Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evaluating Method of Lower Limb Coordination Based on Spatial-Temporal Dependency Networks

1 Sport Science Research Institute, Nanjing Sport Institute, Nanjing, 210014, China

2 School of Computer Science, School of Cyber Science and Engineering, Engineering Research Center of Digital Forensics, Ministry of Education, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

* Corresponding Author: Yongjun Ren. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1959-1980. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066266

Received 03 April 2025; Accepted 06 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

As an essential tool for quantitative analysis of lower limb coordination, optical motion capture systems with marker-based encoding still suffer from inefficiency, high costs, spatial constraints, and the requirement for multiple markers. While 3D pose estimation algorithms combined with ordinary cameras offer an alternative, their accuracy often deteriorates under significant body occlusion. To address the challenge of insufficient 3D pose estimation precision in occluded scenarios—which hinders the quantitative analysis of athletes’ lower-limb coordination—this paper proposes a multimodal training framework integrating spatiotemporal dependency networks with text-semantic guidance. Compared to traditional optical motion capture systems, this work achieves low-cost, high-precision motion parameter acquisition through the following innovations: (1) spatiotemporal dependency attention module is designed to establish dynamic spatiotemporal correlation graphs via cross-frame joint semantic matching, effectively resolving the feature fragmentation issue in existing methods. (2) noise-suppressed multi-scale temporal module is proposed, leveraging KL divergence-based information gain analysis for progressive feature filtering in long-range dependencies, reducing errors by 1.91 mm compared to conventional temporal convolutions. (3) text-pose contrastive learning paradigm is introduced for the first time, where BERT-generated action descriptions align semantic-geometric features via the BERT encoder, significantly enhancing robustness under severe occlusion (50% joint invisibility). On the Human3.6M dataset, the proposed method achieves an MPJPE of 56.21 mm under Protocol 1, outperforming the state-of-the-art baseline MHFormer by 3.3%. Extensive ablation studies on Human3.6M demonstrate the individual contributions of the core modules: the spatiotemporal dependency module and noise-suppressed multi-scale temporal module reduce MPJPE by 0.30 and 0.34 mm, respectively, while the multimodal training strategy further decreases MPJPE by 0.6 mm through text-skeleton contrastive learning. Comparative experiments involving 16 athletes show that the sagittal plane coupling angle measurements of hip-ankle joints differ by less than 1.2° from those obtained via traditional optical systems (two one-sided t-tests, p < 0.05), validating real-world reliability. This study provides an AI-powered analytical solution for competitive sports training, serving as a viable alternative to specialized equipment.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of deep learning technology, it has become possible to use artificial intelligence as a replacement for traditional human motion parameter acquisition [1]. In many sports, excellent lower-limb coordination is crucial, such as in soccer, basketball, fencing, and other athletic disciplines. It not only significantly impacts the fluidity and precision of movements but also influences athletes’ reaction speed and technical stability, thereby becoming a critical factor in achieving success in competitive sports. During training, if athletes’ lower-limb coordination can be analyzed based on data, training efficiency can be substantially enhanced [2]. Moreover, data-driven technical guidance can effectively reduce the risk of injuries caused by improper movements. In competitive settings, analyzing lower-limb coordination enables coaches to make real-time tactical adjustments, extending the advantages observed in training scenarios [3]. Thus, assessing athletes’ lower-limb coordination is essential for optimizing sports performance and mitigating injury risks.

Quantitative analysis of lower limb coordination is one of the key steps. It can accurately calculate key indicators such as speed and joint angles and analyze lower limb coordination, thus contributing to a safer training and competition environment and improving training efficiency [4]. There are currently several methods for quantifying coordination. Continuous relative phase (CRP) [5] pioneered the quantification of dynamic coordination by calculating the phase difference between two joint angles and angular velocities in the phase plane. For the first time, it achieved a continuous description of the coordination mode within the motion cycle. However, this method relies on a strict assumption of periodic motion and is sensitive to changes in motion speed. It is easy to produce phase drift errors in non-periodic motion. Cross-correlation analysis (CCA) [6] improves on the timing limitations of CRP. By calculating the correlation coefficient of two joint angle sequences and their maximum correlation lag time, it effectively captures the timing coupling relationship between joints. Vector coding technology (VC) [7] breaks through the limitations of the first two. By constructing a polar coordinate mapping of joint angle pairs, it captures the instantaneous coordination mode switching through the angle change vectors of adjacent frames. Recent studies have shown that vector coding techniques offer significant advantages over other methods. This technique quantifies motor coordination patterns at each time point, provides a more comprehensive analysis, and produces more interpretable results.

Traditional vector coding-based lower limb coordination analysis methods mainly rely on optical motion capture systems to collect kinematic parameters. This method is not suitable for analyzing the lower limb coordination of athletes during training and competition. Optical motion capture devices require the human body to wear a large number of markers, which may cause discomfort to athletes and affect their performance. In addition, the high cost of optical motion capture systems limits their widespread adoption in sports competitions and training programs. With the rapid development of deep learning technology, it has become possible to use artificial intelligence to replace traditional human kinematic parameter collection methods for lower limb coordination quantification [8]. Pose estimation algorithms, which use ordinary cameras as data collection devices, effectively address the limitations of optical motion capture systems. By applying pose estimation algorithms to video data captured by ordinary cameras, the same kinematic parameters can be obtained without additional equipment. However, pose estimation algorithms often have difficulty in providing accurate data under occlusion conditions, which limits their practical application. In order to improve the performance of 3D pose estimation in predicting occluded poses, current methods use independent modules to process spatial and temporal information, respectively. However, this approach ignores the intrinsic relationship between spatiotemporal data. In addition, competitive sports video data has a high amount of information in the local time window. Due to motion blur or instantaneous occlusion, the aggregation of information in the long-range time series often introduces a lot of noise, thereby reducing the accuracy of the model [9]. The key point is that 3D pose estimation is a regression task, which cannot capture high-level contextual information related to human motion poses. This semantic information can help the model understand the intention of the current action, the correlation between body parts and physical constraints, and is crucial to improving the performance of the model in predicting occluded poses.

In order to improve the performance of pose estimation under occlusion and overcome the limitations of traditional data collection methods, a pose estimation algorithm combined with a multimodal training strategy is proposed. This method combines text descriptions of body parts to assist model training, and introduces various new modules to effectively deal with occlusion problems in pose estimation. These modules use multimodal information to improve the robustness of the algorithm in complex scenes. This method can accurately capture human kinematic parameters in natural environments and provide strong support for the quantification of athlete coordination. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

• In the pose estimation algorithm, we proposed a spatiotemporal dependency module, which aims to capture the spatiotemporal relationship in a unified framework. This module adopts an attention mechanism to select semantically related nodes, thereby effectively capturing the spatiotemporal dependency. The noise compression multi-scale time series module we proposed innovatively introduces information gain analysis and channel compression mechanism. In the process of long-range time series feature fusion, this module dynamically evaluates the information value of different time windows through KL divergence, suppresses redundant noise, and retains key motion patterns.

• We propose an innovative multimodal training strategy that integrates a spatiotemporal dependency network with a BERT pre-trained language model. This method can effectively solve the problems of semantic association loss caused by the separation of spatial-temporal processing modules in occlusion scenarios, noise interference caused by long-range temporal information aggregation, and insufficient action semantic expression capabilities inherent in the regression task paradigm. It not only significantly improves the accuracy of pose estimation under occlusion, but also enhances the generalization ability and robustness of the model.

• We conducted comparative experiments and ablation studies on the Human3.6M dataset to verify the effectiveness of the proposed module. Experimental results show that the algorithm has good performance under severe occlusion conditions. We recruited several athletes and conducted a comprehensive comparison between the optical motion capture system and our AI-based approach in terms of data acquisition accuracy. The results show that the AI-based solution cannot only accurately capture the lower limb motion parameters, but also effectively address the limitations of the optical motion capture system.

2.1 Quantitative Analysis Methods for Lower Limb Coordination

Motor coordination refers to the ability of the human body to control and coordinate limb movements through the regulation of the nervous, muscular and joint systems while integrating multiple degrees of freedom. Motor coordination has a wide range of applications in medical rehabilitation, sports training, injury prevention and other fields [10]. In order to evaluate motor coordination in more detail, researchers and sports experts have developed a series of quantitative methods. Currently, vector coding technology has become a standard analysis tool in the field of sports science due to its pattern interpretability and computational robustness.

Based on vector coding technology, Cen et al. [11] proposed the dynamic coupling index (DCI) and developed a multi-joint dynamic coupling analysis framework. In recent years, Needham et al. [12] improved the coordination pattern classification standard and achieved a more refined gait cycle division. Vector coding can not only capture the movement coordination patterns between related segments in the whole movement process, but also identify the dominant segments driving the coordination process. This helps to classify the coordination patterns in more detail. Therefore, in this study, we will conduct a quantitative analysis of the lower limb coordination of athletes based on vector coding technology.

2.2 3D Pose Estimation Based on Graph Convolutional Networks

In recent years, significant research progress has been made in 2D pose estimation algorithms. However, compared with 2D pose estimation, 3D pose estimation can overcome the depth ambiguity problem and provide 3D spatial coordinates of joint points, which is of decisive significance for sports biomechanics analysis [13]. In particular, when quantifying the coordination of lower limbs, the accurate calculation of parameters such as 3D joint angles and motion trajectory length requires complete spatial information support [4]. By introducing temporal dimension modeling, 3D methods can also effectively solve the problem of coordinate jumps caused by self-occlusion, and show stronger robustness in multi-angle video analysis scenarios of competitive sports [14]. 3D human pose estimation methods based on graph convolutional networks (GCNs) have made significant progress in occlusion processing. The dynamic graph convolutional network (DGCN) proposed by Qiu et al. [15] realizes end-to-end spatiotemporal modeling of 2D sequences to 3D poses by dynamically adjusting the joint connection weights. On this basis, Cai et al. [16] constructed a multi-scale spatiotemporal graph and significantly improved the estimation accuracy in complex occlusion scenes through hierarchical feature fusion. In response to the challenge of multi-person pose estimation, Cheng et al. [17] innovatively proposed a dual-channel skeleton-joint collaborative modeling framework, which effectively solved the limb confusion problem in dense interaction scenarios through interactive learning of joint graph networks and skeleton graph networks.

ARHPE [18] innovatively adopts the two-dimensional Lorentz distribution and cosquare difference pooling strategy, combining the soft label learning of head poses with asymmetric relationship modeling, significantly improving the pose estimation accuracy of complex label data in industrial human-computer interaction scenarios. In terms of industrial scene optimization, the LDCNet proposed by Liu et al. [19] improves the robustness of pose estimation through the limb direction cue perception mechanism. This method innovatively designs a differentiated Cauchy coordinate coding strategy, adjusts the Cauchy distribution pattern of heat map labels according to the directions of adjacent key points, and simultaneously introduces Jeffreys divergence as a distribution similarity measure. The capture of second-order statistical features through the cosquare differential layer provides a more reliable basis for behavioral biometrics. EHPE [20] effectively solved the problem of positioning ambiguity in occlusion and complex backgrounds by adjusting the direction of the Gaussian covariance matrix to adapt to the change of limb angles and combining the KL divergence and L2 loss constraint models. The latest research [21] introduces the neural modulation mechanism into muscle co-analysis. By decoding the signals of the motor cortex and dynamically adjusting the connection weights of the graph network, it provides a new paradigm for biomechanic-inspired pose estimation.

PoseFormer [22] introduces a pure Transformer architecture into the spatiotemporal modeling of video sequences. Its core idea is to learn the spatial joint relationship within a single frame and the temporal motion pattern between multiple frames through hierarchical Transformer modules. This separate design can capture the global spatiotemporal context, but does not explicitly model the spatiotemporal joint dependencies. Although this method is effective for the global environment, it has difficulty in handling occluded joint recovery due to its uniform attention distribution. The P-STMO (Pre-trained Spatiotemporal Motion Optimization) framework [23] extracts spatiotemporal features of different scales through a multi-branch network and integrates local and global information using a progressive fusion strategy. However, its multi-scale temporal aggregation relies on simple feature splicing and does not consider the problem of noise accumulation in long-range temporal information [24].

In the current study, the positions of human body joints are primarily captured using conventional motion capture devices to enable vector coding-based quantitative analysis of lower limb coordination [25]. Optical motion capture systems require athletes to wear numerous markers to collect kinematic parameters of the body. The discomfort associated with wearing these markers can impair athlete performance, complicating the quantification and analysis of lower limb coordination during competitions and training [26]. The 3D pose estimation algorithm can also capture the positions of human joints using a normal camera and compensate for the above problems. Moreover, compared to optical motion capture systems, cameras offer a more cost-effective solution [27]. Therefore, the use of pose estimation algorithms as well as camera acquisition of the joint positions of the human body is a more appropriate choice compared to optical motion capture devices. However, significant occlusion often occurs during competitions and training. For instance, in multi-player competitive events, inter-individual occlusion is common, while in single-player training scenarios, self-occlusion frequently occurs [17]. As a result, suitable 3D pose estimation algorithms need to be carefully designed to improve model accuracy under occlusion.

Currently, 3D pose estimation algorithms employ two independent modules to capture temporal and spatial information, aiming to address occluded challenges. However, temporal and spatial information are inherently interrelated. To address this issue, we propose a spatial-temporal dependency module to mitigate the impact of anomalous joints on the results. Additionally, most existing studies integrate long-range and short-range temporal information to enhance performance [28]. However, the aggregation of long-range temporal information often introduces significant noise. To mitigate this issue, we propose a noise-compressed multi-scale temporal module designed to filter out irrelevant information during long-range temporal information aggregation. Furthermore, 3D pose estimation is a regression task, and traditional regression methods fail to leverage semantic information to eliminate the impact of occluded joints on the prediction results. To address this limitation, we propose a multimodal training framework that integrates semantic information from textual descriptions to improve 3D pose estimation performance. Currently, few studies have proposed such training approaches to enhance the accuracy of occluded pose estimation.

4 Spatial Temporal Dependency Network with Textual Prompt-Assisted Training

4.1 Spatiotemporal Dependency Module

A limitation of existing research is the use of independent modules to process spatial and temporal information separately. Although this approach has improved the model’s accuracy in estimating occluded poses to some extent, it fails to capture the inherent spatial-temporal relationships of human movements. The spatial-temporal inherent relationship is crucial because when the human body’s posture changes, the movement of each body part occurs simultaneously in both spatial and temporal dimensions. Therefore, if this information can be captured, the model’s performance will be significantly improved.

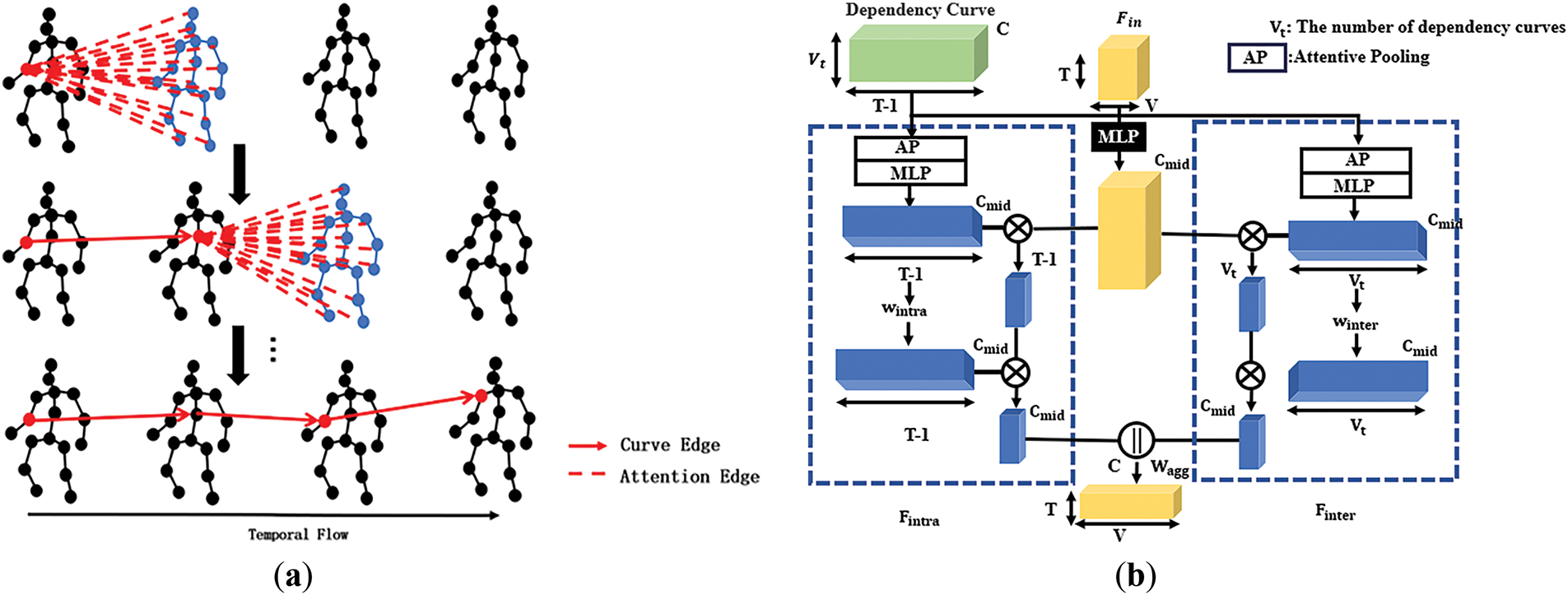

To address this limitation, inspired by [29], we propose a spatiotemporal dependency module that can capture intrinsic spatiotemporal relationships. Reference [29] uses the KNN algorithm based on the position of samples in the feature space to define similarity and select the semantically closest nodes. We establish cross-frame node connections through dynamic dependency curves, generate node dependencies based on feature similarity and attention weights, and build a dynamic semantic graph of non-anatomical connections, thereby capturing more comprehensive and flexible spatiotemporal semantic relationships. We represent all joints in the 2D skeleton sequence data as, where represents the total number of joints in each frame and represents the length of the skeleton sequence. Each joint on the first frame will be used as the starting joint of the dependency curve. For each joint in the coordinate system, there is a semantically closest joint connected to it, as shown in Fig. 1. Taking the nodes in frame t as an example, we will explain how to select the nearest node in the frame and update its features at the same time.

Figure 1: (a) Attention cross-frame operation mechanism. (b) Aggregation module

We perform three linear transformations on all joints in frame

Here,

Using the above-calculated

where

Next, we calculate the updated feature

Finally, we obtain the dependency curve set:

We use the aggregation module from [29] to effectively apply the dependency curves to the input feature map. The structure of the aggregation module is shown in Fig. 1. The feature of each dependency curve is represented as

where

where

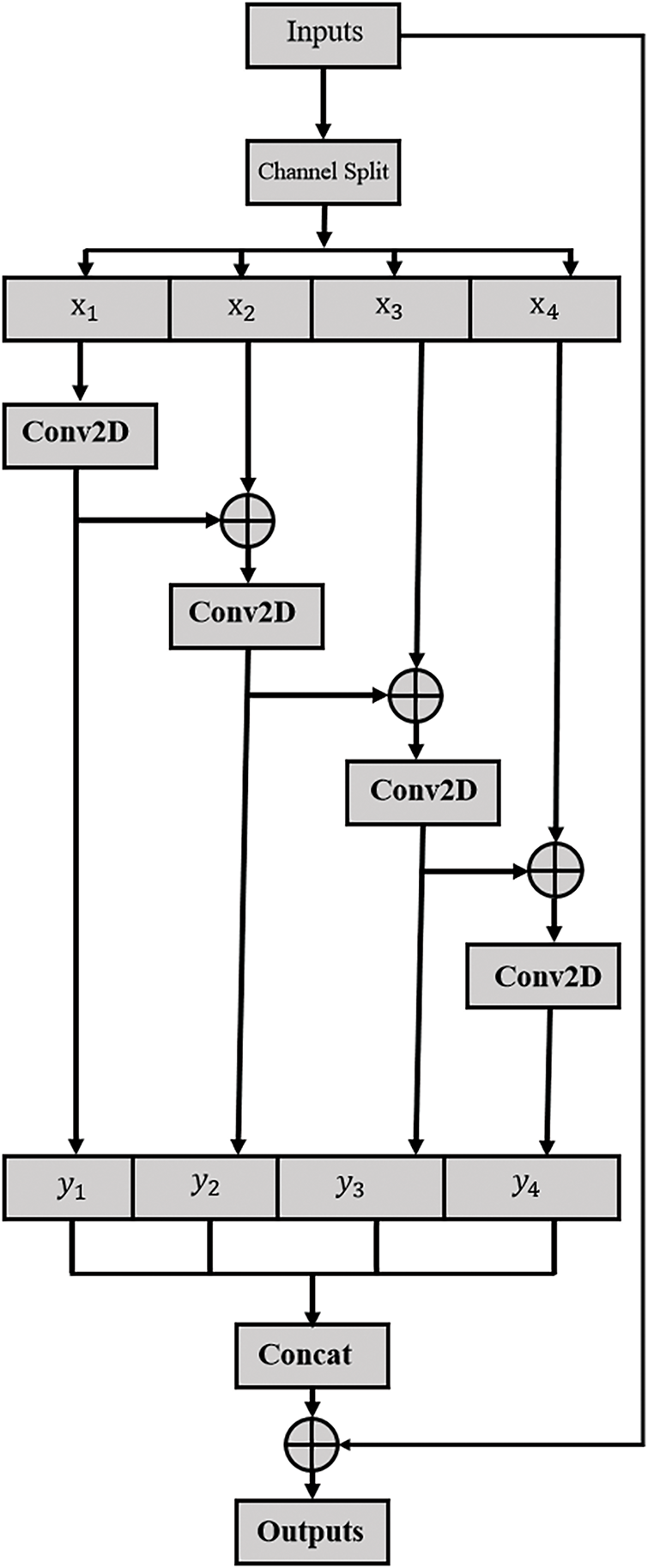

4.2 Noise Compression Multi-Scale Temporal Module

We propose a temporal module designed to suppress noise during the aggregation of long-range temporal information. The aggregation of long-range temporal information is carried out using the following approach:

First, we represent the shape of the input feature map

The output of the

Figure 2: Noise compressed multi-scale temporal module

In terms of noise suppression methods, reference [29] relies on dilated convolution to expand the receptive field. Inspired by [9], after aggregating the information of the previous segments, we apply Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence to the output of the segment to measure the information gain, quantify the information gain attenuation through KL divergence, and adaptively truncate redundant temporal noise. The analysis results show that the information gain IG at is closely related to the function and is greater than 0. This reveals an exponential decay pattern, indicating that the information gain gradually decreases as the number of aggregated fragments increases.

To aggregate long-range temporal receptive fields while suppressing irrelevant information, we use the function in Eq. (10) to determine the output channels of the

where

The channel compression ratio

Among them, the formula for long-range information retention rate is:

Noise interference formula:

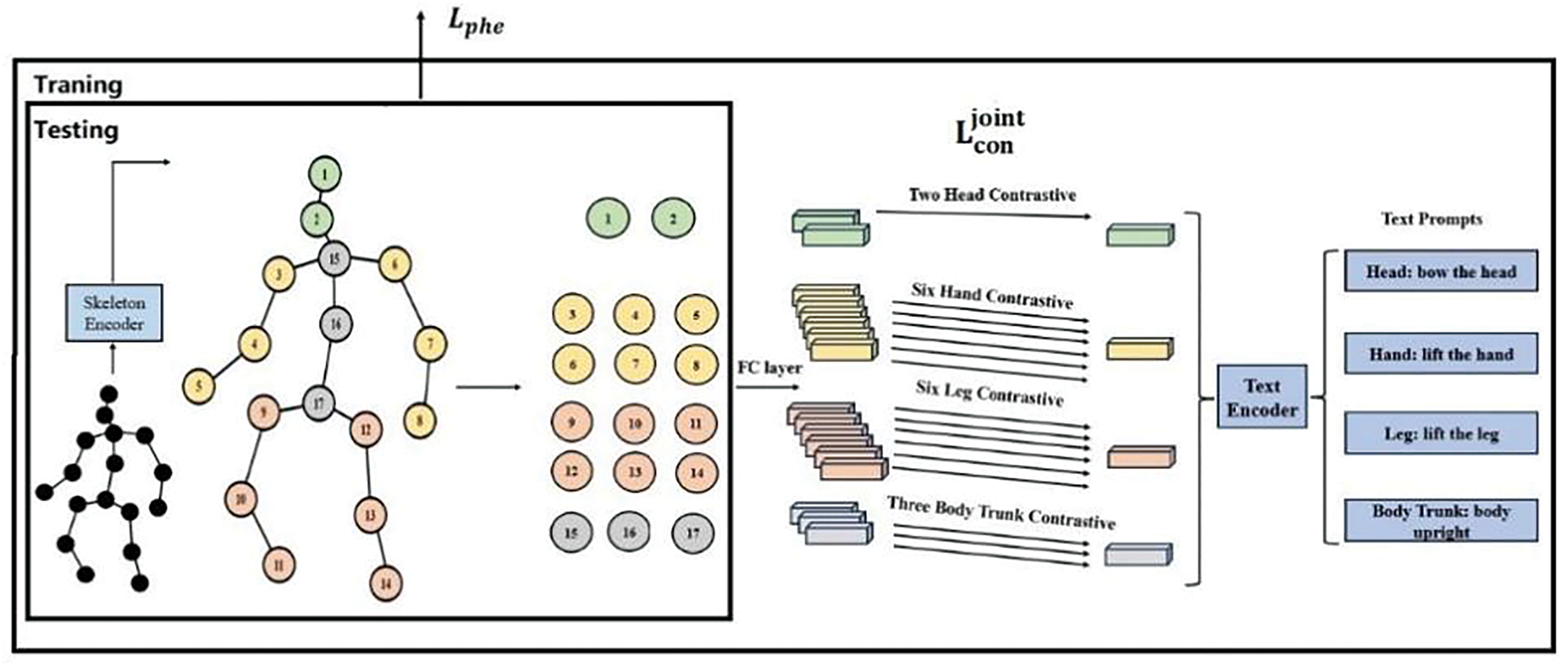

4.3 Multimodal Training Method

Inspired by [30], we propose a multimodal training method to capture the semantic information of actions to address the limitations of existing 2D-to-3D lifting methods. Since 2D-to-3D lifting is a regression task, it is difficult to capture the semantic information of actions. In the case of occlusion, the core challenge of 3D pose estimation is that the lack of local visual information makes it difficult for the regression model to accurately infer the spatial position of the occluded joint. The multimodal training method proposed in this paper effectively solves this problem by introducing action semantic information to provide the model with strong semantic constraints and biomechanical priors. For example, when predicting the body joints of a soccer player kicking a ball, the prediction task becomes particularly challenging if the lower half of the body is occluded by another player. However, if information describing the semantics of the action is available, such as “the knee is slightly bent outward, the inner side of the foot is aligned with the ball, and the back half of the ball is kicked,” it can significantly help the prediction task. We use the pre-trained BERT-base model to extract high-dimensional semantic vectors from action description texts, and obtain global features from the output of the spatiotemporal dependency module through temporal average pooling, which are further aligned with the skeleton features under the contrastive learning framework. This alignment enables the model to implicitly learn the correlation between action categories and joint movement patterns during training. The structure of the modality training method is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Multimodal training approach

The text encoder processes the text descriptions of various body parts to generate text features. These features are then aligned with the corresponding part features output by the skeleton encoder using a multi-node contrastive loss mechanism, ensuring accurate alignment.

The method in [30] has difficulty in solving the temporal incoherence problem in long-term occlusions, so we propose a multi-joint contrastive loss to force the model to maintain the semantic coherence of adjacent frames in the feature space. Compared with the method in [30], this loss function captures more fine-grained local features, effectively preserves the relative positions between joints, and reduces the impact of joint occlusion on pose estimation. The semantic information of the text prompt guides the model to maintain the monotonicity of angle changes in consecutive frame predictions, avoiding sudden changes that violate the laws of motion.

The formula for the multi-joint contrastive loss is as shown in Eq. (13).

Here,

Here,

Here,

By combining the aforementioned multi-joint contrastive loss with the 3D pose estimation loss function, we obtain the overall loss function for the multimodal training method. The calculation formula is shown in Eq. (17).

Here,

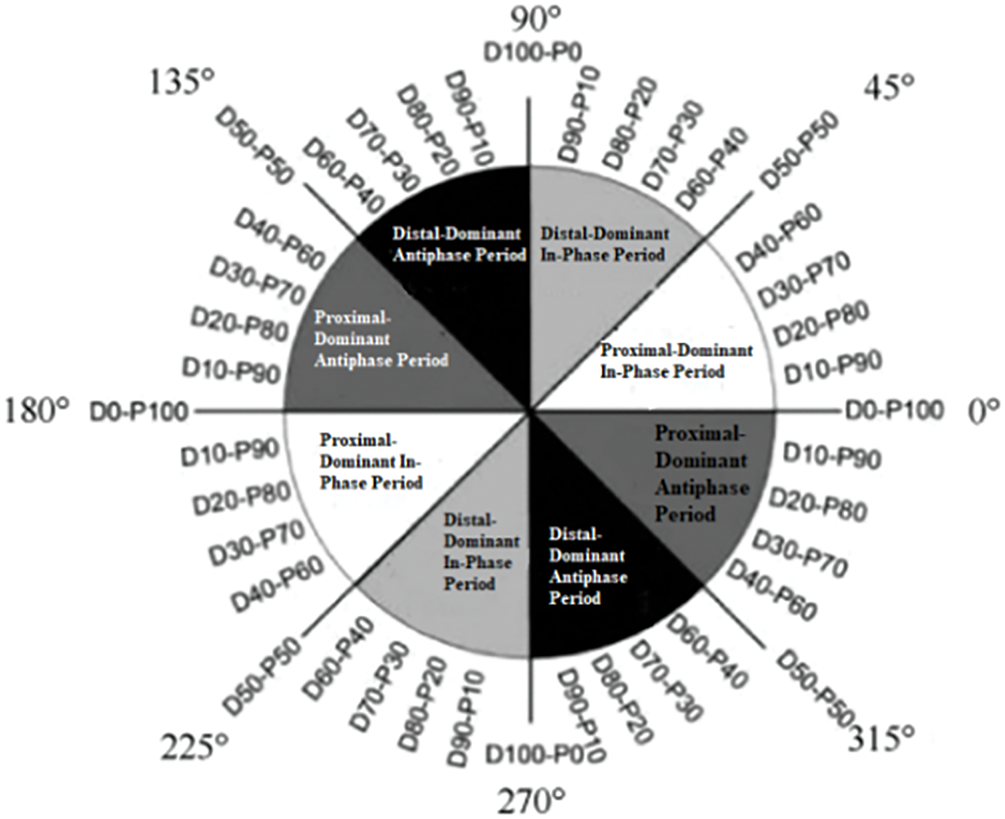

4.4 Quantitative Analysis of Hip-Ankle-Knee Joint Coordination Patterns in the Gait Cycle

To analyze the coordination pattern of the hip, knee, and ankle joints during the gait cycle, we selected five continuous gait cycles, starting 2 min after the subject began running. A complete gait cycle is defined as the period from the right heel strike to the next right heel strike. For gait phase segmentation, we adopted the method uesd by Yen et al. [13] in their study on hip-ankle coordination during the CAI gait process. The entire gait cycle is segmented into five phases, further divided into ten regions, specifically: (1) Loading Response (LR): 10% of the gait cycle; (2) Midstance (MS): 20% of the gait cycle (divided into the front and back halves); (3) Terminal Stance (TS): 20% of the gait cycle (divided into the front and back halves); (4) Pre-swing (PS): 10% of the gait cycle; (5) Swing Phase (SW): 40% of the gait cycle.

The data collected by the Qualisys Track Manager software were exported as C3D files and processed using Visual 3D 4.0 software. The collected data points were smoothed using a zero-lag, fourth-order Butterworth low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 8 Hz. Each gait cycle was interpolated to 101 points, and the three-dimensional joint angles for the hip, knee, and ankle were calculated.

By establishing a coordinate system based on landmark point coordinates, we used the Euler angle method to calculate the 3D joint angles for the hip, knee, and ankle. The definitions of the lower limb joint angles were consistent withthose in the study of Needham et al. [12].

Finally, custom MATLAB R2018b code (MathWorks Inc., USA) was used to compute the coupling angles between the hip-knee, hip-ankle, and knee-ankle joints, as well as their standard deviations, as shown in Eqs. (19) and (20).

The coupling angle (

where

Figure 4: Coordination pattern classification

The Human3.6M [31] dataset is widely used in 3D pose estimation tasks under both single-view and multi-view scenarios. It was captured in a controlled indoor environment using four cameras from different viewpoints to record human poses. A high-speed motion capture system was also used to accurately capture and record the 3D positions of body joints. The dataset contains 3.6 million images, capturing 15 different actions of 11 people. For privacy reasons, only the data of 7 subjects (S1, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S11) are made public, with a total of 840 videos.

The proposed solution was implemented using the PyTorch framework on a GeForce RTX 4060 Ti GPU. For the Human3.6M dataset, we employed a 2D pose detection method based on the Cascade Pyramid Network [32]. The input 2D pose sequence S for the Human3.6M dataset has the shape 351 × 17 × 3. During evaluation, we used the Mean Per Joint Position Error (MPJPE) under Protocol 1 and Protocol 2. Protocol 1 refers to the MPJPE between the real and estimated 3D joints. In Protocol 2, we first align the estimated 3D poses with the real poses using scaling, translation, and rotation, and then calculate the MPJPE. Following previous work [33,34], we used subjects {1, 5, 6, 7, 8} for training and subjects {9, 11} for testing.

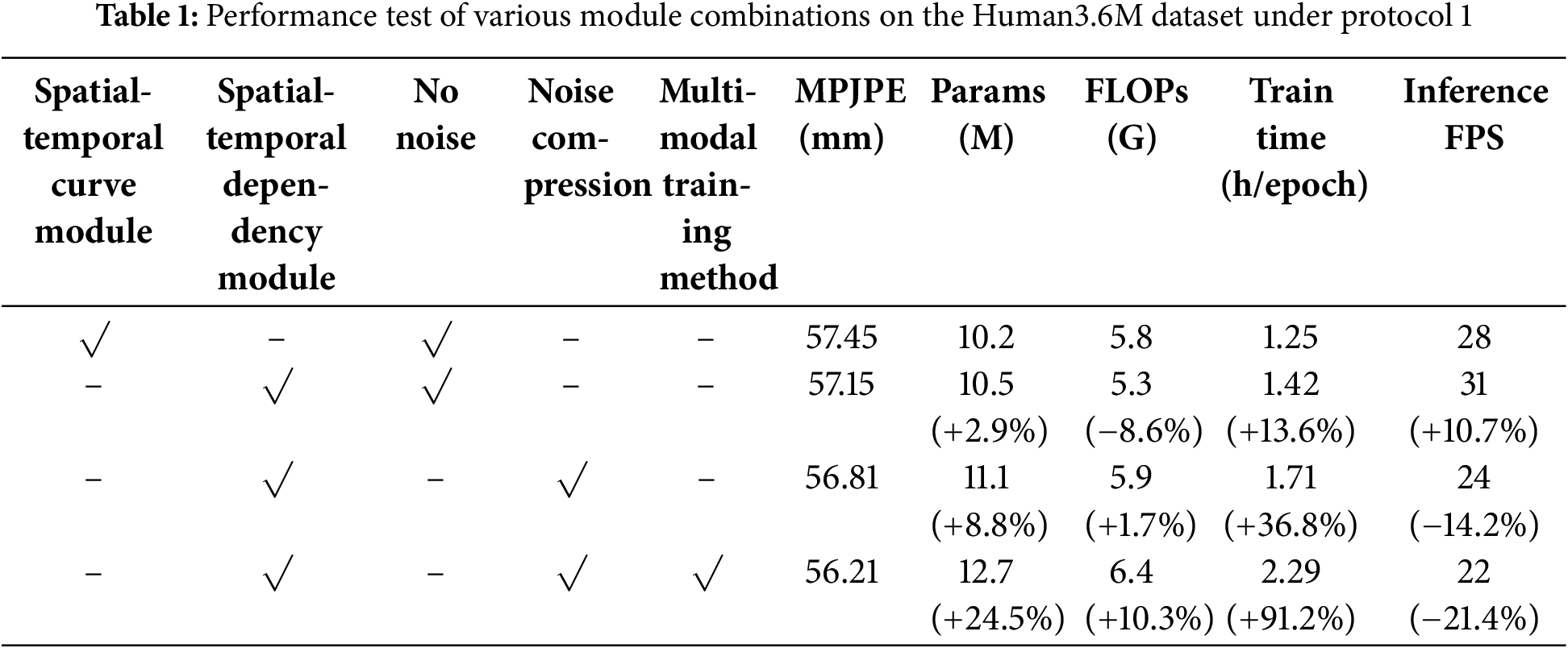

In this section, we combine various modules to validate the effectiveness of the spatial-temporal dependency module, noise-compressed multi-scale temporal module, and the multi-modal training method. Table 1 presents the MPJPE results under Protocol 1 for different combinations of modules. For fairness, we first tested the model with the spatial-temporal curve module from [29], the noise-compressed multi-scale temporal module without the noise compression mechanism, and the model without the multi-modal training method. Then, we replaced the spatial-temporal curve module with our proposed spatial-temporal dependency module, and the model’s MPJPE decreased by 0.3 mm. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the attention mechanism in the spatial-temporal dependency module for selecting nodes with spatial-temporal dependencies, which significantly enhances the model performance. To process temporal information, we employed the noise-compressed multi-scale temporal module, which further reduced the MPJPE by 0.34 mm. This suggests that the noise-compressed multi-scale temporal module effectively filters out irrelevant data from long-range information. Although this module introduces additional computation due to its multi-scale branch parallel processing, which increases the time cost of model training to a certain extent (36.8%), its effective denoising capability can also provide an option for practical application scenarios that balance computational cost and prediction error. Finally, we used our proposed multi-modal training approach to train the model, which combined the noise-compressed multi-scale temporal module and the spatial-temporal dependency module, resulting in an experimental MPJPE of 56.21 mm. Experimental results show that the spatiotemporal dependencies of non-anatomical connections, the adaptive denoising module and the multimodal fusion of textual semantic information can effectively improve the performance of the model.

5.4 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

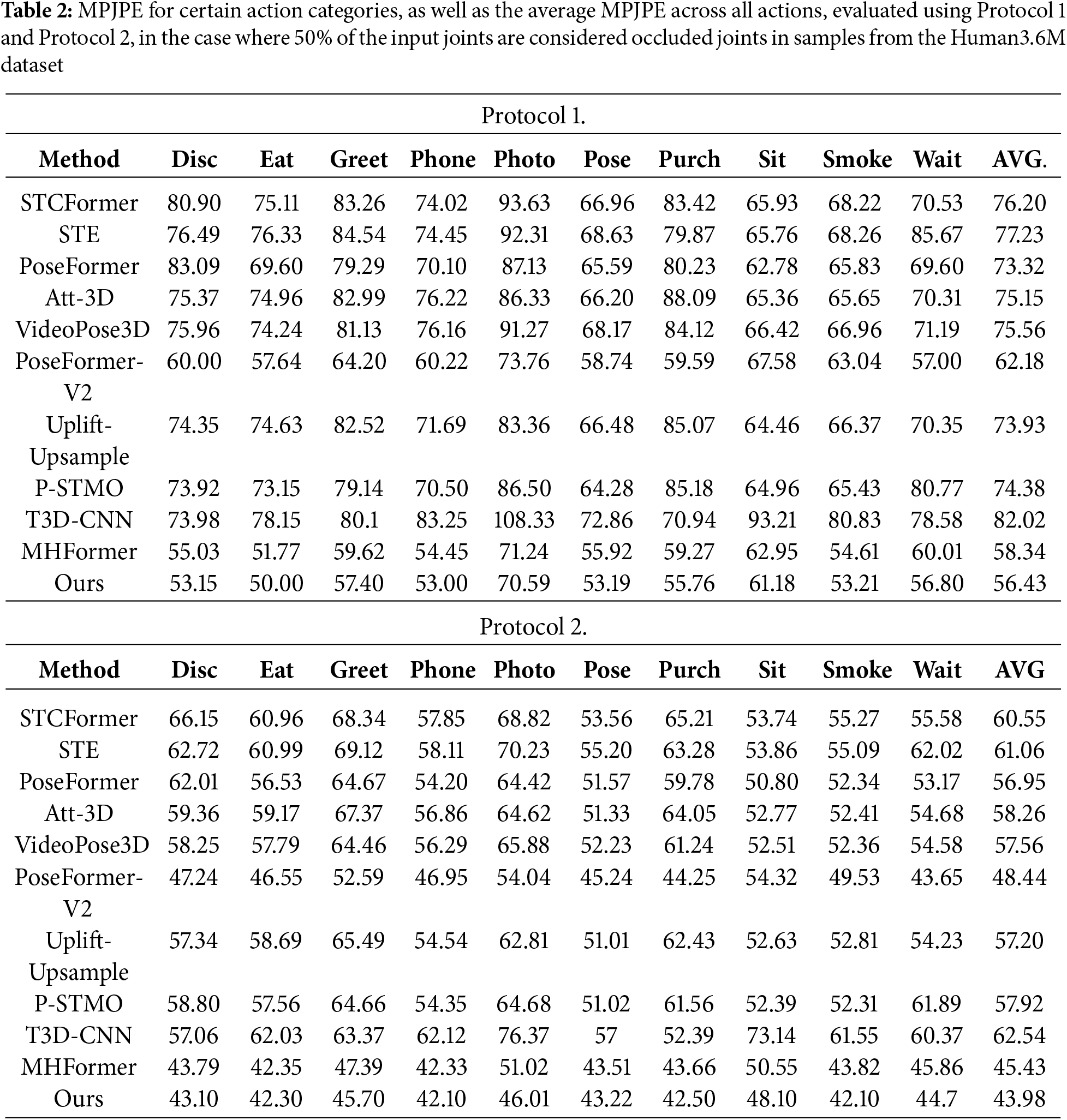

In order to verify the performance of the model in the occluded scene, we randomly occlude the joints of some action category samples in the Human3.6M dataset according to a certain ratio to compare and analyze the performance of each mainstream model and our proposed model. Specifically, we generated a binary occluded mask with a 50% occluded ratio, where half of the input joints were treated as occluded. Table 2 gives the mean joint position errors (MPJPE) for specific action categories calculated under Protocol 1 and Protocol 2, as well as the average MPJPE for all actions in the Human3.6M dataset.

The experimental results in Table 2 demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves the lowest MPJPE values of 56.21 mm under Protocol 1 and 43.84 mm under Protocol 2 across all actions. These results surpass all comparative methods, indicating that our approach—effectively combining the spatial-temporal dependency module, noise-compressed multi-scale temporal module, and multi-modal training method—excels in addressing severe occlusion, significantly outperforming other methods.

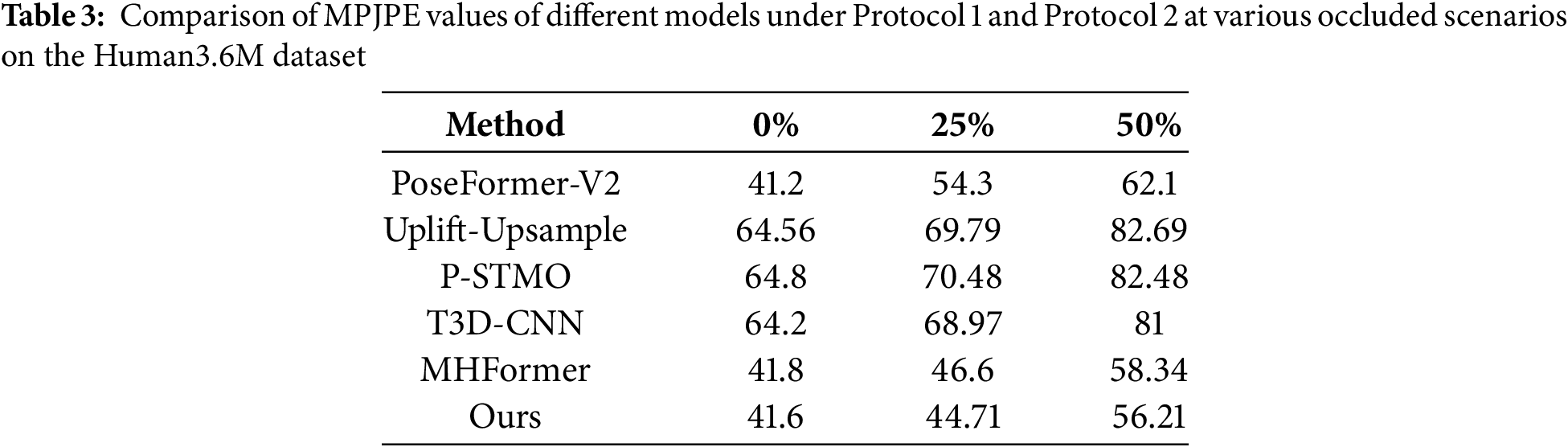

It is worth noting that under Protocol 1, the “Photo” action of almost all comparison methods shows higher MPJPE than other actions. This is because compared with other actions (such as “Walk” and “Eat”), the “Photo” action has more unique periodic dynamic characteristics, and its accompanying postures such as “center of gravity biased towards the supporting leg half squat” and “front step static standing” may destroy the mechanical transmission relationship of the motion chain, thereby leading to incorrect predictions based on the temporal graph neural network model. To further analyze the specific impact of occluded factors on the model’s performance with 2D pose data, we conducted a series of experiments on the Human3.6M dataset. In these experiments, we strictly adhered to the protocols outlined in Protocol 1 and Protocol 2 and carefully designed occluded masks with varying occluded ratios to simulate occluded scenarios. The experimental results are presented in Table 3. Upon examining the results, we find that they align with our expectations: as the occluded ratio increases, the MPJPE of all the compared 3D pose estimation methods also increases.

In the extreme case where 50% of the joints are occluded, our method demonstrates excellent performance, with the model’s MPJPE being only 56.21 mm under Protocol 1, reducing the error by 2.13 mm compared to the next best method. Under Protocol 2, our model’s MPJPE is only 43.84 mm, reducing the error by 1.65 mm compared to the next best method. In cases with 0% and 25% occlusion, our method outperforms the other methods, proving to be the best performing approach. The MPJPE values of our method remain relatively stable across different occluded ratios, which strongly demonstrates the robustness of our method in handling various occluded situations.

5.5 Comparison of AI and Traditional Methods for Lower Limb Coordination Quantification

To verify that our proposed pose estimation algorithm produces results comparable to those obtained using motion capture equipment to analyze lower limb coordination,

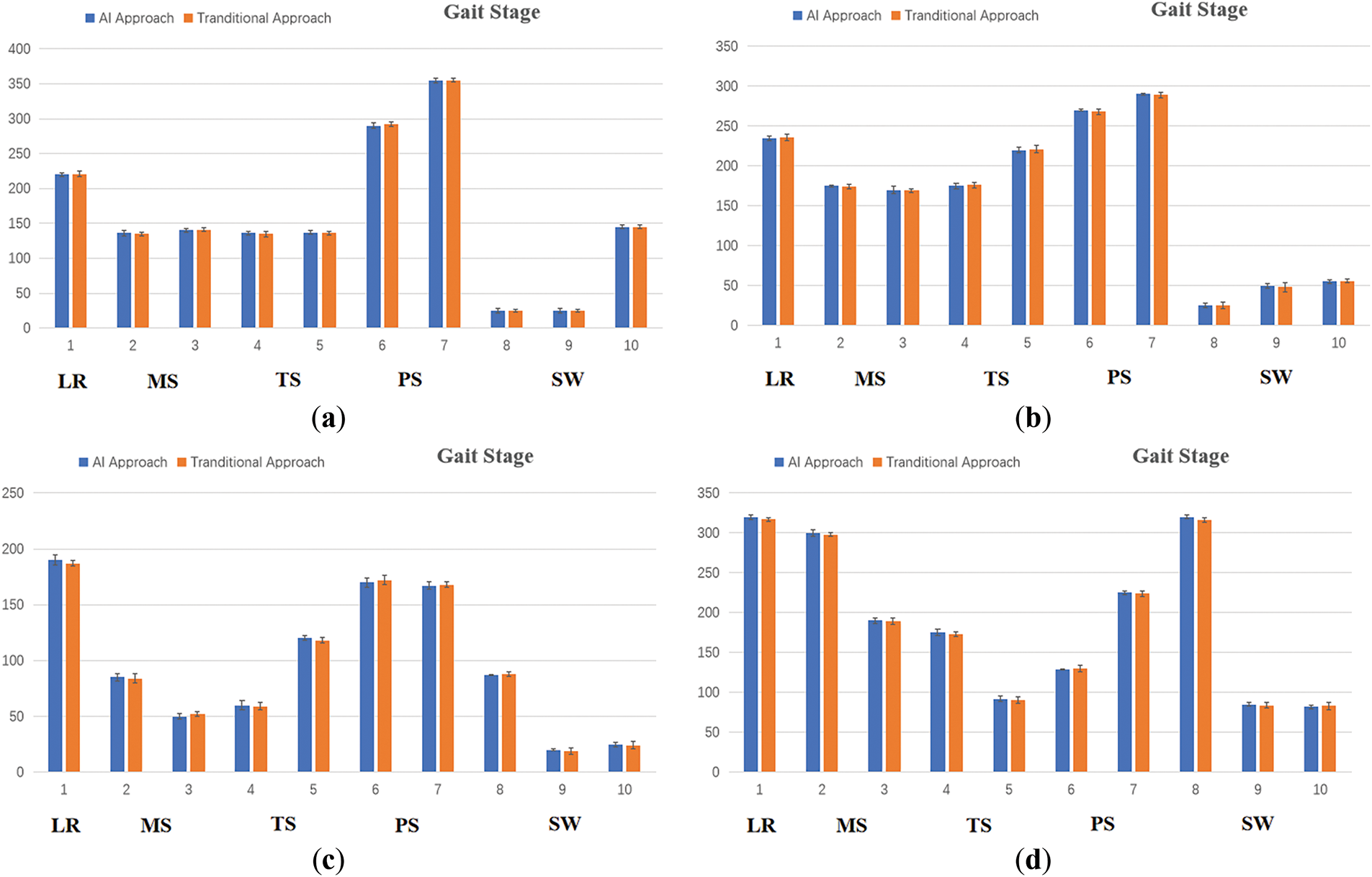

To validate that our proposed pose estimation algorithm produces results comparable to those obtained using motion capture equipment for analyzing lower limb coordination, we conducted a controlled study on 16 male athletes. Inclusion criteria were: height 170 cm, weight 55 kg, age 22 years. We collected the lower limb kinematic parameters from these 16 participants using both traditional and AI-based methods to calculate the average coupling angles in the sagittal plane for the hip-ankle joint, hip-knee joint, knee-ankle joint, as well as the average coupling angle of the hip-ankle joint in the coronal plane. In order to minimize the impact of marker discomfort on movement execution, we chose running movements that were not affected by marker placement, and compared the average coupling angles of 10 groups of sub-gait phases between the two methods.

Traditional Method Data Collection: Participants wore sports shoes and ran along a marked ground path at their preferred running speed until instructed to stop. During the running process, the Qualisys infrared high-speed optical motion capture system (Oqus300, Qualisys, Sweden) was used to collect lower limb kinematic data at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. Reflective markers (14 mm in diameter) were placed on the following anatomical landmarks: left and right anterior superior iliac spines, left and right anterior inferior iliac spines, left and right posterior superior iliac spines, left and right medial and lateral epicondyles, left and right medial and lateral malleoli, left and right heels, left and right first metatarsals, left and right second metatarsals, and left and right fifth metatarsals. A T-shaped thermoplastic plate with a reflective marker ball was affixed to each side of the left and right thighs and left and right calves.

AI Method Data Collection: Participants wore sports shoes and ran along a circular path marked on the ground at a self-selected pace until instructed to stop by the experimenter. During the running process, a standard camera was used to capture the positions of the hip, knee, and ankle joints at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz.

Finally, we utilized self-developed code in Matlab R2018b, along with the formulas from Eqs. (19) and (20), to compute the mean coupling angles for both the traditional method and the AI method. These calculations included the mean coupling angle of the hip-ankle joint in the sagittal plane, the mean coupling angle of the hip-knee joint in the sagittal plane, the mean coupling angle of the knee-ankle joint in the sagittal plane, and the mean coupling angle of the hip-ankle joint in the coronal plane. The results are shown in Fig. 5. From the figure, it is evident that the average coupling angles between the AI and traditional methods are virtually identical for the hip-ankle joint in the sagittal plane, the hip-knee joint in the sagittal plane, the knee-ankle joint in the sagittal plane, and the hip-ankle joint in the coronal plane. This clearly demonstrates that the pose estimation algorithm we proposed produces results that are highly consistent with those obtained using traditional methods.

Figure 5: Comparison of average coupling angles between AI-based methods and traditional methods for the hip-ankle joint, hip-knee joint, knee-ankle joint in the sagittal plane, and the hip-ankle joint in the coronal plane. (a) hip-ankle joint in the sagittal plane; (b) hip-knee joint in the sagittal plane; (c) knee-ankle joint in the sagittal plane; (d) hip-ankle joint in the coronal plane

Hypothesis Definition:

• Null Hypothesis (

• Alternative Hypothesis (

Test Statistics:

For the differences

1. mean difference:

2. standard deviation:

3. standard error:

Two One-Sided Tests (TOST):

Two separate tests are conducted to determine whether the difference is less than Δ and greater than −Δ:

• Upper Bound Test:

• Lower Bound Test:

Decision Criteria:

If

Equivalence Condition:

Equivalence is established if the 90% confidence interval of the mean difference

Power analysis is used to evaluate the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis when the true difference is zero.

Non-Central Distribution Parameters:

• Non-centrality parameter:

• Degrees of freedom:

Statistical Power (SP) Calculation:

Here,

5.5.4 Statistical Analysis Summary

According to the results of the equivalence test, the 90% confidence interval of the difference between the AI method and the traditional method (CI90% = 0.26° ± 0.93°) completely fell within the interval [−1.2°, 1.2°], indicating that under this equivalent interval condition, the AI method is equivalent to the traditional method.

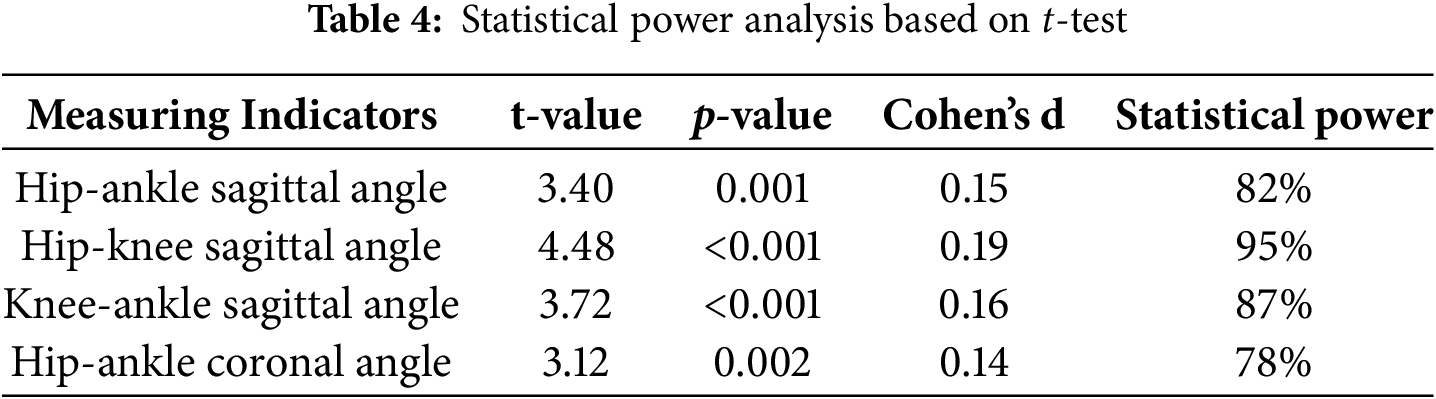

The power analysis showed that the current sample size (n = 160) has sufficient statistical power (78%~95%) under a reasonable standard deviation. However, under the condition of low effect (Cohen’s d < 0.2), the results of the t-test can still detect statistical differences (p < 0.01), because the large sample size may amplify the statistical significance of small differences. As shown in Table 4, AI and traditional methods do have significant differences in all indicators (p < 0.01). However, statistical significance is not equivalent to practical significance. The current data analysis results support that there are small but significant differences between AI and traditional methods in the measurement of lower limb kinematic parameters, but the difference <1.2° is acceptable in the field, which means that the AI algorithm still has application value.

5.6 Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

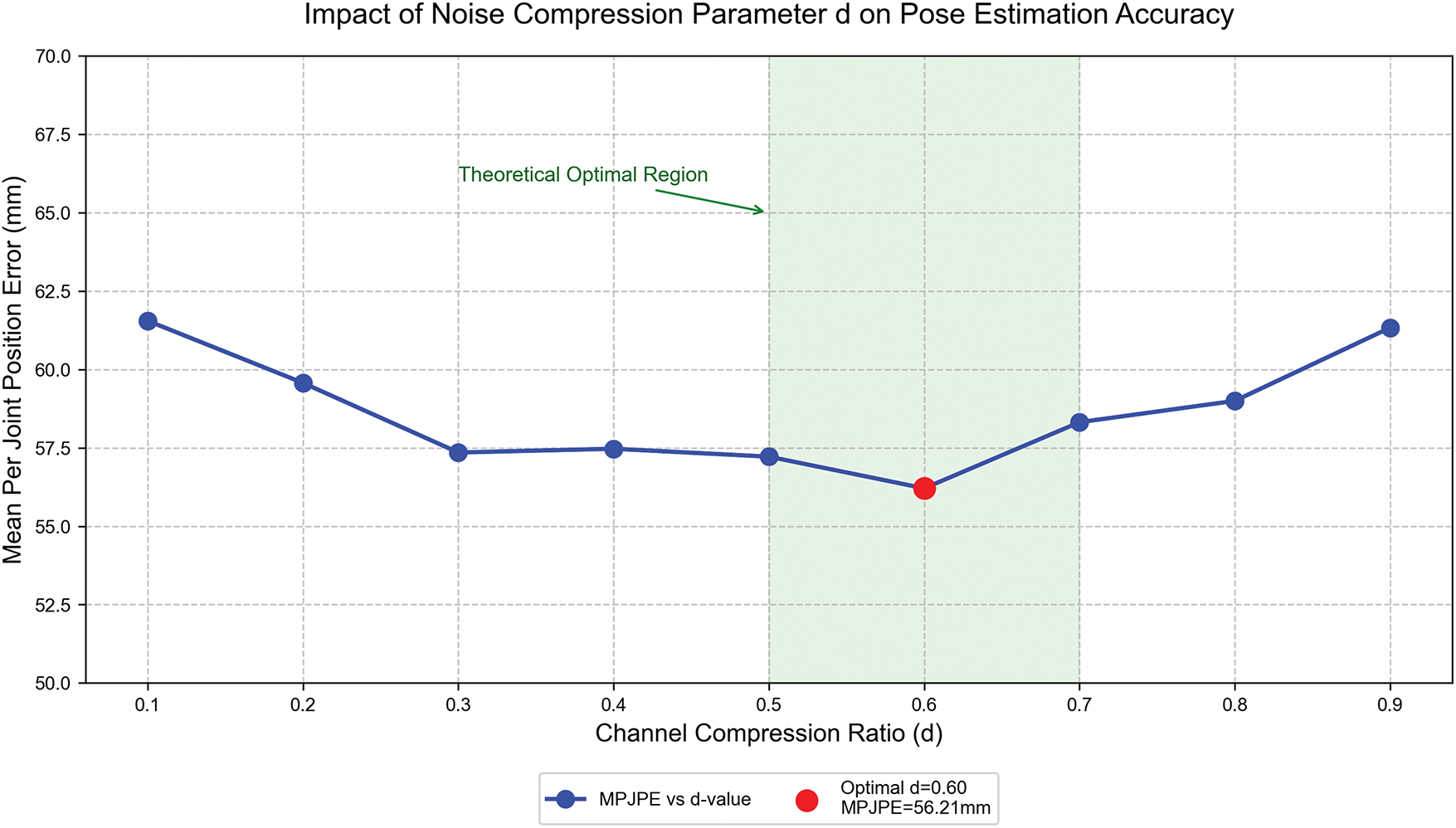

We verified the robustness effects of compression ratio d and the number of attention heads through systematic parameter ablation experiments. On the Human3.6M validation set, we tested the MPJPE changes from d 0.1 to 0.9 (step size 0.1). As shown in Fig. 6, the noise compression parameter d has a significant impact on model accuracy. When the d value is too small (d < 0.5), the channel is over-compressed, resulting in the loss of long-range motion features and a rapid increase in MPJPE; when the d value is too large (d > 0.7), the long-term noise suppression is insufficient, causing the error to rebound. The effectiveness of the exponential decay gating mechanism in Eq. (10) is verified.

Figure 6: The influence curve of compression ratio d on MPJPE

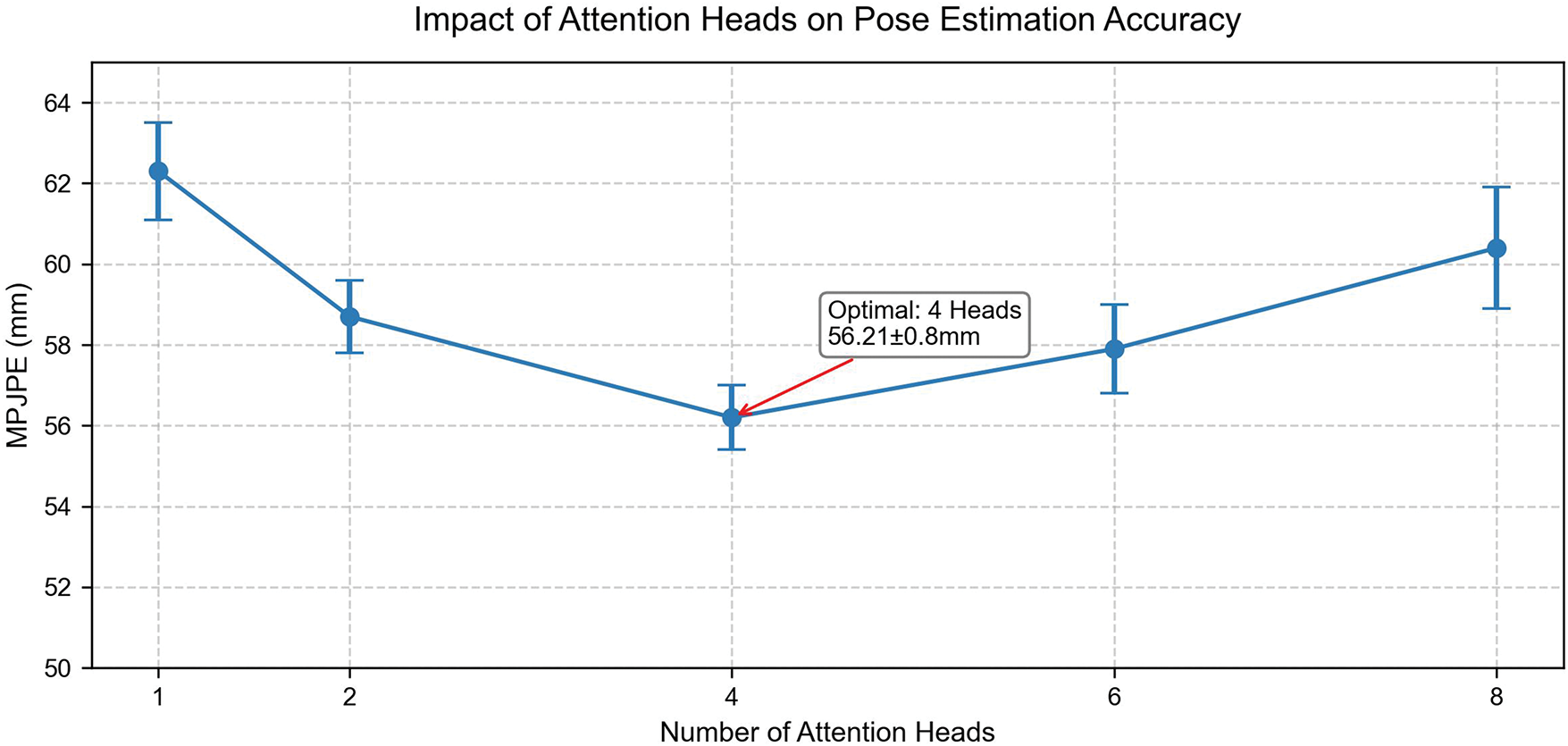

The Goldilocks effect of the number of attention heads (Fig. 7) further reveals the balance mechanism between model capacity and generalization. When 4 attention heads are used, MPJPE reaches the lowest value of 56.21 ± 0.8 mm (standard deviation of 3 experiments). When the number of heads is too small (1–2 heads), the insufficient spatial dependency modeling leads to the decoupling of the joint motion chain, while the number of heads is too large (8 heads) due to parameter redundancy leads to overfitting (the loss of the validation set increased by 19.2%). Experimental data show that when

Figure 7: The influence curve of the number of attention heads on MPJPE

This paper proposes a new method for quantitatively analyzing lower limb coordination in athletes. The approach utilizes AI-based motion analysis techniques, overcoming the limitations of optical motion capture systems, and enables the quantification of lower limb coordination during athlete training and competition, thus enhancing training efficiency and safety. To address occluded issues during training and competition, a new pose estimation model and a multimodal training method are introduced. The model incorporates a spatial-temporal dependency module and a noise-compressed multi-scale time module. Additionally, the multi-modal training method, which integrates skeletal and textual information, enhances prediction performance. Experimental results on the Human3.6M dataset demonstrate that the method outperforms other mainstream methods, particularly excelling in occluded scenarios. This method allows for precise quantification of lower limb coordination without negatively impacting athlete performance during training or competition. Since the model has strong generalization ability and robustness, in actual deployment, there are no excessive requirements for common issues such as lighting conditions and camera angles. Compared to traditional optical motion capture systems, it offers significant cost savings, making it a more accessible and efficient solution for motion analysis.

Although this method performs well in the athlete group, its generalization ability in non-athlete groups (such as rehabilitation patients or the general population) still needs to be verified. The lower limb coordination patterns of athletes are usually highly repeatable and standardized after long-term professional training; while the movements of the general population may show higher individual differences and irregularities. Future work needs to perform transfer learning on cross-group data or introduce an adaptive feature decoupling module to improve the model’s ability to interpret different coordination patterns. In addition, the model in this paper does not have good prediction ability in extreme occlusion challenges. When the occlusion ratio exceeds 70%, the overall error increases by 87.0% (56.21→105.12 mm). The next work can introduce an occlusion adaptive reasoning module. By designing a cascade network based on dynamic adjustment of the occlusion ratio, a high-precision single-frame model is used for low-occlusion areas, and a kinematic chain physical constraint model is used for high-occlusion areas.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Major Sports Research Projects of Jiangsu Provincial Sports Bureau in 2022 (No. ST221101).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xuelin Qin; data collection: Xuelin Qin; analysis and interpretation of results: Huinan Sang; draft manuscript preparation: Xuelin Qin and Huinan Sang; software, methodology: Xuelin Qin and Huinan Sang; writing, review and editing: Xuelin Qin, Huinan Sang, Shihua Wu, Shishu Chen, Zhiwei Chen and Yongjun Ren. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the website link below: Human3.6M: http://vision.imar.ro/human3.6m (accessed on 05 June 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Szabo DA, Neagu N, Teodorescu S, Panait CM, Sopa IS. Study on the influence of proprioceptive control versus visual control on reaction speed, hand coordination, and lower limb balance in young students 14–15 years old. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10356. doi:10.3390/ijerph181910356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Di Paolo S, Zaffagnini S, Pizza N, Grassi A, Bragonzoni L. Poor motor coordination elicits altered lower limb biomechanics in young football (soccer) players: implications for injury prevention through wearable sensors. Sensors. 2021;21(13):4371. doi:10.3390/s21134371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Reina R, Iturricastillo A, Castillo D, Roldan A, Toledo C, Yanci J. Is impaired coordination related to match physical load in footballers with cerebral palsy of different sport classes? J Sport Sci. 2021;39(sup1):140–9. doi:10.1080/02640414.2021.1880740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dejnabadi H, Jolles BM, Aminian K. A new approach for quantitative analysis of inter-joint coordination during gait. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2008;55(2):755–64. doi:10.1109/TBME.2007.901034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lamb PF, Stöckl M. On the use of continuous relative phase: review of current approaches and outline for a new standard. Clin Biomech. 2014;29(5):484–93. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.03.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Winter DA. Biomechanics and motor control of human movement. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

7. Heuvelmans P, Di Paolo S, Benjaminse A, Bragonzoni L, Gokeler A. Relationships between task constraints, visual constraints, joint coordination and football-specific performance in talented youth athletes: an ecological dynamics approach. Percept Mot Skills. 2024;131(1):161–76. doi:10.1177/00315125231213124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chang R, Van Emmerik R, Hamill J. Quantifying rearfoot-forefoot coordination in human walking. J Biomech. 2008;41(14):3101–5. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.07.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zeng A, Sun X, Yang L, Zhao N, Liu M, Xu Q. Learning skeletal graph neural networks for hard 3D pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 11416–25. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ren Y, Sang H, Huang S, Qin X. Multistream adaptive attention-enhanced graph convolutional networks for youth fencing footwork training. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2024;36(4):274–88. doi:10.1123/pes.2024-0025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Cen X, Yu P, Song Y, Sun D, Liang M, Bíró I, et al. Influence of medial longitudinal arch flexibility on lower limb joint coupling coordination and gait impulse. Gait Posture. 2024;114:208–14. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2024.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Needham RA, Naemi R, Chockalingam N. A new coordination pattern classification to assess gait kinematics when utilizing a modified vector coding technique. J Biomech. 2015;48(12):3506–11. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.07.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Yen SC, Chui KK, Corkery MB, Allen EA, Cloonan CM. Hip-ankle coordination during gait in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Gait Posture. 2017;53:193–200. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Deyzel M. Markerless versus marker-based 3D human pose estimation for strength and conditioning exercise identification [Ph.D. dissertation]. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Stellenbosch University; 2023. [Google Scholar]

15. Qiu Z, Qiu K, Fu J, Fu D. DGCN: dynamic graph convolutional network for efficient multi-person pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020 Feb 2–12; Palo Alto, CA, USA. p. 11924–31. [Google Scholar]

16. Cai Y, Ge L, Liu J, Cai J, Cham TJ, Yuan J, et al. Exploiting spatial-temporal relationships for 3D pose estimation via graph convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 2272–81. [Google Scholar]

17. Cheng Y, Wang B, Yang B, Tan RT. Graph and temporal convolutional networks for 3D multi-person pose estimation in monocular videos. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2021 Feb 2–9; Palo Alto, CA, USA. p. 1157–65. [Google Scholar]

18. Liu H, Liu T, Zhang Z, Sangaiah AK, Yang B, Li Y. ARHPE: asymmetric relation-aware representation learning for head pose estimation in industrial human-computer interaction. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(10):7107–17. doi:10.1109/TII.2022.3143605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu T, Liu H, Yang B, Zhang Z. LDCNet: limb direction cues-aware network for flexible human pose estimation in industrial behavioral biometrics systems. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(6):8068–78. doi:10.1109/TII.2023.3266366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu H, Liu T, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Li YF. EHPE: skeleton cues-based gaussian coordinate encoding for efficient human pose estimation. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2024;26:8464–75. doi:10.1109/TMM.2022.3197364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yang N, Li X, An Q, Li J, Shimoda S. Neuro-modulation analysis based on muscle synergy graph neural network in human locomotion. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2025;33(2):1381–91. doi:10.1109/TNSRE.2025.3557777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zheng C, Zhu S, Mendieta M, Yang T, Chen C, Ding Z. 3D human pose estimation with spatial and temporal transformers. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 11656–65. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.01145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Shan W, Liu Z, Zhang X, Wang S, Ma S, Gao W. P-STMO: pre-trained spatial temporal many-to-one model for 3D human pose estimation. In: The European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 461–78. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-20065-6_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lea C, Flynn MD, Vidal R, Reiter A, Hager GD. Temporal convolutional networks for action segmentation and detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 156–65. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2017.113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ma Y, Wen Z, Ju Z, Li X. A study on the lower limb movement coordination characteristics of female speed skaters based on inertial measurement units. J Beijing Sport Univ. 2021;44(12):98–109. (In Chinese). doi:10.19582/j.cnki.11-3785/g8.2021.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zeng J, He X, Hu Y, Zhang Y, Yang H, Zhou S. Research status of data application based on optical motion capture technology. In: 2021 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Information Systems; 2021 May 28–30; New York, NY, USA. p. 1–8. doi:10.1145/3469213.3470248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cho NG, Yuille AL, Lee SW. Adaptive occlusion state estimation for human pose tracking under self-occlusions. Pattern Recognit. 2013;46(3):649–61. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2012.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sun L, Wang Y, Ren Y, Xia F. Path signature-based xai-enabled network time series classification. Sci China Inf Sci. 2024;67(7):170305. doi:10.1007/s11432-023-3978-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lee J, Lee M, Cho S, Woo S, Jang S, Lee S. Leveraging spatio-temporal dependency for skeleton-based action recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 2–6; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 10255–64. doi:10.1109/iccv51070.2023.00941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xiang W, Li C, Zhou Y, Wang B, Zhang L. Generative action description prompts for skeleton-based action recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 2–6; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 10276–85. doi:10.1109/iccv51070.2023.00943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ionescu C, Papava D, Olaru V, Sminchisescu C. Human3.6M: large scale datasets and predictive methods for 3D human sensing in natural environments. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2013;36(7):1325–39. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2013.248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Chen Y, Wang Z, Peng Y, Zhang Z, Yu G, Sun J. Cascaded pyramid network for multi-person pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–22; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 7103–12. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2018.00742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tekin B, Márquez-Neila P, Salzmann M, Fua P. Learning to fuse 2D and 3D image cues for monocular body pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 1–8. Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 3941–50. doi:10.1109/iccv.2017.425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Pavllo D, Feichtenhofer C, Grangier D, Auli M. 3D human pose estimation in video with temporal convolutions and semi-supervised training. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 16–20; Piscataway, NJ, USA. p. 7753–62. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.00794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools