Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network with Pyramid Attention Module for Face Generation

1 Amrita School of Computing, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Amaravati, 522503, India

2 Department of Teleinformatics Engineering, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, 60455-970, Brazil

3 Department of Information Technology, Siddhartha Academy of Higher Education, Vijayawada, 520007, India

4 Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Sreenidhi Institute of Science and Technology, Hyderabad, 501301, India

5 Department of AI, Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University, Alkhobar, 31952, Saudi Arabia

6 Center for Computational Social Science, Hanyang University, Seoul, 01000, Republic of Korea

7 Department of Computer Science, Hanynag University, Seoul, 01000, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Byoungchol Chang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 2117-2139. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065232

Received 07 March 2025; Accepted 19 May 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

The generation of high-quality, realistic face generation has emerged as a key field of research in computer vision. This paper proposes a robust approach that combines a Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network (SRGAN) with a Pyramid Attention Module (PAM) to enhance the quality of deep face generation. The SRGAN framework is designed to improve the resolution of generated images, addressing common challenges such as blurriness and a lack of intricate details. The Pyramid Attention Module further complements the process by focusing on multi-scale feature extraction, enabling the network to capture finer details and complex facial features more effectively. The proposed method was trained and evaluated over 100 epochs on the CelebA dataset, demonstrating consistent improvements in image quality and a marked decrease in generator and discriminator losses, reflecting the model’s capacity to learn and synthesize high-quality images effectively, given adequate computational resources. Experimental outcome demonstrates that the SRGAN model with PAM module has outperformed, yielding an aggregate discriminator loss of 0.055 for real, 0.043 for fake, and a generator loss of 10.58 after training for 100 epochs. The model has yielded an structural similarity index measure of 0.923, that has outperformed the other models that are considered in the current study for analysis.Keywords

AI-generated facial images play a crucial role in creating realistic representations for virtual environments such as social networking, online gaming, and virtual reality (VR) platforms [1]. These generated facial images would enhance the user experiences by offering authentic representations that interact seamlessly in the digital environment, fostering a better sense of presence and realism. Especially in social media, AI-generated facial images can be used for profile images, avatars, and digital influencers, ensuring diversity and representation without the limitations of traditional photography. The other fields include online gaming, where realistic characters enhance narrative immersion and emotional engagement, providing players with a more captivating experience. In VR applications, realistic portraits are valuable for virtual meetings, therapeutic sessions, and educational simulations, enabling participants to feel more connected and engaged within shared virtual spaces. AI-generated faces bridge up the gap between real and virtual worlds, enabling more authentic and inclusive digital interactions [2].

The recent advancements in the VR technology for human face generation relying on models like generative adversarial network, residual frequency attention, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [3], Transfer Models [4] and self-attention models [5] are widely used and studied. These models have been set as a new benchmark for photorealism and controllability in face synthesis, enabling high-resolution image generation with fine-grained control over significant facial attributes such as age, expression, and lighting. Residual Frequency Attention, which is a refinement over residual learning, enhances feature representation by fusing multi-scale frequency information, improving the preservation of precise facial textures and features [6]. VAEs are often integrated with GAN models to form VAE-GAN hybrid models, offer structured and interpretable latent spaces that support smooth interpolation between identities, and facilitate conditional generation. In parallel, Transformer-based, self-attention models and Multiview Attention Networks, such as Vision Transformers (ViTs) and Swin Transformers, have introduced global context modeling to facial synthesis tasks, boosting the model’s ability to maintain spatial coherence across complex facial features.

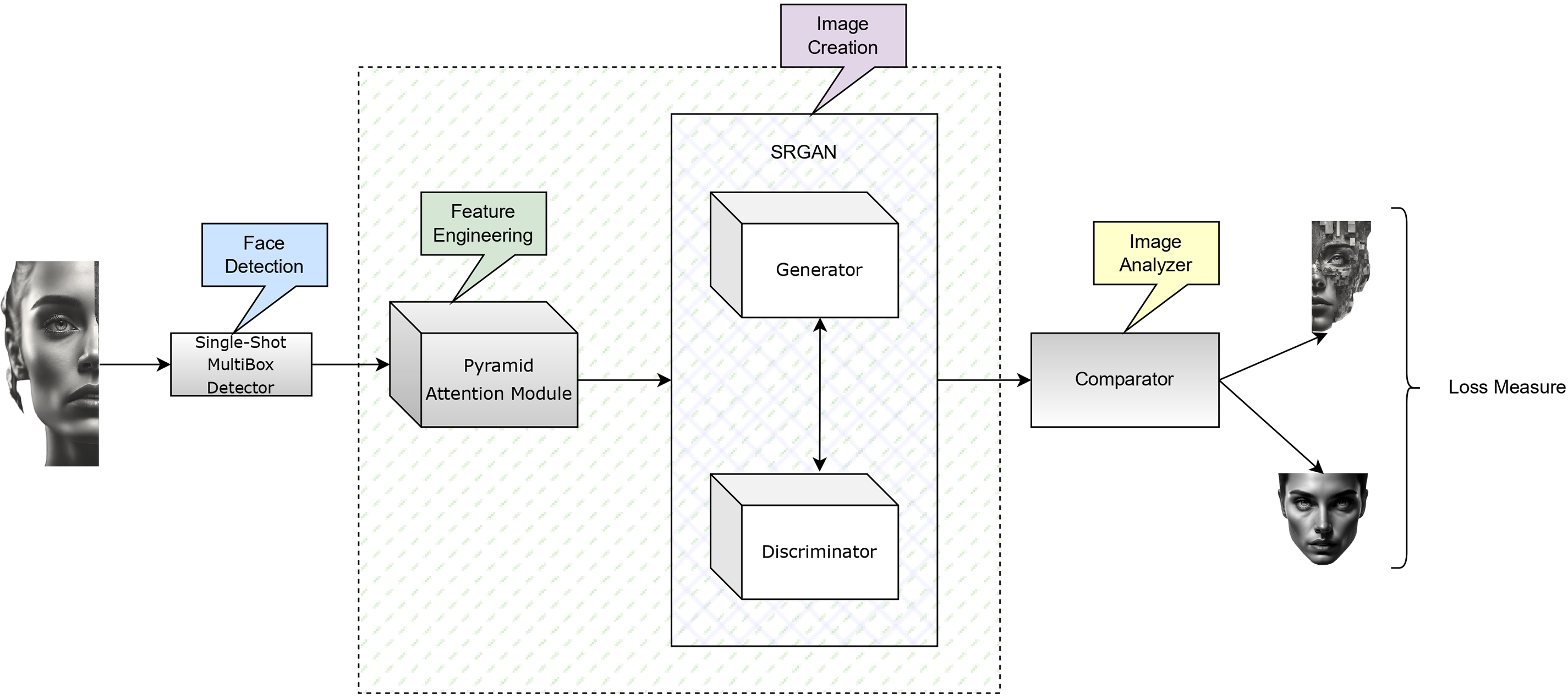

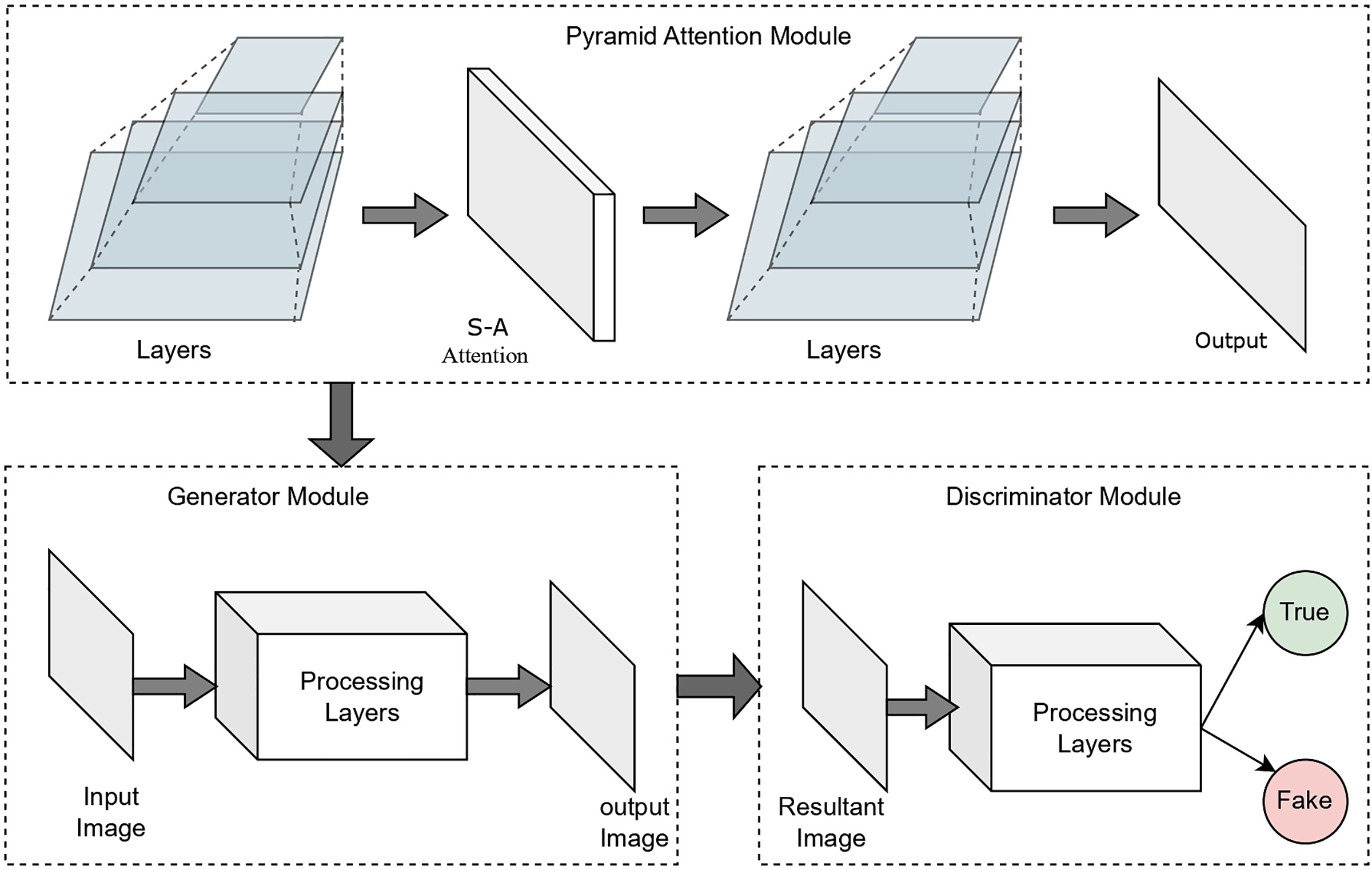

Deep learning has revolutionized many sub-domains of computer vision, particularly the generation of high-quality and realistic images from low-resolution inputs. Among these recent advancements, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [7] have been proven as powerful tools for image synthesis and enhancement. In the current study, a robust novel approach combining a Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network [8] with a Pyramid Attention Module [9], specifically designed for facial image generation. The proposed approach assists in handling the challenge of generating high-resolution face images from low-resolution inputs while preserving both appearance and structural fidelity. The block diagram illustrating various components of the proposed model is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The flow diagram of proposed SR-GAN with PAM for deep face generation

The rest of the sections in the manuscript are organized as follows: Section 2 presents the contributions of the current study. Section 3 reviews existing studies on deep human face generation, while Section 4 details the proposed Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network combined with the Pyramid Attention Module for face image generation. Section 5 outlines the experimental outcome and compares the proposed model with other state-of-the-art models. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study and outlines the future research scope.

The proposed SRGAN with PAM module will integrate super-resolution techniques with attention mechanisms. The Pyramid Attention Module would enable the network to focus on multi-scale features, capturing fine details across varying levels of image quality. By incorporating this module, the model effectively enhances key facial features, ensuring that the generated images are both realistic and structurally accurate. The multi-scale attention mechanism is essential in preserving essential facial characteristics and textures, which are often degraded in conventional super-resolution approaches. The primary objectives of this study are outlined below.

• The generation of realistic human face images is achieved using the Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network combined with the Pyramid Attention Module, which leverages a multi-scale attention mechanism to effectively extract feature-related information and enhance fine details from low-resolution images, including subtle facial traits. This approach results in high-resolution images that closely resemble realistic human faces.

• The Pyramid Attention Module that is used in the encoder module of the current model is efficient in identifying the significant features that enable the network to focus on multiple levels of image resolution simultaneously, ensuring that essential facial attributes are retained across various scales.

• The generator component would generate the high-resolution realistic images from the training data that is available. The discriminator is designed to classify the original and model-generated images.

• The efficiency of the proposed model is evaluated using generator and discriminator loss metrics. In addition to the standard metric to evaluate the performance of GAN models, the current study has also included metrics like Fréchet Inception Distance, perceptual path length, and structural similarity index measure.

This study shows the impact of combining an attention mechanism with super-resolution techniques that can significantly improve the quality of generated human face images. By using the Pyramid Attention Module, the model is better at capturing important facial details that are often lost in low-resolution images. This helps create clearer, more realistic faces. The study also uses several evaluation methods to measure how well the model performs, making it a useful reference for future work in image enhancement and face generation.

In recent years, the generation of human facial images using artificial intelligence (AI) technology has significantly transformed the fields of augmented and virtual reality. These technologies are extensively used in divergent fields like entertainment and media to create realistic characters, avatars, and deepfake technologies, for a better visual effect. In Social Media and Advertising, AI-generated faces are employed for synthetic influencers, personalized marketing content, and virtual models, enabling more engaging and customizable user interactions [10]. Additionally, deep face technology contributes significantly to the healthcare sector, aiding in facial reconstruction from low-quality images. Furthermore, deep face generation is instrumental in data augmentation, enabling the creation of larger datasets for training the supervised models, thereby improving performance in tasks such as facial recognition.

Various techniques have been developed for human face generation. One approach involves conditioning diffusion models through attributes and semantic masks, where Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) assist in generating high-resolution, high-fidelity images. Although these models, when trained on semantic masks, produce accurate results, they often lack the ability to diversify outputs. Diffusion models address this limitation by generating varied samples under the same conditions. These models have been evaluated on the CelebFaces Attributes Dataset (CelebA) [11], demonstrating reasonable performance in achieving fine-grained control over multiple attributes across image regions [12]. However, diffusion models rely on existing datasets, and if the data lacks diversity in terms of ethnicity, texture, or variables such as age, the generated faces may exhibit biases reflecting the training data.

Another approach for facial image generation utilizes an attention-guided domain alignment module (DAM) [13], which excels in handling spatial details of facial features. This method aligns information from different sources using attention mechanisms focused on specific facial regions. The model is being assigned with a dedicated index for each feature block and employs a top-k ranking procedure to match block-wise features among the domains. This approach exploits the spatial relationships of facial components while preserving texture structure during alignment. Recovered blocks are then subsequently used in training the local attention models, thereby reducing the computational costs and enabling high-resolution alignment. Finally, adaptive weights are being derived from long-range correlation coefficients are combined with aligned features to capture the semantic coherence of style characteristics across domains.

A model based on StyleGAN2 for human face image generation was proposed by Pries et al. [14]. StyleGAN2’s generator component effectively analyzes the distribution of the input dataset. However, higher-level human facial elements may not be preserved. Despite this limitation, the model can generate new faces using face recognition and transfer typical human traits, such as age and gender, to the output dataset. StyleGAN2 has been demonstrated to efficiently generate unique facial images distinct from the training data.

In another study, Krishna Katta et al. [15] investigated facial image generation using the Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network (DCGAN) [16], which was evaluated on the CelebA dataset. The DCGAN model outperformed others in terms of the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), demonstrating its effectiveness for facial image synthesis.

GAN models have also been applied in medical image augmentation [17]. Studies have explored generating 3D images by training the generator module with 2D input data. For instance, the Dual-Attention Generative Adversarial Network (DA-GAN) [18] was proposed to generate photorealistic frontal faces. DA-GAN achieves realistic image generation by capturing both contextual dependencies and local consistencies during training, allowing it to address positional and illumination discrepancies effectively.

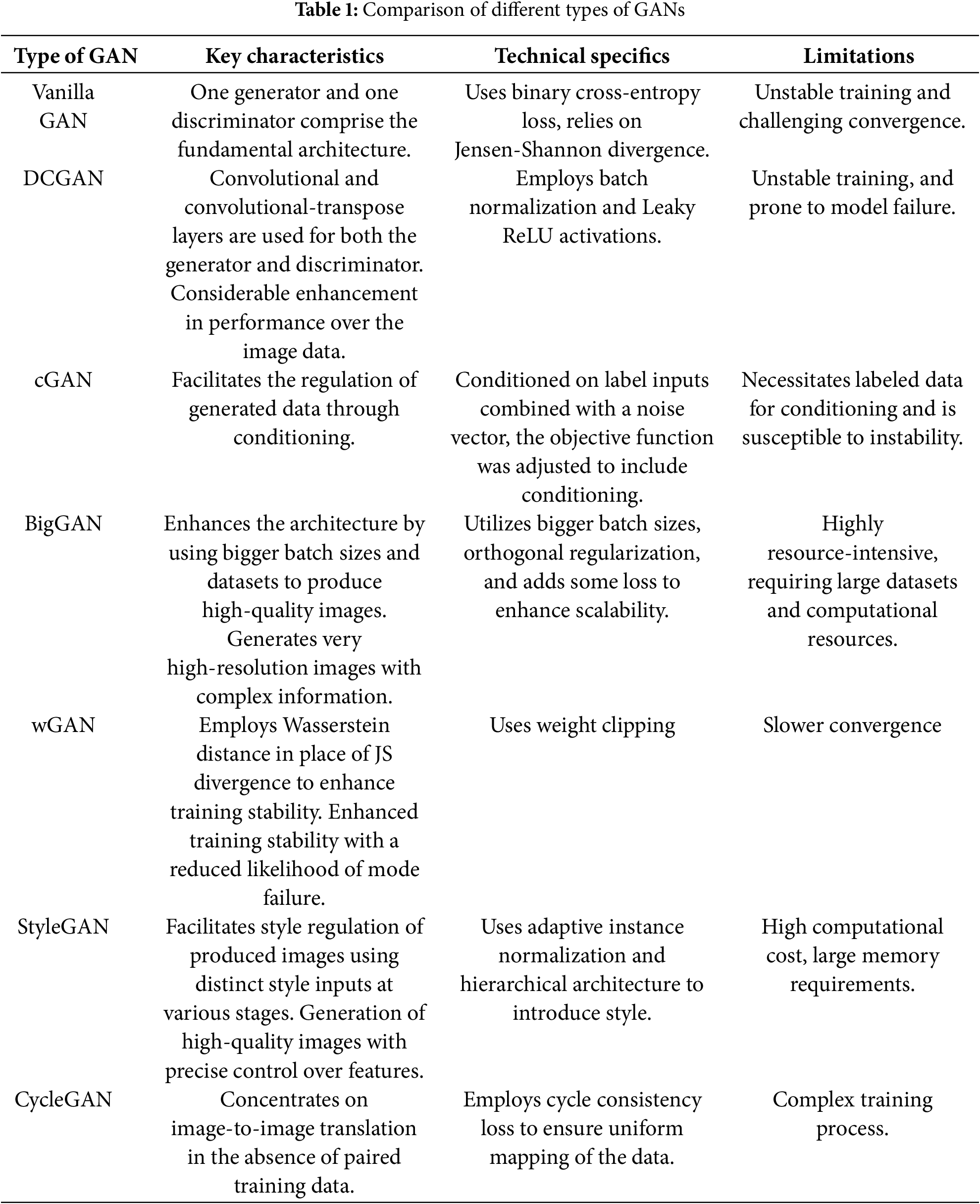

Several GAN variants, including Vanilla GAN [19], Conditional GAN (cGAN) [20], Wasserstein GAN (WGAN) [21], BigGAN [22], and Latent-Space GAN (LS-GAN) [22], offer unique advantages and feasibility for image generation. A detailed comparison of these models is presented in Table 1, highlighting their respective strengths and feasibility for use in image generation.

Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks (SRGANs) represent a significant advancement in image processing, particularly for deep face generation. The integration of a PAM further enhances the performance of neural networks by enabling more precise feature extraction and improved image reconstruction quality. The existing literature on SRGANs highlights their ability to generate high-resolution images from low-resolution inputs through adversarial training, where a generator network synthesizes images and a discriminator network evaluates their authenticity. The PAM employs hierarchical attention mechanisms that prioritize multi-scale features, allowing the network to capture fine-grained details and contextual information more efficiently [23]. Studies have demonstrated that SRGANs combined with PAM outperform traditional methods in terms of facial detail, texture quality, and overall image fidelity.

The current section of the manuscript discusses human face extraction from images as a pre-processing step for effective processing. It also provides details about the dataset and the implementation environment.

Accurate face detection is a critical pre-processing step for AI-based face generation models. This section presents the Single-Shot Multibox Detector (SSMD) model for human face detection in images [24]. The SSMD model, known for its efficiency in object detection with a single forward pass, is highly suitable for real-time applications as it predicts bounding boxes and confidence scores across multiple scales. When integrated with GANs, this detection approach enhances adversarial training by providing accurate input for the generation process. A key component of the SSMD model is the feature pyramid network (FPN), which leverages a convolutional layer to extract feature maps represents the objects at various scales. The FPN architecture consists of a bottom-up pathway linked to a top-down pathway via lateral connections. The SSMD head comprises multiple output maps of varying sizes, where each grid divides the image into pixel groups. Each cell determines whether it corresponds to a specific object using bounding box coordinates and object class information. Lower-resolution output images, consisting of smaller grids with larger pixels, are better suited for identifying larger objects. Conversely, higher-resolution grids with denser pixels are employed to detect smaller objects. The inclusion of multiple output scales significantly improves the model’s accuracy while maintaining its ability to localize a wide range of object sizes. The primary objective of SSMD is to minimize the model’s overall loss. The loss function, L, is defined as the combination of three components: the localization loss (

The loss associated with object localization is computed using the pseudo-Huber loss function [25]. Here, the ground truth coordinates of the face object are denoted by

In the above equation, the parameter

The boxing loss is selected for the ability to discard the false positives, which are the background points that the model incorrectly detects as objects. The SSD model predicts boxes as a real number

From the above equation, the parameter

The current study utilizes the CelebFaces Attributes Dataset [11], a publicly available, large-scale dataset for training the SR-GAN model. The dataset contains 202,599 distinct images of 10,177 celebrities, each annotated with 40 binary attributes such as bald, bangs, big nose, gray hair, blurry, brown hair, chubby, eyeglasses, male, no beard, oval face, and others. These images encompass a wide variety of poses, expressions, lighting conditions, and backgrounds, offering a diverse representation of real-world scenarios.

4.3 Implementation Environment

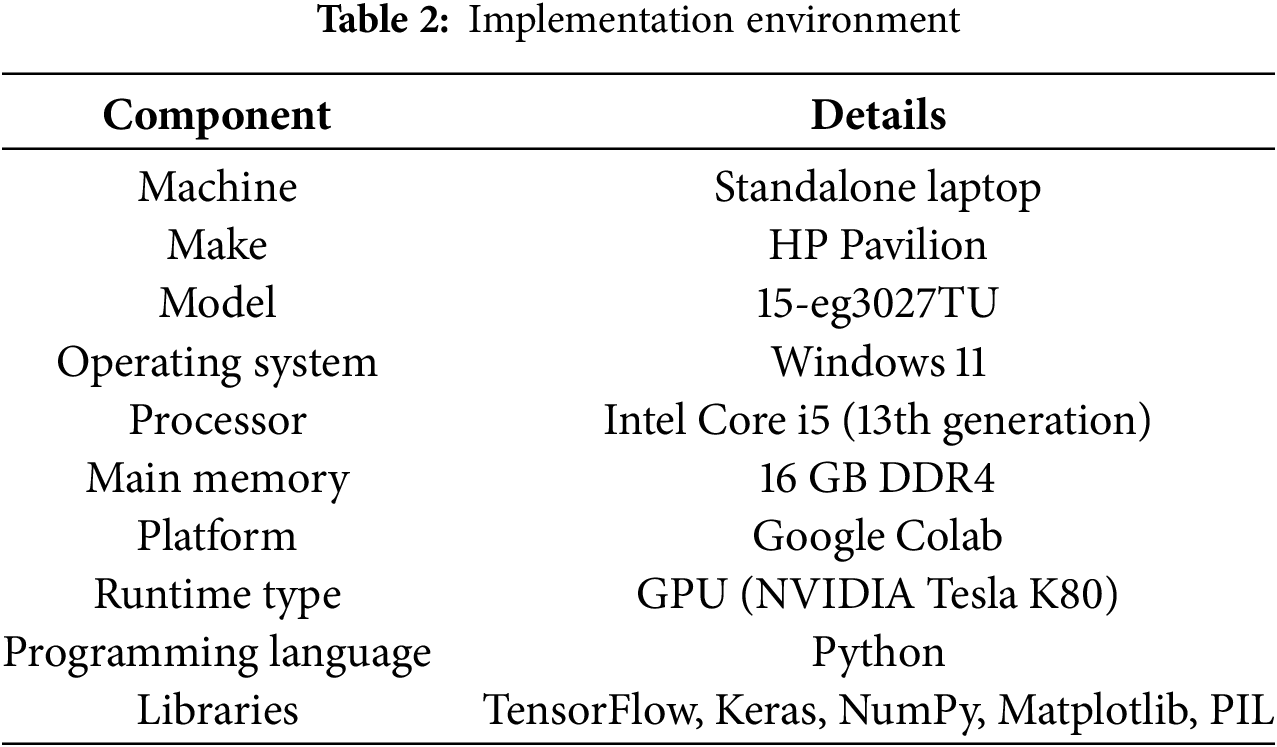

The proposed SR-GAN with PAM model for deep face generation was implemented on a standalone computer using Google Colab with GPU support. Additional details of the implementation environment are provided in Table 2.

This section of the manuscript presents the proposed Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network is being integrated with a Pyramid Attention Module for deep face generation. The model leverages the strengths of both components: SRGAN excels at generating high-resolution images that closely resemble actual images, while PAM enhances these outputs by emphasizing essential features at multiple scales, thereby improving overall image quality and precision.

This integration enables the network to effectively learn contextually relevant information, making the model more robust to variations in facial images, including differences in pose, expression, focus, and illumination conditions. The SRGAN comprises two primary components: the generator module and the discriminator module. The generator creates high-resolution deep-face images based on the provided training data, while the discriminator acts as a classifier to distinguish between the original images and the generated images [26].

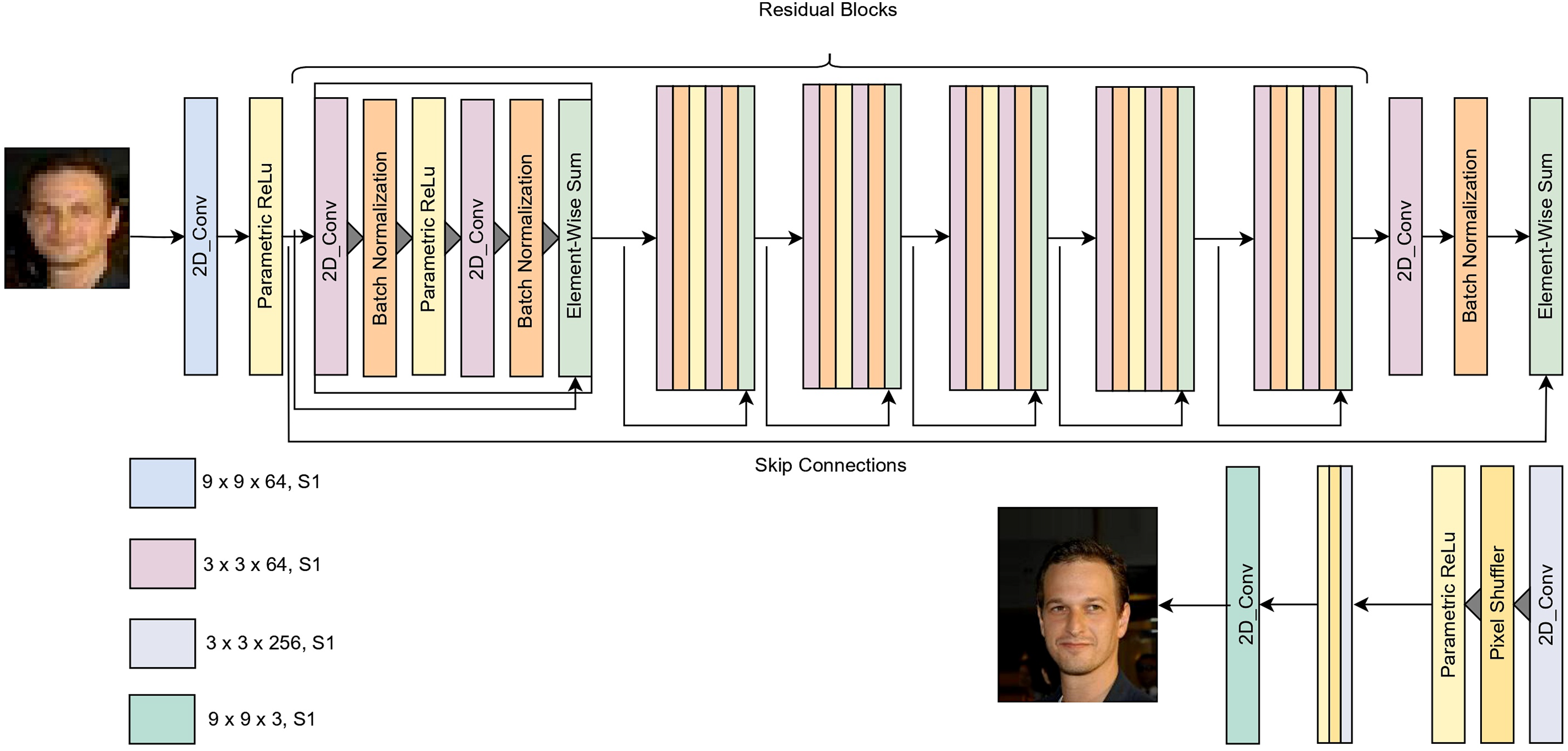

The Generator Module of the SRGAN processes a low-resolution input through a convolutional layer with

The elements of the generator model, along with the size of the kernels used in generating the high-resolution image, are shown in Fig. 2. Residual blocks play a crucial role in addressing the vanishing gradient problem by introducing shortcut connections, which allow gradients to flow more directly through the network. This mechanism preserves the gradient magnitude and facilitates more effective training. To achieve super-resolution, the pixel shuffler is applied after the convolutional layer, performing a

Figure 2: Architecture of the generator module in SRGAN model

The loss function in the generator module is critical for guiding the generator to produce high-quality images from low-resolution inputs. It manages the tradeoff between the accuracy and perceptual quality of the generated images. The generator’s overall loss comprises content loss, adversarial loss, and perceptual loss. Content loss measures the pixel-wise differences between the generated high-resolution image,

In the above equation, the notation

In the equation, the notation

In the equation, the notation E designates the expected values associated with the generated image, while

Here,

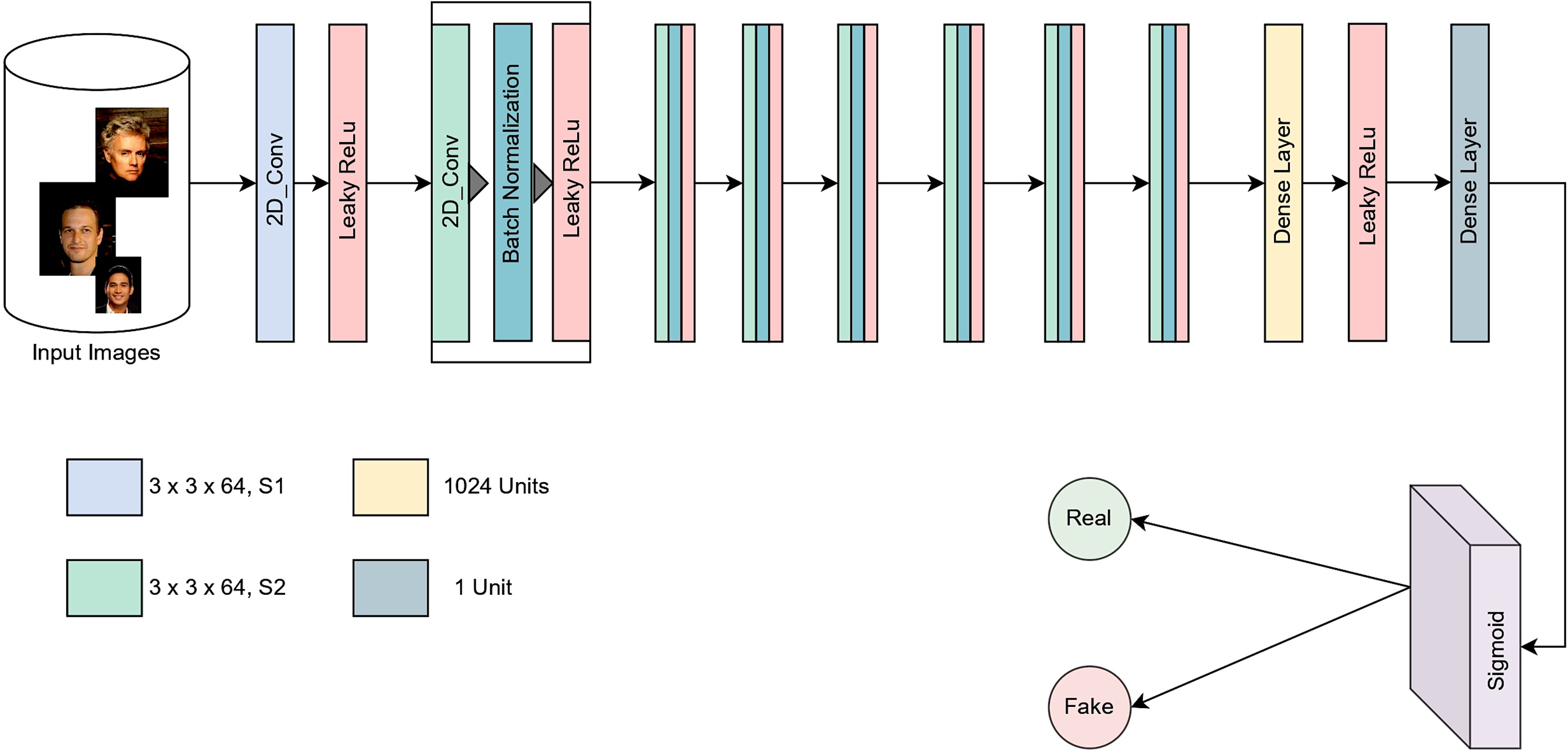

The second key component of the SRGAN is the discriminator module, which evaluates the loss by distinguishing between original and generated images. The discriminator is composed of several components that collaboratively classify inputs into distinct classes. It is implemented as a convolutional neural network (CNN) [28], which extracts features from input images through a series of convolutional layers.

These convolutional layers employ small-sized filters of

Figure 3: Architecture of the discriminator module in SRGAN model

The adversarial loss encourages the generator to produce samples indistinguishable from real images. This loss is calculated separately for the generator and the discriminator, as represented by Eqs. (10) and (11), respectively.

In the above equations,

The Pyramid Attention Module integrates attention mechanisms at multiple pyramid levels, enabling the network to effectively capture fine details and contextual information from images PAM consists of several attention layers, each designed to capture features at a specific level of granularity [29].

In pyramid attention, affinities are computed between the target feature vector and image regions. Consequently, the response feature is calculated as the weighted sum of multi-scale similarities within the input feature map. Using a set of scaling factors represented as

In the above equation,

This feature pyramid is denoted as

In the equation, the notation

Figure 4: The architecture of pyramid attention module

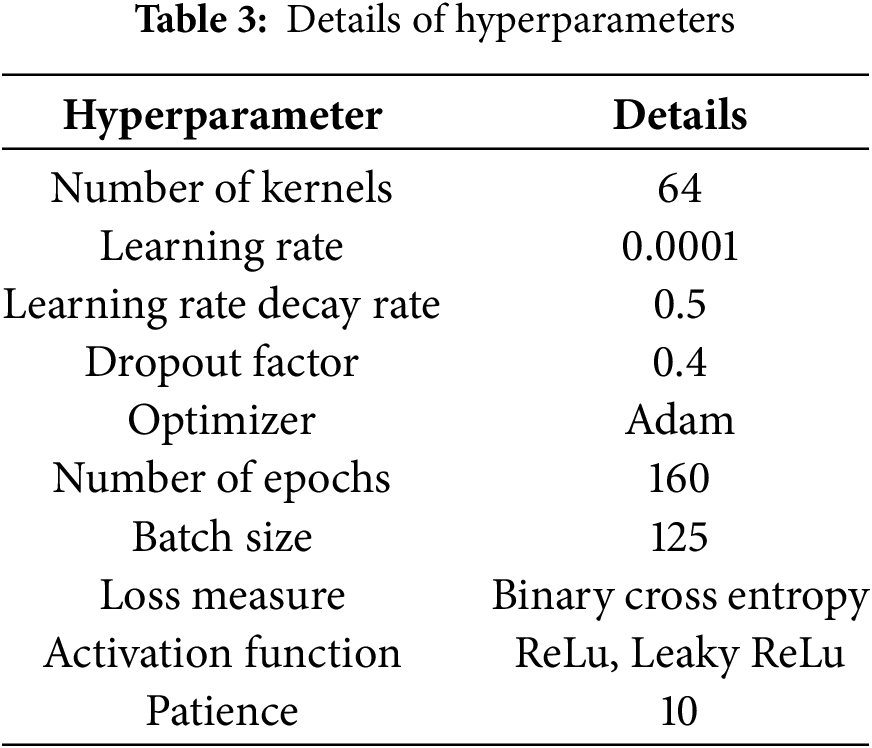

The hyperparameters that have been applied in this study are outlined in Table 3. These hyperparameters were consistently utilized throughout the evaluation process of the proposed model. The hyperparameters were selected based on standard configurations commonly used in this method and aligned with existing studies to ensure a fair and consistent comparison in the performance analysis.

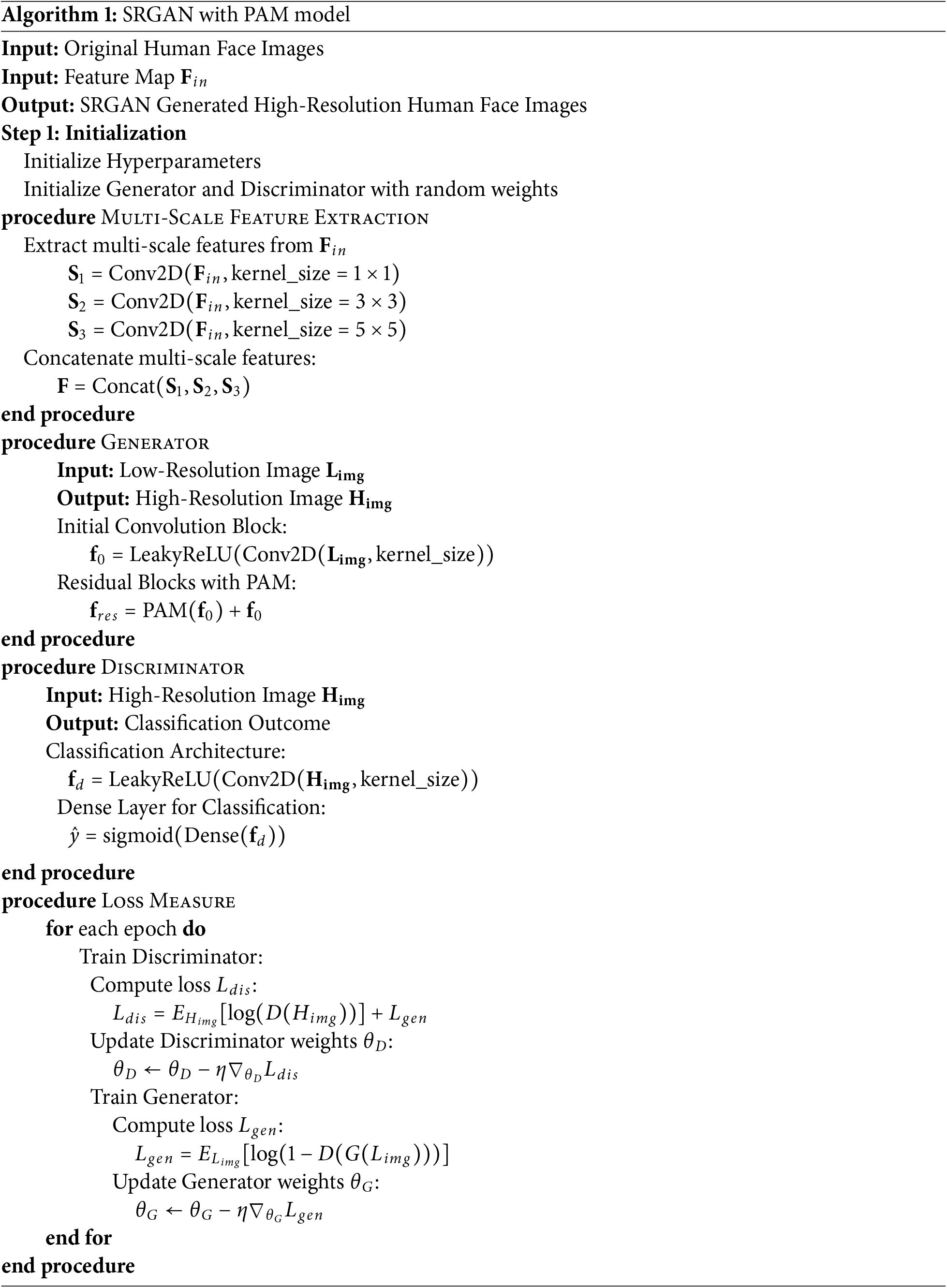

The hyperparameters, as fine-tuned in Table 3, are optimized to enhance the efficacy, efficiency, and adaptability of the model. This fine-tuning improves the model’s performance on unseen data and enhances its generalization capabilities. Adjustments to batch sizes significantly impact the network’s stability and convergence rate. The learning rates of the discriminator and generator are carefully balanced to ensure that neither dominates during training. The corresponding algorithm for the SRGAN with PAM is presented in Algorithm 1.

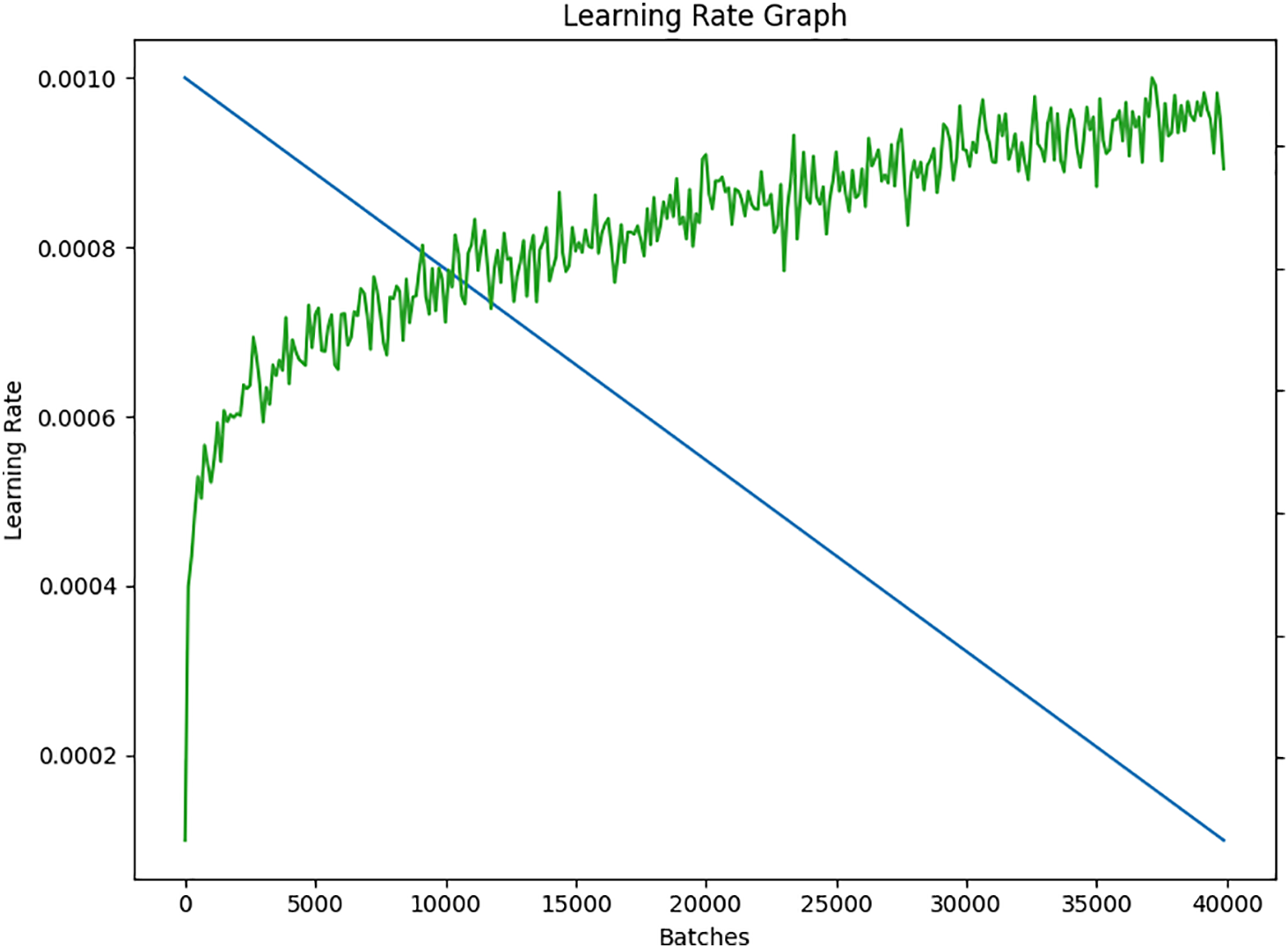

The learning rate is a crucial parameter that determines the speed of learning during the training process. On selecting a higher learning rate increases the risk of overshooting the optimal solution, while a lower learning rate would require more time for the model to converge. Additionally, lower learning rates may result in convergence to a local minima, which can have a negative impact on the model’s generalization capability. The learning rate graph for the proposed model is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The learning rate graph of the proposed model

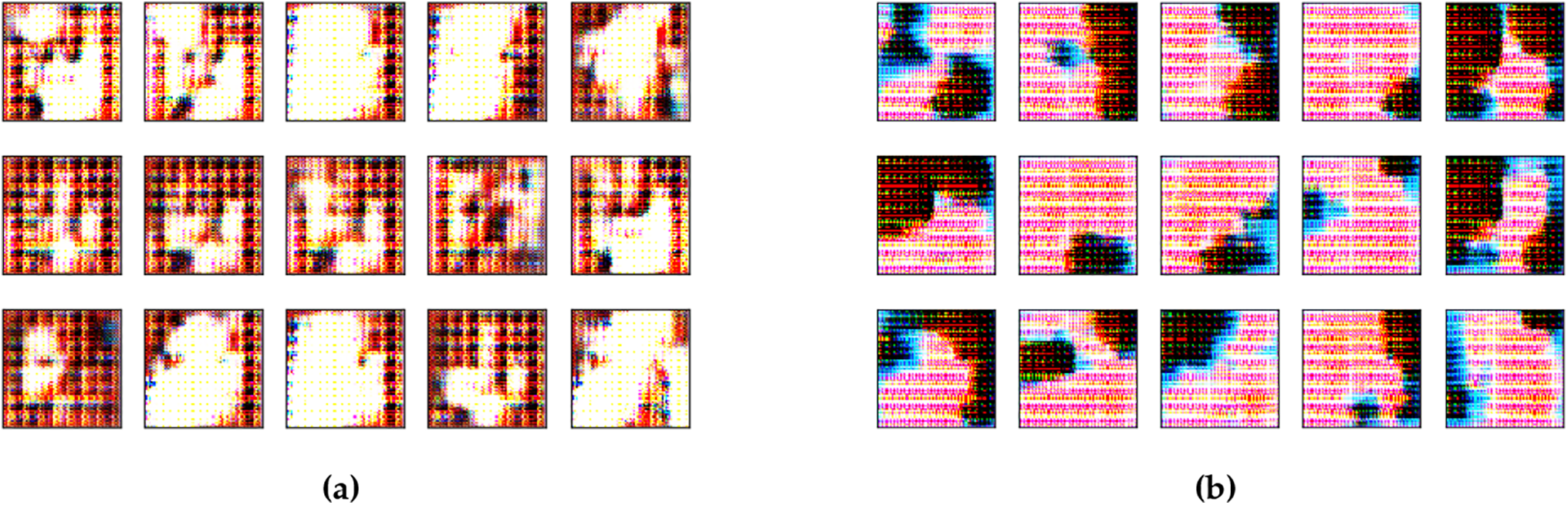

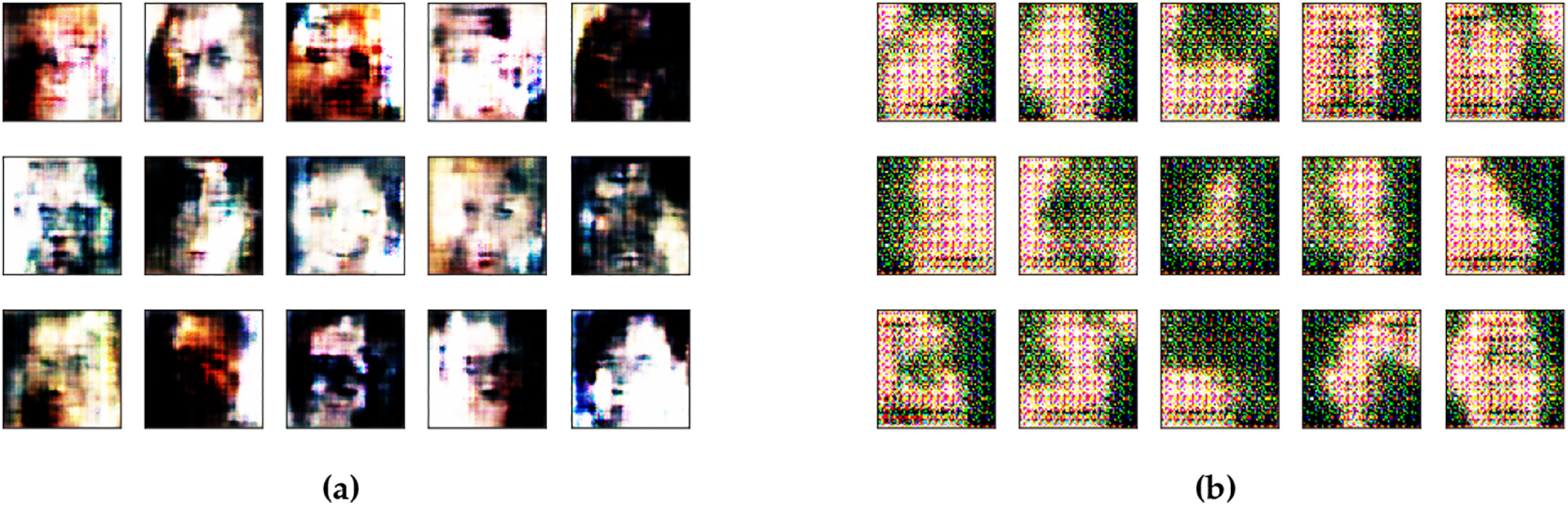

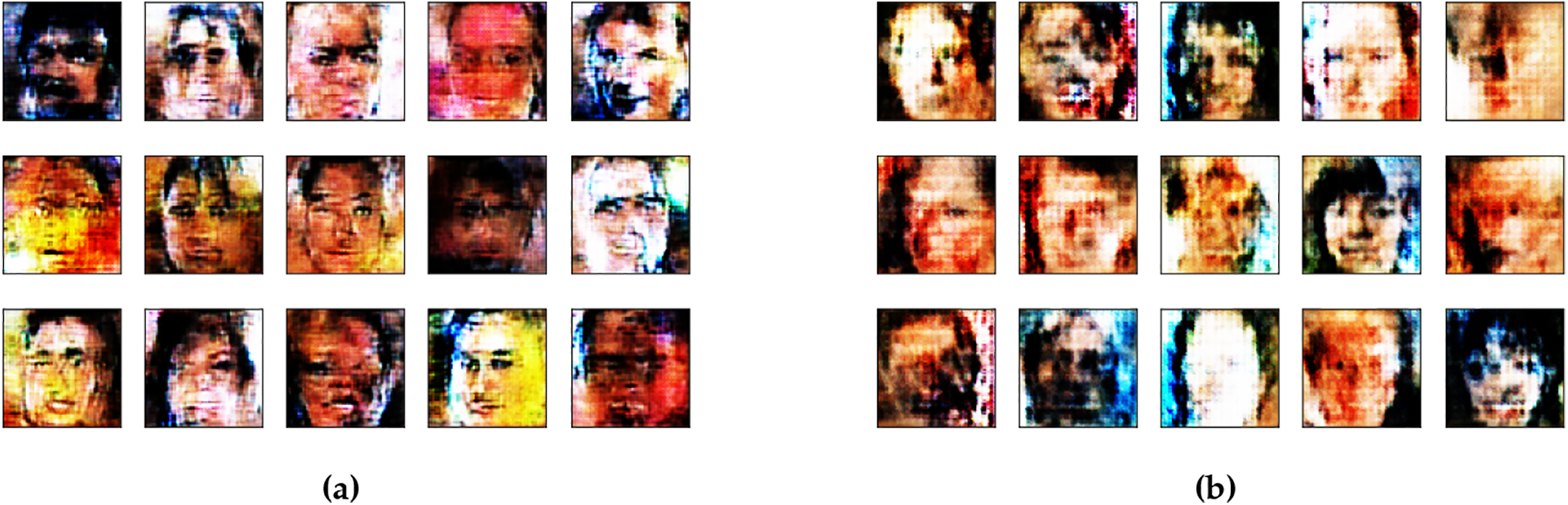

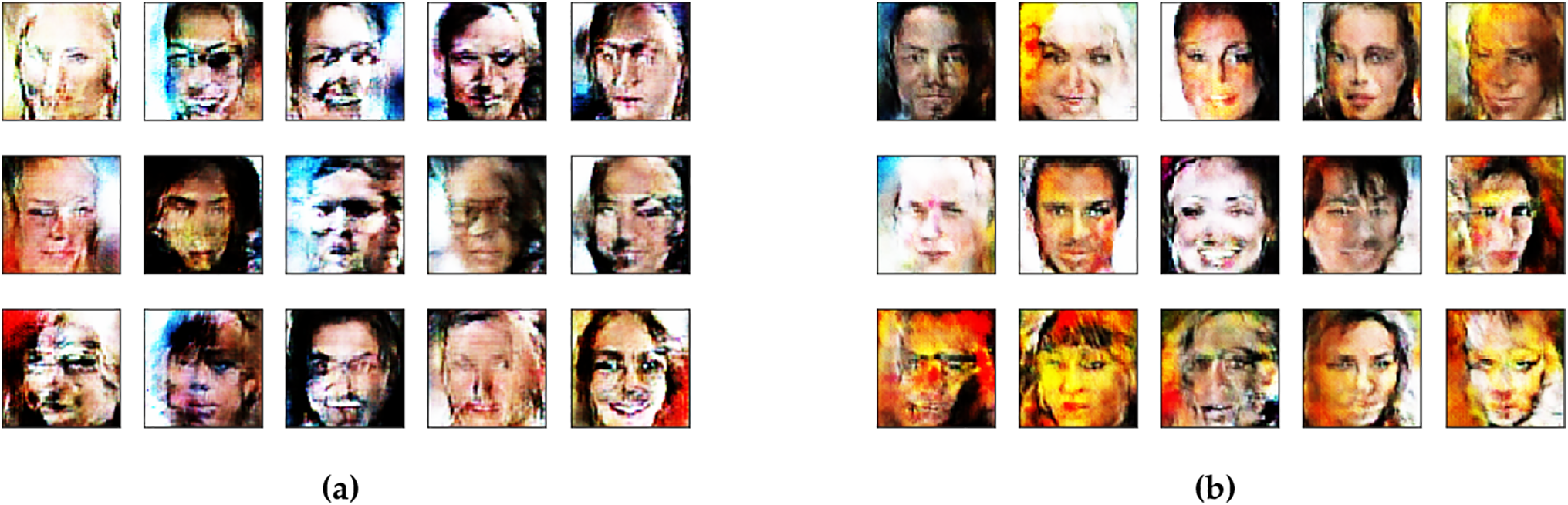

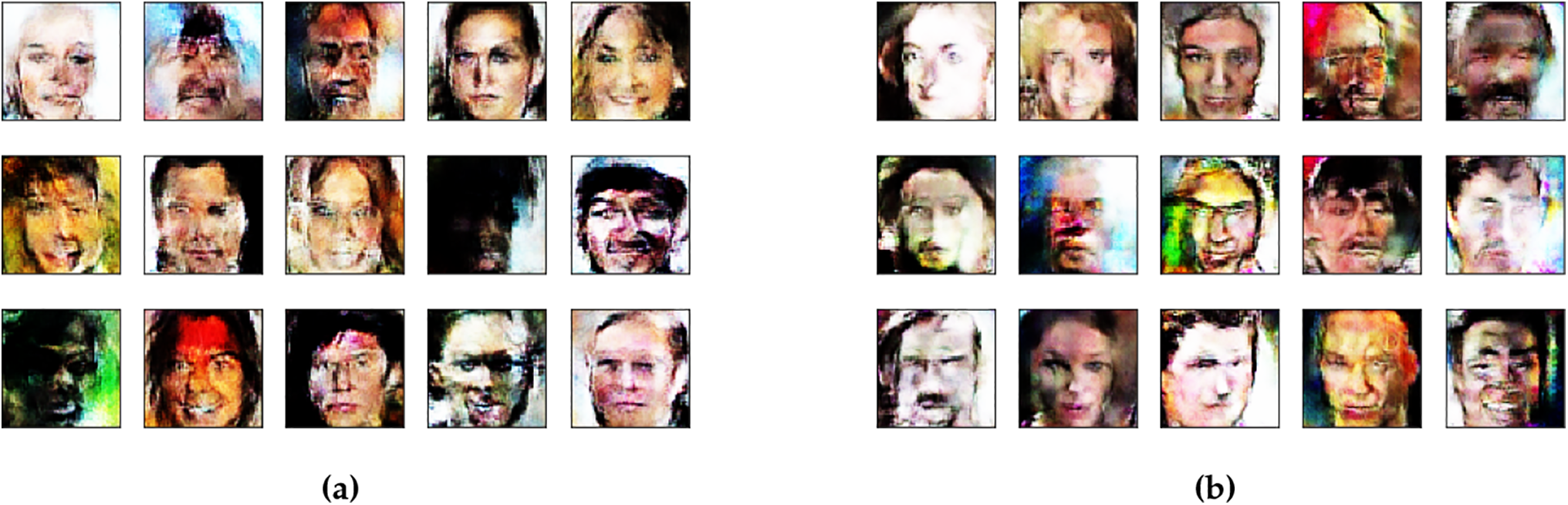

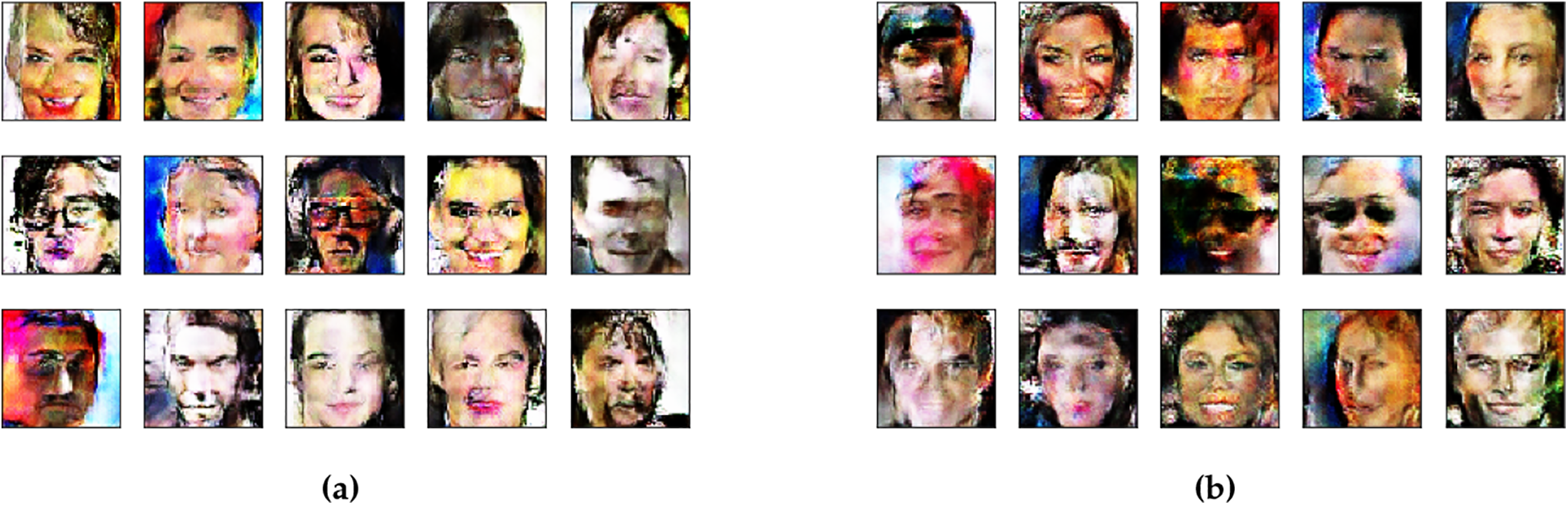

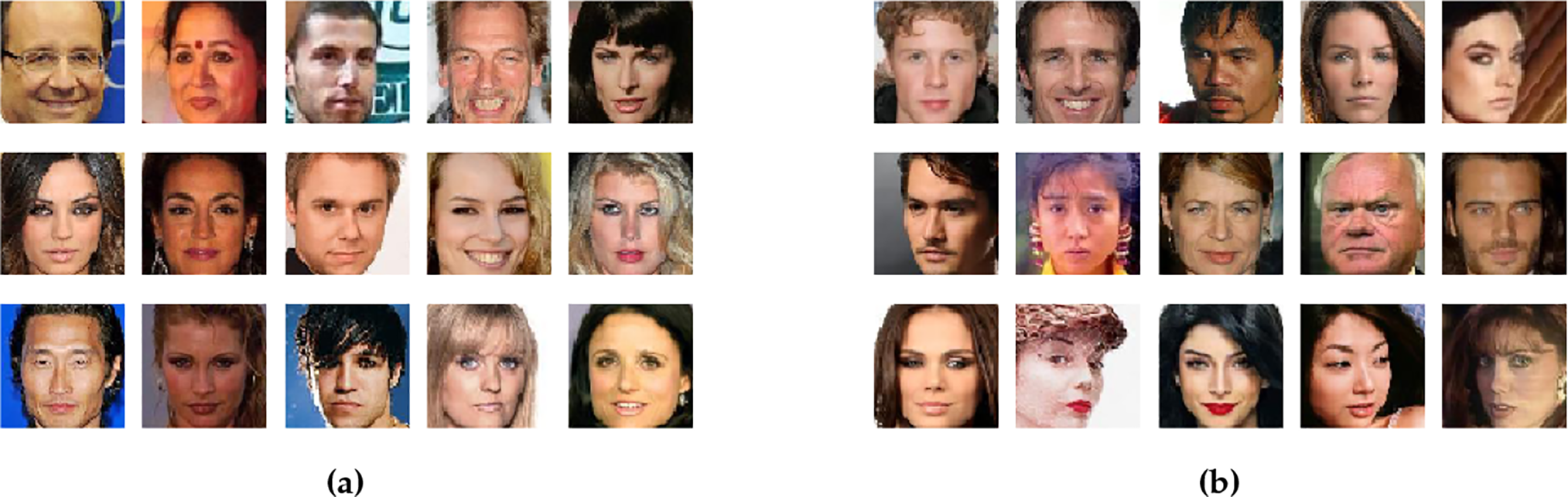

This section of the manuscript presents the experimental outcomes of the proposed SRGAN with PAM module for human face generation. The model was evaluated over multiple epochs, with the outcomes of each epoch analyzed in terms of the loss metric. The corresponding generated images across the batches are presented in Figs. 6 to 13.

Figure 6: The generated Face Images at Epoch = 1, (a) SRGAN with PAM module, and (b) SRGAN without PAM module

Figure 7: The generated Face Images at Epoch = 20, (a) SRGAN with PAM module, and (b) SRGAN without PAM module

Figure 8: The generated Face Images at Epoch = 40, (a) SRGAN with PAM module, and (b) SRGAN without PAM module

Figure 9: The generated Face Images at Epoch = 60, (a) SRGAN with PAM module, and (b) SRGAN without PAM module

Figure 10: The generated Face Images at Epoch = 80, (a) SRGAN with PAM module, and (b) SRGAN without PAM module

Figure 11: The generated Face Images at Epoch = 100, (a) SRGAN with PAM module, and (b) SRGAN without PAM module

Figure 12: The generated Face Images at Epoch = 150, (a) SRGAN with PAM module, and (b) SRGAN without PAM module

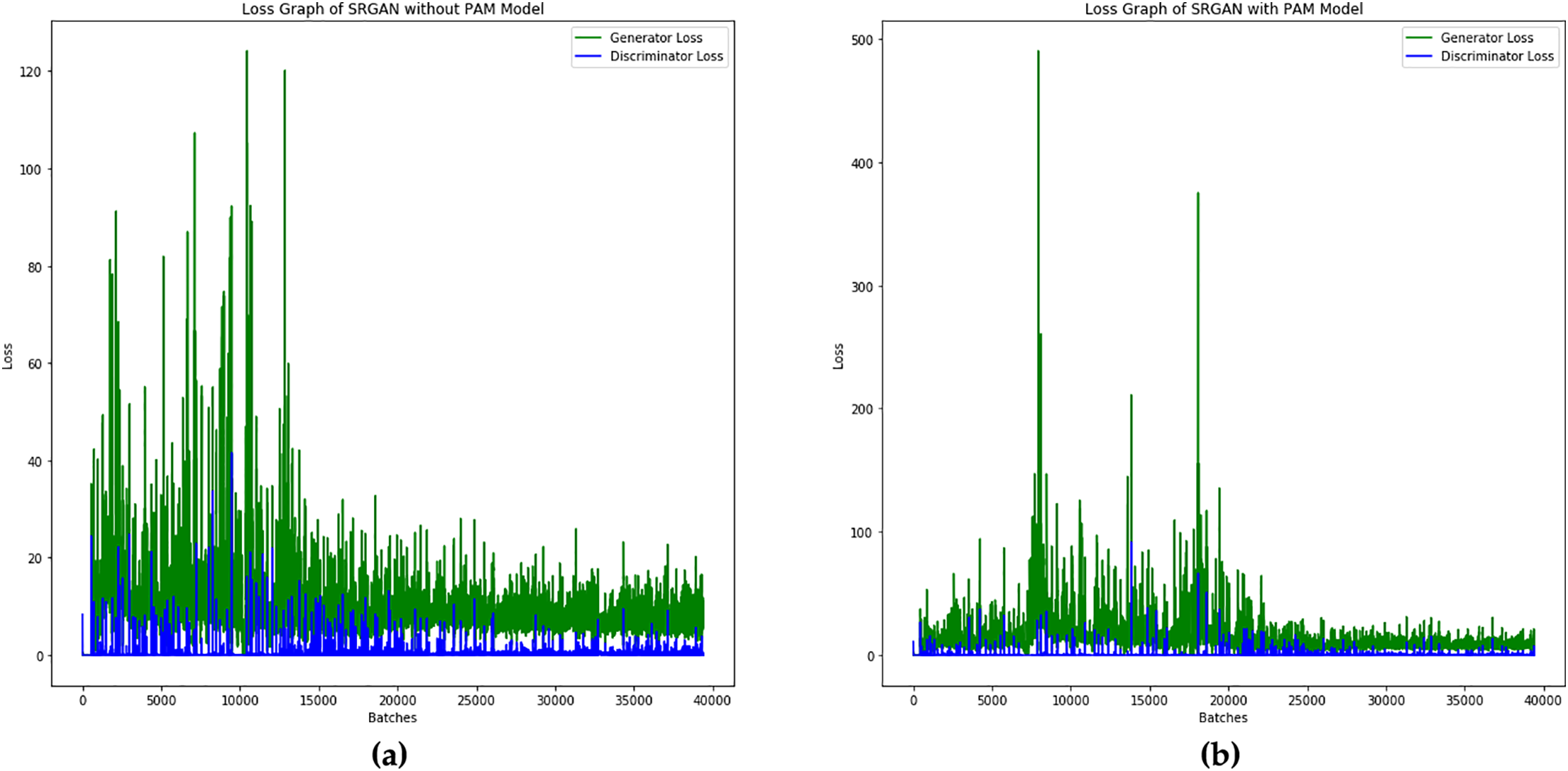

Figure 13: The graph represents the loss measures, (a) SRGAN without the PAM module, and (b) SRGAN with the PAM module

Additionally, the proposed model is assessed over the loss metric across batches. The corresponding graphs demonstrate the model’s performance, showing a consistent decrease in loss over the batches, indicating effective training and improved model performance over the batches.

The performance of the model is further evaluated using loss metrics. The generator aims to minimize perceptual loss by combining adversarial loss with content loss derived from pretrained perceptual networks. This approach ensures that the generated face images not only deceive the discriminator but also closely resemble the original images in terms of perceptual attributes. Meanwhile, the discriminator employs a hybrid loss that integrates traditional adversarial components with feature matching, improving its accuracy across various scales. Together, these sophisticated loss strategies facilitate the creation of higher-quality face images with enhanced detail. The Pyramid Attention Module (PAM) further optimizes feature extraction and spatial attention, enhancing the precision of image generation in the SRGAN with PAM.

The performance concerning loss metrics is evaluated both with and without the PAM module in the SRGAN for face image generation. The loss measures for the model with and without the PAM module are shown in Fig. 13.

From the loss graphs of the proposed model, it can be observed that the generator loss is generally higher than the discriminator loss, as the generated facial images are legible. As the clarity of the generated facial images improves, the generator loss is expected to decrease. Notably, the loss consistently declines over the epochs, reflecting the model’s ability to generalize effectively. The SRGAN with PAM exhibits significantly lower loss values compared to the model without PAM, highlighting the effectiveness of the attention mechanism.

However, if the generator becomes too proficient during training, the discriminator may struggle to distinguish between generated and real images, resulting in low discriminator loss [30]. Conversely, if the discriminator performs well, the generator may face difficulties in learning, leading to higher generator loss.

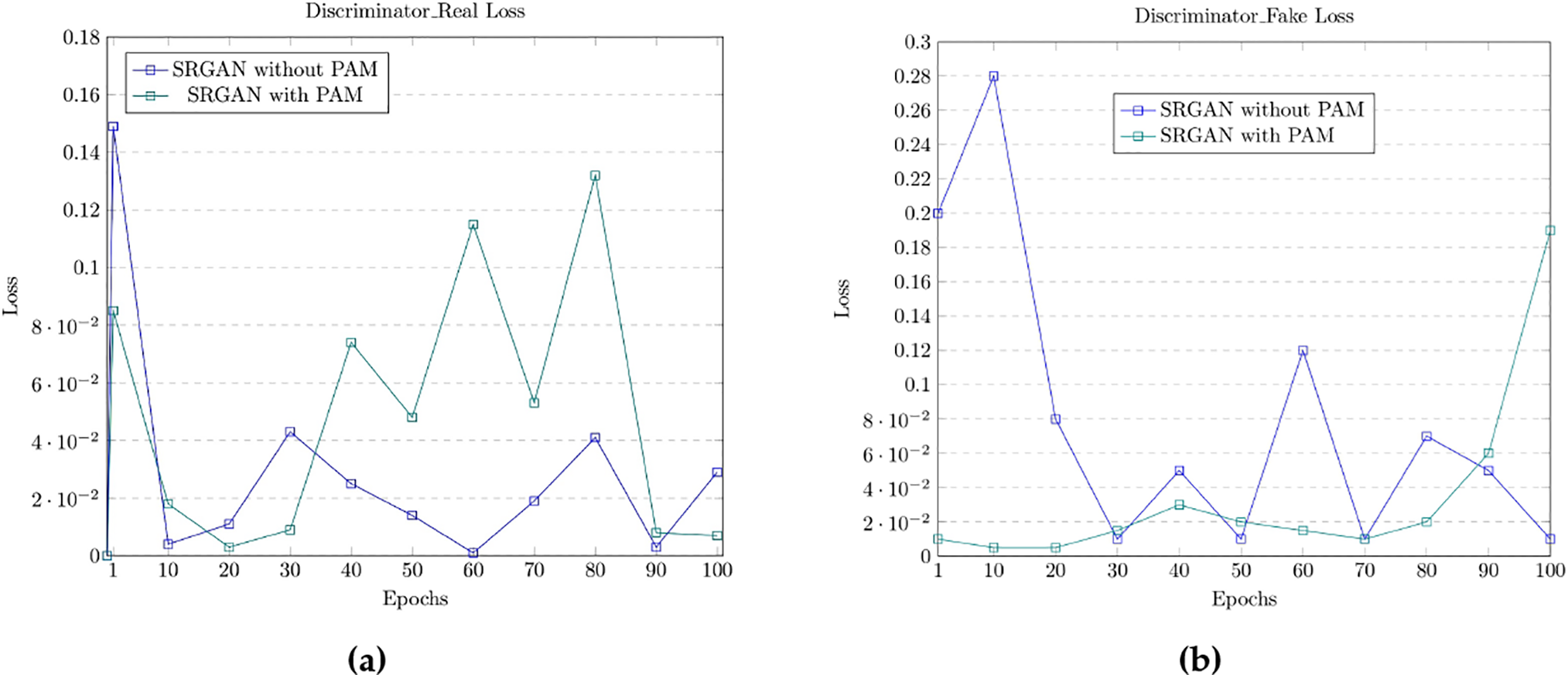

The discriminator loss for real and fake images is summarized in Tables 4 and 5. The discriminator’s output for actual data samples from the training dataset is denoted as

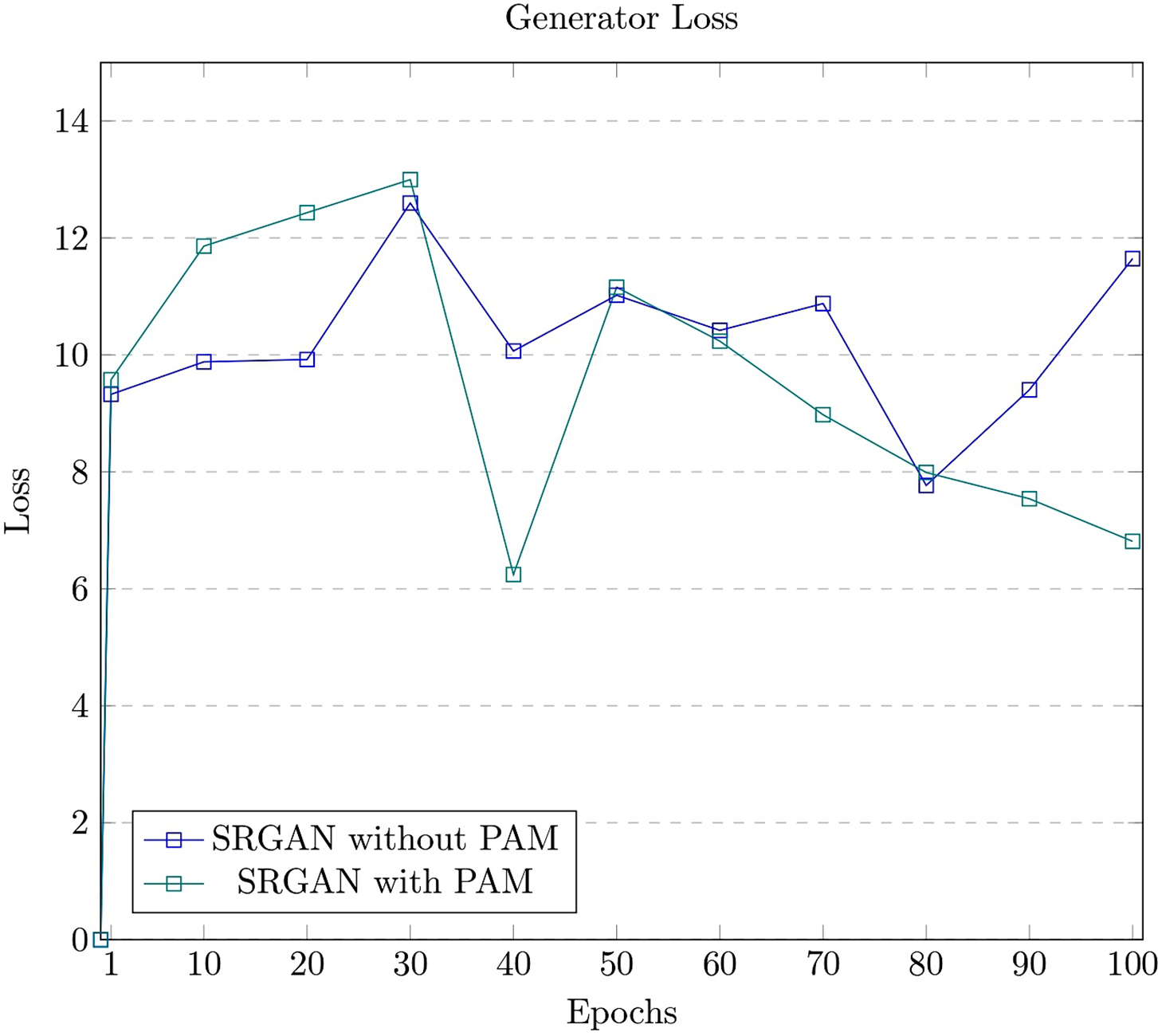

The generator loss, denoted as

The proposed model is also evaluated with and without the PAM module, and the results are presented in Table 4. The corresponding graphs for all losses, including generator and discriminator losses, are displayed in Figs. 14 and 15.

Figure 14: The graph presents the loss measures of the generator module image

Figure 15: The graph presents the loss measures of the discriminator module, (a) Associated with a real image, and (b) Associated with a fake image

The summary of discriminator and generator loss over 100 epochs is being aggregated and presented in Table 5. It can be observed that the SRGAN with PAM has outperformed the model without the PAM module.

The loss graphs for the generator and discriminator modules demonstrate the significant impact of the PAM module on the performance of the SRGAN model. The inclusion of the PAM module enhances the processing of features across multiple scales, facilitating better aggregation of contextual information. Notably, the loss in the discriminator module suggests that the model struggles to generalize effectively between original and generated images. Conversely, lower loss in the generator module indicates improved precision in the generated images, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

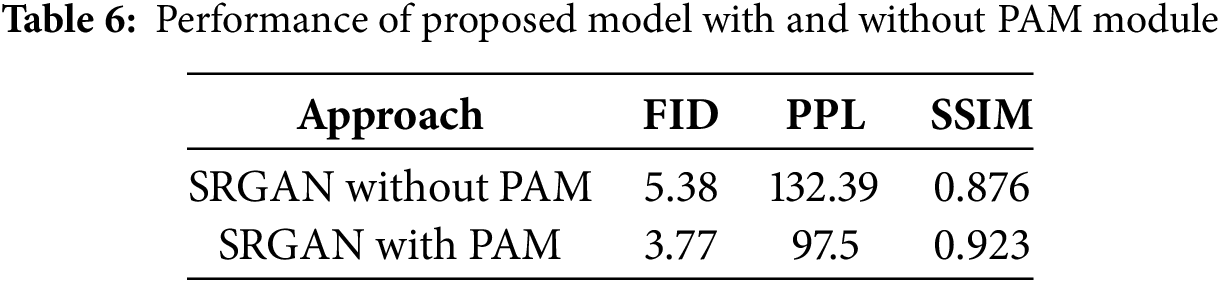

The proposed SRGAN with PAM module is being evaluated with other standard metrics for evaluating the performance of the model, Which includes the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) score, perceptual path length (PPL), and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) for evaluating the performance of the proposed model. FID evaluates both the quality and diversity of generated images by measuring how close the synthetic image distribution is to the real image distribution in the feature space. The corresponding formula for FID is presented in (14).

From the above equation,

Perceptual path length is the other crucial metric that is used in assessing the performance of the image-generating models. PPL measures how consistent the changes in the generated image are, relative to small changes in the latent input. Usually, PPL ensures model doesn’t suddenly jump from one face to another with minor changes in the input. The corresponding formula for PPL is shown in Eq. (15).

From the above equation, the notation

From the above equation, the notation

The proposed model is evaluated with regard to FID, PPL, and SSIM; the obtained results are presented in Table 6. The observed results are compared with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models like X2Face, Pix2pixHD, Multi-Scale Gradients for Generative Adversarial Networks (MSG-GAN), StyleGAN, Conditional GAN, CycleGAN [31], Diversified realistic face image generation GAN (DRFI), of Pose-Controllable Audio-Visual Syste (PC-AVS), and Facial Scene Representation Transformer (FSRT) as shown in Table 7. For some studies, for which the values are not obtained is identified as N/A.

The experimental results indicate that the proposed model has been effective, with loss values consistently decreasing over epochs. This trend demonstrates the model’s ability to learn progressively from the training data. Additionally, the quality of the generated images has improved over the epochs, with human faces becoming more discernible and realistic.

The spikes observed in the loss graphs are attributed to the raw dataset, as the images were acquired from various sources, and no data augmentation was performed on the original images used in the training process. Furthermore, the generator module strives to produce realistic images, while the discriminator attempts to distinguish fake images from real ones. This adversarial training dynamic often causes temporary oscillations in the loss values as each network improves, leading the other to adapt.

The proposed model could benefit from rigorous evaluation over additional epochs to enhance performance comprehensibility. A key limitation of this study is the evaluation in a limited number of training rounds. Future work could involve evaluating the model under varying hyperparameters, such as learning rate, optimizer, and activation functions, to identify optimal settings for generating realistic images.

The current study is conducted over the CelebA dataset, and thus, the evaluation of the proposed model is restricted to the specific distribution and features that are associated with this dataset. The model does not account for dynamic environmental conditions, such as variable lighting conditions, background noise, motion artifacts, pose, heterogeneity, and facial features, which are significant in synthesizing the human faces in real-time settings. Resultantly, the model’s ability for real-time facial synthesis and generalization across diverse conditions remains limited. Additionally, the evaluation is performed under standard hyperparameter configurations, without performing the hyperparameter tuning. A comprehensive hyperparameter optimization would further enhance the model’s generalizability and performance in the real-time scenario.

The current study focuses on generating high-resolution human face images using the Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network with a Pyramid Attention Module. The proposed model demonstrates the ability to generate high-quality human face images with reasonable accuracy. The model’s performance was evaluated using loss metrics and showed consistent improvement over the executed epochs. However, the study was limited to a relatively small number of epochs due to computational resource constraints. Future evaluations could extend the number of epochs to achieve more comprehensive performance insights. Additionally, the performance of generator and discriminator could be further assessed using alternative loss measures such as MinMax and Gradient Penalty losses.

Future research directions for the proposed model include enhancing feature engineering mechanisms to efficiently capture long-range dependencies, such as incorporating cross-modal attention. Improved data pre-processing techniques, including batch normalization, data augmentation, and semantic processing, could contribute to better results. Furthermore, integrating Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques could provide deeper insights into the feature engineering processes and improve the interpretability of the generator and discriminator models. Integrating more advanced attention mechanisms or combining the model with other deep learning techniques like transformers could enhance its performance even more. There’s also potential to apply the approach to other types of images beyond human faces, such as medical or satellite images, where fine detail is important. Additionally, reducing computational costs while maintaining image quality would make the model more practical for real-time applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (*MSIT) (No. 2018R1A5A7059549).

Author Contributions: Parvathaneni Naga Srinivasu, Sujatha Canavoy Narahari, and Muhammad Attique Khan have prepared the initial draft and have done the model coding. G. JayaLakshmi, and Hee-Chan Cho have performed the formal analysis, results interpretation, and evaluation. Byoungchol Chang has done the study conception, design, and funding. Victor Hugo C. de Albuquerque has performed the project administration, and outcome evaluation. All the authors have equally contributed in revising the document. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated. The dataset that is used in the current study is accessible in the link https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/jessicali9530/celeba-dataset (accessed on 18 May 2025).

Ethics Approval: The authors declare that they do not have requested for the ethical approval for this research as there are not human participants, but a published dataset is used.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bose A, Aarabi P. Virtual fakes: deepfakes for virtual reality. In: 2019 IEEE 21st International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP); 2019 Sep 27–29; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. doi:10.1109/MMSP.2019.8901744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu W, Gu Y, Zhang K. Face generation using DCGAN for low computing resources. In: 2021 2nd International Conference on Big Data & Artificial Intelligence & Software Engineering (ICBASE); 2021 Sep 24–26; Zhuhai, China. p. 377–82. doi:10.1109/ICBASE53849.2021.00076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Islam A, Belhaouari SB. Fast and efficient image generation using variational autoencoders and K-nearest neighbor oversampling approach. IEEE Access. 2023;11:28416–26. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3259236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Paiano M, Martina S, Giannelli C, Caruso F. Transfer learning with generative models for object detection on limited datasets. Mach Learn Sci Technol. 2024;5(3):035041. doi:10.1088/2632-2153/ad65b5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li P, Yu Z, Zhan Y. Deep relational self-Attention networks for scene graph generation. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2022;153(1):200–6. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2021.12.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cao Z, Shi L, Wang W, Niu S. Facial pose and expression transfer based on classification features. Electronics. 2023;12(8):1756. doi:10.3390/electronics12081756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Pavate A, Bansode R, Srinivasu P, Shafi J, Choi J, Ijaz M. Associative discussion among generating adversarial samples using evolutionary algorithm and samples generated using GAN. IEEE Access. 2023;11(1):143757–70. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3343754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Maqsood M, Mumtaz R, Haq I, Shafi U, Zaidi S, Hafeez M. Super resolution generative adversarial network (SRGANs) for wheat stripe rust classification. Sensors. 2021;21(23):7903. doi:10.3390/s21237903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Mei Y, Fan Y, Zhang Y, Yu J, Zhou Y, Liu D, et al. Pyramid attention network for image restoration. Int J Comput Vis. 131:1–19. doi:10.1007/s11263-023-01843-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Phanindra R, Raju N, Vivek T, Chandrasekharan J. Face model generation using deep learning. In: IOT with smart systems. Singapore: Springer; 2022. p. 181–9. [Google Scholar]

11. Liu Z, Luo P, Wang X, Tang X. Deep learning face attributes in the wild. In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 13–16; Santiago, Chile. p. 3730–8. [Google Scholar]

12. Lisanti G, Giambi N. Conditioning diffusion models via attributes and semantic masks for face generation. Comput Vis Image Understand. 2024;244:104026. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2024.104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li Z, Zhang S, Zhang Z, Meng Q, Liu Q, Zhou H. Attention guided domain alignment for conditional face image generation. Comput Vis Image Understand. 2023;234:103740. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2023.103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pries J, Bhulai S, Van der Mei R. Evaluating a face generator from a human perspective. Mach Learn Appl. 2022;10:100412. doi:10.1016/j.mlwa.2022.100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Krishna Katta V, Kapalavai H, Mondal S. Generating new human faces and improving the quality of images using generative adversarial networks(GAN). In: 2023 2nd International Conference on Edge Computing and Applications (ICECAA); 2023 Jul 19–21; Namakkal, India. p. 1647–52. [Google Scholar]

16. Liu B, Lv J, Fan X, Luo J, Zou T. Application of an improved DCGAN for image generation. Mob Inf Syst. 2022;2022:9005552. doi:10.1155/2022/9005552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Aggarwal A, Mittal M, Battineni G. Generative adversarial network: an overview of theory and applications. Int J Inform Manag Data Insig. 2021;1(1):100004. doi:10.1016/j.jjimei.2020.100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhao J, Xiong L, Li J, Xing J, Yan S, Feng J. 3D-aided dual-agent GANs for unconstrained face recognition. IEEE Transact Pattern Analy Mach Intelli. 2019;41:2380–94. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2858819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Faria F, Carneiro G. Why are generative adversarial networks so fascinating and annoying? In: 2020 33rd SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images (SIBGRAPI); 2020 Nov 7–10; Recife/Porto de Galinhas, Brazil. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/SIBGRAPI51738.2020.00009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu Y, Zhou Y, Liu X, Dong F, Wang C, Wang Z. Wasserstein GAN-based small-sample augmentation for new-generation artificial intelligence: a case study of cancer-staging data in biology. Engineering. 2019;5(1):156–63. doi:10.1016/j.eng.2018.11.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dixe S, Leite J, Fonseca J, Borges J. BigGAN evaluation for the generation of vehicle interior images. Procedia Comput Sci. 2022;204:548–57. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.08.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lu Y, Gu B, Ouyang W, Liu Z, Zou F, Hou J. LSG-GAN: latent space guided generative adversarial network for person pose transfer. Know-Based Syst. 2023;278:110852. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yin H, Xiao J, Chen H. CSPA-GAN: a cross-scale pyramid attention GAN for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Transact Instrument Measur. 2023;72:5027011. doi:10.1109/tim.2023.3317932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lenatti M, Narteni S, Paglialonga A, Rampa V, Mongelli M. Dual-view single-shot multibox detector at urban intersections: settings and performance evaluation. Sensors. 2023;23(6):3195. doi:10.3390/s23063195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Barron J. A general and adaptive robust loss function. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 4326–34. [Google Scholar]

26. Hu X, Liu X, Wang Z, Li X, Peng W, Cheng G. RTSRGAN: real-time super-resolution generative adversarial networks. In: 2019 Seventh International Conference on Advanced Cloud and Big Data (CBD); 2019 Sep 21–22; Suzhou, China. p. 321–6. [Google Scholar]

27. Park H, Paik J. Pyramid attention upsampling module for object detection. IEEE Access. 2022;10:38742–9. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3166928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yeom T, Gu C, Lee M. DuDGAN: improving class-conditional GANs via dual-diffusion. IEEE Access. 2024;12:39651–61. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3372996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang N, Li J, Li Y, Du Y. Global attention pyramid network for semantic segmentation. In: 2019 Chinese Control Conference (CCC); 2019 Jul 27–30; Guangzhou, China. p. 8728–32. [Google Scholar]

30. Li Y, Xiao N, Ouyang W. Improved generative adversarial networks with reconstruction loss. Neurocomputing. 2019;323:363–72. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2018.10.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang Z, Tao H, Zhou H, Deng Y, Zhou P. A content-style control network with style contrastive learning for underwater image enhancement. Multimedia Syst. 2025;31(1):60. doi:10.1007/s00530-024-01642-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wiles O, Koepke S, Zisserman A. X2Face: a network for controlling face generation using images, audio, and pose codes. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2018: 15th European Conference. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2018. p. 690–706. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01261-8_41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang TC, Liu MY, Zhu JY, Tao A, Kautz J, Catanzaro B. High-resolution image synthesis and semantic manipulation with conditional GANs. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 8798–807. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01261-8_41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zakharov E, Shysheya A, Burkov E, Lempitsky V. Few-shot adversarial learning of realistic neural talking head models. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 9458–67. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Karnewar A, Wang O. MSG-GAN: multi-scale gradients for generative adversarial networks. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 7796–805. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Karras T, Laine S, Aittala M, Hellsten J, Lehtinen J, Aila T. Analyzing and improving the image quality of StyleGAN. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 8107–16. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lu Y, Tai YW, Tang CK. Attribute-guided face generation using conditional CycleGAN. In: Ferrari V, Hebert M, Sminchisescu C, Weiss Y, editors. Computer vision—ECCV 2018. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 293–308. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01258-8_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Deng Y, Yang J, Chen D, Wen F, Tong X. Disentangled and controllable face image generation via 3D imitative-contrastive learning. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 5153–62. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kumar L, Singh DK. Diversified realistic face image generation GAN for human subjects in multimedia content creation. Comput Anim Virtual Worlds. 2024;35(2):e2232. doi:10.1002/cav.2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang Y, He W, Li M, Tian K, Zhang Z, Cheng J, et al. Learning to data-efficiently generate audio-driven lip-synchronized talking face with high definition. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2022 May 22–27; Singapore. p. 4848–52. [Google Scholar]

41. Rochow A, Schwarz M, Behnke S. FSRT: facial scene representation transformer for face reenactment from factorized appearance, head-pose, and facial expression features. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 7716–26. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.00737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools