malicious server are forged to bypass verification. To mitigate collusion attacks during verification, VPFLI [25], PriVeriFL [26], and our proposed VPAFL employ LHH combined with digital signatures, ensuring collusion-resistant verification.

Regarding aggregation privacy, VPFLI [25] introduces a blinding factor to mask the aggregation results, while VPAFL and PriVeriFL [26] delegate decryption authority to users. This approach prevents the server from directly decrypting the aggregation results, thus enhancing privacy protection. However, it is important to note that neither VPFLI [25], PriVeriFL [26], nor VPAFL can fully preserve aggregation results in privacy under collusion attacks. Since FL inherently involves collaborative training of a unified global model, the server only needs to collude with a single user to obtain the global model.

In terms of verification complexity, we assume that the computational complexity of each call to LHH is

In this section, similar to previous studies [18,25], we evaluate the performance of VPAFL in terms of fidelity, computational overhead, and communication overhead.

This subsection describes the experimental settings for VPAFL.

Model Architectures and Datasets: We employ two deep neural network architectures: AlexNet [38] for the CIFAR-100 [39] classification task and FedCNN for the MNIST [40] and CIFAR-10 [39] classification task.

Federated Learning Settings: Based on the open-source personalized FL framework (https://github.com/TsingZ0/PFLlib, accessed on 7 May 2025) [41], we simulate a horizontal FL environment where users employ the SGD algorithm [34] for local model updates during each communication round, with the server using the FedAvg algorithm [7] for model aggregation.

All experiments were conducted on an Ubuntu 22.04 workstation equipped with an Intel Xeon Platinum 8352V 2.10 GHz CPU, 60 GB RAM, and a single NVIDIA 4090 GPU. Our implementation uses Python 3.9 with stable libraries. The LHH is implemented using NIST P-256 curves. FedCNN is a convolutional neural network with the following architecture:

Fidelity: We measure fidelity using the accuracy of the model on the classification task, denoted by

Computational and Communication Overhead: Similarly to previous studies [18,24], we measure computational and communication overhead to evaluate the efficiency of the VPAFL.

Baseline: Regarding the selection of the baseline for overhead comparison, we adopt VPFLI [25] because it also uses the DTSA algorithm [20] as the privacy-preserving strategy. In particular, VPFLI [25] introduces a weight aggregation protocol to mitigate the degradation of model performance caused by heterogeneous user data quality. To ensure comparability, we exclusively retain the core modules relevant to VFL during baseline reproduction.

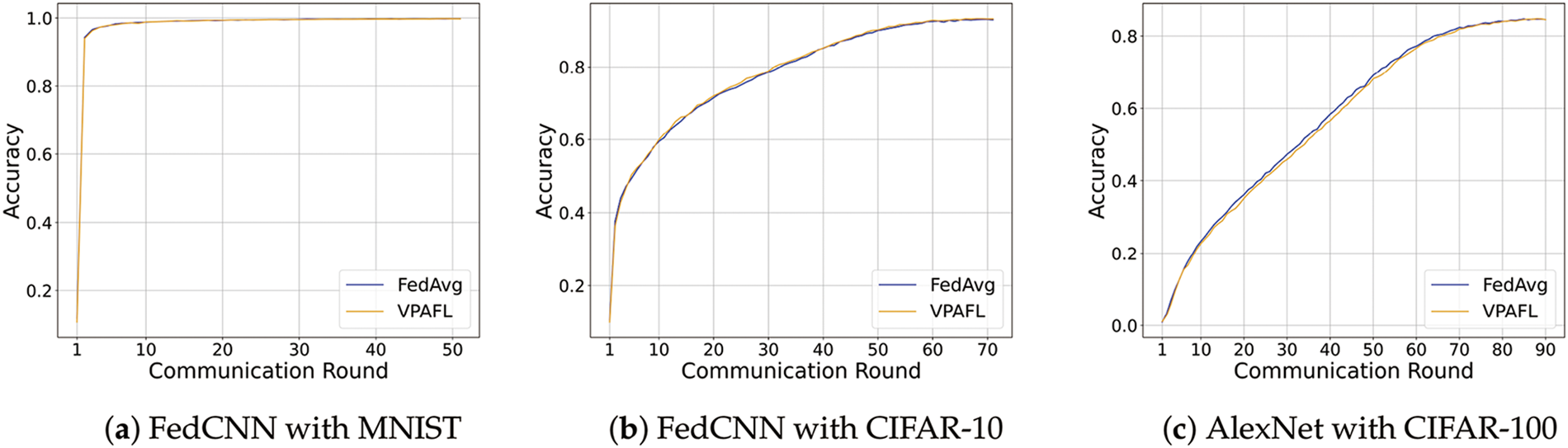

To validate that the proposed scheme maintains aggregation accuracy without compromising privacy guarantees, we evaluate its performance on three datasets: MNIST [40], CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100 [39], adopting identical training configurations (e.g., learning rate, batch size) for direct comparison with the FedAvg algorithm [7]. As shown in Fig. 2, the proposed VPAFL protocol achieves an aggregation effectiveness comparable to that of FedAvg [7], with a stable convergence behavior observed across all datasets. This consistency originates from the mathematically lossless encryption and decryption of the plaintext model parameters, thereby preserving data integrity throughout the FL process.

Figure 2: The task accuracy (

7.4 Computational and Communication Overhead

To systematically analyze system efficiency, we define

The computational overhead of the user in VPAFL is primarily determined from modular arithmetic operations in

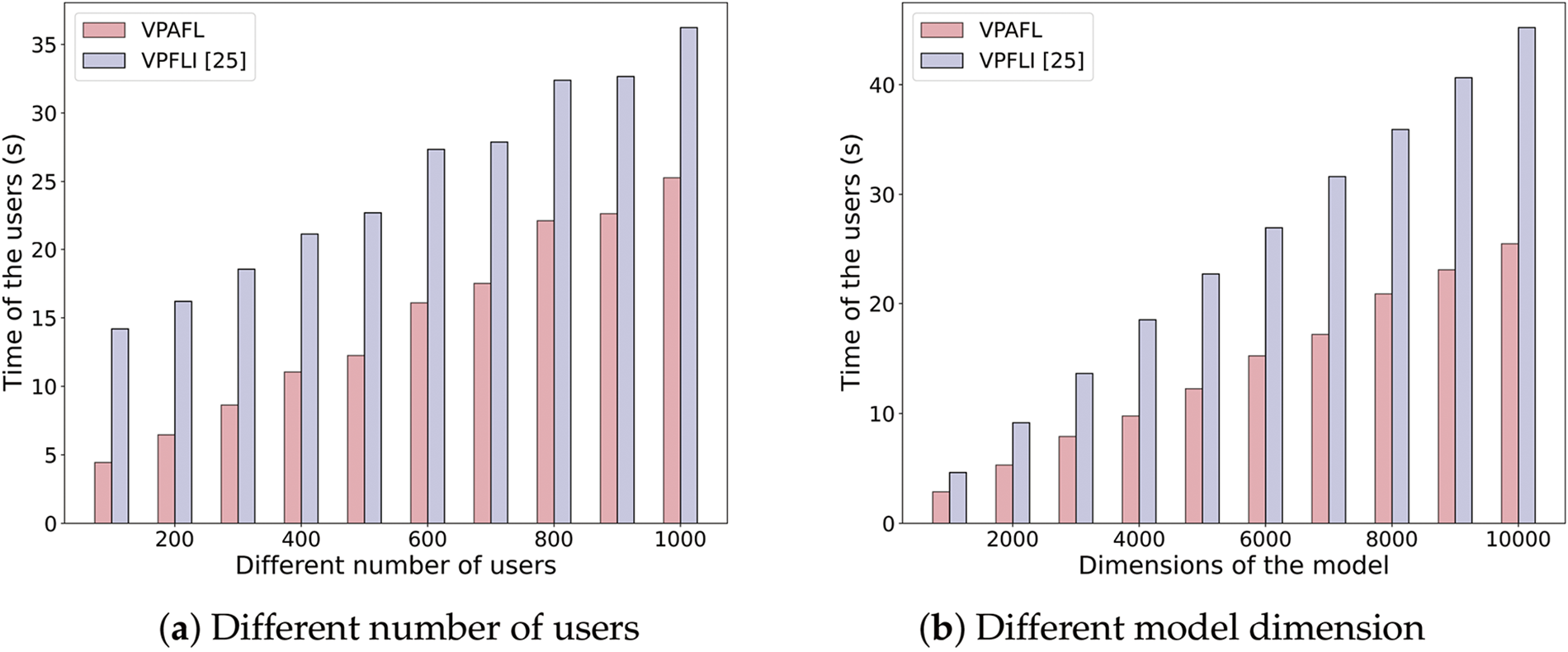

Fig. 3 illustrates the computational overhead of a single user per communication round. The computational overhead exhibits a positive correlation with both the number of participating users

Figure 3: Computational overheads of the users [25]

To further evaluate the efficiency of the verification process, Fig. 4 quantifies the computational overhead for a single user to verify aggregated results. The experimental results show that verification overhead increases with the number of users

Figure 4: Computational overheads of the users for verification [24,25]

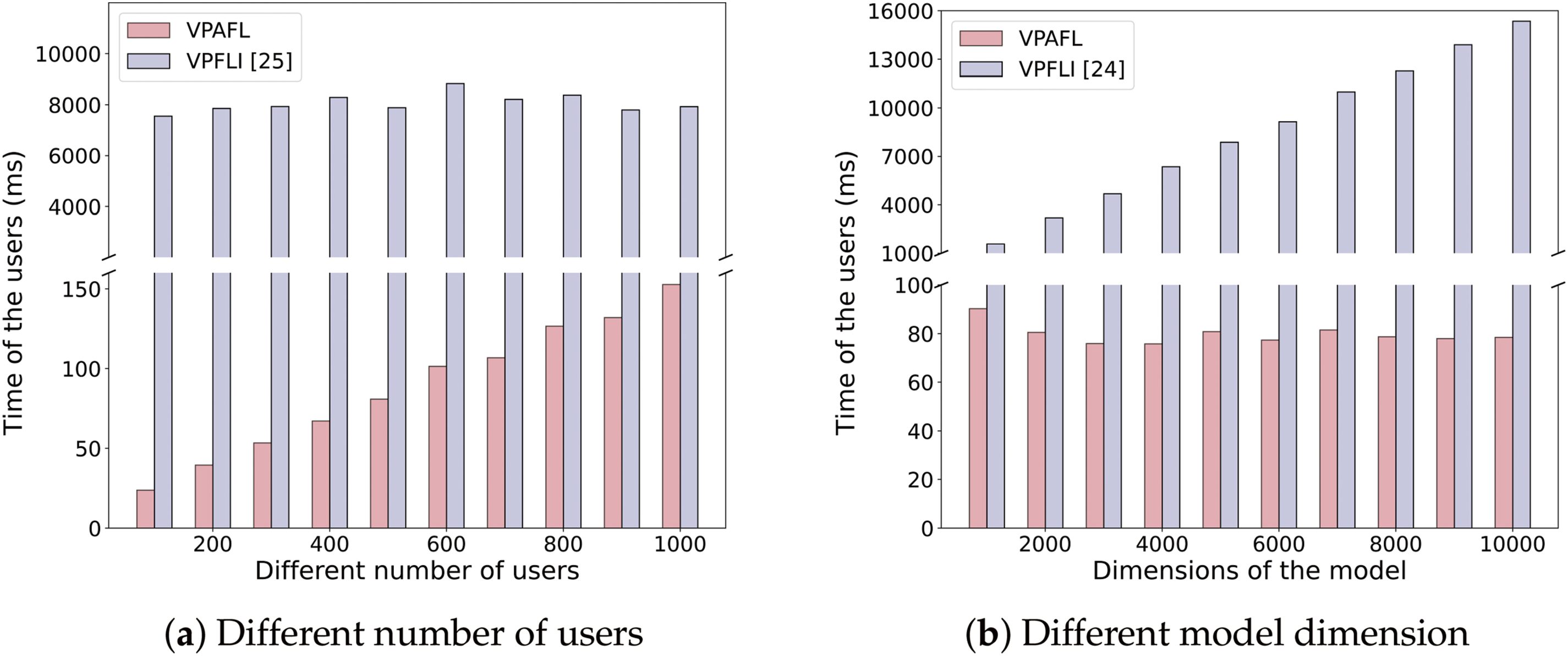

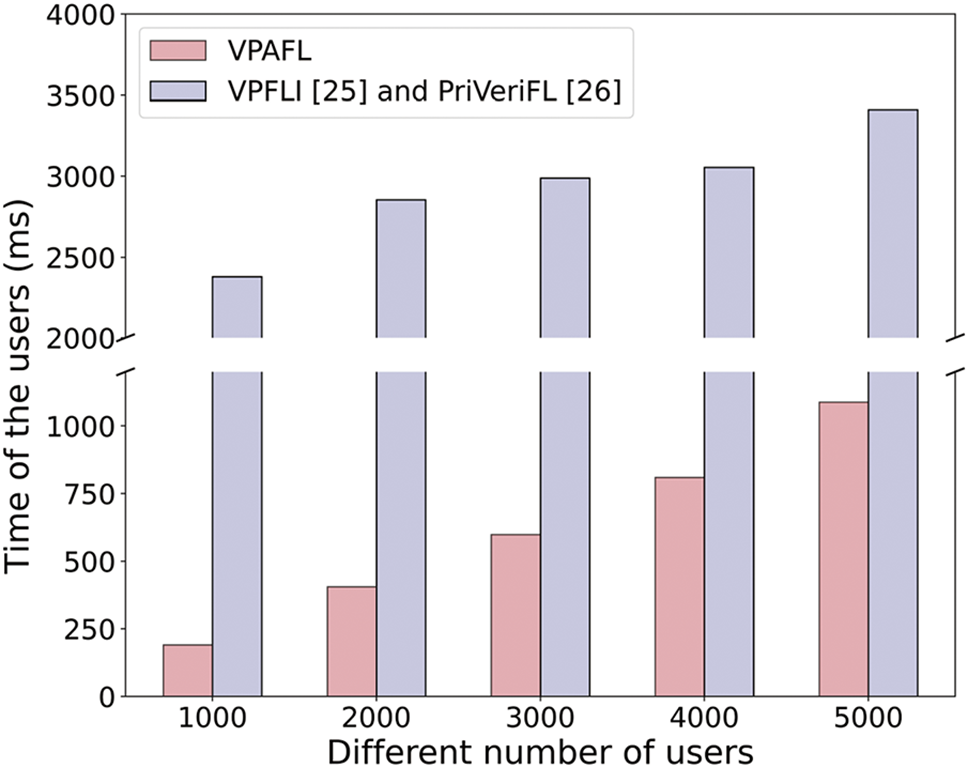

In addition, we further investigate the performance of VPAFL in large-scale user scenarios. To evaluate scalability, we measure the computational overhead per user during validation under a fixed model dimension

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the results demonstrate that the computational overhead of the users for verification in all three schemes increases with the number of participating users. This growth pattern originates mainly from the cost of LHH.Eval, whose computational complexity scales with the number of participating users. While the verification process requires checking more digital signatures as user numbers expand, this component contributes minimal overhead, approximately 0.3 ms even at 5000 users. Note that although VPFLI [25] and PriVeriFL [26] employ distinct cryptographic algorithms, they share the same verification mechanism. Therefore, the computational overheads of the users for verification remain identical in both schemes.

Figure 5: Computational overheads of the users for verification with large user scenarios [25,26]

In particular, VPAFL maintains significantly lower overhead than both VPFLI [25] and PriVeriFL [26]. This advantage arises from differences in LHH implementation, and we elucidate the precise reasons for this disparity in the following analysis.

The performance superiority of VPAFL originates from a fundamental distinction in hash computation mechanisms between the two schemes. Although VPFLI [25] employs LHH to decouple communication overhead from model dimension

In summary, the computational overhead of the users for verification in VPAFL is lightweight, making it more conducive to practical deployment, particularly in scenarios involving large-scale models or numerous participating users.

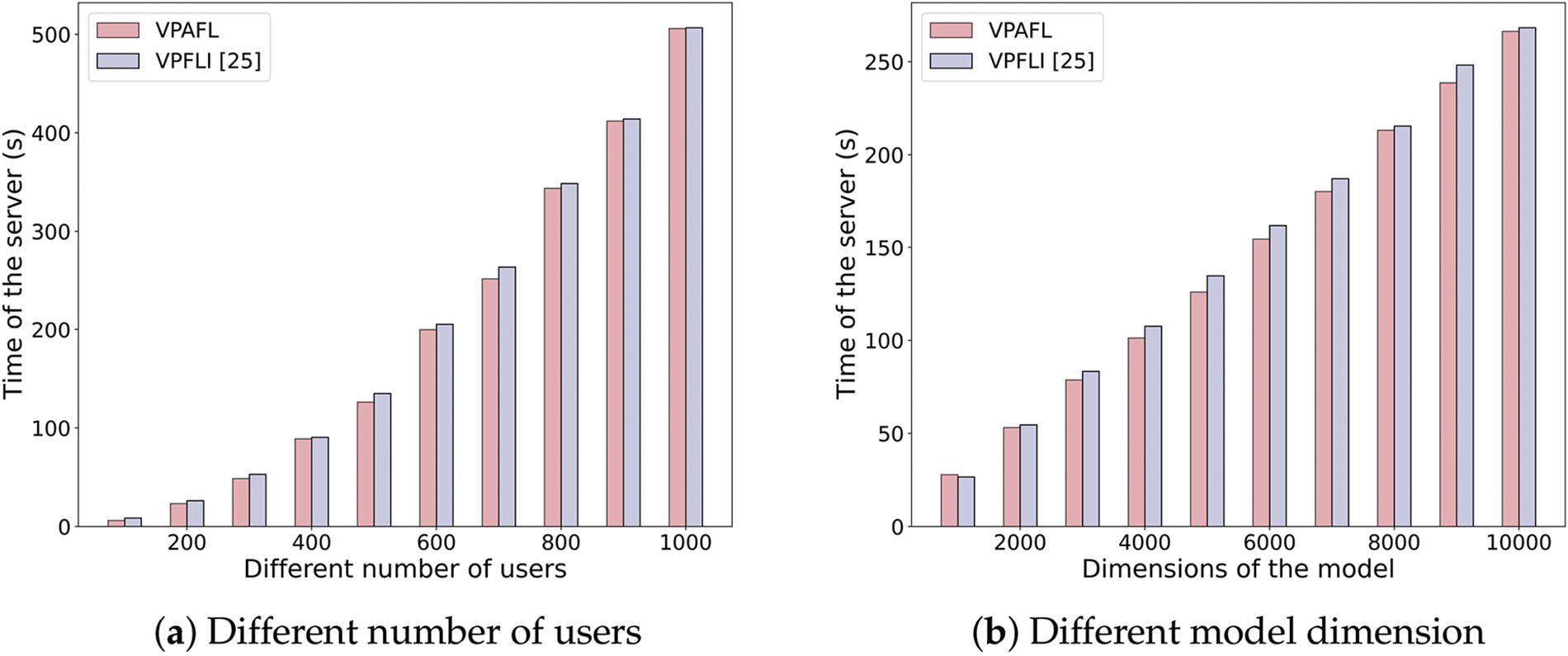

In VPAFL, the server is responsible for aggregating the encrypted local models received and its computational overhead is

Figure 6: Computational overheads of the server [25]

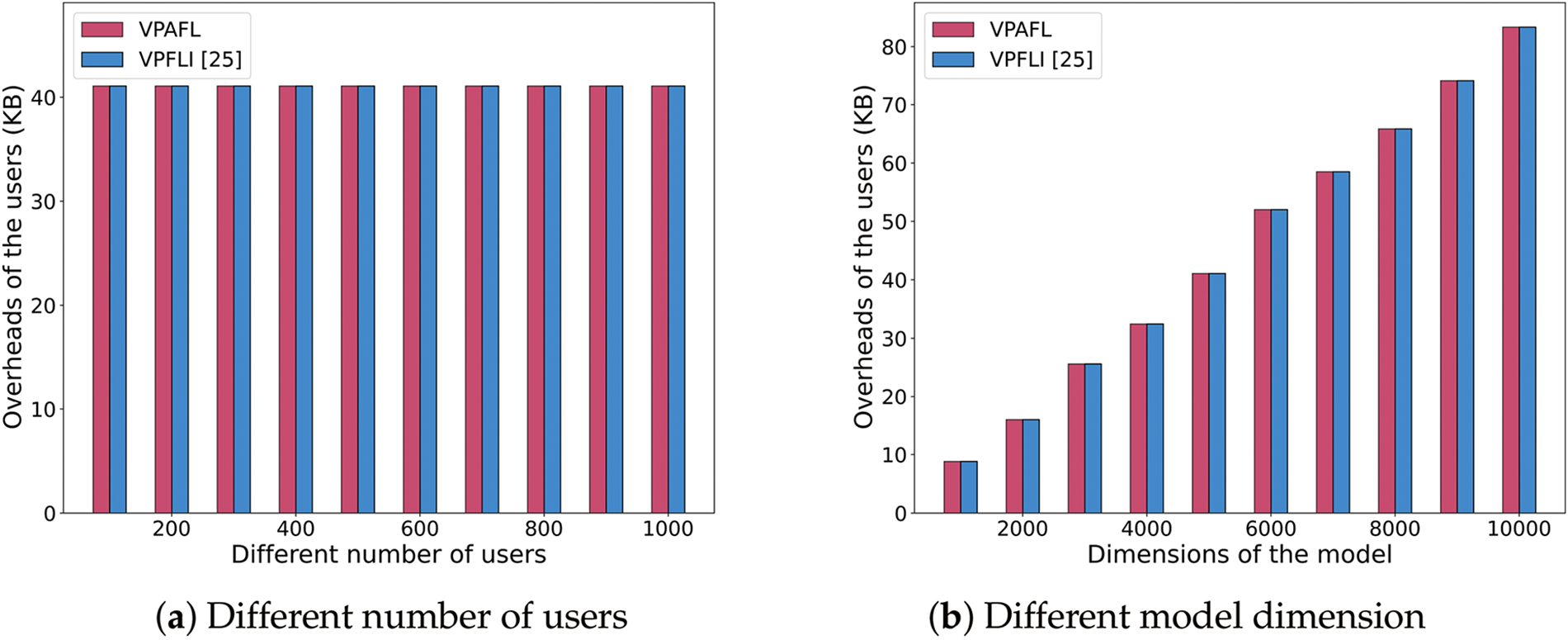

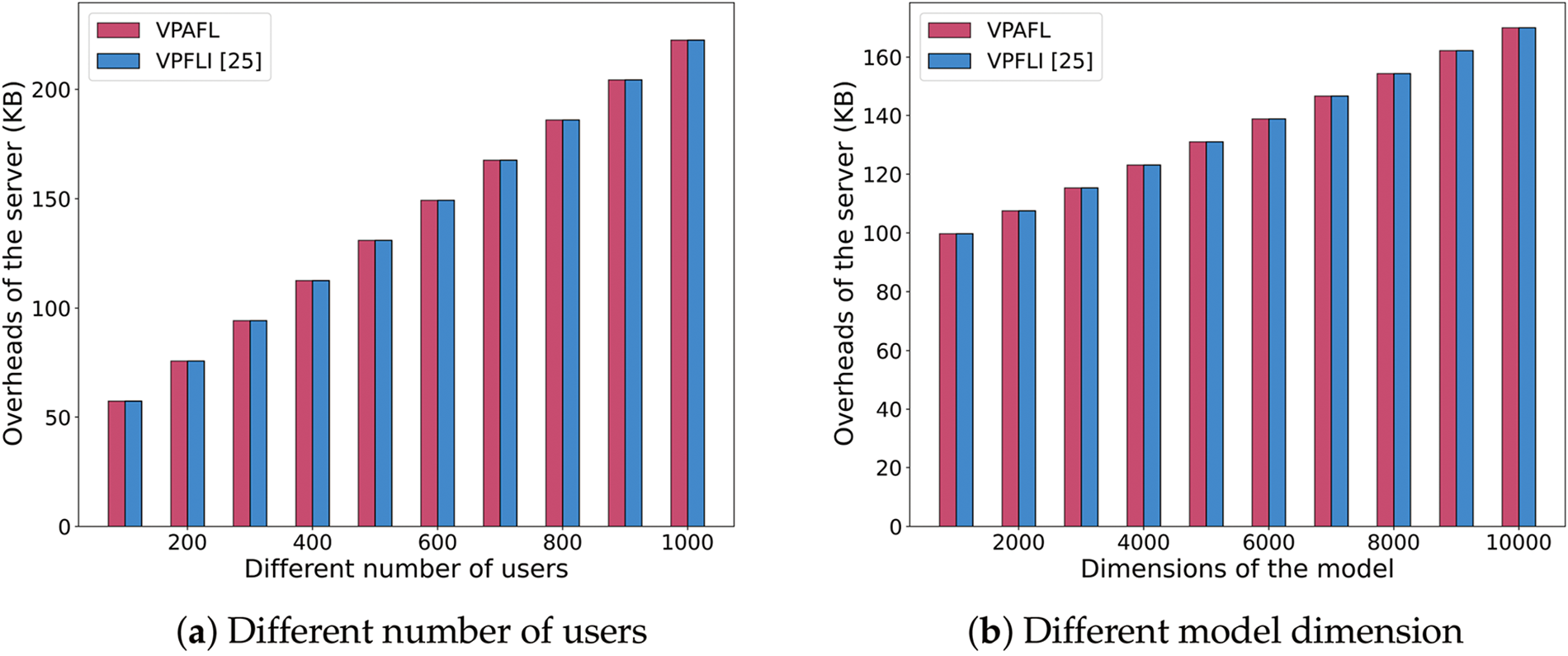

In the experiment, we measure the communication overhead by the size of the uploaded information. As shown in Fig. 7, the communication overhead of the users is not related to the number of users, but related to the model dimension

Figure 7: Communication overheads of the users [25]

Figure 8: Communication overheads of the server [25]

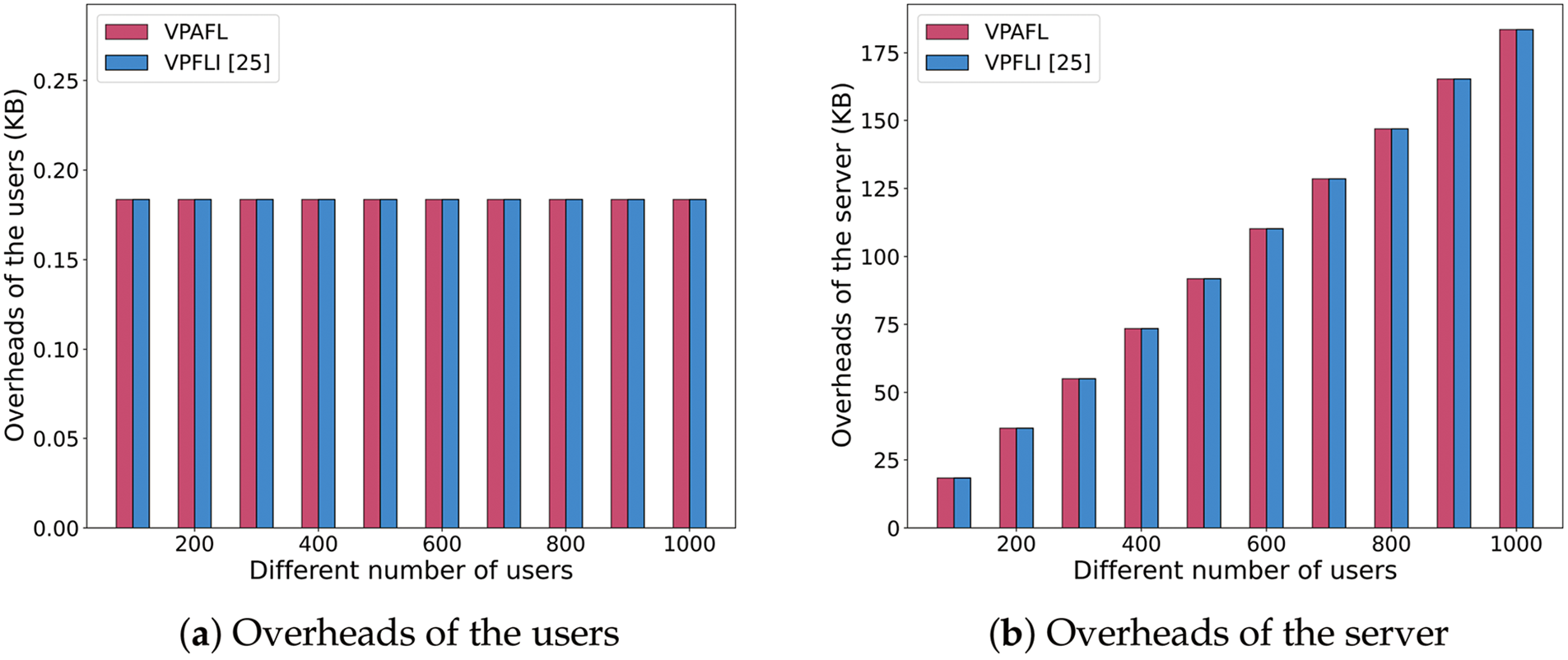

Finally, we evaluate the communication overhead associated with the verification. Since our implementation reproduces only the verifiable module of VPFLI [25] while maintaining consistency with the proposed scheme in other components, both schemes exhibit identical communication overhead under identical experimental configurations. For the user, LHH and digital signature algorithms transform variable length messages into fixed size outputs, thus decoupling verification-related communication overhead from both the number of users

Fig. 9 shows the communication overhead for individual users and servers under fixed model dimensions

Figure 9: Communication overheads for verification when

In this paper, we propose a reversible data hiding in encrypted domains (RDHED) scheme that designs a joint message embedding and extraction mechanism. Building on this RDHED scheme, we further design VPAFL, a verifiable privacy-preserving aggregation protocol for single-server architectures, by combining linear homomorphic hash and digital signature algorithms. Unlike prior verifiable federated learning schemes based on linear homomorphic hash, VPAFL computes hash values using secret messages embedded by users during each communication round, thereby decoupling the computational overhead of hash generation from the model dimension. Theoretical analysis demonstrates the security and feasibility of VPAFL, while the experiment results confirm that the computational and communication overheads of the users for verification are lightweight.

Acknowledgement: The authors appreciate the valuable comments from the reviewers and editors.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 62102450, 62272478 and the Independent Research Project of a Certain Unit under Grant ZZKY20243127.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Peizheng Lai, Minqing Zhang; Experimental operation and data proofreading: Peizheng Lai, Yixin Tang, Ya Yue; Analysis and interpretation of results: Peizheng Lai, Minqing Zhang, Fuqiang Di; Draft manuscript preparation: Peizheng Lai, Ya Yue; Figure design and drawing: Peizheng Lai, Yixin Tang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used to support the findings of this study are publicly available on Internet as follows: MNIST: http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/ (accessed on 24 March 2025); CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/kriz/cifar.html (accessed on 24 March 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Tari Z, Yi X, Premarathne US, Bertok P, Khalil I. Security and privacy in cloud computing: vision, trends, and challenges. IEEE Cloud Computing. 2015;2(2):30–8. doi:10.1109/MCC.2015.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Cao X, Du L, Wei X, Meng D, Guo X. High capacity reversible data hiding in encrypted images by patch-level sparse representation. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2015;46(5):1132–43. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2015.2423678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Shi YQ, Li X, Zhang X, Wu HT, Ma B. Reversible data hiding: advances in the past two decades. IEEE Access. 2016;4:3210–37. doi:10.1109/access.2016.2573308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Qian Z, Zhou H, Zhang X, Zhang W. Separable reversible data hiding in encrypted JPEG bitstreams. IEEE Trans Depend Secure Comput. 2016;15(6):1055–67. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2016.2634161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zheng S, Li D, Hu D, Ye D, Wang L, Wang J. Lossless data hiding algorithm for encrypted images with high capacity. Multimed Tools Appl. 2016;75(21):13765–78. doi:10.1007/s11042-015-2920-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Puteaux P, Puech W. An efficient MSB prediction-based method for high-capacity reversible data hiding in encrypted images. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Security. 2018;13(7):1670–81. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2018.2799381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BA. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Artificial intelligence and statistics; 2017; New York, NY, USA: PMLR. p. 1273–82 [Google Scholar]

8. Wu HT, Cheung YM, Tian Z, Liu D, Luo X, Hu J. Lossless data hiding in NTRU cryptosystem by polynomial encoding and modulation. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Security. 2024;19(11):3719–32. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2024.3362592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Anushiadevi R, Amirtharajan R. Design and development of reversible data hiding-homomorphic encryption & rhombus pattern prediction approach. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2023;82(30):46269–92. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-15455-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhou N, Zhang M, Wang H, Ke Y, Di F. Separable reversible data hiding scheme in homomorphic encrypted domain based on NTRU. IEEE Access. 2020;8:81412–24. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2990903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wu HT, Cheung YM, Zhuang Z, Xu L, Hu J. Lossless data hiding in encrypted images compatible with homomorphic processing. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2022;53(6):3688–701. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2022.3163245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zheng S, Wang Y, Hu D. Lossless data hiding based on homomorphic cryptosystem. IEEE Trans Depend Secure Comput. 2019;18(2):692–705. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2019.2913422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xiang S, Luo X. Reversible data hiding in homomorphic encrypted domain by mirroring ciphertext group. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2018;28(11):3099–110. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2017.2742023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ke Y, Zhang MQ, Liu J, Su TT, Yang XY. Fully homomorphic encryption encapsulated difference expansion for reversible data hiding in encrypted domain. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2020;30(8):2353–65. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2019.2963393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hitaj B, Ateniese G, Perez-Cruz F. Deep models under the GAN: information leakage from collaborative deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2017; New York, NY, USA. p. 603–18. [Google Scholar]

16. Zhu L, Liu Z, Han S. Deep leakage from gradients. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2019;32:14747–56. [Google Scholar]

17. Ma C, Li J, Ding M, Yang HH, Shu F, Quek TQ, et al. On safeguarding privacy and security in the framework of federated learning. IEEE Network. 2020;34(4):242–8. doi:10.1109/MNET.001.1900506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xu G, Li H, Liu S, Yang K, Lin X. VerifyNet: secure and verifiable federated learning. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Security. 2019;15:911–26. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2019.2929409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Paillier P. Public-key cryptosystems based on composite degree residuosity classes. In: International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 1999; Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. p. 223–38. [Google Scholar]

20. Zhao J, Zhu H, Wang F, Lu R, Li H, Tu J, et al. CORK: a privacy-preserving and lossless federated learning scheme for deep neural network. Inform Sciences. 2022;603(3):190–209. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.04.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wei K, Li J, Ding M, Ma C, Yang HH, Farokhi F, et al. Federated learning with differential privacy: algorithms and performance analysis. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Security. 2020;15:3454–69. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2020.2988575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wei K, Li J, Ma C, Ding M, Chen W, Wu J, et al. Personalized federated learning with differential privacy and convergence guarantee. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Security. 2023;18:4488–503. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2023.3293417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bonawitz K, Ivanov V, Kreuter B, Marcedone A, McMahan HB, Patel S, et al. Practical secure aggregation for privacy-preserving machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2017; New York, NY, USA. p. 1175–91. [Google Scholar]

24. Guo X, Liu Z, Li J, Gao J, Hou B, Dong C, et al. VeriFL: communication-efficient and fast verifiable aggregation for federated learning. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Security. 2020;16:1736–51. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2020.3043139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ren Y, Li Y, Feng G, Zhang X. VPFLI: verifiable privacy-preserving federated learning with irregular users based on single server. IEEE Trans Services Computing. 2024;18(2):1124–36. doi:10.1109/TSC.2024.3520867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang L, Polato M, Brighente A, Conti M, Zhang L, Xu L. PriVeriFL: privacy-preserving and aggregation-verifiable federated learning. IEEE Trans Services Computing. 2024;18(2):998–1011. doi:10.1109/TSC.2024.3451183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hahn C, Kim H, Kim M, Hur J. VERSA: verifiable secure aggregation for cross-device federated learning. IEEE Trans Depend Secure Comput. 2021;20(1):36–52. doi:10.1109/TSC.2024.3451183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xu Y, Zhang H, Zhao S, Zhang X, Li W, Gao F, et al. Comments on “VERSA: verifiable secure aggregation for cross-device federated learning”. IEEE Trans Depend Secure Comput. 2024;21(4):4297–8. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2023.3272338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Luo F, Wang H, Yan X. Comments on “VERSA: verifiable secure aggregation for cross-device federated learning”. IEEE Trans Depend Secure Comput. 2024;21(1):499–500. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2023.3253082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Bellare M, Goldreich O, Goldwasser S. Incremental cryptography: the case of hashing and signing. In: Advances in Cryptology-CRYPTO’94: 14th Annual International Cryptology Conference; 1994 Aug 21–25; Santa Barbara, CA, USA: Springer. p. 21–5. [Google Scholar]

31. Huang H, Huang T, Wang W, Zhao L, Wang H, Wu H. Federated learning and convex hull enhancement for privacy preserving WiFi-based device-free localization. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(1):2577–85. doi:10.1109/TCE.2023.3342834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tian Y, Wang S, Xiong J, Bi R, Zhou Z, Bhuiyan MZA. Robust and privacy-preserving decentralized deep federated learning training: focusing on digital healthcare applications. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Bi. 2024;21(4):890–901. doi:10.1109/TCBB.2023.3243932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wehbi O, Arisdakessian S, Guizani M, Wahab OA, Mourad A, Otrok H, et al. Enhancing mutual trustworthiness in federated learning for data-rich smart cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(3):3105–17. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3476950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Bottou L. Large-scale machine learning with stochastic gradient descent. In: Proceedings of COMPSTAT’2010: 19th International Conference on Computational Statistics; 2010 Aug 22–27; Paris, France: Springer. p. 177–86. [Google Scholar]

35. Shamir A. How to share a secret. Commun ACM. 1979;22(11):612–3. doi:10.1145/359168.359176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jagielski M, Oprea A, Biggio B, Liu C, Nita-Rotaru C, Li B. Manipulating machine learning: poisoning attacks and countermeasures for regression learning. In: 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2018; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

37. Gentry C, Groth J, Ishai Y, Peikert C, Sahai A, Smith A. Using fully homomorphic hybrid encryption to minimize non-interative zero-knowledge proofs. J Cryptol. 2015;28(4):820–43. doi:10.1007/s00145-014-9184-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2012;25:1097–105. [Google Scholar]

39. Krizhevsky A, Hinton G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. Handb Systemic Autoimmune Dis. 2009;1(4):1–60. [Google Scholar]

40. LeCun Y. The MNIST database of handwritten digits; 1998. [cited 2025 May 7]. Available from: http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/. [Google Scholar]

41. Zhang J, Liu Y, Hua Y, Wang H, Song T, Xue Z, et al. PFLlib: personalized federated learning algorithm library. arXiv:231204992. 2023. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools