Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Ransomware Detection with Machine Learning Techniques and Effective API Integration

1 School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

2 Department of Software Convergence, Gyeongbuk National University (Andong National University), Gyeongbuk, 36729, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Mehdi Hussain. Email: ; Ki-Hyun Jung. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Safe and Secure Artificial Intelligence)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1693-1714. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.064260

Received 10 February 2025; Accepted 11 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Ransomware, particularly crypto-ransomware, remains a significant cybersecurity challenge, encrypting victim data and demanding a ransom, often leaving the data irretrievable even if payment is made. This study proposes an early detection approach to mitigate such threats by identifying ransomware activity before the encryption process begins. The approach employs a two-tiered approach: a signature-based method using hashing techniques to match known threats and a dynamic behavior-based analysis leveraging Cuckoo Sandbox and machine learning algorithms. A critical feature is the integration of the most effective Application Programming Interface call monitoring, which analyzes system-level interactions such as file encryption, key generation, and registry modifications. This enables the detection of both known and zero-day ransomware variants, overcoming limitations of traditional methods. The proposed technique was evaluated using classifiers such as Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and K-Nearest Neighbors, achieving a detection accuracy of 98% based on 26 key ransomware attributes with an 80:20 training-to-testing ratio and 10-fold cross-validation. By combining minimal feature sets with robust behavioral analysis, the proposed method outperforms existing solutions and addresses current challenges in ransomware detection, thereby enhancing cybersecurity resilience.Keywords

Ransomware encrypts digital data and alters system login credentials to restrict access to victims’ resources. The attacker claims a ransom from the target for acquiring access to its resources. In 2017, the WannaCry cyberattack infected over 200,000 systems across 150 countries [1]. Ransomware is a prominent threat in the malware landscape, consistently ranked as one of the top concerns for cybersecurity experts. While infection rates have declined, ransomware remains highly cost-effective, as attackers focus on targeted internal communications and demand larger payouts. This profitability continues to attract cybercriminals, solidifying ransomware’s position as a major cybersecurity challenge.

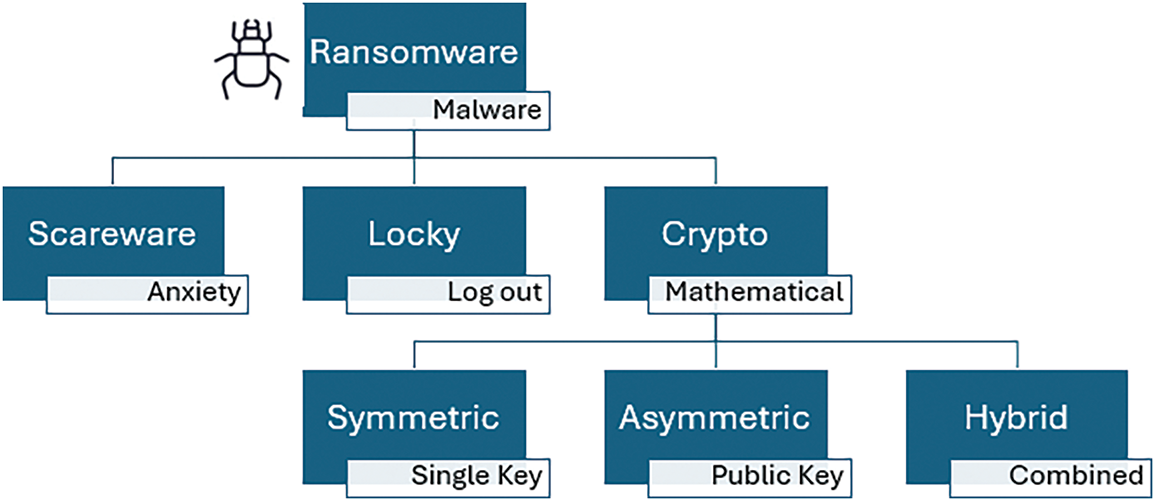

The proliferation of ransomware consists of multiple factors, including the widespread Internet usage enabling cross-border cyberattacks and the anonymity of cryptocurrencies facilitating untraceable ransom payments. Moreover, the cost-effectiveness of digital storage creates vulnerabilities that ransomware exploits, particularly through encryption. The availability of ransomware kits on the Dark Web and the rise of ransomware-as-a-service schemes makes it increasingly accessible, ensuring its sustained growth as a cyber threat. The types of ransomwares can be shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Types of ransomwares

Attack Vector

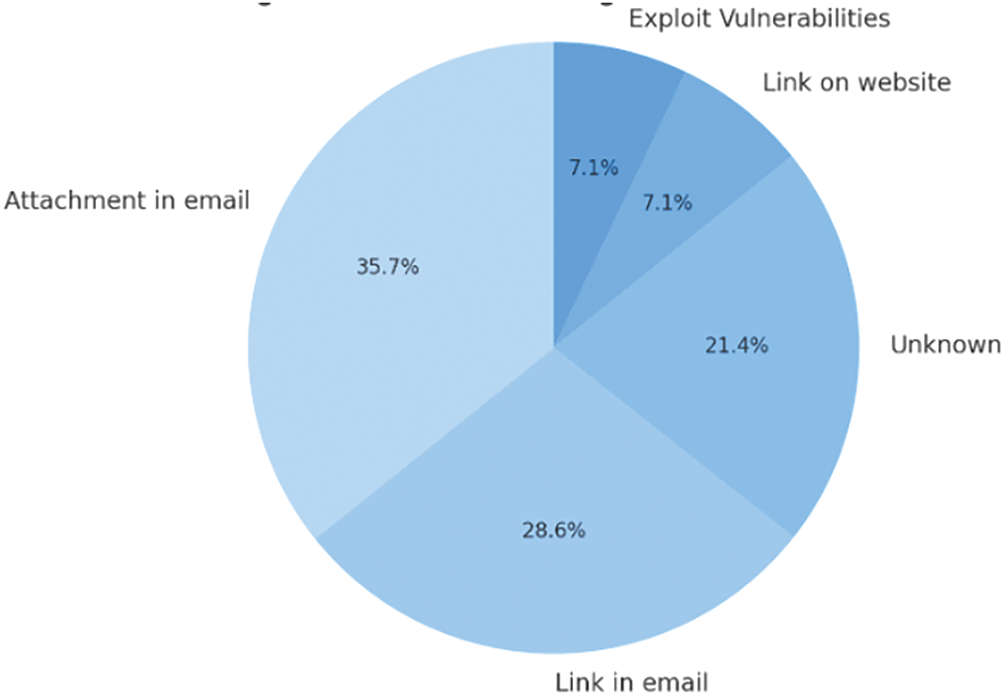

Ransomware is often propagated through phishing emails, in which cybercriminals distribute malicious attachments or embed links that direct victims to counterfeit documents or seemingly legitimate websites. When a victim clicks on these attachments, the ransomware activates on their device and begins spreading across the system. Advanced ransomware variants further execute reconnaissance on the infected device, gathering system information before establishing communication with their Command and Control (C & C) server. Through this connection, the ransomware transmits the collected data and requests cryptographic keys. Using these keys, it encrypts critical files, such as Microsoft Office documents, images, media files, and metadata. The ransomware only reveals its presence after encrypting all essential data, leaving the victim locked out of their files [2]. Almost 63.3% of ransomware infections are attributable to emails, with 35.7% relating to opening an attachment and 28.6% to clicking on a link, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Moreover, 21.4% of victims report being unaware of how they became infected with ransomware. Additionally, ransomware typically provides its victims with a limited timeframe to pay the ransom before the amount increases.

Figure 2: Ransomware attack vectors [2]

Another significant vector for ransomware attacks involves victims visiting malicious or compromised websites, either intentionally or inadvertently. This type of attack, known as malvertising, leverages redirection strategies to exploit vulnerabilities in unsuspecting users. In a typical malvertising scenario, attackers embed exploit kits within an inline frame, or iframe, on a legitimate website. When users access the compromised site, they are redirected from the secure page to a malicious one, triggering the download and execution of ransomware. This sophisticated tactic highlights the increasing risks associated with online advertising and website vulnerabilities [3]. Windows OS is the most widely used operating system, making it a primary target for ransomware attacks. A critical aspect of ransomware detection within Windows lies in its Application Programming Interface (API). APIs serve as the primary interaction point with the operating system, and all programs rely on these interfaces for execution. Consequently, analyzing API behavior is a highly effective approach for identifying ransomware [4].

This study focuses on crypto ransomware, a particularly destructive variant that encrypts victims’ data and files using robust techniques such as hybrid encryption. The damage caused by crypto ransomware is often severe and irreversible, especially if recovery mechanisms are unavailable post-encryption. The pre-encryption phase is therefore crucial for detection and intervention, as early identification can significantly reduce the impact of an attack. Developing an early detection model is vital for mitigating these threats and safeguarding user data.

Existing research has introduced numerous models for ransomware detection, leveraging classical and advanced machine learning techniques. Advanced ML techniques, such as deep learning and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), require extensive data for effective training/classification, where classical machine learning algorithms can deliver reliable performance with fewer samples, making them an ideal choice. However, most of the classical ML-based ransomware detection models also rely on an extensive number of features, complex architectures, and are based on a single detection approach, which may lead them to be less effective against sophisticated ransomware variants.

Therefore, the proposed model addresses these limitations by employing a smaller, optimized set of features (API calls) and integrating both signature-based and behavior-based crypto ransomware detection mechanisms through classical machine learning. Furthermore, we optimized the detection process by reducing the required number of features, improving the model’s efficiency compared to existing machine learning-based approaches. This approach serves as proof of concept for a lightweight and effective ransomware detection system. In short, the proposed approach enhances robustness and adaptability, offering a significant contribution to the advancement of ransomware detection methodologies. The core contribution of the study is as follows:

• Behavioral Analysis: Identified key ransomware behaviors through API analysis and optimized features for efficient detection.

• Pre-Encryption Detection: Developed a model to detect ransomware before encryption, minimizing damage.

• Dataset Enhancement: Enriched ransomware datasets using real-time analysis of ransomware features by employing machine learning.

This paper conducts a comprehensive review of existing studies and presents a detailed discussion on the design, implementation, and analysis of the experimental framework. The findings derived from the experiments are thoroughly analyzed, leading to significant conclusions that contribute to the field. Additionally, the paper offers valuable recommendations to guide future research and advance the understanding of the subject.

Numerous studies and technical reports have highlighted the escalating threat of malware and its substantial impact on organizational security. The proliferation of advanced technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and cloud computing, which enhance global connectivity, has been accompanied by a corresponding rise in malware attacks [5]. This increase presents significant risks, especially when end-users lack awareness of the threats associated with these emerging technologies [6]. Among malware families, ransomware stands out as the most prevalent, targeting organizations and individual users on a large scale. Ransomware’s effectiveness stems from its direct interaction between attackers and victims, where attackers demand ransoms in exchange for decryption keys. Alarmingly, data shows that 37% of affected organizations fail to recover their data even after paying the ransom [7]. Once ransomware infiltrates a system, it encrypts files using advanced encryption algorithms, withholding the decryption key and rendering data inaccessible [8]. While encryption is fundamentally used to ensure data confidentiality, attackers maliciously exploit this technology by deploying crypto-ransomware to deny users access to their own data. In particular, the work in [9] highlights the challenges and vulnerabilities associated with encryption schemes when faced with such attacks, discussing how encryption, although essential for security, can be turned against users when misused by malicious actors. The study also outlines the limitations of current encryption techniques in big data environments, where the massive scale and distributed nature of data increase the impact of ransomware and emphasize the need for robust, attack-resistant public key encryption schemes.

Current anti-malware solutions, such as antivirus software and intrusion detection systems (IDS), which rely on signature-based detection methods, are ineffective against zero-day attacks. This limitation arises because new malware signatures are not immediately added to the signature databases, leaving systems vulnerable to emerging threats [10]. Ransomware remains a favored tool for cybercriminals, with new variants continually developed to evade antivirus programs [11]. Moreover, the emergence of Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) has lowered the technical barrier, enabling non-technical individuals with malicious intent to deploy ransomware attacks [12]. To address this growing threat, strong protection is urgently needed for organizations and users. Significant research efforts are focused on detecting ransomware at an early stage, employing techniques such as static and dynamic analysis to improve detection accuracy and mitigate damage [13].

Static analysis involves examining the source code without executing the ransomware, making it a safer approach for initial evaluation. One common technique involves extracting opcodes from the source code and generating n-gram representations, which are then used to train machine learning models for ransomware prediction [14]. Similarly, researchers have proposed rule-based detection methods derived from source code analysis [15]. In addition, analyzing the headers of executable files has also proven effective for ransomware detection. Malware apps targeting mobile devices exploit Android’s open-source nature, unofficial app stores, and lack of verification processes. PerDRaML [16] is a permissions-based malware detection system that uses features such as permissions and smali sizes from a dataset of 10,000 apps. Machine learning models demonstrated high detection accuracy, with Random Forest achieving 89.96%. The approach optimized approximately 77% of the feature set, enhancing precision, sensitivity, and F-measure compared to existing techniques. Another study [17] evaluates four classifiers using a real-device hybrid analysis dataset (2008–2020). Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy (97.86%) and demonstrated sustainability, while Logistic Regression was the most efficient, with GPU-based setups significantly reducing training time. The results demonstrate notable improvements in detection accuracy, efficiency, and long-term performance. However, a major limitation of static analysis lies in its susceptibility to obfuscation techniques, which can mask malicious code and potentially result in flawed or incomplete evaluations.

Dynamic analysis of ransomware requires executing the malware in a controlled environment, such as a sandbox, to monitor its behavior. This approach is effective due to the direct interaction it enables, allowing researchers to observe the ransomware’s activities. However, the primary risk of dynamic analysis is the potential spread of malware within the lab environment. Additionally, advanced ransomware may detect the sandbox environment and alter its behavior, remaining dormant to evade detection. Some studies have proposed various detection methods, such as analyzing the encryption process, which involves repetitive patterns that can be examined at the file system level to identify ransomware behavior [18]. Tracking the frequency of encryption is another technique to distinguish between malicious attacks and legitimate encryption processes. A dynamic analysis approach involves monitoring system API calls to track ransomware interactions with the operating system [19].

In [20], the authors introduced a similar framework for detecting crypto-ransomware, named RENTAKA. This framework used the RISS dataset as a reference and successfully reduced the number of features to 80. However, this reduction caused a 3% decrease in detection accuracy, lowering the detection rate to 97.03% when using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier, compared to [21]. The authors also employed several classification models, including SVM, Random Forest, Naive Bayes, KNN, and J48. Despite these advancements, the study lacks detailed information about the proposed model, and it does not clarify which encryption APIs were targeted during the analysis. A study on API-based ransomware detection was proposed by [22], using a feature importance technique. The authors analyzed API calls to identify specific patterns of ransomware behavior. They collected 653 executable files, including both benign and malicious applications. After conducting API analysis, they performed feature ranking and created a dataset for further use. The dataset was then provided to machine learning models, which were trained using four classifiers: Random Forest, C5.0, AdaBoost, and SVM. The highest detection accuracy achieved was 95.38% using the AdaBoost classifier. However, the primary contribution of this study lies in the application of feature ranking.

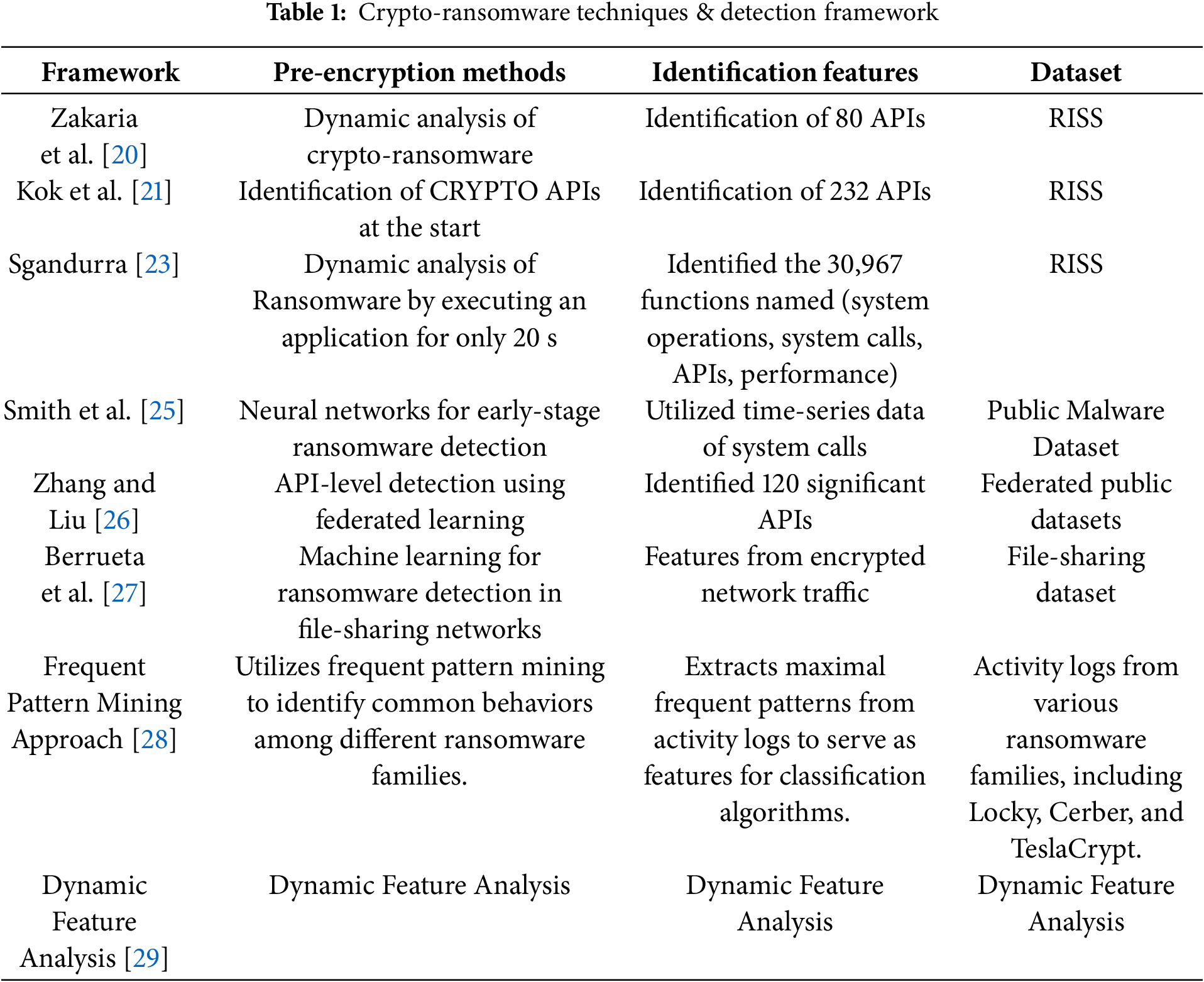

In [21], the authors analyze crypto-ransomware behaviors through function calls and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). They propose a two-level detection model: the first level uses signature-based detection, while the second level employs machine learning algorithms to detect ransomware based on API calls. The authors employed the RISS dataset [23], which contains 30,967 applications, including both benign and malicious ones. After analyzing the dataset, they extracted ransomware-specific features, resulting in a new dataset with 232 API features and 1800 entries. This new dataset was specifically focused on pre-encryption functions. Using machine learning, the authors achieved 100% detection accuracy with the Random Forest classifier. After detecting ransomware, the model stores its signature for future detections. The experiments were conducted using Cuckoo Sandbox (V2.0.6), Windows 10 Pro, and Ubuntu 18.04 platforms. However, there is potential for further optimization by reducing insignificant features while maintaining similar detection accuracy. Another recent study [24] proposed a similar model to Kok et al. [21], focusing on API-based detection, but reduced the number of features from 232 to 206. However, this reduction led to a 1% decrease in detection accuracy when using the K-NN classifier. While both models focus on detecting known ransomware. Table 1 presents a comprehensive overview of commonly employed techniques for ransomware detection.

It is observed that the above methods achieved high detection accuracies, however, they also employed a larger number of features, i.e., 323, 80, 100, 120. That further can be reduced, or only effective API calls can be employed for real-time detection. Secondly, the above methods are totally dependent on ML-based detection models, which can be optimized with signature matching for existing and future ransomware. Finally, the existing methods employed the custom or proprietary ransomware sample dataset, which is inaccessible to researchers in this domain.

This study proposes an optimal approach for detecting ransomware before it is executed, thereby minimizing potential damage to an organization. A dynamic solution is introduced to enable early detection through signature matching through an updated database, as well as the use of API calls and machine learning techniques. The proposed model identified only 26 features and can detect both known and unknown ransomware variants on the available sample dataset.

3 Overview of the Proposed Pre-Encryption Detection Model

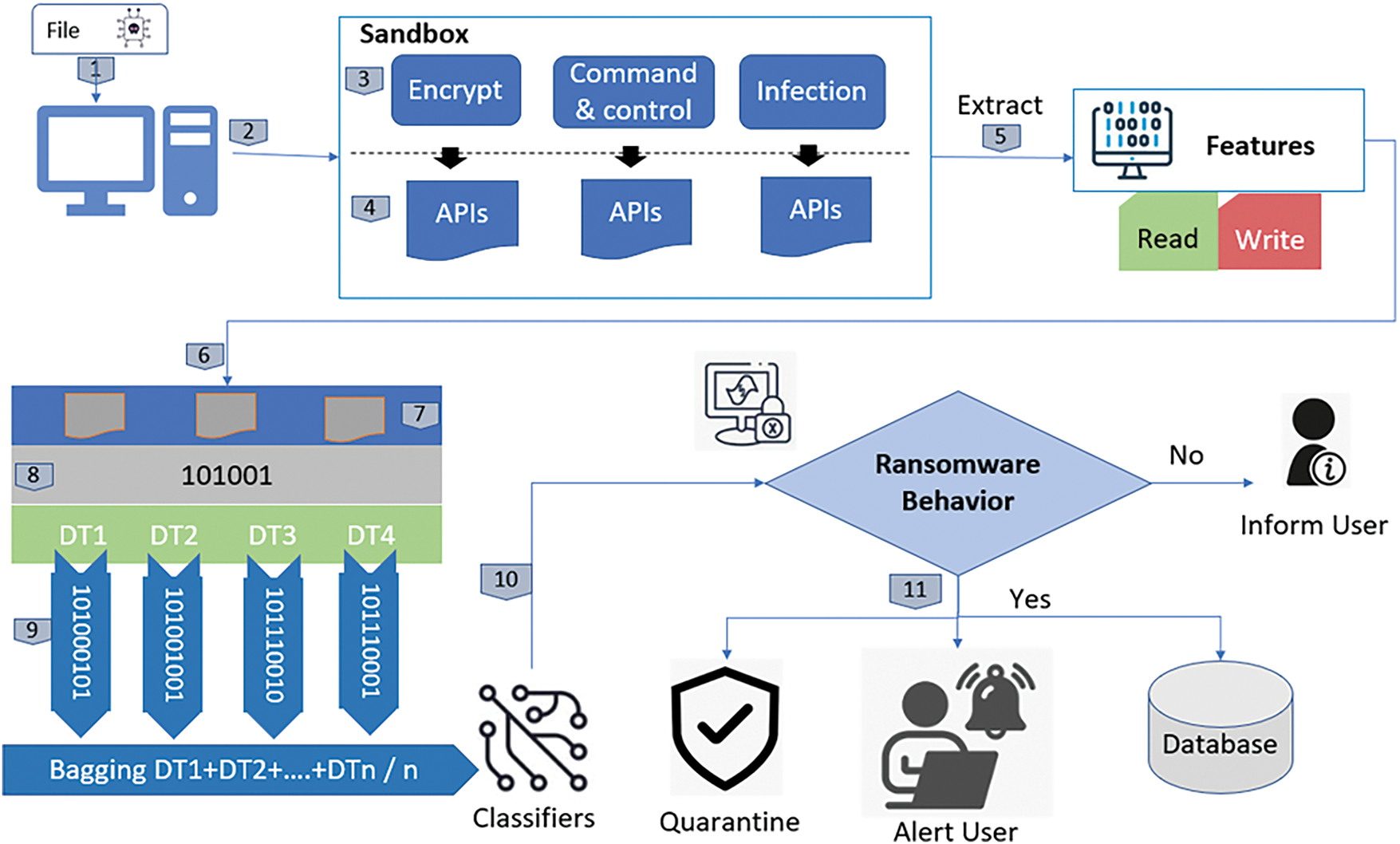

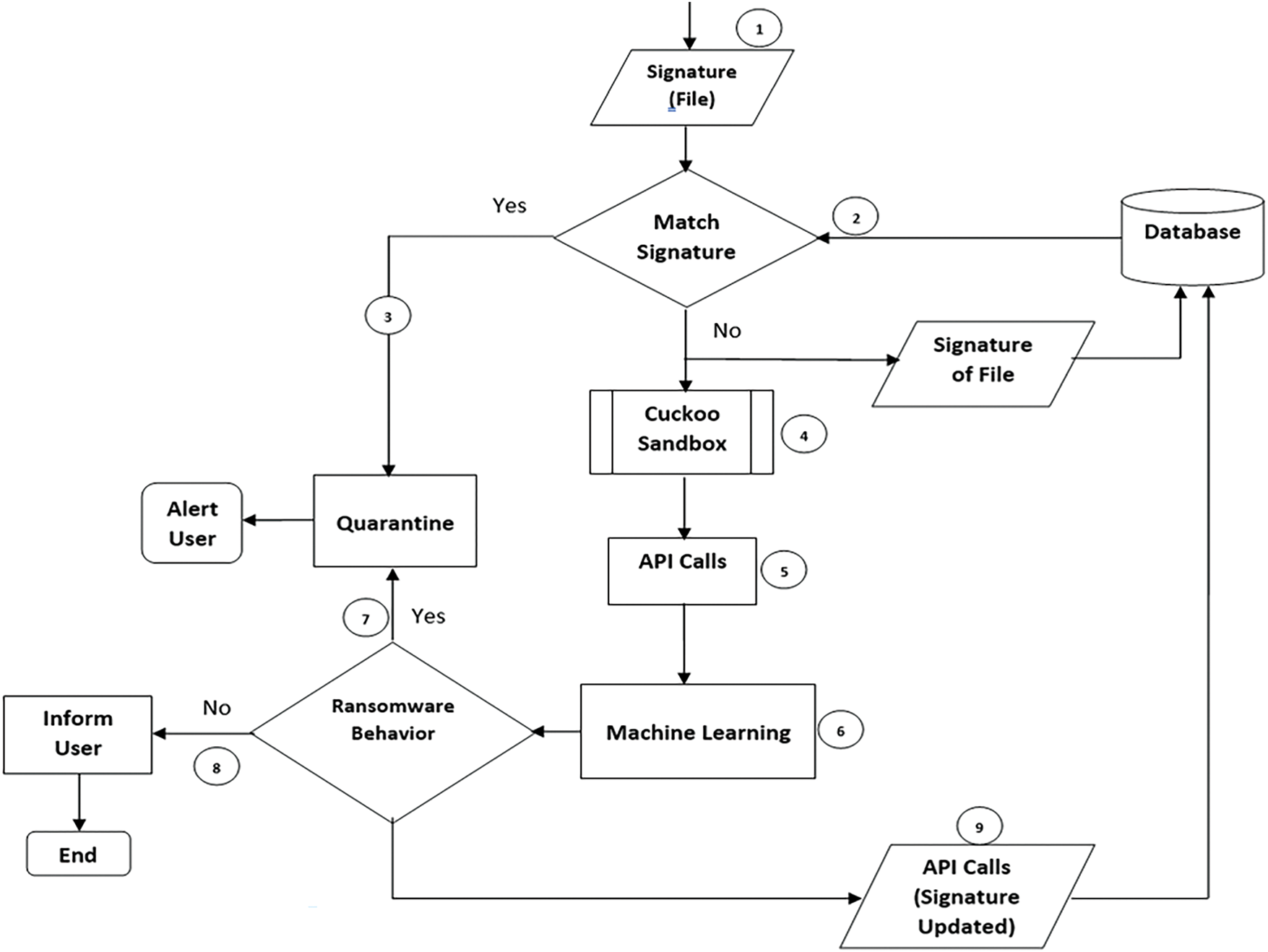

In this section, we discuss the proposed pre-encryption detection model of ransomware, which consists of two phases. The first phase focuses on identifying known ransomware using a signature database. The second phase involves analyzing system calls or APIs to identify ransomware behavior (discussed in Section 4), aided by a trained machine learning algorithm. This approach allows for the detection of previously unknown ransomware. The overview of the proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Flow diagram of the proposed detection model

In the first phase, the proposed approach allows users to inspect files before opening them to identify potential ransomware threats. The user selects a file for analysis, and the model generates its SHA-256 hash signature, a unique 256-bit fingerprint based on the file’s contents. This hash is then compared against known ransomware hashes stored in the Signature Archive. Hash comparison is more efficient than analyzing the entire file and requires minimal storage. If a match is found, the pre-encryption approach alerts the user and isolates the file. However, this method is limited to detecting known ransomware.

In the case of an unmatched file, the second phase of the proposed model is executed by sending the files to the Cuckoo Sandbox for further analysis of potential unknown malware. The file is executed in a secure virtual environment, where its behavior is monitored. Once the processing is complete, Cuckoo generates an analysis report for the file. In this study, we focus on the APIs that are employed for opening and accessing files. The pre-encryption model identifies these APIs before the encryption function call occurs.

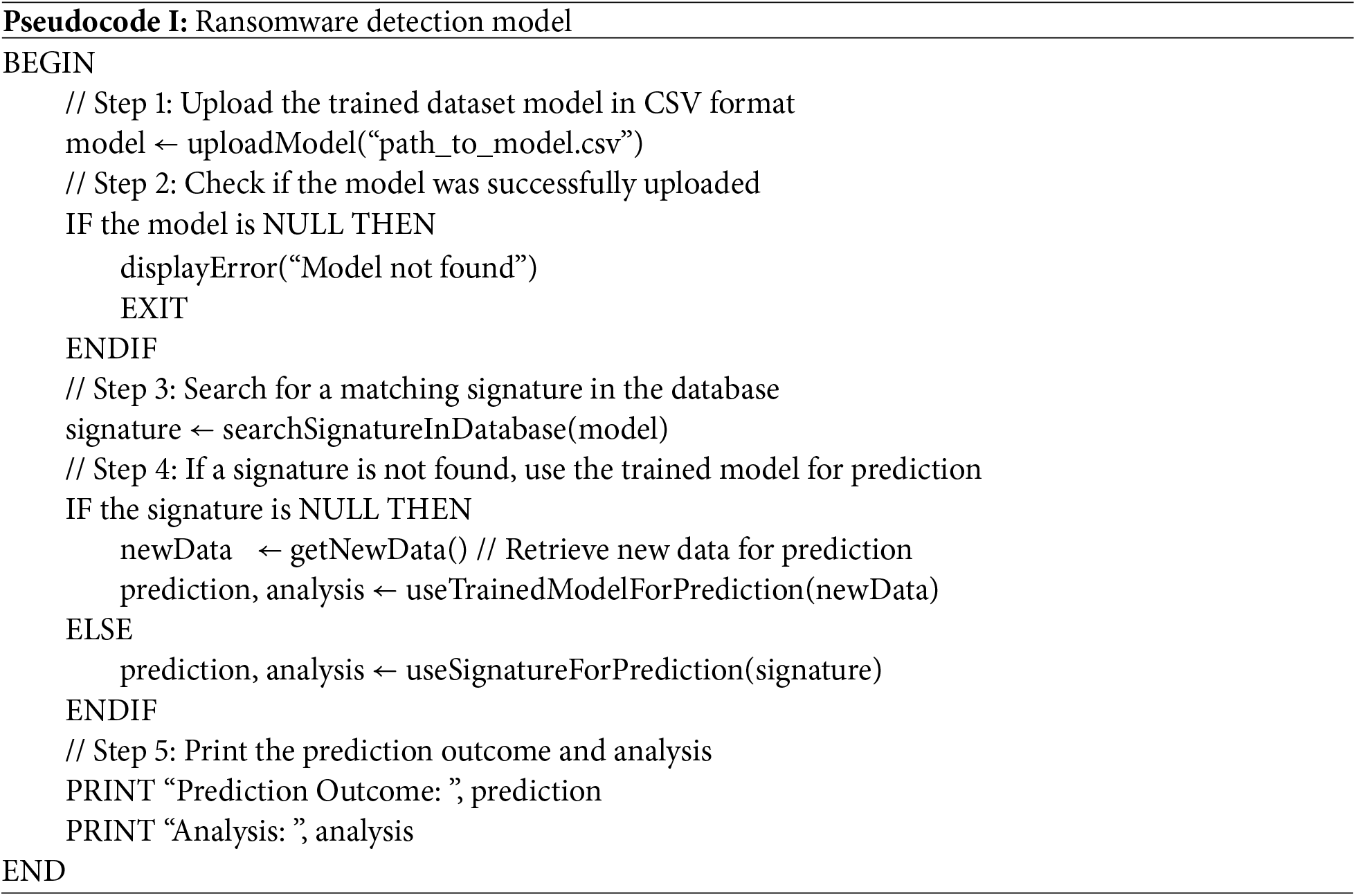

The model searches for the keyword “crypt” within the APIs. If the keyword is found, the API is recorded, and the process proceeds to the next stage. After the APIs are converted into a suitable data format in a comma-separated values (CSV) file. The machine learning model is then applied to the extracted API for classification. The pseudocode is as follows (Pseudocode I).

Discretization is a pre-processing phase that converts continuous data into discrete values to enhance the predictive accuracy of machine learning algorithms [30]. It typically employs rules-based and tree-based algorithms. While there are numerous techniques available for discretizing continuous variables, the optimal approach divides the variable into a meaningful number of intervals that align with the intended classification of the data.

After discretizing the data, the following ML classifiers are employed to detect ransomware in files: Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Decision Tree, K-Nearest Neighbors, and Naive Bayes. If ransomware is detected, the pre-encryption model will alert the user, quarantine the file, and store its signature in the Signature Repository. If the model determines that the file is not ransomware, the user will be notified that the file is safe to open.

Hashing is a form of encryption that uses a one-way function [31], generating a digest code that cannot be reversed to retrieve the original plaintext. Even a minor change in the content results in a completely different digest code. Comparing these digest codes is a common method for verifying message integrity. For our experiments, we employed the SHA-256 function. Initially, we calculated the message length and appended extra bits if its size deviated from 64 bits, ensuring that the total length became a multiple of 512. In such cases, the appended bits start with zero. The modulus of the original message with 232 is used to fill the final 64 bits. A compression algorithm is then applied to the resulting 512-bit message. The hashing operation is repeated 64 times to generate the final hash.

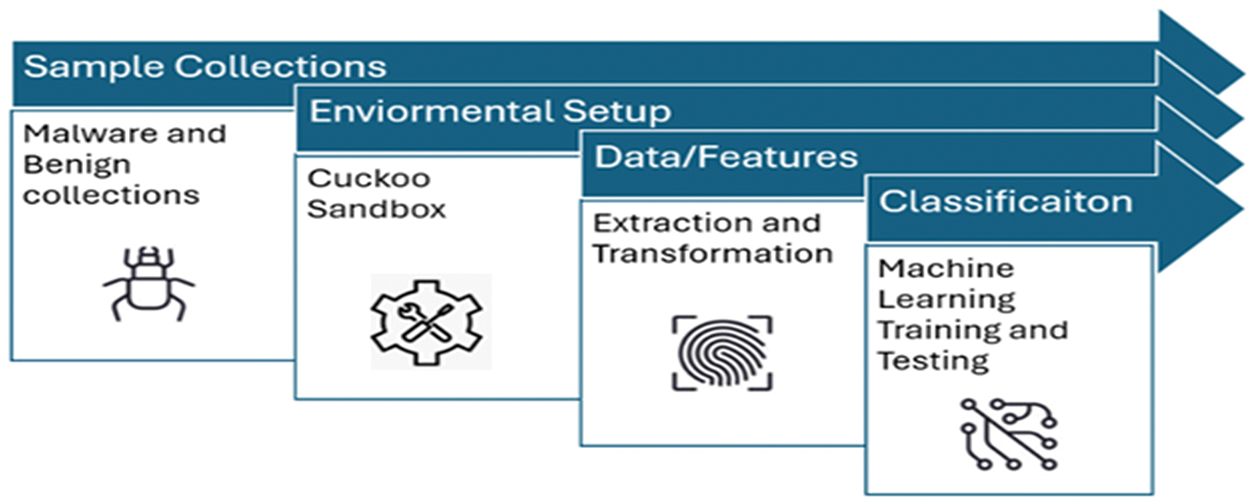

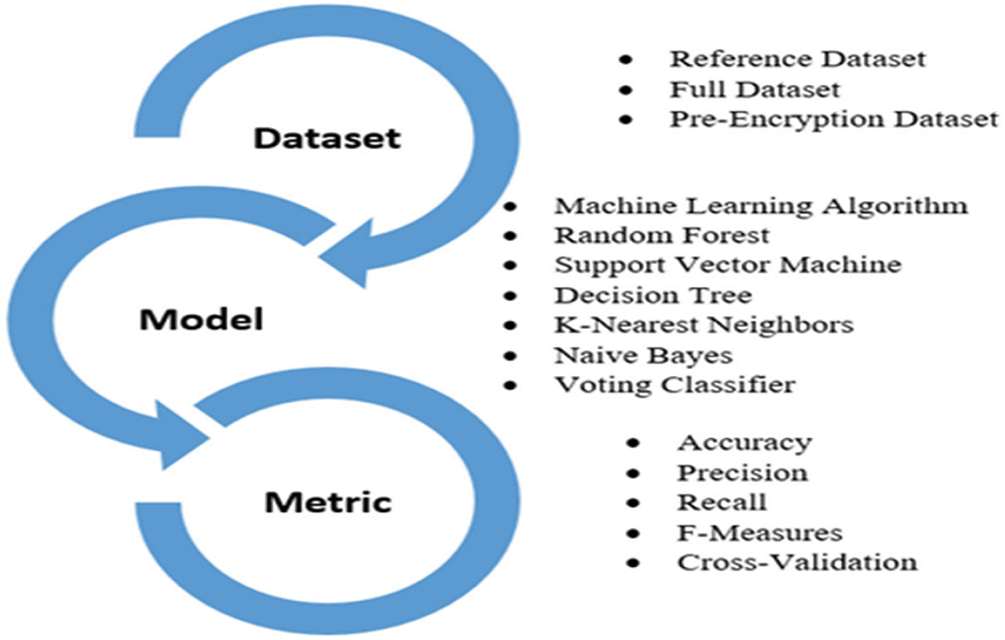

In this section, we present the proposed methodology for ransomware detection. The study is organized into four key components shown in Fig. 4: Sample Collection, Cuckoo Sandbox, Data Extraction, Machine Learning, and Database. Further details are as follows.

Figure 4: Components of the proposed approach

Ransomware Samples

This section discusses the collection of ransomware data. The process began with the dataset from Sgandurra et al. [23], which included 582 ransomware samples from eleven different categories, along with 942 benign applications (Goodware). This dataset encompasses Locky ransomware and crypto-ransomware, which exhibit varying file operations, strings, directory activities, deleted file extensions, registry key actions, and API metrics. Each application was analyzed for 30 s to record its features. An important component of the dataset is the API, which reveals how an application interacts with the operating system. Previous studies have shown that API-based attributes significantly impact detection rates, which is why we also use API-based features. Initial dataset samples were downloaded from RISS [23].

To further enhance the dataset with novel ransomware samples and other additional samples, we obtained from both VirusShare and theZoo (TZ) repositories. VirusShare is available to security experts, incident investigators, forensic professionals, and other users, containing ~34 million samples, with access requiring registration and verification by the site administrator. Additionally, 357 fresh crypto-ransomware samples were sourced from various websites, and 56 crypto-ransomware samples were collected from TZ.

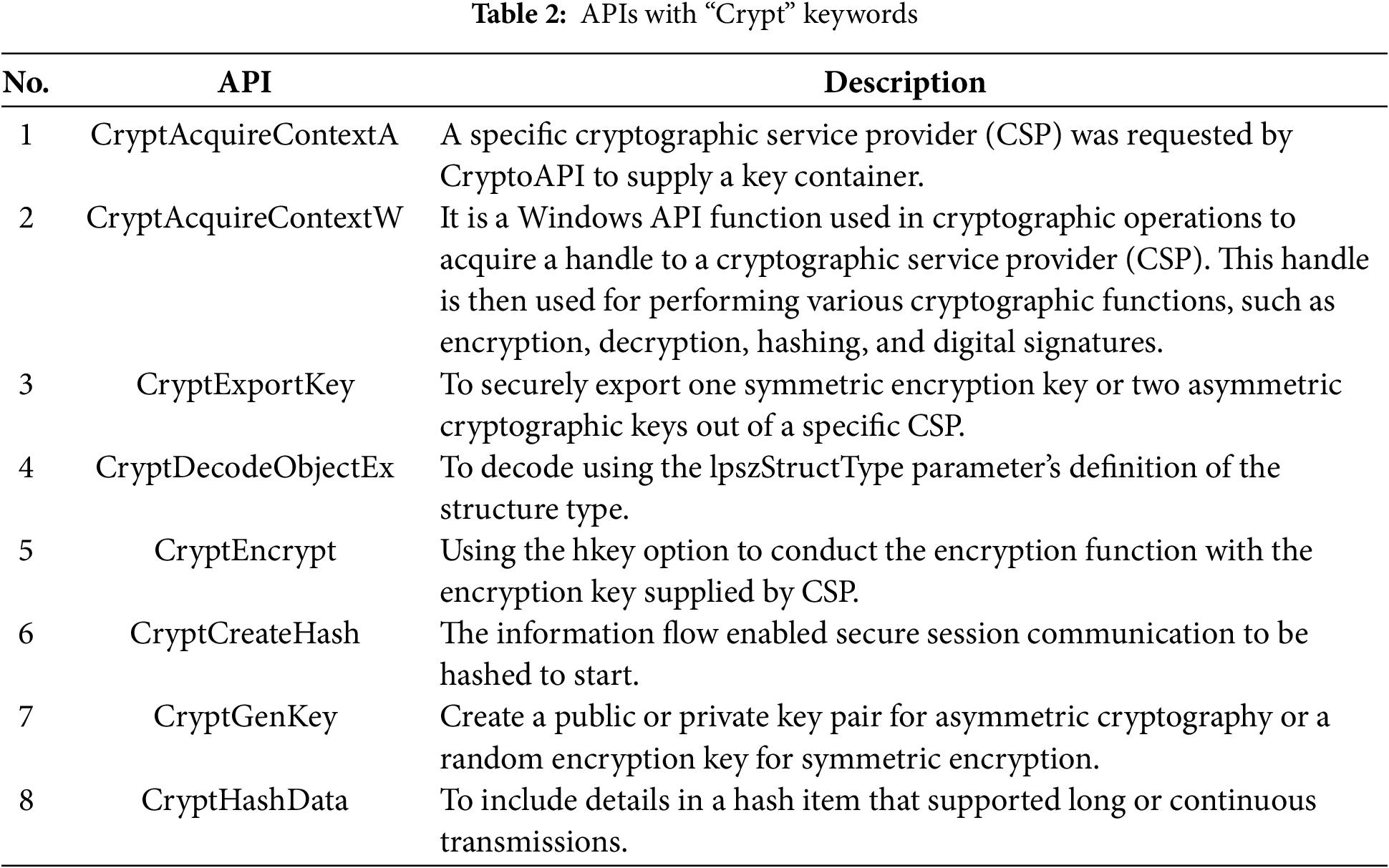

As a result, 995 software samples are executed in Cuckoo Sandbox, with 904 providing relevant reports. The Cuckoo Sandbox is used to execute the collected samples and select the pre-encryption samples. The Sandbox report listed the order in which each sample called APIs during different iterations. For instance, an API sequence containing the keyword “crypt” was selected, as it is found that APIs with this keyword execute encryption functions. In total, there were 205 samples related to encryption, some of which are shown in Table 2.

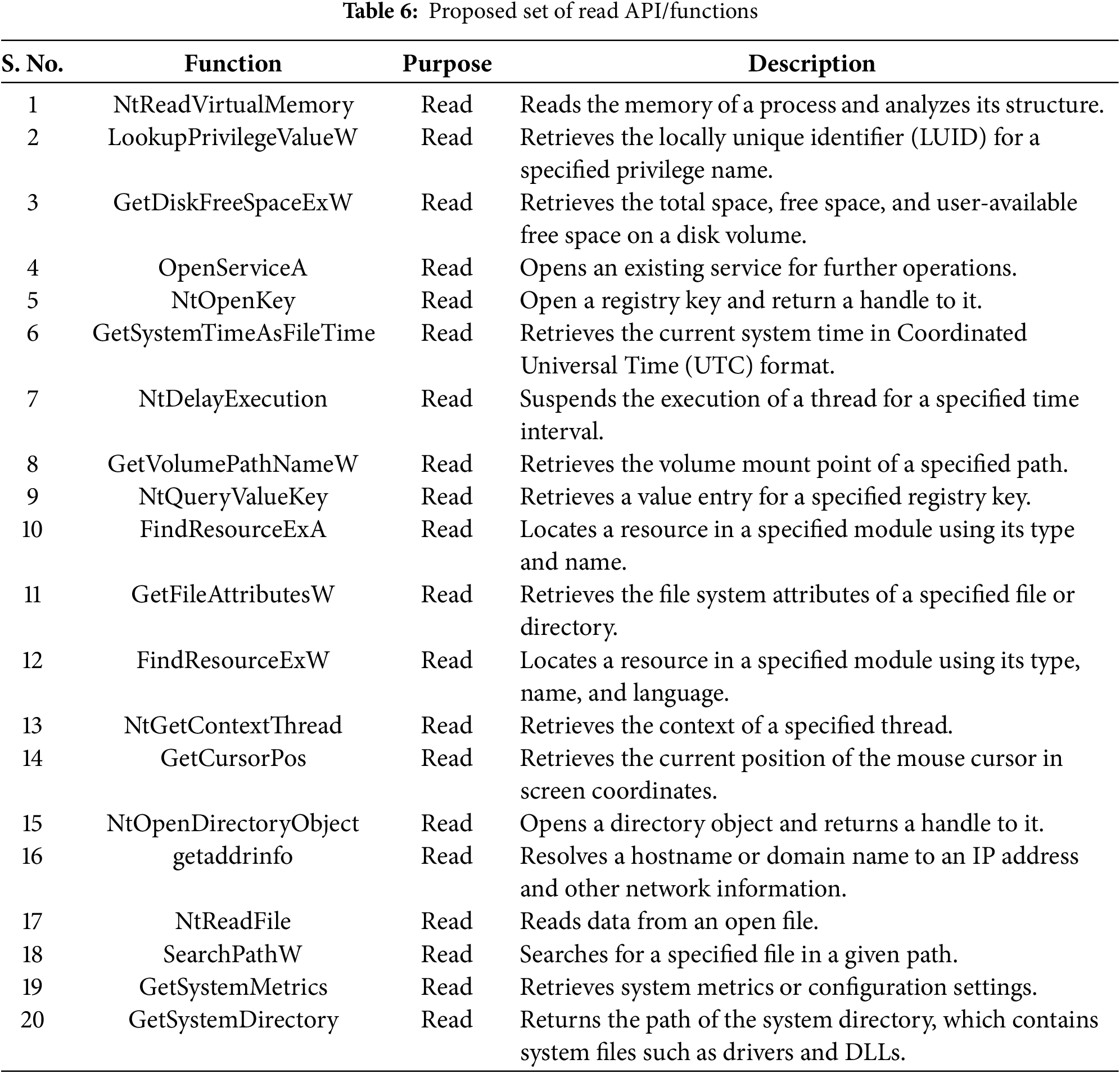

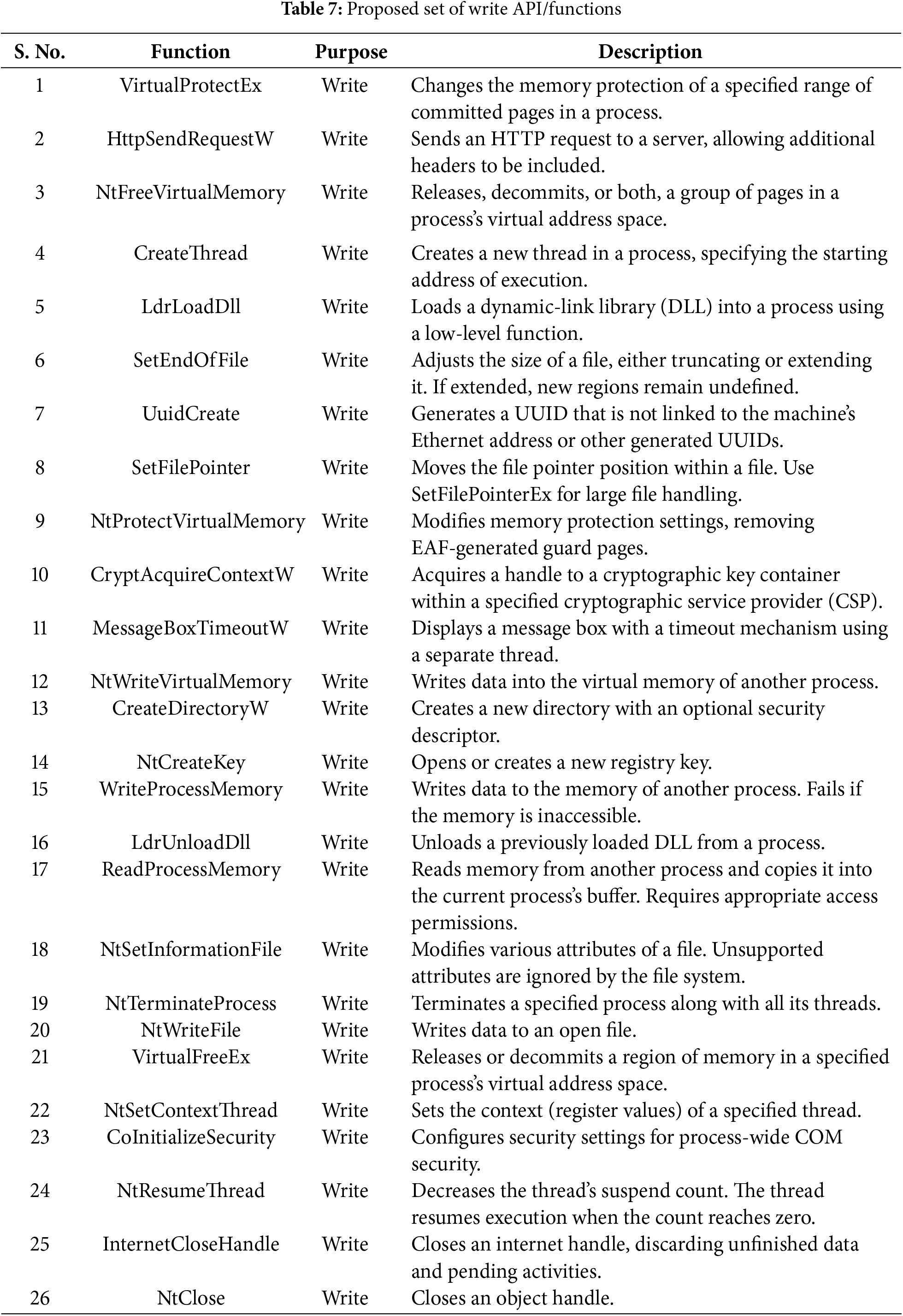

Initially, we collected APIs containing the keyword “crypt”, as they were primarily responsible for ransomware detection. To enhance efficiency, we analyzed these “crypt” APIs and identified those with a higher contribution to file encryption. Through feature ranking and detailed analysis, we extracted 46 APIs that were directly responsible for converting file content from plaintext to ciphertext. Since these APIs had both read and write permissions, we classified them into 20 read APIs and 26 write APIs. Further analysis revealed that the 26 write APIs played a more significant role and demonstrated higher accuracy compared to all APIs containing the “crypt” keyword.

These APIs are specifically used for data encryption, granting direct access to file system objects. In ransomware operations, APIs are exploited to systematically encrypt user files by reading plaintext data, applying cryptographic transformations, and writing the ciphertext back to storage. Additionally, ransomware often abuses these APIs to overwrite original files, delete volume shadow copies, and modify registry entries to prevent recovery.

Cuckoo Sandbox

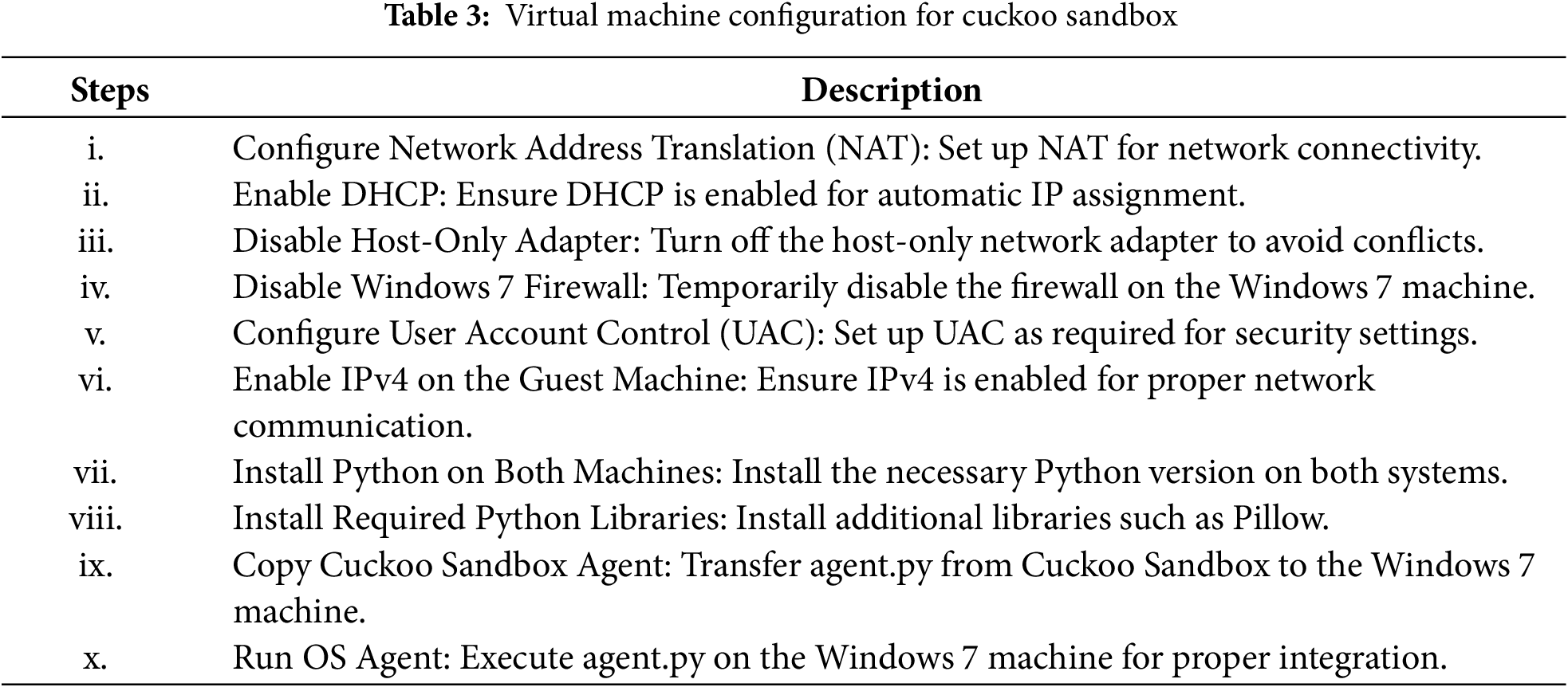

The Cuckoo Sandbox monitors program execution by recording all API calls made by a sample. After execution, it generates a detailed report of these calls. Cuckoo was installed on a Haier system (Intel Core m3-7Y30, 8 GB RAM, Ubuntu 20.04, Windows 10 Pro), though its configuration was complex. Required dependencies included Python 2.7, Python 3, MongoDB, PostgreSQL, XenAPI, TCPdump, and VirtualBox. After meeting these requirements, Ubuntu 20.04 successfully installed Cuckoo Sandbox 2.0.7. For secure analysis, a Windows 7 guest machine was set up in VirtualBox before deploying Cuckoo, as Windows is a common ransomware target.

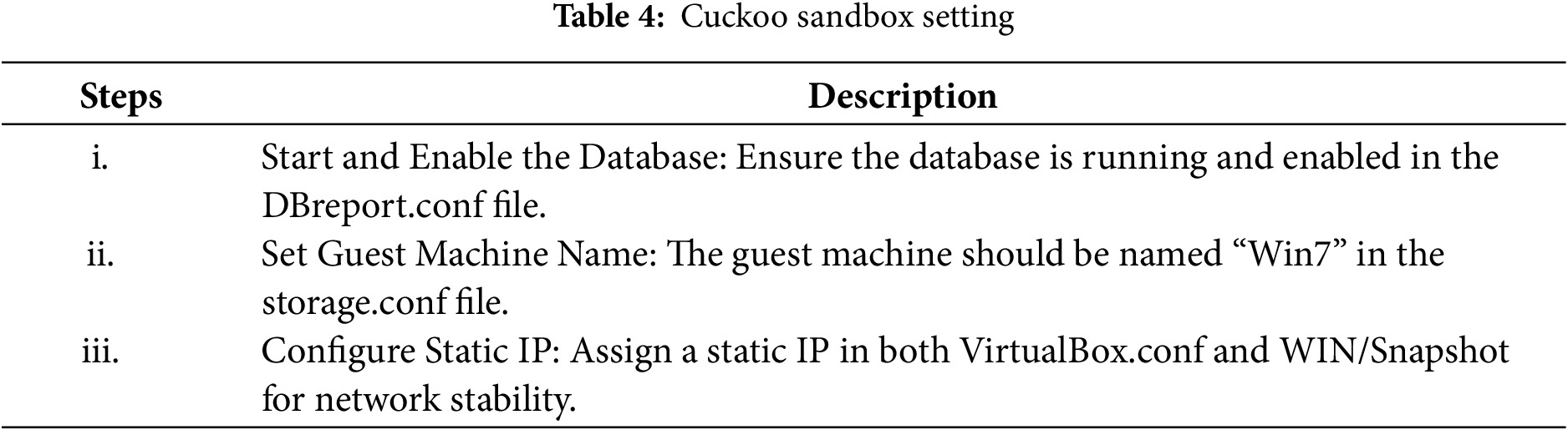

The Windows 7 guest machine is set up in VirtualBox and configured according to the network requirements listed in Table 3, enabling its connection to the Cuckoo Sandbox host machine. A screenshot of the guest computer was taken to ensure it could be restarted without issues for each analysis. The default Cuckoo Sandbox settings were modified, as detailed in Table 4. The guest machine needed to be initialized in VirtualBox before conducting sample analysis in Cuckoo Sandbox, after which the Cuckoo Web service could be started. On average, processing each sample took approximately 3 min.

By executing the program, we identify and record all API calls made by the sample in the Cuckoo Sandbox. The generated report, listing all API calls, can be accessed either by downloading it through the browser or by retrieving the file from “/.cuckoo/STORAGE/ANALYSIS/2/REPORTS/report.json”.

For this investigation, the latter method was chosen, as it generates a compressed .rar file containing multiple files, with all API calls recorded in a single .json file.

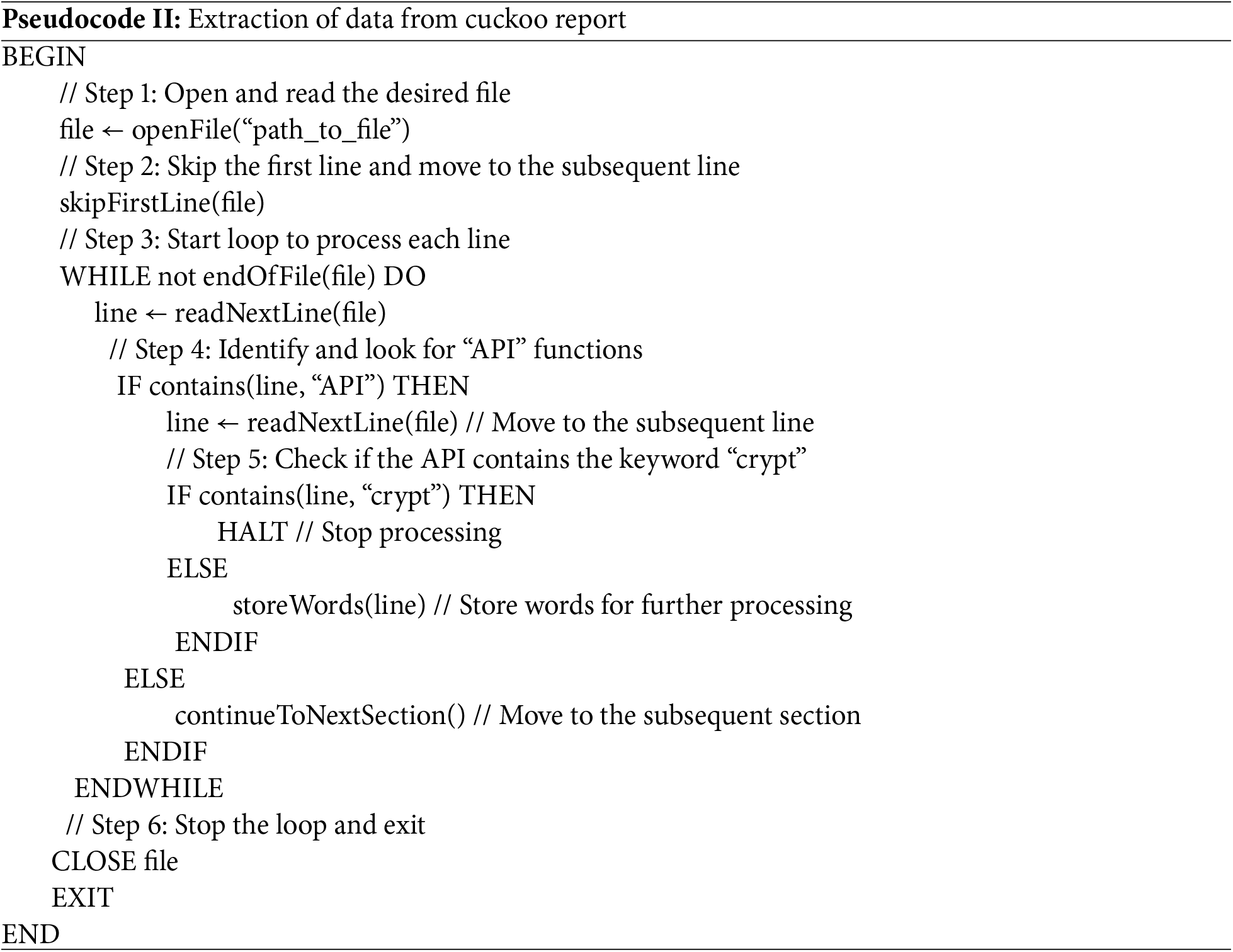

Extraction of Data

It is necessary to retrieve only significant data from the Cuckoo Sandbox report, as the information provided was extensive and unrelated to our investigation. All pre-encryption APIs were monitored for their behavior before invoking any encryption functions. To ensure that the script extracted the required data accurately, we developed a script to differentiate each API and compared its output against the “apistats” section in the Cuckoo report. After verifying that the code produced identical results, the keyword “crypt” was designated as the extraction endpoint. The pseudocode for extracting the “crypt” call is presented below (Pseudocode II).

The data processing outlined above resulted in a ‘txt’ format, which was then converted into a ‘CSV’ file format to enable the ML algorithms to use it. This ‘CSV’ contained 235 entries, with the sample name in the first column, the second column indicating whether the sample was benign (zero) or ransomware (one), and the third column providing the source indication for the sample. After extracting APIs from all samples, 232 APIs were identified. Based on the retrieved data, we further analyzed and focused on extracting only read and write APIs due to their role in file data manipulation. Using feature ranking and functionality assessment, we selected 46 APIs from 232, comprising 20 read APIs and 26 write APIs. These APIs play a critical role in encryption by reading file content and writing encrypted data to memory. Given their significance, we prioritized these APIs and observed that detection based on them produced better results than other methods.

4.4 Implementation and Classifications

In this section, ML algorithms are employed to distinguish between known and unknown ransomware attacks. The process was divided into two steps: first, the data was discretized; then, the Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Decision Tree, KNN, Naive Bayes, and Voting Ensemble algorithms were used to train prediction models. All three datasets were used to evaluate the model’s performance at two different training-to-testing ratios. The data for both training and testing were divided using the initial ratio of 80:20. The second ratio, 70:30, allocated 70% for training and 30% for testing. Additionally, 10-fold validation tests were conducted. The overall ML algorithms evaluation strategy on datasets is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Machine learning algorithm model analysis

Signature Database

When the machine learning model identifies a sample as ransomware, its hash signature, along with other essential details stored in a MySQL database server as part of the experimental setup. The hash is generated using the SHA-256 algorithm, producing a 64-character string that uniquely represents the malware file. This approach enables rapid content-based matching, allowing for immediate identification of ransomware without relying on Cuckoo Sandbox analysis. On average, Cuckoo Sandbox requires 2 to 4 min to analyze a single file.

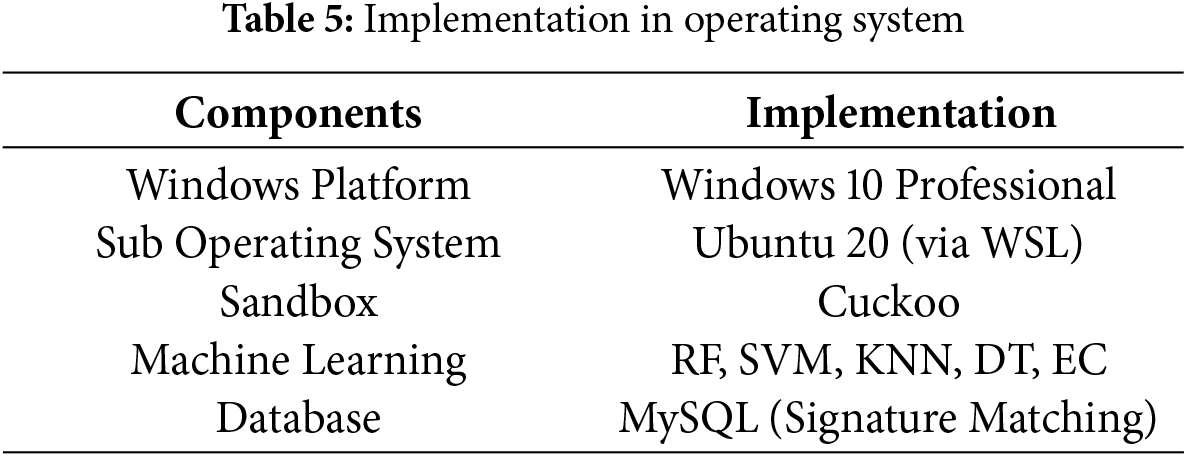

5 Model Implementation and Verification

Pre-encryption detection is designed for implementation on Windows platforms using Python. While Cuckoo Sandbox is traditionally a Linux-based tool, research revealed that Linux can be installed as a subsystem on Windows through the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) feature. This innovative approach enables Cuckoo Sandbox to coexist with Windows, making it compatible with platforms such as Windows 10 Professional, as specified in Table 5.

In this setup, Ubuntu 20 is installed as a subsystem within Windows, creating the necessary Linux environment for deploying Cuckoo Sandbox. The sandbox works in conjunction with MySQL, which serves as a signature repository. The integration involves ML algorithms to enhance the pre-encryption detection process. These algorithms analyze the data collected by Cuckoo Sandbox, identifying ransomware efficiently. When the ML model detects ransomware, a signature is generated for the malicious file and stored in the MySQL database, which is managed through an Apache server. This enables fast comparisons between incoming file hashes and stored ransomware signatures, ensuring precise detection in subsequent encounters.

Once ransomware is identified, the system alerts the user through a graphical user interface (GUI). It then isolates and removes the infected file. To further neutralize the threat, the ransomware’s extension is removed, effectively deactivating it and preventing further execution. This method uses advanced ML techniques and practical deployment strategies, making it an effective way to fight ransomware on Windows.

5.2 Pre-Encryption Model Verification

API pattern identification using the trained ML algorithm of the pre-encryption model is illustrated in Fig. 6. When a test file is initially labeled as ‘Unmatched’, its pre-encryption API calls are extracted and analyzed to recognize patterns for classifying it as either ‘Goodware’ or ‘Ransomware’. If the file is subsequently classified as Ransomware, the system checks the signature repository for an existing match. In the absence of a match, the repository is updated with the new signature.

Figure 6: Pre-encryption verification model

In this section, we evaluate and compare the performance of the proposed and existing techniques using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, True Positive Rate (TP Rate), False Positive Rate (FP Rate), F-measure, and cross-validation. The TP Rate measures how effectively the model correctly predicts positive cases, while the FP Rate indicates how often it incorrectly classifies negative cases as positive. Accuracy assesses the overall effectiveness of the model in identifying ransomware, whereas precision evaluates the correctness of positive predictions, and recall measures how well the model detects all relevant positive instances.

The F-measure balances precision and recall, providing a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance. Additionally, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve represents the TP Rate vs. FP Rate, while the Precision-Recall Curve (PRC) plots precision against recall.

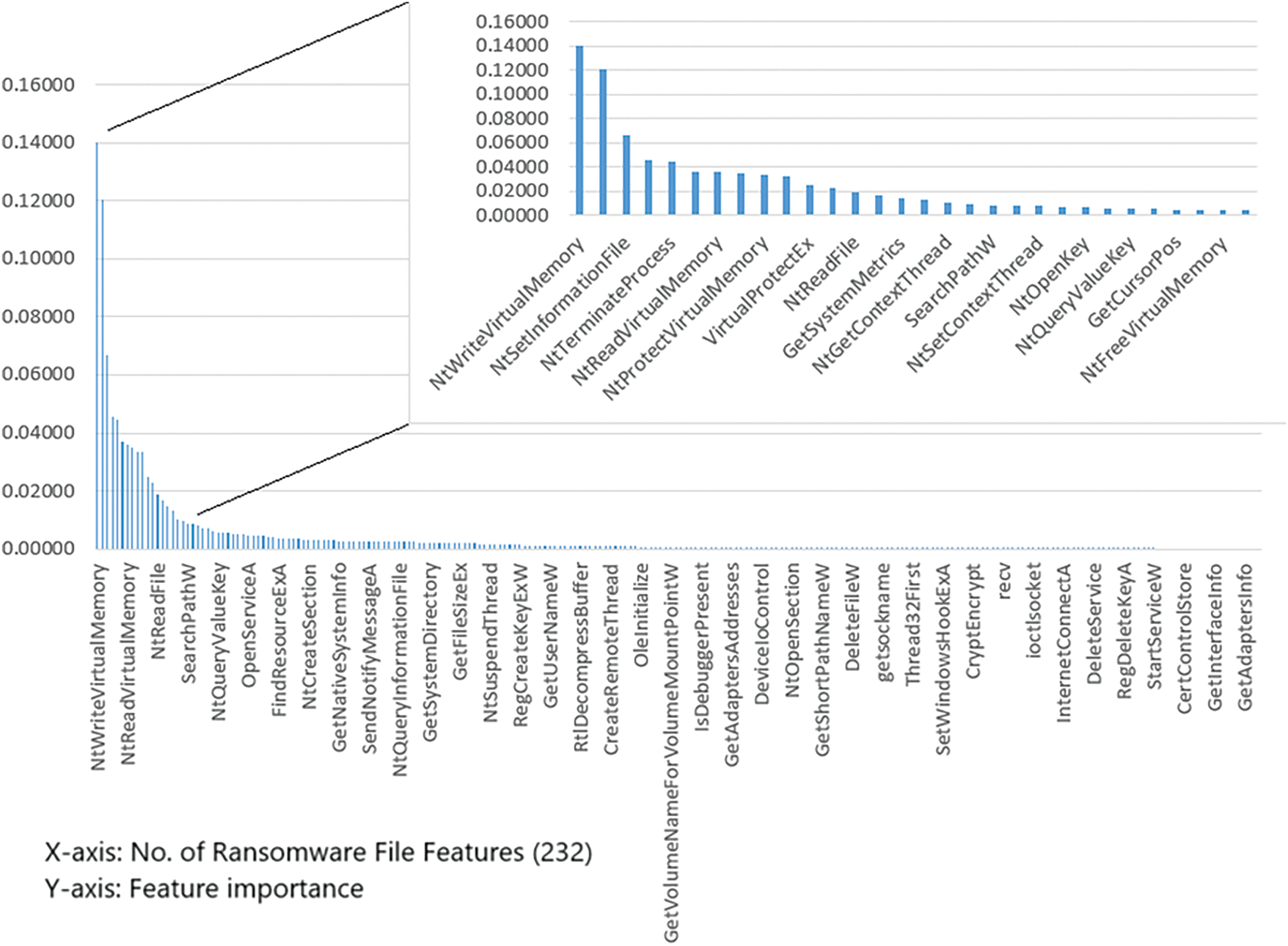

From Fig. 7, it is notable that to achieve 100% accuracy, 232 API features were employed. However, from our experiments, we identified only 46 API calls that are sufficient for maintaining a detection accuracy of 99%. The feature importance based on the random forest classifier highlights the features that contribute the most to the detection mechanism. We further categorized the 46 APIs into reading and writing functions/APIs to identify their significant contributions. The identified read-and-write APIs in the proposed model include 20 read functions and 26 write functions, as detailed in Tables 6 and 7.

Figure 7: Feature importance based on the random forest classifier

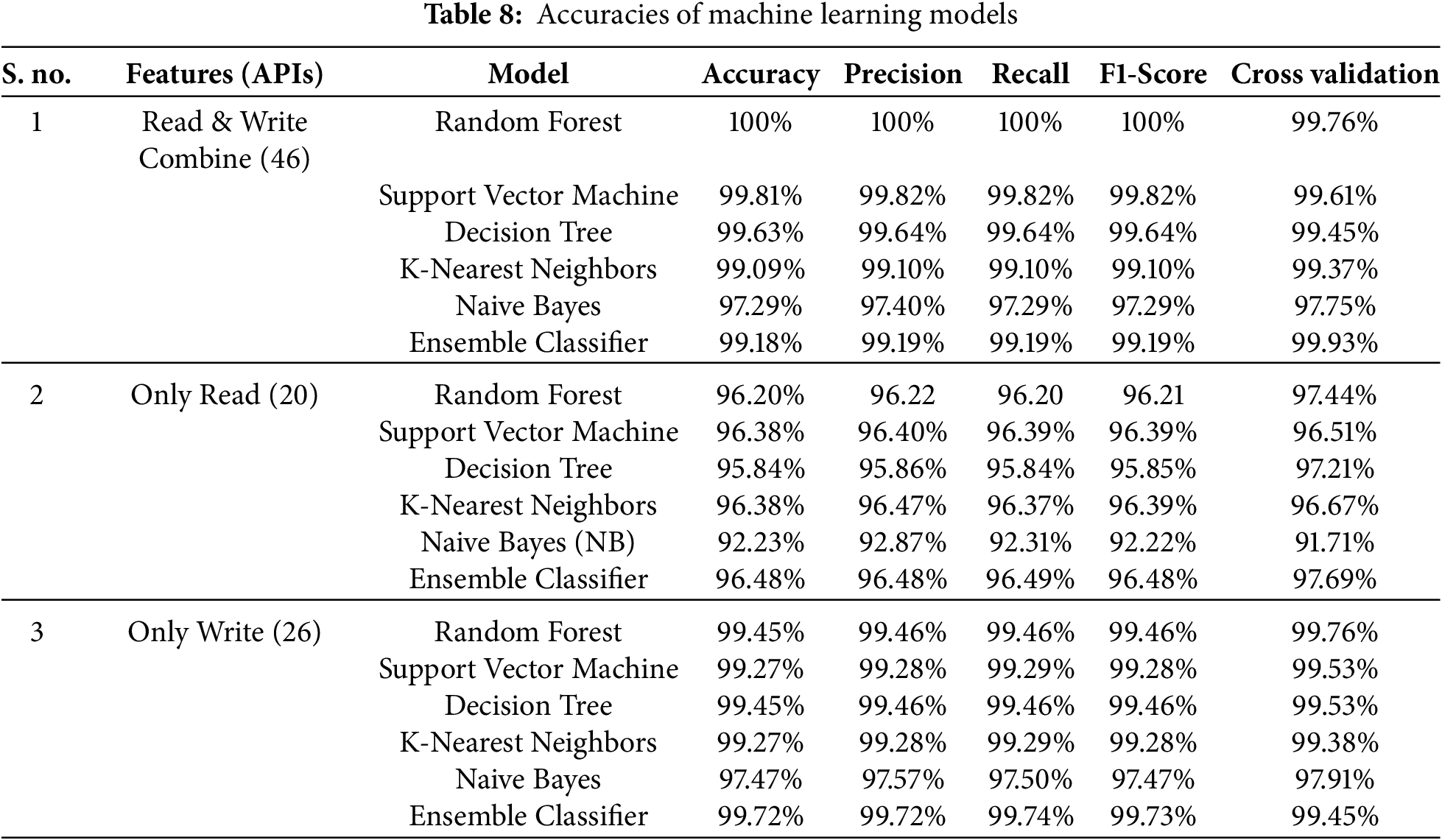

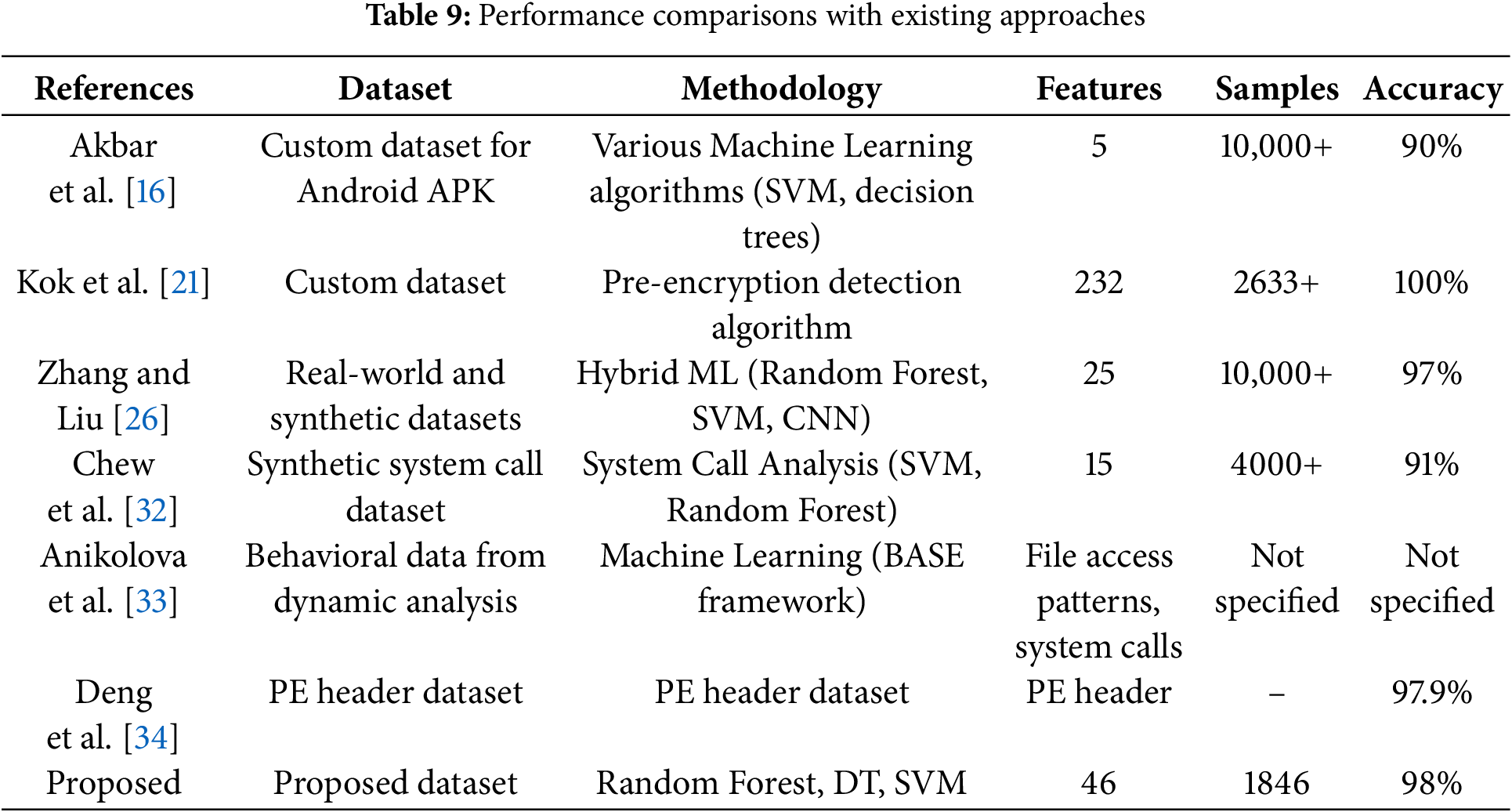

Table 8 shows the accuracy of machine learning models along with precision, recall, F1 score, and their cross-validation checks. We achieved 100% accuracy using the Random Forest model, 99.81% using Support Vector Machine, 99.63% using the Decision Tree, 98.09% using K-Nearest Neighbors, 97.29% using Naive Bayes, and 99.18% with the Ensemble Classifier for 46 features. Additionally, when analyzing the reading functions, we obtained the following accuracies: 96.20% using Random Forest, 96.38% using Support Vector Machine, 95.84% using Decision Tree, 96.38% using K-Nearest Neighbors, 92.23% using Naive Bayes, and 96.48% with the Ensemble Classifier.

We focused on the write functions, as they play a crucial role in ransomware activity, especially in the initial stage when files are encrypted, making it more significant than read functions. We achieved 99.45% accuracy using Random Forest, 99.27% with Support Vector Machine, 99.45% with Decision Tree, 99.27% with K-Nearest Neighbors, 97.47% with Naive Bayes, and 99.72% with the Ensemble Classifier, which averages all classifiers. This means that we can achieve the same accuracy as presented previously in [21], using only 26 features of the write function APIs. Our collected dataset is also verified using other machine learning models, Support Vector Machine, Decision Tree, K-Nearest Neighbors, Naive Bayes, and Ensemble Classifier with Random Forest, which showed better results with fewer API functions.

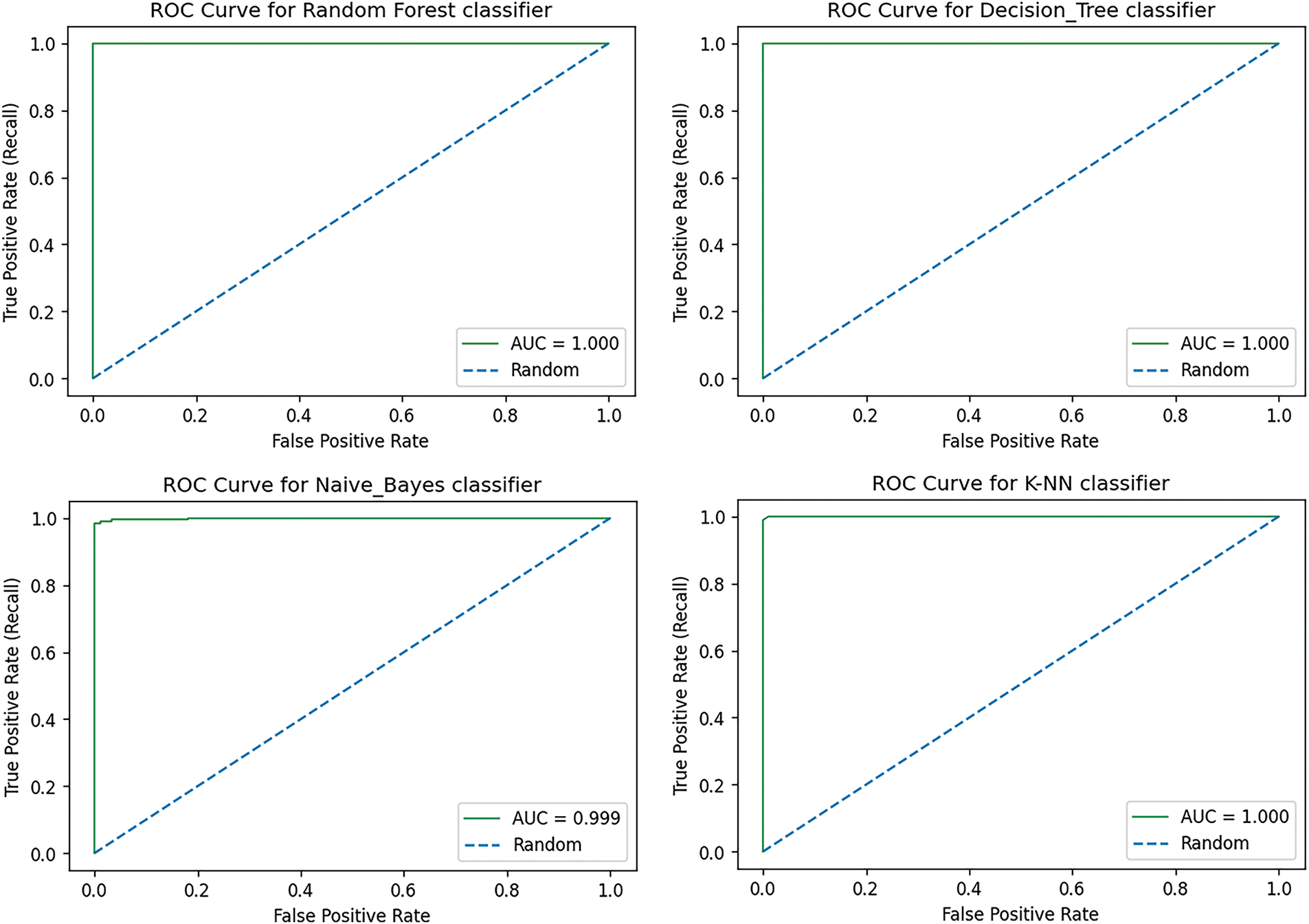

Similarly, for evaluating other evaluation matrices, such as ROC curves, that are used to measure the probability of classification models at different levels. The curve has a true positive rate along the x-axis and a false positive rate along the y-axis. Fig. 8 represents ROC curves of different machine learning models.

Figure 8: ROC curves of ML models

The performance of the proposed method is evaluated and compared with recent ransomware detection models, as shown in Table 9. In [32], the authors employed system call data analyzed with various machine learning algorithms, achieving a detection accuracy of up to 91%. Similarly, Kok et al. [21] reported 100% detection accuracy on a custom sample dataset. However, their approach utilized a significantly larger feature set (232 features) compared to the 46 features employed in our method, and their dataset was proprietary. Zhang et al. [26] achieved a comparable 97% accuracy using a minimal feature set of 25 features. However, their dataset was synthetic, and they relied on advanced and complex machine learning models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Additionally, Akbar et al. [16] achieved 90% accuracy using only 5 features. However, their study focused on general Android malware, including ransomware, without specifying the exact number of ransomware samples analyzed.

In contrast, the proposed method achieved 98% detection accuracy using only 46 features, evaluated on 1846 ransomware-specific samples. These results demonstrate that the proposed approach outperforms existing methods in terms of achieving high detection accuracy with a minimal number of features, offering a promising solution for effective ransomware detection.

This study has presented an early detection approach that effectively identified ransomware activity before encryption occurred. It integrated the two-tiered detection mechanism that combined signature-based hashing techniques with dynamic behavior analysis using Cuckoo Sandbox and machine learning. The first stage used hashing to compare file signatures against known ransomware, enabling rapid detection without execution. The second stage employed a trained machine learning model to analyze pre-encryption API calls, effectively identifying both known and unknown ransomware. Newly detected signatures were stored for future use, enhancing the model’s effectiveness over time. Additionally, the inclusion of critical API call monitoring further strengthened system-level threat analysis, enabling the identification of malicious activity with high precision. Experimental results demonstrated that the proposed approach achieved a 98% detection accuracy using 46 key ransomware attributes, compared to over 250 attributes used in other methods. The results were validated through an 80:20 training-to-testing ratio and 10-fold cross-validation. When compared to existing solutions, the proposed method could optimize the feature selection while maintaining robust performance, ensuring efficiency and lightweight ransomware detection.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) and Andong National University.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) and this research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1I1A3049788).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Mehdi Hussain, Ki-Hyun Jung; data collection: Asad Iqbal; analysis and interpretation of results: Asad Iqbal, Qaiser Riaz, Madiha Khalid, Ki-Hyun Jung; draft manuscript preparation: Mehdi Hussain, Asad Iqbal, Rafia Mumtaz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data is freely available and can give access on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ransomware attack report [Internet]; 2017 [cited 2025 Feb 10]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WannaCry. [Google Scholar]

2. Humayun M, Niazi M, Jhanjhi NZ, Alshayeb M, Mahmood S. Cyber security threats and vulnerabilities: a systematic mapping study. Arab J Sci Eng. 2020;45(4):3171–89. doi:10.1007/s13369-019-04319-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hull G, John H, Arief B. Ransomware deployment methods and analysis: views from a predictive model and human responses. Crime Sci. 2019;8(1):2. doi:10.1186/s40163-019-0097-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kok S, Abdullah A, Jhanjhi NZ, Supramaniam M. Prevention of crypto-ransomware using a pre-encryption detection algorithm. Computers. 2019;8(4):79. doi:10.3390/computers8040079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Cen M, Jiang F, Qin X, Jiang Q, Doss R. Ransomware early detection: a survey. Comput Netw. 2024;239(2):110138. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2023.110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Singh J, Singh J. A survey on machine learning-based malware detection in executable files. J Syst Archit. 2021;112(1):101861. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2020.101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lee S, Kim HK, Kim K. Ransomware protection using the moving target defense perspective. Comput Electr Eng. 2019;78(66):288–99. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.07.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ali Saleh Al-rimy B, Maarof MA, Shaid SZM. Crypto-ransomware early detection model using novel incremental bagging with enhanced semi-random subspace selection. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;101(1):476–91. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yu Z, Gao CZ, Jing Z, Gupta BB, Cai Q. A practical public key encryption scheme based on learning parity with noise. IEEE Access. 2018;6:31918–23. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2840119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Çeliktaş B. The ransomware detection and prevention tool design by using signature and anomaly based detection methods [master’s thesis]. Istanbul, Türkiye: Istanbul Technical University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

11. Ren A, Liang C, Hyug I, Broh S, Jhanjhi NZ. A three-level ransomware detection and prevention mechanism. EAI Endorsed Trans Energy Web. 2018;162691. doi:10.4108/eai.13-7-2018.162691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Alhawi OMK, Baldwin J, Dehghantanha A. Leveraging machine learning techniques for windows ransomware network traffic detection. In: Cyber threat intelligence. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2018. p. 93–106. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73951-9_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Aljabri M, Alhaidari F, Albuainain A, Alrashidi S, Alansari J, Alqahtani W, et al. Ransomware detection based on machine learning using memory features. Egypt Inform J. 2024;25(12):100445. doi:10.1016/j.eij.2024.100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Javan NT, Mohammadpour M, Mostafavi S. Enhancing malicious code detection with boosted N-gram analysis and efficient feature selection. IEEE Access. 2024;12:147400–21. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3476164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cimitile A, Mercaldo F, Nardone V, Santone A, Visaggio CA. Talos: no more ransomware victims with formal methods. Int J Inf Secur. 2018;17(6):719–38. doi:10.1007/s10207-017-0398-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Akbar F, Hussain M, Mumtaz R, Riaz Q, Wahab AWA, Jung KH. Permissions-based detection of Android malware using machine learning. Symmetry. 2022;14(4):718. doi:10.3390/sym14040718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qadir S, Naeem A, Hussain M, Ghafoor H, Hassan Abdalla Hashim A. Performance-oriented and sustainability-oriented design of an effective Android malware detector. IEEE Access. 2024;12(1):159036–55. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3486094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kardile AB. Crypto ransomware analysis and detection using process monitor [master’s thesis]. Arlington, TX, USA: The University of Texas at Arlington; 2017. [Google Scholar]

19. Gupta R, Sharma K, Garg RK. Covalent bond based Android malware detection using permission and system call pairs. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;78(3):4283–301. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.046890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zakaria WZA, Abdollah MF, Mohd O, Yassin SMWMSMM, Ariffin A. RENTAKA: a novel machine learning framework for crypto-ransomware pre-encryption detection. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2022;13(5):130545. doi:10.14569/ijacsa.2022.0130545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kok SH, Abdullah A, Jhanjhi NZ. Early detection of crypto-ransomware using pre-encryption detection algorithm. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(5):1984–99. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mohan Anand P, Sai Charan PV, Shukla SK. A comprehensive API call analysis for detecting windows-based ransomware. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR); 2022 Jul 27–29; Rhodes, Greece. doi:10.1109/CSR54599.2022.9850320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sgandurra D, Muñoz-González L, Mohsen R, Lupu EC. Automated dynamic analysis of ransomware: benefits, limitations and use for detection. arXiv:1609.03020. 2016. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1609.03020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Almousa M, Basavaraju S, Anwar M. API-based ransomware detection using machine learning-based threat detection models. In: Proceedings of the 2021 18th International Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST); 2021 Dec 13–15; Auckland, New Zealand. doi:10.1109/pst52912.2021.9647816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Smith D, Khorsandroo S, Roy K. Machine learning algorithms and frameworks in ransomware detection. IEEE Access. 2022;10:117597–610. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3218779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang R, Liu Y. Ransomware detection with a 2-tier machine learning approach using a novel clustering algorithm. Res Sq Forthcoming. 2024. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4567706/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Berrueta E, Morato D, Magaña E, Izal M. Crypto-ransomware detection using machine learning models in file-sharing network scenarios with encrypted traffic. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;209(6):118299. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Homayoun S, Dehghantanha A, Ahmadzadeh M, Hashemi S, Khayami R. Know abnormal, find evil: frequent pattern mining for ransomware threat hunting and intelligence. IEEE Trans Emerg Topics Comput. 2020;8(2):341–51. doi:10.1109/tetc.2017.2756908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Herrera-Silva JA, Hernández-Álvarez M. Dynamic feature dataset for ransomware detection using machine learning algorithms. Sensors. 2023;23(3):1053. doi:10.3390/s23031053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ahmad Azami NI, Yusoff N, Ku-Mahamud KR. Fuzzy discretization technique for Bayesian flood disaster model. J Inf Commun Technol. 2018;17(2):167–89. doi:10.32890/jict2018.17.2.8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gowthaman A, Sumathi M. Performance study of enhanced SHA-256 algorithm. Int J Appl Eng Res. 2015;10(4):10921–32. [Google Scholar]

32. Chew CJW, Kumar V, Patros P, Malik R. Real-time system call-based ransomware detection. Int J Inf Secur. 2024;23(3):1839–58. doi:10.1007/s10207-024-00819-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Anikolova E, Martins S, Rozental D, Fontana J, Maier P. Ransomware detection through behavioral attack signatures evaluation: a novel machine learning framework for improved accuracy and robustness; 2024. doi:10.36227/techrxiv.173092022.26611647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Deng X, Cen M, Jiang M, Lu M. Ransomware early detection using deep reinforcement learning on portable executable header. Clust Comput. 2024;27(2):1867–81. doi:10.1007/s10586-023-04043-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools