Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Research on Multimodal AIGC Video Detection for Identifying Fake Videos Generated by Large Models

1 College of Cyberspace Security, Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

2 Henan Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Situation Awareness, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

3 College of Computer Science and Technology, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310027, China

4 Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

5 State Grid Henan Electric Power Company, Zhengzhou, 450040, China

* Corresponding Author: Tianning Sun. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1161-1184. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.062330

Received 16 December 2024; Accepted 18 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

To address the high-quality forged videos, traditional approaches typically have low recognition accuracy and tend to be easily misclassified. This paper tries to address the challenge of detecting high-quality deepfake videos by promoting the accuracy of Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) video authenticity detection with a multimodal information fusion approach. First, a high-quality multimodal video dataset is collected and normalized, including resolution correction and frame rate unification. Next, feature extraction techniques are employed to draw out features from visual, audio, and text modalities. Subsequently, these features are fused into a multilayer perceptron and attention mechanisms-based multimodal feature matrix. Finally, the matrix is fed into a multimodal information fusion layer in order to construct and train a deep learning model. Experimental findings show that the multimodal fusion model achieves an accuracy of 93.8% for the detection of video authenticity, showing significant improvement against other unimodal models, as well as affirming better performance and resistance of the model to AIGC video authenticity detection.Keywords

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) technology has developed rapidly, and large generative models based on generative adversarial networks (GANs) have maturely developed and widely applied [1,2]. GAN uses an adversarial training strategy to make the generator and discriminator compete with each other and update continually to enhance image generation quality [3]. GAN technology has driven great development in image, audio, and video content creation of AI technology [4]. However, challenges for the development of AIGC technology are also emerging [5]. High-quality synthetic videos can be used for creative entertainment, meanwhile, false information can also be fabricated using synthetic videos to falsify facts and threaten social stability [6]. With the further development of fake video technology, security, and trust issues brought by fake video technology have gradually become prominent. There is an urgent need to research fake video detection and countermeasures to ensure information authenticity and social security [7]. Traditional detection methods primarily rely on visual cues, which present significant limitations when dealing with high-quality fake videos [8,9]. Since AIGC generates content including multiple modalities such as image, audio, and text, it is hard to use a single modality detection method. Therefore, the fake video detection method based on multimodal information fusion (MMIF) (fusion of multiple information sources such as vision, audio, and text) has become a key issue that needs to be solved urgently [10]. MMIF technology can be used to analyze the consistency and correlation of multiple information sources such as vision, audio, and text, and improve the accuracy and robustness of detection. It can also make up for the deficiency of single-modal method [11]. It can be used to enhance the ability to identify complex forgery behaviors and provide technical support for future anti-forge methods. It is of great significance to maintaining information security and social trust [12,13].

There has been a great development in the video forgery detection field, but there are still many deficiencies in existing research. At present, mainstream video detection algorithm includes deep learning model based on visual information, frequency domain feature analysis methods, and models based on temporal information. Among them, CNN and GAN perform well in visual feature extraction and forged image recognition, and can effectively deal with image forgeries in videos. However, these methods usually rely on single-modal visual information and fail to fully consider the audio and text forgeries that may exist in forged videos. As a result, the detection ability of single-modal methods is very limited when dealing with multimodal forged videos. Existing algorithms often exhibit poor robustness and accuracy when processing multimodal forged videos, and comprehensive detection of forged content remains a major challenge.

This study uses MMIF methods to improve the authenticity detection of AIGC videos, in order to cope with completely forged videos generated by large models. By collecting high-quality multimodal video datasets, standardization processing such as resolution adjustment and frame rate unification can be applied to videos. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) can be used to extract visual features from video datasets; audio features can be extracted through short-time Fourier transform and Mel frequency cepstral coefficients; text features can be obtained through natural language processing techniques. Based on the multi-layer perceptron and attention mechanism, the extracted visual, audio, and text features are fused to construct a multimodal feature matrix. This study constructs and trains a multimodal deep learning model, introduces an MMIF layer, and classifies and recognizes completely fake videos generated by large models. This study compares the multimodal fusion model with the single modal CNN model, GAN model, and Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM) model, and analyzes the performance differences between the multimodal fusion model and the single modal model by evaluating their accuracy in identifying fake videos and various performance indicators. After experimental verification, the model proposed in this study outperforms the single modal model in both detection accuracy and robustness and performs outstandingly in dealing with high-quality complex forged videos. This study provides an effective solution for the authenticity detection of AIGC videos and offers new ideas and technical support for research in related fields.

Currently, the academic community is actively exploring a variety of video authenticity identification technologies. The Tyagi team [14] systematically sorted out the mainstream visual processing technologies, image and video tampering types and cutting-edge detection methods, providing a theoretical basis for related research. Kaur and Jindal [15] innovatively applied deep convolutional neural networks (DNNs) to analyze the correlation between video frames and accurately locate tampered frames by identifying abnormal patterns. The video content similarity analysis algorithm developed by Wei’s research group [16] can effectively identify tampering behaviors such as frame duplication, insertion, and deletion, and is compatible with video detection in different encoding formats. In the field of digital authentication, Ghimire et al. [17] pioneered the combination of elliptic curve encryption, hash message authentication and blockchain technology to build a new video integrity verification system. In the dual detection algorithm proposed by Singh’s research team [18], Algorithm 1 realizes tampering detection through frame feature mean analysis, and algorithm 2 uses threshold judgment technology to accurately locate the tampered area. For social network scenarios, Hu et al. [19] designed a dual-stream analysis model specifically for identifying compressed deep fake videos. Although the above research has made progress in specific areas, the existing methods still have limitations in the following aspects when facing the highly realistic videos generated by AIGC technology: 1) the recognition ability of multimodal tampering features (MMIF) is insufficient; 2) the comprehensive detection accuracy needs to be improved. In particular, with the rapid development of generative AI technology, the means of video forgery are becoming more and more complicated, which poses new challenges to detection technology.

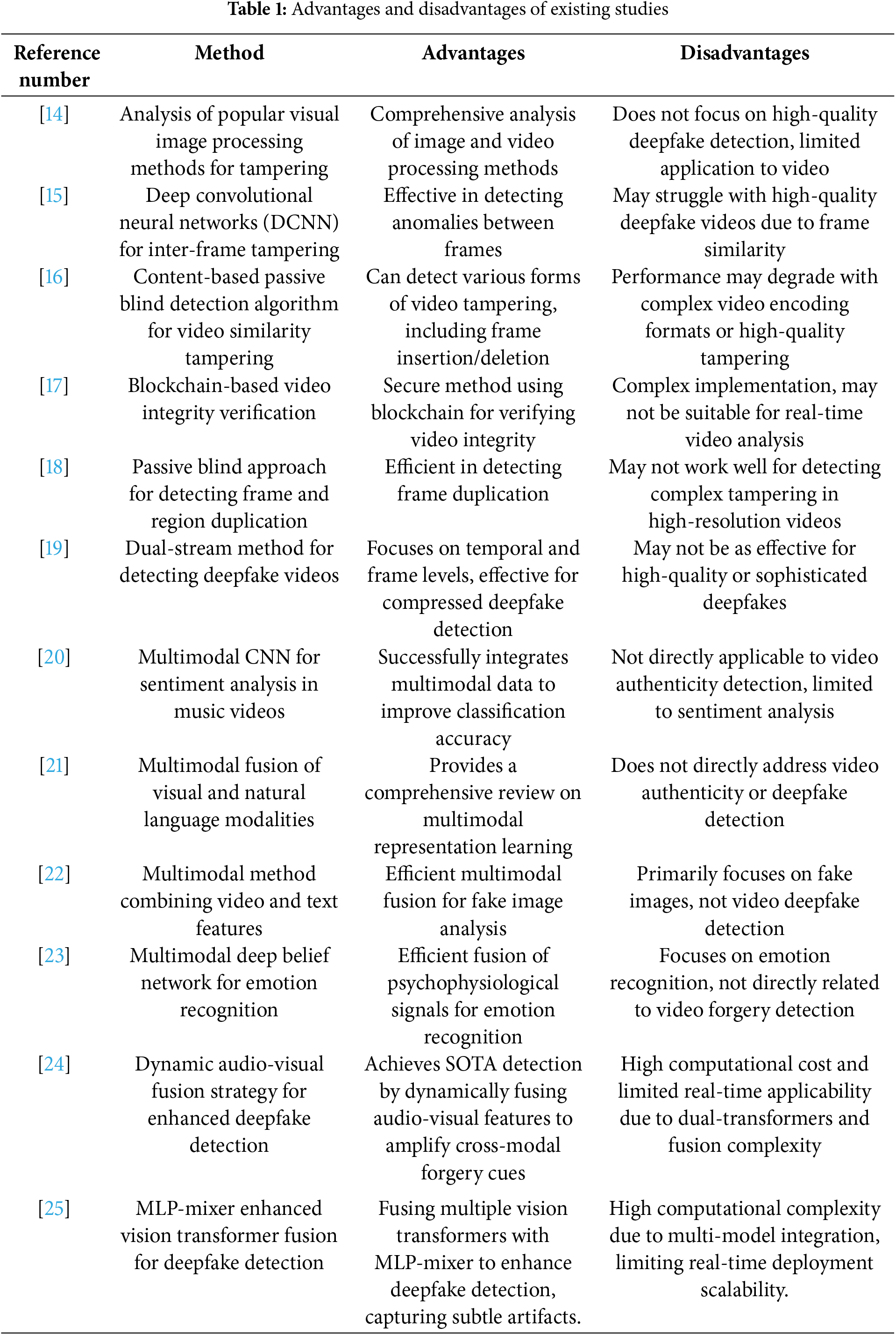

Some studies have shown that MMIF has great potential in solving complex detection problems. Pandeya and Lee [20] successfully improved the accuracy of sentiment analysis by constructing a diverse music video sentiment dataset and combining it with a multimodal CNN, significantly improving the automatic classification of human emotions with a small amount of labeled data. Zhang et al. [21] analyzed the combination of visual and natural language modalities in multimodal intelligence through a comprehensive technical review covering multimodal representation learning, fusion, and applications. Singh and Sharma [22] proposed an efficient multimodal method that combined video and text features to perform image analysis and text analysis on fake images on the network platform using the explicit CNN model EfficientNetB0 and sentence converter, respectively. Wang et al. [23] proposed an emotion recognition method that utilized a multimodal deep belief network to fuse multiple psychophysiological signal features, focusing on representative visual features in video stream features using a bimodal deep belief network. Wang et al. [24] proposed AVT²-DWF, a multimodal framework combining audio-visual transformers with dynamic weight fusion, which enhanced detection performance by adaptively aligning cross-modal forgery cues. Essa [25] proposed a feature fusion framework that combines three Vision Transformers (DaViT, iFormer, GPViT) with MLP-Mixer to enhance deepfake detection. By integrating local-global visual contexts, frequency spectrum broadening, and high-resolution feature retention, this method improves performance on the FaceForensics++ and Celeb-DF datasets. Additionally, it demonstrates effectiveness in detecting subtle synthetic manipulations in AI-generated videos. The MMIF framework fundamentally differs from mainstream visual methods. Compared to the single-modal attention mechanism of Vision Transformers, MMIF dynamically integrates visual, audio, and text features across modalities through dynamic weighting, aligning more closely with human multi-sensory cognitive principles. Unlike the local feature aggregation in semantic segmentation models like U-Net, MMIF simultaneously captures spatiotemporal features and cross-modal associations. In contrast to StyleGAN’s style transfer, MMIF extracts orthogonal features based on physical acoustics and semantic understanding, effectively identifying inter-modal contradictions in generated content. As can be seen from the above, MMIF methods perform well in video detection, but there are still issues of insufficient accuracy and robustness in AIGC video authenticity detection. Therefore, this study proposes the MMIF framework based on deep learning, which improves the detection performance and robustness of AIGC videos through joint analysis of multimodal information such as video, audio, and text. The existing research is summarized in Table 1.

3 Detection Framework Based on MMIF

In order to improve the accuracy of AIGC video authenticity detection, this paper uses a detection framework based on multimodal information fusion. The framework aims to comprehensively utilize the information of three modalities, namely vision, audio, and text, and realize the effective identification of forged videos in a multimodal context through multimodal feature extraction, fusion, and construction and training of deep learning models. The framework’s overall process mainly includes three stages: feature extraction, feature fusion, and construction, as well as training of multimodal deep learning models. In the feature extraction stage, video features that are helpful for detection are extracted from the visual, audio, and text modalities, respectively, laying the foundation for the subsequent multimodal information fusion; in the feature fusion stage, multi-layer perceptrons and attention mechanisms are used to fuse features of different modes and make use of the complementarity of information of each mode; in the construction and training stage of deep learning model, deep learning model is designed and optimized to improve the accuracy and robustness of video authenticity detection.

In order to improve the authenticity identification ability of AIGC-generated videos, this study adopts a multimodal feature fusion strategy to extract key features from three dimensions: vision, audio, and text [26]. In the visual feature extraction stage, a framework based on convolutional neural network (CNN) is used to analyze the authenticity of the video content. The specific implementation process includes: first, preprocessing the original video, converting the video stream into a continuous frame sequence through fixed frame rate sampling; then, normalizing the size of the acquired video frames to meet the network input requirements; then using the pre-trained ResNet-50 deep residual network to complete spatial feature extraction; finally, the long short-term memory (LSTM) network is used to model the temporal relationship between frames, and the feature sequence extracted by CNN is used as the input of LSTM. The calculation process can be expressed as:

In Formula (1),

In the audio feature extraction phase, this study uses a multi-stage signal processing method to obtain feature parameters that characterize the authenticity of the audio from the video [27,28]. First, the original speech signal is pre-emphasized, and a first-order finite impulse response filter is used to enhance the high-frequency component and correct the high-frequency loss of the speech signal during transmission. The subsequent processing flow includes: signal frame processing, Hamming window function windowing, short-time Fourier spectrum analysis, and finally the cepstral coefficient feature is extracted through the Mel-scale filter group. The specific implementation formula is:

In Formula (2),

The pre-emphasized audio signal can be divided into frames of a certain length, with a certain overlap between each frame, to ensure the smoothness of subsequent feature extraction. If the frame shift is set to

Among them,

Window operation can be applied to each frame signal after segmentation to reduce spectral leakage, improve the accuracy of spectral estimation, and effectively suppress boundary effects. A smooth transition can reduce the discontinuity caused by signal truncation and improve the quality of subsequent speech processing and analysis. This study uses the Hamming window to perform windowing processing on the segmented signal. The window function is defined as follows:

The windowed audio signal is represented as:

The short-time Fourier transform is performed on the windowed audio signal, and the time-domain signal is converted into a time-frequency domain representation. Instantaneous frequency changes are captured, and the frequency characteristics of the audio signal are revealed. For each frame signal, the STFT transformation formula is expressed as follows:

Among them,

The Mel frequency cepstral coefficients of each frame signal is calculated. The spectral energy obtained from STFT is converted into the Mel frequency scale, mapping Hertz to Mel, and defining Mel frequency scale as:

A Mel filter bank is designed to map spectral energy onto the Mel frequency scale. The output formula of the Mel filter is expressed as follows:

In Formula (8),

After mapping the spectral energy onto the Mel frequency scale, logarithmic transformation is performed on the energy on the scale, and the MFCC coefficients are obtained through Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) [29]. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

In Formula (9),

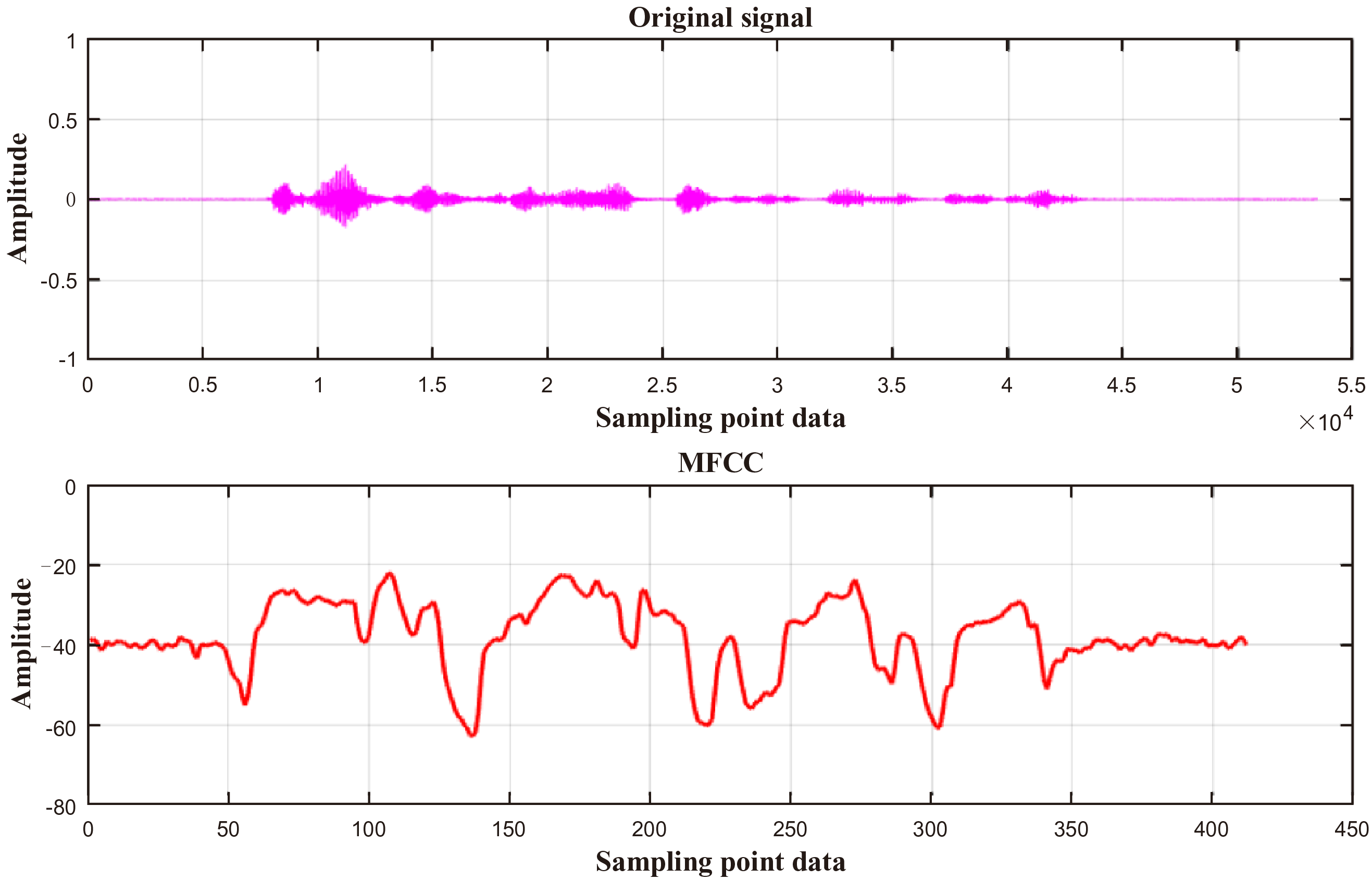

Fig. 1 is a schematic diagram of extracting MFCC coefficients from partial audio signals.

Figure 1: MFCC coefficient extraction of audio signal

Fig. 1 shows the result of extracting the audio signal through MFCC, with the horizontal axis representing the sampling points and the vertical axis representing the amplitude. The specific sentence for the audio signal in the picture is THE WANDERING SINGER APPROACHES THEM WITH HIS LUTE. The audio signal has a sampling rate of 16,000 Hz, a frame length of 512, a frameshift of 128, and a pre-emphasis coefficient of 0.97. Additionally, the frames are windowed using a Hamming window. The original audio signal has a total of 53,440 sampling points, and the audio signal extracted by MFCC has a total of 414 sampling points. The significant advantage of MFCC feature extraction is that it can greatly reduce the number of raw data points while preserving key speech features. Audio signals are usually captured at high sampling rates and contain a large number of raw data points. Directly processing these data points is computationally complex and not conducive to real-time applications. Through MFCC feature extraction, thousands or even tens of thousands of raw data points can be compressed into hundreds of feature data points. This greatly reduces data dimensionality and computational complexity, reduces storage and processing consumption, and effectively improves the efficiency of subsequent audio recognition and algorithm processing.

In this study, for text feature extraction, Natural Language Processing (NLP) technology is employed to extract features indicative of video content authenticity from descriptions or subtitles [30]. Removing punctuation marks, numbers, and stop words, and converting all characters into lowercase are performed in pre-processing the original descriptive text or subtitles. This may assist in removing noise and improving the accuracy of subsequent feature extraction. Word embedding techniques can be utilized to embody features of preprocessed text in the form of high-dimensional vectors. To extract deeper semantic information from text, we employ a pre-trained Transformer model, specifically BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [31]. BERT captures contextual relationships between words through a bidirectional attention mechanism, generating richer text features. The feature matrix output by BERT can be pooled to further integrate text features. The average pooling method is used on the feature matrix, and the final text feature representation is:

Among them,

To extract video features, both the LSTM network and CNN are utilized in combination. Firstly, the visual features of each frame are extracted by CNN, and the video frames are passed to the pre-trained ResNet-50 model in order to learn accurate image features. Next, the LSTM network is introduced in order to take into account the temporal relationship of frames of the video, acquiring the temporal features of the video. This method has the capability to effectively identify unusual visual variations in forged videos, especially in high-definition forged videos, where it can detect fine frame discrepancies.

In audio feature extraction, the study extracts prominent audio features through a series of processing steps, including pre-emphasis, framing, windowing, Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), and MFCC extraction. The MFCC extraction significantly compresses the dimension of the audio data, thereby reducing computational complexity while preserving valuable audio information. Consequently, this enhances the recognition capability for detecting forged audio.

In terms of audio feature extraction, significant audio features are extracted through a series of processing steps, including pre-emphasis, framing, windowing, short-time Fourier transform (STFT), and MFCC extraction. MFCC extraction significantly compresses the dimension of audio data. In terms of text feature extraction, natural language processing (NLP) technology and the BERT model are used.

Multimodal information fusion (MMIF) technology plays an important role in video authenticity detection. It comprehensively analyzes the video content by combining feature information from different sources. This study uses a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to integrate visual and audio features and uses a back-propagation algorithm to enhance the correlation between features, thereby improving the fusion quality [32]. In the specific operation, the features of the two modalities are first connected into a combined feature vector and then sent to the MLP for nonlinear transformation and feature extraction, and finally, a fusion feature with higher discrimination is obtained.

For multimodal fusion tasks including vision, audio, etc., the research team designed a dynamic weighting method based on the attention mechanism [33]. This method uses a feedforward neural network to evaluate the importance of each modality and then converts the score into a standardized attention weight through a softmax function to complete the intelligently weighted fusion of features. This strategy can automatically identify the contribution of different modalities in authenticity discrimination and effectively optimize the expression ability of multimodal features. Experimental results show that by utilizing the complementary characteristics between multimodal data, this method has achieved a significant improvement in the accuracy of generative fake video recognition.

In the MMIF system, the key role of the attention mechanism is reflected in its ability to dynamically screen the core information of each modality. When processing auxiliary features such as vision and audio, the mechanism uses a trainable neural network to evaluate the importance of the modality and converts it into a standardized weight through a softmax function. This structural design enables the model to autonomously focus on the most discriminative feature level, thereby establishing a more stable multimodal representation system.

After adopting the attention mechanism, the system’s ability to identify complex forged content is significantly enhanced. By extracting decisive evidence from multiple modalities, this method can more accurately determine the authenticity of the video. In particular, when identifying generative forged videos, the joint analysis of multimodal features provides a more complete basis for judgment, which ultimately substantially improves the detection effect.

3.3 Construction of Multimodal Deep Learning Models

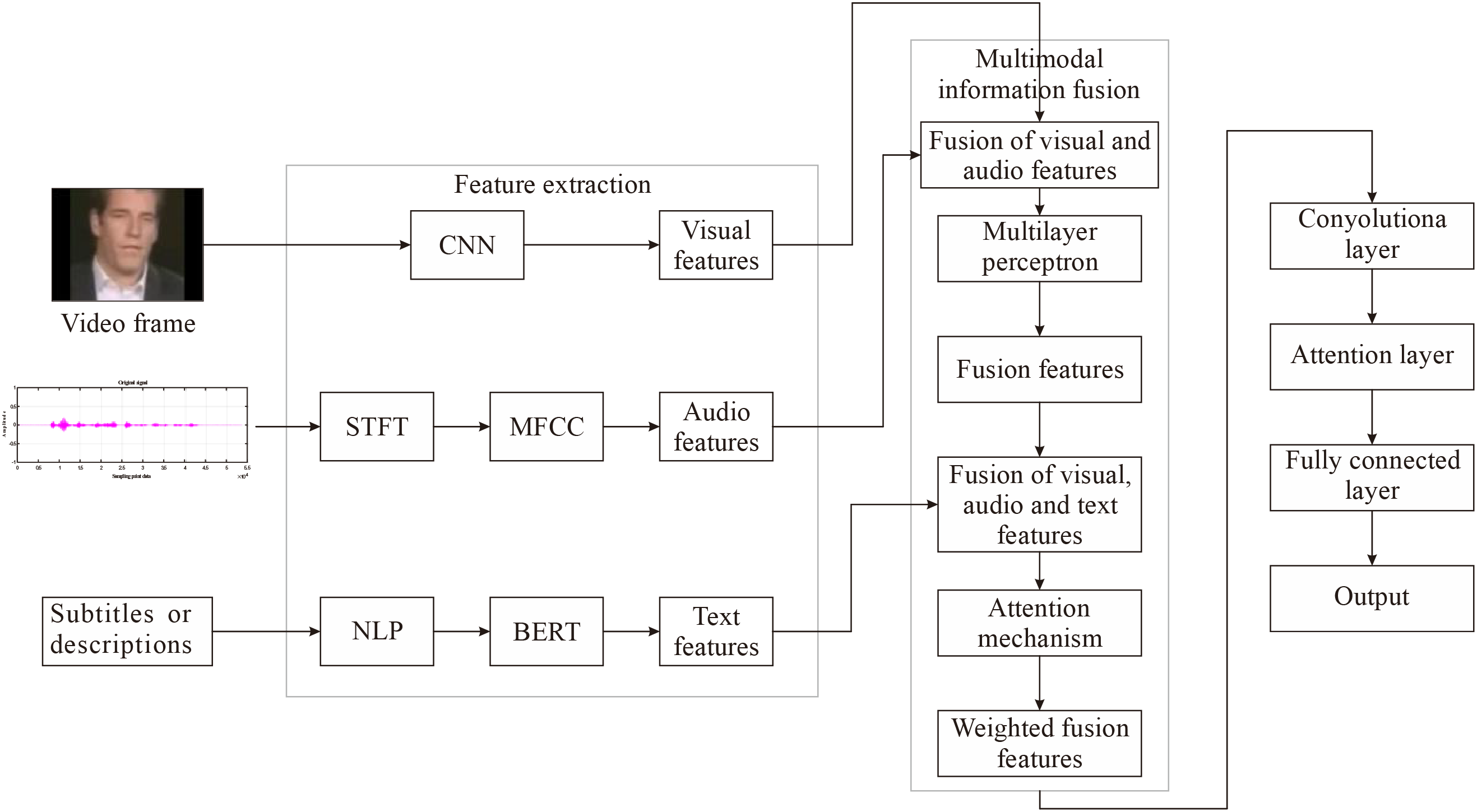

In the model construction stage, this study focuses on designing and optimizing multimodal deep learning models to improve the detection accuracy of AIGC video authenticity. The core of model construction lies in introducing the MMIF layer, which effectively integrates visual, audio, and text features, fully utilizing the correlation and complementarity between different modalities. This study adopts a deep neural network structure that can simultaneously process and fuse data from multiple information sources. Fig. 2 shows the process of constructing a multimodal deep-learning model.

Figure 2: Construction process of multimodal deep learning model

Fig. 2 shows the model’s construction process in this study. During the model design process, the feature representations of each modality input are extracted through different methods. CNN can be used to extract visual features from video frames, while audio features from audio signals through short-time Fourier transform and Mel frequency cepstral coefficients, and text features from video subtitles using natural language processing techniques and BERT models. These features are used as inputs for the model, and after preprocessing and feature extraction steps, they are passed into the MMIF layer. The design of the MMIF layer includes multilayer perceptrons and attention mechanisms. A multilayer perceptron is used to preliminarily fuse and transform visual and audio features at the feature level, adapting to subsequent deep learning. The attention mechanism dynamically adjusts the importance of different modal features and weights the fused features and text features according to their respective contributions to form the final multimodal feature representation. The fused multimodal feature representation is processed through the convolutional layers of the model for further processing of the fused features. The attention layer is used to enhance the model’s attention to different features and better integrate multimodal information, and the final fully connected layer is used to perform video classification tasks, mapping the processed features to the final output space.

In this study, the fusion process uses an MLP and an attention mechanism to achieve multimodal information fusion of visual, audio, and text features. First, in the MLP, the input features come from the individual extraction of each modality. The features of each modality are preprocessed and then input to different levels of the MLP for weighted combination. The MLP learns the complex relationship between features through the back-propagation algorithm to further optimize the model performance. During the training process of the model, appropriate hyperparameters are selected to adjust the structure of the MLP, including the number of layers, the number of neurons in each layer, and the learning rate.

At the same time, the attention mechanism is applied to further enhance the fusion effect, especially when processing multimodal data, which can effectively identify which modalities contribute more in certain videos. When applying the attention mechanism, a weighting mechanism based on the softmax function is used to calculate the attention weights of each modality. These weights play a vital role in the feature fusion process, ensuring that the model can improve accuracy when focusing on the most important modality.

The fusion strategy of MLP and attention mechanism adopted in this paper realizes the efficient utilization of information complementarity by processing multimodal features in stages. In the feature fusion stage, MLP first performs nonlinear transformation on visual and audio features to learn the complex interaction between modalities, while the attention mechanism dynamically assigns weights to different modalities (such as text, vision, and audio) to highlight the modal contribution that is critical to the detection task. Compared with the traditional late fusion strategy, the combination of MLP and attention mechanism can capture high-order dependencies across modalities and avoid information redundancy between modalities. In addition, compared with the method that relies only on fixed weight fusion, the attention mechanism better copes with the dynamic changes of multimodal forgery clues in AIGC-generated videos by adaptively adjusting the importance of modalities. Compared with other algorithms, this method integrates the complementary information of vision, audio, and text more efficiently through end-to-end modal weight optimization while maintaining low computational complexity through the collaborative design of lightweight MLP and attention mechanism.

3.4 Model Training and Evaluation Criteria

In the model training phase, this study uses the constructed multimodal dataset to train the designed model, with the goal of optimizing model parameters to improve the accuracy of AIGC video authenticity detection. Multimodal datasets contain visual, audio, and text features, which are extracted using corresponding techniques to extract important features. The extracted features are fused and processed through multilayer perceptrons and attention mechanisms. The structural design of deep neural networks considers the heterogeneity and correlation of multimodal features. After several layers of convolution and pooling operations, visual features are transformed into fixed-length feature vectors through fully connected layers. The audio features are extracted using the MFCC method and then converted into fixed-length feature vectors after the same operation. Text features are processed through word embedding layers and BERT models to generate context-relevant feature vectors. Multilayer perceptrons can be used to preliminarily fuse visual and audio features, and text features can be introduced on this basis. Weighted fusion is performed through attention mechanisms to ensure that the contribution of each modal feature in the final fused feature is dynamically adjusted according to its importance.

Parameter optimization is done using the Adam optimizer during the model’s training phase. The Adam optimizer avoids getting trapped in local optima and converges more quickly by combining the benefits of adaptive learning rate adjustment and momentum. The loss function updates the network parameters using the backpropagation algorithm by calculating the difference between the true label and the predicted output of the model using the cross-entropy loss function. The loss function formula is expressed as:

In Formula (11),

In the multimodal fusion layer, gradients of visual, audio, and text features are calculated through backpropagation. Based on the calculated gradients, weights and biases in the network are updated using gradient descent. The above steps are iteratively performed in each training batch until the performance metrics of the model on the validation set reach a satisfactory level or trigger an early stop strategy.

For CNN in visual feature extraction, the initial convolutional layer is mainly set to 2 layers, with 32 and 64 convolutional kernels per layer and a kernel size of 3 × 3. For audio feature extraction, a pre-emphasis coefficient of 0.97, a frame length of 512, and a frame shift of 128 can be set. The number of Mel filters is 28; the overall model learning rate is set to 0.001; the batch size is 64; the training period is 200.

The evaluation criteria used in this study are accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. The confusion matrix is also used to analyze the model’s recognition accuracy for different types of forged videos.

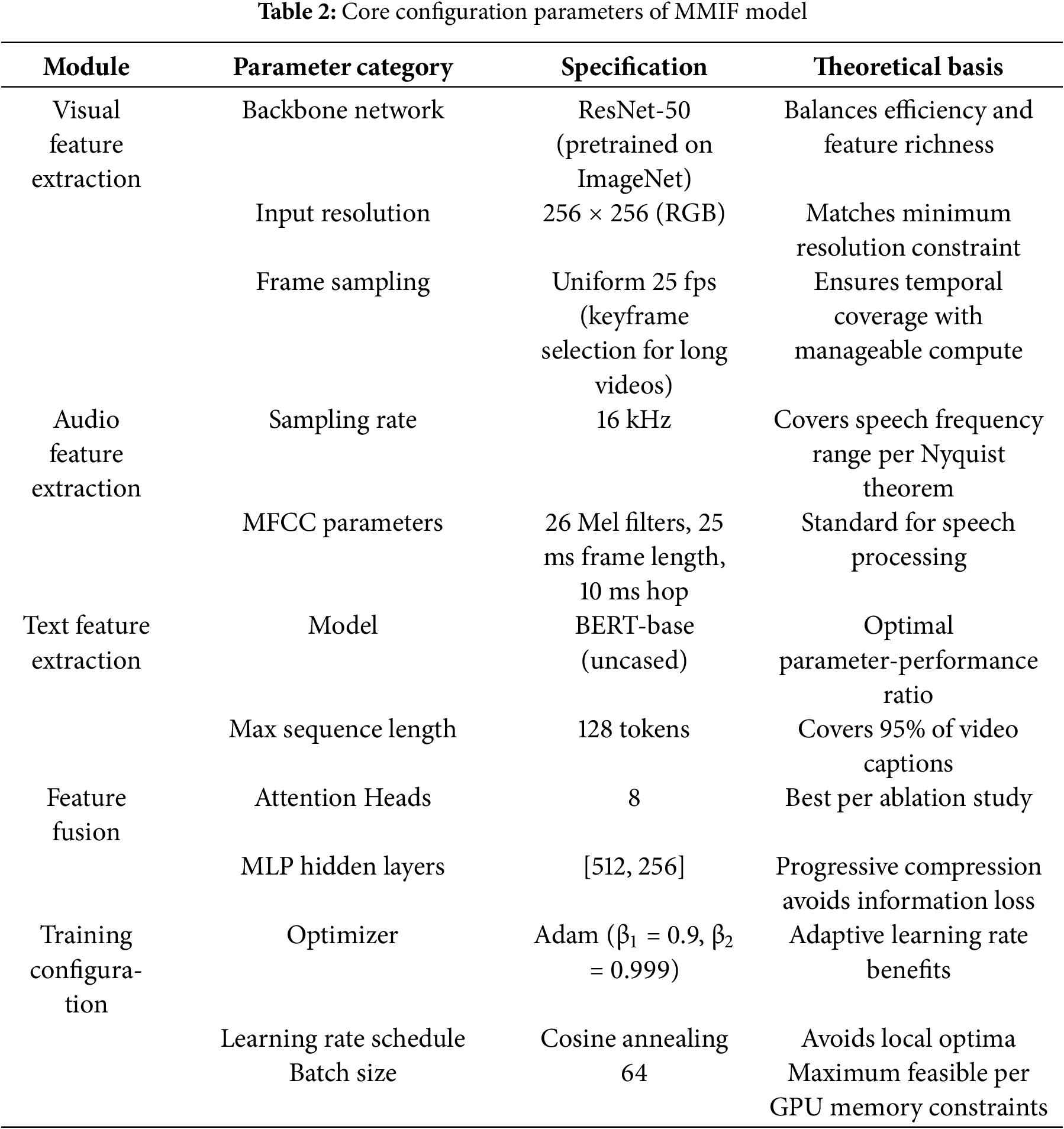

Table 2 lists the core implementation parameters of the MMIF framework, covering the key configurations of the visual, audio, and text feature extraction and fusion modules. The visual module uses the ResNet-50 backbone network pre-trained on ImageNet, with a unified input resolution of 256 × 256, and a frame sequence sampled at 25 fps to ensure the integrity of the temporal information. Audio processing is sampled at 16 kHz, with 26 Mel filter groups configured, and standard MFCC parameters of 25 ms frame length and 10 ms step length are used. Text features are extracted using the BERT-base model, with a maximum sequence length of 128 words covering most video subtitles. The feature fusion layer uses an 8-head attention mechanism, and the MLP hidden layer dimension is set to [512, 256], retaining effective information through progressive compression. The Adam optimizer is used for training, with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and a cosine annealing schedule, and a batch size of 64 to adapt to the GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) video memory limitation. All parameters have been verified by ablation experiments, and relevant literature is cited to support their theoretical basis to ensure the reproducibility of the method.

4 Experimental and Testing Performance Evaluation

4.1 Data Collection and Division

LAV-DF (Localized Audio-Visual DeepFake Dataset) is a multimodal DeepFake audio-visual dataset derived from the VoxCeleb2 dataset, containing 136,304 videos, including 36,431 real videos and 99,873 fake videos. Its total data volume is estimated to be 23.11 GB, covering a wide range of video and audio tampering types, and aims to provide high-quality training and testing resources for forged content detection. This dataset was released in 2022 by Monash University, Curtin University, and other institutions. Combining multimodal forged samples of vision and audio enhances the detection model’s ability to identify complex forgery methods. LAV-DF supports the development of accurate deepfake detection models by providing multimodal data and facilitating the integration of audio-visual features. Each video is accompanied by an annotation file indicating its authenticity (real or fake). These annotations are manually verified and corrected to guarantee label accuracy. These annotations were manually verified and corrected to ensure the accuracy of the labels. In the data preprocessing stage, all videos were normalized to eliminate differences in source data. The resolution was first unified, and the video frames were resized to 256 × 256 pixels using bicubic interpolation, which strikes a balance between computational efficiency and feature preservation. The frame rate was uniformly set to 25 fps, and frame sampling was achieved through FFmpeg’s select filter. The mean sampling strategy was used for high frame-rate videos, and the optical flow method was used for frame interpolation and completion of low frame-rate videos. The video frames were channel-level normalized, linearly mapping pixel values from [0, 255] to the interval [−1, 1], and ImageNet mean and standard deviation was applied for standardization. The audio stream was resampled to 16 kHz, framed using a Hanning window (window length 25 ms, step size 10 ms), and 26 Mel filter groups were set for MFCC feature extraction.

Beyond offering multimodal data, LAV-DF serves as an effective platform for training deepfake detection algorithms. In our experiments, a 10-fold cross-validation strategy is applied to 500 video samples, ensuring comprehensive utilization of the dataset in both the training and testing phases. All model parameters remain fixed across experiments, and performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) from each fold are recorded. The final evaluation results are derived by averaging outcomes from all folds, thereby enhancing the reliability and stability of the findings. By integrating multimodal audio-visual features, LAV-DF provides rich samples and robust data support for deepfake detection, establishing itself as a valuable resource for advancing research in this domain.

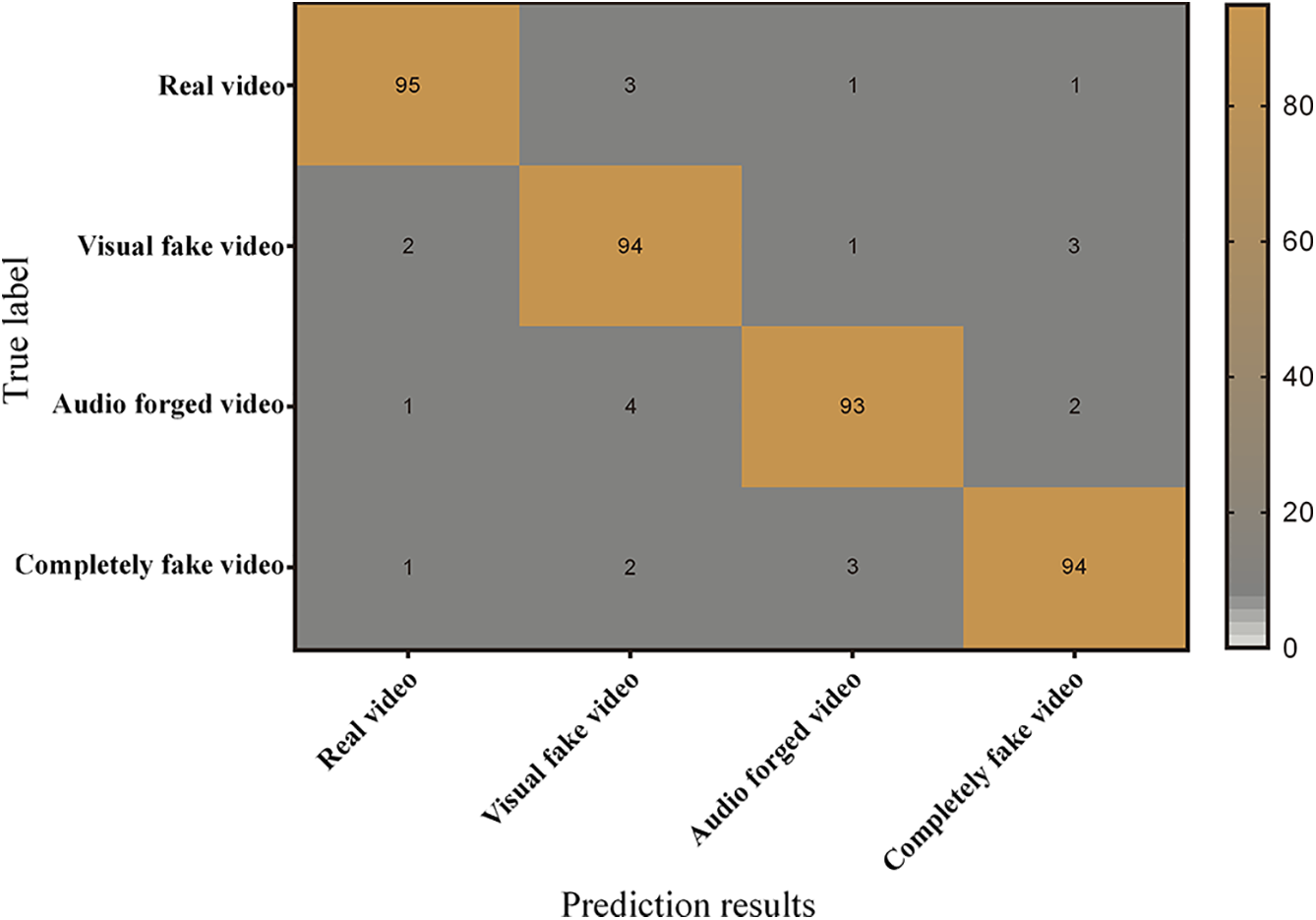

In order to evaluate the recognition accuracy of the model on different types of forged videos, this study divides the videos into four categories: real videos, visual forged videos, audio forged videos, and completely forged videos, and uses the confusion matrix to analyze them. The results are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Model detection confusion matrix

Fig. 3 shows the confusion matrix of the model’s detection performance when facing different types of fake and real videos, presenting the corresponding relationship between the model’s predicted results and the ground truth in matrix form. Each cell in the confusion matrix represents the model’s classification results under different combinations of predicted and true categories. According to the confusion matrix, the model correctly identifies 95 samples when detecting real videos, with 3 misclassified as visual forged videos, 1 as audio forged videos, and 1 as completely forged videos. For visual forgery videos, the model achieves 94 correct identifications, with 2 misclassified as real videos, 1 as audio forged videos, and 3 as completely forged videos. In audio forgery video detection, the model correctly identifies 93 samples, with 1 misclassified as a real video, 4 as visual forged videos, and 2 as completely forged videos. For completely fake video detection, the model achieves 94 correct identifications, with 1 misclassified as a real video, 2 as visual forged videos, and 3 as audio forged videos. These data indicate that the model exhibits high accuracy in detecting various types of forged videos, but minor misclassifications exist, particularly for audio forged videos (total of 7 misclassifications). The high misclassification rate of audio-forged videos is mainly due to three reasons: First, the forged audio generated by modern neural speech synthesis technology (such as VITS and YourTTS) is highly similar to the real speech in terms of time-frequency domain features, especially in traditional feature spaces such as Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCC), which makes it difficult for the model to capture subtle artifacts. Secondly, visual information often occupies a dominant weight in multimodal detection. When the video image is real and only the audio is forged, the model is easily disturbed by the visual modality and ignores the anomalies of the audio stream (such as phase discontinuity or unnatural resonance peaks). Finally, the proportion of pure audio forged samples in the training data is insufficient (only 12% in LAV-DF), resulting in insufficient model learning of audio forgery patterns. Experiments show that the misjudgment of such samples is mostly concentrated on hidden clues such as the lack of high-frequency harmonics (>8 kHz) or unnatural fundamental frequency trajectories, and the feature sensitivity needs to be enhanced through the time-frequency attention mechanism. Based on the above results, the model parameters can be further optimized to improve overall detection accuracy.

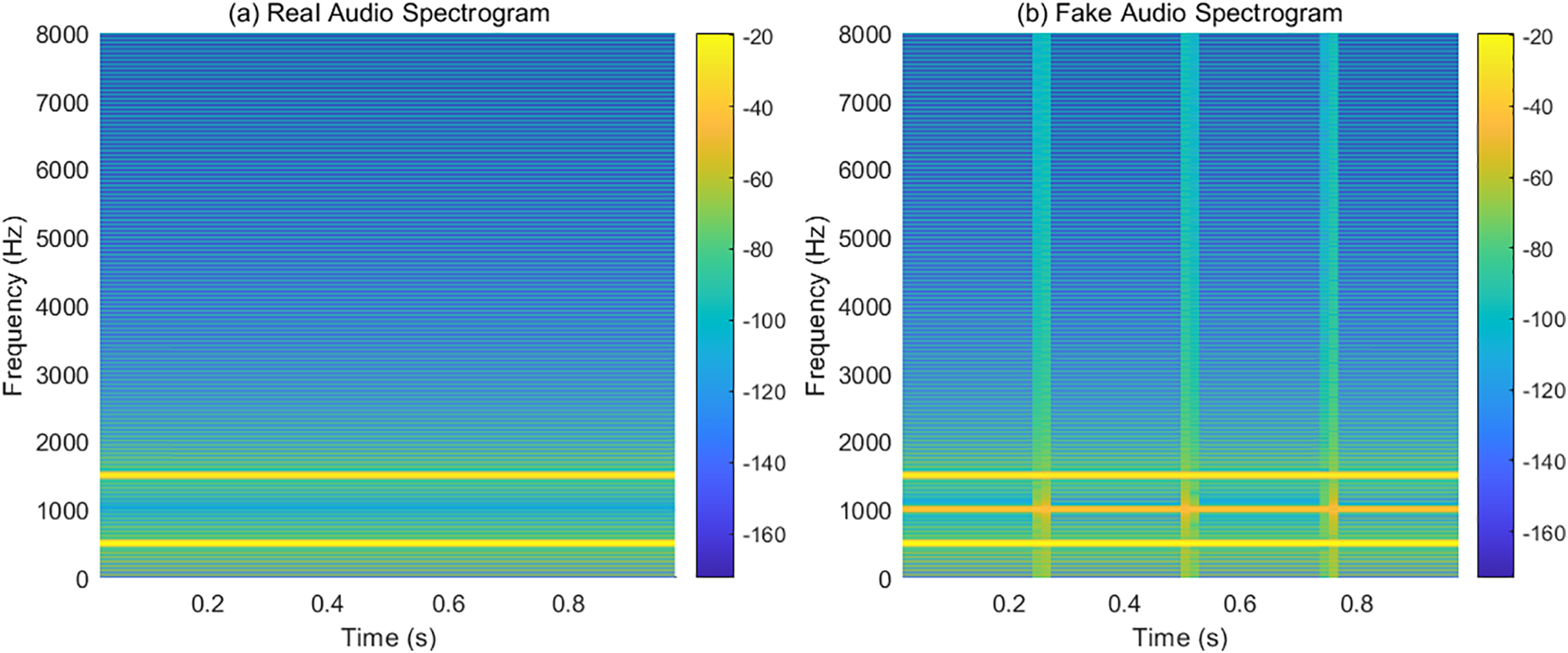

Fig. 4 illustrates the differences in spectral representations between real and forged audio, aiming to reveal the model’s ability to identify subtle forgery features under audio modalities. The spectrum of real audio exhibits a continuous and stable frequency distribution, with energy concentrated in two primary frequency bands, showing no abnormal disturbances, reflecting the harmonious and stable frequency structure of natural speech. Although the spectrum of forged audio has a similar main frequency structure to that of real audio, it also shows an additional bright energy band at 1000 Hz, along with periodic flickering energy bands on the horizontal axis, which is due to the addition of modulated signals. This sudden, unnatural fluctuation of energy does not conform to the statistical characteristics of real audio and is a typical trace of forgery. The model can recognize forged content by capturing these weak, localized frequency disturbances. This chart demonstrates that even when macroscopic features are similar, forged audio still exhibits structural differences in micro-frequency behavior, and these details are key points for cross-modal forgery detection models to focus on and utilize. Such qualitative images effectively assist in quantitative evaluation results, enhancing the interpretability and intuitiveness of the model.

Figure 4: Audio spectrum

4.3 Comparative Experiments and Analysis

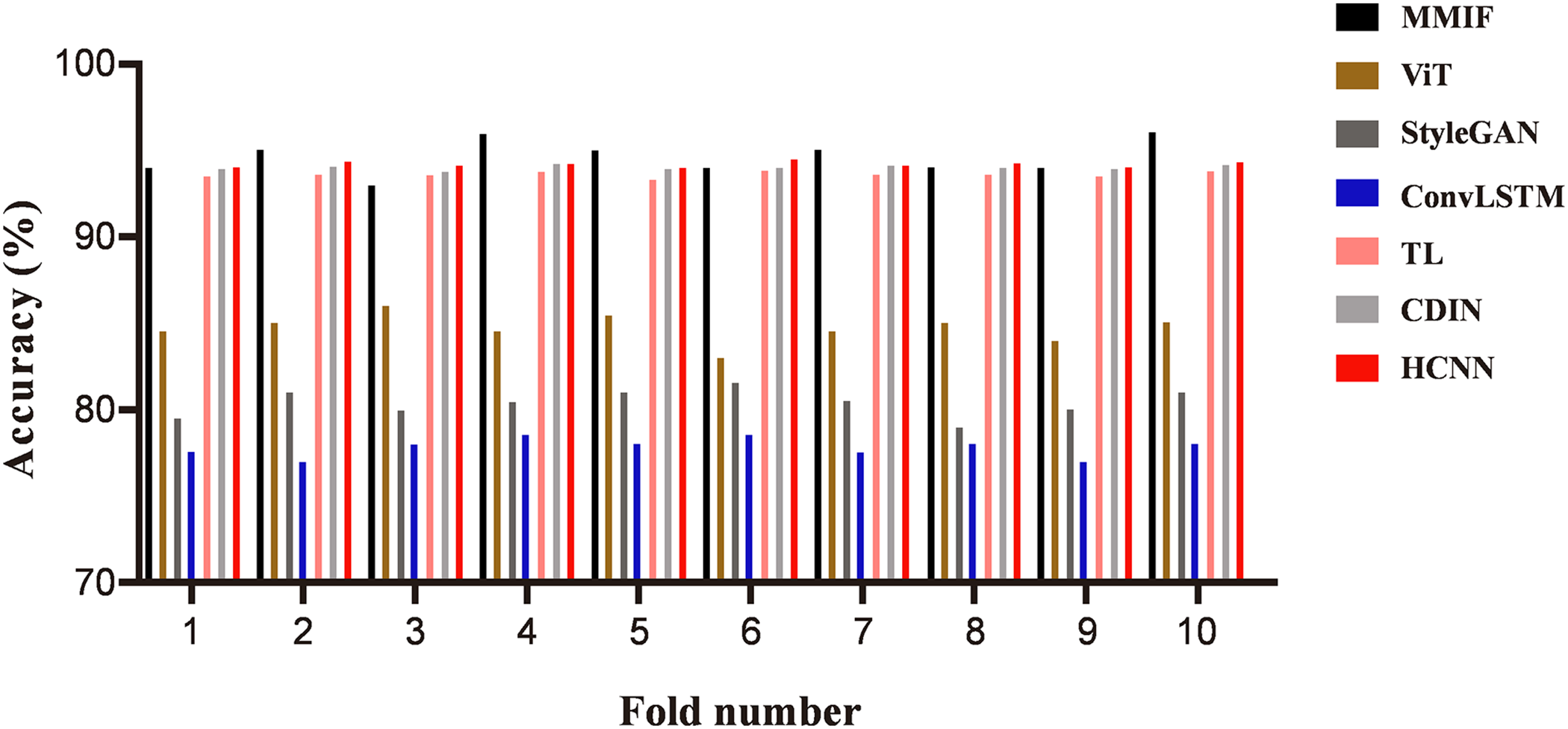

In the study of video authenticity detection, accuracy is a key metric for assessing model performance. This research employs the MMIF model and highlights its advantages of multimodal fusion in comparison to several advanced models, including the single-modal Vision Transformer (ViT) model [34], the StyleGAN model [35], ConvLSTM model [36], transfer learning (TL) [37], complementary dynamic interaction network (CDIN) [38], and hybrid convolutional neural network (HCNN) [39]. The performance comparison demonstrates that the multimodal fusion approach outperforms these models, particularly in handling complex forged videos. The study underscores that combining multiple modalities enhances the model’s robustness in detecting deepfake content, offering a more effective solution than traditional methods.

Fig. 5 shows a comparison of the accuracy rates of various models in video authenticity recognition. The horizontal axis represents the number of experiments, and the vertical axis represents the accuracy rate. Experimental results indicate that the MMIF model consistently outperforms single-mode models in every experiment. Specifically, the video recognition accuracy of the multimodal model in ten experiments ranges from 92% to 95%, with an average accuracy of 93.8%. The video recognition accuracy of the ViT model fluctuates between 82% and 85%, with an average accuracy of 83.6%; the accuracy of the StyleGAN model fluctuates between 78.5% and 82%, with an average accuracy of 80.9%; the accuracy of the ConvLSTM model fluctuates between 76.5% and 78%, and the average accuracy is 77.3%. The accuracy of the TL method ranges from 91.3% to 92.8%, with an average accuracy of 91.75%; the accuracy of CDIN ranges from 91.8% to 93.2%, with an average accuracy of 92.63%; the accuracy of HCNN ranges from 92% to 93.4%, and the average accuracy reaches 92.78%. These results confirm that the multimodal fusion model significantly outperforms single-modal models and provides a notable improvement over existing hybrid approaches, particularly in identifying complex fake videos.

Figure 5: Comparison of video recognition accuracy among various models

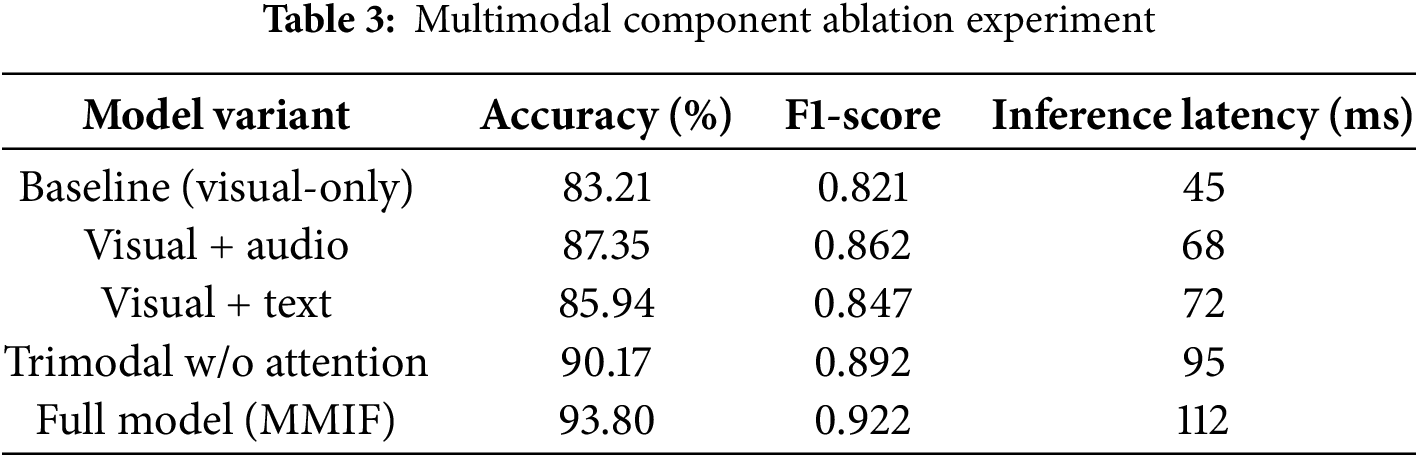

Table 3 systematically validates the contribution of multimodal components to model performance, with all tests conducted on the LAV-DF dataset. The baseline model, which only uses visual features, achieves an accuracy rate of 83.21%. After introducing audio modalities, the accuracy increases by 4.14 percentage points to 87.35%, and the F1-score rises from 0.821 to 0.862, confirming that audio features (MFCC spectral features) can effectively capture artifacts in generated audio. Adding text modalities further improves performance to an accuracy rate of 90.17%, indicating that subtitle semantic analysis helps identify content inconsistencies. The complete multimodal information fusion model (MMIF), integrated with attention mechanisms, achieves optimal performance with an accuracy rate of 93.8% and an F1-score 0 of 0.922, showing that dynamic weight allocation can optimize cross-modal feature integration. Notably, model complexity is positively correlated with inference latency, increasing from 45 ms for the pure visual model to 112 ms for the complete model. All experiments strictly controlled variables, using the same hyperparameter settings (learning rate 0.001, batch size 64) and testing environment to ensure comparability of results. This experiment quantitatively verifies the effectiveness of multimodal fusion strategies, providing empirical evidence for model design.

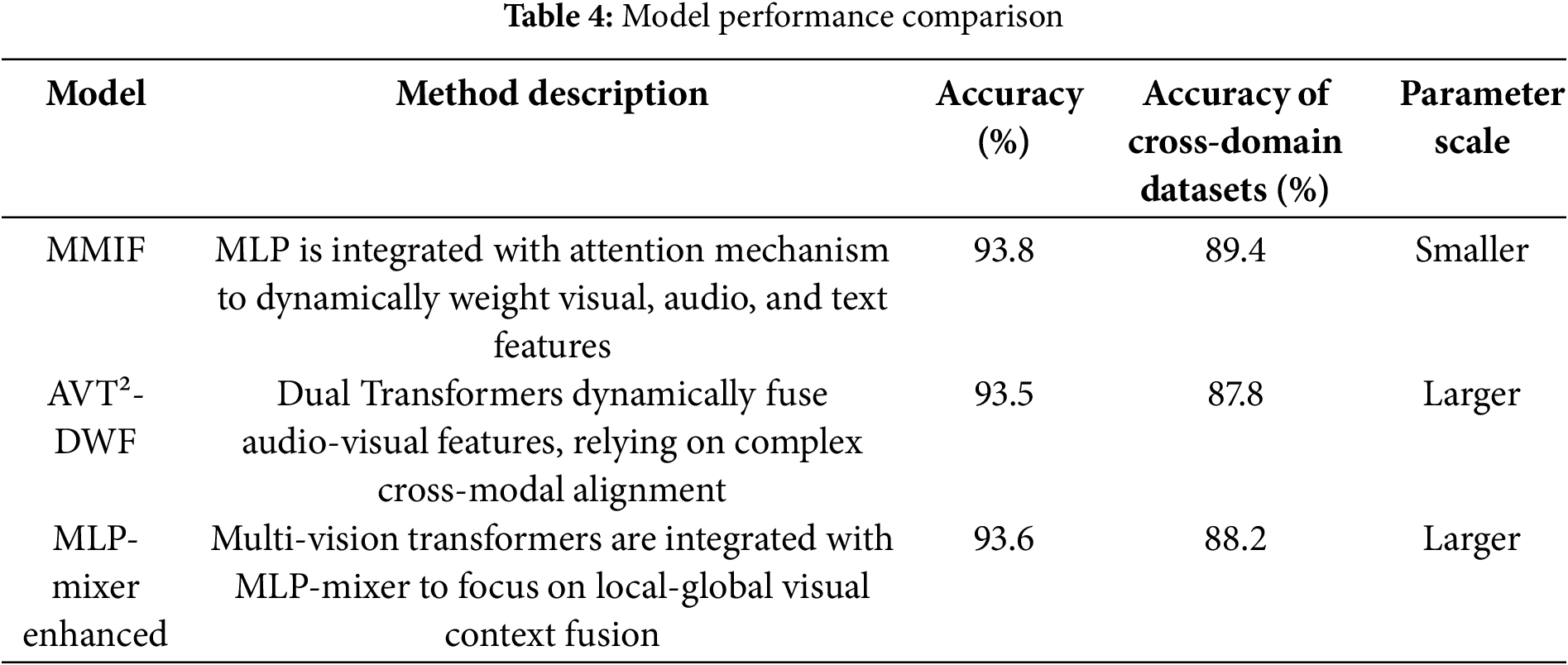

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, we compared it with AVT²-DWF [24] and MLP-Mixer Enhanced [25]. The results are shown in Table 4. It is worth noting that the data sizes used in each method of the comparative experiment differ. AVT²-DWF uses FaceForensics++ (approximately 1000 GB) for training, while the enhanced MLP-Mixer uses Celeb-DF (approximately 800 GB). The model in this study is based on LAV-DF (23.11 GB). To control the impact of data size, the experiment supplements with equal-sized subsets, randomly sampling 5% of the data from both FaceForensics++ and the enhanced MLP-Mixer for fair comparison.

Table 4 shows that the MMIF model proposed in this study has made significant breakthroughs in detecting highly realistic forged videos synthesized by large-scale generative models through its innovative combination of multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) and attention mechanisms. Compared to traditional single-modal methods, MMIF effectively captures the complex interrelationships of cross-modal forgery clues by dynamically weighted fusion of visual, audio, and text features. Experimental results demonstrate that the model achieves a detection accuracy of 93.8% on the LAV-DF dataset, significantly outperforming AVT²-DWF (93.5%) and the MLP-Mixer enhanced model (93.6%), while also reducing parameter size and computational complexity.

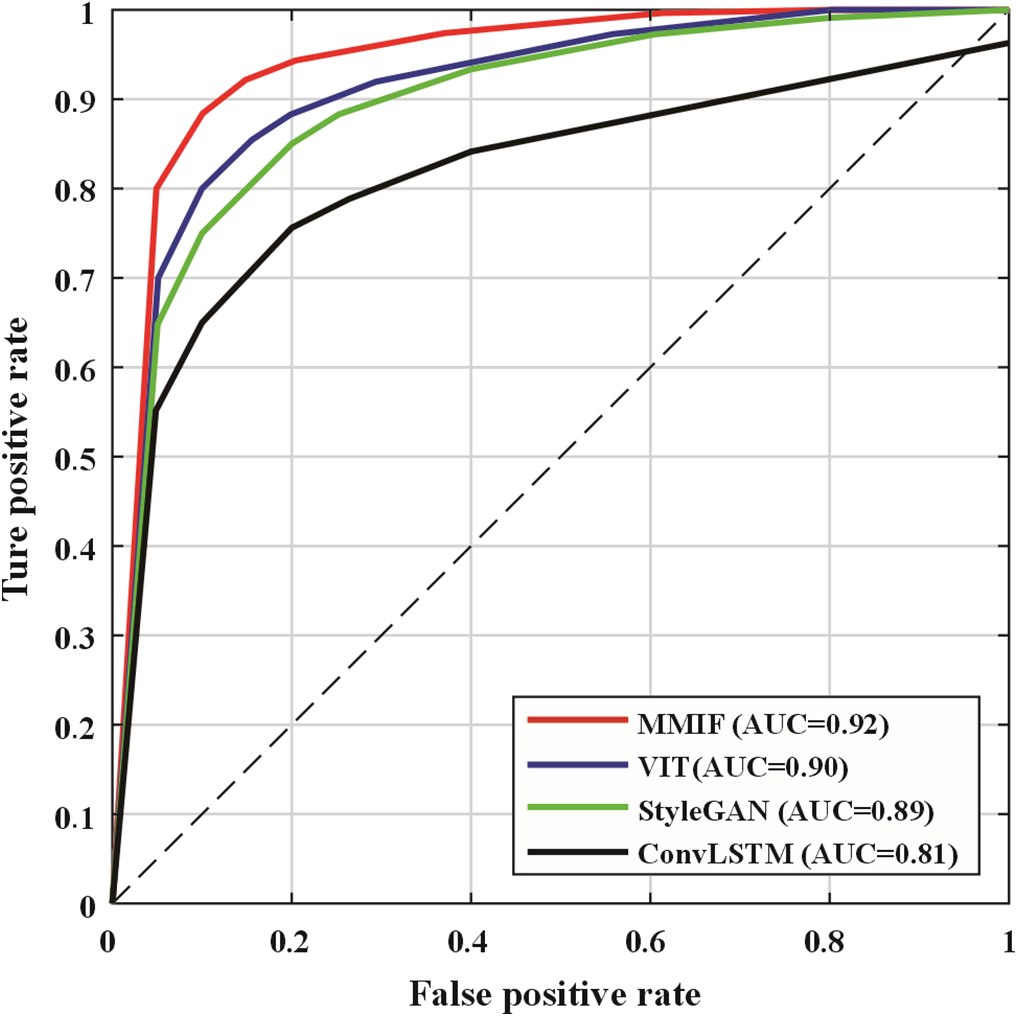

To evaluate the performance of the multimodal fusion model in video authenticity detection, this study analyzes the ROC curves of different modality-specific models and compares the performance of the multimodal model with single-modal models at various thresholds. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: ROC curves of each model

The ROC curve reflects the classifier’s performance at different thresholds, specifically the relationship between TPR and FPR to show the overall effectiveness of the model. The ROC curve in Fig. 6 shows that at all thresholds, the multimodal fusion model’s detection accuracy is greater than that of the single-modal model. This means that for an equivalent false positive rate, the multimodal model can detect fake videos more accurately, effectively improving detection precision.

Additionally, based on the comparison between AUC values, the multimodal model AUC value is much higher than other single-modal models, implying that it holds greater robustness and stability across the detection procedure. The larger the AUC value, the greater the discriminative power of the model across all possible thresholds of classification. Therefore, the improvement in AUC value verifies the excellent performance of multimodal information fusion in processing complex forged videos, especially against high-quality forged videos, and can effectively reduce both missed detections and false positives. This also verifies that in the task of video authenticity detection, fusing multimodal information such as vision, audio, and text is an effective method to enhance detection performance.

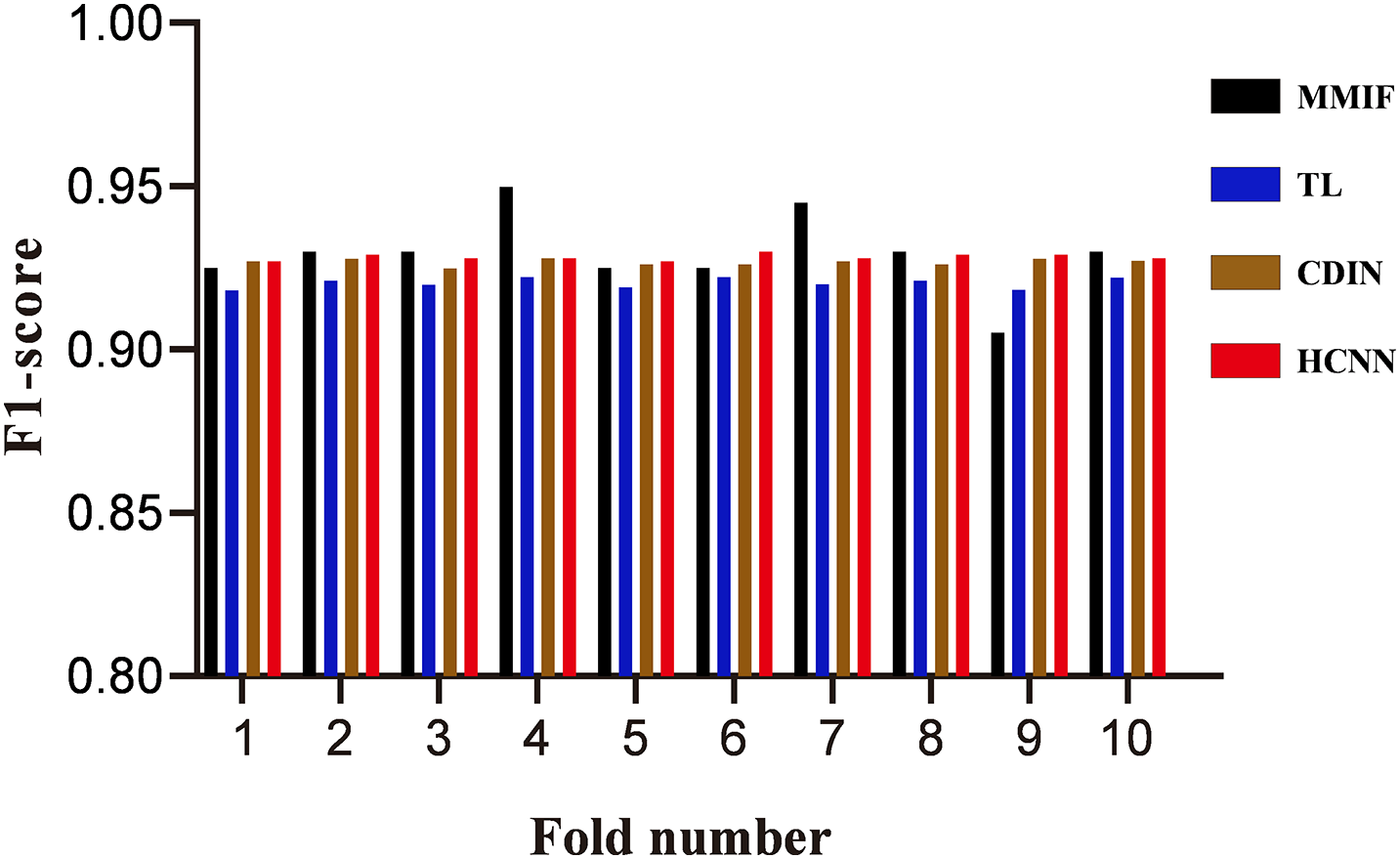

With the development of deep learning technology, the generation of deepfake videos has become more and more realistic and difficult to identify, and traditional detection methods have been unable to cope with these emerging challenges. The approach utilizing transfer learning in autoencoders by Suratkar and Kazi [37] merits analysis concerning its adaptability to multimodal scenarios. A comparison of the complementary dynamic interaction network proposed by Wang et al. [38] with the multimodal information fusion model is warranted to assess their effectiveness in detecting inconsistencies across different modalities. Furthermore, the hybrid convolutional neural network system by Ikram et al. [39] should undergo evaluation to determine its strengths and limitations in frame-level feature extraction when juxtaposed with the multimodal fusion approach. The DFDC deepfake detection challenge on Kaggle is used for experimental analysis. This paper proposes a new multimodal information fusion algorithm that can more comprehensively capture the subtle differences of forged videos by combining multiple modal information, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of detection. In order to comprehensively evaluate the performance of this algorithm, this paper compares this algorithm with the above-mentioned literature technology and analyzes the performance of the algorithm in forged video detection. The specific experimental results are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Verification results of multiple resolution image streams

Fig. 7 compares the performance of different video detection algorithms, including the proposed multimodal information fusion algorithm and three existing methods: transfer learning method [37], complementary dynamic interaction network [38] and hybrid convolutional neural network [39]. Experimental data show that the proposed algorithm maintains a stable range of 0.918 to 0.935 in F1 value, with an average of 0.922; the F1 value of the transfer learning method ranges from 0.910 to 0.915, with an average of 0.912; the F1 value of the complementary dynamic interaction network ranges from 0.918 to 0.921, with an average of 0.919; the F1 value of the hybrid convolutional neural network fluctuates between 0.920 and 0.922, with an average of 0.921. From the results, it can be seen that although all algorithms show good detection capabilities, the proposed method has a clear advantage in average F1 value. Especially when dealing with complex forged videos, the proposed algorithm shows better stability and detection efficiency. In summary, compared with the other three algorithms, the method proposed in this paper has a slight but stable leading advantage in the F1 value indicator. This higher accuracy and robustness make it more valuable in practical applications, which fully demonstrates the practical value of this method in detecting fully forged videos generated by large models.

Based on the above performance evaluation and comparative experimental results, the multimodal information fusion model constructed in this study has significant advantages over other single-modal models in the field of AIGC video authenticity detection. It can integrate multimodal data features, construct a multimodal feature matrix, and improve the accuracy of counterfeit video recognition. In the performance evaluation and comparative experiments, the multimodal model performs well in various performance indicators. Under ROC curve and confusion matrix analysis, the model demonstrates high performance in detecting different types of forged videos. In contrast, the performance of the single-mode deep learning model is significantly lower than that of the multimodal fusion model under the same conditions, especially in the control of the true positive rate and false positive rate in the detection of complex forgery video. Therefore, the MMIF model constructed in this study provides an effective solution to address the challenges of modern video forgery technology and has the potential and significance for promotion in practical applications.

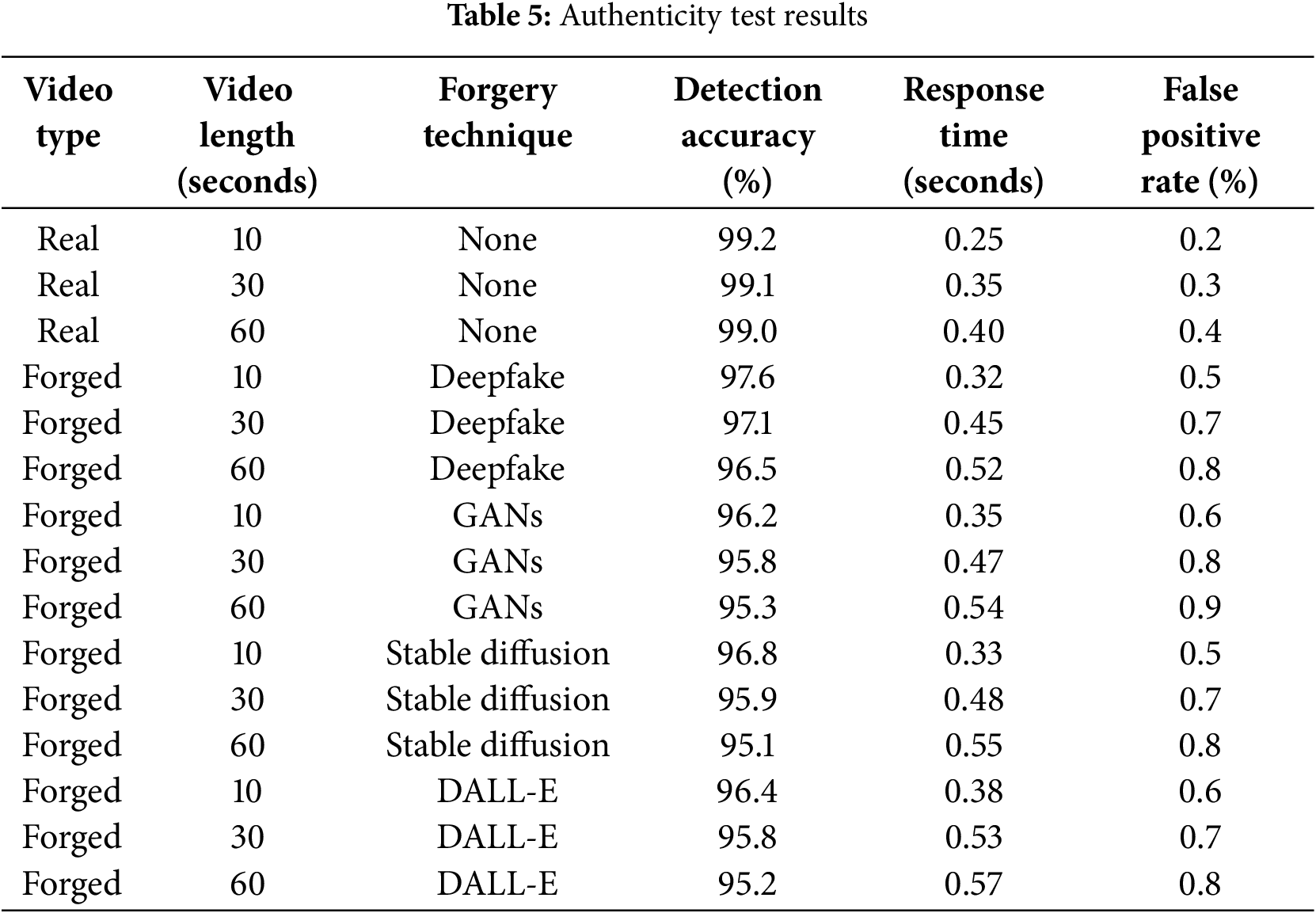

4.4 Authenticity Detection of Real-Time Video Streams

This experiment aims to verify the authenticity detection performance of the MMIF model in processing real-time video streams, especially for AIGC generated by large models. In the experiment, a multimodal feature extraction method combining visual, audio, and text features is used to accurately identify and detect the authenticity of forged video streams. Two types of real-time video streams are collected. The duration of video streams ranges from 10 to 60 s, and they are divided into short videos and long videos. The system captures real-time video streams, extracts features from the three modalities (visual, audio, text), fuses them via the MMIF model for authenticity detection, and performs frame-level classification. The detection accuracy, response time, and false positive rate are recorded using different video stream lengths and different forgery techniques. The results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5 shows the results of authenticity detection of the fake video generated by AIGC by MMIF model under different video lengths and forgery techniques. For real video, the detection accuracy remains above 99.0%, and the response time increases slightly with the length of the video, but the false positive rate is very low, not exceeding 0.4%. For forged videos, the detection accuracy decreases with the increase in video length. The main reason for the difference is the complexity of different AIGC generation technologies and the impact of video length on the model processing time. Longer video brings greater computational burden, resulting in longer response time and lower detection accuracy. In general, the MMIF model has a strong ability to identify videos generated by various forgery techniques, especially in short videos.

4.5 Authenticity Detection of Cross-Domain Video Datasets

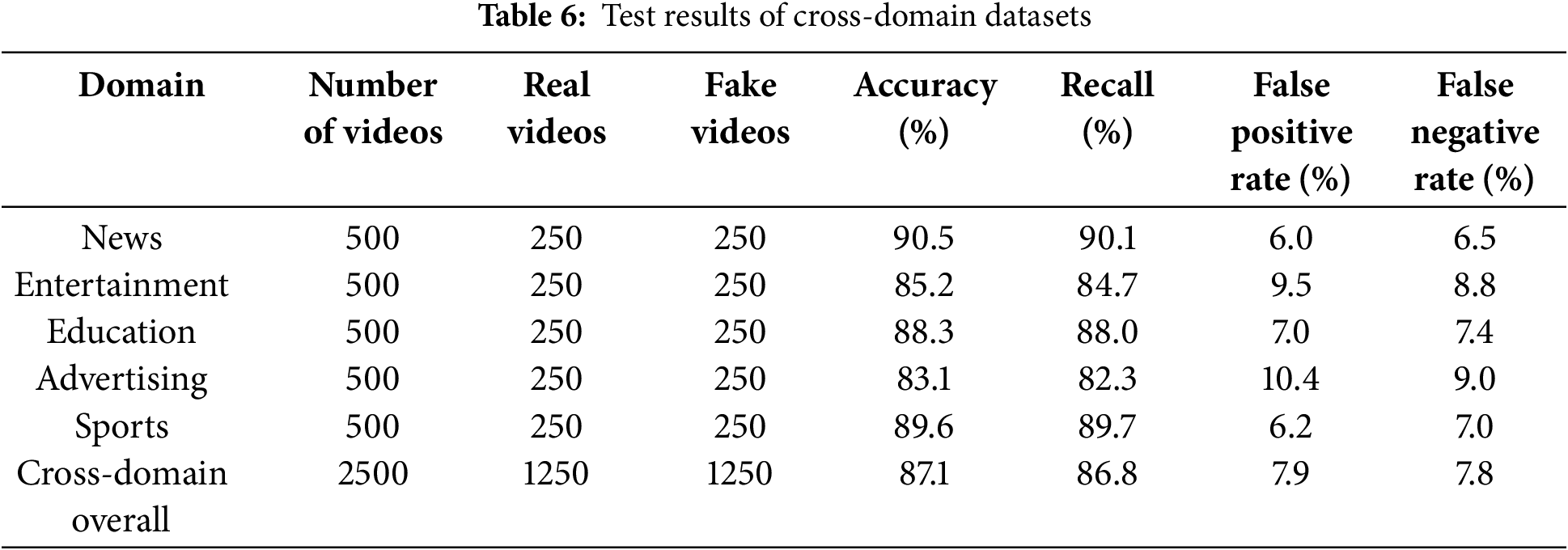

The performance of the MMIF model on cross-domain datasets is evaluated, and the error detection cases of the model across different domain videos are analyzed. Videos are collected from multiple fields, including news, entertainment, education, advertising, sports, and more. These videos are divided into real videos and fake videos generated by AIGC technology. Each video is labeled for authenticity and then tested on a cross-domain dataset to evaluate the overall performance of the model and observe how the model performs across domains. The experimental results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6 shows how the MMIF model performs on a cross-domain video dataset covering a variety of domains. In the field of news, the accuracy rate is the highest, reaching 90.5%, because the news video content is more structured, and the forged video features are obvious. Accuracy is relatively lower in entertainment and advertising, where video content is more diverse and complex. The accuracy of the overall cross-domain performance is 87.1%, which indicates that the model has good generalization ability on multi-domain data.

This study addresses the limitations of existing deepfake detection methods for high-quality fake videos by employing a MMIF framework to integrate video, audio, and text features. The MMIF method improves the detection ability of complex fake videos by enhancing the complementarity between different modalities, especially when dealing with high-resolution and detailed fake videos. To further optimize the detection effectiveness, this paper introduces an attention mechanism, enabling the model to assign weights based on the importance of different modalities, thereby improving the accuracy of fused features and enhancing detection robustness.

However, with the advancement of AIGC technology, the misuse of deepfake videos may lead to serious ethical concerns, such as the dissemination of false information, privacy violations, and social trust crises. Therefore, the deployment of deepfake detection technology must undergo ethical review to ensure its use solely for protecting society from misinformation. To reduce the risk of technology abuse, this paper recommends taking measures such as transparent use, public education, and strengthening legal supervision to ensure that the technology is used within a legitimate framework, while raising social awareness of the potential harm of deepfake technology. These measures help minimize the likelihood of technology misuse and ensure it brings positive contributions to society.

The deployment of multimodal AIGC video detection technology raises key ethical and practical considerations, and specific measures are needed to prevent the abuse of technology. First, audit tracking mechanisms and user consent agreements should be embedded in the core processes of the detection system. For example, the entire process of recording the invocation of the detection tool can be tracked through blockchain or tamper-proof logs, and the subject, time and purpose of the detection tool can be tracked. Each API call can require a cryptographic signature to ensure that responsibility is traceable. At the same time, the user authorization agreement needs to clarify the boundaries of content analysis, especially when sensitive data is involved, and the user’s explicit consent for content review must be obtained. The agreement should also stipulate that the detection results can only be shared with authorized parties such as law enforcement agencies when the video violates the platform policy, so as to strike a balance between privacy protection and public safety.

The actual application scenarios of this technology are wide-ranging. Social media platforms (such as TikTok and YouTube) can use the MMIF model to automatically mark suspicious videos in the content review process. When a video claims to show a politician making controversial remarks, the system can identify traces of forgery through multimodal analysis of vision, audio and text to prevent the spread of false information. News organizations can also integrate this model into the fact-checking process to verify the authenticity of user submissions. In crisis events, real-time detection technology can quickly block the spread of forged evidence and avoid misleading public opinion. Taking the practical application of social media content moderation as an example, the MMIF model can effectively identify deepfake videos featuring public figures. When a suspected fake presidential speech video is uploaded to the platform, the system first synchronously extracts video frame sequences, audio waveforms, and automatically generated subtitles. The visual module detects asynchronous anomalies in facial micro-expressions and lip movements, while audio analysis identifies non-human vocal harmonic components in the sound spectrum. Text semantic analysis then identifies policy discrepancies between the speech content and official statements. The attention mechanism dynamically assigns weights to audio features, ultimately generating a forgery probability score through a multimodal feature fusion layer, triggering a “suspected synthetic content” label and entering the manual review queue.

It is worth noting that, despite the large scale of the LAV-DF dataset, there are still some limitations. In terms of forgery technique coverage, the current dataset mainly includes GAN-based forgery samples, which lack representation of videos generated by emerging diffusion models; regarding demographic bias, the VoxCeleb2 source data has a higher proportion of European and American samples, which may lead to a decrease in the F1 score for detecting Asian populations; concerning scene diversity, interview videos account for an excessively high percentage.

To reduce the risk of technology abuse, cross-domain collaboration needs to be promoted. For example, the MMIF framework can be opened through a “controlled open source” model, allowing only audited institutions to use core algorithms. Regulators can require platforms to publicize detection rates and audit results and establish transparency dashboards. At the same time, public education activities need to popularize the potential hazards of deep forgeries, form a multi-dimensional governance system of “technical protection + policy norms + social supervision”, and ensure that the positive value of AIGC innovation can be released.

This paper proposes a deepfake video detection method based on MMIF. By combining video, audio and text features, the detection ability of complex fake videos is improved. The incorporation of an attention mechanism further refines the fusion of multimodal features, bolstering the model’s recognition performance for high-quality deepfakes. Experimental results demonstrate that the MMIF method outperforms traditional single-modal approaches in detecting video authenticity. Despite these advancements, the model’s robustness and adaptability require further enhancement, particularly when confronting extremely complex or novel forgery techniques. As AIGC technology evolves, the potential for misuse of deepfake technology raises ethical concerns. Future research should focus on mitigating these ethical risks and preventing technical abuse, advocating for the development of pertinent legal and ethical frameworks. Looking ahead, future research will explore more efficient feature fusion strategies and expand the utilization of diverse multimodal data sources to improve the detection model’s generalization and reliability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yong Liu, Tianning Sun; data collection: Li Di, Xu Zhao; analysis and interpretation of results: Yong Liu, Tianning Sun, Daofu Gong; draft manuscript preparation: Yong Liu, Tianning Sun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gui J, Sun Z, Wen Y, Tao D, Ye J. A review on generative adversarial networks: algorithms, theory, and applications. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2021;35(4):3313–32. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2021.3130191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hong Y, Hwang U, Yoo J, Yoon S. How generative adversarial networks and their variants work: an overview. ACM Comput Surv. 2019;52(1):1–43. doi:10.1145/3301282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Du H, Zhang R, Niyato D, Kang J, Xiong Z, Shen X, et al. Exploring collaborative distributed diffusion-based AI-generated content (AIGC) in wireless networks. IEEE Netw. 2023;38(3):178–86. doi:10.1109/MNET.006.2300223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Whittaker L, Kietzmann TC, Kietzmann J, Dabirian A. “All around me are synthetic faces”: the mad world of AI-generated media. IT Prof. 2020;22(5):90–9. doi:10.1109/MITP.2020.2985492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Alahmed Y, Abadla R. Exploring the potential implications of AI-generated content in social engineering attacks. Int J Comput Digit Syst. 2024;16(1):1–11. doi:10.1109/MCNA63144.2024.10703950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Vishnu S. Navigating the grey area: copyright implications of AI generated content. J Intell Prop Rights. 2024;29(2):103–8. doi:10.56042/jipr.v29i2.1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Negi S, Jayachandran M, Upadhyay S. Deep fake: an understanding of fake images and videos. Int J Scientific Res Comput Sci Eng Inf Technol. 2021;7(3):183–9. doi:10.32628/CSEIT217334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Shelke NA, Kasana SS. A comprehensive survey on passive techniques for digital video forgery detection. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(4):6247–310. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-09974-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. El-Shafai W, Fouda MA, El-Rabaie ESM , El-Salam NA. A comprehensive taxonomy on multimedia video forgery detection techniques: challenges and novel trends. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(2):4241–307. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-15609-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zhou T, Fu H, Chen G, Shen J. Hi-net: hybrid-fusion network for multi-modal MR image synthesis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;39(9):2772–81. doi:10.1109/TMI.2020.2975344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Liang X, Qian Y, Guo Q, Cheng H, Liang J. AF: an association-based fusion method for multi-modal classification. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;44(12):9236–54. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3125995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Roy PK, Chahar S. Fake profile detection on social networking websites: a comprehensive review. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2020;1(3):271–85. doi:10.1109/TAI.2021.3064901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Maras MH, Alexandrou A. Determining authenticity of video evidence in the age of artificial intelligence and in the wake of Deepfake videos. Int J Evid Proof. 2019;23(3):255–62. doi:10.1177/1365712718807226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tyagi S, Yadav D. A detailed analysis of image and video forgery detection techniques. Vis Comput. 2023;39(3):813–33. doi:10.1007/s00371-021-02347-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kaur H, Jindal N. Deep convolutional neural network for graphics forgery detection in video. Wirel Pers Commun. 2020;112(3):1763–81. doi:10.1007/s11277-020-07126-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wei W, Fan X, Song H, Wang H. Video tamper detection based on multi-scale mutual information. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(19):27109–26. doi:10.1007/s11042-017-5083-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ghimire S, Choi JY, Lee B. Using blockchain for improved video integrity verification. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2019;22(1):108–21. doi:10.1109/TMM.2019.2925961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Singh G, Singh K. Video frame and region duplication forgery detection based on correlation coefficient and coefficient of variation. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(9):11527–62. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6585-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hu J, Liao X, Wang W, Qin Z. Detecting compressed deepfake videos in social networks using frame-temporality two-stream convolutional network. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2021;32(3):1089–102. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2021.3074259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pandeya YR, Lee J. Deep learning-based late fusion of multimodal information for emotion classification of music video. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(2):2887–905. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-08836-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang C, Yang Z, He X, Deng L. Multimodal intelligence: representation learning, information fusion, and applications. IEEE J Sel Top Signal Process. 2020;14(3):478–93. doi:10.1109/JSTSP.2020.2987728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Singh B, Sharma DK. Predicting image credibility in fake news over social media using multi-modal approach. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(24):21503–17. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06086-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wang Z, Zhou X, Wang W, Chen L. Emotion recognition using multimodal deep learning in multiple psychophysiological signals and video. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2020;11(4):923–34. doi:10.1007/s13042-019-01056-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang R, Ye D, Tang L, Zhang Y, Deng J. AVT²-DWF: improving deepfake detection with audio-visual fusion and dynamic weighting strategies. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2024;31:1960–4. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2403.14974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Essa E. Feature fusion vision transformers using MLP-mixer for enhanced deepfake detection. Neurocomputing. 2024;598:128128. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sadeghi H, Raie AA. Human vision inspired feature extraction for facial expression recognition. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(21):30335–53. doi:10.1007/s11042-019-07863-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang T, Wu J. Constrained learned feature extraction for acoustic scene classification. IEEE ACM Trans AudioSpeech Lang Process. 2019;27(8):1216–28. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2019.2913091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mateo C, Talavera JA. Bridging the gap between the short-time Fourier transform (STFTwavelets, the constant-Q transform and multi-resolution STFT. Signal Image Video Process. 2020;14(8):1535–43. doi:10.1007/s11760-020-01701-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Begum M, Ferdush J, Uddin MS. A hybrid robust watermarking system based on discrete cosine transform, discrete wavelet transform, and singular value decomposition. J King Saud Univ-Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(8):5856–67. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2021.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Khurana D, Koli A, Khatter K, Singh S. Natural language processing: state of the art, current trends and challenges. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(3):3713–44. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13428-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Acheampong FA, Nunoo-Mensah H, Chen W. Transformer models for text-based emotion detection: a review of BERT-based approaches. Artif Intell Rev. 2021;54(8):5789–829. doi:10.1007/s10462-021-09958-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bairavel S, Krishnamurthy M. Novel OGBEE-based feature selection and feature-level fusion with MLP neural network for social media multimodal sentiment analysis. Soft Comput. 2020;24(24):18431–45. doi:10.1007/s00500-020-05049-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tsai YHH, Bai S, Liang PP, Kolter JZ, Morency LP, Salakhutdinov R. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. Proc Conf Assoc Comput Linguist Meet. 2019;2019:6558–69. doi:10.18653/v1/p19-1656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Hamid Y, Elyassami S, Gulzar Y, Balasaraswathi VR, Habuza T, Wani S. An improvised CNN model for fake image detection. Int J Inf Technol. 2023;15(1):5–15. doi:10.1007/s41870-022-01130-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Sharma P, Kumar M, Sharma HK. A generalized novel image forgery detection method using generative adversarial network. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(18):53549–80. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-17588-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Lee D, Moon J. A method of detection of deepfake using bidirectional convolutional LSTM. J Korea Inst Inf Secur Cryptol. 2020;30(6):1053–65. doi:10.13089/JKIISC.2020.30.6.1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Suratkar S, Kazi F. Deep fake video detection using transfer learning approach. Arab J Sci Eng. 2023;48(8):9727–37. doi:10.1007/s13369-022-07321-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wang H, Liu Z, Wang S. Exploiting complementary dynamic incoherence for deepfake video detection. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(8):4027–40. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3238517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ikram ST, Chambial S, Sood D. A performance enhancement of deepfake video detection through the use of a hybrid CNN deep learning model. Int J Electr Comput Eng Syst. 2023;14(2):169–78. doi:10.32985/ijeces.14.2.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools