Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Finite Element Analysis of Inclusion Stiffness and Interfacial Debonding on the Elastic Modulus and Strength of Rubberized Mortar

1 Mag. Cs. Ing. c/m Ingeniería Mecánica, Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad de Talca, Curicó, 3340000, Chile

2 Engineering Systems Doctoral Program, Faculty of Engineering, Universidad de Talca, Curicó, 3340000, Chile

3 Depto. de Tecnologías Industriales, Universidad de Talca, Curicó, 3340000, Chile

4 Institut Clément Ader (ICA), Université de Toulouse, CNRS/INSA/UT3/ISAE-SUPAERO/IMT Mines-Albi, Toulouse, 31077, France

* Corresponding Author: Pedro Pesante. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 581-595. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065746

Received 21 March 2025; Accepted 21 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Rubberized concrete is one of the most studied applications of discarded tires and offers a promising approach to developing materials with enhanced properties. The rubberized concrete mixture results in a reduced modulus of elasticity and a reduced compressive and tensile strength compared to traditional concrete. This study employs finite element simulations to investigate the elastic properties of rubberized mortar (RuM), considering the influence of inclusion stiffness and interfacial debonding. Different homogenization schemes, including Voigt, Reuss, and mean-field approaches, are implemented using DIGIMAT and ANSYS. Furthermore, the influence of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between mortar and rubber is analyzed by periodic homogenization. Subsequently, the influence of the ITZ is examined through a linear fracture analysis with the stress intensity factor as a key parameter, using the ANSYS SMART crack growth tool. Finally, a non-linear study in FEniCS is carried out to predict the strength of the composite material through a compression test. Comparisons with high density polyethylene (HDPE) and gravel inclusions show that increasing inclusion stiffness enhances compressive strength far more effectively than simply improving the mortar/rubber bond. Indeed, when the inclusions are much softer than the surrounding matrix, any benefit gained on the elastic modulus or strength from stronger interfacial adhesion becomes almost negligible. This study provide numerical evidence that tailoring the rubber’s intrinsic stiffness—not merely strengthening the rubber/mortar interface—is a decisive factor for improving the mechanical performance of RuM.Keywords

The enormous amount of end-of-life tires (ELT) is one of the world’s major environmental issues. To avoid burning or disposing of them in landfills or stockpiling, the manufacturing industries are proposing different solutions to reuse materials derived from ELT [1]. At the same time, legislation and policies to regulate tire waste are emerging in several countries [2]. The main by-products are rubber, steel wires and textile fibers, which can be recycled in asphalt and pavement [3]; construction materials such as concrete [4–6]; sports and children’s playgrounds; acoustic insulator products [7,8]; molded objects; or artificial turf. Rubberized concrete (RuC) has been one of the most studied applications of discarded tires [9]. It is a sustainable concrete that contains tire rubber aggregates as a partial replacement for its natural aggregate (i.e., stone and sand). The processed rubber from waste tires can be categorized into three groups: ground rubber (smaller than 1 mm), crumb rubber (1–10 mm) and chipped or shredded rubber (10–100 mm), which can be used as a partial replacement for cement, fine aggregates or coarse aggregates in conventional concrete, respectively [10–12].

The effect of the size of the rubber particles, the percentage of replacement, and several treatment methods on the mechanical properties of RuC has been experimentally investigated over the past decades [13]. The rubberized concrete mixture results in a reduced modulus of elasticity and a degraded compressive and tensile strength compared to traditional concrete. However, it possesses a number of desirable properties, such as lower density and higher ductility, toughness, impact resistance, and energy dissipation compared to conventional concrete.

The decrease in RuC strength with increasing rubber content and particle size in the mixture is almost always detected. This weak performance can be attributed to: (i) the high Young’s moduli ratio (concrete is around ten thousand more stiffs than rubber), resulting in crack initiation in a pattern similar to that of the air voids in normal concrete; (ii) weak interfacial bond between the rubber aggregates and the cement matrix. The latter is because when rubber inclusions, which are hydrophobic, are mixed in concrete form air pockets, increasing the pore volume and therefore weaker hydration products are developed around the aggregates. This zone is known as the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and its thickness is determined by the intensity of the surface effects produced by the aggregate. The thickness is larger for larger inclusions and is also a function of their shape [14]. Researchers have partially overcome some of these negative properties using various ways to improve the bond performance of rubber particles. Among the more studied methods are water washing, water soaking, cement paste precoating, or NaOH or solvent treatments [13]. However, pretreatment is expensive, time consuming and produces a considerable amount of sludges that would be detrimental to the environment [15–18]. In fact, from a technical, practical and economical point of view, when rubber is soaked in water for 24 h before incorporating it into the mortar mixture, it is possible to add up to 5% crumb rubber with respect to aggregate weight, and still exceed design strength [19]. Generally, concrete with low rubber content (less than 10%) has a good balance between strength and toughness, but also meets the structural requirements for the properties of the material [11].

RuC can be characterized as a multi-phase material with generally three different representative levels: macro, meso and micro scales [20]. Micro-scale research refers to the atomic and molecular levels

From the atomic scale to the macroscale, a wide range of models and computational techniques have been proposed to understand its behavior and provide guidelines for improving the mechanical properties, performances, and safety of structures. The mechanical properties of concrete are largely determined by cementitious materials, but the influence of soft inclusions has been evaluated much less frequently. Several mesoscopic models of concrete have been developed for studying the influence of material composition on its nonlinear mechanical behavior: finite element model describing the random geometry of aggregates [21,22]; truss [23] and lattice models [24–26]; framework model [27]; finite element models combining isotropic damage model [28], plasticity-damage model [29] or the eXtended Finite Element Method (X-FEM) [30]; and meshless methods as well [31]. Some attempts of numerical simulations concerning RuC include a finite element model considering a stiffness damage parameter [32], a numerical model based on X-FEM [33], or simulations using a discrete element method [34].

This work focuses on the mesoscale, specifically predicting the effect of the debonding of rubber inclusions on the elastic modulus and the compression strength of rubberized mortar (RuM). First, the elastic properties of the composite are estimated using different homogenization techniques, from the properties of rubber and mortar and including the influence of the ITZ. For this, finite element simulations are performed in DIGIMAT and ANSYS software (see Section 3). Then, an approach from the elastic fracture mechanics is carried out using the SMART (Separating Morphing and Adaptive Remeshing Technology) routine in ANSYS to appreciate the influence of ITZ on the stress intensity factor (Section 4). In addition, the role of the stiffness ratio between the inclusion and the matrix in the stress intensity factor is studied. In Section 5, the cohesive zone model is adopted in the FEniCS software [35] to simulate the entire fracture process in compression tests. Three inclusion scenarios (rubber, HDPE, and gravel) are considered to predict the compressive strength at varying the ITZ fracture energy. The numerical curves are compared to the experimental datasets reported in [19,36,37].

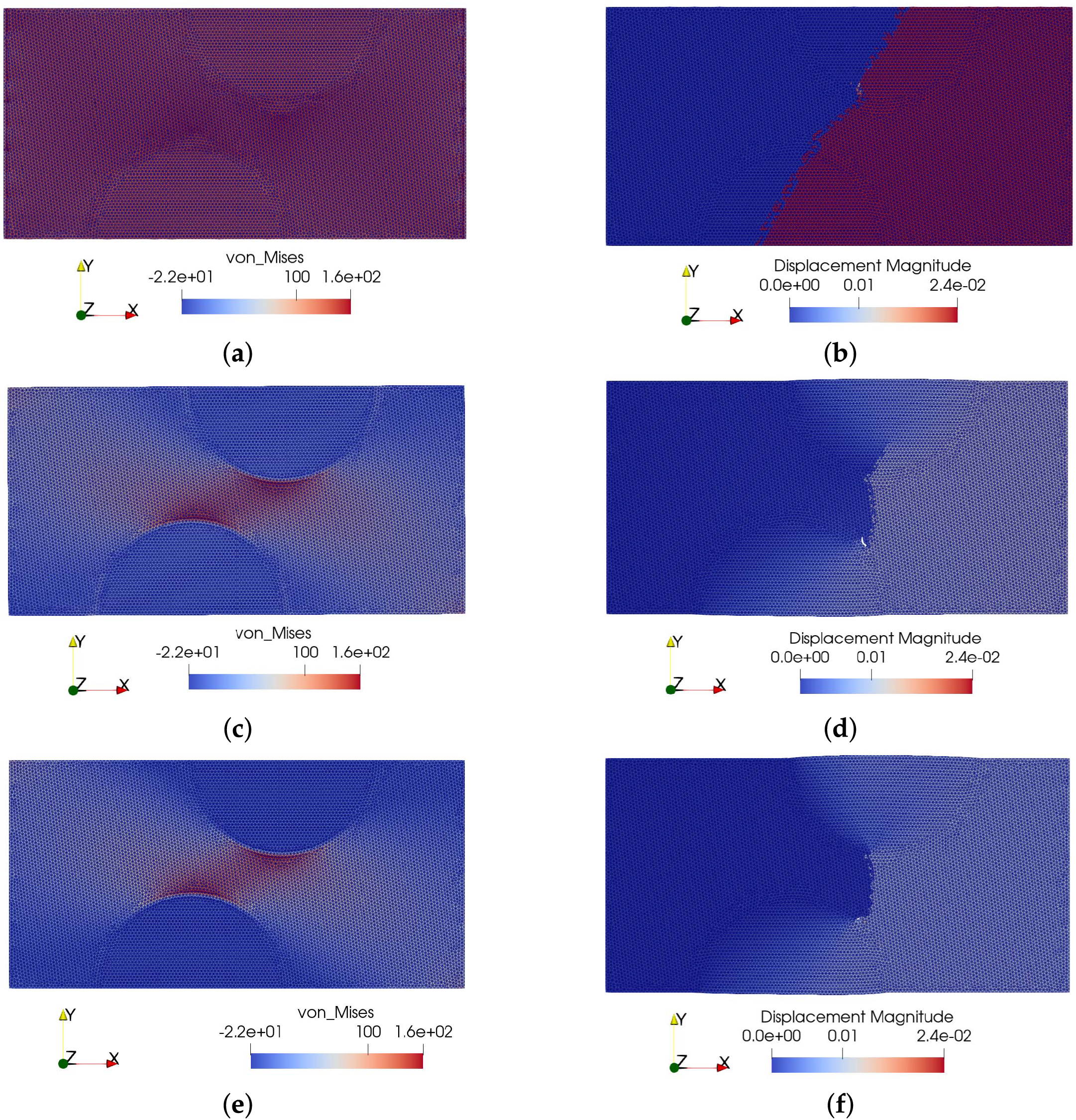

2 Material and Model Considerations

In this work, the mortar is considered the matrix, the crumb rubber is the second phase, and the mortar that incorporates the crumb rubber is the rubber-mortar composite. The elastic properties of both mortar and rubber are estimated from the literature. The Young’s modulus of mortar is assumed to be 31.5 GPa and the Poisson’s ratio equals 0.2 [36,38]. In the case of rubber, Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio are equal to 2 MPa and 0.49, respectively [38]. Rubber inclusions are supposed to be spherical and randomly distributed. This preliminary modeling decision serves as an idealization and can be regarded as an initial effort to represent the effective elastic properties of granular composites distributed randomly [39]. Due to the ease of their production, crumb rubber with a diameter of

This section presents the application of three families of homogenization schemes to estimate the elastic modulus of the rubberized mortar: i) analytical methods (Voigt, Reuss, and distributed) coded in MATLAB; ii) mean-field (MF) approaches (Mori-Tanaka and Double Inclusion) implemented in DIGIMAT-MF; and iii) periodic homogenization using DIGIMAT-FE and ANSYS. The study considers various replacement weight fractions, while the geometry and elastic properties of mortar and rubber are defined as described in Section 2. The results are compared with the experimental data reported by Nguyen et al. [36]. The influence of the ITZ on the elastic modulus is also addressed through a periodic homogenization approach.

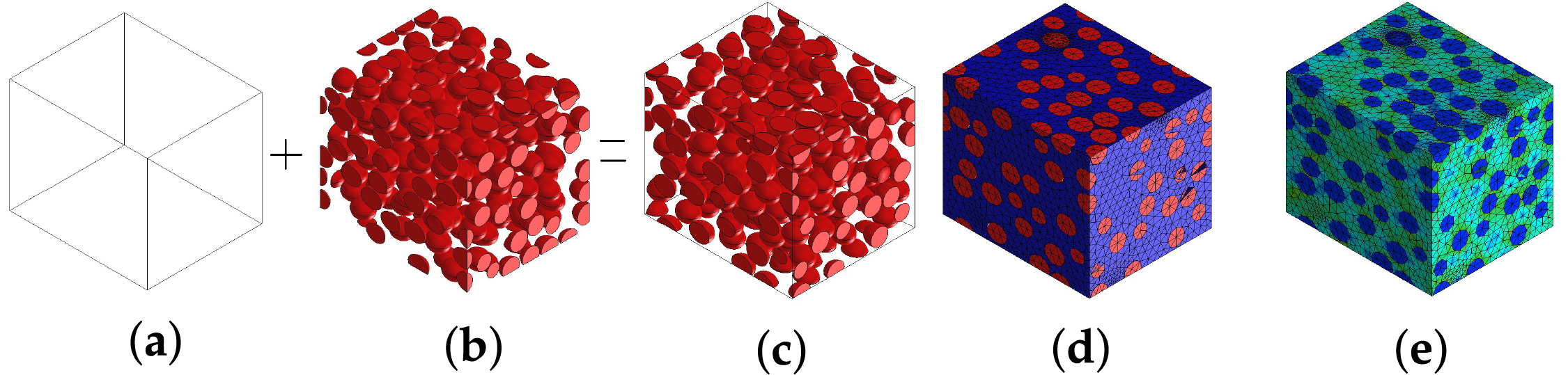

Homogenization techniques allow one to estimate the effective elastic properties from knowledge of the constitutive laws, geometry, and spatial orientation of the constituents. For this, the global behavior is supposed to be equivalent to the volumetric average of a representative volume element (RVE)—the smallest volume over which a measurement can be made that yields a representative value of the whole. The simplest homogenization methods are Voigt [40] and Reuss [41]. The Voigt model assumes that the strain field is uniform, while Reuss assumes that the stress field is uniform in the RVE. Then, the elastic moduli of the composite are identified as the upper (Voigt) and lower (Reuss) bounds. An approximation within these bounds is the distributed-phase model. These methods are analytical and therefore easily implemented, but do not take into account the shape or orientation of inclusions. Their direct expressions can be found in [42]. MF homogenization schemes—such as Mori-Tanaka (MT) [43] or Double Inclusion (DI) [44]—are more sophisticated analytical models, based on the solution of Eshelby [45], providing reasonable accuracy for reinforcements that can be approximated as ellipsoids. Alternatively, computational homogenization methods have also been developed in recent years [46]. In these approaches, finite element (FE) simulations are used to solve boundary value problems on a meshed RVE (see Fig. 1). Various types of boundary conditions can be derived from the adopted micro-macro averaging relation, but periodic boundary conditions have proven to be the most versatile.

Figure 1: Computational homogenization scheme, corresponding to (a) mortar, (b) rubber, (c) RVE, (d) FE mesh and (e) FE simulation

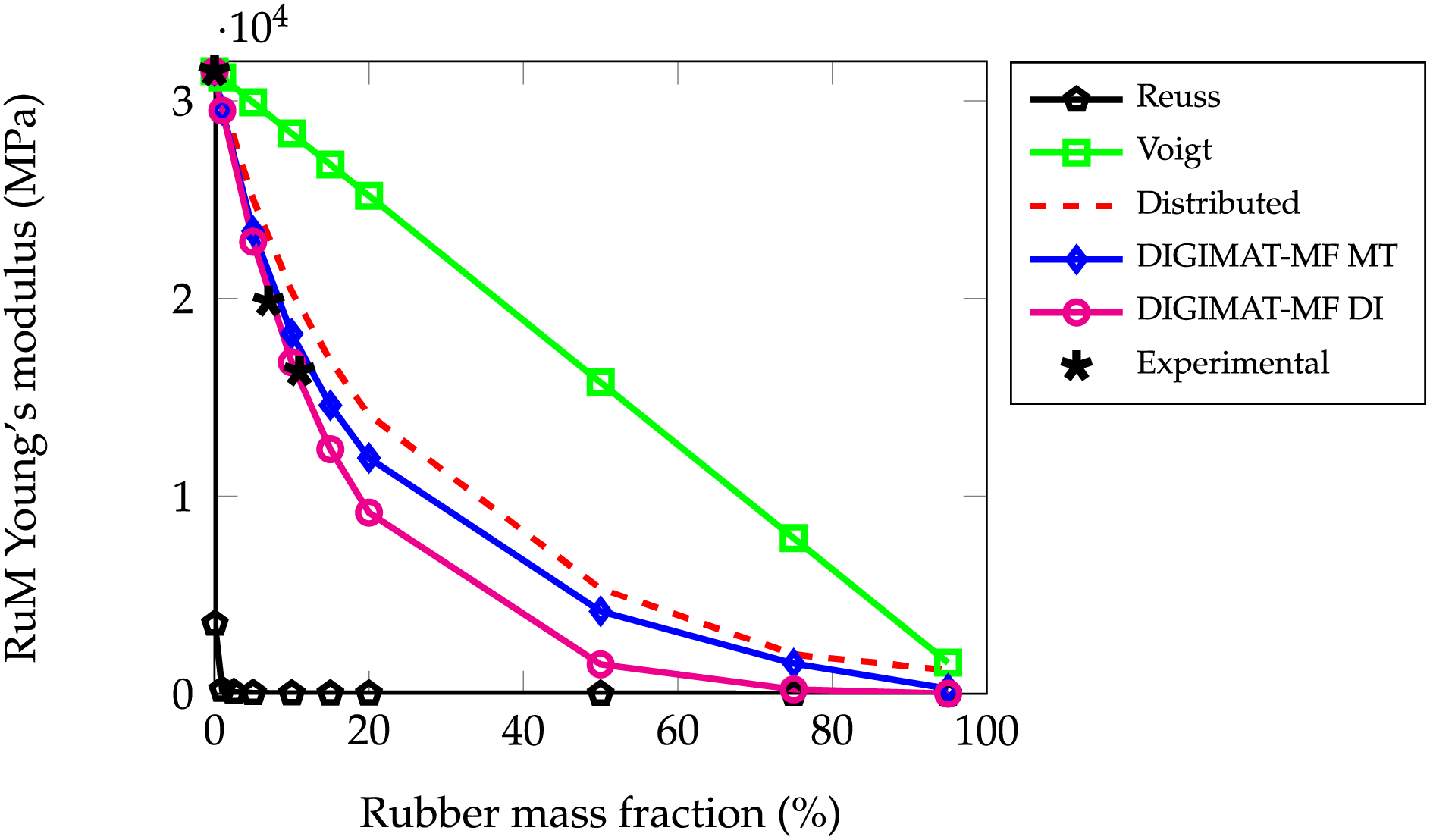

The results are shown in Fig. 2, where the elastic modulus of the rubber-mortar composite is obtained ranging from 1% to 95% the weight fraction of rubber. It is confirmed that the Voigt model is a better approach than Reuss when the stiffness of the matrix is greater than that of inclusion [47]. The distributed homogenization behaves in a way similar to that offered by DIGIMAT-MF. The mean field double inclusion homogenization (MF-DI) appears to have the closest concordance with the experimental Young’s modulus.

Figure 2: Rubberized mortar Young’s modulus according to the rubber weight fraction for analytical and MF homogenization methods. Experimental data from [36]

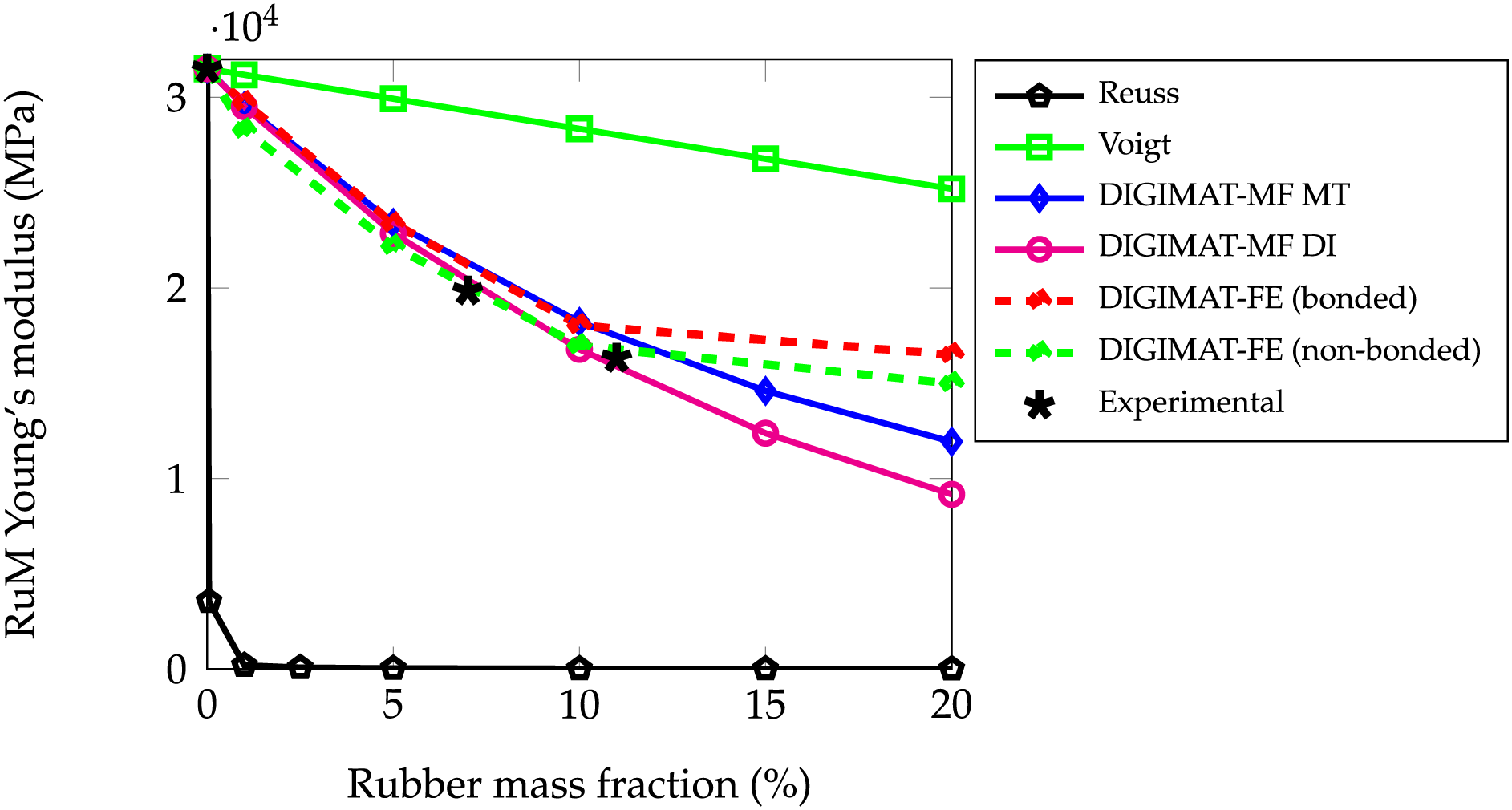

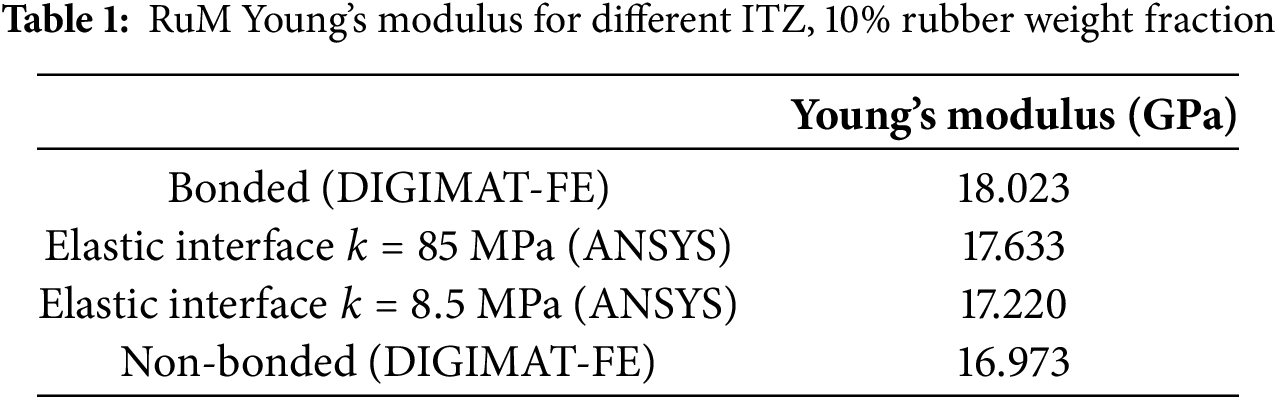

To analyze the influence of the ITZ, a finite element homogenization is performed with periodic boundary conditions. The Young’s modulus of the rubber-mortar composite is obtained for a fully bonded ITZ and for an ITZ with no adhesion. In order to overcome numerical difficulties when taking into account contact in a RVE with a large number of randomly distributed inclusions, a single inclusion RVE is considered here. Fig. 3 shows the RuM homogenized elastic modulus for 1% to 20% rubber weight fraction, including two DIGIMAT-FE simulations: the perfectly idealized bonded mortar/rubber ITZ and the totally debonded interface. Therefore, the non-bonded ITZ configuration implicitly represents the stress relief and local stiffness loss caused by micro-voids entrapped at the rubber-mortar interface. Throughout the entire replacement range, the bonded curve remains

Figure 3: Rubberized mortar Young’s modulus according to the percentage of rubber (0% to 20% by wt.) for different homogenization methods. Experimental data from [36]

4 Linear Elastic Fracture Analysis

To know the crack propagation tendency of the rubber-mortar composites, linear fracture mechanics allows calculating the stress intensity factor (K), defined from the elastic field stress that surrounds the end of a crack. ANSYS proposes to solve crack growth problems using the SMART method, which is based on the unstructured meshing method and includes the calculation of the stress intensity factor. SMART automatically updates the crack mesh when there are variations in the crack tip, at each time increment. If the stress intensity factor reaches the critical value (

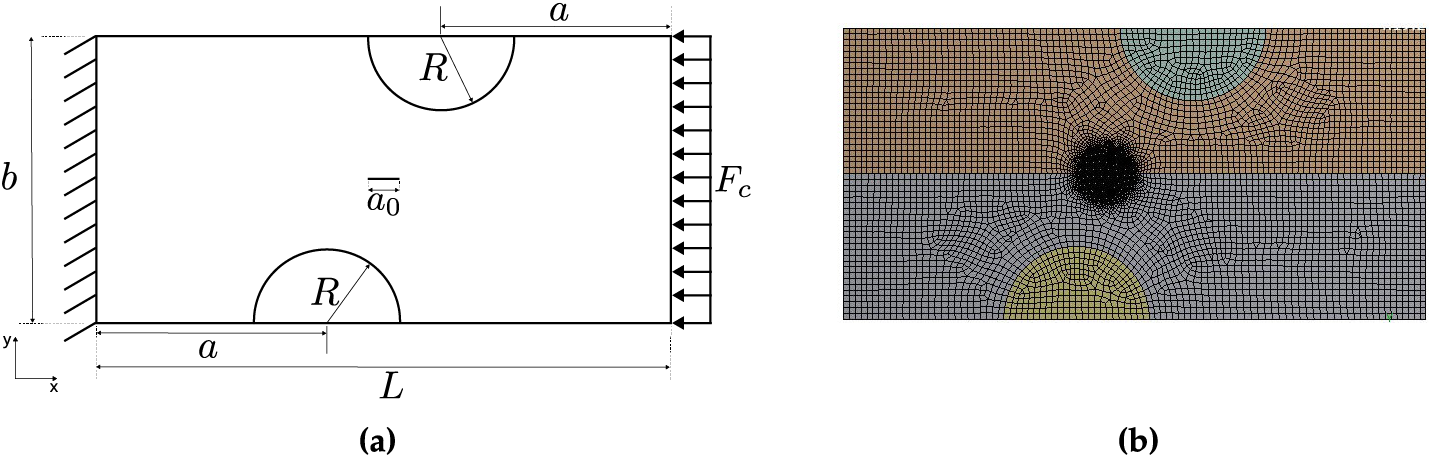

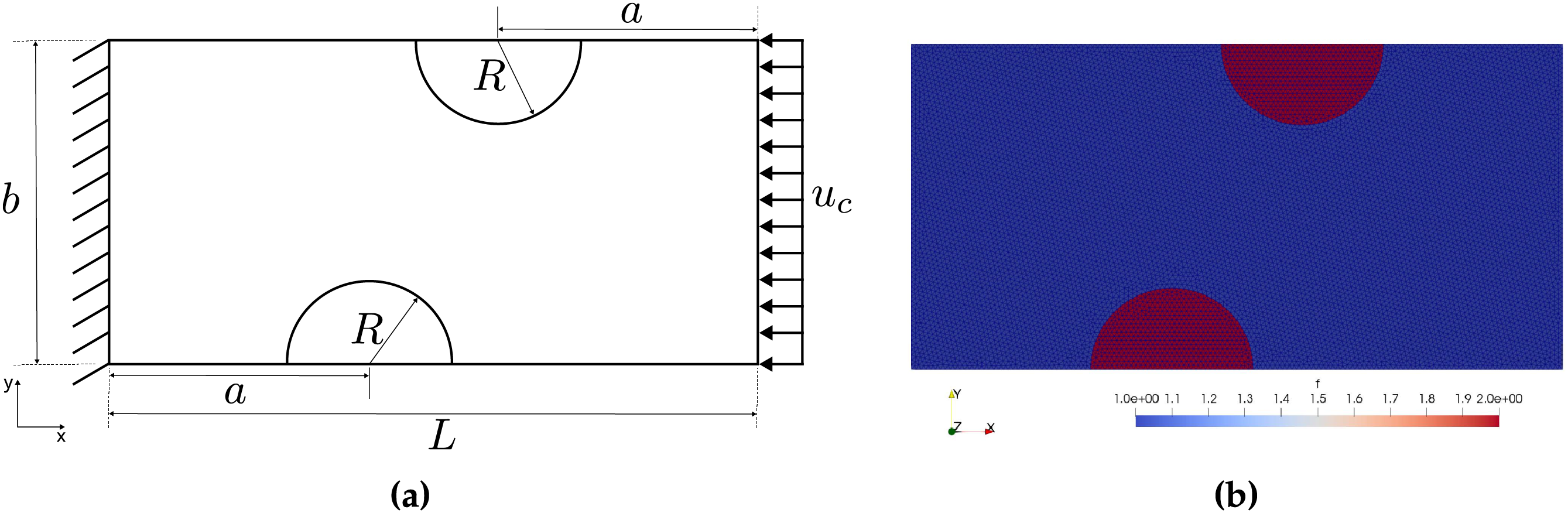

To investigate this behavior, compression tests were carried out inspired by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) C39 standard and the work of Guinea et al. [37]. Due to computational limitations, only a representative 2D sample made of a mortar matrix containing two half-circular inclusions of radius R was considered, as depicted in Fig. 4. The dimensions

Figure 4: Stress intensity factor simulation: (a) Geometry and boundary conditions and (b) FE mesh

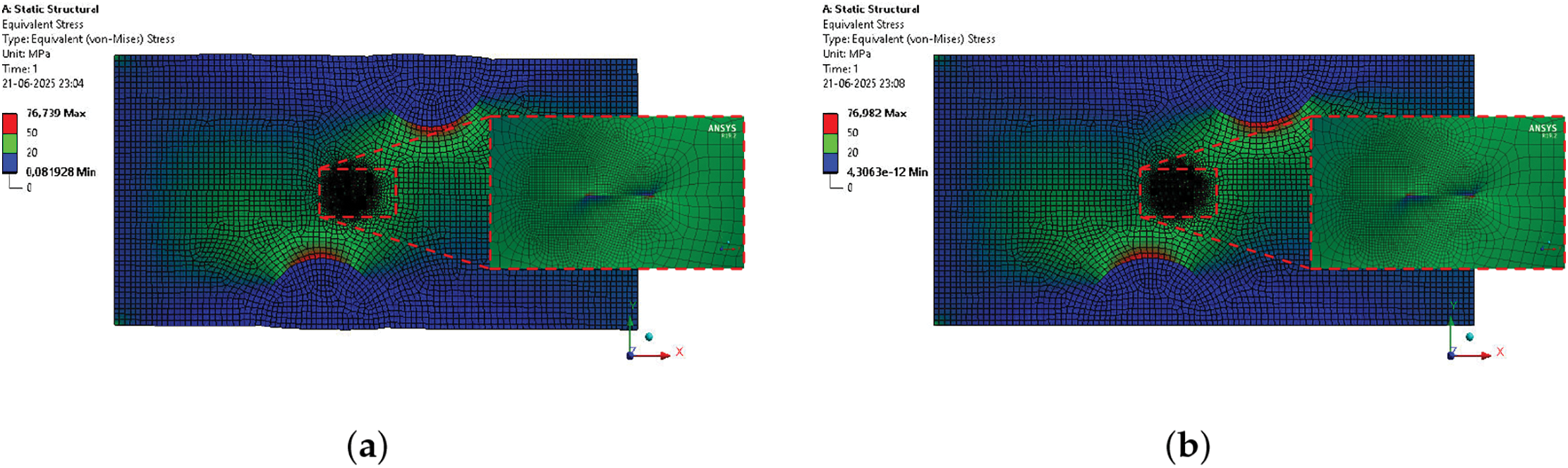

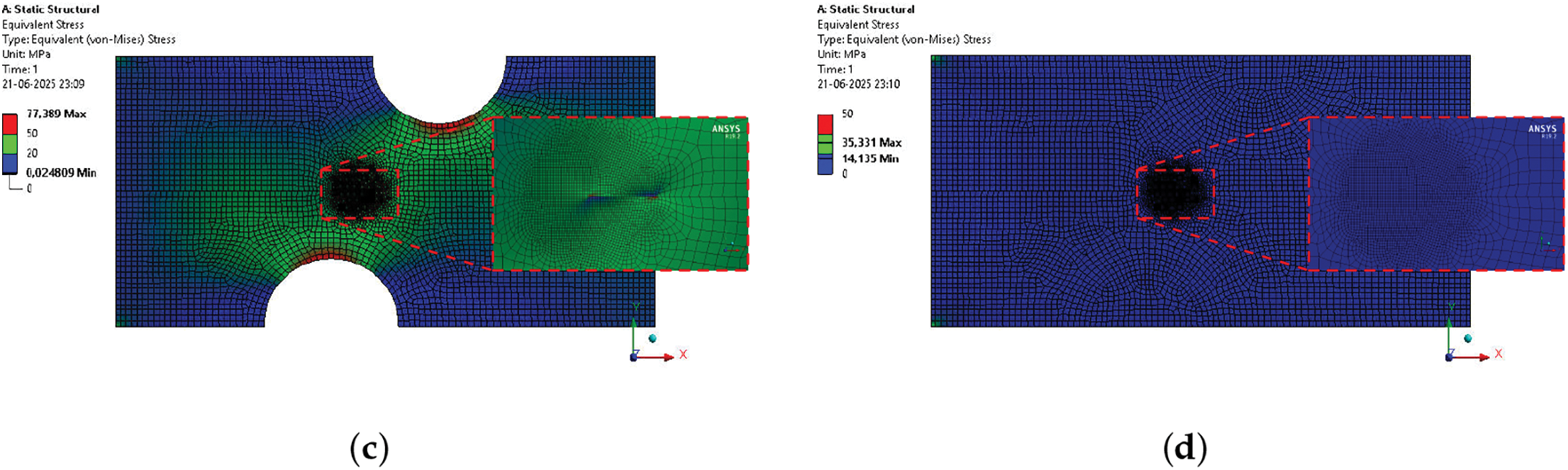

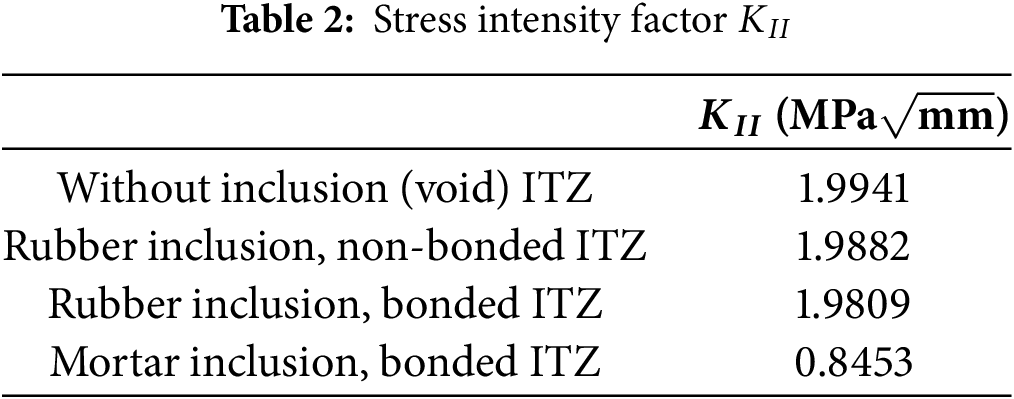

Fig. 5 presents the von Mises stress field for each inclusion-ITZ configuration, and Table 2 lists the corresponding mode-II stress-intensity factors. The bonded rubber-mortar composite shows only a marginally lower

Figure 5: Stress intensity factor simulation: RuC with 10% rubber by wt. (a) with bonded ITZ and (b) with non-bonded ITZ, (c) without inclusion (void) and (d) a homogeneous mixture of mortar with bonbed ITZ

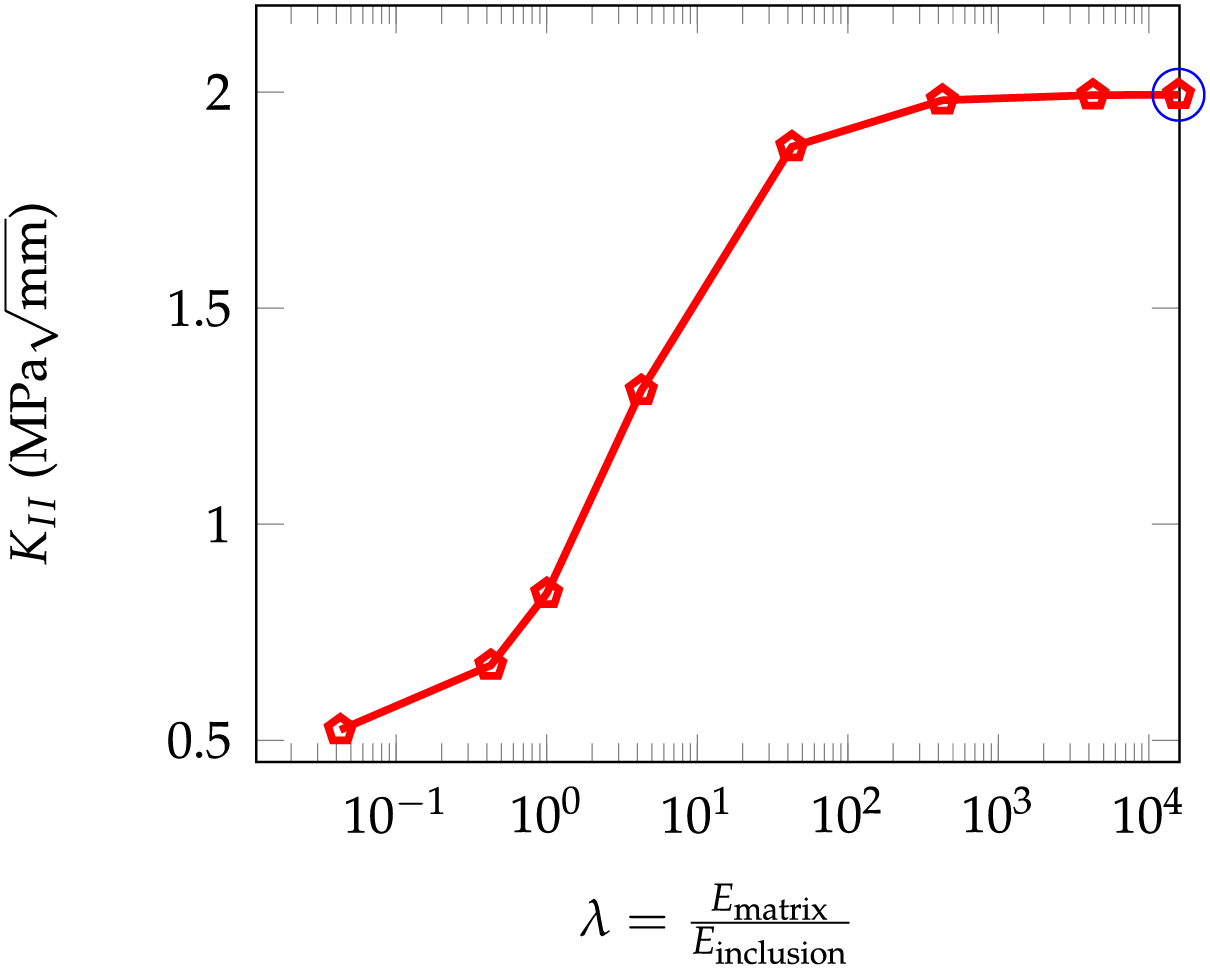

In Fig. 6, the stress intensity factor is plotted as a function of the elastic moduli ratio between the two constituents

Figure 6: Stress intensity factor

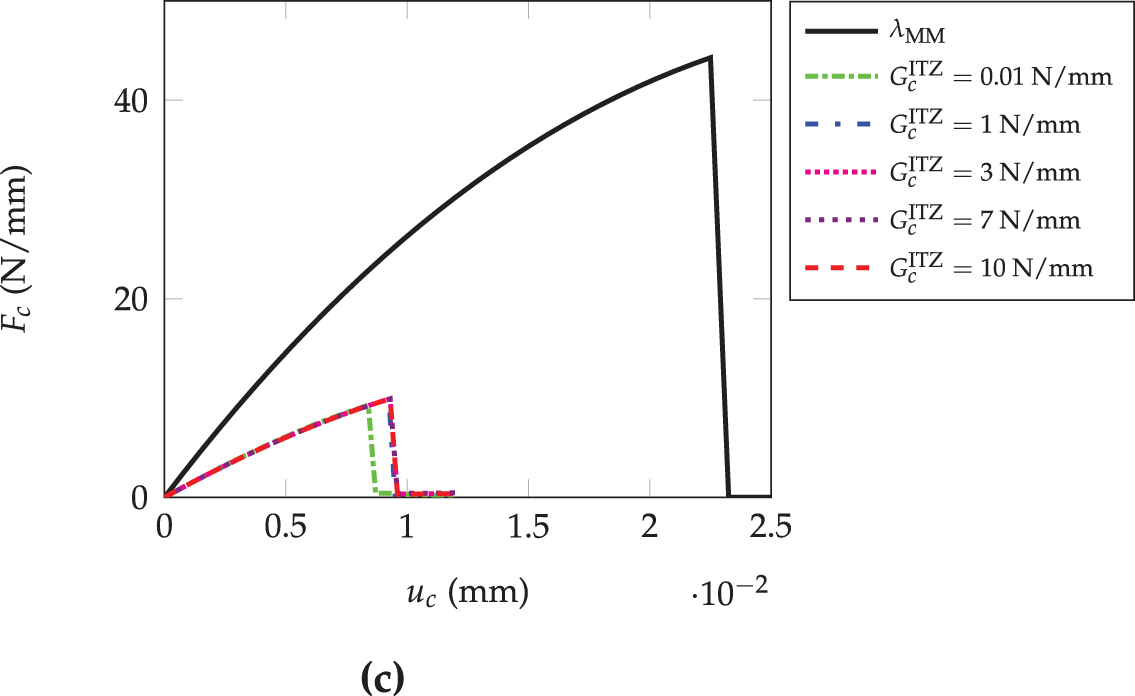

This section is devoted to the prediction of the compressive strength

Figure 7: Compression test: (a) Geometry and boundary conditions and (b) FE mesh

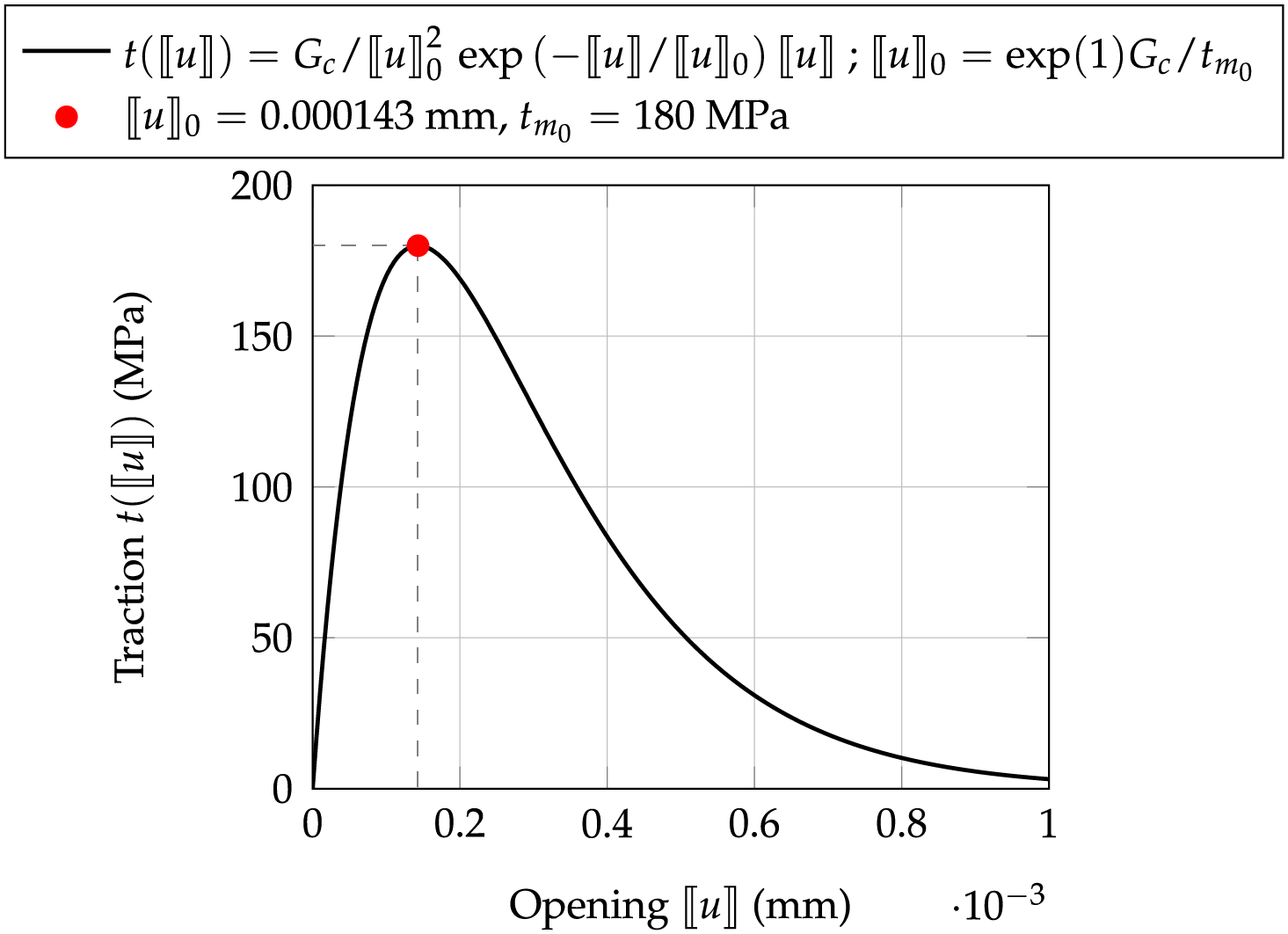

To solve this non-linear fracture simulation, a discontinuous finite element method is proposed allowing for cohesive zone modeling in the FEniCS software, based on a discontinuous Galerkin interpolation of the displacement field (see details in [49]) and an implementation proposed by [50]. For each percentage of rubber, an unstructured mesh with 21,228, 21,078 and 21,140 linear triangular elements is taken into account, respectively (see Fig. 7b). Cohesive elements are considered along all internal facets of the mesh. They are characterized by discontinuous displacement and can transmit forces through the interface. The link between the interface opening (displacement jump

Figure 8: Exponential traction separation law

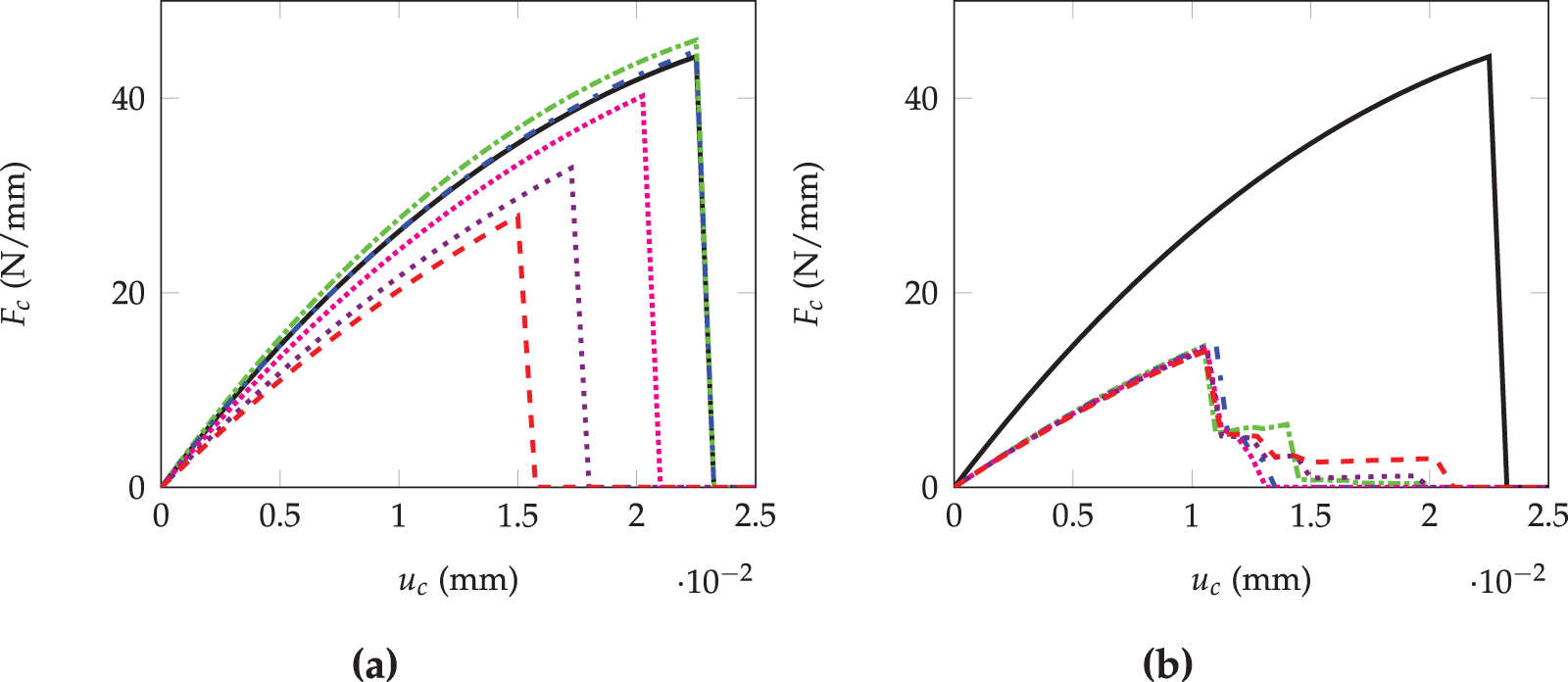

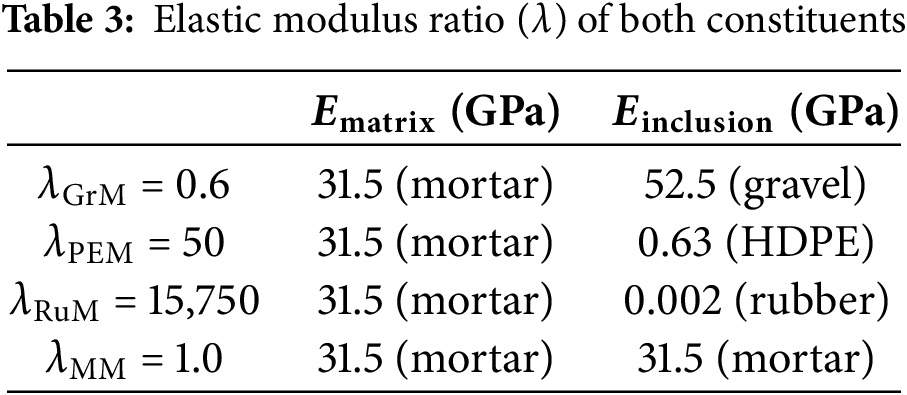

The compressive strength of rubberized mortar with

Figure 9: Compression force vs. compression displacement for different aggregates (

Figure 10: Compression strength vs. critical energy release rate for different aggregates (

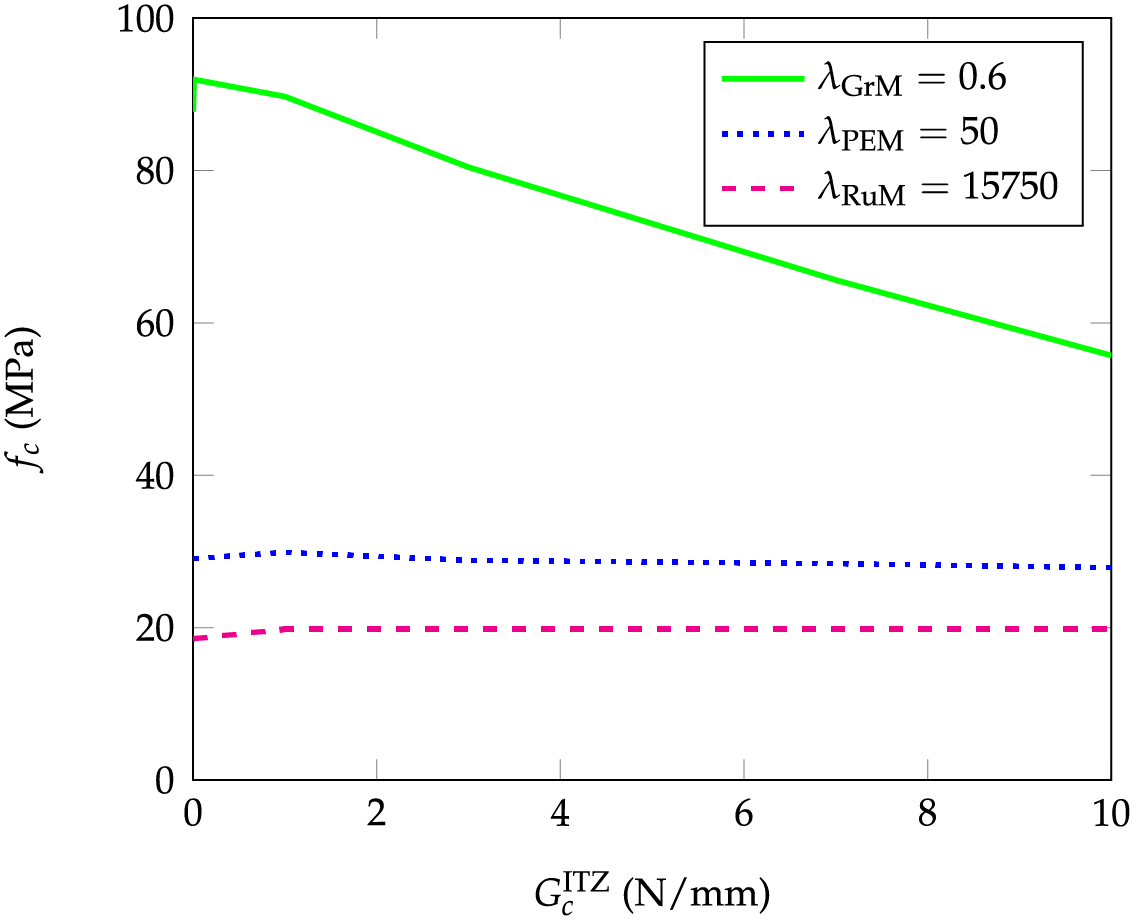

For further analysis, Fig. 11 shows the stress fields and deformations before and after failure, respectively. The mortal gravel composite is observed to have a typical brittle fracture mode through a

Figure 11: Pre-failure von Mises stress field (MPa) and post-failure deformation for different aggregates (

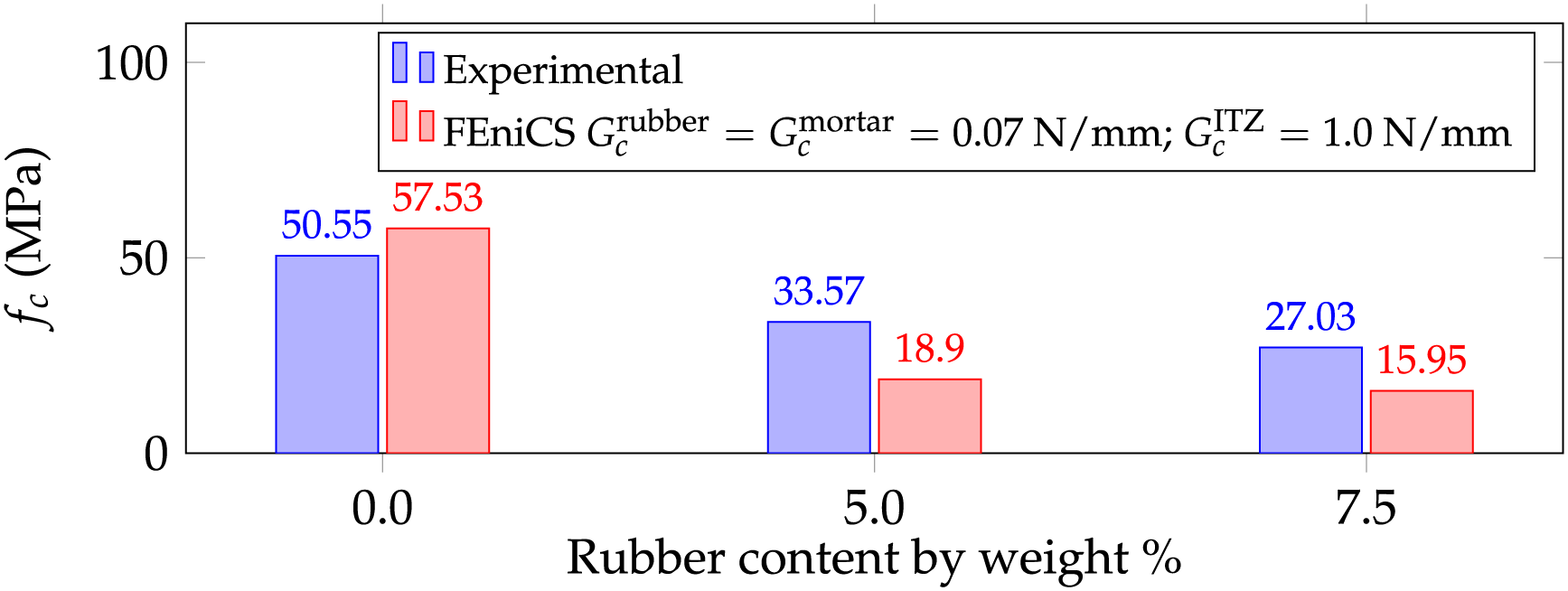

The predicted compression strength of rubberized mortar with 0%, 5%, 7.5% by weight of rubber is compared to the experimental results of García et al. [19], in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: Compressive strength of RuM with different % of rubber by weight. Experimental data from [19]

Homogenization techniques to estimate the elastic properties of rubberized mortar have been studied, including three main approaches: analytical methods (Voigt, Reuss, and distributed), mean-field approaches (Mori-Tanaka and Double Inclusion) and periodic homogenization using finite element simulations. The results show that the distributed and mean-field homogenization results align closely with the experimental findings, particularly the mean-field double inclusion method. Furthermore, periodic homogenization was used to quantify the influence of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ). The findings indicate that there is merely a 6% change in the elastic modulus when comparing perfectly bonded interfaces to fully debonded ones, with the bonded ITZ offering the greatest stiffness. In practice, X-ray computed tomography could be used to map the pore network around rubber particles and indirectly estimate the effective thickness of the ITZ. Integrating these scans into the present mesomodel would sharpen the predictions of void content and ITZ size, although only incremental gains are expected. However, such data would establish indicative bounds for acceptable porosity levels and realistic ITZ thickness in rubberized mortars. From another perspective concerning homogenization and ITZ influence, Guo et al. [51] recently showed that shape-induced anisotropy is negligible when stiff inclusions are embedded in a compliant cement paste; our case is the opposite: highly compliant rubber particles within a stiff mortar matrix. Under such conditions, the geometry of the particles could become more influential, particularly if the rubber grains are elongated or exhibit a preferred orientation. We therefore flag a detailed shape-sensitivity analysis, coupling ellipsoidal inclusions with orientation statistics, as a key objective for future work.

The propagation of the crack using linear fracture mechanics was also addressed to calculate the stress intensity factor, which determines the tendency to growth of the crack. The results reveal that

Finally, the compressive strength for three aggregates (rubber, HDPE, gravel) was predicted, evaluating the impact of the ITZ fracture energy. For that proposal, a discontinuous finite element method was employed using FEniCS software. The results indicate that the compressive strength of RuM is not affected by the ITZ fracture energy. However, a higher elastic modulus of the aggregates results in an increased compressive strength. Crack patterns vary, with pure mortar showing a brittle fracture mode, while cracks in RuM form around stress concentration zones. Comparisons with experimental results show that the predictions align well with the compressive strengths observed. From these simulations, it is important to emphasize that while improving the adhesion of mortar/rubber offers limited improvements in the resistance to fracture, the key lies in optimizing the stiffness ratio of the components to improve the resistance to crack propagation. Taken together, these findings provide the first coherent numerical proof that the tuning of the intrinsic stiffness of the rubber is a more powerful lever than the improvement of adhesion to achieve tougher and stronger rubberized mortars.

This study overturns the customary emphasis on mortar-rubber adhesion, showing, through a mesoscale numerical framework, that increasing the intrinsic stiffness of the rubber phase is the most effective route to increased fracture toughness and compressive strength. Consequently, research and industrial efforts should prioritize strategies for stiffening recycled rubber (e.g., targeted crosslinking, hybrid fillers, or thermal pretreatments), while relegating adhesion enhancement to a complementary role when a pronounced stiffness mismatch is present.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Cristian Martínez-Fuentes acknowledges the support from University of Talca, Guillermo Blanco’s scholarship. Pedro Pesante acknowledges the financial support from the Chilean National Agency for Research and Development (ANID), National Doctorate No. 21212028. Karin Saavedra acknowledges the financial support from ANID, FONDECYT Regular Research Project No. 1221793.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Cristian Martínez-Fuentes and Pedro Pesante; Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Paul Oumaziz; Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Karin Saavedra. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Valentini F, Pegoretti A. End-of-life options of tyres. A review. Adv Ind Eng Polym Res. 2022;5(4):203–13. doi:10.1016/j.aiepr.2022.08.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Dabic-Miletic S, Simic V, Karagoz S. End-of-life tire management: a critical review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28(48):68053–70. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16263-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lo Presti D. Recycled Tyre Rubber Modified Bitumens for road asphalt mixtures: a literature review. Constr Build Mater. 2013;49(1):863–81. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.09.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Qaidi SMA, Dinkha YZ, Haido JH, Ali MH, Tayeh BA. Engineering properties of sustainable green concrete incorporating eco-friendly aggregate of crumb rubber: a review. J Clean Prod. 2021;324(2):129251. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Qaidi SMA, Mohammed AS, Ahmed HU, Faraj RH, Emad W, Tayeh BA, et al. Rubberized geopolymer composites: a comprehensive review. Ceram Int. 2022;48(17):24234–59. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.06.123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ul Islam MM, Li J, Roychand R, Saberian M, Chen F. A comprehensive review on the application of renewable waste tire rubbers and fibers in sustainable concrete. J Clean Prod. 2022;374(1):133998. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Maderuelo-Sanz R, Nadal-Gisbert AV, Crespo-Amorós JE, Parres-García F. A novel sound absorber with recycled fibers coming from end of life tires (ELTs). Appl Acoust. 2012;73(4):402–8. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2011.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang X, Lu Z, Tian D, Li H, Lu C. Mechanochemical devulcanization of ground tire rubber and its application in acoustic absorbent polyurethane foamed composites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2013;127(5):4006–14. doi:10.1002/app.37721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Siddika A, Mamun MAA, Alyousef R, Amran YHM, Aslani F, Alabduljabbar H. Properties and utilizations of waste tire rubber in concrete: a review. Constr Building Mater. 2019;224:711–31. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.07.108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ganjian E, Khorami M, Maghsoudi AA. Scrap-tyre-rubber replacement for aggregate and filler in concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2009;23(5):1828–36. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.09.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li L, Ruan S, Zeng L. Mechanical properties and constitutive equations of concrete containing a low volume of tire rubber particles. Constr Build Mater. 2014;70(1):291–308. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.07.105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Thomas BS, Gupta RC. A comprehensive review on the applications of waste tire rubber in cement concrete. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2016;54(6):1323–33. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Roychand R, Gravina RJ, Zhuge Y, Ma X, Youssf O, Mills JE. A comprehensive review on the mechanical properties of waste tire rubber concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2020;237(10):117651. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Momotaz H, Rahman MM, Karim MR, Zhuge Y, Ma X, Levett P. Properties of the interfacial transition zone in rubberised concrete–an investigation using nano-indentation and EDS analysis. J Build Eng. 2023;77:107405. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. He L, Ma Y, Liu Q, Mu Y. Surface modification of crumb rubber and its influence on the mechanical properties of rubber-cement concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2016;120(Part B):403–7. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.05.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tran TQ, Skariah Thomas B, Zhang W, Ji B, Li S, Brand AS. A comprehensive review on treatment methods for end-of-life tire rubber used for rubberized cementitious materials. Constr Build Mater. 2022;359:129365. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Islam MMU, Li J, Wu YF, Roychand R, Saberian M. Design and strength optimization method for the production of structural lightweight concrete: an experimental investigation for the complete replacement of conventional coarse aggregates by waste rubber particles. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2022;184(1):106390. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Singh P, Singh DN, Debbarma S. Macro- and micro- mechanisms associated with valorization of waste rubber in cement-based concrete and thermoplastic polymer composites: a critical review. Constr Build Mater. 2023;371(4):130807. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. García E, Villa B, Pradena M, Urbano B, Campos-Requena VH, Medina C, et al. Experimental evaluation of cement mortars with end-of-life tyres exposed to different surface treatments. Crystals. 2021;11(5). doi:10.3390/cryst11050552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xu J, Yao Z, Yang G, Han Q. Research on crumb rubber concrete: from a multi-scale review. Constr Build Mater. 2020;232(10):117282. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xiong W, Wu L, Wang L, Zhou C, Lu Y. A finite element analysis method for random fiber-aggregate 3D mesoscale concrete based on the crack bridging law. J Build Eng. 2024 Nov;96(12):110674. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Felipe dos Santos Ribeiro L, Mejia C, Roehl D. Multiphase and mesoscale analysis of the mechanical behavior of fiber reinforced concrete. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2023 Jun;125(4):103929. doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.103929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bažant ZP, Tabbara MR, Kazemi MT, Pijaudier-Cabot G. Random particle model for fracture of aggregate or fiber composites. J Eng Mech. 1990;116(8):1686–705. doi:10.1061/(asce)0733-9399(1990)116:8(1686). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Cusatis G, Bažant ZP, Cedolin L. Confinement-shear lattice model for concrete damage in tension and compression: ii. computation and validation. J Eng Mech. 2003;129(12):1449–58. doi:10.1061/(asce)0733-9399(2003)129:12(1449). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu JX, Deng SC, Zhang J, Liang NG. Lattice type of fracture model for concrete. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2007;48(3):269–84. doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2007.08.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhu Z, Troemner M, Wang W, Cusatis G, Zhou Y. Lattice discrete particle modeling of the cycling behavior of strain-hardening cementitious composites with and without fiber reinforced polymer grid reinforcement. Compos Struct. 2023 Oct;322(3):117346. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2023.117346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Schorn H, Rode U. Numerical simulation of crack propagation from microcracking to fracture. Cem Concr Compos. 1991;13(2):87–94. doi:10.1016/0958-9465(91)90003-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wriggers P, Moftah SO. Mesoscale models for concrete: homogenisation and damage behaviour. Finite Elem Anal Des. 2006;42(7):623–36. doi:10.1016/j.finel.2005.11.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wu Z, Zhang J, Fang Q, Yu H, Haiyan M. Mesoscopic modelling of concrete material under static and dynamic loadings: a review. Constr Build Mater. 2021;278(10):122419. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Du X, Jin L, Ma G. Numerical modeling tensile failure behavior of concrete at mesoscale using extended finite element method. Int J Damage Mech. 2014;23(7):872–98. doi:10.1177/1056789513516028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Paul K, Balu AS, BabuNarayan KS. Fracture mechanics-based meshless method for crack propagation in concrete structures. Structures. 2025 Apr;74:108422. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2025.108422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Delgado JMPQ, Xie ZH, Guo YC, Yuan QZ, Huang PY. Mesoscopic numerical computation of compressive strength and damage mechanism of rubber concrete. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2015;2015:279584. [Google Scholar]

33. Duarte APC, Silvestre N, de Brito J, Júlio E. Numerical study of the compressive mechanical behaviour of rubberized concrete using the eXtended Finite Element Method (XFEM). Compos Struct. 2017;179(6):132–45. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.07.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao X, Dong Q, Chen X, Ni F. Meso-cracking characteristics of rubberized cement-stabilized aggregate by discrete element method. J Clean Prod. 2021;316(3):128374. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Alnaes MS, Blechta J, Hake J, Johansson A, Kehlet B, Logg A, et al. The FEniCS Project Version 1.5. Arch NumerSoftw. 2015;3:9–23. [Google Scholar]

36. Nguyen TH, Toumi A, Turatsinze A. Mechanical properties of steel fibre reinforced and rubberised cement-based mortars. Mater Des. 2010;31(1):641–7. [Google Scholar]

37. Guinea GV, El-Sayed K, Rocco CG, Elices M, Planas J. The effect of the bond between the matrix and the aggregates on the cracking mechanism and fracture parameters of concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2002;32(12):1961–70. doi:10.1016/s0008-8846(02)00902-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Belabdelouahab F, Trouzine H, Hellal H, Rahali B, Kaci SO, Medine M. Comparative analysis of estimated young’s modulus of rubberized mortar and concrete. Int J Civ Eng. 2018;16(2):243–53. doi:10.1007/s40999-016-0119-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Pesante P, Saavedra K, Pincheira G. Mechanical properties of a wood flour-PET composite through computational homogenisation. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;67(3):4061–79. [Google Scholar]

40. Voigt W. Ueber die Beziehung zwischen den beiden Elasticitätsconstanten isotroper Körper. Annalen der Physik. 1889;274(12):573–87. (In German). doi:10.1002/andp.18892741206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Reuss A. Berechnung der Fließgrenze von Mischkristallen auf Grund der Plastizitätsbedingung für Einkristalle. ZAMM-J Appl Math Mech/Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik. 1929;9(1):49–58. doi:10.1002/zamm.19290090104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Topçu IB, Avcular N. Analysis of rubberized concrete as a composite material. Cem Concr Res. 1997;27(8):1135–9. doi:10.1016/s0008-8846(97)00115-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Mori T, Tanaka K. Average stress in matrix and average elastic energy of materials with misfitting inclusions. Acta Metallurgica. 1973;21(5):571–4. doi:10.1016/0001-6160(73)90064-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Hori M, Nemat-Nasser S. Double-inclusion model and overall moduli of multi-phase composites. Mech Mater. 1993;14(3):189–206. doi:10.1016/0167-6636(93)90066-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Eshelby JD. The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc Royal Soc Lond Ser A, Math Phys Sci. 1957;241(1226):376–96. doi:10.1098/rspa.1957.0133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Geers MGD, Kouznetsova VG, Brekelmans WAM. Multi-scale computational homogenization: trends and challenges. J Comput Appl Math. 2010;234(7):2175–82. doi:10.1016/j.cam.2009.08.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Falzone G, Falla GP, Wei Z, Zhao M, Kumar A, Bauchy M, et al. The influences of soft and stiff inclusions on the mechanical properties of cementitious composites. Cem Concr Compos. 2016;71:153–65. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2016.05.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Barbero EJ. Finite element analysis of composite materials using ANSYS®. In: Composite materials. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

49. Hansbo P, Salomonsson K. A discontinuous Galerkin method for cohesive zone modelling. Finite Elem Anal Des. 2015;102–103(247):1–6. doi:10.1016/j.finel.2015.04.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Bleyer J. Numerical tours of computational mechanics with FEniCSx. Zenodo; 2024. [Google Scholar]

51. Guo Y, Zhou T, Vasoya M, Lagoudas D, Birgisson B. Micromechanics modeling of cement concrete considering the interaction among randomly oriented ellipsoidal inhomogeneities. Constr Build Mater. 2024;438(1):137193. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools