Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Differential Privacy Integrated Federated Learning for Power Systems: An Explainability-Driven Approach

1 State Grid Information & Telecommunication Co of SEPC, Taiyuan, 030021, China

2 Department of Computer Science, Technische Universität Dortmund, Dortmund, 44227, Germany

* Corresponding Author: Junwei Ma. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 983-999. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065978

Received 26 March 2025; Accepted 24 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

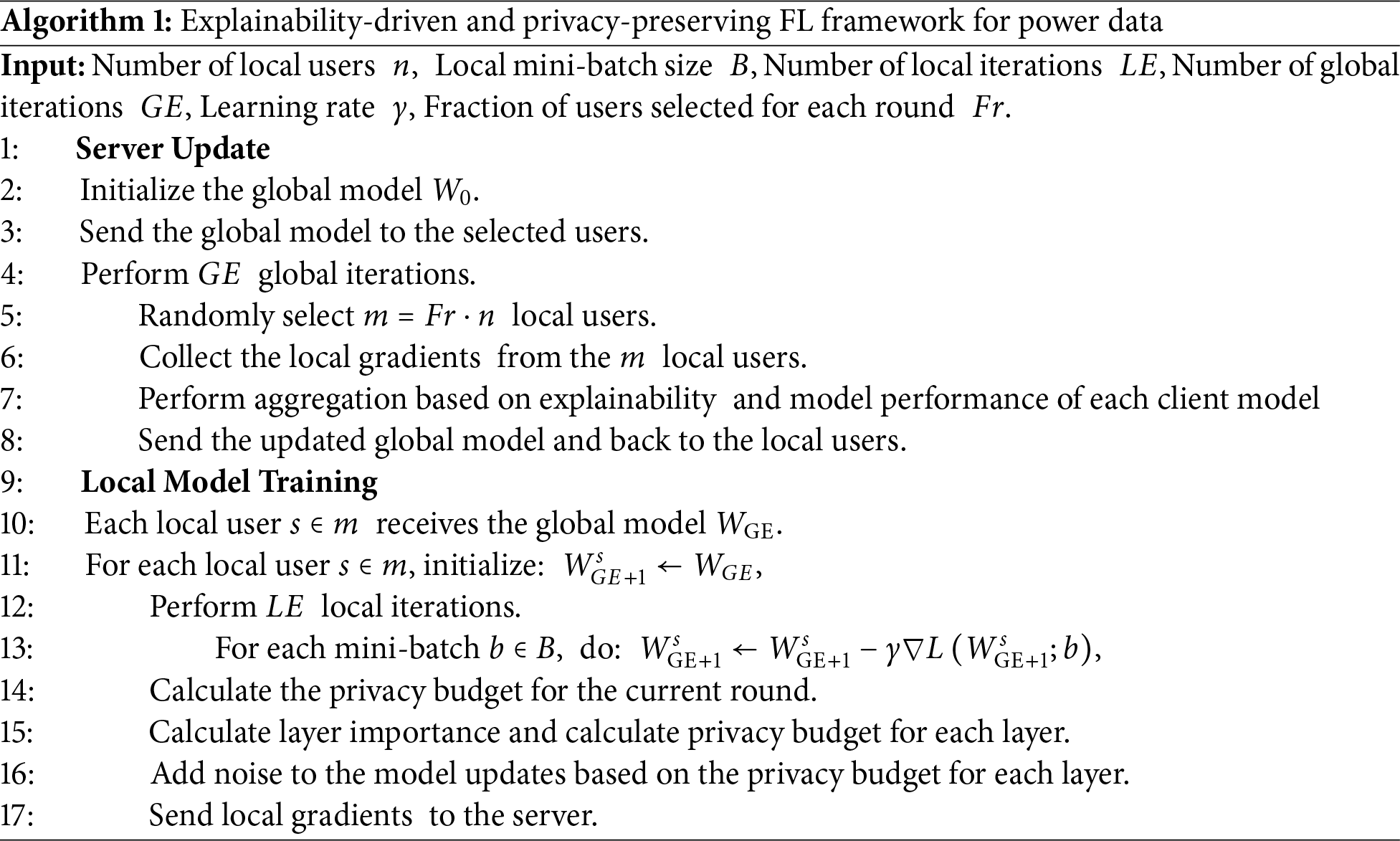

With the ongoing digitalization and intelligence of power systems, there is an increasing reliance on large-scale data-driven intelligent technologies for tasks such as scheduling optimization and load forecasting. Nevertheless, power data often contains sensitive information, making it a critical industry challenge to efficiently utilize this data while ensuring privacy. Traditional Federated Learning (FL) methods can mitigate data leakage by training models locally instead of transmitting raw data. Despite this, FL still has privacy concerns, especially gradient leakage, which might expose users’ sensitive information. Therefore, integrating Differential Privacy (DP) techniques is essential for stronger privacy protection. Even so, the noise from DP may reduce the performance of federated learning models. To address this challenge, this paper presents an explainability-driven power data privacy federated learning framework. It incorporates DP technology and, based on model explainability, adaptively adjusts privacy budget allocation and model aggregation, thus balancing privacy protection and model performance. The key innovations of this paper are as follows: (1) We propose an explainability-driven power data privacy federated learning framework. (2) We detail a privacy budget allocation strategy: assigning budgets per training round by gradient effectiveness and at model granularity by layer importance. (3) We design a weighted aggregation strategy that considers the SHAP value and model accuracy for quality knowledge sharing. (4) Experiments show the proposed framework outperforms traditional methods in balancing privacy protection and model performance in power load forecasting tasks.Keywords

The rapid development of digital technologies has driven a profound transformation in the power industry [1,2]. As a key component of smart grids, the power system is increasingly reliant on data-driven intelligent technologies for tasks such as scheduling optimization, load forecasting, and demand-side management [3–5]. Large-scale data processing and analysis provide robust support for the optimization and automation of power systems, making their operation more efficient, flexible, and intelligent [6]. However, with the widespread use of power data, privacy issues have become increasingly prominent. Power data contains a significant amount of sensitive user information, such as electricity consumption patterns, geographic locations, living habits, and consumption preferences. If misused or leaked, this data could pose serious threats to user privacy. Therefore, as the power system becomes more intelligent, ensuring the protection of user privacy has become a critical issue that must be addressed during the data-driven transformation of the power industry [7].

Traditional privacy protection methods, such as data encryption and anonymization, often suffer from high computational overhead and low processing efficiency, making them inadequate for the real-time processing demands of large-scale power data. Federated Learning (FL), an emerging distributed machine learning method, offers an innovative solution to privacy concerns [8]. By training models locally on devices and only sharing model parameters or gradients, FL avoids the central storage and transmission of raw data, thereby reducing the risk of data leakage. FL not only improves model accuracy but also reduces bandwidth consumption during data transmission, offering significant advantages in multi-party collaborative learning.

However, in federated learning, although the central server is prevented from directly contacting user data, the server can still use gradient attacks to restore the user’s local training data from the exchanged parameter gradients. The method is to first randomly generate virtual training data and use it to generate virtual gradients, and then repeatedly iterate through gradient descent with the optimization goal of narrowing the gap between the virtual gradient and the real gradient, so as to restore the user’s private data. Therefore, relying solely on FL does not fully ensure privacy protection, especially in high-sensitivity scenarios like power data, where further enhancement of privacy protection is crucial [9].

To address this challenge, Differential Privacy (DP) has emerged as an effective privacy-preserving technique [10]. DP adds noise to the output results, ensuring that even if an attacker gains access to the model’s output, they cannot infer individual sensitive information. Integrating DP within the FL framework can effectively protect data privacy and prevent the leakage of sensitive information. There have been some works applying this method to the power field. However, existing DP methods usually rely on static noise addition strategies, which are very unfriendly to model performance. First, the privacy budget allocated in each round of training is the same, which leads to the fact that noise will have a non-negligible impact on the convergence. Then, in a multi-layer neural network model, the traditional strategy allocates the same privacy budget to each layer. However, in a multi-layer neural network model, some layers contribute more to the expressiveness of the model while others contribute less. It is unfair to allocate the same privacy budget to them.

In this context, this paper proposes an explainability-driven and privacy-preserving FL framework. Different from traditional privacy-preserving methods, this framework combines DP with model explainability analysis. The explainability in this paper mainly includes two aspects. After each client completes local training, the client calculates the layer importance of the model. We allocate larger privacy budgets to important layers to retain the knowledge of the model to a greater extent, and for unimportant layers, we allocate smaller privacy budgets to ensure the privacy of the model. Considering that noise will cause gradient distortion, on the central server, we calculate the Shapley Additive explanations (SHAP) value vector for each server’s local model, and prioritize the aggregation of local models with high SHAP value vector similarity. When aggregating, we use indicators such as model accuracy as a reference to avoid the damage of low-quality models to model aggregation.

The main innovations of this paper are: First, we propose a dynamic privacy optimization framework that combines explainability analysis and DP to achieve the best balance between privacy protection and model performance. Second, we design a strategy for allocating privacy budgets between different training rounds and different layers of the model. Then, we design an aggregation strategy based on SHAP value and model performance indicators. Finally, through theoretical analysis and experimental verification in the power load forecasting task, we demonstrate that the proposed framework not only enhances privacy protection but also improves model performance, outperforming traditional methods. Compared with static privacy protection methods, the proposed framework better addresses the trade-off between model performance and privacy protection in practical applications of power data.

To tackle the “data silos” issue in the power sector, researchers have introduced FL, a distributed learning approach that enables local model training without centralized data storage, effectively protecting user privacy. Chen et al. [11] first proposed the FL framework, demonstrating how deep neural networks can be collaboratively trained through efficient communication and local computation. This framework theoretically supports user privacy protection and reduces data transmission costs. Subsequent studies focused on FL model optimization, heterogeneity, and communication efficiency [12–14].

FL’s application in the power sector has grown, especially in smart grid management and load forecasting [15–18]. Smart grid data is often dispersed across devices and sensors, involving large amounts of private information. Thus, ensuring data privacy while achieving effective modeling and forecasting is crucial. Cheng et al. [19] discussed FL’s potential in energy systems for addressing privacy and data security concerns, highlighting its ability to enhance system performance without compromising data confidentiality. Zheng et al. [20] explored how privacy-preserving FL could improve power system services like distributed energy resource management, fault detection, and load forecasting. Husnoo et al. [21] proposed the FedDiSC framework for distinguishing disturbances and cyber-attacks in power systems, reducing computational load and enhancing resilience. Wen et al. [22] proposed a novel privacy-preserving federated learning framework for energy theft detection is proposed. A federated learning system consisting of a data center (DC), a control center (CC), and multiple detection stations is considered. This work designs a secure protocol so that the detection stations can send encrypted training parameters to CC and DC, and then CC and DC calculate the aggregate parameters using homomorphic encryption and return the updated model parameters to the detection stations. Mahmoud et al. [23] repurpose an efficient inner-product functional encryption (IPFE) scheme for implementing secure data aggregation to preserve the customers’ privacy by encrypting their models’ parameters during the FL training.

Despite FL’s privacy benefits through local data processing, it still faces data leakage risks during model parameter upload and aggregation. Malicious participants can infer sensitive data by analyzing model updates like gradients or weights. Zhu et al. [24] showed that gradient updates in FL could leak participant data, demonstrating how training data could be partially recovered through gradient reverse-engineering. Shokri et al. [25] proposed membership inference attacks that allow attackers to determine if specific data was used in training by analyzing model gradient changes.

To enhance privacy protection, DP has become essential in FL [26–28]. Truex et al. [26] introduced the “LDP-Fed” framework, combining Local Differential Privacy (LDP) with FL to ensure data privacy without centralized sensitive data storage, balancing privacy protection and computational efficiency. DP adds noise to model updates to prevent individual data inference from model outputs. El et al. [29] discussed DP’s application in deep learning and FL, focusing on privacy protection technologies. Wei et al. [30] proposed a DP-based FL algorithm, analyzing the trade-off between privacy protection and convergence performance.

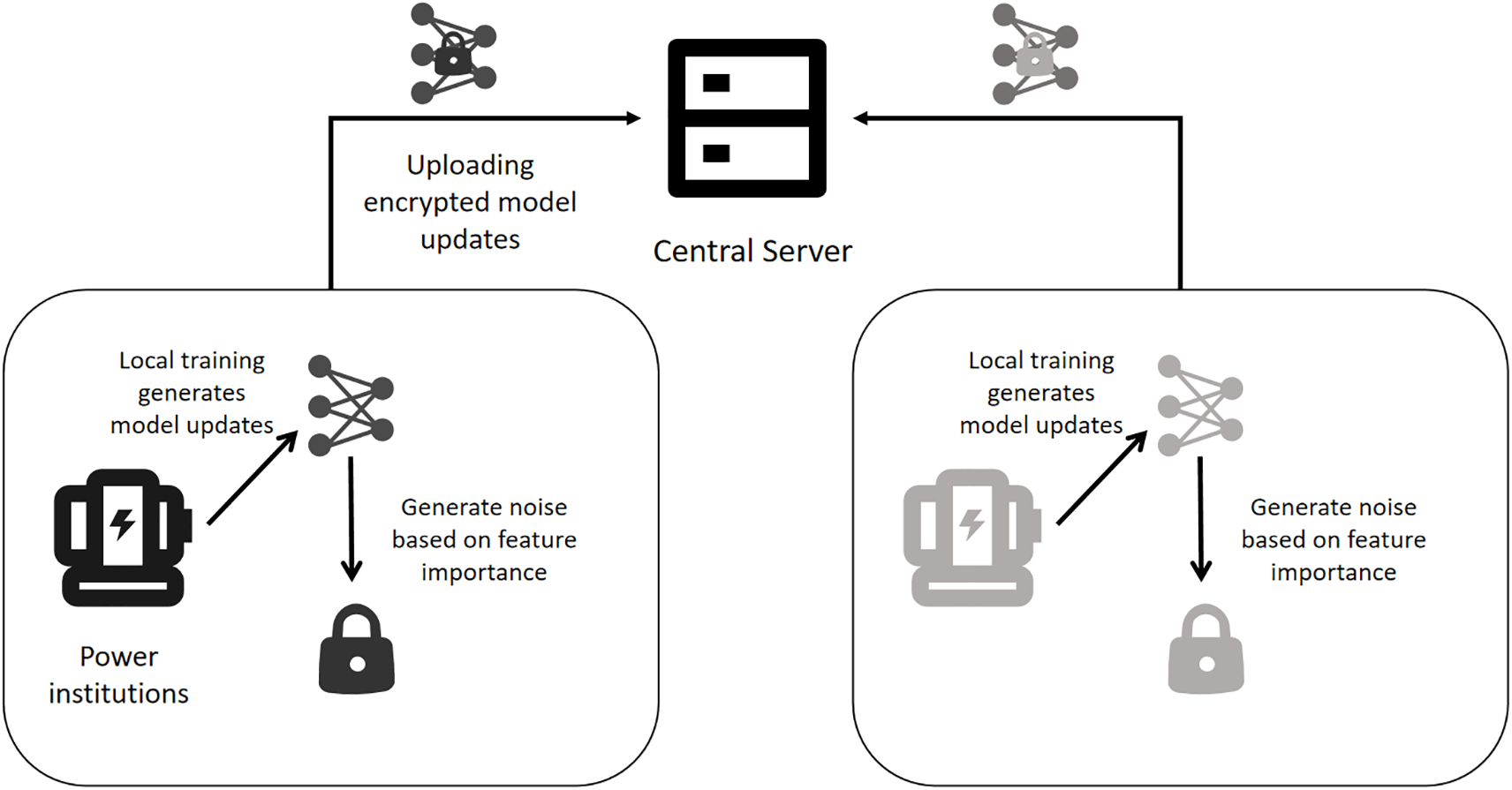

To tackle the trade-off trade-off between model performance and privacy protection in Federated Learning (FL), and the trust issues stemming from the model’s black-box nature, we propose an explainable privacy-preserving FL framework as shown in Fig. 1. This framework dynamically adjusts privacy protection strength based on layer importance and uses SHAP values and model performance for aggregation.

Figure 1: Explainability-driven and privacy-preserving FL framework for power data

The explainability-driven and privacy-preserving FL framework is based a machine learning paradigm that ensures privacy protection. It enables multiple clients (such as institutions and mobile devices) to collaboratively train a global model while keeping data localized, thereby safeguarding data privacy.

The key principle of FL is as follows:

Clients download the global model parameters

where

The server collects the parameter updates from each client

where

FL aims to minimize the weighted sum of the losses from all clients:

The framework consists of participating clients and a central server. The client is responsible for performing local training, calculating the privacy budget allocation strategy, adding noise to the gradient and uploading the noisy gradient to the central server, and the central server is responsible for aggregating the global model with reference to the explainability and model performance of the local model.

The training process of framework includes the following steps:

1. Each participant performs local training based on the global model.

2. Each participant calculates the privacy budget for this round of local training.

3. Each participant calculates the privacy budget of each layer of the model based on the layer importance.

4. Each participant uploads the noisy gradient to the central server.

5. The central server performs aggregation with reference to the model explainability and model performance to generate a global model.

6. The central server distributes the global model to all participants.

First, we introduce the training process of neural networks to guide privacy budget allocation. Neural networks are usually composed of the following components:

Input Layer: Receives raw data (e.g., image pixels, text vectors).

Hidden Layer Computation: Each neuron performs a linear transformation on the input (weight matrix multiplication + bias term), followed by a nonlinear activation function (e.g., ReLU, Sigmoid).

Output Layer: Generates the final prediction (e.g., classification probability, regression value).

In a neural network, forward propagation refers to the process of passing data from the input layer to the output layer to compute the model’s predictions. Through multiple layers of nonlinear transformations, the original input is mapped to the target output space.

Backward propagation refers to the process of computing gradients layer by layer from the output layer to the input layer, based on prediction errors, to update network parameters. The gradients guide the adjustment of network parameters in the direction of minimizing prediction errors.

The backward propagation process includes the following steps:

Loss Calculation: The error between predicted values and true values is quantified using a loss function (e.g., cross-entropy, mean squared error).

Gradient Calculation for Backpropagation:

Firstly, compute the derivative of the loss with respect to the input of the output layer:

Then, using the chain rule, the gradient for each layer is computed (

Next, the gradients of the weights and biases are computed based on

The parameters are updated using optimization algorithms such as gradient descent, where

In the training process of FL combined with DP, the traditional privacy budget allocation method usually adopts a fixed allocation or uniform allocation strategy, that is, the total privacy budget

Our method is based on the following ideas. When the gradient descent direction is not stable enough, appropriately increase the privacy budget to reduce the impact of noise and make the gradient update more reliable. After the gradient direction tends to be stable, reduce the privacy budget consumption to ensure that the budget can support more rounds of training.

When the client performs local training for round t, taking Laplace noise as an example, the true gradient

Use the Armijo condition to check whether the updated objective function value meets the “sufficient decrease” requirement [31]. Let the objective function be

where

Otherwise, it is considered that the current noise is too large, causing the update direction to “deviate” from the ideal descent direction, and the privacy budget needs to be adjusted.

The privacy budget adjustment formula is:

where

Check again whether the noisy gradient meets the Armijo condition. If it still does not meet the condition, continue to increase the privacy budget and repeat the above steps until an update direction that meets the descent condition is found or the preset budget limit is reached.

In order to make full use of the results of the two calculations, the GRADAVG algorithm can be used to fuse the gradients:

where

In a deep neural network (DNN), different layers contribute differently to the final model decision. Some layers are critical to the core reasoning of the model, while others have relatively little impact. If all layers apply the same privacy budget allocation strategy, it may lead to unnecessary information loss, thereby reducing the accuracy of the model. Therefore, we introduce the concept of layer importance as a reference for privacy budget allocation. Layer importance is one perspective of model explainability.

For high-importance layers, a larger privacy budget is allocated to reduce the impact of noise and ensure that the information of these key layers is retained to the greatest extent;

For low-importance layers, a smaller privacy budget is allocated and more noise is applied to weaken its impact on the final model output while improving the privacy protection strength.

Based on this inter-layer privacy budget allocation strategy, the learning effect of the model can be improved as much as possible while ensuring privacy.

Next, we use layer importance to allocate privacy budgets between layers.

When calculating layer importance, first, each client receives the global model sent by the central server and uses local data for local training. The goal of this stage is to make the model initially adapt to the local data distribution and lay the foundation for the subsequent layer importance calculation.

After the local training is completed, the client uses the layer importance evaluation data to further evaluate the importance of each layer of the model. Taking the Sigmoid activation function as an example, the value range of the Sigmoid activation function is between 0 and 1. When the input of the Sigmoid activation function approaches negative infinity, the value of the neuron after the activation function tends to 0, and the neuron close to 0 contributes little to the output of the subsequent layer and the final result. The calculation formula of layer importance is as follows:

For the

After completing the calculation of layer importance, we refer to the layer importance to allocate privacy budgets to each layer, and allocate larger privacy budgets to layers with large importance values, thereby adding less noise to them. For layers with small importance values, smaller privacy budgets are allocated, and more noise is added to them.

The privacy budget allocation of each layer follows the following formula:

In the formula,

In combining DP with FL, gradient clipping is a key operation. Its main purpose is to control the norm of the gradient uploaded by each client, thereby limiting the sensitivity and ensuring that the added noise is sufficient to protect privacy while preventing abnormal gradients from affecting model training. Gradient clipping follows the following formula:

C represents the clipping value, and the sensitivity is usually set to:

In some existing works, the clipping value

We calculated the statistical information about the gradient of each layer obtained by the client during local training, including the mean, variance, and maximum value. After experimental screening, we selected the average gradient as the gradient clipping value.

Assuming that the mean value of the gradient of the

By adaptively clipping different layers, not only more valid values in the gradient are retained, but also some gradients are prevented from adding too much noise, thereby improving the accuracy of the model.

After completing the gradient clipping, the sensitivity of the gradient of the

Considering that the added noise will cause the distortion of gradients, we designed an aggregation strategy based on model explainability and model performance when aggregating models at the central server. Specifically, an evaluation data set is maintained at the central server. We presume customer data is (approximately) independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), and that the evaluation dataset’s distribution resembles the client dataset’s. After receiving the gradient from the client, the central server will calculate the local model for each client as the initial set of models to be aggregated based on the global model of the previous round of aggregation.

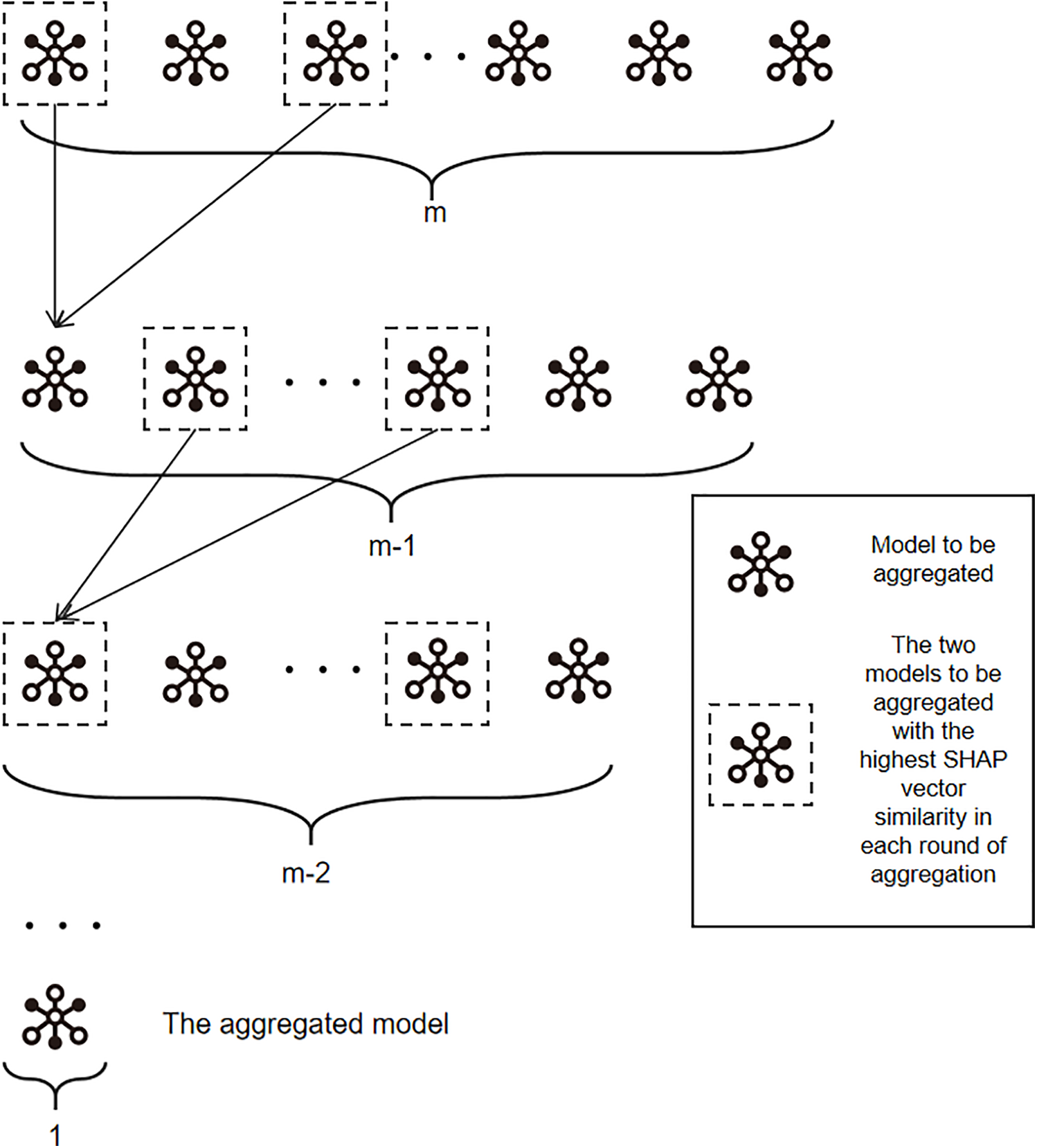

The model aggregation process is shown in Fig. 2. In each round of aggregation, the two models with the highest SHAP value vector similarity in the models to be aggregated are selected to aggregate and generate a temporary model to be added to the set of models to be aggregated. The above iterative process is repeated until the final model is obtained.

Figure 2: Model aggregation method based on SHAP vector and accuracy

Based on the evaluation data set, the central server calculates the SHAP value vector and a performance evaluation index (taking accuracy as an example) for the temporary models of all clients.

SHAP value is a model explainability method based on Shapley value in game theory. It reveals the impact of each feature by quantifying its marginal contribution to the model prediction. The core idea is to decompose the model’s prediction value into the sum of all feature contributions. The specific calculation formula is:

Among them,

All temporary models are regarded as a set, and the two models with the highest SHAP vector cosine similarity are selected for aggregation each time. When aggregating, in addition to considering the explainability of the model, the performance of the model should also be considered as a factor when aggregating.

Assuming that the accuracy of the temporary model of client

The aggregated model

The overall framework is shown in Algorithm 1.

Next, we theoretically prove the privacy protection ability of the proposed method.

For client

The formula indicates that the

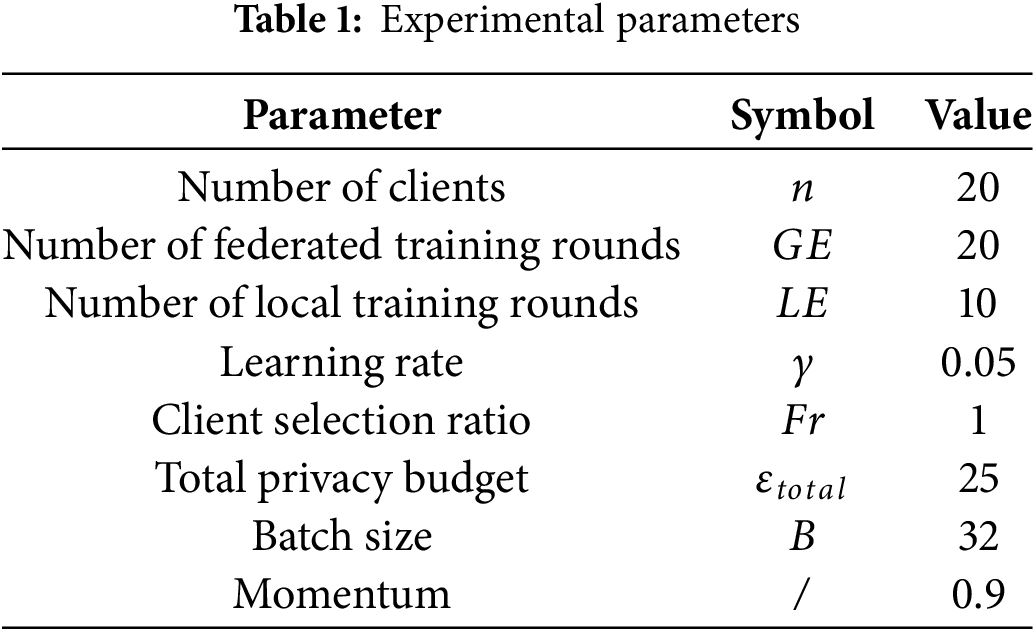

The method proposed in this paper aims to enhance the privacy of FL based on power data in the electricity sector, while ensuring the accuracy of the released models. In the experimental section, we use the GEFC2012 dataset. The GEFC2012 dataset contains electricity consumption data from 20 power stations, spanning from January 2004 to July 2008, covering a total of 1650 days. In this experiment, the prediction target is the power load of each power station. Each power station in the GEFC2012 dataset is treated as a separate client. The simulation parameters used in the experiment are summarized in the Table 1 below.

In the experiment, we use Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) as the base model and select the classic FL algorithm FedAvg, as well as Differentially Private FL (DP-FL) [32], as comparison algorithms. When adding noise, we use Laplace noise

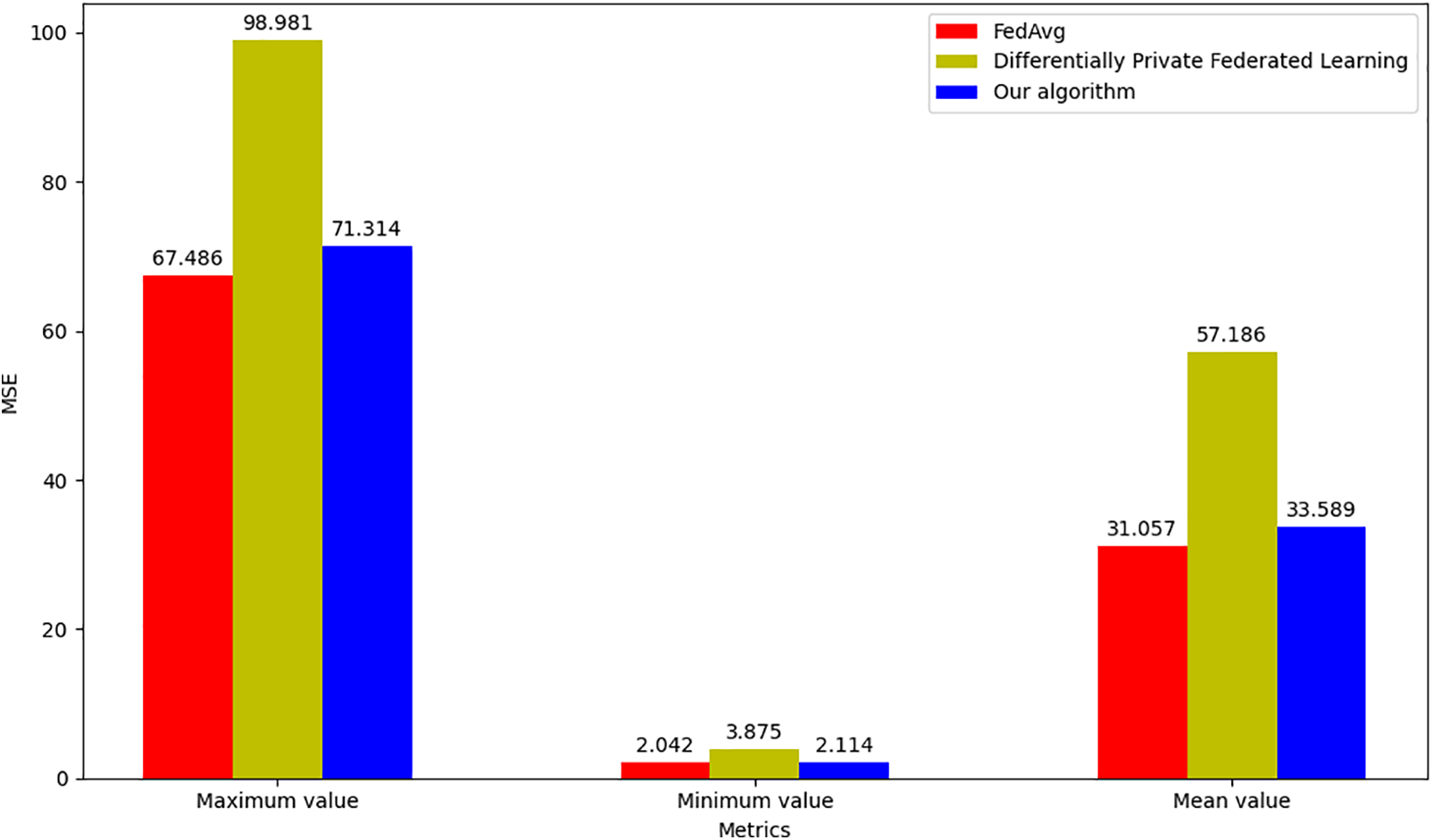

We first compare the mean squared error (MSE) of the global models trained under the three methods as an evaluation metric for training effectiveness. The MSE measures the fluctuation degree of the data; a smaller MSE implies a better alignment between the predictive model and the experimental data. We ensure that the parameter settings for all three methods are consistent, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Comparison of maximum, minimum, and average MSE under different algorithms

Analysis of the global model MSE post-training reveals that, compared to FedAvg, our algorithm shows minimal differences in maximum, minimum, and average MSE values. This indicates our algorithm effectively reduces noise impact on training, preserving model performance while maintaining power data privacy. Conversely, the DP-FL method demonstrates significantly inferior performance across these MSE metrics, with substantial MSE variance, highlighting the considerable negative effect of its added noise on model performance.

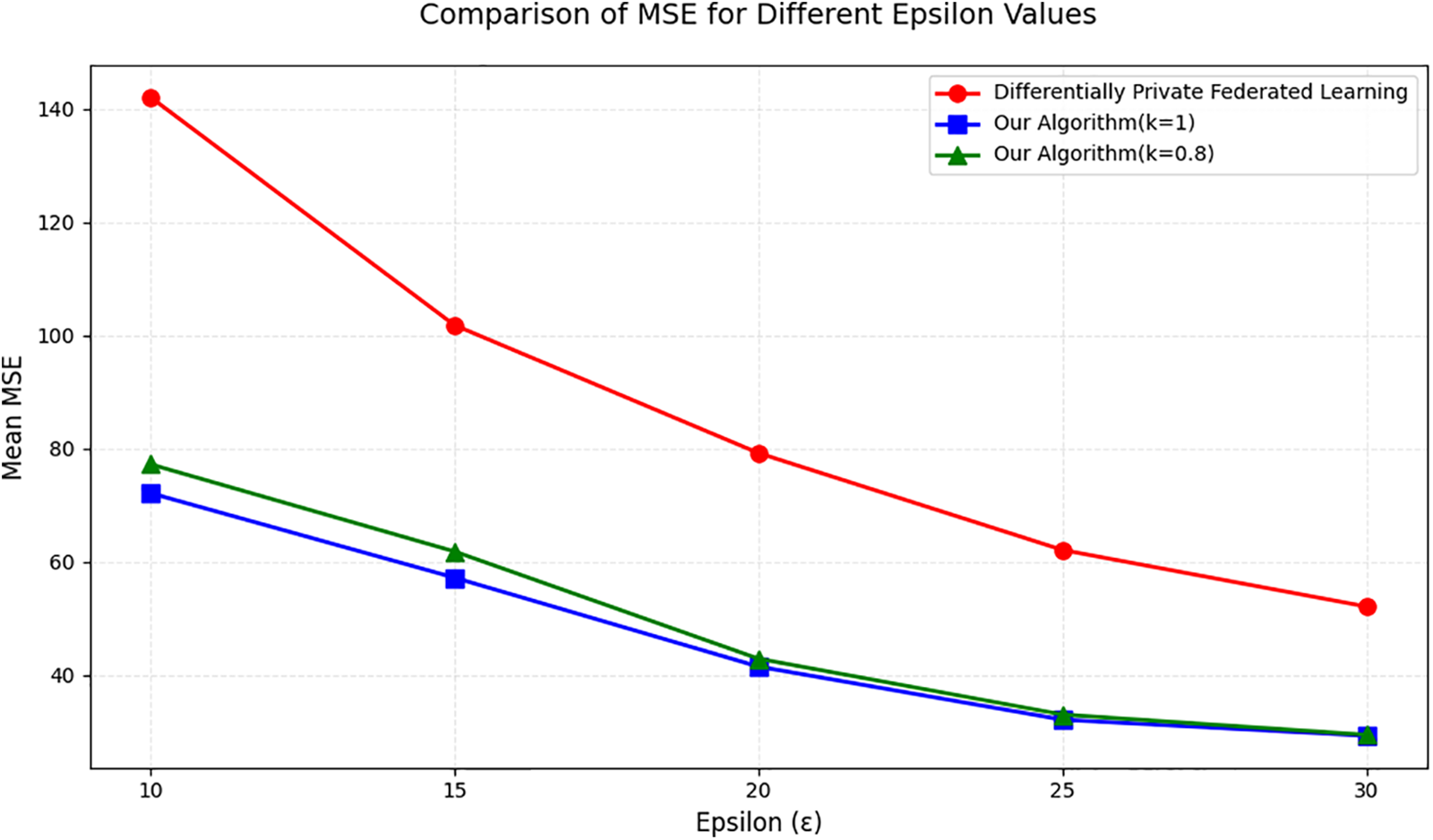

In the next step, we compare the performance of DP-FL and our algorithm under varying total privacy budgets. Considering that GEFC2012 is a heterogeneous dataset, for our method, we set two control groups with client selection ratio of 1 and client selection ratio of 0.8 to observe the performance of our method under different client selection ratios. We set the total privacy budget to 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30, respectively, and observe the average MSE performance of the global model under both algorithms.

As shown in Fig. 4, our method significantly outperforms DP-FL in mean MSE, with this advantage growing more pronounced as the total privacy budget decreases. This confirms our method’s effectiveness in minimizing model performance loss while ensuring FL privacy. Through dynamic privacy budget allocation and an aggregation strategy based on explainability and model performance, we achieve an effective balance between model utility and privacy protection. In addition, adjusting the client selection ratio has no significant effect on the performance after convergence, but our method shows faster convergence when the client selection ratio is higher.

Figure 4: Comparison of average MSE under different overall privacy budgets

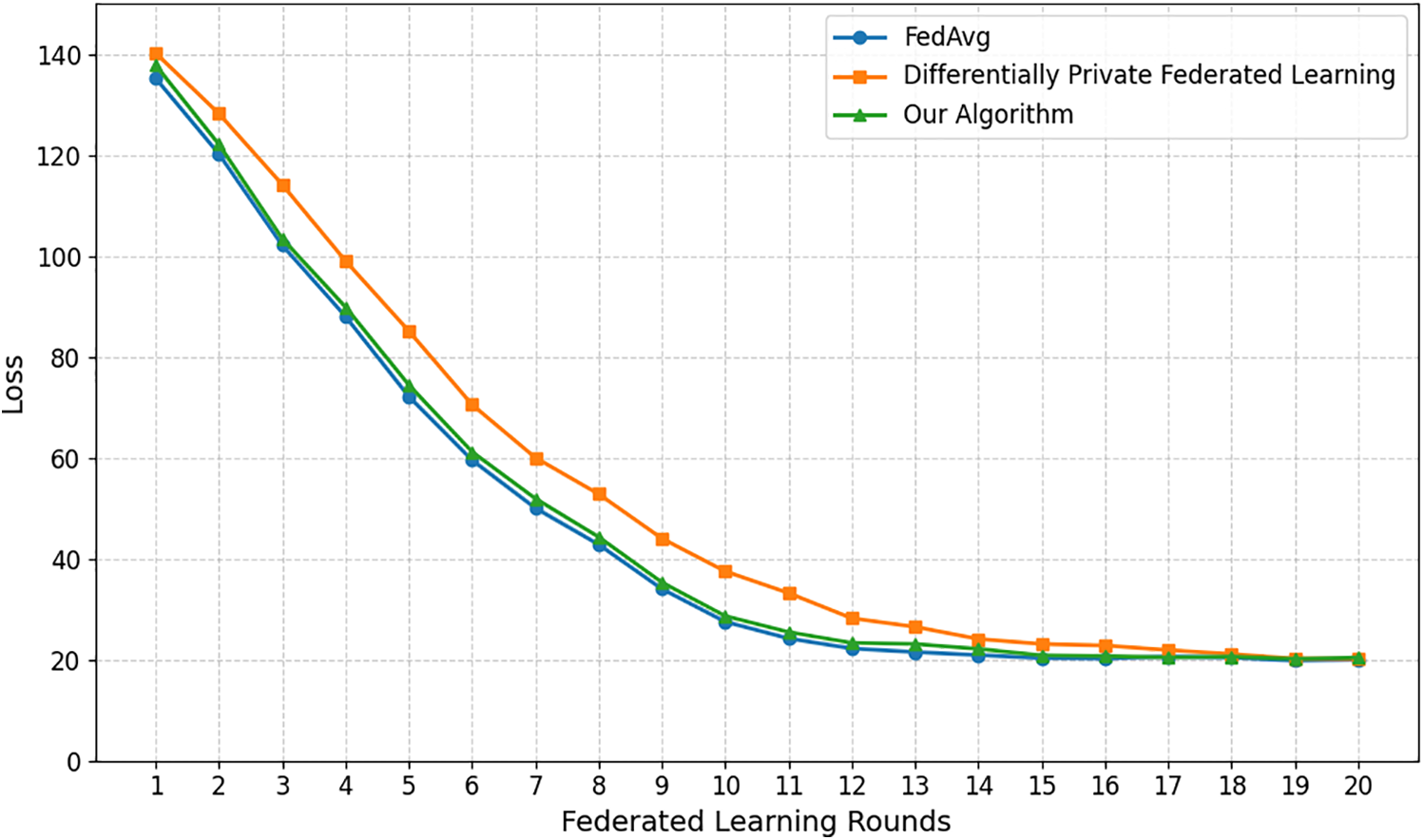

Then, we set the client selection ratio to 1, ensuring all 20 clients participate in the FL process. We then record loss values for 20 global training rounds under three different methods and compare model performance and training efficiency across these methods.

Fig. 5 shows the loss changes of three FL algorithms—FedAvg, DP-FL, and our algorithm—over different training epochs. As training epochs increase, the loss of all three methods drops rapidly at first, then slows down, and finally stabilizes at similar levels, showing comparable global model performance. Although DP-FL and our algorithm add noise during training, its impact fades in later stages, allowing successful model convergence. DP-FL has the slowest loss reduction due to noise in model updates that hinders training. Its initial loss is also higher than the other two methods because of the greater impact of early noise. FedAvg shows the fastest convergence throughout training, indicating it can quickly reduce model error for better training results. Our algorithm’s loss reduction is similar to FedAvg’s, and its training efficiency is much higher than DP-FL’s. This means our algorithm adds less noise to updates of more important layers, keeping these updates authentic while effectively balancing privacy protection and training efficiency.

Figure 5: Loss reduction of different algorithms

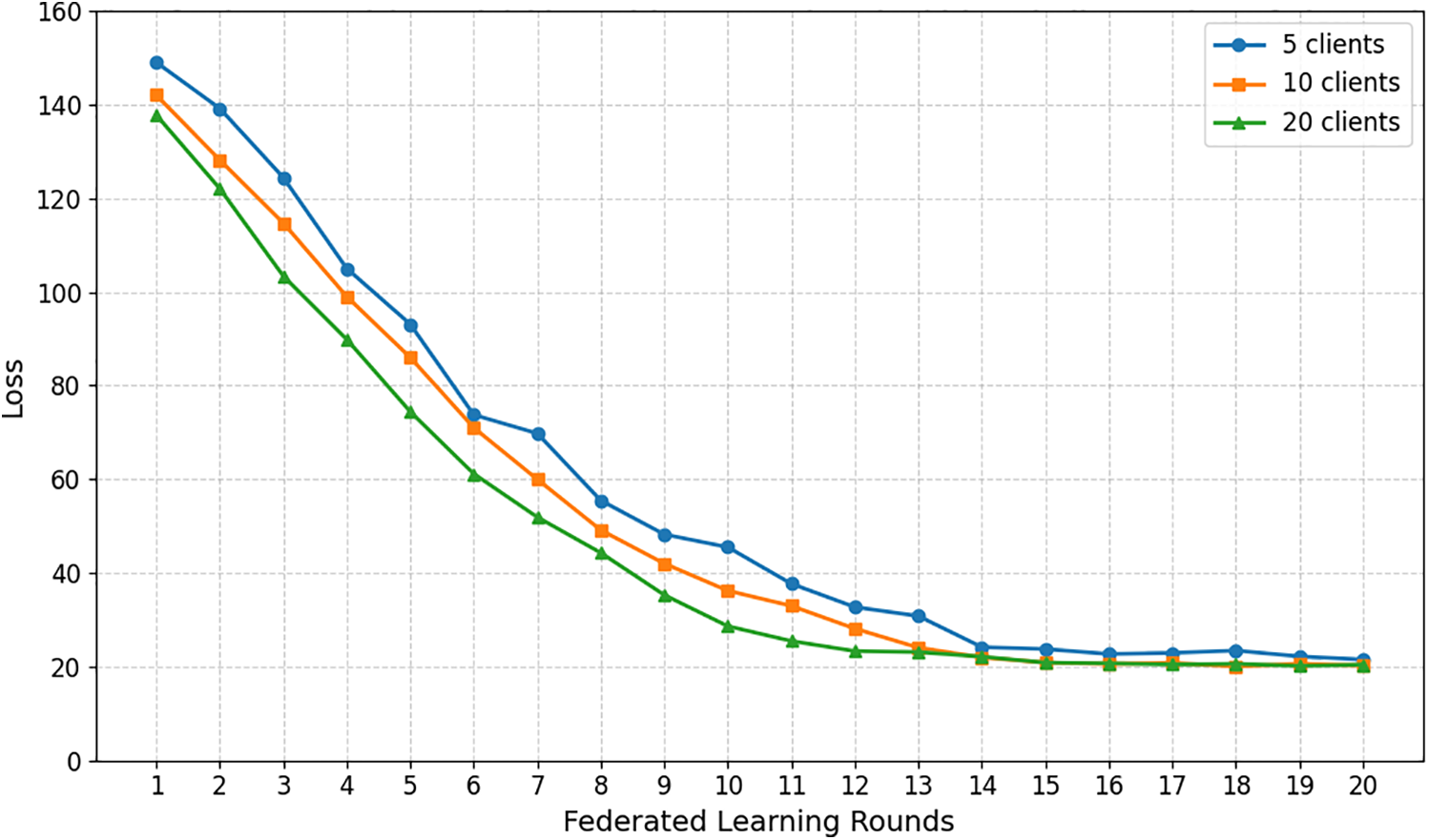

Next, we adjust the client selection ratio to change the number of clients in federated training. By comparing loss values over 20 global training rounds with different client numbers, we assess the impact of client count variations on model performance and training efficiency.

Fig. 6 presents the loss variations of three client configurations across different training epochs. The five-client setup shows the poorest training performance, with consistently higher loss and more noticeable curve fluctuations compared to the ten- and twenty-client setups. The loss reduction trends for ten and twenty clients are similar, with the latter slightly outperforming the former. At convergence, the five-client case has a slightly higher loss than the ten- and twenty-client cases.

Figure 6: Loss reduction with different number of clients

This can be explained by the small number of clients in the five-client setup, which introduces training uncertainty due to noise in each client’s model update. Fewer clients may also cause biased global model updates toward specific clients, affecting the overall training. As the number of clients increases, the FL process becomes more stable. In our algorithm, aggregating reference explainability with model performance makes the FL process approach a noise-free scenario.

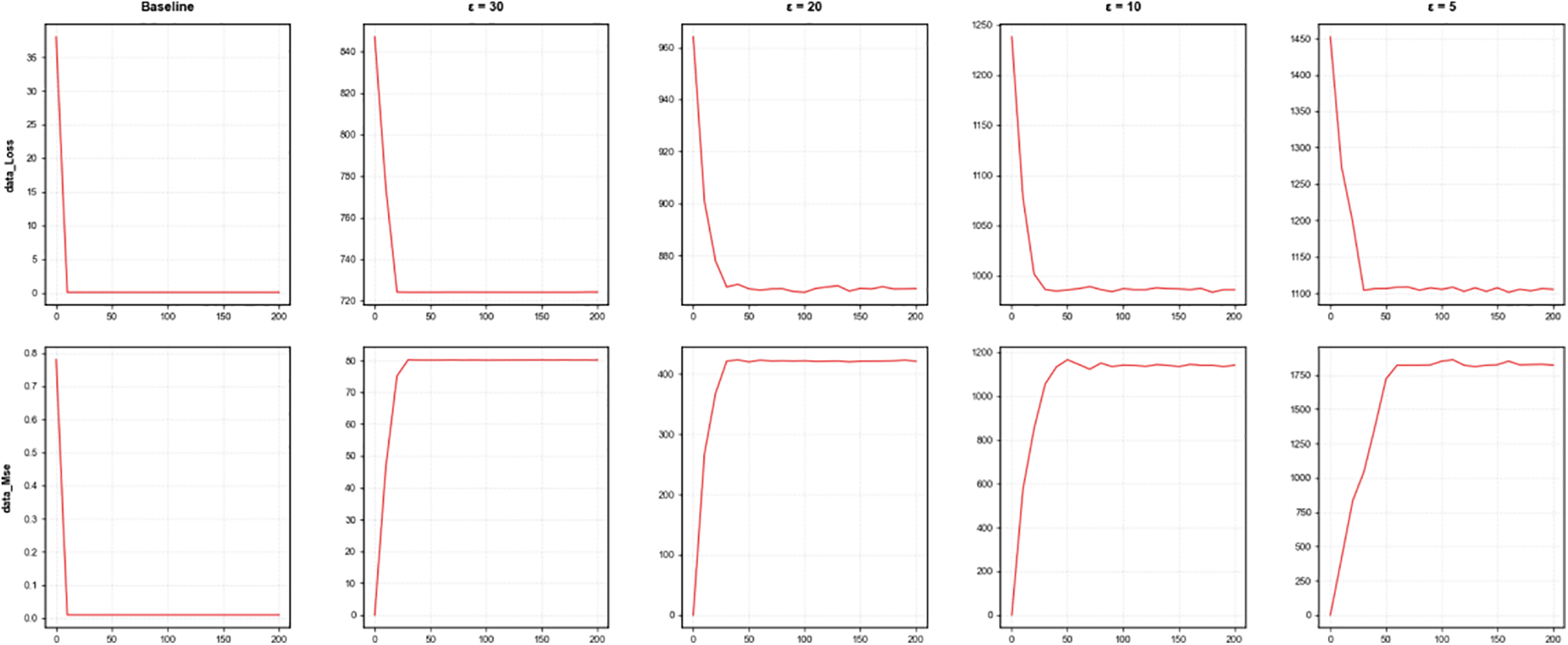

Next, we compare the ability of our proposed method to defend against gradient leakage attacks when using different privacy budgets. The indicators we refer to include the sum of squared gradient differences between the fake data restored by the attacker and the real data (data Loss) and the mean squared error (data Mse) between the fake data and the real data. Data Loss and data Mse quantify the ability to defend against gradient leakage attacks. When data Loss and data Mse are larger, it means that it is difficult for the attacker to recover the accurate original data through gradient leakage attacks. We use FedAvg without privacy protection as the baseline model. Set the batch size of the client local model update to 1.

By observing Fig. 7, we can see that when using the non-privacy fedavg baseline method, data loss and data mse converge quickly and decrease to a level close to 0, which means that the attacker can restore the original data with high quality. When using the method proposed in this paper, data loss and data mse converge to a higher level, which means that the data restored by the attacker is inaccurate, verifying that our proposed method can effectively resist gradient leakage attacks. As the privacy budget decreases, data loss and data mse converge to a higher level, and the privacy protection ability of the method is enhanced.

Figure 7: Data loss and MSE under different privacy budgets

This paper proposes an explainability-driven and privacy-preserving FL framework to address the trade-off between data privacy protection and model performance in practical power industry applications. The framework carefully considers the layer importance in power data and dynamically adjusts the noise addition process by combining DP techniques. This approach ensures strong privacy protection while improving model performance. At the same time, the model aggregation is performed based on the explainability and performance of the reference model, which reduces the damage of the aggregation process by low-quality models. Unlike traditional static privacy protection methods, this framework uses explainability analysis tools to assist FL.

Experiments on the power load forecasting task show that the proposed framework significantly improves prediction accuracy and training efficiency while maintaining data privacy. Compared with traditional methods, the proposed method better balances model utility and privacy protection, showing considerable advantages in privacy protection. This study provides new insights into privacy protection and intelligent applications in the power industry, and provides theoretical and practical guidance.

Acknowledgement: The authors declare that there are no individuals or organizations to acknowledge for their contributions to this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Zekun Liu and Junwei Ma conceived the study and developed the framework. Xin Gong designed the privacy budget allocation strategy. Xiu Liu implemented the weighted aggregation strategy. Long An performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Bingbing Liu contributed to resource provision and supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Junwei Ma, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Miao Y, Yan X, Li X, Xu S, Liu X, Li H, et al. RFed: robustness-enhanced privacy-preserving federated learning against poisoning attack. IEEE Trans Inform Forensic Secur. 2024;19:5814–27. doi:10.1109/tifs.2024.3402113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Alamer A, Basudan S. A privacy-preserving federated learning with a feature of detecting forged and duplicated gradient model in autonomous vehicle. IEEE Access. 2025;13:38484–501. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3545786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Formery Y, Mendiboure L, Villain J, Deniau V, Gransart C. A framework to design efficent blockchain-based decentralized federated learning architectures. IEEE Open J Comput Soc. 2024;5(37):705–23. doi:10.1109/ojcs.2024.3488512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gong Z, Shen L, Zhang Y, Zhang LY, Wang J, Bai G, et al. AgrAmplifier: defending federated learning against poisoning attacks through local update amplification. IEEE Trans Inform Forensic Secur. 2024;19:1241–50. doi:10.1109/tifs.2023.3333555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xu Z, Yu Z, Zhang H, Chen J, Gu J, Lukasiewicz T, et al. PhaCIA-TCNs: short-term load forecasting using temporal convolutional networks with parallel hybrid activated convolution and input attention. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2024;11(1):427–38. doi:10.1109/tnse.2023.3300744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li S, Ngai ECH, Voigt T. An experimental study of Byzantine-robust aggregation schemes in federated learning. IEEE Trans Big Data. 2024;10(6):975–88. doi:10.1109/TBDATA.2023.3237397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li X, Qu Z, Zhao S, Tang B, Lu Z, Liu Y. LoMar: a local defense against poisoning attack on federated learning. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2023;20(1):437–50. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2021.3135422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Geng G, Cai T, Yang Z. Better safe than sorry: constructing Byzantine-robust federated learning with synthesized trust. Electronics. 2023;12(13):2926. doi:10.3390/electronics12132926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Xing Z, Zhang Z, Zhang ZA, Liu J, Zhu L, Russello G. No vandalism: privacy-preserving and byzantine-robust federated learning. In: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS); 2024 Oct 14–18; Salt Lake City, USA. [Google Scholar]

10. Yan X, Miao Y, Li X, Choo KR, Meng X, Deng RH. Privacy-preserving asynchronous federated learning framework in distributed IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(15):13281–91. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3262546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen Y, Yan L, Ai D. An robust secure blockchain-based hierarchical asynchronous federated learning scheme for Internet of Things. IEEE Access. 2024;12:165280–97. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3493112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Vyas A, Lin PC, Hwang RH, Tripathi M. Privacy-preserving federated learning for intrusion detection in IoT environments: a survey. IEEE Access. 2024;12:127018–50. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3454211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Alebouyeh Z, Bidgoly AJ. Benchmarking robustness and privacy-preserving methods in federated learning. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;155(1):18–38. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas AB. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. arXiv:1602.05629. 2016. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1602.05629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Taik A, Cherkaoui S. Electrical load forecasting using edge computing and federated learning. In: Proceedings of the ICC 2020–2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2020 Jun 7–11; Dublin, Ireland. doi:10.1109/icc40277.2020.9148937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Briggs C, Fan Z, Andras P. Federated learning for short-term residential load forecasting. IEEE Open Access J Power Energy. 2022;9:573–83. doi:10.1109/oajpe.2022.3206220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Su Z, Wang Y, Luan TH, Zhang N, Li F, Chen T, et al. Secure and efficient federated learning for smart grid with edge-cloud collaboration. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2022;18(2):1333–44. doi:10.1109/tii.2021.3095506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu H, Zhang X, Shen X, Sun H. A federated learning framework for smart grids: securing power traces in collaborative learning. arXiv:2103.11870. 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2103.11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Cheng X, Li C, Liu X. A review of federated learning in energy systems. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia (I&CPS Asia); 2022 Jul 8–11; Shanghai, China. doi:10.1109/ICPSAsia55496.2022.9949863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zheng R, Sumper A, Aragüés-Peñalba M, Galceran-Arellano S. Advancing power system services with privacy-preserving federated learning techniques: a review. IEEE Access. 2024;12:76753–80. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3407121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Husnoo MA, Anwar A, Reda HT, Hosseinzadeh N, Islam SN, Mahmood AN, et al. FedDiSC: a computation-efficient federated learning framework for power systems disturbance and cyber attack discrimination. Energy AI. 2023;14(2):100271. doi:10.1016/j.egyai.2023.100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wen M, Xie R, Lu K, Wang L, Zhang K. FedDetect: a novel privacy-preserving federated learning framework for energy theft detection in smart grid. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(8):6069–80. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3110784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Badr MM, Mahmoud MMEA, Fang Y, Abdulaal M, Aljohani AJ, Alasmary W, et al. Privacy-preserving and communication-efficient energy prediction scheme based on federated learning for smart grids. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(9):7719–36. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3230586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhu L, Liu Z, Han S. Deep leakage from gradients. In: Wallach H, Larochelle H, Beygelzimer A, d'Alché-Buc F, Fox E, Garnett R, editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32. Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019); 2019 Dec 8–14. Vancouver, BC, Canada; Houston, TX, USA: NeurIPS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

25. Shokri R, Stronati M, Song C, Shmatikov V. Membership inference attacks against machine learning models. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2017 May 22–26; San Jose, CA, USA. doi:10.1109/SP.2017.41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Truex S, Liu L, Chow KH, Gursoy ME, Wei W. LDP-Fed: federated learning with local differential privacye. In: Proceedings of the Third ACM International Workshop on Edge Systems, Analytics and Networking; 2020 Apr 27; Heraklion, Greece. doi:10.1145/3378679.3394533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Triastcyn A, Faltings B. Federated learning with Bayesian differential privacy. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2019 Dec 9–12; Los Angeles, CA, USA. doi:10.1109/bigdata47090.2019.9005465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wu X, Zhang Y, Shi M, Li P, Li R, Xiong NN. An adaptive federated learning scheme with differential privacy preserving. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2022;127(8):362–72. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.09.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. El Ouadrhiri A, Abdelhadi A. Differential privacy for deep and federated learning: a survey. IEEE Access. 2022;10(2):22359–80. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3151670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wei K, Li J, Ding M, Ma C, Yang HH, Farokhi F, et al. Federated learning with differential privacy: algorithms and performance analysis. IEEE Trans Inform Forensic Secur. 2020;15:3454–69. doi:10.1109/tifs.2020.2988575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Armijo L. Minimization of functions having Lipschitz continuous first partial derivatives. Pacific J Math. 1966;16(1):1–3. doi:10.2140/pjm.1966.16.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Geyer RC, Klein T, Nabi M. Differentially private federated learning: a client level perspective. arXiv:1712.07557. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1712.07557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools