Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Efficient One-Way Time Synchronization for VANET with MLE-Based Multi-Stage Update

School of Electrical Engineering, Korea University, Seoul, 02841, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Hwangnam Kim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 84(2), 2789-2804. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066304

Received 04 April 2025; Accepted 19 May 2025; Issue published 03 July 2025

Abstract

As vehicular networks become increasingly pervasive, enhancing connectivity and reliability has emerged as a critical objective. Among the enabling technologies for advanced wireless communication, particularly those targeting low latency and high reliability, time synchronization is critical, especially in vehicular networks. However, due to the inherent mobility of vehicular environments, consistently exchanging synchronization packets with a fixed base station or access point is challenging. This issue is further exacerbated in signal shadowed areas such as urban canyons, tunnels, or large-scale indoor halls where other technologies, such as global navigation satellite system (GNSS), are unavailable. One-way synchronization techniques offer a feasible approach under such transient connectivity conditions. One-way schemes still suffer from long convergence times to reach the required synchronization accuracy in these circumstances. In this paper, we propose a WLAN-based multi-stage clock synchronization scheme (WMC) tailored for vehicular networks. The proposed method comprises an initial hard update stage to rapidly achieve synchronization, followed by a high-precision stable stage based on Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). By implementing the scheme directly at the network driver, we address key limitations of hard update mechanisms. Our approach significantly reduces the initial period to collect high-quality samples and offset estimation time to reach sub-50 s accuracy, and subsequently transitions to a refined MLE-based synchronization stage, achieving stable accuracy at approximately 30 s. The windowed moving average stabilized (reaching 90% of the baseline) in approximately 35 s, which corresponds to just 5.1% of the baseline time accuracy. Finally, the impact of synchronization performance on the localization model was validated using the Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO). The results demonstrate that more accurate conditions for position estimation can be supported, with an improvement about 38.5% in the mean error.Keywords

Time synchronization is an indispensable requirement in Vehicular Ad hoc Networks (VANETs) to ensure reliable and low-latency communication. As networking performance demands continue to increase, maintaining precise synchronization has become a fundamental necessity for guaranteeing key metrics such as low-latency data transmission and high reliability [1,2]. Despite the effectiveness of two-way synchronization techniques in achieving high precision in VANETs with wireless local area networks (WLANs) and wireless sensor networks (WSNs), these methods heavily rely on frequent packet exchanges and persistent, stable connectivity with higher-stratum time sources [1,3]. Therefore, in environments where power constraints limit packet transmission, such as IoT networks, or VANETs where wireless connectivity fluctuates unpredictably due to physical obstructions like tunnels, urban canyons, or indoor environments, packet delivery can be severely restricted [4,5]. Maintaining accurate synchronization presents significant challenges (the position estimation transmission of vehicles is validated through simulation, as detailed in Section 4). To maintain stable time synchronization, a persistent connection with a higher-stratum source, typically an access point (AP), is required. However, in vehicular networks where maintaining continuous connectivity with a specific AP is challenging, this limitation introduces potential synchronization instabilities. Additionally, in VANETs, mission-critical control data, state information, odometry, position data, and sensor data from cameras and other sources must be transmitted and received in a timely manner [6]. As a result, synchronization should not impose additional bandwidth overhead. Similarly, in IoT networks, which primarily consist of low-power devices, two-way synchronization may be impractical due to energy constraints [7]. Under these conditions, one-way synchronization can be considered as a practical and resource-efficient solution that mitigates these constraints [8]. Unlike two-way synchronization, which requires bidirectional communication with access points (APs) or dedicated time servers, one-way synchronization operates passively, allowing nodes to receive timing information without inducing additional network overhead. This makes it particularly suitable for resource-limited IoT deployments and dynamic vehicular networks where sustained infrastructure connectivity cannot be guaranteed.

The latest one-way synchronization methods leverage Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)-based clock skew estimation using the Cramér-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB) to achieve highly precise synchronization, outperforming traditional approaches [9]. This method optimally estimates clock skew in a controlled environment where key variables such as device clock precision, network channel characteristics, and AP clock stability remain consistent. The primary advantage of this approach is that it can achieve highly accurate synchronization using only a few broadcast packets, significantly reducing network load and synchronization overhead. In MLE-based one-way synchronization, timestamps are extracted from received beacon frames, and an estimation model is applied to minimize the impact of transmission delays and jitter. The Gaussian delay model is typically employed to model variable delays, ensuring robustness against network fluctuations. The effectiveness of this method has been widely recognized, particularly in environments where precise synchronization is necessary but bidirectional communication is costly or impractical.

Given these challenges, one-way synchronization is often adopted as a practical alternative; however, it also has inherent limitations. While MLE-based estimation provides gradual and stable clock updates, achieving an accurate clock skew estimation requires multiple synchronization cycles. This issue becomes even more pronounced in the presence of unstable clock sources affected by power constraints, channel conditions, and mobility, further delaying the synchronization process. In particular, when the clock source is unreliable due to fluctuations in power availability, network congestion, or frequent handovers between APs, synchronization becomes less responsive and more prone to errors. To address these challenges, we propose an aggressive clock update strategy during the initial synchronization stage. This approach is inspired by network time protocol (NTP)’s polling interval, where frequent updates occur in the early stages to achieve rapid convergence before transitioning to longer intervals for stability [10]. By introducing an additional synchronization stage before MLE-based estimation, we aim to improve synchronization efficiency in dynamic environments. We analyze the causes of beacon frame reception instability from unreliable clock sources and introduce a multi-stage synchronization approach. Specifically, we propose a multi-stage WLAN-based synchronization scheme that integrates a hard update-based smooth landing mechanism with adaptive sampling and filtering techniques. This method is designed to optimize synchronization performance in highly dynamic wireless environments. Our proposed scheme consists of an initial hard update for clock correction, followed by gradual adjustments using MLE-based filtering. (1) We analyze the problem of heterogeneous beacon frame reception in one-way time synchronization during the initial access stage under intermittent connectivity. (2) The system first applies an initial hard update by directly setting the system clock to the minimum offset value observed from received beacon frames, rather than conservatively updating clock differences through skew or drift estimation. This ensures a rapid initial correction, reducing the time required for synchronization convergence. (3) Once the initial correction is applied, WMC seamlessly carries forward the samples collected during the initial stage into the MLE-based estimation, which then gradually refines clock skew to maintain stability while Gaussian modeling of delay minimizes synchronization errors over time. Additionally, the synchronization rate is dynamically adjusted based on network conditions, ensuring robustness in environments with intermittent connectivity. By implementing this multi-stage approach, synchronization performance is significantly improved, particularly in vehicular networks, where maintaining stable AP access is challenging. Our method enhances both short-term and long-term synchronization accuracy while also minimizing computational and network overhead.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review typical studies of clock synchronization and those specifically for vehicular networks. Section 3 describes the architecture of the proposed clock synchronization method and presents a problem with sample freshness. In Section 4, we evaluate the performance of the proposed system. Finally, the conclusion is given in Section 5.

This section describes time synchronization methods and the related work on message-based exchanges in wireless networks. Additionally, it discusses previous works on one-way time synchronization and their limitations associated with the proposed study.

Message-based time synchronization in wireless networks is primarily achieved through either one-way or two-way message exchanges [11,12]. This approaches are commonly adopted in hierarchical classifications, divided by stratum (a hierarchically lower stratum serves as the reference clock), where synchronization occurs between servers and clients at different levels. As illustrated in Fig. 1, a server (

Figure 1: One-way time synchronization process

Meanwhile, the server and client inherently maintain independent clocks, differing in resolution and performance. This discrepancy leads to the phenomenon known as clock drift. Clock drift arises due to frequency differences between the client and server clocks (

There are several motivations for applying one-way synchronization in real-world systems. Huan et al. [7] target low-power IoT networks with a looped sample-mean (LSM) broadcast scheme but do not evaluate convergence behavior. Shim et al. [13] apply a lightweight NTP-based method for UAV networks, yet likewise omit any analysis of synchronization convergence time. Shi et al. [8] proposed a one-way synchronization technique based on broadcast messages from edge nodes connected to wired infrastructures (e.g., base stations or APs). Wang et al. [14] later introduced the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE) as a lightweight alternative to MLE, but noted that its initial convergence speed is slower than that of MLE. Nonetheless, neither work provides a concrete strategy for optimizing convergence speed until the clock is stably adjusted. Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) is a well-established technique whose convergence behavior can be indirectly inferred from the number of iterations required [15]. Guchhait and Karthik. [16] model the network delay as a Gaussian random variable and derive the corresponding Cramér–Rao lower bound (CRLB) to quantify the minimum estimation error; they demonstrate this bound in simulation by varying the number of message iterations. Wang et al. [9] present a hybrid one-way scheme that includes reverse-direction messaging—allowing convergence to be assessed via synchronization accuracy over iterations—but this approach still does not yield a direct measure of absolute convergence time. By contrast, consensus-based time synchronization protocols have begun to address convergence speed explicitly. Shi et al. [17] propose an iterative message exchange method that accelerates convergence in wireless sensor networks, and Wang et al. [18] most recently present a two-way packet exchange scheme that improves convergence speed under high-delay conditions. However, comparable strategies for rapid convergence in one-way MLE-based synchronization remain unexplored. The related works mentioned above are summarized in Table 1.

3 WMC: Proposed Time Synchronization Model

This section presents the design methodology of WMC, a multi-stage one-way time synchronization approach that enables fast convergence in the initial stage and long-term stability in the stable stage under dynamic wireless environments. In Sections 3.2 and 3.3, we describe the stage–specific methodologies for the initial and stabilization phases, respectively, each tailored to its objectives and connected through a cohesive, seamlessly integrated process. We first discuss how beacon sequence omissions and stochastic reception delays across nodes introduce heterogeneity in the initial stage, leading to instability in early offset estimation. To address this, we describe a hard update-based sampling and filtering method that quickly stabilizes offset samples by rejecting outliers and applying median-based filtering. In the subsequent stabilization stage, we introduce a procedure to estimate clock offset and skew using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), and then perform adaptive clock compensation. The section concludes by explaining how a smooth transition from the initial stage to the MLE-based stable stage ensures both synchronization precision and robustness against transient network fluctuations.

3.1 Heterogeneity in Beacon Reception Timing

In wireless environments, beacon frames are periodically broadcast from the access point (AP) to multiple receiving nodes for one-way synchronization. However, due to the inherent nature of wireless propagation, several challenges arise in how these beacons are received across different nodes. Despite being transmitted simultaneously from the same AP, nodes may receive different beacon sequence numbers or, in many cases, even when the same sequence number is received, they experience heterogeneous delays caused by varying channel conditions, interference, or hardware-specific reception timing. This phenomenon is illustrated in Fig. 2, where the perceived beacon timing at each node differs from the reference due to stochastic transmission delay and reception offset. Such heterogeneity in beacon reception leads to inconsistencies in estimating the timing offset (

Figure 2: Heterogeneity in beacon frame arrival

This heterogeneity affects synchronization accuracy in two critical ways. First, when different nodes receive different beacon sequence numbers, each node references a different AP timestamp

3.2 Hard Update-Based Sampling and Filtering Algorithm

The process of sampling and filtering this temporal data is implemented as shown in Algorithm 1. First,

To quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed time synchronization method in reducing the time difference between two nodes, we compared it to a pure hard update approach. The analysis consists of three steps: first, we define the time model of the beacon frame transmitted from the AP; second, we construct a mathematical model of direct BF-based time updating, which serves as a baseline approach; and third, we analyze how the proposed method improves synchronization stability and precision. We define a random variable for the

The most recent valid received time at the node, incorporating reception success probability, is defined as:

For a given sequence of received time values, the expected latest valid time error is derived as:

The inter-node time difference is then given by:

To compare the variance reduction effect of the proposed method, we analyze the median-based filtering process. The median estimation follows:

where

Given that the received time errors

As a result, the proposed system reduces time error variance to about

3.3 MLE-Based Estimation and Adaptive Clock Correction

To enhance synchronization accuracy in one-way communication environments, we apply Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) to estimate both the clock offset and clock skew. In dynamic wireless networks, the observed timing offset between the access point (AP) and receiving node is influenced not only by the true clock difference but also by stochastic transmission delays, which vary due to channel conditions and system load.

Building on the median-filtered samples

This offset includes both the actual clock offset

Given a collection of such samples, we estimate the optimal offset

To further track the clock skew

Unlike static averaging, this method allows for continuous adaptation, making it suitable for environments with fluctuating delay and mobility. The estimated

Once a rapid convergence is achieved through the initial hard update mechanism described earlier, the synchronization process transitions into this MLE-based estimation stage. In this stage, adaptive sampling and lightweight filtering are applied to mitigate transient delay fluctuations, and clock correction is performed gradually to ensure smooth tracking of the reference time. This approach contributes to overall stability and robustness of the synchronization system under real-world wireless dynamics.

In this section, we compare the synchronization performance of WMC with two approaches; one based on a one-way synchronization method using an MLE-based hard update, and the other based on a two-way synchronization method implemented by Chrony. We employ a WLAN network interface card (NIC) attached to an access point (AP), serving as a low-quality clock source. Two single-board computers (SBCs), suitable for deployment on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), are equipped with identical NICs and act as client nodes. The client devices are two Odroid XU4 boards running Ubuntu 18.04 with Linux kernel 4.14. The network driver is based on the RTL8812AU chipset. All synchronization schemes (WMC, MLE, and Chrony) are identically deployed on both devices. To evaluate timing accuracy, we measure the output pulses generated by the pps_gen_gpio driver and emitted through general purpose input/output (GPIO) pins, using a Tektronix TBS1102B-EDU digital oscilloscope, which provides a sample rate of

Any packet transmission-based scheme inherently incurs overhead. Data rates must be considered for practical VANET deployment. Therefore, we present each estimated data rate in its formulated expression along with practical parameter ranges. The data rate of Chrony (

where

where

4.1 Clock Offset Analysis in the Synchronization Process

The clock offset refers to the time difference between two devices for the same nominal second, expressed as

Figure 3: Logistic regression of clock offset during the initial stage

4.2 Clock Synchronization Error Analysis

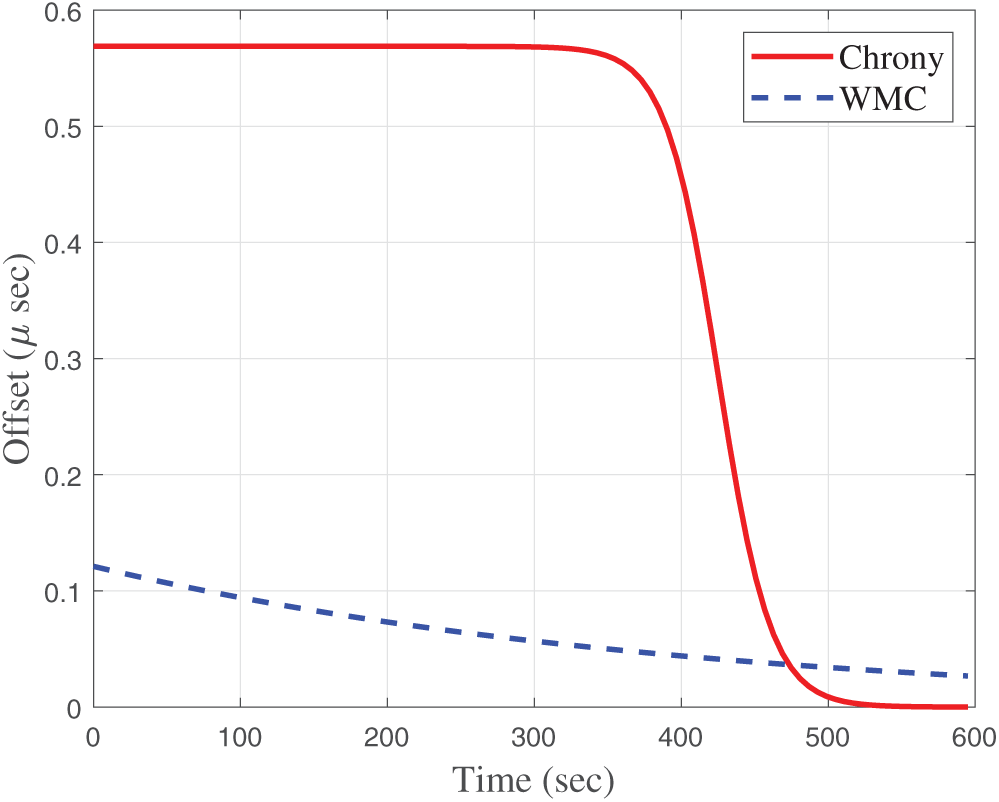

This subsection analyzes how accurately the two clients were synchronized to the server. For a fair comparison, the proposed WMC scheme is evaluated alongside a one-way synchronization method based on MLE with hard updates and a two-way synchronization method implemented by Chrony. The difference between the clocks of the two clients,

Figure 4: Clock error during the initial stage

Figure 5: Clock error between two clients

Therefore, the results in Figs. 4 and 5 demonstrate that, in vehicular networks where WLAN-based synchronization is often transient and unstable, a hard update-based multi-stage approach is effective in achieving rapid convergence toward operational synchronization accuracy.

4.3 Vehicle-Based Time Offset Effects on Localization

This subsection presents a simulation-based evaluation examining how time synchronization accuracy influences position estimation performance in vehicular communication systems. The experiment was conducted using the simulation of urban mobility (SUMO) simulator on an urban canyon map with dense building structures, as shown in Fig. 6a. Six and sixty vehicles were deployed on a closed-loop road approximately

Figure 6: Simulation environment (SUMO)

Figure 7: Fréchet distance between ground truth and offset trajectories

Figure 8: Positional estimation under different synchronization stages (6/60 vehicles)

To provision emergency time synchronization in vehicular networks where primary clock sources may become unavailable, we proposed WMC, a one-way time synchronization method based on WLAN broadcasts. For the design of WMC, we analyzed the timing uncertainty caused by the departure of beacon frames from the server and their arrival at each individual client, dividing the process into an initial stage and a stable stage. In the initial stage, we proposed an approach that reflects the effects of beacon sequence omissions and reception delay variation. For the stable stage, we applied a hard update mechanism based on Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), one of the most widely used techniques in time synchronization. Experimental results show that WMC reduces convergence time more effectively than Chrony and MLE-based hard updates under initial conditions. Furthermore, the transition to MLE in the stable stage achieves a synchronization accuracy of 34.49

As future work, we plan to investigate how WMC can complement widely used synchronization protocols such as Chrony and the Precision Time Protocol (PTP) in a hybrid or cooperative synchronization framework.

Acknowledgement: We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the editor and reviewers for their valuable feedback and constructive comments, which greatly improved the quality of this paper.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE) (No. 20224B10300090) and also supported by the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Republic of Korea, under the ITRC (Information Technology Research Center) support program (IITP-2025-RS-2021-II211835) supervised by the IITP (Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hyeontae Joo and Hwangnam Kim; methodology, Hyeontae Joo and Hwangnam Kim; software, Hyeontae Joo and Kiseok Kim; validation, Hyeontae Joo, Kiseok Kim and Hwangnam Kim; formal analysis, Hyeontae Joo and Sangmin Lee; investigation, Hyeontae Joo and Kiseok Kim; resources, Hyeontae Joo; data curation, Hyeontae Joo and Sangmin Lee; writing—original draft preparation, Hyeontae Joo, Sangmin Lee, kiseok Kim and Hwangnam Kim; writing—review and editing, Hyeontae Joo and Hwangnam Kim; visualization, Hyeontae Joo; supervision, Hwangnam Kim; project administration, Hwangnam Kim; funding acquisition, Hwangnam Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing not applicable.

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve human participants or animal subjects. Ethical approval is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Romanov AM, Gringoli F, Sikora A. A precise synchronization method for future wireless TSN networks. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020;17(5):3682–92. doi:10.1109/tii.2020.3017016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Seijo O, Lopez-Fernandez JA, Val I. w-SHARP: implementation of a high-performance wireless time-sensitive network for low latency and ultra-low cycle time industrial applications. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020;17(5):3651–62. doi:10.1109/tii.2020.3007323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mahmood A, Ashraf MI, Gidlund M, Torsner J, Sachs J. Time synchronization in 5G wireless edge: requirements and solutions for critical-MTC. IEEE Commun Magaz. 2019;57(12):45–51. doi:10.1109/mcom.001.1900379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Guo X, Liu K, Meng Z, Li X, Yang J. Pseudolite-based lane-level vehicle positioning in highway tunnel. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;25(2):1612–24. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3314520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bozorgzadeh E, Barati H, Barati A. 3DEOR: an opportunity routing protocol using evidence theory appropriate for 3D urban environments in VANETs. IET Commun. 2020;14(22):4022–8. doi:10.1049/iet-com.2020.0473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Azhdari MS, Barati A, Barati H. A cluster-based routing method with authentication capability in Vehicular Ad hoc Networks (VANETs). J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2022;169(12):1–23. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2022.06.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Huan X, Chen W, Wang T, Hu H, Zheng Y. A one-way time synchronization scheme for practical energy-efficient lora network based on reverse asymmetric framework. IEEE Trans Commun. 2023;71(11):6468–81. doi:10.1109/tcomm.2023.3305515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Shi F, Li H, Yang SX, Tuo X, Lin M. Novel maximum likelihood estimation of clock skew in one-way broadcast time synchronization. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2019;67(11):9948–57. doi:10.1109/tie.2019.2955427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang H, Gong P, Yu F, Li M. Clock offset and skew estimation using hybrid one-way message dissemination and two-way timestamp free synchronization in wireless sensor networks. IEEE Commun Lett. 2020;24(12):2893–7. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2020.3019521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Durairajan R, Mani SK, Sommers J, Barford P. Time’s forgotten: using NTP to understand internet latency. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks (HotNets-XIV). New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2015. p. 1–7. doi:10.1145/2834050.2834108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shin M, Park M, Oh D, Kim B, Lee J. Clock synchronization for one-way delay measurement: a survey. In: Kim Th, Adeli H, Robles RJ, Balitanas M, editors. Advanced communication and networking. ACN 2011. Communications in computer and information science. Vol. 199. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2011. p. 1–10. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-23312-8_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lévesque M, Tipper D. A survey of clock synchronization over packet-switched networks. IEEE Commun Surveys Tutorials. 2016;18(4):2926–47. [Google Scholar]

13. Shim H, Joo H, Kim K, Park S, Kim H. Provisioning high-precision clock synchronization between UAVs for low latency networks. IEEE Access. 2024;12:190025–38. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3516856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang H, Lu R, Peng Z, Li M. Clock synchronization with partial timestamp information for wireless sensor networks. Signal Process. 2023;209(3):109036. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2023.109036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Leng M, Wu YC. Low-complexity maximum-likelihood estimator for clock synchronization of wireless sensor nodes under exponential delays. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2011;59(10):4860–70. doi:10.1109/tsp.2011.2160857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Guchhait A, Karthik RM. Joint minimum variance unbiased and maximum likelihood estimation of clock offset and skew in one-way packet transmission. In: 2015 IEEE 81st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring). Glasgow, UK: IEEE; 2015. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/VTCSpring.2015.7145899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Shi F, Tuo X, Ran L, Ren Z, Yang SX. Fast convergence time synchronization in wireless sensor networks based on average consensus. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2019;16(2):1120–9. doi:10.1109/tii.2019.2936518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang H, Zou Y, Liu X, Meng Z. A rapid time synchronization scheme using virtual links and maximum consensus for wireless sensor networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;12(3):3318–29. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3480331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yang P, Duan D, Chen C, Cheng X, Yang L. Multi-sensor multi-vehicle (MSMV) localization and mobility tracking for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2020;69(12):14355–64. doi:10.1109/tvt.2020.3031900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Min H, Li Y, Wu X, Wang W, Chen L, Zhao X. A measurement scheduling method for multi-vehicle cooperative localization considering state correlation. Veh Commun. 2023;44(8):100682. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2023.100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools