Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Homomorphic Encryption for Machine Learning Applications with CKKS Algorithms: A Survey of Developments and Applications

1 Key Laboratory of Information and Network Security, Engineering University of the PAP, Xi’an, 710086, China

2 Key Laboratory of CT&C, Engineering University of the PAP, Xi’an, 710086, China

3 Science and Technology on Communication Security Laboratory (CETC 30), Chengdu, 610041, China

* Corresponding Author: Xu An Wang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements and Challenges in Artificial Intelligence, Data Analysis and Big Data)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 89-119. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.064346

Received 12 February 2025; Accepted 03 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Due to the rapid advancement of information technology, data has emerged as the core resource driving decision-making and innovation across all industries. As the foundation of artificial intelligence, machine learning(ML) has expanded its applications into intelligent recommendation systems, autonomous driving, medical diagnosis, and financial risk assessment. However, it relies on massive datasets, which contain sensitive personal information. Consequently, Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning (PPML) has become a critical research direction. To address the challenges of efficiency and accuracy in encrypted data computation within PPML, Homomorphic Encryption (HE) technology is a crucial solution, owing to its capability to facilitate computations on encrypted data. However, the integration of machine learning and homomorphic encryption technologies faces multiple challenges. Against this backdrop, this paper reviews homomorphic encryption technologies, with a focus on the advantages of the Cheon-Kim-Kim-Song (CKKS) algorithm in supporting approximate floating-point computations. This paper reviews the development of three machine learning techniques: K-nearest neighbors (KNN), K-means clustering, and face recognition-in integration with homomorphic encryption. It proposes feasible schemes for typical scenarios, summarizes limitations and future optimization directions. Additionally, it presents a systematic exploration of the integration of homomorphic encryption and machine learning from the essence of the technology, application implementation, performance trade-offs, technological convergence and future pathways to advance technological development.Keywords

With the rapid development of information technology, we find ourselves in an era where data is the new currency, powering decisions and innovations across industries [1]. Machine learning, as the cornerstone of artificial intelligence, has emerged as a pivotal technology for data processing, enabling machines to learn from data and make intelligent predictions or decisions [2]. From intelligent recommendation systems that personalize our online experiences to self-driving cars navigating complex traffic scenarios, from accurate medical diagnoses vast patient records to sophisticated financial risk assessments global economies, machine learning applications are omnipresent, revolutionizing the way we live and work [3].

However, the widespread adoption of machine learning technology has brought to the forefront a critical concern: privacy protection [4,5]. The training and optimization of machine learning models typically demand substantial amounts of data, which have become the “private property” of various data operators [6]. This data often contains sensitive personal information, such as identification numbers [7], cell phone numbers [8], home addresses, and even biometric data like facial features. In recent years, a series of high-profile user privacy leakage incidents have shaken public trust, highlighting the urgent need to address privacy protection in the context of machine learning [9]. As a result, there is an increasing emphasis on developing methods that can protect personal data while still allowing the seamless operation of machine learning applications, giving rise to the field of Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning (PPML) [10].

PPML has become an essential area of research and development [11,12]. A crucial question in this field is how to enable encrypted data computation in machine learning models while maintaining efficiency and accuracy. One of the key technologies that enable PPML is Homomorphic Encryption (HE). HE is a revolutionary cryptographic technique that allows computations to be performed on encrypted data without decrypting it first [13,14]. In other words, with HE, data can remain encrypted throughout the entire machine learning process, from data collection and storage to model training and prediction. This ensures that even if the data is accessed by unauthorized parties, they cannot obtain any meaningful information from. However, the integration of machine learning and homomorphic encryption faces significant challenges [15,16]. First, encrypted computation leads to a substantial decline in model training and inference efficiency, for instance, training that originally took hours may extend to days [17,18]. Second, noise during encryption reduces model accuracy [19].

Meanwhile, the traditional cloud computing architecture faces significant bottlenecks in handling real-time sensitive privacy computing tasks [20]. All data must be uploaded to the cloud for encryption, leading to second-level delays in scenarios such as medical diagnosis and autonomous driving. As a distributed computing model of edge-cloud collaboration, the fog computing framework deploys intelligent fog nodes at the network edge, sinking data storage and partial encrypted computations to the vicinity of data sources [21,22]. This can reduce communication latency and provide a new optimization dimension for the integration of homomorphic encryption and machine learning. In 2017, Cheon et al. [23] proposed the Cheon-Kim-Kim-Song (CKKS) homomorphic encryption scheme based on the error learning problem. CKKS bridges the gap between homomorphic encryption and machine learning by combining algebraic optimizations for efficiency and systematic noise management for accuracy [24]. This scheme has important practical applications due to its ability to encrypt floating-point numbers as well as its excellent computational efficiency, thus making it possible to do data analytics, machine learning, and other security applications based on this in the ciphertext domain.

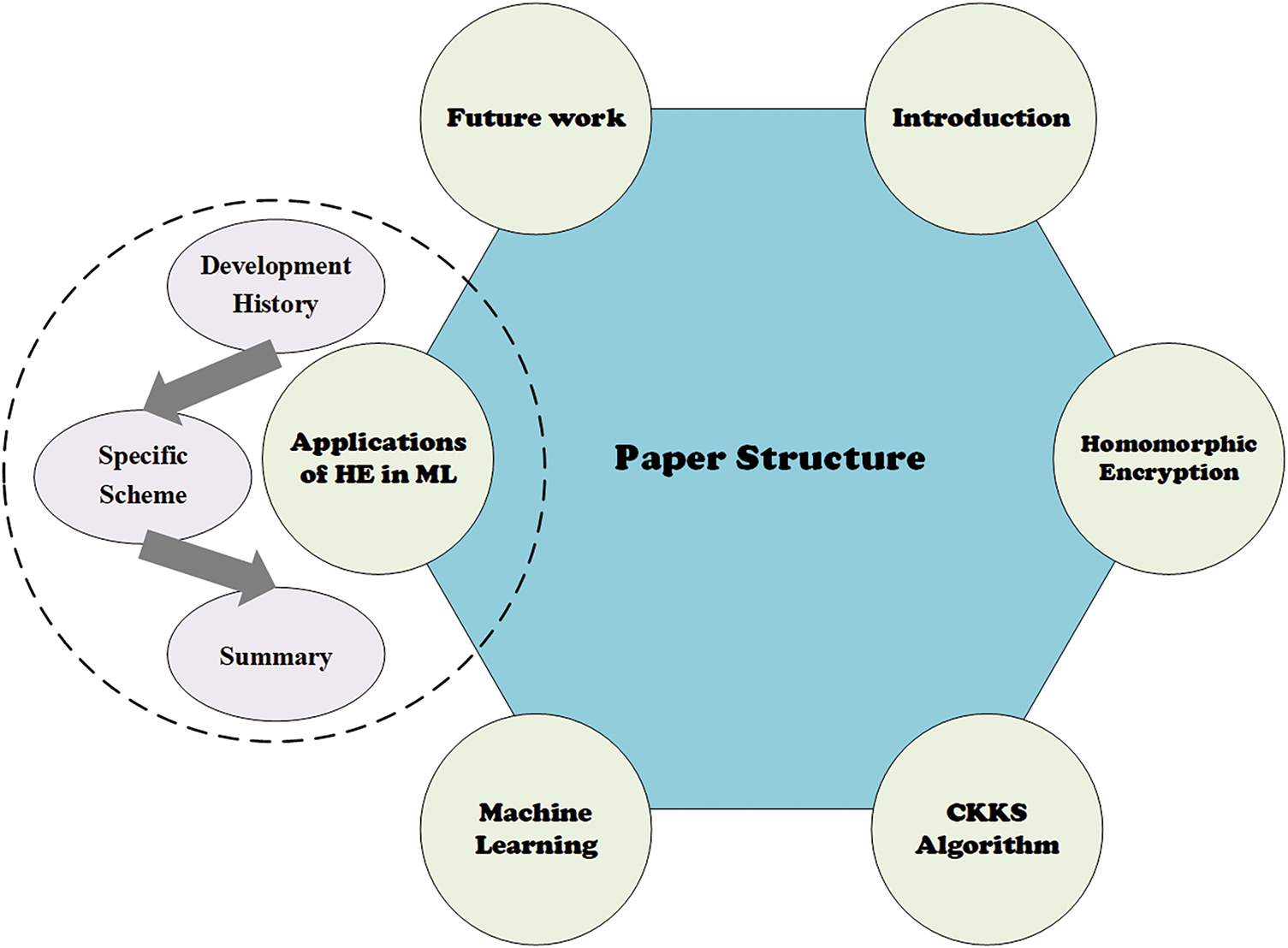

In terms of the overall framework, it follows the research approach of “basic theory-core technology-application scenarios-challenges and prospects”. Section 2 systematically introduces the general knowledge of HE, including its development history, classification methods and basic operation models, which lays a foundation for the in-depth understanding of the CKKS scheme in the follow up. Section 3 focuses on the mathematical principles and ciphertext structure design of CKKS based on ring homomorphism mapping, which is an analysis of the core technology. Sections 4 and 5 place CKKS in specific ML algorithm scenarios. According to the progressive logic of “development history-specific scheme-summary”, they gradually show how the technology is put into application and the actual effects. Fig. 1 shows the paper structure.

Figure 1: Paper structure

Specifically, our contributions are as follows:

• This paper combs the historical context of homomorphic encryption technology, dividing it into three stages: early exploration stage, theoretical breakthrough stage, and efficiency optimization stage. The CKKS algorithm is introduced with its advantages highlighted.

• This paper reviews the development history of the integration of three machine learning technologies, KNN, K-means, and face recognition, with homomorphic encryption. By proposing feasible specific schemes in typical scenarios, it summarizes their existing deficiencies and the next optimization directions.

• This paper presents a systematic exploration of the integration of homomorphic encryption and machine learning from the essence of the technology, application implementation, performance trade-offs, technological convergence and future pathways to advance technological development.

The term “homomorphic” originates from abstract algebra [25]. In algebra, homomorphism refers to the property where the mapping relationship between two algebraic structures remains unchanged. This concept has been extended to cryptography, becoming an encryption method that allows certain computable functions to be performed on encrypted data, while preserving the functional and format characteristics of the encrypted data. This enables the results of operations performed on encrypted data to be the same as those obtained after decrypting the data.

Homomorphic encryption (HE) is an encryption scheme that allows a third party, such as a cloud service provider [26], to perform certain computable functions on encrypted data, while maintaining the functional and format characteristics of the encrypted data [27]. It enables the results of various operations performed on encrypted data to be the same as those obtained after the data is decrypted.

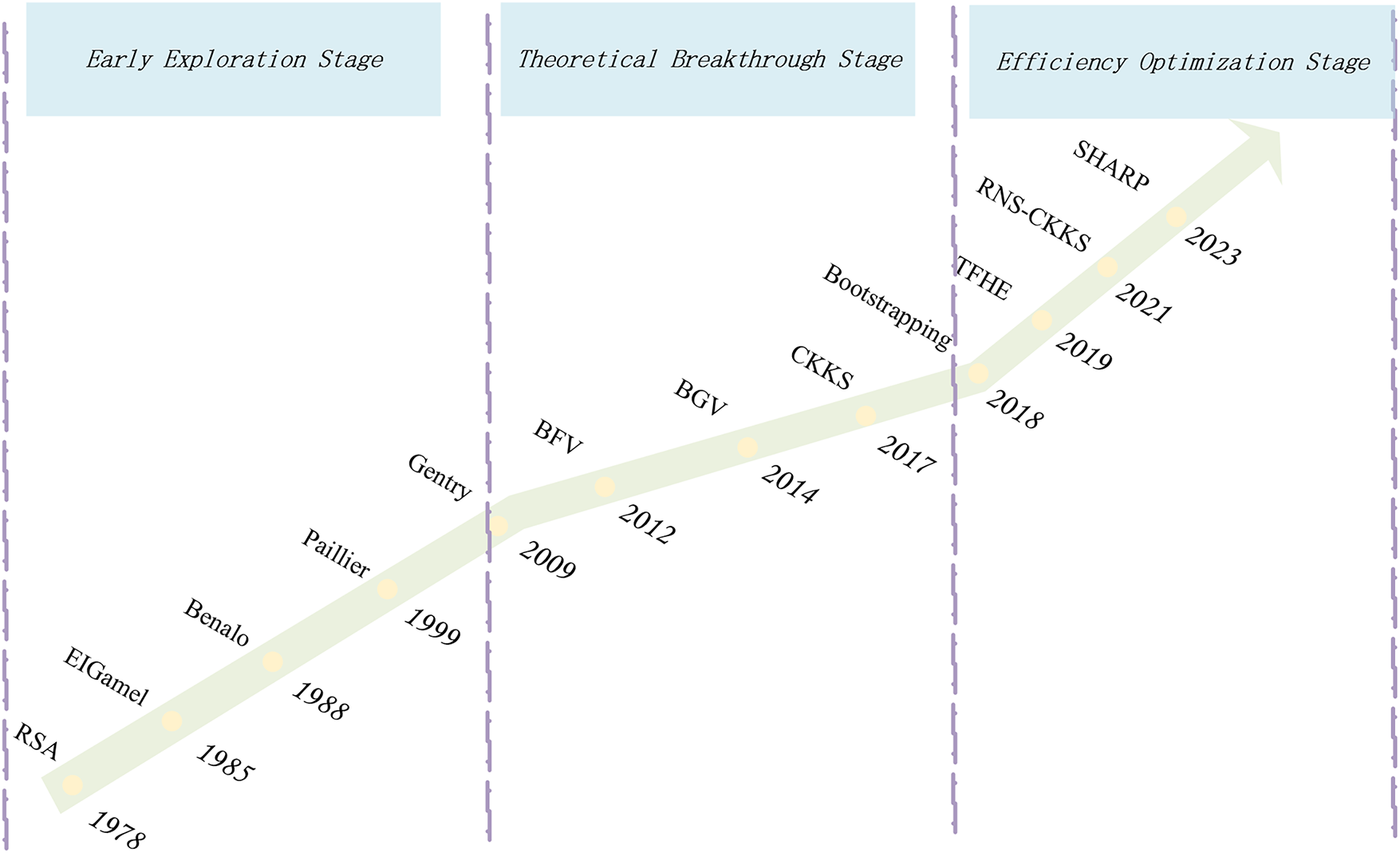

Homomorphic encryption (HE) has evolved through three distinct phases.

Early Exploration Stage. This stage laid the theoretical foundation for partial homomorphic encryption (PHE), demonstrated the feasibility of homomorphic encryption and addressed basic privacy computing needs. In 1978 three cryptographers, Ronald Rivest, Leonard Adleman and Michael Derouzons proposed the concept of homomorphic encryption. It allows data to be operated on directly in its encrypted form, with the results being the same as those obtained from the plaintext after decryption. The RSA algorithm [28] and the ElGamal algorithm [29], proposed in 1978 and 1985, respectively, support homomorphic operations on encrypted data for multiplication, but lacking support for complex ML operations like feature scaling or distance metrics.. The Benaloh algorithm [30] and the Paillier algorithm [31] both support homomorphic operations on encrypted data for addition. These partial HE (PHE) schemes supported only single operations, making them unsuitable for ML workflows involving iterative or mixed arithmetic.

Theoretical Breakthrough Stage. In this stage, fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) was achieved and adapted to machine learning (ML), enabling ciphertext computations for arbitrary operations and addressing ML’s requirements for complex calculations. Then in 2009, Dijk and Gentry [32] proposed a fully homomorphic encryption scheme based on the GCD problem, converting the original scheme based on ideal lattices into an integer-based SWHE, but with no significant improvement in efficiency. In 2012, Brakerski [33,34] proposed the BFV scheme, which supports homomorphic addition and multiplication, and theoretically can construct any arithmetic circuit. In 2014, Brakerski et al. proposed the famous BGV scheme [35] based on the LWE problem, using modulus switching technology to reduce the dimension of ciphertexts, significantly improving computational efficiency. In 2017, Cheon et al. [23] proposed the CKKS homomorphic encryption scheme, which is also a fully homomorphic encryption scheme, and its support for approximate number calculations makes it more feasible than other homomorphic encryption algorithms. CKKS bridged the gap between HE and ML by natively supporting continuous data types, making it the first practical choice for privacy-preserving classification and clustering.

Efficiency Optimization Stage. The final stage is dedicated to enhancing HE computation efficiency, expanding its application to large-scale data and complex ML models, and addressing performance bottlenecks in practical applications. In 2018, Cheon et al. [36] proposed Bootstrapping technology for approximate homomorphic encryption, improving the efficiency and practicality of homomorphic encryption. In 2019, Chillotti et al. [37] proposed the TFHE (Fast Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Torus) library, which significantly increased the speed of homomorphic encryption operations. In 2021, Lee et al. [38] proposed a high-precision bootstrap method for RNS-CKKS homomorphic encryption, which improves the computational accuracy by optimizing the polynomial approximation and inverse trigonometric functions. Bonte et al. proposed the FINAL scheme [39], which optimizes the computational efficiency of the homomorphic encryption based on the fast full homomorphic encryption scheme with NTRU and LWE.

In 2023, Kim et al. [40] proposed the SHARP scheme, an FHE accelerator that uses an efficient hierarchical microarchitecture with novel data organization and specialized functional units, significantly reducing the on-chip memory capacity requirements through architectural and software enhancements. In 2024, Hu et al. [41] proposed a faster matrix approximate homomorphic encryption method. By optimizing the encoding method and homomorphic operation of matrix operations, the efficiency of homomorphic encryption in processing matrix operations is improved. Lee and Shin [42] proposed a new floating point fully homomorphic encryption scheme that is able to detect the overflow of encrypted data during homomorphic computation, thus introducing an overflow detection mechanism. In 2025, Aguilar-Melchor et al. [43] proposed a secret key encryption scheme based on random rank metric ideal linear coding and a simple decryption circuit, which is the first homomorphic encryption scheme based on random ideal codes. Fig. 2 illustrates the development of homomorphic encryption.

Figure 2: Development of homomorphic encryption

HE schemes primarily involve four operations [44]: key generation, encryption, decryption, and evaluation. Key generation is for generating secret and public key pairs in the asymmetric version or a single key in the symmetric version. Encryption and decryption are similar to the classic tasks in traditional encryption schemes. However, evaluation is a specific operation of HE, which takes ciphertext as input and outputs a ciphertext corresponding to the function of the plaintext. The evaluation operation is crucial in homomorphic encryption, as it must preserve the format of the ciphertext after the evaluation process to ensure correct decryption. Additionally, the size of the ciphertext should be constant to support an unlimited number of operations. Otherwise, the increase in ciphertext size would require more resources, limiting the number of operations. Specifically:

1. Key Generation Algorithm:

2. Encryption:

3. Decryption:

4. Evaluation:

2.3 Classification of Homomorphic Encryption Algorithms

1. Partial Homomorphic Encryption (PHE)

Algorithms that satisfy limited homomorphic properties but not arbitrary homomorphic properties. Examples include RSA [28], ElGamal [29], and Rabin. Multiplicative homomorphic encryption algorithms: RSA [28], ElGamal [29]; Additive homomorphic encryption algorithms: Paillier [31].

2. Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption (SWHE)

Can support additive and multiplicative homomorphic operations, but the number of operations is limited. For example, the Boneh-Goh-Nissim scheme [45].

3. Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE)

Supports any operation with no limit on the number of operations. FHE can perform any operation on encrypted data without any limit on the number of operations. One branch focuses on computing arithmetic circuits (BFV, BGV, CKKS), based on the hierarchical homomorphic encryption (LHE) of RLWE, while another focuses on computing Boolean circuits (FHEW, TFHE), based on efficient bootstrapping technology.

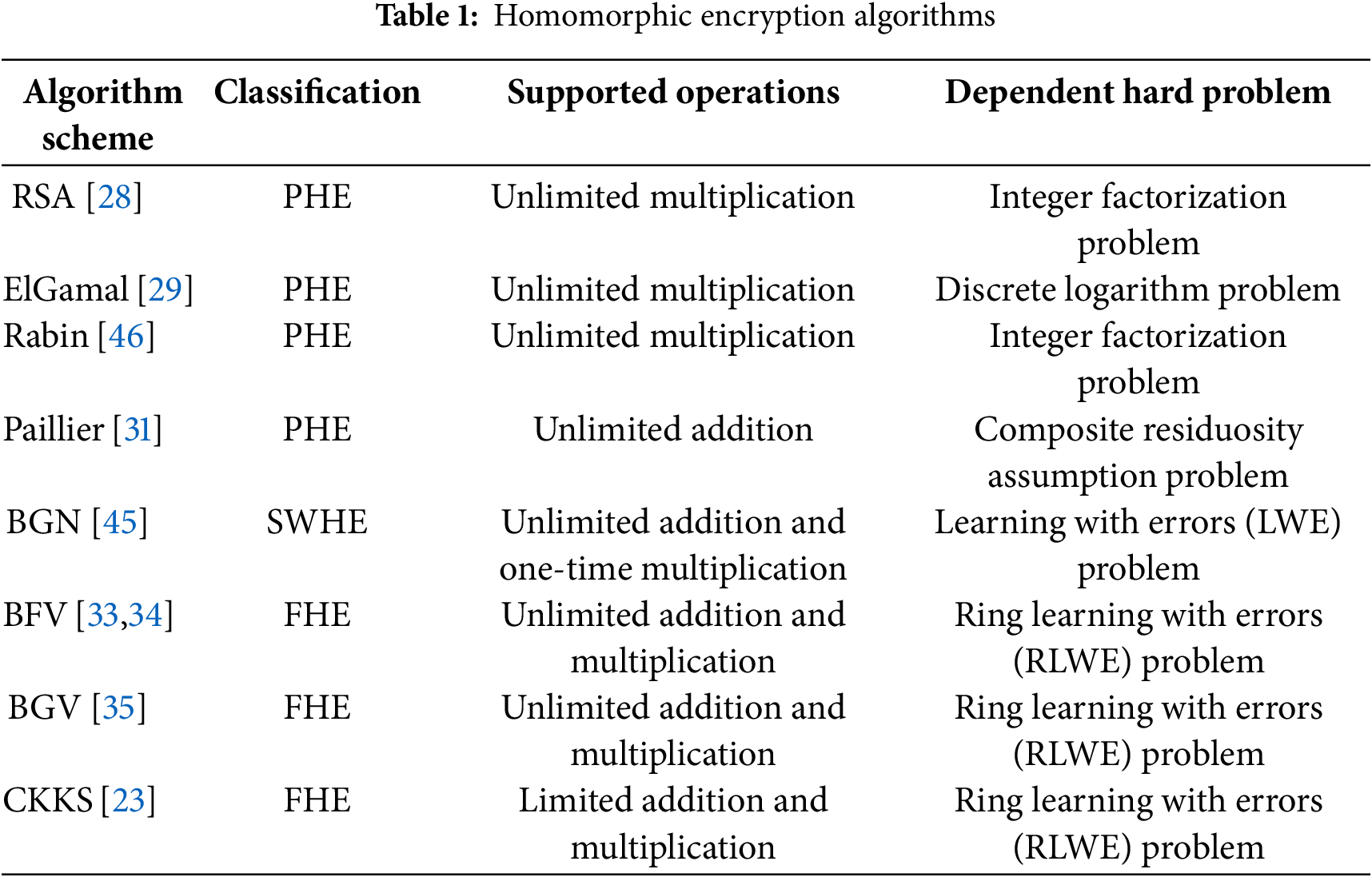

The classification of classical algorithms for homomorphic encryption, the supporting operations and the difficult problems they rely on are summarized in Table 1.

In Section 4, we will introduce three specific schemes that combine machine learning with homomorphic encryption technology. Thees schemes in this paper are designed based on the CKKS algorithm scheme. Cheon et al. [23] proposed a hierarchical FHE scheme that can support floating point approximation computation, which is divided into initialization, key generation, encoding, decoding, encryption, decryption, computation and rescaling. Firstly, the mathematical basis and ciphertext structure in CKKS scheme are introduced.

Mathematical foundations: For the homomorphic algorithm based on the RLWE puzzle, the plaintext space

Ciphertext structure: The CKKS ciphertext structure is designed based on the learning error (LWE) problem and polynomial rings in lattice cryptography [47]. Its ciphertext is usually in the form of a vector consisting of two polynomials, generally denoted as

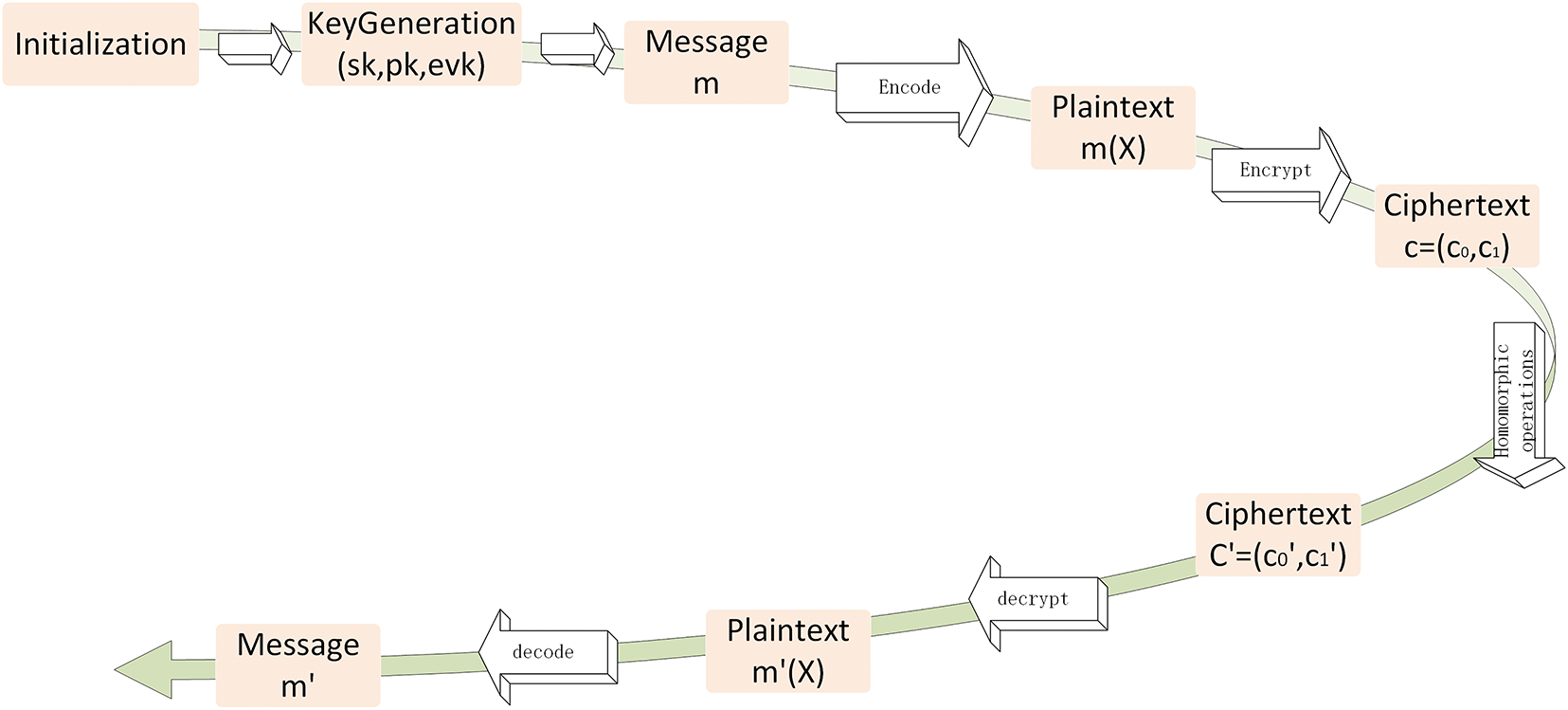

Brief description of the CKKS algorithm: We will present the CKKS algorithm in the form of a flowchart in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: CKKS algorithm

The CKKS algorithm is based on ring homomorphism. During initialization, it first determines security parameters, ring dimensions, moduli, and other fundamental frameworks, along with probability distributions. In key generation, private keys, public keys, and auxiliary computation keys are constructed to enable coordinated key management. Through encoding, plaintext in the form of complex vectors is mapped to ring elements, achieving the adaptation of continuous values to discrete rings. During encryption, ciphertext is generated by combining public keys and random noise, with noise injection ensuring security. In homomorphic operations, addition is realized via direct component-wise addition, while multiplication leverages auxiliary keys and is followed by rescaling to suppress noise growth; the rescaling operation reduces the ciphertext modulus to control noise. Decryption utilizes the linear relationship between private keys and ciphertext to extract plaintext in the form of ring representations. Finally, decoding restores the original complex vectors through inverse mapping, forming a “encrypted computation-decrypted restoration” closed loop, supporting approximate arithmetic operations and providing a solution for computations in encrypted scenarios.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Homomorphic addition:

homomorphic multiplication:

6.

Since the multiplication operation introduces an increase in noise, a rescaling operation is performed after each multiplication. Give the level-

7.

Let

8.

Machine learning is a multidisciplinary professional field [49] that covers knowledge of probability theory, statistics, approximation theory, and complex algorithms [50]. It uses computers as tools and is committed to real-time simulation of human learning methods [51]. It also divides existing content into knowledge structures to effectively improve learning efficiency.

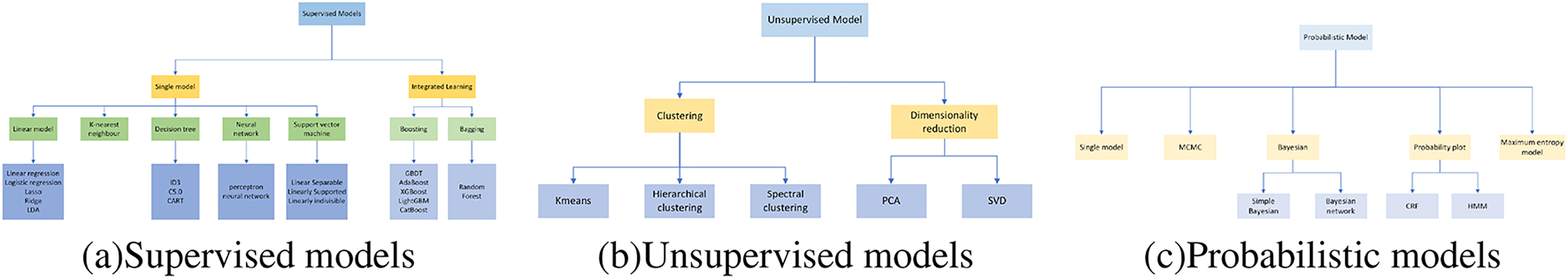

Machine-learning models can be divided into three categories: Machine learning models can be categorized into supervised (a) and unsupervised (b) models and are listed separately here as probabilistic (c) models [52]. Supervised models rely on labeled data to learn mapping relationships, while unsupervised models mine the intrinsic structure of unlabeled data, as illustrated in Fig. 4. In practice, the data labeling situation is often the primary consideration for model selection, and corresponding models are used for different situations. The following describes the basic concepts of machine learning techniques used in the scheme of this paper.

Figure 4: Classification of machine learning models

4.1 Machine Learning Based on Homomorphic Encryption

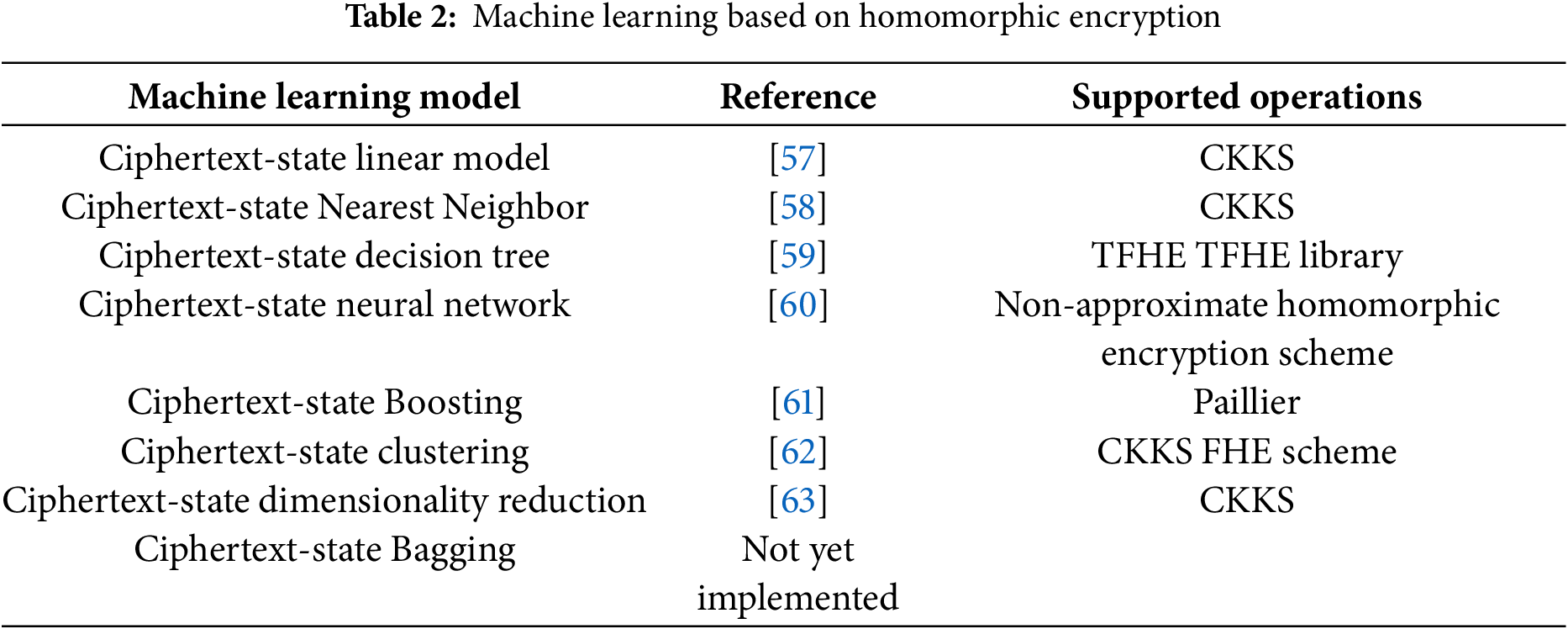

As fully homomorphic encryption technology gradually matures, the application of fully homomorphic encryption has become the focus of attention for researchers. At the same time, there are also many studies on using machine learning algorithms including neural networks to make predictions on homomorphi-encrypted data [53,54]. However, compared with training models, using models for prediction has a much simpler computational amount. As the combination of homomorphic encryption and machine learning related fields gradually matures, many studies have started to train models on encrypted data [55,56]. Nevertheless, because the operations that can be performed on ciphertext data are limited, in statistical analysis, people have to use some iterative algorithms to replace some steps in traditional calculation models. And due to the limitations of the ciphertext space, how to perform large-scale iterative operations while ensuring computational efficiency and accuracy is a thorny problem. Table 2 shows some examples of homomorphic encryption combined with machine learning.

5 Applications of Homomorphic Encryption in Machine Learning Algorithms

The integration of machine learning and homomorphic encryption is a key direction in information security. Since the homomorphic encryption concept emerged in the 1970s and began fusing with machine learning in the early 21st century, it has gone through theoretical, practical and improvement stages. Fully homomorphic encryption breakthroughs have accelerated research, but issues like high encryption cost, slow training and poor algorithm adaptability remain.

This section will respectively sort out the development history of the integration of KNN, K-means, face recognition technology with homomorphic encryption. By designing specific schemes and revealing technical bottlenecks through experiments, we will revisit the historical unresolved problems.

5.1 Secure KNN Classification Scheme Based on Homomorphic Encryption

Development History. In 1968, Cover and Hart proposed the KNN algorithm [64]. This algorithm is one of the classic machine-learning algorithms. Due to its simple algorithm structure and remarkable classification performance, it can be well applied in data mining and statistical fields. Thus, it was rated as one of the top ten data-mining algorithms and is widely used in many fields such as classification, regression, and missing-value imputation.

Traditional KNN classification schemes mainly include two types [65,66]. One is to assign the optimal

To protect the security of users’ private data, researchers have also conducted a large amount of research on KNN classification on ciphertexts. In 2017, Li et al. [69] proposed two secure and efficient dynamic searchable symmetric encryption (SEDSSE) schemes for medical cloud data. By constructing a dynamic searchable symmetric encryption scheme through a secure KNN scheme and ABE technology, it realizes forward and backward privacy security at the same time, and also proposes an enhanced scheme to effectively solve the key-sharing problem brought about by using KNN to achieve search encryption. In 2020, Parvin et al. [70] developed an electronic medical record analysis system on the blockchain based on the KNN and LDA algorithms, which is used for the automatic and secure sharing of medical data sets among medical experts. Zheng et al. [71] proposed an efficient privacy-preserving inverse kNN query scheme for high-dimensional data (PHRkNN). The scheme indexes the data by an improved M-tree (MM-tree) and designs the encryption scheme for the filtering and refining phases in combination with lightweight matrix encryption. In 2024, Behera and Prathuri [72] proposed an FPGA based hardware accelerator for performing the K-Nearest Neighbor classification in machine learning on mobile devices. Liu and Xing [73] proposed an encrypted data inner product kNN secure query scheme based on BALL-PB tree. The scheme indexes the data through BALL-PB tree and utilizes encryption to protect the query and data privacy.

By connecting key studies from 2020 to 2024, this passage reveals the distributed evolution path of homomorphic encryption (HE) in secure KNN classification, from technical breakthroughs (Vector Homomorphic Encryption [74], multi-key protocols [75]) to challenges (computational complexity [76]) and then to optimizations (stochastic evaluation [75], multi-party collaboration [77]). It ultimately demonstrates how HE has propelled KNN from theoretical privacy protection to practical distributed application scenarios. In 2020, in order to classify large scale ciphertext data in distributed servers, Yang et al. [74] designed a vector homomorphic encryption (VHE) scheme by constructing key-switching matrices and noise matrices, and based on this, constructed a secure distributed KNN classification algorithm (SEEDkNN). However, this algorithm requires efficient data transmission and processing between IoT devices and cloud servers. In 2022, Ameur et al. [76] proposed a non-interactive kNN classifier scheme based on symmetric full homomorphic encryption by utilizing symmetric full homomorphic encryption, but the computational complexity of full homomorphic encryption is high, which will affect the system efficiency. In 2024, Petrean and Potolea [75]proposed a stochastic kNN evaluation scheme based on multi-key homomorphic encryption. But The scheme also has high computational complexity, significant implementation complexity, and limited applicability. In 2023, Wang et al. [77] proposed an outsourced privacy-preserving kNN classifier model based on multi-key homomorphic encryption (kNNCM-MKHE). The scheme supports collaborative evaluation of kNN classifiers by multiple model owners through the multi-key Brakerski-Gentry-Vaikuntanathan (BGV) protocol. Model owners upload encrypted models to a third-party evaluator, who completes the classification task without decrypting them and returns the results securely to the user, ensuring data and model privacy, but communication overhead can be high due to the need to transfer encrypted data between multiple participants.

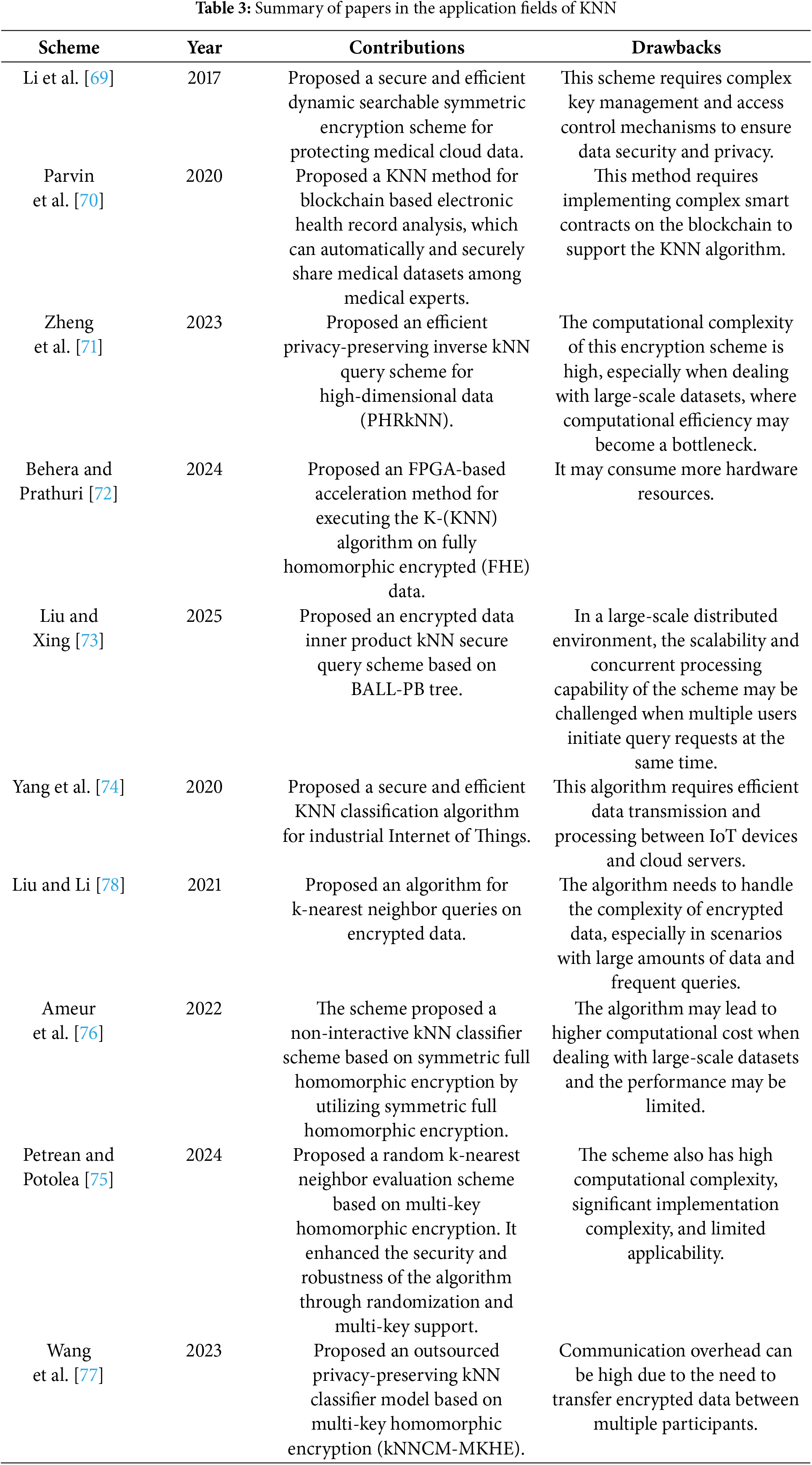

In general, in the integration of KNN with homomorphic encryption (HE) and machine learning, key inadequacies include: early privacy-computation conflicts in plaintext KNN and partial HE; high FHE complexity, floating-point errors, and noise-limited depth; heavy distributed communication overhead, static data inflexibility; cross-domain multi-key complexity with privacy-accuracy trade-offs; edge device latency and high framework integration costs. As shown in Table 3, a comprehensive analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of KNN combined with homomorphic encryption in this article is provided.

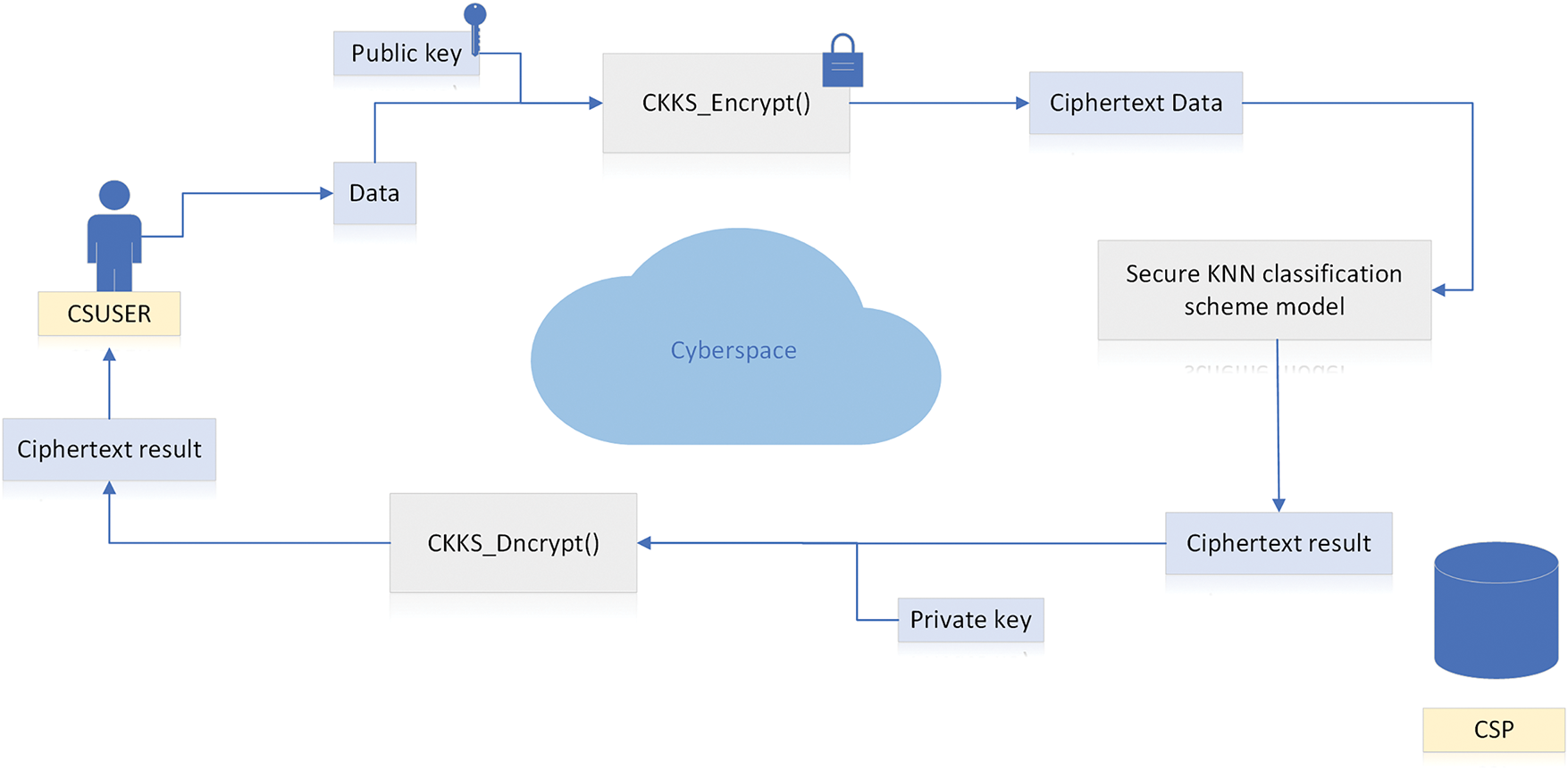

Specific Scheme. This section [58] introduces a secure KNN classification scheme based on the CKKS homomorphic encryption scheme. In Liu’s paper, the scheme achieves floating-point ciphertext computation via ring homomorphic mapping, demonstrating 97% classification accuracy on the IRIS dataset with a 3-fold efficiency improvement over Paillier. By optimizing matrix transposition and batch inner products, it reduces the classification time for 1000 samples from 280 to 145 ms while cutting memory usage by 60%. The semi-trusted user-cloud model ensures data privacy through CKKS semantic security, addressing the bottlenecks of traditional HE in KNN’s floating-point processing and distributed efficiency. The model of the secure KNN classification scheme consists of two parts: the user (USER) and the cloud service provider (CSP). The CSP can provide remote storage and computing services for the USER. The USER has a large amount of local data and enjoys the services provided by the CSP. The specific solution is shown in Fig. 5. The division of labor of each part is as follows:

1. User (USER): Generates public and secret keys locally, encrypts data and uploads it to the CSP, and decrypts the ciphertext calculation results.

2. Cloud Service Provider (CSP): Provides remote storage and computing services for the USER. It has strong storage and computing capabilities, is responsible for storing the ciphertext data uploaded by the USER, calculating the similarity between the encrypted sample to be classified and other ciphertext samples, and returning the ciphertext results to the USER.

Figure 5: Secure KNN classification scheme model

First, the USER generates public and secret keys locally, encrypts the locally known-category samples and sends them to the CSP. The CSP receives and stores these ciphertext samples. When the USER receives a new sample to be classified, it encrypts the sample locally and sends it to the CSP. The CSP receives it, calculates the similarity between the encrypted sample to be classified and other ciphertext samples in the server, and then sends the ciphertext calculation results to the USER. The USER receives and decrypts the ciphertext calculation results returned by the CSP, selects the

The algorithm of this scheme is divided into two stages: data initialization and classification. The specific operation steps are as follows:

1. Data Initialization:

(a) First, the USER standardizes the characteristic indicators of the local data samples. Calculate

(b) The USER generates public and secret keys

2. Classification:

(a) After receiving a new sample

(b) After receiving the query matrix, the CSP calculates the similarity

(c) The CSUSER decrypts

3. Security Similarity Calculation Method: This scheme uses Euclidean distance, Pearson correlation coefficient and cosine similarity to measure the similarity between samples.

(a) Euclidean distance: Euclidean distance is the most common similarity measure, which is widely used in various scenarios such as k-Means clustering algorithms and face recognition. The traditional method of calculating Euclidean distance is to directly calculate the absolute distance between points in a multidimensional space, and also to calculate the Euclidean distance between samples by matrix inner product. The two methods of calculating Euclidean distance are described below, respectively.

Method 1: Since the ciphertext encrypted through CKKS homomorphic encryption algorithm cannot be directly subjected to open-square operation, the distance is not subjected to open-square operation here, and the ciphertext distance between the samples to be categorized and the samples of known categories is expressed as follows. The smaller the distance, the higher the similarity between the two samples.

Method 2: Before uploading the data, USER computes

(b) Pearson correlation coefficient: The effect of the magnitude of the different adjustment metrics on the Euclidean distance is relatively large due to the sample. Therefore, in some applications, people often choose Pearson’s correlation coefficient, which is not sensitive to the magnitude, to measure the similarity between samples.

(c) Clip angle cosine: Clip angle cosine is similar to Pearson’s correlation coefficient. It measures similarity by calculating the cosine of the angle between two samples in vector space, so the method focuses more on the difference between two vectors in terms of direction rather than distance metrics.

Similarly, since CKKS ciphertexts cannot directly perform open-square operations, the cosine similarity calculation process in the protocol is as follows: Since CKKS ciphertexts cannot directly perform division operations in terms of practical implementation. So the CSP will actually return the values

Summary. In the integration of KNN with homomorphic encryption and machine learning, key challenges include early privacy-computation conflicts in plaintext KNN with partial HE, high FHE complexity, floating-point errors, noise-limited model depth, heavy distributed communication overhead, static data inflexibility, cross-domain multi-key complexity with privacy-accuracy trade-offs, and edge device latency with insufficient hardware acceleration.

Liu’s scheme [58] addresses these via ring homomorphic mapping for floating-point ciphertext computation, optimizing matrix operations to enhance efficiency. Leveraging CKKS semantic security in a semi-trusted model, it resolves traditional HE bottlenecks in KNN’s floating-point processing. However, critical gaps remain: inadequate dynamic data adaptation, limited deep complex model support, lack of multi-institutional solutions, and suboptimal edge device hardware acceleration.

However, traditional schemes still face efficiency bottlenecks in fog computing environments: their static offloading mechanisms centralize all encrypted computations in the cloud [79]. In contrast, SLO-aware strategies achieve optimization through dynamic hierarchical scheduling [80], including upgraded decision logic and reconstructed computational resource allocation.

5.2 Secure K-Means Clustering Protocol Based on Homomorphic Encryption

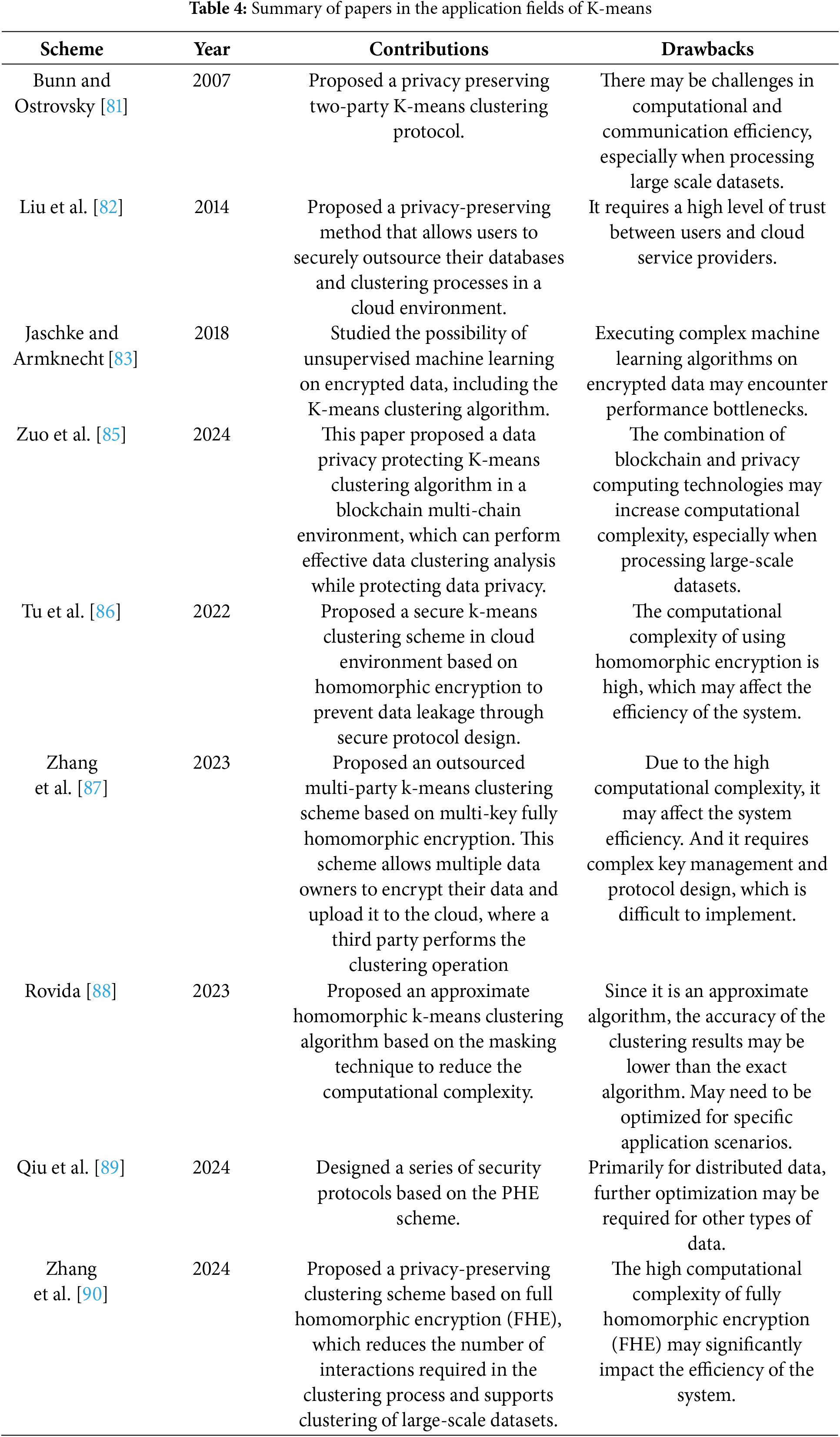

Development History. In 2007, Bunn and Ostrovsky [81] proposed a privacy-preserving two-party K-means clustering protocol based on the Paillier homomorphic encryption scheme. In 2014, Liu et al. [82] proposed a K-means clustering method based on the homomorphic encryption scheme. This method enables cloud service providers to compare encrypted distances with the trapdoor information provided by data owners, thus maintaining the distance order between data objects and cluster centers. In 2018, Jaschke and Armknecht [83] improved the K-means algorithm, enhancing its efficiency, and proposed a fully homomorphic encrypted K-means algorithm. This scheme uses natural encoding that allows division to solve the division operation problem. Although it theoretically addresses the challenge of division operations, the homomorphic operation efficiency is low. In addition, researchers have also designed some other secure clustering algorithms. In 2021, Jia et al. [84] proposed a privacy-preserving method for the DBSCAN clustering based on homomorphic encryption and designed a ciphertext comparison operation.

In 2022, Zuo et al. [85] proposed a privacy-preserving K-means clustering algorithm under blockchain multi-chains. By leveraging the concept of homomorphic encryption, it realizes K-means clustering under multi-chains, addresses potential collusion and eavesdropping attacks, and prevents data leakage. In 2022, Tu et al. [86] proposed a secure K-means clustering scheme in cloud environment based on homomorphic encryption to prevent data leakage through secure protocol design, but the computational complexity of using homomorphic encryption is high, which may affect the efficiency of the system. In 2023, Zhang et al. [87] proposed an outsourced multi-party k-means clustering scheme based on multi-key fully homomorphic encryption. This scheme allows multiple data owners to encrypt their data and upload it to the cloud, where a third party performs the clustering operation, but requires complex key management and protocol design. Rovida [88] proposes an approximate homomorphic k-means clustering algorithm based on the masking technique to reduce the computational complexity while maintaining a high level of privacy protection through the masking technique.

In 2024, Qiu et al. [89] designed a series of security protocols based on the PHE scheme, including the secure squared Euclidean distance protocol, the encrypted distance comparison protocol, and the key techniques for realizing privacy-preserving clustering. And zhang et al. [90] proposed a privacy-preserving clustering scheme based on full homomorphic encryption (FHE), which reduces the number of interactions required in the clustering process and supports clustering of large-scale datasets through the minimum value lookup and the minimum index computation of one-dimensional vectors. But the high computational complexity of fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) may significantly impact the efficiency of the system.

In general, the integration of K-means with HE has always faced a triangular trade-off among privacy protection, computational efficiency, and model accuracy: early partial HE schemes caused dual losses in efficiency and accuracy due to limited functionality; fully homomorphic solutions, though theoretically complete, suffer from excessively high computational complexity; communication overhead and key management challenges in distributed and dynamic scenarios further restrict practicality; while hardware adaptation issues and security vulnerabilities hinder technological implementation. Table 4 systematically elucidates the merits and demerits of integrating K-means with homomorphic encryption as presented in this article.

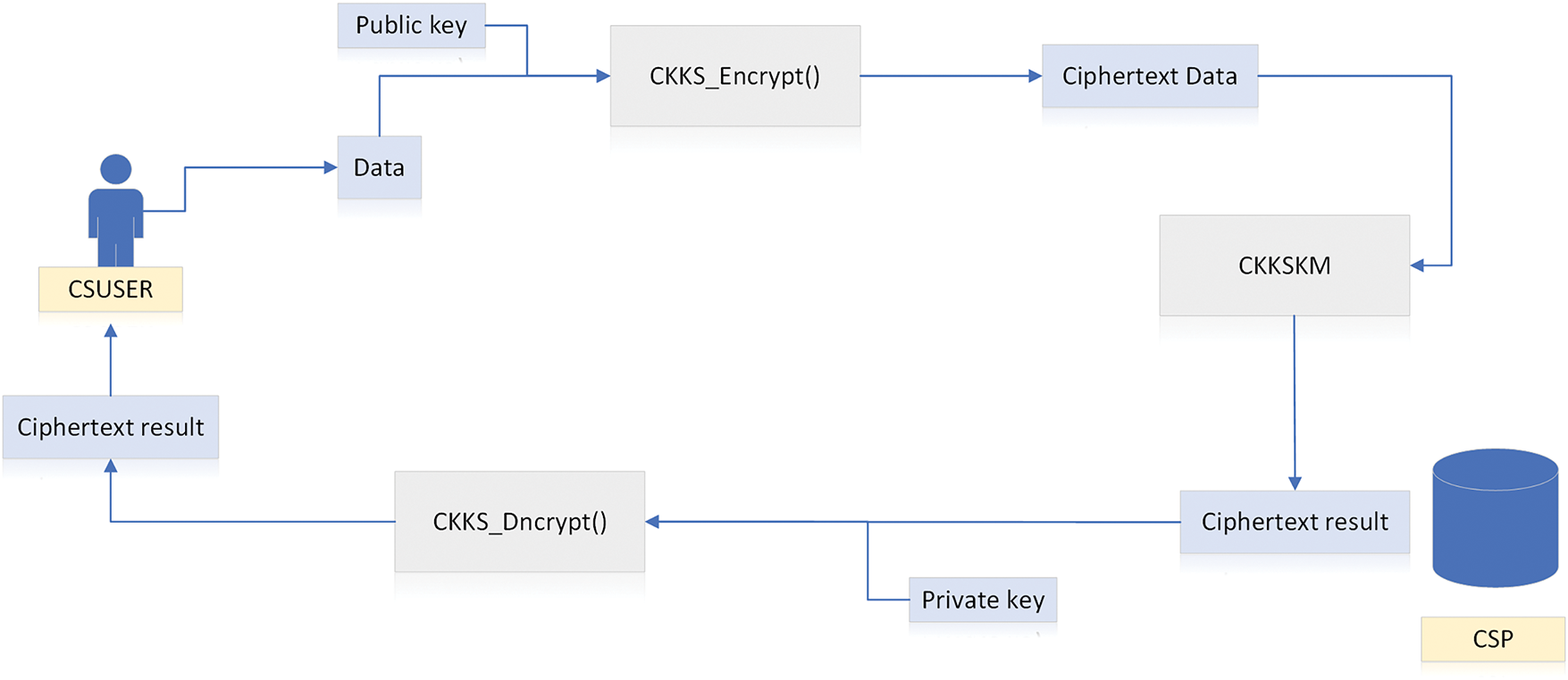

Specific Scheme. This section [86] introduces a secure K-means classification scheme based on the CKKS homomorphic encryption scheme named CKKSKM. This proposed solution shares a similar design philosophy with the approach presented in section [58], which integrates homomorphic encryption with the KNN algorithm. The primary distinction lies in the choice of machine learning algorithms employed. While the previous work in section leveraged the KNN algorithm, this solution utilizes a different algorithm, enabling a unique approach to data processing and model training under the framework of homomorphic encryption. Next, we will introduce the scheme, which mainly consists of two parties: the user (USER) and the cloud service provider (CSP).

1. User (USER): The user has a large amount of data. They generate public and secret keys locally, encrypt the outsourced data, and then outsource the data to the CSP in ciphertext form for storage and processing.

2. Cloud Service Provider (CSP): The CSP has massive storage space and powerful data processing capabilities. It can provide outsourced data storage and computing services for the USER, store the ciphertext data uploaded by the USER, and perform operations on the ciphertext data.

In the CKKSKM model, the CSP is semi-trusted and can provide remote storage and computing services for the USER. The USER has a large amount of data to process. After encrypting the data, it transmits the data to the cloud server in ciphertext form and utilizes the CSP for data storage and processing.

As shown in the Fig. 6, the specific interaction process is as follows. First, the USER generates a public secret key pair, encrypts the sample data to be classified, and sends the encrypted ciphertext to the CSP. After receiving the ciphertext data sent by the USER, the CSP stores the ciphertext data in the cloud server. When it is necessary to calculate the ciphertext data stored in the CSP, the USER selects the initial cluster centers locally according to requirements, encrypts them, and sends them to the CSP in ciphertext form. The CSP receives the ciphertext data, calculates the similarity between the ciphertext samples stored in the server and the ciphertext data of the uploaded cluster centers, and iteratively completes the K-means clustering. When the calculation result converges, the CSP sends the calculation result in ciphertext form to the USER. The USER receives the ciphertext calculation result returned by the CSP and decrypts it with the secret key to obtain the final clustering result.

Figure 6: CKKSKM model

The CKKSKM protocol can be divided into two stages: the data pre-processing stage and the sample clustering stage. The specific steps are as follows:

Data Pre-processing. Suppose the feature indicators of the known-category sample data uploaded by the user are

First, the USER detects outliers in the samples to be classified, and then calculates the average value of the

Summary. Generalky, in integrating K-means with homomorphic encryption, the triangular trade-off among privacy protection, computational efficiency, and model accuracy remains persistent. Early partial homomorphic encryption schemes lead to dual losses in efficiency and accuracy due to limited functionality, while fully homomorphic solutions suffer from excessively high computational complexity. Communication overhead and key management challenges in distributed and dynamic scenarios further restrict practicality, and hardware adaptation issues together with security vulnerabilities hinder technological implementation.

Tu’s scheme [86], based on CKKS homomorphic encryption, preprocesses data and employs Euclidean distance to calculate similarity, ensuring data accuracy while reducing computational overhead. It addresses privacy security issues and lowers user overhead when outsourcing data to the cloud for storage and computation. However, it still has limitations: lack of dynamic data adaptation, insufficient support for high-dimensional features in deep models, inadequate multi-institutional collaboration capabilities, poor edge device compatibility, post-quantum security vulnerabilities, and iterative noise accumulation, which restrict its application in real-time and complex scenarios.

5.3 Secure Face Recognition Scheme Based on Homomorphic Encryption

Development History. With the rapid development of deep learning and big data technologies, artificial intelligence has made significant breakthroughs [91], pushing face recognition accuracy to new heights [92]. Early face recognition relied on fixed algorithms like PCA and SIFT algorithm [93].

To address security issues such as user privacy leakage, researchers began to study face recognition in the ciphertext domain. In 2017, Ma et al. [94] implemented encrypted face recognition in a cloud environment based on the Paillier homomorphic encryption algorithm and DNN. However, due to the nature of the Paillier homomorphic encryption algorithm, complex calculations could not be performed. In 2020, Yang et al. [95] proposed a recognition scheme based on encrypted face images using the Krawtchouk matrix and the Paillier homomorphic encryption algorithm. However, the encryption efficiency needed to be improved, and the recognition accuracy on the ORL database only reached 87.22%. In 2021, Khan et al. [96] proposed a face recognition scheme in the encrypted domain. They encrypted data using the Paillier algorithm, extracted image features through RLTP (Radial Local Ternary Pattern), calculated the Euclidean distance in the ciphertext domain, and demonstrated the feasibility of the scheme through experiments. However, the recognition accuracy was lower than that of the original recognition scheme, and the computational cost was high. At present, most of the homomorphic encryption algorithms combined with face recognition are partial homomorphic encryption algorithms, and the available computational operations are very limited.

In 2022, Yang et al. [97] proposed a privacy preserving facial recognition system based on homomorphic encryption. The system protects the facial feature templates by homomorphic encryption to ensure the privacy of the data during the identity verification process. But it requires high quality pre-trained models to extract facial features, increasing system complexity. In 2024, Crihan et al. [98] conducted preliminary experiments on real-world authentication mechanisms based on facial recognition and full homomorphic encryption. The study experimentally verifies the feasibility of full homomorphic encryption for facial recognition and suggests optimizations. Ahmad Jalali and Chen [99] proposed a federated learning framework combining blockchain and fully homomorphic encryption for chatbot security system. The framework protects data privacy through cryptography while ensuring data immutability using blockchain technology. In 2025, Serengil and Ozpinar [100] proposed a cloud facial recognition framework (CipherFace) based on fully homomorphic encryption that allows facial recognition on encrypted data. Ensuring the privacy of data during transmission and processing, this leverages cloud resources for computation and reduces the local computational burden. Song et al. [101] proposed a face recognition framework based on approximate homomorphic encryption HE_FaceNet, which aims to effectively mitigate privacy leakage during face recognition and accelerate the facial recognition process by combining with clustering algorithms. Wang et al. [102] presented a more efficient and secure PUM (Privacy preserving security Using Multi-key homomorphic encryption) mechanism for facial recognition. The scheme allows multiple users to encrypt data and upload it to the cloud, where a third party performs clustering operations while protecting data privacy.

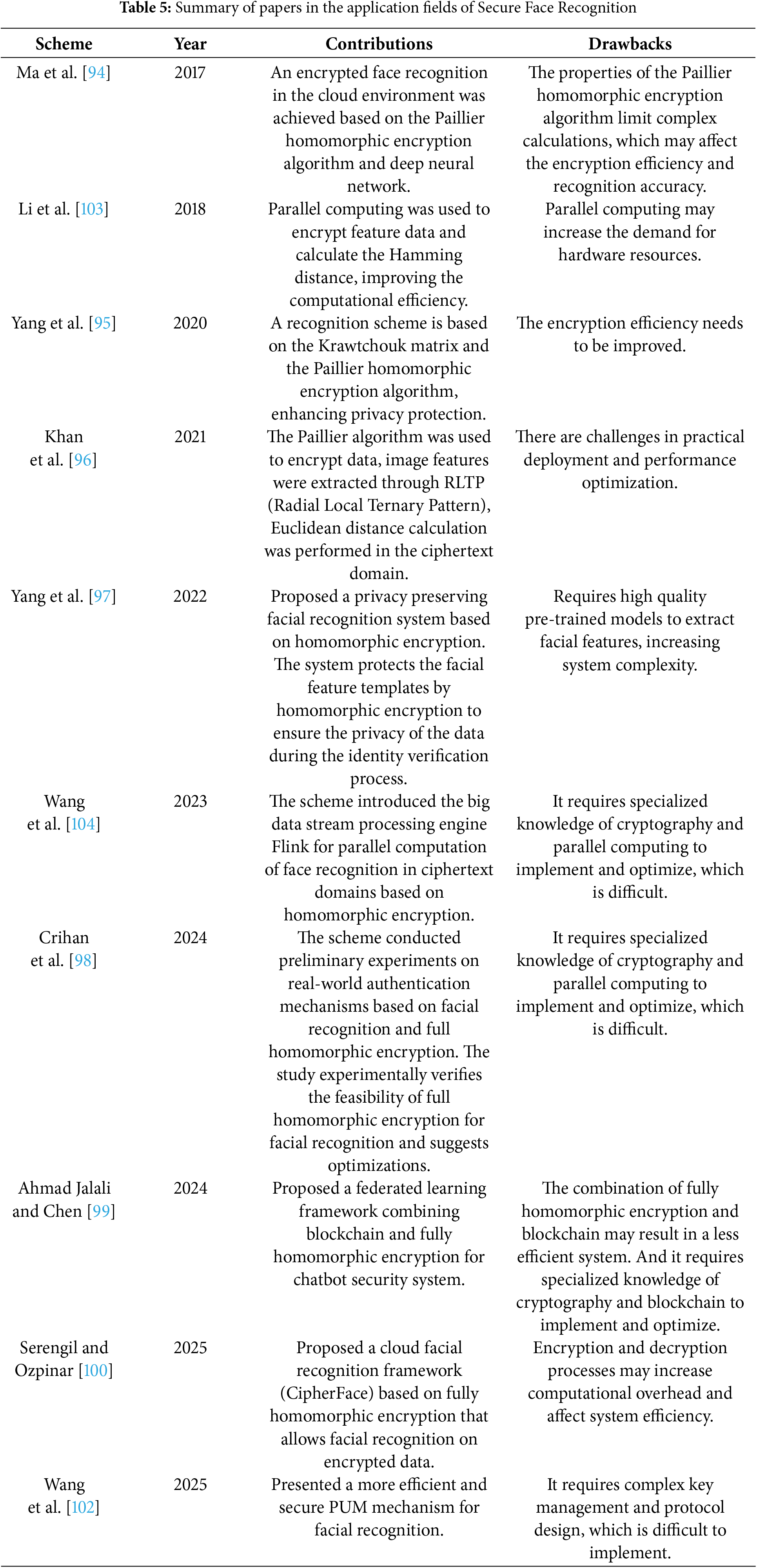

In brief, in the integrated development of face recognition technology and homomorphic encryption, many severe challenges are faced. Currently, partial homomorphic encryption is dominant, but its limited computing capability leads to low encryption efficiency and high computational costs. Although fully homomorphic encryption is theoretically complete, its extremely high computational complexity and slow dynamic data update make it difficult to meet real-time requirements. In distributed scenarios, the collaborative communication overhead of multiple keys increases dramatically, and it is difficult to balance privacy protection and model accuracy, resulting in a 5% decrease in accuracy. How to balance data privacy protection, computational efficiency, and recognition accuracy remains a core problem to be solved urgently. As shown in Table 5, a comprehensive analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of homomorphic encryption for secure face recognition scenarios is provided.

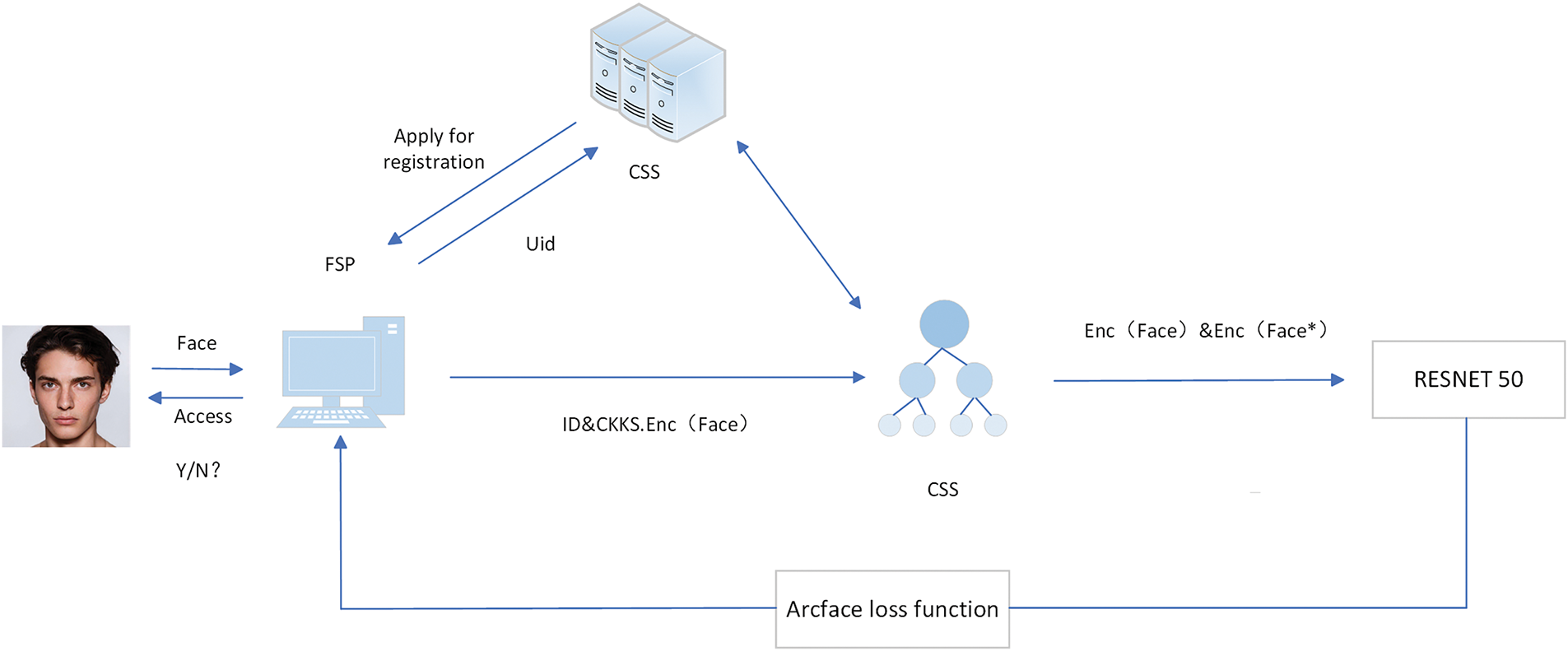

Specific Scheme. This article [105] introduces a secure face recognition scheme based on homomorphic encryption. The system model consists of three parts: the Front-End Service Platform (FSP), the Cloud Storage Server (CSS), and the Cloud Computing Server (CCS). Both CSS and CCS are services provided by the cloud platform and are “honest but curious”. The division of labor for each part is as follows in Fig. 7:

1. Front-End Service Platform (FSP): The Front-End Service Platform is mainly responsible for recognizing the user’s face, reading the user’s identity identification information (

2. Cloud Storage Server (CSS): It provides storage services for users, has sufficient storage space to store the image information uploaded by users, and returns the identity identifier

3. Cloud Computing Server (CCS): It is the most important part of the entire model. It provides computing services, is responsible for extracting image features, and returns them to the FSP for calculating vector correlations.

Figure 7: Secure face recognition programme model

When a new user registers, the FSP first uploads the recognized face and the user ID to the CCS. Then, the CCS stores the encrypted image and the user ID in the CSS, generates a unique identity identifier

During face recognition, FSP identifies the user’s

User first applies for registration to the CSS, sets a threshold

The CSS transmits the encrypted image

The CSS generates an identity identifier

When the user enters the face recognition process, the FSP identifies the user identifier

After decrypting the eigenvalues, the FSP obtains the value of

Summary. In the integrated development of face recognition and homomorphic encryption, key challenges persist: partial HE’s limited computing capability causes low encryption efficiency and high costs, while fully HE’s extreme complexity and slow dynamic updates fail to meet real-time needs. Distributed scenarios face soaring multi-key communication overhead in privacy-accuracy trade-offs.

The proposed scheme addresses this by integrating CKKS homomorphic encryption with deep learning, ensuring ciphertext computation accuracy through hierarchical architecture and parameter tuning, thus enhancing practicality in large-scale cloud-based face recognition.

However, it still confronts critical hurdles: extremely low ciphertext processing efficiency, poor edge device adaptability, cloud security risks from untrusted servers, lack of ciphertext-domain neural training, absence of post-quantum security enhancements, and insufficient optimization for high-dimensional nonlinear operations, restricting large-scale concurrent applications and quantum resistance.

With the rapid development of machine learning technology and the explosive growth of underlying data, it provides the driving force for the progress of the times. At the same time, various privacy protection problems have also emerged. How to protect personal data while being able to apply machine learning technology has become a problem. To solve this problem, the combination of homomorphic encryption and machine learning is the future development trend.

This section presents a systematic exploration of the integration of homomorphic encryption and machine learning from five dimensions: the essence of the technology, application implementation, performance trade-offs, technological convergence and future pathways.

1. Comparison of Different Homomorphic Encryption Schemes:

Homomorphic encryption schemes can be categorized into partial homomorphic encryption (PHE), somewhat homomorphic encryption (SWHE), leveled homomorphic encryption (LHE), and fully homomorphic encryption (FHE). PHE allows only one type of operation (either addition or multiplication) on encrypted data, with low computational complexity but limited functionality. SWHE supports multiple operations but has a limit on the number of computations due to the growth of ciphertext size. LHE relaxes this limitation by introducing a hierarchical structure, while FHE enables arbitrary computations on encrypted data without restrictions. However, FHE(such as the well-known CKKS and BGV schemes) often suffers from high computational complexity. CKKS is designed for approximate arithmetic, making it ideal for handling floating-point numbers commonly used in machine learning, while BGV is more suitable for integer-based computations. Comparing these schemes, the choice depends on the specific requirements of machine learning tasks in terms of the types of operations, data types, and acceptable computational overhead.

In the context of emerging quantum computing threats, traditional homomorphic encryption schemes face new challenges. Quantum computers have the potential to break many of the current cryptographic algorithms that rely on the difficulty of factoring large numbers or computing discrete logarithms. This has led to the urgent need for developing post-quantum secure homomorphic encryption (PQ-HE) schemes. Researchers are exploring new mathematical constructs, such as lattice-based cryptography, code-based cryptography, and multivariate cryptography, to build PQ-HE that can resist quantum attacks. However, these new PQ-HE schemes often introduce additional computational overhead and may require significant modifications to existing machine learning frameworks that rely on homomorphic encryption.

2. Implementing Privacy-Preserving Model Training and Inference with Homomorphic Encryption.

The combination of homomorphic encryption schemes with classic machine learning algorithms and various data analysis methods, and implementing the algorithms in the ciphertext domain is an important research direction. During model training, homomorphic encryption enables data owners to encrypt their data before sending it to the training server. The server can then perform computations on the encrypted data using the homomorphic properties, without ever accessing the plaintext.

In the inference phase, users can submit encrypted input data to the model, and the model can generate encrypted prediction results. These results can only be decrypted by the authorized users, ensuring that the entire process of model inference is privacy-preserving. Selecting multiple homomorphic encryption schemes, trying to obtain higher efficiency and accuracy, and studying how to build and use machine learning models without leaking data.

The high computational cost of homomorphic encryption significantly impacts the practicality of privacy-preserving model training and inference. For large-scale machine learning tasks, the time required for encryption, computation on encrypted data, and decryption can be prohibitively long. This high cost not only slows down the development cycle of machine learning models but also limits the real-time application scenarios, such as real-time fraud detection in financial transactions. To address this issue, researchers are exploring techniques such as bootstrapping in FHE, which can reduce the noise growth in ciphertext during repeated computations, and hardware acceleration, such as using Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) or Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), to speed up the encryption and decryption processes.

3. Trade-offs among Efficiency, Accuracy and Security.

Efficiency, accuracy, and security form a complex trade-off relationship in homomorphic encryption-based machine learning. Higher security levels, such as those provided by FHE, usually come at the cost of significantly increased computational complexity, which reduces efficiency. For example, using FHE for a large-scale image classification task may take hours or even days to complete, while using PHE or a less secure encryption method could finish in a much shorter time.

Accuracy can also be affected. Some encryption schemes may introduce approximation errors during computations on encrypted data, especially when handling complex non-linear operations in machine learning models. For instance, in CKKS, although it is designed for approximate arithmetic, the approximation may lead to a slight decrease in the accuracy of the final prediction results. To balance these factors, researchers need to carefully select encryption schemes and optimize algorithms according to the specific requirements of the application scenarios, sacrificing a certain degree of one aspect to meet the needs of others.

4. CKKS in the Federated Learning Framework.

In the context of federated learning, CKKS plays a crucial role. Federated learning aims to train a global model across multiple decentralized devices or parties without sharing raw data. CKKS, with its ability to handle floating-point numbers, is well-suited for many machine learning tasks in federated learning scenarios.

For example, in a collaborative medical diagnosis federated learning system, different hospitals may have their own patient data. By using CKKS, these hospitals can encrypt their data, which often contains floating-point values such as test results, and participate in the joint training of a diagnosis model. The computational complexity of CKKS is relatively high compared to some simpler encryption schemes, but its performance can be optimized in the federated learning framework.

However, as quantum computing power advances, the security of CKKS-based federated learning models may be compromised. Additionally, the high computational cost of CKKS still poses challenges for resource-constrained devices participating in federated learning, such as mobile devices. Future research will need to focus on developing post-quantum secure versions of CKKS and further optimizing its computational efficiency to make it more accessible for a wider range of devices and applications.

5. Challenges and Future Directions.

Although homomorphic encryption technology theoretically guarantees data security, this technology still has many security vulnerabilities. With the development of technology, it may still be attacked. It is necessary to continuously fill the technical loopholes and enhance the technical security. The current computational complexity of homomorphic encryption technology is relatively high, which limits its application on large scale datasets. Future research will focus on algorithm optimization and technical improvement to reduce the computational complexity and improve the efficiency of encryption and decryption.

In dynamic fog computing environments, the scalability of SLO-aware strategies faces challenges including high multi-key management complexity, difficult adaptive noise control, and low real-time resource orchestration efficiency. Future work should focus on integrating federated learning with fog architecture, combined with FPGA-accelerated adaptive noise algorithms and lightweight task scheduling protocols for optimization. Concurrently, homomorphic encryption can be combined with other privacy enhancing technologies (such as differential privacy, anonymization, etc.) to form a more powerful privacy protection scheme. With the increase of security threats such as adversarial attacks and poisoning attacks, future privacy protection models need to have stronger robustness to deal with more complex attack scenarios.

Improving the compatibility of homomorphic encryption schemes with different deep learning models, especially handling the homomorphic encryption calculations of complex non-linear layers and activation functions, is a necessary condition for achieving widespread applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to all the editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Funding Statement: This work was jointly supported by the following projects: Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62172436. Self-Initiated Scientific Research Project of the Chinese People’s Armed Police Force under Grant ZZKY20243129. Basic Frontier Innovation Project of the Engineering University of the Chinese People’s Armed Police Force under Grant WJY202421.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xu An Wang, Lingling Wu, Wenhao Liu; data collection: Jiasen Liu, Yunxuan Su, Zheng Tu, Haibo Lei; analysis and interpretation of results: Dianhua Tang, Yunfei Cao, Jianping Zhang; draft manuscript preparation: Lingling Wu, Jiasen Liu, Yunxuan Su, Zheng Tu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data are contained within the article. All databases are publicly available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gates C, Matthews P. Data is the new currency. In: Proceedings of the 2014 New Security Paradigms Workshop; Victoria, BC, Canada: ACM; 2014. p. 105–16. doi:10.1145/2683467.2683477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Brown T, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan JD, Dhariwal P, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:1877–901. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kang M, Ting FF, Phan RCW, Ge Z, Ting C. A multi-modal feature distillation with CNN-transformer network for brain tumor segmentation with incomplete modalities. arXiv:2404.14019. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2404.14019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhao J, Bagchi S, Avestimehr S, Chan K, Chaterji S, Dimitriadis D, et al. The federation strikes back: a survey of federated learning privacy attacks, defenses, applications, and policy landscape. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(9):1–37. doi:10.1145/3724113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Demelius L, Kern R, Trügler A. Recent advances of differential privacy in centralized deep learning: a systematic survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(6):1–28. doi:10.1145/3712000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sathish Kumar G, Premalatha K, Uma Maheshwari G, Rajesh Kanna P. No more privacy Concern: a privacy-chain based homomorphic encryption scheme and statistical method for privacy preservation of user’s private and sensitive data. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;234(1):121071. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kumar S, Chaube MK, Nenavath SN, Gupta SK, Tetarave SK. Privacy preservation and security challenges: a new frontier multimodal machine learning research. Int J Sens Netw. 2022;39(4):227. doi:10.1504/ijsnet.2022.125113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jaydip S. Data Privacy-Techniques, Applications, and Standards. IntechOpen; 2025 Jan. doi:10.5772/intechopen.1003421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nwafor IE. Artificial iintelligence facial recognition surveillance and the breach of privacy rights: the ‘Clearview AI’ and ‘Rite Aid’ case studies. S Afr N Intellect Prop Law J. 2023;11(1):88–92. doi:10.47348/saipl/v11/a5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Tanuwidjaja HC, Choi R, Baek S, Kim K. Privacy-preserving deep learning on machine learning as a service—a comprehensive survey. IEEE Access. 2020;8:167425–47. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3023084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Schneider T. Engineering privacy-preserving machine learning protocols. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Workshop on Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning in Practice; Virtual Event, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 3–4. doi:10.1145/3411501.3418607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kaissis G, Ziller A, Passerat-Palmbach J, Ryffel T, Usynin D, Trask A, et al. End-to-end privacy preserving deep learning on multi-institutional medical imaging. Nat Mach Intell. 2021;3(6):473–84. doi:10.1038/s42256-021-00337-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jeon Y, Erez M, Orshansky M. Artemis: he-aware training for efficient privacy-preserving machine learning. arXiv:2310.01664. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2310.01664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lou Q, Jiang L. Hemet: a homomorphic-encryption-friendly privacy-preserving mobile neural network architecture. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2021. p. 7102–10. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2106.00038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chillotti I, Joye M, Paillier P. New challenges for fully homomorphic encryption. In: Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning (PPML-PriML 2020) NeurIPS 2020 Workshop; 2020. doi:10.5120/15902-5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Koç ÇK. Formidable challenges in hardware implementations of fully homomorphic encryption functions for applications in machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 4th ACM Workshop on Attacks and Solutions in Hardware Security; Virtual Event, USA: ACM; 2020. 3 p. doi:10.1145/3411504.3421208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lee JW, Kang H, Lee Y, Choi W, Eom J, Deryabin M, et al. Privacy-preserving machine learning with fully homomorphic encryption for deep neural network. IEEE Access. 2022;10:30039–54. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3159694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pal S, Swaminathan K, Aharoni E, Kushnir E, Drucker N, Schaul H. Fully homomorphic encryption for computer architects: a fundamental characterization study. In: Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture. ACM; 2023. [Google Scholar]

19. Song C, Huang R. Secure convolution neural network inference based on homomorphic encryption. Appl Sci. 2023;13(10):6117. doi:10.3390/app13106117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Moon S, Lee WH. Privacy-preserving federated learning in healthcare. In: 2023 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC); 2023 Feb 5–8; Singapore. IEEE; 2023. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/ICEIC57457.2023.10049966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang Z, Sun X. A compact attribute-based encryption scheme supporting computing outsourcing in fog computing. Comput Eng Sci. 2022;44(3):427. [Google Scholar]

22. Qu C, Calheiros RN, Buyya R. SLO-aware deployment of web applications requiring strong consistency using multiple clouds. In: 2015 IEEE 8th International Conference on Cloud Computing; 2015 Jun 27–Jul 2; New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 860–8. doi:10.1109/CLOUD.2015.118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cheon JH, Kim A, Kim M, Song Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In: Advances in Cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2017: 23rd International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptology and Information Security; 2017 Dec 3–7; Hong Kong, China: Springer; 2017. p. 409–37. [Google Scholar]

24. Lee Y, Cheon S, Kim D, Lee D, Kim H. ELASM: error-latency-aware scale management for fully homomorphic encryption. In: 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23). Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2023. p. 4697–714. doi:10.5555/3620237.3620500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Acar A, Aksu H, Uluagac AS, Conti M. A survey on homomorphic encryption schemes. ACM Comput Surv. 2019;51(4):1–35. doi:10.1145/3214303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Biksham V, Vasumathi D. A lightweight fully homomorphic encryption scheme for cloud security. Int J Inf Comput Secur. 2020;13(3/4):357. doi:10.1504/ijics.2020.109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ren X, Su L, Gu Z, Wang S, Li F, Xie Y, et al. Heda: multi-attribute unbounded aggregation over homomorphically encrypted database. Proc VLDB Endow. 2022;16(4):601–14. doi:10.14778/3574245.3574248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Rivest RL, Shamir A, Adleman L. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Commun ACM. 1978;21(2):120–6. doi:10.1145/359340.359342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Elgamal T. A public key cryptosystem and a signature scheme based on discrete logarithms. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 1985;31(4):469–72. doi:10.1109/TIT.1985.1057074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Benaloh JDC. Verifiable secret-ballot elections. Yale University; 1987. doi:10.5555/914093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Paillier P. Public-key cryptosystems based on composite degree residuosity classes. In: International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques. Springer; 1999. p. 223–38. doi:10.1007/3-540-48910-X_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. van Dijk M, Gentry C, Halevi S, Vaikuntanathan V. Fully homomorphic encryption over the integers. In: Advances in Cryptology-EUROCRYPT 2010: 29th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2010 May 30–Jun 3; Riviera, French: Springer. p. 24–43. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13190-5_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Brakerski Z. Fully homomorphic encryption without modulus switching from classical GapSVP. In: Advances in cryptology–CRYPTO 2012. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2012. p. 868–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-32009-5_50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Fan JF, Vercauteren F. Somewhat practical fully homomorphic encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2012 [Google Scholar]

35. Brakerski Z, Gentry C, Vaikuntanathan V. (Leveled) fully homomorphic encryption without bootstrapping. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference; Cambridge, MA, USA: ACM; 2012. p. 309–25. doi:10.1145/2090236.2090262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Cheon JH, Han K, Kim A, Kim M, Song Y. Bootstrapping for approximate homomorphic encryption. In: Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2018: 37th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2018 Apr 29–May 3; Tel Aviv, Israel: Springer. p. 360–84. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-78381-9_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chillotti I, Gama N, Georgieva M, Izabachène M. TFHE: fast fully homomorphic encryption over the torus. J Cryptol. 2020;33(1):34–91. doi:10.1007/s00145-019-09319-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Lee JW, Lee E, Lee Y, Kim YS, No JS. High-precision bootstrapping of RNS-CKKS homomorphic encryption using optimal minimax polynomial approximation and inverse sine function. In: Advances in cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2021. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2012. p. 618–47. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-77870-5_22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Bonte C, Iliashenko I, Park J, Pereira HVL, Smart NP. FINAL: faster FHE instantiated with NTRU and LWE. Springer Nature Switzerland; 2022. p. 188–215. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-22966-4_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kim J, Kim S, Choi J, Park J, Kim D, Ahn JH. SHARP: a short-word hierarchical accelerator for robust and practical fully homomorphic encryption. In: Proceedings of the 50th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture; Orlando, FL, USA. ACM; 2023. p. 1–15. doi:10.1145/3579371.3589053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Hu J, Wang F, Chen K. Faster matrix approximate homomorphic encryption. Comput Stand Interfaces. 2024;87(1):103775. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2023.103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lee S, Shin DJ. Overflow-detectable floating-point fully homomorphic encryption. IEEE Access. 2024;12(814):6160–80. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3351738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Aguilar-Melchor C, Dyseryn V, Gaborit P. Somewhat homomorphic encryption based on random codes. Des Codes Cryptogr. 2025;93(6):1645–69. doi:10.1007/s10623-024-01555-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Parmar PV, Padhar SB, Patel SN, Bhatt NI, Jhaveri RH. Survey of various homomorphic encryption algorithms and schemes. Int J Comput Appl. 2014;91(8):26–32. doi:10.5120/15902-5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Boneh D, Goh EJ, Nissim K. Evaluating 2-dnf formulas on ciphertexts. In: Theory of Cryptography: Second Theory of Cryptography Conference, TCC 2005; 2005 Feb 10–12; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30576-7_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Rabin M. Digitalized signatures and public key functions as intractable as factorization, 1979. Cambridge, MA, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Laboratory for Computer Science; 2023. doi:10.5555/889813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Chen H, Dai W, Kim M, Song Y. Efficient homomorphic conversion between (ring) LWE ciphertexts. In: Applied cryptography and network security. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 460–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78372-3_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Bae Y, Cheon JH, Kim J, Stehlé D. Bootstrapping bits with CKKS. In: Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; Cham: Springer; 2024. p. 94–123. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-58723-8_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Lu YL, Lu JF. A universal approximation theorem of deep neural networks for expressing probability distributions. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:3094–3105. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2004.08867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Hernández-Orozco S, Zenil H, Riedel J, Uccello A, Kiani NA, Tegnér J. Algorithmic probability-guided machine learning on non-differentiable spaces. Front Artif Intell. 2020;3:567356. doi:10.3389/frai.2020.567356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. von Rueden L, Mayer S, Sifa R, Bauckhage C, Garcke J. Combining machine learning and simulation to a hybrid modelling approach: current and future directions. In: Advances in intelligent data analysis XVIII. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 548–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-44584-3_43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Murphy KP. Machine learning: a probabilistic perspective. MIT Press; 2012. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-3532-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Li P, Li J, Huang Z, Gao CZ, Chen WB, Chen K. Privacy-preserving outsourced classification in cloud computing. Clust Comput. 2018;21(1):277–86. doi:10.1007/s10586-017-0849-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Juvekar C, Vaikuntanathan V, Chandrakasan A. GAZELLE: a low latency framework for secure neural network inference. In: 27th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 18). USENIX Association; 2018. p. 1651–69. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1801.05507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Morampudi MK, Prasad MVNK, Verma M, Raju USN. Secure and verifiable iris authentication system using fully homomorphic encryption. Comput Electr Eng. 2021;89(1):106924. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2020.106924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Sirichotedumrong W, Maekawa T, Kinoshita Y, Kiya H. Privacy-preserving deep neural networks with pixel-based image encryption considering data augmentation in the encrypted domain. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2019 Sep 22–25; Taipei, China: IEEE; 2019. p. 674–8. doi:10.1109/icip.2019.8804201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Chen B, Zheng X. Implementing linear regression with homomorphic encryption. Procedia Comput Sci. 2022;202(3):324–9. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.04.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Liu J, Wang C, Tu Z, Wang XA, Lin C, Li Z. Secure KNN classification scheme based on homomorphic encryption for cyberspace. Secur Commun Netw. 2021;2021(5):8759922. doi:10.1155/2021/8759922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Frery J, Stoian A, Bredehoft R, Montero L, Kherfallah C, Chevallier-Mames B, et al. Privacy-preserving tree-based inference with TFHE. In: International Conference on Mobile, Secure, and Programmable Networking. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023. p. 139–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-52426-4_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Song C, Shi X. ReActHE: a homomorphic encryption friendly deep neural network for privacy-preserving biomedical prediction. Smart Health. 2024;32(4):100469. doi:10.1016/j.smhl.2024.100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Li Q, Wu Z, Wen Z, He B. Privacy-preserving gradient boosting decision trees. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(1):784–91. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i01.5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Yang C, Chen J, Wu W, Feng Y. Optimized privacy-preserving clustering with fully homomorphic encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2024. [Google Scholar]

63. Yuan H, Wu W, Chen J. Fast, lagre scale dimensionality reduction schemes based on CKKS. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2024. [Google Scholar]

64. Cover T, Hart P. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 1967;13(1):21–7. doi:10.1109/TIT.1967.1053964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Cheng D, Zhang S, Deng Z, Zhu Y, Zong M. KNN algorithm with data-driven k value. In: Advanced Data Mining and Applications: 10th International Conference, ADMA 2014; 2014 Dec 19–21; Guilin, China; Springer; 2014. Proceedings 10, p. 499–512. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-14717-8_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Zhu X, Zhang S, Jin Z, Zhang Z, Xu Z. Missing value estimation for mixed-attribute data sets. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2010;23(1):110–21. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2010.99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Zhu X, Ying C, Wang J, Li J, Lai X, Wang G. Ensemble of ML-KNN for classification algorithm recommendation. Knowl Based Syst. 2021;221(1):106933. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2021.106933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Levchenko O, Kolev B, Yagoubi DE, Akbarinia R, Masseglia F, Palpanas T, et al. BestNeighbor: efficient evaluation of kNN queries on large time series databases. Knowl Inf Syst. 2021;63(2):349–78. doi:10.1007/s10115-020-01518-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Li H, Yang Y, Dai Y, Yu S, Xiang Y. Achieving secure and efficient dynamic searchable symmetric encryption over medical cloud data. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2017;8(2):484–94. doi:10.1109/TCC.2017.2769645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Parvin S, Nimmy SF, Venkatraman S, Abed S, Gawanmeh A. A KNN approach for blockchain based electronic health record analysis. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Systems Engineering, ICSEng 2020; Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 455–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-65796-3_44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Zheng Y, Zhu H, Lu R, Guan Y, Zhang S, Wang F, et al. PHRkNN: efficient and privacy-preserving reverse kNN query over high-dimensional data in cloud. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2023;21(4):1831–44. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2023.3291715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Behera S, Prathuri JR. FPGA-based acceleration of K-nearest neighbor algorithm on fully homomorphic encrypted data. Cryptography. 2024;8(1):8. doi:10.3390/cryptography8010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Liu H, Xing J. Encrypted data inner product KNN secure query based on BALL-PB tree. Comput Stand Interfaces. 2025;92(7):103901. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2024.103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Yang H, Liang S, Ni J, Li H, Shen XS. Secure and efficient kNN classification for industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(11):10945–54. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.2992349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Petrean DE, Potolea R. Random knn evaluation using multi-key homomorphic encryption. In: 2024 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP); 2024 Oct 17–19; Cluj-Napoca, Romania; IEEE; 2024. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/ICCP63557.2024.10793031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Ameur Y, Aziz R, Audigier V, Bouzefrane S. Secure and non-interactive k-NN classifier using symmetric fully homomorphic encryption. In: Privacy in statistical databases. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 142–54. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-13945-1_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Wang C, Xu J, Li J, Dong Y, Naik N. Outsourced privacy-preserving kNN classifier model based on multi-key homomorphic encryption. Intell Autom Soft Comput. 2023;37(2):1421–36. doi:10.32604/iasc.2023.034123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Liu AX, Li R. K-nearest neighbor queries over encrypted data. In: Algorithms for data and computation privacy. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 79–108. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58896-0_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Chen S, Zheng Y, Lu W, Varadarajan V, Wang K. Energy-optimal dynamic computation offloading for industrial IoT in fog computing. IEEE Trans Green Commun Netw. 2020;4(2):566–76. doi:10.1109/TGCN.2019.2960767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Seo W, Cha S, Kim Y, Huh J, Park J. SLO-aware inference scheduler for heterogeneous processors in edge platforms. ACM Trans Archit Code Optim. 2021;18(4):1–26. doi:10.1145/3460352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Bunn P, Ostrovsky R. Secure two-party k-means clustering. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Alexandria, VA, USA; ACM; 2007. p. 486–97. doi:10.1145/1315245.1315306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Liu D, Bertino E, Yi X. Privacy of outsourced k-means clustering. In: Proceedings of the 9th ACM Symposium on Information, Computer and Communications Security. Kyoto, Japan; ACM; 2014. p. 123–34. doi:10.1145/2590296.2590332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Jäschke A, Armknecht F. Unsupervised machine learning on encrypted data. In: International Conference on Selected Areas in Cryptography. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 453–78. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-10970-7_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Jia CF, Li RQ, Wang YF. Privacy protection scheme of DBSCAN clustering based on homomorphic encryption. J Commun. 2021;42(2):1–11. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

85. Zuo L, Xu ZX, Xiao MX. A privacy-preserving k-means clustering algorithm for data privacy in multi-chain blockchain. Communicat Technol. 2022;55(6):771–5. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-0802.2022.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Tu Z, Wang XA, Su Y, Li Y, Liu J. Toward secure K-means clustering based on homomorphic encryption in cloud. In: Advances in internet, data & web technologies. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 52–62. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-95903-6_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]