Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

CD-AKA-IoV: A Provably Secure Cross-Domain Authentication and Key Agreement Protocol for Internet of Vehicle

1 School of Artificial Intelligence/School of Future Technology, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

3 College of Computer Science and Engineering, Shandong University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266590, China

2 School of Computer Science, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

4 Department of Mathematics, Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut, 250004, India

* Corresponding Author: Chien-Ming Chen. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1715-1732. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065560

Received 16 March 2025; Accepted 19 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

With the rapid development and widespread adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) technology, the innovative concept of the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) has emerged, ushering in a new era of intelligent transportation. Since vehicles are mobile entities, they move across different domains and need to communicate with the Roadside Unit (RSU) in various regions. However, open environments are highly susceptible to becoming targets for attackers, posing significant risks of malicious attacks. Therefore, it is crucial to design a secure authentication protocol to ensure the security of communication between vehicles and RSUs, particularly in scenarios where vehicles cross domains. In this paper, we propose a provably secure cross-domain authentication and key agreement protocol for IoV. Our protocol comprises two authentication phases: intra-domain authentication and cross-domain authentication. To ensure the security of our protocol, we conducted rigorous analyses based on the ROR (Real-or-Random) model and Scyther. Finally, we show in-depth comparisons of our protocol with existing ones from both security and performance perspectives, fully demonstrating its security and efficiency.Keywords

With the Internet of Things (IoT) technology and artificial intelligence continuing to evolve and gain popularity, the field of Internet of Vehicles (IoV) [1,2] has gained significant prominence. IoV enables real-time monitoring and early warning of traffic information through data interaction and information sharing between vehicles and infrastructure, reducing the occurrence of traffic accidents. In the IoV environments, on-board units (OBU) installed in vehicles play a crucial role in exchanging messages with roadside units (RSU) deployed on both sides of the road. RSU can transmit the collected messages to passing vehicles to provide real-time traffic information. This information exchange enables vehicles to promptly identify the traffic situations and take necessary measures.

The open nature of the IoV makes messages transmitted over public channels highly susceptible to becoming targets for attackers, posing risks of interception, tampering, and eavesdropping [3–5]. Moreover, attackers can maliciously impersonate legitimate vehicles. This vulnerability jeopardizes communication between vehicles and the RSU, and even potentially compromises users’ privacy [6–8]. As a result, ensuring the communication security of vehicles and RSUs in the IoV environments becomes imperative. To address this concern, researchers have proposed various authentication and key agreement (AKA) protocols [9–11] to enhance the security of communications between vehicles and RSUs.

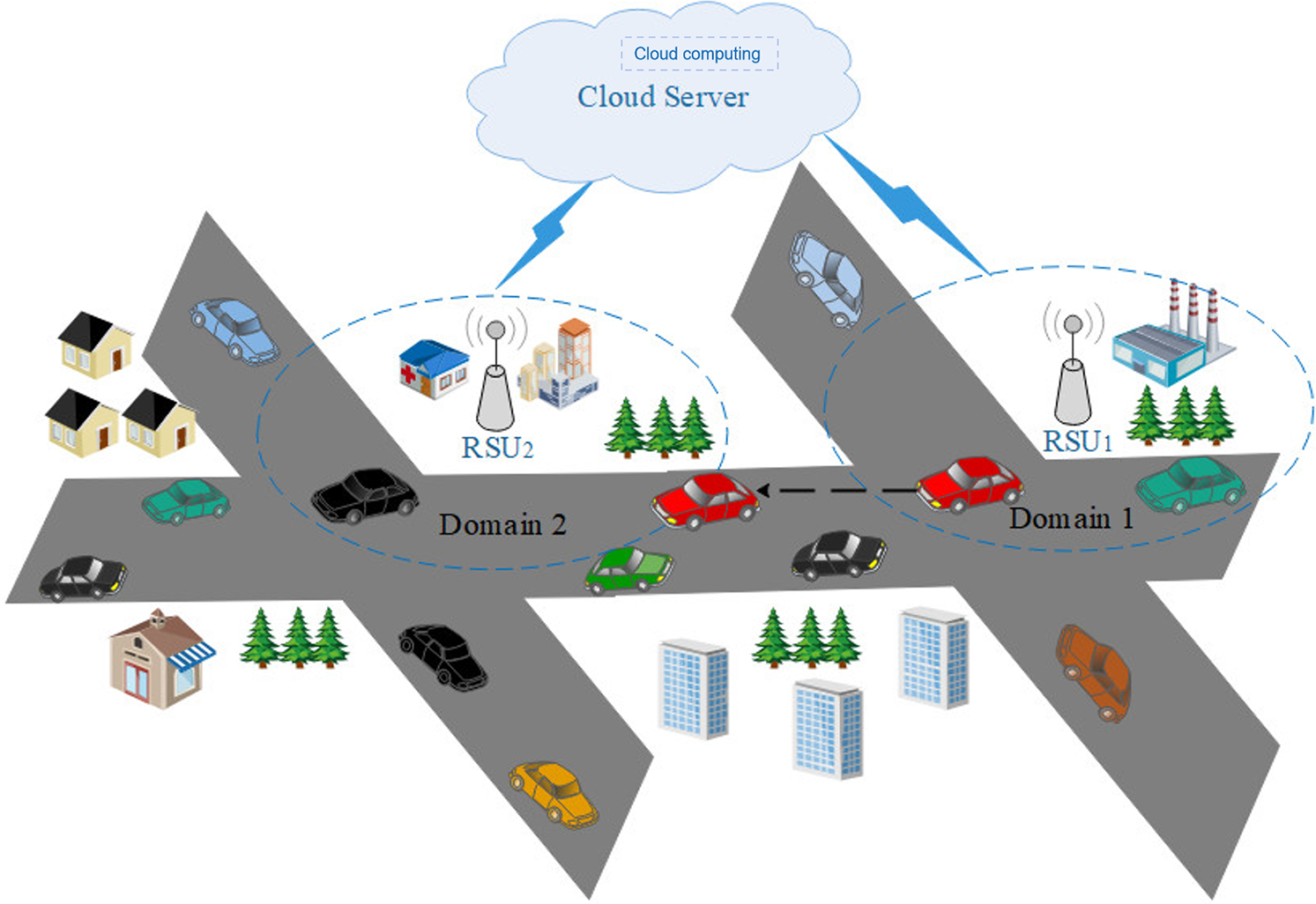

However, when vehicles move from one domain to another, cross-domain authentication will be a great challenge. Fig. 1 shows the frequently employed cross-domain architecture of the IoV. This architecture comprises three entities: vehicle, RSU, and cloud server (CS). The CS is in charge of registering both vehicles and RSUs, and helps them in the domain to achieve authentication. In recent years, researchers have conducted in-depth research in the IoV, dedicating significant efforts to addre ssing the challenges of cross-domain authentication. Xu et al. [12] devised an authentication protocol aimed at enhancing secure communication among diverse vehicle networks operating within various domains. Yang et al. [13] proposed a multi-domain vehicle authentication architecture based on blockchain technology, which effectively enables cross-domain information sharing among multiple management domains by establishing a distributed trust mechanism. Yu et al. [14] designed an innovative handover authentication protocol that utilizes blockchain to record vehicle information and verify vehicle legitimacy. To address the vulnerability of vehicles to physical attacks, Jiang et al. and Babu et al. [15,16] deployed physically unclonable functions (PUF) [17] in vehicles. Yan et al. [18] devised a certificateless group handover authentication protocol within a 5G vehicular network environment. Chen et al. [19] presented a key transfer authentication protocol that employs confidential computing environments. Their protocol includes a key transmission phase that facilitates the secure exchange of keys between different RSUs within the same fog node (FN) and different RSUs in distinct FNs.

Figure 1: Cross-domain architecture in the IoV

Currently, there is a scarcity of AKA protocols in IoV to ensure secure cross-domain authentication. To enable secure communication when vehicles cross domains, we propose a cross-domain authentication protocol for vehicles in this paper. Building upon the architecture depicted in Fig. 1, we design intra-domain authentication and cross-domain authentication for vehicles. In our design, when a vehicle within a specific domain intends to move to another domain, the cross-domain request needs to be transmitted to the RSU in the destination domain to ensure cross-domain authentication. With the assistance of the CS, the RSU in the intra-domain can transmit the related cross-domain information about the vehicle to the RSU in the cross-domain. Upon receiving the message, the RSU (cross-domain) searches its database and determines the communication status with the vehicle. If it is the first communication between the vehicle and the RSU (cross-domain), the RSU will request the information of the vehicle from the CS. Otherwise, the vehicle will communicate directly with the RSU (cross-domain). Finally, they can authenticate each other and establish a session key for further encrypting transmitted messages using symmetric encryption. Furthermore, we conducted a systematic analysis and validation of the security of our protocol in the Real-or-Random (ROR) model and Scyther, a security validation tool. The results show that our protocol is secure and resistant to several known attacks. Through a comprehensive comparative analysis of security and performance with other protocols, the results indicate that our protocol has both higher security and performance. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

1. We propose a provably secure cross-domain authentication protocol for vehicles in IoV environments, which supports secure communication for both intra-domain and cross-domain.

2. We design a handover mechanism that allows the RSU (cross-domain) to determine whether to authenticate vehicles directly or request assistance from the CS.

3. We adopt a two-phase authentication to reduce computation costs by avoiding repeated CS involvement in cross-domain authentication.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 elaborates on the attacker model and protocol design goals, Section 3 presents our proposed protocol, Section 4 provides the security analysis of the protocol, Section 5 compares the performance of the protocols, and Section 6 provides a summary.

2 System Model, Attacker Model and Design Goals

In this section, we provide a comprehensive description of the system model and the attacker’s capabilities. Moreover, we outline the essential security requirements that must be fulfilled by a cross-domain authentication protocol.

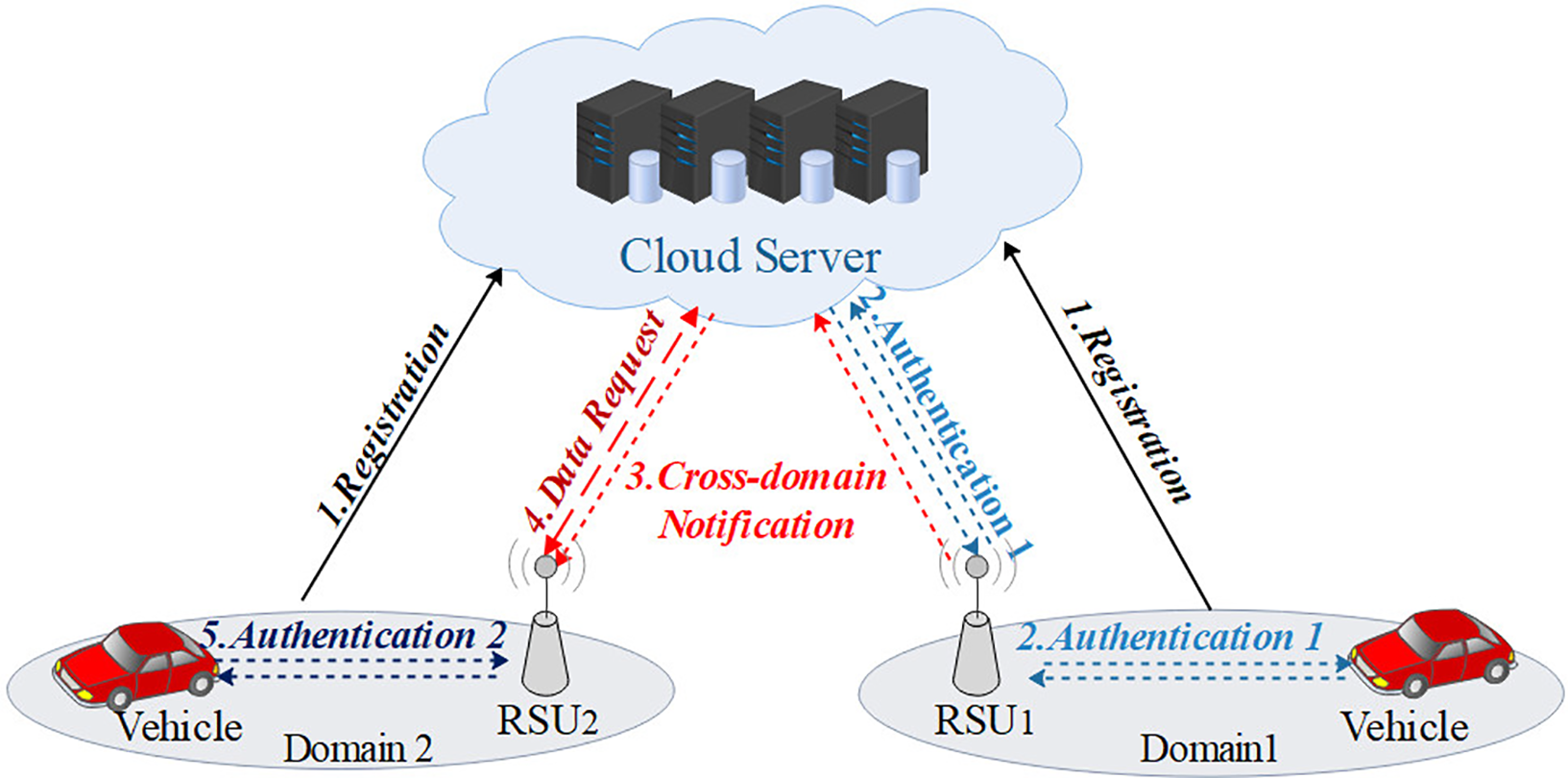

The proposed protocol consists of three entities: the vehicle

Figure 2: System model

1.

2.

3. CS: CS is the primary computing and storage resource provider. CS serves as the registration center and responds to the registration for

The cross-domain authentication of the vehicle from Domain 1 to Domain 2 is depicted in Fig. 2, and the comprehensive description of each step is provided below.

1. Initialization Phase: In this phase, CS pre-allocates unique identities and private keys for each

2. Intra-domain Authentication Phase: In this phase, when

3. Cross-domain Notification and Data Request Phase: Upon receiving this request,

4. Cross-domain Authentication Phase: When

In this paper, the capabilities of the attacker (

(1) The attacker

(2) The attacker

(3) The attacker

(4) The attacker

(5) The attacker

(6) The attacker

Based on the attacker model described above, our protocol is designed to meet the following security requirements:

(1) Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS): Even if an attacker

(2) Resistance to Impersonation Attacks: The protocol must prevent an attacker

(3) Resistance to Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attacks: The protocol should ensure that an attacker

(4) Resistance to Capture Attacks: Even if

(5) Mutual Authentication: This requirement necessitates mutual authentication between entities. In this process, the entities involved in the communications must present corresponding authentication credentials to ensure the legitimacy and trustworthiness.

(6) Anonymity: Entities maintain anonymity throughout the AKA process, ensuring that their true identity and other sensitive information remain undisclosed.

(7) Untraceability: It is impossible to trace or identify the identity or activities of

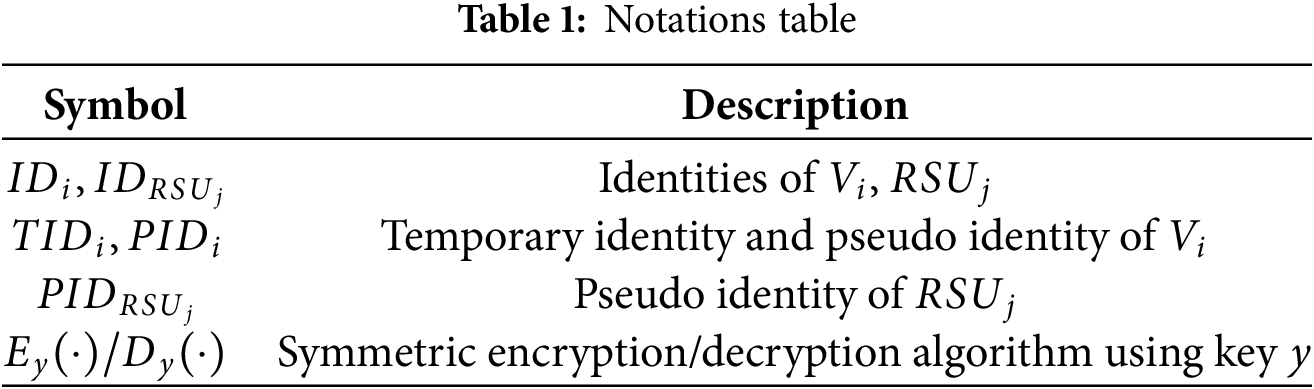

This section elaborates on the various phases of the proposed protocol. For ease of understanding, Table 1 lists the symbols used in this paper along with their specific meanings.

Before the registration phase, CS uses a random number generator to generate its master key K and selects a one-way anti-collision hash function denoted

The specific steps for this phase are elaborated in the following.

(1)

(2) After CS receives

(3) After

The specific steps for this phase are detailed below.

(1)

(2) After CS receives

(3) After receiving the message,

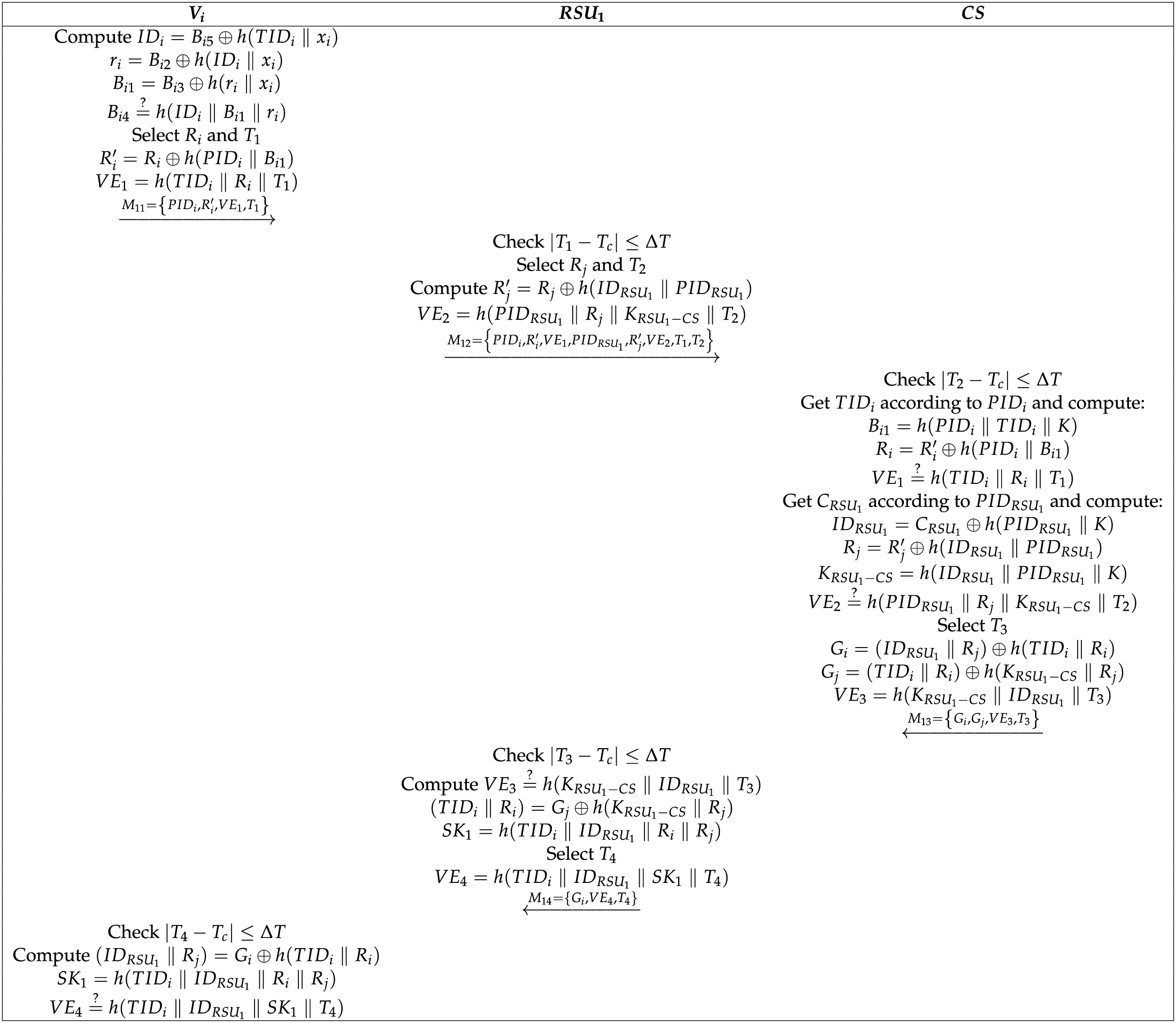

3.2 Intra-Domain Authentication Phase

In this phase,

Figure 3: Intra-domain authentication phase

(1)

(2) After receiving

(3) After receiving

(4) After receiving

(5) After receiving

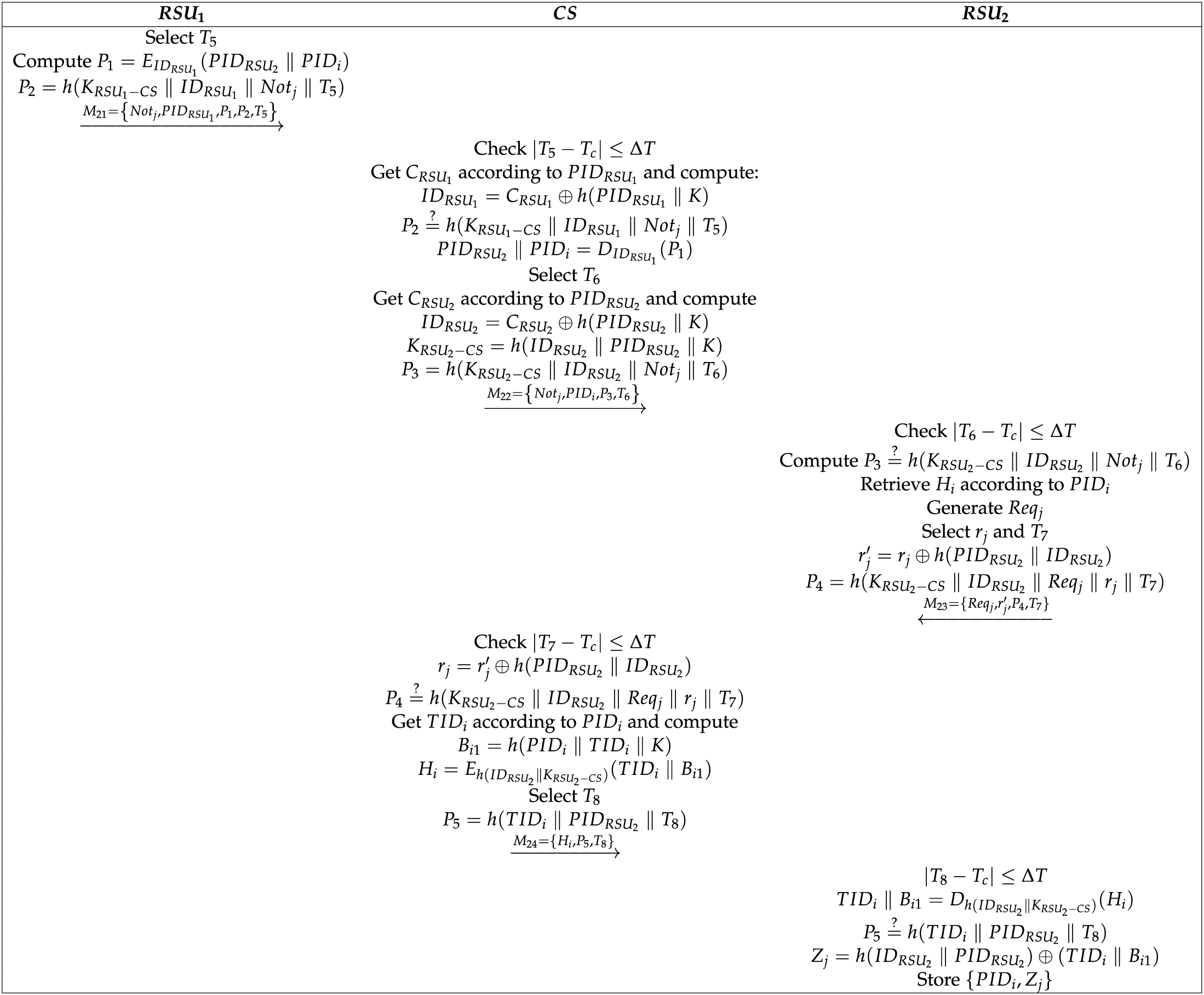

3.3 Cross-Domain Notification and Data Request Phase

In this phase, vehicle

Figure 4: Notification and data transmission phase

(1)

(2) After receiving

(3) After receiving

(4) After receiving

(5) After receiving

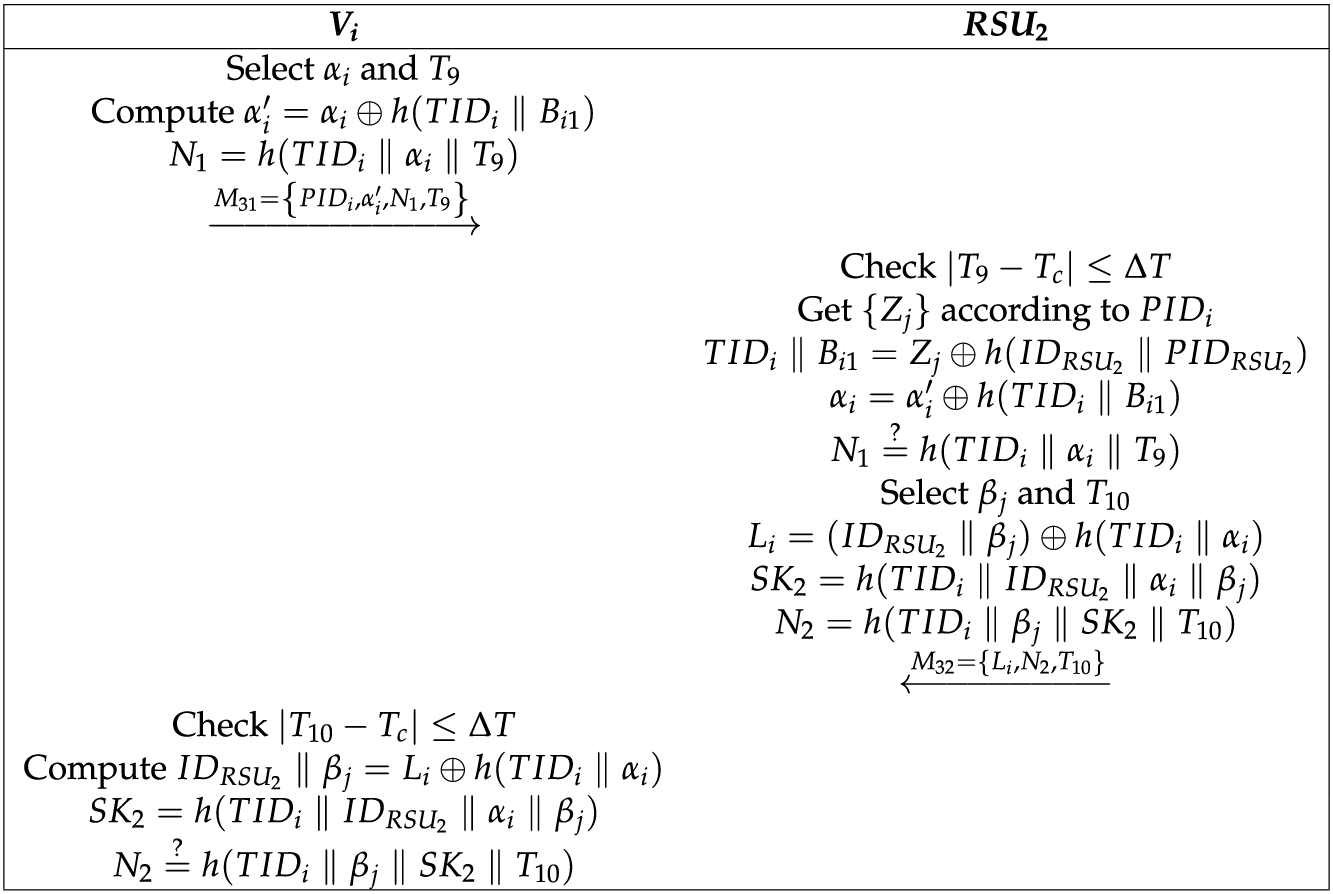

3.4 Cross-Domain Authentication Phase

When

The specific process is shown in Fig. 5, and the detailed description is as follows:

Figure 5: Cross-domain authentication phase

(1)

(2) After receiving

(3) After receiving

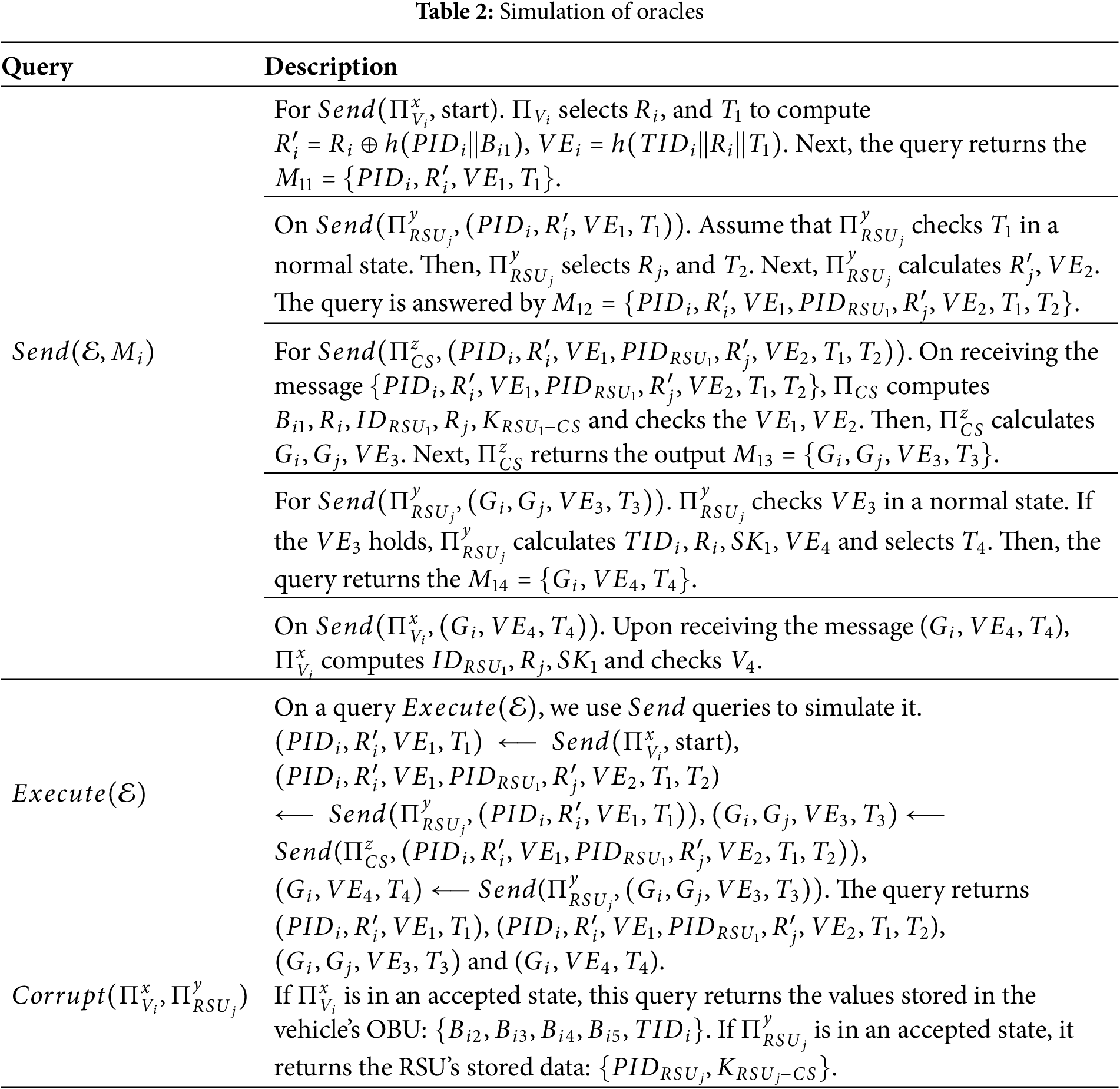

In this section, we focus on verifying the session key security under the ROR model, a well-established analytical framework referred to [17,25,26], for proving that an authentication protocol achieves the semantic security of the session key. The protocol involves three primary participants:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

Based on the ROR model, the security of our protocol can be proved by the following theorem.

Theorem 1: Based on the ROR model, the advantage of probabilistic polynomial-time

Proof: We define four rounds of games, denoted as

Finally,

Given the results from Eqs. (1) through (5), we obtain an upper bound of the advantage

Therefore, the overall advantage of adversary

where

□

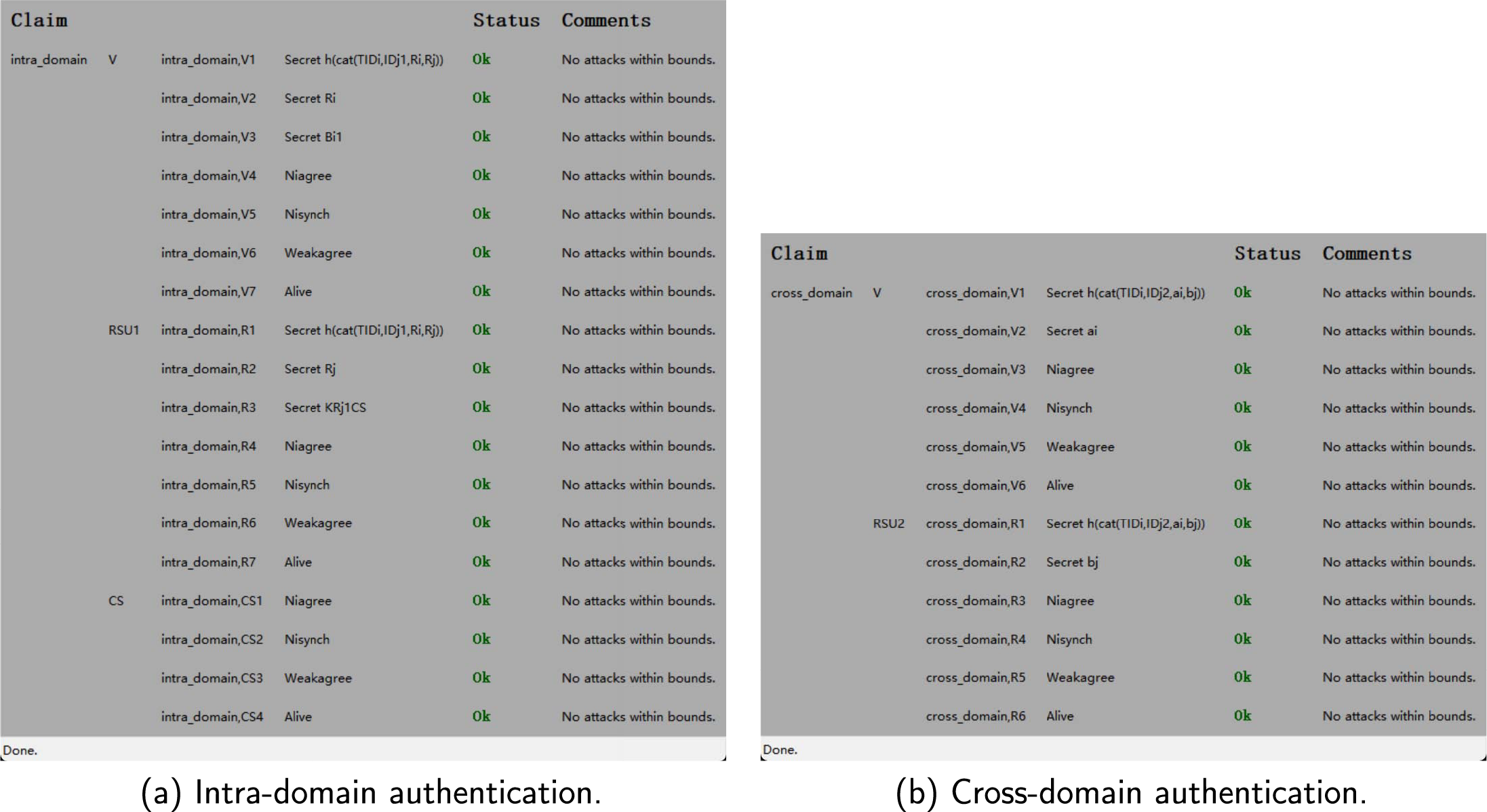

4.2 Security Verification Using Scyther

In this section, we adopt Scyther to model and analyze the security of the proposed protocol, including intra-domain and cross-domain authentications. Scyther is a security validation tool based on the D-Y model and performs symbolic execution to automatically detect potential attack paths within defined bounds. Here, we define a range of security claims, including the secrecy of session keys and authentication credentials, identity agreement, and aliveness of participating entities.

In Fig. 6a, it shows the results of the intra-domain authentication in which the entities include vehicle V, intra-domain roadside unit

Figure 6: Simulation results of Scyther

4.3 Anonymity and Untraceability

In our protocol, the real identity of

5 Security and Performance Comparisons

In this section, we conducted a comparative analysis of security and performance between the proposed protocol and authentication protocols in IoV [4,10–13,19].

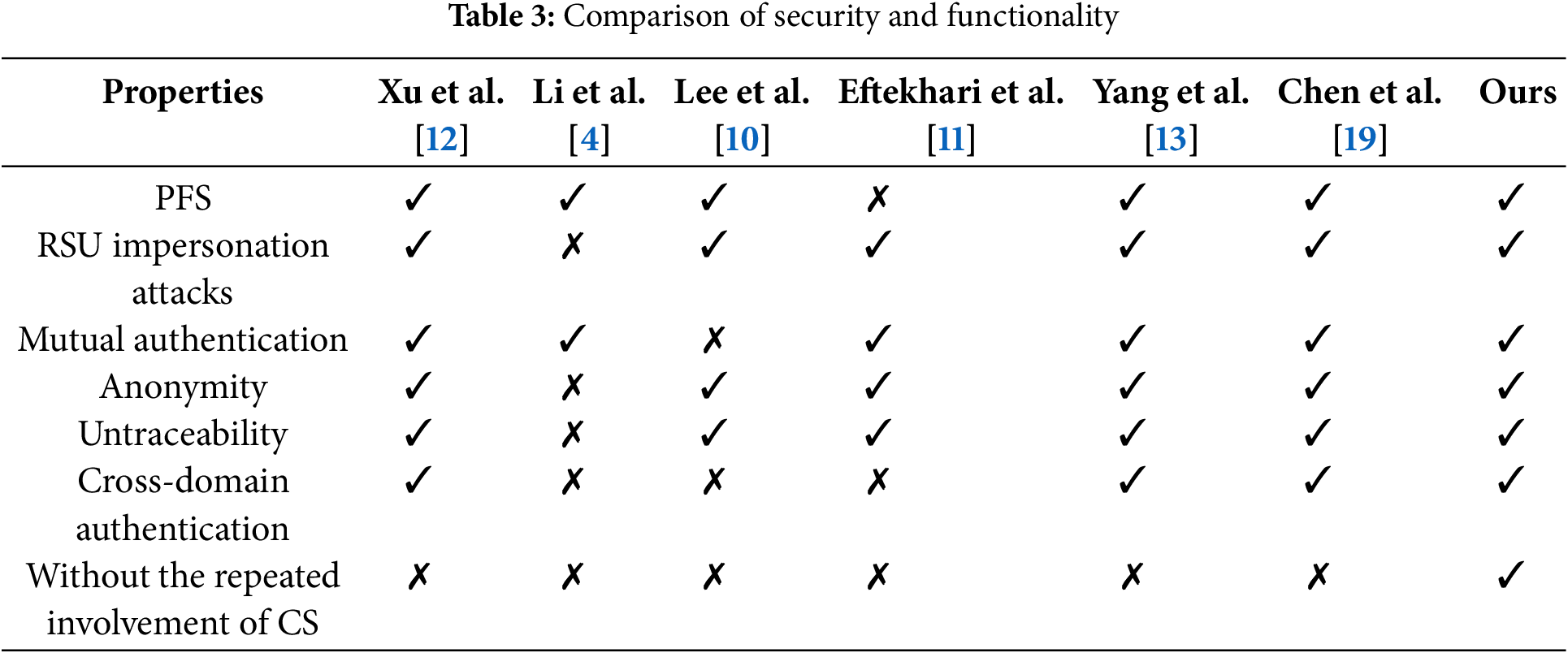

5.1 Security and Functionality Comparisons

The security and functionality comparison is summarized in Table 3. Note that ✗ indicates that the protocol cannot resist a particular type of attack or does not support the specified feature, while ✓ indicates that the protocol provides protection or support accordingly. It can be observed that Li et al.’s protocol [4] is vulnerable to RSU impersonation attacks and does not provide anonymity and untraceability. Lee et al.’s protocol [10] cannot withstand offline password guessing attacks and lacks mutual authentication. Eftekhar et al.’s protocol [11] violates PFS. On the other hand, Xu et al.’s, Yang et al.’s, Chen et al.’s protocols [12,13,19], and our protocol are resistant to common attacks and both achieve cross-domain authentication. In particular, we design a handover mechanism to reduce computation costs by avoiding the repeated involvement of the cloud server in cross-domain authentication.

5.2 The Comparison of Computational Costs

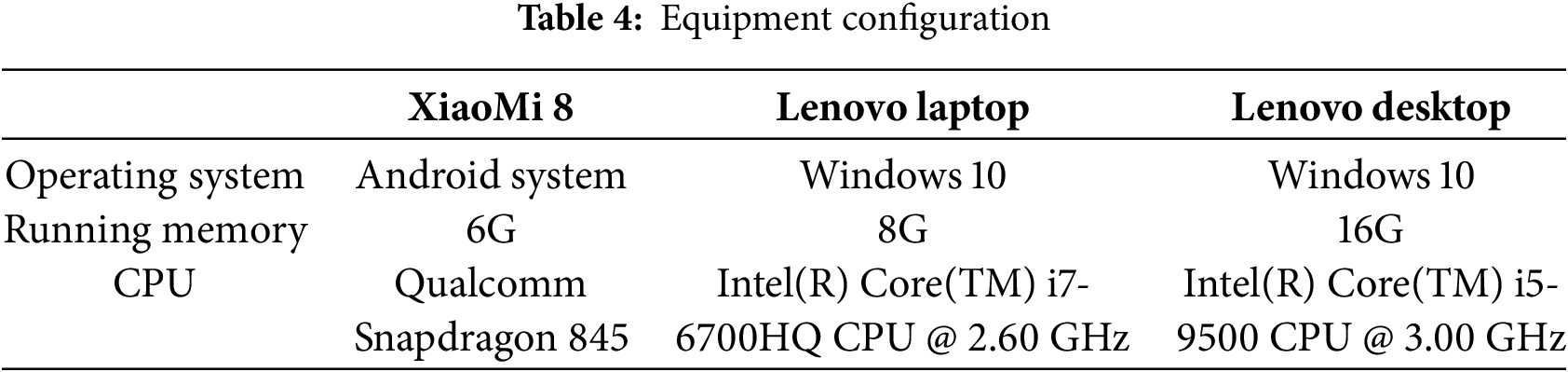

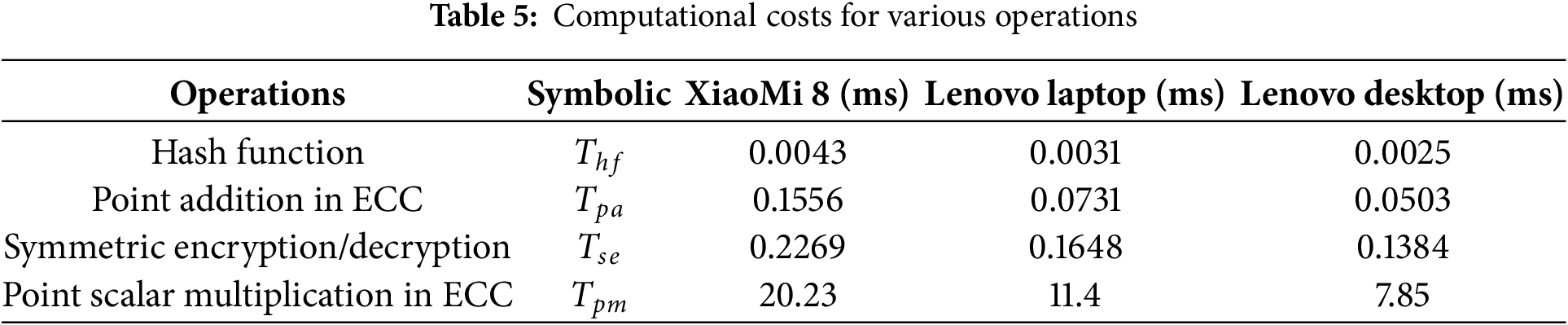

We are mainly concerned with comparing the computational costs that different protocols used in the authentication phase. Specifically, we conduct experiments to simulate the computational time required by each entity in the protocols in which the XiaoMi 8 smartphone is used to simulate

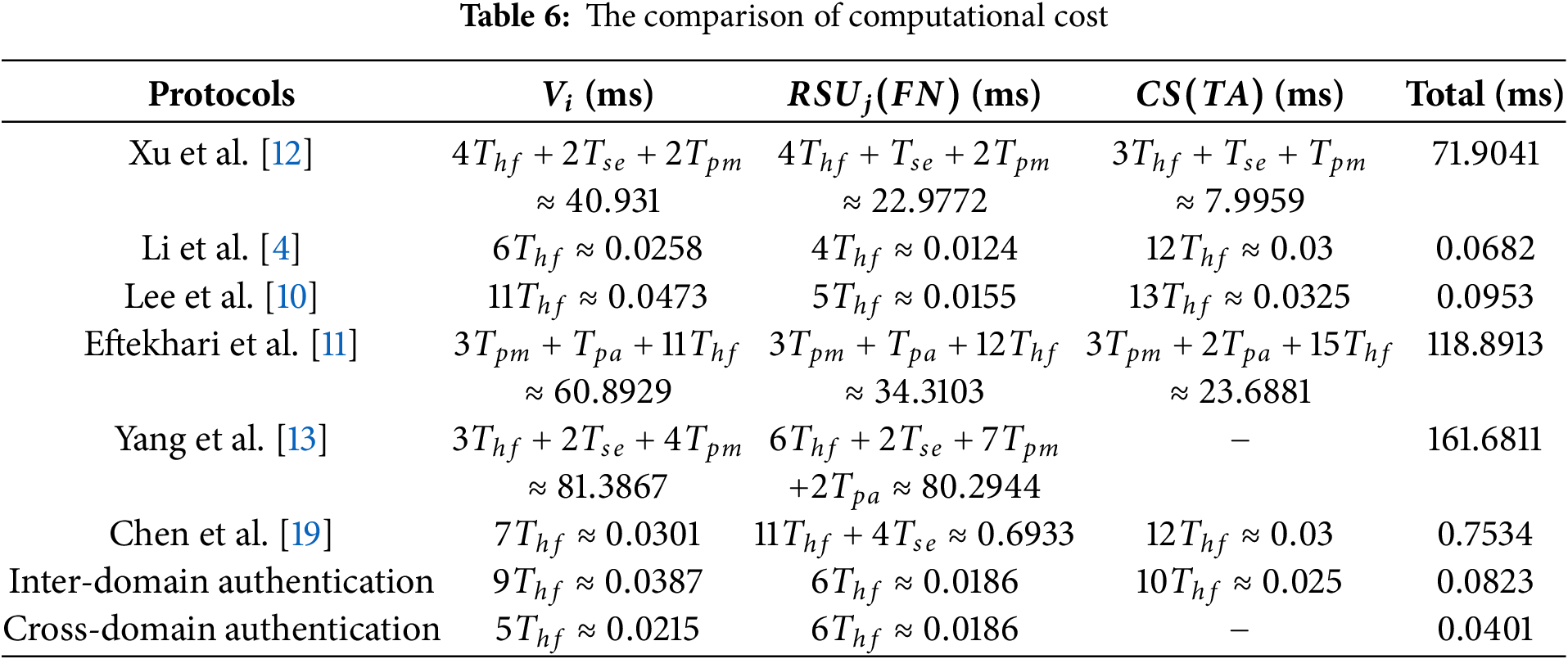

Table 6 illustrates the comparison of computational cost results. Yang et al.’s protocol [13] has the highest computational cost across all protocols, due to the use of point scalar multiplication operations in ECC within blockchain-based pseudonym handling and verification processes. Similarly, Eftekhari et al.’s protocol [11] also demonstrates high costs, especially for

In the cross-domain authentication phase of our protocol, it achieves the lowest computational cost in

5.3 The Comparison of Communicational Costs

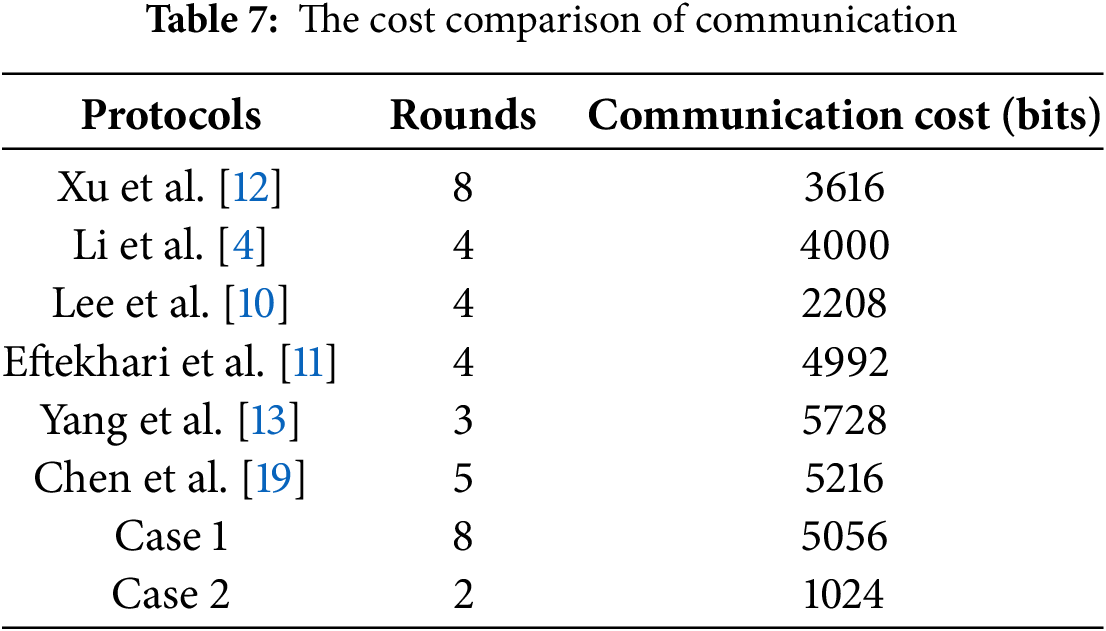

We defined the following length of parameters used to evaluate communication costs: identity |ID|, ciphertext of symmetric encryption |E|, random number |R|, timestamp |T|, hash function |H|, and point |P| as 160, 256, 160, 32, 256, and 320 bits, respectively.

As our protocol consists of two authentication phases, we divided the communication cost into two cases. In case 1 (Inter-domain authentication + notification and data transmission), the transmitted messages comprise

Table 7 illustrates the comparative results. It can be observed that Yang et al.’s protocol [13] incurs the highest communication cost due to its blockchain-based pseudonym exchange among all protocols. In our protocol, Case 1 involves 8 rounds of communications. However, this case occurs only once for the same

It is noteworthy that Case 2 significantly reduces communication overhead, outperforming all compared protocols under similar conditions. Through the joint analysis of computational and communicational costs, we claim that our proposed protocol achieves higher performance while maintaining higher security, particularly in cross-domain authentication.

In this paper, we have proposed a provably secure cross-domain AKA protocol tailored for the Internet of Vehicles (IoV). This protocol empowers the RSU to evaluate the communication status between itself and the vehicle, thereby enabling rapid cross-domain authentication for the vehicle. Additionally, we conducted a formal security analysis of the proposed protocol using the ROR model and Scyther. Finally, we performed a comparative analysis of the proposed protocol against existing protocols in terms of security and performance, with results demonstrating that our protocol excels in both security and performance.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Startup Foundation for Introducing Talent of Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Grant no. ZR202111230202).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Tsu-Yang Wu and Haozhi Wu; methodology, Tsu-Yang Wu and Haozhi Wu; validation, Maoxin Tang; formal analysis, Haozhi Wu and Maoxin Tang; investigation, Saru Kumari and Chien-Ming Chen; data curation, Saru Kumari and Chien-Ming Chen; writing—original draft preparation, Tsu-Yang Wu, Haozhi Wu, Maoxin Tang, Saru Kumari and Chien-Ming Chen; writing—review and editing, Tsu-Yang Wu, Maoxin Tang, Saru Kumari and Chien-Ming Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data are contained within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dey KC, Rayamajhi A, Chowdhury M, Bhavsar P, Martin J. Vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communication in a heterogeneous wireless network-Performance evaluation. Transport Res Part C: Emerg Technol. 2016;68(6):168–84. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2016.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yu S, Lee J, Park K, Das AK, Park Y. IoV-SMAP: secure and efficient message authentication protocol for IoV in smart city environment. IEEE Access. 2020;8:167875–86. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3022778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mejri MN, Ben-Othman J, Hamdi M. Survey on VANET security challenges and possible cryptographic solutions. Vehic Communicat. 2014;1(2):53–66. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2014.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li X, Liu T, Obaidat MS, Wu F, Vijayakumar P, Kumar N. A lightweight privacy-preserving authentication protocol for VANETs. IEEE Systems J. 2020;14(3):3547–57. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2020.2991168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gupta D, Rathi R. RDVFF-reliable data dissemination in vehicular ad hoc networks based on validation of far to farthest zone. J Internet Technol. 2024;25(1):87–104. [Google Scholar]

6. Sutrala AK, Bagga P, Das AK, Kumar N, Rodrigues JJ, Lorenz P. On the design of conditional privacy preserving batch verification-based authentication scheme for internet of vehicles deployment. IEEE Transacti Vehic Technol. 2020;69(5):5535–48. doi:10.1109/tvt.2020.2981934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lv S, Liu Y. PLVA: privacy-preserving and lightweight V2I authentication protocol. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2021;23(7):6633–9. doi:10.1109/tits.2021.3059638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang H, Zhang F, Shen Z, Liu P, Liu K. Blockchain-based IVPPA scheme for pseudonym privacy protection in internet of vehicles. J Network Intell. 2024;9(2):1260–77. [Google Scholar]

9. Liu Y, Wang Y, Chang G. Efficient privacy-preserving dual authentication and key agreement scheme for secure V2V communications in an IoV paradigm. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2017;18(10):2740–9. doi:10.1109/tits.2017.2657649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lee J, Kim G, Das AK, Park Y. Secure and efficient honey list-based authentication protocol for vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Transact Netw Sci Eng. 2021;8(3):2412–25. doi:10.1109/tnse.2021.3093435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Eftekhari SA, Nikooghadam M, Rafighi M. Security-enhanced three-party pairwise secret key agreement protocol for fog-based vehicular ad-hoc communications. Veh Commun. 2021;28(1):100306. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2020.100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xu C, Huang X, Ma M, Bao H. A privacy-preserving and cross-domain group authentication scheme for vehicular in LTE-A networks. J Communicat. 2017;12(11):604–10. doi:10.12720/jcm.12.11.604-610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yang Y, Wei L, Wu J, Long C, Li B. A blockchain-based multidomain authentication scheme for conditional privacy preserving in vehicular ad-hoc network. IEEE Int Things J. 2021;9(11):8078–90. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yu F, Ma M, Li X. A blockchain-assisted seamless handover authentication for V2I communication in 5G wireless networks. In: ICC 2021-IEEE International Conference on Communications. Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

15. Jiang Q, Zhang X, Zhang N, Tian Y, Ma X, Ma J. Three-factor authentication protocol using physical unclonable function for IoV. Comput Communicat. 2021;173(5):45–55. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2021.03.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Babu PR, Reddy AG, Palaniswamy B, Das AK. EV-PUF: lightweight security protocol for dynamic charging system of electric vehicles using physical unclonable functions. IEEE Transact Netw Sci Eng. 2022;9(5):3791–807. doi:10.1109/tnse.2022.3186949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wu TY, Wu H, Kumari S, Chen CM. An enhanced three-factor based authentication and key agreement protocol using PUF in IoMT. Peer Peer Netw Appl. 2025;18(2):83. doi:10.1007/s12083-024-01839-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yan X, Ma M, Su R. A certificateless efficient and secure group handover authentication protocol in 5G enabled vehicular networks. In: ICC 2022-IEEE International Conference on Communications. Seoul, Republic of Korea: IEEE; 2022. p. 1678–84. doi:10.1109/ICC42927.2021.9500334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen CM, Li Z, Kumari S, Srivastava G, Lakshmanna K, Gadekallu TR. A provably secure key transfer protocol for the fog-enabled Social Internet of Vehicles based on a confidential computing environment. Veh Commun. 2023;39(1):100567. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2022.100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Costan V, Devadas S. Intel SGX Explained, Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2016/086. 2016. [Google Scholar]

21. Liu X, Guo Z, Ma J, Song Y. A secure authentication scheme for wireless sensor networks based on DAC and Intel SGX. IEEE Int Things J. 2021;9(5):3533–47. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3097996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Will NC, Maziero CA. Intel software guard extensions applications: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(14s):322. doi:10.1145/3593021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dolev D, Yao A. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Transact Inform Theory. 1983;29(2):198–208. doi:10.1109/tit.1983.1056650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Canetti R, Krawczyk H. Analysis of key-exchange protocols and their use for building secure channels. In: International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2001. p. 453–74. doi:10.1007/3-540-44987-6_28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gao Y, Zhou T, Zheng W, Yang H, Zhang T. High-availability authentication and key agreement for internet of things-based devices in Industry 5.0. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2024;20(12):13571–9. doi:10.1109/tii.2024.3414443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alrashdi I, Tanveer M, Aldossari SA, Alshammeri M, Armghan A. BSCP-SG: blockchain-enabled secure communication protocols for IoT-driven smart grid systems. Int Things. 2025;32(2):101626. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2025.101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools