Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Topological Characterization and Predictive Modeling of Graph Energy in Ionic Covalent Organic Frameworks

1 Department of Mathematics, Loyola College, Chennai, 600034, India

2 Department of Mathematics, Loyola College, University of Madras, Chennai, 600034, India

* Corresponding Author: Micheal Arockiaraj. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computational Modeling and Simulation of Energy and Environmental Materials)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 637-655. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065674

Received 19 March 2025; Accepted 29 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are crystalline materials composed of covalently bonded organic ligands with chemically permeable structures. Their crystallization is achieved by balancing thermal reversibility with the dynamic nature of the frameworks. Ionic covalent organic frameworks (ICOFs) are a subclass that incorporates ions in positive, negative, or zwitterionic forms into the frameworks. In particular, spiroborate-derived linkages enhance both the structural diversity and functionality of ICOFs. Unlike electroneutral COFs, ICOFs can be tailored by adjusting the types and arrangements of ions, influencing their formation mechanisms and physical properties. This study focuses on analyzing the graph-based structural characteristics of ICOFs with spiroborate linkages. We compute graph based entropy using hybrid topological descriptors that capture both local and global structural patterns. Furthermore, statistical regression models are developed to predict graph energies of larger-dimensional ICOF structures based on these descriptors. To ensure the robustness and accuracy of our results, we validated our findings using a pseudocode algorithm specifically designed for computing degree-based topological indices. This computational validation confirms the consistency of the derived descriptors and supports their applicability in quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) modeling. Overall, this approach provides valuable insights for future applications in material design and property prediction within the framework of ICOFs.Keywords

Covalent organic frameworks are crystalline materials with a porous structure, formed by organic molecular building blocks made up of light elements, which are interconnected through covalent bonds [1,2]. COFs can form crystalline structures with permanent porosity, enabling organic reactions to occur without altering their properties [3]. The structural adaptability of COFs enables their use in a wide range of applications, including gas separation, drug discovery, heterogeneous catalysis, and energy conversion [4,5]. A defining feature of COFs is their uniquely predictable skeleton structures, which distinguish them from other porous polymeric materials [6]. The design of COFs with structural arrangements and tailored pore sizes relies on the strategic choice of linkers and molecular building units [7]. The polymerization process combines covalent bonds with noncovalent interactions, resulting in well-organized, extended crystalline frameworks. The crystallization of COFs successfully resolves the persistent challenge of crystallizing covalent solids. This is achieved by carefully balancing thermodynamic and kinetic factors during the reversible formation of covalent bonds, which is vital for producing extended crystalline structures [8]. Concurrently, advances in ion-regulated design, particularly the incorporation of multivalent ions [9,10], zwitterionic groups [11], and spatial ion-binding architectures [12,13], have significantly enhanced the performance of ICOFs in terms of selective ion adsorption, ion-exchange capacity, and long-range ionic conductivity, especially under conditions of high ionic competition and dynamic operating environments [14].

The structure of a covalent organic framework is influenced by the size, arrangement, and connectivity of the linkers. COFs with boronate, spiroborate, imine, hydrazone, triazine, and benzyl nitrile linkages have been synthesized through polycondensation reactions between organic precursors [15]. Among these linkers, the spiroborates, derived from boronic acid, are ionic compounds known for their exceptional hydrolytic resistance and durability in aqueous, methanolic, and alkaline conditions [16]. Their ionic properties make spiroborate-linked COFs promising candidates for ion-conductive materials. These linkages are easily formed by condensing polyols with alkali tetraborate or boric acid, or through transesterification between borates and polyols under thermodynamically controlled conditions. They have also found widespread use in the synthesis of macrocycles, facilitating a wide range of applications, including electrolytes, sensors, catalysts, and hosts for neutral molecules or ions [17–19]. Recent developments in ionic covalent organic frameworks have highlighted a wide range of synthetic strategies, particularly leveraging dynamic covalent chemistry to achieve tunable architectures and enhanced energy functionalities [20–23].

This study investigates the topological characterization of ionic covalent organic frameworks (ICOFs) via spiroborate linkages, incorporating

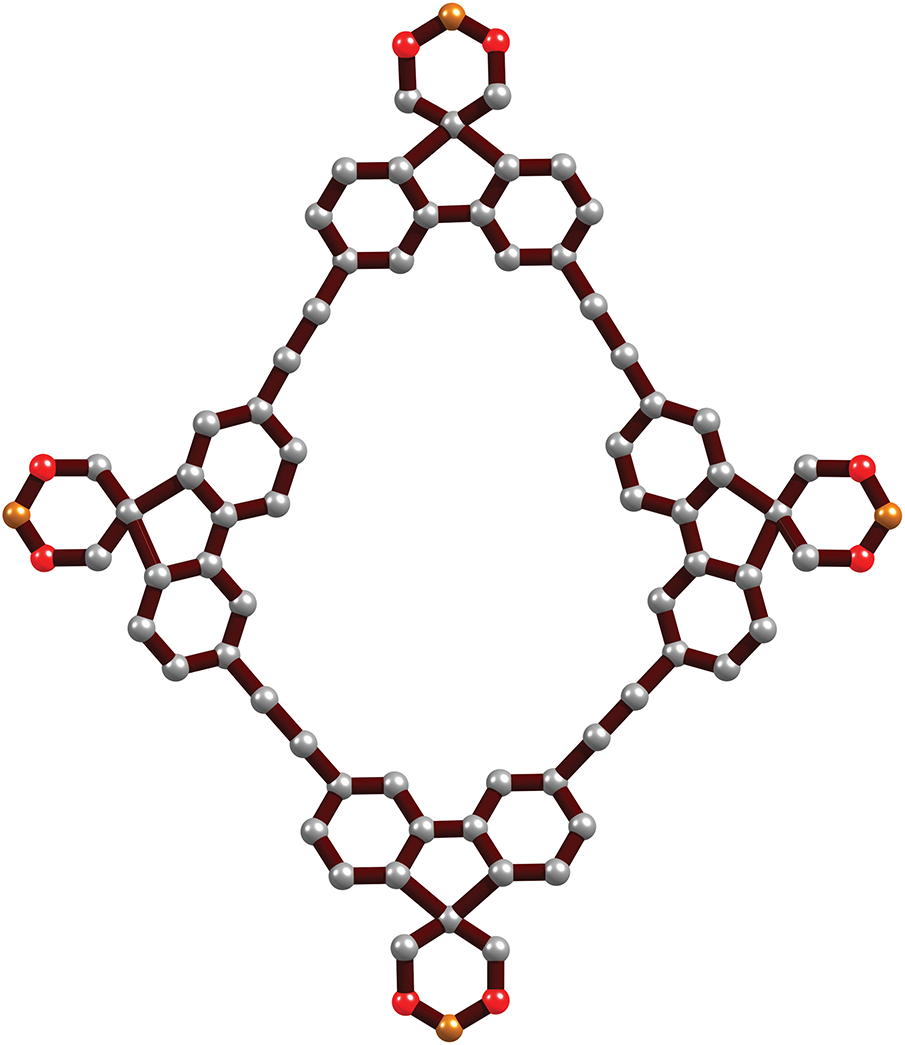

Figure 1: The building block of ICOF is composed of carbon atoms depicted in grey, boron atoms in yellow, and oxygen atoms in red

Topological descriptors serve as a means to characterize the molecular graphs of ICOF, with degree-based descriptors reflecting atom valency through vertex degrees at bond ends [34,35], and potentially being used to quantify ICOFs through QSPR and QSAR analyses [36–39]. Degree-based topological indices (TIs) are key graph invariants derived from various graph properties [40] which are fundamentally grounded in the vertex degree, representing the number of edges connected to a vertex. To refine this traditional degree-based TIs, neighborhood degree-based TIs, which sum the degrees of a vertex’s adjacent vertices, are being developed as a more effective measure [41–44]. These descriptors are widely used in areas such as molecular modeling and applied materials research, delivering valuable insights across a broad range of disciplines [45–49]. In the context of ICOFs, these descriptors provide a rigorous framework for understanding structure–property relationships that influence critical functionalities such as ion transport, adsorption, and energy storage [50–54]. In information theory, Shannon’s entropy plays a crucial role in quantifying system uncertainty. Graph entropy measures, particularly those derived from degree descriptors, are widely used in graph theory to assess the complexity and diversity of molecular graphs [55–57]. Its versatility across fields such as biology and chemistry makes it an essential tool for analyzing complex systems [58–60]. In parallel, topological descriptors and entropy-based analyses have gained traction in quantifying structure–property relationships in porous and crystalline frameworks [61–64]. This evolving literature forms the foundation for our graph-theoretic approach, which complements recent machine-learning-based models and contributes to a deeper understanding of structure-driven energy properties in ICOFs.

The Hückel molecular orbital (HMO) theory is frequently used to calculate the total

The ionic covalent organic framework (ICOF), characterized by spiroborate linkages, can be represented as a molecular graph, where the vertex set

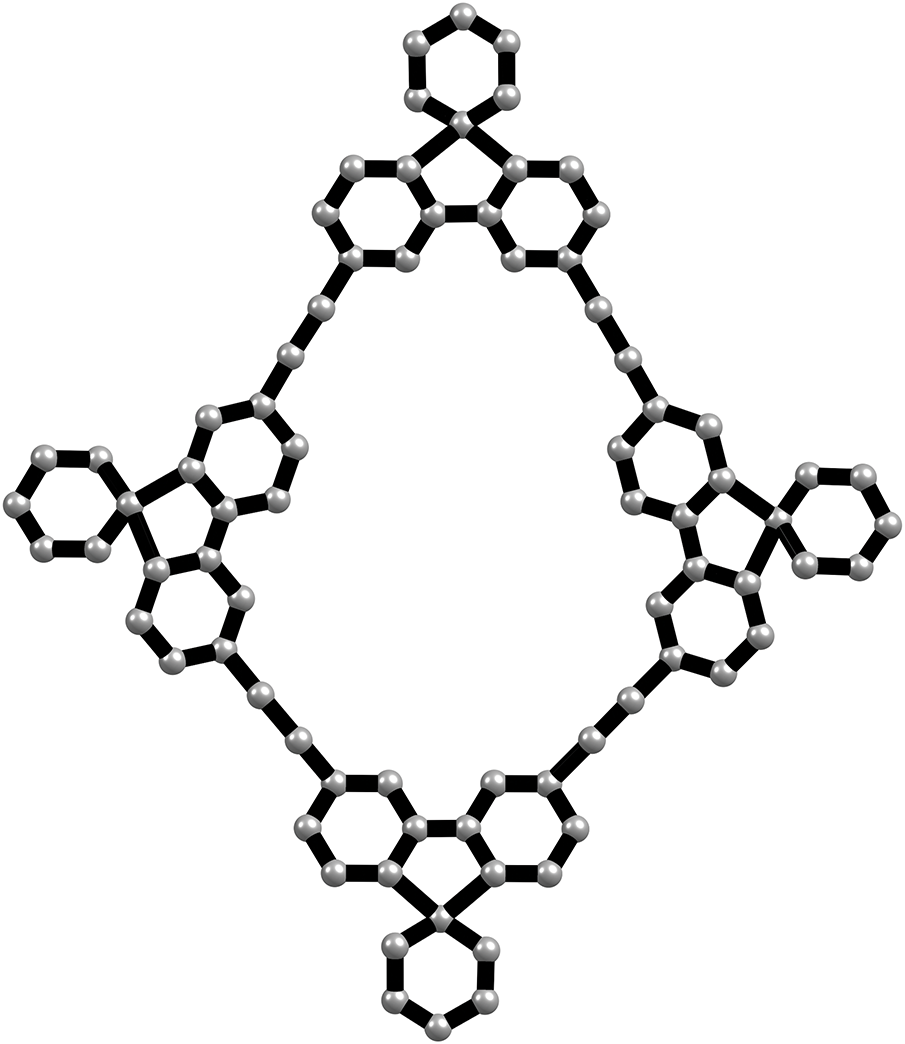

Figure 2: The molecular graph of ICOF

In this framework, the degree of a vertex

The index function

The hybrid descriptors, along with the index function

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

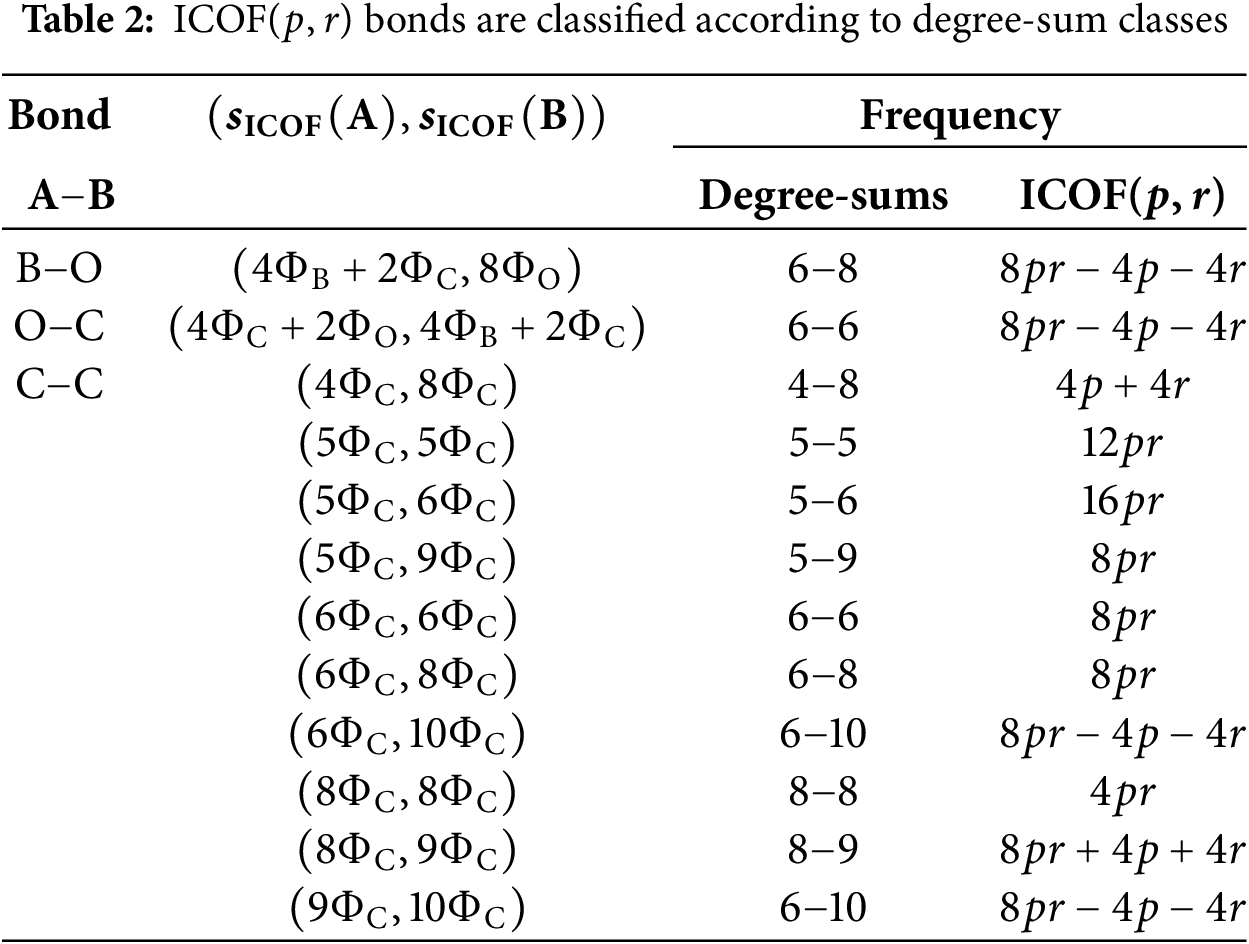

As we see from the definitions of topological descriptors, the classification of edge classes does not consider the specific types of atoms at their terminal points. However, it is essential to distinguish between the three types of atoms that form the basis of ionic covalent organic frameworks. To enhance the partitions based on

Shannon’s entropy method is used to define a structural information function for the bonds in ICOF. A high entropy value signifies greater complexity or disorder, while a low entropy value indicates more order and regularity. The following form is used to define the entropy of the ICOF structure using

The modified entropy approach, which replaces the multiplicative form with a scalar multiplicative form, is outlined below [57,81].

The adjacency matrix of an ICOF determines its spectrum through its eigenvalues, which are denoted as

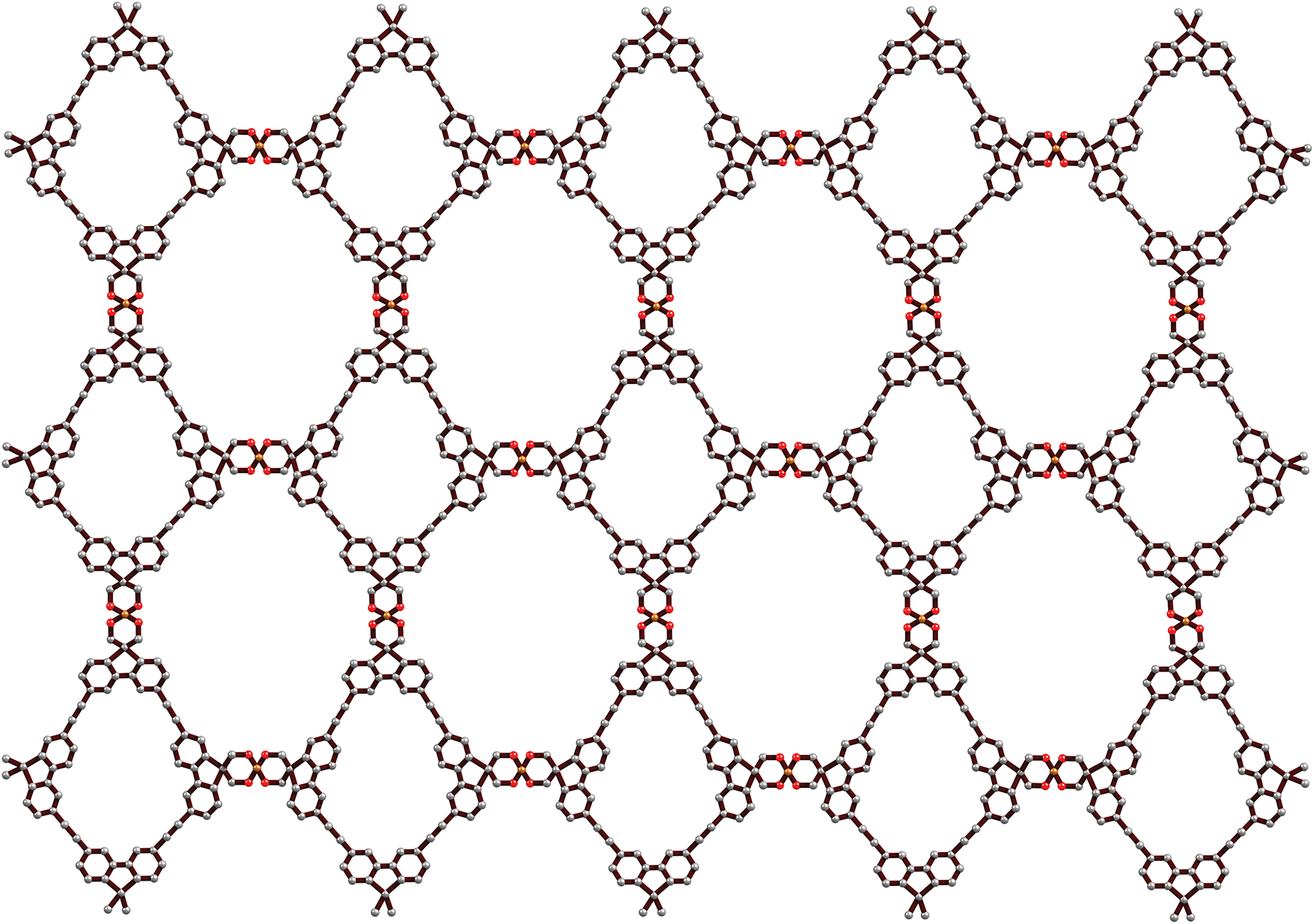

The structural configuration of ionic covalent organic frameworks, with an emphasis on comparing their topological features using entropy information is explored in this section. The COFs featuring spiroborate linkages are depicted in a parallelogram peripheral shape, achieved by arranging the ionic COF units in a

Figure 3: ICOF in parallelogram of dimensions

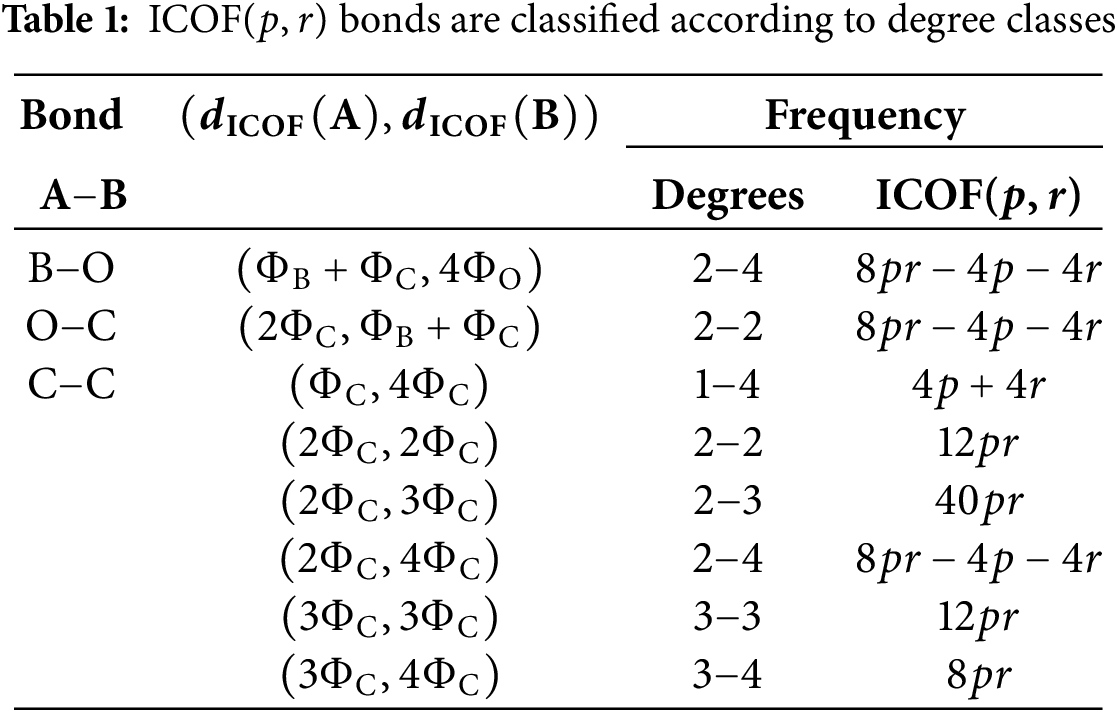

The bond classes of ICOF are distributed over the set

The degree and degree-sum-based descriptors for ICOF(

By setting the atom and bond weights to unity, the above two equations can be simplified in the following form.

We now illustrate the computation of the index

We now derive the numerical expressions for the topological descriptors of ICOF(

Result 1. The topological descriptors for ICOF are algebraically expressed for

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

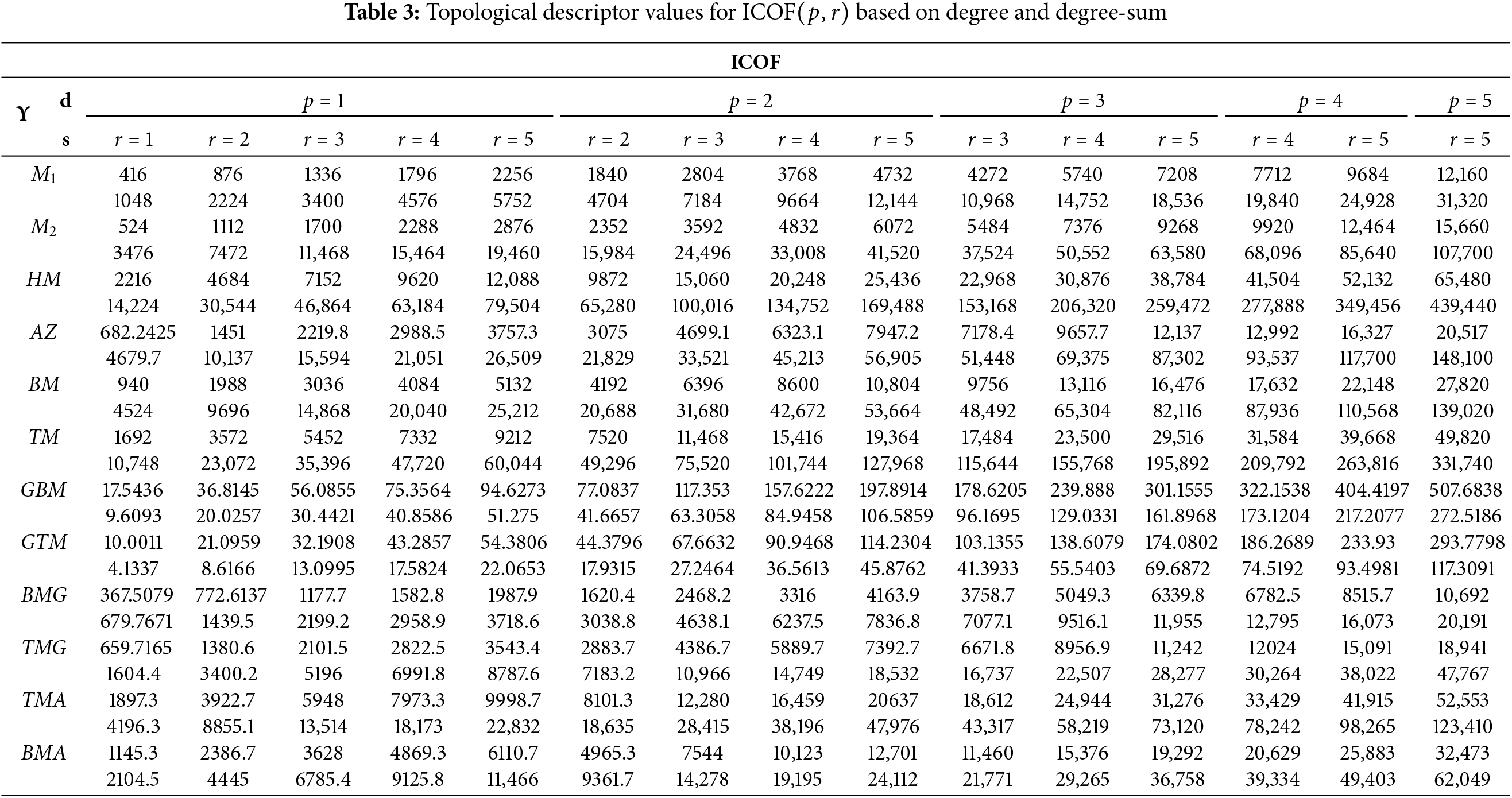

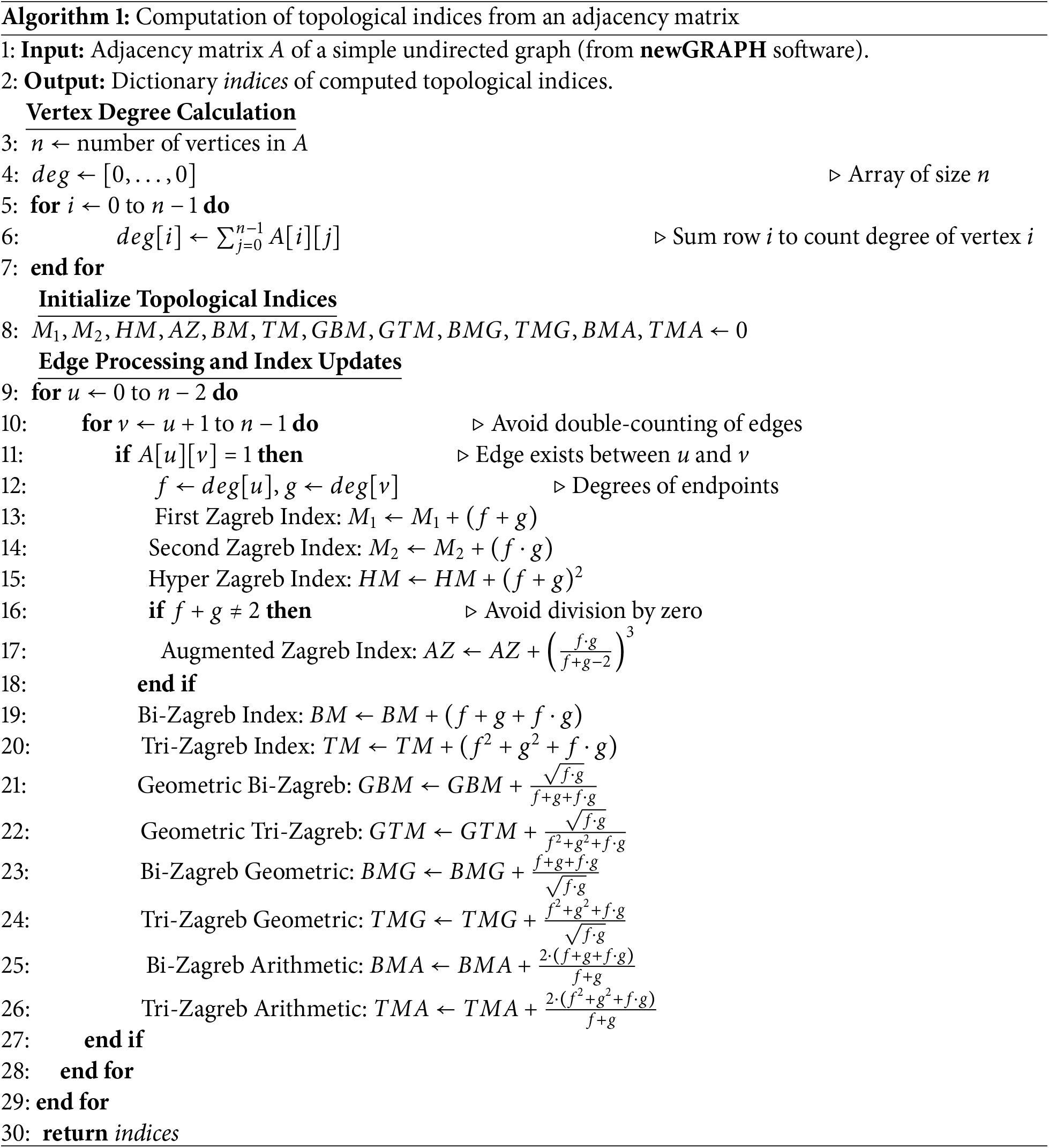

The numerical values for the dimensions of ICOFs are computed using mathematical expressions derived from prior results, as presented in Table 3, and are further validated using the pseudocode algorithm for computing degree-based topological indices, as presented in Algorithm 1. These values are essential for determining the frameworks entropy levels such that the multiplicative self-powered descriptors are available. The algebraic expressions for these descriptors are given below.

1.

2.

where we used

The formulas based on topological and self-powered descriptors are used to derive entropy expressions, resulting in more complex formulations. An illustrative computation of the modified Shannon entropy for ICOF(3,3), using the

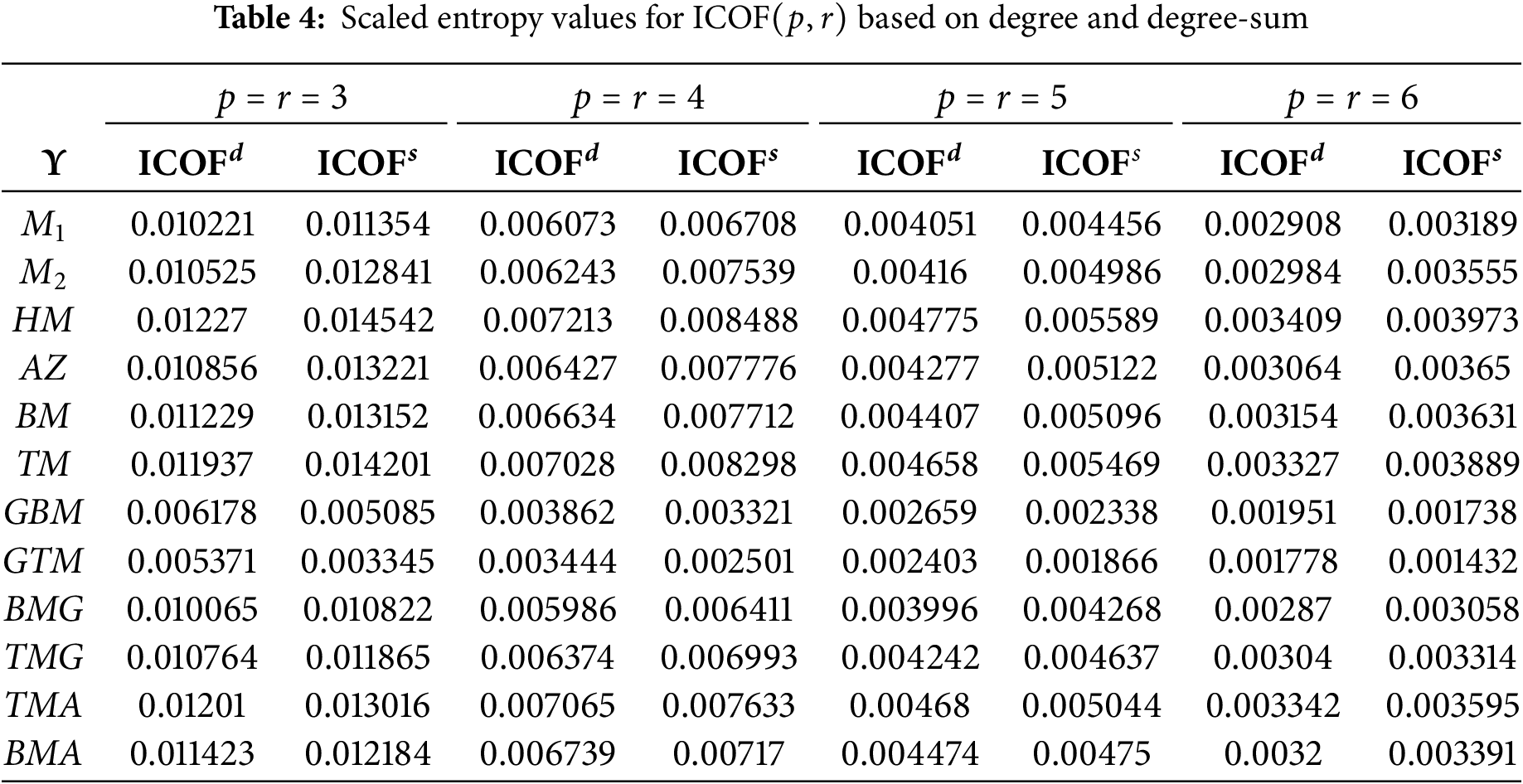

We have now correlated the topological index and entropy values for the case where the dimensions

Extending this approach, QSPR models could be formulated when experimental physicochemical data for ICOF become available.

As a result, entropy values of topological descriptors based on degree and degree-sum are calculated by equating their dimensions, setting

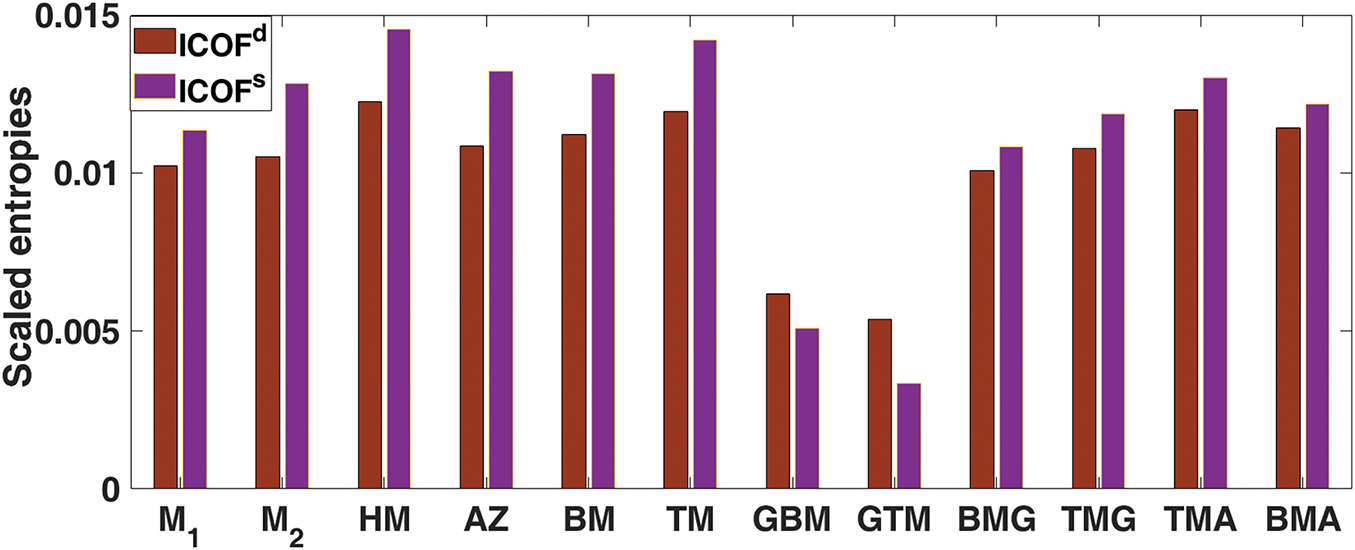

Figure 4: Bar diagram of scaled entropy for ICOF(

In this section, we develop linear regression models for producing the graph energies of ICOFs using the topological indices that were determined in the preceding section. The relationship between a graph’s structural characteristics and the overall

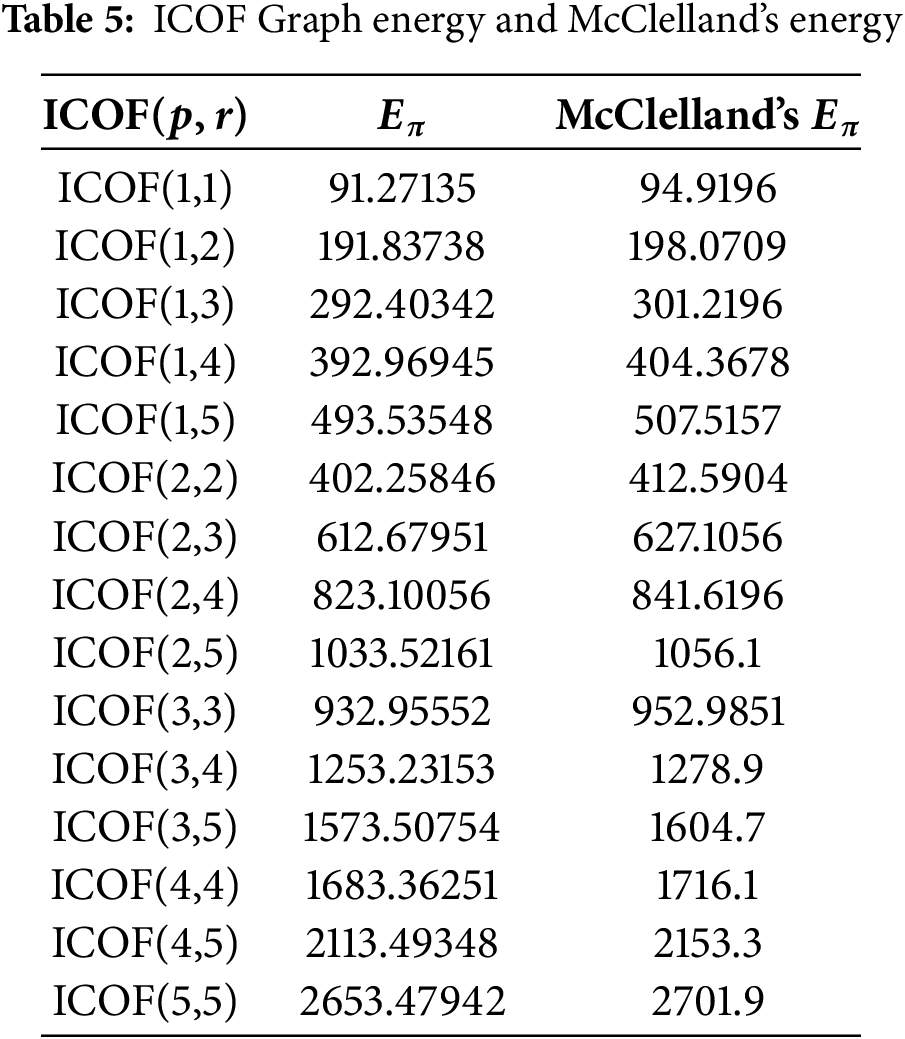

The eigen-spectrum and graph energy for specific dimensions of ICOFs were calculated using the machine-generated package [89] in conjunction with McClelland’s graph energy as shown in Table 5. A linear regression model,

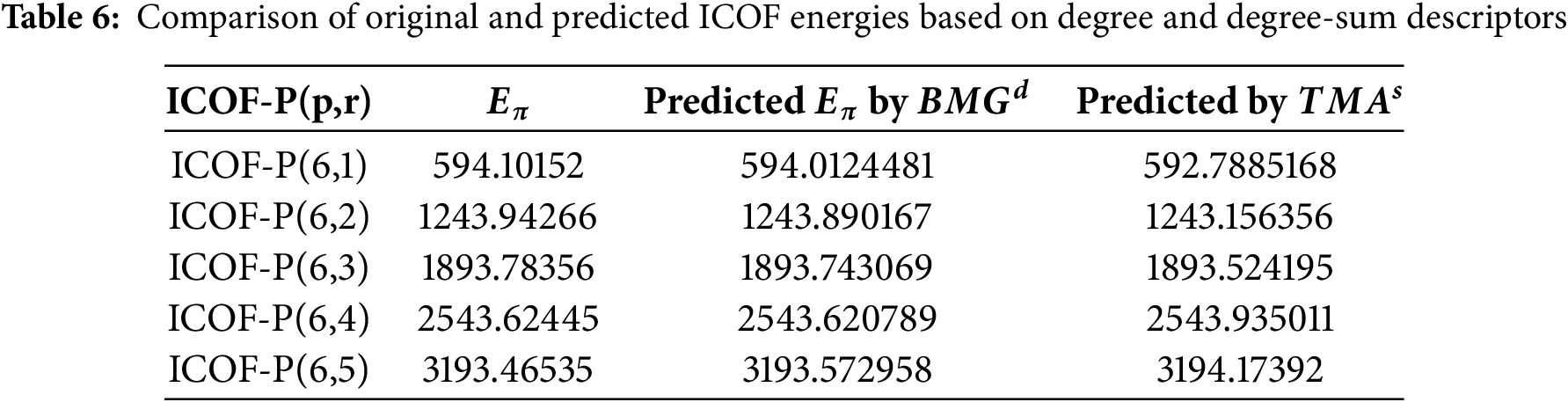

The bi-Zagreb-geometric index is the most effective for modeling linear regression models of ICOFs using degree descriptors, whereas the tri-Zagreb-arithmetic index yields the highest accuracy for degree-sum descriptors, as shown below.

The geometric-tri-Zagreb and bi-Zagreb-geometric indices exhibit higher entropy values due to their strong topological structural relevance, allowing them to effectively capture the intricate connectivity and branching patterns of ICOF frameworks. This enhances their capacity to reflect the spectral and energetic characteristics of these materials.

Given that the computation of graph energy through spectral methods involves eigenvalue analysis, which becomes increasingly complex and resource-intensive for large molecular structures, we developed linear regression models based on topological descriptors as a practical alternative. These models enable efficient estimation of graph energies without the need for full spectral decomposition. As shown in Table 6, the predicted values closely approximate the actual spectral energies, with minimal error (e.g., an error of only 0.089 units for ICOF-P(6,1)). Although minor discrepancies are observed, the models offer a computationally efficient and scalable approach for estimating graph energies in complex systems. This predictive framework serves as a useful tool for large-scale applications, where exact spectral calculations may be impractical.

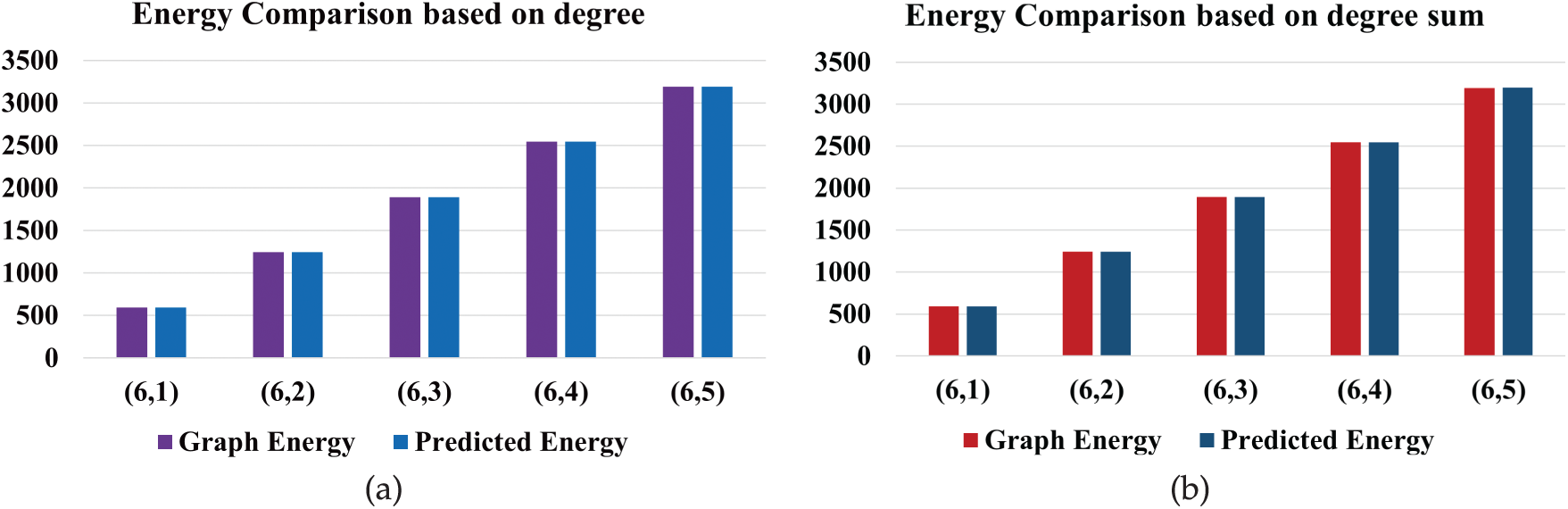

The graph energy of ICOFs is predicted using degree and degree-sum descriptors, based on the regression equations outlined earlier. As shown in Table 6, these predicted values are compared with the original

Figure 5: Graph energy prediction using (a) degree and (b) degree-sum

We have discussed the topological descriptors and entropies of ICOFs with parallelogram configurations. Our analysis, using scaled entropy measures, demonstrated that degree-based entropy reveals a higher level of informational disorder than degree-sum entropy, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the structural arrangement. To further enhance computational efficiency, we developed a set of optimized linear regression models specifically designed to predict graph energy across ICOF frameworks of varying dimensions. By refining these models, we were able to significantly reduce the computational complexity while maintaining high predictive accuracy. The results not only expand our understanding of the structural diversity within ICOF frameworks but also provide valuable insights into the relationship between framework dimensions and graph energy. These findings open new avenues for future research by providing a robust framework for exploring ICOF properties and guiding the design of advanced materials in this domain.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the study as follows: Conceptualization, Micheal Arockiaraj and Aravindan Maaran; methodology, Aravindan Maaran and C. I. Arokiya Doss; validation, Aravindan Maaran and C. I. Arokiya Doss; investigation, Micheal Arockiaraj and Aravindan Maaran; writing—original draft preparation, Aravindan Maaran; writing—review and editing, Micheal Arockiaraj and C. I. Arokiya Doss. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated during this work are included in this paper.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Waller PJ, Gándara F, Yaghi OM. Chemistry of covalent organic frameworks. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48(12):3053–63. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Geng K, He T, Liu R, Dalapati S, Tan KT, Li Z, et al. Covalent organic frameworks: design, synthesis, and functions. Chem Rev. 2020;120(16):8814–933. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lyle SJ, Waller PJ, Yaghi OM. Covalent organic frameworks: organic chemistry extended into two and three dimensions. Trends Chem. 2019;1(2):172–84. doi:10.1016/j.trechm.2019.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wu MX, Yang Y-W. Applications of covalent organic frameworks (COFsfrom gas storage and separation to drug delivery. Chin Chem Lett. 2017;28(6):1135–43. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.03.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang D-G, Qiu T, Guo W, Liang Z, Tabassum H, Xia D, et al. Covalent organic framework-based materials for energy applications. Energy Environ Sci. 2021;14(2):688–728. doi:10.1039/d0ee02309d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tran QN, Lee HJ, Tran N. Covalent organic frameworks: from structures to applications. Polymers. 2023;15(5):1279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Abuzeid HR, Mahdy AFME, Kuo S-W. Covalent organic frameworks: design principles, synthetic strategies, and diverse applications. Giant. 2021;6(2):100054. doi:10.1016/j.giant.2021.100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Côté AP, El-Kaderi HM, Furukawa H, Hunt JR, Yaghi OM. Reticular synthesis of microporous and mesoporous 2D covalent organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(43):12914–5. doi:10.1021/ja0751781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Hu Y, Dunlap N, Wan S, Lu S, Huang S, Sellinger I, et al. Crystalline lithium imidazolate covalent organic frameworks with high Li-ion conductivity. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(18):7518–25. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b02448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wang Y, Qi Y, Bi G, Yin W, Zhang W. Temperature-adaptive aqueous zinc-iodine batteries enabled by ionic covalent organic framework modified separator. J Phys Chem Lett. 2025;16(22):5515–22. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.5c01097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kim Y, Li C, Huang J, Yuan Y, Tian Y, Zhang W. Ionic covalent organic framework solid-state electrolytes. Adv Mater. 2024;36(40):2407761. doi:10.1002/adma.202407761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Meng QW, Li J, Xing Z, Xian W, Lai Z, Dai Z, et al. Regulation of ion binding sites in covalent organic framework membranes for enhanced selectivity under high ionic competition. ACS Nano. 2025;19(12):12080–9. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c18135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao X, Chen Y, Wang Z, Zhang Z. Design and application of covalent organic frameworks for ionic conduction. Polym Chem. 2021;12(34):4874–94. doi:10.1039/d1py00776a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang W, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Zhang R, Wang N, Dou Y, et al. Achieving multi-dimensional Li+ transport nanochannels via spatial-partitioning in crystalline ionic covalent organic frameworks for highly stable lithium metal anode. Chem Eng J. 2023;472(18):144888. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.144888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liang X, Tian Y, Yuan Y, Kim Y. Ionic covalent organic frameworks for energy devices. Adv Mater. 2021;33(52):2105647. doi:10.1002/adma.202105647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Brown HC, Rangaishenvi MV. Organoboranes: LI. Convenient procedures for the recovery of pinanediol in asymmetric synthesis via one-carbon homologation of boronic esters. J Organomet Chem. 1988;358(1–3):15–30. [Google Scholar]

17. Danjo H, Hirata K, Yoshigai S, Azumaya I, Yamaguchi K. Back to back twin bowls of D3-symmetric tris(spiroborate)s for supramolecular chain structures. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(5):1638–39. doi:10.1021/ja8071435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Loewer Y, Weiss C, Biju AT, Fröhlich R, Glorius F. Synthesis and application of a chiral diborate. J Org Chem. 2011;76(7):2324–27. doi:10.1021/jo102559s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Moriya M, Kato D, Sakamoto W, Yogo T. Plastic crystalline lithium salt with solid-state ionic conductivity and high lithium transport number. Chem Commun. 2011;47(22):6311–3. doi:10.1039/c1cc00070e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ben H, Du W, Zhao J, Wang Y, Wu Y, Lin F, et al. Ionic covalent organic frameworks: from synthetic strategies to advanced electro-, photo-, and thermo- energy functionalities. Coord Chem Rev. 2024;517:216003. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang X, Li W, Guan Y, Zhou B, Zhang J. Theoretical investigation of the topology of spiroborate-linked ionic covalent organic frameworks (ICOFs). Chem Eur J. 2019;25(26):6569–74. doi:10.1002/chem.201806400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Jin Y, Yu C, Denman RY, Zhang W. Recent advances in dynamic covalent chemistry. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42(13):6634–54. doi:10.1039/c3cs60044k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lei Z, Chen H, Huang S, Wayment LJ, Xu Q, Zhang W. New advances in covalent network polymers via dynamic covalent chemistry. Chem Rev. 2024;124(12):7829–906. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Du Y, Yang H, Whiteley JM, Wan S, Jin Y, Lee S-H, et al. Ionic covalent organic frameworks with spiroborate linkage. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2016;55(5):1737–41. doi:10.1002/anie.201509014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Li J, Zhang F-Q, Li F, Wu Z, Ma C, Xu Q, et al. A pre-synthetic strategy to construct single ion conductive covalent organic frameworks. Chem Commun. 2020;56(18):2747–50. doi:10.1039/d0cc00454e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Jeong K, Park S, Jung GY, Kim SH, Lee Y-H, Kwak SK, et al. Solvent-free, single lithium-ion conducting covalent organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(14):5880–5. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b00543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yu F, Ciou J-H, Chen S, Poh WC, Chen J, Chen J, et al. Ionic covalent organic framework based electrolyte for fast-response ultra-low voltage electrochemical actuators. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):390. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28023-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Li Z, Li H, Guan X, Tang J, Yusran Y, Li Z, et al. Three-dimensional ionic covalent organic frameworks for rapid, reversible and selective ion exchange. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(49):17771–4. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b11283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Liu M, Xu Q, Zeng G. Ionic covalent organic frameworks in adsorption and catalysis. Angew Chem. 2024;136(22):e202404886. [Google Scholar]

30. Xu Q, Tao S, Jiang Q, Jiang D. Designing covalent organic frameworks with a tailored ionic interface for ion transport across one-dimensional channels. Angew Chem. 2020;132(11):4587–93. doi:10.1002/ange.201915234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen H, Tu H, Hu C, Liu Y, Dong D, Sun Y, et al. Cationic covalent organic framework nanosheets for fast Li-ion conduction. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(3):896–9. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b12292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yu J, Luo L, Shang H, Sun B. Rational fabrication of ionic covalent organic frameworks for chemical analysis applications. Biosensors. 2023;13(6):636. doi:10.3390/bios13060636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Tan X, Gou Q, Yu Z, Pu Y, Huang J, Huang H, et al. Nanocomposite based on organic framework-loading transition-metal Co ion and cationic pillar[6]arene and its application for electrochemical sensing of L-ascorbic acid. Langmuir. 2020;36(48):14676–85. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c02398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ravi V, Desikan K. Curvilinear regression analysis of benzenoid hydrocarbons and computation of some reduced reverse degree based topological indices for hyaluronic acid-paclitaxel conjugates. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3239. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-28416-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hasani M, Ghods M. Topological indices and QSPR analysis of some chemical structures applied for the treatment of heart patients. Int J Quantum Chem. 2024;124(1):e27234. doi:10.1002/qua.27234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kiranaa B, Shanmukha MC, Usha A. A QSPR analysis and curvilinear regression models for various degree-based topological indices: quinolone antibiotics. Heliyon. 2024;10(12):e32397. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zaman S, Yaqoob HSA, Ullah A, Sheikh M. QSPR analysis of some novel drugs used in blood cancer treatment via degree based topological indices and regression models. Polycycl Aromat Comp. 2024;44(4):2458–74. doi:10.1080/10406638.2023.2217990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Abubakar MS, Aremu KO, Aphanea M, Amusa LB. A QSPR analysis of physical properties of antituberculosis drugs using neighbourhood degree-based topological indices and support vector regression. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e28260. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Pattabiraman K. Empowerments of blood cancer therapeutics via molecular descriptors. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2024;252(7):105180. doi:10.1016/j.chemolab.2024.105180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Hayat S, Mahadi H, Alanazi SJF, Wang S. Predictive potential of eigenvalues-based graphical indices for determining thermodynamic properties of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with applications to polyacenes. Comput Mater Sci. 2024;238(34):112944. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2024.112944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Mondal S, Das KC. Degree-based graph entropy in structure-property modeling. Entropy. 2023;25(7):1092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

42. Yang J, Konsalraj J, Raja AAS. Neighbourhood sum degree-based indices and entropy measures for certain family of graphene molecules. Molecules. 2023;28(1):168. doi:10.3390/molecules28010168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Gutman I. Degree-based topological indices. Croat Chem Acta. 2013;86(4):351–61. doi:10.5562/cca2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kumar V, Das S. On structure sensitivity and chemical applicability of some novel degree-based topological indices, MATCH Commun. Math Comput Chem. 2024;92:165–203. [Google Scholar]

45. Balasubramanian K. Relativistic quantum chemical and molecular dynamics techniques for medicinal chemistry of bioinorganic compounds. In: Saxena AK, editor. Biophysical and computational tools in drug discovery, topics in medicinal chemistry. Vol. 37. Cham: Springer; 2021. p. 133–93. doi:10.1007/7355_2020_109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Balasubramanian K. Computational and artificial intelligence techniques for drug discovery and administration. Compr Adv Pharmacol. 2022;2(1):553–616. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-820472-6.00015-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Meharban S, Ullah A, Zaman S, Hamraz A, Razaq A. Molecular structural modeling and physical characteristics of anti-breast cancer drugs via some novel topological descriptors and regression models. Curr Res Struct Biol. 2024;7(9):100134. doi:10.1016/j.crstbi.2024.100134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Zhang X, Siddiqui MK, Javed S, Sherin L, Kausar F, Muhammad MH. Physical analysis of heat for formation and entropy of ceria oxide using topological indices. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2022;25(3):441–50. doi:10.2174/1386207323999201001210832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang X, Saif MJ, Idrees N, Kanwal S, Parveen S, Saeed F. QSPR analysis of drugs for treatment of schizophrenia using topological indices. ACS Omega. 2023;8(44):41417–26. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c05000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Arockiaraj M, Greeni AB, Kalaam ARA. Linear versus cubic regression models for analyzing generalized reverse degree based topological indices of certain latest corona treatment drug molecules. Int J Quantum Chem. 2023;123(16):e27136. doi:10.1002/qua.27136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Liu JB, Wang C, Wang S, Wei B. Zagreb indices and multiplicative Zagreb indices of Eulerian graphs. Bull Malays Math Sci Soc. 2019;429(1):67–78. doi:10.1007/s40840-017-0463-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hayat S, Khan A, Ali K, Liu J-B. Structure-property modeling for thermodynamic properties of benzenoid hydrocarbons by temperature-based topological indices. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(3):102586. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2023.102586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Liu JB, Bao Y, Zheng WT, Hayat S. Network coherence analysis on a family of nested weighted n-polygon networks. Fractals. 2021;29(8):2150260. doi:10.1142/s0218348x21502601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang X, Arockiaraj M, Maaran A, Doss CIA. Topological information entropy and spectral energy analysis in aminal-linked covalent organic frameworks. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):19861. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-01210-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Sabirov DS, Shepelevich IS. Information entropy in chemistry: an overview. Entropy. 2021;23(10):1240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

56. Lal S, Bhat VK, Sharma S. Topological indices and graph entropies for carbon nanotube Y-junctions. J Math Chem. 2024;62(1):73–108. doi:10.1007/s10910-023-01520-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Arockiaraj M, Jency J, Mushtaq S, Shalini AJ, Balasubramanian K. Covalent organic frameworks: topological characterizations, spectral patterns and graph entropies. J Math Chem. 2023;61(8):1633–64. doi:10.1007/s10910-023-01477-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Afzal F, Razaq MA, Afzal D, Hameed S. Weighted entropy of penta chains graph. Eurasian Chem Commun. 2020;2(6):652–62. doi:10.33945/sami/ecc.2020.6.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Kazemi R. Entropy of wieghted graphs with the degree-based topological indices as weights. MATCH Commun Math Comput Chem. 2016;76:69–80. [Google Scholar]

60. Rashevsky N. Life information theory, and topology. Bull Math Biophys. 1955;17:229–35. [Google Scholar]

61. Peter P, Clement J, Arockiaraj M, Jacob K. Predictive modeling of molecular interaction energies using topological and spectral entropies of zeolite AWW. Front Chem. 2025;13:1543588. doi:10.3389/fchem.2025.1543588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Kalaam ARA, Greeni AB, Arockiaraj M. Modified reverse degree descriptors for combined topological and entropy characterizations of 2D metal organic frameworks: applications in graph energy prediction. Front Chem. 2024;12:1470231. doi:10.3389/fchem.2024.1470231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Jacob K, Clement J, Arockiaraj M, Peter P, Balasubramanian K. Network topology and entropy analysis of tetragonal farneseite zeolites. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):14896. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-90177-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Krishnapriya AS, Haranczyk M, Morozov D. Topological descriptors help predict guest adsorption in nanoporous materials. J Phys Chem C. 2020;124(17):9360–8. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c01167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Raza Z, Arockiaraj M, Maaran A, Shalini AJ. A comparative study of topological entropy characterization and graph energy prediction for marta variants of covalent organic frameworks. Front Chem. 2024;12:1511678. doi:10.3389/fchem.2024.1511678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Graovac A, Gutman I, Trianjistić N. A linear relationship between the total

67. Jacob K, Clement J. Topological entropy characterization of zeolite EDI and its application in predicting molecular interactions. Eur Phys J Plus. 2024;139(2):161. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-024-04939-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Samaniego E, Anitescu C, Goswami S, Nguyen-Thanh VM, Guo H, Hamdia K, et al. An energy approach to the solution of partial differential equations in computational mechanics via machine learning: concepts, implementation and applications. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2020;362(2):112790. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2019.112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Mortazavi B, Rahaman O, Rabczuk T, Pereira LFC. Exceptional piezoelectricity, high thermal conductivity and stiffness and promising photocatalysis in two-dimensional MoSi2N4 family confirmed by first-principles. Nano Energy. 2021;82:105716. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.105716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Yang H, Hanif MF, Siddiqui MK, Hussain M, Hussain N, Fufa SA. On topological analysis of two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks via M-polynomial. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):6931. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-57291-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Jacob K, Clement J. Zeolite ATN: topological characterization and predictive analysis on potential energies using entropy measures. J Mol Struct. 2024;1299(3):137101. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.137101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Junias JS, Clement J, Rahul MP, Arockiaraj M. Two-dimensional phthalocyanine frameworks: topological descriptors, predictive models for physical properties and comparative analysis of entropies with different computational methods. Comput Mater Sci. 2024;235(24):112844. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2024.112844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Shanmukha MC, Ismail R, Gowtham KJ, Usha A, Azeem M, Sabri EHAA. Chemical applicability and computation of K-Banhatti indices for benzenoid hydrocarbons and triazine-based covalent organic frameworks. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):17743. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45061-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Hakeem A, Ullah A, Zaman S. Computation of some important degree-based topological indices for γ-graphyne and zigzag graphyne nanoribbon. Mol Phys. 2023;121(14):e2211403. doi:10.1080/00268976.2023.2211403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Das S, Kumar V. Neighborhood degree sum-based molecular indices and their comparative analysis of some silicon carbide networks. Phys Scr. 2024;99(5):055941. doi:10.1088/1402-4896/ad3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Nagarajan S, Durga M. A computational approach on fenofibrate drug using degree-based topological indices and M-polynomials. Asian J Chem Sci. 2024;14(2):43–57. doi:10.9734/ajocs/2024/v14i2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Arockiaraj M, Fiona JC, Shalini AJ. Comparative study of entropies in silicate and oxide frameworks. Silicon. 2024;16(8):3205–16. doi:10.1007/s12633-024-02892-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Arockiaraj M, Raza Z, Maaran A, Abraham J, Balasubramanian K. Comparative analysis of scaled entropies and topological properties of triphenylene-based metal and covalent organic frameworks. Chem Pap. 2024;78(7):4095–118. doi:10.1007/s11696-023-03295-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Arockiaraj M, Paul D, Clement J, Tigga S, Jacob K, Balasubramanian K. Novel molecular hybrid geometric-harmonic-Zagreb degree based descriptors and their efficacy in QSPR studies of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. SAR QSAR Environ Res. 2023;34(7):569–89. doi:10.1080/1062936x.2023.2239149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Arockiaraj M, Jency J, Maaran A, Abraham J, Balasubramanian K. Refined degree bond partitions, topological indices, graph entropies and machine-generated boron NMR spectral patterns of borophene nanoribbons. J Mol Struct. 2024;1295(11):136524. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.136524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Manzoor S, Siddiqui MK, Ahmad S. On entropy measures of molecular graphs using topological indices. Arab J Chem. 2020;13(8):6285–98. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.05.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Gutman I. The energy of a graph: old and new results. In: Betten A, Kohnert A, Laue R, Wassermann A, editors. Algebraic combinatorics and applications. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2001. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-59448-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. McClelland BJ. Properties of the latent roots of a matrix: the estimation of

84. Gutman I, Koolen JH, Moulto V, Parac M, Soldatović T, Vidović D. Estimating and approximating the total

85. Taherpour A, Mohammadinasab E. Topological relationship between Wiener, Padmaker-Ivan, and Szeged indices and energy and electric moments in armchair polyhex nanotubes with the same circumference and varying lengths. Fullerenes Nanotubes Carbon Nanostruct. 2010;18(1):72–86. doi:10.1080/15363830903291580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Hayat S, Khan S, Khan A, Imran M. A computer-based method to determine predictive potential of distance-spectral descriptors for measuring the

87. Balasubramanian K. Topological indices, graph spectra, entropies, Laplacians, and matching polynomials of n-dimensional hypercubes. Symmetry. 2023;15(2):557. doi:10.3390/sym15020557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Greeni AB, Kalaam ARA, Arockiaraj M. Predicting graph energy and entropy analysis of pent-heptagonal nanomaterials: insights from regression models using generalized reverse degree-sum topological indices. Mater Today Commun. 2024;41(2):110229. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.110229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Stevanović L, Brankov V, Cvetković D, Simić S. newGRAPH, A fully integrated environment used for research process in graph theory [Online]. [cited 2025 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.mi.sanu.ac.rs/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools